Abstract

Introduction

Mortality prediction scores are widely used in intensive care units (ICUs) and in research, but their predictive value deteriorates as scores age. Existing mortality prediction scores are imprecise and complex, which increases the risk of missing data and decreases the applicability bedside in daily clinical practice. We propose the development and validation of a new, simple and updated clinical prediction rule: the Simplified Mortality Score for use in the Intensive Care Unit (SMS-ICU).

Methods and analysis

During the first phase of the study, we will develop and internally validate a clinical prediction rule that predicts 90-day mortality on ICU admission. The development sample will comprise 4247 adult critically ill patients acutely admitted to the ICU, enrolled in 5 contemporary high-quality ICU studies/trials. The score will be developed using binary logistic regression analysis with backward stepwise elimination of candidate variables, and subsequently be converted into a point-based clinical prediction rule. The general performance, discrimination and calibration of the score will be evaluated, and the score will be internally validated using bootstrapping. During the second phase of the study, the score will be externally validated in a fully independent sample consisting of 3350 patients included in the ongoing Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in the Intensive Care Unit trial. We will compare the performance of the SMS-ICU to that of existing scores.

Ethics and dissemination

We will use data from patients enrolled in studies/trials already approved by the relevant ethical committees and this study requires no further permissions. The results will be reported in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of multivariate prediction models for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement, and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal.

Keywords: INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Publication of a protocol for an observational study reduces risk of bias and increases transparency.

Use of prospectively recorded data from international, contemporary, high-quality studies/trials increase data validity and generalisability.

Use of 90-day mortality as outcome measure will not be affected by intensive care unit (ICU)/hospital discharge practices, as compared with in-ICU or in-hospital mortality.

The original study/trial databases comprise a limited number of variables because of the pragmatic designs.

The included participants, interventions and comparators assessed in the original studies/trials differ slightly, but all patients were adults acutely admitted to an ICU.

Introduction

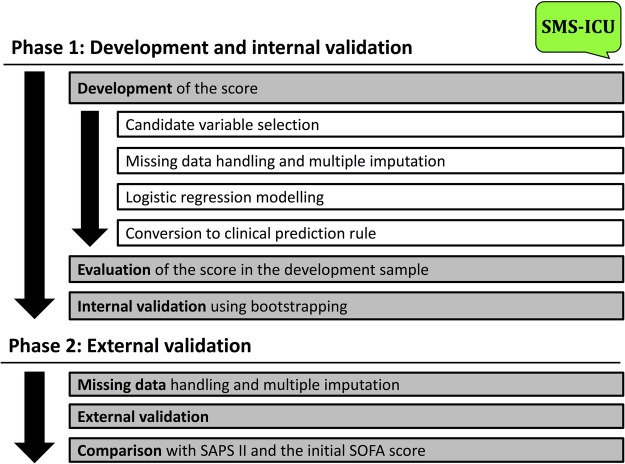

This protocol describes the development of a new clinical prediction rule for use in the intensive care unit (ICU): the Simplified Mortality Score for use in the Intensive Care Unit (SMS-ICU). The protocol describes the derivation and internal validation of the score (phase 1) and the external validation (phase 2). An overview of the steps described in the protocol is provided in figure 1. This manuscript has been prepared according to the Transparent Reporting of multivariate prediction models for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement1 (checklist included as online supplementary file 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the major steps in the development and validation of the score as described in this protocol. SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SMS-ICU, Simplified Mortality Score for the Intensive Care Unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

bmjopen-2016-015339supp1.pdf (116.6KB, pdf)

Background

Severity scores are used in ICUs to assess disease severity, make prognostic predictions, compare the performance of ICUs and in research.2–4 The performance of severity scores deteriorates over time,5 6 and one of the most widely used mortality prediction scores, the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, is more than 20 years old.7

Most mortality prediction scores include many different variables and are thus very complex. This limits clinical use and increases the risk of missing data which is a common challenge when used in research.8–10 More complex scores do not necessarily perform better, and the performance of the newer and more complex SAPS 311 is comparable to that of SAPS II.12–16 The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score17 is somewhat simpler than SAPS II, and although it was not developed for this purpose, it appears to be only slightly inferior to SAPS II at predicting mortality.18 19 Recently, Dólera-Moreno et al20 presented a simple score that predicts in-ICU mortality, based on data from a single ICU.

A simple and contemporary clinical prediction rule using few readily available variables developed on data from multiple centres and using 90-day mortality as the outcome measure, could prove a valuable tool for use at the bedside in daily clinical practice in the ICU and in research.

Hypothesis and aim

We hypothesise that a new, simple and clinically useful mortality prediction score for use in the ICU can be developed and used to reliably estimate the risk of mortality within 90 days of admission to the ICU. Additionally, we hypothesise that such a score will perform as well as existing and more complex scores (ie, SAPS II).

Accordingly, we aim to develop and validate a simple clinical prediction rule—the SMS-ICU—which can be used at the bedside on ICU admission to reliably estimate the risk of mortality 90 days after ICU admission.

Methods and analysis

As described by Labarère et al,21 the development of clinical prediction rules encompasses three consecutive phases: derivation, external validation and impact analysis. This protocol describes the derivation and internal validation (phase 1) and the external validation (phase 2) of the score. If the score performs satisfactory during the validations, we will encourage use of the score in everyday clinical practice and subsequently conduct an impact analysis the details of which will be planned later.

Phase 1: development and internal validation

In the first phase of the project, a mortality prediction model will be developed, evaluated and converted into a simple score that can be used at the bedside. Subsequently, the score will be internally validated.

Study design

An international cohort study comprising patients from the Scandinavian Starch for Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock (6S) trial,8 the Transfusion Requirements In Septic Shock (TRISS) trial,9 the Conservative versus Liberal Approach to fluid therapy of Septic Shock in Intensive Care (CLASSIC) trial,22 the Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in the Intensive Care Unit (SUP-ICU) inception cohort study10 and the Agents Intervening against Delirium in Intensive Care Unit (AID-ICU) inception cohort study.23

Study participants

All 4247 patients included in the 6S (n=798; 26 ICUs in 4 countries),8 TRISS (n=998; 32 ICUs in 4 countries)9 and CLASSIC trials (n=151; 9 ICUs in 2 countries),22 and in the SUP-ICU (n=1034; 97 ICUs in 11 countries)10 and AID-ICU (n=1266; 99 ICUs in 13 countries)23 inception cohort studies.

The sample consists of adult (≥18 years) critically ill patients acutely admitted to ICUs in university and non-university hospitals. Enrolment of patients in the development sample took place between 23 December 2009 and 30 June 2016. Data collection for the last included patients in the development sample has recently concluded and data are currently undergoing validation. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and enrolment dates for the studies are listed in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2016-015339supp2.pdf (53.6KB, pdf)

Data sources

A combined database comprising data from the 6S, TRISS and CLASSIC trial databases, and from the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort databases.

Variables

The outcome measure will be 90-day mortality (90 days following inclusion in the trials/studies). Adverse prognostic factors for 90-day mortality will be assessed.

Table 1 contains a complete list of the variables that will be included in the combined database. All variables are known potential predictors of 90-day mortality, and all variables are registered in the 6S, TRISS, CLASSIC and SUP-ICU trials and in the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort studies. For the selection of candidate variables from this list, see the Statistics section.

Table 1.

Variables studied

| Variable | Data format |

|---|---|

| Demographic/anamnestic variables | |

| Age | Years (continuous) |

| Gender | Male/female (binary) |

| Admission type | Surgical/medical (binary) |

| Hospital length of stay prior to ICU admission | Days (continuous) |

| Comorbidity variables | |

| Metastatic cancer | Yes/no (binary) |

| Haematological malignancy | Yes/no (binary) |

| AIDS | Yes/no (binary) |

| Physiological variables | |

| Lowest heart rate* | Beats per minute (continuous) |

| Highest heart rate* | Beats per minute (continuous) |

| Lowest systolic blood pressure* | mm Hg (continuous) |

| Highest systolic blood pressure* | mm Hg (continuous) |

| Body temperature ≥39° C* | Yes/no (binary) |

| Biochemical variables | |

| Lowest white cell count* | 109/L (continuous) |

| Highest white cell count* | 109/L (continuous) |

| Lowest potassium* | mmol/L (continuous) |

| Highest potassium* | mmol/L (continuous) |

| Lowest sodium* | mmol/L (continuous) |

| Highest sodium* | mmol/L (continuous) |

| Lowest bicarbonate* | mmol/L (continuous) |

| Treatment variables | |

| Use of vasopressors/inotropes† | Yes/no (binary) |

| Use of mechanical ventilation† | Yes/no (binary) |

| Use of renal replacement therapy† | Yes/no (binary) |

| Outcome variable | |

| Vital status 90 days after inclusion | Dead/alive (binary) |

For detailed definitions of the variables, please refer to the original publications/protocols.8–10 22–24

All variables registered at inclusion in the different studies/trials except where otherwise noted.

*Worst value registered during the 24 hours prior to inclusion (6S, TRISS, CLASSIC and SUP-ICU trials) or during the first 24 hours in the ICU (SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohorts).

†Treatment initiated or continued on the day of inclusion.

6S, Scandinavian Starch for Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock; AID-ICU, Agents Intervening against Delirium in Intensive Care Unit; ICU, intensive care unit; CLASSIC, Conservative versus Liberal Approach to fluid therapy of Septic Shock in Intensive Care; SUP-ICU, Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in the Intensive Care Unit; TRISS, Transfusion Requirements In Septic Shock.

Owing to the hard outcome measure, no actions will be taken to blind investigators to the outcome or predictor variables.

Statistics

Baseline and clinical characteristics for all patients in the combined database will be presented as medians with IQRs for continuous data, and numbers (%) for categorical data stratified by 90-day mortality.25 Differences will be assessed by Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test as appropriate.

The score will be developed in five steps:

Candidate predictor variables will be selected;

Candidate variables with more than 25% missing data will be excluded;

For the remaining variables, multiple imputations will be performed for the missing values;

A logistic regression model with 90-day mortality as the outcome of interest will be developed;

The logistic regression model will be converted into a clinical prediction rule.26

Candidate variables

Candidate variables for the score will be selected based on three criteria:

Variables have to be potentially predictive of mortality based on existing literature;

Variables have to be readily available on ICU admission in everyday clinical practice;

Variables have to be present in the 6S, TRISS and CLASSIC trials databases, in the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort study databases, and in the SUP-ICU trial database24 (for external validation, phase 2).

A complete list of candidate variables can be found in table 1.

Missing data and multiple imputation

Candidate variables with more than 25% missing data will be excluded. As data are unlikely to be missing completely at random, multiple imputations for the missing values for the remaining candidate variables will be performed.27 28 Multiple imputations will be performed with the fully conditional specification method with 10 imputed data sets and with the inclusion of the outcome measure and the candidate variables remaining after variables with more than 25% missing data having been excluded.

Multiple imputations for missing outcome data will not be performed and patients with missing 90-day mortality data will be excluded from all analyses.27

Logistic regression modelling

Binary logistic regression analysis including the selected candidate variables as independent co-variates and 90-day mortality as the dependent variable will be performed. Continuous co-variates will not be converted to categorical co-variates during this process. Transformation to address possible non-linearity will be considered. Backward stepwise elimination modelling will be used based on the p values for the individual variables obtained from the likelihood ratio test.21 To ensure that the score is suitable for use at the bedside, we will aim to limit the number of variables to ensure simplicity and clinical relevance. In order to do this, a prespecified significance threshold for the elimination of variables has not been set. Results will be presented as adjusted ORs with 95% CIs and regression coefficients (β-values).

Conversion into the clinical prediction rule

The logistic regression model will be converted into a clinical prediction rule—the SMS-ICU—by transforming the individual parameter estimates (log(OR)/β-values) of the model into weights (points) according to the method used in the Framingham Heart Study.29 Continuous variables will be converted to ordinal categorical variables based on clinically meaningful thresholds and the lowest adjusted OR/β-value will be used as reference for each ordinal variable. An increasing amount of points will then be assigned according to equivalently spaced adjusted OR/β-values.29 The same method will be used for dichotomous variables.29 30 A logistic regression analysis with the total score as the only independent variable and 90-day mortality as the dependent variable will be conducted, and the full regression model will be presented.

Evaluation of the score

Predicted 90-day mortality risks for the different scores along with sensitivity, specificity and observed 90-day mortality in the full derivation sample will be presented.

The score will be evaluated using model diagnostics. The overall predictive performance of the score will be evaluated using Nagelkerke's R2 for binary exposure,31 which refers to the proportion of variation explained by the model. Discrimination, which refers to the score's ability to distinguish patients that die from patients that live, will be assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC).32 Finally, calibration will be assessed as recommended in the literature,21 33 via calibration plots and intercept α and slope β from the regression of the binary outcome (90-day mortality) on the predicted values,34 supplemented by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit Ĉ-statistic.35

Internal validation

The score will be internally validated using bootstrapping.21 The principle of bootstrapping is to sample from the empirical distribution from which the data originated (ie, sampling with replacement from the observed data).26 36

The same performance measures will be used during the internal validation process as during the evaluation process, and optimism-corrected performance estimates will be presented.21

Sensitivity analysis

The development sample will contain data from the randomised 6S, TRISS and CLASSIC trials. In the TRISS and CLASSIC trials, no statistically significant differences in 90-day mortality was observed between the two treatment groups;9 22 however, in the 6S trial, mortality was increased in the group allocated to hydroxyethyl starch (HES) compared with the group allocated to Ringer's acetate.8 Consequently, a sensitivity analysis with removal of the patients allocated to HES (n=398) will be conducted.

Analyses will be conducted using SAS V.9.4 or newer (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). All statistical tests will be two-tailed. In general, p values <0.05 will be considered statistically significant and 95% CIs will be presented where appropriate.

Study size and power

The combined database will contain ∼1500 events of death within 90 days.

The SUP-ICU cohort, and the CLASSIC, TRISS and 6S trial databases are static databases and contain 1139 events of death within 90 days. The AID-ICU cohort database will be closed before data are used for the present study, and subsequently be a static database containing ∼380 events of death within 90 days (number of included patients: 1266, expected 90-day mortality: 30%). As a rule of thumb, logistic regression and Cox models should use at least 10 outcome events per predictor to ensure valid predictive modelling.37 38 As 22 candidate variables are evaluated, the combined database will contain enough events for the model to have sufficient power.

Phase 2: external validation

In the second phase of the project, the model will be externally validated in a fully independent sample.21 For the external validation phase, we will use the full cohort of the SUP-ICU trial24 after its completion.

Study design

A preplanned analysis of data from the SUP-ICU trial.24

Study participants

All patients included in the SUP-ICU trial after the completion of the trial and 90-day follow-up24 (n≈3350; currently recruiting in 30 university and non-university ICUs in five countries with more to be added). The SUP-ICU trial includes adult (≥18 years) acutely ill patients admitted to the ICU. Enrolment started on 4 January 2016 and is expected to conclude by the end of 2017, with follow-up during the first half of 2018. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in online supplementary file 2.

Data sources

The SUP-ICU trial database will be used after completion of the trial and validation of the database, and will at this time be a static database.

Statistics

Baseline and clinical characteristics for all patients in the SUP-ICU trial24 will be stratified by 90-day mortality and presented as medians with IQRs for continuous data, and numbers (%) for categorical data.25 Differences will be assessed by Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test as appropriate.

Missing data in the SUP-ICU trial database for the relevant variables will be handled using multiple imputations, as recently recommended.39 Multiple imputations with 10 imputed data sets and inclusion of the outcome measure and the respective predictor variables included in each score will be performed.27 28 Patients with missing outcome data (90-day mortality) will be excluded from the external validation.27

For the external validation, the same measures of overall performance, discrimination and calibration will be used to evaluate the score as in phase 1 (above). Additionally, the performance of the SMS-ICU will be compared with that of SAPS II7 and the initial SOFA score17 in the external validation sample. For SAPS II, overall performance, discrimination and calibration will be assessed. For the initial SOFA score, only discrimination will be assessed as the SOFA score includes no prediction model.17 Discrimination of SMS-ICU, SAPS II and SOFA (AUCs) will be compared using the method described by DeLong et al.40

Sensitivity analysis

As we do not yet know if 90-day mortality will differ between the two groups in the SUP-ICU trial, the external validation will be conducted using the full study population. Two preplanned sensitivity analyses will be conducted by repeating the analyses in either group.

Analyses will be conducted using SAS V.9.4 or newer (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). All statistical tests will be two-tailed. p values <0.05 will be considered statistically significant and 95% CIs will be presented where appropriate.

Study size and power

Assuming a 25% 90-day mortality rate in the SUP-ICU trial24 there will be ∼840 deaths during follow-up. Generally, at least 100 events and 100 non-events are recommended for external validation studies.21 41 The external validation sample is comparable in size with the derivation sample and is thus of sufficient size to evaluate the performance of the score.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include publication of the protocol including a statistical analysis plan prior to development and validation of the score. Publication of protocols of observational studies, including studies developing and reporting prediction models is currently not mandatory or common practice. Publication of protocols is important, as it increases transparency and decreases the risk of bias, data-driven analyses and post hoc changes in design.42 Second, both the development and external validation phases will use contemporary data from international high-quality studies/trials with prospective data collection. This increases data quality and geographical generalisability. Third, our score will use 90-day mortality as the outcome measure. Existing scores generally use ICU or in-hospital mortality as outcome measures; however, score performance is affected by the choice of outcome43 44 and longer fixed-time outcome measures are currently recommended.45

Our study has limitations too. First, the selection of candidate variables is limited by the availability of these variables across the five original studies used in the development phase. These variables, however, have previously been identified as predictors of mortality and are used in existing mortality prediction scores.7 Second, the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the original studies differ slightly which may limit generalisability of the score. However, we believe that the use of five contemporary high-quality studies/trials including less, moderately and severely ill ICU patients (SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort studies) and more severely ill patients (6S, TRISS and CLASSIC trials) ensures that the score will perform adequately across a large spectrum of illness severities in the ICU. Third, missing data may affect the development and validation of the score, but this is handled using recommended, contemporary methods (multiple imputation).27 Finally, the majority of patients were included in Europe and thus geographical generalisability may be limited outside Europe.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics and approvals

The 6S, TRISS, CLASSIC and SUP-ICU trials, and the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort studies have all been approved by the relevant institutions. Full details regarding ethics and approvals can be found in the original papers/protocols.8–10 22–24 No further ethics approvals for the present study are necessary due to the non-interventional (observational) design.

The development of the score will in no way affect patient safety or subject participants to any additional or increased risks.

All original study databases have been approved and are maintained according to Danish laws. Anonymised data sets containing only the relevant variables (table 1) will be extracted from the original study databases and used for the present study, and the deposition of these databases does not require further approvals.

Dissemination

Results will be reported in compliance with the TRIPOD statement1 and published in an international peer-reviewed journal and presented at relevant academic conferences, regardless of the findings. If the score performs satisfactory during the validations, we will develop an app, a web calculator and/or a pocket guide to facilitate easy calculation of the score at the bedside and encourage its use in ICUs.

Data will be available on request to the corresponding author. If required by the publishing journals, data will be provided with the submitted manuscripts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of all authors and investigators involved in the 6S, TRISS, CLASSIC and SUP-ICU trials and in the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort studies. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the patients included in all the above trials and studies for participating.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Anders Granholm @andersgranholm Anders Perner @AndersPerner Lars Broksø Holst @larsbjoh Søren Marker @SoerenMarker and Peter Buhl Hjortrup @pbhjortrup

Contributors: The idea for the project was conceived by AG, AP, PBH and MHM. AG and MHM drafted the protocol and manuscript. AG, AKGJ and MHM developed the statistical analysis plan. AG, AP, MK, PBH, NH, LBH, SM, MOC, AKGJ and MHM have all been involved in the development, conduct and/or data collection of one or more of the 6S, TRISS, CLASSIC and SUP-ICU trials and the SUP-ICU and AID-ICU inception cohort studies. The protocol and manuscript were critically revised by AG, AP, MK, PBH, NH, LBH, SM, MOC, AKGJ and MHM. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the publication of the protocol.

Funding: This project is supported by a research grant from Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet's Research Council. For funding of the original studies, please refer to the original manuscripts or protocols.8–10 22–24 The Department of Intensive Care at Rigshospitalet receives support for other research projects from Fresenius Kabi, CSL Behring and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data will be available on request to the corresponding author. If required by the publishing journals, data will be provided with the submitted manuscripts.

References

- 1.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015;350:g7594 10.1136/bmj.g7594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapsang AG, Shyam DC. Scoring systems in the intensive care unit: a compendium. Indian J Crit Care Med 2014;18:220–8. 10.4103/0972-5229.130573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strand K, Flaatten H. Severity scoring in the ICU: a review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:467–78. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent J-L, Moreno R. Clinical review: scoring systems in the critically ill. Crit Care 2010;14:207 10.1186/cc8204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison DA, Brady AR, Parry GJ et al. Recalibration of risk prediction models in a large multicenter cohort of admissions to adult, general critical care units in the United Kingdom. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1378–88. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000216702.94014.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minne L, Eslami S, de Keizer N et al. Effect of changes over time in the performance of a customized SAPS-II model on the quality of care assessment. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:40–6. 10.1007/s00134-011-2390-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 1993;270:2957–63. [Erratum, JAMA 1994;271:1321] 10.1001/jama.1993.03510240069035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer's acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:124–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1381–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krag M, Perner A, Wetterslev J et al. Prevalence and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding and use of acid suppressants in acutely ill adult intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:833–45. 10.1007/s00134-015-3725-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno RP, Metnitz PG, Almeida E et al. SAPS 3—from evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 2: development of a prognostic model for hospital mortality at ICU admission. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:1345–55. 10.1007/s00134-005-2763-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole D, Rossi C, Latronico N et al. Comparison between SAPS II and SAPS 3 in predicting hospital mortality in a cohort of 103 Italian ICUs. Is new always better? Intensive Care Med 2012;38:1280–8. 10.1007/s00134-012-2578-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakr Y, Krauss C, Amaral ACKB et al. Comparison of the performance of SAPS II, SAPS 3, APACHE II, and their customized prognostic models in a surgical intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:798–803. 10.1093/bja/aen291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledoux D, Canivet J-L, Preiser J-C et al. SAPS 3 admission score: an external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:1873–7. 10.1007/s00134-008-1187-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strand K, Søreide E, Aardal S et al. A comparison of SAPS II and SAPS 3 in a Norwegian intensive care unit population. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:595–600. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capuzzo M, Scaramuzza A, Vaccarini B et al. Validation of SAPS 3 admission score and comparison with SAPS II. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:589–94. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01929.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent J-L, Moreno R, Takala J et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707–10. 10.1007/BF01709751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minne L, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E. Evaluation of SOFA-based models for predicting mortality in the ICU: a systematic review. Crit Care 2008;12:R161 10.1186/cc7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granholm A, Møller MH, Krag M et al. Predictive performance of the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II and the initial Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score in acutely ill intensive care patients: post-hoc analyses of the SUP-ICU inception cohort study. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0168948 10.1371/journal.pone.0168948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dólera-Moreno C, Palazón-Bru A, Colomina-Climent F et al. Construction and internal validation of a new mortality risk score for patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Int J Clin Pract 2016;70:916–22. 10.1111/ijcp.12851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labarère J, Renaud R, Fine MJ. How to derive and validate clinical prediction models for use in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:513–27. 10.1007/s00134-014-3227-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjortrup PB, Haase N, Bundgaard H et al. Restricting volumes of resuscitation fluid in adults with septic shock after initial management: the CLASSIC randomised, parallel-group, multicentre feasibility trial. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1695–705. 10.1007/s00134-016-4500-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collet MO, et al. Agents Intervening against Delirium in Intensive Care Unit (AID-ICU): An international inception cohort study (Protocol v. 13.2). Centre for Research in Intensive Care. http://www.cric.nu/aid-icu-protocol-cohort-study-draft-only/ (accessed 18 Oct 2016).

- 24.Krag M, Perner A, Wetterslev J et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor versus placebo in critically ill patients (SUP-ICU trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:205 10.1186/s13063-016-1331-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti C, Boulkedid R. Describing ICU data with tables. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:667–73. 10.1007/s00134-014-3248-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. Statistics for Biology and Health. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vesin A, Azoulay E, Ruckly S et al. Reporting and handling missing values in clinical studies in intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1396–404. 10.1007/s00134-013-2949-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall A, Altman DG, Holder RL et al. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:57 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB Sr. Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: the Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med 2004;23:1631–60. 10.1002/sim.1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Møller MH, Engebjerg MC, Adamsen S et al. The Peptic Ulcer Perforation (PULP) score: a predictor of mortality following peptic ulcer perforation. A cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012;56:655–62. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagelkerke NJD. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991;78:691–2. 10.1093/biomet/78.3.691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982;143:29–36. 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Calster B, Nieboer D, Vergouwe Y et al. A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: from utopia to empirical data. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74:167–76. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller ME, Langefeld CD, Tierney WM et al. Validation of probabilistic predictions. Med Decis Making 1993;13:49–58. 10.1177/0272989X9301300107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol 1982;115:92–106. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. 2nd edn Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrell FEJ, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1373–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins GS, de Groot JA, Dutton S et al. External validation of multivariable prediction models: a systematic review of methodological conduct and reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:40 doi:10.1186-1471-2288-14-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45. 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC et al. Substantial effective sample sizes were required for external validation studies of predictive logistic regression models. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:475–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peat G, Riley RD, Croft P et al. Improving the transparency of prognosis research: the role of reporting, data sharing, registration, and protocols. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001671 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rydenfelt K, Engerström L, Walther S et al. In-hospital vs. 30-day mortality in the critically ill—a 2-year Swedish intensive care cohort analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015:59;846–58. 10.1111/aas.12554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brinkman S, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E et al. Prediction of long-term mortality in ICU patients: model validation and assessing the effect of using in-hospital versus long-term mortality on benchmarking. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1925–31. 10.1007/s00134-013-3042-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015;32:88–105. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015339supp1.pdf (116.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015339supp2.pdf (53.6KB, pdf)