Abstract

Selection is one of the most important forces in crop evolution. Common wheat is a major world food crop and a typical allopolyploid with a huge and complex genome. We applied four approaches to detect loci selected in wheat during domestication and improvement. A total of 7,984 candidate loci were detected, accounting for 23.3% of all 34,317 SNPs analysed, a much higher proportion than estimated in previous reports. We constructed a first generation wheat selection map which revealed the following new insights on genome-wide selection: (1) diversifying selection acted by increasing, decreasing or not affecting gene frequencies; (2) the number of loci under selection during domestication was much higher than that during improvement; (3) the contribution to wheat improvement by the D sub-genome was relatively small due to the bottleneck of hexaploidisation and diversity can be expanded by using synthetic wheat and introgression lines; and (4) clustered selection regions occur throughout the wheat genome, including the centromere regions. This study will not only help future wheat breeding and evolutionary studies, but will also accelerate study of other crops, especially polyploids.

Selection, one of the most important drivers of variation in crop domestication and improvement, usually leaves genomic footprints known as selection signatures1. The effort, experience, intelligence and wisdom of farmers and thousands of breeders worldwide during crop domestication and improvement are hidden in the signatures. Therefore, identification of selection signatures and construction of a genome-wide selection map will produce a “treasure map” for breeders. Detection of selection signatures is a central challenge for both evolutionary biology and crop breeding.

Domestication and improvement (post-domestication selection) are important processes of crop evolution whereby selection is the major driver of adaptation to diverse environments in the achievement of high yields. “Domestication syndrome” characters, including loss of seed dispersal mechanisms, increased grain size, loss of sensitivity to environmental cues for germination and flowering, synchronous ripening, and a compact growth habit are adaptive traits selected by mankind2. Improvement, or plant breeding, as another evolutionary force, creates superior plant genotypes that are selected by phenotype and become fixed in cultivars with improved yield, stability, nutritional qualities, and other traits of commercial value3. Selection operates at specific loci and leaves its signature in distinct chromosomal regions. By comparing genomic patterns and levels of variability across populations it is possible to identify selection signatures left by evolutionary forces4,5.

Genome-wide surveys are important means of detecting deviations from neutrality among loci. With recent rapid developments in technology many plant species have been sequenced, and even re-sequenced, and millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified. SNPs have been used to screen for selected regions across the whole genomes of rice6,7, maize8,9, soybean10,11,12, and tomato13. Most previous studies reported reduced polymorphism in relation to domestication and improvement. A well-known example is Tanksley’s funnel type selection model14. By using this approach it was estimated that selected loci accounted for 5% of the maize genome15,16 and 7% of the sunflower genome17.

In addition to diversity loss18,19, looking for extreme patterns of population differentiation (FST)20,21 and significant changes in allele frequency and phenotype22 were also employed to detect loci subjected to selection. However, all these methods were used separately, and the results were not easily compared. Importantly, few selection studies in polyploid crops have been reported although more than 70% of crops species are polyploids23. This means that the contribution and potential of sub-genomes in polyploid crops to domestication and improvement have not been revealed.

Common wheat, a typical polyploid and a major world food source for 40% of the world population, is extensively grown on 17% of the world cropping area from 67°N in Norway, Finland and Russia to 45°S in Argentina24. With the millions of SNPs now discovered by next generation sequencing technology, it is possible to screen for genomic regions in wheat that have undergone selection during evolution. Currently, several wheat SNP arrays are publically available25,26 and some selected regions, or QTLs, have been identified using these SNP chips25,27.

In the present work, genome-wide surveys for molecular signatures of selection were carried on 31,417 informative SNPs by four methods. We used three wheat populations representative of two evolutionary stages, from wild relatives to landraces through domestication and to modern varieties through post-domestication selection or breeding. Loci with decreased, increased, and even constant variation were considered. A first generation map of selection signatures of wheat was constructed. Utilization of genomic regions that had undergone selection during wheat domestication and improvement is discussed.

Results

Detection of selection candidate loci

As previously described25,28, genotyping of wheat by the 90K Infinium wheat chip is complicated by the homoeologous genomes. Of 81,587 SNPs analysed, 34,317 were classified as AA or BB alleles after removing those with greater than 20% missing data points. The numbers of polymorphic SNPs in populations of wild accessions (W), landrace accessions (L) and modern (M) varieties were 30,577, 21,831 and 24,029, respectively. A subset of 82 modern varieties was randomly taken from the 429 modern varieties and 24,588 polymorphic SNPs were observed in this subset. The result ascertained that the higher number of polymorphic SNPs in modern cultivars was not due to the difference in sample size. This tendency was also observed previously where a 9K SNP array was applied to assess the diversity of landraces and modern cultivars25. Another explanation for the higher polymorphic SNP number in modern Chinese varieties than in landraces was the contribution of introduced varieties used in wheat breeding.

The numbers of polymorphic SNPs detected in pairwise comparisons of WL and LM were 33,403 and 26,519, respectively. Genetic differentiation between groups W and L revealed by these SNPs was about two-fold higher (FST = 0.148 ± 0.006) than between groups L and M (FST = 0.076 ± 0.004). Of the 34,317 polymorphic SNPs, 22,533 had known positions on the 21 chromosomes (Table 1). The number of SNPs analysed in the D sub-genome (3,800) was about one-third of those in the A and B sub-genomes (8,308 and 10,425, respectively), presumably the result of the population bottleneck effect following hexaploidisation. All 34,317 SNPs were used for detection of selection outliers between populations by using the following four approaches: F-statistical test (FST), diversity test (lnRH), frequency-based test (Freq) and genome-wide association study (GWAS) test.

Table 1. Summary of selection candidates identified by different methods during wheat domestication and improvement.

| Domestication |

Total | Improvement |

Total1 | No. loci analyzed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FST | lnRH | Freq | FST | lnRH | Freq | GWAS | |||||

| 1A | 141 | 29 | 92 | 150 | 38 | 16 | 42 | 138 | 58 | 1293 | |

| 2A | 150 | 98 | 31 | 174 | 167 | 14 | 161 | 67 | 185 | 1197 | |

| 3A | 129 | 17 | 101 | 137 | 81 | 18 | 78 | 172 | 100 | 1036 | |

| 4A | 96 | 38 | 71 | 121 | 14 | 41 | 31 | 31 | 60 | 886 | |

| 5A | 125 | 56 | 89 | 168 | 41 | 53 | 42 | 161 | 91 | 1328 | |

| 6A | 146 | 138 | 38 | 199 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 285 | 17 | 1198 | |

| 7A | 110 | 31 | 99 | 140 | 92 | 36 | 94 | 53 | 131 | 1370 | |

| A sub-genome | 897 | 407 | 521 | 1089 | 434 | 193 | 450 | 907 | 642 | 8308 | |

| 1B | 163 | 55 | 84 | 177 | 18 | 356 | 19 | 460 | 377 | 2089 | |

| 2B | 155 | 56 | 60 | 168 | 49 | 42 | 59 | 318 | 98 | 1779 | |

| 3B | 91 | 20 | 52 | 96 | 18 | 64 | 22 | 79 | 86 | 1160 | |

| 4B | 155 | 37 | 146 | 196 | 44 | 105 | 45 | 22 | 152 | 948 | |

| 5B | 177 | 21 | 157 | 209 | 53 | 178 | 49 | 459 | 233 | 1691 | |

| 6B | 89 | 46 | 33 | 108 | 79 | 25 | 68 | 64 | 102 | 1451 | |

| 7B | 84 | 40 | 53 | 108 | 70 | 45 | 70 | 79 | 102 | 1307 | |

| B sub-genome | 914 | 275 | 585 | 1062 | 331 | 815 | 332 | 1481 | 1150 | 10425 | |

| 1D | 58 | 28 | 36 | 75 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 15 | 575 | |

| 2D | 77 | 42 | 50 | 106 | 4 | 163 | 4 | 15 | 167 | 863 | |

| 3D | 62 | 17 | 48 | 78 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 17 | 24 | 393 | |

| 4D | 13 | 14 | 21 | 35 | 1 | 21 | 1 | 5 | 22 | 173 | |

| 5D | 39 | 91 | 55 | 147 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 680 | |

| 6D | 27 | 23 | 17 | 50 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 45 | 9 | 306 | |

| 7D | 38 | 128 | 51 | 182 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 810 | |

| D sub-genome | 314 | 343 | 278 | 673 | 23 | 235 | 19 | 119 | 258 | 3800 | |

| Total | Known positions | 2125 | 1025 | 1384 | 2824 | 788 | 1243 | 801 | 2507 | 2050 | 22533 |

| Unknown positions | 663 | 655 | 355 | 1187 | 209 | 465 | 234 | 647 | 11784 | ||

| All | 2788 | 1680 | 1739 | 4011 | 997 | 1708 | 1035 | 2507 | 2697 | 34317 | |

1The number of selection candidates identified by FST, lnRH and Freq.

Selection of outlier loci by F-statistical test

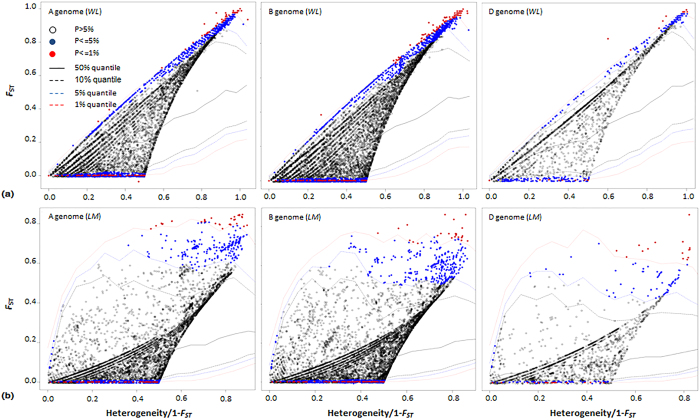

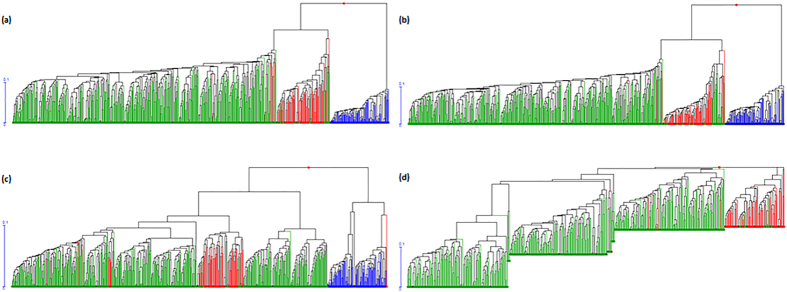

To identify loci that made significant contributions to population divergence, we used the Fdist test method available in Arlequin v3.5 to detect selection outliers. Only loci with extremely high FST and heterogeneity values were considered to be positive signals affecting population divergence. Respectively, 2,788 and 997 SNPs were identified as outliers in pairwise WL and LM comparisons at 5% quantile values (Fig. 1, Supplementary Dataset 1) accounting for about 8 and 3% of all 34,317 polymorphic SNPs.

Figure 1.

Outliers detected by the FST method in pairwise comparisons of WL (a) and LM (b). For SNP names of putative outliers potentially affected by selection, see Supporting Information (Supplementary Dataset 1). Y-axis, FSTmeasures locus-specific genetic divergence between populations; X-axis, Heterogeneity/1-FSTis a modified measure of heterogeneity per locus.

Selection of outlier loci by diversity test

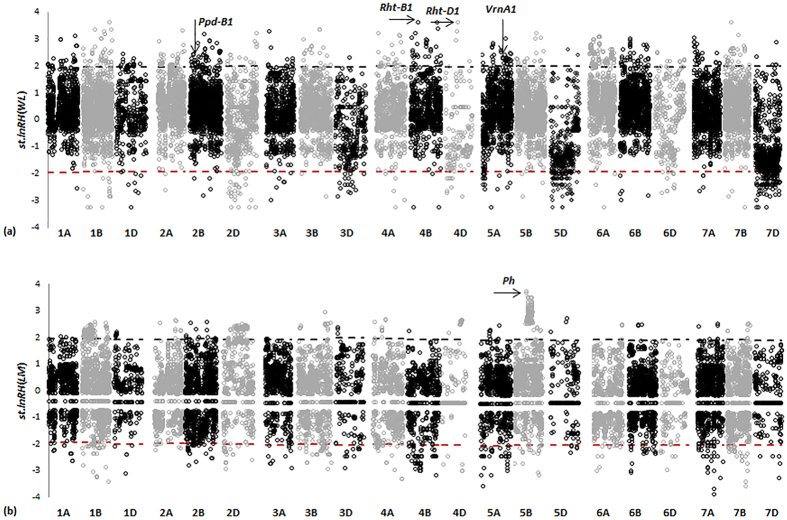

Genetic variation during evolution is an important parameter of selection signatures often employed in detection of selection loci. We calculated lnRH values in pairwise comparisons of populations and determined confidence intervals of the lnRH distribution (Table 1, Supplementary Dataset 2). This method was previously confirmed as being efficient in identifying selection signatures based on SNP markers29. Of the 34,317 SNPs, 1,680 and 1,708 loci were detected as selection signatures during domestication and improvement, respectively (Fig. 2). Genetic variation was decreased at 1,685 loci and increased at 1,703 loci during wheat evolution.

Figure 2. Selection candidates identified by the lnRH method for domestication (a) and improvement (b).

Standardized lnRH values at the level of P < 0.05 are shown as black and red dashed lines, respectively. Loci with st.lnRH values beyond the region [−1.96, +1.96] are considered as selection candidates. Genetic positions are shown for Ppd-B1, Rht-B1, Rht-D1 and Vrn-A1 where selection candidates were identified during wheat domestication. A genetic region on chromosome 5B associated with plant height (Ph) is indicated.

Selection of outliers by the frequency-based method

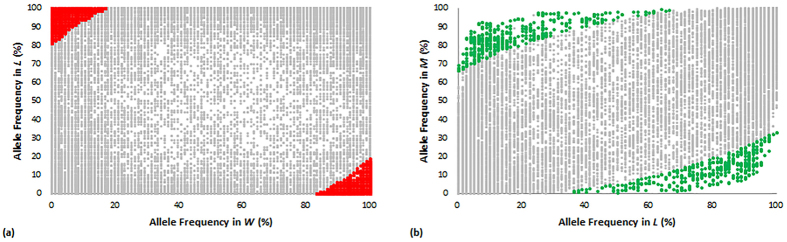

Traditional selection is mainly based on phenotypes conferred by allelic variation. Therefore, variation in allele frequency in different populations can be used to detect selected loci. In this study, the μ test was applied to compare differences in allelic frequency between populations. Strict criteria with μ values higher than 11 were used to compare different loci in order to reduce the number of false positives; 1,739 and 1,035 SNPs were identified as selection candidates during domestication and improvement, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Dataset 3). As shown in Fig. 3, the candidates identified by pairwise comparisons demonstrated extremely different allelic frequencies between groups.

Figure 3. Distribution of allelic frequencies between groups.

Comparisons between groups W and L (a) and between groups L and M (b). Selection candidates by domestication and improvement are shown in red and green, respectively.

Phenotypic variation detected by association analysis

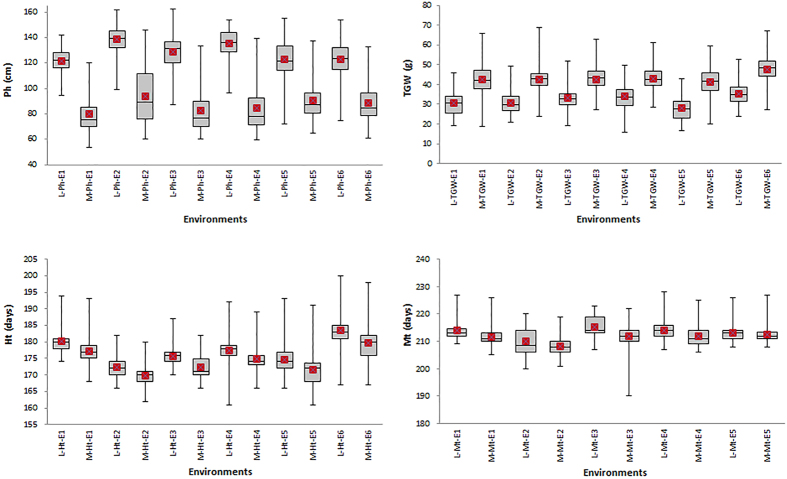

During domestication and improvement selection was based on agronomically important traits, such as seed dormancy, heading time, resistance to lodging, and yield and its components. Therefore, phenotypic differences should exist between populations. Detecting such phenotypic variation and identifying the underlying genes is a direct way of finding selection signatures. This was suggested as a bottom-up approach to identify genes under selection22. As common wheat is hexaploid and its ancestors are diploids their phenotypes are not comparable. Therefore, phenotypic variation was assessed only between the L and M groups. Ten agronomic traits were analysed and all showed significant differences in at least three of the six environments in which the materials were grown (Table 2, Fig. 4). As expected, the plant heights (Ph) of accessions in population M were less than those in L, and likewise heading and maturity times (Ht and Mt) were also different. Moreover, the mean values for thousand grain weight (TGW) and yield (Y) of population M were higher than those for L. Population M was more resistant to powdery mildew (PM) than L. These distinct differences reflected the selective pressures of modern breeding. GWAS was conducted to find loci affecting trait differences between populations. The Q-Matrix generated from STRUCTURE was used to correct GWAS (Supplementary Fig. 1). A total of 2,507 SNPs was associated with traits using A–D test at the Bonferroni-corrected threshold (−log(P-value) ≥ 5.84, α = 0.05) (Supplementary Dataset 4, Supplementary Figs 2 to 11). Of the 2,507 selection candidates identified by GWAS, 893 were also detected by one or more of the other three methods (419, 559 and 304 loci detected by the FST, lnRH and Freq method, respectively), accounting for 35.6% of the improvement loci (Table 3). Because only ten agronomic traits were analysed, more overlapping loci would be identified if more agronomic traits and the W population were assayed.

Table 2. Comparison of agronomic traits1 between groups L and M.

| Parameter2 | T | Ph | SL | SLN | GN3 | TGW | Ht | Mt | PM | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 10/8 | 128/86.7 | 9.1/8.9 | 19/18 | 47/45 | 31.9/43.4 | 191.3/187.5 | 230.3/228 | 3/2.6 | 1.9/2.9 |

| Vc (%) | 34/33 | 10.5/18.8 | 24.1/18.6 | 10.7/10.3 | 20/19.1 | 20.4/15.9 | 3.2/3.4 | 0/1.9 | 36.2/46.1 | 25.8/19.3 |

| Min | 3.7/3 | 72.4/53.8 | 4.8/4.3 | 12/13 | 22/21 | 15.7/18.8 | 167/167 | 217/197 | 0/0 | 0/0.4 |

| Max | 20/19 | 162.7/145.8 | 18.3/25.5 | 29/29 | 75.2/89.3 | 52.5/68.9 | 211/210 | 245/244 | 4/4 | 3/4 |

| VM/L(%) | −20 | −32 | −2 | −5 | −2 | 36 | −2 | −1 | 13 | 53 |

| T-test(p value) | 0 | 0 | 0.012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

1T, tiller number; Ph, plant height; SL, spike length; SLN, spikelet number; GN, grain number; TGW, thousand grain weight; Ht, heading time; Mt, mature time; PM, powdery mildew resistance; Y, yield.

2Numbers left and right of “/” were the traits of landraces and of modern varieties, respectively.

3Trait GN was significantly different between L and M in three environments. VM/L (%) is the trait variations of population M compared with that of L.

Figure 4. Boxplots for agronomic traits measured in different environments.

Environments E1 to E4, Beijing, Jiaozuo, Luoyang and Xinxiang in crop season 2011–2012; E5 and E6, Xinxiang in 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, respectively.

Table 3. Summary of selection loci identified by different methods.

| Total | Common | Unique | lnRH | Freq | GWAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FST | 3568 | 3049 | 519 | 801 | 2361 | 419 |

| lnRH | 3344 | 1306 | 2038 | — | 229 | 559 |

| Freq | 2674 | 2435 | 239 | — | — | 304 |

| GWAS | 2507 | 893 | 1614 | — | — | — |

Since the germplasm was divided into W, L and M groups the results should reflect the effects of artificial selection and recent breeding. To test if the loci detected by the four approaches were selected loci, we made UPGMA trees of 96 wild accessions (W), 84 landraces (L) and 429 modern cultivars (M) using the above candidate SNP markers. The UPGMA trees were consistent with expectation; screening by the four methods clearly separated the populations (Fig. 5), indicating the respective roles of selection in population differentiation. The distance between W and L was much larger than that between L and M because the evaluation time between W and L was much longer (8000 vs. 100 years30). Higher genetic differentiation was confirmed in the transition from wild species to landraces than that from landraces to modern cultivars (FST, 0.15 vs. 0.08). These results proved that all of the four methods were effective in detecting selection loci.

Figure 5. UPGMA trees of 96 wild accession combinations (W), 84 landraces (L) and 429 modern cultivars (M).

Trees were constructed based on selection loci detected by FST (a), Freq (b), lnRH (c) and GWAS (d). Blue, red and green dots represent wild relatives (W), landraces (L) and modern cultivars (M), respectively.

In summary, four approaches to estimate changes in diversity, allele frequency, population divergence and GWAS, were employed to detect selection loci. In total, 7,984 candidate selection loci were detected by the four approaches, accounting for 23.3% of all 34,317 SNPs analysed, much higher than estimates in previous reports. Table 3 summarizes the number of selection candidates detected by different methods. Except for FST and Freq, common loci detected by any two approaches were less than 50%, indicating relative independence of the different methods (Table 3). This suggests that the number of selection loci detected by any individual method is incomplete. Tajima’s D tests confirmed these results. Tajima’s D is 0 for neutral variation, positive for balancing selection, and negative for selective sweep31. Of the 6,224 selection candidates, Tajima’s D was positive and negative for 5,817 and 407 SNPs, respectively (Supplementary Dataset 5). Of the 5,817 candidates with positive Tajima’s D, 4,125 SNPs showed significant deviations from neutrality (Tajima’s D > 1.7, p < 0.1). These 4,125 candidates were identified either by the diversity-based or frequency-based methods, or both.

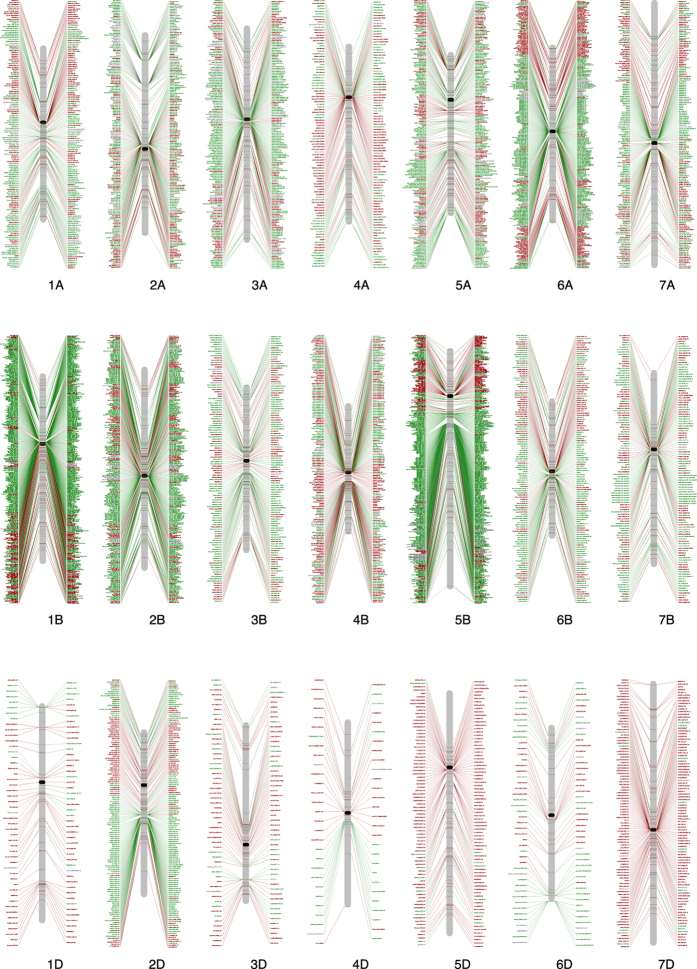

Construction of a selection map and analysis of selection candidates

Construction of a selection map is of significance for both evolutionary studies and breeding. Detection of selection loci genome-wide provides an opportunity to construct a map of selection loci. Of the 7,984 candidates, 6,224 SNPs had known chromosome positions (Supplementary Datasets 1, 2, 3, 4), based on which a wheat primary selection map was constructed (Fig. 6). It is a first selection map in a crop species. This map revealed new insights into the genome-wide selection loci during wheat domestication and improvement.

Figure 6. Selection map of wheat during domestication and improvement.

Red, green and purple lines denote candidates subjected to selection during domestication, improvement and both processes, respectively. Centromeric regions are indicated by black dots in accordance with Cavanagh et al.25. Detailed information on the mapped loci is provided in Supplementary Datasets 1 to 4.

Genetic variation among selection candidates

Of the 7,984 selection locus outliers, 3,344 (42.8%) were identified by comparing diversity changes between populations with 1,659 increased and 1,641 decreased, respectively. A further 4,640 loci were identified by at least one of the other three methods. Nearly 60% of these candidates showed no statistical difference in diversity in pairwise comparisons. Results based on diversity changes suggest that selection could increase diversity and that loci with reduced variation represented only a part of the selection outliers.

The results clearly indicated that selection resulted in reduced diversity because of population bottlenecks, or hitchhiking effects (linkage drag), or the commonly known directional selection. In addition, adaptive selection also enables plants to adapt to new habitats. For example, SNP wsnp_Ex_rep_C66689_65011117 positioned in the Vrn-A1 region on chromosome 5A was identified as a domestication candidate. This locus was monomorphic in wild relatives but showed increased diversity in modern cultivars (He, 0.4). More often, the diversity index did not change significantly, although allele frequencies underwent large changes.

To trace the variation in diversity among selection candidates during evolution, we found that 752 loci selected by domestication were fixed during wheat improvement. On the other hand 304 loci detected as selection targets by improvement were monomorphic during domestication, suggesting that diversity increases occurred during wheat improvement (Supplementary Dataset 2). This implied that modern breeding was a process of fixing and mining key genomic selection regions.

The number of domestication loci is greater than the number of improvement loci

In total, 4,011 domestication loci and 2,697 improvement loci were identified at P < 0.05 by all methods except GWAS, which was used for detecting differences in the L and M populations. The total number of selected domestication loci was about 1.5-fold that of improvement loci. The numbers of loci selected during domestication and detected by FST and Freq tests was about 2.8- and 1.7-fold of that during improvement (Table 1). This was consistent with wheat evolutionary history whereby domestication lasted for more than 8,000 years whereas improvement has been for only about 100 years30. This explains why the distance between W and L is much larger than that between L and M in the phylogeny tree (Fig. 5). We identified 566 SNPs responsible for the separation of all three populations (Supplementary Dataset 6), suggesting continuous selection on these loci during the two periods. Clearly, selection in both processes focused on yield, adaptation and other agronomic traits. For example, we found 33 loci significantly associated with plant height (Ph), TGW, yield (Y) and heading time (Ht) in the following analyses.

Fewer loci selected by improvement were discovered in the D sub-genome

Comparing the distribution of selection candidates among sub-genomes, 13.1, 10.2, and 17.7% of loci in the A, B, and D sub-genomes, respectively, were detected as candidates selected by domestication. In relative terms the B sub-genome contributed only in a small way compared to the D sub-genome during domestication. However, only 6.8% of loci in the D sub-genome were detected to be selection candidates during improvement compared to 7.7 and 11.0% of loci in the A and B sub-genomes, respectively (Table 1). Of the total 2,050 improvement loci, candidate loci contributed by the D sub-genome accounted for 12.5%, much fewer than that by the A (31.3%) and B (56.1%) sub-genomes, indicating a comparatively low contribution of the D sub-genome to wheat improvement. The major reason was lower polymorphism (60%) between the L and M populations in the D sub-genome than in the A (96%) and B (97%) sub-genomes, respectively, hence confirming the D sub-genome bottleneck effect in wheat improvement.

Since genetic diversity is very rich in Aegiolops tauschii, the donor of the D sub-genome to hexaploid wheat, there should have favorable, but unexploited, agronomically important alleles. To confirm that speculation we analysed the QTLs in introgression line derivatives of synthetic line Am3, a synthetic wheat, backcrossed to Laizhou 953, a Chinese commercial variety. Forty-eight QTL conferring nine agronomic traits were detected in three environments. Seventeen, 17 and 14 were mapped to the A, B, and D sub-genomes, respectively. The number of QTL mapped to the D sub-genome was similar to those for the A and B sub-genomes, suggesting that the D sub-genome could make a similar contribution to wheat improvement, and that fewer agronomic trait loci detected in the D sub-genome in GWAS analysis was due to the bottleneck effect of the D sub-genome during wheat domestication. Among the QTLs mapped on the D sub-genome there were favorable alleles for agronomic traits, including increased yield and TGW, reduced plant height, and resistance to powdery mildew. For example, a QTL from Am3 on chromosome 6D increased yield by 16% in three environments. This allele was not detected in the GWAS analysis of the L and M populations, suggesting that it is novel and therefore potentially valuable for future wheat improvement.

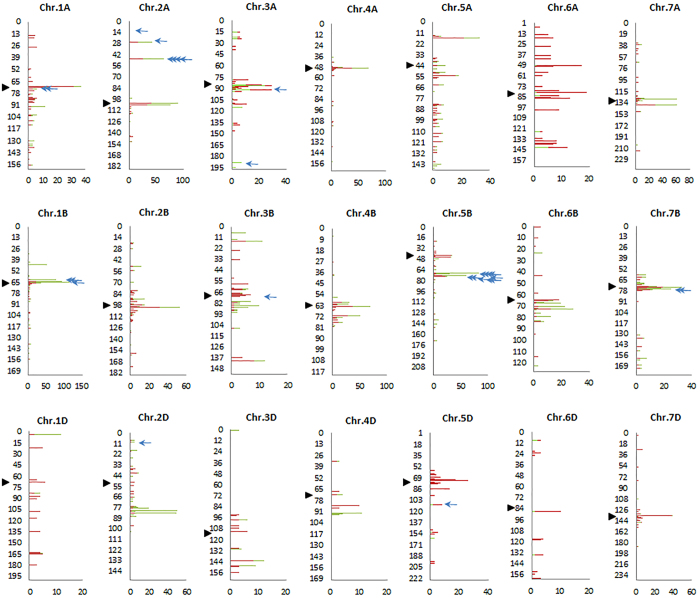

Selection loci are distributed in clusters across the wheat genome

The selection map revealed that selection candidates were clustered (less than 1 cM) in the wheat genome (Fig. 7). Of the 7,984 selection candidate loci, 5,317 (66.6%) were distributed in 515 clusters, 10.3 loci per cluster on average, suggesting that these clusters were active or ‘hot’ selection regions. These regions have made significant contributions to wheat domestication and improvement. Therefore, they will continue to be important regions for wheat evolutionary studies and breeding. For example, 109 SNPs were identified as selection candidates at position 61 on chromosome 1B with which the traits Ph, TGW and Y were significantly associated (Figs 6 and 7). The clusters were widely distributed in the wheat genome, but not evenly. More clusters (211) were present in the B sub-genome with less (115) in the D sub-genome. The largest number (43) of clusters was in chromosome 5A and least (8) in chromosome 4D (Table 4); the numbers of loci per cluster was highest for chromosomes 1B (635) and 5B (623) and least for 4D (41). There were six clusters, including three in 1B, and one each in 2B, 5B and 6A where more than one hundred selection loci were included in each cluster. More clusters were located around the centromeric regions, suggesting that these regions were also significant targets of selection although gene densities are much lower in those regions32.

Figure 7. Selection candidates clustered along chromosomes.

Only chromosome positions where at least three selection loci were identified are shown. Red and green bars are domestication and improvement loci, respectively. Blue arrows indicate chromosome positions where selection candidates are identified by four methods. Black triangles show the approximate locations of centromeres. The Y-axis is the chromosome position (cM); the X-axis is the number of selection loci identified.

Table 4. Numbers of selection clusters and their distribution in the wheat genome.

| Homoelogeous group | A |

B |

D |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loci | Clusters | Average | Loci | Clusters | Average | Loci | Clusters | Average | |

| 1 | 249 | 36 | 6.9 | 635 | 37 | 17.2 | 73 | 15 | 4.9 |

| 2 | 308 | 19 | 16.2 | 465 | 39 | 11.9 | 236 | 28 | 8.4 |

| 3 | 296 | 28 | 10.6 | 186 | 29 | 6.4 | 63 | 13 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 156 | 18 | 8.7 | 289 | 22 | 13.1 | 41 | 8 | 5.1 |

| 5 | 314 | 43 | 7.3 | 623 | 39 | 16.0 | 124 | 19 | 6.5 |

| 6 | 411 | 24 | 17.1 | 207 | 21 | 9.9 | 67 | 11 | 6.1 |

| 7 | 239 | 21 | 11.4 | 199 | 24 | 8.3 | 136 | 21 | 6.5 |

| 1973 | 189 | 10.4 | 2604 | 211 | 12.3 | 740 | 115 | 6.4 | |

Discussion

In this study 34,317 SNP loci were screened by four methods for evidence of selection during evolution; 7,984 non-redundant loci were detected as selection candidates, accounting for 23.3% of all tested loci. Across different statistical analyses the selected loci showed differences in patterns of genetic differentiation or diversity variation among the three populations.

More loci were selected in crop evolution

The proportions and identities of selected loci in crop evolution are very important issues. In previous studies, the percentages of genome-wide selection signatures ranged from 5% in maize16 to 7% in sunflower17. Moreover, only loci with reduced diversity were considered in those reports resulting in lower ratios of selection outliers. Whole-genome analysis in rice revealed that more than 10% genes were positively selected during differentiation of cultivars 93-11 and Nipponbare33. This indicated that loci with reduced diversity or those identified by only one method might be insufficiently representative of the total numbers of selection candidates.

Obviously, selection caused losses in diversity as reflected by reduced allele numbers through elimination of unfavorable alleles. Well-known selected genes, for example Q in wheat34, tb135 and tga136 in maize, and sh4 in rice37, have reduced diversity in derived populations. In the present study, loss of genetic diversity was observed for 1,641 loci (Supplementary Dataset 2), or 20.6% of all identified selection candidates. The diversity changes at these loci were consistent with models presented previously4,14.

Selection can also increase diversity in derived populations due to increased allele numbers and/or balanced allelic frequencies. Increasing allele numbers in crop plants might be required for adaptation to new environments. All crops originate from localised areas4, and to adapt to a wider range of environments additional alleles related to environmental adaptation must be generated. The wild diploid ancestors of wheat occur in parts of the Fertile Crescent; for T. urartu the current location is the Karacadağ mountain region of southeastern Turkey; for Ae. tauschii it is to the south and west of the Caspian Sea; wild emmer (T. dicoccoides) currently occurs in the Jordan Valley in Israel and neighbouring regions4,38. Modern wheat varieties are now planted worldwide, thus the range in diversity of adaptation-related or ecotype-related genes in wild populations is likely to be comparatively small. When wheat spread throughout the world, novel adaptation-related alleles at loci such as those for photoperiod, vernalization and stress tolerance were selected in the adaptation process, resulting in previously rare alleles becoming frequent in modern varieties. Our data support this speculation and show 1,659 loci with increased diversity at candidate loci, such as domestication loci in the Vrn-1 and Ppd-B1 regions (Fig. 2).

Genetic diversity of some selected loci could remain statistically non-variable in derived populations compared with ancestral populations. However, the frequencies of certain alleles were quite different between populations, presumably resulting from balanced allele distributions. In this study, 4,640 selection loci did not show significant differences in diversity between populations, but the predominating alleles and corresponding frequencies in different populations were quite different (Supplementary Dataset 1). This was characterized by some improvement loci. In this study, locus wsnp_Ex_c55777_58153636 also in the Vrn-A1 region was identified as an improvement signature by the FST and Freq methods. The frequency of allele A at this locus increased from 1.0% in population W to 22.5% in L and to 84.5% in M, indicating high selection pressure on allele A during evolution. However, the diversity at this locus between groups did not differ significantly. The same result was obtained for Vrn-B1 (wsnp_Ex_c29304_38355434 ~ wsnp_Ku_c21770_31551190).

Out results were consistent with that reported in maize8 where divergent regions with statistically significant reductions and increases in expected heterogeneity were about 7 and 35.7%, respectively, and the remaining 57.1% of regions did not show significant changes in levels of expected heterogeneity. These results indicated that diversity at loci under selection was not only lost but also increased or remained constant.

We also recognize that there are false positive selection loci detected by any approach, increasing the proportion of selection loci. Generally, the more methods used to detect selection loci, the more reliable the candidates will be. Therefore, more efficient approaches are needed. In fact, the loci detected by any approach are only candidates and further analysis is needed to prove their function.

Importance of a selection map of wheat domestication and improvement

The selection map clearly demonstrated the distribution of selection candidates during wheat evolution, including selection hotspots and cold spots (Figs 6 and 7). Such maps show genetic regions under selection pressure during wheat domestication and improvement and selection that occurred during both or in the separate phases. Domestication and improvement candidates tended to occur in clusters and were independent from each other across the genome, implying that the selection targets of the two processes were different. Domestication put more selection pressure than improvement on the D sub-genome, presumably due to the population bottleneck following polyploidization. In addition, the map clearly shows that centromeric regions were also selection targets, and that some chromosome regions were untouched by selection. Because only landraces and modern varieties were analysed by GWAS, much attention should be given to regions under selection only during domestication. These regions should be potentially important in traits for adaptation to new environments or for agronomic traits. The selection map was not only valuable for reviewing selection history, but more importantly, it suggests targets for future novel gene selection or allele discovery, genomic selection and wheat design.

Improving D sub-genome diversity by using synthetic wheat in wheat improvement

Progress in yield improvement by wheat breeding following the Green Revolution has been slow, and fails to meet projected needs for a growing world population and environmental changes. Increased yields are a first priority for wheat breeders. Common wheat is hexaploid and is comprised of the homoeologous A, B and D sub-genomes with similar gene numbers, or possibly even more genes, in the D sub-genome than in the A sub-genome39,40. However, less selection loci were detected in the D sub-genome in the present study. Results from this study and previous reports41,42 indicated that the D sub-genome made less contributions in modern breeding, implying that the D sub-genome has a high potential for future wheat improvement. This lower contribution is caused by low diversity in the D sub-genome in common wheat resulting from the bottleneck caused when hexaploid wheat arose from a single (or extremely few) spontaneous hybridizations of tetraploid wheat with Ae. tauschii 8,000–10,000 years ago43,44. However, Ae. tauschii is rich in genetic diversity38,45. Therefore, mining agronomically important genes from the D sub-genome will be important in future wheat improvement46. The use of synthetic wheat and synthetic wheat introgression lines (IL) should be an efficient approach to expand the diversity of the D sub-genome in hexaploid wheat. In the present study, we detected 17 loci affecting yield in the A and B sub-genomes, and 14 loci in a D sub-genome derived IL population, although the number of original SNP markers in the D sub-genome was much less than those from the A and B sub-genomes. Among the 14 D sub-genome loci 3 alleles originating from Ae. tauschii increased yield in a commercial wheat variety background by more than 10%. Chinese wheat variety Chuanmai 42 was bred by using a synthetic wheat as one parent, and its yield was 22.7% higher than the check cultivar Chuanmai 10747. UK scientists also reported a ‘super’ wheat line with 30% higher yield potential than the check (http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-22498274). These encouraging reports suggest that Ae. tauschii should be more widely exploited in future wheat improvement. As suggested recently48, further development of synthetic wheats and use of ILs may provide the needed breakthroughs in wheat breeding.

Methods

Plant materials, DNA extraction and genotyping

The wheat samples used for genome-wide scanning for selection signatures comprised three groups, viz. 188 wild relatives (W), 84 landrace cultivars (L) and 429 modern cultivars (M) (Supplementary Dataset 7). The wild lines included 96 wild emmer (Triticum dicoccoides) and 92 goatgrass (Aegilops tauschii) accessions. But when we do experiment, we combined DNA of one wild emmer wheat line with one goat grass line into one well, which made 96 combinations with four goatgrass repeated. Therefore, we described 96 wild relative combinations as wild group. Landraces and modern varieties used here are or were major cultivars in China, and were grown in crop season 2011–2012 at four locations, viz., Beijing (E1, 40°N, 116°E), and Jiaozuo (E2, 35°N, 113°E), Luoyang (E3, 33°N, 111°E) and Xinxiang (E4, 35°N, 113°E) in Henan province as single 0.5 × 2 m plots. These cultivars were also grown in crop seasons 2012–2013 (E5) and 2013–2014 (E6) in Xinxiang as single 1.5 × 3 m plots. The phenotypic traits investigated included plant height (Ph), spike length (SL), spikelet number per plant (SLN), grain number per spike (GN), thousand-grain weight (TGW) and tiller number per plant (T), heading time (Ht), maturity time (Mt) and powdery mildew (PM) response. Each phenotypic trait value represented the mean of at least six plants per line. In addition the yield per hectare (Y) was measured for each wheat cultivar during the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons.

DNA was isolated from the leaves of two-week-old seedlings using a DNA extraction kit (CN. DP321, Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). These DNA samples were genotyped by the Illumina wheat 90K iSelect Assay26. SNP clustering and genotype calling were performed using GenomeStudio v2011.1 software (Illumina). As previously described25,28 genotyping of polyploid wheat using the 90K SNP chip was complicated by the presence of homoeologous and paralogous gene copies among assays. Therefore, one SNP in the 90K chip might not be typically bi-allelic, and manual adjustments of the clustering patterns were necessary to ensure accurate genotyping.

Genetic diversity and measures of differentiation

SNP allele frequency and unbiased genetic diversity (He) were estimated for each locus using Powermarker v3.2549. Pairwise population FST-values were calculated in Arlequin 3.521 and tested against a null distribution obtained by 100,000 permutations of genotypes between wild and landrace (WL) and between landrace and modern (LM) cultivar accessions. Tajima’s D was estimated by using TASSEL v5.050 with a sliding window size of five SNPs and step size of one SNP along all 21 chromosomes.

Population structure

To illustrate the relationships between wild, landrace and modern variety accessions, a UPGMA tree was constructed based on a Sokal-Michener matching dissimilarity matrix using the program DARwin v5.0.15551. Branch support was determined by bootstrapping (1,000 replicates). In addition, possible population structure between landrace and modern varieties was also determined using the program STRUCTURE ver2.252 with the admixture and correlated allele frequencies model. Program run length was 10,000 with ten iterations to test for K values in the range of 1–3. The likely number of subpopulations present was estimated following Evanno et al.53.

Pairwise population tests to detect loci under selection

To identify linked candidate loci in genomic regions that had undergone selection during wheat domestication (WL) and improvement (LM), four methods were applied to identify outliers.

The first method detected outliers under selection from genetic structure analysis as described in Arlequin 3.521 where a hierarchical island model is used to perform coalescent simulations leading to the joint null distribution of hierarchical F-statistics and heterogeneities, from which locus-specific p-values are estimated. The hierarchical population structure is defined in the structure section. For detection of outliers under selection during wheat domestication and improvement WL and LM pairs were set and 20,000 coalescent simulations were performed to obtain null distributions of F-statistics. One hundred groups and 10 demes per group were simulated and a 5% quantile criterion was used. Loci with unusual FST values conditional on heterozygosity/heterogeneity were regarded as potentially under selection.

The second approach, called the lnRH-test, was based on genetic variation calculated by the ratio of genetic diversity in two populations under comparison19. lnRH was calculated as suggested by Schlotterer and Dieringer54:

, where He_der and He_anc correspond to variances in genetic diversity of the derived and ancestral populations being compared, as described by Chapman et al.17. In cases where monomorphism occurred in the ancestral population, one allele in the monomorphic ancestral population was changed to a different allele as suggested54. The lnRH values were normalized and standardized and differences between the expected distribution and empirical confidence intervals at p = 0.05 were determined. The lnRH method has been used in identifying selection signatures based on SNP markers29.

, where He_der and He_anc correspond to variances in genetic diversity of the derived and ancestral populations being compared, as described by Chapman et al.17. In cases where monomorphism occurred in the ancestral population, one allele in the monomorphic ancestral population was changed to a different allele as suggested54. The lnRH values were normalized and standardized and differences between the expected distribution and empirical confidence intervals at p = 0.05 were determined. The lnRH method has been used in identifying selection signatures based on SNP markers29.

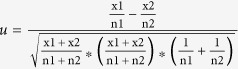

The third method was based on frequency comparisons between groups. It was assumed that selection acts on alleles of each locus and changes allele frequency. In this study, we applied a simple statistical method to test the significance of differences in variances between populations. The null hypothesis was no difference in frequency distribution between two populations. The μ value was calculated according to Gai55:

, where x1 and x2 were numbers of alleles for each locus, and n1 and n2 were the numbers of loci compared between populations. SNPs with absolute μ values larger than 11 between populations were considered to be selection outliers. Extremely higher μ values were used here to eliminate the number of false positives as much as possible.

, where x1 and x2 were numbers of alleles for each locus, and n1 and n2 were the numbers of loci compared between populations. SNPs with absolute μ values larger than 11 between populations were considered to be selection outliers. Extremely higher μ values were used here to eliminate the number of false positives as much as possible.

The fourth method was based on genome-wide association analysis (GWAS). This method was suggested as a bottom-up approached to identify selection signatures22. In this study trait data were collected for cultivars, and only landrace and modern varieties were analyzed. A total of 22,533 SNPs with known chromosome positions were used. We expected to find loci that significantly affected phenotypic differences between populations L and M. GWAS was calculated by the Anderson-Darling test56. A Q-Matrix was generated from STRUCTURE using 3,943 SNPs uniquely distributed on all 21 chromosomes. Bonferroni-corrected thresholds of α = 0.05 as cut-off values were used; at α = 0.05, the Bofferoni-corrected threshold for the p values were 2E-06 with a corresponding −logp value of 5.654. An additional GWAS sample set that included 115 introgression lines was also used to identify trait-marker associations. Synthetic wheat accession Am3 as donor and Chinese cultivar Laizhou 953 as recipient were crossed and backcrossed to build the introgression lines57. Because Am3 was synthesized by crossing T. carthlicum with Ae. tauschii, association results based on introgression lines were complementary to the natural population composed of landraces and modern varieties.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gao, L. et al. Candidate loci involved in domestication and improvement detected by a published 90K wheat SNP array. Sci. Rep. 7, 44530; doi: 10.1038/srep44530 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31271292 and No. 31261140368), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100102, 2016YFD0100302), the National 948 Project (2011-G9).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions L.G. and J.J. designed the experiments, performed all field collections and wrote the paper; L.G., G.Z. performed the analysis, and D.H. prepared Figure 6. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Kreitman M. Methods to detect selection in populations with applications to the human. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 1, 539–559 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. A., Jones M. K., Powell W. & Allaby R. G. The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 103–109 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moose S. P. & Mumm R. H. Molecular plant breeding as the foundation for 21st century crop improvement. Plant Physiol. 147, 969–977 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J. F., Gaut B. S. & Smith B. D. The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127, 1300–1321 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool J. E., DuMont V. B., Mueller J. L. & Aquadro C. F. A Scan of molecular variation leads to the narrow localization of a selective sweep affecting both Afrotropical and cosmopolitan populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 172, 1093–1105 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. et al. Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 105–111 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. et al. A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature 490, 497–501 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissinger T. M. et al. A genome-wide scan for evidence of selection in a maize population under long-term artificial selection for ear number. Genetics 196, 829–840 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford M. B. et al. Comparative population genomics of maize domestication and improvement. Nat. Genet. 44, 808–811 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J. et al. A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Nat. Genet. 46, 707–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. et al. Impacts of nucleotide fixation during soybean domestication and improvement. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 81 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. et al. Resequencing 302 wild and cultivated accessions identifies genes related to domestication and improvement in soybean. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 408–414 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. et al. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat. Genet. 46, 1220–1226 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley S. D. & McCouch S. R. Seed banks and molecular maps: unlocking genetic potential from the wild. Science 277, 1063–1066 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigouroux Y. et al. Identifying genes of agronomic importance in maize by screening microsatellites for evidence of selection during domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9650–9655 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigouroux Y. et al. An analysis of genetic diversity across the maize genome using microsatellites. Genetics 169, 1617–1630 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman M. A. et al. A genomic scan for selection reveals candidates for genes involved in the evolution of cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plant Cell 20, 2931–2945 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer C. Towards a molecular characterization of adaptation in local populations. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 683–687 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer M. O., Dieringer D. & Schlötterer C. A microsatellite variability screen for positive selection associated with the “Out of Africa” habitat expansion of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 165, 1137–1148 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont M. A. & Nichols R. A. Evaluating loci for use in the genetic analysis of population structure. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 263, 1619–1626 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L. & Lischer H. L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Ibarra J., Morrell P. L. & Gaut B. S. Plant domestication, a unique opportunity to identify the genetic basis of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, Suppl 1, 8641–8648 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis D. E., Soltis P. S. & Tate J. A. Advances in the study of polyploidy since plant speciation. New Phytol. 161, 173–191 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. H., Sun D. & Nevo E. Domestication, evolution, genetics and genomics in wheat. Mol. Breed. 28, 281–301 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh C. R. et al. Genome-wide comparative diversity uncovers multiple targets of selection for improvement in hexaploid wheat landraces and cultivars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8057–8062 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 787–796 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris J. D., Zhang Q., Chao S., Zhang Z. & Xu S. S. Analysis of agronomic and domestication traits in a durum × cultivated emmer wheat population using a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism-based linkage map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 2333–2348 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhunov E., Nicolet C. & Dvorak J. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping in polyploid wheat with the Illumina GoldenGate assay. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 507–517 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigham A. et al. Identifying signatures of natural selection in Tibetan and Andean populations using dense genome scan data. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001116 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton F. G. H. (ed.) Wheat breeding: Its scientific basis. (Chapman and Hall Ltd, London 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical methods to test for nucleotide mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H. et al. Asymmetric distribution of gene expression in the centromeric region of rice chromosome 5. Front Plant Sci. 2, 16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Jia Q., Guo Y., Zheng X. & Liang K. Whole-genome analysis revealed the positively selected genes during the differentiation of indica and temperate japonica rice. PLoS One 10, e0119239 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K. J. et al. Molecular characterization of the major wheat domestication gene Q. Genetics 172, 547–555 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J., Stec A. & Hubbard L. The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature 386, 485–488 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Studer A. J., Zhao Q., Meeley R. & Doebley J. F. Evidence that the origin of naked kernels during maize domestication was caused by a single amino acid substitution in tga1. Genetics 200, 965–974 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Zhou A. & Sang T. Rice domestication by reducing shattering. Science 311, 1936–1939 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo E. & Beiles A. Genetic diversity of wild emmer wheat in Israel and Turkey. Theor. Appl. Genet. 77, 421–455 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J. et al. Aegilops tauschii draft genome sequence reveals a gene repertoire for wheat adaptation. Nature 496, 91–95 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H. Q. et al. Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature 496, 87–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao S. et al. Analysis of gene-derived SNP marker polymorphism in US wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Mol. Breeding 23, 23–33 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. H. et al. High-density genetic linkage map construction and QTL mapping of grain shape and size in the wheat population Yanda1817 × Beinong6. PLoS One 10, e0118144 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak J., Luo M. C. & Yang Z. L. Genetic evidence on the origin of Triticum aestivum L. In: Damania A. B., Valkoun J., Willcox G. & Qualset C. O. (eds) The origins of agriculture and crop domestication. Proceedings of the Harlan Symposium, ICARDA, Aleppo, pp. 235–251 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y. & Nasuda S. Durum wheat as a candidate for the unknown female progenitor of bread wheat: an empirical study with a highly fertile F1 hybrid with Aegilops tauschii Coss. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 1710–1717 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iehisa J. C. et al. Genome-wide marker development for the wheat D genome based on single nucleotide polymorphisms identified from transcripts in the wild wheat progenitor Aegilops tauschii. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 261–271 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y., Nguyen A. T., Yoshioka M., Iehisa J. C. & Takumi S. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling grain size and shape in the D genome of synthetic hexaploid wheat lines. Breed. Sci. 63, 423–429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. et al. Synthetic hexaploid wheat and its utilization for wheat genetic improvement in China. J. Genet. Genomics 36, 539–546 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal D. et al. Exploring and mobilizing the gene bank biodiversity for wheat improvement. PLoS One. 10, e0132112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. & Muse S. PowerMarker: An integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 2128–2129 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury P. J. et al. TASSEL: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23, 2633–2635 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X. & Jacquemoud-Collet J. P. DARwin software http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin (2006).

- Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 574–578 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G., Regnaut S. & Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer C. & Dieringer D. A novel test statistic for the identification of local selective sweeps based on microsatellite gene diversity. In Selective Sweep. Nurminsky D., ed. (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers) pp. 55–64 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gai J. Y. (ed.) Experimental statistics method. (China Agriculture Press, Beijing 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Yang N. et al. Genome wide association studies using a new nonparametric model reveal the genetic architecture of 17 agronomic traits in an enlarged maize association panel. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004573 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Zhou R., Dong Y., Li P. & Jia J. Development, utilization of introgression lines using a synthetic wheat as donor. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 1360–1373 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.