Abstract

The cDNA encoding human cyclophilin from the Jurkat T-cell lymphoma line has been cloned by the expression cassette polymerase chain reaction and sequenced, and an expression vector has been constructed under control of the tac promoter for efficient expression in Escherichia coli. Active cyclophilin is produced at up to 40% of soluble cell protein, facilitating a one-column purification to homogeneity. Wild-type cyclophilin was characterized for binding of the potent immunosuppressant agent cyclosporin A (Kd = 46 nM) by tryptophan fluorescence enhancement and for inhibition (IC50 = 19 nM) of cyclophilin's peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (rotamase) activity. With N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide as the substrate, recombinant human cyclophilin has a high catalytic efficiency; kcat/Km is 1.4 X 10(7) M-1.S-1 at 10 degrees C. To test the prior suggestion that a cysteine residue may be essential for catalysis and immunosuppressant binding, the four cysteines at positions 52, 62, 115, and 161 were mutated individually to alanine and the purified mutant proteins were shown to retain full affinity for cyclosporin A and equivalent catalytic efficiency as a rotamase. Clearly the cysteines play no essential role in catalysis or cyclosporin A binding. These results rule out the recently proposed mechanism [Fischer, G., Wittmann-Liebold, B., Lang, K., Kiefhaber, T. & Schmid, F. X. (1989) Nature (London) 337, 476-478)] involving the formation of tetrahedral hemithioorthoamide. Whereas mechanisms that embody other tetrahedral intermediates may be operative, an alternative mechanism is considered that involves distortion of bound substrate with a twisted (90 degrees) peptidyl-prolyl amide bond.

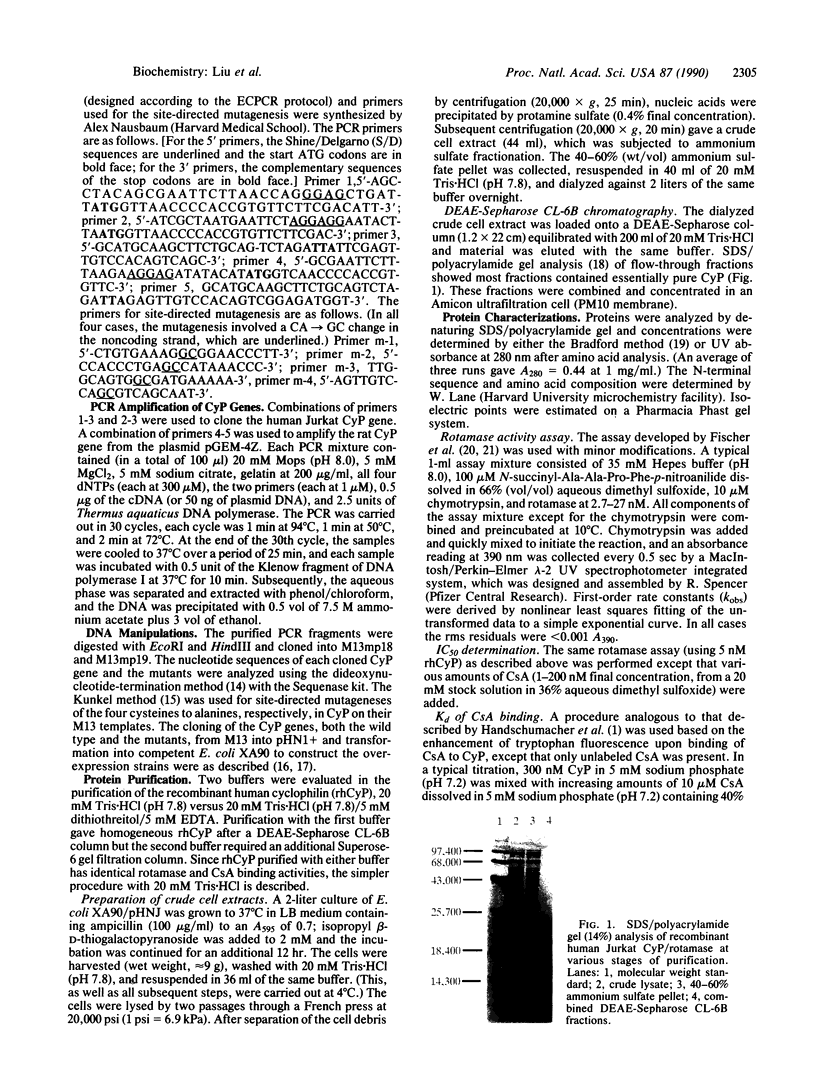

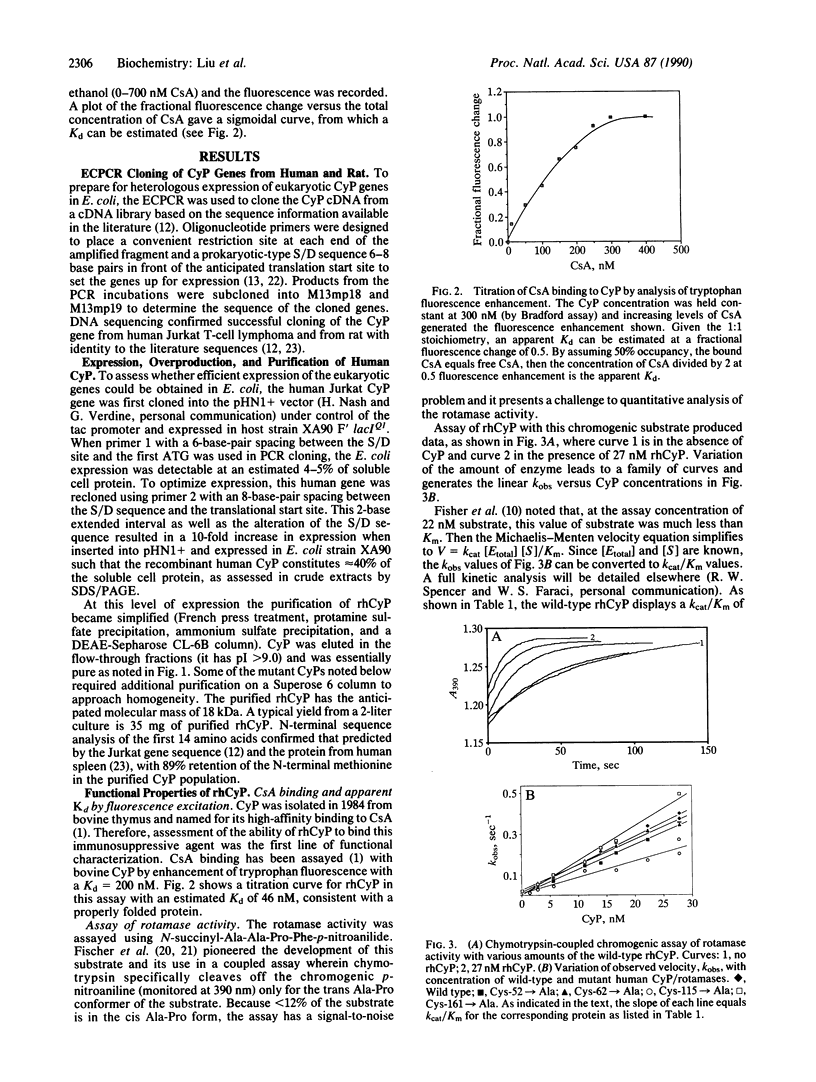

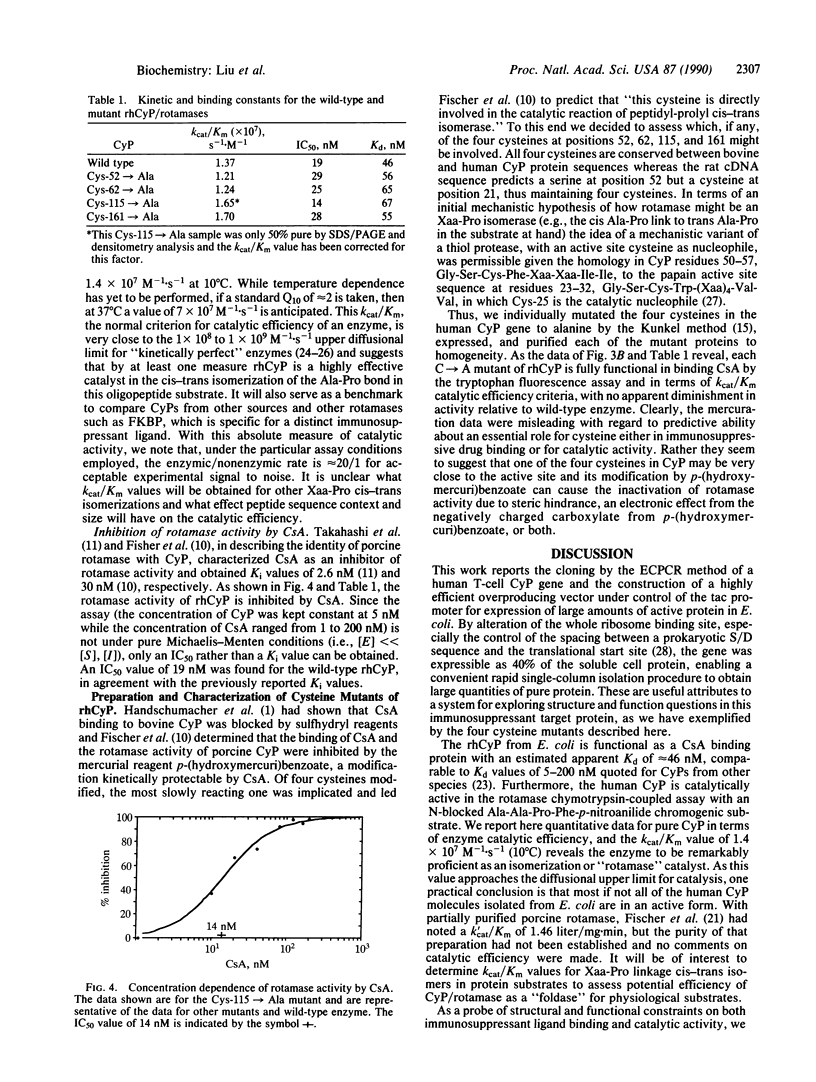

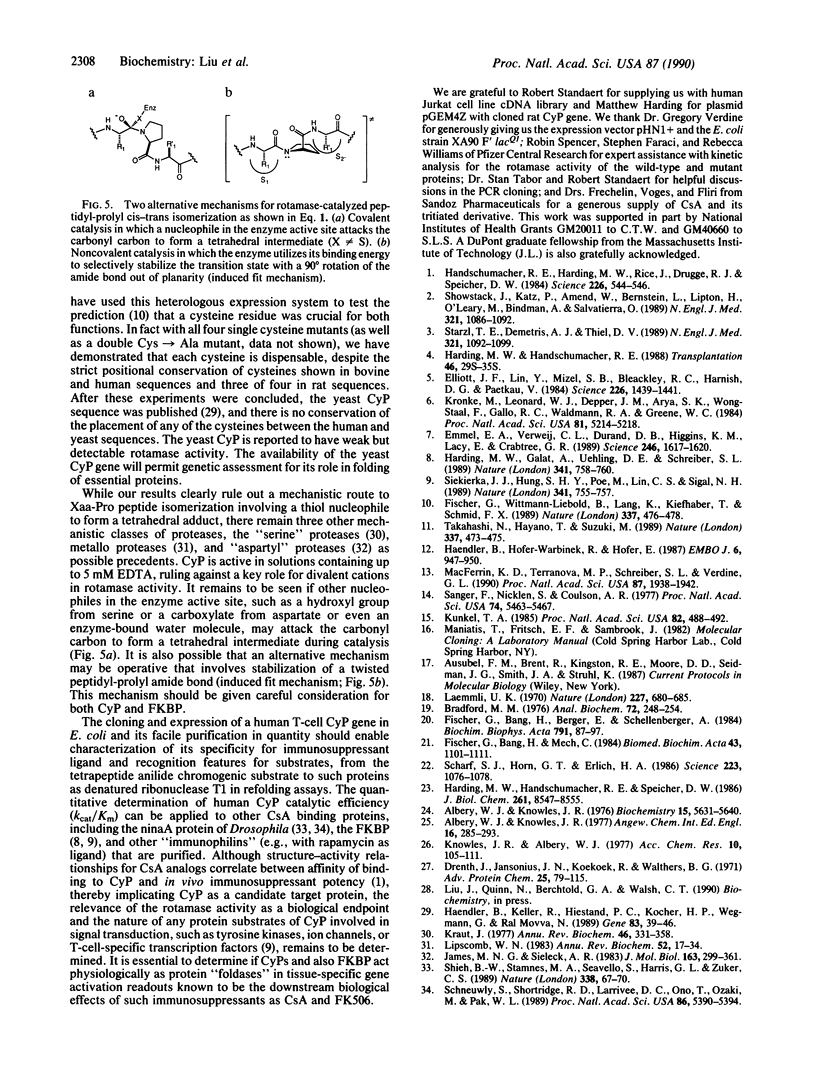

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Albery W. J., Knowles J. R. Efficiency and evolution of enzyme catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1977 May;16(5):285–293. doi: 10.1002/anie.197702851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albery W. J., Knowles J. R. Evolution of enzyme function and the development of catalytic efficiency. Biochemistry. 1976 Dec 14;15(25):5631–5640. doi: 10.1021/bi00670a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenth J., Jansonius J. N., Koekoek R., Wolthers B. G. The structure of papain. Adv Protein Chem. 1971;25:79–115. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. F., Lin Y., Mizel S. B., Bleackley R. C., Harnish D. G., Paetkau V. Induction of interleukin 2 messenger RNA inhibited by cyclosporin A. Science. 1984 Dec 21;226(4681):1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.6334364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmel E. A., Verweij C. L., Durand D. B., Higgins K. M., Lacy E., Crabtree G. R. Cyclosporin A specifically inhibits function of nuclear proteins involved in T cell activation. Science. 1989 Dec 22;246(4937):1617–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.2595372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G., Bang H., Berger E., Schellenberger A. Conformational specificity of chymotrypsin toward proline-containing substrates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 Nov 23;791(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G., Bang H., Mech C. Nachweis einer Enzymkatalyse für die cis-trans-Isomerisierung der Peptidbindung in prolinhaltigen Peptiden. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1984;43(10):1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G., Wittmann-Liebold B., Lang K., Kiefhaber T., Schmid F. X. Cyclophilin and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase are probably identical proteins. Nature. 1989 Feb 2;337(6206):476–478. doi: 10.1038/337476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendler B., Hofer-Warbinek R., Hofer E. Complementary DNA for human T-cell cyclophilin. EMBO J. 1987 Apr;6(4):947–950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendler B., Keller R., Hiestand P. C., Kocher H. P., Wegmann G., Movva N. R. Yeast cyclophilin: isolation and characterization of the protein, cDNA and gene. Gene. 1989 Nov 15;83(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschumacher R. E., Harding M. W., Rice J., Drugge R. J., Speicher D. W. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science. 1984 Nov 2;226(4674):544–547. doi: 10.1126/science.6238408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding M. W., Galat A., Uehling D. E., Schreiber S. L. A receptor for the immunosuppressant FK506 is a cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase. Nature. 1989 Oct 26;341(6244):758–760. doi: 10.1038/341758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding M. W., Handschumacher R. E. Cyclophilin, a primary molecular target for cyclosporine. Structural and functional implications. Transplantation. 1988 Aug;46(2 Suppl):29S–35S. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198808001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding M. W., Handschumacher R. E., Speicher D. W. Isolation and amino acid sequence of cyclophilin. J Biol Chem. 1986 Jun 25;261(18):8547–8555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. N., Sielecki A. R. Structure and refinement of penicillopepsin at 1.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1983 Jan 15;163(2):299–361. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut J. Serine proteases: structure and mechanism of catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:331–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krönke M., Leonard W. J., Depper J. M., Arya S. K., Wong-Staal F., Gallo R. C., Waldmann T. A., Greene W. C. Cyclosporin A inhibits T-cell growth factor gene expression at the level of mRNA transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Aug;81(16):5214–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(2):488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb W. N. Structure and catalysis of enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf S. J., Horn G. T., Erlich H. A. Direct cloning and sequence analysis of enzymatically amplified genomic sequences. Science. 1986 Sep 5;233(4768):1076–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.3461561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly S., Shortridge R. D., Larrivee D. C., Ono T., Ozaki M., Pak W. L. Drosophila ninaA gene encodes an eye-specific cyclophilin (cyclosporine A binding protein). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(14):5390–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh B. H., Stamnes M. A., Seavello S., Harris G. L., Zuker C. S. The ninaA gene required for visual transduction in Drosophila encodes a homologue of cyclosporin A-binding protein. Nature. 1989 Mar 2;338(6210):67–70. doi: 10.1038/338067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showstack J., Katz P., Amend W., Bernstein L., Lipton H., O'Leary M., Bindman A., Salvatierra O. The effect of cyclosporine on the use of hospital resources for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1989 Oct 19;321(16):1086–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siekierka J. J., Hung S. H., Poe M., Lin C. S., Sigal N. H. A cytosolic binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 has peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity but is distinct from cyclophilin. Nature. 1989 Oct 26;341(6244):755–757. doi: 10.1038/341755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzl T. E., Demetris A. J., Van Thiel D. Liver transplantation (2). N Engl J Med. 1989 Oct 19;321(16):1092–1099. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Hayano T., Suzuki M. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase is the cyclosporin A-binding protein cyclophilin. Nature. 1989 Feb 2;337(6206):473–475. doi: 10.1038/337473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]