Abstract

Several kalihinol natural products, members of the broader isocyanoterpene family of antimalarial agents, are potent inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum, the agent of the most severe form of human malaria. Our previous total synthesis of kalihinol B provided a blueprint to generate many analogues within this family, some as complex as the natural product and some much simplified and easier to access. Each analogue was tested for blood-stage antimalarial activity using both drug-sensitive and -resistant P. falciparum strains. Many considerably simpler analogues of the kalihinols retained potent activity, as did a compound with a different decalin scaffold made in only three steps from sclareolide. Finally, one representative compound showed reasonable stability toward microsomal metabolism, suggesting that the isonitrile functional group that is critical for activity is not an inherent liability in these compounds.

Keywords: Antimalarial, terpenoid, isonitrile, structure−activity relationship, natural product synthesis

The impact of natural products on the development of modern antimalarial therapy cannot be overstated.1 The discovery of the alkaloid quinine, one of the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, inspired the development of several clinically used drugs for malaria prophylaxis and therapy, including mefloquine, the 4-aminoquinolines chloroquine and amodiaquine, and the 8-aminoquinolines primaquine and tafenoquine. More recently, another natural product, artemisinin, and its semisynthetic analogues have been used in combination with other antimalarials as a first line treatment for P. falciparum malaria worldwide. The chemical diversity and potentially novel modes of action of natural products make them ideal targets for the development of new classes of potent antimalarials.

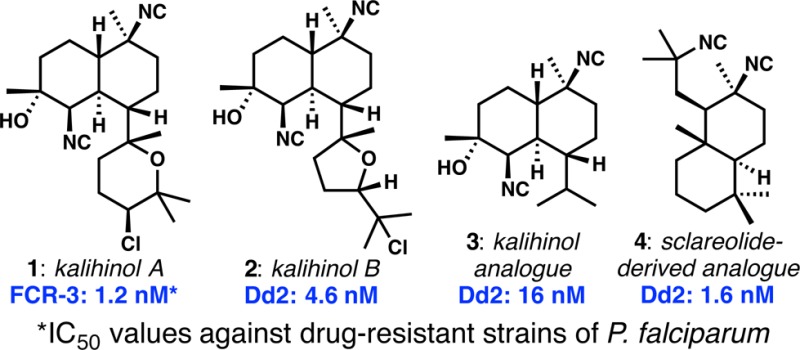

The isocyanoterpenes (ICTs) are a group of sponge-derived polycyclic terpenoids bearing the unusual isonitrile functional group.2 Among the ICTs that have been evaluated for antimalarial activity,3−5 kalihinol A (1, Figure 1) shows the most potent activity against chloroquine-resistant FCR-3 Plasmodium falciparum.5,6 In an important recent development, Shenvi and co-workers demonstrated that representative ICTs have potent liver-stage antimalarial activity in addition to well-established blood-stage potency.7 Interestingly, many structurally diverse ICTs are potent antiplasmodic agents in vitro; however, most of the potent compounds display a common structural feature: the isonitrile-bearing cyclohexane highlighted in red in 1. Comparison of the structural features of each of the ICT subgroups revealed the kalihinols as superior starting points for potential antimalarial lead compound identification; by contrast, the adociane- and amphilectane-type compounds (e.g., 4–6) are particularly hydrophobic. The discovery of simplified kalihinol analogues that retain antimalarial potency, that are easier to make, and that have improved physicochemical characteristics is one of the goals of our research program.

Figure 1.

Representative isocyanoterpenes and their activities against drug-resistant P. falciparum (FCR-3, Dd2, and W2; numbers shown are IC50 values).

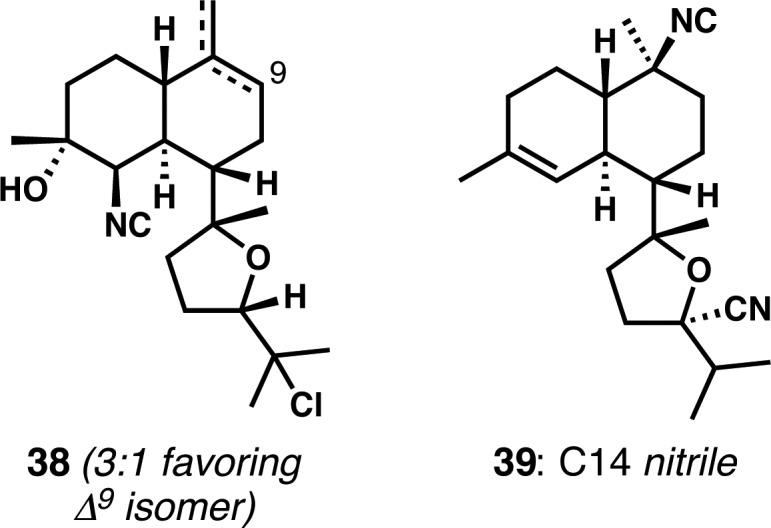

Our recent synthesis of kalihinol B (2),8 the THF-containing congener of kalihinol A, provided a blueprint for quick access to simplified analogues and the impetus to make them: kalihinol B was nearly as active as kalihinol A in spite of the significant structural change. The dramatic simplification of both structure and synthesis that would accrue from removal of the complex pendant heterocycles could conceivably lead to attractive candidates for further antimalarial development.9−12 In this letter, we describe the synthesis and antimalarial activity of several simplified kalihinol analogues and show that the motif highlighted in structure 1 is not an absolute determinant of potency, a conclusion also recently reached by Shenvi and co-workers.7 We further demonstrate that the key isonitrile functional group might not be as serious a metabolic liability as one might expect.

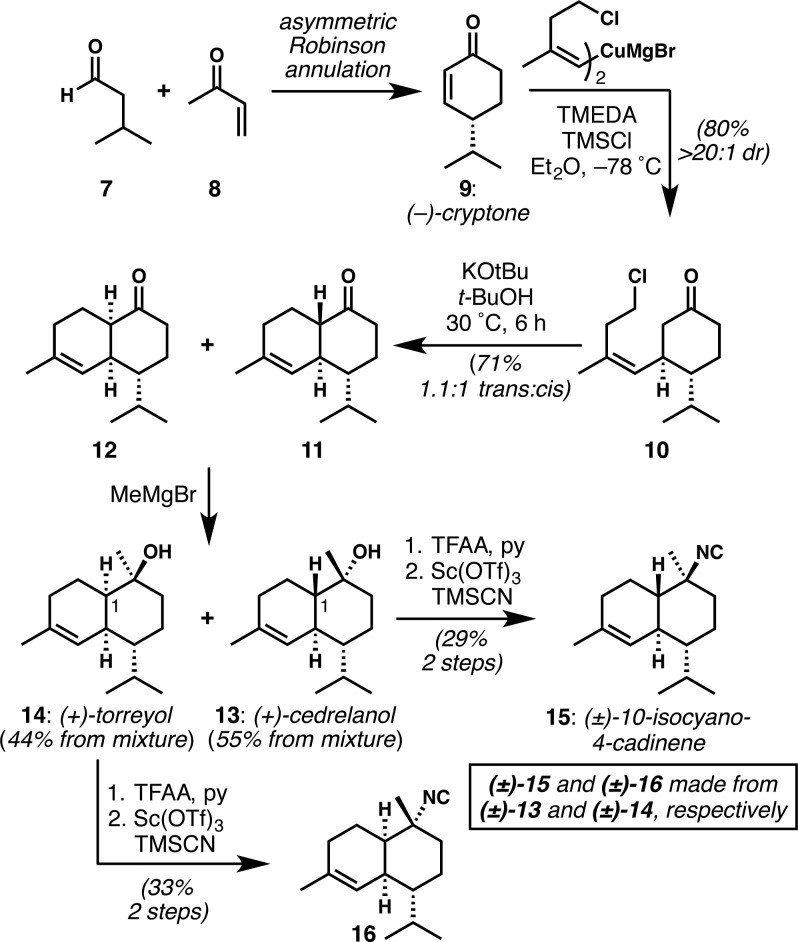

The synthesis of all simplified kalihinol analogues in which the heterocyclic ring was replaced with an isopropyl appendage, started with the synthesis of enantioenriched (+)-cedrelanol (13, Scheme 1). (−)-Cryptone (9) was obtained in enantioenriched form via a Robinson annulation featuring the catalytic asymmetric Michael addition of isovaleraldehyde to methyl vinyl ketone, using the procedure and catalyst of Gellman,13 as used by Baran.14 The remainder of the cedrelanol synthesis exactly paralleled the sequence of steps from our kalihinol B synthesis.8 Two-stage Piers annulation onto cryptone provided the decalones (11 and 12) as a mixture of cis and trans ring fusions. Nucleophilic methylation of the isomeric mixture provided cedrelanol (13) and its stereoisomer torreyol (14), which were readily separable. Although lacking stereochemical control at C1, the synthesis of these sesquiterpenoids is particularly direct, delivering each in enantioenriched form in only five steps. Application of Shenvi’s isonitrile installation15 to racemic samples of 13(15) and 14 provided the well-known monoisonitrile (±)-10-isocyano-4-cadinene (15),16 which has been made several times before but via lengthier sequences,10,15,17,18 and 16, respectively. The latter is the C10 epimer of 10-isocyano-4-amorphene.16,19

Scheme 1. Synthesis of (+)-Cedrelanol, (+)-Torreyol, (±)-10-Isocyano-4-cadinene, and Stereoisomer 16 via Piers-Type Annulation onto Enantioenriched Cryptone.

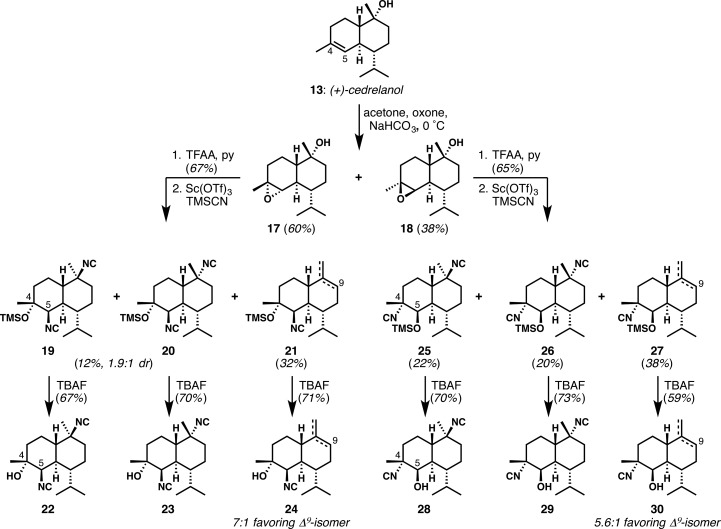

Synthetic (+)-cedrelanol was used to generate six different bis-isonitrile analogues (Scheme 2). Epoxidation of the C4–C5 alkene was not as highly stereocontrolled as in our kalihinol B synthesis, and 17 and 18 were formed in about a 1.5:1 ratio. Activation of the tertiary alcohol of each diastereomer was uneventful. However, attempted isocyanation at C10 with concomitant isocyanolysis of the epoxide yielded multiple products in each case, which were fully characterized after fluoride-mediated removal of the silyl ether (from silylation of the opened epoxide by TMSCN). From α-epoxide 17, all products contained the C5-isonitrile, as expected on the basis of the Fürst–Plattner ring-opening. In this case, invertive displacement of the tertiary trifluoroacetate ester was far from smooth; both stereoisomeric products 19 and 20 were isolated, along with 21, which derived from the competing elimination of the axial tertiary trifluoroacetate ester. Similar problems were observed in our kalihinol B synthesis.8 With β-epoxide 18, the same general trend was observed, with a somewhat improved production of bis-isonitrile diastereomers 25 and 26, which were formed as C4-isonitrile regioisomers on account of Fürst–Plattner ring-opening. Elimination products (27) were also observed.

Scheme 2. Conversion of (+)-Cedrelanol into Six Different Simplified Kalihinol Analogues.

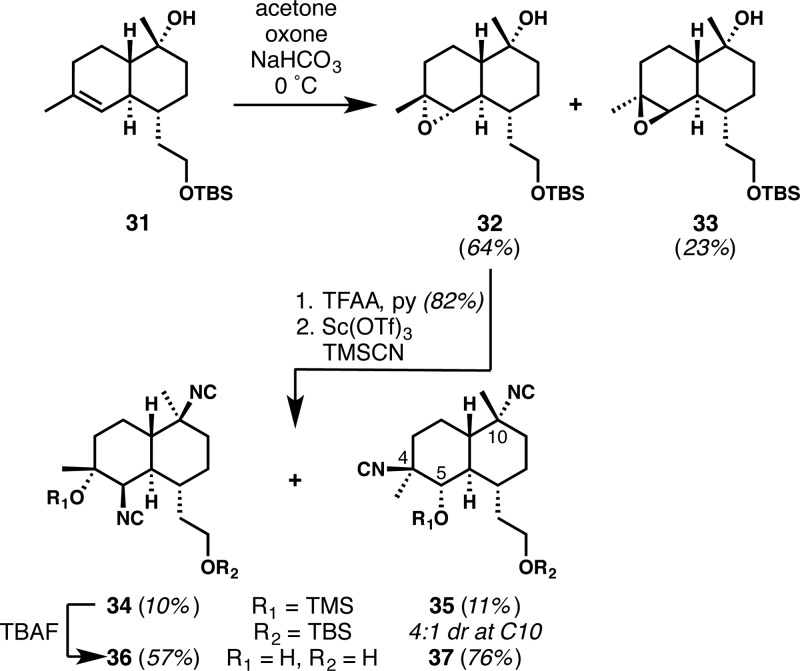

We believed that significant changes to the C7-appendage (cf. kalihinol A vs B) would have little effect on antimalarial potency. We therefore aimed to access kalihinol-based chemical probe molecules featuring functional handles attached at C7 for mechanism of action studies. The latter stages of a synthesis of analogues with a free primary hydroxyl group are shown in Scheme 3. Appropriate groups can easily be appended by esterification or by conversion of the hydroxyl group to an azide and the use of alkyne/azide cycloaddition methods. The synthesis proved straightforward starting from 4-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)butanal.20 Robinson annulation (in the racemic manifold), Piers annulation, and nucleophilic methylation afforded decalin 31 (steps are not shown, but are similar to those in Scheme 1(20)). Epoxidation afforded a ca. 2.5:1 mixture of diastereomers 32 and 33, and application of the 2-fold isonitrile introduction to the major diastereomer provided β-hydroxyisonitrile isomers 36 and 37, in low yields over the three-step sequences. In accord with the Fürst–Plattner principle, diisocyanide 34 resulted from nucleophilic epoxide opening at C5 to give the C4/C5 diaxial product and invertive displacement of the C10 trifluoroacetate to afford the equatorial isonitrile. However, competitive nucleophilic epoxide opening at C4, possibly a result of chelation of the Lewis acid to the epoxide and the pendant silyl ether, afforded the C4/C5 diequatorial product 35. While some kalihinane natural products with equatorial C4-tertiary hydroxyl group and C5-isonitrile are known (the “isokalihinol” series21), we were surprised to observe this product because it is likely to arise from the anti-Fürst–Plattner ring-opening of the epoxide. Interestingly, this C4/C5 diequatorial product was isolated as a mixture of C10 epimers of which the C10 axial isonitrile was predominant (ca. 4.4:1 dr). This result was also unexpected because the C10 equatorial isonitrile, resulting from invertive displacement, is normally the major diastereomer under the reaction conditions. Both of these unusual results speak to the subtle and unpredictable reactivities in complex multifunctional settings.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Kalihinol-Based Chemical Probe Precursors 36 and 37.

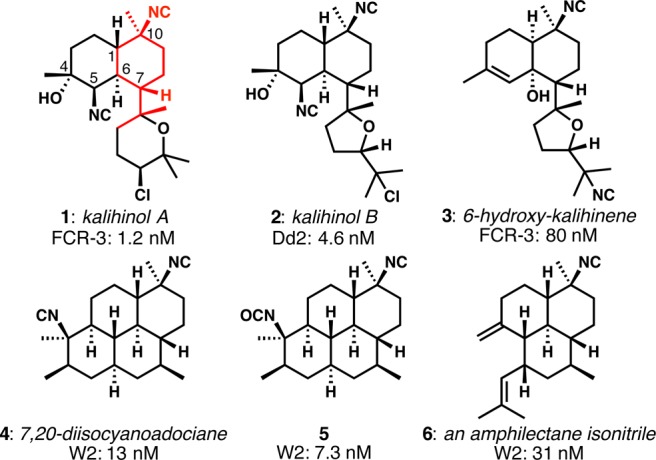

In addition to these planned, simplified analogues, two congeners of kalihinol B were made (Figure 2).20 Monoisonitrile 38 arose (as a mixture of inseparable alkene isomers) from unwanted elimination during attempted C10 isonitrile introduction. C14-nitrile 39 resulted from an attempt to convert a C15-trifluoroacetoxy group into a C15-isonitrile related to 6-hydroxykalihinene (3); hydride shift and cation trapping on the carbon atom of cyanide explains its formation.

Figure 2.

Two analogues from our kalihinol B synthesis efforts.

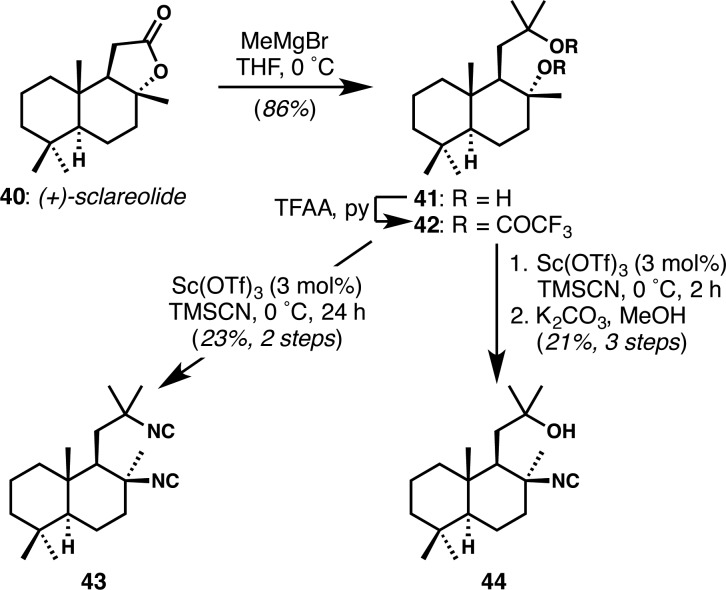

Finally, with the goal of accessing ICT-like structures via simple sequences from readily available materials, we produced two isonitrile-bearing compounds from the inexpensive sesquiterpenoid sclareolide (Scheme 4). Superficially, these compounds were meant to reproduce the complex cyclohexane highlighted in 1 (Figure 1); however, we note that the different decalin ring fusion forces the isonitrile in sclareolide-derived compounds 43 and 44 to be oriented axially, whereas those in structures 1 through 6 have their isonitriles in an equatorial disposition. This procedure gave rise to two complex ICT analogues in only three steps.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Two Sclareolide-Derived ICT-Like Compounds.

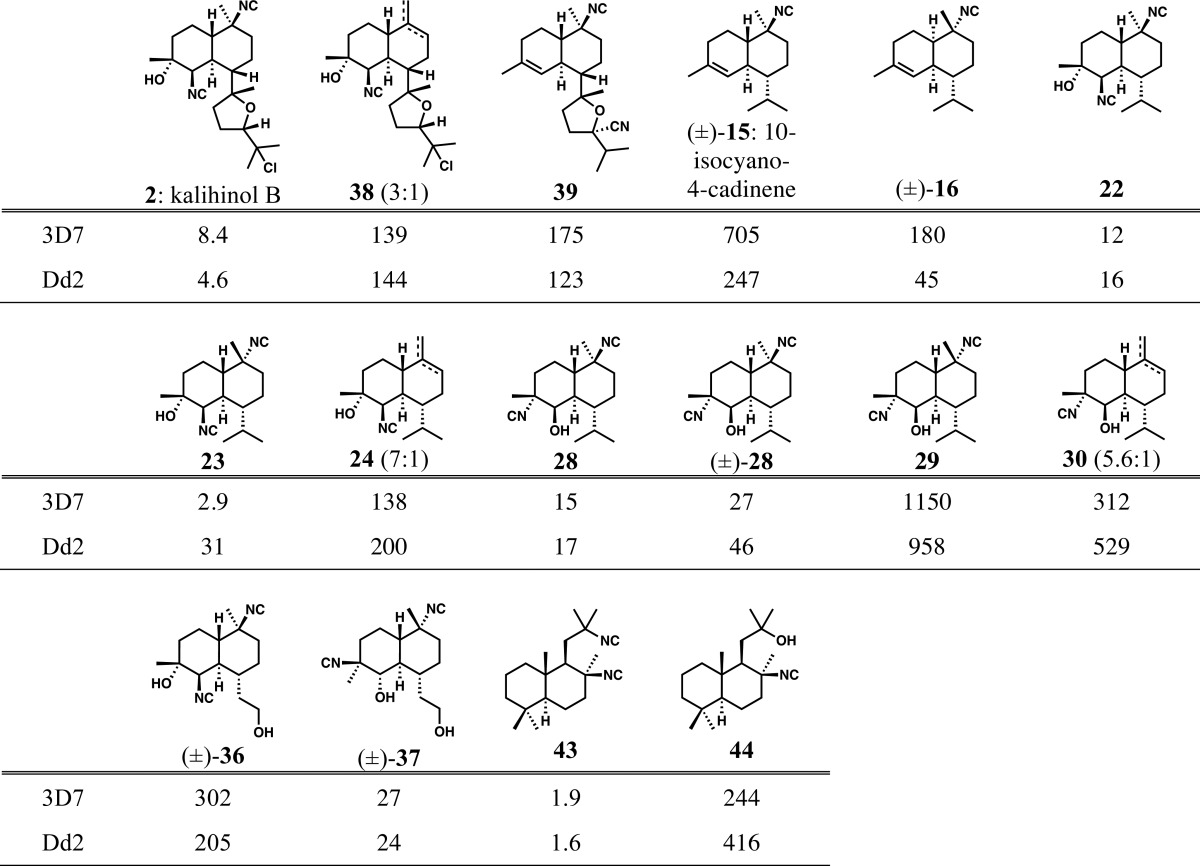

All of the compounds synthesized as described above were evaluated for activity against drug-sensitive 3D7 and chloroquine-resistant Dd2 P. falciparum strains (Table 1). Interestingly, all compounds showed strong antimalarial activity, with IC50 values ranging from 1.6 nM to ca. 1 μM. Monoisonitrile kalihinol B analogues 38 and 39 retained reasonable potency despite having isonitriles in different positions. 10-Isocyano-4-cadinene (15), which has been previously tested by Wood,11,22 was not as potent as its cis-decalin stereoisomer (16, also epimeric at C10). Most importantly, a variety of kalihinol analogues lacking the complex THP or THF rings of kalihinols A and B, respectively, retained great potency. Analogue 22(10,22) retains all other structural features of 1 and 2 and is potent. Individually, the change in configuration at the isonitrile-bearing C10 (see 23) or the interchange of C4/C5 substituents (see 28, with the C4-isonitrile and C5-secondary alcohol) does not significantly affect potency. The activity of the compounds arising from undesired trifluoroacetate elimination is similar across the board (compare 38, simplified version 24, and 30 with its swapped C4/C5 substituents). The least active compound in the series of C7-isopropyl compounds is 29, with unnatural C10 configuration and C4/C5 substituent interchange. The two chemical probe precursors provided confounding results, wherein analogue (±)-36, with its full set of natural features, proved an order of magnitude less active than (±)-37, in which both the C10 center is inverted, C4 bears an equatorial isonitrile, and C5 bears an equatorial hydroxyl group (note this compound differs in the C4 and C5 configurations relative to 29). Finally, and provocatively, sclareolide-derived bis-isonitrile 43 was the most potent compound synthesized (IC50 of 1.6 nM against Dd2 strain), with essentially equal potency to kalihinol A, the most potent ICT ever reported (IC50 of 1.2 nM against FCR-3 strain). Monoisonitrile 44 was significantly less active. Shenvi and colleagues have made closely related compounds to 43 and 44 from dihydrosclareol and reported potent activities.7

Table 1. Results of Antiplasmodial Assays of Synthetic ICTs and Analogues against Drug-Sensitive (3D7) and Drug-Resistant (Dd2) Strains of P. falciparum (Numbers Shown Are IC50 Values in nM).

Our findings include: (1) the apparent insignificance of the complex heterocyclic rings in the natural kalihinols; (2) the potential significance of the cis-decalin that is poorly represented among kalihinol natural products previously evaluated for antimalarial activity; (3) the flexibility with respect to axially or equatorially disposed C10 isonitriles;23 and finally (4) the flexibility with respect to the C4/C5 β-hydroxy isonitrile regiochemistry and configurations in some cases. We note that the motif highlighted in Figure 1 does not seem to be the definitive pharmacophore; unfortunately, it remains difficult to make any clear structure–activity conclusions with the data currently available from natural products and from synthesis work from our laboratories and those carried out previously by others.5,7−9

Our concerns for the viability of kalihinol compounds as potential preclinical leads hinged in part on the expected in vivo instability of the isonitrile function. Compound (±)-37, one of the chemical probe precursors, retained potency in spite of the serious structural changes relative to the natural kalihinols and in spite of its racemic nature. This compound was subjected to microsomal stability assays, using both human and murine liver microsomes. Interestingly, we found that this potent ICT analogue showed significant stability in the presence of liver microsomes, with half-lives of 142 min (human) and 87 min (murine).24 While more studies are warranted, this preliminary result suggests that there is nothing intrinsically poor about the salient isonitrile functional groups that are so intimately tied to potency in the ICT family of antimalarials.

The kalihinol scaffold appears to be a promising starting point for the development of interesting antimalarial lead compounds. Many of the simplified analogues synthesized in this study retain high potency and are much easier to access than the natural products; however, the results do not show clear SAR trends. The ICTs have been shown previously to show good selectivity indices3,5 with respect to mammalian cytotoxicity and to have multistage activity;7 the latter point conflicts previous notions that their activity is due to inhibition of pathways for heme detoxification.25 We have now shown that the salient isonitrile functional groups are not a metabolic liability. Future studies aimed to engineer the kalihinane scaffold to identify simpler congeners with improved physicochemical properties and high in vitro and in vivo efficacy are warranted, as are investigations into the incompletely understood mechanism(s) of action of these antimalarial agents.

Acknowledgments

The following reagents were obtained through the MR4 as part of the BEI Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH: Plasmodium falciparum strains 3D7 (MRA-102) deposited by D. J. Carucci and Dd2 (MRA-156) deposited by Thomas Wellems.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ICT

isocyanoterpene

- TMEDA

tetramethylethylenediamine

- TFAA

trifluoroacetic anhydride

- TMS

trimethylsilyl

- TBS

tert-butyldimethylsilyl

- TBAF

tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00013.

General experimental details, experimental procedures for the synthesis of and characterization data for all new compounds, experimental details and raw data for the antimalarial assays and information about the metabolic stability experiments for compound (±)-37 (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

This study was financially supported by the University of California, Riverside (NIFA-Hatch-225935 to K.G.L.R.). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript. M.E.D. was supported in part by an Allergan Graduate Fellowship.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fernández-Álvaro E.; Hong W. D.; Nixon G. L.; O’Neill P. M.; Calderón F. Antimalarial Chemotherapy: Natural Product Inspired Development of Preclinical and Clinical Candidates with Diverse Mechanisms of Action. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5587–5603. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnermann M. J.; Shenvi R. A. Syntheses and Biological Studies of Marine Terpenoids Derived from Inorganic Cyanide. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 543–577. 10.1039/C4NP00109E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A. D.; König G. M.; Angerhofer C. K.; Greenidge P.; Linden A.; Desqueyroux-Faúndez R. Antimalarial Activity: The Search for Marine-Derived Natural Products with Selective Antimalarial Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 710–716. 10.1021/np9602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Only a select few of the over 50 kalihinane natural products have been evaluated in antimalarial assays, reflecting the relatively late discovery of this activity relative to the isolation of many of these compounds.

- Antimalarial activity of kalihinol A and four other kalihinanes:Miyaoka H.; Shimomura M.; Kimura H.; Yamada Y.; Kim H.-S.; Wataya Y. Antimalarial Activity of Kalihinol A and New Relative Diterpenoids from the Okinawan Sponge, Acanthella sp. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 13467–13474. 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00818-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalihinol A isolation:Chang C. W. J.; Patra A.; Roll D. M.; Scheuer P. J.; Matsumoto G. K.; Clardy J. Kalihinol-A, a Highly Functionalized Diisocyano Diterpenoid Antibiotic from a Sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4644–4646. 10.1021/ja00328a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.-H.; Pronin S. V.; Antonova-Koch Y.; Meister S.; Winzeler E. A.; Shenvi R. A. Synthesis of (+)-7,20-Diisocyanoadociane and Liver-Stage Antiplasmodial Activity of the Isocyanoterpene Class. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7268–7271. 10.1021/jacs.6b03899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub M. E.; Prudhomme J.; Le Roch K.; Vanderwal C. D. Synthesis and Potent Antimalarial Activity of Kalihinol B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4912–4915. 10.1021/jacs.5b01152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In their investigations on the kalihinols, the Wood group made a large number of analogues based on the cadinane, or “truncated kalihinane” framework. They synthesized five isonitrile-containing compounds, including (±)-15 (10-isocyano-4-cadinene) and (±)-22. Others were made that bore isothiocyanates and formamides in the usual positions of the isonitriles; these functional groups have also been seen in natural products coisolated with ICTs. Further analogues were made with nitriles and azides. None of the compounds devoid of isonitriles demonstrated appreciable antimalarial activity, See refs (10), (11), and (12).

- White R. D. Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keaney G. F. Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- White R. D.; Wood J. L. Progress toward the Total Synthesis of Kalihinane Diterpenoids. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1825–1827. 10.1021/ol015828k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y.; Gellman S. H. Diphenylprolinol Methyl Ether: A Highly Enantioselective Catalyst for Michael Addition of Aldehydes to Simple Enones. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4253–4256. 10.1021/ol0517729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Ishihara Y.; Galán M. M.; Baran P. S. Total Synthesis of Eudesmane Terpenes: Cyclase Phase. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 4738–4744. 10.1016/j.tet.2010.02.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin S. V.; Reiher C. A.; Shenvi R. A. Stereoinversion of Tertiary Alcohols to Tertiary-alkyl Isonitriles and Amines. Nature 2013, 501, 195–199. 10.1038/nature12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okino T.; Yoshimura E.; Hirota H.; Fusetani N. New Antifouling Sesquiterpenes from Four Nudibranchs of the Family Phyllidiidea. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 9447–9454. 10.1016/0040-4020(96)00481-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K.; Nakahara H.; Shirokura Y.; Nogata Y.; Yoshimura E.; Umezawa T.; Okino T.; Matsuda F. Total Synthesis of 10-Isocyano-4-cadinene and Determination of Its Absolute Configuration. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 904–907. 10.1021/ol9027336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K.; Nakahara H.; Shirokura Y.; Nogata Y.; Yoshimura E.; Umezawa T.; Okino T.; Matsuda F. Total Synthesis of 10-Isocyano-4-cadinene and Its Stereoisomers and Evaluations of Antifouling Activities. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6558–6573. 10.1021/jo2008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burreson B. J.; Christophersen C.; Scheuer P. J. Co-occurrence of Two Terpenoid Isocyanide-formamide Pairs in a Marine Sponge (Halichondria sp.). Tetrahedron 1975, 31, 2015–2018. 10.1016/0040-4020(75)80189-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Please see the Supporting Information for details.

- See, for example:Fusetani N.; Yasumuro K.; Kawai H.; Natori T.; Brinen L.; Clardy J.; Kalihinene; Isokalihinol B. Cytotoxic Diterpene Isonitriles from the Marine Sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3599–3602. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94453-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Wood group found that (±)-15 had IC50 values of 2.2 μM against HB3 (chloroquine-sensitive) and Dd2 (chloroquine-resistant) strains of P. falciparum (ref (11)). Compound (±)-22 had IC50 values of 80 nM against both HB3 and Dd2 strains (ref (10)).

- The Shenvi group recently noted that the potential pharmacophore corresponding to a conformationally constrained cyclohexane bearing a tertiary equatorial isonitrile (as shown in 1) did not adequately account for antimalarial activities of compounds from their studies, including analogues related to 43. See ref (7).

- Assay performed under contract by Shanghai ChemPartner Co. Ltd.

- Wright A. D.; Wang H.; Gurrath M.; König G. M.; Kocak G.; Neumann G.; Loria P.; Foey M.; Tilley L. Inhibition of Heme Detoxification Processes Underlies the Antimalarial Activity of Terpene Isonitrile Compounds from Marine Sponges. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 873–885. 10.1021/jm0010724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.