Abstract

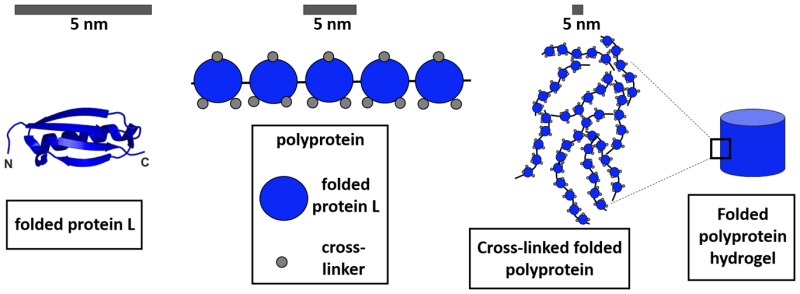

The native states of proteins generally have stable well-defined folded structures endowing these biomolecules with specific functionality and molecular recognition abilities. Here we explore the potential of using folded globular polyproteins as building blocks for hydrogels. Photochemically cross-linked hydrogels were produced from polyproteins containing either five domains of I27 ((I27)5), protein L ((pL)5), or a 1:1 blend of these proteins. SAXS analysis showed that (I27)5 exists as a single rod-like structure, while (pL)5 shows signatures of self-aggregation in solution. SANS measurements showed that both polyprotein hydrogels have a similar nanoscopic structure, with protein L hydrogels being formed from smaller and more compact clusters. The polyprotein hydrogels showed small energy dissipation in a load/unload cycle, which significantly increased when the hydrogels were formed in the unfolded state. This study demonstrates the use of folded proteins as building blocks in hydrogels, and highlights the potential versatility that can be offered in tuning the mechanical, structural, and functional properties of polyproteins.

Introduction

Biomolecules provide an almost limitless pool of evolutionary-optimized materials that can be exploited or repurposed to engineer materials with highly specialized functionalities.1,2 Such materials include hydrogels: three-dimensional macroscopic networks swollen by large volumes of water, in some special cases up to 1000× its dry mass.3 Protein hydrogels use polypeptide chains as the hydrophilic network in order to exploit their intrinsic properties,2,4−9 and they have found applications in tissue engineering, such as vascular grafts and neural tissue regeneration, as well as scaffolds for controlling cell behavior.10−14 In addition, stimulus-responsive protein hydrogels have been explored as ligand-triggered actuators for biosensors and for controlled release for drug delivery.1,4,15−19 However, as most protein-based hydrogels are obtained from unstructured peptides or through aggregation of unfolded globular proteins,20−25 the full spectrum of protein function (e.g., catalysis, signaling, and ligand binding) has not yet been exploited. A recent novel approach, that not only obviates these limitations but also harnesses their distinct functional properties, is to build hydrogels from tandem arrayed, folded globular proteins with known mechanical properties.15,26,27 The mechanical properties of the native state of single, monodisperse proteins can be obtained by single molecule atomic force spectroscopy using the atomic force microscope (AFM)28−31 or optical tweezers32,33 as sensitive force transducers. In principle, information derived from single molecule force experiments allows for careful selection of a protein building block with the appropriate mechanical properties for the designed hydrogel. The functional, structural, and mechanical properties of folded protein hydrogels can be further expanded by the use of a repeating pattern of identical or diverse folded proteins of a defined length and density of cross-linking sites as the building block.15,16,26,27,29 However, little is known about the relationship between mechanical properties of proteins when extended as a single molecule and when incorporated into a cross-linked hydrogel. This is because the bulk properties of hydrogels arise from the interplay of nanoscopic and mesoscopic supramolecular organization.21,34−36 Therefore, both the bulk dynamic and structural properties are defined not only by its chemical and physical composition, but also by the spatial organization of its components.20,37 To delineate this relationship, a detailed and systematic approach is required to determine how the folded protein building blocks assemble to form the hydrogel, as well as to understand how the mechanical and structural properties of the single proteins translate to the bulk properties of the hydrogel.

As a first step toward this goal, we investigate the structure and rheological properties of protein hydrogels derived from mechanically robust polyprotein constructs of folded I27 or protein L domains (Scheme 1). To examine the macroscopic structural and mechanical properties of networks of these proteins, hydrogels resulting from photoactivated cross-linking of these polyproteins were investigated using shear rheology and both neutron. This provided important insights into the elastic and viscoelastic properties of the hydrogels as well as their network morphology at the nanoscale.

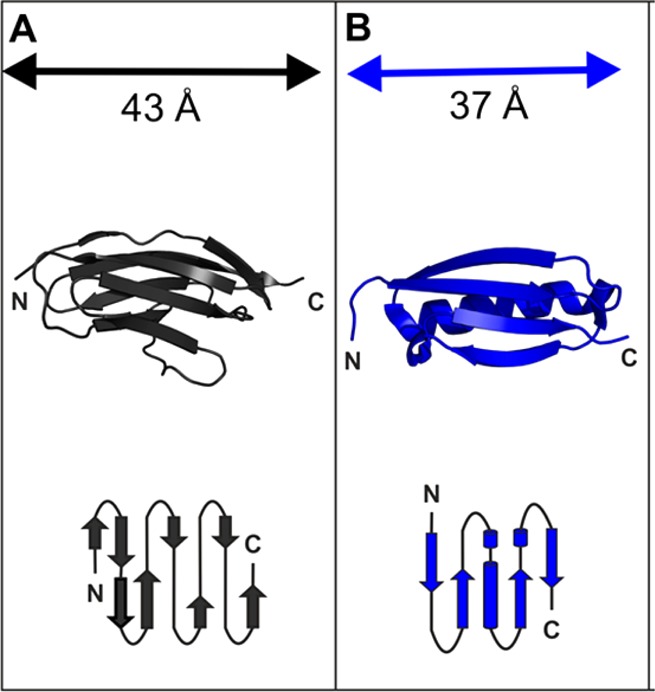

Scheme 1. Globular Proteins Used As Building Blocks in This Study Were (A) I27, PDB Code 1TIT, and (B) Protein L, PDB Code 1HZ6.

β-Strands are shown as arrows, and α-helices are represented as ribbons (top) or cylinders in the topology diagrams (below). In the polyprotein constructs, the proteins are connected in tandem via their amino- and carboxy-terminal ends, highlighted as N and C.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate (Ru(BiPy)3), ammonium persulfate (APS), guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl), dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium phosphate dibasic, and sodium phosphate monobasic were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further treatment. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) was used throughout the experiments with the exception of SANS experiments, where D2O (Sigma-Aldrich −99.9%) was used instead. Independent of the solvent, experiments were conducted in phosphate buffer 25 mM, pH = 7.4.

(I27)5 and (pL)5 polyprotein constructs were expressed and purified as described previously.38,39 Each polyprotein contained an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag for purification and two terminal cysteine residues for immobilization in AFM experiments. The amino acid sequence of the (pL)539 construct was MH6SS-(pL1)-GLVEAR-GG-(pL2)-GLIEARGG-(pL3)-GLSSARGG-(pL4)-GLIERARGG-(pL5)-CC and for (I27)538 was (H)6-SS-(I271)-VEAR-(I272)-LIEAR-(I273)-LSSAR-(I274)-LIEARA-(I275)-CC.

Methods

Sample Preparation

The protein was dissolved into phosphate buffer (PB) followed by addition of Ru(BiPy)3 and APS stock solutions to achieve a final concentration of 100 mg/mL polyprotein, 100 μM Ru(BiPy)3 and 50 mM APS in PB 25 mM. This composition was used throughout, except for the SAXS experiments, where solutions of 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL of protein were used instead.

Gelation

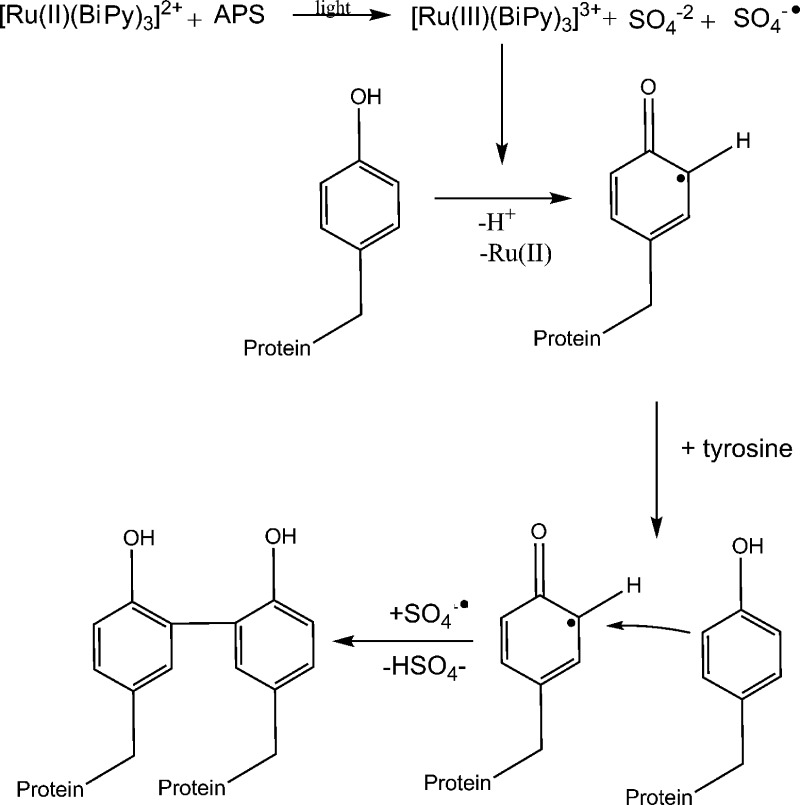

The hydrogels were obtained by exposure to a white light source, 20 W (6400 K) MCOB LED cluster for 5–30 min, depending on the sample. The photochemical-triggered reaction promotes the formation of dityrosine bonds (Scheme 2).40 I27 (PDB: 1TIT)41 has one tyrosine residue (160 Å2 solvent exposed surface area (SASA)42) and protein L (PDB: 1HZ6)43 has three tyrosine residues (51, 71, and 77 Å2 SASA).42 Gelation was confirmed by visual inspection and the appearance of the expected maximum at 400 nm upon ultraviolet irradiation (see Supporting Information (SI), Figures S1–3)

Scheme 2. Reaction Mechanism for the Photochemical-Triggered Reaction Which Promotes the Formation of Dityrosine Bonds40.

Rheology

Rheological measurements were conducted using a Rheometrics SR-500 stress-controlled rheometer (Rheometrics Inc., U.S.A.) equipped with a parallel plate (10 mm radius) geometry. Time sweep experiments were run at an angular frequency and shear stress of 6.28 rad/s and 5 Pa, respectively. Low viscosity (5 ctSt) paraffin oil (Sigma-Aldrich) was placed around the geometry edges to prevent evaporation. The measurements were performed at room temperature, ∼23 °C.

There are several criteria in the literature for determination of the gelation point. The crossover point of G′ and G″ is a commonly used criterion, signaling that elastic behavior dominates the overall rheological response.44 In this work, the pregelation data does not allow for a clear observation of the crossover point and we therefore arbitrarily define the gel point as where G′ reaches a value of 10 Pa (i.e., raises above noise level).45−47

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DSC scans were collected on a TA Q20 DSC with a refrigerated cooling system (RCS90, TA, Inst.). Each aluminum sample pan (Tzero pans, TA, Inst.) contained 20 mg of material. An empty pan was used as reference. The samples were heated from 5 to 85 °C at 10 °C/min, allowed to equilibrate for 5 min and then cooled from 85 to 5 °C at 10 °C/min. Two sequential heat–cool scans were conducted to evaluate the reversibility of the process. The experiments were conducted in duplicate.

Small-Angle Scattering

SAXS measurements were performed at Diamond Light Source beamline B21 using a BIOSAXS robot for sample loading and a PILATUS 2 M (Dectris, Switzerland) detector. The X-ray wavelength used was 0.1 nm corresponding to an energy of 12.4 keV, and the sample–detector distance was 4.018 m, giving an accessible q-range of 0.05–4.0 nm–1. Data were reduced, and solvent and capillary contributions were subtracted using the DawnDiamond software.

SANS measurements were conducted on the variable geometry, time-of-flight diffractometer instrument SANS 2d at ISIS Spallation Neutron Source (Didcot, UK). Incidental wavelengths from 1.75 to 16.5 Å were used with a sample detector distance of 4 m, corresponding to a total scattering vector range q from 4.5 × 10–3 to 0.75 Å–1. The sample temperature was controlled by an external circulating thermal bath (Julabo, DE). The scattering intensity was converted to the differential scattering cross-section in absolute units using standard procedures. Samples were loaded and gelled in 1 mm path-length optical quartz cells.

SAS Fitting

All data were fitted using SASview software.48

SANS

All polyprotein hydrogel data were fitted using a combination of two Lorentzian functions in order to describe a low-q and high-q signal.

| 1 |

where ξ1,2 are the respective correlation lengths, A and B are scale factors, and m and n are the exponents for the Lorentzian function and bg is the incoherent background.47,49−52

SAXS

The data was fitted using the Guinier/Porod generalized model53

| 2 |

| 3 |

where, s, is a dimensional variable; G, the Guinier scale; m, the Porod exponent, and

as described in ref. (53).

Results and Discussion

Choice of Protein Building Block

Since the first report almost 20 years ago,54 many different proteins have been unfolded using force spectroscopy. Consequently, the relationship between mechanical strength (i.e., the force at which a protein unfolds at a certain extension rate) and protein structure and thermodynamic or kinetic stability is fairly well understood.28,29 Such studies have shown that mechanical strength can be largely attributed to the type of protein secondary structure and its topology relative to the pulling direction. For example, proteins with proximal parallel terminal β-strands tend to be mechanically strong, whereas all-α proteins are mechanically weak when extended from their termini. To examine the macro- (rheology) and nanoscale (SAXS, SANS) material properties of hydrogels derived from proteins that exhibit high and moderate mechanical strength we used chemical cross-linking, through the formation of dityrosine bonds, to form networks of pentameric polyproteins of I27 ((I27)5) and protein L ((pL)5). The mechanical behavior of these polyproteins has been previously characterized in our groups.39,55 I27 (Scheme 1A) a single Ig-like domain from the giant muscle protein titin has become a paradigm for the field.56,57 Protein L is a bacterial surface protein known to bind the light chain of IgGs for immune evasion58 and, unlike I27, it has no known mechanical function (Scheme 1B). Despite this, and its simple topology, protein L is also relatively mechanically strong.28,39 “Beads-on-a-string” polymeric variants of these single domain proteins were used in this study because (i) of the availability of a large data set on their mechanical properties; (ii) the potential to increase the diversity of the material properties of the resultant hydrogels further; and (iii) the ability to produce defined heteropolymeric polyproteins with changes in either cross-linking-site density or protein type. For example, network growth can be modulated both by controlling the shape of the construct (the number of protein repeats) and also the distribution of cross-linking sites within the construct. (Note: I27 only has a single binding site. It is not possible for I27 monomers to form a chemically cross-linked hydrogel by the route employed in this work.) In addition to chemical cross-linking at defined sites, we also examined the importance of intermolecular interactions in a hydrogel network composed of two different building blocks (a 1:1 w/w blend of (I27)5 and (pL)5), referred to herein as (I27)5/(pL)5).

Rheological Studies of Gelation

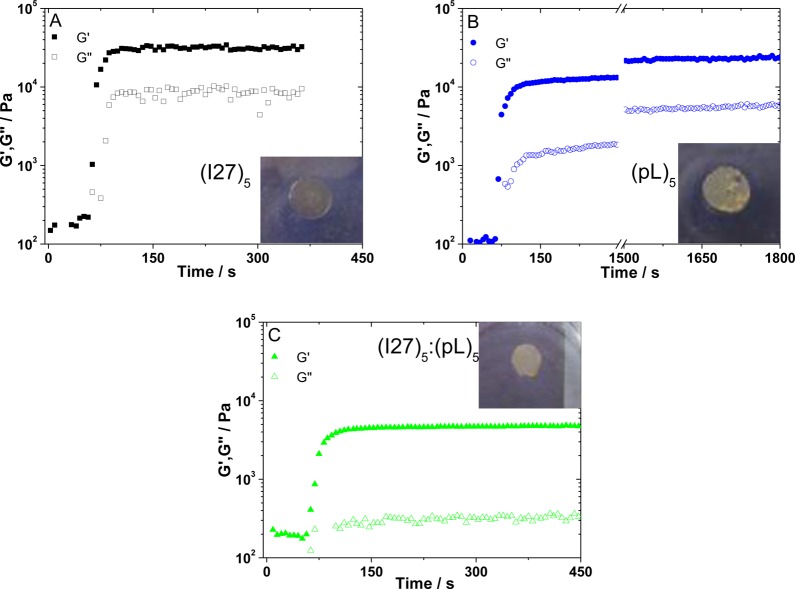

We first investigated how the rheological properties of the solution evolved during gelation. Rheological characterization is important for gaining information on the viscoelastic properties of the polyprotein-based hydrogels, providing a guide to their potential use.5,9 The typical time dependence of the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli for the gelation of the (I27)5, (pL)5 and (I27)5/(pL)5 are shown in Figure 1A–C. In the experiment, the samples were exposed to the light source 60 s after the start of the experiment. The sudden increase in both G′ and G″ after this time signals the start of gelation. The hydrogels are formed almost instantly and, with the exception of the (pL)5 hydrogels (Figure 1B), stable values of G′ are reached within 200 s of gelation. The (pL)5G′ values follow an asymptotic behavior without reaching a plateau within the time frame observed (up to 1 h). Comparing stable G′ values, taken after 200 s of gelation (1800 s for (pL)5), both homopolyproteins showed similar averaged values (27 ± 6 kPa and 26 ± 4 kPa for (I27)5 and (pL)5 hydrogels, respectively). Frequency sweeps for these gels show a plateau for G′ extending over the frequency range studied (Figure 2), the expected behavior for chemical gels.59 The G″ values reached a stable value of 5.5 ± 3.4 and 6.0 ± 1.1 kPa for (I27)5 and (pL)5 hydrogels, respectively. As the network backbone of the polyprotein hydrogels are formed by a chain of five rod-like globular proteins, the similar value of G′ and G″ would be expected for a similar cross-link density unless the gelation process generated spatially distinct networks. As discussed below (SAXS analysis), (I27)5 polyproteins are monodisperse in solution, leading to fast reaction times, while (pL)5 shows polydispersity. The asymptotic behavior observed during the gelation of (pL)5 can thus be attributed to continuous aggregate rearrangement that interferes with binding site access during photogelation. However, upon reaching a steady-state condition, G′ is similar for both polyproteins. The blend ((I27)5/(pL)5) produced a weaker hydrogel (G′ = 7.6 ± 1.4 kPa and G″ = 0.63 ± 0.14 kPa, Figure 1C). The reduced G′ and G″ value for (I27)5/(pL)5 relative to the homopolyproteins may be ascribed to the formation of extensive noncovalent interactions between I27 and protein L domains. These interactions are much weaker than permanent covalent bonds and may also affect accessibility to the tyrosine cross-linking sites, leading to an overall weakening of the gel. Therefore, in terms of their rheological properties the homopolyprotein-based hydrogels show higher shear modulus than that of the polyprotein blend hydrogel with no synergistic effect observed.

Figure 1.

Time sweep curves showing the time dependence of the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli for the gelation of the assayed 100 mg/mL polyprotein hydrogels: (A) (I27)5, (B) (protein L)5, and (C) the blend (I27)5/(protein L)5. G′ is shown as filled symbols and G″ as open symbols. After 60 s, the samples were exposed to the light source, marked by the formation of the hydrogel and a sudden increase in both G′ and G″. Insets show pictures of the respective hydrogels, with each sample measuring 10 mm in diameter.

Figure 2.

Shear frequency sweeps for the folded and unfolded hydrogels (A) (I27)5, (B) (protein L)5, and (C) the blend (I27)5/(protein L)5. G′ is shown as filled symbols and G″ as open symbols.

To evaluate how the presence of folded globular proteins in the cross-linked network affects rheological response, we subjected the hydrogels to mechanical loading and unloading cycles (a shear stress ramp from 0 to 1 kPa in 50 s and then back to 0 Pa also in 50 s) using a shear stress rheometer. In a hydrogel composed of unstructured and/or extended elements, for example, inorganic polymers or fibrous proteins, the load/unload cycle would cause stretching/unstretching of the polymeric backbone. By contrast, a globular protein would resist stretching as long as it remained native-like.

The resultant stress–strain curves for (I27)5, (pL)5, and (I27)5/(pL)5 (Figure 3) show that the energy dissipated in Pa (J/m3) over each cycle (i.e., the area enclosed by the loading and unloading stress/strain curves) for each hydrogel is distinct across a wide range of applied shear stress (the insets to Figure 3 shows the loop area dependence vs shear stress applied, which follows a logarithmic dependence (linear behavior in a double-log plot)). (I27)5 hydrogels show the least hysteresis, (0.93 ± 0.36 Pa) followed by (pL)5 (2.15 ± 0.04 Pa) and finally the blend (3.3 ± 0.1 Pa) at 1 kPa stress. In a perfectly elastic system, where no dissipative deformations take place, the area under a stress–strain curve loop is zero. The presence of hysteresis, observed as a nonzero loop area, therefore, implies the presence of reversible dissipative deformation. These can arise from a myriad of sources and include topological reorganization of the hydrogel network (entanglements), nonspecific contributions from the network itself, and the breaking of weak noncovalent transient bonds. As the hydrogels studied here are composed of globular proteins, we expect a minimal contribution of entanglements, in contrast to nonglobular fibrous protein hydrogels, such as those made from gelatin.46,60 Hence, the dominant expected differential factor for the hysteresis is expected to be the disruption of weak transient interactions,26 which includes both the mechanical robustness of the protein fold and intermolecular interactions.5,15,26,27,61 In this respect, it is interesting to note, at the loading rates used in AFM experiments, that I27 and protein L are known to be mechanically robust proteins38,39,55 and that I27 is 30% stronger than protein L. However, as discussed above, hysteresis is also affected by the nature of the network and the difference in transparency between (I27)5 and (pL)5 hydrogels (Figure 1, insets) suggests differences in the network morphology.60 As discussed further below, SAXS data shows the presence of aggregates in solution for (pL)5, which will be incorporated into the network as the system gels. These aggregates are maintained by weak transient interactions, which add another source of dissipative deformation. The effect of another source of transient interactions to the network is illustrated by the observation that the blend shows greater hysteresis than either of its components in isolation, with an increase in hysteresis of 53% and 254% relative to the (pL)5 and (I27)5 hydrogels.

Figure 3.

Strain–stress curve sweeps for the assayed polyprotein hydrogels: (I27)5, (protein L)5, and the blend (I27)5/(protein L)5. Inset shows the dependence of the loop area with the applied stress.

To confirm that these data report the resilience of the native fold, we formed hydrogels (I27)5, (pL)5, and (I27)5/(pL)5 cross-linked in the unfolded state by addition of 3 M guanidinium hydrochloride (GuHCl) to the cross-linking solution as the midpoint of denaturation of I27 and protein L is 1.5 and 2.4 M GuHCl, respectively.38,62,63 As expected, the effect of unfolding on the hydrogels was marked. The hydrogel formed from unfolded (I27)5 is much weaker compared to the analogous folded hydrogel (G′folded 27 ± 6 kPa and G′unfolded 2.7 ± 0.5 kPa, Figure 2). This already shows the importance of the native state of the protein to the hydrogel’s rheological behavior. The hysteresis loop area at a shear stress of 250 Pa increased ∼86-fold for (I27)5 (from 0.07 ± 0.03 to 6 ± 2 Pa) upon denaturation. The large increase of loop area for the (I27)5 hydrogels is in accord with the hypothesis that hydrogel gel properties are altered due to the differences in building blocks (compact and mechanically resistant in the native state and expanded and extensible in the unfolded state). The hydrogels from denatured (pL)5 were particularly weak (G′ = 51 ± 9 Pa), their frequency sweeps showed strong frequency dependency (Figure 2), which is more characteristic of a physical gel or particle suspensions. This produced a material incapable of supporting loads of 100 Pa or more; therefore, it was not possible to quantify the increase in hysteresis. Denatured (I27)5/(pL)5 also formed a much weaker hydrogel relative to folded (I27)5/(pL)5 (G′unfolded = 1.0 ± 0.2 kPa vs G′folded = 6 ± 2 kPa, respectively; Figure 2). Similarly, the hysteresis observed in the stress–strain curve loop for the denatured (I27)5/(pL)5 hydrogel showed a 552-fold increase relative to its folded counterpart (21 ± 1 and 0.038 ± 0.022 Pa, at 100 Pa of stress the largest load supported by the denatured blend). The data above contrast with that reported by Seung-wuk and co-workers64 who observed that the presence of GuHCl reduced hysteresis. Interestingly, the elastomeric hydrogels produced by Seung-wuk were obtained from unstructured proteins in the presence of GuHCl. For these unstructured proteins it was suggested that the denaturant suppressed transient noncovalent interactions in the resting state, reducing the amount of hysteresis observed due to a reduction in the breakup/reformation of weak transient interactions upon stretching/relaxation cycles.

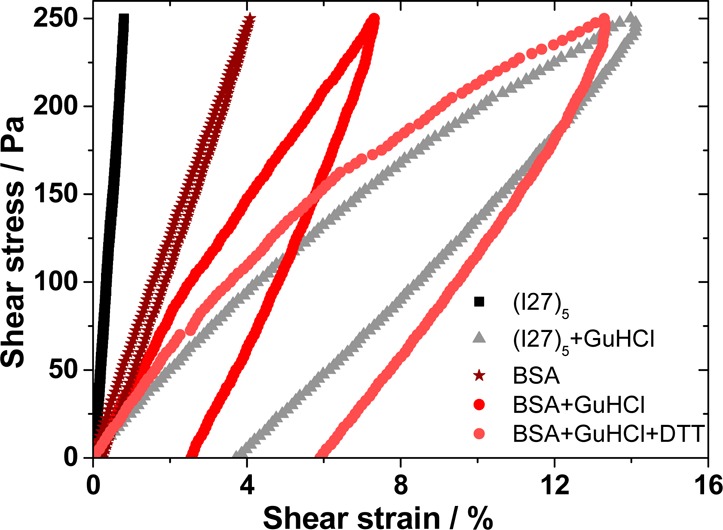

In order to highlight the importance of the change in extensibility of the building block to the mesoscale rheological properties of the hydrogel, the same experiment was conducted with bovine serum albumin (BSA). BSA is a 583-residue globular protein that forms 17 disulfide bonds,65 limiting its extensibility in the unfolded state. Unlike I27, monomeric BSA can be cross-linked via dityrosine bonds due to the presence of 8 surface-exposed tyrosine residues42 (as defined by the ratio of the surface area to random coil area exceeding 20%). The high frequency of covalent, yet redox sensitive disulfide bonds within BSA monomers allows formation of hydrogels from three distinct states: the folded protein, an unfolded but nonextensible state (addition of GuHCl to the cross-linking solution) and the fully unfolded state (addition of GuHCl and reductant (DTT) to the cross-linking solution). Figure 4 shows a comparison of (I27)5 and BSA-folded and -unfolded hydrogels. In addition, Figure S4 shows BSA in the presence of only DTT. The area obtained for folded BSA was 0.73 ± 0.04 Pa, 10× larger than that for (I27)5. No change is measured upon addition of only DTT (Figure S4). However, unfolding of BSA by addition of GuHCl, increased hysteresis 5.5-fold (increasing to 4 ± 2 Pa), producing a hydrogel with apparently distinct properties to that of unfolded (I27)5. Upon addition of DTT, the loop area for BSA increased to 10 ± 3 Pa; a 13.7-fold increase from the native state. This increase is still about 10× smaller than the increase observed for (I27). The hydrogels’ malleability were also altered significantly. As can be seen in the stress–strain experiment run at 250 Pa, the maximum strain jumped to 15 ± 5% from 1.1 ± 0.4% for (I27)5 hydrogels, while for BSA, the changes were smaller, changing from 4.9 ± 0.2% to 7 ± 2% upon partial denaturation (Figure 4). Upon full denaturation, the maximum strain reached for BSA, 14 ± 1%, is comparable with the maximum strain observed for (I27)5, 15 ± 5%. The shear modulus (G = τ/γ) can be extracted from the slope of the linear part of a stress vs strain curve and provides an insight into the changes undergone by the hydrogel. As can be seen on Figure 4, the slope decreases with the extent of the unfolding; for (I27)5G changes from 31 to 2.1 kPa upon denaturation, whereas for BSA it changes from 6.1 to 3.4 kPa under GuHCl and finally to 2.5 kPa upon full denaturation under GuHCl/DTT. As can be seen when comparing the hysteresis loop area for (I27)5 and BSA gels upon denaturation, the maximum strain and the shear modulus are very similar. Under denaturing conditions, the protein fold plays no role because the system can be described as being formed by random coils. In native conditions, where the protein fold contributes to the hydrogels’ rheological behavior, (I27)5 shows high shear modulus, negligible hysteresis, and low stretchability when compared to BSA, highlighting the impact of the I27 fold to the gel bulk properties.

Figure 4.

Strain–stress curve sweeps for the folded and denatured hydrogels for polyprotein (I27)5 and bovine serum albumin (BSA).

It is worth noting that the rheological properties of the polyprotein hydrogels are strongly dependent on weak transient interactions that can be disrupted by changes to the medium, including the temperature or by the presence of cosolutes or cosolvents. This may be an attractive property that could be exploited as a “switch” in the folded protein hydrogels, where the level of hysteresis could be largely increased by disruption of the protein fold and redox state.

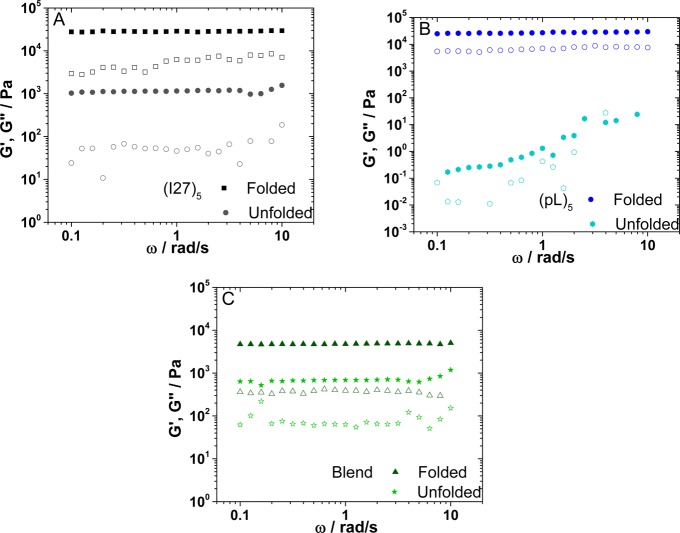

Stability of Hydrogels

The hydrogels formed from (I27)5 and (pL)5 are shown in the insets of Figure 1. To verify that the proteins in the cross-linked hydrogels remained natively folded (a requisite of harnessing the functions of proteins), we performed differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) on the protein solution prior to, and at the end point of, gelation (Figure 5). Each DSC thermogram shows the presence of folded protein in both solution and hydrogels, evidenced by an endothermic peak, which we attributed to the thermal unfolding of the protein. For (pL)5 and (I27)5 hydrogels, the position of the unfolding peaks show negligible differences between the solution and hydrogel phases: 54 and 51 °C for (I27)5 and 57 and 54 °C for (pL)5.

Figure 5.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of (A) (I27)5 and (B) (protein L)5 in solution (open symbols) and in the hydrogel (filled symbols).

Appearance and Structure of Hydrogels

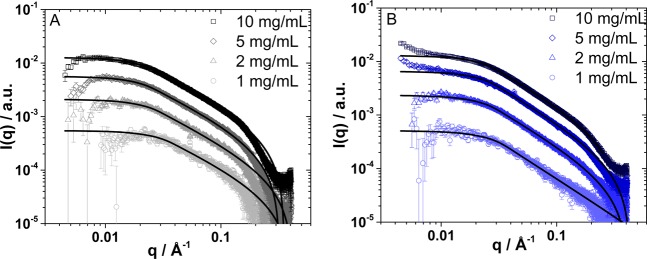

(I27)5 forms a translucent hydrogel (Figure 1 A, inset), while (pL)5 (Figure 1B, inset) and the (I27)5/(pL)5 hydrogels (Figure 1C, inset) were whitish and more opaque, suggesting the presence of aggregates large enough to scatter visible light (hundreds of nanometers). To describe these structures in greater detail and to investigate whether the structure and dispersity of the protein constructs prior to cross-linking affected the structure of the hydrogels, we examined the morphologies of the polyproteins in solution (at 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL) by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Comparison of the SAXS data (Figure 6) shows that (I27)5 and (pL)5 constructs have similar shapes in solution. For (I27)5, the data follows an exponent of −1 at mid-q range, and fitting the data with the Guinier approximation53 results in a radius of gyration (Rg) of ∼50 Å. The data for (pL)5 shows a smaller exponent of −1.3, yielding an Rg = 45 Å. The Rg of (I27)5 can be interpreted as a rod-like structure of approximately 170 Å in length and 10 Å in radius, which is compatible with the dimensions of five repeating and aligned I27 domains, where a single I27 domain can be described as an ellipsoid with principal lengths of 34 × 12 × 8 Å.41 Therefore, a cylinder composed of five aligned I27 domains would have an Rg of ∼50 Å. The main difference between the polyprotein solutions appeared at concentrations of 2 mg/mL and above, where (pL)5 solutions showed an upturn at low q (Figure 6). This indicates that this polyprotein forms aggregates at these concentrations.66−68

Figure 6.

SAXS curves and fits for (A) (I27)5 and (B) (protein L)5 in phosphate buffer solution at concentrations of 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL. The data shows the scattered intensity I(q) as a function of q.

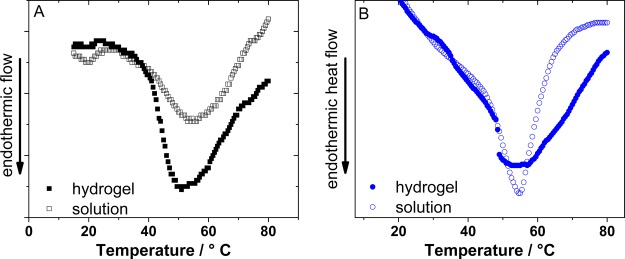

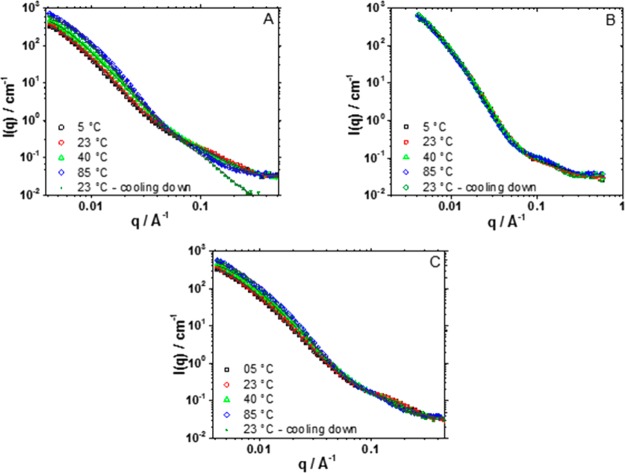

To characterize the mesoscopic structure of the hydrogels, SANS data was initially accumulated at 23 °C. The curves can be described by two scattering signals. A high-q to mid-q signal down to ∼0.08 Å–1 and a low-q signal covering the rest of the range. Each of these two signals can be accurately described by a Lorentzian function which provides two parameters of particular interest (eq 1). The first is a correlation length (ξ), which in the case of cross-linked hydrogels can be described as the length of the scattering center.47,51 The second is the Lorentzian exponent, which carries information about the dimensionality of the scattering center.53

The fit to the data for (I27)5 hydrogels yielded ξ-values of 200 and 10 Å for the signals at low-q and high-q ranges, respectively. As mentioned before, the SAXS data for the (I27)5 in solution suggests that the polyprotein construct is a rod of ∼170 Å in length, allowing the building block for the hydrogel (i.e., low-q signal) to be attributed to the polyprotein itself. The Lorentzian equation describes a distribution, in this case, a mass distribution along the hydrogel volume. Therefore, this model does not provide information about shape, only a characteristic length. Some insight on the shape, however, can be obtained from the Lorentzian exponent. The low-q Lorentzian exponent (3.3) suggests a surface fractal, 3 < Df < 4,66,69 which is consistent with a rough surface, instead of a well-defined sharp surface (Df = 4). Such volume fractals objects are often seen in some types of globular protein hydrogels.70−72 To examine the extent to which this mesoscopic structure is determined by the structure of the building block (i.e., folded or unfolded protein) SANS data were also accumulated at a range of temperatures (5, 40, and 85 °C) that spanned the thermal unfolding temperature of both proteins (see DSC thermograms in Figure 5). After data accumulation at these temperatures, the samples were cooled to 23 °C and reanalyzed (Figure 7). For the (I27)5 polyprotein-based hydrogel, ξ shows little change from 5 to 23 °C (∼200 Å) but it was irreversibly reduced to 188 and 164 Å at 40 and 85 °C (a value of 168 Å is obtained upon cooling to 23 °C). The low-q Lorentzian exponent suffers a much less significant change to 3.5 from 3.3 upon heating from 23 to 85 °C. This observation suggests an irreversible shrinking of the scatterer center, leading to a smaller and slightly more compact structure. Syneresis, however, was not visually observed on the recovered samples after the experiment. The exponent at high-q range was found to be much more sensitive to the temperature increase changing from 2.2 to 3.5.

Figure 7.

SANS curves and fits for (A) (I27)5, (B) (protein L)5, and (C) (I27)5/(protein L)5 showing the scattered intensity I(q) as a function of q. Data is shown for the temperatures 5, 23, 40, and 85 °C, followed by subsequent cooling to 23 °C.

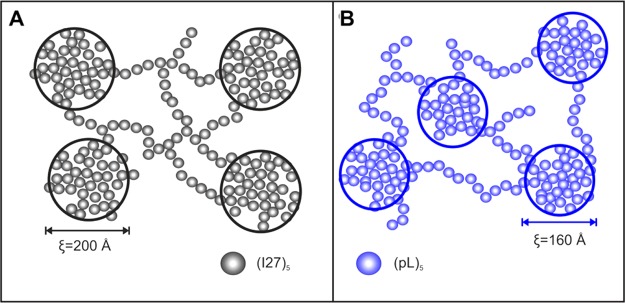

A similar analysis was performed for (pL)5 hydrogels: yielding low- and high-q ξ values of 161 and 5.0 Å at 23 °C, significantly shorter than that observed for the (I27)5. The low-q Lorentzian exponent was found to be 3.4, also suggesting a slightly more compact structure than that observed for (I27)5 hydrogels. For (pL)5, a ξ of 172 Å was obtained at all temperatures assayed. As this ξ-value is similar to that observed for thermally unfolded (I27)5 hydrogels (164 Å), these data could indicate that (pL)5 is denatured, but DSC thermograms (Figure 5) confirmed the presence of folded protein in the hydrogels. An alternative interpretation is that the aggregates in (pL)5 solutions at a concentration ≥5 mg/mL observed using SAXS act as seeds for network formation, influencing the hydrogel’s network. The SANS data coupled with the observation that (pL)5 hydrogels are more opaque (indicating the presence of aggregates of 100s nm in size and, therefore, outside of the SANS range) suggests a network formed of compact centers bundled together and grown out of the aggregates already present in the solution (Scheme 3). As discussed before, SAXS data showed that (pL)5 in solution forms aggregates at concentrations of 5 mg/mL and above (Figure 6). These aggregates can lead to the formation of a heterogeneous network, as they act as nucleation points, causing the gel’s network to be more localized around the (pL)5 aggregates. This favors the formation of large scattering centers surrounded by empty regions instead of a more dispersed, homogeneous morphology (Scheme 3). This heterogeneous distribution, in turn, leads to higher opacity.47,73

Scheme 3. Schematic Representation of the Mesoscopic Structure of the Network Formed by the Polyprotein-Based Hydrogels from (A) (I27)5 and (B) (protein L)5, Where ξ Is the Correlation Length Obtained from the SANS Data at 23 °C.

The small spheres are a rough simplification of the polyprotein blocks that form the network backbone. The scattering centers are formed by regions of clustered polyproteins that gives rise to scattering curves presented in this work, and they are presented by the circled areas.

The SANS data for the (pL)5/(I27)5 at 23 °C (Figure 7C) follows the same pattern as the single polyprotein hydrogels with a low- and high-q signal, well described by a double-Lorentzian model, yielding ξ and exponent values of ∼173 Å and 3.1 and 5.7 Å and 4 for low- and high-q values, respectively. These values are similar to those obtained for the (pL)5 hydrogels. Visually, however, the blend hydrogel is similar to the translucent and homogeneous (I27)5 hydrogels (Figure 1C, inset), as opposed to the white, semitranslucent (pL)5 hydrogels, indicating the blend’s structure is different, at least, at the mesoscopic level. The blend shows limited sensitivity to the effects of temperature, where a small decrease in ξ, from 175 to 166 Å, is observed when the temperature changes from 40 to 85 °C, whereas for (I27)5, a much larger drop was observed. When compared to (I27)5 or (pL)5 hydrogels, the low- and high-q values obtained for the blend are closer to the values observed for (pL)5 than for (I27)5. For instance, at 23 °C, the ξ for the blend is 174 Å, 172 Å for (pL)5 and 200 Å for (I27)5. This suggests that the protein L is guiding the network build-up at this scale. Protein L is known to bind immunoglobulin G domains.58 Therefore, the network observed for the blend may be formed not by single polyproteins, but by bound I27-pL polyproteins, which result in a network formed by compact aggregates in similar fashion as the single (pL)5 hydrogels, also formed by compact aggregates of (pL)5.

Conclusions

In this work, we aimed to provide insights into the influence of the folded properties of the protein building block on the structural and mechanical bulk properties of protein and polyprotein hydrogels. This was achieved through the study and comparison of the rheological properties and small-angle scattering response of hydrogels obtained from mechanically robust folded globular polyproteins, composed of I27 and protein L. We also compared them to a 1:1 blend of I27 and protein L, to understand the importance of protein interactions to the bulk hydrogel properties. In terms of shear elastic modulus (I27)5 and (pL)5 displayed similar average values, about 24 and 26 kPa, respectively, while the polyprotein blend produced weaker hydrogels, (10 kPa). When looking at the amount of hysteresis observed in a load/unload cycle, a remarkable difference can be observed across the three systems. (I27)5 hydrogels show the lowest level of hysteresis in the conditions assayed, 0.93 at 1000 Pa load under 50 s. (pL)5 shows a large value, 2.15 Pa under the same conditions. This difference may be due to the formation of (pL)5 aggregates in solution, as observed by SAXS, which adds another source of dissipative deformation, through perturbation of the aggregated domains. This highlights not only the importance of both the protein building block and the mechanism of network formation, but also the level of control and variability that can be obtained by modulating the type of interactions accessible to the protein building blocks. A noninteracting, mechanically robust building block such as (I27)5 produces strong hydrogels with a low level of hysteresis, while a mechanically robust building block that is prone to self-aggregation, (pL)5, can also generate strong hydrogels, but with increased levels of hysteresis. Also, in the case of (I27)5 and (pL)5, the network can be severely disrupted by protein unfolding, using chemical denaturants, which could act as an irreversible switch. The importance of the protein fold on the rheological properties was highlighted by comparing (I27)5 and BSA hydrogels in both folded and unfolded conditions. In conditions where the protein is fully denaturated, the values for shear modulus (2.2 vs 2.5 kPa), maximum strain upon deformation (15 vs 14%), and hysteresis (6 vs 10 Pa) are similar for both hydrogels. This demonstrates that, when the folding is suppressed, both gels behave similarly. Under native conditions, the robustness of I27 fold produced stiff and more elastic gels than BSA when comparing the shear modulus (31 vs 6.1 kPa), maximum strain upon deformation (1.1 vs 4.9%) and, specially, hysteresis (0.07 vs 0.73 Pa). Taken together, this study demonstrates the use of folded proteins as building blocks in hydrogels and highlights the potential versatility that can be offered in tuning the mechanical, structural, and functional properties of polyproteins.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by a grant from the Engineering and Physics Sciences Research Council (EP/H049479/1). Dr L. Dougan is supported by a grant from the European Research Council (258259-EXTREME BIOPHYSICS). Experiments at the ISIS Pulsed Neutron were supported by a beam time allocation for SANS 2d from the Science and Technology Facilities Council under Proposal Number RB1520127. The authors thank Diamond Light Source for access to beamline B21 that contributed to the results presented here. This work benefitted from SasView software, originally developed by the DANSE Project under NSF Award DMR-0520547. The authors thank Dr. B. Johnson for the help with adapting the light source to the rheometer, Dr. J. Mattsson and Dr. D. Baker for access and support with the DSC and rheometer, Dr. S. King and Dr. S. Rogers for the support at ISIS.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01877.

Chemical cross-linking of polyprotein hydrogels and rheological properties of the folded and partially unfolded BSA protein (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- DiMarco R. L.; Heilshorn S. C. Multifunctional Materials through Modular Protein Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24 (29), 3923–3940. 10.1002/adma.201200051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen B. D. Engineering materials from proteins. AIChE J. 2013, 59 (10), 3558–3568. 10.1002/aic.14223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peppas N. A.; Hilt J. Z.; Khademhosseini A.; Langer R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18 (11), 1345–1360. 10.1002/adma.200501612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.; Tang S.; Olsen B. D. Physics of engineered protein hydrogels. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2013, 51 (7), 587–601. 10.1002/polb.23270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han F.; Zhu C.; Guo Q.; Yang H.; Li B. Cellular modulation by the elasticity of biomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4 (1), 9–26. 10.1039/C5TB02077H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlierberghe S.; Dubruel P.; Schacht E. Biopolymer-Based Hydrogels As Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12 (5), 1387–1408. 10.1021/bm200083n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaharwar A. K.; Peppas N. A.; Khademhosseini A. Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111 (3), 441–453. 10.1002/bit.25160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva M. A.; Dreiss C. A. Soft nanocomposites: nanoparticles to tune gel properties. Polym. Int. 2016, 65 (3), 268–279. 10.1002/pi.5051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M. M.; George J. H. Exploring and Engineering the Cell Surface Interface. Science 2005, 310 (5751), 1135–1138. 10.1126/science.1106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol A.; Channe Gowda D.; Urry D. W. Cell adhesion and growth on synthetic elastomeric matrices containing ARG-GLY–ASP–SER–3. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1992, 26 (3), 393–413. 10.1002/jbm.820260309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilshorn S. C.; Liu J. C.; Tirrell D. A. Cell-Binding Domain Context Affects Cell Behavior on Engineered Proteins. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6 (1), 318–323. 10.1021/bm049627q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutolf M. P.; Hubbell J. A. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23 (1), 47–55. 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettles D. L.; Chilkoti A.; Setton L. A. Applications of elastin-like polypeptides in tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010, 62 (15), 1479–1485. 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher D. E.; Mooney D. J.; Zandstra P. W. Growth Factors, Matrices, and Forces Combine and Control Stem Cells. Science 2009, 324 (5935), 1673–1677. 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Cao Y. Protein Mechanics: From Single Molecules to Functional Biomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43 (10), 1331–1341. 10.1021/ar100057a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Kong N.; Laver B.; Liu J. Hydrogels Constructed from Engineered Proteins. Small 2016, 12 (8), 973–987. 10.1002/smll.201502429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrick J. D.; Stokes S.; Bachas-Daunert S.; Moschou E. A.; Deo S. K.; Bachas L. G.; Daunert S. Chemically Tunable Lensing of Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogel Microdomes. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19 (22), 4024–4027. 10.1002/adma.200601969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson G. R.; Andrew Lyon L. Bioresponsive hydrogels for sensing applications. Soft Matter 2009, 5 (1), 29–35. 10.1039/B811620B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bysell H.; Månsson R.; Hansson P.; Malmsten M. Microgels and microcapsules in peptide and protein drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2011, 63 (13), 1172–1185. 10.1016/j.addr.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H. K.; Kiick K. L. Opportunities for Multicomponent Hybrid Hydrogels in Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16 (1), 28–42. 10.1021/bm501361c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwalda S. J.; Boere K. W. M.; Dijkstra P. J.; Feijen J.; Vermonden T.; Hennink W. E. Hydrogels in a historical perspective: From simple networks to smart materials. J. Controlled Release 2014, 190, 254–273. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathaye S.; Mbi A.; Sonmez C.; Chen Y.; Blair D. L.; Schneider J. P.; Pochan D. J. Rheology of peptide- and protein-based physical hydrogels: Are everyday measurements just scratching the surface?. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7 (1), 34–68. 10.1002/wnan.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaieda S.; Plivelic T. S.; Halle B. Structure and kinetics of chemically cross-linked protein gels from small-angle X-ray scattering. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (9), 4002–11. 10.1039/c3cp54219j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saricay Y.; Dhayal S. K.; Wierenga P. A.; de Vries R. Protein cluster formation during enzymatic cross-linking of globular proteins. Faraday Discuss. 2012, 158 (0), 51–63. 10.1039/c2fd20033c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K.; Yamaguchi T.; Osaka N.; Endo H.; Shibayama M. A study of alcohol-induced gelation of [small beta]-lactoglobulin with small-angle neutron scattering, neutron spin echo, and dynamic light scattering measurements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12 (13), 3260–3269. 10.1039/b920187d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv S.; Dudek D. M.; Cao Y.; Balamurali M. M.; Gosline J.; Li H. Designed biomaterials to mimic the mechanical properties of muscles. Nature 2010, 465 (7294), 69–73. 10.1038/nature09024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J.; Mehlich A.; Koga N.; Huang J.; Koga R.; Gao X.; Hu C.; Jin C.; Rief M.; Kast J.; Baker D.; Li H. Forced protein unfolding leads to highly elastic and tough protein hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2974. 10.1038/ncomms3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.; Tych K. M.; Hughes M. L.; Brockwell D. J.; Dougan L. Towards design principles for determining the mechanical stability of proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15 (38), 15767–15780. 10.1039/c3cp52142g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.; Dougan L. Single molecule force spectroscopy using polyproteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41 (14), 4781–4796. 10.1039/c2cs35033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsevell R.; Forman J. R.; Clarke J. Atomic force microscopy: mechanical unfolding of proteins. Methods 2004, 34 (1), 100–111. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatanova J.; Lindsay S. M.; Leuba S. H. Single molecule force spectroscopy in biology using the atomic force microscope. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2000, 74 (1–2), 37–61. 10.1016/S0079-6107(00)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer M. S. Z.; Smith S. B.; Granzier H. L.; Bustamante C. Folding-Unfolding Transitions in Single Titin Molecules Characterized with Laser Tweezers. Science 1997, 276 (5315), 1112–1116. 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt J. R.; Chemla Y. R.; Smith S. B.; Bustamante C. Recent Advances in Optical Tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77 (1), 205–228. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.043007.090225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecek J. Hydrogels: From soft contact lenses and implants to self-assembled nanomaterials. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2009, 47 (22), 5929–5946. 10.1002/pola.23607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooling L. J.; Buck M. E.; Zhang W.-B.; Tirrell D. A. Programming Molecular Association and Viscoelastic Behavior in Protein Networks. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28 (23), 4651–4657. 10.1002/adma.201506216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeburn J.; Zamith Cardoso A.; Adams D. J. The importance of the self-assembly process to control mechanical properties of low molecular weight hydrogels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (12), 5143–5156. 10.1039/c3cs60030k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghobril C.; Rodriguez E. K.; Nazarian A.; Grinstaff M. W. Recent Advances in Dendritic Macromonomers for Hydrogel Formation and Their Medical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (4), 1235–1252. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell D. J.; Beddard G. S.; Clarkson J.; Zinober R. C.; Blake A. W.; Trinick J.; Olmsted P. D.; Smith D. A.; Radford S. E. The Effect of Core Destabilization on the Mechanical Resistance of I27. Biophys. J. 2002, 83 (1), 458–472. 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell D. J.; Beddard G. S.; Paci E.; West D. K.; Olmsted P. D.; Smith D. A.; Radford S. E. Mechanically Unfolding the Small, Topologically Simple Protein L. Biophys. J. 2005, 89 (1), 506–519. 10.1529/biophysj.105.061465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy D. A.; Kodadek T. Chemistry for the analysis of protein–protein interactions: Rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wavelength light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96 (11), 6020–6024. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improta S.; Politou A. S.; Pastore A. Immunoglobulin-like modules from titin I-band: extensible components of muscle elasticity. Structure 1996, 4 (3), 323–337. 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraczkiewicz R.; Braun W. Exact and efficient analytical calculation of the accessible surface areas and their gradients for macromolecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19 (3), 319–333. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. W.; Kim D. E.; Baker D.; Zhang K. Y. J. Structures of the B1 domain of protein L from Peptostreptococcus magnus with a tyrosine to tryptophan substitution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2001, 57 (4), 480–487. 10.1107/S0907444901000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Nijenhuis K. Investigation into the ageing process in gels of gelatin/water systems by the measurement of their dynamic moduli. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1981, 259 (10), 1017–1026. 10.1007/BF01558616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva M. A.; Farhat I. A.; Arêas E. P. G.; Mitchell J. R. Solvent-induced lysozyme gels: Effects of system composition and temperature on structural and dynamic characteristics. Biopolymers 2006, 83 (5), 443–454. 10.1002/bip.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode F.; da Silva M. A.; Drake A. F.; Ross-Murphy S. B.; Dreiss C. A. Enzymatically Cross-Linked Tilapia Gelatin Hydrogels: Physical, Chemical, and Hybrid Networks. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12 (10), 3741–3752. 10.1021/bm2009894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva M. A.; Bode F.; Grillo I.; Dreiss C. A. Exploring the Kinetics of Gelation and Final Architecture of Enzymatically Cross-Linked Chitosan/Gelatin Gels. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16 (4), 1401–1409. 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasview. http://www.sasview.org/ (accessed 15/03/2016).

- Horkay F.; Hammouda B. Small-angle neutron scattering from typical synthetic and biopolymer solutions. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008, 286 (6), 611–620. 10.1007/s00396-008-1849-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda B. SANS from Polymers—Review of the Recent Literature. Polym. Rev. (Philadelphia, PA, U. S.) 2010, 50 (1), 14–39. 10.1080/15583720903503460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bode F.; da Silva M. A.; Smith P.; Lorenz C. D.; McCullen S.; Stevens M. M.; Dreiss C. A. Hybrid gelation processes in enzymatically gelled gelatin: impact on nanostructure, macroscopic properties and cellular response. Soft Matter 2013, 9 (29), 6986–6999. 10.1039/C3SM00125C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Hemar Y.; Hilliou L.; Gilbert E. P.; McGillivray D. J.; Williams M. A. K.; Chaieb S. Nonlinear Behavior of Gelatin Networks Reveals a Hierarchical Structure. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (2), 590–600. 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatter O.; Kratky O.. Small Angle X-ray Scattering; Academic Press: London; New York, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K.; Hara M.; Ikai A. Mechanical unfolding of a2-macroglobulin molecules with atomic force microscope. FEBS Lett. 1996, 385 (1–2), 29–33. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tych K. M.; Hughes M. L.; Bourke J.; Taniguchi Y.; Kawakami M.; Brockwell D. J.; Dougan L. Optimizing the calculation of energy landscape parameters from single-molecule protein unfolding experiments. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 91 (1), 012710. 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.012710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion-Vazquez M.; Oberhauser A. F.; Fowler S. B.; Marszalek P. E.; Broedel S. E.; Clarke J.; Fernandez J. M. Mechanical and chemical unfolding of a single protein: A comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96 (7), 3694–3699. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J.; Williams P. M., Unfolding Induced by Mechanical Force. In Protein Folding Handbook; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, 2008; pp 1111–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Björck L.; Protein L. A novel bacterial cell wall protein with affinity for Ig L chains. J. Immunol. 1988, 140 (4), 1194–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh G. M.; Ross-Murphy S. B. Rheological characterisation of polymer gels. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1998, 23 (3), 533–562. 10.1016/S0079-6700(97)00047-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva M. A.; Bode F.; Drake A. F.; Goldoni S.; Stevens M. M.; Dreiss C. A. Enzymatically Cross-Linked Gelatin/Chitosan Hydrogels: Tuning Gel Properties and Cellular Response. Macromol. Biosci. 2014, 14 (6), 817–830. 10.1002/mabi.201300472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Kiick K. L. Resilin-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications. ACS Macro Lett. 2013, 2 (8), 635–640. 10.1021/mz4002194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. E.; Fisher C.; Baker D. A breakdown of symmetry in the folding transition state of protein L1. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 298 (5), 971–984. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien E. P.; Ziv G.; Haran G.; Brooks B. R.; Thirumalai D. Effects of denaturants and osmolytes on proteins are accurately predicted by the molecular transfer model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105 (36), 13403–13408. 10.1073/pnas.0802113105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M. S.; Wang E.; Joyner K.; Chung T. W.; Jin H.-E.; Lee S.-W. Elastin-Based Rubber-Like Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (7), 2409–2416. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majorek K. A.; Porebski P. J.; Dayal A.; Zimmerman M. D.; Jablonska K.; Stewart A. J.; Chruszcz M.; Minor W. Structural and immunologic characterization of bovine, horse, and rabbit serum albumins. Mol. Immunol. 2012, 52 (3–4), 174–182. 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda B.Probing Nanoscale Structures - The SANS Toolbox. National Institute of Standards and Technology; www.ncnr.nist.gov/staff/hammouda/the_SANS_toolbox.pdf, 2008.

- Kaieda S.; Plivelic T. S.; Halle B. Structure and kinetics of chemically cross-linked protein gels from small-angle X-ray scattering. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (9), 4002–4011. 10.1039/c3cp54219j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda B. The mystery of clustering in macromolecular media. Polymer 2009, 50 (22), 5293–5297. 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King S. M.Modern Techniques for Polymer Characterisation; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donato L.; Garnier C.; Doublier J.-L.; Nicolai T. Influence of the NaCl or CaCl2 Concentration on the Structure of Heat-Set Bovine Serum Albumin Gels at pH 7. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6 (4), 2157–2163. 10.1021/bm050132q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosal W. S.; Clark A. H.; Ross-Murphy S. B. Fibrillar β-Lactoglobulin Gels: Part 3. Dynamic Mechanical Characterization of Solvent-Induced Systems. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5 (6), 2430–2438. 10.1021/bm0496615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkema J. M. S.; van Vliet T. Concentration dependence of dynamic moduli of heat-induced soy protein gels. Food Hydrocolloids 2004, 18 (3), 483–487. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2003.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souguir H.; Ronsin O.; Larreta-Garde V.; Narita T.; Caroli C.; Baumberger T. Chemo-osmotically driven inhomogeneity growth during the enzymatic gelation of gelatin. Soft Matter 2012, 8 (12), 3363–3373. 10.1039/c2sm07234c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.