ABSTRACT

ICE6013 represents one of two families of integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) identified in the pan-genome of the human and animal pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. Here we investigated the excision and conjugation functions of ICE6013 and further characterized the diversity of this element. ICE6013 excision was not significantly affected by growth, temperature, pH, or UV exposure and did not depend on recA. The IS30-like DDE transposase (Tpase; encoded by orf1 and orf2) of ICE6013 must be uninterrupted for excision to occur, whereas disrupting three of the other open reading frames (ORFs) on the element significantly affects the level of excision. We demonstrate that ICE6013 conjugatively transfers to different S. aureus backgrounds at frequencies approaching that of the conjugative plasmid pGO1. We found that excision is required for conjugation, that not all S. aureus backgrounds are successful recipients, and that transconjugants acquire the ability to transfer ICE6013. Sequencing of chromosomal integration sites in serially passaged transconjugants revealed a significant integration site preference for a 15-bp AT-rich palindromic consensus sequence, which surrounds the 3-bp target site that is duplicated upon integration. A sequence analysis of ICE6013 from different host strains of S. aureus and from eight other species of staphylococci identified seven divergent subfamilies of ICE6013 that include sequences previously classified as a transposon, a plasmid, and various ICEs. In summary, these results indicate that the IS30-like Tpase functions as the ICE6013 recombinase and that ICE6013 represents a diverse family of mobile genetic elements that mediate conjugation in staphylococci.

IMPORTANCE Integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) encode the abilities to integrate into and excise from bacterial chromosomes and plasmids and mediate conjugation between bacteria. As agents of horizontal gene transfer, ICEs may affect bacterial evolution. ICE6013 represents one of two known families of ICEs in the pathogen Staphylococcus aureus, but its core functions of excision and conjugation are not well studied. Here, we show that ICE6013 depends on its IS30-like DDE transposase for excision, which is unique among ICEs, and we demonstrate the conjugative transfer and integration site preference of ICE6013. A sequence analysis revealed that ICE6013 has diverged into seven subfamilies that are dispersed among staphylococci.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, conjugation, gene transfer, mobile genetic elements

INTRODUCTION

The pan-genome of Staphylococcus aureus contains many types of mobile genetic elements, including those mediating horizontal gene transfer and those utilizing agents of horizontal transfer to spread between strains (1, 2). In S. aureus, the roles of transducing phages and conjugative plasmids in the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance determinants and virulence factors continue to be documented (3–7), but little is known about the function of integrative conjugative elements (ICEs) in this species. ICEs, also known as conjugative transposons (Tn's), are maintained primarily by integration into a bacterial chromosome or plasmid and are horizontally transferred by self-encoded conjugation functions (8). ICEs may be the most common agents of conjugation in bacteria (9), and they may affect bacterial fitness, mobilize genetic elements that are not self-transmissible, and mobilize chromosomal DNA in various species (10, 11).

Two distinct families of ICEs, represented by Tn5801 (12) and ICE6013 (13), have been identified in S. aureus. Tn5801 belongs to the Tn916 family, which are prototypical conjugative transposons that encode tetracycline resistance and are broadly distributed among Gram-positive bacteria (14). ICE6013 has some sequence similarities to ICEBs1 from Bacillus subtilis but differs substantially in gene content and constitutes a separate family (13). The function and diversity of ICE6013 are largely unexplored. Of note, an IS30-like DDE transposase (Tpase) encoded by orf1 and orf2 of ICE6013 has been hypothesized to be the recombinase of ICE6013 (13). This hypothesis is based on the observations that ICE6013 carries the IS30-like Tpase instead of a phage-like tyrosine recombinase that is used by many ICE families, including ICEBs1, and that ICE6013 excision-deficient strains have a natural Tn552 disruption of orf2. However, IS30-like Tpases acting as ICE recombinases have not yet been experimentally demonstrated. TnGBS from Streptococcus agalactiae and ICEA from Mycoplasma agalactiae are the only examples of ICEs demonstrated to use a Tpase as their recombinase (15, 16); a Tpase from the p-MULT superfamily, which does not include IS30, is used for the excision of both elements (17).

Independent IS30 elements in Escherichia coli insert near sequences that resemble their inverted repeats and in hot spots characterized by a 24-bp palindromic consensus sequence within which the 2-bp target site occurs (18, 19). ICE6013 was noted to have relatively low integration site specificity, since the 3-bp target site that forms a direct repeat upon integration was variable in sequence and integration occurred at 11 different loci among 12 different strains of S. aureus (13). According to one analysis, the ICE6013 integration site in strain MRSA252 is adjacent to the strongest hot spot for recombination in the S. aureus chromosome (20). However, neither the integration site preference nor the conjugative transfer of ICE6013 or its flanking chromosomal sequences has been experimentally demonstrated.

ICE6013 was found in 15 of 34 (44%) tested multilocus sequence types of S. aureus, and it was found in all isolates of epidemic methicillin-resistant clones ST239 and North American ST8-USA300 (13, 21). It has also been identified in a closely related bacterium called S. aureus CC75, which has been proposed as a separate species, Staphylococcus argenteus (22). The patchy distribution of ICE6013 across S. aureus strain backgrounds indicates that the element either was present in the most recent common ancestor of S. aureus and lost in certain backgrounds or was introduced or developed within S. aureus and has been horizontally transferred between strain backgrounds. A demonstration of ICE6013 conjugative transfer would help fulfill its qualifications as a genuine ICE. The goals of this study were (i) to test the hypothesis that the IS30-like Tpase is a recombinase for ICE6013, (ii) to demonstrate the conjugative transfer of ICE6013, and (ii) to further characterize the diversity of this element.

RESULTS

ICE6013 excision under different growth conditions.

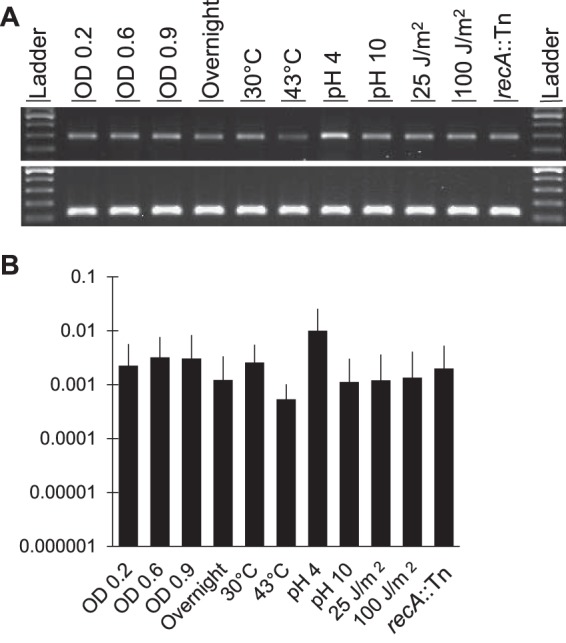

ICE6013 was previously shown to excise from the S. aureus chromosome and form circular molecules (13). These excised circular forms of ICE6013 contain the 8-bp imperfect inverted repeat ends of the element separated by a 3-bp coupling sequence that represents the 3-bp direct repeats flanking the element in its integrated form (13). Here, we first examined the presence of excised circular forms by outward-directed PCR amplification of the coupling sequence region (Fig. 1A). A quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay was developed to precisely measure the level of ICE6013 excision based on the presence of an empty chromosomal integration site. No statistically significant differences in excision were detected throughout growth, and on average, frequencies ranged from 0.001 to 0.003 (i.e., 0.1% to 0.3%) (Fig. 1B). Neither exposure to a high or low temperature nor exposure to a high or low pH significantly affected excision, though pH 4 produced the most excision among the tested conditions (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

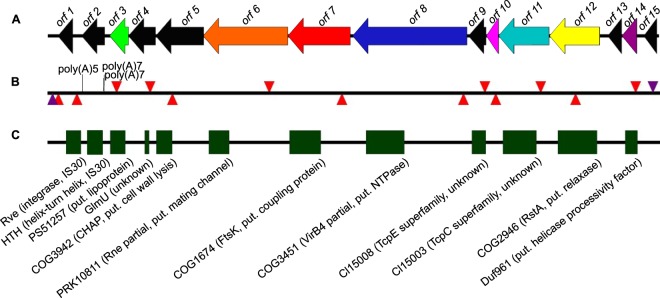

Gene map of ICE6013. (A) Arrows show 15 ORFs of ICE6013, with eight homologs found in ICEBs1 and/or Tn916 colored as in reference 13. (B) Arrowheads show PCR primer sites for detecting ICE6013 circular forms (purple) and Tn insertion sites for various mutants used in this study (red). (C) Blocks show sites that encode conserved domains. The putative product or function of ORFs is noted in parentheses; annotation is based on strain DAR6247.

ICEBs1 has a phage-like tyrosine recombinase and excises at a higher rate upon DNA damage and in a recA-dependent manner (23). To determine if DNA damage induces the excision of ICE6013, strains JE2 and RN4220 were UV irradiated at 25 J/m2 and 100 J/m2. Although these two UV doses reduced JE2 viability to 56% and 28% of the no-UV control, respectively, no significant differences in ICE6013 excision were detected after exposure (Fig. 1B). To test whether ICE6013 excision required recA, a recA mutant was assayed for excision under standard conditions (growth at 37°C in brain heart infusion [BHI] broth to an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.6). No significant difference in ICE6013 excision was detected in the recA mutant (Fig. 1B). Together, these results show that ICE6013 excision is not significantly affected by these environmental conditions and does not require recA.

ICE6013 excision depends on its IS30-like Tpase.

ICE6013 encodes an IS30-like Tpase for which the coding region encompasses orf1 and orf2 (Fig. 2). Previous work found that ICE6013 excision-deficient strains had a natural Tn552 disruption at the 3′ end of orf2 (13). To test the hypothesis that uninterrupted IS30-like Tpase is required for excision, we measured excision in strain DAR6250, which has a mariner-based Tn insertion between orf1 and orf2. No evidence for a circular form or an empty integration site was obtained for DAR6250 despite detection of gyrB in every test run of this strain (Fig. 3). To complement the Tn insertion, a 1,242-bp amplicon spanning the entirety of wild-type (WT) orf1 and orf2 was cloned into plasmid pMK4 to enable the uninterrupted expression of the IS30-like Tpase. The complemented strain restored the ICE6013 excision (Fig. 3). We also explored whether the IS30-like element itself might excise from ICE6013; no circular forms of an IS30-like element were detected by outward-directed PCR, which indicates that it is not an independent genetic element. These results demonstrate that uninterrupted orf1 and orf2 are necessary for excision of ICE6013 and support the hypothesis that the IS30-like Tpase serves as ICE6013's recombinase.

FIG 2.

Detection of excised ICE6013 in wild-type strain JE2 under various growth conditions. (A) PCR amplification of 291-bp regions around the coupling sequence of ICE6013 circular forms (top gel) and 142-bp gyrB control amplicons (bottom gel) using 25 cycles. Ladder, 100-bp ladder (Promega). Other lanes show amplicons for growth conditions that differ by growth phase, temperature, medium pH, or UV irradiation dose or from a recA mutant. (B) qPCR was used to measure the empty integration site of ICE6013 relative to a 100% excision control (strain RN4220) grown under the same conditions and relative to gyrB as described in Materials and Methods. At least three biological replicates were performed for each condition, and the means and standard deviations are shown on a log scale. Statistical significance was assessed by comparison to the wild type under standard growth conditions (growth at 37°C in BHI to an OD600 of ∼0.6) using a two-tailed t test. None of the comparisons were statistically significant.

FIG 3.

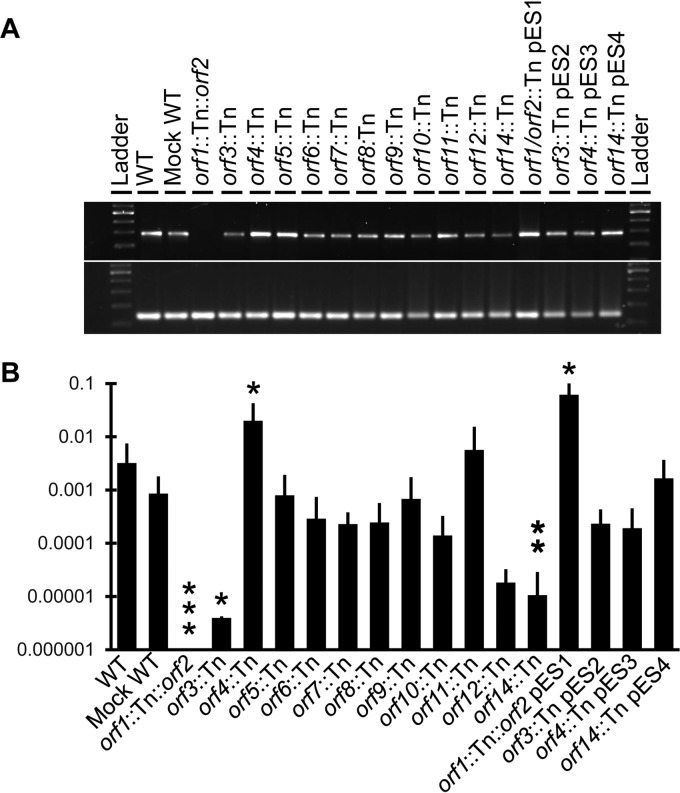

Detection of excised ICE6013 in various strains under standard growth conditions (growth at 37°C in BHI to an OD600 of ∼0.6). (A) PCR amplification of 291-bp regions around the coupling sequence of ICE6013 circular forms (top gel) and 142-bp gyrB control amplicons (bottom gel) using 25 cycles. Ladder, 100-bp ladder (Promega); WT, wild-type strain JE2. Other lanes show various mutants of JE2 with Tn insertions in ICE6013. (B) qPCR was used to measure the empty integration site of ICE6013 relative to a 100% excision control (strain RN4220) grown under the same conditions and relative to gyrB as described in Materials and Methods. At least three biological replicates were performed for each strain, and the means and standard deviations are shown on a log scale. Statistical significance was assessed by comparison to the wild type under standard growth conditions using a two-tailed t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001.

Other ICE6013 ORFs that alter excision.

Disruption of several open reading frames (ORFs) of ICE6013, besides orf1 and orf2, visibly affected the level of ICE6013 excision (Fig. 3A). Indeed, there was a significant decrease in excision in the orf3 and orf14 mutants and a significant increase in excision in the orf4 mutant (Fig. 3B). The characteristics of ICE6013 excision for these three (orf3, orf4, and orf14) mutants were each complemented (Fig. 3B). Thus, while uninterrupted orf1 and orf2 are necessary for excision of ICE6013, the other genes on the element influence the level of excision.

Intraspecies conjugative transfer of ICE6013.

Strain DAR6247 was chosen as a mock wild type for conjugation experiments because its Tn insertion between the left end of ICE6013 and orf1 provides an erythromycin resistance marker without disrupting an annotated gene (Fig. 1B) and its excision frequency was not significantly different from that for the wild type (Fig. 3B). ICE6013 from DAR6247 conjugatively transferred to RN4220RS at a frequency of 1.16 × 10−7 (±7.2 × 10−8) transconjugants per donor (Table 1). This transfer frequency was 58% of that obtained with the conjugative plasmid pGO1 used as a positive control. Conjugation experiments were also performed using the mutants with Tn insertions in ICE6013 ORFs as donors. Besides the mock wild-type strain and the complemented mutants, only the highly excising orf4 mutant was capable of conjugation (Table 1). To test for the mobilization of chromosomal DNA flanking the integration site, strains that contain wild-type ICE6013 as well as Tn insertions at sites 1.4 kb to 50 kb upstream or downstream of the integration site were used as donors. No evidence for mobilization of chromosomal DNA was obtained (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Conjugation frequencies of ICE6013

| Donor | Recipient | Conjugation frequency per donor (avg ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Conjugation positive control ROC | RN4220RS | 2.01 × 10−7 ± 1.3 × 10−7 |

| Donors with Tn insertions within ICE6013 | ||

| Mock WT | RN4220RS | 1.16 × 10−7 ± 7.2 × 10−8 |

| orf1::Tn::orf2 mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf3::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf4::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 7.26 × 10−8 ± 6.8 × 10−8 |

| orf5::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf6::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf7::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf8::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf9::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf10::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf11::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf12::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf14::Tn mutant | RN4220RS | 0 |

| orf1::Tn::orf2(pES1) strain | RN4220RS | 1.00 × 10−7 ± 8.8 × 10−8 |

| orf3::Tn(pES2) strain | RN4220RS | 9.58 × 10−9 ± 8.3 × 10−9 |

| orf14::Tn(pES4) strain | RN4220RS | 1.30 × 10−9 ± 3.5 × 10−10 |

| Donors with Tn insertions flanking ICE6013 | ||

| NE1621 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE1843 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE578 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE960 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE1193 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE1000 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE1504 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE1419 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| NE872 | RN4220RS | 0 |

| Donors for conjugative transfer to different strains and species | ||

| Mock WT | DAR5454RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR5447RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR5465RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR5461RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6462RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6464RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6465RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6466RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6468RS | 0 |

| Mock WT | DAR6469RS | 2.81 × 10−9 ± 1.10 × 10−10 |

| EAS1 | DAR6464RS | 7.91 × 10−8 ± 2.80 × 10−8 |

Using the mock wild-type strain as a donor, ICE6013 was tested for its ability to transfer to a variety of S. aureus strain backgrounds. Conjugation occurred with DAR6469RS of the ST5 background as a recipient but at a lower frequency than with RN4220RS, which is more closely related to the donor strain (Table 1). By contrast, no transconjugants were obtained with the mock wild type as the donor and a different recipient of the ST5 background or with recipients of the ST1 and ST22 backgrounds (Table 1). To test for the acquisition of conjugative abilities, a transconjugant (EAS1) derived from the conjugation with DAR6469RS was tested for the transfer of ICE6013 to a recipient of the ST22 background (DAR6464RS). The transconjugant transferred ICE6013 to DAR6464RS at a frequency of 7.91 × 10−8 (±2.80 × 10−8) (Table 1). In summary, these results demonstrate that ICE6013 is conjugative, that excision is required for conjugative transfer of the element, that not all S. aureus backgrounds are successful recipients, and that transconjugants acquire the ability to further transfer ICE6013.

ICE6013 integration site preference.

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on transconjugants from the mating of the mock wild type with RN4220RS, and only extrachromosomal circular forms of ICE6013 were detected in their genome assemblies. Transconjugants were then serially passaged either in BHI with erythromycin (Ery) for 10 days or on brain heart agar with Ery (BHA-Ery) for 16 days to encourage integration of ICE6013 and were then sequenced. Again, only circular forms of ICE6013 were detected in their genome assemblies. All circular forms had the 3-bp coupling sequence of the donor strain.

To identify possible rare ICE6013 integrations that were undetected in genome assemblies, we developed a Tn sequencing (TnSeq)-like approach with PCR enrichment of ICE6013's left end and adjacent sequences. Transconjugants from each of the BHI-Ery and BHA-Ery passages were included in this experiment, along with the mock wild-type strain as a control. Each of the detected integrated forms of ICE6013 from the mock wild type was in its known integration site, and the frequency of circular forms (0.38%) (Table 2) was higher than the qPCR estimate for excision (mean, 0.085%; standard deviation [SD], 0.094%) (Fig. 3B). For the BHI-Ery-passaged transconjugant, 1.5% of the processed reads were integrated forms spread among 68 different integration sites (Table 2). For the BHA-Ery-passaged transconjugant, 15.6% of the processed reads were integrated forms spread among six different integration sites (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Results of TnSeq-like assay for ICE6013 integrated and circular forms

| Samplea | No. of reads after processingb | No. (%) of processed reads showing ICE6013 circular form | No. (%) of processed reads showing ICE6013 integrated form | No. of different integration sites detected | No. (%) of most frequent integration sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mock WT | 113,519 | 432 (0.38) | 113,087 (99.62) | 1 | 113,087 (100) |

| TC passaged in BHI-Ery broth | 148,609 | 146,449 (98.55) | 2160 (1.45) | 68 | 622 (28.80) |

| TC passaged on BHA-Ery plates | 89,310 | 75,401 (84.43) | 13,909 (15.57) | 6 | 13,198 (94.89) |

The mock WT was not serially passaged and was included as a control strain. Transconjugants (TC) from the conjugation of the mock WT (DAR6247) donor and RN4220RS recipient were serially passaged in BHI-Ery broth for 10 days or on BHA-Ery plates for 16 days.

Sequence reads were processed as described in Materials and Methods.

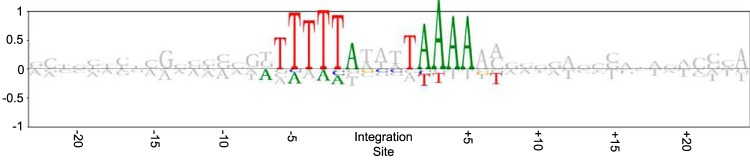

Both of the serially passaged transconjugants had evidence of ICE6013 integration into the same site as their donor parent (DAR6247) (see Table S4, red highlighting, in the supplemental material). This observation suggested that ICE6013 might have an integration site preference. To characterize the potential sequence bias in the integration site, the 58 unique unambiguous annotated sites from the transconjugants (see Table S4) were analyzed. T- and A-rich sequences to the immediate left and right of the 3-bp target site, respectively, were statistically overrepresented (Fig. 4). The 15-bp consensus sequence defining the integration site was palindromic, 5′-TTTTTANNNTAAAAA-3′, with the N′s representing the more arbitrary 3-bp target site. No preference was observed for the occurrence of the integration site on plus versus minus DNA strands (29:29), and in four instances, an integration site was found on the opposite strands of the same sequence (see Table S4, blue highlighting). No significant preference was observed for the occurrence of the integration in intergenic versus intragenic sequences (22:36, with no overlap of 95% confidence intervals on the proportions), which is consistent with results from a previous observation (13). The integration site occurs in genes of relevance to S. aureus pathogenesis (set19 and essA) and antimicrobial resistance (vraE and fmt1) and in other genes (see Table S4). Interestingly, the integration site also occurs in camS, which encodes a lipoprotein that acts as a pheromone for conjugative plasmids (24).

FIG 4.

Identification of sequence bias in 58 unique, unambiguous annotated integration sites of ICE6013 from serially passaged transconjugants. The logogram shows nucleotides that are over- and underrepresented as above and below the y axis 0 line, respectively. Nucleotides with significant bias (P < 0.05) are shown in color. The 3-bp target site that is duplicated upon integration of ICE6013 is shown at the center.

Diverse ICE6013 subfamilies in staphylococci.

ICE6013 was originally identified in human isolates of S. aureus ST239 (13), and its known host range extends to isolates that are variously classified as S. aureus CC75 or S. argenteus (22). To further characterize the diversity of ICE6013, sequences were downloaded from publicly available databases and representatives were classified on the basis of average nucleotide identity (ANI). A total of seven subfamilies of ICE6013 were found in nine staphylococcal species (Fig. 5). Sequences within subfamilies shared 94 to 100% ANI, whereas sequences from different subfamilies shared 69 to 81% ANI. The S. aureus strains ED98 (25) and S0385 (26) each carried multiple subfamilies of ICE6013 (Fig. 5). Evidence for horizontal transfer of the element was obtained by the observation that similar elements in subfamily 1 are carried by different species, such as S. aureus (68) and S. haemolyticus (27) (Fig. 5). Subfamily 3 is shared among the coagulase-positive S. intermedius group of species and the coagulase-variable S. schleiferi (28–31) (Fig. 5). The sequences from S. agnetis (32), S. saprophyticus, and S. microti (33) represent separate subfamilies.

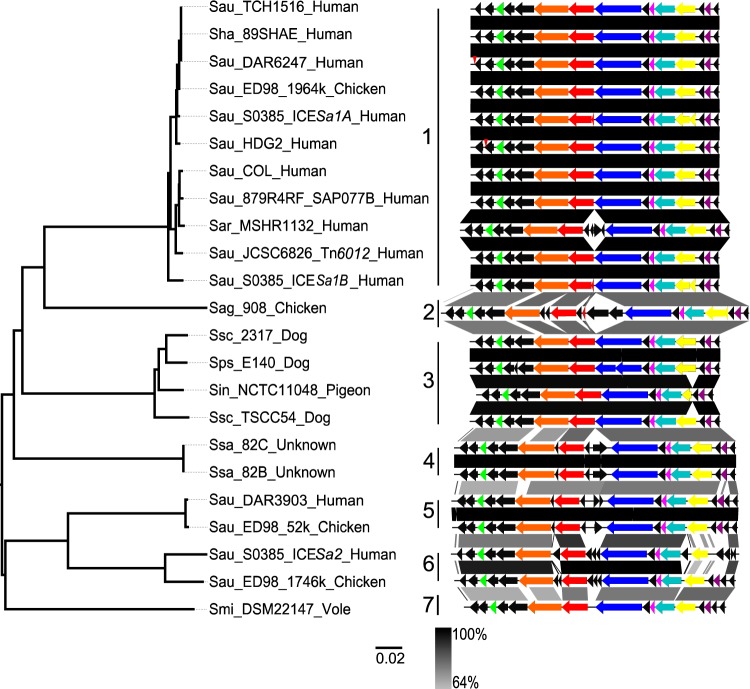

FIG 5.

Identification of ICE6013 subfamilies. The tree depicts gross differences between full-length ICE6013 sequences and was constructed from a matrix of pairwise average nucleotide identities (ANI) transformed into a distance, (100 − mean reciprocal ANI)/100, and clustered with the neighbor-joining algorithm. The sequences are labeled to indicate the staphylococcal species (Sau, S. aureus; Sag, S. agnetis; Sar, S. argenteus; Sha, S. haemolyticus; Sin, S. intermedius; Smi, S. microti; Sps, S. pseudintermedius; Ssa, S. saprophyticus; and Ssc, S. schleiferi), strain, other element name or chromosomal position, and eukaryotic host species. The adjacent gene map shows ORFs of ICE6013 as arrows, with eight homologs found in ICEBs1 and/or Tn916 colored as in Fig. 1. The vertical red arrowheads indicate the positions of a Tn552 insertion and a mariner Tn insertion in strain HDG2 and the mock wild type (DAR6247), respectively, which were removed for comparison purposes. The percentages of nucleotide identity along the sequences are indicated with gray shading.

Each of the seven subfamilies has the gene content and organization and flanking sequences that are characteristic of ICE6013. The location of the gene that encodes the putative coupling protein (orf7) (Fig. 5, red arrow) in ICE6013 is unique and helps distinguish this element from the ICEBs1 and Tn916 families (13). Some of the ICE6013 subfamilies have longer elements with additional ORFs in comparison to the prototype element from S. aureus strain HDG2 in subfamily 1 (Fig. 5; see also Table S5). These additional ORFs are poorly annotated in general, but they do not include known antimicrobial resistance determinants. Notably, the genetic elements variously classified as Tn6012 (34), plasmid SAP077B (35), and ICESa1 and ICESa2 (26) all fell within these ICE6013 subfamilies (Fig. 5).

Based on these findings, 21 veterinary clinical isolates of the S. intermedius group of species, which were collected and identified to the species level in 2011 to 2012 from dogs and cats by the Diagnostic Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, were tested by PCR for the presence of ICE6013. Four of these isolates were positive for ICE6013, and three of these produced detectable circular forms. Four ICE6013-negative isolates were made resistant to rifampin and streptomycin as needed and tested for conjugation with the mock wild-type S. aureus strain DAR6247 as the donor, but no transconjugants were obtained (Table 1). Altogether, these results indicate that ICE6013 diversity and host range are much greater than previously known.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that uninterrupted orf1 and orf2 are necessary for ICE6013 excision. ICE6013 is now the third family of integrative conjugative elements, after TnGBS and ICEA (15, 16), known to use a DDE Tpase as a recombinase and the first example to use the IS30 family of Tpases. While the prototypical IS30 element from E. coli carries a single ORF (36), the IS30-like Tpase from ICE6013 is encoded by two ORFs. A two-ORF structure for an IS30-like element, ISLxc4, has also been reported for the plant-inhabiting bacterium Leifsonia xyli, though it was not linked to an ICE (37). Our updated annotation of the IS30-like Tpase indicates that a fusion product of orf1 and orf2 has an N-terminal DNA-binding domain with two putative helix-turn-helix motifs (encoded by orf2) and a C-terminal catalytic domain with the DDE motif (encoded by orf1) (Fig. 2), which is a structural organization common for a Tpase (36). Three poly(A) tracts also occur in orf2 (13) (Fig. 1B). Besides the potential for programmed ribosomal frameshifting (38) by the 3′ poly(A)5 tract, the two 5′ poly(A)7 tracts occur directly after the initiation codon of orf2 and may add another layer of control over ICE6013 excision.

Three other ORFs of ICE6013 were shown to affect excision levels. Disruption of the putative lipoprotein gene (orf3) and the putative helicase processivity factor gene (orf14), which is homologous to the helP gene that is required for replication of ICEBs1 (39), decreased excision of ICE6013. On the other hand, disruption of orf4, which encodes a hypothetical protein with a GlmU domain, increased excision of ICE6013. This observation is consistent with a role for orf4 in the repression of ICE6013 excision. However, no homologs to DNA-binding proteins were found for Orf4 by reciprocal PSI-BLAST (not shown), and it is not clear how its GlmU domain would facilitate repressed excision. GlmU is a bifunctional enzyme with uridyltransferase and acetyltransferase activities that synthesizes a precursor (UDP-GlcNAc) of the S. aureus cell wall, capsule, and polysaccharide biofilm matrix (40). Further study is needed to determine the mechanism by which orf4 influences excision.

Excision of ICE6013 was not demonstrably affected by growth, temperature, pH, or DNA damage from UV exposure. Based on previous studies of S. aureus transcriptomes using an ICE6013-positive strain, UAMS-1, most of these conditions do not affect the expression of ICE6013 ORFs (41, 42). An exception is that pH 4 decreased expression of the Tpase (orf1 and orf2) and the putative relaxase (orf12) in UAMS-1 (41), but we observed a nonsignificant increase in excision during growth in pH 4 broth using the JE2 strain, which is of a different S. aureus background than UAMS-1. These observations may indicate that expression of the ICE6013 Tpase does not correlate directly with excision under these conditions or that strain-specific differences in excision may occur. Finally, as has been observed with ICE SXT from Vibrio cholerae (43), excision of ICE6013 does not depend upon recA.

ICE6013 excision was required for conjugation of the element. In addition, disruption of ICE6013 orf5 to orf8 and orf12 affected conjugation, as expected from previous studies showing that their homologs were required for the conjugation of ICEBs1 (39, 44–46). Our results provided no evidence for the mobilization of sequences flanking the element's integration site. Thus, the mechanism responsible for the strong signal of chromosomal recombination adjacent to the integration site of ICE6013 in S. aureus strain MRSA252 (20) requires further study. The frequencies of ICE6013 conjugation between some strains approached that of the well-studied conjugative plasmid pGO1 (47, 48). Since only 1 to 3 out of 1,000 wild-type donor cells have an excised form of ICE6013 that is necessary for conjugation, our results indicate that conjugative transfer of ICE6013 is highly efficient. By contrast, conjugations between certain strains of S. aureus and between S. aureus and the S. intermedius group were not observed after repeated attempts. Horizontal gene transfer between staphylococci in nature is subject to multiple barriers, including genetic barriers, such as restriction and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) systems, and ecological barriers, such as different eukaryotic hosts (49, 50).

In this regard, our finding of seven divergent subfamilies of ICE6013 in nine different species of staphylococci and in different eukaryotic hosts is notable. Conjugation of ICE6013 may explain some of its host range. For example, multiple divergent elements in the same strain and similar elements in different species may have resulted from conjugation or another means of horizontal gene transfer. The lack of antimicrobial resistance determinants or other ORFs that may have obvious selective value to an ICE6013 recipient is also notable. This situation is unlike that of S. aureus Tn5801, which is from the Tn916 family and is associated with the tet(M) tetracycline resistance gene (14), and may be more like that of TnGBS, where the factors that drive the successful spread of the element are unclear (15, 51). The presence of multiple ICE6013 subfamilies within S. aureus strains that are associated with food animals (e.g., ED98 and S0385) may also indicate both the lack of exclusion mechanisms that prevent the introduction of multiple copies of the element and the possibility that strains infecting food animals act as reservoirs for the element. Finally, our results unify genetic elements previously classified as a transposon, a plasmid, and different ICEs (26, 34, 35) within the ICE6013 family of integrative conjugative elements, which demonstrates the difficulty of classifying ICEs.

The prolonged extrachromosomal maintenance of ICE6013 in transconjugants strongly suggests that the element is able to replicate before integration, as was shown for ICEBs1, TnGBS, and SXT (44, 52, 53). We developed a TnSeq-like assay capable of identifying low-frequency chromosomal integrations of ICE6013 in transconjugants that were not detected in their genome assemblies. The larger number of different integration sites detected in the BHI-Ery-passaged transconjugant than in the BHA-Ery-passaged transconjugant is consistent with a less severe bottleneck of diversity from serial inoculation with broth than from axenic inoculation of single colonies on agar plates. Alternatively, the integration process could be influenced by planktonic versus surface growth, as has been shown for the conjugation process for S. aureus plasmids (47). By examining the 58 unique, unambiguous annotated integration sites in transconjugants, the integration site preference of ICE6013 was revealed. The element targets a 15-bp AT-rich palindromic consensus sequence, which surrounds the 3-bp target site that is duplicated upon integration. This sequence is shorter than the 24-bp palindromic consensus sequence preferred by IS30, and the T and A richness of the sequences to the left and right of the ICE6013 target site, respectively, is on the sides of the target site that are opposite to IS30 (19). We did not further analyze the frequency of different integration sites, since the frequency is conflated by the fitness effects and preference for different integration sites. Nonetheless, the sequences preferred by ICE6013 appear to be more conserved than the sequences upstream of σA-dependent promoters that are used as integration sites by the TnGBS ICEs and the various integration sites discerned for ICEA (17). Besides ICE6013 and IS30, IS903 also shows an integration site preference that is symmetric around its target site (54). In IS30 and IS903, these sequences have been studied for DNA structural characteristics, as potential binding sites for host proteins, and as recognition sites for the helix-turn-helix motifs of the Tpase (19, 54, 55).

In summary, these studies have provided the first experimental support for the hypothesis that ICE6013 excises by its IS30-like Tpase and have identified additional factors affecting excision. ICE6013 was shown to be a genuine conjugative element that transfers between strains of S. aureus. Integration of ICE6013 in transconjugants was also observed, which led to a better characterization of the element's integration site specificity. Finally, seven divergent subfamilies of ICE6013 from nine species of staphylococci were identified, which indicates that the element is an agent of horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Mariner-based transposon (Tn) mutants were obtained from the library constructed by Fey et al. (56). The Tn insertion site in each mutant was confirmed by PCR upon receipt of the mutants. E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with aeration and antibiotics when appropriate. Unless otherwise noted, S. aureus strains were grown in BHI to an OD600 of ∼0.6 or on agar (BHA) overnight at 37°C. The following antibiotics were used when appropriate: erythromycin (10 μg/ml), rifampin (10 μg/ml), streptomycin (1,000 μg/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml). Spontaneous rifampin and streptomycin mutants were isolated for use as recipients in filter-mating experiments.

Complementation of mutants.

To complement selected mutants, sequences containing putative promoter regions along with the open reading frame(s) were amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table S2 and cloned into the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid pMK4 (57).

UV exposure.

Bacteria were exposed to UV as described previously (58) with adjustments to growth conditions. Briefly, overnight cultures of strains JE2 (56) and RN4220 (67) were diluted in fresh BHI and grown to early exponential phase. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 15 ml 1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by vortexing. Five milliliters was aliquoted into sterile petri plates. Exposure was performed in a Stratalinker RS (Stratagene) at 25 J/m2 or 100 J/m2. A third aliquot was used as a negative control. After exposure, samples were mixed with 5 ml BHI and allowed to grow for 1 h at 37°C before dilution and plating for CFU counts. The remaining solution was pelleted and used to isolate genomic DNA.

Influence of pH on excision.

JE2 and RN4220 were exposed to pH 10 and pH 4 as described previously (41). In brief, overnight cultures were diluted in fresh BHI and grown to early exponential phase. The culture was then adjusted to pH 4 with 1 N HCl or to pH 10 with 1 N NaOH and incubated for 30 min, at which point 20 μl was plated for CFU counts and the remainder was used for isolating genomic DNA.

Filter mating.

Filter mating was performed as described previously (47) with the modifications noted below. Briefly, donor and recipient strains were grown separately overnight in BHI at 30°C and then diluted to an OD600 of ∼0.1. Growth was continued at the same temperature until an OD600 of ∼0.6 was obtained. Various dilutions were spread on agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics to determine CFU counts for each experiment. Equal numbers of donor and recipient cells (∼108 CFU/ml) were mixed and filtered through nitrocellulose membrane filters (diameter, 25 mm; pore size, 0.22 μm; Millipore). Filters were applied to BHA cell side up and incubated for 18 h. Cells were then suspended in 1 ml of 1% phosphate-buffered saline by vortexing. Transconjugants were selected by plating on BHA supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. For each biological replicate, negative controls were donor only, recipient only, and donor supernatant mixed with recipient. Individual plates of the donor and recipient were the controls for spontaneous resistance mutations, and the donor supernatant was a control for horizontal transfer mechanisms that do not require cell-cell contact. Separate experiments to specifically inhibit transduction with 100 mM sodium citrate or to inhibit transformation with 100 units per ml DNase I (59) did not prevent the conjugation of ICE6013. The conjugative plasmid pGO1 (48) was used as a positive control for conjugation. All transconjugant colonies from at least one technical replicate from each biological replicate were screened for the presence of ICE6013 with PCR (see Table S2).

PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen) after growth in standard conditions, unless otherwise noted. Outward-directed PCR to detect the circular form of excised ICE6013 was performed after normalization of the genomic DNA template to 100 ng using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific) for quantification. The primers used are listed in Table S2. This PCR was performed using GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega) with thermal cycler conditions of 95°C for 2 min followed by 25 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with a final extension of 2 min at 72°C. To test for excision of the IS30-like element itself, two primer pairs were used (Table S2). PCR for a putative circular form of the IS30-like element was performed as described for the circular form of ICE6013 but with 40 cycles to attempt to detect low-frequency circular forms. All other PCR experiments were performed with 30 cycles.

Quantitative PCR assay for ICE6013 excision.

For qPCR, the genomic DNA template was normalized to 6 ng using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) to quantify double-stranded DNA. Primers were designed to amplify a 136-bp sequence around the chromosomal integration site of ICE6013 in ST8-USA300 strain JE2, and reference gene primers were designed to amplify a 142-bp sequence within gyrB (Table S2). Optimal primer concentrations of 400 nM were chosen for both the integration site and the gyrB reactions after testing a gradient of primer concentrations. qPCRs used SYBR green qPCR Supermix reagents (Invitrogen) and were run on an iCycler IQ5 (Bio-Rad). An initial melting curve analysis was performed to ensure no off-target priming. A standard curve for the empty chromosomal integration site was created using strain RN4220, which represents 100% excision as it does not have ICE6013 and contains a single copy of JE2's integration site. Strain JE2, which has wild-type ICE6013 and is the parent strain of the Tn mutants studied here, was used to create a standard curve for gyrB. Both standard curves used 6 logs of chromosome mass ranging from 318 ng to 0.00318 ng, with mass estimated from the completely sequenced chromosome of ST8-USA300 strain TCH1516 (60). The R2 values for the standard curves were 0.934 and 0.998 for the integration site and gyrB reactions, respectively.

qPCR analysis used the method of Pfaffl (61) as has been used with data for other ICEs (43). In brief, the amplification efficiencies of the integration site and gyrB reactions were determined by the equation E = 10−1/m, where m is the slope of the linear regression from the standard curves. Efficiencies were 2.09 and 1.98 for the integration site and gyrB reactions, respectively. ICE6013 excision was calculated as (E integration site)ΔCT integration site/(E gyrB)ΔCT gyrB, where E integration site and E gyrB are the efficiencies for the integration site and gyrB reactions, respectively, and ΔCT integration site and ΔCT gyrB are the cycle threshold (CT) values of the control DNA minus the sample DNA for the integration site and gyrB reactions, respectively. Each excision measurement was based on results from at least three biological replicates. Each run of qPCR included the RN4220 100% excision control DNA and no-template controls.

Statistical comparisons of ICE6013 excision were performed relative to the wild-type strain JE2 under standard growth conditions (growth at 37°C in BHI to an OD600 of ∼0.6). The excision data were log-transformed, and the null hypothesis of equal means was tested with a two-tailed t test. Statistical significance was set at a P value of 0.05.

TnSeq-like assay for ICE6013 integrated and circular forms.

To attempt to capture integration of ICE6013 into a new host chromosome, transconjugants were serially passaged for 10 days in BHI-Ery (inoculation of 100 μl into 10 ml) or for 16 days on BHA-Ery (inoculation from single colony picks). The final serial passaged transconjugants were sequenced on a MiSeq or NextSeq instrument after NexteraXT library preparation (Illumina). Genome sequences were assembled de novo using CLC Genomics Workbench v7 (Qiagen) and probed for ICE6013 integration using BLASTn.

To enrich sequences for ICE6013 integrated and circular forms, a TnSeq-like assay was developed. The mock wild-type strain DAR6247 was used as a control with a known ICE6013 chromosomal integration site and a known excision frequency as determined by qPCR. Genomic DNA was extracted from the control strain and from the transconjugant passaged in BHI-Ery as before or from a lawn of growth from the transconjugant passaged on BHA-Ery. Genomic DNA was sonicated (Covaris M220) to 500 bp using standard factory settings, was end repaired using NEBNext End Repair and dA-Tailing Modules (NEB), and was ligated using NEBNext Quick Ligation (NEB) to the splinkerette adapters described by Barquist et al. (62). Adapter-ligated fragments were purified (Invitrogen PureLink) and PCR was performed to enrich for fragments with the left end of ICE6013. The PCR primers (Table S2) were designed according to Kozich et al. (63) to include a portion of the adapter sequence, a linker sequence, a pad sequence for tuning GC content, and Illumina dual-index and P5/P7 sequences. For PCR we used Kapa HiFi DNA polymerase (Kapa Biosystems) with thermal cycler conditions of 95°C for 30 s followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 67°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 60 s, with a final extension of 5 min at 68°C. PCR products were purified with 1× AMPure XP beads (Agencourt) and quantified by Qubit. The pooled library contained the three samples at 2.4 pM with 20% PhiX and was sequenced with a 500-cycle paired-end MiSeq reagent kit (Illumina) after modifying the Illumina sample sheet (63).

Reads were demultiplexed using MiSeq Reporter. Overlapping read pairs were merged, adapter trimmed, and stringently filtered for quality (Q30 base quality with no more than one ambiguous base and no shorter than 27 bp) using CLC Genomics Workbench. A shell script was written to pull reads with the 12-bp left end of ICE6013, which is a sequence that is not present in the genome assembly of the ICE6013-negative recipient RN4220RS, with up to an additional 50 bp. Reads with at least the 12-bp left end of ICE6013 and 15 bp of adjacent sequence that were represented ≥10 times were then classified as circular or integrated forms (see Table S3). Other strategies explored for processing reads produced qualitatively similar results. A BLASTn query of the integrated forms against the RN4220RS assembly, requiring a unique match with 100% identity, was used to pull 50 bp on each side of the integration site. This 100-bp sequence was then used to annotate the integration site based on a unique match with 100% identity to the reference genome of strain TCH1516 (60). PCR was used to verify the presence of the integrated form that was most frequent among the transconjugants. BLogo (64) was used with the 58 unique, unambiguous annotated integration sites (see Table S4) to detect significantly (P < 0.05; chi-square or Fisher's exact test) over- and underrepresented nucleotides.

ICE6013 sequence analysis.

ICE6013 elements from S. aureus and other staphylococcal species were identified by a BLASTn search of GenBank's NR and WGS databases. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) was calculated between pairs of ICE6013 sequences using JSpecies v1.2.1 (65) with default parameters, and results were clustered with the neighbor-joining algorithm using PAUP*4 (Sinauer Associates) after transformation to the distance (100 − mean reciprocal ANI)/100. To provide consistent annotation for comparisons of ICE6013 gene content and organization, ORFs were recalled for all sequences using Prodigal v1.2 (66). An updated annotation of ICE6013, along with the locations of primer sites for detecting circular forms and Tn insertion sites, is provided in Fig. 1.

Accession number(s).

The genome sequences of the mock wild-type donor, the recipient, and 32 transconjugants and the sequence reads from the TnSeq-like experiment were given accession number PRJNA360134 by the National Center for Biotechnology Information's BioProject database.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank BEI Resources, Paul Fey, and Ken Bayles for sharing the transposon insertion mutants, Richard O'Callaghan for sharing the pGO1 plasmid, and Lars Barquist and Matthew Mayho for their helpful discussions on the TnSeq-like assay.

This work was supported in part by U.S. NIH grant R01-GM080602 (to D.A.R.) and U.S. NIH grant P20-GM103646 and a Korean Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency grant (to K.S.S.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00629-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindsay JA. 2010. Genomic variation and evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Med Microbiol 300:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. 2010. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:3057–3071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Maiques E, Ubeda C, Selva L, Lasa I, Penades JR. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island DNA is packaged in particles composed of phage proteins. J Bacteriol 190:2434–2440. doi: 10.1128/JB.01349-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon BY, Park JY, Robinson DA, Thomas JC, Park YH, Thornton JA, Seo KS. 2016. Mobilization of genomic islands of Staphylococcus aureus by temperate bacteriophage. PLoS One 11:e0151409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharn CR, Tenover FC, Goering RV. 2013. Transduction of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements between strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5233–5238. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01058-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray MD, Boundy S, Archer GL. 2016. Transfer of the methicillin resistance genomic island among staphylococci by conjugation. Mol Microbiol 100:675–685. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy AJ, Loeffler A, Witney AA, Gould KA, Lloyd DH, Lindsay JA. 2014. Extensive horizontal gene transfer during Staphylococcus aureus co-colonization in vivo. Genome Biol Evol 6:2697–2708. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts AP, Chandler M, Courvalin P, Guédon G, Mullany P, Pembroke T, Berg DE. 2008. Revised nomenclature for transposable genetic elements. Plasmid 60:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guglielmini J, Quintais L, Garcillán-Barcia MP, de la Cruz F, Rocha EPC. 2011. The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet 7:e1002222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carraro N, Burrus V. 2014. Biology of three ICE families: SXT/R391, ICEBs1, and ICESt1/ICESt3. Microbiol Spectr 2:MDNA3-0008-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0008-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brochet M, Rusniok C, Couvé E, Dramsi S, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Glaser P. 2008. Shaping a bacterial genome by large chromosomal replacements, the evolutionary history of Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:15961–15966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803654105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Lian J. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth DS, Robinson DA. 2009. Integrative and sequence characteristics of a novel genetic element, ICE6013, in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 191:5964–5975. doi: 10.1128/JB.00352-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries LE, Hasman H, Rabadán SJ, Agersø Y. 2016. Sequence-based characterization of Tn5801-like genomic islands in tetracycline-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and other gram-positive bacteria from humans and animals. Front Microbiol 7:576. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brochet M, Da Cunha V, Couve E, Rusniok C, Trieu-Cuot P, Glaser P. 2009. Atypical association of DDE transposition with conjugation specifies a new family of mobile elements. Mol Microbiol 71:948–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dordet Frisoni E, Marenda MS, Sagné E, Nouvel LX, Guérillot R, Glaser P, Blanchard A, Tardy F, Sirand-Pugnet P, Baranowski E, Citti C. 2013. ICEA of Mycoplasma agalactiae: a new family of self-transmissible integrative elements that confers conjugative properties to the recipient strain. Mol Microbiol 89:1226–1239. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guérillot R, Siguier P, Gourbeyre E, Chandler M, Glaser P. 2014. The diversity of prokaryotic DDE transposases of the mutator superfamily, insertion specificity, and association with conjugation machineries. Genome Biol Evol 6:260–272. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olasz F, Farkas T, Kiss J, Arini A, Arber W. 1997. Terminal inverted repeats of insertion sequence IS30 serve as targets for transposition. J Bacteriol 179:7551–7558. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7551-7558.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olasz F, Kiss J, König P, Buzás Z, Stalder R, Arber W. 1998. Target specificity of insertion element IS30. Mol Microbiol 28:691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everitt RG, Didelot X, Batty EM, Miller RR, Knox K, Young BC, Wilson DJ. 2014. Mobile elements drive recombination hotspots in the core genome of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Commun 5:3956. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamrozy DM, Harris SR, Mohamed N, Peacock SJ, Tan CY, Parkhill J, Anderson AS, Holden MTG. 2016. Pan-genomic perspective on the evolution of the Staphylococcus aureus USA300 epidemic. Microb Genom 2:0.000058. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt DC, Holden MT, Tong SY, Castillo-Ramirez S, Clarke L, Quail MA, Currie BJ, Parkhill J, Bentley SD, Feil EJ, Giffard PM. 2011. A very early-branching Staphylococcus aureus lineage lacking the carotenoid pigment staphyloxanthin. Genome Biol Evol 3:881–895. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auchtung JM, Lee CA, Monson RE, Lehman AP, Grossman AD. 2005. Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12554–12559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505835102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flannagan SE, Clewell DB. 2002. Identification and characterization of genes encoding sex pheromone cAM373 activity in Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 44:803–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowder BV, Guinane CM, Zakour NLB, Weinert LA, Conway-Morris A, Cartwright RA, Fitzgerald JR. 2009. Recent human-to-poultry host jump, adaptation, and pandemic spread of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:19545–19550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schijffelen MJ, Boel CE, van Strijp JA, Fluit AC. 2010. Whole genome analysis of a livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 isolate from a case of human endocarditis. BMC Genomics 11:376. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roach DJ, Burton JN, Lee C, Stackhouse B, Butler-Wu SM, Cookson BT, Shendure J, Salipante SJ. 2015. A year of infection in the intensive care unit: prospective whole genome sequencing of bacterial clinical isolates reveals cryptic transmissions and novel microbiota. PLoS Genet 11:e1005413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakour NLB, Beatson SA, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR. 2012. Comparative genomics of the Staphylococcus intermedius group of animal pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:44. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moodley A, Riley MC, Kania SA, Guardabassi L. 2013. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strain E140, an ST71 European-associated methicillin-resistant isolate. Genome Announc 1:e0020712. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misic AM, Cain CL, Morris DO, Rankin SC, Beiting DP. 2015. Complete genome sequence and methylome of Staphylococcus schleiferi, an important cause of skin and ear infections in veterinary medicine. Genome Announc 3:e01011-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01011-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki T, Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Matsuo M, Lu YJ, Tanaka Y, Hiramatsu K. 2015. Complete genome sequence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus schleiferi strain TSCC54 of canine origin. Genome Announc 3:e01268-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01268-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Rubaye AAK, Couger MB, Ojha S, Pummill JF, Koon JA, Wideman RF, Rhoads DD. 2015. Genome analysis of Staphylococcus agnetis, an agent of lameness in broiler chickens. PLoS One 10:e0143336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nováková D, Pantùček R, Hubálek Z, Falsen E, Busse H, Schumann P, Sedláček I. 2010. Staphylococcus microti sp. nov., isolated from the common vole (Microtus arvalis). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:566–573. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.011429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han X, Ito T, Takeuchi F, Ma XX, Takasu M, Uehara Y, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H, Hiramatsu K. 2009. Identification of a novel variant of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, type II. 5, and its truncated form by insertion of putative conjugative transposon Tn6012 Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2616–2619. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00772-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shearer JE, Wireman J, Hostetler J, Forberger H, Borman J, Gill J, Bayles K, Nicholson A, O'Brien F, Jensen SO, Firth N, Skurray RA, Summers AO. 2011. Major families of multiresistant plasmids from geographically and epidemiologically diverse staphylococci. G3 (Bethesda) 1:581–591. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siguier P, Gourbeyre E, Varani A, Ton-Hoang B, Chandler M. 2015. Everyman's guide to bacterial insertion sequences. Microbiol Spectr 3:MDNA3-0030-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0030-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zerillo MM, Van Sluys MA, Camargo LE, Monteiro-Vitorello CB. 2008. Characterization of new IS elements and studies of their dispersion in two subspecies of Leifsonia xyli. BMC Microbiol 8:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsay JP, Ronson CW. 2015. Silencing quorum sensing and ICE mobility through antiactivation and ribosomal frameshifting. Mob Genet Elements 5:103–108. doi: 10.1080/2159256X.2015.1107177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas J, Lee CA, Grossman AD. 2013. A conserved helicase processivity factor is needed for conjugation and replication of an integrative and conjugative element. PLoS Genet 9:e1003198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton E, Gawande PV, Yakandawala N, LoVetri K, Zhanel GG, Romeo T, Friesen AD, Madhyastha S. 2006. Antibiofilm activity of GlmU enzyme inhibitors against catheter-associated uropathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1835–1840. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1835-1840.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson KL, Roux CM, Olson MW, Luong TT, Lee CY, Olson R, Dunman PM. 2010. Characterizing the effects of inorganic acid and alkaline shock on the Staphylococcus aureus transcriptome and messenger RNA turnover. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 60:208–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson KL, Roberts C, Disz T, Vonstein V, Hwang K, Overbeek R, Olson PD, Projan SJ, Dunman PM. 2006. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J Bacteriol 188:6739–6756. doi: 10.1128/JB.00609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burrus V, Waldor MK. 2003. Control of SXT integration and excision. J Bacteriol 185:5045–5054. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5045-5054.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee CA, Babic A, Grossman AD. 2010. Autonomous plasmid-like replication of a conjugative transposon. Mol Microbiol 75:268–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06985.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeWitt T, Grossman AD. 2014. The bifunctional cell wall hydrolase CwlT is needed for conjugation of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 in Bacillus subtilis and B. anthracis. J Bacteriol 196:1588–1596. doi: 10.1128/JB.00012-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee CA, Grossman AD. 2007. Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and DNA relaxase required for conjugation of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 189:7254–7261. doi: 10.1128/JB.00932-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savage VJ, Chopra I, O'Neill AJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms promote horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1968–1970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02008-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas WD, Archer GL. 1989. Identification and cloning of the conjugative transfer region of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pGO1. J Bacteriol 171:684–691. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.684-691.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindsay JA. 2014. Staphylococcus aureus genomics and the impact of horizontal gene transfer. Int J Med Microbiol 304:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Popa O, Dagan T. 2011. Trends and barriers to lateral gene transfer in prokaryotes. Curr Opin Microbiol 14:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flechard M, Gilot P. 2014. Physiological impact of transposable elements encoding DDE transposases in the environmental adaptation of Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbiology 160:1298–1315. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.077628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guérillot R, Da Cunha V, Sauvage E, Bouchier C, Glaser P. 2013. Modular evolution of TnGBSs, a new family of integrative and conjugative elements associating insertion sequence transposition, plasmid replication, and conjugation for their spreading. J Bacteriol 195:1979–1990. doi: 10.1128/JB.01745-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carraro N, Poulin D, Burrus V. 2015. Replication and active partition of integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) of the SXT/R391 family: the line between ICEs and conjugative plasmids is getting thinner. PLoS Genet 11:e1005298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu WY, Derbyshire KM. 1998. Target choice and orientation preference of the insertion sequence IS903. J Bacteriol 180:3039–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagy Z, Szabó M, Chandler M, Olasz F. 2004. Analysis of the N-terminal DNA binding domain of the IS30 transposase. Mol Microbiol 54:478–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fey PD, Endres JL, Yajjala VK, Widhelm TJ, Boissy RJ, Bose JL, Bayles KW. 2013. A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. mBio 4:e00537-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan MA, Yasbin RE, Young FE. 1984. New shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli which allow rapid detection of inserted fragments. Gene 29:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Almagro-Moreno S, Napolitano MG, Boyd EF. 2010. Excision dynamics of Vibrio pathogenicity island-2 from Vibrio cholerae: role of a recombination directionality factor VefA. BMC Microbiol 10:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stout VG, Iandolo JJ. 1990. Chromosomal gene transfer during conjugation by Staphylococcus aureus is mediated by transposon-facilitated mobilization. J Bacteriol 172:6148–6150. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6148-6150.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Highlander SK, Hultén KG, Qin X, Jiang H, Yerrapragada S, Mason EO Jr, Shang Y, Williams TM, Fortunov RM, Liu Y, Igboeli O, Petrosino J, Tirumalai M, Uzman A, Fox GE, Cardenas AM, Muzny DM, Hemphill L, Ding Y, Dugan S, Blyth PR, Buhay CJ, Dinh HH, Hawes AC, Holder M, Kovar CL, Lee SL, Liu W, Nazareth LV, Wang Q, Zhou J, Kaplan SL, Weinstock GM. 2007. Subtle genetic changes enhance virulence of methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol 7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barquist L, Mayho M, Cummins C, Cain AK, Boinett CJ, Page AJ, Langridge GC, Quail MA, Keane JA, Parkhill J. 2016. The TraDIS toolkit: sequencing and analysis for dense transposon mutant libraries. Bioinformatics 32:1109–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. 2013. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li W, Yang B, Liang S, Wang Y, Whiteley C, Cao Y, Wang X. 2008. BLogo: A tool for visualization of bias in biological sequences. Bioinformatics 24:2254–2255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. 2009. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Novick R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gill SR, Fouts DE, Archer GL, Mongodin EF, Deboy RT, Ravel J, Paulsen IT, Kolonay JF, Brinkac L, Beanan M, Dodson RJ, Daugherty SC, Madupu R, Angiuoli SV, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Vamathevan J, Khouri H, Utterback T, Lee C, Dimitrov G, Jiang L, Qin H, Weidman J, Tran K, Kang K, Hance IR, Nelson KE, Fraser CM. 2005. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J Bacteriol 187:2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.