Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates have decreased worldwide. Gastric acid inhibition during treatment is important to eradicate these bacteria successfully. A new potassium-competitive acid blocker, vonoprazan (VPZ), has been shown to achieve high eradication rates in a previous randomized controlled trial.

Objective

To determine the efficacy of VPZ for H. pylori eradication.

Methods

A total of 874 patients were enrolled; 431 received esomeprazole (EPZ) and 443 received VPZ. First-line regimens contained clarithromycin (CAM) 200 mg b.i.d., amoxicillin 750 mg b.i.d., and either EPZ 20 mg b.i.d. or VPZ 20 mg b.i.d. for 7 days. Metronidazole 250 mg b.i.d. replaced CAM in the second-line regimens. The eradication of H. pylori was assessed by 13C-urea breath tests 4-8 weeks after each therapy.

Results

The overall first-line eradication rate was 79.9% (341/427) with EPZ vs. 86.3% (377/439) with VPZ (p = 0.019). The second-line eradication rate was 83.3% (45/51) with EPZ vs. 91.1% (41/45) with VPZ (p = 0.900).

Conclusion

VPZ was significantly more effective than EPZ for first-line treatment. However, for second-line treatment, there was no significant difference between EPZ and VPZ.

Key Words: Vonoprazan, Esomeprazole, Helicobacter pylori, Eradication, Gastric acid

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection causes chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer [1]. Therefore, H. pylori eradication is recommended for the prevention of these diseases. The success rate of the standard therapy, which uses a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) with amoxicillin (AMX) and clarithromycin (CAM), has decreased in many parts of the world. This decrease appears to be caused by an increase in the prevalence of CAM-resistant strains of H. pylori. Indeed, a study conducted between 2000 and 2013 in Japan [2] found that the overall resistance rate to CAM was 31.1%. However, eradication failure is caused not only by bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents but also by insufficient acid inhibition during treatment, which degrades and destabilizes the antibiotics in the stomach [3]. Gastric acid inhibition by PPIs is influenced by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 genotype and gastric emptying.

Vonoprazan (VPZ) is a novel oral potassium-competitive acid blocker that is part of a new class of gastric acid-suppressant agents. It has been available since February 2015 in Japan but is presently not yet approved in other countries. It competitively inhibits the binding of potassium ions to H+,K+-ATPase in the final step of acid secretion in gastric parietal cells. It has a potent and long-lasting anti-secretory effect on H+,K+-ATPase, owing to its high accumulation in and slow clearance from gastric tissues [4]. Several reports showed that the acid-inhibitory effects of VPZ were stronger than those of conventional PPIs [5,6]. A phase III randomized trial in Japan revealed that a VPZ regimen was more effective as part of a first- and second-line triple therapy than a lansoprazole (LPZ) regimen (92.6%, VPZ regimen; 75.9%, LPZ regimen) [7]. However, there are only a few reports in the literature about the H. pylori eradication rate of VPZ in a clinical setting. In addition, no comparative studies have been conducted related to esomeprazole (EPZ) and VPZ regimens. EPZ has been available for 5 years in Japan, and is considered to be less affected by CYP2C19 than other PPIs. The aim of this study was to compare the H. pylori eradication rate of EPZ and VPZ regimens.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective, open-label, single-center study design was adopted at Saiseikai Nakatsu Hospital, Osaka, Japan. A total of 874 patients who were diagnosed with H. pylori infection between November 2013 and June 2016 enrolled in the study. Four hundred thirty-one patients received the EPZ regimen from November 2013 to March 2015, while 443 patients received the VPZ regimen from April 2015 to June 2016. Before treatment, demographical and clinical characteristics including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and alcohol consumption were checked. Most patients had also undergone an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before enrolment. All patients in our hospital received an endoscopy before eradication as a screening process against gastric cancer. However, a few patients who were diagnosed at other hospitals did not. We have excluded patients with a history of eradication and gastric operations from this study. The protocol and informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Saiseikai Nakatsu Hospital before the start of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the consolidated Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Assessment of H. pylori Infection and Eradication Therapy

The presence of H. pylori infection was detected by 13C-urea breath tests, serological testing (HM-CAP kit, Enteric Product Inc., Westbury, NY, USA), and the rapid urease test (Helico Check, Otsuka Co., Tokushima, Japan).

First-line eradication regimens consisted of CAM 200 mg b.i.d., AMX 750 mg b.i.d., and either EPZ 20 mg b.i.d. or VPZ 20 mg b.i.d., for 7 days. Patients were instructed to take the triple therapy once in the morning and once in the evening. At least 4-8 weeks after the therapy, the extent of eradication of H. pylori infection was assessed by a 13C-urea breath test. When eradication failed, that is, if the bacteria were still present, the patients underwent second-line eradication treatment. The second-line eradication regimens consisted of metronidazole (MNZ) 250 mg b.i.d., AMX 750 mg b.i.d., and either EPZ 20 mg b.i.d. or VPZ 20 mg b.i.d., for 7 days. At least 4-8 weeks after the second-line therapy, the extent of eradication of H. pylori infection was again assessed by a 13C-urea breath test. Successful eradication of H. pylori was defined as a result when the extent of bacterial presence was less than 2.5%. All patients were interviewed by a doctor to document adverse events (if any) experienced and to determine the drug compliance.

Data Analysis

The cure rate was defined as the number of successfully treated patients divided by the number of treated patients. The cure rate was evaluated in 2 ways: intention-to-treat (ITT), which included all eligible patients enrolled in the study, regardless of compliance; and per-protocol (PP), which excluded patients whose compliance was poor or patients with unavailable data. Demographic characteristics were analyzed by the t test. Comparison of categorized data was analyzed by the χ2 test. All p values were 2-sided, and p < 0.05 was selected to indicate statistical significance. The primary endpoint was comparison of the first-line eradication rate between the EPZ and VPZ regimens in the ITT and PP groups, while the secondary endpoint was comparison of the second-line eradication rate between the 2 regimens in the ITT and PP groups. This study aimed to reveal the differences in the eradication rate with respect to the patient's background.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Patients

Eight hundred and seventy-four subjects were included in the trial (431 patients in the EPZ group; 443 patients in the VPZ group). The baseline characteristics of each group are summarized in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the 2 treatment groups except for smoking history. Both treatment groups achieved >90% drug compliance. The overall first-line eradication rates combining both the VPZ and EPZ regimens were 82.2% (718/874) by ITT analysis and 82.9% (718/866) by PP analysis. In contrast, the combined second-line eradication rates were 86.0% (86/100) by ITT analysis and 90.0% (86/96) by PP analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled into each group

| EPZ (n = 431) | VPZ (n = 443) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 60.5±12.2 | 61.6±12.3 | 0.172 |

| Gender, male/female | 219/238 | 220/189 | 0.085 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9±3.3 | 22.9±3.9 | 0.884 |

| Alcohol (yes/no) | 217/209 | 222/215 | 0.968 |

| Smoking (yes/no) | 57/369 | 84/350 | 0.018 |

BMI, body mass index; EPZ, esomeprazole; VPZ, vonoprazan.

Comparison of Eradication Rate

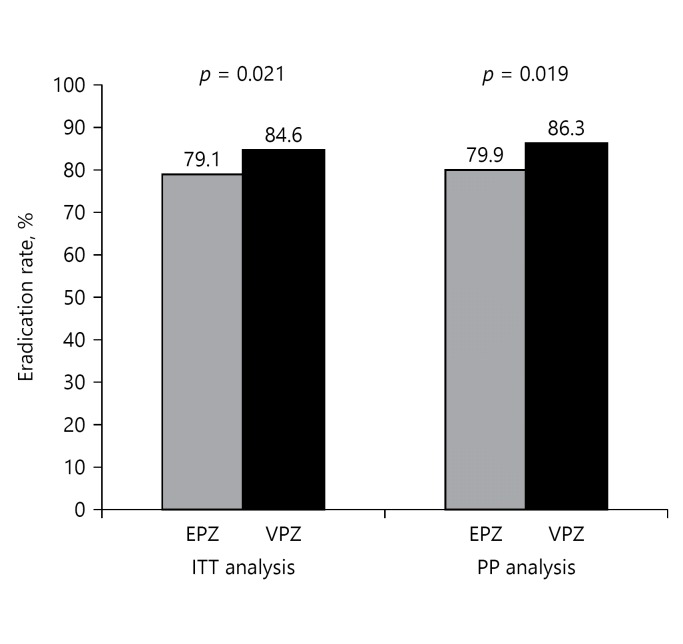

The overall first-line eradication rate was 79.1% (341/431) for the EPZ regimen and 84.6% (377/443) for the VPZ regimen by ITT analysis; the eradication rate by PP analysis for EPZ and VPZ regimens was 79.9% (341/427) and 86.3% (377/439) respectively. The eradication rate for VPZ regimen was significantly higher than that for EPZ regimen in both ITT (p = 0.021) and PP (p = 0.019) analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

H. pylori eradication rates in first-line triple therapy. Both ITT and PP analyses showed that the VPZ regimen was superior to the EPZ regimen. VPZ, vonoprazan; EPZ, esomeprazole; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol.

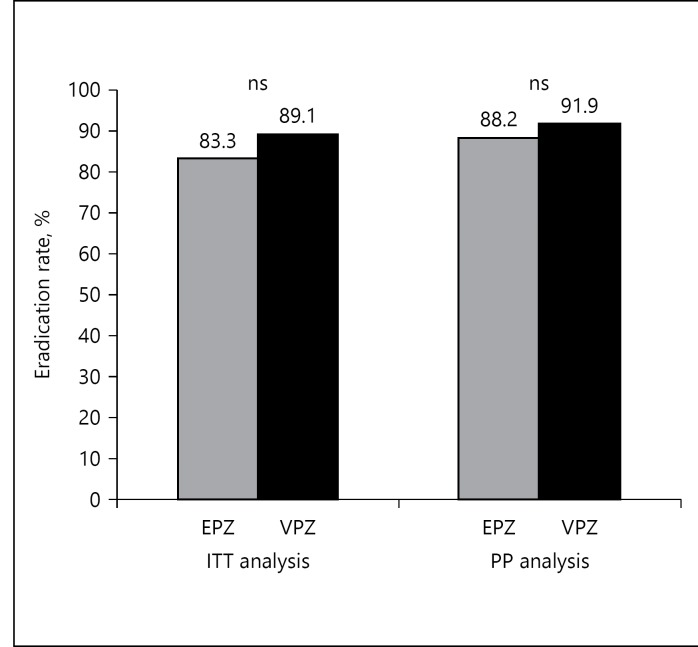

The overall second-line eradication rate was 83.3% (45/54) and 89.1% (41/46) for EPZ and VPZ regimens, respectively, by ITT analysis. In PP analysis, the eradication rate was 88.2% (45/51) for the EPZ regimen and 91.1% (41/45) for the VPZ regimen (Fig. 2). A statistically significant difference in eradication rate was not found between the 2 groups both in ITT (p = 0.587) and PP (p = 0.900) analyses.

Fig. 2.

H. pylori eradication rates in second-line triple therapy. Statistical significance was not found between the VPZ and EPZ regimens. VPZ, vonoprazan; EPZ, esomeprazole; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol; ns, not significant.

In terms of background disease, the eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was significantly higher than that of the EPZ regimen in patients with antral-predominant gastritis. For other background diseases, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups (Table 2). In particular, the eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was higher than that of the EPZ regimen in diseases in which acid secretion persists, such as duodenal ulcers and antral-predominant gastritis.

Table 2.

Comparison of eradication rate background disease

| EPZ |

VPZ |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| eradication rate (n) | eradication rate (n) | ||

| Gastritis (antral-predominant) | 77.5 (134/173) | 86.5 (141/163) | 0.032 |

| Gastritis (pangastilitis) | 81.5 (207/254) | 85.8 (218/254) | 0.187 |

| Gastric ulcer | 88.9 (32/36) | 87.5 (49/56) | 0.898 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 78.9 (15/19) | 93 (40/43) | 0.374 |

| Gastric cancer | 89.5 (17/19) | 75 (21/28) | 0.390 |

EPZ, esomeprazole; VPZ, vonoprazan.

When comparing patient-specific eradication rates between the regimens, a significant difference was seen in patients who were less than 70 years of age, female, or had a BMI <25 (Table 3). The eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was significantly higher than that of the EPZ regimen (age <70: 85.4 vs. 78.5%, p = 0.024; female: 86.4 vs. 76.2%, p = 0.005; BMI <25: 85.5 vs. 79.5%, p = 0.041). There were no significant differences in eradication rates between the 2 groups with respect to other factors.

Table 3.

Comparison of patient-specific eradication rate

| EPZ |

VPZ |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| eradication rate (n) | eradication rate (n) | ||

| Age, years | |||

| >70 | 84.0 (89/106) | 87.1 (108/124) | 0.499 |

| <70 | 78.5 (252/321) | 85.4 (269/315) | 0.024 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 82.8 (197/238) | 85.4 (187/219) | 0.446 |

| Female | 76.2 (144/189) | 86.4 (190/220) | 0.008 |

| BMI | |||

| >25 | 82.0 (73/89) | 86.4 (89/103) | 0.404 |

| <25 | 79.5 (263/331) | 85.5 (283/331) | 0.041 |

| Alcohol | |||

| Yes | 79.6 (176/221) | 85.8 (188/219) | 0.085 |

| No | 80.0 (164/205) | 85.6 (184/215) | 0.129 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 77.2 (44/57) | 88.1 (74/84) | 0.086 |

| No | 80.2 (296/369) | 85.1 (298/350) | 0.081 |

BMI, body mass index; EPZ, esomeprazole; VPZ, vonoprazan.

Adverse Events

Both VPZ and EPZ regimens were well tolerated by the patients. No severe adverse effects were reported; however, some patients experienced less severe adverse effects including diarrhea, bitter taste, nausea, and rash (Table 4). A total of 8 patients deviated from the protocol, out of which 4 (one receiving VPZ, 3 receiving EPZ) did not complete the protocol due to adverse effects.

Table 4.

Breakdown of adverse effects

| EPZ regimen (n = 427) |

VPZ regimen (n = 439) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | |

| Total | 1.17 | 5 | 0.68 | 3 |

| Diarrhea | 0.47 | 2 | 0.23 | 1 |

| Rash | 0.23 | 1 | 0.23 | 1 |

| Nausea | 0.23 | 1 | 0.23 | 1 |

| Bitter taste | 0.23 | 1 | ||

Discussion

This study showed that the first-line H. pylori eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was significantly higher than that of the EPZ regimen in both ITT and PP analyses.

Both CAM and AMX are acid-sensitive; therefore, gastric acid secretions must be strongly inhibited to prevent degradation of the drug during eradication therapy. Sufficient inhibition of gastric acid to generate a stomach pH >5 increases the stability and bioavailability of these acid-sensitive antibiotics [8,9].

Hunt and Scarpignato [10] suggested a reason for the observed superiority of VPZ over conventional PPIs by highlighting the differences between VPZ and conventional PPIs for night-time control of intragastric acidity. Long-lasting acid suppression is important for eradication success. Patients receiving conventional PPIs may experience inadequate acid-inhibition during the night (commonly known as nocturnal acid breakthrough), which may interfere with the stability and bioavailability of acid-sensitive antibiotics and thereby decrease the eradication rate. Sakurai et al. [7] compared the 24 h mean gastric pH on day one between VPZ 20 mg and EPZ 20 mg, and reported that the intragastric pH after VPZ treatment (pH 5.2) was significantly higher than that after EPZ treatment (pH 3.0). Hence, the rapid and sustained acid-inhibitory effect of VPZ might be responsible for its superior eradication rate compared with that of EPZ.

A previous phase III randomized trial in Japan showed a high eradication rate of 92% for the VPZ regimen [7]. The patients enrolled in that study had only gastric or duodenal ulcers. When we analyzed only those patients with a history of ulcers, the rate of H. pylori eradication was 89.9% (89/99), which was similar to that of the aforementioned trial. In addition, Shinozaki et al. [11] evaluated H. pylori eradication rate in patients with gastritis and ulcers and reported that the eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was 85%. Collectively, these data indicate that the eradication rate following VPZ regimen in a clinical setting can be expected to reach 85-90%.

Patients with mild stomach atrophy showed higher eradication rates when using the VPZ regimen. A recent study reported that severe atrophy decreased the success rate of eradication [12]. Hence, it is recommended that H. pylori be eradicated before it causes severe stomach gastritis. A significant difference in eradication rate was seen in patients who were younger than 70 years or who had BMI <25 between the 2 groups in this study. The VPZ regimen had a competitive advantage over the EPZ regimen in these patients. A previous study showed that young, healthy individuals had high mean basal and maximal acid outputs, which correlated negatively with body weight [13]. It is assumed that patients with lower BMI had higher levels of acid secretion. It is conceivable that younger patients also had higher acid secretion levels than older patients because the atrophy of the stomach progressed gradually in H. pylori-positive patients with an increase in age. Therefore, we assumed that this is the reason for the higher eradication rate of the VPZ regimen in these patient groups. Since VPZ has a more potent acid-inhibitory effect than conventional PPIs, the VPZ regimen was superior in these patient groups. Interestingly, Ishimura et al. [14] showed that maximal acid output decreased gradually with age in male patients but remained unchanged in female patients, in healthy Japanese subjects over the past 2 decades. This may be a reason for the higher eradication rate following VPZ regimen in female patients. Furthermore, some studies revealed that women showed lower H. pylori eradication rates when receiving a PPI, MNZ, and AMX triple therapy [15,16]. Hence, the VPZ regimen may be a more effective therapy for resolving these problems.

In this study, there were no significant differences in patient background except for smoking status. Kamada et al. [17] showed that smoking exerted a negative influence on the eradication rate. The group that received the VPZ regimen had a higher number of smokers. Nevertheless, the eradication rate in the VPZ regimen group was higher than that in the EPZ regimen group. This result is probably due to the superiority of the VPZ regimen. Ishioka et al. [18] reported that treatment with CAM 800 mg b.i.d resulted in a higher eradication rate in triple therapy using conventional PPIs. Further study is necessary to conclude whether or not patients with smoking status should also be administered CAM 800 mg b.i.d in a VPZ-based triple therapy.

In contrast to the first-line therapy, there was no difference in the eradication rate following second-line therapy. One reason for this is the low resistance rate to MNZ (2-5%) for H. pylori in Japan [19]. Thus, acid suppression should not be a major problem that affects eradication rate. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance to CAM, MNZ, and levofloxacin appears to be rapidly increasing worldwide [20]. We are currently facing a dilemma between risking an increase in drug tolerance and a decreasing eradication rate. It is important to use antibiotics appropriately but changing to a VPZ-based treatment may offer a solution to this situation.

The strength of this study is that the efficacy of the VPZ regimen for H. pylori eradication was evaluated in a larger cohort than in the previous phase III study. However, the limitations of this study are as follows: the study followed an open-labeled, retrospective, single-center design. We also could not evaluate the effect of CYP2C19 genotype and antibiotic resistance in this study. However, we believe the change in tolerance to antibiotics is relatively small, since this study was performed in the same hospital for a period of 3 years.

The antibiotic doses were lower and the treatment duration shorter in the present study than in the Toronto Consensus [21]. The choice of CAM 200 mg b.i.d. is not consistent with guidelines in Western countries. Moreover, the AMX dose is also less than that typically used in the West. We expected that the total amount of antimicrobial drugs can be reduced because VPZ exerts a powerful acid inhibitory effect. In Japan, the use of CAM 400 mg b.i.d. and AMX 1,000 mg b.i.d. for a treatment duration of 14 days is not widely practiced. One reason for this lies in the Japanese health insurance design. For example, the maximum amount of AMX is limited to 1,500 mg per day for all infectious diseases. Since VPZ strongly inhibits acid secretion, a satisfactory eradication rate was achieved with the minimum amount of antibacterial drugs. A sub-analysis of the previous VPZ randomized controlled trial [7] showed that there was no significant difference in the eradication rate between the CAM 200 and 400 mg b.i.d. regimens when using VPZ. Shortening the treatment period and reducing the amount of antimicrobial agent may result in a decrease in side effects. Furthermore, the compliance rate will improve and medical expenses can be reduced. In our study, the total first-line eradication rate was 82.2% (718/874) for both VPZ and EPZ regimens together, which was a significant result. We did not investigate whether a longer therapy duration and greater amount of antimicrobial agent contributed to higher eradication rates, especially with regard to the VPZ regimen. Further studies are required before adapting Western consensus.

Conclusions

The first-line H. pylori eradication rate of the VPZ regimen was significantly higher than that of the EPZ regimen for all patients, irrespective of their background. VPZ could be a useful alternative to PPIs, in combination with antibiotics for the eradication of H. pylori.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Statement of Ethics

We followed ethical guidelines such as the Helsinki Declaration, ethical guidelines on medical research for people in Japan, and guidelines for the proper handling of personal information in the medical field. We also obtained approval from the ethics committee of our facility.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank medical billing clerks for their help in data collection.

References

- 1.Murakami K, Sakurai Y, Shiino M, Funao N, Nishimura A, Asaka M. Vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, as a component of first-line and second-line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a phase III, randomised, double-blind study. Gut. 2016;65:1439–1446. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamura T, Suga T, Nagaya T, Arakura N, Matsumoto T, Nakayama Y, Tanaka E. Antimicrobial resistance and characteristics of eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori in Japan: a multi-generational comparison. Helicobacter. 2014;19:214–220. doi: 10.1111/hel.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt RH. pH and Hp – gastric acid secretion and Helicobacter pylori: implications for ulcer healing and eradication of the organism. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin JM, Inatomi N, Munson K, Strugatsky D, Tokhtaeva E, Vagin O, Sachs G. Characterization of a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker of the gastric H,K-ATPase, 1-[5-(2-fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]-N-methylmethanamine monofumarate (TAK-438) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:412–420. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagami T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sugimoto M, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Osawa S, Sugimoto K, Miyajima H, Furuta T. Potent acid inhibition by vonoprazan in comparison with esomeprazole, with reference to CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1048–1059. doi: 10.1111/apt.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, Nishimura A, Komura E, Araki T, Shiramoto M. Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects – a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:719–730. doi: 10.1111/apt.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayson ML, Eliopoulos GM, Ferraro MJ, Moellering RC., Jr Effect of varying pH on the susceptibility of Campylobacter pylori to antimicrobial agents. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:888–889. doi: 10.1007/BF01963775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs G, Meyer-Rosberg K, Scott DR, Melchers K. Acid, protons and Helicobacter pylori. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:301–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt RH, Scarpignato C. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs): are they finally ready for prime time in acid-related disease? Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e119. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinozaki S, Nomoto H, Kondo Y, Sakamoto H, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto H, Lefor AK, Osawa H. Comparison of vonoprazan and proton pump inhibitors for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2016;32:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalkan IH, Sapmaz F, Guliter S, Atasoy P. Severe gastritis decreases success rate of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0896-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novis BH, Marks IN, Bank S, Sloan AW. The relation between gastric acid secretion and body habitus, blood groups, smoking, and the subsequent development of dyspepsia and duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1973;14:107–112. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishimura N, Owada Y, Aimi M, Oshima T, Kamada T, Inoue K, Mikami H, Takeuchi T, Miwa H, Higuchi K, Kinoshita Y. No increase in gastric acid secretion in healthy Japanese over the past two decades. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:844–852. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osato MS, Reddy R, Reddy SG, Penland RL, Malaty HM, Graham DY. Pattern of primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1217–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai W, Zhou L, Ren W, Deng L, Yu M. Variables influencing outcome of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in South China. Helicobacter. 2009;14:91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamada T, Haruma K, Komoto K, Mihara M, Chen X, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G, Tahara K, Kawamura Y. Effect of smoking and histological gastritis severity on the rate of H. pylori eradication with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. Helicobacter. 1999;4:204–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.99299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishioka H, Mizuno M, Take S, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Okada H, Yokota K, Oguma K. A better cure rate with 800 mg than with 400 mg clarithromycin regimens in one-week triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in cigarette-smoking peptic ulcer patients. Digestion. 2007;75:63–68. doi: 10.1159/000102301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato M, Yamaoka Y, Kim JJ, Reddy R, Asaka M, Kashima K, Osato MS, El-Zaatari FA, Graham DY, Kwon DH. Regional differences in metronidazole resistance and increasing clarithromycin resistance among Helicobacter pylori isolates from Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2214–2216. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2214-2216.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, Gupta S, Park JY, Crowe SE, Valasek MA. Review article: the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:514–533. doi: 10.1111/apt.13497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, Marshall JK. The Toronto Consensus for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:51–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.006. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]