Chen et al. show that USP21 is a deubiquitinating enzyme for the adaptor protein STING and that it negatively regulates the DNA virus–induced production of type I interferons. HSV-1 infection recruited USP21 to STING at a late stage by p38-mediated phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538.

Abstract

Stimulator of IFN genes (STING) is a central adaptor protein that mediates the innate immune responses to DNA virus infection. Although ubiquitination is essential for STING function, how the ubiquitination/deubiquitination system is regulated by virus infection to control STING activity remains unknown. In this study, we found that USP21 is an important deubiquitinating enzyme for STING and that it negatively regulates the DNA virus–induced production of type I interferons by hydrolyzing K27/63-linked polyubiquitin chain on STING. HSV-1 infection recruited USP21 to STING at late stage by p38-mediated phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538. Inhibition of p38 MAPK enhanced the production of IFNs in response to virus infection and protected mice from lethal HSV-1 infection. Thus, our study reveals a critical role of p38-mediated USP21 phosphorylation in regulating STING-mediated antiviral functions and identifies p38-USP21 axis as an important pathway that DNA virus adopts to avoid innate immunity responses.

Introduction

The innate immune system is the first line of defense against pathogen infection. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors, RIG-I–like receptors, NOD-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, and DNA sensors (Akira et al., 2006). Upon virus infection, viral nucleic acids trigger the activation of transcription factors, including the IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF3) and NF-κB signaling pathways, and induce the expression of type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines, which are essential to eradicate infection (Ma and Damania, 2016). Precise control of inflammatory responses is crucial to maintain immune homeostasis.

Host cells express cytosolic sensors that sense and recognize exogenous viral nucleic acids (Wu and Chen, 2014). Many DNA sensors have been identified, such as DAI, IFI16, DDX41, and cGAS (Takaoka et al., 2007; Unterholzner et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Ablasser et al., 2013). Once sensing exogenous viral DNA, these sensors trigger signaling pathways and induce the expression of type I IFN through the adaptor protein stimulator of IFN genes (STING; also referred to as MITA, MPYS, TMEM173, or ERIS). Emerging evidence indicate that STING is a central player in DNA virus–induced IFN activation (Jin et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2009). DNA virus infections promote trafficking of STING from the ER to perinuclear microsome, recruit TBK1 and IRF3 to STING, and induce the production of type I IFN (Saitoh et al., 2009). STING-deficient cells exhibit profound defects in the production of IFNβ and other proinflammatory cytokines stimulated by DNA virus (Ishikawa et al., 2009). However, the precise and dynamic regulation of STING during DNA virus infection remains to be elucidated.

The function of STING is tightly controlled by posttranslational modification, such as ubiquitination and phosphorylation (Shu and Wang, 2014; Liu et al., 2015). Protein ubiquitination is a reversible process by which ubiquitin is covalently conjugated to proteins (Welchman et al., 2005). Ubiquitin can form polyubiquitin chains containing different branching linkages that perform different biological functions in protein trafficking, transcriptional regulation, and immune signaling (Mukhopadhyay and Riezman, 2007; Bhoj and Chen, 2009; Nishiyama et al., 2016). The polyubiquitination of STING plays an essential role in DNA virus–induced IRF3 activation and IFNβ production (Zhong et al., 2009; Tsuchida et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). For example, E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF5-mediated K48 polyubiquitination negatively regulates STING function by targeting it for degradation (Zhong et al., 2009). K11-linked polyubiquitination by RNF26 E3 ligase stabilizes STING by competing with RNF5 (Qin et al., 2014). K63/K27 polyubiquitination of STING mediated by E3 ligase TRIM32, TRIM56, or AMFR positively regulates DNA virus–triggered signaling and type I IFN expression (Tsuchida et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Ubiquitination is a reversible process, and the removal of ubiquitin is catalyzed by a large group of proteases generically called deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs; Amerik and Hochstrasser, 2004). Recent studies indicates that recruitment of EIF3S5 by iRhom2 or recruitment of USP20 by USP18 stabilizes and positively regulates STING function by removing K48-linked polyubiquitin chains (Luo et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). However, the mechanism that removes K63, K27, or other types of linked polyubiquitination to negatively regulate STING-mediated signaling remains unclear.

USP21 is a nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling deubiquitinase that can deubiquitinase proteins such as GATA3 and Gli (Zhang et al., 2013; Heride et al., 2016). Deficiency of USP21 in mice results in spontaneous immune activation and splenomegaly (Fan et al., 2014). Moreover, USP21 is a deubiquitinases, which negatively regulates anti-RNA virus infections and TNF-induced NF-κB signal pathway by targeting RIG-I and RIP-1 (Xu et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2014). In this study, we identified USP21 as a negative regulator of the DNA virus–targeted innate immune responses by removing the polyubiquitination chain from STING. Prolonged DNA virus stimulation activates p38, which consequently phosphorylates USP21 at Ser538. The phosphorylated USP21 in turn binds to STING and hydrolyzes K27/K63-linked polyubiquitination on STING. Deubiquitination of STING blocks the formation of complex of STING, TBK1, and IRF3 and inactivates type I IFN signaling. Our study uncovers a critical role of deubiquitination in the regulation of innate immune responses mediated by the adaptor STING.

Results

USP21 negatively regulates STING-induced IFN signaling

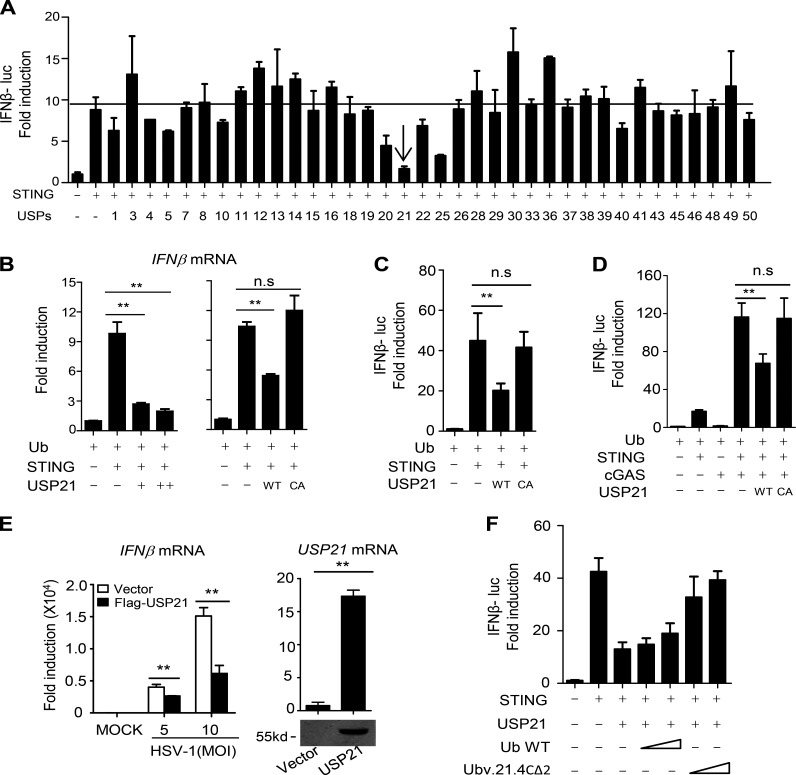

To identify the DUBs that are involved in STING deubiquitination, we screened a library of mammalian expression vectors that encode 36 DUBs by measuring STING-induced IFNβ promoter-driven luciferase activity. We found that USP21 and USP25, but no other deubiquitinases, significantly inhibited STING-induced IFNβ reporter activity (Fig. 1 A). However, unlike USP21, we did not detect the binding of USP25 to STING (Fig. 6 B). Therefore, we focused on investigating the role of USP21 in regulating STING's function.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of USP21 negatively regulates STING-induced IFN signaling. (A) STING-HA was cotransfected with the indicated USPs or control vectors, along with an IFNβ luciferase reporter, into 293T cells for 24 h. IFNβ luciferase activity was measured and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. (B) STING-HA was cotransfected with USP21 WT or USP21 WT/CA for 30 h, and IFNβ mRNA levels were measured by qPCR. (C and D) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T for 30 h, and IFNβ luciferase activity was measured. (E) THP-1 cells stably expressing Flag vector or Flag USP21 WT (THP-1) were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 5 or 10, respectively) for 8 h. IFNβ mRNA was measured by qPCR. USP21 protein was measured by Western blotting. (F) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T for 30 h, and IFNβ luciferase activity was measured. Error bars indicate mean ± SD in duplicate or triplicate experiments. Data from A is screening data from one experiment. Data are representative of two (E) or at least three (B–D and F) independent experiments. **, P < 0.01, two-tailed paired Student’s t test; NS, P > 0.05.

We found that WT, but not deubiquitinase-deficient (C221A) USP21, blocked STING-induced IFNβ mRNA levels and IFNβ luciferase activity (Fig. 1, B and C), suggesting that USP21 deubiquitinase activity is required for its negative effects on STING activity. cGAS is an upstream DNA sensor of STING (Sun et al., 2013). Our data showed that USP21 also inhibited cGAS-induced STING-IFNβ activation in a catalytic activity-dependent manner (Fig. 1 D). Stable expression of USP21 in THP-1 cells markedly suppressed gene expression induced by HSV-1 infection (Fig. 1 E). Overexpression of Ubv.21.4CΔ2, a USP21 inhibitor protein that has been shown to be able to inhibit USP21 activity (Ernst et al., 2013), efficiently blocked the effects of USP21 on STING (Fig. 1 F).

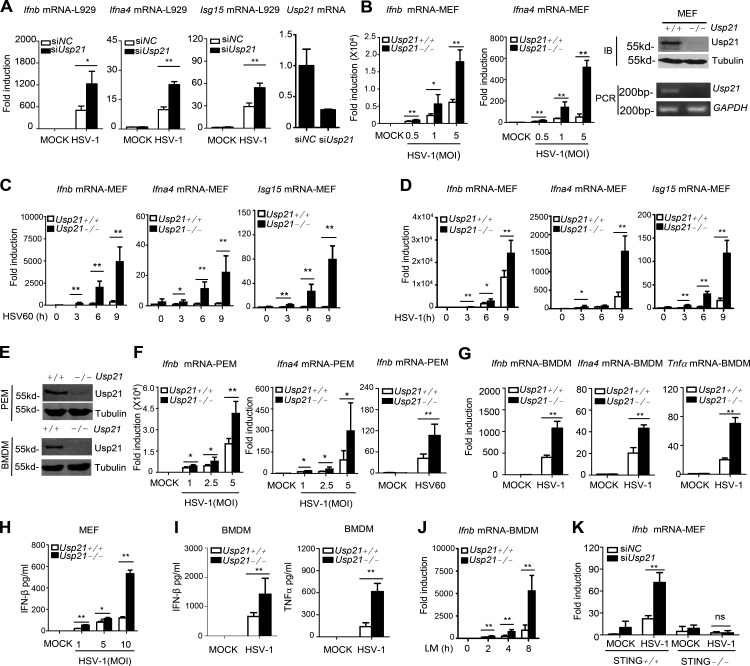

We further examined whether USP21 affects expression of downstream genes induced by HSV-1, a DNA virus that efficiently activates STING. We found that knockdown of Usp21 in mouse fibroblast L929 cells significantly enhanced the expression of Ifnb, Ifna4, and Isg15 (Fig. 2 A). Consistently, the induction of IRF3-responsive genes (Ifnb, Ifna4, or Isg15) was drastically elevated in USP21-deficient (Usp21−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in response to HSV-1 and HSV60mer mimics at the indicated time (Fig. 2, B–D). Usp21 ablation also drastically enhanced the expression of Ifnb, Ifna4, or TNF mRNA in primary PEMs (peritoneal macrophages; Fig. 2, E and F) or BMDMs (BM-derived macrophages; Fig. 2 G). Consistently, Usp21 deficiency resulted in production of more IFNβ and TNF in MEFs and BMDMs in response to HSV-1 infection (Fig. 2, H and I).

Figure 2.

USP21 deficit enhances STING-induced IFN signaling. (A) L929 cells were transfected with control siRNA (siNC) and or siRNA against Usp21 (siUsp21). 48 h later, the transfected cells were counted and infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) for 6 h. Ifnb, Ifna4, and Isg15 mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (B) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.5, 1, and 5) for 6 h. Ifnb and Ifna4 mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were examined by RT-PCR or Western blotting. (C and D) WT or Usp21−/−MEFs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) or transfected with Mock or HSV60mer. Ifnb, Ifna4, and Isg15 mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (E) WT or Usp21−/− PEMs and BMDMs were examined by Western blotting. (F) WT or Usp21−/− PEMs (isolated from WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice) were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1, 2.5, and 5) for 6 h or transfected with an HSV60mer. Ifnb and Ifna4 mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (G) WT or Usp21−/− BMDMs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) for 6 h, and induction of Ifnb, Ifna4, and TNFa mRNAs was measured by qPCR. (H) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1, 5, and 10) for 12 h, and the supernatants were collected and assayed for IFNβ production by ELISA. (I) WT or Usp21−/− BMDMs (isolated from WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice) were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) for 12 h, and the supernatants were collected and assayed for IFNβ and TNF production by ELISA. (J) WT or Usp21−/− BMDMs were infected with L. monocytogenes (MOI = 10) for indicated times, and induction of Ifnb mRNAs was measured by qPCR. (K) WT or Sting−/− cells were transfected with siNC and siUsp21 for 48 h, and equal numbers of cells were counted and infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.5) for 4 h. Ifnb mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. Error bars indicate mean ± SD in triplicate experiments. Usp21 KO cells identify data are from one experiment. Other data are representative of three (A–K) independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed paired Student’s t test).

Previous study indicated that Listeria monocytogenes infection can also activate STING pathway (Archer et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). We thus examined whether USP21 is involved in the regulation of L. monocytogenes–induced gene expression. Our data showed that L. monocytogenes–induced Ifnb expression was drastically elevated in Usp21−/− BMDMs (Fig. 2 J).

We next examined whether the effect of USP21 on the HSV1-1–induced type I IFN signaling is dependent on STING. To this end, we depleted Usp21 in Sting−/− MEFs, and then examined the expression of Ifnb induced by HSV-1. Our data showed that Usp21 knockdown significantly enhanced Ifnb expression in WT but not in Sting−/− MEFs (Fig. 2 K). Collectively, our data indicate that USP21 is a negative regulator of STING-mediated cytokine expression in response to DNA virus.

USP21 negatively regulates host defense against DNA virus

As USP21 is involved in DNA virus–triggered IFNβ induction, we examined its roles in antiviral responses at the cellular level. We found that Usp21 knockdown in L929 cells ameliorated pathological changes and reduced HSV-1 replication (Fig. 3 A). The HSV-1 genomic DNA copy number was also significantly reduced in Usp21−/− MEFs and PEMs after HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3, B and C). We also examined the effect of USP21 on another DNA virus Adenovirus-EGFP (Adv-EGFP) replication. Our data showed that Usp21−/− MEFs were more resistant to Adv-EGFP infection and replication than WT MEFs (Fig. 3 D). These data together indicate that USP21 negatively regulates anti–DNA virus responses at the cellular level.

Figure 3.

USP21 negatively regulates host defense against DNA virus. (A) L929 cells were transfected with siNC and siUsp21. 48 h later, the transfected cells were counted and infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). Cell morphology was visualized by microscopy at 8 h. 24 h later, genomic DNA was extracted and HSV-1 relative genome copy ratio was measured by qPCR. Bars, 200 µm. (B and C) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs or PEMs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.5 and 1) for 24 h, after which genomic DNA was extracted, and the relative HSV genome copy ratio was measured by qPCR. (D) Adv-EGFP replication in WT or Usp21−/− MEFs after infection for 36 h was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Bars, 200 µm. (E) DNA-PAGE images of intercrossed Usp21+/− Lyz2+/− mice. (F and G) WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (n = 7 each) were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 1 × 107 PFU per mouse, and survival was monitored for 8 d. Body weight (F) and survival rate (G) were tested. (H) WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (n = 3 each) were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 5 × 106 PFU per mouse. Brains were harvested 5 d after infection and measured by qPCR. HSV-1 genomic DNA was assessed. (I) WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (n = 3 each) were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 2 × 107 PFU per mouse. Brains were harvested after 2 d for immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis using anti–HSV-1 antibodies. Tissue sections were visualized by microscopy. Percentages of HSV-1–infected cells were quantified. Positive cells were counted from 10 fields per mouse (n = 3). Bars, 33 μm. (J–L) WT or Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (n = 5 each) were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 1 × 107 PFU per mouse. Sera were collected at 6 h, and the concentrations of serum cytokines, including IFNβ (J), IL-6 (K), and TNF (L) were measured by ELISA. Error bars indicate mean ± SD in duplicate or triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed paired Student’s t test or Kaplan Meier survival analysis). Data are representative of two (D–L) or at least three (A–C) independent experiments.

We next aimed to investigate the role of USP21 in host defense against DNA virus infection in vivo. Because Usp21 knockout mice showed spontaneous immune activation (Fan et al., 2014), we specifically deleted Usp21 in myeloid cells by crossing Usp21fl/fl mice with mice expressing the lysozyme promoter-driven Cre recombinase gene (Lyz2-cre; Fig. 3 E). These myeloid cell–specific Usp21-deficient mice are hereafter referred to as Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre. Usp21fl/fl mice that do not express Cre recombinase (Usp21fl/fl) were used as controls and are referred to as Usp21-WT. Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre or WT mice were intravenously infected with HSV-1, and their survival rate and body weight were monitored. We found that WT mice lost body weight much faster than Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice after HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3 F). Moreover, most of the WT mice died within 8 d, whereas all the infected Usp21fl/flLyz2-cre mice remained alive until 8 d after HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3 G), suggesting that Usp21fl/flLyz2-cre mice were more resistant to HSV-1 infection.

HSV-1 is a neurotropic virus and the leading cause of sporadic viral encephalitis. We therefore measured HSV-1 genomic DNA copy numbers in the brains extracted from WT and Usp21fl/flLyz2-cre mice on day 5 after infection. Our data showed that HSV-1 genomic DNA copy number was significantly reduced in Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (Fig. 3 H). Moreover, immunostaining indicates that HSV-1 virions were significantly reduced in the brains of Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice (Fig. 3 I). Notably, Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre mice produced significantly higher concentrations of IFNβ, IL-6, and TNF in serum upon HSV-1 infection compared with infected control mice (Fig. 3, J–L). These data also suggest that the increased cytokines in blood may be involved in the elimination of HSV-1 in vivo. Taken together, these data indicate that USP21 is a negative regulator of host defense against HSV-1 infection in vivo.

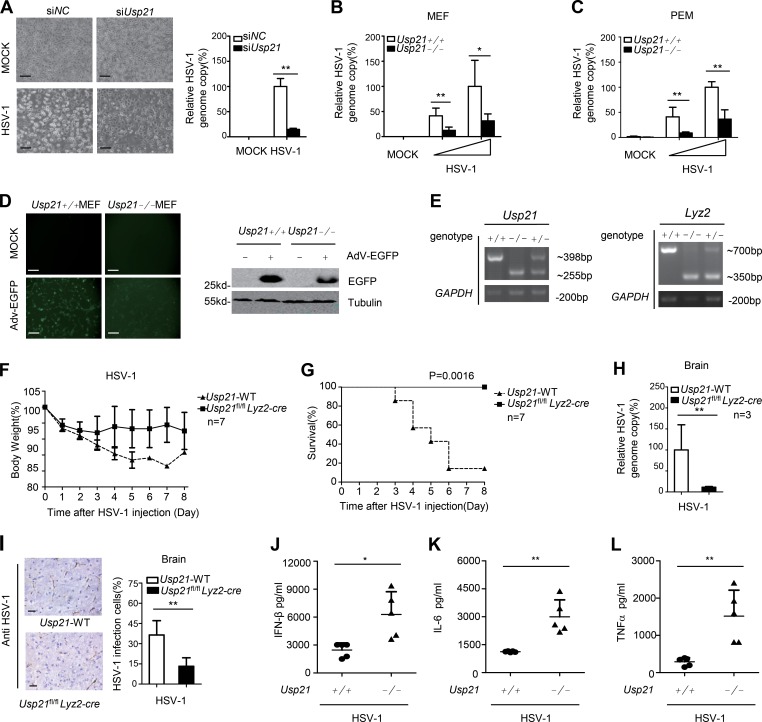

USP21 deficiency enhances intracellular IRF3 activation

STING-mediated host defense against virus infection is mainly through the activation of IRF3 signaling pathways (Zhong et al., 2008). HSV-1 infection significantly induced the phosphorylation and dimerization of IRF3, which mediates the expression of various cytokines (Ishikawa et al., 2009). Our data showed that the phosphorylation of IRF3 was increased in Usp21−/− MEFs, BMDMs, and PEMs upon stimulation with HSV-1 at the indicated time (Fig. 4, A–C). The effect of USP21 deficiency in MEFs could be rescued by USP21WT, but not the USP21C221A mutant (Fig. 4 D). Consistently, overexpression of USP21WT, but not the USP21C221A mutant, inhibited STING-induced IRF3 dimerization and phosphorylation (Fig. 4 E). These data suggest USP21 is a negative regulator of IRF3 activation.

Figure 4.

USP21 deficiency enhances intracellular IRF3 activation. (A and B) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs or BMDMs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 2). Cells were collected at the indicated time (0, 2, 4, and 8 h). All proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) WT or Usp21−/− PEMs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). Cells were collected at the indicated time (0, 4, and 8 h). The indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (D) Usp21−/−MEFs were transfected with Myc-USP21 WT/CA using Lipofectamine 3000; 24 h later, HSV-1 was added to the cells for 6 h. All proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) STING-Flag was cotransfected with HA-USP21 WT or CA and ubiquitin into 293T cells for 36 h. IRF3 dimers were separated via native PAGE. The indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. (F) STING-Flag was cotransfected with HA-USP21 WT or CA and Myc-TBK1 in combination with ubiquitin into 293T cells for 36 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads. All proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (G) Flag-IRF3 was cotransfected with HA-USP21 WT and STING-HA in combination with Ubiquitin into 293T cells for 36 h; the cells were then stimulated with HSV-1 (MOI = 2) for 4 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads. All proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (H) STING-Flag were cotransfected with HA-USP21 WT or CA mutant and STING-HA into 293T for 36 h. STING-Flag was immunoprecipitated using M2 beads. The bound STING-HA was analyzed by Western blotting. (I) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) or left uninfected for the indicated time. Co-IP and immunoblot analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. USP21 deficiency enhanced the HSV-1–induced recruitment of TBK1 and IRF3 to STING. (J) HeLa cells were transfected with STING-HA in combination with an empty vector or Flag-USP21, followed by stimulation with HSV-1 (MOI = 2) for the indicated amounts of time. USP21 blocks STING localization to the perinuclear region. Bar, 25 µm. Data are representative of two (D–J) or at least three (A–C) independent experiments.

As the binding of IRF3 and TBK1 to STING is essential for STING-mediated IRF3 activation, we examined whether USP21 affects the binding of STING to IRF3 and TBK1. Our data from coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiments indicated that USP21WT, but not USP21C221A, markedly reduced the binding of STING to TBK1 (Fig. 4 F). Ectopic expression of USP21 blocked the interaction between STING and IRF3 (Fig. 4 G) and significantly reduced STING multimerization (Fig. 4 H). Deficiency of Usp21 in MEFs significantly enhanced the endogenous binding of STING to IRF3 and TBK1 upon HSV-1 infection (Fig. 4 I). It has been shown that multimerization and trafficking from ER to a perinuclear Golgi location and endoplasmic-associated microsomes is essential to STING activation (Saitoh et al., 2009). Our data showed that overexpression of USP21 blocked translocation of STING from ER to a perinuclear microsome upon HSV-1 infection (Fig. 4 J). Collectively, these data indicate that USP21 is a negative regulator of STING-mediated IRF3 activation.

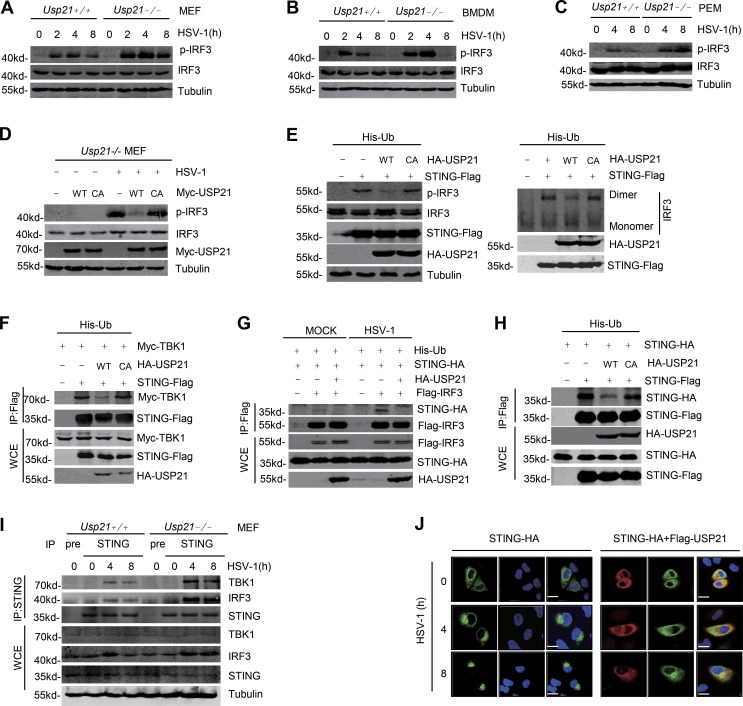

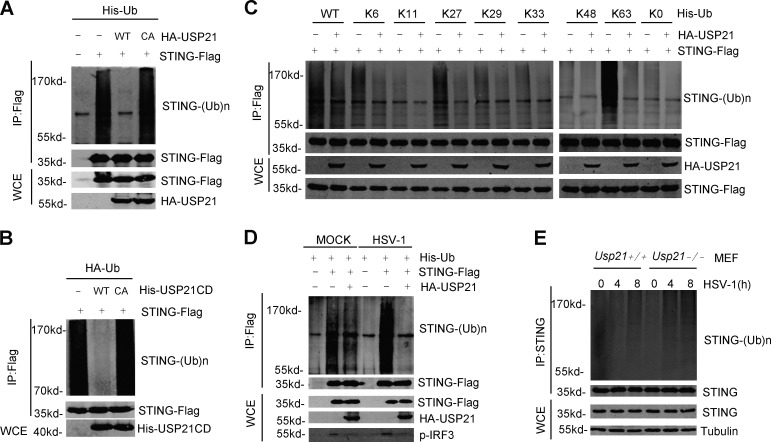

USP21 deubiquitinates K27/63 linked polyubiquitination of STING

We next examined whether USP21 affects the ubiquitination of STING. Our data showed that overexpression of USP21-WT, but not USP21-CA, greatly attenuated STING ubiquitination (Fig. 5 A). These results were confirmed by in vitro deubiquitination assay (Fig. 5 B). It is reported that K27/K63-linked polyubiquitination is crucial for STING activation (Tsuchida et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). We used ubiquitin mutants in which all lysines, except for those indicated, were mutated to arginines to dissect the polyubiquitin chain linkages present on STING. Our data indicate that USP21 strongly hydrolyzed K27- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, which are essential for STING-mediated IRF3 activation (Fig. 5 C). Moreover, overexpression of USP21 also inhibited the HSV-1–induced STING ubiquitination (Fig. 5 D). We also determined the role of USP21 in STING ubiquitination under more physiological conditions using Usp21−/−MEF cells. We found that the ubiquitination of endogenous STING was greatly enhanced in Usp21−/−MEF cells upon HSV-1 infection in comparison with WT-MEF cells (Fig. 5 E). Together, these data indicate that USP21 is a physiological deubiquitinase of STING.

Figure 5.

USP21 deubiquitinates STING. (A) STING-Flag was transfected into 293T cells in combination with HA-USP21WT/ CA and His-ubiquitin. At 30 h after transfection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads. A denaturation assay was employed to test ubiquitination. (B) USP21 hydrolysis of ubiquitin chains conjugated to STING was analyzed using an in vitro deubiquitination assay. (C) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. The ubiquitination of STING was analyzed using ubiquitination assay under denaturing condition. (D) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. After 24 h, cells were stimulated with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) for 6 h. The ubiquitination of STING was analyzed using ubiquitination assay under denaturing condition. (E) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were infected with or without HSV-1 for the indicated amounts of time, and cell lysates were subjected to denaturing immunoprecipitation with an anti-STING antibody or normal IgG, and then analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Data from A–E are representative of at least two independent experiments.

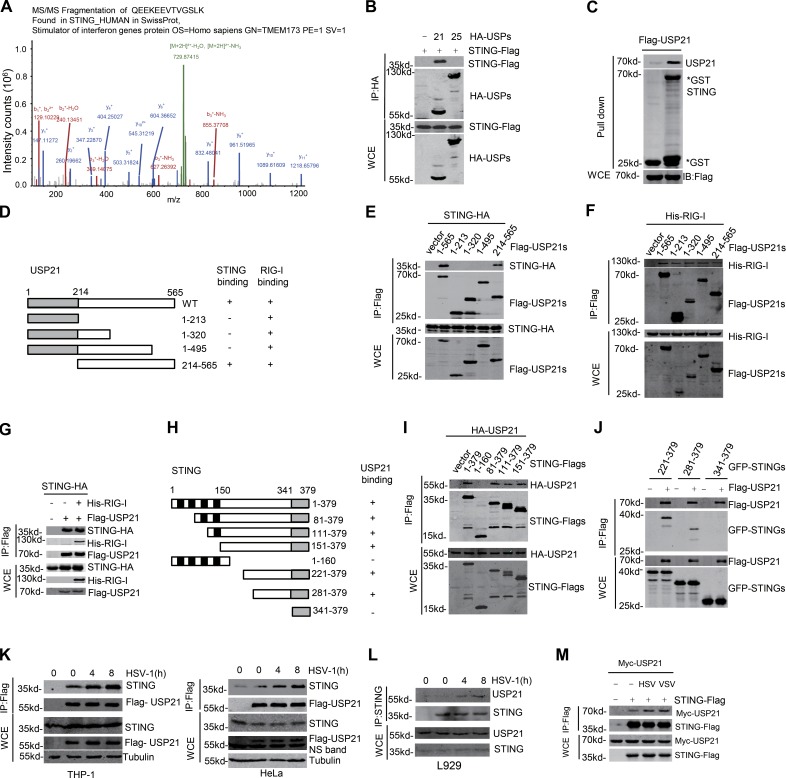

USP21 is a binding partner of STING

We next examined whether USP21 could bind to STING. Our data showed that STING could be detected in the USP21 complex purified from HSV-1–stimulated cells as revealed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 6 A and Table S1), suggesting that STING is a binding partner of USP21. Consistently, we found that the exogenous USP21, but not USP25, efficiently bound to the exogenous STING (Fig. 6 B). Furthermore, bacterial purified GST-STING could bind to the USP21 purified from HEK293T cells (Fig. 6 C). Using a series of truncation mutants, we found that the C-terminal region of USP21 (495–565 aa) mediated its association with STING (Fig. 6, D and E). Previous study indicated that USP21 can also bind RIG-I to regulate SeV infection (Fan et al., 2014). Our data showed that USP21 bound to RIG-I via multiple regions, which were different from the binding regions to STING (Fig. 6 F). Consistently, expression of RIG-I had little effect on interaction between USP21 and STING (Fig. 6 G). However, the central region of STING (221–341 aa) was required for its association with USP21 (Fig. 6, H–J). These data together indicate that USP21 is a binding partner of STING.

Figure 6.

USP21 binds STING. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-USP21 for 24 h. The transfected cells were stimulated with HSV-1 (MOI = 10) for 8 h. Then Flag-USP21 was immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and the binding proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry. (B) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using HA beads, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) The interaction between USP21 and STING was assessed using a GST pull-down assay. All proteins were detected using the indicated antibodies. (D–G) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. The constructs are shown in D, and the corresponding blots are shown below. (H–J) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. The constructs are shown in H, and the corresponding blots are shown below. (K) Semiendogenous interaction between STING and Flag-USP21. THP1 or HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-USP21 cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 10) for the indicated amounts of time. Co-IP experiments were performed using M2 beads, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-STING and anti-Flag. The lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (L) Endogenous USP21 is associated with STING in L929 cells. L929 cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 5) for the indicated time. Co-IP experiments were performed with anti-STING, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. (M) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. After 24 h, cells were stimulated with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) or VSV (MOI = 0.5) for 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Data from A are mass data from one experiment. Data are representative of two (B–D, J, and K–M) or at least three (E–I) independent experiments.

Next, we examined whether the interaction between USP21 and STING is regulated by virus infection. Our data showed that the interaction between USP21 and STING was markedly increased upon virus infection (Fig. 6 K). Moreover, HSV-1 stimulation significantly enhanced the binding of endogenous STING to endogenous Usp21 in L929 cells (Fig. 6 L). Interestingly, we found that both DNA and RNA virus infection enhanced the binding of USP21 to STING and USP21 (Fig. 6 M). These data together indicate that binding of USP21 to STING is regulated by virus infection.

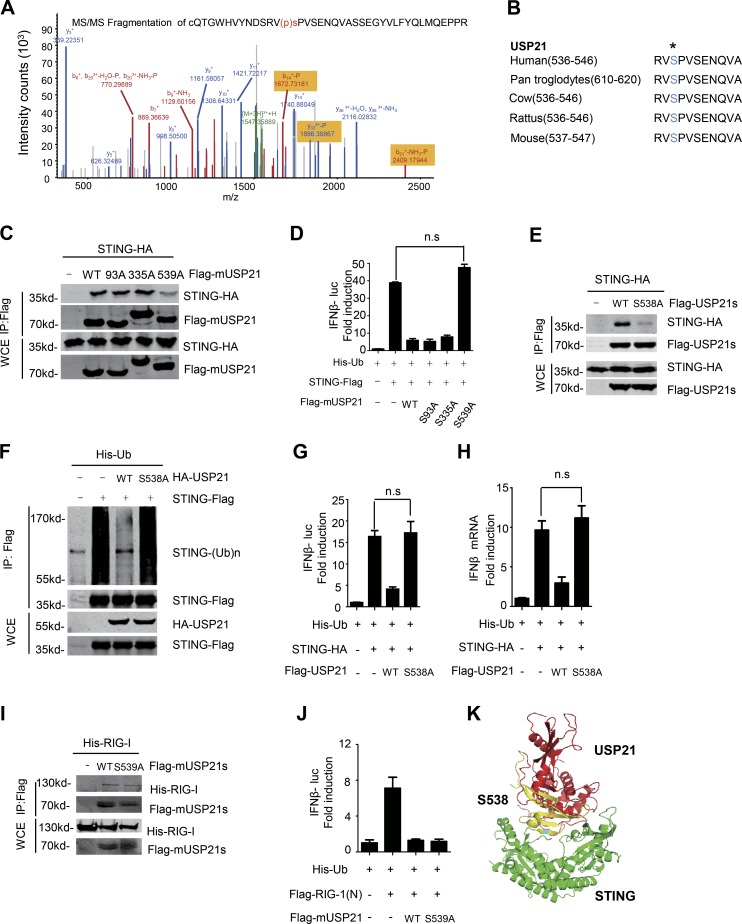

Ser538 is essential for its interaction with STING

Next, we examined the mechanism by which HSV-1 infection enhanced the binding between USP21 and STING. Our data from mass spectrometry showed that HSV-1 infection significantly induced the phosphorylation of USP21 at multiple sites, including Ser93, Ser335, and Ser538 (Table S2 and Fig. 7 A). Ser538 is conserved in USP21 homologues from various species (Fig. 7 B). We therefore examined whether the phosphorylation of USP21 at these sites are involved in its interaction with STING. To this end, we first generated point mutants of mouse Usp21 (S93A, S335A, and S539A) and found that S539A, but not other mutants, displayed a reduced affinity for STING (Fig. 7 C) and failed to inhibit STING-induced IFNβ luciferase activity (Fig. 7 D). We also examined the role of Ser538 of human USP21 in the regulation of STING function by replacement of Ser538 to Ala (USP21S538A). Compared with USP21WT, human USP21S538A also exhibited a reduced affinity for STING (Fig. 7 E) and a reduced ability to deubiquitinate STING (Fig. 7 F). Moreover, USP21S538A failed to block STING-induced IFNβ luciferase activity (Fig. 7 G), as well as IFNβ mRNA induction (Fig. 7 H). In contrast, mutation of S539 had little effect on the binding of mUSP21 to RIG-1 (Fig. 7 I) and the inhibition of RIG-I activity by USP21 (Fig. 7 J).

Figure 7.

Phosphorylation of Ser538 is essential for its interaction with STING. (A) Phosphorylation of USP21 was identified in MS assay which was performed in Fig. 6 A. (B) USP21 contains a putative SPP motif at the C terminus that is conserved in different species. (C) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T for 30 h, and IFNβ luciferase activity was measured. (E) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (F) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads. A denaturation assay was employed to test ubiquitination. (G and H) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. IFNβ mRNA levels were measured by qPCR and IFNβ luciferase activity was tested. (I) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (J) Indicated plasmids were transfected in 293T for 30 h, and IFNβ luciferase activity was measured. (K) The co-structure of USP21 and STING protein is predicted in pymol software. Computational modeling of structures of the USP21 USP domain in complex with STING C-terminal domain (CTD, green). USP21 aa 495–559 are shown in yellow, and USP21 S538 is shown in cyan. Data from A are mass data from one experiment. Data are representative of at least two (I and J) three (C–H) independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± SD in duplicate or triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed paired Student’s t test).

We then employed computational molecular docking to analyze the molecular mechanism by which USP21 Ser538 is involved in its interaction with STING. We found that USP21 (aa 495–559) docked preferentially to a groove on the molecular surface of STING. Interestingly, we also noticed that Ser538 of USP21 lay in the interface between STING and USP21 (Fig. 7 K), consistent with our data showing that Ser538 is one of the critical amino acids mediated the direct binding of USP21 to STING. These data together indicate that Ser538 of USP21 (Ser539 in mouse USP21) is essential for its interaction with STING.

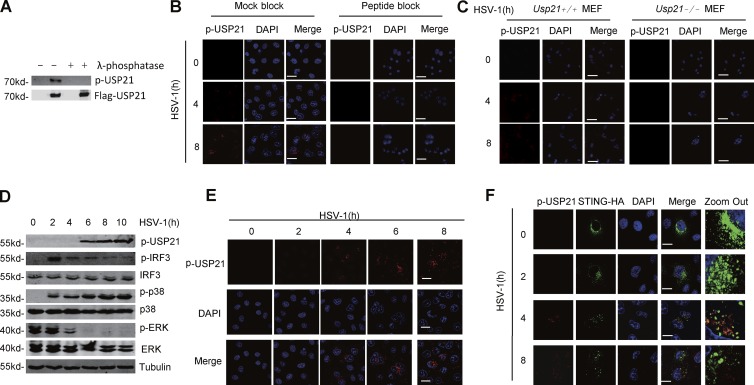

DNA virus–induced phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538

We next examined whether Ser538 can be phosphorylated upon virus infection. To this end, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody that specifically recognized the phosphorylated USP21 at Ser538 (p-S538 antibody). The specificity of this antibody was confirmed using the λ-phosphatase dephosphorylation assay. Our data showed that treatment with λ-phosphatase completely blocked the recognition of USP21, which was purified from HEK293T cells, by p-S538 antibody (Fig. 8 A), suggesting that p-S538 antibody specifically recognized the phosphorylated USP21. Moreover, we confirmed that p-S538 antibody could be used to detect the phosphorylation of endogenous USP21 by immunofluorescence (Fig. 8, B and C).

Figure 8.

Phosphorylation of Ser538 increases under HSV-1 infection. (A) In vitro dephosphorylation to test the specificity of p-USP21 antibody was analyzed. (B) HeLa cells were untreated or infected with HSV-1 for indicated time. The immunofluorescence assay was performed to examine the specificity of p-USP21 with or without peptide blocking. Bars, 50 µm. (C) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were untreated or infected with HSV-1 for indicated times. IF assay to test p-USP21 antibody. Bars, 50 µm. (D) p-USP21 was raised under HSV-1 infection in HeLa cells. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (E) p-USP21 was visualized under HSV-1 infection in HeLa cells by immunoblotting confocal microscopy. Bars, 50 µm. (F) Co-localization of p-USP21 and STING. HeLa cells were transfected with STING-HA. 20 h after transfection, cells were left untreated or infected with HSV-1 at the indicated time points and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Bars, 25 µm. Data from A are mass data from one experiment. Data are representative of at least two (A–C and E) or three (D and F) independent experiments.

We next examined whether HSV-1 infection could induce the phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538. To this end, HeLa cells were cultured in serum-free media to reduce the nonspecific effect from serum and stimulated with HSV-1 virus. Our data showed that the phosphorylation of USP21 was significantly increased upon HSV-1 infection when examined by Western blotting and immunofluorescence (Fig. 8, D and E). Interestingly, we also noticed that the phosphorylated USP21 was mostly localized at the perinuclear microsome (Fig. 8 E), which is similar to the subcellular localization of STING. This prompted us to detect the co-localization between the phosphorylated USP21 and STING in cells. Our data showed that HSV-1 infection induced a significant co-localization between the phosphorylated USP21 and STING at the perinuclear microsome (Fig. 8 F). Taken together, our data indicate that USP21 at Ser538 is phosphorylated by HSV-1 infection.

Phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538 by p38 MAPK

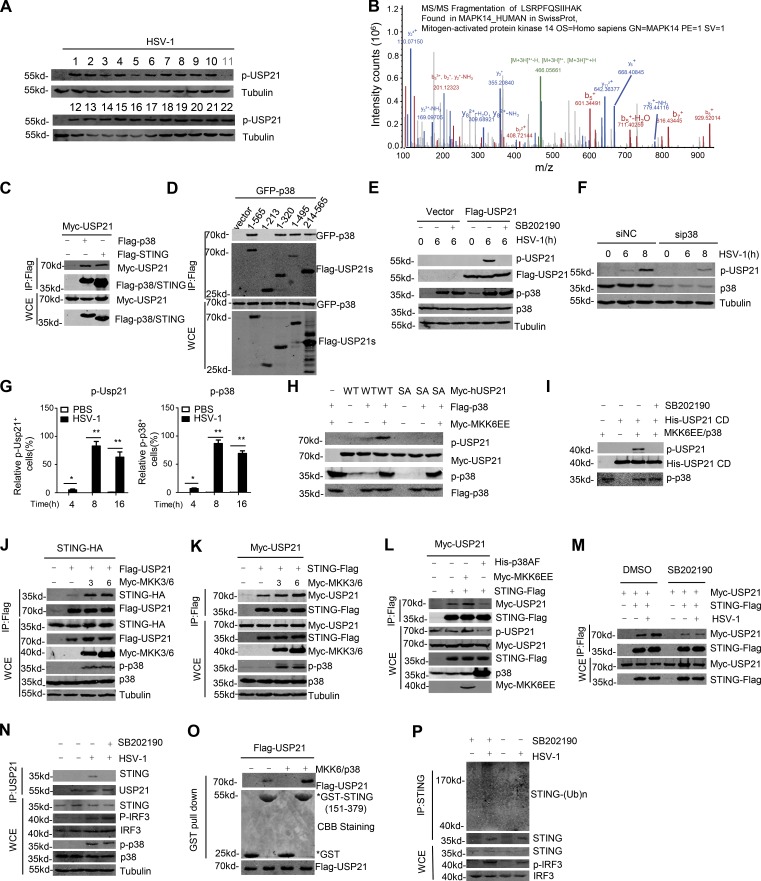

We next aimed to identify the protein kinase that regulates USP21 phosphorylation under HSV-1 infection by screening a library of kinase inhibitors. To this end, HeLa cells were pretreated with various kinase inhibitors for 2 h, and then infected with HSV-1 for another 8 h. We found p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190, but none of other inhibitors screened significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of USP21 induced by HSV-1 (Fig. 9 A and Table S3). Moreover, our mass spectrometry data showed that p38 MAPK is a binding partner of USP21 (Fig. 9 B and Table S1). The interaction between USP21 and p38 was confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 9, C and D). These data prompted us to examine whether p38 kinase is involved in the HSV-1–induced USP21 phosphorylation.

Figure 9.

Phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538 by p38 MAPK. (A) Screening of kinase inhibitors that affected HSV-1–induced p-USP21 level. The inhibitor details are listed in Table S1. (B) p38 was identified as a USP21 binding partner in the MS assay performed in Fig. 6 A. (C and D) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. Cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated and total USP21 in lysates of Flag-USP21 HeLa stable cells treated with DMSO or 10 µM SB202190 and infected for 6 h with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). (F) HeLa were transfected with siNC and sip38, and 48 h later, equal amounts of cells were counted and infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 10) at indicated times. Cell lysate were tested by indicated antibody. (G) FACS analysis of p-USP21 and p-p38 in blood cells obtained from mice (n = 3) that were intravenously injected with HSV-1 (1 × 107 PFU); blood cells were collected at the indicated time. (H) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated and total USP21 in lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmid. (I) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated and total USP21 with an in vitro kinase assay. Purified recombinant His-tagged USP21 CD was incubated with Flag-tagged p38, which was cotransfected with MKK6EE. (J–L) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T cells. Cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (M) The indicated plasmids were transfected into 293T. After 24 h, the cells were pretreated with DMSO or SB202190 for 2 h, after that cells were stimulated with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (N) Endogenous Usp21 is associated with Sting in L929 cells. L929 cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10 µM SB202190. After 2 h, L929 cells were left untreated or infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 5) for 6 h. Co-IP experiments were performed with anti-USP21, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (O) Flag-USP21 and Flag-USP21/MKK6EE/p38 were transfected into 293T. The interaction between USP21 and STING was assessed using a GST pull-down assay. All proteins were detected using the indicated antibodies. (P) L929 cells were pretreated with DMSO or with 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h. Next, the cells were infected with HSV-1 or left uninfected for 4 h, and the lysates were subjected to denaturing immunoprecipitation with an anti-STING antibody or normal IgG, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Data from A are screen data from one experiment. Data from B are mass data from one experiment. Data are representative of at least two (C–G and J–P) or three (H and I) independent experiments.

To this end, HeLa cells were starved for 2 h, and then stimulated with HSV-1 for the indicated time. Our data showed that infection with HSV-1 virus for 6 h significantly induced the phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538, which was completely blocked by treatment with p38 inhibitor SB202190 in Flag-USP21 stably expressing HeLa cells (Fig. 9 E). Consistently, HSV-1 induction also significantly induced the phosphorylation of p38 (Fig. 9 E). As the p38 inhibitor we used inhibits p38 kinase through competition with ATP (Young et al., 1997) without affecting its phosphorylation by upstream MAPKK (Kumar et al., 1999), treatment with these inhibitors had little effect on p38 phosphorylation (Fig. 9 E). However, knockdown of p38 expression resulted in a significant reduction in the phosphorylation of USP21 under HSV-1 stimulation at the indicated time (Fig. 9 F). Physiologically, our data from FACS showed that intravenous injection of HSV-1 into mice significantly induced the phosphorylation of USP21 in blood cells, which was correlated with the phosphorylated p38 levels (Fig. 9 G). Exogenous coexpression of the constitutive active form of MKK6 (MKK6EE) with p38, which induces the activation of p38, significantly induced the Ser538 phosphorylation of USP21WT, but not USP21S538A (Fig. 9 H). The purified USP21 could be phosphorylated by purified active p38 using in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 9 I), suggesting that p38 is a direct kinase that phosphorylates USP21. Collectively, these data indicated that p38 is a physiological kinase involved in HSV-1–induced USP21 phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation by p38 promotes the binding of USP21 to the STING

Next, we examined whether p38 affects the HSV-1–induced binding of USP21 to STING. Our data showed that activation of p38 by coexpression of upstream kinase MKK3 or MKK6 enhanced the binding of USP21 to STING (Fig. 9, J and K). Consistently, dominant-negative p38 (p38AF) blocked the interaction between USP21 and STING (Fig. 9 I). On the other hand, blockage of p38 activation by SB202190 significantly inhibited both exogenous and endogenous interaction between USP21 and STING (Fig. 9, M and N). Importantly, GST pull-down assay showed that phosphorylation of USP21 by activated p38 significantly enhanced the binding of USP21 to the purified STING (Fig. 9 O).

We also examined whether inhibition of p38 activation affected the STING ubiquitination. To this end, L929 cells were pretreated with or without p38 inhibitor SB202190 for 2 h, and then infected with HSV-1 for 4 h. The endogenous STING was immunoprecipitated, and the ubiquitinated STING were examined. Our data showed that treatment with SB202190 significantly increased HSV-1–induced ubiquitination of STING (Fig. 9 P). Taken together, these data indicate that p38-mediated USP21 phosphorylation enhances the binding of USP21 to STING.

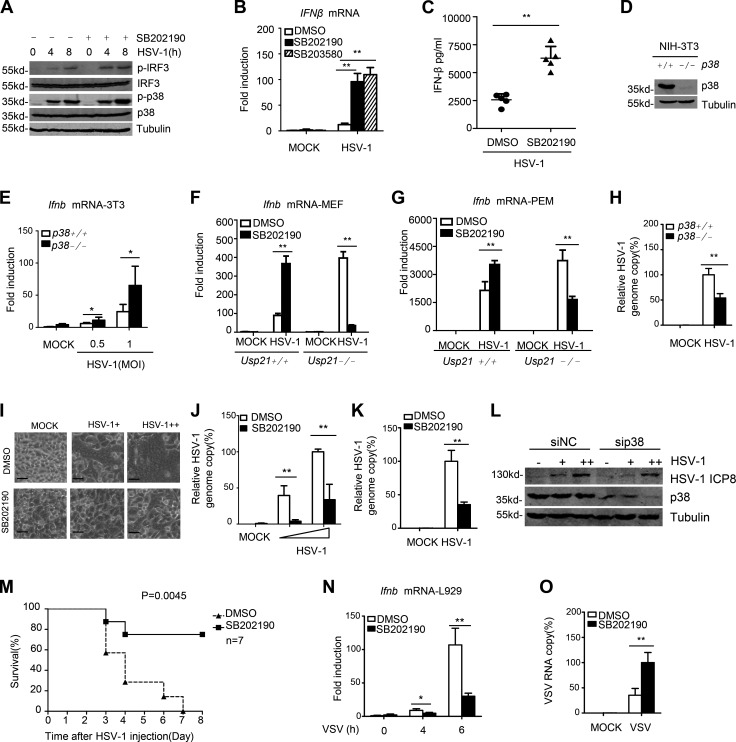

Regulation of innate immune response by p38 MAPK

We then detected whether p38 affects STING-mediated antiviral function. Our data showed that treatment with SB202190 significantly enhanced the HSV-1–induced IRF3 phosphorylation in THP-1 cells (Fig. 10 A). Another p38 inhibitor, SB203580, also enhanced HSV-1–induced IFNβ mRNA expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 10 B). Injection with SB202190 also enhanced Ifnb mRNA expression in mice intravenously injected with HSV-1 (Fig. 10 C). To further confirm these results, we obtained p38-deficient NIH3T3 cells (p38−/−NIH3T3; Fig. 10 D), and detected the role of p38 in HSV-1–induced gene expression. Our data showed that p38 deficiency drastically enhanced Ifnb mRNA production in response to HSV-1 (Fig. 10 E). These data indicate that p38 negatively regulates HSV-1–triggered signaling.

Figure 10.

Regulation of antiviral responses by p38 MAPK. (A) THP-1 cells were pretreated with SB202190, and then infected with HSV-1. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) HeLa were pretreat with different p38 inhibitors used to test HSV-1–induced IFNβ. IFNβ mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (C) WT mice (n = 5 each) were intravenously injected with DMSO or 10 µg SB202190 for 2 h, after which all mice were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 1 × 107 PFU per mouse. Sera were collected, and IFNβ (6 h after infection) was measured by ELISA. (D) Identification for p38+/+ and p38−/− NIH3T3 cells. (E) p38+/+ and p38−/− NIH3T3 cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.5 and 1) for 6 h. Ifnb mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (F) WT or Usp21−/− MEFs were pretreated with DMSO or 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h, followed by infection with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.1) for 4 h. Ifnb mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (G) WT or Usp21−/− PEMs were pretreated with DMSO or 1 µM SB202190 for 2 h, and then infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) for 6 h, and induction of Ifnb mRNAs was measured by qPCR. (H) p38+/+ and p38−/− NIH3T3 cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.1) for 24 h. The relative HSV-1 genome copy ratio was measured by qPCR. (I and J) HeLa cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h. HSV-1 (MOI = 0.5 and 1) infection was then performed for 24 h. Cell morphology was visualized by microscopy (I). The relative HSV-1 genome copy ratio was measured by qPCR (J). Bars, 100 µm. (K) L929 cells were treated with 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h. After that, HSV-1 (MOI = 1) was added into cells for 24 h, and HSV-1 relative genome copy ratio was measured by qPCR. (L) HeLa were transfected with siNC and sip38, 48 h later, equal cell were counted and infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 0.2 and 1) for 24 h. Cell lysate was tested by indicated antibody. (M) WT mice (n = 7 each) were intravenously injected with DMSO or 10 µg SB202190 for 2 h, after which all mice were intravenously injected with HSV-1 at 1 × 107 PFU per mouse. Survival was monitored for 8 d. (N) L929 pretreated with p38 inhibitors were used to test VSV-induced Ifnb mRNA. Ifnb mRNA induction was measured by qPCR. (O) L929 cells were pretreated with 10 µM SB202190 for 2 h. After that, VSV (MOI = 0.1) was added into cells for 24 h, and VSV RNA copy was measured by qPCR. Data are representative of at least two (L–O) or three (A–K) independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± SD in duplicate or triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed paired Student’s t test or Kaplan Meier survival analysis).

We also determined whether the effect of p38 is dependent on USP21. To this end, we examined the effect of SB202190 on HSV-1–induced Ifnb mRNA expression in USP21-deficient MEFs and macrophages. Consistent with our previous data, treatment with SB202190 significantly increased the HSV-1–induced Ifnb expression in both WT MEFs and PEMs. In sharp contrast, SB202190 inhibited the HSV-1–induced Ifnb expression in USP21-deficient MEFs (Fig. 10 F) and PEMs (Fig. 10 G). These data suggested that the enhanced effect of p38 inhibition on HSV-1–induced Ifnb expression is dependent on USP21.

We next examined whether p38 is involved in host defense against HSV-1. Our data showed that deficiency of p38 in NIH3T3 cells resulted in significant resistance to HSV-1 replication (Fig. 10 H). Similar results were obtained from p38 inhibitor treated HeLa and L929 cells (Fig. 10, I–K). Consistently, knockdown p38 expression led to a significant resistance to HSV-1 infection and replication (Fig. 10 L). Importantly, treatment with SB202190 significantly protected mice from lethal HSV-1 infection and elevated the survival rate in mice intravenously infected with lethal HSV-1 (Fig. 10 M).

We also examined the effect of p38 on RNA vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)–induced ifnb expression and replication in L929 cells. Consistent with a previous study (Ren et al., 2016), our data showed that inhibition of p38 reduced VSV induced gene expression (Fig. 10 N) and enhanced VSV infection (Fig. 10 O). These data are also consistent with our data showing that phosphorylation of USP21 differentially regulates DNA and RNA virus induced gene expression (Fig. 7, G and J). These data collectively suggest that p38-mediated USP21 phosphorylation may play different roles in host defense against DNA and RNA virus infection.

Discussion

In this study, we identified USP21 as an essential regulator of STING-mediated innate antiviral response. We found that prolonged DNA virus infection induces the phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538 by activation of p38 MAPK, which in turn promotes the binding of USP21 to STING, deubiquitinates and inactivates STING. These findings reveal that p38–USP21 axis is a negative pathway that regulates the STING-mediated innate immune response to DNA virus infection.

STING is an essential adaptor in the innate immune response to DNA virus (Ishikawa et al., 2009). Accumulating evidence indicate that different types of polyubiquitination are critical for STING-mediated antiviral response (Shu and Wang, 2014). However, the deubiquitination of STING is largely unknown. In this study, we found that USP21 negatively regulates STING-mediated antiviral gene expression, as well as host antiviral response. It has been shown that USP21 also negatively regulates the RNA-virus–induced type I IFN signaling and TNF-mediated NF-κB signaling though deubiquitinating RIG-I and RIP1 (Xu et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2014). Our data indicate that phosphorylation of USP21 differently affects DNA and RNA virus signaling. Thus, these findings together suggest that USP21 regulates host defense against both DNA and RNA virus via different mechanism.

STING is regulated by different linkage of polyubiquitin chains, which plays distinct roles in regulating STING-mediated antiviral response. The precise regulation of STING function by these different types of polyubiquitin remains elusive. K63/K27 polyubiquitination of STING mediated by E3 ligase TRIM32, TRIM56, or AMFR is positively regulates DNA virus–triggered signaling and type I IFN expression (Tsuchida et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). A recent study showed that K48-linked polyubiquitination of STING is regulated by the complex of deubiquitinase EIF3S5 and USP20 (Luo et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). However, how the other types of polyubiquitination of STING are regulated by deubiquitination is unclear. Our study demonstrated that USP21 removes both K27- and K63-linked polyubiquitination chains from STING. Importantly, this result is consistent with our findings showing that USP21 inhibits the recruitment of TBK1 and IRF3 to STING and STING-mediated antiviral functions. Moreover, we found that USP21 can remove K6-, K29-, and K33-linked polyubiquitination from STING. This is consistent with previous studies showing that USP21 is able to cleave K6-, K11-, K29-, K48-, and K63-ubiquitin chains (Ye et al., 2011). Together, our findings indicate that USP21 is a physiological DUB for STING.

p38 MAPK has been shown to play an important role in host defense against various viruses, such as HIV, HCMV, and HBV infections (Cohen et al., 1997; Shapiro et al., 1998; Johnson et al., 1999; Chang et al., 2008). However, the exact mechanism by which p38 MAPK regulates DNA virus infection remains to be investigated. Our study indicates that long-term HSV-1 infection induces the prolonged p38 MAPK activation. Importantly, we identified USP21 is a functional substrate of p38. Our data showed that phosphorylation of USP21 by p38 promotes its binding to STING and inactivates STING in response to HSV-1 infection. Thus, our study uncovers a mechanism by which DNA virus–induced p38 activation negatively regulates STING-mediated antiviral response. Although our data showed that USP21 is required for p38 inhibitor SB201290 to enhance INFs expression in response to HSV-1, we noticed that deficiency of USP21 resulted in the inhibition of HSV-1–induced gene expression by SB201290. These data suggest that p38 may have multiple targets that either positively or negatively regulates HSV-1–mediated gene expression. We also found that p38 plays different roles in DNA and RNA virus infection. Thus, the detailed mechanism by which p38 regulates virus infection remains to be examined in future studies.

USP21 is a nuclear-cytoplasm shuttling protein that can be detected in both nucleus and cytoplasm (García-Santisteban et al., 2012). Moreover, USP21 has been shown to be able to bind to microtubule and centrosome (Urbé et al., 2012). Our data indicated that microtubule association is not required for USP21-mediated STING inactivation (unpublished data). Interestingly, we found that Ser538-phosphorylated USP21 is mainly localized at perinuclear microsome, which exhibits a similar localization with the activated STING. These data strongly support our findings that the phosphorylated USP21 is an important regulator of STING. The mechanism by which the phosphorylated USP21 is recruited to perinuclear microsome remains to be investigated. Interestingly, our recent study shows that USP21 is phosphorylated at Ser539 by ERK signaling in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), and the phosphorylation blocked the interaction between USP21 and Nanog and consequently promoted the mESC differentiation (Jin et al., 2016). These findings suggest that USP21 function is tightly controlled by different mechanisms under different physiological and pathological conditions.

Several essential regulators of STING have been identified, such as AMFR, NLRC3, NLRX1, and RNF26 (Qin et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016). Although virus infection can induce the expression of Trim56, iRhom2, and Trim30α at the transcriptional level (Tsuchida et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2016), how DNA virus controls the function of those regulators remains largely understood. In this study, we uncover a mechanism that the regulator of STING is controlled at a posttranslational level. We found that DNA virus regulates host antiviral responses through phosphorylation of USP21 to negatively regulate STING function. Together, these data suggest that the regulator of STING may be precisely and dynamically controlled during microbial infection at both transcriptional and posttranslational levels.

Except function as an essential regulator of IFN production induced by microbial infections, recent studies indicate that STING can also sense the cytosolic tumor–derived DNA in tumor-associated immune cells and is involved in anticancer immune responses (Woo et al., 2015). Activation of STING pathway by pharmacologic agonists is regarded as a potential approach for both antiviral and anticancer therapy by enhancing host immunity mediated by type I IFN. Our study showed that inhibition of either USP21 or p38 function results in a significant production of I IFN through activation STING pathway, raising the possibility that drugs targeting p38-USP21 axis may enhance immune responses against DNA virus or cancer and benefit certain patients with low levels of immune activity.

In summary, we propose a process in which the response to DNA virus infection is classified into three stages: quiescent stage, early stage, and late stage. In the quiescent stage, STING activity is relatively low and the production of IFNβ is inhibited. In the early stage of DNA virus infection, STING pathway is rapidly activated and induces host cells expressing various antiviral genes. In the late stage of virus infections, p38 MAPK is activated and subsequently induces the phosphorylation of USP21 at Ser538. USP21 phosphorylation strongly promotes its binding to STING, which leads to removal of K27/63-linked polyubiquitin chains from STING and blocks the recruitment of TBK1 and IRF3 to STING, thereby resulting in the inactivation of type I IFN signaling. These findings demonstrate that USP21 is a negative regulator of antiviral immunity and highlight a novel regulatory mechanism that involves the p38-mediated phosphorylation of USP21.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HEK293T, HeLa, L929, THP-1, and Vero were purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and maintained in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Usp21+/+ and Usp21−/− MEFs were provided by J. Yang (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). Sting−/− MEFs were provided by Z. Jiang (Peking University, Peking, China). p38+/+NIH3T3 and p38−/−NIH3T3 were provided by L. Hui (Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Shanghai, China). All cells were grown in a 37°C incubator supplied with 5% CO2. BMDMs and PEMs were prepared as described previously (Sun et al., 2016).

Transfection

For plasmids, transfection was performed using the calcium phosphate-DNA co-precipitation method for the 293T cells, Lipofectamine 3000 for the MEFs, and Trans EZ for the HeLa cells, following the manufacturers’ protocols. Lipofectamine 2000 was used to transfect siRNA and dsDNA into L929, MEFs, PEMs, and BMDMs.

Experimental animals and treatment

Usp21fl/fl mice were a gift from B. Li (Institute Pasteur of Shanghai, Shanghai, China). Lyz2-cre transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the mouse lysozyme M gene regulatory region were generously provided by the animal center of East China Normal University. PCR was used to identify the genotype of the offspring from the intercrossed Usp21+/− Lyz2-cre+/− mice. The filial generations were further crossed to Usp21fl/fl mice to generate myeloid cell–specific Usp21-deficient mice (Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre). Littermates who lacked the Cre gene (Usp21fl/fl Lyz2-cre−/−) were used as controls. Primers for Usp21 and Lyz2 genotyping are listed in Table S4. Primer for Usp21−/−MEFs genotype identification has been described in Fan et al. (2014).

The mice were maintained under specific pathogen–free (SPF) conditions at the East China Normal University. Animal care and experiments were done in compliance with protocols approved by East China Normal University. For the in vivo antivirus study, age- and sex-matched groups of mice were intravenously infected with HSV-1.

Plasmids, antibody, and reagents

5′ pcDNA3.1 4XFlag, 3xMyc, Flag, HA, and GFP vector were used to make expression plasmids. STING was amplified from THP-1 cDNA and cloned into 3′FLAG/HA vector. cGAS was amplified from THP-1 cDNA and cloned into 5′FLAG vector. Flag-IRF3, IFNβ-luciferase, Myc-TBK1, and His-RIG-I were provided by X. Wang (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China). GST-tagged STING was cloned into pGEX-4T-2. His-ubiquitin expression plasmids were described previously (Liu et al., 2010). All truncations and point mutants were constructed by standard molecular biology techniques. All construct were sequenced. The antibodies used in this study are listed below: Flag (Sigma-Aldrich), Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), hUSP21 (ABGENT), Ubiquitin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), STING (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), IRF3 (Cell Signaling Technology), P-IRF3 (Cell Signaling Technology), STING (Cell Signaling Technology), p38 (Cell Signaling Technology), p-p38 (Cell Signaling Technology), mUsp21 (Abcam), HSV-1 ICP8 (Abcam), goat anti–rabbit IgG-FITC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against phospho-USP21 was generated using a CN-DSRVp[Ser]PVSEN peptides (Abmart). Protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Lipofectamine 2000 and 3000 (Invitrogen), Dual-specific luciferase assay kit (Promega). Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). SB202190 (Sigma-Aldrich), and SB203580 (Beyotime). Kinase Inhibitor Library in Table S3 was obtained from The National Resource Center for Small Molecule Compounds (Shanghai, China).

Virus, dsDNA, and L. monocytogenes

HSV-1 was provided by X. Wang (Zhejiang University). L. monocytogenes were described previously (Sun et al., 2016). Listeria monocytogenes was cultured in 3.7% Brain-Heart Infusion broth (BD). VSV was kindly provided by B. Du (East China Normal University, Shanghaii, China). HSV-1 was propagated and titered by plague assays on Vero Cells. Adv-EGFP was purchased from JiTai. HSV60 DNA were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at 4 µg/ml to MEFs or L929 for the indicated time. HSV60 mer-Sense, 5′-TAAGACACGATGCGATAAAATCTGTTTGTAAAATTTATTAAGGGTACAAATTGCCCTAGC-3′; anti-sense, 5′-ATTCTGTGCTACGCTATTTTAGACAAACATTTTAAATAATTCCCATGTTTAACGGGATCG-3′.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

The following oligonucleotide against genes were used: siRNA against Usp21 (5′-GACCGAGCCAACUUAAUGUTT-3′); siRNA against p38 (5′-GCAUAAUGGCCGAGCUGUUTT-3′). 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with HSV-1 or transfect dsDNA at indicated times.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions, treated with RNase-free DNase, and subjected to reverse transcription with random hexanucleotide primers. Total RNA was extracted and assayed by real-time qPCR as described with SYBR Green Master Mix. Primers used were as in Table S5.

HSV-1 genomic DNA copy number measurement

HSV-1 genomic DNA copy numbers were measured by qPCR with HSV-1–specific primer: 5′-TGGGACACATGCCTTCTTGG-3′ and 5′-ACCCTTAGTCAGACTCTGTTACTTACCC-3′.

Luciferase reporter analysis

HEK293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected the following day by Hepes-Calcium phosphate according to the manufacturer’s instruction. 10 ng of Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid and 50 ng of firefly luciferase reporter plasmids were transfected together with indicated expression plasmids. Luciferase activity measured indicated time after transfection via the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System. Relative IFNβ expression was calculated as firefly luminescence relative to Renilla luminescence.

IP analysis and immunoblot analysis

IP and Western blot were conducted as previously described (Liu et al., 2010). Transfected cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and a mixture of protease inhibitors) and cleared by centrifugation. Cleared cell lysates were incubated with 10 µl of M2 beads (Sigma-Aldrich)/HA beads (Abmart) for 3 h.

To detect endogenous protein interactions, L929 cells were infected by HSV-1 at indicated time before harvesting. Cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer. Cleared cell lysates were incubated with indicated antibody and 16 µl of protein A/G beads for 3 h at 4°C. After extensive washing, beads were boiled at 100°C for 5 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (EMD Millipore), followed by immunoblotting using indicated antibody. Immunoblots were analyzed using the Odyssey system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Deubiquitination assay

In vivo deubiquitination assays were performed as described previously (Choo and Zhang, 2009). In brief, STING-FLAG/HA constructs was transiently transfected into 293T cells with or without His-ubiquitin and USP21WT/CA. Cells were lysed with 100 µl lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), boil for 10 min. 900 µl of dilution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton) was added, and samples were incubated at 4°C for 30–60 min with rotation. The diluted samples were spun at 20,000 g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and M2 or HA beads were added. The beads were spun down at 5,000 g for 5 min, and then the supernatant was aspirated. The resin was washed with washing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40) twice. The beads were spun for a final time at 20,000 g for 30 s, and then the residual washing buffer was aspirated and the resin was boiled with 2XSDS loading buffer. Samples were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE gel for immunoblotting analysis. Endogenous ubiquitination was tested using STING antibody and protein A/G beads, the ubiquitination was also performed using the denature assay.

For in vitro deubiquitination assays, STING-Flag were transfected into 293T cells along with HA-Ub. After 30-h transfection, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using M2 beads. His-USP21 CD (catalytic domain) WT/CA protein was added into the reaction system. In vitro deubiquitination assay mixture contained deubiquitinase and HA-Ubiquitin–conjugated STING. After incubation for 60 min in 37°C, the mixture was detected by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. All ubiquitination tests were using denature assay.

GST pull-down analysis

For GST pull-down analysis, purified recombinant GST-fusion proteins were incubated with preequilibrated glutathione-Sepharose beads for 2 h, followed by extensive washing. The preloaded GST resins were incubated with Flag-USP21 cell lysates, respectively, for 2 h at 4°C. Precipitates were extensively washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot analysis.

In vitro kinase assay

The recombinant Flag-p38 protein was immunoprecipitated from MKK6EE/Flag-p38 plasmid transfected 293T cell lysates. His-USP21 CD was purified from E. coli respectively, and then subjected to in vitro kinase assay in kinase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 10 mM MgCl2) in the presence of 100 mM ATP for 1 h at 30°C in or absence with 10 µM SB202190. The kinase reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and were detected by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies.

Measurement of cytokines

Concentrations of the mouse IFNβ in culture supernatants or mouse serum were measured by VeriKine Mouse IFN Beta ELISA Kit (PBL InterferonSource) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mTNF and mIL-6 were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions in TNF ELISA kit (MIAO TONG-BIO), and Mouse IL-6 ELISA kit (eBioscience).

Flow cytometry

To examine HSV-1 virus infection–induced p-USP21 and p-p38, HSV-1 (107 PFU) was tail intravenously injected into mice for indicated time, and then the white blood cells were collected and stained using standard intracellular staining protocol. The data were collected using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Confocal microscopy

HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-USP21 and STING-HA expressing plasmids. After 24 h, cells were stimulated for indicated time with HSV-1, then cell were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were rinsed once with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 and rinsed twice with PBS. The coverslips were blocked with blocking buffer for 1 h (0.3% BSA in PBS) and incubated in a primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Next, the coverslips were rinsed twice with blocking buffer and incubated in secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The glass coverslips were mounted using Mowiol and were examined using a LSM 510 Meta confocal system (ZEISS) under a 100× oil objective.

MS analysis and mass spectral data analysis

MS assay was carried out as previously described (Deng et al., 2015). In brief, HeLa were transfected with Flag-USP21; 24 h later, HSV-1 (MOI = 10) was added into cells for 8 h, Flag-USP21 were immunoprecipitated with M2 beads, and MS assay was used for analysis.

IHC staining of HSV-1 infects brain

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into sections, and placed on adhesion microscope slides. Sections were subjected to immunohistochemical (IHC) staining according to standard procedures. The anti–HSV-1 ICP8 antibody (Abcam) was used for staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel or Graph prism5.0. All data are presented as mean ± SD. A two-tailed Student's t test assuming equal variants was used to compare two groups. In all figures, the statistical significance between the indicated samples and control is designated as *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; or NS (P > 0.05).

Online supplemental material

Table S1 list mass spectrometry analysis of binding partner of exogenous human USP21 in HeLa infected with HSV-1. Table S2 lists mass spectrometry analysis of serine-phosphorylated residues of exogenous human USP21 in HeLa infected with HSV-1. Table S3 lists inhibitor library information. Table S4 lists primers for Usp21 mice genotype identification. Table S5 lists qPCR primers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Xiaojian Wang, Bin Sun, and Lijian Hui for reagents and cells.

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0902102), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (973 program 2012CB910404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91519322, 91440104, and 31501135), and the Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20130076110022).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Y. Chen and P. Wang conceived the project and designed experiments. Y. Chen, L. Wang, J. Jin, Y. Luan, C. Chen, Y. Li., G. Liao, Y. Yu, W. Pan, L. Fang, Y. Wang, H. Teng, and H. Chu performed experiments. Y. Chen, L. Wang, J. Jin, X. Ge, X. Wang, H. Chu, and P. Wang analyzed the data. B. Li provided Usp21fl/fl mice, and Z. Jiang provided Sting−/− MEFs. Y. Chen, L. Wang, X. Ge, and P. Wang wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- BMDM

- BM-derived macrophage

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- IRF3

- IFN regulatory factor-3

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PEM

- peritoneal macrophage

- VSV

- vesicular stomatitis virus

- STING

- stimulator of IFN genes

References

- Ablasser A., Goldeck M., Cavlar T., Deimling T., Witte G., Röhl I., Hopfner K.P., Ludwig J., and Hornung V.. 2013. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 498:380–384. 10.1038/nature12306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., and Takeuchi O.. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 124:783–801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerik A.Y., and Hochstrasser M.. 2004. Mechanism and function of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1695:189–207. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer K.A., Durack J., and Portnoy D.A.. 2014. STING-dependent type I IFN production inhibits cell-mediated immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003861 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoj V.G., and Chen Z.J.. 2009. Ubiquitylation in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature. 458:430–437. 10.1038/nature07959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W.W., Su I.J., Chang W.T., Huang W., and Lei H.Y.. 2008. Suppression of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in human hepatoma cell: the antiviral role of nitric oxide. J. Viral Hepat. 15:490–497. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Y.S., and Zhang Z.. 2009. Detection of protein ubiquitination. J. Vis. Exp. 1293 10.3791/1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.S., Schmidtmayerova H., Dennis J., Dubrovsky L., Sherry B., Wang H., Bukrinsky M., and Tracey K.J.. 1997. The critical role of p38 MAP kinase in T cell HIV-1 replication. Mol. Med. 3:339–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Jiang C., Chen L., Jin J., Wei J., Zhao L., Chen M., Pan W., Xu Y., Chu H., et al. 2015. The ubiquitination of rag A GTPase by RNF152 negatively regulates mTORC1 activation. Mol. Cell. 58:804–818. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A., Avvakumov G., Tong J., Fan Y., Zhao Y., Alberts P., Persaud A., Walker J.R., Neculai A.M., Neculai D., et al. 2013. A strategy for modulation of enzymes in the ubiquitin system. Science. 339:590–595. 10.1126/science.1230161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Mao R., Yu Y., Liu S., Shi Z., Cheng J., Zhang H., An L., Zhao Y., Xu X., et al. 2014. USP21 negatively regulates antiviral response by acting as a RIG-I deubiquitinase. J. Exp. Med. 211:313–328. 10.1084/jem.20122844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Santisteban I., Bañuelos S., and Rodríguez J.A.. 2012. A global survey of CRM1-dependent nuclear export sequences in the human deubiquitinase family. Biochem. J. 441:209–217. 10.1042/BJ20111300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., König R., Deng M., Riess M., Mo J., Zhang L., Petrucelli A., Yoh S.M., Barefoot B., Samo M., et al. 2016. NLRX1 sequesters STING to negatively regulate the interferon response, thereby facilitating the replication of HIV-1 and DNA viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 19:515–528. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heride C., Rigden D.J., Bertsoulaki E., Cucchi D., De Smaele E., Clague M.J., and Urbé S.. 2016. The centrosomal deubiquitylase USP21 regulates Gli1 transcriptional activity and stability. J. Cell Sci. 129:4001–4013. 10.1242/jcs.188516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H., Ma Z., and Barber G.N.. 2009. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 461:788–792. 10.1038/nature08476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J., Liu J., Chen C., Liu Z., Jiang C., Chu H., Pan W., Wang X., Zhang L., Li B., et al. 2016. The deubiquitinase USP21 maintains the stemness of mouse embryonic stem cells via stabilization of Nanog. Nat. Commun. 7:13594 10.1038/ncomms13594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Waterman P.M., Jonscher K.R., Short C.M., Reisdorph N.A., and Cambier J.C.. 2008. MPYS, a novel membrane tetraspanner, is associated with major histocompatibility complex class II and mediates transduction of apoptotic signals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:5014–5026. 10.1128/MCB.00640-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.A., Huong S.M., and Huang E.S.. 1999. Inhibitory effect of 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H - imidazole on HCMV DNA replication and permissive infection. Antiviral Res. 41:101–111. 10.1016/S0166-3542(99)00002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Jiang M.S., Adams J.L., and Lee J.C.. 1999. Pyridinylimidazole compound SB 203580 inhibits the activity but not the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 263:825–831. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Li H., Li S., Shen M., Xiao N., Chen Y., Wang Y., Wang W., Wang R., Wang Q., et al. 2010. The Fbw7/human CDC4 tumor suppressor targets proproliferative factor KLF5 for ubiquitination and degradation through multiple phosphodegron motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 285:18858–18867. 10.1074/jbc.M109.099440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Cai X., Wu J., Cong Q., Chen X., Li T., Du F., Ren J., Wu Y.T., Grishin N.V., and Chen Z.J.. 2015. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science. 347:aaa2630 10.1126/science.aaa2630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W.W., Li S., Li C., Lian H., Yang Q., Zhong B., and Shu H.B.. 2016. iRhom2 is essential for innate immunity to DNA viruses by mediating trafficking and stability of the adaptor STING. Nat. Immunol. 17:1057–1066. 10.1038/ni.3510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., and Damania B.. 2016. The cGAS-STING defense pathway and its counteraction by viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 19:150–158. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D., and Riezman H.. 2007. Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science. 315:201–205. 10.1126/science.1127085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A., Yamaguchi L., and Nakanishi M.. 2016. Regulation of maintenance DNA methylation via histone ubiquitylation. J. Biochem. 159:9–15. 10.1093/jb/mvv113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Zhou M.T., Hu M.M., Hu Y.H., Zhang J., Guo L., Zhong B., and Shu H.B.. 2014. RNF26 temporally regulates virus-triggered type I interferon induction by two distinct mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004358 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y., Zhao Y., Lin D., Xu X., Zhu Q., Yao J., Shu H.B., and Zhong B.. 2016. The Type I Interferon-IRF7 axis mediates transcriptional expression of Usp25 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 291:13206–13215. 10.1074/jbc.M116.718080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T., Fujita N., Hayashi T., Takahara K., Satoh T., Lee H., Matsunaga K., Kageyama S., Omori H., Noda T., et al. 2009. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:20842–20846. 10.1073/pnas.0911267106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L., Heidenreich K.A., Meintzer M.K., and Dinarello C.A.. 1998. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in HIV type 1 production in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:7422–7426. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu H.B., and Wang Y.Y.. 2014. Adding to the STING. Immunity. 41:871–873. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Luan Y., Xiang D., Tan X., Chen H., Deng Q., Zhang J., Chen M., Huang H., Wang W., et al. 2016. The 11S proteasome subunit PSME3 is a positive feedforward regulator of NF-κB and important for host defense against bacterial pathogens. Cell Reports. 14:737–749. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Wu J., Du F., Chen X., and Chen Z.J.. 2013. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 339:786–791. 10.1126/science.1232458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Li Y., Chen L., Chen H., You F., Zhou X., Zhou Y., Zhai Z., Chen D., and Jiang Z.. 2009. ERIS, an endoplasmic reticulum IFN stimulator, activates innate immune signaling through dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:8653–8658. 10.1073/pnas.0900850106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A., Wang Z., Choi M.K., Yanai H., Negishi H., Ban T., Lu Y., Miyagishi M., Kodama T., Honda K., et al. 2007. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 448:501–505. 10.1038/nature06013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T., Zou J., Saitoh T., Kumar H., Abe T., Matsuura Y., Kawai T., and Akira S.. 2010. The ubiquitin ligase TRIM56 regulates innate immune responses to intracellular double-stranded DNA. Immunity. 33:765–776. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterholzner L., Keating S.E., Baran M., Horan K.A., Jensen S.B., Sharma S., Sirois C.M., Jin T., Latz E., Xiao T.S., et al. 2010. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 11:997–1004. 10.1038/ni.1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbé S., Liu H., Hayes S.D., Heride C., Rigden D.J., and Clague M.J.. 2012. Systematic survey of deubiquitinase localization identifies USP21 as a regulator of centrosome- and microtubule-associated functions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23:1095–1103. 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Liu X., Cui Y., Tang Y., Chen W., Li S., Yu H., Pan Y., and Wang C.. 2014. The E3 ubiquitin ligase AMFR and INSIG1 bridge the activation of TBK1 kinase by modifying the adaptor STING. Immunity. 41:919–933. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lian Q., Yang B., Yan S., Zhou H., He L., Lin G., Lian Z., Jiang Z., and Sun B.. 2015. TRIM30α is a negative-feedback regulator of the intracellular DNA and DNA virus-triggered response by targeting STING. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1005012 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welchman R.L., Gordon C., and Mayer R.J.. 2005. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:599–609. 10.1038/nrm1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo S.R., Corrales L., and Gajewski T.F.. 2015. The STING pathway and the T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 36:250–256. 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., and Chen Z.J.. 2014. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32:461–488. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Tan X., Wang H., Sun W., Shi Y., Burlingame S., Gu X., Cao G., Zhang T., Qin J., and Yang J.. 2010. Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 21 inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation via binding to and deubiquitinating receptor-interacting protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 285:969–978. 10.1074/jbc.M109.042689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Akutsu M., Reyes-Turcu F., Enchev R.I., Wilkinson K.D., and Komander D.. 2011. Polyubiquitin binding and cross-reactivity in the USP domain deubiquitinase USP21. EMBO Rep. 12:350–357. 10.1038/embor.2011.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P.R., McLaughlin M.M., Kumar S., Kassis S., Doyle M.L., McNulty D., Gallagher T.F., Fisher S., McDonnell P.C., Carr S.A., et al. 1997. Pyridinyl imidazole inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase bind in the ATP site. J. Biol. Chem. 272:12116–12121. 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]