Abstract

It is generally accepted that bone and muscle possess the capacity to act in an autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine manner, with a growing body of evidence that suggests muscle can secrete muscle specific cytokines or “myokines”, which influence bone metabolism. However, there has been little investigation into the identity of bone specific cytokines that modulate skeletal muscle differentiation and function. This study aimed to elucidate the influence of osteocytes on muscle progenitor cells in vitro and to identify potential bone specific cytokines or “osteokines”. We treated C2C12 myoblasts with media collected from differentiated osteocytes (Ocy454 cells) grown in 3D, either under static or fluid flow culture conditions (2 dynes/cm2). C2C12 differentiation was significantly inhibited with a 75% reduction in the number of myofibers formed. mRNA analysis revealed a significant reduction in the expression of myogenic regulatory genes. Cytokine array analysis on the conditioned media demonstrated that osteocytes produce a significant number of cytokines “osteokines” capable of inhibiting myogenesis. Furthermore, we demonstrated that when osteocytes are mechanically activated they induce a greater inhibitory effect on myogenesis compared to a static state. Lastly, we identified the downregulation of numerous cytokines, including Il-6, Il-13, Il-1β, MIP-1α, and Cxcl9, involved in myogenesis, which may lead to future investigation of the role “osteokines” play in musculoskeletal health and pathology.

Keywords: Osteocyte, Skeletal muscle, Ocy454, C2C12, Osteokine, Myogenic differentiation

Highlights

-

•

Osteocytes secrete a diverse secretome.

-

•

Osteocyte secreted products inhibit skeletal muscle cell differentiation.

-

•

Fluid flow activation enhances inhibitory action of osteocytes on skeletal muscle

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have demonstrated a close functional and developmental relationship exists between bone and muscle mass (Frost and Schonau, 2000, Judex and Rubin, 2010, DiGirolamo et al., 2013). While the long standing view is that this relationship is primarily mechanical in nature, recent work has demonstrated an endocrine relationship. Indeed, many muscle specific cytokines, collectively coined “myokines”, produced by skeletal muscle can influence bone cells development and function (Hamrick et al., 2007, Colaianni et al., 2014, Juffer et al., 2014, Johnson et al., 2014). Although there is a substantive body of evidence suggesting that muscle can influence bone, the ability of bone to influence muscle remains unclear.

Osteocytes are connected to the vascular system and they secrete molecules known to influence distal tissues and organs (Sato et al., 2013). Indeed, osteocyte secreted FGF23 has shown to play a vital function in phosphate metabolism in the kidney (Quarles, 2012) and recently, sclerostin, an osteocyte-specific secreted factor, has been shown to influence not only bone, but also adipose tissue (Fulzele et al., 2016). Interestingly, it has also been demonstrated that deletion of gap junction protein connexin 43 in osteoblasts and osteocytes leads to impaired muscle formation in vivo (Shen et al., 2015). Collectively, these findings suggest that bone specific osteokines may pass outside the bone matrix and play a role in muscle formation, kidney function and fat metabolism. To date limited work has assessed the potential for osteocytes to modulate skeletal muscle differentiation and function. Mo et al. (2012) identified that conditioned media from MLO-Y4 osteocyte like cells induced acceleration of myogenesis of C2C12 myoblasts. The same group reported enhanced myogenic differentiation following Wnt3a treatment (a key factor released by osteocytes) suggesting that Wnt3a plays a role in the regulation of myoblast differentiation (Romero-Suarez and Brotto, 2012).

Given that bone has the potential to secrete factors that influence muscle and that limited work has been conducted in this area, this study aimed to elucidate osteocytes influence on muscle. We used C2C12 myoblast cell line, a well-established and well-accepted cell model for myogenic differentiation (Yaffe and Saxel, 1977, Burattini et al., 2004). In addition, in contrast to previous studies, we investigated whether conditioned media from a novel 3-dimensional (3D) osteocyte cell culture system, under both static and fluid flow conditions, could modulate skeletal muscle cell differentiation. Here we report that osteocyte secrete factors capable of inhibiting myogenesis, with a specific affinity for late differentiation. Furthermore we have also identified numerous signalling cytokines present in the osteocyte secretome, which may begin to explain how osteocytes inhibit myogenesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Cat. No. 17-512F), Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium High Glucose (DMEM, Cat. No. 12-604F), Alpha modification of Eagle's medium (αMEM, Cat. No. 12-169F), and Penicillin-Streptomycin Mixture (Cat. No. 17-602E) were obtained from Lonza (Mount Waverly, Australia). Fetal Bovine Serum and Horse Serum were obtained from Bovogen (Keilor East, Australia). Trizol Reagent and TrypLE Express were purchased from Life Technologies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). IScript™ Reverse Transcription Super mix for RT-qPCR and iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Super mix were purchased from Bio-Rad (Gladesville, Australia). The Proteome Profiler Mouse Cytokine Array Kit, Panel A was purchased from R &D Systems (Abingdon, UK). qRT-PCR primers purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Baulkham Hills, Australia).

2.2. Cell cultures

Ocy454 murine osteocytic cells were grown in proliferation media containing high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) as previously described (Spatz et al., 2015). Briefly, for three dimensional cell cultures, 1.6 × 106 Ocy454 cells were plated on a 200 μm polystyrene Alvetex (Reinnervate) well insert scaffolds. Cells were allowed to grow at the permissive temperature (33 °C) for 2 days prior to transferring to (37 °C) for differentiation. For the generation of “static” osteocyte conditioned media (CM), cells were differentiated for 14 days and media collected on day 15 following a media change on day 14.

For collection of “flow activated” conditioned media (Flow-CM) cells were differentiated for 14 days prior to transferring to the Reinnervate Perfusion Plate. The perfusion plates were attached to a Masterflex Peristaltic Pump (#7520-57) with a Masterflex Standard Pump Head (#7014-20) and were exposed to 2 dynes/cm2 (0.2 Pa, frequency of 1.2 Hz with a shear rate of 278γ) for 24 h prior to medium collection. Prior to use the produced CM was centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove cells and cellular debris.

C2C12 murine multi-potent cells were cultured in Proliferation media; DMEM/High Glucose + 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) & 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin and were maintained at 40–70% cell density. Under these conditions, myoblasts proliferate, but do not differentiate into myofibers.

For differentiation studies, undifferentiated C2C12 cells were plated in a 6 well plate at a density of 4.5 × 105 cells per well to a final volume of 1 ml and allowed to settle for 24 h. Undifferentiated C2C12 cells were then cultured in “static” or “flow activated” osteocyte conditioned media or relevant unconditioned media “vehicle”. The following concentrations of osteocyte CM were tested, 10%, 50%, and 100% comprising the appropriate ratio of conditioned and differentiation media. Additionally, for all assays, the appropriate unconditioned media (vehicle, 10% FBS) was used as a negative control (Supplementary Fig. 2). RNA was collected after 1, 3, or 6 days following the commencement of differentiation with a media change every 2 days.

2.3. Real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from C2C12 cells lysed in Trizol (Invitrogen, Australia), and cDNA was prepared using random hexamers (Promega, Australia) and Superscript III (Invitrogen, Australia) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the StratageneMX3000P (Agilent Technologies) as previously described (Gooi et al., 2010, Gooi et al., 2014). Primers designed using Primer-BLAST are listed in Table 1. Primer sets were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coraville, IA). Post-run samples were analysed using Stratagene MxPro software and are expressed as linear ΔCT values normalized to Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1). The level of housekeeping gene did not vary significantly between treatment groups.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for qPCR analysis.

| Primer | Forward sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reverse sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| MyoD1 | TACGACACCGCCTACTACAGTG | GTGGTGCATCTGCCAAAAG |

| Mrf4 | TGCTAAGGAAGGAGGAGCAA | CCTGCTGGGTGAAGAATGTT |

| MyH1 | CTTCAACCACCACATGTTCG | AGGTTTGGGCTTTTGGAAGT |

| Myf5 | CTGTCTGGTCCCGAAAGAAC | TGGAGAGAGGGAAGCTGTGT |

| Myogenin | GCAATGCACTGGAGTTCG | ACGATGGACGTAAGGGAGTG |

| HPRT1 | TGATTAGCGATGATGAACCAG | AGAGGGCCACAATGTGATG |

2.4. Myofiber number and length

The number and length of myofibers were quantified using light microscopy. Briefly, C2C12 cells were plated in a 6 well plate at a density of 4.5 × 105 cells per well to a final volume of 1 ml. Cells were then treated with different osteocyte CM. At 1, 3 and 6 days images were taken on an Olympus FV1000 live cell imager with an IX81 microscope (Olympus, Pennsylvania, USA) under 10 × magnification. Images were obtained at 16 bit and analysed using ImageJ software (NIH).

2.5. Cytokine array

Osteocyte CM from Ocy454 grown for 14 days (static or fluid flow activated) (n = 3 biological replicates) was analysed for cytokine presence using mouse cytokine array panel A (R&D Systems), as per the manufacturer's instructions. 1 ml of each medium sample was thawed on ice prior to kit incubation, wash, and detection.

Quantification of cytokine array spot density for the Mouse Cytokine Array Panel A was performed using NIH ImageJ and normalized to positive controls in each membrane as per manufacturer instructions.

2.6. Statistics

All experiments were performed a minimum of 3 times, using independent preparations of conditioned medium (n = 3 biological replicates). Data were analysed for statistical significance by Student's unpaired t-test or ANOVA as indicated in figure legends followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test, using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad). For all graphs, bars represent the mean/group and error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Osteocyte conditioned media inhibits myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts

To investigate the effect of secreted factor(s) from Ocy454 cells, C2C12 were incubated with 100% osteocyte CM (static and flow activated) from 3D cell cultures. This percent CM was determined by dose response experiments up to 100% CM (Supplementary Fig. 1). 10% CM had no significant effect, apart from MyoD, on myogenic gene expression. 50% and 100% CM had a more robust response and as no significant differences were observed between 50% and 100% CM groups, all subsequent experiments were performed with 100% CM compared to C2C12 cultured in fresh unconditioned Ocy454 media (vehicle). Cell viability was no affected by the increasing concentrations of CM (data not shown).

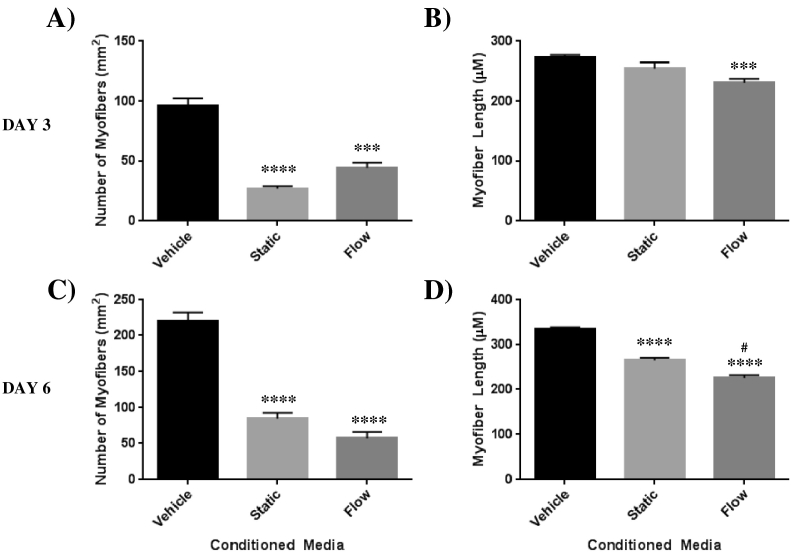

Treatment with static CM had no effect on myofiber number or length following on day 1 (D1) of treatment (data not shown). However, by day 3 (D3) of differentiation there was a significant reduction in the number of myofibers formed compared to vehicle (95.67 ± 6.7 vs 27.33 ± 2.0 myofibers/well) which was also observed on day 6 (D6) of differentiation (220.3 ± 12.1 vs 84.67 ± 8.4 myofibers/well) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Myofiber length, unaffected on D1 and D3, was significantly reduced on D6 following treatment with static osteocyte CM compared with vehicle (333.8 ± 4.3 μm vs 265.5 ± 5.6 μm, Fig. 2D).

Fig. 1.

Effect of treatment with conditioned media, collected from differentiated Ocy454 cells (static and flow activated (2 dynes/cm2 for 24 h)), on C2C12 differentiation. Representative images of C2C12 vehicle (unconditioned media (10%FBS)) treated cells at A) Day 1, D) Day 3, and G) Day 6. C2C12 cells treated with Static CM B) Day 1, E) Day 3, and H) Day 6. C2C12 cells treated with fluid flow activated CM C) Day 1, F) Day 3, and I) Day 6. N = 3. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

Fig. 2.

Effect of treatment with conditioned media, collected from differentiated Ocy454 cells (static and flow activated (2 dynes/cm2 for 24 h)), on C2C12 myofiber number and length. A) C2C12 myofiber number following treatment with OCY454 CM for 3 days and C) 6 days. B) C2C12 myofiber length following treatment with OCY454 CM for 3 days and D) 6 days. Data is Mean ± SEM. N = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs Vehicle. #p < 0.05 v Static. Data were analysed for statistical significance by ANOVA.

Treatment with Flow-CM also resulted in a significant reduction in the number of myofibers formed at D3 compared to vehicle (95.67 ± 6.7 vs 44.33 ± 4.2 myofibers/well) and D6 (220.3 ± 12.1 vs 57.00 ± 9.0 myofibers/well) Fig. 1, Fig. 2A & C). Myofiber length was unaffected on D1 of treatment, however in contrast to treatment with static CM, was significantly reduced on D3 (272.6 8 ± 4.7 μm vs 230.6 ± 7.2 μm, Fig. 2B) and also D6 of treatment with Flow- CM compared with vehicle (333.8 ± 4.3 μm vs 225.9 ± 6.2 μm, Fig. 2D).

3.2. Change of gene expression profile after osteocyte conditioned media treatment

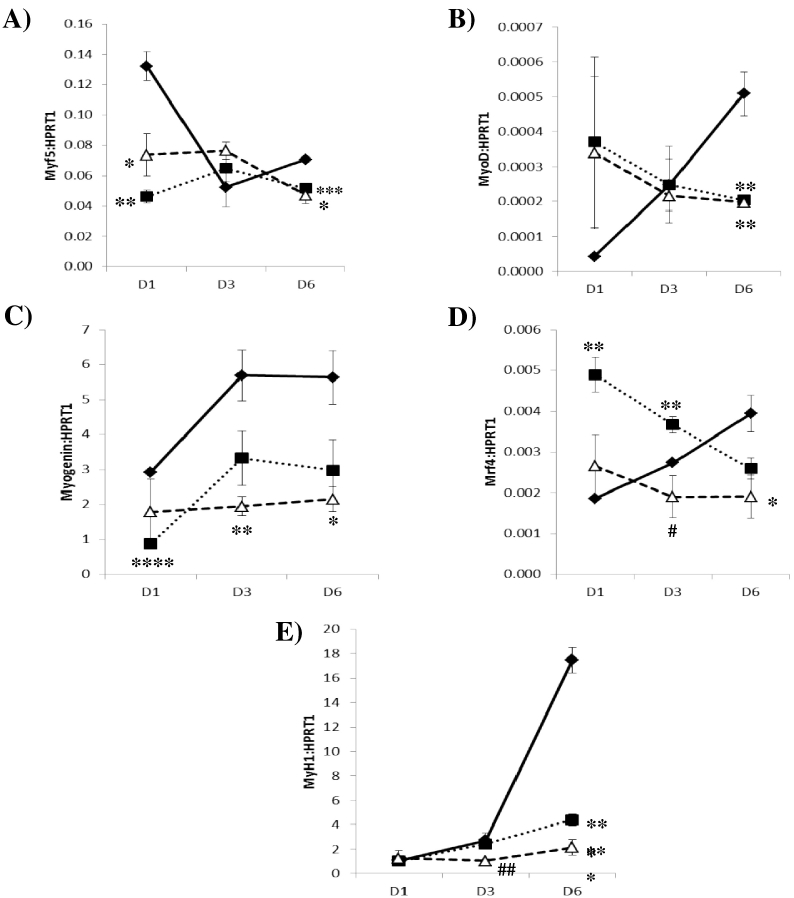

To explore the mechanism behind the effects of osteocyte CM, the expression of key myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) was measured. MRFs are the master regulators of skeletal myogenesis controlling the commitment of myogenic precursor cells and the terminal differentiation of myoblasts. Classically, Myf5 and MyoD are considered to be the early or commitment MRFs, while myogenin and MRF4 are considered to be differentiation MRFs. Furthermore, MyH1 a marker of the contractile apparatus that serves as a late marker of myogenic differentiation was also measured.

Treatment with static CM resulted in a significant reduction in Myf5 mRNA expression levels at D1 (65%, p = 0.012) and D6 (27%, p = 0.0009) of differentiation compared to vehicle. These reduction were also observed with treatment with Flow-CM at both D1 (44%, p = 0.0254) and D6 (33%, p = 0.0159) compared to vehicle (Fig. 3A). Expression of MyoD was also observed to be significantly reduced at D6 with static (60%, p = 0.0088) and Flow-CM (61%, p = 0.0159) compared to vehicle (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of treatment with conditioned media, collected from differentiated Ocy454 cells (static and flow activated (2 dynes/cm2 for 24 h)), on C2C12 myoblasts gene expression collected 1, 3, and 6 days after treatment. A) Myf5, B) Myod, C) Mrf4, D) Myogenin, and E) Myh1 gene expression. Static (■), Flow-CM ( ) and unconditioned media (10%FBS) (vehicle,

) and unconditioned media (10%FBS) (vehicle,  ). Data are mean levels of the gene of interest relative to HPRT1 ± SEM (N = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs Vehicle. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, vs static conditioned media. Data were analysed for statistical significance by ANOVA.

). Data are mean levels of the gene of interest relative to HPRT1 ± SEM (N = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs Vehicle. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, vs static conditioned media. Data were analysed for statistical significance by ANOVA.

Treatment with static osteocyte CM resulted in a significant decrease (70%, p < 0.0001) in Myogenin gene expression following one day of treatment compared to vehicle. This reduction was also seen at D1 following treatment with Flow-CM (66%, p = 0.009) and was also significantly reduced on D6 of treatment (62%, p = 0.0149) compared vehicle (Fig. 3C). Expression of Mrf4 was increased following treatment with static CM at D1 (263%, p = 0.002) and D3 (134%, p = 0.01) of differentiation compared to vehicle. In contrast, treatment with Flow-CM resulted in a significant reduction in Mrf4 expression at D6 (52%, p = 0.0437) compared to vehicle (Fig. 3D).

Myh1 expression was significantly reduced (75%, p = 0.004) at D6 following treatment with static CM (p = 0.004) compared to vehicle. This reduction was also observed at D6 in cultures treated with Flow-CM (88%, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3E).

3.3. Comparison between the effects of static and flow activated conditioned media on C2C12 differentiation

Treatment of C2C12 myoblasts with static and flow conditioned media resulted in an overall inhibition of skeletal muscle differentiation. However, activation of osteocytes, via pulsatile fluid flow, resulted in a profile of greater inhibition of skeletal muscle differentiation. Flow-CM resulted in the abolition of the increase in Mrf4 seen after D1 and D3 of treatment with static CM, reaching significance at D3 (p = 0.0326, Fig. 3D). Furthermore, treatment with flow activated CM resulted in a significant reduction of MyH1 gene expression at D3 (p = 0.0011) compared to treatment with static osteocyte CM (Fig. 3E). Finally, myofiber length was significantly reduced following 6 days of treatment (265.5 ± 5.6 μm vs 225.9 ± 6.2 μm, Fig. 2D).

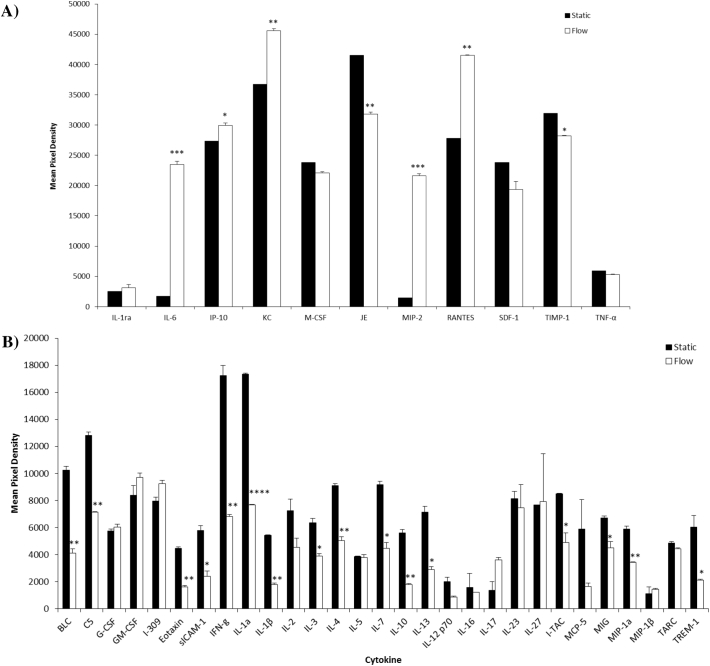

3.4. Identification of distinct cytokine profiles in static and flow activated conditioned media

In order to identify potential factor(s) present in both static and flow CM, and to determine if each CM had a distinct secretory profile, a cytokine array was performed on CM collected from both experimental conditions. When overlaid with the cytokine array coordinates, the array revealed that in comparison to unconditioned media the chemokines MCP-1 and CXCL1 were the most abundant proteins in the static CM, followed by TIMP-1, CCL5, CXCL10, and M-CSF (Fig. 4A). Further exposure of the film (3 min) revealed static osteocytes released an abundant variety of cytokines (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the effects of flow activation (2 dynes/cm2 for 24 h) on cytokine production versus static osteocyte CM (A) 30 s exposure (B) 3 min exposure. Data is Mean ± SEM. N = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs Static CM.

Cytokine analysis of flow-CM revealed that CXCL1 and CCL5 were the most abundant chemokines compared to unconditioned media followed by MCP-1, CXCL1, TIMP-1, and IL-6 (Fig. 4A). As seen with the static CM, further exposure of the film revealed an abundant variety of cytokines produced by flow activated osteocytes (Fig. 4B).

Of particular interest was that we observed distinct differences between the cytokine profile of flow-CM compared to static-CM (Table 2). We observed significant increases in the production of IL-6 (13.42 fold, p = 0.0007), CXCL2 (14.57 fold, p = 0.0003), IP-10 (p = 0.0286), KC (p = 0.0018), and RANTES (p = 0.0025) in flow-CM compared to static-CM (Fig. 4A, Table 2). We also observed significant decreases in BLC (p = 0.0045), C5a (p = 0.0019), Eotaxin (p = 0.0023), siCAM-1 (p = 0.0224), IFN-γ (p = 0.0056), IL-1α (p < 0.0001), IL-1β (p = 0.0017), IL-3 (p = 0.019), Il-4 (p = 0.0056), IL-7 (p = 0.0105), IL-10 (p = 0.0046), IL-13 (p = 0.0141), MIG (p = 0.0437), MIP-1a (p = 0.0063), TIMP-1 (p = 0.0184) and TREM-1 (p = 0.0464) compared to static-CM (Fig. 4A & B, Table 2). Altogether these data demonstrated that osteocytes secrete numerous cytokines capable of directly affect muscle cells differentiation and functions.

Table 2.

Differential cytokine and chemokine expression in flow activated osteocyte conditioned media compared to static conditioned media.

| Cytokine | Alternate name | Change | p-Value | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLC | CXCL13/BCA-1 | 0.0045 | − 2.49 | |

| C5/C5a | Complement Component 5a | 0.0019 | − 1.79 | |

| G-CSF | – | 0.3707 | 1.04 | |

| GM-CSF | – | 0.2424 | 1.15 | |

| I-309 | CCL1/TCA-3 | 0.0696 | 1.16 | |

| Eotaxin | CCL11 | 0.0023 | − 2.75 | |

| sICAM-1 | CD54 | 0.0224 | − 2.41 | |

| IFN-γ | – | 0.0056 | − 2.53 | |

| IL-1α | IL-1F1 | < 0.0001 | − 2.26 | |

| IL-1β | IL-1F2 | 0.0017 | − 3.05 | |

| IL-1ra | IL-1F3 | 0.3757 | 1.23 | |

| IL-2 | – | 0.1331 | − 1.59 | |

| IL-3 | – | 0.019 | − 1.63 | |

| IL-4 | – | 0.0056 | − 1.80 | |

| IL-5 | – | 0.847 | − 1.01 | |

| IL-6 | – | 0.0007 | 13.42 | |

| IL-7 | – | 0.0105 | − 2.05 | |

| IL-10 | – | 0.0046 | − 3.11 | |

| IL-13 | – | 0.0141 | − 2.48 | |

| IL-12 p70 | – | 0.0803 | − 2.31 | |

| IL-16 | – | 0.7505 | − 1.31 | |

| IL-17 | – | 0.0796 | 2.62 | |

| IL-23 | – | 0.7397 | − 1.09 | |

| IL-27 | – | 0.9475 | − 0.03 | |

| IP-10 | CXCL10/CRG-2 | 0.0286 | − 0.10 | |

| I-TAC | CXCL11 | 0.0369 | − 1.73 | |

| KC | CXCL1 | 0.0018 | 1.24 | |

| M-CSF | – | 0.2288 | − 1.07 | |

| JE | CCL2/MCP-1 | 0.0032 | − 1.29 | |

| MCP-5 | CCL12 | 0.1902 | − 3.55 | |

| MIG | CXCL9 | 0.0437 | − 1.49 | |

| MIP-1a | CCL3 | 0.0063 | − 1.728 | |

| MIP-1β | CCL4 | 0.5908 | 1.28 | |

| MIP-2 | CXCL2 | 0.0003 | 14.57 | |

| RANTES | CCL5 | 0.0025 | 1.49 | |

| SDF-1 | CXCL12 | 0.1024 | − 1.23 | |

| TARC | CCL17 | 0.0679 | − 1.09 | |

| TIMP-1 | – | 0.0184 | − 1.13 | |

| TNF-α | – | 0.3625 | − 1.11 | |

| TREM-1 | – | 0.0464 | − 2.85 |

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effect of the secretome of static and flow activated osteocytes on skeletal muscle differentiation. We demonstrated that treatment with osteocyte conditioned media significantly inhibited C2C12 myogenic differentiation. The observed reductions in the expression of myogenic regulatory factors, across numerous time points, suggested that osteocyte conditioned media contains signalling molecules which inhibit myoblasts ability to differentiate into myofibers. This was confirmed with a significant reduction in the number of myofibers formed. Our findings were in stark contrast to work conducted by Mo et al. (Mo et al., 2012), who reported that conditioned media collected from the MLO-Y4 osteocyte cell line promoted myogenesis. Their study demonstrated increased levels of Myogenin and Myod following MLO-Y4 treatment. These contrasting results could derive from a number of experimental differences. Our study used the OCY454 cell line in a 3D cell culture system, which in contrast the MLO-Y4 cell line grown in 2D by Mo et al., has been shown to be a more faithful recapitulation of the characteristic osteocyte gene expression profile of osteocytes in vivo which in contrast to MLO-Y4 cells have high mRNA levels of Sost and Dmp1 and no osteoblastic contamination as demonstrated by the lack of keratocan (osteoblast marker) expression (Spatz et al., 2015).

Upon investigation into the osteocyte secretome, we identified a large number of common cytokines which have previously been shown to have roles in myogenic differentiation. For example, MIP-1a, significantly down regulated in our study, has been shown to greatly increase myoblast proliferative response (Yahiaoui et al., 2008). Collectively, these findings suggest that the static osteocyte secretome can signal to myoblasts via numerous signalling molecules, which has an overall inhibitory effect of the ability of myoblasts to differentiate into myofibers.

As osteocytes are a mechanosensitive cell our next aim was to investigate whether mechanically stimulated osteocytes had a different effect on C2C12 differentiation compared to static osteocytes. The precise level of sheer stress generated by physiological loading is a subject of ongoing research. Theoretical models have predicted sheer stresses of 0.8–3 Pa (Burger and Klein-Nulend, 1999, Weinbaum et al., 1994). In this study, osteocytes were exposed to 0.2 Pa, significantly lower than previously predicted. We have previously observed classical loading responses, such as the downregulation of Sost mRNA, using this level of force (Spatz et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is likely that the actual amount of force reaching the osteocyte cell body is lower still due to the inhomogeneity of the scaffold. This suggests that osteocytes may be even more sensitive to mechanical loading than previously predicted.

Myoblasts cultured in flow activated osteocyte conditioned media expressed significantly less Mrf4 and Myh1 compared to static osteocyte conditioned media. Similarly, flow activation of osteocytes arrested the increase at D1 and D3 in Mrf4 mRNA expression that was observed in static osteocytes. Collectively, these findings suggest that osteocyte secretome under flow has a greater inhibitory capacity on C2C12 differentiation.

Flow activated osteocyte conditioned media displayed a vastly different secretory profile from static osteocyte conditioned media. Interestingly, many of these differentially expressed cytokines, which were significantly down regulated in this study by flow activation, have previously been demonstrated to play a role in myogenesis. Il-4 and Il-13 have been demonstrated to induce muscular hypertrophy by increasing the recruitment of reserve myoblasts for fusion to myofibers (Jacquemin et al., 2007). Similarly, IL-1β is associated with an increase in the level of myogenic transcription factors MyoD and Myogenin at the onset of myofiber fusion (Hoene et al., 2013). Il-10 and M-CSF promote a macrophage phenotype involved in the regeneration of atrophied muscle (Keeling et al., 2013, Deng et al., 2012) and MIG and MIP-1a promote myoblast proliferation (Ge et al., 2013) and early differentiation. Collectively these observations suggest that flow activation of osteocytes produces a resounding inhibitory effect on myogenesis, by reducing the expression of pro-myogenic cytokines and increasing the production of inhibitory myogenic cytokines.

We also observed that IL-6 expression increased and IFN-γ expression decreased in flow activated compared to static osteocyte conditioned media, however the meaning of this finding was harder to interpret because the roles of these cytokines in myogenesis remains unclear. It has been demonstrated in C2C12 myoblasts that IL-6 induces the activation of the Stat3 signalling and promotes the down regulation of the p90RSK/eEF2 and mTOR/p70S6K, resulting in inhibition of the myogenic program (Pelosi et al., 2014). However, IL-6 has also been demonstrated to play a role in promoting myogenic differentiation of mouse skeletal muscle cells by autocrine activation of STAT3 and Socs3 cascade (Hoene et al., 2013). Similarly, IFN-γ has been shown to be both promote and inhibit myogenesis. Exogenous IFN-γ has been shown to influence the proliferation and differentiation of cultured myoblasts (Legoedec et al., 1997). However, IFN-γ has also been reported to inhibit myogenesis through a direct inhibition of myogenin (Londhe and Davie, 2011) and inhibition of myoblast proliferation and fusion (Kalovidouris et al., 1993).

If we extrapolate our findings into a wider context, it appears as though we observed osteocytes simultaneously promoting osteogenesis (via mechanical stimulation) and inhibiting myogenesis. We demonstrated that CM from static osteocytes inhibited myogenesis and this effect is further increased when cells are exposed to mechanical forces (fluid flow). Our findings suggest that mechanically-stimulated osteocytes signal for bone production at the expense of muscle generation. Osteocytes, in response to loading, increase bone production by increasing osteoblast and decreasing osteoclast formation through SOST/sclerostin and RANKL respectively. Given that osteocytes producing inhibitory myogenic cytokines it appears as though molecules secreted by both static and activated osteocytes may either permeate the periosteum or move through the circulation to modulate myogenesis. Further studies need to be conducted to determine the extent to osteocytes, both static and flow activated, inhibit myogenesis, and if our in vitro observations translate to the in vivo setting. Furthermore, this study and the observed effects on skeletal muscles number and size, suggests that future studies should also examine the mTOR pathway which has been shown to be a crucial pathway for muscle hypertrophy (Bodine et al., 2001).

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that osteocytes inhibit myogenesis, with a specific affinity for late differentiation. We have also identified numerous cytokines present in the osteocyte secretome, which may begin to explain how osteocytes inhibit myogenesis. Our findings suggest that the underlying physiological mechanism that is at play is that when osteocytes sensing a load bearing dynamic environment they simultaneously signal for bone remodelling and inhibition of myogenesis by secreting numerous bone specific cytokines.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2017.02.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary figures.

References

- Bodine S.C., Stitt T.N., Gonzalez M., Kline W.O., Stover G.L., Bauerlein R., Zlotchenko E., Scrimgeour A., Lawrence J.C., Glass D.J., Yancopoulos G.D. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:1014–1019. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burattini S., Ferri P., Battistelli M., Curci R., Luchetti F., Falcieri E. C2C12 murine myoblasts as a model of skeletal muscle development: morpho-functional characterization. Eur. J. Histochem. 2004;48(3):223–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger E.H., Klein-Nulend J. Mechanotransduction in bone - role of the lacuno-canalicular network. FASEB J. 1999;13:S101–S112. (Suppl.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaianni G., Cuscito C., Mongelli T., Oranger A., Mori G., Brunetti G. Irisin enhances osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014;2014:902186. doi: 10.1155/2014/902186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng B., Wehling-Henricks M., Villalta S.A., Wang Y., Tidball J.G. IL-10 triggers changes in macrophage phenotype that promote muscle growth and regeneration. J. Immunol. 2012;189(7):3669–3680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGirolamo D.J., Kiel D.P., Esser K.A. Bone and skeletal muscle: neighbors with close ties. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28(7):1509–1518. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost H.M., Schonau E. The “muscle-bone unit” in children and adolescents: a 2000 overview. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;13(6):571–590. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.6.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulzele K., Lai F., Dedic C., Saini V., Uda Y., Shi C., Tuck P., Aronson J.L., Liu X., Spatz J.M., Wein M., Pajevic P.D. Osteocyte-secreted Wnt signaling inhibitor sclerostin contributes to beige adipogenesis in peripheral fat depots. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3001. (Sep 21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y., Waldemer R.J., Nalluri R., Nuzzi P.D., Chen J. RNAi screen reveals potentially novel roles of cytokines in myoblast differentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooi J.H., Pompolo S., Karsdal M.A., Kulkarni N.H., Kalajzic I., McAhren S.H. Calcitonin impairs the anabolic effect of PTH in young rats and stimulates expression of sclerostin by osteocytes. Bone. 2010;46(6):1486–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooi J.H., Chia L.Y., Walsh N.C., Karsdal M.A., Quinn J.M., Martin T.J. Decline in calcitonin receptor expression in osteocytes with age. J. Endocrinol. 2014;221(2):181–191. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick M.W., Shi X., Zhang W., Pennington C., Thakore H., Haque M. Loss of myostatin (GDF-8) function increases osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived stem cells but the osteogenic effect is ablated with unloading. Bone. 2007;40:1544–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoene M., Runge H., Haring H.U., Schleicher E.D., Weigert C. Interleukin-6 promotes myogenic differentiation of mouse skeletal muscle cells: role of the STAT3 pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;304(2):C128–C136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00025.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin V., Butler-Browne G.S., Furling D., Mouly V. IL-13 mediates the recruitment of reserve cells for fusion during IGF-1-induced hypertrophy of human myotubes. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 4):670–681. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.W., White J.D., Walker E.C., Martin T.J., Sims N.A. Myokines (muscle-derived cytokines and chemokines) including ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) inhibit osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 2014;64:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judex S., Rubin C.T. Is bone formation induced by high-frequency mechanical signals modulated by muscle activity? J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2010;10(1):3–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juffer P., Jaspers R.T., Klein-Nulend J., Bakker A.D. Mechanically loaded myotubes affect osteoclast formation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2014;94:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalovidouris A.E., Plotkin Z., Graesser D. Interferon-gamma inhibits proliferation, differentiation, and creatine kinase activity of cultured human muscle cells. II. A possible role in myositis. J. Rheumatol. 1993;20(10):1718–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling S., Deashinta N., Howard K.M., Vigil S., Moonie S., Schneider B.S. Macrophage colony stimulating factor-induced macrophage differentiation influences myotube elongation. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2013;15(1):62–70. doi: 10.1177/1099800411414871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legoedec J., Gasque P., Jeanne J.F., Scotte M., Fontaine M. Complement classical pathway expression by human skeletal myoblasts in vitro. Mol. Immunol. 1997;34(10):735–741. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londhe P., Davie J.K. Gamma interferon modulates myogenesis through the major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator, CIITA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31(14):2854–2866. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05397-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo C., Romero-Suarez S., Bonewald L., Johnson M., Brotto M. Prostaglandin E2: from clinical applications to its potential role in bone-muscle crosstalk and myogenic differentiation. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2012;6(3):223–229. doi: 10.2174/1872208311206030223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi M., De Rossi M., Barberi L., Musaro A. IL-6 impairs myogenic differentiation by downmodulation of p90RSK/eEF2 and mTOR/p70S6K axes, without affecting AKT activity. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:206026. doi: 10.1155/2014/206026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarles L.D. Role of FGF23 in vitamin D and phosphate metabolism: implications in chronic kidney disease. Exp. Cell Res. 2012;318(9):1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Suarez S., Brotto M. Wnt3a a potent modulator of myogenic differentiation and muscle cell function. FASEB J. 2012;26:1143.2. [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Asada N., Kawano Y., Wakahashi K., Minagawa K., Kawano H., Sada A., Ikeda K., Matsui T., Katayama Y. Osteocytes regulate primary lymphoid organs and fat metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013;18(5):749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H., Grimston S., Civitelli R., Thomopoulos S. Deletion of connexin43 in osteoblasts/osteocytes leads to impaired muscle formation in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015;30(4):596–605. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz J.M., Wein M.N., Gooi J.H., Qu Y., Garr J.L., Liu S. The Wnt inhibitor sclerostin is up-regulated by mechanical unloading in osteocytes in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290(27):16744–16758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.628313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbaum S., Cowin S.C., Zeng Y. A model for the excitation of osteocytes by mechanical loading-induced bone fluid shear stresses. J. Biomech. 1994 Mar;27(3):339–360. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe D., Saxel O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature. 1977;270(5639):725–727. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahiaoui L., Gvozdic D., Danialou G., Mack M., Petrof B.J. CC family chemokines directly regulate myoblast responses to skeletal muscle injury. J. Physiol. 2008;586(16):3991–4004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.