Plants have evolved novel microtubule (MT) arrays to regulate cell division and cell expansion. How these MT arrangements are managed has been a question of long-standing interest to plant cell biologists. Do plants have unique ways of regulating MTs or have they co-opted mechanisms that are familiar to us from studies in animal and fungal cells? This Update focuses on the MT plus-end-tracking proteins (+TIPs), a relatively recent addition to the repertoire of MT regulatory proteins. Although the study of +TIPs in plants is just beginning, the emerging data indicate that some, but not all, +TIPs are conserved in the green lineage and that plants have at least one family of +TIPs that is unique. Plants, it seems, organize their MT arrays via a combination of novel and phylogenetically conserved mechanisms.

MT ARRAYS IN THE GREEN PLANT LINEAGE

Although the structure of an individual MT is highly conserved in all eukaryotes, higher order MT arrays vary widely, from spindles to flagella, and during a single cell cycle MTs rearrange in a precise and predictable sequence that is characteristic of the phylogenetic lineage. In many eukaryotic lineages, cells contain centrosomes that serve as MT-organizing centers. During interphase, MTs emanating from the centrosome extend outward to the cell cortex, forming radial structures that function in intracellular transport and cytoplasmic organization. In mitosis, MTs reassemble into a spindle that mechanically segregates chromosomes to daughter nuclei and participates in division plane specification.

MT arrays are organized quite differently in plants (Wasteneys, 2002). Higher plant cells lack centrosomes and the associated radial array. Instead, interphase MTs are found in the cortex of the cell, where they are arranged parallel to one another and generally transverse to the direction of cell expansion. As cells near mitosis, the cortical array rearranges into a narrow band that encircles the nucleus and portends the future division plane. This preprophase band (PPB) is transient, disassembling as the spindle forms. At telophase, yet another MT array, the phragmoplast, is assembled between daughter nuclei. The phragmoplast is a cylindrical array composed of two opposing sets of parallel MTs that transport Golgi vesicles to the midzone, where they fuse to form the nascent cell plate. With time, the phragmoplast and growing cell plate expand outward to the cortex, where fusion occurs at the site previously marked by the PPB. After cytokinesis, cortical MTs reappear and become organized into parallel arrays. The cortical interphase array, PPB, and phragmoplast are unique to the green lineage, and there is much interest in understanding their structure, function, and regulation. The observation that plant cells transiently form several clearly discernable MT arrays during each cell cycle highlights the need to have mechanisms to rapidly assemble, organize, and disassemble MTs.

+TIPs AND MT ORGANIZATION

MT assembly and organization are regulated by the inherent dynamics of the tubule and by an array of regulatory proteins termed MAPs (MT-associated proteins). The inherent dynamics, or dynamic instability, of MTs is governed by their ends, which exhibit rapid transitions between growing and shrinking states (Desai and Mitchison, 1997). The minus end is generally capped and stabilized by a complex of nucleating proteins, and MT dynamics are therefore primarily governed by the properties at the plus end, which elongates and shortens as it explores the cytoplasm. Plus ends of growing MTs contain GTP caps resulting from the addition of tubulin dimers with bound GTP. The GTP cap is thought to regulate dynamics in the following way: MTs containing a GTP cap preferentially elongate, whereas hydrolysis of GTP to GDP by the inherent GTPase activity of tubulin induces a conformational change that favors shortening. Sometimes MTs exhibit dynamics at both ends. Recent in vivo observations in plant cells indicate that treadmilling, defined as the loss of tubulin dimers from the minus end coupled with addition at the plus end, causes MT migration along the cell cortex and contributes to changes in array organization (Shaw et al., 2003).

MT dynamics are also regulated by MAPs. Many MAPs bind to the sides of MTs and stabilize, destabilize, or bundle the tubules. In 1999, a new family of MAPs that preferentially accumulate at the plus ends of MTs was discovered by observing the movements of CYTOPLASMIC LINKER PROTEIN 170 (CLIP-170)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) in living mammalian cells. The fusion protein formed a comet that tracked the plus ends of growing MTs (Perez et al., 1999), and this property is now the defining characteristic of a family of proteins called +TIPs. The number of +TIPs, many structurally unrelated, identified in fungi and metazoans is growing rapidly, and intense investigation is elucidating their functions in cellular physiology. +TIP association alters the dynamic parameters of the plus end, usually resulting in longer, more dynamic MTs. Long, dynamic MTs are ideal for searching the cellular milieu, and when the plus ends encounter appropriate receptors, they are captured and stabilized. +TIPs mediate MT capture at the kinetochore of chromosomes and at localized cortical sites, including cell ends in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), a cortical crescent in Drosophila melanogaster neuroblasts, the bud in dividing budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and the leading edge in migrating cells. This local MT capture orients polarized growth, spindle position, division plane specification, and directional migration. Thus, +TIPs regulate both MT dynamics and the structure/polarity of the MT array. Several excellent reviews concerning +TIPs in non-plant cells have recently appeared (Hayles and Nurse, 2001; Schuyler and Pellman, 2001a; Carvalho et al., 2003; Galjart and Perez, 2003; Howard and Hyman, 2003; Martin and Chang, 2003; Mimori-Kiyosue and Tsukita, 2003; Morris, 2003; Xiang, 2003; Gundersen et al., 2004), and the reader is directed to these for more detailed discussions. The study of +TIPs in plants is just beginning and, following a brief consideration of mechanisms of plus-end accumulation, this Update focuses on identifying potential +TIPs in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome and discusses initial research results.

PATHWAYS OF PLUS-END ACCUMULATION

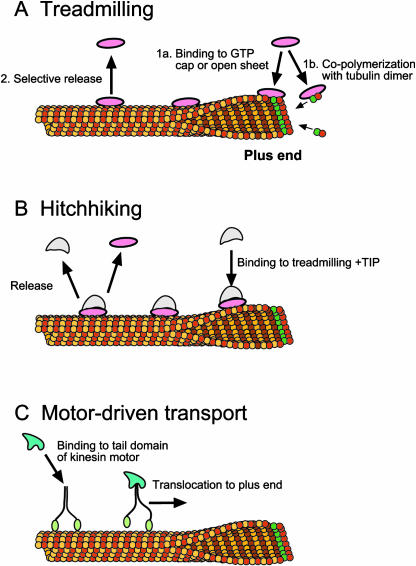

Although detailed mechanisms have not been worked out, there are three general pathways by which +TIPs are thought to accumulate at plus ends: treadmilling, hitchhiking, and motor-driven transport (Fig. 1; Carvalho et al., 2003). Treadmilling and hitchhiking involve transient binding to the plus end, whereas motor-driven transport translocates proteins along the MT to the plus end (Galjart and Perez, 2003). +TIPs that treadmill preferentially bind to the plus end of a growing MT and are released a short time later as the plus end grows past. Treadmilling +TIPs do not translocate through the cytoplasm with the plus end but instead bind and release at the same point in space (Perez et al., 1999). Thus, the comet that appears to surf the plus end when GFP-tagged proteins are visualized in living cells is an illusion caused by the +TIPs hopping on and off the end as it rockets past. Several factors can contribute to preferential end localization of treadmilling +TIPs, including copolymerization with tubulin dimers, high-affinity binding to MT ends, and selective release from the tubule walls (Fig. 1A; Schuyler and Pellman, 2001a; Carvalho et al., 2003). High-affinity binding to a MT plus end is facilitated by its unique chemical and structural properties (Tirnauer et al., 2002). Rather than a cylinder, the plus end of a growing MT is an open sheet (for review, see Carvalho et al., 2003). The edges of the sheet are brought together, and the cylinder zips up as the MT grows. Treadmilling +TIPs may bind preferentially to the curved sheet conformation or to sites on the internal surface of the tubule exposed only at the plus end. The GTP cap at the plus end may also facilitate binding. Selective release behind the elongating tip may be due to lower affinity of the treadmilling protein for the closed cylinder and/or chemical modification of the tubule (e.g. GTP hydrolysis) or the +TIP (e.g. phosphorylation; Schroer, 2001).

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms for plus-end binding. Green circles at the plus end of the MT denote α-tubulin bound to GTP. See text for details.

Plus-end tracking can also be accomplished by hitchhiking. Hitchhiking +TIPs bind the MT plus end indirectly through a treadmilling protein and, like treadmilling proteins, appear to surf the plus end but are not transported through the cytoplasm with the growing MT (Carvalho et al., 2003). Some hitchhiking proteins participate in MT capture by serving as bridging proteins between MTs and receptor proteins at a capture site (Gundersen et al., 2004). In budding yeast, +TIPs provide bridges between MT and actin cytoskeletons at specific sites and at specific times during the cell cycle (Heil-Chapdelaine et al., 1999).

In motor-driven transport, the +TIP is cargo on a kinesin that walks toward the plus end (Fig. 1C). This mechanism of plus-end accumulation differs from hitchhiking and treadmilling in several regards. First, motors allow proteins loaded onto MTs to be translocated through the cytoplasm and unloaded at target sites. Second, +TIPs using motor-driven transport are found along the MT length, whereas treadmilling/hitchhiking proteins localize preferentially at plus ends with little or no protein associated with MT walls. Third, motors with their +TIP cargos stay attached to shrinking MTs (Galjart and Perez, 2003). By contrast, treadmilling/hitchhiking proteins fall off depolymerizing MTs, resulting in loss of the characteristic plus-end comet. As a MT shifts to the shrinking state, the GTP cap is lost and protofilaments splay apart, which may prevent +TIP binding (Carvalho et al., 2003).

Recent evidence indicates that plus-end accumulation may be considerably more complicated. A +TIP may associate with plus ends using two or even all three mechanisms, and different organisms may use distinct pathways to localize the same +TIP family member (Carvalho et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003; Xiang, 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). Furthermore, many of the +TIPs interact with one another leading to speculation that there may be rafts of interacting proteins surfing on the plus end of MTs, where they regulate MT dynamics and capture (Coquelle et al., 2002; Galjart and Perez, 2003).

+TIPs IN PLANTS

What is the nature of the plus ends of plant MTs? One might expect many of the proteins found in fungal and metazoan cells to be conserved in plants; kinetochore MTs, for instance, capture chromosomes in all eukaryotic cells. On the other hand, the phragmoplast, PPB, and cortical array are unique to plant cells, and their regulation may require plant-specific +TIPs. An increase in MT dynamics has been measured during PPB formation (Dhonukshe and Gadella, 2003; Vos et al., 2004), and it has been proposed that this increase in dynamics may facilitate MT search and capture in the PPB (Vos et al., 2004). PPB formation is therefore an excellent candidate for regulation by conserved, or novel, +TIPs.

To date, data documenting plus-end tracking have been published for two plant proteins, phylogenetically conserved EB1, (Chan et al., 2003; Mathur et al., 2003) and SPIRAL1 (SPR1), a +TIP with family members found only in plant sequence databases (Nakajima et al., 2004; Sedbrook et al., 2004). In addition, preliminary data indicate that the kinesin ATK5 is also a novel type of +TIP (C. Ambrose and R. Cyr, personal communication). To assess the extent to which +TIPs are conserved in plants, we performed BLAST searches of the Arabidopsis protein database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using sequences from +TIPs and their binding partners in fungi and metazoans. This analysis indicates that some +TIPs are conserved in plants (Table I), while others appear to be absent.

Table I.

+TIPs and interacting proteins found in plants

| Protein Family

|

Sequence(s) Used for Comparison

|

Sequence(s) Found in Arabidopsis Genome

|

Evidence

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLASTP

|

Protein Domain Predictions

|

References

|

||||

| Score | E-Value | |||||

| EB1 | NP_036457 (human EB1) | NP_190353 (AtEB1a; At3g47960) | 154 | 3 × 10−36 | Calponin homology and EB1 | Chan et al. (2003); Gardiner and Marc (2003); Mathur et al. (2003); Meagher and Fechheimer (2003) |

| NP_201056 (AtEB1b; At5g62500) | 180 | 5 × 10−44 | ||||

| NP_201528 (AtEB1c; At5g67270) | 176 | 9 × 10−43 | ||||

| MOE1 | NP_594625 (fission yeast Moe1p) | NP_193830 (At4g20980) | 320 | 1 × 10−85 | EIF-3_zeta | Gardiner and Marc (2003) |

| NP_199245 (At5g44320) | 312 | 2 × 10−83 | ||||

| MAP215/DIS1 | AAG34914 (Xenopus XMAP215) | NP_565811 (MOR1/GEM1; At2g35630) | 590 | 1 × 10−166 | TOG, tau, and HEAT repeats | Tournebize et al. (2000); Whittington et al. (2001); Meagher and Fechheimer (2003); Gard et al. (2004) |

| FORMIN (Diaphanous) | – | 21 sequences | – | – | FH1 and FH2 | Deeks et al. (2002) |

| MYOSIN | – | 17 sequences | – | – | Motor, coiled-coil and putative calmodulin binding | Reddy and Day (2001a) |

| CLASP | BAA94248 (Drosophila orbit) | NP_849997 (At2g20190) | 179 | 7 × 10−43 | Mast at C terminus | Gardiner and Marc (2003) |

| LIS1 (NUDF; Pac1) | CAD55133 (D. discoideum Lis1) | NP_201533 (At5g67320) | 124 | 8 × 10−27 | LisH and WD-40 repeats | – |

| NP_177513 (At1g73720) | 119 | 2 × 10−25 | ||||

| NP_565749 (At2g32700) | 109 | 2 × 10−22 | ||||

| KINESIN | ATK5 MCAKs Kip3p | NP_192428 (At4g05190) | – | – | Reddy and Day (2001b) | |

| NP_566534 (At3g16060) | – | – | ||||

| NP_850598 (At3g16630) | – | – | ||||

| NP_173290 (At1g18550) | – | – | ||||

| NP_190534 (At3g49650) | – | – | ||||

| NP_197779 (At5g23910) | – | – | ||||

| SPR1 | At2g03680 | NP_173960 (At1g26360) | – | – | Conserved sequences in amino- and carboxy-terminal regions | Nakajima et al. (2004); Sedbrook et al. (2004) |

| NP_974110 (At1g69230) | ||||||

| NP_566166 (At3g02180) | ||||||

| NP_567685 (At4g234960) | ||||||

| NP_197064 (At5g15600) | ||||||

Potential Arabidopsis families were identified either from published reports or from database searches at NCBI. For sequences identified by database searches, designation as a putative +TIP or interacting protein was based on the presence of conserved protein domain structures (as predicted from the Conserved Domain Database [Marchler-Bauer et al., 2003]) as well as BLASTP scores and E-values. –, Not done.

END BINDING 1

END BINDING 1 (EB1) proteins were the first plant molecules identified as +TIPs (Chan et al., 2003; Mathur et al., 2003). EB1 proteins play important roles in diverse organisms, ranging from human to fungal cells. By regulating MT dynamics and mediating attachment of MT ends to subcellular sites, they are instrumental in assembling and aligning the mitotic spindle, guiding polarized cell growth, and facilitating chromosome capture by spindles (for review, see Schuyler and Pellman, 2001a; Carvalho et al., 2003). The Arabidopsis genome contains three EB1 genes, designated AtEB1a, AtEB1b, and AtEB1c; each predicted protein contains conserved domains and shares significant sequence similarity with EB1 proteins from other organisms (Table I). All three AtEB1 proteins are predicted to contain a conserved amino-terminal calponin homology domain required for MT binding as well as a conserved coiled-coil domain (EB1 domain) thought to mediate protein-protein interactions (Bu and Su, 2003).

GFP fusions with two of the Arabidopsis proteins, AtEB1a and AtEB1b, label the faster-growing ends of MTs in a characteristic comet shape in living cells (Chan et al., 2003; Mathur et al., 2003). However, both fusion proteins also localize to additional sites. AtEB1a-GFP is found at the slower-growing minus ends of cortical MTs, where it appears to mark MT nucleation sites in the cortical array (Chan et al., 2003; Wick, 2003). EB1 proteins are found at MT nucleation sites (e.g. spindle poles and centrosomes) in several organisms (Berrueta et al., 1998; Morrison et al., 1998; Tirnauer et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2002; Tirnauer et al., 2002; Straube et al., 2003), but it is not yet clear whether they anchor minus ends (Askham et al., 2002; Louie et al., 2004) or serve as an EB1 reservoir for binding the plus ends of recently nucleated MTs (Rehberg and Graf, 2002). Curiously, the GFP:AtEB1b fusion has a subcellular localization pattern that is different from that of the AtEB1a:GFP fusion. In addition to MTs, GFP:AtEB1b also labels internal membranes, including endoplasmic reticulum and membranes that surround chloroplasts, mitochondria, and nuclei (Mathur et al., 2003).

Both AtEB1 fusions also label along the lengths of MTs, a pattern that has been reported in cells overexpressing EB1 (Schwartz et al., 1997; Tirnauer et al., 1999; Mimori-Kiyosue et al., 2000; Lignon et al., 2003). In the Arabidopsis studies, the AtEB1 sequences were placed under the regulation of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, which is known to drive high levels of gene expression (Sanders et al., 1987), and it is therefore possible that the observed localization patterns do not accurately reflect endogenous AtEB1. Unpublished data supports this concern; when AtEB1b:GFP expression is driven by either the Hsp18.2 heat shock promoter or 1.5 kb of AtEB1b upstream sequences, labeling is restricted to comet-shaped structures at fast-growing MT ends (R. Dixit and R. Cyr, personal communication). These constructs label growing, but not shrinking, MTs consistent with the treadmilling mechanism of end accumulation found for non-plant EB1s. Furthermore, we have analyzed AtEB1 localization using a polyclonal antibody directed against AtEB1c, and have observed labeling only at MT ends in the cortical MT array (S.R. Bisgrove, unpublished data). Further imaging studies are needed to clarify AtEB1 localization patterns, and mutant analyses are needed to address the functions of plant EB1 proteins in regulating MT dynamics and mediating MT search and capture.

EB1-Associated Proteins

The Arabidopsis database contains two sequences that may represent EB1-binding partners of the Moe1p (MTs overextended) family (Table I). In fission yeast, Moe1p binds the EB1 family member Mal3p, and genetic and physical interaction studies indicate that Mal3p and Moe1p may act as a complex that regulates MT dynamics (Chen et al., 2000). Moe1p can itself influence MT dynamics; as the name suggests, MTs in moe1 mutants are unusually long (Chen et al., 2000). Recent evidence indicates that a putative AtMOE1 interacts with AtEB1 in yeast two-hybrid assays (R. Dixit and R. Cyr, personal communication), but how it might regulate MTs in plant cells is unknown.

MAP215/DIS1 is a phylogenetically conserved family of proteins that includes XMAP215 in frogs, DIS1 in fission yeast, TOG in mammals, and MOR1/GEM1 in plants. These proteins regulate MT dynamics (for review, see Hussey et al., 2002; Gard et al., 2004), and emerging data suggest that they interact with EB1. Dictyostelium discoideum EB1 colocalizes with DdCP224 (the MAP215/DIS1 family member), and the two proteins can be coimmunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts (Rehberg and Graf, 2002). Furthermore, Bim1p (budding yeast EB1) interacts with Stu2p (the MAP215/DIS1 family member) in yeast two-hybrid screens (Chen et al., 1998). In the Arabidopsis genome, the MICROTUBULE ORGANIZATION 1 (MOR1) gene codes for a MAP215/DIS1 family member (Table I; Tournebize et al., 2000; Whittington et al., 2001). The MOR1 protein colocalizes with MTs in the preprophase band, spindle, phragmoplast, and cortical arrays (Twell et al., 2002), and mutant analyses suggest that MOR1 does regulate MTs in the cortical and cytokinetic arrays. Temperature-sensitive mutations in the amino-terminal region of the MOR1 protein cause disruption of cortical MTs in plants grown at the restrictive temperature (Whittington et al., 2001), and truncations that are predicted, but not yet proven, to remove carboxy-terminal regions of the protein disrupt cytokinesis during pollen development and are sporophytically lethal (Twell et al., 2002). The possibility that MOR1 and EB1 interact with each other in plant cells is currently under investigation.

Additional proteins known to interact with EB1 include the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein from humans and Kar9p from budding yeast (Su et al., 1995; Korinek et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2000; Mimori-Kiyosue et al., 2000). Although these proteins appear to be unrelated to each other at the amino acid level, it has been proposed that they are functionally equivalent since both proteins link EB1 at MT plus ends to the cell cortex (Bienz, 2001; Nakamura et al., 2001). Our searches of the Arabidopsis database do not identify any proteins that might be related to either APC or Kar9p based on sequence similarities. The TANGLED1 (TAN1) protein of maize (Zea mays) can bind MTs, and sequence comparisons suggest that it may be distantly related to vertebrate APC (Smith et al., 2001), but functional data linking TAN1 and EB1 are lacking. Biochemical and/or yeast two-hybrid assays for proteins that interact with AtEB1 are needed to identify plant proteins that might be functionally related to APC or Kar9p.

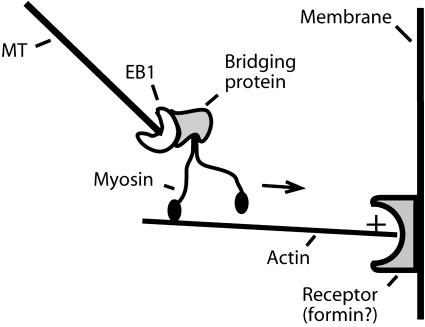

Formins are a family of conserved proteins thought to provide a link between MTs and actin, perhaps via EB1. At the cell cortex, formins nucleate actin filaments and regulate the rate of polymerization by capping the fast-growing barbed ends (Evangelista et al., 2003). Formins also participate in MT processes, although their role is less clear. In mammalian cells, the formin mDia stabilizes MTs (Palazzo et al., 2001) and may interact with EB1 and APC (Gundersen et al., 2004). During spindle alignment in budding yeast, actin filaments nucleated by the formin Bni1p are thought to provide tracks for the transport of MTs bearing Bim1p and Kar9p at their plus ends to the cortex by a myosin motor, Myo2p (Beach et al., 1999; Yin et al., 2000). The Arabidopsis genome contains 21 putative formin sequences and 17 myosin sequences (Table I; Castrillon and Wasserman, 1994; Banno and Chua, 2000; Cvrckova, 2000; Deeks et al., 2002; Reddy and Day, 2001a). (See Preuss et al. [2004; this issue] for a discussion of plant myosins.) Since EB1, myosins, and formins are all present in the Arabidopsis genome, it is plausible that plants have a conserved pathway for delivering MT ends to cortical receptors (see Fig. 2 below).

Figure 2.

Hypothetical model for delivery of a plant MT to a cellular receptor at a specific site (e.g. PPB, phragmoplast, root hair tip) along actin filaments, based on models from yeast and fibroblasts (Gundersen et al., 2004). EB1 binds a bridging protein associated with myosin, which translocates toward the barbed (plus) end of the actin filament. Genome analysis identifies EB1, myosins, and formins in Arabidopsis.

CLIPs

As the first protein shown to track the plus ends of MTs, CLIP-170 is the prototype +TIP (Perez et al., 1999). CLIP family members have now been identified in diverse phyla where they regulate MT dynamics and appear to link MTs to intracellular sites (Pierre et al., 1992; Dujardin et al., 1998; Brunner and Nurse, 2000; Lin et al., 2001). Although the overall sequence similarity is not high among CLIPs, the proteins all share conserved domains. The MT-binding region, located at the amino terminus, consists of one or more CAP-Gly domains; it is followed by a central coiled-coil and one or more putative metal-binding motifs at the carboxy terminus (Brunner and Nurse, 2000; Goodson et al., 2003). BLAST searches, using D. melanogaster CLIP-190 and the Arabidopsis protein database at NCBI, identify several proteins with E-values ≤9 × 10−15. However, none of these proteins appear to be bona fide CLIPs since they all lack the conserved CAP-Gly MT-binding domain. Curiously, plants may well lack CLIPs. However, when mammalian CLIP-170 is expressed in plant cells, it tracks MT plus ends, indicating that the pathway that regulates the binding of CLIP-170 to MTs is conserved in plants (Dhonukshe and Gadella, 2003).

CLIP-Associated Proteins

CLIP-associated proteins, or CLASPs, bind both CLIPs and MTs; they colocalize with CLIPs at MT plus ends, where they have a stabilizing effect (Akhmanova et al., 2001). CLASPs link spindle MTs to kinetochores and also promote polarized growth at the leading edge of migrating fibroblasts (Akhmanova et al., 2001; Maiato et al., 2003). BLAST searches identify a single Arabidopsis protein (Table I; Gardiner and Marc, 2003) that is related to MAST/ORBIT, the D. melanogaster CLASP family member. Although it is unknown whether this putative AtCLASP is in fact a +TIP, its presence is intriguing since there are no clear CLIP family members in the Arabidopsis genome.

In animals and yeast, CLIP-170 may function through interacting with the dynactin complex and cytoplasmic dynein. Dynactin is a multisubunit complex that activates the minus-end-directed MT motor, cytoplasmic dynein, also a protein complex. Dynactin also binds to MT plus ends, and mutational and overexpression studies suggest that it is targeted to plus ends via p150Glued and CLIP-170 (Goodson et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, obvious cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin components are absent (Lawrence et al., 2001).

LISSENCEPHALY 1

Humans carrying mutations in the LISSENCEPHALY 1 (LIS1) gene have a severe developmental brain deformity known as lissencephaly (“smooth brain”) type 1 that is thought to reflect a defect in neuronal migration (Reiner, 2000). LIS1 proteins are conserved across large evolutionary distances and have been shown to form comet-like structures at the dynamic plus ends of both growing and shrinking MTs (Han et al., 2001; Coquelle et al., 2002; Lee, et al., 2003). They mediate dynein activity and regulate MT dynamics by mechanisms that are not well understood (Xiang et al., 1995; Lei and Warrior, 2000; Liu, et al., 2000; Dawe et al., 2001; Han et al., 2001; Tai et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003). LIS1 family members contain an N-terminal coiled-coil LisH domain that is important for dimerization (Cahana et al., 2001), followed by several WD repeats that mediate protein-protein interactions (Reiner, 2000).

The Arabidopsis database contains several predicted proteins with the same domain structures as LIS1 family members, and three of them score well when compared with D. discoideum LIS1 sequences (Table I). Fourteen additional Arabidopsis genes are predicted to encode proteins with a LisH domain but no WD repeats. One of these, At3g55000, is the TONNEAU1b (TON1) gene. Curiously, ton1 mutants have disorganized cortical MTs and cannot make PPBs (Traas et al., 1995). Whether this reflects a role for plant LIS1 proteins in MT regulation or is simply a coincidence awaits experimental evidence linking putative LisH proteins with MT regulation in plants.

LIS1 has been linked genetically and biochemically with dynein/dynactin and CLIP-170 (Willins et al., 1997; Coquelle et al., 2002; Tai et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003). As discussed above, there are no clear CLIP-170, dynein, or dynactin proteins in the genome, so if plants do have bona fide LIS1 family members, they may function differently than they do in other eukaryotic cells.

Kinesins

The Arabidopsis genome has 61 kinesins (Reddy and Day, 2001b; see article by Liu in this issue), and recently one has been found that represents a unique class of +TIPs. ATK5 accumulates preferentially at MT plus ends; however, in contrast with kinesins that rely on motor activity to bring them to the plus ends of MTs, ATK5 is a minus-end-directed kinesin that binds to MT plus ends via the tail-stalk region of the protein (C. Ambrose and R. Cyr, personal communication; Preuss et al., 2004). ATK5 localizes to spindle midzones and phragmoplast leading edges, where MTs are organized in interdigitating, anti-parallel arrays. Phylogenetic analyses (Reddy and Day, 2001b) suggest that the motor domains of several Arabidopsis kinesins are related to motors with known MT plus-end activities in other organisms (Table I). Two sequences are related to the mitotic centromere-associated kinesins (MCAKs) that bind to the ends of MTs and induce depolymerization (Walczak et al., 1996; Maney et al., 1998; Desai et al., 1999; Hunter et al., 2003), and three sequences are related to Kip3p, a motor that positions the spindle by linking MT plus ends to the cell cortex in budding yeast (Schuyler and Pellman, 2001b). Many other Arabidopsis kinesins await functional characterization, and any of those with MT plus-end-directed motor activity could prove to be +TIPs.

SPR1 Proteins

SPR1 is the only plant protein thus far identified as a +TIP serendipitously rather than by genome analysis. SPR1 was identified because roots and hypocotyls of mutant plants have a right-handed helical twist that is thought to result from abnormal cell expansion. Cortical MT orientation is also abnormal in spr1; instead of a transverse orientation, cortical MTs form helical arrays with a left-handed pitch (Furutani et al., 2000). SPR1:GFP fusions localize to MTs in the cortical array, PPB, phragmoplast, and spindle (Nakajima et al., 2004; Sedbrook et al., 2004). In the cortical array, SPR1:GFP forms comet-like shapes on the ends of growing, but not shrinking, MTs, indicating that it is a +TIP (Sedbrook et al., 2004). However, the binding of SPR1 to MTs might be indirect since polymerized tubulin failed to pull down detectable amounts of a GST:SPR1 fusion protein in vitro (Sedbrook et al., 2004), consistent with plus-end accumulation by hitchhiking. How SPR1 affects MTs and how these effects, in turn, regulate cell expansion is unknown.

The SPR1 gene appears to encode a plant-specific +TIP. The predicted protein is a small (12-kD), novel polypeptide that belongs to a plant-specific family of proteins. The Arabidopsis genome contains five other SPR1-like genes that share high sequence identity in their amino- and carboxy-terminal regions and have variable sequences in the intervening regions (Nakajima et al., 2004; Sedbrook et al., 2004), but their association with MTs has not yet been reported. It is plausible that plants have evolved a novel family of +TIPs to regulate their unique MT arrays.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The study of +TIPs in plants has an exciting beginning. Initial GFP fusion analyses confirm their presence on the plus ends of dynamic MTs, and genome gazing suggests that several more putative +TIPs await investigation. Interestingly, it appears that some complexes of +TIPs and their interacting proteins identified in protists and metazoans are also present in plants, while others are absent. Genes coding for the CLIP/dynein/dynactin complex are lacking in Arabidopsis, whereas a yeast pathway using EB1 and actin to deliver MT ends to cortical sites may be conserved (Fig. 2). Analyses of SPR1 and ATK5 demonstrate that plants also have novel +TIPs, perhaps to organize unique plant MT arrays.

Undoubtedly, the next few years will provide explosive progress in this field. Putative +TIPs will be confirmed or rejected by analysis of GFP fusions in vivo, and biochemical studies will identify interacting proteins as well as novel +TIPs. Analyses of mutants and overexpressing lines will help unravel the function of these proteins in regulating MT dynamics and MT search and capture in plant cells. We are beginning to take large strides toward understanding how plants organize their MTs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Peters for critically reading the manuscript and David Gard for drawing the MTs shown in Figure 1.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (award nos. IBN 0110113 and IBN 0414089).

References

- Akhmanova A, Hoogenraad CC, Drabek K, Stepanova T, Dortland B, Verkerk T, De Zeeuw CI, Grosveld F, Galjart N (2001) CLASPs are CLIP-115 and -170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell 104: 923–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askham JM, Vaughan KT, Goodson HV, Morrison EE (2002) Evidence that an interaction between EB1 and p150Glued is required for the formation and maintenance of a radial microtubule array anchored at the centrosome. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3627–3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno H, Chua NH (2000) Characterization of the Arabidopsis formin-like protein AFH1 and its interacting protein. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach DL, Salmon ED, Bloom K (1999) Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr Biol 9: 569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrueta L, Kraeft S-K, Tirnauer JS, Schuyler SC, Chen LB, Hill DE, Pellman D, Bierer BE (1998) The adenomatous polyposis coli-binding protein EB1 is associated with cytoplasmic and spindle microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 10596–10601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M (2001) Spindles cotton on to junctions, APC and EB1. Nat Cell Biol 3: E1–E3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D, Nurse P (2000) CLIP170-like tipe1p spatially organizes microtubular dynamics in fission yeast. Cell 102: 695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu W, Su LK (2003) Characterization of functional domains of human EB1 family proteins. J Biochem 278: 49721–49731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahana A, Escamez T, Nowakowski RS, Hayes NL, Giacobini M, von Holst A, Shmueli O, Sapir T, McConnell SK, Wurst W, et al (2001) Targeted mutagenesis of Lis1 disrupts cortical development and LIS1 homodimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6429–6434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P, Tirnauer JS, Pellman D (2003) Surfing on microtubule ends. Trends Cell Biol 13: 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillon DH, Wasserman SA (1994) Diaphanous is required for cytokinesis in Drosophila and shares domains of similarity with the products of the limb deformity gene. Development 120: 3367–3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Calder GM, Doonan JH, Lloyd CW (2003) EB1 reveals mobile microtubule nucleation sites in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 5: 967–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-R, Chen J, Chang EC (2000) A conserved interaction between Moe1 and Mal3 is important for proper spindle formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell 11: 4067–4077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XP, Yin H, Huffaker TC (1998) The yeast spindle pole body component Spc72p interacts with Stu2p and is required for proper microtubule assembly. J Cell Biol 141: 1169–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle F, Caspi M, Cordelieres FP, Dompierre JP, Dujardin DL, Koifman C, Martin P, Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Galjart N, et al (2002) LIS1, CLIP-170's key to the dynein/dynactin pathway. Mol Cell Biol 22: 3089–3102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvrckova F (2000) Are plant formins integral membrane proteins? Genome Biol 1: RESEARCH001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dawe AL, Caldwell KA, Harris PM, Morris NR, Caldwell GA (2001) Evolutionarily conserved nuclear migration genes required for early embryonic development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Genes Evol 211: 434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks MJ, Hussey PJ, Davies B (2002) Formins: intermediates in signal-transduction cascades that affect cytoskeletal reorganization. Trends Plant Sci 7: 492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Mitchison TJ (1997) Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 13: 83–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Verma S, Mitchison T, Walczak CE (1999) Kin I kinesins are microtubule-destabilizing enzymes. Cell 96: 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Gadella TWJ (2003) Alteration of microtubule dynamic instability during preprophase band formation revealed by yellow fluorescent protein-CLIP170 microtubule plus-end labeling. Plant Cell 15: 596–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin D, Wacker UI, Moreau A, Schroer TA, Rickard JE, De Mey JR (1998) Evidence for a role of CLIP-170 in the establishment of metaphase chromosome alignment. J Cell Biol 141: 849–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M, Zigmond S, Boone C (2003) Formins: signaling effectors for assembly and polarization of actin filaments. J Cell Sci 116: 2603–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furutani I, Watanabe Y, Prieto R, Masukawa M, Suzuki K, Naoi K, Thitamadee S, Shikanai T, Hashimoto T (2000) The SPIRAL genes are required for directional control of cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 127: 4443–4453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galjart N, Perez F (2003) A plus-end raft to control microtubule dynamics and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DL, Becker BE, Romney SJ (2004) MAPping the eukaryotic tree of life: the structure function and evolution of the MAP215/Dis1 family of microtubule-associated proteins. Int Rev Cytol 239: 179–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner J, Marc J (2003) Putative microtubule-associated proteins from the Arabidopsis genome. Protoplasma 222: 61–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson HV, Skube SB, Stalder R, Valetti C, Kreis TE, Morrison EE, Schroer TA (2003) CLIP-170 interacts with dynactin complex and the APC-binding protein EB1 by different mechanisms. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 55: 156–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen GG, Gomes ER, Wen Y (2004) Cortical control of microtubule stability and polarization. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Liu B, Zhang J, Zuo W, Morris NR, Xiang X (2001) The Aspergillus cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain and NUDF localize to microtubule ends and affect microtubule dynamics. Curr Biol 11: 719–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayles J, Nurse P (2001) A journey into space. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil-Chapdelaine RA, Adames NR, Cooper JA (1999) Formin' the connection between microtubules and the cell cortex. J Cell Biol 144: 809–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hyman AA (2003) Dynamics and mechanics of the microtubule plus end. Nature 422: 753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AW, Caplow M, Coy DL, Hancock WO, Diez S, Wordeman L, Howard J (2003) The kinesin-related protein MCAK is a microtubule depolymerase that forms an ATP-hydrolyzing complex at microtubule ends. Mol Cell 11: 445–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey PJ, Hawkins TJ, Igarashi H, Kaloriti D, Smertenko A (2002) The plant cytoskeleton: recent advances in the study of the plant microtubule-associated proteins MAP-65, MAP-190, and the Xenopus MAP215-like protein MOR1. Plant Mol Biol 50: 915–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek WS, Copeland MJ, Chaudhuri A, Chant J (2000) Molecular linkage underlying microtubule orientation toward cortical sites in yeast. Science 287: 2257–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CJ, Morris NR, Meagher RB, Dawe RK (2001) Dyneins have run their course in plant lineage. Traffic 2: 362–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Tirnauer JS, Li J, Schuyler SC, Liu JY, Pellman D (2000) Positioning the mitotic spindle by a cortical microtubule capture mechanism. Science 287: 2260–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W-L, Oberle JR, Cooper JA (2003) The role of the lissencephaly protein Pac1 during nuclear migration in budding yeast. J Cell Biol 160: 355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Warrior R (2000) The Drosophila Lissencephaly1 (DLis1) gene is required for nuclear migration. Dev Biol 226: 57–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lignon LA, Shelly SS, Tokito M, Holzbaur ELF (2003) The microtubule plus-end proteins EB1 and dynactin have differential effects on microtubule polymerization. Mol Biol Cell 14: 1405–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, de Carvalho P, Kho D, Tai C-Y, Pierre P, Fink G, Pellman D (2001) Polyploids require Bik1 for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. J Cell Biol 155: 1173–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Steward R, Luo L (2000) Drosophila Lis1 is required for neuroblast proliferation, dendritic elaboration and axonal transport. Nat Cell Biol 2: 776–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie RK, Bahmanyar S, Siemers KA, Votin V, Chang P, Stearns T, Nelson WJ, Barth AIM (2004) Adenomatous polyposis coli and EB1 localize in close proximity of the mother centriole and EB1 is a functional component of centrosomes. J Cell Sci 117: 1117–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiato H, Fairley EAL, Rieder CL, Swedlow JR, Sunkel CE, Earnshaw WC (2003) Human CLASP1 is an outer kinetochore component that regulates spindle microtubule dynamics. Cell 113: 891–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maney T, Hunter AW, Wagenbach M, Wordeman L (1998) Mitotic centromere-associated kinesin is important for anaphase chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol 142: 787–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, DeWeese-Scott C, Fedorova ND, Geer LW, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Lanczycki CJ, et al (2003) CDD: a curated Entrez database of conserved domain alignments. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 383–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SG, Chang F (2003) Cell polarity: a new mod(e) of anchoring. Curr Biol 13: R711–R713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Mathur N, Kernebeck B, Srinivas BP, Hulskamp M (2003) A novel localization pattern for an EB1-like protein links microtubule dynamics to endomembrane organization. Curr Biol 13: 1991–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher RB, Fechheimer M (2003) The Arabidopsis cytoskeletal genome. In CR Somerville, EM Meyerowitz, eds, The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, doi.org/10.1199/tab.0096, http://www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miller RK, Cheng S-C, Rose MD (2000) Bim1p/Yeb1p mediates the Kar9p-dependent cortical attachment of cytoplasmic microtubules. Mol Biol Cell 11: 2949–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shiina N, Tsukita S (2000) The dynamic behavior of the APC-binding protein EB1 on the distal ends of microtubules. Curr Biol 10: 865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Tsukita S (2003) “Search-and-capture” of microtubules through plus-end-binding proteins (+TIPs). J Biochem (Tokyo) 134: 321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NR (2003) Nuclear positioning: the means is at the ends. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 54–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EE, Wardleworth BN, Askham JM, Markham AF, Meredith DM (1998) EB1, a protein which interacts with the APC tumour suppressor, is associated with the microtubule cytoskeleton throughout the cell cycle. Oncogene 17: 3471–3477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Furutani I, Tachimoto H, Matsubara H, Hashimoto T (2004) SPIRAL1 encodes a plant-specific microtubule-localized protein required for directional control of rapidly expanding Arabidopsis cells. Plant Cell 16: 1178–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Zhou XZ, Lu KP (2001) Critical role for the EB1 and APC interaction in the regulation of microtubule polymerization. Curr Biol 11: 1062–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo AF, Cook TA, Alberts AS, Gunderson GG (2001) mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nat Cell Biol 3: 723–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F, Diamantopoulos GS, Stalder R, Kreis TE (1999) CLIP-170 highlights growing microtubule ends in vivo. Cell 96: 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre P, Scheel J, Rickard JE, Kreis TE (1992) CLIP-170 links endocytic vesicles to microtubules. Cell 70: 887–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss ML, Kovar DR, Le Y-RJ, Staiger CJ, Delmer DP, Liu B (2004) A plant-specific kinesin binds to actin microfilaments and interacts with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol 136: 3945–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ASN, Day IS (2001. a) Analysis of the myosins encoded in the recently completed Arabidopsis thaliana genome sequence. Genome Biol 2: RESEARCH0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reddy ASN, Day IS (2001. b) Kinesins in the Arabidopsis genome: a comparative analysis among eukaryotes. BMC Genomics 2: 2–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehberg M, Graf R (2002) Dictyostelium EB1 is a genuine centrosomal component required for proper spindle formation. Mol Biol Cell 13: 2301–2310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O (2000) LIS1: Let's interact sometimes… (part 1). Neuron 28: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Rogers GC, Sharp DJ, Vale RD (2002) Drosophila EB1 is important for proper assembly, dynamics, and positioning of the mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol 158: 873–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders PR, Winter JS, Barnason AR, Rogers SG, Fraley RT (1987) Comparison of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S and nopaline synthase promoters in transgenic plants. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 1543–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer TA (2001) Microtubules don and doff their caps: dynamic attachments at plus and minus ends. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13: 92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler SC, Pellman D (2001. a) Microtubule “plus-end-tracking proteins”: The end is just the beginning. Cell 105: 421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler SC, Pellman D (2001. b) Search, capture, and signal: games microtubules and centrosomes play. J Cell Sci 114: 247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K, Richards K, Botstein D (1997) BIM1 encodes a microtubule-binding protein in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 8: 2677–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedbrook JC, Ehrhardt DW, Fisher SE, Scheible W-R, Somerville C (2004) The Arabidopsis SKU6/SPIRAL gene encodes a plus end-localized microtubule-interacting protein involved in directional cell expansion. Plant Cell 16: 1506–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SL, Kamyar R, Ehrhardt DW (2003) Sustained treadmilling in Arabidopsis cortical arrays. Science 300: 1715–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LG, Gerttula SM, Han S, Levy J (2001) TANGLED1: A microtubule binding protein required for the spatial control of cytokinesis in maize. J Cell Biol 152: 231–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube A, Brill M, Oakley BR, Horio T, Steinberg G (2003) Microtubule organization requires cell cycle-dependent nucleation at dispersed cytoplasmic sites: polar and perinuclear microtubule organizing centers in the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. Mol Biol Cell 14: 642–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Burrell M, Gyuris J, Brent R, Wiltshire R, Trent J, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW (1995) APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Res 55: 2972–2977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai C-Y, Dujardin DL, Faulkner N, Vallee RB (2002) Role of dynein, dynactin, and CLIP-170 interactions in LIS1 kinetochore function. J Cell Biol 156: 959–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer JS, Grego S, Salmon ED, Mitchison TJ (2002) EB1-microtubule interactions in Xenopus egg extracts: role of EB1 in microtubule stabilization and mechanisms of targeting to microtubules. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3614–3626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer JS, O'Toole E, Berrueta L, Bierer BE, Pellman D (1999) Yeast Bim1p promotes the G1-specific dynamics of microtubules. J Cell Biol 145: 993–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournebize R, Popov A, Kinoshita K, Ashford A, Rybina S, Pozniakovsky A, Mayer TU, Walczak CE, Karsenti E, Hyman AA (2000) Control of microtubule dynamics by the antagonistic activities of XMAP215 and XKCM1 in Xenopus egg extracts. Nat Cell Biol 2: 13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traas J, Bellini C, Nacry P, Kronenberger J, Bouchez D, Caboche M (1995) Normal differentiation patterns in plants lacking microtubular preprophase bands. Nature 375: 676–677 [Google Scholar]

- Twell D, Park SK, Hawkins TJ, Schubert D, Schmidt R, Smertenko A, Hussey PJ (2002) MOR1/GEM1 has an essential role in the plant-specific cytokinetic phragmoplast. Nat Cell Biol 4: 711–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JW, Dogterom M, Emons AMC (2004) Microtubules become more dynamic but not shorter during preprophase band formation: a possible “search and capture” mechanism for microtubule translocation. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 57: 246–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak CE, Mitchison T, Desai A (1996) XKCM1: a Xenopus kinesin-related protein that regulates microtubule dynamics during mitotic spindle assembly. Cell 84: 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO (2002) Microtubule organization in the green kingdom: chaos or self-order? J Cell Sci 115: 1345–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington AT, Vugrek O, Wei KJ, Hasenbein NG, Sugimoto K, Rashbrooke MC, Wasteneys GO (2001) MOR1 is essential for organizing cortical microtubules in plants. Nature 411: 610–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick S (2003) Plant microtubule nucleation sites: moving right along. Nat Cell Biol 5: 954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willins DA, Liu B, Xiang X, Morris NR (1997) Mutations in the heavy chain of cytoplasmic dynein suppress the nudF nuclear migration mutation of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet 255: 194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X (2003) LIS1 at the microtubule plus end and its role in dynein-mediated nuclear migration. J Cell Biol 160: 289–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X, Osmani AH, Osmani SA, Xin M, Morris NR (1995) NudF, a nuclear migration gene in Aspergillus nidulans is similar to the human LIS-1 gene required for neuronal migration. Mol Biol Cell 6: 297–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Pruyne D, Huffaker TC, Bretscher A (2000) Myosin V orientates the mitotic spindle in yeast. Nature 406: 1013–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li S, Fischer R, Xiang X (2003) Accumulation of cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin at microtubule plus ends in Aspergillus nidulans is kinesin dependent. Mol Biol Cell 14: 1479–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]