Abstract

Vitamin D plays a critical role in skeletal homeostasis. Vitamin D supplementation is used worldwide to maintain optimal bone health, but the most appropriate level of supplementation remains controversial. This study aimed to determine the effects of varying doses of dietary vitamin D3 on the mechanical properties and morphology of growing bone.

Eight-week-old female mice were supplied with one of 3 diets, each containing a different dose of vitamin D3: 1000 IU/kg (control), 8000 IU/kg or 20,000 IU/kg. Mice had ad libitum access to the specialty diet for 4 weeks before they were culled and their tibiae collected for further analysis. The collected tibia underwent three-point bending and reference-point indentation from which their mechanical properties were determined, and cortical and trabecular morphology determined by micro computed tomography.

Dietary supplementation with 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 resulted in greater ductility (~ 200%) and toughness (~ 150%) compared to the 1000 IU/kg control. The 20,000 IU/kg diet was also associated with significantly greater trabecular bone volume fraction and trabecular number. The 8000 IU/kg diet had no significant effect on trabecular bone mass.

We conclude that vitamin D3 supplementation of 20,000 IU/kg during early adulthood leads to tougher bone that is more ductile and less brittle than that of mice supplied with standard levels of dietary vitamin D3 (1000 IU/kg) or 8000 IU/kg. This suggests that dietary vitamin D3 supplementation may increase bone health by improving bone material strength and supports the use of vitamin D3 supplementation, during adolescence, for achieving a higher peak bone mass in adulthood and thereby preventing osteoporosis.

Keywords: Vitamin D3, 3 point bending, Cholecalciferol, Bone strength

Highlights

-

•

Vitamin D plays a critical role in skeletal homeostasis.

-

•

Dietary supplementation with 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 resulted in greater ductility and toughness.

-

•

The 20,000 IU/kg diet was also associated with significantly greater trabecular bone volume fraction and trabecular number.

1. Introduction

It is generally established that vitamin D3 is crucial for bone health through its actions as a regulator of minerals, and in turn, skeletal homeostasis in vertebrates (Anderson et al., 2011). Deficiencies in vitamin D3 during childhood can have significant health consequences such as growth retardation (Rajakumar, 2003) and detrimental effects on bone mineral acquisition (Lehtonen-Veromaa et al., 2002) and bone remodelling (Outila et al., 2001, Cheng et al., 2003, Fares et al., 2003) leading to rickets (O'Riordan and Bijvoet, 2014). These consequences in adolescence are also a significant risk factor for the development of osteoporosis later in life (Dawson-Hughes et al., 1991, Lips, 2001).

The effects of vitamin D3 as a treatment for osteoporosis in adulthood are controversial. Conflicting reports suggests vitamin D3 supplementation in adulthood reduces (Bischoff-Ferrari et al., 2005, Tang et al., 2007), has no effect (Michaëlsson et al., 2003), or increases the incidence of osteoporotic fractures (Smith et al., 2007, Sanders et al., 2010). By comparing and normalising 23 separate studies, Reid et al. (2013) found that vitamin D supplementation was not effective in reducing fracture risk in those not experiencing vitamin D deficiency.

An alternative strategy for preventing osteoporosis is to optimise peak bone mass during growth via vitamin D3 supplementation during adolescence. A number of intervention studies examining the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation in adolescents have reported significant increases in bone mineral content (BMC) (El-Hajj Fuleihan et al., 2006, Viljakainen et al., 2006) and bone mineral density (BMD) (Du et al., 2004), while other studies have reported no beneficial effects (Andersen et al., 2008). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Winzenberg et al., 2010, Winzenberg et al., 2011) have concluded that vitamin D3 supplementation during adolescence had no significant effect on BMC and BMD, however there has been no randomised controlled trial to assess the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on bone health. Currently the recommended daily intake of vitamin D3 in infants, children and adolescents is 400 IU (Wagner and Greer, 2008). This dosage is based on clinical trials measuring biomarkers of vitamin D3 status and the indirect observations that 400 IU of vitamin D3 prevents and treats rickets (Wagner et al., 2006, Rajakumar and Thomas, 2005).

It is clear that there is a need for further investigation into the effect of vitamin D3 dietary supplementation on bone mass in a model of growing bone where subjects are vitamin D3 replete. Therefore, our objective was to determine whether increasing dietary vitamin D3 levels (8000 and 20,000 IU/kg) above the standard levels (1000 IU/kg) significantly alters bone mass and strength in growing mice.

2. Methods and animals

2.1. Animals

7 week old female C57Bl/6 J mice were obtained from Monash Animal Services, Victoria and housed in a temperature and humidity controlled environment on a 12 h light/dark cycle. All animal work was approved by Victoria University Animal Ethics Committee. All animals were fed on standard growth diet (AIN-93G, containing 0.47% calcium (Ca), 0.35% phosphate (PO4), vitamin D3 1000 IU/kg) from weaning until 8 weeks of age, at which point the animals were randomly allocated to one of three diets for a period of 4 weeks. These diets were modified AIN-93G diets supplemented with set concentrations of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) as follows: control (1000 IU/kg, n = 10), 8000 IU/kg (n = 10) or 20,000 IU/kg (n = 7). The animals had ad libitum access to both food & water. All animals consumed the same amount of food (average of 2.5 g per day, no significant difference between groups). At 12 weeks of age, the mice were deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg injection i.p.), killed by cervical dislocation, and their tibiae harvested. Tibiae were carefully dissected free from soft tissues; lengths measured with a digital caliper, and stored at − 80 °C prior to mechanical testing and further analysis.

2.2. Micro computed tomography (μCT)

Tibiae were analyzed by micro-computed tomography as described previously (Johnson et al., 2014) using the SkyScan 1076 System (Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium). Images were acquired using the following settings: 9 μm voxel resolution, 0.5 mm aluminium filter, 44 kV voltage, and 220 μA current, 2300 ms exposure time, rotation 0.5°, frame averaging = 1. The images were reconstructed and analyzed using SkyScan Software programs NRecon (version 1.6.3.3), DataViewer (version 1.4.4), and CT Analyser (version 1.12.0.0) as previously described (Johnson et al., 2014).

CTAn software was then used to select the regions of interest for both the cortical (CTAn version 1.15.4.0) and trabecular (CTAn version 1.11.8.0) bone of each scan. Trabecular region of interest (ROI) was selected as a 2 mm region starting 0.5 mm below the proximal growth plate. Cortical ROI was selected as a 1 mm region starting 7 mm below the growth plate. The cortical ROI was chosen such that the middle of the ROI corresponded with the point at which load was applied to the bones in the three-point bending experiments.

The analysis of bone structure was completed using adaptive thresholding (mean of min and max values) in CT Analyser. The thresholds for analysis were determined based on multilevel Otsu thresholding of the entire data set, and were set at 45–255 for trabecular bone and 71–255 for cortical bone.

2.3. Three point bending

Each tibia was rehydrated overnight in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature prior to testing. To determine the mechanical properties of cortical bone each tibia was loaded to failure at 0.5 mm/s using a Bose Biodynamic 5500 Test Instrument (Bose, DE, USA). The span between the lower supports was 10 mm. Prior to testing, the tibiae were kept moist in gauze swabs soaked in PBS. Bones were positioned such that the load was applied 8.75 mm from the top of distal condyle in the anterior-posterior (AP) direction with distal condyle facing downwards (Supplementary Fig. 1). Wintest software (WinTest 7) was used to collect the load-displacement data across 10 s with a sampling rate of 250 Hz. Structural properties including Ultimate force (FU; N), yield force (FY; N), stiffness (S; N/mm), and energy (work) to failure (U; mJ) (Johnson et al., 2014) endured by the tibia were calculated from the load and displacement data as outlined in Jepsen et al. (2015). The yield point was determined from the load displacement curve at the point at which the curve deviated from linear. Widths of the cortical mid-shaft in the medio-lateral (ML) and antero-posterior (AP) directions, moment of inertia (Imin), and the average cortical thickness were determined by μCT in the cortical region described above. Tibial material properties, i.e., stress–strain curves were calculated from the structural properties (i.e., load-displacement curve) in combination with morphological data from μCT as outlined in Turner and Burr (1993). The obtained stress–strain curves reflect the stiffness, strength and failure properties of the bone material itself without the influence of geometry.

2.4. Reference-point indentation

Local bone material properties at the tibial mid-shaft were examined by reference point indentation (RPI) as previously described (Tang et al., 2007) using a BP2 probe assembly apparatus (Biodent Hfc, Active Life Scientific Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The BP2 assembly includes a 90-degree cono-spherical test probe with a ≤ 5 μm radius point and a flat bevel reference probe with ~ 5 mm cannula length and friction < 0.1 N. Each sample was indented 5 times with the initial indentation occurring on the anterior surface of the bone, 6 mm from the tibia-fibula joint along the midline of the bone. Subsequent indentations were taken by moving the sample left, right, forwards or backwards approximately 1 mm in each direction from the initial indentation. The machine was used with the following settings; indentation force 2 N, 2 indentations per sec (Hz), 10 indentation cycles per measurement and touchdown force of 0.1 N. The distance the probe travels into the bone (total indentation distance [TDI]) is a measure of the bone's resistance to fracture; indentation distance increase (IDI) is the indentation distance in the last cycle relative to the first cycle and is correlated to bone tissue roughness; average unloading slope indicates the compressibility of the bone and can be used as a measure of stiffness (Johnson et al., 2014).

2.5. Statistics

All graphs are represented as the mean of all biological replicates. The number of animals (n) is reported on the graph or in the figure legends. All error bars are standard error of the mean. Significant differences were identified by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6.0 software). Statistical significance was considered p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of vitamin D3 dietary intervention on tibial structural properties

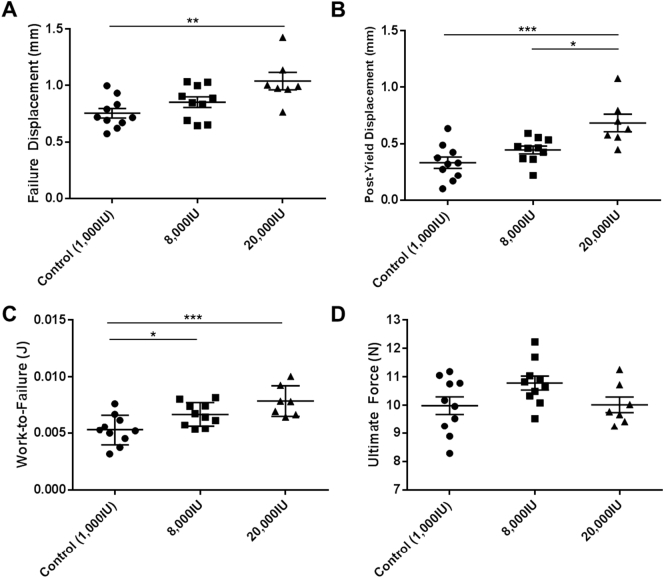

The highest level of dietary vitamin D3 (20,000 IU/kg), but not the 8000 IU/kg dose was associated with a significantly greater (116%) failure displacement when compared to the control group (Fig. 1A). The 20,000 IU/kg diet was also associated with significantly greater post-yield displacement compared to the control (206%), and the 8000 IU/kg (154%) group (Fig. 1B). Tibiae from mice supplied with 20,000 IU/kg dietary vitamin D3 also showed a significantly greater work-to-failure compared control tibiae (153%) (Fig. 1C). Varying dietary vitamin D3 levels had no significant effect on ultimate load, ultimate displacement, stiffness, yield load, yield displacement or tibial failure load compared to the control group (Table 1, Fig. 1D). Furthermore, dietary vitamin D3 levels did not lead to statistically significant differences in tibial length, tibial antero-posterior width or tibial medio-lateral width (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Dietary interventions were shown to have an effect on the structural properties of bone. Dietary intervention with 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 is associated with greater failure displacement, greater post-yield displacement and greater work-to-failure, when compared to the control. (A) Failure displacement, (B) post-yield displacement, (C) work-to-failure and (D) ultimate force were determined by 3-point-bending. For all graphs (Control (1000 IU/kg) n = 10, 8000 IU/kg n = 10, 20,000 IU/kg n = 7), columns represent mean/group and error bars indicate SEM, where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. N = newtons, mm = millimeters and J = joules.

Table 1.

Structural properties.

| Control (1000 IU/kg) | 8000 IU/kg | 20,000 IU/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tibial length (mm) | 18.08 ± 0.2 | 17.58 ± 0.2 | 17.58 ± 0.1 |

| Tibial anterior-posterior width (mm) | 1.209 ± 0.01 | 1.245 ± 0.02 | 1.238 ± 0.02 |

| Tibial medial-lateral width (mm) | 1.061 ± 0.03 | 1.068 ± 0.02 | 1.081 ± 0.04 |

| Ultimate force (N) | 9.99 ± 0.3 | 10.78 ± 0.2 | 10.02 ± 0.3 |

| Ultimate displacement (mm) | 0.561 ± 0.03 | 0.518 ± 0.02 | 0.491 ± 0.03 |

| Stiffness (N/mm) | 27.54 ± 0.9 | 29.73 ± 2.0 | 29.58 ± 1.8 |

| Yield load (N) | 9.48 ± 0.3 | 10.04 ± 0.3 | 9.28 ± 0.2 |

| Yield displacement (mm) | 0.421 ± 0.03 | 0.405 ± 0.03 | 0.354 ± 0.02 |

| Failure force (N) | 8.92 ± 0.4 | 9.26 ± 0.4 | 7.51 ± 0.5a |

| Failure displacement (mm) | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 1.03 ± 0.07bb |

Tibiae from 12 week old female mice that had been on a vitamin D3 dietary intervention for 4 weeks were subjected to three-point-bending and structural properties determined. Values are presented as group mean ± SEM. n = 10 Control, 8000 IU/kg; n = 7 20,000 IU/kg.

p < 0.05 vs 8000 IU.

p < 0.01 vs control.

3.2. Effects of vitamin D3 dietary intervention on tibial material properties

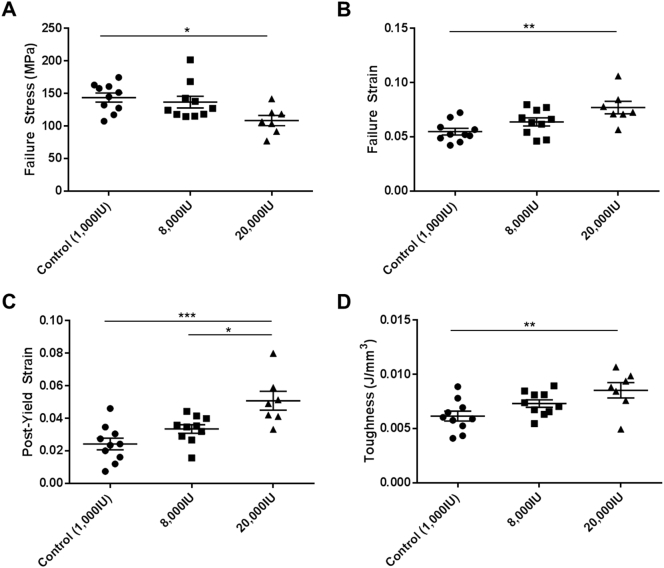

The dietary level of 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 was associated with significantly lower (80%) stress at the failure point, compared to the control (Fig. 2A). This high level of dietary vitamin D3 was also associated with a significantly greater strain at the failure point, compared to control (144%) (Fig. 2B) and a significantly greater post-yield strain compared to both the control (210%), and the 8000 IU/kg group (152%) (Fig. 2C). The 20,000 IU/kg diet of vitamin D3 was associated with a significantly greater (145%) tibial toughness compared to the control (Fig. 2D). In contrast, none of these parameters were altered in mice given the 8000 IU/kg vitamin D3 diet (Fig. 2A–D). No statistically significant differences between groups were observed in maximum stress, strain at maximum stress or elastic modulus related to dietary levels of vitamin D3 (Table 2). Nor was any statistically significant change observed in the stress or strain at the yield point of any samples, when subjected to vitamin D3 dietary intervention (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Dietary interventions with vitamin D3 were shown to have an effect on the material properties of bone. Dietary intervention with 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 is associated with reduced Failure Stress, greater failure strain, post-yield strain, and toughness when compared to the control. (A) Failure stress, (B) failure strain, (C) post-yield strain and (D) toughness were determined by 3-point-bending. For all graphs (Control (1000 IU/kg) n = 10, 8000 IU/kg n = 10, 20,000 IU/kg n = 7), columns represent mean/group and error bars indicate SEM, where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. MPa = megapascals.

Table 2.

Material properties.

| Control (1000 IU/kg) | 8000 IU/kg | 20,000 IU/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic modulus (MPa) | 6224.03 ± 191.0 | 6090.18 ± 511.5 | 5682.51 ± 160.4 |

| Ultimate stress (MPa) | 160.59 ± 5.6 | 159.02 ± 7.8 | 144.89 ± 6.6 |

| Ultimate strain | 0.038 ± 0.04 | 0.039 ± 0.002 | 0.037 ± 0.002 |

| Yield stress (MPa) | 152.51 ± 5.7 | 148.24 ± 8.2 | 134.35 ± 6.4 |

| Yield strain | 0.0306 ± 0.002 | 0.0303 ± 0.002 | 0.0263 ± 0.001 |

| Failure stress (MPa) | 143.72 ± 6.9 | 136.77 ± 8.9 | 108.48 ± 8.0b |

| Failure strain | 0.0548 ± 0.003 | 0.0638 ± 0.004 | 0.0771 ± 0.006bb |

Tibiae from 12 week old female mice that had been on a vitamin D3 dietary intervention for 4 weeks were subjected to three-point-bending and the material properties were determined. Values are presented as group mean ± SEM. n = 10 Control, 8000 IU/kg; n = 7 20,000 IU/kg.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01 vs control.

No dietary intervention was associated with any significant changes in the reference point indentation parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reference-point indentation test results.

| Control (1000 IU/kg) | 8000 IU/kg | 20,000 IU/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st cycle indentation distance (μm) | 32.62 ± 1.4 | 31.19 ± 1.8 | 32.34 ± 1.9 |

| Total indentation distance (μm) | 35.61 ± 1.4 | 34.38 ± 2.1 | 34.25 ± 1.8 |

| Indentation distance increase (μm) | 5.65 ± 0.6 | 5.43 ± 0.5 | 4.41 ± 0.2 |

| Avg unloading (N/μm) | 0.204 ± 0.006 | 0.205 ± 0.011 | 0.235 ± 0.011 |

| Avg loading slope (N/μm) | 0.168 ± 0.007 | 0.163 ± 0.008 | 0.183 ± 0.009 |

| Avg energy dissipated (μJ) | 4.88 ± 0.3 | 5.09 ± 0.4 | 4.27 ± 0.3 |

Tibiae from 12 week old female mice that had been on a vitamin D3 dietary intervention for 4 weeks were subjected to reference point indentation and the results recorded. Values are presented as group mean ± SEM. n = 10 Control, 8000 IU/kg; n = 7 20,000 IU/kg.

3.3. Effects of vitamin D3 dietary intervention on bone morphology

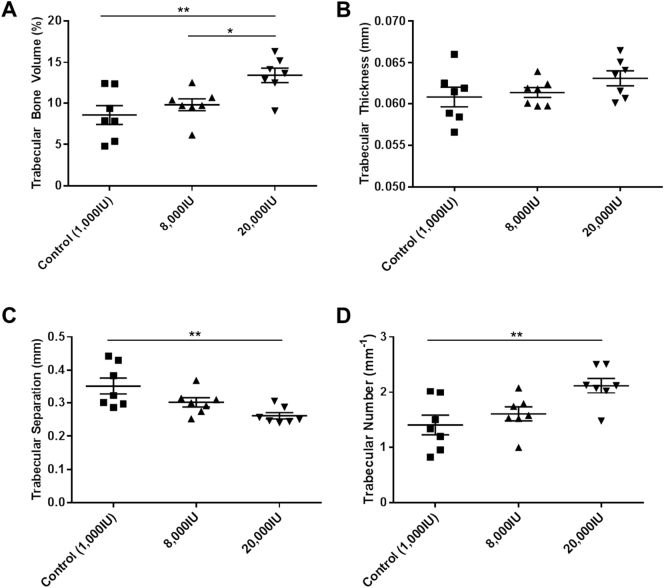

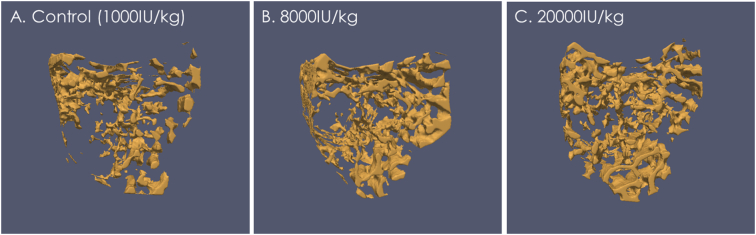

μCT scans of the trabecular secondary spongiosa of the tibiae revealed that a diet containing 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 resulted in a significantly greater trabecular bone volume fraction when compared to the control (146%) and the 8000 IU/kg group (131%) (Fig. 3A). There was no significant change in trabecular thickness due to vitamin D3 supplementation (Fig. 3B). This high dosage of vitamin D3 was also associated with a significantly lower trabecular separation (Fig. 3C) and significantly greater trabecular number (Fig. 3D) compared to the control. None of these parameters were changed in the 8000 IU/kg group. The combination of all changes in all parameters contributing to the overall greater trabecular bone volume fraction can be seen in the models reconstructed from the μCT scans (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Dietary interventions with vitamin D3 were shown to have an effect on the morphology of trabecular bone. Dietary intervention with 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 is associated with greater trabecular bone volume fraction, separation and number when compared to the control. (A) Trabecular Bone Volume fraction, (B) Thickness, (C) Trabecular Separation and (D) Trabecular Number were determined by μCT analysis. For all graphs (Control (1000 IU/kg) n = 10, 8000 IU/kg n = 10, 20,000 IU/kg n = 7), columns represent mean/group and error bars indicate SEM, where *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. mm = millimeters.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed images, using ParaView (version 3.14.1), of the sample from each group; (A) Control (1000 IU/kg), (B) 8000 IU/kg and (C) 20,000 IU/kg, with the trabecular bone volume fraction closest to that of the group mean.

Varying dietary vitamin D3 levels did not lead to statistically significant differences in cortical tissue mineral density, morphology, including cortical area, marrow area, endocortical perimeter, cortical thickness, polar moment of inertia or cross sectional moment of inertia in either the x or y-direction (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bone morphology.

| Control (1000 IU/kg) | 8000 IU/kg | 20,000 IU/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow area (mm2) | 0.140 ± 0.006 | 0.145 ± 0.007 | 0.142 ± 0.005 |

| Cortical area (mm2) | 0.214 ± 0.005 | 0.232 ± 0.007 | 0.232 ± 0.009 |

| Endocortical perimeter (mm) | 0.637 ± 0.009 | 0.652 ± 0.007 | 0.664 ± 0.013 |

| Periosteal perimeter (mm) | 2.811 ± 0.03 | 2.934 ± 0.04 | 2.946 ± 0.06 |

| Tissue mineral density (g·cm3) | 0.96 ± 0.007 | 0.94 ± 0.009 | 0.95 ± 0.009 |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.218 ± 0.004 | 0.229 ± 0.006 | 0.230 ± 0.006 |

| Mean polar moment of inertia (mm4) | 0.1267 ± 0.004 | 0.1395 ± 0.01 | 0.1406 ± 0.01 |

| Cross sectional moment of inertia x (mm4) | 0.0675 ± 0.003 | 0.0784 ± 0.003 | 0.0786 ± 0.006 |

| Cross sectional moment of inertia y (mm4) | 0.0566 ± 0.007 | 0.0611 ± 0.006 | 0.0620 ± 0.004 |

Tibiae from 12 week old female mice that had been on a vitamin D3 dietary intervention for 4 weeks had their length measured with calipers and then were imaged with a μCT scanner from which their bone morphology was determined. Values are presented as group mean ± SEM. n = 10 Control, 8000 IU/kg; n = 7 20,000 IU/kg.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of dietary vitamin D3 on the mechanical properties and morphology of murine tibiae. We found that provision of 20,000 IU/kg to 8 week old female mice for 4 weeks was associated with greater bone strength, greater structural and material ductility, and greater toughness. This level of dietary vitamin D3 was also associated with significantly higher trabecular bone volume fraction but no detectable change in cortical structure.

The greater trabecular bone mass in mice administered the highest level of vitamin D3 is consistent with previous studies (Lee et al., 2010), where vitamin D interventions resulted in greater effects on trabecular but not cortical bone. Lee et al. (2010) demonstrated by μCT that increasing dietary vitamin D3 levels administered to 10 week old rats (from approximately 100 IU/kg to 600 IU/kg), led to greater femoral and vertebral trabecular bone mass with the higher doses. Again, consistent with our observations, they did not observe any change in cortical bone dimensions; indicating that vitamin D dietary interventions predominantly modify trabecular rather than cortical bone structure. They observed a significant effect at a lower Vitamin D3 dosage compared to our study, likely due to the use of a vitamin D3 deficient rat model and a significantly longer intervention period (20 weeks compared to 4 weeks).

Although we observed no significant change in cortical dimensions, the mechanical properties of cortical bone were greatly altered by the highest level of vitamin D3 supplementation, indicating a likely change in bone composition. The greater post-yield displacement, post-yield strain, failure displacement and failure strain in mice on the 20,000 IU/kg dietary intervention indicated that both the structural and material ductility were greater than in mice supplied with the control diet. Furthermore, dietary levels of 20,000 IU/kg vitamin D3 resulted in the need for a higher energy requirement for bone fracture, both over the whole bone structure (work-to-failure) and the material (toughness). Previous studies reported that treatment of ovariectomised rats with 0.5 μg/kg/day 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25OHD3) significantly increased toughness compared to both the ovariectomized control and non-ovariectomized control (Aerssens et al., 1994, Zimmermann et al., 2015). While our study did not measure 1,25OHD3 levels, previous reports (Aerssens et al., 1994, Zimmermann et al., 2015) suggest that it is likely that the greater toughness observed with the 20,000 IU/kg dietary intervention is due to an increased level of circulating 1,25OHD3, resulting in a more ductile and tougher bone; however this will need future confirmation.

The material properties of bone, specifically the ease with which collagen fibrils slide over each other can increase toughness since increased ability to slide will allow the bone to deform and absorb any applied loads (Zimmermann et al., 2015). Through reference point micro-indentation (RPI) we examined the material properties of the bone but observed no differences between any of our dietary intervention groups. Paschalis et al., (2016) (Paschalis et al., 2016) reported that vitamin D and calcium supplementation for a three year period in postmenopausal osteoporosis significantly altered bone mineral and organic matrix quality. The lack of an obvious change using RPI may be due to insufficient precision of this method; this could be overcome through the use of a nano- or pico-indentor. Additionally, a limitation of RPI is that it only examines the material properties on the periosteal surface. It is possible that our observed changes in material properties may be due to the incorporation of mineral at a deeper level or on the endocortical surface. Future studies using Raman microspectroscopy (as used by Paschalis et al.) may permit these questions to be addressed.

The greater ductility and toughness observed in the bones of our growing mice suggest that dietary supplementation with vitamin D3 may be a suitable method to increase peak bone mass during adolescence to prevent development of osteoporosis later in life. This strategy of decreasing fracture risk in the elderly by optimising bone health during bone development was previously suggested by Rizzoli et al. (2010), and was supported by a positive correlation between childhood bone health and bone health in adulthood. Further evidence to support this strategy comes from a number of intervention studies in adolescents which have reported significant increases in bone mineral content (BMC) and bone mineral density (BMD) with vitamin D3 supplementation. Viljakainen et al. (2006) reported that daily tablets of 5 and 10 μg vitamin D3 supplementation (approximately 200–400 IU/d) for 1 year in adolescent girls resulted in significant increases in femoral bone BMC. Likewise El-Hajj Fuleihan et al. (2006) treated adolescent girls with 14,000 IU (equivalent to 2000 IU/d) for 1 year and observed an increase in hip BMC. Finally, Du et al. (2004) observed in 10–12 year old girls that daily consumption of milk fortified with 8 μg vitamin D3 (320 IU/d) for a period of 2 years resulted in size adjusted increases in BMC and BMD. Our experiments were conducted on 8-week-old female mice, which are post-puberty, but still growing, and in these mice we saw an increase in bone strength through a 20,000 IU/kg dietary supplementation, suggesting that clinical dietary vitamin D3 supplementation may be an avenue to increase bone health in young, growing bones, and could result in decreased fracture risk in adulthood. However, this requires additional research.

In conclusion, we observed that high levels of dietary vitamin D3 in adult mice resulted in greater tibial ductility, toughness and greater trabecular bone volume fraction. Our results suggest that high levels of dietary vitamin D3 may be suitable for achieving a higher peak bone mass in adulthood and thereby preventing osteoporosis.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

(A) A photograph of the actual set up of the Bose Biodynamic 5500 Test Instrument. (B) A schematic representation of the 3-point bending apparatus where, F = applied load (in z-direction), L = distance (in x-direction) between supports, d = displacement/deformation of the bone (in z-direction).

References

- Aerssens J., Van Audekercke R., Talalaj M., Van Vlasselaer P., Bramm E., Geusens P., Dequeker J. Effect of 1 alpha-vitamin D3 on bone strength and composition in growing rats with and without corticosteroid treatment. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1994;55(6):443–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00298558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R., Molgaard C., Skovgaard L.T., Brot C., Cashman K.D., Jakobsen J., Lamberg-Allardt C., Ovesen L. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on bone and vitamin D status among Pakistani immigrants in Denmark: a randomised double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;100:197–207. doi: 10.1017/S000711450789430X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P.H., Atkins G.J., Turner A.G., Kogawa M., Findlay D.M., Morris H.A. Vitamin D metabolism within bone cells: effects on bone structure and strength. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011;347(1–2):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Willett W.C., Wong J.B., Giovannucci E., Dietrich T., Dawson-Hughes B. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293(18):2257–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.18.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Tylavsky F., Kroger H., Karkkainen M., Lyytikainen A., Koistinen A., Mahonen A., Alen M., Halleen J., Vaananen K., Lamberg-Allardt C. Association of low 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with elevated parathyroid hormone concentrations and low cortical bone density in early pubertal and prepubertal Finnish girls. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:485–492. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Hughes B., Dallal G.E., Krall E.A., Harris S., Sokoll L.J., Falconer G. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on wintertime and overall bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991;115:505–512. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Zhu K., Trube A., Zhang Q., Ma G., Hu X., Fraser D.R., Greenfield H. School-milk intervention trial enhances growth and bone mineral accretion in Chinese girls aged 10–12 years in Beijing. Br. J. Nutr. 2004;92:159–168. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hajj Fuleihan G., Nabulsi M., Tamim H., Maalouf J., Salamoun M., Khalife H., Choucair M., Arabi A., Vieth R. Effect of vitamin D replacement on musculoskeletal parameters in school children: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:405–412. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares J.E., Choucair M., Nabulsi M., Salamoun M., Shahine C.H., Fuleihan GEl H. Effect of gender, puberty, and vitamin D status on biochemical markers of bone remodeling. Bone. 2003;33:242–247. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen K.J., Silva M.J., Vashishth D., Guo X.E., van der Meulen M.C. 2015. Establishing Biomechanical Mechanisms in Mouse Models: Practical Guidelines for Systematically Evaluating Phenotypic Changes in the Diaphyses of Long Bones; pp. 1523–4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.W., Brennan H.J., Vrahnas C., Poulton I.J., McGregor N.E., Standal T., Walker E.C., Koh T.T., Nguyen H., Walsh C.C., Forwood M.R., Martin T.J., Sims N.A. The primary function of gp130 signaling in osteoblasts is to maintain bone formation and strength, rather than promote osteoclast formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29(6):1492–1505. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.M., Anderson P.H., Sawyer R.K., Moore A.J., Forwood M.R., Steck R., Morris H.A., O'Loughlin P.D. Discordant effects of vitamin D deficiency in trabecular and cortical bone architecture and strength in growing rodents. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;121(1–2):284–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen-Veromaa M.K., Mottonen T.T., Nuotio I.O., Irjala K.M., Leino A.E., Viikari J.S. Vitamin D and attainment of peak bone mass among peripubertal Finnish girls: a 3-y prospective study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;76:1446–1453. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips P. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocr. Rev. 2001;22:477–501. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaëlsson K., Melhus H., Bellocco R., Wolk A. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake in relation to osteoporotic fracture risk. Bone. 2003;32(6):694–703. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Riordan J.L., Bijvoet O.L. Rickets before the discovery of vitamin D. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:478. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outila T.A., Karkkainen M.U., Lamberg-Allardt C.J. Vitamin D status affects serum parathyroid hormone concentrations during winter in female adolescents: associations with forearm bone mineral density. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001;74:206–210. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschalis E.P., Gamsjaeger S., Hassler N., Fahrleitner-Pammer A., Dobnig H., Stepan J.J., Pavo I., Eriksen E.F., Klaushofer K. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation for three years in postmenopausal osteoporosis significantly alters bone mineral and organic matrix quality. Bone. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar K. Vitamin D, cod-liver oil, sunlight, and rickets: a historical perspective. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e132–e135. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar K., Thomas S.B. Reemerging nutritional rickets: a historical perspective. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005;159:335–341. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid I.R., Bolland M.J., Grey A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;383(9912):146–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli R., Bianchi M.L., Garabedian M., McKay H.A., Moreno L.A. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone. 2010;46(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K.M., Stuart A.L., Williamson E.J., Simpson J.A., Kotowicz M.A., Young D., Nicholson G.C. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1815–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H., Anderson F., Raphael H., Maslin P., Crozier S., Cooper C. Effect of annual intramuscular vitamin D on fracture risk in elderly men and women–a population-based, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1852–1857. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B.M., Eslick G.D., Nowson C., Smith C., Bensoussan A. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370(9588):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C.H., Burr D.B. Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: a tutorial. Bone. 1993;14(4):595–608. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90081-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljakainen H.T., Natri A.M., Karkkainen M., Huttunen M.M., Palssa A., Jakobsen J., Cashman K.D., Molgaard C., Lamberg-Allardt C. A positive dose-response effect of vitamin D supplementation on site-specific bone mineral augmentation in adolescent girls: a double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled 1-year intervention. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:836–844. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C.L., Greer F.R. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142–1152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C.L., Hulsey T.C., Fanning D., Ebeling M., Hollis B.W. High-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in a cohort of breastfeeding mothers and their infants: a 6-month follow-up pilot study. Breastfeed. Med. 2006;1:59–70. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzenberg T.M., Powell S., Shaw K.A., Jones G. Vitamin D supplementation for improving bone mineral density in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006944.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzenberg T., Powell S., Shaw K.A., Jones G. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on bone density in healthy children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann E.A., Busse B., Ritchie R.O. The fracture mechanics of human bone: influence of disease and treatment. Bonekey Rep. 2015;4:743. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2015.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) A photograph of the actual set up of the Bose Biodynamic 5500 Test Instrument. (B) A schematic representation of the 3-point bending apparatus where, F = applied load (in z-direction), L = distance (in x-direction) between supports, d = displacement/deformation of the bone (in z-direction).