Knowing the structures of transition states is crucial to the understanding of any chemical mechanism. As the transition state is an ephemeral species, its properties can be studied experimentally only indirectly from kinetics, with fine structural details inferred from the analysis of reaction kinetics of reagents whose structures have been subtly altered. A battery of protein engineering techniques has been developed to apply to study protein folding, of which the application of the latest method, ψ analysis, to ubiquitin is described by Sosnick et al. (1) in this issue of PNAS. Their results suggest that more structure is formed in the transition state than indicated by Φ-value analysis, which has been the standard method for nearly two decades, and the transition state is heterogeneous.

Transition States and Φ-Value Analysis

The key procedure in transition-state analysis is to mutate the structures of amino acids and measure the changes in kinetics and equilibria of protein folding. In Φ analysis, mutations are designed to delete or alter existing weak interactions. The parameter Φ (= ΔΔG‡/ΔΔG0, where ΔΔG‡ is the change of free energy of activation and ΔΔG0 the change in free energy of folding on mutation) is a measure of the average extent of structure formation at the mutated site on a scale of 0 to 1, relative to denatured and native states, respectively (2). Φ Analysis gives the degree of formation of elements of secondary structure and tertiary interactions (3) and even backbone-backbone hydrogen-bonding interactions (4). Formation of pairwise interactions may be identified unambiguously by the application of double-mutant cycles in which both partners are mutated. Movement of the transition state around the energy landscape also can be detected (5). Importantly, Φ values are the raw stuff of simulation: computer modeling reconstructs the 3D structure of the transition state that is consistent with the inputted Φ value (6–9). Simulation gives further information that is difficult to obtain directly from experiment, such as the presence of nonnative interactions and the heterogeneity of the transition state, as well as filling in the whole folding and unfolding pathways. Φ Analysis has been well validated by simulation (10, 11).

ψ Analysis

ψ Analysis is a proposed new procedure for measuring the extent of development of interactions in transition states and their heterogeneity caused by parallel pathways (1). It works by introducing new interactions: the substitution of two target amino acid residues by His residues that may be reversibly cross-linked in the native state, N, by adding an ion such as Co2+ (12). ψ Analysis proposes two parallel routes for folding and unfolding: one in which the His residues are in their native state proximity in the transition state (“present”), which can bind M2+; and one in which they are apart (“absent”). In the absence of M2+, the protein folds with a rate constant kf(0) = kabs + kpres. On the addition of M2+, the rate constant for the present route is enhanced, but kabs remains present and constant as M2+ increases. The kinetics and equilibria of folding and unfolding are determined as a function of M2+ concentration. The change in free energy of activation for folding in the presence of M2+, ΔΔG‡, is plotted versus the equivalent change in free energy of folding, ΔΔG0, according to the ψ equation (12):

|

[1] |

where ρ0 = kabs/kpres. The term f was inserted empirically into the equations as a Brønsted coefficient, defined as the ratio of the free energies of binding of M2+ in the transition and native states. f, the limiting slope of the plot at high [M2+], is found invariably to be close to 1 (12). The data, extrapolated to the absence of M2+, give ψ0 = kpres/(kpres + kabs), which is interpreted as the degree of heterogeneity in the transition state on a scale of 0 to 1. fψ0 is the equivalent of Φ.

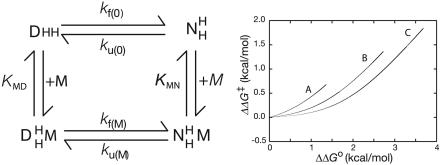

Unfortunately, the derivation (12) of Eq. 1 omitted the saturation terms that allow for the effects of [M2+] on the fractions of free and M2+-bound states of the protein. Fig. 1 Left is a mechanism-independent thermodynamic cycle that assumes rapid equilibration of M2+, with KMD its dissociation constant from the denatured state complex, KMN its constant from the native state, kf(0) the rate constant for folding of M2+-free, and kf(M) for M2+-bound protein. The observed rate constant for folding at any concentration of M2+ is given by: kf(obs) = (kf(0)KMD + kf(M)[M2+])/(KMD + [M2+]). According to the definitions in ref. 12, ΔΔG‡ = RTln(kf(obs)/kf(0)). Allowing here for the saturation terms, ΔΔG‡ = RTln((kf(M)[M2+]/kf(0) + KMD)/(KMD + [M2+])). ΔΔG0 is defined in ref. 12 by: ΔΔG0 = RTln((1 + [M2+]/KMN)/(1 + [M2+]/KMD)). The basic assumption in the derivation of Eq. 1 that ΔΔG‡ = fΔΔG0 is not obvious because of the intrusion of KMN and KMD in the formulas. I derived, therefore, the relationship between ΔΔG‡ and ΔΔG0 from just their definitions, with no other assumptions. Using the definition of ΔΔG0 to give [M2+] in terms of ΔΔG0 and substituting into the equation for ΔΔG‡ gives:

|

[2] |

This equation is fortuitously formally identical to Eq. 1 where f is always = 1 and where ρ0 = (KMD/KMN – kf(M)/kf(0])/(kf(M)/kf(0) – 1). Further, ψ = (1+[M2+]/KMN)/(1+[M2+]/KMN + ρ0(1+ [M2+]/KMD)). As [M2+] tends to 0, ψ0 = 1/(1 + ρ0), i.e.,

|

[3] |

Eq. 2 is independent of mechanism and holds for any cycle of reactions as in Fig. 1. It explains why Eq. 1 gives f ∼ 1 for all of the examples in ref. 12. ρ0 and ψ do not give measures of kabs and kpres or heterogeneity of pathways but are just combinations of the linked rate and thermodynamic constants.

Fig. 1.

The effects of metal binding on protein folding. (Left) Thermodynamic cycle for rapid distribution of M2+ ion (M) between denatured (D) and native (N) states. (Right) Simulated plots for the cycle of ΔΔG‡ (= RTln((kf(M)[M2+]/kf(0) + KMD)/(KMD + [M2+]))) vs. ΔΔG0 (= RTln((kf(M)[M2+]/kf(0) + KMD)/(KMD + [M2+])) – RTln((ku(M)[M2+]/ku(0) + KMN)/(KMN + [M2+]))). From left to right, A, KMD = 500 μM, KMN = 50 μM, kf(0) = 1,000/s, kf(M) = 3,160/s, ku(0) = 100/s, ku(M) = 31.6; B, KMD = 500 μM, KMN = 5 μM, kf(0) = 1,000/s, kf(M) = 10,000/s, ku(0) = 100/s, ku(M) = 10/s; C, KMD = 500 μM, KMN = 1 μM, kf(0) = 1,000/s, kf(M) = 22,360/s, ku(0) = 100/s, ku(M) = 4.47. These plots all are constructed to have 50% of the metal binding energy present in the transition state (f = 0.5) for two simple parallel pathways without any heterogeneity of the transition state in the absence of M2+. The three plots fit with 100% precision to the proposed ψ plot (Eq. 1) with f values of 1.0 for each and kabs/kpres(0) of 3.167, 10, and 22.36, respectively, and corresponding values of ψ0 of 0.24, 0.09, and 0.04.

To test Eqs. 1 and 2, I simulated data for folding reactions with 50% of the binding energy in the transition state, i.e., f = 0.5 (Fig. 1 Right). The data fitted Eq. 1 with f = 1.00. The values of ρ0 were in perfect agreement with those calculated from ρ0 = (KMD/KMN – kf(M)/kf(0))/(kf(M)/kf(0) – 1). The derived values of ψ0 were quite different from 0.5.

More complex equations may be formulated, such as those that include parallel pathways (1, 12). But they have to be fitted to Eq. 2 and not Eq. 1, and the derived values of ψ and ρ0 will have components from the equilibrium dissociation constants: e.g., if kf(0) = kabs + kpres, then ρ0 = (KMD/KMN – kf(M)/(kabs + kpres))/(kf(M)/(kabs + kpres) – 1).

Information Content of ρ0 and ψ

ρ0 does not, per se, give information about heterogeneity of transition states and parallel pathways as it is not possible from the canonical Eq. 2 to show that kf(0) = kabs + kpres. Indeed, in most cases examined so far by simulation (8, 9, 13) or directly by experiment (14), a partial Φ value corresponds primarily to partial content of native interactions. A high ρ0 occurs when KMD/KMN is high and Φ < 1. ψ is interpretable as a measure of structure formation at its extreme values. If kf(M)/kf(0) = 1 in Eq. 3, i.e., there is no enhancement by M2+, then ψ = 0, implying no binding of M2+ in the transition state. If kf(M)/kf(0) = KMD/KMN, i.e., when the binding site for M2+ is as well formed in the transition state as in N, ψ = 1. But, there is not a linear relationship between ψ and the extent of formation of structure. The problem is that the His-M2+-His bonds are much stronger than most noncovalent interactions in proteins, and the structural changes on protein folding affect the overall energetics of metal binding as a distortion energy term.

Flexibility in Transition-State Constraints

If the transition state is flexible in the region between the two His residues, then their linking by the M2+ ion may allow the overall topology of transition state to be retained but the region between the His-M2+-His to be distorted at some cost of energy. Further, there is some geometric freedom for the carboxyamide groups of His residues that are tethered just by their imidazole rings, which might be sufficiently large that the M2+-binding site may not sense the movement apart of the chain. Thus, the flexibility of the cross-linking constraints and the protein in the transition state could conspire to give a metal binding site in a region of low Φ, which would lead to an artefactually high value of ψ. The only unambiguous value of ψ under these circumstances is zero.

ψ Versus Φ Analysis

According to my analysis, ψ analysis does not give information per se on transition-state heterogeneity and ψ does not respond linearly with Φ or degree of formation of structure. There are differences from Φ analysis: ψ substitutions add new interactions rather than delete existing ones and are restricted to just surface-exposed regions. Accordingly, ψ analysis cannot tackle all of the aspects accessible to Φ analysis, especially interactions within the hydrophobic core. Double-mutant cycle Φ analysis also can tackle distance constraints in a more benign way. If there is any plasticity in the transition state that can accommodate partly or fully the constraints of the cross link, then the ψ value could be significantly > 0 for a region of structure that is normally disordered in the transition state. So, ψ values could overestimate the extent of formation of structure in regions of low Φ value. Φ analysis has a number of minor caveats, but it is a relatively robust technique, and values of 0 and 1 are essentially always interpretable as denatured- and native-like in the absence of simulation. A value of ψ = 0 could be a further useful strong constraint in simulation. Other values may be weaker or unrealistic constraints, although values of 1 are tempting. The real power of Φ analysis is that it probes a very large number of the noncovalent interactions in the protein in a relatively benign way. Theoreticians can just plug the Φ values into simulation in a very simple manner, using a single WT structure. It will now be interesting to see how well ψ values can be used.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Michele Vendruscolo for comments, Dr. Tobin Sosnick for comments and an open and cordial exchange of ideas, and Dr. S. Walter Englander for enthusiastic encouragement.

See companion article on page 17377.

References

- 1.Sosnick, T. R., Dothager, R. S. & Krantz, B. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17377–17382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fersht, A. R. & Sato, S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7976–7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato, S., Religa, T. L., Daggett, V. & Fersht, A. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6952–6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deechongkit, S., Nguyen, H., Powers, E. T., Dawson, P. E., Gruebele, M. & Kelly, J. W. (2004) Nature 430, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedberg, L. & Oliveberg, M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7606–7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fersht, A. R. & Daggett, V. (2002) Cell 108, 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vendruscolo, M. & Paci, E. (2003) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onuchic, J. N. & Wolynes, P. G. (2004) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 14, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daggett, V. & Fersht, A. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, L. & Shakhnovich, E. I. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13014–13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindorff-Larsen, K., Paci, E., Serrano, L., Dobson, C. M. & Vendruscolo, M. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 1207–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krantz, B. A., Dothager, R. S. & Sosnick, T. R. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paci, E., Vendruscolo, M., Dobson, C. M. & Karplus, M. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 324, 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fersht, A. R., Itzhaki, L. S., Elmasry, N., Matthews, J. M. & Otzen, D. E. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10426–10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]