Abstract

Cytosolic free Ca2+ and actin microfilaments play crucial roles in regulation of pollen germination and tube growth. The focus of this study is to test the hypothesis that Ca2+ channels, as well as channel-mediated Ca2+ influxes across the plasma membrane (PM) of pollen and pollen tubes, are regulated by actin microfilaments and that cytoplasmic Ca2+ in pollen and pollen tubes is consequently regulated. In vitro Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) pollen germination and tube growth were significantly inhibited by Ca2+ channel blockers La3+ or Gd3+ and F-actin depolymerization regents. The inhibitory effect of cytochalasin D (CD) or cytochalasin B (CB) on pollen germination and tube growth was enhanced by increasing external Ca2+. Ca2+ fluorescence imaging showed that addition of actin depolymerization reagents significantly increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels in pollen protoplasts and pollen tubes, and that cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase induced by CD or CB was abolished by addition of Ca2+ channel blockers. By using patch-clamp techniques, we identified the hyperpolarization-activated inward Ca2+ currents across the PM of Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts. The activity of Ca2+-permeable channels was stimulated by CB or CD, but not by phalloidin. However, preincubation of the pollen protoplasts with phalloidin abolished the effects of CD or CB on the channel activity. The presented results demonstrate that the Ca2+-permeable channels exist in Arabidopsis pollen and pollen tube PMs, and that dynamic actin microfilaments regulate Ca2+ channel activity and may consequently regulate cytoplasmic Ca2+.

The primary function of pollen and pollen tubes is to deliver sperms to egg apparatus for double fertilization that is required for sexual reproduction of flowering plants. Pollen germination and pollen tube growth are a continuous and highly polarized process characteristic of tip growth; thus pollen and pollen tubes provide an ideal model system for the study of cell polarity control and tip growth. It is well known that extracellular Ca2+ is required for pollen germination and tube growth (for review, see Steer and Steer, 1989; Taylor and Hepler, 1997; Malhó, 1998; Franklin-Tong, 1999), which indicates a possible involvement of Ca2+ influx in pollen germination and tube growth. Upon pollen hydration and germination, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) at the germinal aperture where the pollen tube emerges increases to a higher level than other regions, and a tip-focused Ca2+ gradient is then established and sustained while a pollen tube grows forward (Rathore et al., 1991; Pierson et al., 1994; Feijó et al., 1995). Disruption or modification of the Ca2+ gradient inhibits pollen tube growth (Miller et al., 1992) or changes its growth direction (Malhó and Trewavas, 1996). The tip-focused Ca2+ gradient oscillates in the pollen tubes of lily (Lilium longiflorum) and other species (Holdaway-Clarke et al., 1997; Messerli and Robinson, 1997; Messerli et al., 2000). Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular Ca2+ sink (such as vacuole or endoplasmic reticulum) and extracellular Ca2+ influx at pollen tube tips are believed to be two possible Ca2+ sources for establishing the Ca2+ gradient and oscillation. It is well established that the phospholipase C (PLC)-inositol triphosphate (IP3) system mobilizes the intracellular Ca2+ in animal cells (for review, see Berridge et al., 2000). In lily pollen tubes, PLC activity has also been demonstrated (Helsper et al., 1987). This result was confirmed later in Papaver rhoeas pollen tubes, and the PLC-IP3 system was further demonstrated to be involved in pollen tube growth by propagating slow-moving calcium waves (Franklin-Tong et al., 1996). On the other hand, several lines of evidence indicate that the tip-focused Ca2+ gradient, as well as its oscillation, requires tip-localized extracellular Ca2+ influxes (Pierson et al., 1994, 1996; for review, see Rudd and Franklin-Tong, 1999). Furthermore, studies using Mn2+-quenching techniques imply the presence of plasma membrane (PM)-localized Ca2+ channels in pollen tubes (Malhó et al., 1995). However, definitive identification and characterization of Ca2+-permeable channels in pollen and pollen tubes requires application of patch-clamp techniques to directly detect activity of Ca2+-permeable channels. Unfortunately, all attempts so far to apply the patch-clamp techniques to pollen tubes have been unsuccessful because protoplasts from the pollen tube apex are hypersecretory, thereby preventing giga-ohm seal formation between the membrane and the patch-clamp electrodes (Sanders et al., 1999). However, application of the patch-clamp techniques to pollen protoplasts has been successful (Obermeyer and Kolb, 1993; Fan et al., 1999, 2001; Fan and Wu, 2000; Griessner and Obermeyer, 2003). Considering that pollen germination and tube growth are a continuous process, it is reasonable to postulate that there may exist the same types of Ca2+-permeable channels in both pollen and pollen tube PMs.

A number of previous studies have demonstrated that the actin cytoskeleton plays a critical role in regulation of pollen germination and pollen tube growth (Fu et al., 2001; for additional refs., see reviews in Staiger, 2000; Vidali and Hepler, 2000). Pollen activation and germination are accompanied by the gradual replacement of large F-actin aggregates present in the vegetative cytoplasm by a filamentous network that converges on the germinal aperture and eventually ramifies the pollen tube. This arrangement of actin microfilaments may be required for particle movement and contributes to tip growth by directing vesicle traffic to the tip. However, the experimental results for existence of actin microfilaments at the very tip of pollen tubes had been controversial. Early studies with chemical fixation and fluorescent phalloidin-labeling techniques have suggested the presence of a dense actin network at the extreme tip (Derksen et al., 1995). In disagreement with this result, rapid freezing, freeze substitution, and electron and light microscopy techniques revealed only thin actin bundles and short individual actin microfilaments in random orientation (Lancelle et al., 1987; Doris and Steer, 1996). Also, no actin network was observed in living lily pollen tubes stained by injected fluorescence-labeled phalloidin (Miller et al., 1996). These studies have led to a notion of the tube tip actin-free clear zone proposition that is free of F-actin (for review, see Vidali and Hepler, 2000). However, by using improved fixation methods (Staiger et al., 1994) or using expression of green fluorescent protein-mTalin techniques (Kost et al., 1998; Fu et al., 2001), an actin ring in the subapical region of pollen tubes has been revealed. A collar structure of F-actin was also described in chemically fixed maize and Papaver pollen tubes (Gibbon et al., 1999; Geitmann et al., 2000). The collar structure seems to be composed of fine actin microfilaments instead of thick F-actin bundles like those in a pollen tube shank. Gibbon et al. (1999) showed that tip elongation of either pollen tubes or root hairs was inhibited by treatment with a low concentration of cytochalasin D (CD) or latrunculin, which disrupted the subapical F-actin ring but did not markedly affect the thick axis actin bundles and cytoplasm streaming. By expressing green fluorescent protein-mTalin, Fu et al. (2001) have clearly demonstrated the presence of a dynamic change of tip-localized F-actin in living tobacco pollen tubes, and the dynamic tip actin appears as short actin bundles. Time-course analysis also suggests that the actin collar structure appears to alternate with the F-actin dynamics (Fu et al., 2001). They have also shown that the amount of tip F-actin oscillates in the opposite phase with pollen tube elongation rates and the oscillation of tip [Ca2+]i, and that the peak of tip F-actin precedes that of tube growth. These observations led to a hypothesis that the dynamic F-actin may cross-talk with the tip [Ca2+]i dynamics, playing in concert a crucial role in the regulation of pollen tube growth. Nevertheless, mechanisms underlying the interaction between dynamic F-actin and oscillating cytoplasmic Ca2+ at the pollen tube tip are not yet established.

The involvement of actin microfilaments in ion channel regulation has been well established in animal cells (Negulyaev et al., 2000), and the regulation of PM K+ channels by actin microfilaments has also been reported in plant cells (Hwang et al., 1997; Liu and Luan, 1998). We hypothesize that actin microfilaments may also play an important role in regulating PM Ca2+-permeable channels during pollen germination and tube growth processes. In this article, using the patch-clamp techniques, we have identified a Ca2+-permeable channel in the PM of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) pollen protoplasts. In combination with in vitro pollen germination assay and [Ca2+]i measurement with the laser-scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) technique, we show that the actin cytoskeleton regulates the activity of Ca2+-permeable channels in the pollen PM. Our results support a tight and finely controlled connection between actin dynamics and [Ca2+]i oscillation at the tip of a pollen tube.

RESULTS

Actin Depolymerization Reagent-Caused Inhibition of Arabidopsis Pollen Germination and Tube Growth Is Enhanced by Increasing [Ca2+]o and Ca2+ Influx

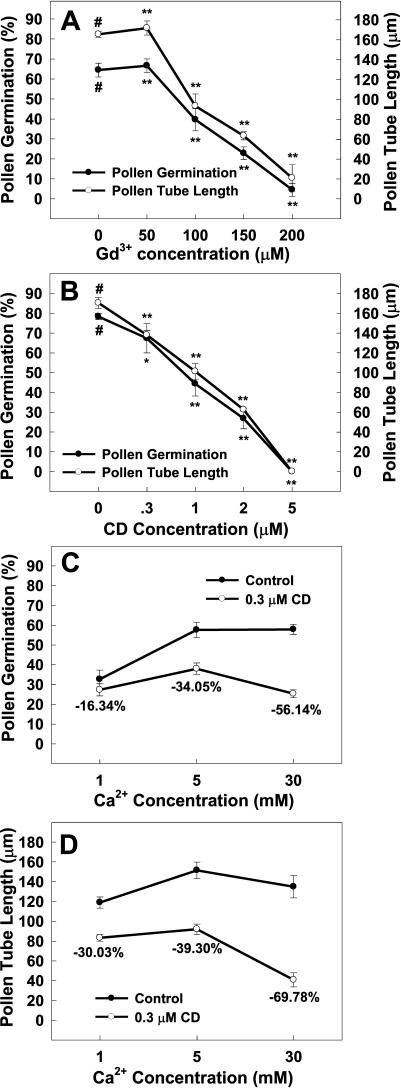

Inorganic Ca2+ channel blockers Gd3+ and La3+ and organic blocker verapamil, which are commonly used to identify PM Ca2+ channels (Pineros and Tester, 1997), were applied to test their effects on Arabidopsis pollen germination and tube growth. The previous studies have shown that Ca2+ channel blocker-induced inhibition of pollen germination and tube growth is possibly correlated with the inhibition of Ca2+ influx (Feijó et al., 1995, and refs. therein). As shown in Figure 1A, both in vitro pollen germination and tube growth were significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by Gd3+ at the concentrations higher than 50 μm. The addition of 200 μm Gd3+ in the medium almost completely inhibited pollen germination and tube growth (Fig. 1A). The addition of La3+ to the medium resulted in very similar inhibitory effects on pollen germination and tube growth (data not shown) as the addition of Gd3+ did, while addition of 600 μm verapamil inhibited pollen germination by 88% and tube growth by 46% (data not shown). These results suggest that Ca2+ influx mediated by Ca2+-permeable channels in the PM of Arabidopsis pollen or pollen tubes is involved in the regulation of pollen germination and tube growth.

Figure 1.

Effects of Ca2+ channel blocker Gd3+ (A) and actin depolymerizing reagent CD (B–D) on Arabidopsis pollen germination and tube growth. The ingredients of the in vitro germination media and the detailed experimental protocols were described in “Materials and Methods.” The external Ca2+ concentration for A and B was 5 mm. All experiments were repeated three times and each treatment in one experiment had four replicates. For each replicate, 400 pollen grains were counted for calculation of pollen germination rate and 80 pollen tubes were measured for their growth length. Data were presented as mean ± se from three independent experiments. #, Data point for the control; **, significantly different from the control at P < 0.01 by Student's t test.

To test whether the actin cytoskeleton is involved in regulation of pollen germination and tube growth, actin depolymerization reagents were added to the germination medium. The pollen germination and tube growth were significantly inhibited by those actin depolymerization reagents in a dose-dependent manner. Addition of 5 μm CD (Fig. 1B), 2 μm cytochalasin B (CB; data not shown), or 1 nm latrunculin A (Lat A; data not shown) completely inhibited pollen germination and tube growth. It should also be noted that the tube tips showed swollen shapes subject to addition of any of these reagents (data not shown). However, addition of either oryzalin, a microtubule depolymerization reagent, or taxol, a microtubule stabilizer, in the germination medium at concentrations from 1 to 50 μm did not affect Arabidopsis pollen germination and tube growth (data not shown), indicating that microtubules do not play an important role in the regulation of pollen germination and tube growth.

Interestingly, the inhibitory effects of low concentrations of actin depolymerization reagents on pollen germination and tube growth were significantly enhanced by increasing the external Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]o) from 1 mm to 5 or 30 mm (Fig. 1, C and D). Along with the increase of [Ca2+]o from 1 mm to 5 or 30 mm, the inhibition of pollen germination by 0.3 μm CD increased from 16.34% to 34.05% or to 56.14% (Fig. 1C), while the inhibition of tube growth increased from 30.03% to 39.30% or to 69.78% (Fig. 1D), respectively. Similarly, increasing [Ca2+]o also enhanced inhibition of pollen germination and tube growth induced by 0.2 μm CB (data not shown).

These findings suggest that the inhibition of pollen germination and tube growth by depolymerization of actin microfilaments may be, at least in part, due to its enhancement of Ca2+ influx into pollen or pollen tubes, and that activity of the Ca2+-permeable PM channels may be regulated by actin microfilaments.

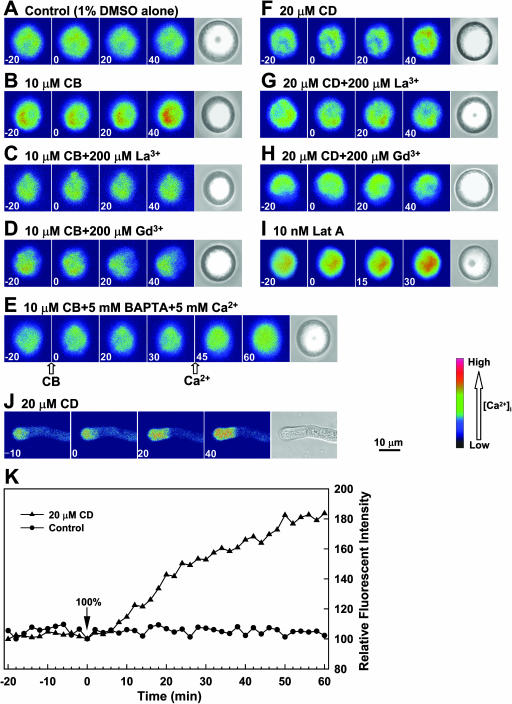

Actin Depolymerization Reagent-Induced Elevations of [Ca2+]i in Pollen Protoplasts and Pollen Tubes Are [Ca2+]o Dependent

If actin microfilaments affect extracellular Ca2+ influx, we would expect that the cytosolic Ca2+ levels will be elevated by the depolymerization of actin microfilaments. To test this hypothesis, Fluo-3/AM, a Ca2+-specific fluorescence indicator, was preloaded into pollen protoplasts and pollen tubes, and changes in the relative cytosolic Ca2+ levels were monitored with LSCM upon application of various reagents. As shown in Figure 2, the intensity of Fluo-3 fluorescence in the pollen protoplasts was increased significantly after incubating the protoplasts with 10 μm CB (Fig. 2B versus 2A), and 18 out of 21 tested protoplasts showed this positive response. This CB-induced [Ca2+]i increase was eliminated by the addition of 200 μm La3+ (Fig. 2C) or 200 μm Gd3+ (Fig. 2D) to the incubation buffer. Addition of 5 mm 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) abolished CB-induced [Ca2+]i increase even in the presence of 5 mm external Ca2+ (Fig. 2E). Similar results were observed for the addition of 20 μm CD to the incubation buffer (Fig. 2, F–H), and 18 out of 21 tested protoplasts showed CD-induced [Ca2+]i increase. The time kinetics of quantitative changes in cytosolic calcium concentrations induced by CD is shown in Figure 2K. Compared to the treatments with CB or CD, Lat A was more efficient in elevating [Ca2+]i in pollen protoplasts at as low as 10 nm (Fig. 2I). Similarly, the fluorescence in a pollen tube was also enhanced by 20 μm CD (Fig. 2J), 10 μm CB, or 10 nm Lat A (data not shown). Among 12 tested pollen tubes, there were 10 pollen tubes showing CB-induced [Ca2+]i increase. For treatment with CD, eight out of nine tested pollen tubes showed the positive response. However, neither 50 μm oryzalin nor 50 μm taxol had a detectable effect on the intensity of Fluo-3 fluorescence in either pollen protoplasts or pollen tubes (data not shown), which suggests that the microtubule cytoskeleton may not play role in the regulation of Ca2+ influx. These results demonstrate that the F-actin depolymerization-induced [Ca2+]i elevation was due to extracellular Ca2+ influx, likely through the Ca2+-permeable channels in the PM of pollen or pollen tubes.

Figure 2.

Actin depolymerization reagent-induced elevations of [Ca2+]i in pollen protoplasts or pollen tubes resulted from Ca2+ influx. Fluo-3 fluorescent images were acquired by LSCM and the time (min) before or after the specific treatment is indicated at the bottom left of each image. The relative fluorescence intensities were presented as pseudocolors. A, Control, showing that 1% DMSO (the final concentration of DMSO used for making the stock solutions of CB, CD, and Lat A) had no effect on Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity in protoplasts. B, A total of 10 μm CB markedly increased Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity. C and D, A total of 200 μm La3+ or Gd3+ impaired CB-induced increase in Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity, respectively. E, A total of 5 mm BAPTA inhibited CB-induced increase in Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity even after addition of 5 mm Ca2+ to the incubation buffer (the arrows indicate the time when CB or Ca2+ was added). F, A total of 20 μm CD induced increase of Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity. G and H, A total of 200 μm La3+ or Gd3+ abolished CD-induced increase in Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity, respectively. I, A total of 10 nm Lat A dramatically induced increase of Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity. J, The left four images show Fluo-3 fluorescence intensity in pollen tubes increased with time after treatment with 20 μm CD, and the far right image shows the pollen tube in bright field. K, Time kinetics of quantitative changes in cytosolic calcium concentrations induced by CD. The vertical colored bar at the right illustrates the relative cytosolic Ca2+ levels.

Identification and Characterization of Hyperpolarization-Activated Ca2+-Permeable Channels in Arabidopsis Pollen Protoplasts

The results presented above suggest that Ca2+-permeable channels may exist in the PM of Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts and the Ca2+-permeable channels may play a role in the regulation of pollen germination and tube growth. To further test this notion, patch-clamp techniques were applied to directly identify and characterize the PM Ca2+ channels in Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts in this study.

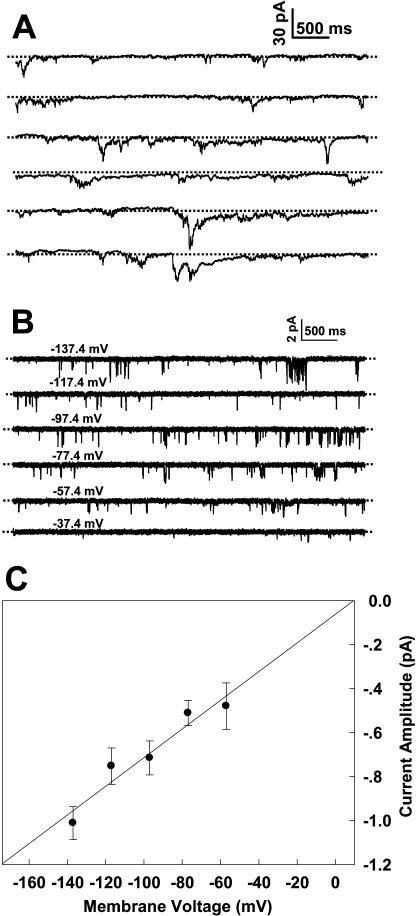

Figure 3 shows patch-clamp recordings of the inward currents from Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts under the control conditions as described in “Materials and Methods.” The whole-cell inward currents recorded at −160 mV occurred in a periodic pattern as shown in Figure 3A. This periodic current bursting may reflect a natural periodic oscillation of the channel activity across the PM. Figure 3B shows a typical recording of the inward single-channel currents from an outside-out membrane patch, and Figure 3C shows the current/voltage (I/V) relationship derived from the recording data as shown in Figure 3B. The reversal potential of the recorded channel was approximately +10 mV obtained by extrapolation of the I/V curve as shown in Figure 3C. A conductance of 6.5 ± 0.5 picoSiemens (pS; n = 6) for the recorded channel under the described conditions was derived according to the equation G = I/(E − Erev), where G, I, E, and Erev represent the single-channel conductance, the current amplitude, the membrane potential applied, and the reversal membrane potential, respectively. In theory, both influx of cations and efflux of anions may result in observation of inward current signals. To ensure that the recorded inward currents only represent the signals of extracellular Ca2+ influx, the external (extracellular) and internal (intracellular) solutions for patch-clamp recording were carefully designed. For the solutions used for the control conditions, the major ions are Ca2+ and Cl−. According to the Nernst equation, the Erev for Ca2+ and Cl− was +194 mV and −174 mV, respectively, under the control conditions. Because Cl− efflux can only occur at a more negative voltage than −174 mV, it is impossible for Cl− efflux through the PM when an applied voltage was more positive than −174 mV. Considering that the voltages applied in our experiments were always more positive than −160 mV, the possibility that Cl− efflux contributes to the recorded inward current signals can be excluded. The theoretical Nernst potential of +194 mV for Ca2+ ions was the closest to the experimental reversal potential of +45 mV, which led us to determine the nature of the recorded currents as Ca2+ currents. In addition, Glu is another anion included in the solutions. However, Glu is believed to be an impermeable anion in ion channel studies (Pei et al., 1998), and also there was no change of either single-channel conductance or reversal potential observed in our experiment when the intracellular Glu concentration was changed (data not shown). Thus, contribution of Glu efflux to the recorded inward currents can also be excluded. Therefore, considering Ca2+ as the only cation in the external solutions, Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels could be the only source that accounted for the inward currents under the given conditions in our experiments.

Figure 3.

Patch-clamp whole-cell (A) and single-channel recordings (B) of the inward currents from Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts. A, A whole-cell recording from an Arabidopsis pollen protoplast at −160 mV shows the periodic inward currents. B, Single-channel recordings from an outside-out membrane patch of an Arabidopsis pollen protoplast at various voltages. C, I/V relationship derived from six membrane patches. The data points in C represent mean ± sd (n = 6). The dashed lines in A and B represent the closed state of channels.

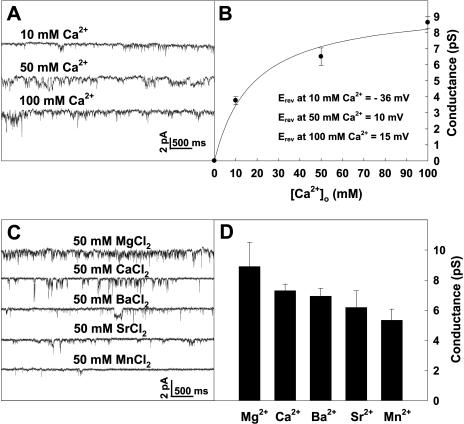

The extracellular Ca2+ dependence of the single-channel conductance of the inward currents supports the above notion. If the inward current mainly resulted from Ca2+ influx, its single-channel conductance should increase along with increasing Ca2+ gradient in an outside-to-inside direction across the PM. It was observed that the single-channel conductance of the inward currents increased from 3.8 pS to 6.5 or 8.64 pS when the extracellular Ca2+ concentration was changed from 10 mm to 50 or 100 mm, respectively, when the intracellular Ca2+ concentration remained unchanged (Fig. 4, A and B). The relationship of single-channel conductance versus extracellular Ca2+ concentration was well fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation as shown in Figure 4B, which gives a half-conductance Ca2+ concentration of approximately 18 mm. In addition, with the increases in external Ca2+, the reversal potential (Erev) of the Ca2+ currents shift to more positive voltages (Fig. 4B, inset), which is consistent with the shifting direction of Ca2+ equilibrium potential (ECa). The result that the inward current was no longer observed in the absence of external Ca2+ further confirms that the recorded inward currents were due to Ca2+ influx.

Figure 4.

Dependence of the inward current conductance on external Ca2+ concentrations (A and B) and the permeability of various divalent cations to the PM of Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts (C). A, Single-channel recordings from the same outside-out membrane patch at −160 mV at different external Ca2+ concentrations. B, The relationship of single-channel conductance versus external Ca2+ concentration derived from the recordings as shown in A, which was well fit by the Michaelis-Menten equation. The changes in Erev at different external Ca2+ are also shown in inset of B. C, Single-channel recordings from the same outside-out membrane patch at −160 mV with different divalent cations in external (bath) solutions. D, Histograms of single-channel conductance derived from the recordings as shown in C. Dashed line in A and C indicates the closed state of the channels. Time and current scale bars are displayed in A and C. Data in B and D are presented as mean ± se (n = 5 for B; n = 3 for D).

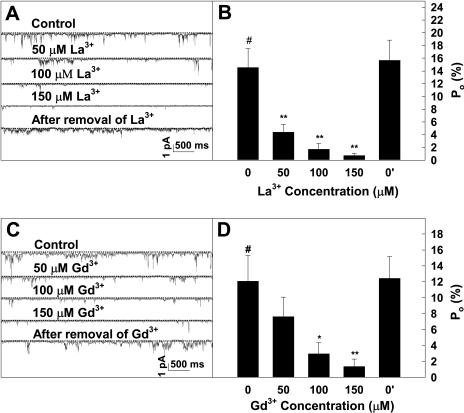

It has been reported that Ca2+ channels may also be permeable to other divalent cations, such as Ba2+, Mg2+, Sr2+, and Mn2+ (Pineros and Tester, 1997). The results presented in Figure 4, C and D show that the recorded channels have different permeability to various divalent cations in a sequence of relative permeability as Mg2+ > Ca2+ > Ba2+ > Sr2+ > Mn2+. To further identify whether the recorded inward currents were mediated by Ca2+ channels, effects of widely used Ca2+ channel blockers on the channel activity were tested. It was observed that the inward currents were dramatically inhibited by La3+ (Fig. 5, A and B) or Gd3+ (Fig. 5, C and D) in a dose-dependent manner. Total open probability (Po) of the channels at −160 mV decreased by 95% or 98% in the presence of 150 μm La3+ or 150 μm Gd3+, respectively. Notably, the inhibition of the inward currents by La3+ or Gd3+ was removed reversibly by washing out the drugs from the extracellular solution (Fig. 5, A–D). However, the inward currents were not affected by verapamil (data not shown). These results clearly demonstrate that the recorded inward currents in this study were mediated by hyperpolarization-activated and La3+- and Gd3+-sensitive Ca2+-permeable channels in the PM of Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts.

Figure 5.

Calcium channel blocker La3+ (A and B) or Gd3+ (C and D) induced decrease of Po of the channels in a dose-dependent manner. A, A series of single-channel recordings from the same outside-out membrane patch at −160 mV without or with La3+ at different concentrations in external solutions. B, Histograms of single-channel conductance versus La3+ concentration, derived from the recordings as shown in A. C, Single-channel recordings from the same outside-out membrane patch at −160 mV without or with Gd3+ at different concentrations in external solutions. D, Histograms of single-channel conductance versus Gd3+ concentration, derived from the recordings as shown in C. Dashed lines in A and C indicate the closed state of the channels. Time and current scale bars are displayed in A and C. Data in B and D are presented as mean ± se (n = 5). #, Data point for the control; *, significantly different from the control at P < 0.05 by Student's t test; **, significantly different from the control at P < 0.01 by Student's t test.

Ca2+-Permeable Channels in Arabidopsis Pollen Protoplasts Are Regulated by Dynamic Actins

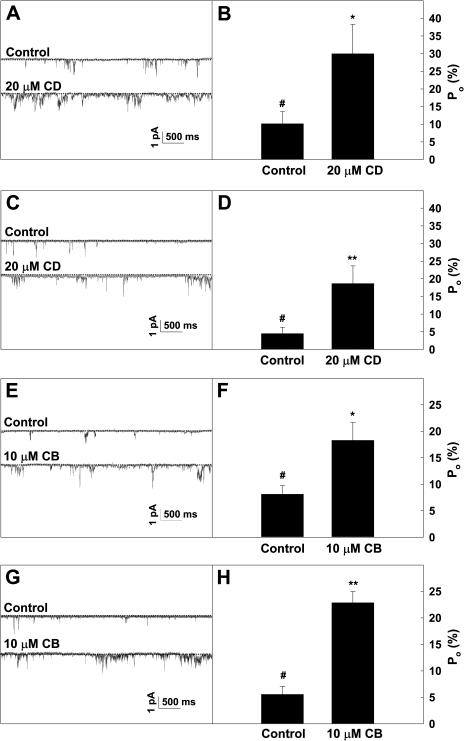

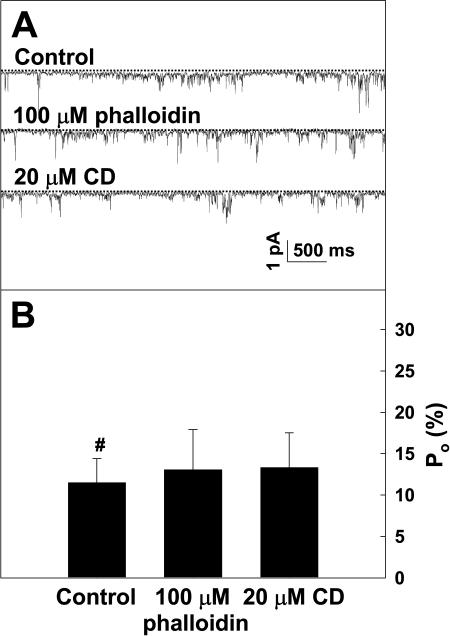

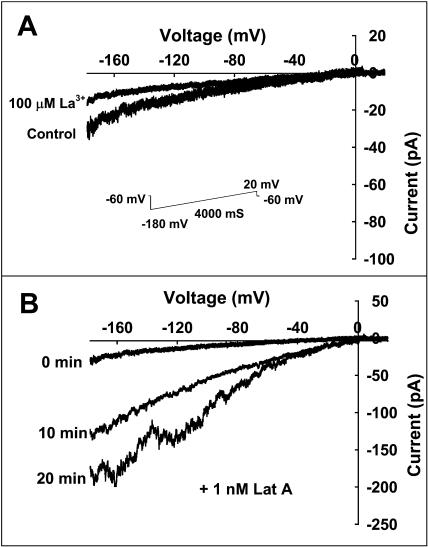

Following the experiments to identify Ca2+-permeable channels in Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts, as presented in Figures 3 to 5, further patch-clamp experiments were conducted to test the hypothesis that Ca2+ channel-mediated Ca2+ influx was regulated by F-actin. The previous study (Horber et al., 1995) had demonstrated that cytoskeleton structures are still present in the excised membrane patches. CD or CB was applied to the excised membrane patches to observe their possible effect on the calcium channel activity. Figure 6 illustrates the effects of CD and CB on the Ca2+ channel activity at −160 mV. After the protoplasts were incubated with 20 μm CD for 20 to 30 min, the Po of the Ca2+ channels increased markedly, on the average by 194.7% for the inside-out membrane patches (Fig. 6, A and B) and by 273.6% for the outside-out membrane patches (Fig. 6, C and D). The similar results were observed for the treatment with 10 μm CB as shown in Figure 6, E to H. A pretreatment with 100 μm phalloidin abolished the inhibitory effect of CD on the channel activity, although 100 μm phalloidin alone did not have any detectable effect (Fig. 7, A and B). The results presented in Figure 8 show that Lat A (a more specific actin-depolymerizing drug) significantly activated Ca2+ currents at the whole-cell level, and the whole-cell Ca2+ currents were similarly inhibited by the Ca2+ channel blocker La3+. In addition, the treatments with 50 μm oryzalin or 50 μm taxol did not result in any detectable effect on the Ca2+ currents (data not shown), indicating that the Ca2+-permeable channels are not regulated by the microtubule cytoskeleton. This is consistent with our observations that these drugs did not affect pollen germination and tube growth or cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. These results suggest that the disassembly of F-actin induces activation of the Ca2+-permeable channels in the PM of Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts.

Figure 6.

Actin depolymerization reagent CD (A–D) or CB (E–H) induced increases of the Po of the Ca2+ channels. A and C, Single-channel recordings at −137 mV from an inside-out membrane patch or an outside-out membrane patch, respectively, in the absence (control; upper trace) or presence (lower trace) of 20 μm CD. B and D, Po of the channels derived from the recordings as shown in A and C), respectively. E and G, Single-channel recordings at −137 mV from an inside-out membrane patch or an outside-out membrane patch, respectively, in the absence (control; upper trace) or presence (lower trace) of 10 μm CB. F and H, Po of the channels derived from the recordings as shown in E and G, respectively. The dashed lines in A, C, E, and G indicate the closed state of the channels. Time and current scale bars are shown in A, C, E, and G. Data in B, D, F, and H are presented as mean ± se (n = 5). #, Data point for the control; *, significantly different from the control at P < 0.05 by Student's t test; **, significantly different from the control at P < 0.01 by Student's t test.

Figure 7.

Actin stabilizer phalloidin eliminates the increase in Po of the Ca2+ channels by 20 μm CD. A, Single-channel recordings from the same inside-out membrane patch at −137 mV without (upper trace) or with (middle trace) treatment by 100 μm phalloidin or by 100 μm phalloidin plus 20 μm CD (lower trace). B, Po of the channels derived from the recordings as shown in A. The dashed lines in A indicate the closed state of the channels. Time and current scale bars are displayed in A. The data in B are presented as mean ± se (n = 5).

Figure 8.

Hyperpolarization-activated whole-cell Ca2+ currents in Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts. Whole-cell currents were measured during a 4-s voltage ramp between −160 and +20 mV (the voltage protocols are shown in A). A, Whole-cell Ca2+ currents were inhibited by 100 μm La3+. B, Whole-cell Ca2+ currents were stimulated by 1 nm Lat A.

Taking all presented results together, it is concluded that the actin cytoskeleton plays a role in regulating the activity of the inward Ca2+-permeable channels present in the Arabidopsis pollen PM and consequent cytoplasmic free Ca2+ levels. The results support the hypothesis that dynamic change between F-actin and G-actin at the tip of a pollen tube provides an important mechanism for the Ca2+ oscillation at the tip of a pollen tube.

DISCUSSION

A cytosolic Ca2+ gradient as well as its oscillation is considered to play a central role in the regulation of pollen germination and tube growth (Rathore et al., 1991; Miller et al., 1992; Pierson et al., 1994; Malhó and Trewavas, 1996; Holdaway-Clarke et al., 1997; for review, see Feijó et al., 1995; Holdaway-Clarke and Hepler, 2003). Several lines of evidence suggest that PM Ca2+ channels may be prominently involved in the regulation of this Ca2+ gradient (Pierson et al., 1994, 1996; Malhó et al., 1995). Ca2+ influx in pollen or pollen tubes has been investigated by using 45Ca2+ (Jaffe et al., 1975), Ca2+-selective vibrating probes (Kuhtreiber and Jaffe, 1990; Pierson et al., 1994; Holdaway-Clarke et al., 1997; Messerli et al., 1999; Franklin-Tong et al., 2002), and Mn2+-quenching techniques (Malhó et al., 1995). However, direct detection of Ca2+ channels in the PM of pollen or pollen tubes by using patch-clamp techniques has not been reported. In this study, we have identified Ca2+-permeable channels in pollen protoplasts using patch-clamp whole-cell and single-channel recording techniques. We also show that Ca2+ channels in pollen protoplasts are regulated by actin dynamics, supporting the hypothesis that the actin cytoskeleton may regulate Ca2+ channel activity and subsequently Ca2+ influx as well as cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation at the tip of pollen tubes.

Identification of Ca2+ Channels in Arabidopsis Pollen Protoplasts

The most significant and important aspect of this study is the identification and characterization of the Ca2+-permeable channels in the PM of pollen protoplasts. First, our careful design of the solutions used for patch-clamp recordings ensured that the nature of the recorded currents was Ca2+ currents. Under the control conditions, the Erev for Ca2+ or Cl− was +194 mV or −174 mV, respectively, according to the Nernst equation. This made Cl− efflux impossible to occur since all the applied clamp voltages were more positive than −174 mV. Second, a possible Glu efflux can also be excluded given that this anion is generally believed to be impermeable to the PM (Pei et al., 1998) and that there was no change of either single-channel conductance or reversal potential observed when the intracellular Glu concentration was changed in this study. Third, the single-channel conductance of the recorded inward currents was dependent upon extracellular Ca2+. Therefore, as the only cation in the extracellular solutions, Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels could be the only source that accounted for the recorded inward currents under the given conditions in the presented experiments.

Further support for the existence of PM Ca2+ channels in pollen comes from the experiments using Ca2+ channel blockers. We found that the inward currents were dramatically inhibited by Gd3+ or La3+ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5, A–D). Gd3+ and La3+ have been successfully used to inhibit Mn2+ entry into Agapanthus pollen tubes (Malhó et al., 1995), which reflects Gd3+ and La3+ inhibition on Ca2+ influx and extracellular Ca2+ fluxes into P. rhoeas pollen tubes (Franklin-Tong et al., 2002). We showed that the inward currents were not affected by low concentrations of verapamil, consistent with the previous report that there was no significant inhibition of Mn2+ uptake observed for Agapanthus pollen tubes in the presence of the organic channel blocker verapamil or nifedipine (Malhó et al., 1995). These two organic Ca2+ channel blockers are commonly used to block animal Ca2+ channels (Hess, 1990). The findings of this study and of Malhó et al. (1995) suggest that different types of Ca2+ channels may exist in pollen and pollen tubes from those in animal cells. In addition, we observed another type of Ca2+ channel, which was stretch-activated and Gd3+- or La3+-sensitive, in Arabidopsis and Brassica pollen protoplasts (Y.F. Wang and W.H. Wu, unpublished data). The stretch-activated PM Ca2+ channels have been proposed to be present in pollen and pollen tubes and may function in pollen germination and tube growth (Pierson et al., 1994; Malhó et al., 1995; Malhó and Trewavas, 1996). The features of the stretch-activated Ca2+ channels differ from those of the hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels in pollen and pollen tubes reported in this study. These two types of Ca2+ channels may act in concert to regulate pollen germination and tube growth.

Consistent with the results of patch-clamp experiments, we found that both F-actin-disrupting drugs and Ca2+ channel blockers affected in vitro pollen germination and pollen tube growth as well as [Ca2+]i in pollen. The only discrepancy is the effect of verapamil (50 μm), which markedly inhibited pollen germination but did not affect Ca2+ channel activity. A possible explanation could be that verapamil may inhibit pollen germination and tube growth by nonspecifically affecting some other factors instead of Ca2+ channels involved in these processes.

Do Pollen Tubes Possess the Same Type of Ca2+ Channels at Their Tips as Do Pollens?

As discussed by Sanders et al. (1999), pollen tube tips are hypersecretory, making them too difficult for patch-clamp recordings on pollen tube protoplasts. Although there is no direct evidence to demonstrate what type of Ca2+ channel exists in pollen tubes, particularly at pollen tube tips, the results presented here imply that pollen tubes may have the same type of Ca2+ channels as those in pollen. Our results showed that Ca2+ channel inhibitors and actin depolymerization reagents similarly affect the three physiological processes: both pollen germination and tube growth (Fig. 1), cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevation in pollen protoplasts and pollen tubes (Fig. 2), and Ca2+-permeable channel activity (Figs. 6–8). Since pollen germination and tube growth are a continuous and integral process, it is plausible to propose that pollen and pollen tubes use the same type of Ca2+ channels in the whole polarized process. However, direct demonstration of this notion requires patch-clamp recording of Ca2+ channel activity in the PM of pollen tubes as well as molecular cloning and functional characterization of Ca2+ channels in pollen and pollen tubes.

Cross-Talk between Dynamic F-Actin and Oscillating [Ca2+]i in Pollen Germination and Tube Growth

The tip-focused Ca2+ gradients and the actin cytoskeleton are two key factors controlling pollen germination and tube growth. It has been known for years that [Ca2+]i is highly dynamic or oscillatory at the tip of pollen tubes (Holdaway-Clarke et al., 1997; Messerli and Robinson, 1997; Messerli et al., 2000). Similarly, dynamic or oscillatory F-actin has also been shown to exist at the tip of pollen tubes (Fu et al., 2001). Interestingly, the amount of F-actin at the tip oscillates in the opposite phase with pollen tube growth and [Ca2+]i. Rop GTPase signaling has been shown to coordinate these two processes (Lin and Yang, 1997; Li et al., 1999; Fu et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2003), but the detailed regulatory mechanisms underlying these two dynamic processes, especially the regulation of Ca2+ oscillation, are not yet fully understood.

As discussed in the introduction, the involvement of actin microfilaments in ion channel regulation has been well established in animal cells (Negulyaev et al., 2000), and F-actin regulation of K+ channels has also been reported in plant cells (Hwang et al., 1997; Liu and Luan, 1998). A critical role for the actin cytoskeleton in pollen germination and tube growth (Gibbon et al., 1999; Vidali et al., 2001; this study) led us to hypothesize that actin microfilaments may function in regulating the PM Ca2+ channels during pollen germination and tube growth processes. This idea was also prompted by the observation of Fu et al. (2001) that actin dynamics at the tip of pollen tubes are in the opposite phase with pollen tube growth and Ca2+ oscillation, where [Ca2+]i reaches the highest level when F-actin reaches minimum and vice versa. Our results provide direct evidence that F-actin negatively affects Ca2+-permeable channels in pollen, representing the first example of actin regulation of Ca2+-permeable channels in plants. We found that actin depolymerization reagents CD, CB, or Lat A elevated [Ca2+]i in either pollen protoplasts or pollen tubes (Fig. 2) and activated the PM Ca2+-permeable channels (Figs. 6 and 8). On the other hand, phalloidin alone did not affect the activity of the Ca2+ channels, but pretreatment with phalloidin abolished subsequent potential CD or CB activation of the Ca2+ channels (Fig. 7). Thus, our findings can explain why F-actin oscillates in the opposite phase with [Ca2+]i (Fu et al., 2001). Moreover, actin depolymerization reagent-induced inhibition of Arabidopsis pollen germination and tube growth is dependent on [Ca2+]o. This may be explained by actin depolymerization-exerted inhibitory effects, at least in part by enhancing Ca2+ influx through PM Ca2+-permeable channels in pollen and pollen tubes. High Ca2+ has long been shown to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton in lily pollen tubes (Kohno and Shimmen, 1987). Actin-binding protein profilins sequester pollen G-actin in a Ca2+-dependent manner and are believed to contribute to actin dynamics in pollen tubes (Kovar et al., 2000; Fu et al., 2001). Interestingly, the peak of tip Ca2+ is estimated to be as high as 3 to 10 μm, falling in the range of Ca2+ concentration of 5 μm optimal for profilin-mediated G-actin sequestration (Kovar et al., 2000). Thus, as previously proposed by Fu et al. (2001), Ca2+-regulated potential oscillation of profilin-dependent G-actin sequestration could well contribute to actin dynamics at the pollen tube tip.

As discussed above and also proposed by Fu et al. (2001), there may exist an interaction or a cross-talk between actin dynamics and Ca2+ dynamics at the tip of pollen tubes. Based on this potential cross-talk, a positive loop may occur; namely, Ca2+-activated actin depolymerization may lead to further elevation of [Ca2+]i, and conversely, actin depolymerization-elevated [Ca2+]i may in turn accelerate actin depolymerization as well. However, this positive interacting loop must be limited by a negative regulatory mechanism; i.e. high [Ca2+]i feedback may inhibit Ca2+ channel-mediated extracellular Ca2+ influxes. Since Rop or Rac activates both F-actin assembly and [Ca2+]i, it is possible that this potential negative feedback mechanism may involve Ca2+ inhibition of Rop activation (Zheng and Yang, 2000). This counter-regulation of F-actin and Ca2+ at the tip may be coordinated with their potential roles in the respective regulation of secretory vesicle transport to and fusion with the tube apex. Such a spatial and temporal coordination may be critical for the rapid and directional membrane extension and wall material deposit characteristic of tip growth in pollen tubes. However, further studies are needed to understand the spatial and temporal relationship and functional interaction between the dynamic Ca2+ and F-actin at the tip of pollen tubes.

Hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+-permeable channels have been reported in other cell types in several plant species, such as tomato suspension cells (Gelli et al., 1997), Arabidopsis root hairs (Very and Davies, 2000; Foreman et al., 2003), Vicia guard cells (Hamilton et al., 2000), Arabidopsis guard cells (Pei et al., 2000), etc. Although it is difficult to quantitatively compare our data to previously reported results because of different experimental conditions as well as different types of cells, it might be plausible to postulate that those channels in different types of cells may share similar regulatory mechanisms by actins. For example, a growing root hair, similar to a growing pollen tube, is another tip-growing cell model for studying the regulation mechanism of cell growth. The tip of a growing root hair also has an oscillating calcium gradient. Interestingly, our recent results show that both inward K+ channels and Ca2+-permeable channels in root hairs of Medicago sativa are regulated by actins (L.W. Fan and W.H. Wu, unpublished data), which suggests that similar mechanisms may exist for calcium channel regulation by actin cytoskeleton in both root hairs and pollen tubes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Arabidopsis (Arabidposis thaliana) ecotype Landsberg erecta plants were grown in mixed soil in a growth chamber under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle (100 μmol m−2 s−1) and temperatures of 22°C ± 1°C and 15°C ± 4°C for daylight and night, respectively. Plants were watered twice a week with tap water, and the relative humidity was kept at approximately 70%.

In Vitro Pollen Germination Assay

In vitro Arabidopsis pollen germination experiments were conducted as described previously (Fan et al., 2001), except that the medium was slightly modified. The medium was composed of 1 mm KCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 0.8 mm MgSO4, 1.5 mm boric acid, 1% (w/v) agar, 16.6% (w/v) Suc, 3.65% (w/v) sorbitol, 10 mg L−1 myoinositol, and the pH was adjusted to 5.8 with MES-Tris. Other specific conditions were indicated in the text and the figure legends. Double distilled water was used to prepare all media. Each 1.5 mL of the heated solution (100°C, 2 min) was poured into a small petri dish (diameter = 35 mm) and cooled down to form a thin layer. The dehisced anthers were carefully dipped onto the surface of the media to make pollen grains stick to it. The dishes were incubated for 6 h in a climatic chamber (continuous light, 25°C ± 0.2°C, 100% relative humidity), frozen at −20°C for 3 min to quickly terminate the pollen germination and tube growth, and kept on ice for counting the pollen germination rate and measuring pollen tube length. All the experiments were repeated three times and at least four replicates were carried out for each treatment. For each replicate, there were no less than 400 pollen grains counted for calculation of the pollen germination rate, and approximately 80 pollen tubes were measured for their growth length. The pollen grains with emerging tubes longer than their diameter were considered as germinated.

Cytosolic Ca2+ Measurement

Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts were isolated as described previously (Fan et al., 2001). The isolated pollen protoplasts were incubated with 10 μm Fluo-3/AM in the standard washing solutions at 20°C for 30 min before Ca2+ imaging measurement. The standard washing solutions contained 1 mm KNO, 0.2 mm KH2PO4, 5 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgSO4, 1 μm KI, 0.1 μm CuSO4, 0.5 m sorbitol, 0.8 m Glc, 10 mg L−1 myoinositol, 5 mm MES, and the pH was adjusted to 5.5 with Tris. The osmolality of the standard washing solutions was 1.81 mol kg−1. The mixture was centrifuged at 160g for 5 min, and the protoplasts were resuspended in the standard washing solution. The centrifugation/resuspension cycle was conducted two times to ensure the removal of any remaining external Fluo-3/AM in the washing solutions. The protoplasts were finally resuspended in the standard washing solutions and kept on ice before use. For the cytoplasmic Ca2+ imaging of pollen tubes, Arabidopsis pollens were germinated first as described above and the germinated pollens were incubated with 10 μm Fluo-3/AM in the standard washing solutions at 20°C for 1 h before Ca2+ imaging measurement. The Fluo-3 fluorescence of the protoplasts and pollen tubes was measured with LSCM (MRC 1024, equipped with krypton/argon laser light; Bio-Rad Spectroscopy Group, Cambridge, MA). The wavelength of excitation light was 488 nm and the emission signals at 515 nm were collected. Three-dimensional scanning was conducted every 5 min with a 1.5-μm Z-series project step, and three-dimensional reconstructed images were used to show the relative [Ca2+]i.

Patch-Clamp Single-Channel Recordings

Standard single-channel recording techniques (Hamill et al., 1981) were applied in this study. For the control conditions, the external (bath) solutions contained 50 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MES (pH 5.8 with Tris), and osmolality at 1.5 mol kg−1 adjusted with sorbitol, and the internal (pipette) solutions contained 2 mm BAPTA, 0.05 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.09 mm calcium gluconate, 92 mm potassium glutamate, 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.2 with Tris), and osmolality at 1.55 mol kg−1 adjusted with sorbitol. The final free Ca2+ concentration for the internal solutions was 100 nm. The recordings were performed at room temperature (20°C ± 2°C) under dim light. Pipette capacitance was compensated for each membrane patch using the capacity compensation device of the amplifier. All data were acquired 5 min after formation of the single-channel configuration.

Single-channel currents were measured using an Axopatch-200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) that was connected to a microcomputer via an interface (TL-1 DMA Interface; Axon Instruments). pCLAMP (version 6.0.4; Axon Instruments) software was used to acquire and analyze the single-channel events. After the single-channel configuration was obtained, membrane potential (Vm) was clamped to 0 mV (holding potential). Liquid junction potentials were considered and corrected for all the data presented. Single-channel current data were filtered at 1 kHz before storage (125 μs/sample) onto a computer hard disc.

All data were presented as mean ± se. SigmaPlot software was used to analyze and plot the data.

Preparation of Stock Solutions

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis) unless otherwise indicated. CD, CB, or paclitaxel (taxol) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 20 mm, respectively, and Lat A was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 200 μm. Phalloidin was dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 20 mm. Fluo-3/AM was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 1 mm. Oryzalin was dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 100 mg mL−1. All the stock solutions were kept at −20°C before use.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (key research grant no. 39930010 and competitive grant no. 30070050 to L.M.F.), and by the Chinese National Key Basic Research Project (no. G1999011701 to W.H.W.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.104.042754.

References

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD (2000) The versatility and universality of calcium signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1: 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen J, Rutten T, Van Amstel T, de Win A, Doris F, Steer M (1995) Regulation of pollen tube growth. Acta Bot Neerl 44: 93–119 [Google Scholar]

- Doris FP, Steer MW (1996) Effects of fixatives and permeabilisation buffers on pollen tubes: implications for localisation of actin microfilaments using phalloidin staining. Protoplasma 195: 25–36 [Google Scholar]

- Fan LM, Wang YF, Wang H, Wu WH (2001) In vitro Arabidopsis pollen germination and characterization of the inward potassium channels in Arabidopsis pollen protoplasts. J Exp Bot 52: 1–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LM, Wu WH (2000) External pH regulates the inward K+ channels in the plasma membranes of Brassica pollen protoplasts. Prog Nat Sci 10: 68–73 [Google Scholar]

- Fan LM, Wu WH, Yang HY (1999) Identification and characterization of the inward K+ channel in the plasma membrane of Brassica pollen protoplasts. Plant Cell Physiol 40: 859–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijó JA, Malhó R, Obermeyer G (1995) Ion dynamics and its possible role during in vitro pollen germination and tube growth. Protoplasma 187: 155–167 [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J, Demidchik V, Bothwell JHF, Mylona P, Miedema H, Torres MA, Linstead P, Costa S, Brownlee C, Jones JDG, et al (2003) Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature 422: 442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin-Tong VE (1999) Signaling and the modulation of pollen tube growth. Plant Cell 11: 727–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin-Tong VE, Drobak BK, Allan AC, Watkins PAC, Trewavas AJ (1996) Growing of pollen tubes of Papaver rhoeas is regulated by a slow-moving calcium wave propagated by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Plant Cell 8: 1305–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin-Tong VE, Holdaway-Clarke TL, Straatman KR, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (2002) Involvement of extracellular calcium influx in the self-incompatibility response of Papaver rhoeas. Plant J 29: 333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Wu G, Yang Z (2001) Rop GTPase-dependent dynamics of tip-localized F-actin controls tip growth in pollen tubes. J Cell Biol 152: 1019–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geitmann A, Snowman BN, Emons AMC, Franklin-Tong VE (2000) Alterations in the actin cytoskeleton of pollen tubes are induced by the self-incompatibility reaction in Papaver rhoeas. Plant Cell 12: 1239–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelli A, Higgins VJ, Blumwald E (1997) Activation of plant plasma membrane Ca2+-permeable channels by race-specific fungal elicitors. Plant Physiol 113: 269–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ (1999) Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell 11: 2349–2364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griessner M, Obermeyer G (2003) Characterization of whole-cell K+ currents across the plasma membrane of pollen grain and tube protoplasts of Lilium longiflorum. J Membr Biol 193: 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Vernoud V, Fu Y, Yang Z (2003) ROP GTPase regulation of pollen tube growth through the dynamics of tip-localized F-actin. J Exp Bot 54: 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ (1981) Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch 391: 85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DWA, Hills A, Kohler B, Blatt MR (2000) Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4967–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsper JPFG, Heemskerk JWM, Veerkamp JH (1987) Cytosolic and particulate phosphotidylinositol phospholipase C activities in pollen tubes of Lilium longiflorum. Plant Physiol 71: 120–126 [Google Scholar]

- Hess P (1990) Calcium channels in vertebrate cells. Annu Rev Neurosci 13: 337–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway-Clarke TL, Feijo JA, Hackett GR, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (1997) Pollen tube growth and the intracellular cytosolic calcium gradient oscillate in phase while extracellular calcium influx is delayed. Plant Cell 9: 1999–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway-Clarke TL, Hepler PK (2003) Control of pollen tube growth: role of ion gradients and fluxes. New Phytol 159: 539–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horber JK, Mosbacher J, Haberle W, Ruppersberg JP, Sakmann B (1995) A look at membrane patches with a scanning force microscope. Biophys J 68: 1687–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JU, Suh S, Yi HJ, Kim J, Lee Y (1997) Actin filaments modulate both stomatal opening and inward K+-channel activities in guard cells of Vicia faba L. Plant Physiol 115: 335–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe LA, Weisenseel MH, Jaffe LF (1975) Calcium accumulation within the growing tips of pollen tubes. J Cell Biol 67: 488–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T, Shimmen T (1987) Ca2+-induced F-actin fragmentation in pollen tubes. Protoplasma 141: 177–179 [Google Scholar]

- Kost B, Spielhofer P, Chua NH (1998) A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J 16: 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Drobak BK, Staiger CJ (2000) Maize profilin isoforms are functionally distinct. Plant Cell 12: 583–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhtreiber WM, Jaffe LF (1990) Detection of extracellular calcium gradients with a calcium-specific vibrating electrode. J Cell Biol 110: 1565–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancelle SA, Cresti M, Hepler PK (1987) Ultrastructure of the cytoskeleton in freeze-substituted pollen tubes of Nicotiana altata. Protoplasma 140: 141–150 [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lin YK, Heath RM, Zhu MX, Yang ZB (1999) Control of pollen tube tip growth by a Rop GTPase-dependent pathway that leads to tip-localized calcium influx. Plant Cell 11: 1731–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Yang Z (1997) Inhibition of pollen tube elongation by microinjected anti-Rop1Ps antibodies suggests a crucial role for Rho-type GTPases in the control of tip growth. Plant Cell 9: 1647–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Luan S (1998) Voltage-dependent K+ channel as targets of osmosensing in guard cells. Plant Cell 10: 1957–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhó R (1998) Expanding tip growth theory. Trends Plant Sci 3: 40–42 [Google Scholar]

- Malhó R, Read ND, Trewavas AJ, Pais MS (1995) Calcium channel activity during pollen tube growth and reorientation. Plant Cell 7: 1173–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhó R, Trewavas AJ (1996) Localized apical increases of cytosolic free calcium control pollen tube orientation. Plant Cell 8: 1935–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli MA, Creton R, Jaffe LF, Robinson KR (2000) Periodic increases in elongation rate precede increases in cytosolic Ca2+ during pollen tube growth. Dev Biol 222: 84–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli MA, Danuser G, Robinson KR (1999) Pulsatile influxes of H+, K+ and Ca2+ lag growth pulses of Lilium longiflorum pollen tubes. J Cell Sci 112: 1497–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli M, Robinson KR (1997) Tip localized Ca2+ pulses are coincident with peak pulsatile growth rates in pollen tubes of Lilium longiforum. J Cell Sci 110: 1269–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DD, Callaham DA, Gross DJ, Hepler PK (1992) Free Ca2+ gradient in growing in growing pollen tubes of Lilium. J Cell Sci 101: 7–12 [Google Scholar]

- Miller DD, Lancelle SA, Hepler PK (1996) Actin microfilaments do not form a dense meshwork in Lilium longiflorum pollen tube tips. Protoplasma 195: 123–132 [Google Scholar]

- Negulyaev YA, Khaitlina SY, Hinssen H, Shumilina EV, Vedernikova EA (2000) Sodium channel activity in leukemia cells is directly controlled by actin polymerization. J Biol Chem 275: 40933–40937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer G, Kolb HA (1993) K+ channels in the plasma membrane of Lily pollen protoplasts. Bot Acta 106: 26–31 [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z, Schroeder JI, Schwarz M (1998) Background ion channel activities in Arabidopsis guard cells and review of ion channel regulation by protein phosphorylation events. J Exp Bot 49: 319–328 [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klusener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI (2000) Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406: 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson ES, Miller DD, Callaham DA, Shipley AM, Rivers BA, Cresti M, Hepler PK (1994) Pollen tube growth is coupled to the extracellular calcium ion flux and the intracellular calcium gradient: effect of BAPTA-type buffers and hypertonic media. Plant Cell 6: 1815–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson ES, Miller DD, Callaham DA, van Aken J, Hackett G, Hepler PK (1996) Tip-localized calcium entry fluctuates during pollen tube growth. Dev Biol 174: 160–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineros M, Tester M (1997) Calcium channels in higher plant cells: selectivity, regulation and pharmacology. J Exp Bot 48: 551–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore KS, Cork RJ, Robinson KR (1991) A cytoplasmic gradient of Ca2+ is correlated with the growth of lily pollen tubes. Dev Biol 148: 612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd JJ, Franklin-Tong VE (1999) Calcium signaling in plants. Cell Mol Life Sci 55: 214–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D, Brownlee C, Harper JF (1999) Communicating with calcium. Plant Cell 11: 691–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger CJ (2000) Signaling to the actin cytoskeleton in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 51: 257–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger CJ, Yuan M, Valenta R, Shaw PJ, Warn RM, Lloyd CW (1994) Microinjected profilin affects cytoplasmic streaming in plant cells by rapidly depolymerizing actin microfilaments. Curr Biol 4: 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer MW, Steer JM (1989) Pollen tube tip growth. New Phytol 111: 323–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LP, Hepler PK (1997) Pollen germination and tube growth. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 461–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Very AA, Davies JM (2000) Hyperpolarization-activated calcium channels at the tip of Arabidopsis root hairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9801–9806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Hepler PK (2000) Actin in pollen and pollen tubes. In CJ Staiger, F Baluska, D Volkmann, PW Barlow, eds, Actin: A Dynamic Framework for Multiple Plant Cell Functions. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 323–345

- Vidali L, McKenna ST, Hepler PK (2001) Actin polymerization is essential for pollen tube growth. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2534–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZL, Yang Z (2000) The Rop GTPase switch turns on polar growth in pollen. Trends Plant Sci 5: 298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]