Abstract

The E2F transcription factors are key regulators of cell cycle progression and the E2F field has made rapid advances since its advent in 1986. Yet, while our understanding of the roles and functions of the E2F family has made enormous progress, with each discovery new questions arise. In this review, we summarise the most recent advances in the field and discuss the remaining key questions. In particular, we will focus on how specificity is achieved among the E2Fs.

Keywords: cancer, cell cycle, E2F, pRB, transcription

The E2F family

The E2F family can be divided into four subgroups based on their potential main function and the mechanism by which this is achieved. E2Fs 1–3, the ‘activating' E2Fs, are required for the transactivation of target genes involved in the G1/S transition and, hence, for correct progression through the cell cycle. Indeed, loss of all three activating E2Fs results in acute cell cycle arrest (Wu et al, 2001). Furthermore, overexpression of E2F1, 2, or 3 in quiescent immortalised rodent fibroblasts is sufficient to drive them into S phase (Johnson et al, 1993; Lukas et al, 1996). Complicating this is the fact that the E2F3 locus encodes for two proteins, E2Fs 3a and 3b, that differ in expression pattern and function; E2F3a is a transcriptional activator mainly expressed during S phase, while E2F3b acts as a transcriptional repressor and is constantly expressed during cell cycle.

In contrast, E2Fs 4 and 5 are considered to possess predominantly repressive activity, because they are mainly nuclear in G0/G1 cells where they are bound to members of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) family (Müller et al, 1997; Verona et al, 1997). Consistent with this, their overexpression in serum-starved fibroblasts does not induce S phase (Lukas et al, 1996). In fact, the major roles of E2Fs 4 and 5 appear to be in the induction of cell cycle exit and differentiation, as opposed to cell cycle progression (Lindeman et al, 1998; Gaubatz et al, 2000; Humbert et al, 2000; Rempel et al, 2000).

E2Fs 6 and 7 are the founding members of the last two subgroups and are also considered to be transcriptional repressors (Morkel et al, 1997; Cartwright et al, 1998; Gaubatz et al, 1998; Trimarchi et al, 1998; de Bruin et al, 2003; Di Stefano et al, 2003). Whereas E2F6 might be the only member of its subgroup, we have recently identified yet another E2F family member (E2F8) belonging to the E2F7 subgroup (Christensen and Helin, unpublished results). The precise roles of these E2Fs are as yet unclear although E2F6 may play a role in quiescence and E2F7 is thought to regulate a subset of E2F target genes throughout the cell cycle (Ogawa et al, 2002; Di Stefano et al, 2003).

Thus, it is clear that, despite high homology (in particular between E2Fs 1 to 5), the E2F family is able to achieve a precisely controlled level of functional specificity. Here, we discuss the ways in which such specificity is achieved.

Genetic evidence for biological specificity

Mutant mouse models provide the clearest examples of biological specificity. Mice lacking E2fs 1–6 have been generated, and studies of both single and compound mutant E2f mice have revealed functional redundancies, such as those between E2Fs 1–3 in proliferation, as well as unique roles, such as the specific role for E2F1 in apoptosis (Table I). For a comprehensive review of the phenotypes of the E2f knockout mice, see DeGregori (2002). Thus, the different E2F family members show overlapping functions in the control of cell cycle progression, but also unique functions during development, tissue homeostasis and tumour formation. However, the mechanisms by which such biological specificity is achieved in tissues is unclear and, to date, the majority of our mechanistic understanding comes from studies of tissue culture cells, as discussed in the following section.

Table 1.

Unique and shared phenotypes of the E2F knockout mice

| Knockout | Phenotype | Specific function | Shared function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2f1−/− | Cancer predisposition. Increased thymic proliferation (due to apoptotic defects) | Apoptosis | Proliferation (with E2f2 and 3) | Yamasaki et al, 1996; Field et al, 1996; Garcia et al, 2000; Zhu et al, 1999 |

| E2f2−/− | Increased proliferation of the haematopoietic cells. Often develop autoimmunity and tumours | Proliferation (with E2f2 and 3) | Murga et al, 2001; Zhu et al, 2001 | |

| E2f3−/− | Partially penetrant embryonic lethality MEFs defective in mitogen-induced activation of E2F-responsive genes | Represses the ARF promoter allowing proliferation | Proliferation (with E2f2 and 3) | Humbert et al, 2000b; Wu et al, 2001; Aslanian et al, 2004; Ziebold et al, 2003 |

| E2f1−/−; E2f2−/−; E2f3−/− | Lethal MEFs fail to proliferate and do not re-enter the cell cycle | ‘Activating' E2Fs are required for proliferation | Wu et al, 2001 | |

| E2f4−/− | Die early from an increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections. No detectable effect on cell cycle arrest or proliferation | Erythroid maturation | Humbert et al, 2000a; Rempel et al, 2000 | |

| E2f5−/− | Develop hydrocephalus after birth (a differentiation not proliferation defect) | Brain development | Lindeman et al, 1998 | |

| E2f4−/−; E2f5−/− | Not reported | Irresponsive to cell cycle arrest imposed by ectopic p16INK4A. Redundant functions in mouse development | Gaubatz et al, 2000 | |

| E2f6−/− | Show mild homeotic transformations of the axial skeleton | Storre et al, 2002 | ||

| DP1−/− | Early embryonic lethality (yet embryonic cells do not show proliferation defects, while trophoblasts do) | Kohn et al, 2003 |

How is biological specificity achieved?

Regulation of E2F activity

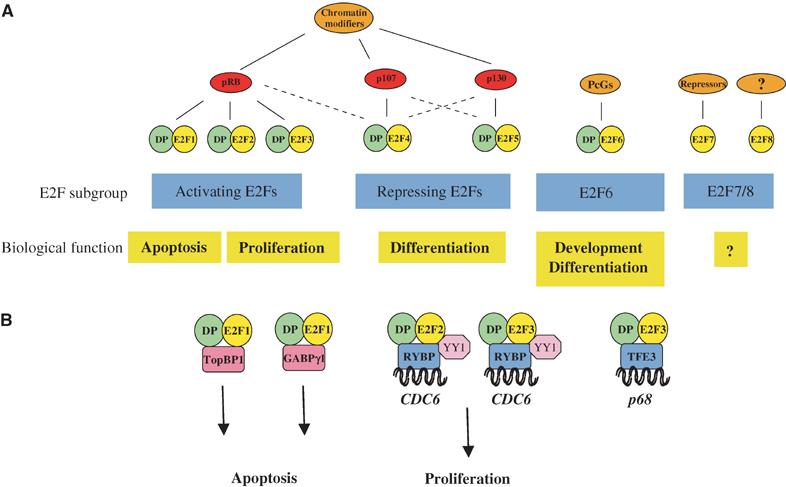

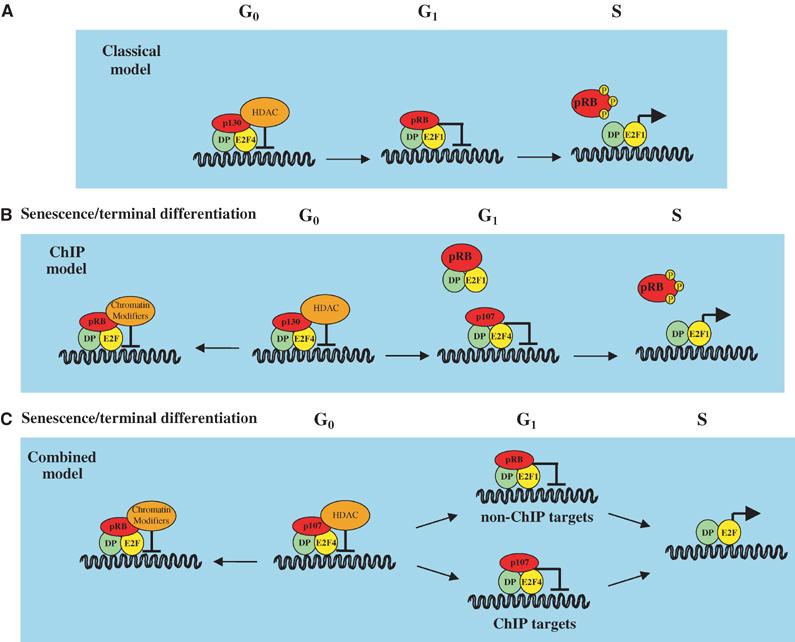

Specificity within the E2F family is achieved via multiple mechanisms, the first level of which comes from interactions with their negative regulators, the pocket proteins, pRB, p107 and p130. While E2Fs 1–3 preferentially bind to pRB, E2F4 is able to bind all the pocket proteins but is regulated mainly by p107 and p130, and E2F5 binds mainly to p130 (Figure 1; for a review, see Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). When E2Fs are bound to pocket proteins, their transactivating activity is inhibited. Phosphorylation of pocket proteins releases the E2Fs, which are then able to activate their target genes. Indeed, overexpression of any of the pocket proteins leads to G1 arrest (Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). These data have provided a classical model for E2F function (Figure 2A). In this model, the predominant complex associated with target promoters in G0 is E2F4/p130, inhibiting the activation of E2F target genes involved in cell cycle progression. As cells enter the cell cycle and approach the G1/S transition, E2F/pRB replaces this complex. pRB dissociates from the activating E2Fs upon its phosphorylation by the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes, allowing target gene activation and, hence, cell cycle progression. Challenging this model, however, is the fact that endogenous pRB has not been found on any human E2F target promoter during the normal cell cycle, and rarely on mouse promoters (Takahashi et al, 2000; Wells et al, 2000; Nielsen et al, 2001; Narita et al, 2003). Indeed, the predominant complex in the G1 phase of the cell cycle appears to be E2F4/p107/p130, which is replaced by free activating E2Fs as the cells enter S phase (Figure 2B). Thus, the classical model may be too simplistic to properly explain the mode of action of the E2F and E2F/pocket protein complexes in E2F target gene regulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the E2F transcription factor subgroups, their physiological roles and specific binding partners. (A) The E2F family is divided into at least four subgroups defined by their regulation by pocket proteins and chromatin modifiers, and by their physiological function (i.e. activation or repression). See text for details. ‘DP' presents DP1 or DP2, ‘chromatin modifiers' refer to chromatin-modifying activities binding to the pRB family members, such as HDAC, Suv39H, BRG1 or HPC2. Recent results from our laboratory have shown that also E2F7 recruits repressors to E2F-dependent promoters (Di Stefano and Helin, unpublished results). (B) Specificity among the E2Fs through protein–protein interactions. TopBP1 and GABPγ1 are specific binding partners of E2F1, while TFE3 binds only to E2F3, and RYBP and YY1 bind only to E2Fs 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Models for the regulation of gene expression by the E2F transcription factors. (A) Classical model for the regulation of E2F-dependent promoters by the E2Fs. This model is based on the original observations of E2F-binding partners, localisation studies and promoter affinities. See text for details of this model. (B) The ‘ChIP model' for E2F regulation of target promoters. Using ChIP assays, pRB has not been found to be associated with promoters containing the E2F consensus site during normal cell cycle progression. Thus, the ChIP model predicts that p130- and p107-, but not pRB-containing complexes, regulate E2F-dependent transcription in proliferating cells, whereas pRB-containing complexes may have a role in regulating E2F-dependent promoters in cells exiting the cell cycle (senescence/terminal differentiation). In addition to HDAC, chromatin modifiers such as Suv39H, BRG1 and HPC2 have also been shown to associate with pRB. (C) The ‘combined model' for E2F regulation of target promoters. This model combines those shown in panels A and B, and postulates that pRB, in association with E2F-DP, also regulates the expression of thus far unidentified E2F target genes (‘non-ChIP targets'), which are important for the regulation of the cell cycle. This model is supported by the observation that inactivation of pRb in mouse cells lead to deregulation of the cell cycle.

E2Fs 6 and 7 are distinct from the other E2Fs in that they do not bind to pocket proteins (Figure 1) (Morkel et al, 1997; Cartwright et al, 1998; Gaubatz et al, 1998; Trimarchi et al, 1998; de Bruin et al, 2003; Di Stefano et al, 2003). Their activity is therefore regulated by a mechanism distinct from that of the other E2Fs. E2F6 is known to interact, and form complexes with, the Polycomb Group (PcG) proteins, but it is not yet clear if these interactions are required to regulate its activity (Trimarchi et al, 2001; Ogawa et al, 2002). While E2F6 has been suggested to have a role in regulating E2F target genes in G0 (Ogawa et al, 2002), it is expressed in all stages of the cell cycle and is therefore likely to have other roles. Indeed, the functional role of E2F6 remains unclear, and consistent with this E2f6 null MEFs show no cell cycle defects (Storre et al, 2002). Interacting partners of E2F7 are yet to be identified; however, E2F7 possesses an additional level of diversity in that it does not require dimerisation with the DP factors for DNA binding, and is thus unique among the E2Fs (Di Stefano et al, 2003).

Specific binding partners

Interaction with the pocket proteins allows separation of function between the activating and repressive E2Fs (and excludes E2Fs 6 and 7), thus conferring one level of biological specificity. Yet, each individual E2F transcription factor possesses unique functions and must attain these by introducing further levels of specificity (Figure 1). One way in which this is achieved is through binding site recognition specificities. While the majority of E2F target promoters are regulated by several of the E2Fs, some promoters are regulated by specific E2Fs. For example, E2F1 has been shown to bind to and repress the Mcl-1 promoter, contributing to apoptosis, while E2F4 is unable to bind this promoter (Croxton et al, 2002). Although this may reflect differences in binding site affinity between the E2Fs, it may also be regulated to some extent by the subunit composition of the E2F complex. E2F4/DP1 displays different DNA-binding site specificities to either E2F4/DP2, E2F1/DP1, E2F1/DP2 or E2F1/DP1/pRB (Tao et al, 1997), showing that there is some specificity of selection for target promoters. Target specificity can also be conferred through binding to protein partners (Figure 1). For example, the E-box-binding factor, TFE3, has been identified as an E2F3-specific partner (Giangrande et al, 2003). Together, E2F3 and TFE3 are specifically able to activate the p68 subunit gene of DNA polymerase α, while E2Fs 1 and 2 are not. E2F3 can also associate with RYBP (Ring1- and YY1-binding protein) and, hence, also with YY1 (Schlisio et al, 2002). However, in this case, E2F2 is also able to interact, although E2F1 is not. Furthermore, the CDC6 promoter, which contains adjacent E2F- and YY1-binding sites, is bound specifically by E2F2 or 3 with RYBP and YY1, and not by E2F1. In contrast, E2F1 can bind specifically to the ETS-related transcription factor, GABPγ1, suppressing E2F1-dependent apoptosis (Hauck et al, 2002). Thus, the choice of the target promoter appears to be controlled by a combination of protein-binding partner and binding-site specificity.

Biological specificity of the activating E2Fs

The ability to induce apoptosis is a specific function of the so-called ‘activating' E2Fs. Indeed, loss of either E2f1 or 3 is able to abrogate most of the apoptosis observed in Rb−/− embryos (Tsai et al, 1998; Ziebold et al, 2001). Thus, Lees and colleagues have proposed a threshold model by which apoptosis is triggered when a critical level of free E2F activity is reached and, accordingly, loss of either E2f1 or 3 is sufficient to suppress apoptosis in Rb−/− embryos (Trimarchi and Lees, 2002). However, in tissue culture-based experiments, E2F1 overexpression has been reported to trigger apoptosis more efficiently than other members of the ‘activating' E2F subclass (DeGregori et al, 1997). Moreover, recent work from the Nevins laboratory strongly suggests that the ability to trigger apoptosis is a specific function of E2F1, thus indicating that it is the levels of E2F1, rather than the levels of free E2Fs, that determine whether a cell undergoes apoptosis (Hallstrom and Nevins, 2003). Further evidence also comes from the observations that E2F1-dependent upregulation of CHK2 is required for E2F-induced apoptosis, and that this also requires ATM and Nbs1 (Powers et al, 2004; Rogoff et al, 2004). Interestingly, E2F1, but not E2F2 or 3, is phosphorylated by ATM and CHK2 upon DNA damage (Lin et al, 2001; Stevens et al, 2003), further supporting the idea that E2F1 is unique among the E2Fs in its proapoptotic activity. Moreover, recent results suggest that E2F1-induced apoptosis is repressed by TopBP1 (DNA topoisomerase IIβ-binding protein 1), which was initially reported to specifically bind the ATM phosphorylated form of E2F1, and not to E2Fs 2 and 3, following DNA damage (Liu et al, 2003). However, TopBP1 has also now been shown to be a critical regulator of E2F1 function during the normal cell cycle (Liu et al, 2004). In spite of this large data set supporting a unique role of E2F1 in regulating apoptosis, it does not explain how loss of E2f3 in vivo can rescue the apoptosis induced by loss of pRb. Since the ability to induce apoptosis in these studies has been addressed only after short-term E2F expression, it is possible that E2F3 can also induce apoptosis, but with slower kinetics compared to E2F1. Indeed studies that evaluated the effect of E2F3 overexpression for a prolonged period of time have shown that E2F3 also triggers apoptosis (Moroni et al, 2001; Lazzerini Denchi and Helin, unpublished results). Thus, it is likely that E2Fs 1 and 3 trigger apoptosis through distinct mechanisms, which could explain the apparent discrepancy between in vivo and tissue culture-based experiments.

Nevertheless, the differential ability of ‘activating' E2Fs to trigger apoptosis supports the notion of specificity among members of the same subclass of E2Fs, and implies a specific regulation and molecular function of different E2Fs. In the last few years, considerable effort has been made to understand the mechanisms through which E2F1 induces apoptosis, and several E2F-responsive proapoptotic genes have been identified. Among these are ARF, p73, APAF1, Casp3, Casp7 and several members of the BH3-only family (Irwin et al, 2000; Stiewe and Putzer, 2000; Moroni et al, 2001; Müller et al, 2001; Nahle et al, 2002). Taking these data into consideration, E2F deregulation thus appears to lead to apoptosis via the regulation of a number of genes triggering mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis.

Biological specificity of the repressive E2Fs

As well as regulating proliferation, the pocket protein family is known to control cell differentiation in different tissues, a function that is partly dependent on the regulation of the E2Fs. E2Fs 4 and 5 are generally considered to be the E2Fs involved in differentiation, and loss of E2fs 4 and 5 results in severe developmental defects, as described previously (Lindeman et al, 1998; Humbert et al, 2000; Rempel et al, 2000). Yet, E2Fs 4 and 5 are also considered to play a role in G0 and early G1. Thus, it is surprising that MEFs null for these genes do not display proliferative defects, and suggests that E2f3b, E2F6, or E2F7 compensate for their loss. Interestingly, this is consistent with the phenotype of p107/p130−/− MEFs (Hurford et al, 1997), implying that pRb can compensate for loss of the other two pocket proteins. Yet, inactivation of all the three pocket proteins, as observed in cancer cell lines such as in HeLa and 293 cells, does not result in gross alterations of the ‘normal' cell cycle, a surprising observation considering that the activity of E2Fs 1–5 is deregulated in these cells. The only apparent effect of loss of the pocket proteins is the inability to enter G0 upon serum removal, suggesting that the role of the E2Fs and pocket proteins is chiefly to regulate cell cycle exit, rather than controlling events within the cell cycle. These observations raise several intriguing questions regarding the role of the E2Fs and pocket proteins, which will be addressed in the sections below.

Outstanding questions

Does pRB regulate the cell cycle?

One important question that arises is whether pRB plays a role in regulating normal cell cycle progression? Based on the classical model for E2F function (Figure 2A), one would expect to see abundant levels of pRB on E2F target promoters in G1. In contrast, pRB is rarely found on these promoters in the normal cell cycle, and current chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data suggest a role for pRB in cell cycle exit, rather than cell cycle progression (Figure 2B). Indeed, the predominant complex associated with human E2F target promoters in G0 is E2F4/p130, which is replaced by E2F4/p107 and not by a pRB-containing E2F complex as cells re-enter the cell cycle (Takahashi et al, 2000). The lack of pRB on E2F target promoters has also been shown in asynchronously growing murine cells (Wells et al, 2000). However, this study found pRb associated with the Cdc2 promoter at the G1/S transition and in S phase, and with the Ccne1 promoter from G0 to G1/S phase, a discrepancy that may represent cell- or species-type specificity. pRB has also been found on E2F target promoters in U2OS cell growth arrested by ectopic p16 expression (Dahiya et al, 2001; Young and Longmore, 2004), suggesting a role for pRB in cell cycle exit. This has been further supported by data showing the recruitment of pRB to E2F target genes upon the induction of senescence (Narita et al, 2003). Together, these data suggest that pRB plays a role in the repression of E2F target genes upon cell cycle exit, but does not exclude a role for pRB in the ongoing cell cycle. Indeed, there is a convincing body of evidence supporting this. Significantly, pRB/activating E2F complexes were discovered using in vitro DNA-binding assays (Chellappan et al, 1991), and, although the overall doubling time of Rb−/− MEFs is similar to wild type, they exhibit a shorter G1 phase of the cell cycle (Herrera et al, 1996). pRb-deficient MEFs also show elevated mRNA and protein levels of E2F target genes, again, consistent with a role for pRb within the cell cycle (Almasan et al, 1995; Herrera et al, 1996). Since loss of both p107 and p130 results in inappropriate activation of a different subset of E2F target genes, this suggests that there are distinct subsets of pRb- and p107/p130-responsive cell cycle regulated targets (Hurford et al, 1997).

Ultimately, it is likely that both situations are true and pRB has roles both within and outside the cell cycle (Figure 2C). Indeed, recent evidence from Drosophila indicates that two distinct types of E2F complexes are formed, one regulating cell cycle genes that are activated by dE2F1, and the second regulating differentiation factors that are developmentally regulated and, hence, repressed throughout the cell cycle by dE2F2/dRBF1 or dE2F2/dRBF2 complexes (Dimova et al, 2003).

Are E2Fs required for cellular proliferation?

Another outstanding question in the field is whether E2Fs are actually required for cellular proliferation? The question arises since unicellular eukaryotes such as yeast cells do not possess homologues of the pRB or E2F proteins despite the conservation of a number of other genes required for proliferation, suggesting that the pRB/E2F pathway may have evolved later during evolution, as a mechanism to control differentiation and developmental processes. Accordingly, pocket proteins in a multicellular organism, controlling the balance between repressing/activating E2Fs, would be able to push proliferating cells towards cell cycle withdrawal (e.g. terminal differentiation). Ablation of both repressing and activating E2Fs would, therefore, impair the ability of cells to exit the cell cycle, but would not necessarily interfere with cellular proliferation. Thus, the observation that loss of ‘activating' E2Fs in mammalian cells results in loss of cellular proliferation could be due to replacement of the repressor E2Fs or of E2F3b on target promoters (Wu et al, 2001; Aslanian et al, 2004). Elegant work from the Dyson laboratory suggests that this is the case in Drosophila. The Drosophila genome encodes only two E2F genes, de2f1 (the activating E2F) and de2f2 (the repressive E2F). While loss of de2f1 results in slow growth and abnormal larval development, concomitant loss of de2f2 almost completely suppresses these effects (Frolov et al, 2001). Furthermore, while de2f1 mutant clones fail to proliferate in eye and wing imaginal discs, de2f1; def2f2 mutants display relatively normal patterns of DNA synthesis in the eye discs. Thus, in Drosophila, E2F is not required for normal proliferation; rather, the net effect of the two proteins allows a tighter control over the process, thus aiding its regulation (Figure 3C). In mammalian cells, the presence of several E2F family members has so far precluded such a careful genetic analysis. Analysis of the effect of loss of DP proteins, however, could provide a simpler system to study the effects of loss of activating and repressing E2F activity. Both the activating E2Fs (1–3a) and the repressing E2Fs (3b–6) need to dimerise with DP1 or DP2 to bind DNA, thus the outcome of DP1/2 loss would ultimately be the ablation of all E2F activity from chromatin, with the exception of E2F7. Interestingly, Dp1−/− embryonic cells do not show impaired proliferation, however embryos die early during embryogenesis most likely due to severe trophoblast defects. Further analysis of conditional Dp1−/− animals or, alternatively, DP1 null cells will likely clarify the requirement of E2F activity in cellular proliferation.

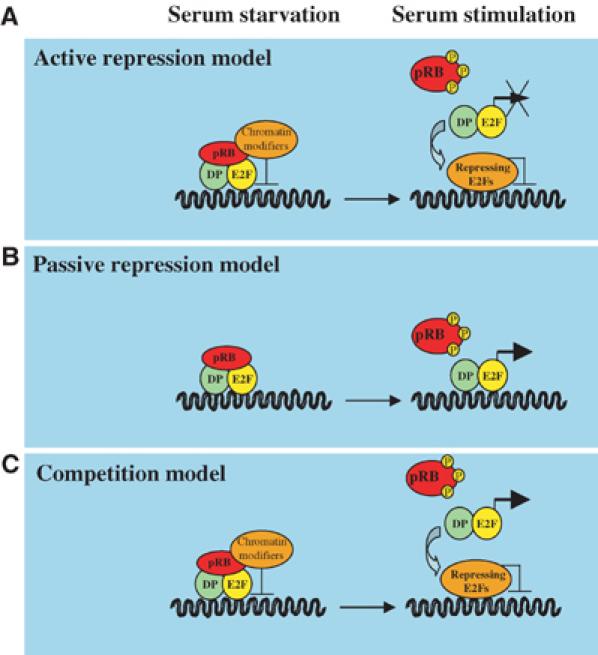

Figure 3.

Models for the mechanism of regulation of E2F-dependent promoters. (A) ‘Active repression model': repressing E2Fs recruit chromatin modifiers to E2F-dependent promoters; thus, this repression must be relieved (chromatin remodelling) before promoters can be activated. In addition, the repressing E2Fs physically prevent binding of the E2F target promoter by the activating E2Fs. In this model, and in the models shown in panels B and C, pRB represents the pRB family members. (B) ‘Passive repression model': pRB prevents E2F promoter activation by binding to the transactivation domains of the E2Fs. This binding may also prevent the recruitment of essential co-activators to the promoter. Repression is relieved by phosphorylation of pRB and its concomitant dissociation from E2Fs, freeing the transactivation domain for activity. (C) ‘Competition model': the activating and repressing E2Fs compete for binding to the E2F DNA-binding site. This model also includes the recruitment of chromatin modifiers by pRB family members.

Is E2F transactivation activity required for proliferation?

Despite the established role played by the ‘activating' E2Fs during the cell cycle, some issues remain unanswered regarding the molecular mechanisms by which these factors control transcription. According to the classical model, phosphorylation of pRB and the resulting dissociation of pRB from E2F lead to the transcriptional activation of E2F-dependent promoters. This has been challenged by the observation that E2F-binding sites within certain E2F-responsive promoters act as negative regulators of transcription in transactivation assays, suggesting that the overall contribution of the E2Fs to promoter activity is negative (Hamel et al, 1992; Weintraub et al, 1992). Consistent with these reports is the finding that a deletion mutant of E2F1 lacking the transactivation domain but retaining the DNA-binding domain, E2F1 (1–374), has properties similar to wild-type E2F1 when expressed in cellular systems (Zhang et al, 1999; Harbour and Dean, 2000; Rowland et al, 2002). These data suggest that displacement of pRB-E2F repressor complexes, through E2F1 (1–374) expression, is sufficient to derepress E2F target genes and promote proliferation (Figure 3A). Collectively, the implication of these findings is that E2F transactivation activity is largely dispensable for the regulation of its targets; thus, the main role of E2Fs in cellular proliferation would be to repress E2F target genes. However, other reports suggest that E2F transactivation ability plays a crucial positive role in the activation of E2F target genes (Figure 3B). For example, mutations in E2F-binding sites in the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) promoter indicate that E2F binding is required to induce DHFR expression at the G1/S transition (Means et al, 1992). Moreover, E2F can activate the expression of simple reporter constructs that contain multiple E2F-binding sites (Helin et al, 1992; Shan et al, 1992), and there is a significant correlation between the ability of E2F to activate transcription and to drive cell cycle progression (Johnson et al, 1993; Shan and Lee, 1994; Qin et al, 1995).

Recently, the analysis of triple knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts lacking E2fs 1–3 (TKO MEFs) revealed that ‘activating' E2Fs are required for cellular proliferation (Wu et al, 2001). However, analysis of these MEFs did not address whether the main function of E2fs is to positively regulate gene expression in S phase or negatively regulate gene expression in G0–G1. TKO MEFs are severely impaired in proliferation and the expression of E2F target genes is strongly affected by loss of the ‘activating' E2Fs. Surprisingly, some E2F targets, such as Pcna, Ccne1 and Rr2, are strongly upregulated in TKO MEFs, while other E2F targets, such as Cdc6, Dhfr and Mcm3, are strongly downregulated in TKO MEFs. This suggests that E2Fs behave as transcriptional activators of a certain subset of E2F targets (Figure 3B), while others are regulated through active transcriptional repression by pRB–E2F complexes (Figure 3A). However, the interpretation of these experiments is somewhat complicated, since the ablation of the residual E2F activity in the parental cell line (E2f1−/− E2f2−/− E2f3f/f, to generate TKO MEFs) was performed in cycling cells; thus, the expression of certain E2F targets might be indirectly affected by the cell cycle arrest imposed by loss of E2F activity.

Taken together, these conflicting data raise the question whether E2F-binding sites are to be considered positive regulators of gene expression in S phase or negative regulators of gene expression in G0–G1. This question is still open; however, it is important to note that most of the studies performed so far are based on overexpression of E2Fs and on the behaviour of plasmids containing E2F promoters. Only from studies in which E2F-binding sites are mutated in its natural setting, and from the analysis of ‘knock-in' mice, will it be possible to definitively state the contribution to gene expression of E2F-binding sites and of E2F protein domains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Lees for critical reading of the manuscript. CA was supported by a EU Marie Curie fellowship and ELD is a fellow of Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC). This work was supported by grants from the AIRC, the Danish Ministry of Research and the Danish Medical Research Council.

References

- Almasan A, Yin Y, Kelly RE, Lee EY, Bradley A, Li W, Bertino JR, Wahl GM (1995) Deficiency of retinoblastoma protein leads to inappropriate S-phase entry, activation of E2F-responsive genes, and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 5436–5440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanian A, Iaquinta PJ, Verona R, Lees JA (2004) Repression of the Arf tumor suppressor by E2F3 is required for normal cell cycle kinetics. Genes Dev 18: 1413–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright P, Müller H, Wagener C, Holm K, Helin K (1998) E2F-6: a novel member of the E2F family is an inhibitor of E2F-dependent transcription. Oncogene 17: 611–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellappan S, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz J, Nevins J (1991) The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell 65: 1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxton R, Ma Y, Song L, Haura EB, Cress WD (2002) Direct repression of the Mcl-1 promoter by E2F1. Oncogene 21: 1359–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya A, Wong S, Gonzalo S, Gavin M, Dean DC (2001) Linking the Rb and Polycomb pathways. Mol Cell 8: 557–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin A, Maiti B, Jakoi L, Timmers C, Buerki R, Leone G (2003) Identification and characterization of E2F7, a novel mammalian E2F family member capable of blocking cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem 278: 42041–42049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregori J (2002) The genetics of the E2F family of transcription factors: shared functions and unique roles. Biochim Biophys Acta 1602: 131–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregori J, Leone G, Miron A, Jakoi L, Nevins JR (1997) Distinct roles for E2F proteins in cell growth control and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7245–7250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano L, Jensen MR, Helin K (2003) E2F7, a novel E2F featuring DP-independent repression of a subset of E2F-regulated genes. EMBO J 22: 6289–6298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova DK, Stevaux O, Frolov MV, Dyson NJ (2003) Cell cycle-dependent and cell cycle-independent control of transcription by the Drosophila E2F/RB pathway. Genes Dev 17: 2308–2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolov MV, Huen DS, Stevaux O, Dimova D, Balczarek-Strang K, Elsdon M, Dyson NJ (2001) Functional antagonism between E2F family members. Genes Dev 15: 2146–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaubatz S, Lindeman GJ, Ishida S, Jakoi L, Nevins JR, Livingston DM, Rempel RE (2000) E2F4 and E2F5 play an essential role in pocket protein-mediated G1 control. Mol Cell 6: 729–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaubatz S, Wood JG, Livingston DM (1998) Unusual proliferation arrest and transcriptional control properties of a newly discovered E2F family member, E2F-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9190–9195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrande PH, Hallstrom TC, Tunyaplin C, Calame K, Nevins JR (2003) Identification of E-box factor TFE3 as a functional partner for the E2F3 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 23: 3707–3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrom TC, Nevins JR (2003) Specificity in the activation and control of transcription factor E2F-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10848–10853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel PA, Gill RM, Phillips RA, Gallie BL (1992) Transcriptional repression of the E2-containing promoters EIIaE, c-myc, and RB1 by the product of the RB1 gene. Mol Cell Biol 12: 3431–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Dean DC (2000) The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev 14: 2393–2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck L, Kaba RG, Lipp M, Dietz R, von Harsdorf R (2002) Regulation of E2F1-dependent gene transcription and apoptosis by the ETS-related transcription factor GABPgamma1. Mol Cell Biol 22: 2147–2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helin K, Lees JA, Vidal M, Dyson N, Harlow E, Fattaey A (1992) A cDNA encoding a pRB-binding protein with properties of the transcription factor E2F. Cell 70: 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera RE, Sah VP, Williams BO, Mäkelä TP, Weinberg RA, Jacks T (1996) Altered cell cycle kinetics, gene expression, G1 restriction point regulation in Rb-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol 16: 2403–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert PO, Rogers C, Ganiatsas S, Landsberg RL, Trimarchi JM, Dandapani S, Brugnara C, Erdman S, Schrenzel M, Bronson RT, Lees JA (2000) E2F4 is essential for normal erythrocyte maturation and neonatal viability. Mol Cell 6: 281–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurford RKJ, Cobrinik D, Lee M-H, Dyson N (1997) pRB and p107/p130 are required for the regulated expression of different sets of E2F responsive genes. Genes Dev 11: 1447–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, MC MCM, Phillips AC, Seelan RS, Smith DI, Liu W, Flores ER, Tsai KY, Jacks T, Vousden KH, Kaelin WG Jr (2000) Role for the p53 homologue p73 in E2F-1-induced apoptosis. Nature 407: 645–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DG, Schwarz JK, Cress WD, Nevins JR (1993) Expression of transcription factor E2F1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature 365: 349–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WC, Lin FT, JR N (2001) Selective induction of E2F1 in response to DNA damage, mediated by ATM-dependent phosphorylation. Genes Dev 15: 1833–1844 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman GJ, Dagnino L, Gaubatz S, Xu Y, Bronson RT, Warren HB, Livingston DM (1998) A specific, nonproliferative role for E2F-5 in choroid plexus function revealed by gene targeting. Genes Dev 12: 1092–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Lin F-T, Ruppert JM, Lin W-C (2003) Regulation of E2F1 by BRCT domain-containing protein TopBP1. Mol Cell Biol 23: 3287–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Luo Y, Lin F-T, Lin W-C (2004) TopBP1 recruits Brg1/Brm to repress E2F1-induced apoptosis, a novel pRb-independent and E2F1-specific control for cell survival. Genes Dev 18: 673–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J, Petersen BO, Holm K, Bartek J, Helin K (1996) Deregulated expression of E2F family members induces S-phase entry and overcomes p16INK4A-mediated growth suppression. Mol Cell Biol 16: 1047–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means AL, Slansky JE, McMahon SL, Knuth MW, Farnham PJ (1992) The HIP binding site is required for growth regulation of the dihydrofolate reductase promoter. Mol Cell Biol 12: 1054–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morkel M, Winkel J, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T, Hagemeier C (1997) An E2F-like repressor of transcription. Nature 390: 567–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni MC, Hickman ES, Caprara G, LDenchi E, Colli E, Cecconi F, Müller H, Helin K (2001) APAF-1 is a transcriptional target for E2F and p53. Nat Cell Biol 3: 552–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H, Bracken AP, Vernell R, Moroni MC, Christians F, Grassilli E, Prosperini E, EVigo Oliner JD, Helin K (2001) E2Fs regulate the expression of genes involved in differentiation, development, proliferation and apoptosis. Genes Dev 15: 267–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H, Moroni MC, Vigo E, Petersen BO, Bartek J, Helin K (1997) Induction of S-phase entry by E2F transcription factors depends on their nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol 17: 5508–5520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahle Z, Polakoff J, Davuluri RV, McCurrach ME, Jacobson MD, Narita M, Zhang MQ, Lazebnik Y, Bar-Sagi D, Lowe SW (2002) Direct coupling of the cell cycle and cell death machinery by E2F. Nat Cell Biol 4: 859–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW (2003) Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 113: 703–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SJ, Schneider R, Bauer UM, Bannister AJ, Morrison A, O'Carroll D, Firestein R, Cleary M, Jenuwein T, Herrera RE, Kouzarides T (2001) Rb targets histone H3 methylation and HP1 to promoters. Nature 412: 561–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Ishiguro K-I, Gaubatz S, Livingston DM, Nakatani Y (2002) A complex with chromatin modifiers that occupies E2F- and Myc-responsive genes in G0 cells. Science 296: 1132–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JT, Hong S, Mayhew CN, Rogers PM, Knudsen ES, Johnson DG (2004) E2F1 uses the ATM signaling pathway to induce p53 and Chk2 phosphorylation and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res 2: 203–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X-Q, Livingston DM, Ewen M, Sellers WR, Arany Z, Kaelin WG (1995) The transcription factor E2F-1 is a downstream target for RB action. Mol Cell Biol 15: 742–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel RE, Saenz-Robles MT, Storms R, Morham S, Ishida S, Engel A, Jakoi L, Melhem MF, Pipas JM, Smith C, Nevins JR (2000) Loss of E2F4 activity leads to abnormal development and multiple cellular lineages. Mol Cell 6: 293–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff HA, Pickering MT, Frame FM, Debatis ME, Sanchez Y, Jones S, Kowalik TF (2004) Apoptosis associated with deregulated E2F activity is dependent on E2F1 and Atm/Nbs1/Chk2. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2968–2977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland BD, Denissov SG, Douma S, Stunnenberg HG, Bernards R, Peeper DS (2002) E2F transcriptional repressor complexes are critical downstream targets of p19(ARF)/p53-induced proliferative arrest. Cancer Cell 2: 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlisio S, Halperin T, Vidal M, Nevins JR (2002) Interaction of YY1 with E2Fs, mediated by RYBP, provides a mechanism for specificity of E2F function. EMBO J 21: 5775–5786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Lee W-H (1994) Deregulated expression of E2F-1 induces S-phase entry and leads to apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 14: 8166–8173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Zhu X, Chen P-L, Durfee T, Yang Y, Sharp D, Lee W-H (1992) Molecular cloning of cellular genes encoding retinoblastoma-associated proteins: identification of a gene with properties of the transcription factor E2F. Mol Cell Biol 12: 5620–5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C, Smith L, La Thangue NB (2003) Chk2 activates E2F-1 in response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol 5: 401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiewe T, Putzer BM (2000) Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat Genet 26: 464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storre J, Elsasser HP, Fuchs M, Ullmann D, Livingston DM, Gaubatz S (2002) Homeotic transformations of the axial skeleton that accompany a targeted deletion of E2f6. EMBO Rep 3: 695–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Rayman JB, Dynlacht BD (2000) Analysis of promoter binding by the E2F and pRB families in vivo: distinct E2F proteins mediate activation and transactivation. Genes Dev 14: 804–816 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Kassatly RF, Cress WD, Horowitz JM (1997) Subunit composition determines E2F DNA-binding site specificity. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6994–7007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi J, Fairchild B, Verona R, Moberg K, Andon N, Lees JA (1998) E2F-6, a member of the E2F family that can behave as a transcriptional repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2850–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Fairchild B, Wen J, Lees JA (2001) The E2F6 transcription factor is a component of the mammalian Bmi1-containing polycomb complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1519–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Lees JA (2002) Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KY, Hu Y, Macleod KF, Crowley D, Yamasaki L, Jacks T (1998) Mutation of E2F1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S-phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol Cell 2: 293–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona R, Moberg K, Estes S, Starz M, Vernon JP, Lees JA (1997) E2F activity is regulated by cell cycle-dependent changes in subcellular localization. Mol Cell Biol 17: 7268–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub SJ, Prater CA, Dean DC (1992) Retinoblastoma protein switches the E2F site from positive to negative element. Nature 358: 259–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J, Boyd KE, Fry CJ, Bartley SM, Farnham PJ (2000) Target gene specificity of E2F and pocket protein family members in living cells. Mol Cell Biol 20: 5797–5807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Timmers C, Maiti B, Saavedra HI, Sang L, Chong GT, Nuckolls F, Giangrande P, Wright FA, Field SJ, Greenberg ME, Orkin S, Nevins JR, Robinson ML, Leone G (2001) The E2F1–3 transcription factors are essential for cellular proliferation. Nature 414: 457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AP, Longmore GD (2004) Differences in stability of repressors complexes at promoters underlie distinct roles for Rb family members. Oncogene 23: 814–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HS, Postigo AA, Dean DC (1999) Active transcriptional repression by Rb-E2F complex mediates G1 arrest triggered by p16INK4A, TGFβ and contact inhibition. Cell 97: 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebold U, Reza T, Caron A, Lees J (2001) E2F3 contributes both to the inappropriate proliferation and to the apoptosis arising in Rb mutant embryos. Genes Dev 15: 386–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]