The current study shows that armadillo primary visual cortex (V1) neurons share the signature properties of V1 neurons of primates, carnivorans, and rodents. Furthermore, these neurons exhibit a degree of selectivity for stimulus orientation and motion direction similar to that found in primate V1. Our findings in armadillo visual cortex suggest that the functional properties of V1 neurons emerged early in the mammalian lineage, near the time of the divergence of marsupials.

Keywords: primary visual cortex, lateral geniculate nucleus, extracellular recording

Abstract

Orientation selectivity in primary visual cortex (V1) has been proposed to reflect a canonical computation performed by the neocortical circuitry. Although orientation selectivity has been reported in all mammals examined to date, the degree of selectivity and the functional organization of selectivity vary across mammalian clades. The differences in degree of orientation selectivity are large, from reports in marsupials that only a small subset of neurons are selective to studies in carnivores, in which it is rare to find a neuron lacking selectivity. Furthermore, the functional organization in cortex varies in that the primate and carnivore V1 is characterized by an organization in which nearby neurons share orientation preference while other mammals such as rodents and lagomorphs either lack or have only extremely weak clustering. To gain insight into the evolutionary emergence of orientation selectivity, we examined the nine-banded armadillo, a species within the early placental clade Xenarthra. Here we use a combination of neuroimaging, histological, and electrophysiological methods to identify the retinofugal pathways, locate V1, and for the first time examine the functional properties of V1 neurons in the armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) V1. Individual neurons were strongly sensitive to the orientation and often the direction of drifting gratings. We uncovered a wide range of orientation preferences but found a bias for horizontal gratings. The presence of strong orientation selectivity in armadillos suggests that the circuitry responsible for this computation is common to all placental mammals.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The current study shows that armadillo primary visual cortex (V1) neurons share the signature properties of V1 neurons of primates, carnivorans, and rodents. Furthermore, these neurons exhibit a degree of selectivity for stimulus orientation and motion direction similar to that found in primate V1. Our findings in armadillo visual cortex suggest that the functional properties of V1 neurons emerged early in the mammalian lineage, near the time of the divergence of marsupials.

in carnivores and primates, many neurons in the primary visual cortex (V1) are exquisitely selective for feature orientation, exhibiting few or no action potentials unless the stimulus orientation matches a neuron's preference (Hubel and Wiesel 1962; Hubel and Wiesel 1977). Such orientation selectivity lies in contrast to the afferent inputs they receive from relay cells of the visual thalamus. Relay cells exhibit circularly symmetric receptive fields, and their response is only weakly modulated by stimulus orientation (Hubel and Wiesel 1961). V1 orientation selectivity thus represents a computation made by the neocortical circuitry (Carandini and Heeger 2011; Douglas and Martin 1991; Priebe and Ferster 2012). The presence of this simple transformation in V1 and the anatomical uniformity of the neocortical circuitry has made orientation selectivity a model system for studying neural computations in the neocortex (Ferster and Miller 2000).

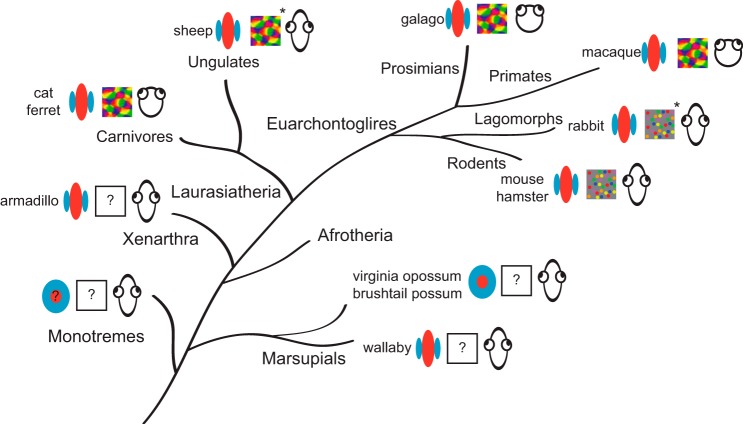

Despite the evident ubiquity of orientation selectivity across mammals, its expression differs. Whereas primates, carnivores, and lagomorphs exhibit extremely high sensitivity to orientation (Murphy and Berman 1979; Ringach et al. 2002; Scholl et al. 2013), selectivity in some marsupials is much weaker (Christensen and Hill 1970; Crewther et al. 1984; Rocha-Miranda et al. 1976). Likewise, the functional organization for orientation selectivity varies across mammals. Neurons are organized by orientation in carnivores and primates such that nearby neurons share orientation preference (Hubel and Wiesel 1962; Hubel and Wiesel 1968). This functional organization is absent in rodents and lagomorphs, and there also appear to be differences in the degree to which the afferent relay cells are selective for orientation (Cleland and Levick 1974; Scholl et al. 2013; see Fig. 5). In the mouse, for example, recent reports demonstrate that the relay cells exhibit some degree of orientation selectivity, though it is unclear how relay cell selectivity is related to that of target cells within V1 (Marshel et al. 2012; Piscopo et al. 2013; Scholl et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2013).

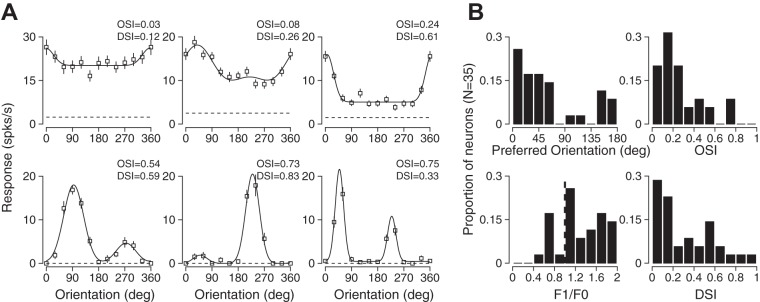

Fig. 5.

Orientation and directional selectivity in single units in armadillo V1. A: representative tuning curves from case 14-16 showing weakly tuned (top left) and highly tuned (bottom right) neurons. B: preferred orientation and orientation selectivity indexes for a population of V1 neurons in armadillo V1. Overall, a bias toward horizontal orientations was evident. A range of orientation selectivity was observed, and values were similar to those in rodent V1 [0.385 ± 0.71 (mean ± SD), median = 0.21]. Most neurons in this population were simple cells (F1/F0 > 1). The directional selectivity among neurons was variable but similar to that observed in rodents (0.31 ± 0.26, median = 0.19; DSI, direction selectivity index).

V1 orientation selectivity has been primarily examined using rodent, carnivore, or primate models. Those species known to exhibit V1 orientation selectivity represent only three of the six major mammalian groups, or superclades. Orientation selectivity has not been described in monotremes, xenarthrans, or afrotherians. Although it is unclear whether Xenarthra or Afrotheria is the earliest placental clade, they both reflect an early offshoot of the placental lineage (Delsuc and Douzery 2008; Morgan et al. 2013; O'Leary et al. 2013; Romiguier et al. 2013; Tarver et al. 2016). Given the diversity in the degree and organization of V1 orientation selectivity, clues to the circuitry responsible for this property, and its universality in mammals, may be revealed using a comparative approach across the mammalian lineage.

Comparative approaches have been useful for identifying phylogenetic distinctions in the functional organization of mammalian nervous systems. For example, the corpus callosum is not present in monotremes and marsupials and is only observed in placental mammals, suggesting that this feature emerged after the divergence of marsupials (Forbes 1882; Gervais 1885; Owen 1837; Smith 1898). Striking differences in the physiological properties and functional organization of sensory and motor areas across the neocortex are also observed between clades, with mostly overlapping sensorimotor regions in monotremes and some marsupials, while placental mammals have almost exclusively nonoverlapping somatosensory and motor cortex (Lende 1963; Magalhães-Castro and Saraiva 1971). Such differences raise the question of whether orientation selectivity is a relatively recently derived characteristic of visual cortex, or shared among mammals. The relatively weak orientation selectivity observed in several marsupials (Christensen and Hill 1970; Crewther et al. 1984; Dooley et al. 2016) suggests that orientation selectivity may be a feature refined after the divergence of placental mammals.

To test this hypothesis, we examined the nature of orientation selectivity in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). Armadillos are members of superorder Xenarthra, an early placental superorder that molecular evidence suggests emerged ~105 million years ago (Delsuc et al. 2004; Delsuc and Douzery 2008; Delsuc et al. 2016; Murphy et al. 2001a; Murphy et al. 2001b). Extant armadillos bear many morphological similarities with fossils of ancestors, and thus examination of their nervous systems may provide an illustration of a relatively early-derived placental form. Previous investigators identified the approximate location of armadillo visual cortex, but neural response characteristics including orientation selectivity were not tested (Royce et al. 1975). We hypothesized that weak orientation selectivity in armadillos, like that observed in most marsupials, would indicate that a neocortical modification resulting in strong orientation selectivity occurred later in the radiation of placental mammalian orders, perhaps in the laurasiatherians. In contrast, strong orientation selectivity would indicate that the circuitry supporting strong orientation selectivity emerged early in placental mammals. We find that armadillo V1 contains neurons with stronger selectivity than that observed in marsupials, and our findings support the idea that orientation selectivity is a common property of placental mammals.

METHODS

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Central Arkansas and followed Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare and U.S. Department of Agriculture guidelines. Three wild-caught adult armadillos (2 male, 1 female; weight 3.9–6.6 kg) were used for the electrophysiological experiments. Three additional animals (1 male, 2 females; weight 4.6–8.4 kg) were used for the neuroimaging experiments.

For electrophysiological experiments, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas (1.5–2.25%) via nose cone, tracheotomized, and intubated. A cannula was inserted into the saphenous vein, and lactated Ringer's solution was delivered intravenously. The animal was placed on a heating pad and positioned in a modified stereotaxic frame. Pulse and respiration rates and temperature were monitored throughout procedures.

The cephalic shield was removed by drilling across the rostral portion and cutting adjacent skin around the perimeter. The underlying fat pad was resected, a craniotomy was performed, and the dura was opened. A cocktail of 1:4 propofol/fentanyl cocktail was delivered intravenously (4–6 ml/h) via syringe pump, isoflurane was withdrawn, and animals were ventilated for the remainder of the procedure. The eyelid was removed, and atropine was applied topically to dilate the pupil.

Extracellular electrodes (1–2 MΩ; Micro Probes, Gaithersburg, MD) were placed into cortex using a motorized drive (MP-285; Sutter Instrument). After the electrode was in place, agarose solution (2–4% in 0.9% saline) was placed over the craniotomy to prevent desiccation and reduce pulsations. V1 was located and mapped by multiunit extracellular recordings with parylene-coated tungsten electrodes (Micro Probes). Initially, mapping using multiunit activity was made to confirm the shift in receptive fields characteristic of primary visual cortex: records made at sites lateral in the cortex contained neurons with central receptive fields, and sites posterior in cortex contained neurons with receptive fields in the lower and temporal portion of the visual field.

Visual stimuli were generated by a Macintosh computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA) using the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard 1997; Pelli 1997) for MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and presented using Sony video monitors (GDM-F520) placed 25 cm from the eye. The video monitor had a noninterlaced refresh rate of 100 Hz and a spatial resolution of 1,024 × 768 pixels, which subtended 40 cm. The video monitors had a mean luminance of 40 cd/cm2. Drifting square wave gratings that subtended 30–40 deg were presented for 2 s, preceded and followed by 250-ms blank (mean luminance) periods. Spontaneous activity was measured with a blank interleaved with drifting grating stimuli and lasting the same duration (2 s). Spatial and temporal frequencies were optimized for each recording but varied between 0.03 and 0.2 cycles/deg. For each record we chose the spatial frequency evoking the strongest response. All stimuli were presented to the contralateral eye and pseudorandomly interleaved.

Spiking responses for each stimulus were cycle-averaged across trials after removing the first cycle. The Fourier transform of mean cycle-average responses was used to calculate the mean (F0) and modulation amplitude (F1) of each cycle-averaged response, after mean spontaneous activity was subtracted. Each neuron analyzed passed a visual response criterion based on an ANOVA between spontaneous firing rate during blank periods and visual stimuli (Gao et al. 2010). Simple and complex cells were separated by computing the modulation ratio (F1/F0) to the preferred monocular stimulus; those neurons with modulation ratios >1 are considered simple (Skottun et al. 1991). Peak responses were defined as the sum of the mean and modulation (F0 + F1). Peak responses (R) across orientations (Θ) were fit with two Gaussian curves of the same variance (σ2) but two different amplitudes (A1 and A2):

| (1) |

where DC is mean offset.

The second Gaussian (A2) was constrained to be 180° phase shifted from the preferred orientation. Gaussian fits were used only for qualitative quantification of orientation tuning curves. Orientation preference was calculated on the basis of the vector average of the peak responses across orientations. Orientation strength was computed using the orientation selectivity index (OSI):

| (2) |

Following electrophysiological mapping, the animals were given a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital via intravenous injection. The animals were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and 4% paraformaldehyde in 10% sucrose. After perfusion, brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for 4–7 days, sectioned on a freezing microtome at 50 μm, processed for Nissl substance and cytochrome oxidase histochemistry, dehydrated, and coverslipped. Sections were photographed at low magnification using a digital camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and a photomicroscope (Wild, Wetzlar, Germany). Photographs were digitally stacked and aligned, and electrode tracks were reconstructed using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Additional tangentially sectioned tissue from three animals used for other experiments was examined for further anatomical determination of the location of V1. Following perfusion as described above, brains were extracted, and the cortical hemispheres were removed from the thalamus. Each hemisphere was gently flattened between glass microscope slides during postfixation, frozen, and sectioned at 30 µm on a freezing microtome. Series of sections were processed for myelin (Gallyas 1979), CO (Wong-Riley 1979), or Nissl substance; dehydrated; and coverslipped. Sections were photographed using a digital camera (Olympus) and photomacroscope (Wild), and virtual stacks of images were assembled using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems). Tissue outlines, blood vessels, and other features were used to align sections, and boundaries of neuroanatomical regions based on staining intensity were established for each section through the cortical depth.

To perform tractography, three animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (3%) via nose cone. A lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital was given via intraperitoneal injection, and the animals were perfused as described above. Following perfusion, the heads were removed and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde until imaging. To minimize susceptibility artifacts in the diffusion images, a custom holder was prepared in the following way. The fixed armadillo head was sealed in a semievacuated airtight polymer bag prepared with a FoodSaver (Jarden, Rye, NY) V4865 vacuum sealer. The sealer's vacuum process was manually halted when the containing bag had all visible air pockets removed, but before a hypobaric pressure was reached. The intention was to remove the air, but not reduce the pressure in the sealed bag. That bag was submerged in a ziplock bag filled with freshly prepared alginate gel (product no. C100-5455; Henry Schein, Melville, NY) to completely submerge the head. All the air pockets were removed, and the bag was sealed and immediately pressed into the radiofrequency (RF) coil to be used for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data acquisition. When pressed into the coil, some excess alginate gel extruded out of the RF coil and into the unused portion of baggie, and the rest created a plug of gel that completely enveloped the tissue and filled the dead volume of the RF coil. Since the alginate gel's magnetic susceptibility is better matched to that of most tissues than air, the susceptibility gradient from tissue to the surrounding space was minimized and offered far better results than obtainable if the dead volume was air gapped. Once the gel cured, the gel held the head firmly in place inside the RF coil.

The MR imaging was performed on a Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) Pharmascan 70/16 7T magnet with a BioSpec AVANCE III console and a BGA-9S gradient coil. The system was controlled using Bruker’s ParaVision software suite version 6.0.1 and product pulse sequences. The RF coil used was a Bruker 60-mm-inside diameter quadrature, fixed tune volume transmit-receive (T/R) coil.

A proton density (PD)-weighted, three-dimensional (3D) high-resolution anatomical reference scan was acquired using a Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement (RARE) sequence with a centric trajectory and the following acquisition parameters: time of repetition (TR) = 6,500 ms, echo spacing (ES) = 11 ms, effective time to echo (effTE) = 11 ms, echo train length (ETL) = 4, field of view (FoV) = 50 × 50 mm2, k-space matrix = 256 × 256, averages = 4, and a receive bandwidth of 39 kHz. No fat saturation was used. There were 45 contiguous axial slices with a thickness of 0.781 mm. The total scan time was 27 min 44 s. The images were reconstructed without interpolation or filtering to a 256 × 256 × 45 voxel volume with an effective spatial resolution of 195 × 195 × 781 μm3.

The diffusion imaging was performed using a 2D segmented, double spin-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with fat saturation and large spacing (>1 ms) between the crushers and refocusing pulses. This specialized technique was used to maximize signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing the considerable residual susceptibility effects and eddy current artifacts. The scan acquisition parameters used were as follows: TR = 7,000 ms, TE = 50 ms, FoV = 50 × 50 mm2, k-space matrix = 64 × 64, segments = 4, averages = 8, and a receive bandwidth = 208.33 kHz. Standard fat saturation was used. With 45 contiguous axial slices, each 0.781 mm thick (the same slice prescription used for the PD-weighted scan), isotropic spatial resolution was effectively achieved. Matched-bandwidth excitation and refocusing RF pulses were used to eliminate the possibility of signal loss due to partial slice refocusing. The B0 in the full volume of the brain was iteratively shimmed using a 3D ellipsoid-localized high-order shimming routine. There were 48 diffusion-weighted directions used, chosen with a surface hemispherical isocharge distance maximization algorithm. The target b-value was 1,000 s/mm2, but the actual b-values achieved depended on the specific direction and ranged from 853 to 1,167 s/mm2. Two b0 (T2-weighted) scans were acquired. The diffusion-weighting gradient length (δ) was 3.37 ms, and the slice crusher length/strength was 1.5 ms/9 G/cm. The scan time was 3 h 6 min 40 s. It had been previously determined that the B0 drift on this particular magnet degraded the EPI trajectory corrections to unacceptable levels after approximately this length of time. To achieve a higher number of averages without compromising image quality, the preceding scan was queued four times, resulting in a total scan time of 12 h 26 min 40 s. At the start of each of the three following subscans, the resonant frequency and trajectory correction prescans were rerun, and all other parameters were held constant. The 4 scans were reconstructed with no interpolation or filtering to 50 complete 64 × 64 × 45 voxel volumes and subsequently averaged in MATLAB for subsequent tractographic analysis. In effect, this postacquisition averaging procedure increased the actual number of averages for the described scans from 8 to 32.

The averaged images were processed with DSI Studio (http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org, build July 10, 2016) to generate a diffusion tensor and associated metrics. Fiber tracking was performed using DSI Studio using a generalized version of the deterministic tracking algorithm that uses quantitative anisotropy as the termination index (Yeh et al. 2013).

RESULTS

Armadillo visual pathway.

As a first step to providing a functional characterization of the armadillo V1 we employed anatomical techniques to identify the visual pathway, from the eyes, through the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) to V1. Tracking the fibers leading to visual cortex and staining for markers associated with primary sensory cortex allowed us to accurately identify the position of primary visual cortex in the armadillo.

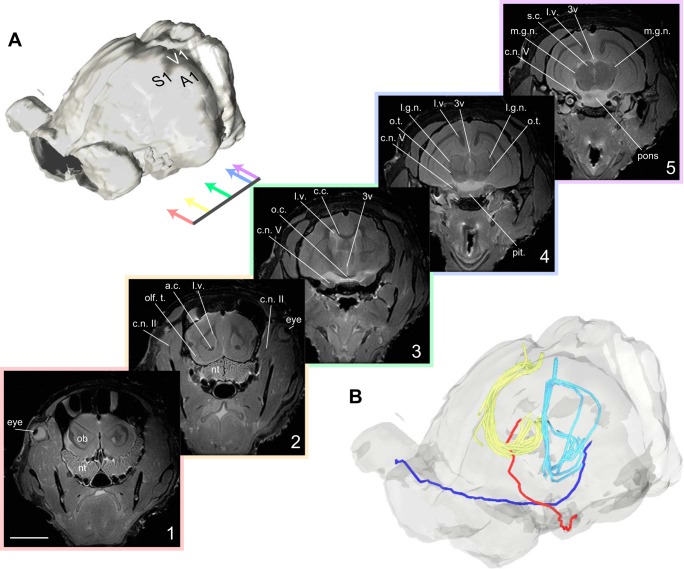

We first used a magnetic resonance imaging system (Bruker 7T; Ettlingen, Germany) to perform T2-weighted scans (Fig. 1A). These anatomical scans were performed at a resolution of 0.195 × 0.195 × 0.78 mm, providing a gross perspective on the visual pathway in the armadillo. Armadillo eyes are laterally positioned, and the retinal projections follow a trajectory common among vertebrates. The optic nerves project medially and ventrally from the back of each eye, and these projections meet at the optic chiasm. From the optic chiasm, the optic tract projects to central structures including the LGN (Fig. 1B, red and blue projections).

Fig. 1.

Structural MR and tractographic images of armadillo visual pathways. A: surface rendering of armadillo brain and eyes based on structural MRI data. Cerebellum is to top right, and eyes are to the left. Colored arrows indicate location of coronal sections shown in series. 1–5: rostrocaudal series of structural MR images, showing optic nerve descending from eyes, moving medially and ventrally to optic chiasm. Optic tract then extends caudally and continues dorsally along thalamus to reach LGN. Scale bar is 1 cm. B: reconstructions of optic nerve, tract, and optic radiations in the armadillo. Red and dark blue lines indicate left and right projection from retina, respectively, crossing in the optic chiasm, and continuing to contralateral LGN. Light blue and yellow lines indicate optic radiations from LGN to V1, derived from tractography seeds in the LGN (yellow) or primary visual cortex. Abbreviations used: 3v, third ventricle; A1, primary auditory cortex; a.c., anterior commissure; c.c., corpus callosum; c.n. II, optic nerve; c.n. V, trigeminal nerve; l.g.n., lateral geniculate nucleus; l.v., lateral ventricle; m.g.n., medial geniculate nucleus; nt, nasal turbinates; ob, olfactory bulb; o.c., optic chiasm; olf. t., olfactory tubercle; o.t., optic tract; pit., pituitary gland; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; s.c., superior colliculus; V1, primary visual cortex.

Because we are interested in identifying the pathway from the LGN to V1, we next employed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and tractographic processing to track the axonal fibers between these structures. DTI is an MRI technique that maps the diffusion rates of endogenous water in tissues that may contain directionally organized structures; for instance, along fiber bundles. Since water has a higher apparent diffusion constant parallel to fiber projections relative to perpendicular to fiber projections, DTI and the following tractography allow us to identify putative optic radiation between these structures. To identify V1, we seeded the LGN bilaterally and examined the resulting projections using diffusion tractography techniques (see methods). As is common in other mammals the resulting projection, the optic radiation, follows a curved path, moving around the ventricles and the hippocampi and terminating in the caudal portion of the cerebral cortex. We considered this termination location to be the putative site of V1 in the armadillo (Fig. 1B, yellow lines).

This fiber tracking based on DTI relies upon directionally oriented diffusion coupled with an initial seed location that defines the start of the projections. These tracks are therefore susceptible to noise associated with choosing a particular seed location. To determine the reliability of our estimate of the optic radiation, we therefore decided to employ a complementary technique: we used the putative V1 site as the seed location and used the same algorithm to find the tracts that connect to the LGN. In this case we found a similar fiber pathway that leads around the hippocampus and terminates in the location we have previously identified as the LGN (Fig. 1B, cyan lines). Because these two seed points resulted in similar projection patterns, we are confident that we have properly identified the optic radiation and the location of armadillo V1.

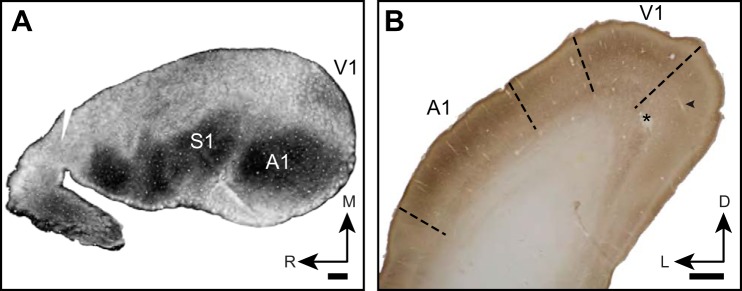

Cytochrome oxidase histochemistry and myelin staining have been used as a marker in a variety of species for identifying primary sensory areas based on patterns of intense staining (Gallyas 1979; Horton and Hocking 1997; Kaas and Collins 2001; Krubitzer et al. 1995; Sarko and Reep 2007; Wong and Kaas 2009b; Wong-Riley 1979; Wong-Riley and Welt 1980). In tangentially sectioned tissue, armadillo V1, like primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and primary auditory cortex (A1), is readily identified as a zone of increased density staining, ~3 × 4 mm (Fig. 2A). In coronally sectioned tissue, we observed regions of high-density CO stain in the expected locations of armadillo primary auditory, visual, and somatosensory cortex described by Royce et al. (1975). Although we did not explore the entirety of this neuroanatomically identified zone with electrophysiology, in our neuroanatomical analysis, V1 appears as a dorsomedial region that is relatively densely stained in CO, particularly in layer IV. In our recordings made before histological staining, neurons located in this region were visually responsive to flashes of light and moving grating stimuli. Reconstruction of the electrode tracks in the histological material confirms that our recordings traversed all layers of V1 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Anatomical location and identification of armadillo V1 using myelin and CO staining. A: flattened hemisphere sectioned tangential to cortical surface and stained for myelin. Note dense staining in primary somatosensory and auditory areas, while V1 is moderately stained. R, rostral; M, medial. B: photomicrograph of coronal section through caudal end of armadillo brain stained for cytochrome oxidase histochemistry. Electrode tract (arrowhead) and lesion (*) from recordings in this study are shown. L, lateral; D, dorsal. A1 and V1 are both identified by a densely stained layer IV. Relatively lightly stained region between A1 and V1 was not explored in this study but is expected to correspond to bimodal zone, in which responses to auditory and visual stimuli can be evoked. Scale bar is 1 mm.

We identified the neuroanatomical location of primary visual cortex using both MRI and histological techniques. We should note that because neuroimaging was not performed on the same cases used for histology, it was not possible to unequivocally align the locations identified by the two measurements. Nonetheless, both of these techniques identify the same region of cerebral cortex that appears to receive fiber projections emanating from the LGN, and that has a high degree of cytochrome oxidase staining, which corresponds directly with the electrophysiologically identified V1.

Functional properties of armadillo V1.

We performed extracellular recordings in V1 of three anesthetized armadillos (see methods). Access to the primary visual cortex was made possible by removing the cephalic shield and skull and performing a durotomy. Single tungsten microelectrodes were lowered into the armadillo cortex in regions similar to those identified from our anatomical measurements. We initially mapped receptive field locations of visually responsive neurons with multiunit recordings. Each site was quickly hand mapped to determine the retinotopic organization of visual cortex. As is common in primates, carnivorans, and rodents we found a consistent retinotopic map in which receptive fields moved into the upper field for more caudal locations and moved toward central visual space of armadillo vision for lateral recording sites.

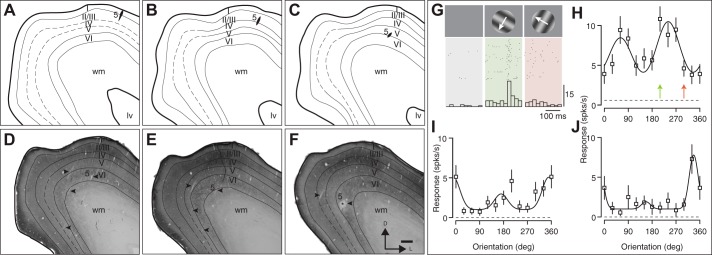

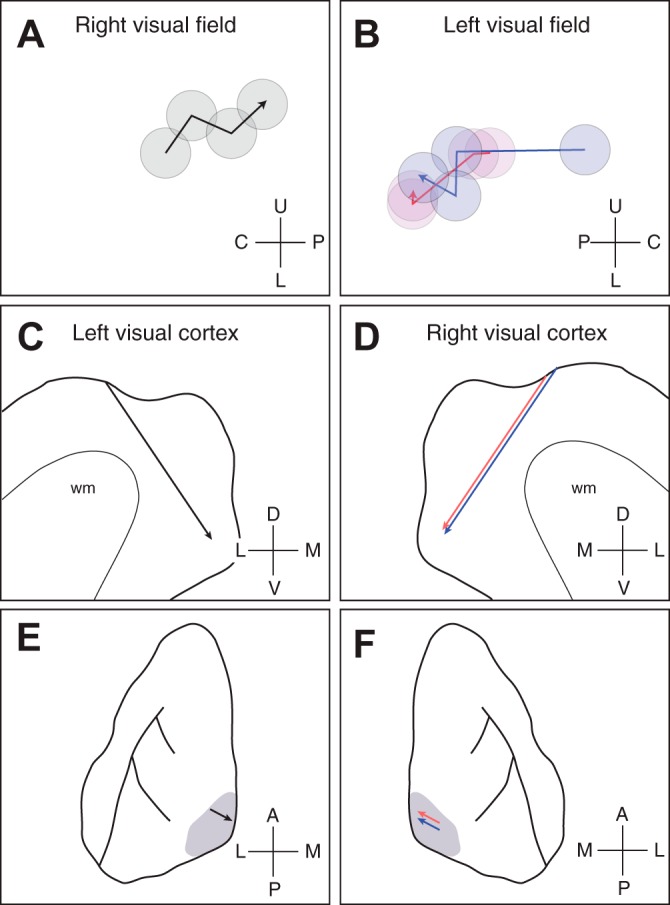

Once V1 was identified based on retinotopy we measured the orientation and direction selectivity of isolated single units. We made penetrations extending across cortical layers recording from individual neurons as we moved through the cortex. After the experiments were completed the tissue was fixed, and we used histology to reconstruct our penetrations through visual cortex (Figs. 3, A–F, and 4, A–F, penetration 5). As with our hand mapping using multiunit responses, there were consistent shifts in receptive field location as we moved our electrode down through the dorsal portion of visual cortex through the medial bank. Receptive fields became increasingly peripheral as the electrode progressed down the medial bank (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Retinotopic progression in relation to location in visual cortex. A: receptive field locations for single units recorded along electrode penetrations for case 04-16. The receptive field centers for four neurons are plotted for a single penetration, where the deepest neuron is indicated by the arrowhead. B: as in A, but for two penetrations in case 04-13. The two penetrations are indicated by red and blue symbols. Coordinates used: U, upper; L, lower; C, central; P, periphery. C and D: a sagittal drawing of the armadillo neocortex depicting the electrode trajectory for the two cases. Lines indicate the penetrations along the sagittal plane. Coordinates used: D, dorsal; V, ventral; L, lateral; M, medial. E and F: a dorsal perspective of the armadillo neocortex, where the visual cortex is indicated by the gray shading. The locations of the penetrations are indicated by the arrows. In both cases, penetrations were angled toward the medial bank, as indicated by the arrows. Coordinates used: A, anterior; P, posterior; L, lateral; M, medial.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed electrode tracks through V1 in case 14-14. A–F: drawings of sections stained for cytochrome oxidase histochemistry, spaced 100 µm apart, ordered rostrocaudally. Electrode tract for one penetration is indicated with number 5 and arrowhead (* in F indicates lesion at end of tract for penetration 5; additional arrowheads indicate other electrode tracts). In all cases, recordings were made through the cortical depths, and lesions were placed to identify the end of the penetration. Here, lv, lateral ventricle; wm, white matter. D–F include representative stained sections. Cortical layer IV was typically densely stained in V1, although in some sections, distinguishing layers III, IV, and V was difficult. G–J: data recording during penetration 5. G shows raster and histograms of the response to orientations for the orientation-selective neuron in H. Two additional neurons recorded in penetration 5 are shown in I and J. Here, spks/s, spikes per second.

Neurons in armadillo V1 are sensitive to stimulus orientation. We measured the degree of sensitivity by systematically varying the orientation of moving gratings and recording the single-unit responses (Fig. 4G). As can be seen in the example responses of three different neurons from the same penetration, armadillo V1 neurons have a low baseline level of activity, measured as the peak spike rate (see methods), and increase their responses selectively to drifting gratings (Fig. 4, G–J). Many of these neurons modulated their response to drifting gratings in a pattern consistent with simple cell activity (Fig. 4G). Not only were many neurons sensitive to the orientation of drifting gratings, but a subset of neurons were also direction selective. As in other mammals, drifting grating stimuli were effective at driving spiking responses. On average, neurons responded to their preferred stimulus with an elevation of spike rate by 13.9 ± 11.7 spikes/s (mean ± SD; median = 13.3 spikes/s), whereas their background firing rate was very low (0.89 ± 1.17 spikes/s, median = 0.38 spikes/s).

Our sample population included neurons with a wide range of preferences and selectivity for orientation. For example, we did find some neurons with only weak sensitivity to orientation (Fig. 5A, top left), while others were extremely sensitive (Fig. 5A, bottom right). In conjunction with this diversity of sensitivity we also found that orientation preference varied substantially, such that almost all orientations were represented. Across the population we did find a trend for neurons to prefer horizontal orientations (near 0 or 180 deg) more than vertical orientations (90 deg). The distribution of orientation preference was significantly different from what could be accounted for by chance (χ2, degrees of freedom = 7, P < 0.001). We quantified the degree of orientation selectivity in individual neurons by using OSI, which is defined as 1 minus the circular variance of the responses to all orientations. As shown in the example cells in Fig. 5A, this value was diverse across the population but had mean and median values similar to those found in mouse V1 (0.385 ± 0.71, median = 0.21). Most of the neurons recorded in our sample population would be classified as simple cells by the distribution of the modulation index (Fig. 5B, bottom left). Finally, the degree of direction selectivity varied across neurons and had mean and median values that are close to those found in mouse V1 (0.31 ± 0.26, median = 0.19).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to gain insight into the evolution of functional selectivity in primary visual cortex in mammals by examining the anatomical and functional properties of the early visual system of the nine-banded armadillo. The armadillo is a member of an early-derived placental clade, Xenarthra, considered to have diverged after marsupials but before laurasiatherians (e.g., cats) and euarchontoglires, the clade that includes rodents and primates (Delsuc and Douzery 2008; Tarver et al. 2016). Functional properties of V1 neurons such as orientation selectivity and direction selectivity have been studied extensively in rodents, cats, and nonhuman primates and are thought to reflect canonical computations made by the mammalian neocortical circuitry (Carandini and Heeger 2011; Douglas and Martin 1991; Priebe and Ferster 2012). Despite this idea, it is also clear that the functional properties and architecture of this area differ across mammalian species (Scholl et al. 2013; Van Hooser 2007). Here, we used a combination of neuroimaging, histological, and electrophysiological methods to identify the retinofugal pathways, locate V1, and examine the functional properties of V1 neurons in the armadillo.

By integrating structural MR images, DTI, and tractography, we traced the central visual pathways of the armadillo from the eye, through the LGN, to V1. We found that the retinofugal pathway in armadillos is similar to that of other mammals, and we identified the size and location of V1 histologically by the presence of intense CO staining. With this location in hand we made single-unit recordings in vivo and found that armadillo V1 neurons share the signature properties of V1 neurons of rodents, carnivores, and primates. Specifically, we found that as in other mammals, the visual cortex is organized in a retinotopic fashion, and V1 neurons are highly responsive to visual stimulation and exhibit levels of orientation and direction selectivity similar to that found in primate V1. The presence of orientation selectivity to the degree observed in the armadillo stands in contrast to the reports based on arboreal marsupials such as brushtail possums, in which only weak selectivity has been reported. Our data indicate the functional properties observed in V1 neurons in species representing more recently derived groups may have emerged early in mammalian evolution, near the time of the divergence between marsupial and placental mammals.

The functional selectivity of neurons in the mammalian neocortex is remarkably distinct from the three-layer paleocortex that processes visual information in reptiles. Whereas mammalian visual cortex is functionally organized by retinotopy and, in many cases, orientation selectivity, such topography is absent in the turtle dorsal cortex (DCx), the correlate of V1 in reptiles (Mazurskaya 1973). Those neurons do not respond to visual stimuli positioned at specific retinotopic locations and instead respond in a complex fashion to visual stimulation that often extends across visual hemifield. This difference may reflect the structure of the thalamic afferents, which in reptiles make extensive en passant connections across DCx but in mammals innervate restricted zones of visual cortex (Heller and Ulinski 1987). The presence of retinotopic maps and orientation selectivity in mammalian cortex thus reflects a distinct processing strategy from the reptilian forebears (Fournier et al. 2015).

Anatomical organization of armadillo visual pathways.

We find that the retinofugal pathway of armadillos is similar to that observed in most other mammals [for review, see Jones (1985)]. The optic nerves descend ventrally from the laterally placed eyes and bend caudally and medially to meet in the optic chiasm directly beneath the hypothalamus. The optic tract continues caudally and laterally, moving dorsally along the thalamus before entering the LGN. Although the LGN in armadillos is proportionately not as large as that in carnivores and primates, dorsal and ventral subdivisions, separated by an intrageniculate leaflet, are evident on the basis of cytoarchitecture (Papez 1932). This organization is similar to that observed in many other mammals, including marsupials and most rodents (Crish et al. 2006; Kahn and Krubitzer 2002).

The visually responsive cortex in armadillos is located at the caudalmost dorsolateral portion of the hemisphere, extending ~5–7 mm laterally (Royce et al. 1975). This area shows dense CO staining in layer IV as well as a moderate to intense staining for myelin, which together support that this region corresponds to primary visual cortex (Fig. 2). This pattern of staining is common in all three major branches of mammals. The monotreme homolog to eutherian V1, Vc, likewise shows dense staining for CO in layer IV and is darkly myelinated (Krubitzer 1998). Marsupial V1 also has dense CO staining in layer IV and dense myelin staining throughout (Ashwell et al. 2005; Rosa et al. 1999; Wong and Kaas 2009a). In felines, a common laurasiatherian model, CO staining clearly demarcates the extent of V1 (Murphy et al. 1995; Wong-Riley 1979). Finally, in euarchontoglires, V1 has been identified using CO and myelin staining in many species, in particular primates and rodents (Balaram et al. 2014; Campi and Krubitzer 2010; Carroll and Wong-Riley 1984; Wong and Kaas 2009b). The extent of this differential staining varies across mammals, which may reflect the dependence of each species on vision. For example, squirrels, which are highly visual rodents, have a relatively large and clearly defined V1 (Campi and Krubitzer 2010; Krubitzer et al. 2011; Wong and Kaas 2008). Our findings in the armadillo indicate that dense CO and myelin staining in V1 is conserved across mammals.

Functional selectivity of armadillo primary visual cortex.

Our study is the first to measure the selectivity of individual visual neurons in the xenarthran neocortex. Among single units in armadillo V1, we observed a relatively wide range of orientation and direction selectivity, similar to that observed in rodents and primates. Although no quantitative functional studies of the visual cortex have previously been conducted in a xenarthran species, visual responses to full-field illumination have been described in the cortex of sloths and armadillos in a similar location to the region that we identified as V1 here (Magalhães-Castro et al. 1975; Meulders et al. 1966; Royce et al. 1975). The armadillo has a number of notable characteristics that may have implications regarding the functional properties of its visual system. The armadillo is typically a nocturnal, burrowing animal and thus is not believed to rely heavily on vision. Like the other xenarthrans, on the basis of gross neuroanatomical data, armadillos are considered to be olfactory specialists (Pirlot 1980; Reep et al. 2007; Royce et al. 1975; Shuddemagen 1907). Anecdotally, armadillos are reported as having poor vision, and this may be because humans often interact with armadillos in daylight or when using bright lights. Like sloths (and putatively anteaters), armadillos possess mutations of the genes necessary for the phototransduction with cone photoreceptors (Emerling and Springer 2015). The armadillo retina contains exclusively rod photoreceptors, which are saturated in bright illumination, and thus armadillos are indeed most likely visually impaired during interactions with humans (St. Jules 1984). Other species known to be monochromats, such as the owl monkey, also have strong orientation selectivity arranged in columns in V1 (Xu et al. 2004).

We observed a relatively wide range of orientation preferences, with a statistically significant bias toward horizontal orientations in our sample population of 35 neurons. A horizontal bias in V1 neurons is commonly found in many mammals with terrestrial lifestyles and has been described in rodents, lagomorphs, felines, and primates [mouse, Dräger (1975) and Girman et al. (1999); hamster, Tiao and Blakemore (1976); rabbit, Bousfield (1977) and Murphy and Berman (1979); cat, Bauer and Jordan (1993); monkey, De Valois et al. (1982); human, Campbell et al. (1966) and Leehey et al. (1975)]. Orientation biases for cardinal planes have been reported in many species, from carnivores to primates. Orientation biases have been described as variable between individuals within a species and, to some extent, can be shifted via experience in adult animals (Chapman and Bonhoeffer 1998; Yoshida et al. 2012).

Emergence of the circuitry for cortical orientation selectivity.

An important impetus for our study is the difference in the degree of V1 orientation selectivity reported in marsupial and placental animals. Armadillos exhibit degrees of orientation selectivity similar to other placental mammals, suggesting that orientation selectivity emerged in early mammals and may have been lost in the marsupial cohort (Fig. 6). It is important to note, however, that the reported difference between marsupial and placental mammals is based on reports in marsupials from the brushtail possum (Crewther et al. 1984) and the Virginia opossum (Christensen and Hill 1970), big-eared opossum (Rocha-Miranda et al. 1973; Rocha-Miranda et al. 1976), and the short-tailed opossum (Dooley et al. 2016). Taken together, these studies report that only a minority of V1 neurons are orientation selective, though they do describe characteristics common to cortical neurons in placental mammals such as high degrees of binocularity reflecting a convergence of right and left eye information and a columnar organization for ocular dominance.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic relationships and orientation selectivity in mammalian clades. Increased complexity in functional organization (e.g., columnar organization of orientation selectivity) is observed in V1 of relatively recently derived mammals. Symbols indicate whether there is strong orientation selectivity, whether there is a map of orientation selectivity, and the degree to which the eyes are forward facing. Orientation tuning has not been described in monotremes, but orientation selectivity has been measured in some marsupial species and exists in all placental mammals that have been examined. Data from the current study indicate that strong orientation selectivity is present in Xenarthra, a relatively early-derived placental clade, suggesting that strong orientation tuning may have become prevalent during the placental radiation. Cat, Grinvald et al. (1986) and Hubel and Wiesel (1962); ferret, Chapman et al. (1996); sheep, Clarke et al. (1976); galago, Xu et al. (2005); macaque, Blasdel and Salama (1986); rabbit, Murphy and Berman (1979); mouse, Kondo et al. (2016); hamster, Tiao and Blakemore (1976); Virginia opossum, Christensen and Hill (1970); brushtail possum, Crewther et al. (1984); wallaby, Ibbotson and Mark (2003). *Data obtained solely with electrophysiological recordings.

One interpretation of our findings, along with these marsupial reports, is that orientation selectivity emerges after the split between marsupials and placentals. We must note that the marsupial superclade is a large group, however, and this reported lack of orientation selectivity observed in opossums and possums may not characterize all marsupials. Indeed, another study on marsupial orientation selectivity in the wallaby demonstrated a much higher degree of orientation selectivity (Ibbotson and Mark 2003). It is unclear to what extent low orientation selectivity is characteristic among marsupials, but these data suggest that a wide range of orientation selectivity is present in members of the same superclade. Variability in orientation selectivity is also evident among placental mammals, with V1 neurons in carnivores exhibiting higher orientation selectivity than primates, or varying across cortical laminae.

An alternative interpretation of our results is that the presence of strong orientation tuning in the wallabies and all placentals studied is an example of evolutionary convergence. Mammalian nervous systems are all governed by similar physical constraints [e.g., types of sensory information available (e.g., photons or sound waves)], and thus when faced with similar behavioral and ecological demands, similar peripheral morphology and neural organization may result. For example, the functional organization of somatosensory cortical regions (e.g., area 2) involved in reaching and grasping behaviors is strikingly similar in New World (capuchin) and Old World (rhesus macaque) primate species that utilize precision grips to manipulate objects in their environment (Padberg et al. 2007). It is possible that the functional properties of neurons in mammalian visual cortex are governed by similarly conserved mechanisms, resulting in similarities between highly visual marsupials and placental mammals.

Orientation and direction selectivity have been ascribed to processing within cortex, but it has become increasingly clear that subcortical afferents may also contribute to these properties. Subsets of retinal ganglion cells in vertebrates, including rodents, lagomorphs, pigeons, and turtles, respond selectively to both orientation and direction of motion (Baden et al. 2016; Barlow and Levick 1965; Levick 1967; Maturana and Frenk 1963; Sanes and Masland 2015; Sernagor and Grzywacz 1995; Taylor et al. 2000). Furthermore, a circuit has been identified that links direction-selective neurons in the retina, LGN, and visual cortex suggesting that selectivity in V1 could be inherited from earlier stations in rodents (Cruz-Martín et al. 2014). In contrast to the rodent, it appears that orientation selectivity can arise by cortical mechanisms in carnivores and primates, which have few orientation-selective afferent inputs (Cleland and Levick 1974; Scholl et al. 2013). Although it is clear that some subcortical selectivity could contribute to cortical selectivity in mammals, there are good reasons to suspect that interactions within V1 are also essential. Neurons in visual cortex are also binocular because of the convergence of ipsilateral and contralateral afferent streams. The orientation preference of binocular neurons is generally the same for stimulation in either eye (Bridge and Cumming 2001; Ferster 1981; Hubel and Wiesel 1962; Rose et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2010). For this to emerge from selective afferent neurons, those afferents would need to have matched selectivity emerging only during the developmental critical period. There may be multiple overlapping circuits leading to orientation selectivity in visual cortex; as yet the degree to which individual species rely on subcortical and cortical interactions for orientation selectivity is unclear.

Orientation selectivity has been observed in the V1 of every mammal that has been examined, and it has therefore been widely considered to be a basic computational feature of neocortical circuitry. One hypothesis for its emergence is that the oriented receptive fields could efficiently encode natural scenes (Olshausen and Field 1996). Natural scene statistics are known to scale across frequencies, so even in low-acuity animals such as the mouse and armadillo such statistics should result in oriented filters (Ruderman and Bialek 1994). Yet the organization and degree of orientation selectivity vary across mammals (Fig. 6). The factors that contribute to this diversity are still obscure but include the size of V1, the degree of visual field overlap between the eyes, and the cohort of retinal ganglion cell classes that provide input to the cortical visual pathway.

Our data from a xenarthran species suggest that strong orientation selectivity is likely to be present in all placental clades. It is likely that orientation selectivity emerged early in mammalian evolution, perhaps near the stem therian. It is important to recognize that this is a distinct pattern of selectivity from that observed in our reptile ancestors, which lack orientation selectivity in the visual portion of their forebrain. The circuitry and conditions necessary for the emergence of orientation selectivity in mammals remain unknown, but light may be shed on the necessary conditions by examining the diversity of selectivity among marsupials. Among marsupials, strong orientation selectivity is described only in wallabies, a marsupial with forward facing eyes, a distinct feature relative to the opossum and possum. Perhaps a common circuit underlies orientation selectivity across mammals, which either is modified in individual species or is differentially expressed as a function of differences in input. Even when we observe differences in functional selectivity, it is often the case that different patterns of selectivity may be accounted for by a single organization rule (Kaschube et al. 2010). Revealing the factors influencing orientation selectivity will therefore give us insight into the general transformation that the neocortex, a unique structure of mammals, is performing.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Eye Institute Grant 025102, National Science Foundation Division of Integrative Organismal Systems Grant 1257891, and a grant from the Human Frontiers Science Program.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.S., N.J.P., and J.P. conceived and designed research; B.S., J.R., J.J.L., N.J.P., and J.P. performed experiments; B.S., J.J.L., N.J.P., and J.P. analyzed data; B.S., J.J.L., N.J.P., and J.P. interpreted results of experiments; B.S., N.J.P., and J.P. prepared figures; B.S., N.J.P., and J.P. drafted manuscript; B.S., J.R., J.J.L., N.J.P., and J.P. edited and revised manuscript; B.S., J.R., J.J.L., N.J.P., and J.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jessica Hanover and Amrita Puri for helpful discussions. We also appreciate the assistance of Dr. Alexander Huk for interpreting the MRI scans and Dr. Thomas Cabantac for veterinary support.

REFERENCES

- Ashwell KW, Zhang LL, Marotte LR. Cyto- and chemoarchitecture of the cortex of the tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii): areal organization. Brain Behav Evol 66: 114–136, 2005. doi: 10.1159/000086230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden T, Berens P, Franke K, Román Rosón M, Bethge M, Euler T. The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature 529: 345–350, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nature16468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaram P, Young NA, Kaas JH. Histological features of layers and sublayers in cortical visual areas V1 and V2 of chimpanzees, macaque monkeys, and humans. Eye Brain 2014, Suppl 1: 5–18, 2014. doi: 10.2147/EB.S51814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow HB, Levick WR. The mechanism of directionally selective units in rabbit's retina. J Physiol 178: 477–504, 1965. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Jordan W. Different anisotropies for texture and grating stimuli in the visual map of cat striate cortex. Vision Res 33: 1447–1450, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90138-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasdel GG, Salama G. Voltage-sensitive dyes reveal a modular organization in monkey striate cortex. Nature 321: 579–585, 1986. doi: 10.1038/321579a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield JD. Columnar organisation and the visual cortex of the rabbit. Brain Res 136: 154–158, 1977. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis 10: 433–436, 1997. doi: 10.1163/156856897X00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge H, Cumming BG. Responses of macaque V1 neurons to binocular orientation differences. J Neurosci 21: 7293–7302, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FW, Kulikowski JJ, Levinson J. The effect of orientation on the visual resolution of gratings. J Physiol 187: 427–436, 1966. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campi KL, Krubitzer L. Comparative studies of diurnal and nocturnal rodents: differences in lifestyle result in alterations in cortical field size and number. J Comp Neurol 518: 4491–4512, 2010. doi: 10.1002/cne.22466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandini M, Heeger DJ. Normalization as a canonical neural computation. Nat Rev Neurosci 13: 51–62, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrn3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll EW, Wong-Riley MT. Quantitative light and electron microscopic analysis of cytochrome oxidase-rich zones in the striate cortex of the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 222: 1–17, 1984. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Bonhoeffer T. Overrepresentation of horizontal and vertical orientation preferences in developing ferret area 17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 2609–2614, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Stryker MP, Bonhoeffer T. Development of orientation preference maps in ferret primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 16: 6443–6453, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JL, Hill RM. Response properties of single cells of a marsupial visual cortex. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 47: 547–556, 1970. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PG, Donaldson IM, Whitteridge D. Binocular visual mechanisms in cortical areas I and II of the sheep. J Physiol 256: 509–526, 1976. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland BG, Levick WR. Properties of rarely encountered types of ganglion cells in the cat’s retina and an overall classification. J Physiol 240: 457–492, 1974. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crewther DP, Crewther SG, Sanderson KJ. Primary visual cortex in the brushtailed possum: receptive field properties and corticocortical connections. Brain Behav Evol 24: 184–197, 1984. doi: 10.1159/000121316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crish SD, Dengler-Crish CM, Catania KC. Central visual system of the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber). Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 288: 205–212, 2006. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Martín A, El-Danaf RN, Osakada F, Sriram B, Dhande OS, Nguyen PL, Callaway EM, Ghosh A, Huberman AD. A dedicated circuit links direction-selective retinal ganglion cells to the primary visual cortex. Nature 507: 358–361, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delsuc F, Douzery EJP. Recent advances and future prospects in xenarthan molecular phylogenetics. In: The Biology of the Xenarthra, edited by Vizcaino SF and Loughry WJ. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008, p. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Delsuc F, Gibb GC, Kuch M, Billet G, Hautier L, Southon J, Rouillard JM, Fernicola JC, Vizcaíno SF, MacPhee RD, Poinar HN. The phylogenetic affinities of the extinct glyptodonts. Curr Biol 26: R155–R156, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delsuc F, Vizcaíno SF, Douzery EJ. Influence of Tertiary paleoenvironmental changes on the diversification of South American mammals: a relaxed molecular clock study within xenarthrans. BMC Evol Biol 4: 11, 2004. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Valois RL, Albrecht DG, Thorell LG. Spatial frequency selectivity of cells in macaque visual cortex. Vision Res 22: 545–559, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley JC, Donaldson MS, Krubitzer LA. Cortical plasticity following stripe rearing in the marsupial Monodelphis domestica: neural response properties of V1. J Neurophysiol 117: 566–581. doi: 10.1152/jn.00431.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KAC. A functional microcircuit for cat visual cortex. J Physiol 440: 735–769, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger UC. Receptive fields of single cells and topography in mouse visual cortex. J Comp Neurol 160: 269–290, 1975. doi: 10.1002/cne.901600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerling CA, Springer MS. Genomic evidence for rod monochromacy in sloths and armadillos suggests early subterranean history for Xenarthra. Proc Biol Sci 282: 20142192, 2015. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster D. A comparison of binocular depth mechanisms in areas 17 and 18 of the cat visual cortex. J Physiol 311: 623–655, 1981. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster D, Miller KD. Neural mechanisms of orientation selectivity in the visual cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 23: 441–471, 2000. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes WA. On some points in the anatomy of the Great Anteater (Myrmecophaga jubata). J Zool 50: 287–302, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J, Müller CM, Laurent G. Looking for the roots of cortical sensory computation in three-layered cortices. Curr Opin Neurobiol 31: 119–126, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallyas F. Silver staining of myelin by means of physical development. Neurol Res 1: 203–209, 1979. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1979.11739553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao E, DeAngelis GC, Burkhalter A. Parallel input channels to mouse primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 30: 5912–5926, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6456-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais MP. Histoire naturelle des mammiferes. Paris: Chez Blaise, 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Girman SV, Sauvé Y, Lund RD. Receptive field properties of single neurons in rat primary visual cortex. J Neurophysiol 82: 301–311, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Lieke E, Frostig RD, Gilbert CD, Wiesel TN. Functional architecture of cortex revealed by optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Nature 324: 361–364, 1986. doi: 10.1038/324361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller SB, Ulinski PS. Morphology of geniculocortical axons in turtles of the genera Pseudemys and Chrysemys. Anat Embryol (Berl) 175: 505–515, 1987. doi: 10.1007/BF00309685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JC, Hocking DR. Myelin patterns in V1 and V2 of normal and monocularly enucleated monkeys. Cereb Cortex 7: 166–177, 1997. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Integrative action in the cat's lateral geniculate body. J Physiol 155: 385–398, 1961. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat's visual cortex. J Physiol 160: 106–154, 1962. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. J Physiol 195: 215–243, 1968. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Ferrier lecture. Functional architecture of macaque visual cortex. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 198: 1–59, 1977. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson MR, Mark RF. Orientation and spatiotemporal tuning of cells in the primary visual cortex of an Australian marsupial, the wallaby Macropus eugenii. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 189: 115–123, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The Thalamus. New York: Springer, 1985. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1749-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Collins CE. The organization of sensory cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 498–504, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn DM, Krubitzer L. Retinofugal projections in the short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica). J Comp Neurol 447: 114–127, 2002. doi: 10.1002/cne.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschube M, Schnabel M, Löwel S, Coppola DM, White LE, Wolf F. Universality in the evolution of orientation columns in the visual cortex. Science 330: 1113–1116, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1194869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Yoshida T, Ohki K. Mixed functional microarchitectures for orientation selectivity in the mouse primary visual cortex. Nat Commun 7: 13210, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L. What can monotremes tell us about brain evolution? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 353: 1127–1146, 1998. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L, Campi KL, Cooke DF. All rodents are not the same: a modern synthesis of cortical organization. Brain Behav Evol 78: 51–93, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000327320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L, Manger P, Pettigrew J, Calford M. Organization of somatosensory cortex in monotremes: in search of the prototypical plan. J Comp Neurol 351: 261–306, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leehey SC, Moskowitz-Cook A, Brill S, Held R. Orientational anisotropy in infant vision. Science 190: 900–902, 1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1188370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lende RA. Cerebral cortex: a sensorimotor amalgam in the marsupiala. Science 141: 730–732, 1963. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3582.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levick WR. Receptive fields and trigger features of ganglion cells in the visual streak of the rabbits retina. J Physiol 188: 285–307, 1967. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães-Castro B, Saraiva PE. Sensory and motor representation in the cerebral cortex of the marsupial Didelphis azarae azarae. Brain Res 34: 291–299, 1971. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães-Castro HH, Saraiva PES, Magalhães-Castro B. Identification of corticotectal cells of the visual cortex of cats by means of horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res 83: 474–479, 1975. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshel JH, Kaye AP, Nauhaus I, Callaway EM. Anterior-posterior direction opponency in the superficial mouse lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron 76: 713–720, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maturana HR, Frenk S. Directional movement and horizontal edge detectors in the pigeon retina. Science 142: 977–979, 1963. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3594.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurskaya PZ. Organization of receptive fields in the forebrain of Emys orbicularis. Neurosci Behav Physiol 6: 311–318, 1973. doi: 10.1007/BF01182671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulders M, Gybels J, Bergmans J, Gerebtzoff MA, Goffart M. Sensory projections of somatic, auditory and visual origin to the cerebral cortex of the sloth Choloepus hoffmanni Peters). J Comp Neurol 126: 535–546, 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CC, Foster PG, Webb AE, Pisani D, McInerney JO, O'Connell MJ. Heterogeneous models place the root of the placental mammal phylogeny. Mol Biol Evol 30: 2145–2156, 2013. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy EH, Berman N. The rabbit and the cat: a comparison of some features of response properties of single cells in the primary visual cortex. J Comp Neurol 188: 401–427, 1979. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KM, Jones DG, Van Sluyters RC. Cytochrome-oxidase blobs in cat primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 15: 4196–4208, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, Johnson WE, Zhang YP, Ryder OA, O’Brien SJ. Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals. Nature 409: 614–618, 2001a. doi: 10.1038/35054550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, O’Brien SJ, Madsen O, Scally M, Douady CJ, Teeling E, Ryder OA, Stanhope MJ, de Jong WW, Springer MS. Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science 294: 2348–2351, 2001b. doi: 10.1126/science.1067179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary MA, Bloch JI, Flynn JJ, Gaudin TJ, Giallombardo A, Giannini NP, Goldberg SL, Kraatz BP, Luo ZX, Meng J, Ni X, Novacek MJ, Perini FA, Randall ZS, Rougier GW, Sargis EJ, Silcox MT, Simmons NB, Spaulding M, Velazco PM, Weksler M, Wible JR, Cirranello AL. The placental mammal ancestor and the post-K-Pg radiation of placentals. Science 339: 662–667, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1229237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural images. Nature 381: 607–609, 1996. doi: 10.1038/381607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R. On the structure of the brain in marsupial animals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 127: 87–96, 1837. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1837.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padberg J, Franca JG, Cooke DF, Soares JG, Rosa MG, Fiorani M Jr, Gattass R, Krubitzer L. Parallel evolution of cortical areas involved in skilled hand use. J Neurosci 27: 10106–10115, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2632-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papez JW. The thalamic nuclei of the nine-banded armadillo (Tatusia novemcincta). J Comp Neurol 56: 49–103, 1932. doi: 10.1002/cne.900560107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis 10: 437–442, 1997. doi: 10.1163/156856897X00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirlot P. Quantitative composition and histological features of the brain in two South American edentates. J Hirnforsch 21: 1–9, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscopo DM, El-Danaf RN, Huberman AD, Niell CM. Diverse visual features encoded in mouse lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci 33: 4642–4656, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5187-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe NJ, Ferster D. Mechanisms of neuronal computation in mammalian visual cortex. Neuron 75: 194–208, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reep RL, Finlay BL, Darlington RB. The limbic system in mammalian brain evolution. Brain Behav Evol 70: 57–70, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000101491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringach DL, Shapley RM, Hawken MJ. Orientation selectivity in macaque V1: diversity and laminar dependence. J Neurosci 22: 5639–5651, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Miranda CE, Bombardieri RA Jr, de Monasterio FM, Linden R. Receptive fields in the visual cortex of the opossum. Brain Res 63: 362–367, 1973. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Miranda CE, Linden R, Volchan E, Lent R, Bombar-Dieri RA Jr. Receptive field properties of single units in the opossum striate cortex. Brain Res 104: 197–219, 1976. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romiguier J, Ranwez V, Delsuc F, Galtier N, Douzery EJ. Less is more in mammalian phylogenomics: AT-rich genes minimize tree conflicts and unravel the root of placental mammals. Mol Biol Evol 30: 2134–2144, 2013. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa MG, Krubitzer LA, Molnár Z, Nelson JE. Organization of visual cortex in the northern quoll, Dasyurus hallucatus: evidence for a homologue of the second visual area in marsupials. Eur J Neurosci 11: 907–915, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T, Jaepel J, Hübener M, Bonhoeffer T. Cell-specific restoration of stimulus preference after monocular deprivation in the visual cortex. Science 352: 1319–1322, 2016. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royce GJ, Martin GF, Dom RM. Functional localization and cortical architecture in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus mexicanus). J Comp Neurol 164: 495–521, 1975. doi: 10.1002/cne.901640408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman DL, Bialek W. Statistics of natural images: scaling in the woods. Phys Rev Lett 73: 814–817, 1994. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JR, Masland RH. The types of retinal ganglion cells: current status and implications for neuronal classification. Annu Rev Neurosci 38: 221–246, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarko DK, Reep RL. Somatosensory areas of manatee cerebral cortex: histochemical characterization and functional implications. Brain Behav Evol 69: 20–36, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000095028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl B, Tan AY, Corey J, Priebe NJ. Emergence of orientation selectivity in the mammalian visual pathway. J Neurosci 33: 10616–10624, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0404-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E, Grzywacz NM. Emergence of complex receptive field properties of ganglion cells in the developing turtle retina. J Neurophysiol 73: 1355–1364, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuddemagen LC. On the anatomy of the central nervous system of the nine-banded armadillo (Tatu novemcinctum Linn.). Biol Bull 12: 285–302, 1907. doi: 10.2307/1535817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skottun BC, De Valois RL, Grosof DH, Movshon JA, Albrecht DG, Bonds AB. Classifying simple and complex cells on the basis of response modulation. Vision Res 31: 1079–1086, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GE. The brain in the edentata. Trans Linn Soc Lond 7: 277–394, 1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1899.tb00479.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- St. Jules RS. The Retina of the Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) (PhD thesis). College Station, TX: Texas A&M Univ., 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tarver JE, Dos Reis M, Mirarab S, Moran RJ, Parker S, O’Reilly JE, King BL, O’Connell MJ, Asher RJ, Warnow T, Peterson KJ, Donoghue PC, Pisani D. The interrelationships of placental mammals and the limits of phylogenetic inference. Genome Biol Evol 8: 330–344, 2016. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR, He S, Levick WR, Vaney DI. Dendritic computation of direction selectivity by retinal ganglion cells. Science 289: 2347–2350, 2000. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiao YC, Blakemore C. Functional organization in the visual cortex of the golden hamster. J Comp Neurol 168: 459–481, 1976. doi: 10.1002/cne.901680403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooser SD. Similarity and diversity in visual cortex: is there a unifying theory of cortical computation? Neuroscientist 13: 639–656, 2007. doi: 10.1177/1073858407306597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang BS, Sarnaik R, Cang J. Critical period plasticity matches binocular orientation preference in the visual cortex. Neuron 65: 246–256, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of neocortex in the gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). Anat Rec (Hoboken) 291: 1301–1333, 2008. doi: 10.1002/ar.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. An architectonic study of the neocortex of the short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica). Brain Behav Evol 73: 206–228, 2009a. doi: 10.1159/000225381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of neocortex in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri). Anat Rec (Hoboken) 292: 994–1027, 2009b. doi: 10.1002/ar.20916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley M. Changes in the visual system of monocularly sutured or enucleated cats demonstrable with cytochrome oxidase histochemistry. Brain Res 171: 11–28, 1979. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MT, Welt C. Histochemical changes in cytochrome oxidase of cortical barrels after vibrissal removal in neonatal and adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77: 2333–2337, 1980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Bosking W, Sáry G, Stefansic J, Shima D, Casagrande V. Functional organization of visual cortex in the owl monkey. J Neurosci 24: 6237–6247, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1144-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Bosking WH, White LE, Fitzpatrick D, Casagrande VA. Functional organization of visual cortex in the prosimian bush baby revealed by optical imaging of intrinsic signals. J Neurophysiol 94: 2748–2762, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.00354.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FC, Verstynen TD, Wang Y, Fernández-Miranda JC, Tseng WY. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS One 8: e80713, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080713. [Erratum, PLoS One 9: Jan. 2014. doi:]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Ozawa K, Tanaka S. Sensitivity profile for orientation selectivity in the visual cortex of goggle-reared mice. PLoS One 7: e40630, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Chen H, Liu X, Cang J. Orientation-selective responses in the mouse lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci 33: 12751–12763, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0095-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]