Abstract

Objective

Examine the mediating role of diet in the relationship between volume and duration of sedentary time with cardiometabolic health in adolescents.

Methods

Adolescents (12‐19 years) participating in the 2003/04 and 2005/06 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were examined. Cardiometabolic health indicators were body mass index z‐scores (zBMI) (n = 1,797) and metabolic syndrome (MetS) (n = 812). An ActiGraph hip‐worn accelerometer was used to derive total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout duration. Dietary intake was assessed using two 24‐hour dietary recalls. Mediation analyses were conducted to examine five dietary mediators [total energy intake, discretionary foods, sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSB), fruits and vegetables, and dietary quality] of the relationship between total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout duration with zBMI and MetS.

Results

Total sedentary time was inversely associated with zBMI (β = −1.33; 95% CI −2.53 to −0.13) but attenuated after adjusting for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity. No significant associations were observed between usual sedentary bout duration with zBMI or either sedentary measure with MetS. None of the five dietary variables mediated any of the relationships examined.

Conclusions

Further studies are needed to explore associations of specific time periods (e.g., after school) and bout durations with both cardiometabolic health indicators and dietary behaviors.

Introduction

Adolescents with obesity and the metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a major public health concern in many Western countries 1. Over 20% of U.S. adolescents aged 12 to 19 years have obesity 2, and approximately 9.8% meet the criteria for MetS 3. Similar statistics have been reported in other Western countries such as Australia, Canada, and the UK 4. Since obesity tracks into adulthood 5, and adolescents who have MetS are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease during adulthood 6, it is important to understand their lifestyle risk factors to help inform effective interventions.

Sedentary behavior, defined as any waking behaviors characterized by low energy expenditure (<1.5 metabolic equivalents) while in a sitting or reclining posture 7, has emerged as a health risk in the pediatric population. Evidence in adolescents suggests time spent engaged in certain sedentary behaviors, such as television viewing, is associated with overweight and obesity 8 and an increased risk of developing MetS 9. However, the few studies in adolescents examining accelerometry‐measured total sedentary time with indicators of cardiometabolic health have reported mixed findings 10, 11, 12. In addition, evidence on the accumulation of sedentary time, for example, long “bouts” of sitting versus short “bouts” of sitting, also yields mixed findings 12, 13, 14.

These inconsistent findings in adolescents are in contrast to the evidence in the adult literature, both from experimental 15, 16, 17 and epidemiological studies 18, 19, where prolonged, unbroken bouts of sedentary time have been found to be consistently associated with indicators of poor cardiometabolic health. These inconsistent findings pose the question as to whether sitting itself is a risk factor for poor cardiometabolic health in adolescents (e.g., whether sitting reduces skeletal muscle contractile activity and in turn reduces energy expenditure) or whether sitting is a marker of an unhealthy lifestyle. For example, due to the codependent nature of activities within a 24‐hour period, time spent sedentary displaces time spent in more health enhancing activities, such as physical activity and sleep 20. Alternatively, time spent sitting could promote overeating or the consumption of unhealthy foods or beverages. For example, there is consistent evidence to show self‐reported television viewing is associated with several unhealthy dietary behaviors 21; however, it is unclear whether dietary intake is also linked with objectively measured total sedentary time or bouts of sedentary time.

Given that the relationship between sedentary time and cardiometabolic health outcomes in adolescents is unclear, there is a need to better understand whether other factors, such as dietary intake, can help explain the inconsistent findings. One way to explore this is through mediation analyses, which allow the researcher to examine whether an underlying factor (e.g., mediator) may explain the pathway between an independent and dependent variable. Although some studies have explored the mediating pathway of dietary intake in the relationship between self‐reported measures of sedentary behavior and BMI 22, 23, to date no study has explored this relationship using objectively measured sedentary time. Therefore, this study aims to investigate whether five elements of dietary intake mediate the associations between both the volume and bouts of sedentary time with BMI and MetS in U.S. adolescents.

Methods

Study population and design

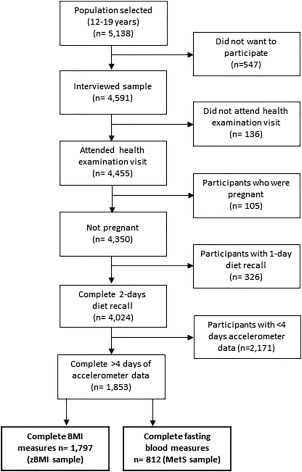

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a United States‐based study that involves a multistage, stratified sampling design used to recruit a representative sample of the U.S. population (of all ages) in 2‐year cycles. Further information about the NHANES study is described elsewhere 24; only data from adolescents (aged 12‐19 years) collected in the 2003 to 2004 and 2005 to 2006 cycles were combined and considered for these analyses. Briefly, participants who were ≥18 years old provided consent and parents/guardians gave consent for minors (ages <18 years). All eligible participants completed a questionnaire on their demographics and activity/sedentary behavior levels at a home interview. Afterward, participants (accompanied by their parent/guardian) were invited to attend a health examination visit to collect physiological measurements and complete one of two 24‐hour dietary recalls. Those who attended the clinic were also asked to wear an activity monitor for 7 days and undertake the second 24‐hour dietary recall 4 to 11 days afterward. Participants who were not pregnant, had complete data on two 24‐hour dietary recalls and anthropometric measurements, had 4 valid days of accelerometry data, and had complete fasting blood samples were included in the analyses (Figure 1). Overall, 35% and 16% of participants from the original cohort had complete data for the BMI sample and MetS sample, respectively.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Measurements

Cardiometabolic measurements

Height, weight, and waist circumference measurements and blood pressure were taken from all participants who attended the health examination visit. Standing height (centimeters) was measured without shoes using a stadiometer and weight (kilograms) was measured in light clothing using digital scales. Height and weight were used to calculate participants' zBMI using age‐ and sex‐BMI percentiles based on the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. growth charts 25. Fasting blood glucose and serum lipids were obtained from a subsample of participants who attended the morning session and had fasted overnight for at least 8.5 hours. The full protocol and assessment on blood analyses can be found elsewhere 26. The presence of MetS was calculated using the International Diabetes Federation criteria, specifically designed for the pediatric population 27. For these analyses, adolescents were considered to have MetS if they had an elevated waist circumference according to age‐ and sex‐specific percentiles (≥79.5 to ≥102.0 cm) and had two or more of the following four risk factors (cutoff values presented are dependent on age and sex): elevated systolic (≥121 to ≥130 mm Hg) or diastolic blood pressure (≥76 to ≥85 mm Hg), low HDL‐cholesterol (≤1.13 to ≤1.3 mmol/L), elevated triglycerides (≥1.44 to ≥1.70 mmol/L), and elevated plasma glucose (≥5.6 mmol/L).

Sedentary time

Sedentary time was measured via an ActiGraph AM‐7164 accelerometer (LLC, Fort Walton Beach, FL), an accurate and reliable tool that quantifies sedentary behavior and moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA) 28. Participants wore the monitor on their right hip during all waking hours for 7 days, except for bathing and swimming. Data were downloaded in 1‐minute epochs. Non‐wear time was defined as at least 20 minutes of zero counts. Daily sedentary time was defined as all wear‐time minutes with an average activity count of ≤100 cpm. Sedentary time was standardized for wear time using the residual method 29. Usual sedentary bout was calculated using the equation by Chastin and Granat 30. Briefly, a sedentary bout was calculated by summing all uninterrupted minutes ≤100 cpm. Taking into account different bout durations, the midpoint of all the sedentary bouts that lie on the sedentary accumulation curve was then calculated for each participant. Analyses were limited to participants who had ≥10 hours of monitor wear time on any ≥4 days, and the monitor was returned in calibration.

Dietary intake

Dietary intake was assessed via two interviewer‐administered 24‐hour dietary recalls, delivered via a computer‐assisted system (the Automated Multi‐Pass Method). Participants aged 12 years and older reported their first dietary recall with an interviewer at the health examination visit and then 4 to 11 days later by telephone. All dietary data were coded using the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference 31. Based on previous literature examining dietary mediators 22, the following dietary variables were examined: 1 total energy intake; 2 consumption of discretionary foods; 3 consumption of sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSB); 4 fruit and vegetable intake; and 5 diet quality.

All dietary variables were calculated based on the average of 2 days of dietary recall. Total energy intake (calories) was calculated for each participant based on the quantity of food and beverages reported, and servings of discretionary foods, SSB, and fruits and vegetables were calculated using the Food Patterns Equivalents Database 32. Discretionary foods were defined as grain‐ and dairy‐based desserts, cereal and granola bars, sweet snacks and candies, sugar‐syrups and preserves, salty snacks from grain or starchy vegetables, and dips/spreads. SSB were defined as any nonalcoholic beverage with added sugar including soda, fruit‐flavored drinks (not 100% juice), sweetened tea, coffee and milk drinks, sport drinks, and energy drinks. Any “diet” drinks, 100% fruit juice, or unsweetened tea or coffee were not included as a SSB. A serving of discretionary foods and a serving of SSB were equivalent to 143 calories (600 kJ) 33.

Fruit and vegetable intake included any whole fruit (not including fruit juice), and vegetables included potatoes, beans, and legumes. A serving of fruits and vegetables was equivalent to one cup of raw, canned, or frozen fruits or vegetables or two cups of leafy green vegetables. Diet quality was calculated using The Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI‐2010) 34, a scoring system that measures the degree of compliance to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The HEI‐2010 is made up of 12 food‐based components and compliance to each of the 12 components was scored separately and then summed together. Scores ranged from 0 to 100, and higher scores indicated greater compliance to the dietary recommendations.

Covariates

The covariates considered for the analyses were age (in years), sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic position, dietary intake under‐reporting, and objectively measured MVPA. For the nonenergy‐related mediators, total energy intake was also adjusted for in the main analyses. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Mexican American, other Hispanic, non‐Hispanic white, non‐Hispanic black, and other race, including multiracial. Socioeconomic position was calculated by dividing family income with the poverty guidelines specific to family size, year, and state. Dietary intake under‐reporting was assessed on the basis of the ratio of total energy intake with estimated energy expenditure. Those below the energy intake to energy expenditure ratio of 2 standard deviations or more were classified as under‐reporters 35. MVPA was calculated according to the Freedson accelerometer age‐cut points for adolescents 36.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA/SE™ 14.0 software (StataCorp LP) using survey commands. To obtain population‐representative findings, regression estimates with weightings were applied to the descriptive statistics and to all mediation analyses. As recommended in the NHANES Analytic Guidelines, 2‐year sample weights for each NHANES cycle (2003 to 2004 and 2005 to 2006) were combined to provide 4‐year sample weights. Given >10% of participants had missing data (mostly due to accelerometer noncompliance), the sample weights were recalculated using age, sex, and race/ethnicity. The day 2 dietary sample weights were used for the main analyses involving zBMI and the fasting subsample weights were used for the analyses involving MetS. The significance level was set at P < 0.05 for all statistical tests.

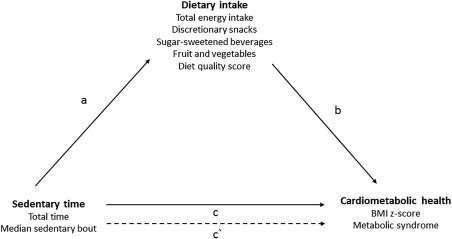

Prior to the main analyses, total energy intake, servings of discretionary foods, SSB, and fruits and vegetables, and usual sedentary bout were not normally distributed so were log transformed. Using the product of coefficients method by MacKinnon et al. 37, regression analyses were used to test whether each dietary variable mediated the association between sedentary time (total and usual bout) with zBMI and MetS (Figure 2). Based on recent evidence on the compositional paradigm for codependent data 20, the first analyses (Model 1) adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and dietary intake under‐reporters, and the second analyses (Model 2) additionally adjusted for MVPA (Model 2). For both models, the nonenergy‐related additionally adjusted for total energy intake in the main analyses.

Figure 2.

Theoretical diagram of the mediation pathways between sedentary time, dietary intake, and cardiometabolic health.

As shown in Figure 2, for each mediation model, the following associations were tested: 1 associations of sedentary time (total and usual bout) with each of the five dietary mediators (a‐coefficient pathway); 2 associations of the five dietary mediators with zBMI or MetS, adjusting for either total sedentary time or usual sedentary bout (b‐coefficient pathway); 3 associations of sedentary time (total and usual bout) with zBMI or MetS (c‐coefficient pathway); and 4 the direct association of sedentary time (total and usual bout) with zBMI or MetS, accounting for each of the dietary mediators (c′‐coefficient pathway). The mediating effect of the dietary variables was calculated by multiplying the a‐ and b‐coefficients (a × b) 37. As MetS is a dichotomous outcome, the coefficients were used to calculate the mediating pathways; however, the odds ratios(OR) are presented in the tables for descriptive purposes.

Results

The baseline characteristics of those adolescents with complete zBMI profiles (n = 1,797) and complete data for identifying MetS (n = 812) are presented in Table 1. Compared with those excluded in the analyses (n = 2,643), participants included in the current analyses (n = 1,797) were significantly younger, included more Mexican American participants and fewer non‐Hispanic white participants, and had a higher socioeconomic position, lower BMI, lower usual sedentary bout duration, higher fruit and vegetable intake and HEI score, a higher consumption of discretionary foods, and a lower consumption of SSB (Supporting Information Table S1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, blood profiles, sedentary/activity time, and dietary intake in U.S. adolescents participating in NHANES, 2003‐2006

| Variable | zBMI (n = 1,797) | MetS (n = 812) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean (%)a | 95% CI | |

| Age (y) | 15.1 | 14.9‐15.3 | 15.1 | 14.9‐15.4 |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Boys | 51.1 | 47.7‐54.5 | 50.1 | 46.0‐55.7 |

| Girls | 48.9 | 45.5‐52.3 | 49.1 | 44.3‐54.0 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Mexican American | 34.4 | 32.2‐36.6 | 35.2 | 32.0‐38.6 |

| Other Hispanic | 3.2 | 2.5‐4.1 | 3.1 | 2.1‐4.5 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 23.8 | 21.9‐25.8 | 21.7 | 19.0‐24.6 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 34.4 | 32.3‐36.7 | 35.5 | 32.2‐38.8 |

| Other race | 4.2 | 3.3‐5.2 | 4.6 | 3.3‐6.2 |

| Socioeconomic position | 2.7 | 2.5‐2.9 | 2.7 | 2.4‐2.9 |

| BMI | ||||

| kg/m2 | 22.8 | 22.3‐23.3 | 22.8 | 22.1‐23.3 |

| z‐score | 0.5 | 0.4‐0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3‐0.6 |

| Overweight (%) | 23.5 | 18.9‐28.8 | 20.3 | 16.2‐25.2 |

| Obesity (%) | 12.1 | 9.4‐15.4 | 13.9 | 10.5‐18.2 |

| Cardiometabolic components | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 79.2 (34.1) | 77.7‐80.7 | ||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 108.5 (4.8) | 107.2‐109.7 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 60.6 (1.1) | 59.4‐61.8 | ||

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 5.1 (9.6) | 5.0‐5.2 | ||

| HDL‐cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.4 (22.2) | 1.3‐1.4 | ||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.9 (11.4) | 0.9‐1.0 | ||

| MetS (%) | 6.7 | 4.2‐10.5 | ||

| Sedentary time | ||||

| Total (h) | 6.9 | 6.8‐6.9 | 7.1 | 7.0‐7.2 |

| Usual bout (min) | 8.8 | 8.4‐9.1 | 9.3 | 8.9‐9.8 |

| MVPA (min) | 26.1 | 23.4‐28.8 | 26.3 | 22.7‐29.8 |

| Diet | ||||

| Total energy intake (kcal) | 2,224 | 2150‐2298 | 2241.4 | 2180‐2301 |

| Discretionary foods (servings) | 2.6 | 2.4‐2.9 | 2.7 | 2.4‐2.9 |

| SSB (servings) | 2.0 | 1.8‐2.1 | 1.9 | 1.8‐2.1 |

| Fruits/vegetables (servings) | 1.8 | 1.7‐1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7‐2.0 |

| Diet quality score (HEI‐2010) | 41.8 | 40.4‐43.2 | 41.5 | 40.1‐42.9 |

% of those meeting the individual components of MetS in parentheses. Values weighted to account for survey design. Mean and 95% CI.

BP, blood pressure; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HEI‐2010, Healthy Eating Index2010; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MVPA, moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; SSB, sugar‐sweetened beverages.

Sedentary time and dietary intake

In the zBMI sample, total sedentary time was positively associated with SSB consumption (β = 0.67; 95% CI 0.01 to 1.33) after adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, dietary intake under‐reporting, and MVPA, with no other significant associations observed for usual sedentary bout with any of the dietary variables (Table 2). In the MetS sample, no associations were observed for total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout with any of the dietary variables (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Associations between sedentary time (total and usual sedentary bout) with zBMI, accounting for mediation by dietary variables (n = 1,797)

| Outcome: zBMI | a‐Coefficient β (95% CI) | b‐Coefficient β (95% CI) | ć‐Coefficient β (95% CI) | ab (mediated) β (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Total sedentary time (h) | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) a | 7.05 (−2.94 to 17.05) | 5.88 (−3.63 to 15.39) | −0.17 (−0.30 to −0.03)b | −0.16 (−0.29 to −0.03b) | −1.21 (−2.40 to −0.03)b | −1.02 (−2.24 to 0.19) | −1.16 (−3.00 to 0.67) | −0.94 (−2.57 to 0.70) |

| Discretionary foods (servings/d) a | −0.11 (−1.04 to 0.81) | −0.32 (−1.22 to 0.58) | −1.87 (−3.23 to −0.50) | −1.76 (−3.16 to −0.36b) | −1.23 (−2.41 to −0.04)b | −1.08 (−2.30 to 0.15) | 0.21 (−1.46 to 1.89) | 0.56 (−1.02 to 2.14) |

| SSB (servings/d) a | 0.59 (−0.10 to 1.29) | 0.67 (0.01 to 1.33)b | 0.55 (−1.07 to 2.17) | 0.48 (−1.09 to 2.05) | −1.24 (−2.43 to −0.04)b | −1.05 (−2.27 to 0.16) | 0.33 (−0.67 to 1.32) | −0.32 (−0.73 to 1.38) |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/d) a | −0.32 (−0.85 to 0.21) | −0.39 (−0.91 to 0.13) | −0.39 (−2.37 to 1.58) | −0.29 (−2.30 to 1.73) | −1.22 (−2.49 to −0.04)b | −1.03 (−2.25 to 0.18) | 0.13 (−0.52 to 0.77) | 0.11 (−0.65 to 0.87) |

| Diet quality score (HEI‐2010) | −3.47 (−17.32 to 10.39) | −4.93 (−17.95 to 8.09) | −0.05 (−0.53 to 0.85) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.04) | −1.35 (−2.54 to −0.15)b | −1.14 (−2.35 to 0.07) | 0.16 (−0.53 to 0.85) | 0.22 (−0.47 to 0.90) |

| Usual sedentary bout (min) a | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) a | 1.05 (−9.68 to 11.78) | 2.06 (−8.71 to 12.83) | −0.17 (−0.31 to −0.04)b | −0.16 (−0.30 to −0.03)b | −1.12 (−2.42 to 0.18) | −1.30 (−2.65 to 0.06) | −0.18 (−1.97 to 1.60) | −0.34 (−2.05 to 1.37) |

| Discretionary foods (servings/d) a | 0.38 (−0.64 to 1.40) | 0.53 (−0.58 to 1.63) | −1.82 (−3.21 to −0.44)b | −1.68 (−3.11 to −0.26)b | −1.06 (−2.37 to 0.24) | −1.22 (−2.57 to 0.13) | −0.69 (−2.55 to 1.16) | −0.88 (−2.81 to 1.04) |

| SSB (servings/d) a | −0.53 (−1.30 to 0.24) | −0.58 (−1.37 to 0.22) | 0.37 (−1.25 to 2.00) | 0.30 (−1.28 to 1.89) | −1.11 (−2.43 to 0.21) | −1.29 (−2.66 to 0.08) | −0.20 (−1.07 to 0.68) | −0.17 (−1.08 to 0.73) |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/d) a | −0.47 (−1.21 to 0.28) | −0.44 (−1.16 to 0.29) | −0.35 (−2.38 to 1.67) | −2.26 (−2.30 to 1.79) | −1.15 (−2.46 to 0.16) | −1.32 (−2.67 to 0.03) | 0.17 (−0.78 to 1.11) | 0.11 (−0.76 to 0.98) |

| Diet quality score (HEI‐2010) | 8.84 (−13.92 to 31.61) | 9.86 (−12.46 to 32.18) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05) | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.05) | −1.10 (−2.41 to 0.21) | −1.29 (−2.65 to 0.07) | −0.38 (−1.59 to 0.82) | −0.39 (−1.56 to 0.78) |

Model 1: Total effects (c‐pathway) of total sedentary time β = −1.33 (95% CI −2.53 to −0.13)b and usual sedentary bout β = −1.14 (95% CI −2.44 to 0.17) with zBMI. Analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and dietary intake under‐reporting. Model 2: Total effects (c‐pathway) of total sedentary time β = −1.12 (95% CI −2.33 to 0.09) and usual sedentary bout β = −1.33 (95% CI −2.68 to 0.02) with zBMI. Analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, dietary intake under‐reporting, and moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity. For both models, the nonenergy‐related mediators additionally adjusted for total energy intake in the main analyses. Due to the small units of measure, all results (except for the ab/c% column) have been multiplied by 10.

Log transformed.

Significance is noted by P < 0.05.

HEI‐2010, Healthy Eating Index 2010; SSB, sugar‐sweetened beverages.

Table 3.

Associations between sedentary time (total and usual sedentary bout) with MetS, accounting for mediation by dietary variables (n = 812)

| Outcome: MetS | a‐Coefficient β (95% CI) | b‐Coefficient OR (95% CI) | ć‐Coefficient OR (95% CI) | ab (mediated) β (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Total sedentary time (h) | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) a | 9.18 (−6.12 to 24.48) | 7.92 (−7.99 to 23.82) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95)b | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95)b | 0.73 (0.20 to 2.65) | 0.66 (0.21 to 2.04) | −12.01 (32.50 to 8.49) | −10.37 (−31.30 to 10.57) |

| Discretionary foods (servings/d) a | −1.07 (−2.42 to 0.28) | −1.16 (−2.59 to 0.27) | 0.85 (0.38 to 1.88) | 0.82 (0.37 to 1.81) | 0.71 (0.20 to 2.50) | 0.64 (0.21 to 1.87) | 1.75 (−6.67 to 10.17) | 2.29 (−6.93 to 11.51) |

| SSB (servings/d) a | 0.15 (−0.85 to 1.52) | 0.20 (−0.95 to 1.35) | 1.05 (0.55 to 2.02) | 0.10 (0.55 to 2.20) | 0.73 (0.20 to 2.63) | 0.66 (0.22 to 2.00) | 0.08 (−1.03 to 1.19) | 0.20 (−1.52 to 1.91) |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/d) a | −0.20 (−0.84 to 0.43) | −0.19 (−0.91 to 0.05) | 0.71 (0.20 to 2.60) | 0.70 (0.19 to 2.52) | 0.72 (0.20 to 2.61) | 0.65 (0.21 to 2.00) | 0.69 (−2.56 to 3.94) | 0.69 (−2.74 to 4.11) |

| Diet quality score (HEI‐2010) | −7.61 (−30.41 to 15.19) | −8.20 (−31.77 to 15.37) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.69 (0.21 to 2.26) | 0.64 (0.22 to 1.83) | −0.42 (−3.42 to 2.59) | −0.48 (−3.69 to 2.73) |

| Usual sedentary bout (min) a | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) a | −5.55 (−21.43 to 10.33) | −5.10 (−20.63 to 10.43) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95)b | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95)b | 1.78 (0.75 to 4.21) | 1.89 (0.74 to 4.81) | 7.34 (−13.26 to 27.94) | 6.70 (−13.31 to 26.72) |

| Discretionary foods (servings/d) a | 0.68 (−0.22 to 1.59) | 0.70 (−0.22 to 1.63) | 0.85 (0.39 to 1.85) | 0.83 (0.38 to 1.80) | 1.81 (0.77 to 4.27) | 1.94 (0.76 to 4.92) | −1.13 (−6.44 to 4.18) | −1.35 (−6.85 to 4.16) |

| SSB (servings/d) a | −0.93 (−2.07 to 0.20) | −0.95 (−2.09 to 0.19) | 1.18 (0.65 to 2.16) | 1.23 (0.69 to 2.20) | 1.83 (0.77 to 4.33) | 1.94 (0.76 to 4.92) | −1.57 (−7.26 to 4.12) | −1.96 (7.72 to 3.80) |

| Fruits and vegetables (servings/d) a | −0.30 (−1.26 to 0.66) | −0.31 (−1.24 to 0.62) | 0.79 (0.26 to 2.69) | 0.80 (0.24 to 2.68) | 1.76 (0.76 to 4.10) | 1.88 (0.75 to 4.70) | 0.70 (−3.62 to 5.02) | 0.71 (−3.44 to 4.85) |

| Diet quality score (HEI‐2010) | 16.29 (−11.42 to 44.00) | 16.45 (−11.60 to 44.50) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.77 (0.72 to 4.35) | 1.91 (0.72 to 5.07) | 0.51 (−4.81 to 5.82) | 0.50 (−4.65 to 5.65) |

Model 1: Total effects (c‐pathway) of total sedentary time OR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.84) and usual sedentary bout OR = 1.92 (95% CI 0.71 to 5.16) with MetS. Analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and dietary intake under‐reporting. Model 2: Total effects (c‐pathway) of total sedentary time OR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.84) and usual sedentary bout OR = 1.92 (95% CI 0.71 to 5.16) with MetS. Analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, dietary intake under‐reporting, and moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity. For both models, the nonenergy‐related mediators additionally adjusted for total energy intake in the main analyses. Due to the small units of measure, the a‐coefficient and ab‐coefficient have been multiplied by 10.

Log transformed.

Significance is noted by P < 0.05.

HEI‐2010, Healthy Eating Index 2010; SSB, sugar‐sweetened beverages.

Dietary intake, zBMI, and MetS

In the zBMI sample, total energy intake was inversely associated with zBMI (β = −0.17; 95% CI −0.30 to −0.03) after separately taking into account total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout and remained significant after adjusting for MVPA (β = −0.16; 95% CI −0.29 to −0.03). Consumption of discretionary foods was also inversely associated with zBMI after adjusting for MVPA only (β = −1.76; 95% CI −3.16 to −0.36) (Table 2). In the MetS sample, a higher total energy intake was significantly associated with a reduction in the risk of having MetS by 12%, after separately accounting for total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout duration. The findings remained significant after adjusting for MVPA (Table 3).

Sedentary time, zBMI, and MetS

After adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and dietary intake under‐reporting, the total effect (e.g., c‐coefficient) between total sedentary time and zBMI was β = −1.33 (CI −2.53 to −0.13), implying that for every hour spent sitting, zBMI decreased by 1.33 units (Table 2). However, after additionally adjusting for MVPA, no significant association remained. When examining the total effect between sedentary time and MetS, total sedentary time or usual sedentary bout was not significantly associated with having MetS, even without accounting for MVPA (Table 3).

When examining the direct effect (c'‐coefficient) of sedentary time with zBMI, an inverse relationship was observed between total sedentary time and zBMI when accounting for each of the dietary variables (Table 2). However, after adjusting for MVPA, no significant associations remained. When examining usual sedentary bout with zBMI, there were no significant associations when accounting for each of the dietary variables and MVPA (P > 0.05). In the MetS sample, no direct effect was observed between sedentary time or usual sedentary bout with MetS after separately accounting for all of the dietary variables (Table 3). When examining the indirect effect (e.g., mediation), none of the five dietary variables examined was found to have a significant mediation effect on the associations between sedentary time (total or bout duration) with zBMI or MetS (P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study examined the mediating effects of five dietary variables in the relationship between total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout with zBMI and MetS. Overall, total sedentary time was inversely associated with zBMI; however, the association was no longer significant after adjusting for MVPA. No significant associations were observed between usual sedentary bout and zBMI or between total sedentary time and usual sedentary bout with MetS. Although some of the dietary variables were independently related to total sedentary time, zBMI, and MetS, none of the dietary variables was a significant mediator.

The counterintuitive finding between sedentary time and zBMI when not accounting for MVPA is in contrast to other cross‐sectional studies in adolescents that found positive associations between objectively measured sedentary time with insulin resistance 12, fasting glucose, triglycerides, blood pressure, and a cardiovascular risk score 9. However, it is important to note, these two studies did not adjust for MVPA in the analyses. When this study adjusted for MVPA, the results between total sedentary time and zBMI attenuated. This has also been observed in other studies that examined the unadjusted and adjusted results of MVPA in the analyses and found the significant associations between objectively measured sedentary time and cardiometabolic components also attenuated 10, 14. On the other hand, high levels of MVPA (i.e., approximately 60‐75 min/d) have recently been shown to eliminate the increased risk of all‐cause mortality associated with high amounts of sedentary time 38. To build upon the current evidence to date 20, further research should utilize an integrated paradigm to understand the collective health implications of sedentary behavior and MVPA on pediatric obesity and MetS, rather than examining the effects in isolation.

In this study, total sedentary time was only positively associated with SSB consumption and not with any other dietary variables. The study found for every hour spent sedentary, SSB intake increased by 0.67 servings. Although this association is small, this is equivalent to consuming 14 extra calories each day which in turn can increase weight by 0.6 kg within 1 year 39. The lack of association between total sedentary time and the other dietary elements is in contrast to the literature examining television viewing, where time spent watching TV has consistently been shown to be related to unhealthy dietary elements, such as a higher intake of energy‐dense snacks, fast food, and total energy intake in youth 21. The stronger links between television viewing and unhealthy dietary habits are thought to be due to advertising where foods high in fat and sugar are frequently advertised on children's television programs 40. Thus, it appears that specific sedentary behaviors like television viewing have stronger links with dietary intake as opposed to the total time spent being sedentary or accumulating bouts of sedentary time.

When examining the association between dietary intake and cardiometabolic health, this study found an inverse relationship between total energy intake with both zBMI and MetS and between discretionary snacking and zBMI. Although the findings were not in the expected direction, it is possible that participants with a larger zBMI or those at risk of having MetS may have already sought professional help and thus started to decrease their energy intake or discretionary snacking.

Although one study in adolescents found diet to partially mediate the relationship between television viewing with zBMI 23, this study found none of the dietary variables significantly mediated the relationship between objectively measured sedentary time and bouts with either zBMI or MetS. This could be simply due to the sedentary time not being matched with the dietary intake. For example, the 2 × 24 hour dietary recalls were performed on different days, not necessarily aligning with when the accelerometers were worn to capture sedentary time. This makes it difficult to assess how much of the sedentary time spent throughout the day is also engaging in an eating occasion. Future studies are needed to examine both sedentary time and eating occasions concurrently, and whether adolescents who engage in high amounts of sedentary time and a high number of eating occasions are at a higher risk of adverse cardiometabolic health than those who engage in the same amount of high sedentary time but have fewer eating occasions.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the objective measures of sedentary time and health outcomes and the use of 2 × 24 hour dietary recalls allowing for investigation of individual dietary behaviors and overall diet quality. This study also adjusted for a variety of well‐known covariates, including dietary intake under‐reporting, which would have reduced the measurement error associated with self‐reporting dietary intake but would not have completely eliminated it. Limitations include the cross‐sectional design of the study which cannot distinguish between cause and effect and the MacKinnon method used for the analyses which does not account for multiple comparisons. Additionally, although the accelerometer provides an objective measure of sedentary time, accelerometers cannot assess contextual factors which make it difficult to assess what the participants were doing while sedentary and whether they were consuming food and beverages. Lastly, only a small percentage of participants were classified as having MetS; thus, this may not have been large enough to see associations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found objectively measured sedentary time was associated with zBMI; however, the association attenuated after accounting for MVPA. The study also found that total sedentary time was not associated with MetS, nor was the usual sedentary bout duration with either zBMI or MetS. Although the study found some associations between dietary intake with the health outcomes, none of the dietary variables was a significant mediatro in the sedentary time, zBMI, and MetS relationship. Given the lack of associations found when examining total sedentary time and bouts of sedentary time, this suggests that intervention programs may have to address certain sedentary behaviors (i.e., television viewing) differently than total sedentary time.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Funding agencies: VC is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Salary Award. SAM is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Research Fellowship (FT100100581). DWD is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Research Fellowship (APP1078360). GNH is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowships (#108029). JS is supported by a NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship (APP1026216). This work was also partially supported by an OIS grant from the Victorian State Government and a NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence grant (APP1057608).

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions: EAF, SAM, DWD, and JS contributed to the design of the study; EAF performed the analyses and drafted the article; EAF, VC, SAM, DWD, GNH, and JS interpreted the data, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published.

References

- 1. Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:62‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988‐1994 through 2013‐2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292‐2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee AM, Gurka MJ, DeBoer MD. Trends in metabolic syndrome severity and lifestyle factors among adolescents. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20153177. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980‐2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008;9:474‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hadjiyannakis S. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2005;10:41‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network . Letter to the Editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:540‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school‐aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wennberg P, Gustafsson PE, Dunstan DW, Wennberg M, Hammarstrom A. Television viewing and low leisure‐time physical activity in adolescence independently predict the metabolic syndrome in mid‐adulthood. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2090‐2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martínez‐Gómez D, Eisenmann JC, Gómez‐Martínez S, Veses A, Marcos A, Veiga OL. Sedentary behavior, adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents. The AFINOS Study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2010;63:277‐285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper A. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA 2012;307:704‐712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carson V, Janssen I. Volume, patterns, and types of sedentary behavior and cardio‐metabolic health in children and adolescents: a cross‐sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saunders TJ, Tremblay MS, Mathieu ME, et al. Associations of sedentary behavior, sedentary bouts and breaks in sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk in children with a family history of obesity. PLoS One 2013;8:e79143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colley R, Garriguet D, Janssen I, et al. The association between accelerometer‐measured patterns of sedentary time and health risk in children and youth: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. BMC Public Health 2013;13:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care 2012;35:976‐983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peddie MC, Bone JL, Rehrer NJ, Skeaff CM, Gray AR, Perry TL. Breaking prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glycemia in healthy, normal‐weight adults: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:358‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dempsey PC, Larsen RN, Sethi P, et al. Benefits for type 2 diabetes of interrupting prolonged sitting with brief bouts of light walking or simple resistance activities. Diabetes Care 2016;39:964‐972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Healy GN, Winkler EA, Brakenridge CL, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Accelerometer‐derived sedentary and physical activity time in overweight/obese adults with type 2 diabetes: cross‐sectional associations with cardiometabolic biomarkers. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carson V, Wong SL, Winkler E, Healy GN, Colley RC, Tremblay MS. Patterns of sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk among Canadian adults. Prev Med 2014;65:23‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chastin SFM, Palarea‐Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, Skelton DA. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio‐metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pearson N, Biddle S. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:178‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carson V, Janssen I. The mediating effects of dietary habits on the relationship between television viewing and body mass index among youth. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:391‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H, Hardy LL, Halse C. The associations between TV viewing, food intake, and BMI. A prospective analysis of data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Appetite 2012;59:945‐948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data 2003‐2004, 2005‐2006. CDC;2009. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm. Updated February 3, 2014. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 25. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000. CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat, Series 11, Number 246. Published May 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Laboratory Procedures, Manual. CDC; 2003.

- 27. Jolliffe CJ, Janssen I. Development of age‐specific adolescent metabolic syndrome criteria that are linked to the Adult Treatment Panel III and International Diabetes Federation criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:891‐898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hills AP, Mokhtar N, Byrne NM. Assessment of physical activity and energy expenditure: an overview of objective measures. Front Nutr 2014;1:5. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:1220S‐1228S; discussion 1229S‐1231S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chastin SF, Granat MH. Methods for objective measure, quantification and analysis of sedentary behaviour and inactivity. Gait Posture 2010;31:82‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. US Department of Agriculture . Composition of Foods: Raw, Processed, Prepared. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26. USDA: Beltsville, MD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Friday JE, Thoerig RC, Moshfegh AJ. Food Patterns Equivalents Database 2005‐06: Methodology and User Guide. Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, USDA: Beltsville, MD; 2014. http://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/fped/FPED_0506.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Health and Medical Research Council . Australian Dietary Guidelines (2013) https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/n55. Published 2013. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- 34. Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI‐2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:569‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang TT, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, McCrory MA. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Res 2005;13:1205‐1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, et al. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:350‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 2007;58:593‐614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ekelund U, Steene‐Johannessen J, Brown WJ, et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta‐analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 2016;388:1302‐1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katan MB, Ludwig DS. EXtra calories cause weight gain—but how much? JAMA 2010;303:65‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003‐2004. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:875‐881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information