Abstract

Objective

To determine factors affecting cognition and identify predictors of long-term cognitive impairment following carotid revascularization procedures.

Background

Cognitive impairment is common in older patients with carotid occlusive diseases.

Methods

Patients undergoing carotid intervention for severe occlusive diseases were prospectively recruited. Patients received neurocognitive testing before, 1, and 6 months after carotid interventions. Plasma samples were also collected within 24 hours after carotid intervention and inflammatory cytokines were analyzed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed to identify risk factors associated with significant cognitive deterioration (>10% decline).

Results

A total of 98 patients (48% symptomatic) were recruited, including 55 patients receiving carotid stenting and 43 receiving endarterectomy. Mean age was 69 (range 54–91 years). Patients had overall improvement in cognitive measures 1 month after revascularization. When compared with carotid stenting, endarterectomy patients demonstrated postoperative improvement in cognition at 1 and 6 months compared with baseline. Carotid stenting (odds ratio 6.49, P = 0.020) and age greater than 80 years (odds ratio 12.6, P = 0.023) were associated with a significant long-term cognitive impairment. Multiple inflammatory cytokines also showed significant changes after revascularization. On multivariate analysis, after controlling for procedure and age, IL-12p40 (P = 0.041) was associated with a higher risk of significant cognitive impairment at 1 month; SDF1-α (P = 0.004) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (P = 0.006) were independent predictors of cognitive impairment, whereas interleukin-6 (P = 0.019) demonstrated cognitive protective effects at 6 months after revascularization.

Conclusions

Carotid interventions affect cognitive function. Systemic biomarkers can be used to identify patients at risk of significant cognitive decline postprocedures that benefit from targeted cognitive training.

Keywords: carotid endarterectomy, carotid interventions, carotid stenosis, carotid stenting, cognitive function, cytokines, inflammatory biomarkers, outcome

With the aging population, it is expected that more patients experience cognitive dysfunction. Cognitive impairment significantly impacts patients, families, and our healthcare system.1 Postoperative cognitive decline has been observed in patients undergoing surgical procedures,2–6 and patients with severe carotid atherosclerotic disease are at the highest risk for cognitive impairment. Carotid revascularization is effective in stroke prevention and to improve cortical thinning in appropriately selected patients.7 However, several studies have detected cognitive decline in a significant number of patients who underwent carotid artery interventions, including carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid stenting (CAS) procedures.4–6,8 Age and microembolization have been suggested to be potentially associated with such declines, but identifying clear risk factors for cognitive decline is an important step to mitigate the risks in future patients.

Systemic biomarkers represent a unique opportunity to serve as indicators of clinically important outcomes. Previous studies have associated inflammatory biomarkers to poor cognitive performance. However, these studies have primarily evaluated relatively healthy individuals9,10 or subjects with known causes for severe cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease.11–13 Increasing evidence supports the ability of the central nervous system (CNS) to incite an inflammatory response to a variety of injuries including ischemia, trauma, and viral infections.14 Moreover, the leaky blood-brain barrier in neurodegenerative diseases has been identified as a route of entry for immune cells to the CNS.15 Recently, inflammatory cytokines have been proposed as predictors of postoperative surgical outcomes.16,17 Whether systemic biomarkers can be utilized to predict cognitive changes after carotid interventions has not been investigated. We have previously identified that 40% of patients undergoing carotid interventions for severe occlusive disease experience further cognitive decline. In this study, we aim to evaluate the predictive potential of systemic cytokines in significant cognitive dysfunction after carotid interventions.

METHODS

Subjects Recruitment

The Stanford University Investigational Review Board (IRB) and the Palo Alto VA Research and Development Committee approved this study. A total of 98 patients undergoing CEA or CAS interventions at the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System were prospectively recruited. Indication for intervention follows the routine practice guidelines, in that patients with >80% asymptomatic carotid stenosis or >60% of symptomatic carotid stenosis (based on NASCET (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial criteria) are eligible for carotid revascularization procedures. CAS is reserved for high-risk patients, namely prior neck surgery or radiation, high carotid bifurcation above C2 level, or severe cardiopulmonary comorbidities with a reversibility on persantine thallium stress test or home oxygen requirement. All patients signed an IRB-approved informed consent. Demographics and risk factors were recorded. Preoperative and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with diffusion-weighted sequence were performed to identify procedure-related embolization. Patients also received a neurocognitive battery from a trained study coordinator 2 weeks before, and 1 and 6 months after carotid intervention to assess cognitive functions. Blood collection was performed within 24 hours of carotid intervention from an arterial line.

Cognitive Assessment

The cognitive assessments tested a wide range of cognitive functions, including attention, executive function, verbal memory, verbal fluency, and visuo-spatial memory. Mini-Mental State Exam was performed to assess gross cognition and screen patients for severe cognitive deficits. The key outcome measure was the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), to assess verbal memory. RAVLT is a word -learning test that assesses declarative memory. It consists of a list of 15 words read to the patient, with the patient asked to recall as many words as possible after the list has been read. This is repeated for 5 trials, with the sum of number of words successfully recalled during these trials taken as the outcome score. Parallel forms of RAVLT were used to mitigate practice effect. The test battery is consistent with recommendations made by the consensus statement on neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiovascular surgery,18 and also NINDS.19 Cognitive decline was defined as negative change in RAVLTsum of trials from postop to preop tests. Significant cognitive decline was defined as >10% decrease in cognitive score compared with preoperative assessment. To avoid anesthetic and surgical effects, we evaluated postop change at 1 month after interventions. Given our older patient population, a natural age-related decline is expected in our cohort. Therefore, a 6-month follow-up was chosen to assess long-term procedure-related changes.

Plasma Analysis

Plasma was isolated using gradient density centrifugation. Briefly, samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm, at 4°C for 15 minutes, and the plasma layer was removed, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C before analysis of complete set of samples. The Luminex magnetic bead-based assay from the Human Immune Monitoring Center at Stanford University was used to analyze the plasma samples. Human cytokine magnetic-plex were purchased from eBiosciences/Affymetrix and used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Plates were read using a Luminex 200 instrument to measure medium florescence intensity (MFI). Cytokine concentration (pg/mL) was calculated with standard controls curve fitting and bead counts, using quality control cytokine samples as a reference.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed, and results were expressed as frequency and percentages or mean and range, as appropriate. To compare patients with or without cognitive decline, Pearson chi-square test was used for differences between categorical variables, whereas unpaired Student t test or Mann-Whitney test was used, when appropriate, for continuous variables. Paired t test was used to compare pre and postoperative neurocognitive performance scores. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate association between key risk factors (key demographics, comorbidities, and systemic biomarkers) and significant cognitive decline postoperatively. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify independent associations and a P value <0.05 was considered significant. Variables with a P < 0.15, and also those factors of clinical significance in the univariate analysis were incorporated in the multivariate logistic regression model. Given the general principle of at least 10 events per variable in the multivariate model, variable selection was performed using leaps and bound method to select the best fit model. The SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and STATA version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) statistical packages were used to analyze the data.

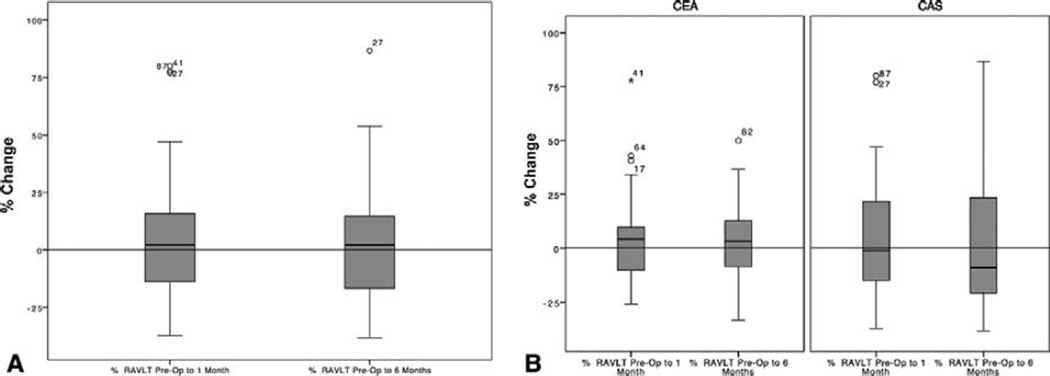

RESULTS

A total of 98 patients with a mean age of 69 years (range 54–91 years) were recruited including 55 CAS and 43 CEA patients. Demographic information, risk factors, and comorbidities are listed in Table 1. Of the cohort, 48% of the patients underwent interventions for symptomatic carotid stenosis and 20% had prior stroke. Among them, 86 patients completed preoperative and 1 month postoperative neurocognitive assessment, and 61 of those also completed the 6-month postoperative neurocognitive assessment. Rather than an expected age-related decline, patients had an overall improvement in cognitive measures 1 month after revascularization, with a mean improvement of 4.7% at 1 month and 1.5% at 6 months postop compared with preop evaluations (Fig. 1A). When comparing with CAS patients, CEA patients demonstrated a nonstatistically significant, postoperative improvement in cognition at 1 and 6 months compared with baseline (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

| Category | n = 98 [n (%)] |

|---|---|

| Age, average yrs (range) | 69 (54–91) |

| Procedure | |

| CAS | 55 (56) |

| CEA | 43 (44) |

| Risk factors and comorbidities | |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 17 (17) |

| Past | 51 (52) |

| Current | 30 (31) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (43) |

| Obesity | 42 (43) |

| CAD | 48 (49) |

| Hypertension | 92 (94) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 25 (25) |

| Congestive heart failure | 13 (13) |

| Key medications | |

| Antiplatelets | 67 (68) |

| Anticoagulants | 6 (6) |

| Satins | 85 (87) |

| Preoperative symptoms | |

| Symptomatic | 47 (48) |

| Prior stroke | 20 (20) |

CAD indicates coronary artery disease.

FIGURE 1.

A, Overall percentage of RAVLT changes. Left: preoperative to 1 month; right: preoperative to 6 months. B, Percentage of RAVLT changes in CAS and CEA groups at 1 and 6 months after interventions.

We observed that 32% of the patients experienced significant verbal memory decline (>10%) 1 month postintervention and 36% had significant decline 6 months after interventions compared with the preoperative scores. Our univariate analysis showed that CAS patients experienced significantly more decline at both 1 and 6 months after interventions (P = 0.048 and 0.026, respectively) (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with cognitive decline at 1 month were less likely to have preoperative symptoms (P = 0.097). Patients who were symptomatic showed a greater improvement between preoperative assessment and 1-month postoperative assessment, with an average increase of 7.9% compared with an average increase of 1.9% for patients without symptoms. Patients older than 80 years of age and smokers were more likely to experience long-term memory decline at 6 months (P = 0.095 and 0.042, respectively), and patients with a history of congestive heart failure (CHF) were less likely to experience long-term memory decline (P = 0.08) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographics and Risk Factors in Patients With and Without Significant Cognitive Decline

| 1 Month Postop | 6 Months Postop | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAVLTsum Changes | No Decline (n = 59) | Decline (n = 27) | P | No Decline (n = 39) | Decline (n = 22) | P |

| CAS | 47.46% | 70.37% | 0.048 | 38.46% | 68.18% | 0.026 |

| Age (average) | 68.93 | 68.85 | 67.82 | 69.45 | ||

| Age (≥80) | 11.86% | 22.22% | 0.213 | 7.69% | 22.73% | 0.095 |

| Diabetes | 45.76% | 44.44% | 0.909 | 46.15% | 45.45% | 0.958 |

| Tobacco | 89.83% | 74.07% | 0.346 | 46.15% | 50.00% | 0.042 |

| CAD | 49.15% | 55.56% | 0.581 | 43.59% | 54.55% | 0.411 |

| CHF | 13.56% | 3.70% | 0.166 | 12.82% | 0.00% | 0.080 |

| CRI | 28.81% | 22.22% | 0.522 | 33.33% | 27.27% | 0.624 |

| Antiplatelets | 71.19% | 59.26% | 0.273 | 71.79% | 63.64% | 0.509 |

| Statins | 81.36% | 92.59% | 0.177 | 82.05% | 90.91% | 0.349 |

| Symptomatic | 52.54% | 33.33% | 0.097 | 43.59% | 45.45% | 0.888 |

| Prior stroke | 22.03% | 14.81% | 0.435 | 10.26% | 18.18% | 0.379 |

CAD indicates coronary artery disease; CRI, chronic renal insufficiency.

Plasma inflammatory markers were evaluated to determine association between significant cognitive decline and systemic cytokine levels. On univariate and multivariate analyses, interleukin (IL)-12p40 was associated with a higher risk of significant memory decline at 1 month [odds ratio (OR) 1.06, P = 0.041] (Table 3). CAS showed a trend, but not significant association with significant decline at 1 month (OR 2.7, P = 0.066). At 6 months after intervention, carotid stenting (OR 6.49, P = 0.020), age greater than 80 years (OR 12.6, P = 0.023), stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha (SDF-1α; P = 0.004), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; P = 0.006) were independent predictors of significant memory decline compared with the preoperative baseline, whereas IL-6 (OR 0.97, P = 0.019) showed a protective effect (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of Significant Cognitive Decline (>10%) 1 Month After Carotid Revascularization

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (vs CEA) | 2.71 | 0.93–7.83 | 0.066 |

| Resistin | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.071 |

| Preop RAVLTsum | 2.54 | 0.89–7.28 | 0.081 |

| IL-12p40 | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 | 0.041 |

| Age >80 yrs | 2.70 | 0.67–10.85 | 0.160 |

TABLE 4.

Predictors of significant Cognitive Decline at 6 Months After Carotid Revascularization

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDF-1α | 1.0001 | 1.00004–1.0002 | 0.004 |

| TNF-α | 1.06 | 1.02–1.10 | 0.006 |

| CAS | 6.50 | 1.04–31.28 | 0.020 |

| Age >80 yrs | 12.71 | 1.43–112.87 | 0.023 |

| Preop RAVLTsum | 4.36 | 0.87–21.73 | 0.073 |

| IL-6 | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.019 |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that carotid stenting and age are independent predictors for long-term significant decline in cognitive assessment after carotid interventions. We also show that systemic cytokines can provide valuable information on postoperative cognitive changes. To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study to evaluate the predictive ability of systemic biomarkers on carotid revascularization-related cognitive changes.

Several studies have evaluated changes in cognitive function after carotid interventions. Picchetto et al20 observed significant improvement in RAVLT performance after carotid interventions, and Lal et al4 reported an overall improvement in cognitive performance, but no significant differences between the CAS and CEA groups, whereas others suggest no cognitive change21,22 or decline in cognition.23,24 We have also assessed multiple cognitive domains, but we chose to focus on RAVLT as our primary cognitive measure because it has been identified to be sensitive in detecting changes after carotid interventions.25 Moreover, word-learning tests have been shown to be both sensitive and specific in distinguishing between normal aging in healthy older adults and MCI, with sensitivity of 90.2% and a specificity of 84.2%.26 To avoid practice effect of cognitive test, we used parallel forms, so each test battery has a different word list. Most studies investigate procedure-related cognitive changes by examining absolute scores or change scores. We believe that percentage of change compared with the baseline more accurately reflects procedure-related changes, and that 10% or more decline reflects meaningful cognitive deterioration. In our assessment, we observed that more than 30% of patients experienced a significant decline at 1 and 6 months after interventions. However, there was an overall improvement (albeit not statistically significant) in RAVLT performance after carotid interventions, suggesting that carotid revascularization procedures benefit cognitive functions overall, but some patients are at risk for cognitive deterioration.

Not surprisingly, we observed that patients older than 80 years of age and those who had a history of tobacco usage experienced more cognitive decline at 6 months in our univariate analysis. We also observed that CEA patients performed better than CAS patients, and that CAS is associated with significant verbal memory decline at 6 months after interventions. This observation supports our previous findings that CAS is associated with more procedure-related microembolization and that microemboli may affect cognition.5 However, CAS is reserved for patients with high surgical and medical comorbidities in our clinical practice, and these patients have lower baseline scores. Although it seems intuitive that patients with lower baseline cognitive scores and high procedure-related embolization would benefit less from carotid revascularization, baseline cognitive score was included in our multivariate model, and percentages of changes were measured to count for the baseline cognitive differences.

Apart from assessing the effects of surgical procedures on cognitive changes, we observed independent associations between cytokines and procedure-related short and long-term cognitive changes. Cytokines are key modulators of inflammatory events, serving as mediators of cellular communication in response to injury and infection.27,28 Recently, Lappegård et al29 observed that reducing the inflammatory burden improved neurocognitive functions in patients with atrial fibrillation. In this study, we show that IL-12p40 is an independent predictor of severe cognitive decline at 1 month, and that TNF-α and SDF-1α are predictors of long-term decline.

Interleukin-12p40 and TNF-α are known to play important roles in cognition. IL-12p40 is a constituent of the active heterodimeric cytokine IL-12, composed of p35 and p40 subunits.30 The IL-12p40 subunit has been shown to serve as macrophage chemoattractant and to prime T-cell activation.31,32 It has also been associated with several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease, autism, and multiple sclerosis.33–35 In addition, inhibition of IL-12p40 signaling decreased cognitive decline33 and improved spatial memory in experimental animals.36 It is important to mention that IL-12p40 has been observed to increase with age in serum of older individuals,37 but our analysis controlled for age and procedure type, still finding a significant association between IL-12p40 and higher risk of cognitive decline at 1 month postop, suggesting that IL-12p40 can serve a risk predictor of early cognitive decline for patients undergoing carotid interventions. TNF-α is known to be involved in release of chemokines and cytokines, recruitment of immune cells, and regulation of apoptosis, healing, and tissue-specific repair mechanisms. Systemic TNF-α was found significantly associated with decrease in cognitive measures in patients with Parkinson disease, correlating increased levels of TNF-α with worse cognitive performance.38 Plasma level of TNF-α was also associated with dementia in older adults39 and with cognitive decline in patients with dementia.40 Moreover, TNF-α has been shown to initiate a proinflammatory cytokine cascade that triggers and maintains postoperative cognitive decline in a in an experimental mouse model.41 These clinical findings and in vivo investigations are consistent with our observation that plasma TNF-α can serve as an independent predictor of long-term decline in cognitive function for patients with carotid interventions.

Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha is recognized as an important mediator of angiogenesis and has also been implied in neurogenesis. Decreased levels of SDF-1α in plasma of patients with early Alzheimer disease has been associated with decreased intracellular communication in the brain, affecting cognition.42 SDF-1α has also been shown to improve functional recovery and behavioral restoration in mice after ischemic brain damage,43 and to improve cognition in epileptic rats,44 suggesting that SDF-1α has protective effects. On the other hand, IL-6 is involved in immunomodulatory functional properties,45 and it has been associated with cognitive decline in the high-functional older individuals.9,46 Unlike these observations, our results showed that systemic SDF-1α level was an independent predictor of cognitive decline, whereas IL-6 offered cognitive protective effects long-term after carotid interventions. It is unclear why our results are contradictory to the literature, but the role of these cytokines in predicting cognitive changes in patients with severe carotid disease who undergo carotid interventions had not been previously studied. It is possible that patients with severe cardiovascular disease exert a different profile than relatively healthy individuals. Our findings will need to be validated in a larger patient cohort with similar conditions. It is worth noting that cytokines can change quickly with inflammatory conditions; therefore, serial cytokine measures may be more accurate and add more insightful information on disease processes.

Our study proposes that cytokines can be an innovative, cost-effective approach to detect evolving cognitive impairment after carotid revascularization. These cytokines obviate the need to train specialized personnel to conduct these neurocognitive performance tests, which usually take several hours to complete. Furthermore, cytokines can be used to identify patients with cognitive decline who may benefit from early intervention to prevent or postpone cognitive deterioration. Early cognitive training has been shown to prevent progression of dementia in patients with Alzheimer disease.47,48 Cognitive training in older adults with mild or early cognitive impairment has been shown to be effective in improving general cognitive function, memory, executive function, and everyday problem-solving ability.49 In the same vein, several pharmacological cognitive enhancers have been suggested to be useful in improving cognition patients in patients with cognitive impairment. However, long-term efficacy remains to be determined.50

Our study has several limitations. First, the patients were not randomized, but assigned to interventional procedures based on clinical criteria; therefore, our findings on CAS-related changes may be biased. Although this is the largest cytokine study in patients with severe carotid disease who undergo carotid interventions, our patient population is relatively small. A large patient cohort with similar disease-specific conditions is warranted to verify our findings and to identify general neurocognitive variation. Given that our cohort is composed of older patients with severe carotid occlusive disease who are at the highest risk for natural cognitive deterioration, we chose to examine cognitive function at 6 months to identify procedure-related long-term changes. However, it is possible that long-term effects in cognition were not yet present at 6 months, and longer follow-up may be needed. Although RAVLT is shown a reliable and sensitive measure for patients with severe carotid disease, other specific neurocognitive dimensions (memory, linguistic ability, concentration, and psychomotor executive skills) could further specify the extent of cognitive impairment. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides compelling evidence that examination of biomarkers after surgical intervention can serve as predictors of cognitive decline, and these could guide physicians in planning care for patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that carotid interventions affect cognitive function. More importantly, we have identified systemic biomarkers that can be used to detect patients at risk of significant cognitive decline after procedures. Particularly, TNF-α and SDF-1α represent promising predictors of cognitive impairment and IL-12p40 of patients at risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (grant number I01BX001398) and the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01NS070308).

Footnotes

Presented at: American Surgical Association, Chicago, 2016.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott A. Dementia: a problem for our age. Nature. 2011;475:S2–S4. doi: 10.1038/475S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milisen K, Abraham IL, Broos PL. Postoperative variation in neurocognitive and functional status in elderly hip fracture patients. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:59–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocco J, Wilson DA, Komotar RJ, et al. Predictors of neurocognitive decline after carotid endarterectomy. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:844–850. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000209638.62401.7E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lal BK, Younes M, Cruz G, et al. Cognitive changes after surgery vs stenting for carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W, Hitchner E, Gillis K, et al. Prospective neurocognitive evaluation of patients undergoing carotid interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggio P, Altamura C, Landi D, et al. Diffusion-weighted lesions after carotid artery stenting are associated with cognitive impairment. J Neurol Sci. 2013;328:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fierstra J, Maclean DB, Fisher JA, et al. Surgical revascularization reverses cerebral cortical thinning in patients with severe cerebrovascular steno-occlusive disease. Stroke. 2011;42:1631–1637. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley AP, Forman DE, Poppas A, et al. Carotid artery intima-media thickness and cognition in cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2007;121:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx BW, et al. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and White elders. Neurology. 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gimeno D, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Inflammatory markers and cognitive function in middle-aged adults: The Whitehall II Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1322–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerreiro RJ, Santana I, Bras JM, et al. Peripheral inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:406–412. doi: 10.1159/000107700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reale M, Iarlori C, Thomas A, et al. Peripheral cytokines profile in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvin B, Neville LF, Barone FC, et al. The role of inflammation and cytokines in brain injury. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:445–452. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan N, Banks WA. Brain-immune communication pathways. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudetz JA, Gandhi SD, Iqbal Z, et al. Elevated postoperative inflammatory biomarkers are associated with short-and medium-term cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery surgery. J Anesth. 2011;25:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-010-1042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazmierski J, Banys A, Latek J, et al. Raised IL-2 and TNF-α concentrations are associated with postoperative delirium in patients undergoing coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:845–855. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213002378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murkin JM, Newman SP, Stump DA, et al. Statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1289–1295. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00106-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC, et al. National institute of neurological disorders and stroke-Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke. 2006;37:2220–2241. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000237236.88823.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picchetto L, Spalletta G, Casolla B, et al. Cognitive performance following carotid endarterectomy or stenting in asymptomatic patients with severe ICA stenosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;2013:342571. doi: 10.1155/2013/342571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehrner J, Willfort A, Mlekusch I, et al. Neuropsychological outcome 6 months after unilateral carotid stenting. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:859–866. doi: 10.1080/13803390490919083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aleksic M, Huff W, Hoppmann B, et al. Cognitive function remains unchanged after endarterectomy of unilateral internal carotid artery stenosis under local anaesthesia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bo M, Massaia M, Speme S, et al. Risk of cognitive decline in older patients after carotid endarterectomy: an observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:932–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gossetti B, Gattuso R, Irace L, et al. Embolism to the brain during carotid stenting and surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2007;107:151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu G, Liu X, Meyer JS, et al. Cognitive performance after carotid angioplasty and stenting with brain protection devices. Neurol Res. 2007;29:251–255. doi: 10.1179/016164107X159216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin LA, Paré N, Saykin AJ, et al. Differential memory test sensitivity for diagnosing amnestic mild cognitive impairment and predicting conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Neuropsychol C. 2009;16:357–376. doi: 10.1080/13825580902825220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanley AC, Lacy P. Pathways for cytokine secretion. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:218–229. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00017.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramesh G, MacLean AG, Philipp MT. Cytokines and chemokines at the crossroads of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:480739. doi: 10.1155/2013/480739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lappegård KT, Pop-Purceleanu M, van Heerde W, et al. Improved neurocognitive functions correlate with reduced inflammatory burden in atrial fibrillation patients treated with intensive cholesterol lowering therapy. Dementia. 2013;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bette M, Jin S, Germann T, et al. Differential expression of mRNA encoding interleukin-12 p35 and p40 subunits in situ. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2435–2440. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ha SJ, Lee CH, Lee SB, et al. A novel function of IL-12p40 as a chemotactic molecule for macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;163:2902–2908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khader SA, Partida-Sanchez S, Bell G, et al. Interleukin 12p40 is required for dendritic cell migration and T cell priming after mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1805–1815. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.vom Berg J, Prokop S, Miller KR, et al. Inhibition of IL-12/IL-23 signaling reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline. Nat Med. 2012;18:1812–1819. doi: 10.1038/nm.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komori M, Blake A, Greenwood M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers reveal intrathecal inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:3–20. doi: 10.1002/ana.24408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan M, Yu J, Jiang T, et al. IL12/23 p40 inhibition ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease-associated neuropathology and spatial memory in SAMP8 mice. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014;38:633–646. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rea I, McNerlan S, Alexander H. Total serum IL-12 and IL-12p40, but not IL-12p70, are increased in the serum of older subjects; relationship to CD3 and NK subsets. Cytokine. 2000;12:156–159. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menza M, Dobkin RD, Marin H, et al. The role of inflammatory cytokines in cognition and other non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:474–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.51.6.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruunsgaard H, Andersen-Ranberg K, Jeune B, et al. A high plasma concentration of TNF-( is associated with dementia in centenarians. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M357–M364. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAfoose J, Baune B. Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terrando N, Monaco C, Ma D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha triggers a cytokine cascade yielding postoperative cognitive decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20518–20522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014557107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laske C, Stellos K, Eschweiler GW, et al. Decreased CXCL12 (SDF-1) plasma levels in early Alzheimer’s disease: a contribution to a deficient hematopoietic brain support? J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008;15:83–95. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Q, Zhou L, Liu L, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha alleviates hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Liu T, Zhou Z, et al. Enriched environment altered aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis and improved long-term consequences after temporal lobe epilepsy in adult rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;56:409–421. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weaver JD, Huang MH, Albert M, et al. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology. 2002;59:371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gates NJ, Sachdev P. Is cognitive training an effective treatment for preclinical and early Alzheimer’s disease? J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014;42 doi: 10.3233/JAD-141302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanaan SF, McDowd JM, Colgrove Y, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of intensive cognitive training in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29:150–158. doi: 10.1177/1533317513506775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Law LL, Barnett F, Yau MK, et al. Effects of combined cognitive and exercise interventions on cognition in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Berliner S, et al. Efficacy and safety of cognitive enhancers for patients with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185:1393–1401. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]