Abstract

Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is a degenerative condition characterised by pain on activity.

Eccentric stretching is the most effective treatment.

Surgical treatment is reserved for recalcitrant cases.

Minimally-invasive and tendinoscopic treatments are showing promising results.

Cite this article: Pearce CJ, Tan A. Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. EFORT Open Rev 2016;1:383-390. DOI: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.160024.

Keywords: Achilles tendinopathy; non-insertional,aetiology; clincal presentation; non-operative treatment; operative treatment

Introduction

Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is one of a number of overuse conditions. The term ‘tendinosis’ was used by Puddu1 in 1976 to describe the histological degenerative changes of this condition. These include loss of the normal collagenous architecture and replacement with an amorphous mucinous material, hypercellularity, increased glycosaminoglycans and neovascularisation.2-4 It was previously thought that inflammation was not an important factor in the disease;4-11 however in recent years, the importance of inflammation in the tendinopathological process has been under re-evaluation, and it is now thought that the inflammatory process is a contributory factor to the development of tendinopathy.12,13 As the disease is a combination of both inflammation and degeneration, the term ‘tendinopathy’ is preferred to the previously-used term ‘tendinitis’.14,15 The area of degeneration typically occurs between 2 cm and 6 cm from the insertion of the Achilles into the calcaneus. It is probably most accurate to describe the degenerative process as a failed healing response.16

Tendinopathy is the commonest pathological condition affecting the tendo Achilles and represents between 55% and 65% of disorders.17-19 The incidence of this and other overuse injuries is rising as more people regularly participate in recreational and competitive sports, and the duration and intensity of training regimes increase.20-22 The incidence of Achilles tendinopathy has been reported to be as high as 37.3 per 100 000 in some European populations.23-27 Intrinsic factors such as lower limb malalignment, leg length discrepancy28-30 and limited ankle dorsiflexion,31-32 as well as extrinsic factors such as training errors and drugs including steroids and fluoroquinolones,33-35 have been shown to contribute to the development of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy.20

Presentation

Athletes, whether elite or recreational, are the most common group to present with non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. The condition has been described in association with many different sporting activities, but it is middle- and long-distance runners who have the greatest susceptibility to it.18,20,36-40 The annual incidence in high-level club runners was found to be between 7% and 9% in a study by Lysholm and Wiklander.41 Athletic activity is not, however, the only predisposing factor to the development of Achilles tendinopathy. In one series, 18 of 58 patients with achillodynia had no direct association with sports or vigorous physical activity.11 Another retrospective study also found various statistically significant correlations between tendinopathy and diabetes mellitus, obesity and hypertension.42

The major symptom in non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is pain, which can significantly interfere with function and especially athletic activity. As with other tendinopathies and fasciopathies (plantar fasciitis and Jumper’s knee, for example), the pain is often at its most intense on first moving after a period of rest. A diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy can usually be made clinically on the basis of history and presentation. Patients often present with pain and swelling on the posteromedial side of the tendon (Fig. 1) and tenderness can usually be elicited with palpation over the swelling.43

Fig. 1.

Posteromedial swelling of the Achilles tendon due to tendinopathy.

Tests for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy can be divided into palpation tests (tendon thickening, crepitus, pain on palpation, the Royal London Hospital (RLH) test, the painful arc sign), and tendon loading tests (pain on passive dorsiflexion, pain on single heel raise and pain on hopping).

The painful arc sign, in which a sensitive swelling moves upon ankle movement, indicates tendinopathy rather than paratendonitis.44 In the RLH test there is a swelling that is most painful on ankle dorsiflexion.45 Maffulli et al studied the sensitivity and specificity of palpation, the painful arc sign and the RLH test in 2003 and found that all three tests had good interobserver agreement. The study proposed that these three tests be used in the clinical diagnosis of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy.46 However, there has been concern about selection bias in that paper due to the distinct patient population studied (male athletes waiting for surgery).45,47 A later study by Hutchinson et al in 2013 which studyied the ten clinical tests mentioned above found only two of the tests (location of pain and pain to palpation) to be sufficiently reliable and accurate for clinical use.45 A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that the most appropriate clinical reference standard for diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy needed further investigation.47

Imaging

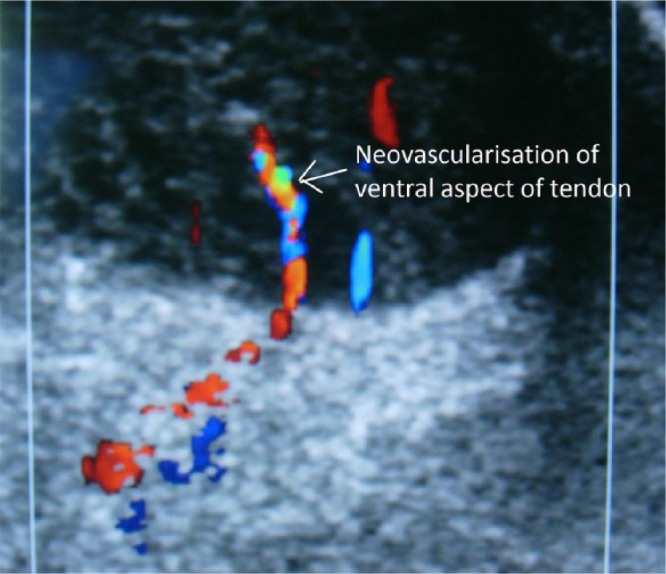

Imaging techniques including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans48,49 can occasionally be useful to identify the nature, location and extent of a lesion. Ultrasound may be particularly useful with the addition of power Doppler sonography (Fig. 2), as the pain in Achilles tendinopathy seems to be related to areas of neovascularisation.2,50,51 It has been shown that new, pain transmitting nerve endings (neonerves) grow into the tendon with the new vessels, and those treatment modalities which reduce the amount of neovascularisation can lead to a reduction in symptoms.52-56

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound scan showing ventral neovascularisation within the transverse section of the Achilles tendon on colour Doppler.

Equally, treatments that have proven to be clinically effective have subsequently been shown to reduce neovascularisation within the tendon, although the quality of evidence for this has recently been challenged.57-59 Ultrasound may also be used to guide the various injection therapies available.

Both ultrasound and MRI scans have traditionally been considered to have similar accuracy in the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy. Furthermore, the severity of radiological pathology also correlates positively with patients’ symptoms.48 Few studies have compared ultrasound with MRI in the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy. Early studies seem to indicate that MRI scans are better for characterising degeneration in the tendo Achilles.60,61 However, later research has shown equal62 or better accuracy with ultrasound when compared with MRI scans in the detection of tendinopathy. Of note, greyscale ultrasound was found to be more sensitive, whereas colour Doppler ultrasound had higher correlation with patients’ symptoms.63 We recommend ultrasound as it is generally more cost-effective.

Newer imaging modalities such as ultrasound tissue characterisation and sono-elastography have yielded promising initial results in improving sensitivity, specificity and accuracy in diagnosis.64–66 Further studies may be needed to investigate their role and application in the management of Achilles tendinopathy.

Non-operative treatment

The mainstay of management in non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is conservative, and surgery should only be considered once such conservative measures have failed. The first step may be to remove the precipitating factors by resting or modifying training regimes. Foot and ankle malalignment may be addressed by orthotics, while decreased flexibility and muscle weakness may be treated by appropriate physiotherapy.

Eccentric exercises (Fig. 3) have been shown to be the most effective treatment for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. In Alfredson’s protocol (the most commonly-used treatment), exercises are performed in three sets of 15 repetitions, twice a day for 12 weeks.67

Fig. 3.

a) Starting position for eccentric exercise: ankle in neutral with slight knee flexion. b) Second position: ankle dorsiflexed with slight knee flexion. c) Finishing position: ankle dorsiflexed with extended knee.

This regime was demonstrated in a 2009 systematic review,68 and confirmed in a 2012 meta-analysis which outlined the best pooled data supporting eccentric exercises, with the majority of the studies adopting Alfredson’s protocol.69 Alfredson and other Scandinavian authors have reported excellent results in prospective RCTs.70,71 Outside Scandinavia, investigators have also found eccentric strengthening to be an effective non-operative intervention in the treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy; however the proportion of good and excellent results is definitely lower.72-74

At present, eccentric strengthening has become the treatment of choice for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy, with the greatest amount of evidence for its effectiveness. It requires a motivated patient but no special or expensive equipment, and has been hailed as “probably the greatest single advance in the management of this condition in the past 20 years”.75

While the most common exercise procedure is Alfredson’s protocol, isolated eccentric exercises may not work in all patients.74 Other eccentric protocols such as eccentric–concentric progressing to eccentric (Silbernagel combined)70 and eccentric–concentric (Stanish and Curwin),76 have been described. In a recent systemic review, the Silbernagel combined type exercise was found to have results equivalent to the traditional Alfredson’s protocol.77 Isotonic, isokinetic, and concentric loading have also been described, but found to be inferior to the eccentric-type exercises.78-80 In a prospective randomised controlled study, Rompe et al81 showed that eccentric strengthening plus repetitive low-energy shock-wave therapy (ESWT) was better than eccentric strengthening alone in terms of Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment - Achilles (VISA-A) scores and pain ratings at four months. The proportion of patients who were ‘completely recovered’ or ‘significantly improved’ on the Likert scale was also significantly better in the combined therapy group (82%) compared with 56% in the strengthening alone group.

Where available, ESWT should probably be the second-line treatment. When compared with eccentric strengthening in a RCT, it showed similarly favourable outcomes in Achilles tendinopathy, with around a 60% of the patients completely recovered or significantly improved in both of the treatment groups. The results were significantly better than those in the ‘wait and see’ control group.73 The success rate of 60% was lower than that seen in other studies evaluating eccentric strengthening, but this may be because one third of the patients in this study were not athletic and results are known to be worse in those individuals.74

ESWT is normally performed three times spaced at one week apart, with 2000 pulses with a pressure of 2.5 bars and a frequency of eight pulses per second. The area of maximal tenderness is treated in a circumferential pattern, starting at the point of maximal tenderness.73,81

There appear to be two aspects to the clinical response to shock-waves: one on tissue healing and the other on pain transmission. In the peripheral nervous system, ESWT leads to selective dysfunction of sensory, unmyelinated nerve fibres either directly or through the liberation of neuropetides. Changes in the dorsal root ganglion have also been reported, implicating both a central and peripheral nervous system role in mediating shock-wave-induced long-term analgesia.82 Increased levels of tissue healing factors TGF-β1 and IGF-I expression have been shown after ESWT in a rat tendinopathy model83 and a significant decrease in some interleukins84 and matrix metalloprotienases (MMPs) have been shown after shock-wave treatment on cultured tenocytes.85

In a recent systemic review, there was moderate evidence for equal short-term benefit when compared with eccentric loading, and moderate evidence of superior outcomes when combined with eccentric loading rather than eccentric loading alone.86 There is, therefore, both basic science and clinical evidence to recommend ESWT as a second-line or adjuvant treatment to an eccentric stretching programme.

Various injection therapies have been proposed in the treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy.87 In a recent systemic review,88 only ultrasound-guided sclerosing polidocanol injections seemed to yield promising results. However, these results do not appear to have been duplicated outside Scandinavia.89 The use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in the treatment of many different conditions seems to be growing exponentially, especially among sports medicine physicians. Despite the basic science theories for its effectiveness, the only well-designed RCT published on PRP in Achilles tendinopathy showed no significant difference in pain or activity level in patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy between PRP and saline injection at six, 12 or 24 weeks when combined with an eccentric stretching programme.90 A one-year follow-up study of the same group of patients91 again showed a lack of differentiation between the groups, while yet another paper also demonstrated no difference in the ultrasonographic appearance of the tendons either.92

Operative treatment

Despite what is written above, between one quarter and one third of patients will fail conservative treatment and require surgical intervention.93 Open surgery for non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy has traditionally involved a large incision and excision of all of the tendinopathological tissue, with or without augmentation with a tendon transfer (commonly flexor hallucis longus (FHL)).94

Open surgery has shown varying success rates of between 50% and 100%,95-98 with surgery for intratendinous lesions and late-presenting lesions showing significantly fewer good to excellent results.99,100 The main concern with open surgery is the risk of complications. In a large series of 432 consecutive patients from a specialist centre there was an overall complication rate of 11%.101 Surgical complications may include skin edge necrosis, wound infection, seroma formation, haematoma, fibrotic reactions or excessive scar formation, sural nerve irritation or injury, tendon rupture and thromboembolic disease.

Minimally-invasive procedures aim to reduce these risks.102As mentioned above, the pain in non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy appears to be related to the neurovascular ingrowth which comes in from the fat pad anterior to the tendon. Minimally-invasive therapies which strip the paratenon from the tendon, either directly103 or indirectly with high-volume fluid injection,104 have shown promise in relieving the symptoms of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Ventral scraping of the tendon through an ultrasound-guided, minimally-invasive approach has produced good initial results.105 In one study, this procedure has interestingly also shown improvement of tendinopathy in the contralateral tendon.106 Multiple percutaneous longitudinal tenotomies, which can be performed under ultrasound guidance, have also been described with good results and with the further advantage of being able to perform the procedure under local anaesthesia in the outpatient setting.40,107

Tendinoscopy allows ventral scraping to be done under direct vision. Promising initial108 and even longer-term results (mean seven year follow-up) with no complications have been reported for endoscopic paratenon debridement and longitudinal tenotomies.109,110

It has also been noted that patients most often present with symptoms and swelling on the medial side of the tendon, which lead to the postulation that the plantaris insertion or its association with the Achilles plays a role in the symptomatology and/or development of the condition, and that releasing or excising it may be an important part of the treatment.111 Both tendinoscopic and minimally-invasive open debridement with resection of the plantaris tendon have also shown promising results with minimal complications in both elite athletes and regular patients with non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy.43,112-115

There have been no head-to-head comparisons between the different minimally-invasive approaches and therefore it is unclear whether it is necessary to perform longitudinal tenotomies or to excise the plantaris tendon. However all of the procedures strip the anterior paratenon, so this aspect would appear to be important. All show good results and minimal complications; therefore, minimally-invasive surgical treatment would appear to be a useful intermediate step between failed conservative treatment and formal open surgery.

Conclusion

Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is a painful and debilitating condition that can affect athletes and non-athletes alike. It is not an inflammatory but a degenerative condition, the histology of which is best described as a failed healing response. The majority of patients will respond to conservative treatment, with eccentric stretching being the safest, cheapest and most effective modality which should therefore be the first line of treatment. For patients who fail conservative treatment, minimally-invasive techniques are showing promising results with low complication rates and may be a good option before considering formal open surgery.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: CJP is a member of the editorial board of the journal Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, and has been a paid speaker for Smith & Nephew and DePuy Synthes.

The above declarations have no connection or commercial link to this paper.

Funding

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1. Puddu G, Ippolito E, Postacchini F. A classification of Achilles tendon disease. Am J Sports Med 1976;4:145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alfredson H, Ohberg L, Forsgren S. Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonography and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2003;11:334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu Y, Murrell GA. The basic science of tendinopathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1528-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, Harcourt P, Astrom M. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med 1999;27:393-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murrell GA. Understanding tendinopathies. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:392-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Riley G. The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kannus P, Jozsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1991;73-A:1507-1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan KM, Bonar F, Desmond PM, et al. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Patellar tendinosis (Jumper’s knee): findings at histopathologic examination, US, and MR imaging. Radiology 1996;200:821-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alfredson H, Forsgren S, Thorsen K, Lorentzon R. In vivo microdialysis and immunohistochemical analyses of tendon tissue demonstrated high amounts of free glutamate and glutamate NMDAR1 receptors, but no signs of inflammation, in Jumper’s knee. J Orthop Res 2001;19:881-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Chronic tendinopathy tissue pathology, pain mechanisms, and etiology with a special focus on inflammation. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2008;18:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rolf C, Movin T. Etiology, histopathology, and outcome of surgery in achillodynia. Foot Ankle Int 1997;18:565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Battery L, Maffulli N. Inflammation in overuse tendon injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc 2011; 19: 213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abate M, Silbernagel KG, Siljeholm C, et al. Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration? Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khan KM, Cook JL, Kannus P, Maffulli N, Bonar SF. Time to abandon the “tendinitis” myth. BMJ 2002;324:626-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maffulli N, Khan KM, Puddu G. Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy 1998;14:840-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc 2009;17:112-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fahlström M, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Painful conditions in the Achilles tendon region in elite badminton players. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:51-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Järvinen TA, Kannus P, Maffulli N, Khan KM. Achilles tendon disorders: etiology and epidemiology. Foot Ankle Clin 2005;10:255-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kvist M. Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Med 1994;18:173-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilder RP, Sethi S. Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clin Sports Med 2004;23:55-81, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maffulli N, Sharma P, Luscombe KL. Achilles tendinopathy: aetiology and management. J R Soc Med 2004;97:472-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kader D, Saxena A, Movin T, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:239-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1996;67:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levi N. The incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Copenhagen. Injury 1997;28:311-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moller A, Astron M, Westlin N. Increasing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1996;67:479-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nyyssonen T, Luthje P, Kroger H. The increasing incidence and difference in sex distribution of Achilles tendon rupture in Finland in 1987-1999. Scand J Surg 2008;97:272-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sode J, Obel N, Hallas J, Lassen A. Use of fluroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:499-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benazzo F, Marullo M, Indino C, Zanon G. Achilles tendinopathies. In: Volpi P, ed. Arthroscopy and sport injuries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016:69-76. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lersch C, Grötsch A, Segesser B, et al. Influence of calcaneus angle and muscle forces on strain distribution in the human Achilles tendon. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012;27:955-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Waldecker U, Hofmann G, Drewitz S. Epidemiologic investigation of 1394 feet: coincidence of hindfoot malalignment and Achilles tendon disorders. Foot Ankle Surg 2012;18:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rabin A, Kozol Z, Finestone AS. Limited ankle dorsiflexion increases the risk for mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy in infantry recruits: a prospective cohort study. J Foot Ankle Res 2014;7:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gurdezi S, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan MC. Results of proximal medial gastrocnemius release for Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34:1364-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corps AN, Harrall RL, Curry VA, et al. Ciprofloxacin enhances the stimulation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 expression by interleukin-1beta in human tendon-derived cells. A potential mechanism of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3034-3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fleisch F, Hartmann K, Kuhn M. Fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy: also occurring with levofloxacin. Infection 2000;28:256-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sendzik J, Shakibaei M, Schafer-Korting M, Stahlmann R. Fluoroquinolones cause changes in extracellular matrix, signalling proteins, metalloproteinases and caspase-3 in cultured human tendon cells. Toxicology 2005;212:24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Järvinen M. Epidemiology of tendon injuries in sports. Clin Sports Med 1992;11:493-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Acute and overuse injuries correlated to hours of training in master running athletes. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:671-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kujala UM, Sarna S, Kaprio J. Cumulative incidence of Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15:133-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kvist M. Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1991;80:188-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G, Bifulco G, Binfield PM. Results of percutaneous longitudinal tenotomy for Achilles tendinopathy in middle- and long-distance runners. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:835-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lysholm J, Wiklander J. Injuries in runners. Am J Sports Med 1987;15:168-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holmes GB, Lin J. Etiologic factors associated with symptomatic achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:952-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pearce CJ, Carmichael J, Calder JD. Achilles tendinoscopy and plantaris tendon release and division in the treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Surg 2012;18:124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Williams JG. Achilles tendon lesions in sport. Sports Med 1993;16:216-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hutchison AM, Evans R, Bodger O, et al. What is the best clinical test for Achilles tendinopathy? Foot Ankle Surg 2013;19:112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maffulli N, Kenward MG, Testa V, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy with tendinosis. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:11-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reiman M, Burgi C, Strube E, et al. The utility of clinical measures for the diagnosis of achilles tendon injuries: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Athl Train 2014; 49:820-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aström M, Gentz CF, Nilsson P, et al. Imaging in chronic achilles tendinopathy: a comparison of ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging and surgical findings in 27 histologically verified cases. Skeletal Radiol 1996;25:615-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wijesekera NT, Calder JD, Lee JC. Imaging in the assessment and management of Achilles tendinopathy and paratendinitis. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2011;15:89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Andersson G, Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Nerve-related characteristics of ventral paratendinous tissue in chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:1272-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Neovascularisation in Achilles tendons with painful tendinosis but not in normal tendons: an ultrasonographic investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9:233-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neo-vascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alfredson H, Ohberg L, Zeisig E, Lorentzon R. Treatment of midportion Achilles tendinosis: similar clinical results with US and CD-guided surgery outside the tendon and sclerosing polidocanol injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:1504-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boesen MI, Torp-Pedersen S, Koenig MJ, et al. Ultrasound guided electrocoagulation in patients with chronic non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:761-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lind B, Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Sclerosing polidocanol injections in mid-portion Achilles tendinosis: remaining good clinical results and decreased tendon thickness at 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14:1327-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Willberg L, Sunding K, Ohberg L, et al. Sclerosing injections to treat midportion Achilles tendinosis: a randomised controlled study evaluating two different concentrations of Polidocanol. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ackermann PW, Renström P. Tendinopathy in sport. Sports Health 2012;4:193-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tol JL, Spieza F, Maffulli N. Neovascularisation in Achilles tendinopathy: have we been chasing a red herring? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20:1891-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Effects on neovascularisation behind the good results with eccentric training in chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinosis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2004;12:465-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Neuhold A, Stiskal M, Kainberger F, Schwaighofer B. Degenerative Achilles tendon disease: assessment by magnetic resonance and ultrasonography. Eur J Radiol 1992;14:213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Movin T, Kristoffersen-Wiberg M, Shalabi A, et al. Intratendinous alterations as imaged by ultrasound and contrast medium-enhanced magnetic resonance in chronic achillodynia. Foot Ankle Int 1998;19:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Khan KM, Forster BB, Robinson J, et al. Are ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging of value in assessment of Achilles tendon disorders? A two year prospective study. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:149-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Warden SJ, Kiss ZS, Malara FA, et al. Comparative accuracy of magnetic resonance imagining and ultrasonography in confirming clinically diagnosed patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2007;3:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van Schie HT, de Vos RJ, de Jonge S, et al. Ultrasonographic tissue characterisation of human Achilles tendons: quantification of tendon structure through a novel non-invasive approach. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1153-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ooi CC, Schneider ME, Malliaras P, et al. Diagnostic performance of sonoelastography in confirming clinically diagnosed Achilles tendinopathy: comparison with B-mode ultrasound and color Doppler imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015; 41:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Docking SI, Ooi CC, Connell D. Tendinopathy: is imaging telling us the entire story? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015; 45:842-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alfredson H, Pietilä T, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Magnussen RA, Dunn WR, Thomson AB. Nonoperative treatment of midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med 2009;19:54-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sussmilch-Leitch SP, Collins NJ, Bialocerkowski AE, Warden SJ, Crossley KM. Physical therapies for Achilles tendinopathy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 2012;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Silbernagel KG, Thomeé R, Thomeé P, Karlsson J. Eccentric overload training for patients with chronic Achilles tendon pain - a randomised controlled study with reliability testing of the evaluation methods. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2001;11:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roos EM, Engström M, Lagerquist A, Söderberg B. Clinical improvement after 6 weeks of eccentric exercise in patients with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy - a randomized trial with 1-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2004;14:286-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Maffulli N, Walley G, Sayana MK, Longo UG, Denaro V. Eccentric calf muscle training in athletic patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:1677-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rompe JD, Nafe B, Furia JP, Maffulli N. Eccentric loading, shock-wave treatment, or a wait-and-see policy for tendinopathy of the main body of tendo Achillis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:374-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sayana MK, Maffulli N. Eccentric calf muscle training in non-athletic patients with Achilles tendinopathy. J Sci Med Sport 2007;10:52-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1855-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stanish WD, Rubinovich RM, Curwin S. Eccentric exercise in chronic tendinitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;208:65-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med 2013;43:267-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Niesen-Vertommen S, Taunton J, Clement D, et al. The effect of eccentric versus concentric exercise in the management of Achilles tendonitis. Clin J Sport Med 1992;2:109-113. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Croisier J, Forthomme B, Foidart-Dessalle M, et al. Treatment of recurrent tendinitis by isokinetic eccentric exercises. Isokinet Exerc Sci 2001;9:133-141. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Superior short-term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9:42-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rompe JD, Furia J, Maffulli N. Eccentric loading versus eccentric loading plus shock-wave treatment for midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rompe JD, Furia JP, Maffulli N. Mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy–current options for treatment. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30;22:1666-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chen YJ, Wang CJ, Yang KD, et al. Extracorporeal shock waves promote healing of collagenase-induced Achilles tendinitis and increase TGF-beta1 and IGF-I expression. J Orthop Res 2004;22:854-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:508-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Han SH, Lee JW, Guyton GP, Parks BG, Courneya JP, Schon LC. J. Leonard Goldner Award 2008. Effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on cultured tenocytes. Foot Ankle Int 2009;30:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mani-Babu S, Morrissey D, Waugh C, Screen H, Barton C. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in lower limb tendinopathy: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:752-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. van Sterkenburg MN, van Dijk CN. Injection treatment for chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: do we need that many alternatives? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:513-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Maffulli N, Papalia R, D’Adamio S, Diaz Balzani L, Denaro V. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br Med Bull 2015;113:101-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. van Sterkenburg MN, de Jonge MC, Sierevelt IN, van Dijk CN. Less promising results with sclerosing ethoxysclerol injections for midportion achilles tendinopathy: a retrospective study. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2226-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:144-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. de Jonge S, de Vos RJ, Weir A, et al. One-year follow-up of platelet-rich plasma treatment in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1623-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. de Vos RJ, Weir A, Tol JL, et al. No effects of PRP on ultrasonographic tendon structure and neovascularisation in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Paavola M, Kannus P, Paakkala T, Pasanen M, Jarvinen M. Long-term prognosis of patients with achilles tendinopathy. An observational 8-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:634-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Schon LC, Shores JL, Faro FD, et al. Flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer in treatment of Achilles tendinosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2013;95-A:54-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. David S, Nauk T, Lohrer H. Surgical treatment for midportion Achilles tendinopathy - a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:e3. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kvist H, Kvist M. The operative treatment of chronic calcaneal paratenonitis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1980;62-B:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schepsis AA, Leach RE. Surgical management of Achilles tendinitis. Am J Sports Med 1987;15:308-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Snook GA. Achilles tendon tenosynovitis in long-distance runners. Med Sci Sports 1972;4:155-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Paavola M, Kannus P, Orava S, Pasanen M, Jarvinen M. Surgical treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a prospective seven month follow up study. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:178-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Maffulli N, Binfield PM, Moore D, King JB. Surgical decompression of chronic central core lesions of the Achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Paavola M, Orava S, Leppilahti J, Kannus P, Jarvinen M. Chronic Achilles tendon overuse injury: complications after surgical treatment. An analysis of 432 consecutive patients. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Spiezia F, Denaro V. Minimally invasive surgery for Achilles tendon pathologies. Open Access J Sports Med 2010;1: 95-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Longo UG, Ramamurthy C, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Minimally invasive stripping for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:1709-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chan O, O’Dowd D, Padhiar N, et al. High volume image guided injections in chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:1697-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Alfredson H. Ultrasound and Doppler-guided mini-surgery to treat midportion Achilles tendinosis: results of a large material and a randomised study comparing two scraping techniques. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:407-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Alfredson H, Spang C, Forsgren S. Unilateral surgical treatment for patients with midportion Achilles tendinopathy may result in bilateral recovery. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1421-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Testa V, Capasso G, Benazzo F, Maffulli N. Management of Achilles tendinopathy by ultrasound-guided percutaneous tenotomy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002; 34:573-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Maquirriain J, Ayerza M, Costa-Paz M, Muscolo DL. Endoscopic surgery in chronic Achilles tendinopathies: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy 2002;18:298-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Maquirriain J. Surgical treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy: long-term results of the endoscopic technique. J Foot Ankle Surg 2013;52:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Phisitkul P. Endoscopic surgery of the Achilles tendon. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2012;5:156-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Steenstra F, van Dijk CN. Achilles tendoscopy. Foot Ankle Clin 2006;11:429-438, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Alfredson H. Midportion Achilles tendinosis and the plantaris tendon. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1023-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Calder JD, Freeman R, Pollock N. Plantaris excision in the treatment of non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1532-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Masci L, Spang C, van Schie HTM, Alfredson H. Achilles tendinopathy—do plantaris tendon removal and Achilles tendon scraping improve tendon structure? A prospective study using ultrasound tissue characterisation. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2015;1:e000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. van Sterkenburg MN, Kerkhoffs GM, Kleipool RP, Niek van Dijk C. The plantaris tendon and a potential role in mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: an observational anatomical study. J Anat 2011;218:336-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]