Abstract

Fanconi Anemia (FA), results from mutations in genes necessary for DNA damage repair and often leads to progressive bone marrow failure. Although the exhaustion of the bone marrow leads to cytopenias in FA patients as they age, evidence from human FA and mouse model fetal livers suggests hematopoietic defects originate in utero which may lead to deficient seeding of the bone marrow. To address this possibility, we examined the consequences of loss of Fancd2, a central component of the FA pathway. Examination of E14.5 Fancd2 knockout (KO) fetal livers showed a decrease in total cellularity and specific declines in long-term and short-term hematopoietic stem cell (LT- and ST-HSC) numbers. Fancd2 KO fetal liver cells display similar functional defects to Fancd2 adult bone marrow cells including reduced colony forming units, increased mitomycin C sensitivity, increased LT-HSC apoptosis and heavily impaired competitive repopulation, implying these defects are intrinsic to the fetal liver and not dependent on the accumulation of DNA damage during aging. Telomere shortening, an aging-related mechanism proposed to contribute to HSC apoptosis and bone marrow failure in FA, was not observed in Fancd2 KO fetal livers. In summary, loss of Fancd2 yields significant defects to fetal liver hematopoiesis, particularly the HSC population, which mimic key phenotypes from adult Fancd2 KO bone marrow independent of aging-accrued DNA damage.

Keywords: Fanconi Anemia, bone marrow failure, hematopoietic stem cell, telomere dysfunction, DNA repair, fetal hematopoiesis

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Hematopoietic manifestations from Fanconi Anemia (FA) can begin in early childhood, but often increase in prevalence and severity with age(1–3). The progression of disease is thought to reflect underlying defects in DNA repair. The molecular defects in FA patients have been identified at least 20 individual genes all with hypersensitivity to DNA interstrand crosslinking (ISL) agents (2,4,5). Supporting that FA genes function in a common pathway, mutations occurring in members of the FA core complex, such as Fancc, interfere with monoubiquitylation of Fancd2 in response to DNA damage, leading to unrepaired DNA damage and genomic instability. As patients age, progressive bone marrow failure occurs in 90% by age 40 (2).

Although anemia appears at a median of 7 years of age, evidence has been accumulating that defects in hematopoiesis occur earlier in development. It has been hypothesized insufficient seeding of the bone marrow from FA fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) leads to bone marrow failure later in life. This implies that the buildup of DNA damage over time is not solely responsible for hematopoietic dysfunction and that FA cells possess additional intrinsic pathophysiologic properties (3,5). From very early childhood, prior to declines in peripheral blood counts, FA patients have low CD34+ bone marrow populations suggesting loss of bone marrow function has been occurring from the fetal period (3,6). Fetal defects have been found to be exacerbated by endogenous aldehydes and Aldh2 deletion within murine Fanca or Fancd2 knockout (KO) embryos was shown to cause a reduction in hematopoiesis that extended into adulthood (7,8). Examination of a mouse Fancc KO model demonstrated defects in fetal liver hematopoiesis including low total cellularity and poor transplantability (9). Total HSC numbers in the Fancc KO fetal liver, however, were found to be preserved, similar to findings in young adult Fancc KO bone marrow (10,11)

In contrast, adult Fancd2 KO murine bone marrow has a more severe phenotype, demonstrating earlier HSC loss and reduced competitive repopulation ability in comparison to adult Fancc KO bone marrow (10–13). The more severe Fancd2 KO phenotype may result from the central coordinating function of Fancd2 in FA pathways for which upstream FA proteins, such as Fancc serve to regulate (5,14). This raises the possibility that there might be distinct differences within Fancd2 KO fetal hematopoiesis contributing to defects within Fancd2 KO adult bone marrow. We therefore investigated the immunophenotypic and functional effects of Fancd2 deletion on the fetal liver and the HSC compartment in order to define the early consequences of Fancd2 loss on embryonic hematopoiesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Fancd2 KO mice were obtained and PCR genotyped as previously described (15). Mice were maintained as heterozygotes in a pure C57BL/6 background. Wild-type C57BL/6 CD45.2 mice were bred with B6.SJL CD45.1 mice to generate CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygote mice used as competitors in transplantation studies. CD45.2 C57BL/6 mice and CD45.1 B6.SJL recipient mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. All animal studies were carried out in accordance with and with approval from the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow Cytometry

Lineage, c-Kit, Sca-1 and CD34 staining was performed as previously described and run on a BD Biosciences LSR II flow cytometer (16). Analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar). For γH2AX analysis, cells were surface-stained and then fixed and stained using Cytofix/Cytoperm and Perm Plus buffer (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with anti-H2AX pS139-PE or control antibody (BD Biosciences). For apoptosis analysis, cells were surface-stained and then stained according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the PE Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences). Peripheral blood flow cytometry was performed as previously described using anti-CD45.1-PE, anti-CD45.2-FITC or anti-CD45.2 APC, anti-Gr1-APC-Cy7, and anti-Mac-1-PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences) (16). 7-AAD was used to differentiate between live and dead cells in all experiments (BD Biosciences).

Bone marrow/fetal liver transplantation

Competitive repopulation studies were performed as previously described (16). Briefly, 1 × 106 CD45.2 donor and 1 × 106 CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygote competitor bone marrow or 5 × 105 CD45.2 donor and 5 × 105 CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygote competitor bone marrow were injected into tail veins of CD45.1 homozygous mice treated with 1100 rads split-dose γ-irradiation in a cesium irradiator. Peripheral blood chimerism was monitored through nonlethal facial vein bleeding every 4 weeks for a total of 16 weeks. After 16 weeks post-transplantation the mice were sacrificed and engraftment was examined by flow cytometry.

Colony assays

Whole fetal liver was isolated from E14.5 embryos and passed through a 100μm mesh-filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to create a single cell suspension. A total of 25,000 cells were duplicate plated in M3434 methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies) containing erythropoietin, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7 days. Colonies were scored using an Eclipse TS100 inverted light microscope (Nikon) with a gridded plate and identified by morphology per the manufacturer’s instructions. Mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the methylcellulose prior to the addition of cells.

Telomere length qPCR

Fetal liver cells were harvested for DNA using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). DNA concentration and quality was recorded using Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer. Telomere length quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using SSO Advanced SYBR Green (Biorad) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad) using the protocol reported by Callicott, et al (17). Forward and Reverse telomere primers used were 5′ CGG TTT GTT TGG GTT TGG GTT TGG GTT TGG GTT TGG GTT 3′ and 5′ GGC TTG CCT TAC CCT TAC CCT TAC CCT TAC CCT TAC CCT 3′. The housekeeping gene used was acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein PO (36B4) gene. Forward and Reverse 36B4 primers used were 5′ ACT GGT CTA GGA CCC GAG AAG 3′ and 5′ TCA ATG GTG CCT CTG GAG ATT 3′.

LT-HSC gene expression

Fetal livers were harvested, genotyped, and stained for LSK cells as above. Cells were sorted to collect LT-HSC (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, CD34−) on a BD FACSVantage DV-1 Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). Cells were directly sorted into Qiazol (Qiagen) for RNA isolation. The samples were then processed using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) as instructed by the manual, including on-column DNase I treatment (RNase-free DNase Set, Qiagen). The eluted RNA was processed into cDNA using the Sensiscript RT Kit (Qiagen) as instructed. Quantitative PCR was performed for downstream targets of p53 activation using SSO Advanced SYBR Green (Biorad) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Biorad) using Gapdh as a housekeeping gene. Primer sequences for qPCR are as follows: Gapdh Fwd 5′ GGA GCC AAA CGG GTC ATC ATC TC 3′, Rev 5′ GAG GGG CCA TCC ACA GTC TTC T 3′; Puma Fwd 5′ GCT GAA GGA CTC ATG GTG AC 3′, Rev 5′ CAA AGT GAA GGC GCA CTG 3′; Bax Fwd 5′ GGC TGG ACA CTG GAC TTC CT 3′, Rev 5′ GGT GAG GAC TCC AGC CAC AA 3′; p21cip Fwd 5′ CCT GGT GAT GTC CGA CCT G 3′, Rev 5′ CCA TGA GCG CAT CGC AAT C 3′.

Statistical Analysis

Bar graphs were generated using Excel (Microsoft). Scatter plots were generated using Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software). A two-sided Student’s t-test was used to determine significance with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Embryonic loss of Fancd2 results in decreased fetal liver hematopoiesis and HSC populations

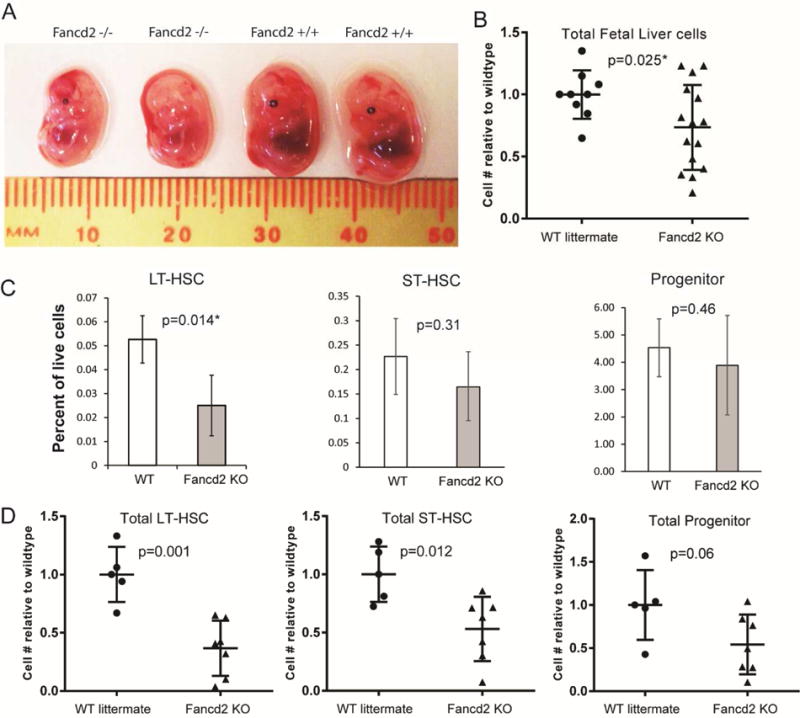

To examine hematopoiesis in Fancd2−/− (KO) embryos, timed matings were performed using fully back-crossed C57BL/6 Fancd2+/− heterozygous breeders. Fancd2−/− homozygous animals have documented infertility issues (15). Decreased numbers of Fancd2 KO pups (16.5% of 303 total) have been previously observed in the C57BL/6 background when measured at P+5 (15). Nevertheless, Chi-squared analysis showed no significant difference between expected and observed embryo numbers at E14.5. Fancd2 KO embryos were produced at the expected Mendelian ratio (d.f.=3, χ2=1.6, p>0.5) suggesting lethality occurs during late embryonic development or in the immediate post-natal period (Table 1). We observed that Fancd2 KO embryos were frequently smaller than wildtype embryos and often had small or absent eyes (Figure 1A), a defect commonly seen in adult Fancd2 mice and human Fanconi Anemia patients (4,15).

Table 1.

Fancd2 KO embryos are present in expected numbers at E14.5. Timed matings were performed between Fancd2 +/− heterozygotes and harvested at 14.5 days post-conception. Embryos were individually genotyped by PCR (n=71).

| Genotype | Fancd2 −/− | Fancd2 +/− | Fancd2 +/+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Number | 19 | 37 | 15 |

| Expected Number | 17.75 | 35.5 | 17.75 |

| Actual Percent | 27% | 52% | 21% |

| Expected Percent | 25% | 50% | 25% |

Figure 1. Fancd2 KO embryos have reduced hematopoiesis.

A) Photograph of E14.5 littermate embryos. Genotypes listed above. B) Ratio of Fancd2 KO E14.5 fetal liver cells relative to WT littermates. Fetal livers from E14.5 timed matings were extracted, disaggregated into a single cell suspension and then counted on a hemocytometer using trypan blue viability stain. WT n=9; Fancd2 KO n=15. C) Percent of live fetal liver cell number from WT and Fancd2 KO E14.5 embryos fractionated using markers for LT-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-Kit+CD34neg), ST-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-kit+Cd34+) and Progenitor (LinnegSca1−c-Kit+) populations. D) Absolute cell number of E14.5 embryo populations in C relative to mean of WT littermates. WT, n=5; Fancd2, n=7.

Total cellularity of E14.5 Fancd2 fetal livers was reduced to 73% of WT littermates (Figure 1B), a finding comparable to that observed in Fancc KO embryos (9). Further characterization into long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) (LineagenegSca1+c-Kit+CD34neg), short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs) (LineagenegSca1+c-Kit+CD34+), which includes multipotent progenitors and myeloid progenitors (LineagenegSca1negc-Kit+) demonstrated a significantly reduced percentage of LT-HSCs in Fancd2 KO fetal livers along with a ~50% reduction in absolute numbers of LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs relative to WT (Figure 1 C&D). Absolute numbers of progenitors were reduced but did not achieve statistical significance. Adult Fancd2 KO bone marrow similarly has been shown to have fewer LT-HSCs, unlike Fancc KO E14.5 fetal livers and young adult bone marrow which had no change in the HSC population (9–12,18). Overall, loss of Fancd2 reduces total hematopoiesis within the fetal liver, particularly within the HSC compartment, providing an informative model to study Fancd2’s essential role in fetal HSCs.

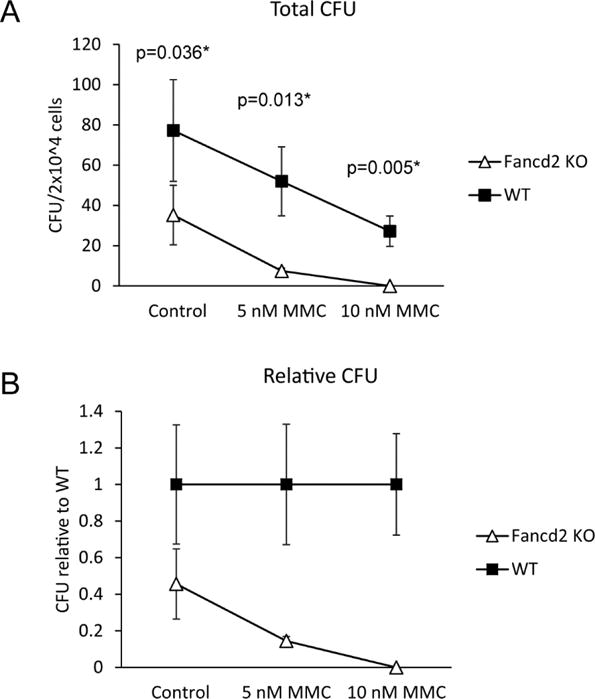

Fancd2 fetal livers have fewer CFUs, are highly sensitive to mitomycin C and poorly compete in short- and long-term engraftment

Next, we sought to define the functional defects of Fancd2 loss on fetal hematopoiesis. The colony forming unit (CFU) assay provides a functional assay for progenitor cell number and ability to differentiate. E14.5 Fancd2 KO fetal livers had 40% of the CFU observed with the WT littermates (Figure 2 A&B Control). This reduction is comparable to the observed CFU of adult Fancd2 KO bone marrow (~50% of WT) yet greater than observed with E14.5 Fancc fetal livers (80% of WT) (9,12). CFU formation is a highly responsive indicator for ISL sensitivity, a defining defect for FA cells. Treatment with the ISL agent, mitomycin C (MMC) greatly reduced E14.5 Fancd2 KO fetal liver CFU numbers. Increasing concentrations of MMC reduced Fancd2 KO CFU numbers at a rate greater than WT littermate fetal livers (Figure 2A&B).

Figure 2. Fancd2 KO fetal livers have fewer CFUs and are highly sensitive to mitomycin C (MMC).

A) Colonies obtained after plating 2×104 cells from E14.5 Fancd2 KO or WT embryonic fetal livers in methylcellulose media for 7 days containing DMSO control or the indicated concentration of MMC. B) CFU numbers from A as a relative ratio to WT colony numbers. WT n=4; Fancd2 KO n=4.

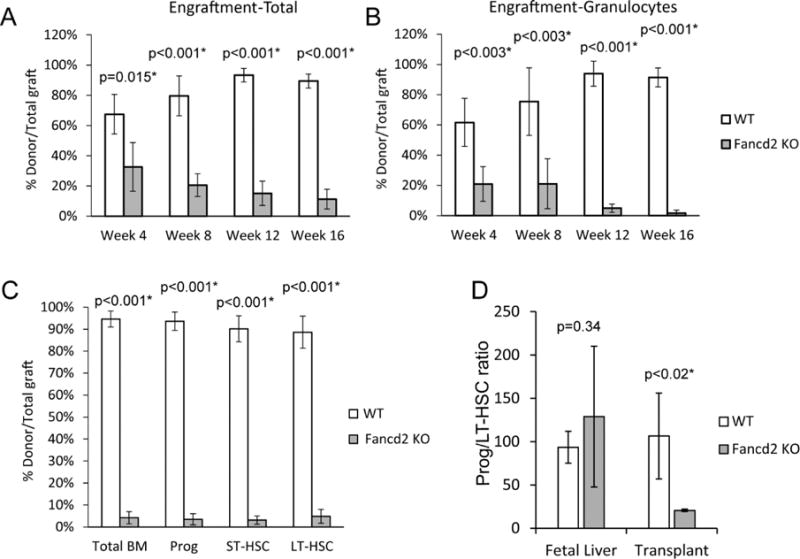

To determine if HSC function was perturbed, competitive repopulation using Fancd2 KO fetal livers was performed. The ability to competitively repopulate a lethally irradiated recipient over time provides a definitive in vivo assessment of HSC function. E14.5 Fancd2 KO or WT CD45.2 littermate fetal liver cells were injected along with a 1:1 mix of CD45.2/CD45.1 competitor bone marrow into the tail veins of CD45.1 recipients. The animals were followed for 16 weeks with monthly facial vein sampling of peripheral blood CD45+ leukocytes to determine the ratio of donor:competitor. The Fancd2 KO fetal liver had ~50% less short-term engraftment against competitor than WT cells at 4 weeks, with a steady decline to only 12% of WT cells (Figure 3A). Fetal liver is known to engraft more effectively than bone marrow, which explains the higher levels of WT engraftment over competitor bone marrow (19). The ratio of donor:competitor within the granulocyte population (Mac1+Gr1+) was also determined as the shorter-lived granulocytes provide a better surrogate of HSC output (20). Fancd2 KO granulocyte chimerism was only 34% of WT engraftment at 4 weeks and less than 2% of WT at 16 weeks (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Fancd2 KO fetal livers have severely reduced competitive repopulation ability.

Lethally irradiated recipients were transplanted with E14.5 Fancd2 KO or WT fetal livers plus an equal number of competitor adult bone marrow cells. A) Percent peripheral blood chimerism of all indicated donor cells relative to total graft over time. B) Percent peripheral blood chimerism of granulocyte donor cells relative to total graft granulocytes over time. C) Percent of bone marrow chimerism of donor cell populations LT-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-Kit+CD34neg), ST-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-Kit+CD34+), Progenitor (LinnegSca1negc-kit+) and total at 16 weeks post-transplant (WT n=5; Fancd2 KO n=5). D) Ratio of myeloid progenitor/LT-HSC in E14.5 fetal livers (WT n=5; Fancd2 KO=6) and 16 week post-transplant donor bone marrow population (WT n=5; Fancd2 KO=3).

Analysis of the recipient total bone marrow at 16 weeks demonstrated Fancd2 KO chimerism at 4% of WT engraftment. Sub-fractionation of Fancd2 KO LT-HSC, ST-HSC and progenitor populations showed 4% or less of WT engraftment. Total Fancd2 donor percentage in peripheral blood was observed to be higher than in the granulocyte population. To assess whether myeloid production was affected in the transplanted donor population, the ratio of myeloid progenitors (Lin−Sca1−c-Kit+) per LT-HSC was compared. While no significant difference in the Progenitor:LT-HSC ratio was seen between the WT and Fancd2 KO fetal livers or the WT 16 weeks post-transplant cohort, there was almost a 5-fold decrease in the Fancd2 KO donor cells 16 weeks post-transplant suggesting a loss of myeloid potential. Collectively our data in vitro and in vivo indicate that by E14.5, Fancd2 KO fetal livers already possess most of the profound defects similar to adult Fancd2 KO bone marrow (12).

Fancd2 fetal livers have elevated DNA damage and have high levels of apoptosis specific to the LT-HSC compartment

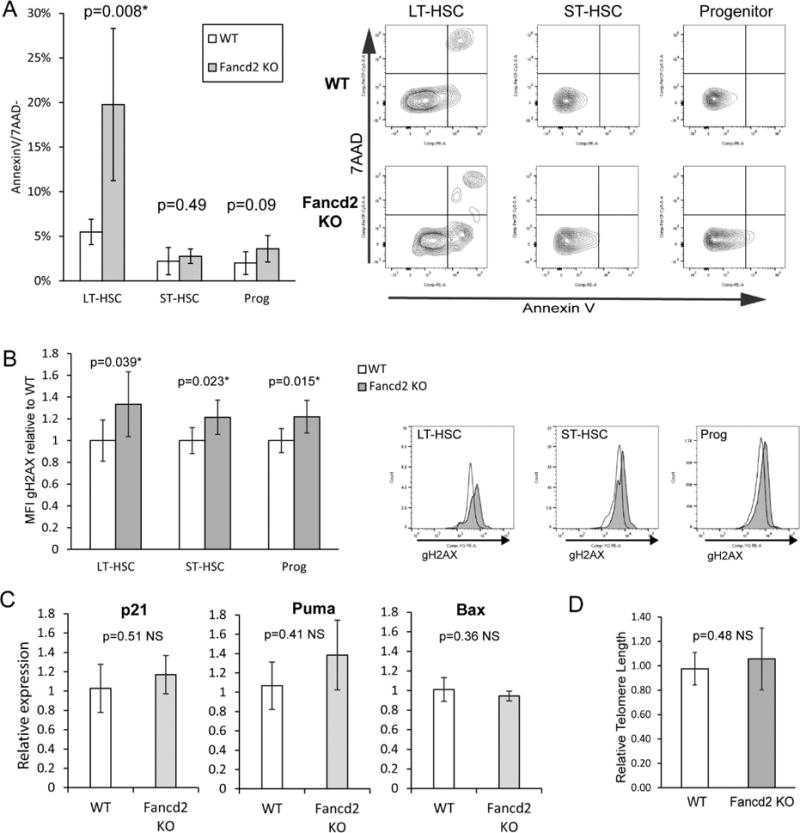

A reported mechanism for HSC loss in Fancd2 KO adult bone marrow is higher levels of apoptosis in the LT-HSC compartment (12). However, previous analysis of Fancc fetal liver HSCs did not show elevated levels of apoptosis, although the markers AA4.1+/Sca1+ were used, which would have included the more numerous ST-HSC population (9). We analyzed the amount of active apoptosis (AnnexinV+7AAD−) occurring in E14.5 Fancd2 KO fetal liver HSC subpopulations and found significantly higher levels of apoptosis in the Fancd2 KO LT-HSC population compared to WT (20% vs. 5% respectively) (Figure 4A). ST-HSC and progenitor populations, however, did not have a significant increase in apoptosis.

Figure 4. Fancd2 KO fetal liver HSCs have elevated rates of apoptosis and DNA damage, but normal telomere lengths.

A) Percentage of LT-HSC, ST-HSC and Progenitor populations of E14.5 WT and Fancd2 KO staining Annexin V+/7AAD−. Representative flow panels on right. WT n=5; Fancd2 KO n=6. B) Flow cytometry measuring γH2AX levels. E14.5 WT and Fancd2 KO littermate fetal livers were harvested and stained for LT-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-kit+CD34neg), ST-HSC (LinnegSca1+c-Kit+CD34+) and Progenitor (LinnegSca1−c-Kit+) populations followed by fixation/permeabilization then staining for γH2AX. Graph reports ratio of γH2AX MFI relative to the average MFI of WT littermates. Representative flow panels below. WT white; Fancd2 KO gray. WT n=5; Fancd2 KO n=7. C) p53-dependent gene expression in E14.5 fetal liver LT HSCs. Relative gene expression of p21, Puma and Bax was determined by quantitative RT-PCR of RNA from flow sorted LT-HSCs of WT and Fancd2 KO E14.5 fetal livers (WT n=4; Fancd2 KO n=2). D) Relative telomere lengths of WT and Fancd2 E14.5 fetal livers. Q-PCR was performed on genomic DNA from WT and Fancd2 KO E14.5 fetal livers using mouse telomere specific primers and normalized against 36B4 genomic primer products. WT n=4; Fancd2 KO n=8.

Due to the presence of increased DNA damage observed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in adult bone marrow from Fancd2 and additional FA group KO mice, we wanted to determine whether elevated DNA damage was present at baseline in the fetal HSC compartment (12,21). Different cell populations was measured using flow cytometry for γH2AX. Significant elevations in γH2AX were observed in LT-HSC, ST-HSC and progenitor populations from E14.5 Fancd2 fetal livers relative to WT levels (Figure 4B). Therefore, although elevated DNA damage is present in HSC and progenitor populations, only LT-HSCs had concurrently elevated levels of apoptosis.

To determine whether the increased apoptosis within the Fancd2 KO LT-HSC compartment was mediated by p53, we examined gene expression in sorted LT-HSC populations. P21, Puma and Bax RNA expression levels were examined by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 4C)(22). Neither p21, Puma nor Bax showed any significant change, suggesting a p53-independent mechanism.

Defective telomere maintenance has been proposed as contributing to the phenotype of FA and Fancd2 knockdown in mouse cells has been shown to result in telomere shortening (23–25). LT-HSCs appear acutely sensitive to telomere shortening, which can result in arrest or apoptosis (26). A quantitative PCR analysis measuring telomere length was used to examine DNA from E14.5 Fancd2 KO fetal liver cells and showed no significant difference compared to WT (Figure 4D) suggesting telomere loss is not a major issue in the Fancd2 KO fetal liver hematopoietic phenotype.

Discussion

We have shown Fancd2 deletion has significant impact on overall fetal liver hematopoiesis, especially in the HSC compartment. Total fetal liver cellularity in the Fancd2 KO showed a decrease in comparison to WT. The decrease is most apparent within the LT-HSC compartment, in which Fancd2 KO fetal livers manifest sizeable decreases in both the percentage and absolute number of LT-HSCs and to a lesser extent ST-HSC absolute numbers. It is hypothesized that reduced seeding of the adult bone marrow in FA patients from the fetal liver is an etiologic mechanism for bone marrow failure potentially resulting from a limiting number of HSCs available to move from the fetal liver to the bone marrow (3,9). Although adult Fancd2 KO bone marrow also displays a decrease in LT-HSCs, total bone marrow cellularity remains normal (12). Possible explanations for this cellularity difference with bone marrow could be the higher proliferative stress in the fetal liver, distinct expansion kinetics or a unique role for Fancd2 in fetal liver hematopoietic expansion (3). Functionally, Fancd2 KO fetal liver behaved similar to Fancd2 KO adult bone marrow, displaying MMC sensitivity, reduced CFUs and dramatically impaired long-term competitive repopulation. While the production of Fancd2 KO myeloid progenitors from LT-HSCs was similar to WT in the fetal liver, long-term transplantation demonstrated a significant decrease in the progenitor:LT-HSC ratio. The reduced output argues that myeloid potential or differentiation capacity may be affected by either the stress of transplantation or aging. Overall, Fancd2 fetal liver LT-HSCs recapitulate many key defects observed in Fancd2 adult mice without accumulated age-related DNA damage, however, myeloid differentiation capacity may demonstrate progressive loss with stress or age.

At baseline, we observed elevated levels of DNA damage in both HSC and progenitor fractions of the E14.5 Fancd2 KO fetal liver, consistent with the basal levels of DNA damage described in Fancd2 and other complementation group KO models (12,21). Despite shared DNA damage, we only observed higher levels of apoptosis within the Fancd2 KO LT-HSC population, suggesting a cell context-specific sensitivity. Quiescent HSCs from FA patients have been shown to respond to DNA damage through arrest and apoptosis via induction of p53/p21 pathways and can be rescued through p53 depletion (27). FA fetal liver samples were also observed to have expression consistent with p53-mediated arrest and endogenous aldehyde production has been proposed as a major cause of FA-associated DNA damage in utero (8,13,21). Embryonic apoptosis has also been observed occurring in a p53-independent fashion and our data suggests classical p53-mediated transcriptional pro-apoptotic targets are not activated (28) Apoptosis may also be alternatively enhanced in FA HSCs through hypersensitivity to TGF-β-promoted non-homologous end joining repair of DNA damage (29). Our data, therefore, suggests apoptosis within the LT-HSC population may be the mechanism underlying the reduction in fetal hematopoiesis in the Fancd2 KO model, however potentially through a p53-independent mechanism.

Telomere shortening has been proposed as a mechanism for induction of DNA damage and apoptosis in FA HSCs, ultimately leading to HSC exhaustion and bone marrow failure (23,24,30). Measurement of telomere length in peripheral blood leukocytes from FA patients over time revealed a progressive decline in telomere length compared to controls (23). Studies using Tert/mTerc KO mice have shown increases in DNA damage and apoptosis specifically in HSCs and impairment of competitive repopulation (26,31). Fancd2 was found to be specifically crucial for telomere maintenance involving the homologous recombination-mediated Alternative Lengthening of Telomere (ALT) process (24). However, we found no significant difference in telomere length between Fancd2 KO and WT fetal livers. Therefore, it is unlikely telomere dysfunction is responsible for fetal hematopoietic defects, including increased HSC apoptosis, decreased cellularity and impaired function such as lower CFU formation and poor competitive repopulation. It is possible, however, that telomere dysfunction plays a role in defects in long-term engraftment of Fancd2 KO fetal liver cells.

In contrast to our observations in Fancd2 KO embryos, a study of Fancc KO fetal livers reported preserved HSC numbers and no increase in apoptosis (9). In the Fancc study, however, broader immunophenotypic populations were used to define HSCs which would include ST-HSC as well, thus potentially masking apoptosis and cell numbers within the less numerous LT-HSC population. An alternative explanation would be that Fancd2, as a proximal effector of FA complex-mediated DNA repair, has a more penetrant phenotype. Another reason for the disparity could be related to non-DNA repair dependent functions of either Fancd2 or Fancc (5). In support of the two latter possibilities, Fancd2 KO adult bone marrow has a more severe LT-HSC deficit and transplantation defect in comparison to the Fancc KO (10,12).

In summary, the fetal liver of Fancd2 KO embryos displays several key manifestations of Fancd2-deficient bone marrow including reduced CFU formation, impaired competitive repopulation and elevated DNA damage. Fancd2 KO LT-HSCs are conspicuously affected with reduced numbers and increased apoptosis, which are notable differences from the Fancc fetal liver phenotype. The defects present in Fancd2 KO fetal liver hematopoiesis arise, with the exception of myeloid progenitor production, in the absence of aging. Therefore, they are intrinsic to Fancd2 loss rather than acquired over time, supporting the hypothesis of in utero origins of bone marrow failure in FA. The reduced total cellularity of Fancd2 KO fetal livers may also provide a more robust mouse model for study whereas adult Fancd2 KO and other FA complex KO mouse models fail to independently manifest hypocellularity of the bone marrow.

Highlights.

Fancd2 loss reduces fetal liver hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) numbers

Fetal Fancd2 KO HSCs have elevated levels of apoptosis and DNA damage

Fetal Fancd2 KO HSCs have functional defects comparable to adult Fancd2 bone marrow

Fancd2 loss on HSCs has intrinsic defects independent of aging-related damage

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Janet Stavnezer with the Fancd2 mice. S.C. was supported in part by the NCI (R01 CA176166-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Khincha PP, Savage SA. Genomic characterization of the inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Semin Hematol. 2013;50(4):333–47. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taniguchi T, D’Andrea AD. Molecular pathogenesis of Fanconi anemia: recent progress. Blood [Internet] 2006 Jun 1;107(11):4223–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4240. [cited 2014 Aug 8] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16493006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garaycoechea JI, Patel KJ. Why does the bone marrow fail in Fanconi anemia? Blood. 2014;123(1):26–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-427740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khincha PP, Savage SA. Neonatal manifestations of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2016;21:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceccaldi R, Sarangi P, D’Andrea AD. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol [Internet] 2016 doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.48. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nrm.2016.48\nhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27145721. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kelly PF, Radtke S, von Kalle C, Balcik B, Bohn K, Mueller R, et al. Stem cell collection and gene transfer in Fanconi anemia. Mol Ther [Internet] 2007;15(1):211–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300033. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17164793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garaycoechea JI, Crossan GP, Langevin F, Daly M, Arends MJ, Patel KJ. Nature [Internet] 7417. Vol. 489. Nature Publishing Group; 2012. Sep 27, Genotoxic consequences of endogenous aldehydes on mouse haematopoietic stem cell function; pp. 571–5. [cited 2014 Jul 25] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22922648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langevin F, Crossan GP, Rosado IV, Arends MJ, Patel KJ. Fancd2 counteracts the toxic effects of naturally produced aldehydes in mice. Nature. 2011;475(7354):53–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamimae-Lanning AN, Goloviznina NA, Kurre P. Fetal origins of hematopoietic failure in a murine model of Fanconi anemia. Blood. 2013;121(11):2008–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-439679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haneline LS, Gobbett TA, Ramani R, Carreau M, Buchwald M, Yoder MC, et al. Loss of FancC function results in decreased hematopoietic stem cell repopulating ability. Blood. 1999;94(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreau M, Gan OI, Liu L, Doedens M, Dick JE, Buchwald M. Hematopoietic compartment of Fanconi anemia group C null mice contains fewer lineage-negative CD34+ primitive hematopoietic cells and shows reduced reconstitution ability. Exp Hematol. 1999;27(11):1667–74. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parmar K, Kim J, Sykes SM, Shimamura A, Stuckert P, Zhu K, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell defects in mice with deficiency of Fancd2 or Usp1. Stem Cells. 2010;28(7):1188–95. doi: 10.1002/stem.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakker ST, de Winter JP, te Riele H, Banerjee S, Flores-Rozas H, Casorelli I, et al. Cell Stem Cell [Internet] 1. Vol. 11. Nature Publishing Group; 2012. Aug 1, Bone marrow failure in fanconi anemia is triggered by an exacerbated p53/p21 DNA damage response that impairs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells; pp. 36–49. [cited 2014 Aug 8] Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulliam-Leath AC, Ciccone SL, Nalepa G, Li X, Si Y, Miravalle L, et al. Genetic disruption of both Fancc and Fancg in mice recapitulates the hematopoietic manifestations of Fanconi anemia. Blood [Internet] 2010 Oct 21;116(16):2915–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240747. [cited 2014 Aug 8] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2974601&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houghtaling S, Timmers C, Noll M, Finegold MJ, Jones SN, Stephen Meyn M, et al. Epithelial cancer in Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (Fancd2) knockout mice. Genes Dev. 2003;17(16):2021–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1103403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao N, Jani K, Morgan K, Okabe R, Cullen DE, Jesneck JL, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells lacking Ott1 display aspects associated with aging and are unable to maintain quiescence during proliferative stress. Blood [Internet] 2012 May 24;119(21):4898–907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403089. [cited 2014 Aug 6] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3367894&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callicott RJ, Womack JE. Real-time PCR assay for measurement of mouse telomeres. Comp Med. 2006;56(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang QS, Marquez-Loza L, Eaton L, Duncan AW, Goldman DC, Anur P, et al. Fancd2−/− mice have hematopoietic defects that can be partially corrected by resveratrol. Blood. 2010;116(24):5140–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szilvassy SJ, Meyerrose TE, Ragland PL, Grimes B. Differential homing and engraftment properties of hematopoietic progenitor cells from murine bone marrow, mobilized peripheral blood, and fetal liver. Blood [Internet] 2001 Oct 1;98(7):2108–15. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2108. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11567997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller CL, Dykstra B, Eaves CJ. Characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Curr Protoc Immunol [Internet] 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22b02s80. Chapter 22:Unit 22B 2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18432636. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Oberbeck N, Langevin F, King G, deWind N, Crossan GP, Patel KJ. Maternal Aldehyde Elimination during Pregnancy Preserves the Fetal Genome. Mol Cell. 2014;55(6):807–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pant V, Quintás-Cardama A, Lozano G. The p53 pathway in hematopoiesis: lessons from mouse models, implications for humans. Blood [Internet] 2012 Dec 20;120(26):5118–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-356014. [cited 2014 Aug 6] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3537308&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leteurtre F, Li X, Guardiola P, Le Roux G, Sergere JC, Richard P, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening and telomerase activation in Fanconi’s anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999;105(4):883–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spardy N, Duensing A, Hoskins EE, Wells SI, Duensing S. HPV-16 E7 reveals a link between DNA replication stress, Fanconi anemia D2 protein, and alternative lengthening of telomere-associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9954–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan Q, Zhang F, Barrett B, Ren K, Andreassen PR. A role for monoubiquitinated FANCD2 at telomeres in ALT cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(6):1740–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Lu X, Sakk V, Klein CA, Rudolph KL. Senescence and apoptosis block hematopoietic activation of quiescent hematopoietic stem cells with short telomeres. Blood. 2014;124(22):3237–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-568055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceccaldi R, Parmar K, Mouly E, Delord M, Kim JM, Regairaz M, et al. Bone marrow failure in Fanconi anemia is triggered by an exacerbated p53/p21 DNA damage response that impairs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell [Internet] 2012 Jul 6;11(1):36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.013. [cited 2014 Aug 5] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3392433&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gladdy RA, Nutter LMJ, Kunath T, Danska JS, Guidos CJ. p53-Independent apoptosis disrupts early organogenesis in embryos lacking both ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and Prkdc. Mol Cancer Res [Internet] 2006;4(5):311–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0258. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16687486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Kozono DE, O’Connor KW, Vidal-Cardenas S, Rousseau A, Hamilton A, et al. TGF-β Inhibition Rescues Hematopoietic Stem Cell Defects and Bone Marrow Failure in Fanconi Anemia. Cell Stem Cell [Internet] 2016;18(5):668–81. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.002. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1934590916001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bakker ST, de Winter JP, te Riele H. Learning from a paradox: recent insights into Fanconi anaemia through studying mouse models. Dis Model Mech [Internet] 2013;6:40–7. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009795. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3529337&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahin E, Colla S, Liesa M, Moslehi J, Müller FL, Guo M, et al. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature [Internet] 2011 Feb 17;470(7334):359–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09787. [cited 2014 Jul 10] Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3741661&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]