Abstract

We identify a human mutation (E1053K) in the ankyrin-binding motif of Nav1.5 that is associated with Brugada syndrome, a fatal cardiac arrhythmia caused by altered function of Nav1.5. The E1053K mutation abolishes binding of Nav1.5 to ankyrin-G, and also prevents accumulation of Nav1.5 at cell surface sites in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Ankyrin-G and Nav1.5 are both localized at intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes in cardiomyocytes, and Nav1.5 coimmunoprecipitates with 190-kDa ankyrin-G from detergent-soluble lysates from rat heart. These data suggest that Nav1.5 associates with ankyrin-G and that ankyrin-G is required for Nav1.5 localization at excitable membranes in cardiomyocytes. Together with previous work in neurons, these results in cardiomyocytes suggest that ankyrin-G participates in a common pathway for localization of voltage-gated Nav channels at sites of function in multiple excitable cell types.

Keywords: arrhythmia, SCN5A, targeting, trafficking, sudden cardiac death

Voltage-gated Na (Nav) channels initiate rapid and highly coordinated waves of depolarization that are essential for rhythmic beating of the heart (1). Mutations in Nav1.5 (encoded by SCN5A), the major voltage-gated Na+ channel isoform in adult heart, can cause a dominantly inherited cardiac arrhythmia known as Brugada syndrome (2). Brugada syndrome is characterized by incomplete right bundle branch block and increased risk of sudden cardiac death as a result of ventricular fibrillation (2).

Ability of Nav1.5 to generate physiologically effective action potentials is determined by its cellular localization as well as its channel properties. Nav1.5 is concentrated at intercalated discs, which are specialized sites of contact between cardiomyocytes and are enriched in gap junctions. Proximity of Nav1.5 to gap junctions, which provide rapid ion exchange between adjacent cells, allows efficient transcellular propagation of the action potential. In addition, Nav1.5 is localized in cardiomyocyte T-tubules adjacent to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and thus is well positioned to initiate the calcium-induced calcium release that triggers contraction (3, 4).

Although little is known about the mechanism for strategic targeting of Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes, clustering of voltage-gated Na channels in the nervous system at axon initial segments requires association with ankyrin-G. Targeted knockout of ankyrin-G in the mouse cerebellum abolishes restriction of Nav1.6 and 1.2 to axon initial segments of Purkinje and granule cell neurons (5, 6). Ankyrin-G associates with the pore-forming α-subunit of Nav1.2 through a 9-aa motif on loop 2 (VPIAL-GESD; refs. 7 and 8). This sequence is required for association between ankyrin-G and Nav1.2, and for targeting of Nav1.2 to axon initial segments of cultured hippocampal neurons (7, 8). Nav1.5 contains a nearly identical sequence in loop 2 (see Fig. 2 A; VPIAVAESD), suggesting that Nav1.5 also could associate with ankyrin-G. Here we report the interaction and colocalization of Nav1.5 and 190-kDa ankyrin-G in heart, and present evidence that a human Nav1.5 mutation associated with Brugada syndrome that blocks ankyrin-G binding, also disrupts Nav1.5 surface expression in cardiomyocytes.

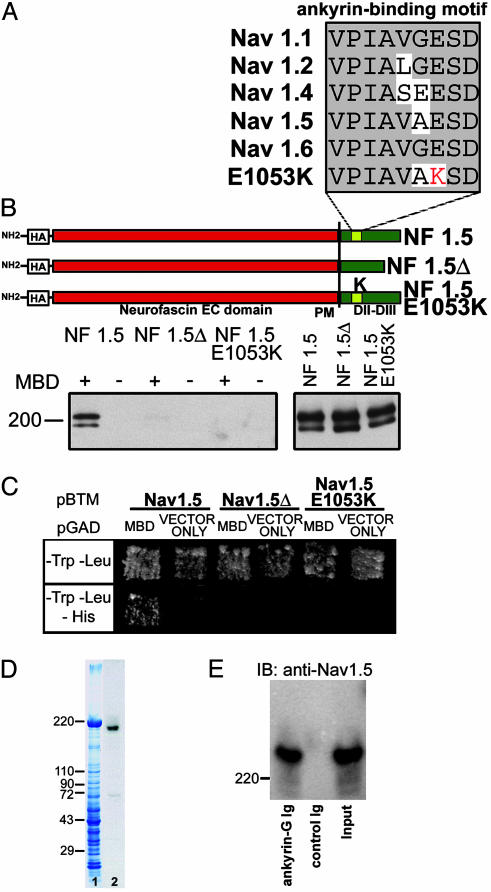

Fig. 2.

Human SCN5A mutation E1053K eliminates interaction with ankyrin-G. (A) Alignment of ankyrin-binding motif from Nav1.2 with other Nav isoforms. Bottom is Nav1.5 amino acid alignment from human with Brugada syndrome (E1053K). (B) NF/Nav1.5 chimeras. A diagram of NF/Nav1.5 chimeras using loop 2 sequence from Nav1.5, Nav1.5Δ (deletion of VPIAVAESD), or Nav1.5 E1053K mutant is shown. Constructs were expressed in baby hamster kidney cells and lysates incubated with GST-AnkG MBD(+)- or GST(–)-conjugated beads. Bound protein (Left) or 6% of total lysate used (Right) was analyzed by immunoblotting with HA-specific antibodies. The doublet observed in immunoblots represents both glycosylated and nonglycosylated forms of NF/Nav1.5 chimeras in total cell lysates (23). (C) Saccharomyces cerevisiae was cotransformed with pBTM116-Nav1.5, pBTM116-Nav1.5Δ, or pBTM116-Nav1.5 E1053K, and pGAD424 alone, and pGAD424-MBD. Cotransformants were selected on –LT media and then tested for HIS3 reporter gene activation. (D) 190-kDa ankyrin-G associates with Nav1.5 in vivo. Lane 1, Coomassie blue stained gel of rat heart lysate. Lane 2, immunoblot analysis of lane 1 by using ankyrin-G polyclonal Ig. (E) Adult rat ventricle detergent-soluble lysate was incubated with affinity-purified ankyrin-G Ig conjugated to beads or control Ig alone. Bound protein was eluted and analyzed by immunoblot analysis using Nav1.5-specific antibody (SH1). Input, 20% of soluble protein.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies. Affinity-purified ankyrin-G polyclonal antibody was generated against recombinant 190-kDa ankyrin-G death domain/regulatory domain. The protein was injected into rabbits and sequentially adsorbed by (i) GST-affinity column, (ii) ankyrin-B C-terminal affinity column, and (iii) affinity isolation by using an ankyrin-G C-terminal affinity column. Ankyrin-G Ig was used at 0.5 μg/ml (IF) and 0.25 μg/ml (IB). Other antibodies include mouse anti-connexin 43 (2 μg/ml, Chemicon), goat anti-desmoplakin (2 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-ZO-1 (1 μg/ml, Zymed), goat and rabbit anti-N-cadherin (2 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-β-catenin (2 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Nav1.5-specific antibodies SH1 (IB, 1 μg/ml; IF, 2 μg/ml, a generous gift from William Catterall, University of Washington, Seattle; ref. 9) and hH1 (2 μg/ml, Alomone), and affinity-purified hemagglutinin (HA) monoclonal antibody (2 μg/ml). Nav1.5 antibodies were tested by using WT HEK293 cells or HEK293 cells expressing Nav1.5. For both Nav1.5 antibodies (SH1, hH1) we observed intercalated disk and T-tubule staining.

Lentiviral Expression. HA Nav1.5 and HA Nav1.5 E1053K were TOPO-cloned into pLenti6 V5-D for expression in cardiomyocytes by using Virapower Expression system (Invitrogen). PLenti6 HA/V5 Nav1.5 and HA/V5 Nav1.5 E1053K were cotransfected with pLP1, pLP2, and pLP/VSVG (packaging plasmids) into 293FT cells (5 × 106 cells) by using Lipofectamine. After 24 h, the medium was replaced. Seventy-two hours after transfection, 293FT cell supernatants were harvested, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and titered by using serial-dilutions of the virus on NIH 3T3 cells to determine the number of Blasticidin-resistant colonies. Because of the large size of Nav1.5, viral titers were low. Equal titers of WT or mutant viral supernatants were added to freshly isolated adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes for 18 h. Three days after transduction (4-day-old cells), cardiomyocytes were lysed to determine relative expression of HA/V5 Nav1.5 and HA/V5 Nav1.5 E1053K. Three days after transduction (4-day-old cells), cells were detached from the plates and protein localization was determined by immunofluorescence.

Expression of Recombinant Na+ Channels. Na channels were expressed in HEK293 cells as described (10). Briefly, transient transfection was carried out with equal amounts of Na+ channel α-subunit cDNA (WT or mutant, EK), and hβ1 cDNA subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (total cDNA, 2.5 μg). In addition the same amount of CD8 cDNA was cotransfected as reporter gene. Expression of channels was studied by using patch clamp procedures 48 h after transfection. Targeting assays were performed as above by using HA-tagged Nav channel constructs.

Adult Rat Cardiomyocyte Isolation. Animal care was in accordance with institutional guidelines. Adult cardiomyocytes were prepared as described (11). Cells were cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml insulin, 0.55 μg/ml transferrin, 0.5 ng/ml selenium, and 10 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime (Sigma; ref. 12).

Electrophysiology. Membrane currents were measured by using whole cell patch-clamp, with Axopatch 200B amplifiers (Axon Instruments). All measurements were obtained at room temperature (22°C). Macroscopic whole cell Na+ current was recorded by using published solutions and protocols (10). pclamp8 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), excel (Microsoft), and origin 6.1 (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA) were used for data acquisition and analysis. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student's t test was used to compare means; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Immunoprecipitations. See Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Immunostaining. Freshly isolated or cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes were fixed in cold ethanol (for permeabilized protocol) or 2% paraformaldehyde (for nonpermeabilized protocol) for 20 min. Cells were centrifuged 2 min at 200 × g and washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4). Cells were blocked for 3 h in PBS with 0.025% Triton X-100/3% fish oil gelatin. Cells were stained overnight in primary antibody (in blocking buffer) at 4°C on a rotating platform. Cells were washed as above in blocking buffer. Cells were incubated in secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, 568, and 633) for 12 h at 4°C in blocking buffer. After washes, buffer was removed and the pellet was resuspended in Vectashield and plated onto Mattek 35-mm plates. For the nonpermeabilized cell staining protocol, staining was performed at 4°C and detergent was not included in any buffer. We also performed permeabilized cell staining (HA antibody) in parallel with nonpermeabilized staining to confirm that cells were expressing the lentiviral-expressed WT and mutant HA-Nav1.5. Images were collected on Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope (see details on image collection and processing in Supporting Text).

Nav1.5 Constructs and Mutagenesis. Full-length human Nav1.5 cDNA was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 and sequenced to verify that there were no mutations. DNA coding for an HA epitope (YPYDVPDYA) was engineered in-frame into the extracellular S5–S6 loop of Nav1.5 domain 1 by using QuikChange mutagenesis. This construct was used to generate Nav1.5 with human Brugada mutation E1053K by QuikChange mutagenesis. WT and mutant HA-tagged cDNAs were PCR-amplified and Topo-cloned into pLenti6/V5 (Invitrogen), and the complete cDNAs (≈12 kb) were sequenced to confirm that no mutations were introduced by PCR. NF/Nav1.5 chimeras were created as described in ref. 7 by using loop 2 from Nav1.5 instead of Nav1.2. The WT chimera was then altered by mutagenesis to create HA NF-Nav1.5Δ and HA NF-Nav1.5 E1053K.

Results

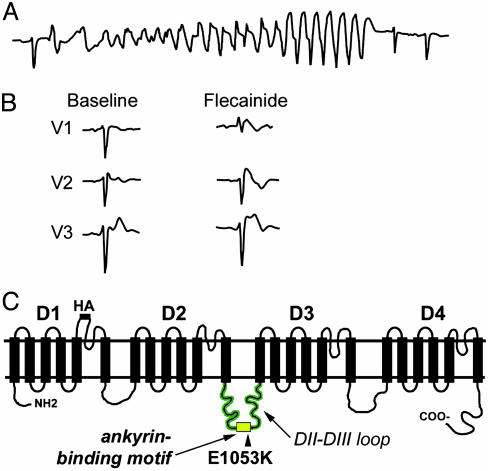

Brugada Syndrome Associated with Human SCN5A E1053K Mutation. We identified a de novo SCN5A mutation in a 47-year-old female with a history of palpitations with an unexplained syncopal spell occurring at rest. Runs of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia were observed at the arrival to the emergency room (Fig. 1A). Baseline ECG was within normal limits with the exception of a 1-mm ST segment elevation in lead V1 and incomplete right bundle branch block (Fig. 1B). No cardiac abnormalities were observed by echocardiogram, and programmed electrical stimulation did not induce any clinically significant arrhythmias. The diagnosis of Brugada syndrome was established by an i.v. flecainide test, which revealed an abnormal response with the induction of a 3-mm ST segment elevation in leads V1–V2 and a typical coved type morphology (2). An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was positioned. No ICD shock has been delivered at 3-year follow up, and no ventricular arrhythmias were detected.

Fig. 1.

Brugada syndrome associated with SCN5A E1053K mutation. (A) ECG monitor strip of the index patient carrier of the E1053K mutation showing self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia recorded at the arrival to the emergency room. (B) ECG recordings in leads V1–V3 of the index patient carrier of the E1053K mutation at baseline and during i.v. flecainide administration (2 mg/kg in 10 min). (C) Human Nav1.5 proposed secondary structure. Potential ankyrin-binding motif is located in loop 2. Human Brugada mutation E1053K is located within these nine amino acids.

All exons of SCN5A in this individual were analyzed by DHPLC and direct DNA sequencing. A single G-to-A nucleotide transition (G3157A) was identified leading to substitution of a highly conserved glutamic acid with lysine (E1053K). Interestingly, this mutation is localized in the predicted 9-aa ankyrin-binding motif in the DII–III loop of Nav1.5 (VPIAVX[E → K]SD) (Figs. 1C and 2A). Given that the E1053K mutation is associated with Brugada syndrome and Brugada syndrome is caused by altered or aberrant function of Nav1.5, the E1053K mutation also causes aberrant Nav1.5 function in vivo. However, the E1053 residue is not located near predicted channel pore-forming regions or voltage-sensor, and is not found in the III-IV linker implicated in fast inactivation (13). Nevertheless, the DII–III loop may directly affect the Nav1.5 channel activation voltage, as suggested by a recent report studying Nav1.4/Nav1.5 channel chimeras (14).

Human SCN5A Mutation E1053K Eliminates Nav1.5 Interaction with Ankyrin-G. We performed in vitro binding assays to determine whether ankyrin-G associates with Nav1.5. A HA-tagged chimera of the extracellular and transmembrane domain of neurofascin (NF) fused with loop 2 of Nav1.5 (see Fig. 2B) was expressed in baby hamster kidney cells. Detergent-soluble lysates from these cells were incubated with immobilized GST-ankyrin-G membrane-binding domain (MBD) or GST alone. Bound protein was examined by immunoblotting using HA antibody. Like HA NF-Nav1.2 loop 2 (7), HA NF-Nav1.5 loop 2 associates with GST-MBD but not GST alone (Fig. 2B).

We next determined whether the VPIAVAESD motif in loop 2 (Fig. 2B) is necessary for ankyrin-G/Nav1.5 binding. A HA-NF-Nav1.5 mutant chimera was created that lacked the VPIAVAESD motif (NF-Nav1.5 loop 2Δ; Fig. 2B). Although it is expressed at similar levels as the WT chimera, NF-Nav1.5 loop 2Δ did not associate with ankyrin-G MBD (Fig. 2B). Additionally, ankyrin-G MBD associates with Nav1.5 loop 2 but not Nav1.5 loop 2Δ in yeast two-hybrid assays (Fig. 2C). Therefore, similar to results with Nav1.2 in neurons (7), interaction of Nav1.5 with ankyrin-G membrane-binding domain requires the VPI-AXXESD motif in loop 2.

We introduced the human E1053K mutation into HA NF-Nav1.5 to evaluate the effect of this mutation on ankyrin-G binding. HA NF-Nav1.5 loop 2 E1053K did not associate with ankyrin-G MBD even though the mutant chimera was expressed at similar levels as the WT chimera (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed when ankyrin-G MBD and Nav1.5 loop 2 E1053K were used in yeast two-hybrid assays (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the mutation E1053K associated with Brugada syndrome also abolishes interaction between Nav1.5 and ankyrin-G.

Ankyrin-G Associates with NaV1.5 in Heart Tissue. We determined the ankyrin-G isoform(s) expressed in heart by using an affinity-purified antibody (see Materials and Methods). Immunoblot analysis using this Ig revealed that 190-kDa ankyrin-G is the predominant ankyrin-G isoform in adult rat heart (Fig. 2D) as well as adult mouse heart (data not shown). In contrast, 107-kDa ankyrin-G, which is the predominant ankyrin-G isoform in skeletal muscle (15, 16), was present at low levels.

The ability of 190-kDa ankyrin-G and Nav1.5 to associate in heart was evaluated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Detergent-soluble lysates from adult rat heart were incubated with affinity-purified ankyrin-G Ig coupled to protein G Sepharose. After extensive washes, protein specifically bound to the beads was eluted and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting using affinity-purified Nav1.5 antibody (SH1). Ankyrin-G coimmunoprecipitates a significant fraction (≈10%) of total soluble Nav1.5 (Fig. 2E). Therefore, ankyrin-G associates with the α-subunit of the voltage-gated Nav channels in heart (Nav1.5, Fig. 2E) as well as brain (Nav1.2 and Nav1.6; refs. 5, 6, and 8).

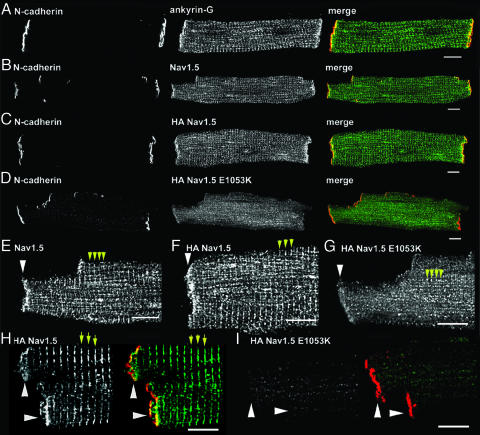

Ankyrin-G and NaV1.5 Are Localized at Intercalated Disc and T-Tubule Membranes. Nav1.5 is concentrated primarily at intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes in ventricular cardiomyocyte (refs. 9 and 17, see also Fig. 3B). Ankyrin-G localization in adult ventricle was assessed by using confocal imaging of adult rat isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes using ankyrin-G affinity-purified polyclonal Ig. Like Nav1.5, ankyrin-G is highly expressed at ventricular intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the localization of 190-kDa ankyrin-G and Nav1.5 at intercalated discs and in T-tubules in ventricular cardiomyocytes is consistent with an in vivo interaction between these proteins.

Fig. 3.

One hundred ninety-kilodalton ankyrin-G is coexpressed with Nav1.5 at intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes and Nav1.5 E1053K mutant is mislocalized from intercalated disc/T-tubule membrane of cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes. (A) Ankyrin-G localization (green) at intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes of adult rat cardiomyocytes colabeled with N-cadherin (red). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) Nav1.5 localization (green, SH1 antibody) at intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes of adult rat cardiomyocytes colabeled with N-cadherin (red). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) Localization of N-cadherin (red) and lentiviral-expressed WT HA-Nav1.5 (green, HA antibody) in 4-day cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes. (D) Localization of N-cadherin (red) and lentiviral-expressed WT HA-Nav1.5 E1053K (green, HA antibody) in 4-day-old adult rat cardiomyocytes. (E–G) High-magnification image of intercalated disk region of above images. Intercalated disc marked by arrowhead. T-tubules are denoted by yellow arrows. Note small puncta near T-tubules in HA Nav1.5 E1053K-transduced cell. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (H) Localization of N-cadherin (red) and lentiviral-expressed WT HA-Nav1.5 (green, HA antibody) in nonpermeabilized 4-day cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes. Intercalated disc is marked by arrowhead. T-tubules are denoted by yellow arrows. (I) Localization of N-cadherin (red) and lentiviral-expressed WT HA-Nav1.5 E1053K in nonpermeabilized 4-day cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes. (Scale bar for H and I, 10 μm.)

Nav1.5 E1053K Is Not Expressed at the Membrane Surface of Cardiomyocytes. The effect of the E1053K mutation on cellular localization of Nav1.5 was assessed by expression of WT Nav1.5 and Nav1.5 E1053K in isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes. Full-length human Nav1.5 cDNA was engineered to contain an extracellular HA epitope (S5–S6 linker) at a site previously shown to not affect channel localization or gating (HA Nav1.5, see Fig. 1C) (18). HA-Nav1.5 E1053K was also created by using site-directed mutagenesis. Each plasmid was completely sequenced (≈12 kb) to ensure that no additional mutations were introduced. Both cDNAs were cloned into a lentiviral expression plasmid, and lentivirus corresponding to both cDNAs was generated and titered. Ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from adult rat hearts and transduced with virus containing either HA-Nav1.5 or HA-Nav1.5 E1053K. At 2 days after transduction (3-day-old cells), both proteins are made with the correct molecular weight and at equivalent levels (data not shown). Localization of each protein in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes was determined in 4-day-old cardiomyocytes by using affinity-purified HA antibody. Isolated 4-day cultured adult cardiomyocytes transduced with lentivirus maintain viability based on the following criteria: First, transduced and nontransduced adult cultured cardiomyocytes can “round up” after 3–4 days in culture. Therefore, we only analyzed cardiomyocytes with normal rod-shaped morphology. Second, transduced cardiomyocytes normally target intercalated disc, T-tubule, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and other cardiomyocyte proteins including desmoplakin, ZO-1, β-catenin, N-cadherin, ryanodine receptor 2, SERCA2, α-actinin, and endogenous Nav1.5 (Fig. 3B and Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Third, we observed no significant differences in endogenous Nav1.5 expression by immunoblot or immunofluorescence after 1–4 days in culture (data not shown).

Virally expressed HA-Nav1.5, like endogenous Nav1.5, is expressed on the membrane surface of nonpermeabilized cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3H) and is targeted to both intercalated disc and T-tubule domains (Fig. 3 B, C, E, and F). In contrast, HA-Nav1.5 E1053K is minimally expressed on the surface membrane of nonpermeabilized cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3I), and correspondingly is nearly absent from intercalated disc and T-tubule membranes (Fig. 3 D and G). Instead, HA-Nav1.5 E1053K staining of permeabilized cells is limited to small longitudinally oriented puncta throughout the cardiomyocyte (Fig. 3G). These puncta are not evident in nonpermeabilized cells and, therefore, may represent intermediates between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, or potentially post-Golgi intermediates normally destined for intercalated disc or T-tubule membranes. Therefore, the Nav1.5 E1053K mutation associated with Brugada syndrome eliminates ankyrin-G binding, and abolishes normal accumulation of the channel at the cell surface of transfected cardiomyocytes.

Nav1.5 E1053K Displays Altered Channel Properties in HEK293 Cells. One explanation for the loss of Nav1.5 E1053K at the membrane surface of cardiomyocytes is the possibility that E1053K represents a key structural mutation that significantly affects Nav1.5 folding and stability. We assessed this possibility by comparing expression and electrophysiological properties of Nav1.5 and Nav1.5 E1053K expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. In contrast to cardiomyocytes, HEK293 cells efficiently target both transfected Nav1.5 and Nav1.5 E1053K to the plasma membrane. In fact, we observed no significant difference in Nav1.5 and Nav1.5 E1053K current density in HEK293 cells (data not shown). Therefore, the E1053K mutation is likely not a gross structural mutation that affects the folding and/or the stability of the channel.

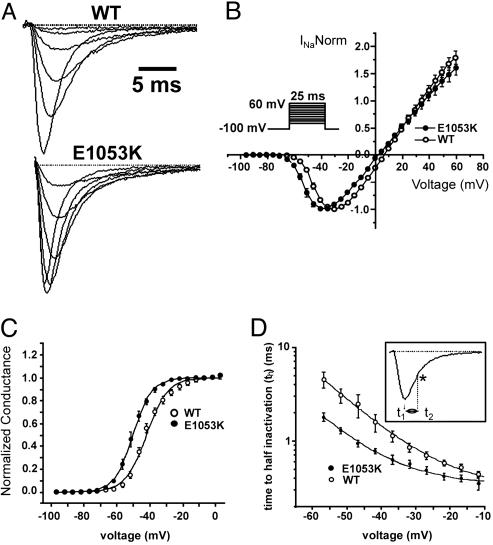

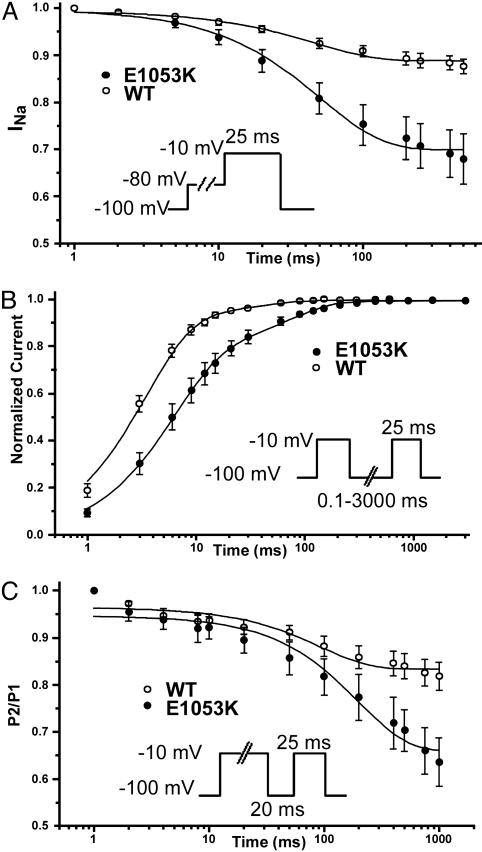

Interestingly, although displaying similar current density as the WT channel, Nav1.5 E1053K expressed in cultured HEK293 cells displays abnormal channel properties. Specifically, we observed a significant hyperpolarizing shift of the E1053K mutant channel activation curve [V1/2 =–41.8 ± 1 mV, k = 6.4 ± 0.6 for the WT, n = 7; V1/2 = –50.1 ± 1.2 mV (P = 0.002), k = 5.5 ± 0.1 for E1053K, n = 5; Fig. 4), that reveals that Nav1.5 E1053K channel activates at more negative potentials (WT –55 mV vs. E1053K –69 mV; P = 0.0021). Additionally, Nav1.5 E1053K expressed in HEK293 cells displays a faster onset of inactivation (measured as time to half activation), and slower recovery from inactivation compared to WT Nav1.5. A 4-mV negative shift of the steady state inactivation was observed for Nav1.5 E1053K [WT, V1/2 = –68.9 ± 0.3, k = 5.6 ± 0.2, n = 15; E1053K: V1/2 =–73.6 ± 0.1 (P = 6.9E-5), k = 6.3 ± 0.1, n = 13) because of a significant preferential transition into the close-state inactivation (Fig. 5). These observations indicate that Brugada mutation E1053K affects Nav1.5 channel properties. Because HEK293 cells express 190-kDa ankyrin-G (data not shown), these observations suggest a possibility that association of ankyrin-G with Nav1.5 may also modulate channel properties. Alternatively, the E1053K mutation could have a direct affect on Nav1.5 channel properties independent of ankyrin-G activity. It will be of interest in the future to explore effects of ankyrin-G on Nav1.5 under conditions where ankyrin-G can be removed and reconstituted.

Fig. 4.

WT Nav1.5 and Nav1.5 E1053K voltage dependence of activation and kinetics of inactivation. (A) Averaged and normalized current traces recorded from WT (n = 33) and E1053K mutant channel (n = 18) obtained by applying depolarizing steps (–45 mV, –40 mV, –35 mV, –20 mV, –15 mV) for 25 ms. (B) Normalized current–voltage relationship for WT and E1053K recorded in 10 mM Na+ (n = 5 for WT, n = 5 for E1053K). The protocol is shown in the Inset. (C) Steady-state activation curve obtained by normalizing the peak current for the conductance over a range of voltages from –100 mV to 15 mV (n = 5 for WT and n = 5 for E1053K). Data are fitted with a Boltzmann function. (D) Kinetics of the onset of inactivation measured as time to half-inactivation. Given t1 as the time to the maximum peak and t2 as the time to 50% of current inactivation (*), th = (t2 – t1). See Inset for protocol.

Fig. 5.

Nav1.5 E1053K displays abnormal inactivation properties compared to WT Nav1.5. (A) The transition in the close-state inactivation is favored for the E1053K mutant channel respect to WT (n = 13 for WT, n = 11 for E1053K). (B) The recovery from fast inactivation is slower in the E1053K channel compared to the WT channel (n = 9 for WT, n = 6 for E1053K). (C) Enhancement of the intermediate inactivation state for Nav1.5 E1053K compared to WT Nav1.5 (n = 10 for WT, n = 5 for E1053K). After 200 ms, there is 64% available for E1053K vs. 83% of the WT. In each panel, see Inset for protocol.

Discussion

This study identifies a human mutation (E1053K) in the ankyrin-binding motif of Nav1.5 that is associated with Brugada syndrome, a fatal cardiac arrhythmia caused by altered function of Nav1.5. The E1053K mutation does not affect channel expression and ability to generate voltage-sensitive current in HEK293 cells and thus does not grossly perturb Nav1.5 folding, processing through the Golgi, or function. However, the E1053K mutation does abolish binding of Nav1.5 to ankyrin-G, and also prevents accumulation of Nav1.5 at cell surface sites in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Moreover, we also report that ankyrin-G and Nav1.5 are both localized intercalated discs and T-tubule membranes in cardiomyocytes, and that Nav1.5 coimmunoprecipitates with 190-kDa ankyrin-G from detergent-soluble lysates from rat heart. It is possible that the E1053K mutation affects activities of the channel in addition to ankyrin-G binding. However, the most parsimonious interpretation of the data considered together is that Nav1.5 associates with ankyrin-G and that ankyrin-G is required for cell surface expression of Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. The ankyrin-G-binding motif (VPIAXX-ESD) is conserved among Nav1.1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6, and also is required for Nav channel targeting in both neurons (7, 8). Therefore, an ankyrin-G-based mechanism for Nav channel targeting appears a conserved feature of both cardiomyocytes and neurons. Ankyrin-G may also be required for targeting of Nav1.1 to specialized sites in neurons and of Nav1.4 to the neuromuscular junction in skeletal muscle. It is of interest in this regard that ankyrin-G is located at the neuromuscular junction in the postsynaptic domain enriched in Nav channels (16, 19, 20).

The pathway for restricting/targeting of Nav1.5 or other Nav channels to the cell surface apparently operates in a cell-specific manner. As noted above, the E1053K mutation, or deletion of the 9-aa ankyrin-binding motif (Fig. 2 A) does not block targeting of Nav1.5 to the cell surface of HEK293 cells (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Moreover, delivery of Nav1.2 to unmyelinated axons of granule cell neurons is unaffected by the absence of ankyrin-G (5), and Nav1.2 lacking the ankyrin-binding motif is also efficiently targeted to the plasma membrane of HEK293 cells (Fig. 7). An additional targeting motif responsible for endocytosis from dendritic membranes has been identified in Nav1.2 (21). The distinct trafficking profile of Nav1.5 in cardiac myocytes compared to HEK293 cells suggests the presence of highly specialized protein targeting machinery in heart. In the future, it will be important to use differentiated cardiomyocytes and neurons to evaluate the molecular mechanisms for Nav channel targeting to specialized domains such as intercalated discs and axon initial segments.

The lack of surface expression of Nav1.5 E1053K in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes suggests that patients heterozygous for the SCN5A G3157A (E1053K) mutation would not display a full complement of Nav1.5. Reduction in the number of Nav1.5 channels could result in Brugada syndrome, which occurs in patients heterozygous for mutations causing loss of Nav1.5 activity. Our functional data demonstrate that the Nav1.5 E1053K mutation also affects Nav1.5 channel properties (Fig. 5). Therefore, although the majority of Nav1.5 E1053K does not reach the membrane surface of cardiomyocytes, we cannot exclude the possibility that residual Nav1.5 E1053K may reach the cell surface. Enhanced inactivation of these residual channels, as demonstrated by our findings, could further contribute to the Brugada phenotype because of an additional reduction in sodium current.

In summary, this study provides evidence consistent with the possibility that ankyrin-G participates in an unsuspected common pathway for restricting/targeting Nav channels to plasma membrane sites in cardiomyocytes as well as initial segments of nerve axons. An unresolved question for the future is whether ankyrin-G acts solely as a localized scaffolding protein that stabilizes Nav1.5 at specialized sites once it is delivered to the plasma membrane, or whether ankyrin-G also has a role in sorting and trafficking of these channels. The recent finding that ankyrin-G is required for biogenesis of the lateral membrane domain of epithelial cells (22) suggests functions for ankyrin-G that go beyond simple scaffolding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a focused giving grant from Johnson and Johnson (to V.B. and P.J.M.), Telethon Grant P0227/01, “Ricerca Finalizzata” DG-RSVE-RF2001-1862, and Cariplo Foundation Grant 2001.3009/10.9079 (to C.N., I.R., and S.G.P.), and National Institutes of Health Grant R01NS36637 (to S.L.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Nav, voltage-gated Na; HA, hemagglutinin; NF, neurofascin; MBD, membrane-binding domain.

References

- 1.Papadatos, G. A., Wallerstein, P. M., Head, C. E., Ratcliff, R., Brady, P. A., Benndorf, K., Saumarez, R. C., Trezise, A. E., Huang, C. L., Vandenberg, J. I., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6210–6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priori, S. G., Napolitano, C., Gasparini, M., Pappone, C., Della Bella, P., Giordano, U., Bloise, R., Giustetto, C., De Nardis, R., Grillo, M., et al. (2002) Circulation 105, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen, S. A. (1996) Circulation 94, 3083–3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scriven, D. R., Dan, P. & Moore, E. D. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 2682–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou, D., Lambert, S., Malen, P. L., Carpenter, S., Boland, L. M. & Bennett, V. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143, 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins, S. M. & Bennett, V. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemaillet, G., Walker, B. & Lambert, S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27333–27339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrido, J. J., Giraud, P., Carlier, E., Fernandes, F., Moussif, A., Fache, M. P., Debanne, D. & Dargent, B. (2003) Science 300, 2091–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maier, S. K., Westenbroek, R. E., Schenkman, K. A., Feigl, E. O., Scheuer, T. & Catterall, W. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4073–4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivolta, I., Abriel, H., Tateyama, M., Liu, H., Memmi, M., Vardas, P., Napolitano, C., Priori, S. G. & Kass, R. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30623–30630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohler, P. J., Schott, J. J., Gramolini, A. O., Dilly, K. W., Guatimosim, S., duBell, W. H., Song, L. S., Haurogne, K., Kyndt, F., Ali, M. E., et al. (2003) Nature 421, 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambrano, G. R., Fraser, I., Han, H., Ni, Y., O'Connell, T., Yan, Z. & Stull, J. T. (2002) Nature 420, 712–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balser, J. R. (2001) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 599–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett, E. S. (2004) J. Membr. Biol. 197, 155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gagelin, C., Constantin, B., Deprette, C., Ludosky, M. A., Recouvreur, M., Cartaud, J., Cognard, C., Raymond, G. & Kordeli, E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12978–12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kordeli, E., Ludosky, M. A., Deprette, C., Frappier, T. & Cartaud, J. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 2197–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucera, J. P., Rohr, S. & Rudy, Y. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 1176–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baroudi, G., Acharfi, S., Larouche, C. & Chahine, M. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, E11–E16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey, S. J., Stocksley, M. A., Buckel, A., Young, C. & Slater, C. R. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 2102–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flucher, B. E. & Daniels, M. P. (1989) Neuron 3, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido, J. J., Fernandes, F., Moussif, A., Fache, M. P., Giraud, P. & Dargent, B. (2003) Biol. Cell 95, 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kizhatil, K. & Bennett, V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16706–16714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren, Q. & Bennett, V. (1998) J. Neurochem. 70, 1839–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.