Abstract

Background

The hospital discharge summary is the primary method used to communicate a patient's plan of care to the next provider(s). Despite the existence of regulations and guidelines outlining the optimal content for the discharge summary and its importance in facilitating an effective transition to post-hospital care, incomplete discharge summaries remain a common problem that may contribute to poor post-hospital outcomes. Electronic health records (EHRs) are regularly used as a platform upon which standardization of content and format can be implemented.

Objective

We describe here the design and hospital-wide implementation of a standardized discharge summary using an EHR.

Methods

We employed the evidence-based Replicating Effective Programs implementation strategy to guide the development and implementation during this large-scale project.

Results

Within 18 months, 90% of all hospital discharge summaries were written using the standardized format. Hospital providers found the template helpful and easy to use, and recipient providers perceived an improvement in the quality of discharge summaries compared to those sent from our hospital previously.

Conclusions

Discharge summaries can be standardized and implemented hospital-wide with both author and recipient provider satisfaction, especially if evidence-based implementation strategies are employed. The use of EHR tools to guide clinicians in writing comprehensive discharge summaries holds promise in improving the existing deficits in communication at transitions of care.

Introduction

Preventing avoidable re-hospitalizations and related care costs is a clear national healthcare priority. This has led to a focus on identifying strategies for improving transitions of care at the time of hospital discharge. One component of optimizing transitions of care is improving communication between the hospital and post-discharge providers, as inadequate communication contributes to poor post-hospital outcomes.1-7 As the hospital discharge summary is the primary method used for communicating a patient's plan of care to the next provider(s), it is an essential component of any effort aimed at improving discharge communication.8

The Joint Commission mandates that a discharge summary be written for every patient within 30 days of discharge and that it include certain basic elements.9 More recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have identified core elements that must be included in summary of care documents to meet requirements for Stage 2 Eligible Hospital Meaningful Use. 10 Experts have advocated for the inclusion of additional components to improve patient safety.11 Despite the existence of these regulations and guidelines, deficits in the quality and content of discharge summaries have been well-documented.5,12-17 This may be due, at least in part, to the lack of a historical best practice format, limited standardization across inpatient services, limited tools to guide providers in writing complete discharge summaries, and inadequate training for clinicians in creating discharge summaries.17-20

The electronic health record (EHR) has been identified as a tool that may assist clinicians in creating high quality discharge summaries that consistently include guideline-based elements. Previous studies have demonstrated improvements in the quality and timeliness of specialty or disease-specific computer generated discharge summaries, and recipients have indicated some preference for these over dictated summaries.16, 21-27 However, the feasibility of designing and implementing a standardized discharge summary hospital-wide using an EHR has not been examined.

We describe the design and hospital-wide implementation of a standardized discharge summary using an EHR. Because the primary intent of this project was quality improvement, it received exemption status from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board as “not research”.

Methods

The University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics/American Family Children's Hospital is an academic medical center with 566 beds in Madison, WI. The providers use a commercial EHR (Epic Systems Corporation) for order entry and documentation.

An existing hospital task force known as QUIPDOC (Quality of Inpatient Provider Documentation) at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics (UWHC) led this project. This 24 member task force was assembled in January 2011 to develop best practices for various types of notes in the EHR and was comprised of faculty physicians (3 primary care providers, a pediatric and adult hospitalist, two geriatricians, a trauma surgeon, a cardiologist and two anesthesiologists), advanced practice providers (APPs), the director of our Transitions of Care program, residents, and staff from professional billing, hospital coding, Health Information Management (HIM), medical informatics, and information services. The objectives for this project included: 1) the identification and adoption of standardized discharge summary content guidelines and 2) the development and hospital-wide implementation of a corresponding electronic discharge summary template. This project was initiated in September 2011.

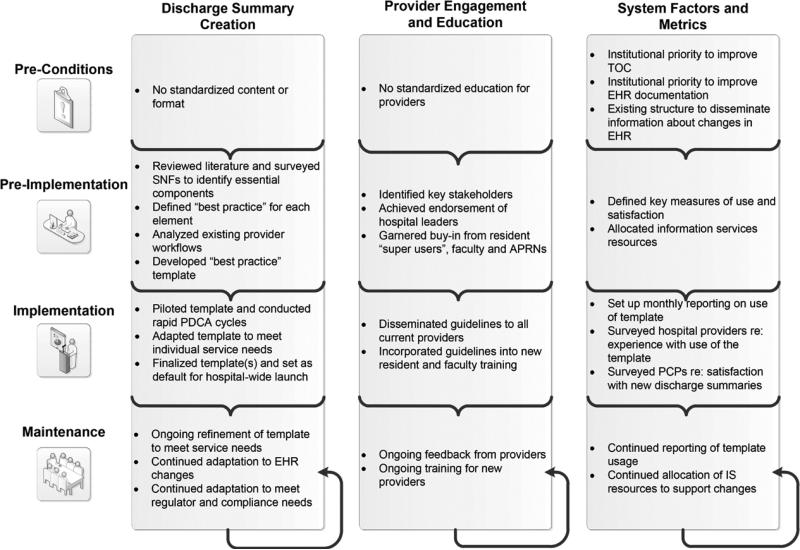

The development and implementation of the standardized discharge summary template was guided by the evidence-based Replicating Effective Programs (REP) implementation science model,28 which outlines four stages in clinical health service intervention implementation: pre-conditions, pre-implementation, implementation, and maintenance. The following sections describe the key factors or strategies used within each stage, system factors that influenced implementation, and metrics used to measure success (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Development and Implementation of a Standardized Discharge Summary using the Replicating Effective Programs Model

Abbreviations: SNF, skilled nursing facility; EHR, electronic health record; PDCA, plan, do, check, act; APRN, advanced practice registered nurse; TOC, transitions of care; PCP, primary care provider

Preconditions

Before June 2012, discharge summaries could be either dictated or written using existing EHR tools. Hospital policy specified only that a discharge summary contain the same elements as outlined by the Joint Commission. Providers received no standardized training in the creation of discharge summaries. We observed significant variation in the content and format of discharge summaries across services.

Several existing factors provided a favorable environment for the project. First, optimizing transitions of care and improving the quality of clinical documentation within the EHR were already identified as institutional priorities. Second, there was an established structure for implementing changes within the EHR: the resident “super user” program. The program involved two resident representatives from each discipline selected by program directors/peers who met monthly with informatics leaders to learn about EHR changes and to assist in communicating changes to their colleagues. Resident “super-users” also led annual EHR training for new residents and fellows.

Pre-implementation

The QUIPDOC task force reviewed published literature, sought local expertise, and surveyed local Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) prior to implementation to determine the essential components of a discharge summary (Table 1). Because patients discharged to a SNF may not be seen by a physician for up to 30-days, SNF end-users emphasized the importance of each of these items in informing their care plan. Both primary care and SNF end-users highlighted the importance of information about: medication changes and rationale, medication monitoring requirements, planned follow up, lab tests pending at discharge, active issues requiring follow up and who was responsible for that follow up.

Table 1.

Discharge Summary Elementsa

| Brief Overview | • Brief summary of reason for hospital stay • Admitting/discharging provider(s) • PCP at discharge and contact info • Admission/ discharge date • Primary and secondary diagnoses • Discharge disposition and location (if applicable) • Guardian/ POA contact information • Code status |

• Active issues requiring follow up (issue, who is managing, what is needed, associated appointments) • Medication monitoring recommendations (e.g. anticoagulation) • Scheduled follow up appointments • Recommended labs/imaging/other procedures to be performed after discharge • Test results pending at discharge |

| Details of Hospital Stay | • Presenting problem/history of present illness • Hospital course • Operative and other procedures performed • Consults • Pertinent lab results |

• Pathology results • Physical exam at discharge (including last vitals and weight) • Cognitive status at discharge |

| Detailed Discharge Recommendations | • Diet orders • Fall risk status • Activity orders • Wound care instructions • Bladder/bowel care |

• Other patient care instructions (e.g. reasons to call/ be seen, how to contact provider, specialty specific instructions such as fever and neutropenia guidelines) • Patient's goals/preferences • Discharge medications • Contact information for discharging provider if PCP has questions • Author of discharge summary |

The task force discussed each identified component until consensus was achieved on the best practice for each element. The task force next evaluated existing provider workflows for creation of discharge summaries and developed an initial standardized EHR template that contained both auto-populated elements and free text. The initial template was iteratively refined based on feedback from task force members. Once an optimal product was achieved, we created a detailed guideline to support dissemination, “The Best Practices for Writing Discharge Summaries in the EHR” (Appendix 1).

The task force identified the chairs and residency program directors of each clinical department as key stakeholders and sent the guidelines and corresponding EHR template to these individuals for approval. After achieving unanimous endorsement, task force members met with front-line providers from each of the admitting services to review the guidelines and encourage adoption of the template.

Key metrics for evaluating success of the project were identified: (1) use of the EHR template across all admitting services (2) hospital provider experience with use of the template and (3) recipient provider satisfaction with the new discharge summary format.

Implementation

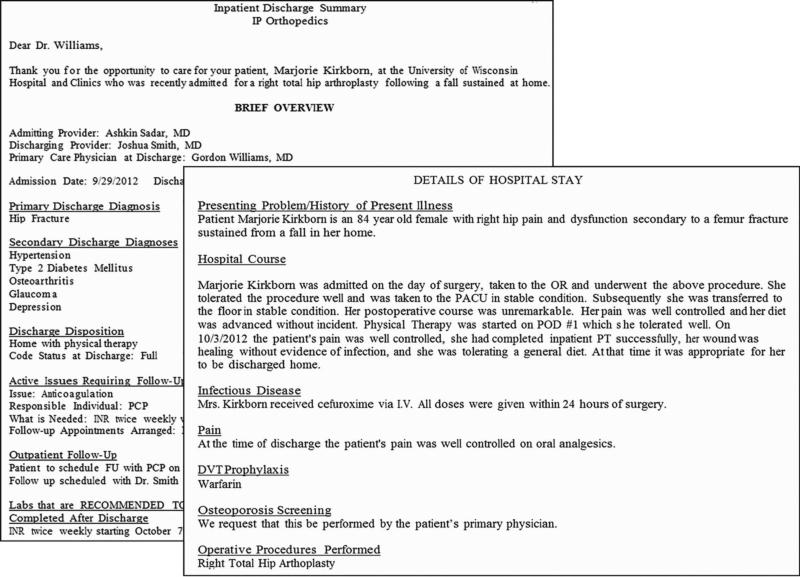

The EHR template was initially implemented in May 2012 on two services (orthopedics and rehabilitation medicine) to ensure usability. Rapid Plan-Do-Check-Act cycles were used to solicit end-user and recipient feedback, including feedback from SNF and primary care providers, and incorporate changes into the template and initial guidelines. For example, labs, radiology and other procedures to be performed after discharge were initially included in the Detailed Discharge Recommendations section. Based on early feedback from our primary care providers, these recommendations were moved to the Brief Overview section. There was recognition soon after implementation that the Operative Procedures section was pulling any procedure performed with general anesthesia (e.g. an MRI). Therefore a hard stop was added to ensure review by the author for appropriateness. Resident “super users” and/or APPs from each of the clinical services were also given the opportunity to adapt the template by adding specialty specific content. For example, the orthopedic service elected to add sections about osteoporosis screening and deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis (Figure 2) and the Stroke service added a section outlining the final determination of stroke etiology as well as a risk factor analysis. Services were not permitted to remove any of the essential elements or change the standardized format. Either the general template or specialty specific template was then tied to the “log in” department for a given service so that the template was routinely displayed when providers on that service selected the “Discharge Summary” note type in the EHR. An individual user could still elect not to use the template by deleting the automatically displayed content and instead using their own template or free-text. Individuals could also still elect to dictate the discharge summary.

Figure 2.

Example of a Discharge Summary Generated using the EHR Template

During implementation, the “Best Practices for Writing Discharge Summaries” was disseminated via email to all current providers. Resident “super users” provided additional training for their colleagues during existing educational conferences. Education about the guidelines and new template was also incorporated into EHR training for new faculty and residents.

Use of the template was tracked using both an embedded data element and a text search for key phrases found in the template. Information services generated monthly reports showing the number of discharge summaries written using the template as a percentage of all discharge summaries written during that month. Usage by individual service was also reported. These reports were provided to the Medical Director for Inpatient Informatics and presented to the resident superusers during regular monthly meetings. These reports did generate some friendly competition among house staff and served as a feedback mechanism to encourage ongoing adoption within their specialty.

We conducted an electronic survey of hospital providers soon after implementation in late September 2012 to collect usability data. To assess recipient provider satisfaction with the quality of the new discharge summary, we also conducted an email survey 15 months after implementation of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatric primary care physicians (PCPs).

Maintenance

As upgrades to the EHR occur, organizational workflows change, new regulatory and compliance needs are identified, or additional specialty service requests are made, appropriate adjustments are made to the standardized EHR templates. While the QUIPDOC task force no longer meets, approval for requests to change the existing templates are vetted through the original leader of that task force. Training about creation of the discharge summary has been integrated into EHR training for new providers.

Results

Use of Standardized Discharge Summary Template

Since implementation, 69 of 73 (95%) admitting services have adopted the standardized template. At 18 months post-implementation, 90% of all discharge summaries were written using the standardized template, with use at this level sustained.

Initial Hospital-User Experience with Standardized Discharge Summary

Soon after tool launch, hospital users were surveyed to assess tool usability. Of the 799 total residents, fellows, APPs, and hospitalist faculty available, 614 (76.8%) completed the survey. Over half of respondents (312; 50.8%) reported that they had been exposed to/used the new standardized template. Of these, 65% either agreed/strongly agreed that the new template was helpful in creating a comprehensive discharge summary. Sixty-nine percent indicated that the standardized discharge summary was easy to use compared to other templates they had used previously.

Recipient Provider Satisfaction with the Standardized Discharge Summary

One hundred nineteen (34%) of 348 primary care physicians (60 pediatricians, 200 family medicine physicians, 88 internists) completed the survey. The respondents included 29 pediatricians (24.3%), 47 family physicians (39.5%), 41 internists (34.5%), and 2 (1.7%) urgent care physicians. Ninety percent of respondents had received a discharge summary from our hospital within the 6 months prior to the survey. A sample discharge summary was also included with the survey for review by individuals not familiar with the new template. Eighty-nine percent of all respondents indicated that they liked the new outline format of the discharge summary. Eighty-eight percent of respondents who had received a discharge summary within the last 6 months rated the quality of the new discharge summaries as better/much better than discharge summaries sent from our hospital previously.

Discussion

By convening a task force, engaging hospital leaders, and harnessing expert opinion, we were able to successfully create and garner hospital wide adoption for a set of best practice guidelines for writing discharge summaries. Furthermore, we were able to implement these guidelines through use of a standardized EHR-based template for the discharge summary. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a large-scale implementation of a standardized discharge summary within an EHR.

Given the overall success of service and disease-specific discharge summary standardization and the inevitable movement toward electronic documentation, it is likely that hospital leaders aiming to meet regulatory requirements for timely and complete discharge communication will seek strategies for successful hospital-wide implementations of electronic discharge summaries. The typical organizational structure of academic and other tertiary care medical centers by department and division makes system wide implementation of any initiative a challenge. We encountered many challenges during our implementation and learned several important lessons that other institutions may find helpful if embarking on a similar initiative (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lessons Learned in Implementing a Standardized Discharge Summary

| Lessons Learned | Detailed Example |

|---|---|

| Seek multidisciplinary input, particularly from hospital coding and billing, when developing documentation standards. | ■ First identify all clinically important elements of a discharge summary then work with hospital coding and billing staff to determine which elements are required and any additional elements that must be included solely for billing/coding purposes. ■ Create a table outlining required/not required as a reference for providers. |

| Seek endorsement and support from hospital leaders. | ■ At an academic institution, buy in from both more direct providers and program directors was critical, as residents looked to them to set expectations and were hesitant to engage in the project without clear evidence of their buy-in. |

| Set standardized discharge summary as default template to promote continued use. | ■ Previous implementation of standard progress note templatesa did not include defaulted template and resulted in varied use among services. The Task Force used this knowledge in designing the discharge summary to set as the default template. Our rates of adoption directly correlated with the number of services that adopted the template as their default when logged into a specific department. |

| Provide flexibility in tailoring the discharge summary template to meet specialty specific needs. | ■ Allowing orthopedics, stroke, and other specialty services to include specialty specific information led to an enhanced, unique discharge summary for those services that provided additional information commonly applicable to their patient population. |

Adapted from Dean et al., 2015 (29).

The first challenge was to ensure that the guidelines developed by the task force would result in a discharge summary that met the clinical communication needs and the needs of its other users, namely billing and coding staff. This challenge was met by creating a multidisciplinary task force with representation from each of the key stakeholder groups. Garnering buy-in from providers across the system proved challenging and was overcome through use of both a top down and grass roots approach. Prior to engaging direct care providers, we first secured the endorsement and support of key hospital leaders and met with individual providers from the various services to explain the rationale for the project and to reassure that individual service needs could be met. An example of where this proved to be crucial was with our resident superusers who were reluctant to encourage the adoption of the new discharge summary template until their program directors endorsed its use. Sustaining use of the standardized template was a third challenge. This was overcome by creating a template that is set to display by default when providers choose the discharge summary note type. At our organization, the template has become part of the “way we do things” and is now no longer seen as a change. Finally, providing some flexibility in tailoring the discharge summary to meet individual service needs helped to facilitate adherence to the guideline.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the evaluation of this project. As the focus of this evaluation was on the uptake and end users experience both as authors and recipients of the discharge summary, neither the educational components of the implementation nor measures of discharge summary quality in terms of content, timeliness or transmission were evaluated. Hospital-users of the standardized discharge summary template may have been surveyed prematurely. At the time of the survey, only about 50% of respondents indicated they had used the new discharge summary template and responses may not be reflective of end-user experiences further into the implementation. We did not examine end-user (resident, APP, hospitalist) or recipient satisfaction with discharge summaries prior to implementation and it is possible that survey responses are subject to recall bias. The response rate for PCPs was low (34%), and this study did not examine differences between responders and non-responders.

Conclusion

Discharge summaries can be standardized and implemented hospital-wide with both author and recipient satisfaction. The use of EHR tools to guide clinicians in writing comprehensive discharge summaries holds promise in improving the existing deficits in communication at transitions of care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire QUIPDOC Task Force for their contributions to the success of this project, Dr. Ellen Wald for her assistance in the critical revisions of this manuscript, and Michael Gehring and Jacquelyn Porter for help in the preparation of this manuscript.

FUNDING

This project was supported by a National Institute on Aging Beeson Career Development Award (K23AG034551 [PI Kind], National Institute on Aging, The American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies and The Starr Foundation) and by the Madison VA Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC-Manuscript #2014-028). Dr. Kind's time was also partially supported by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. Additional support was provided by the University of Wisconsin School Of Medicine and Public Health, and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science. Dr. Gilmore-Bykovskyi's time during the preparation of this manuscript was supported by the William S. Middleton Veterans Affairs Hospital in Madison, WI and the National Hartford Centers of Gerontological Nursing Excellence.

References

- 1.Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, Kaboli PJ, Wetterneck TB, Gonzales DV, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:381–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0882-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li JY, Yong TY, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH. Timeliness in discharge summary dissemination is associated with patients' clinical outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19:76–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-2-200507190-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJ. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr. 2013;61:1095–102. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:624–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:186–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kind A, Smith M. AHRQ Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2008. Documentation of mandated discharge summary components in transitions from acute to sub-acute care. pp. 179–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Mar 12, 2014];Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (Online) Standard IM.6.10, EP 7. http://www.jointcommission.org/

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [Mar 12, 2014];Stage 2 eligible professional meaningful use core measures: summary of care. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/downloads/Stage2_EPCore_15_SummaryCare.pdf.

- 11.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, Miller DC, Potter J, Wears RL, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:971–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, Chen C, Kanade S, Van Ness PH, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):436–43. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kind A, Anderson P, Hind J, Robbins J, Smith M. Omission of dysphagia therapies in hospital discharge communications. Dysphagia. 2011;26:49–61. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walz SE, Smith M, Cox E, Sattin J, Kind AJ. Pending laboratory tests and the hospital discharge summary in patients discharged to sub-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:393–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1583-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Were MC, Li X, Kesterson J, Cadwallader J, Asirwa C, Khan B, et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow-up providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1002–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1057-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callen J, McIntosh J, Li J. Accuracy of medication documentation in hospital discharge summaries: A retrospective analysis of medication transcription errors in manual and electronic discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, Walz SE, Smith MA. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Inter. Med. 2012;27:78–84. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1860-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers JS, Jaipaul CK, Kogan JR, Krekun S, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Are discharge summaries teachable? The effects of a discharge summary curriculum on the quality of discharge summaries in an internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2006;81:S5–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000236516.63055.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frain JP, Frain AE, Carr PH. Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries. BMJ. 1996;312:350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aiyer M, Kukreja S, Ibrahim-Ali W, Aldaq J. Discharge planning curricula in internal medicine residency programs: a national survey. South Med. 2009;102:795–9. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ad5ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Archbold RA, Laji K, Suliman A, Ranjadayalan K, Hemingway H, Timmis AD. Evaluation of a computer-generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1163–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crosswhite R, Beckham SH, Gray P, Hawkins PR, Hughes J. Using a multidisciplinary automated discharge summary process to improve information management across the system. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3:473–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lissauer T, Paterson CM, Simons A, Beard RW. Evaluation of computer generated neonatal discharge summaries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1991;66:433–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.4_spec_no.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maslove DM, Leiter RE, Griesman J, Arnott C, Mourad O, Chow CM, et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:995–1001. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, Liss DT, Evans DB, Kulkarni N, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:219–25. doi: 10.1002/jhm.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callen JL, Alderton M, McIntosh J. Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:613–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, Liss DT, Baker DW. Outpatient physicians' satisfaction with discharge summaries and perceived need for an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:317–20. doi: 10.1002/jhm.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:104–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.