Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: glucocorticoids, meta-analysis, pain control, total joint arthroplasty

Abstract

Background:

This meta-analysis aimed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of intravenous glucocorticoids for reducing pain intensity and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA).

Methods:

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, and Google databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing intravenous glucocorticoids versus no intravenous glucocorticoids or sham for patients undergoing TJA. Outcomes included visual analogue scale (VAS) pain at 12, 24, and 48 hours; the occurrence of PONV; length of hospital stay; the occurrence of infection; and blood glucose levels after surgery. We calculated risk ratios (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and the weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Trial sequential analysis was also used to verify the pooled results.

Results:

Thirteen clinical trials involving 821 patients were ultimately included in this meta-analysis. The pooled results indicated that intravenous steroids can decrease VAS at 12 hours (WMD = −8.54, 95% CI −11.55 to −5.53, P = 0.000; I2 = 35.1%), 24 hours (WMD = −7.48, 95% CI −13.38 to −1.59, P = 0.013; I2 = 91.8%), and 48 hours (WMD = −1.90, 95% CI −3.75 to −0.05, P = 0.044; I2 = 84.5%). Intravenous steroids can decrease the occurrence of PONV (RR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.44–0.73, P = 0.000; I2 = 33.1%). There was no significant difference in the length of hospital stay, occurrence of infection, and blood glucose levels after surgery.

Conclusion:

Intravenous glucocorticoids not only alleviate early pain intensity but also decrease PONV after TJA. More high-quality RCTs are required to determine the safety of glucocorticoids before making final recommendations.

1. Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is often cited as the most common complication after anesthesia, with a reported incidence of 20% to 38% after major orthopedic surgery.[1–3] Despite an increased emphasis on postoperative pain control, several recent studies have indicated that 30% to 77% of patients experience moderate-to-severe pain postoperatively.[4] Many multimodal analgesic regimens have become the standard protocol to minimize postoperative pain and nausea and improve functional recovery following total joint arthroplasty (TJA, including total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA)).[5] Intravenous glucocorticoids have been shown to reduce the postoperative rise of serum markers of systemic inflammation and lung injury in patients undergoing TKA and THA.[6] A single preoperative dose of glucocorticoids may be a prophylactic agent for decreasing PONV. However, concerns regarding their effects and potential side effects have prevented glucocorticoids from being regularly included in perioperative protocols for TJA despite randomized trials indicating short-dose glucocorticoids to be safe and effective for reducing PONV.[6] Moreover, there has been no meta-analysis comparing the effects and safety of glucocorticoids for TJA. Thus, we performed a meta-analysis and trial sequence analysis (TSA) to summarize the existing evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the effectiveness and safety of glucocorticoids for TJA.

2. Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[7] and was written in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) checklist.[8]

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

The electronic databases PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, and Google database were systematically searched from inception to December 31, 2016. The detailed PubMed search strategy was as follows: (((((((((((“Arthroplasty, Replacement, Knee”[Mesh]) OR TKR) OR TKA) OR total knee replacement) OR total knee arthroplasty) OR “Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip”[Mesh]) OR THR) OR THA) OR total hip arthroplasty) OR total hip replacement)) AND (glucorticoid OR steroid OR corticosteroid OR hydrocortisone OR cortisone OR prednisone OR methylprednisone OR triamcinolone OR dexamethasone OR betamethasone). Meta-analysis was collected from published data and thus ethical review or approved was not necessary.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

-

1.

Participants: Patients undergoing primary TJA.

-

2.

Interventions: The comparison group was a preoperative intravenous administration of glucocorticoids.

-

3.

Comparisons: The comparison group was with no intravenous glucocorticoids or sham group.

-

4.

Outcomes: Visual analogue scale (VAS) at 12, 24, and 48 hours after TJA, the occurrence of PONV, the incidence of infection, length of hospital stay and blood glucose level after surgery.

-

5.

Study design: Only RCTs were included.

2.3. Data extraction and outcome measures

Two authors (PC and XL) independently extracted the author, publication year, the number of patients in intervention and control groups, the proportion of male patients and the mean age of the patients, the dose of glucocorticoids and comparison, outcomes and duration of follow-up. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion. Different types of glucocorticoids were converted to equivalence to dexamethasone: 0.75 mg dexamethasone = 4 mg methylprednisolone = 5 mg prednisolone = 20 mg hydrocortisone.[9] The outcomes were VAS at 12, 24, and 48 hours; the occurrence of PONV; the length of hospital stay; the occurrence of infection; and blood glucose level after surgery. If the data were not reported numerically, we extracted mean and standard deviation values from the published papers using GetData Graph Digitizer software as needed.[7]

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (LS and JH) independently evaluated the risk of bias of included RCTs according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.[7] The assessment criteria included the following 7 domains: random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases. All domains were evaluated as “low,” “high,” or “unclear” according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.3.0)[7] and the risks of bias were drawn by the Review Manager 5.3.0 software (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

2.5. Quality of evidence assessment

Two reviewers (LS and JH) independently evaluated the quality of evidence assessment in accordance with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology.[10] Risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias were the assessment items.[10,11] Each result was classified as high, moderate, low, or very low. GRADE Pro software was used to construct summary tables for the included studies.

2.6. Statistical analysis

For VAS at 12, 24, and 48 hours, the length of hospital stay; and blood glucose levels after surgery, the weighted mean difference (WMD), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. For dichotomous outcomes (the occurrence of PONV and infection), we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI. Heterogeneity was considered to be statistically significant if the I2 value was greater than 50%. A fixed-effects model was applied if the I2 value was less than 50%. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). The subgroup analysis was conducted based on the dose of glucocorticoids (≥10 mg (high dose) or <10 mg (low dose)) and TKA or THA. The relationship between glucocorticoid dosage and the occurrence of PONV was explored using SPSS software (SPSS Corp., Chicago, USA). The correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the relationship between glucocorticoid dosage and the occurrence of PONV. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kappa values were used to measure the degree of agreement between the 2 reviewers and were rated as follows: fair, 0.40 to 0.59; good, 0.60 to 0.74; and excellent, 0.75 or more.[12] To test the robustness of the pooled results and avoid a type I error,[13–16] TSA was conducted (TSA software, version 0.9.5.5 beta; Copenhagen Trial Unit) for the primary outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

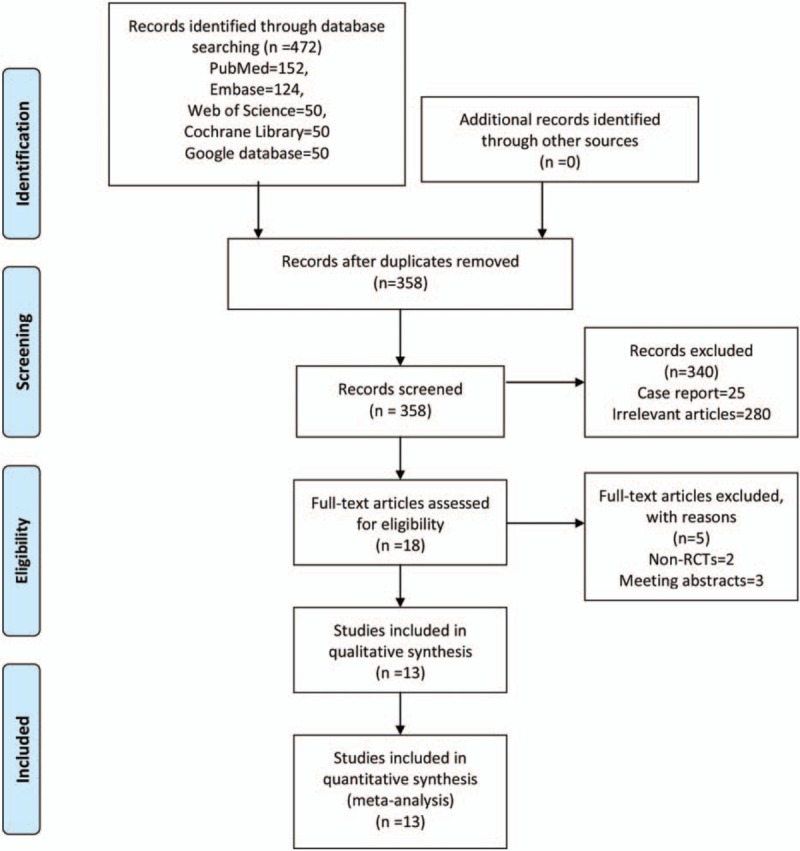

The literature search and selection process are illustrated in Fig. 1. The initial search yielded 472 articles; 358 papers were read after excluding the duplicates. Next, 340 papers were excluded based on the inclusion criteria. Five papers were then excluded as 2 were non-RCTs and 3 were meeting abstracts. Finally, we included 13 clinical studies with 821 patients for this meta-analysis.[6,9,17–27]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study search and inclusion criteria.

3.2. Study characteristics

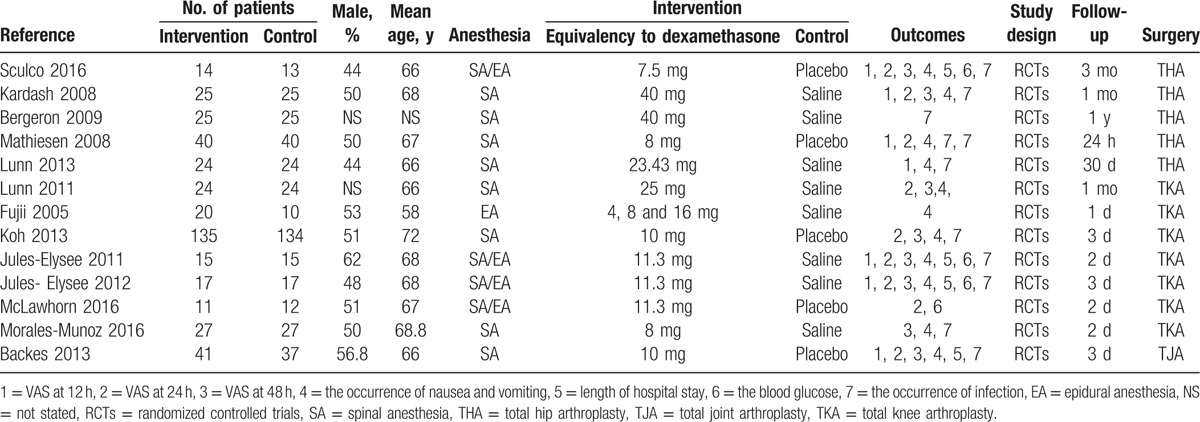

The detailed baseline characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Five studies were included in the meta-analysis. All articles were published in English between the years of 2008 and 2016. The sample sizes ranged from 13 to 40 (total = 821) and the mean age ranged from 58 to 72. The follow-up ranged from 1 day to 1 year. The glucocorticoid dose equivalency to dexamethasone ranged from 4 to 40 mg. Detailed information on the included patients is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The general characteristic of the included studies.

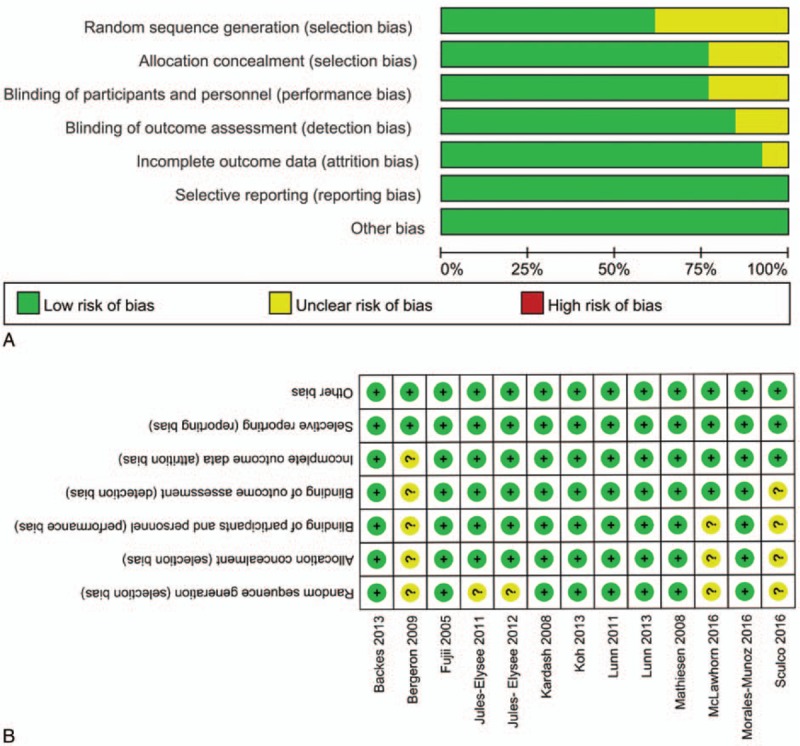

3.3. Risk of bias among the included studies

Figure 2 presents the details of the risk of bias assessment for all of the included studies. Randomized sequence generation was implemented adequately in 8 studies;[6,9,18,20–23,27] the other 5 studies had an unclear risk of bias. Allocation concealment was implemented adequately in all included studies.[6,9,18,20–23,27] All studies reported blinding of the participants, personnel, and outcome assessors.[6,9,17–27] The overall kappa value regarding the evaluation of risk of bias of included RCTs was 0.913, indicating an excellent degree of agreement between the 2 authors.

Figure 2.

A, The risk of bias graph. BA = risk of bias of included in randomized controlled trials. + = no bias, − = bias, ? = bias unknown. B, The risk of bias summary of the included studies.

3.4. Quality of evidence assessment

A summary of the quality of the evidence based on the GRADE approach is shown in Supplement S1. The GRADE level of evidence was high for VAS at 12 hours, the occurrence of PONV and the occurrence of infection, low for VAS at 24 hours, and the blood glucose level after surgery and very low for VAS at 24 hours.

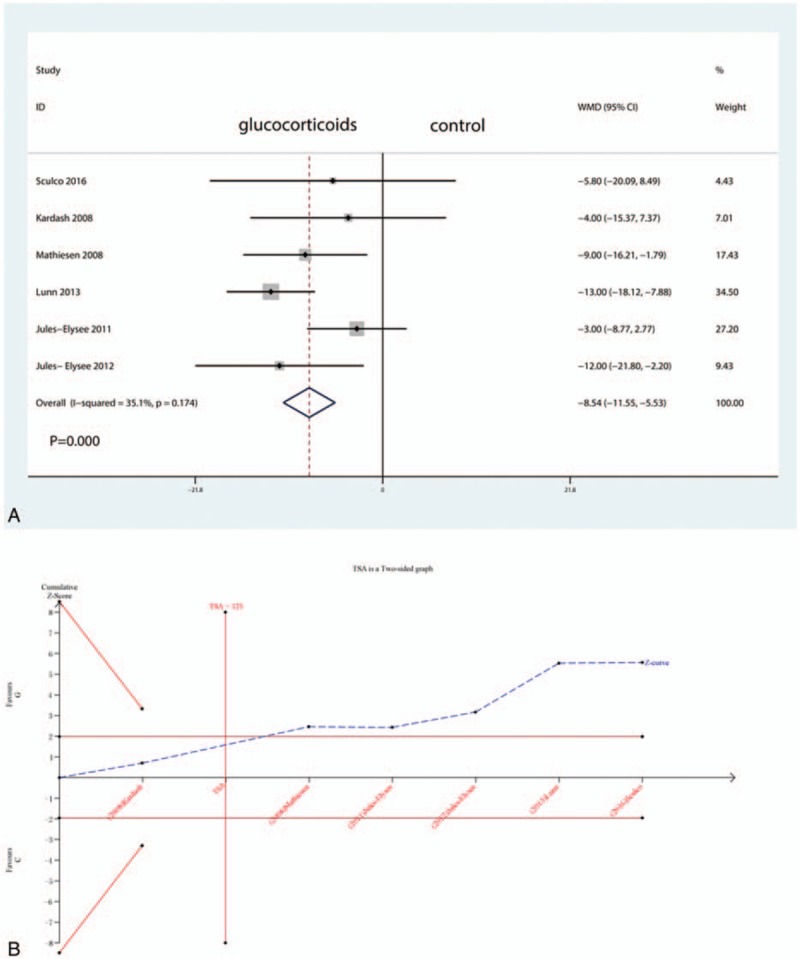

3.5. VAS at 12, 24, and 48 hours

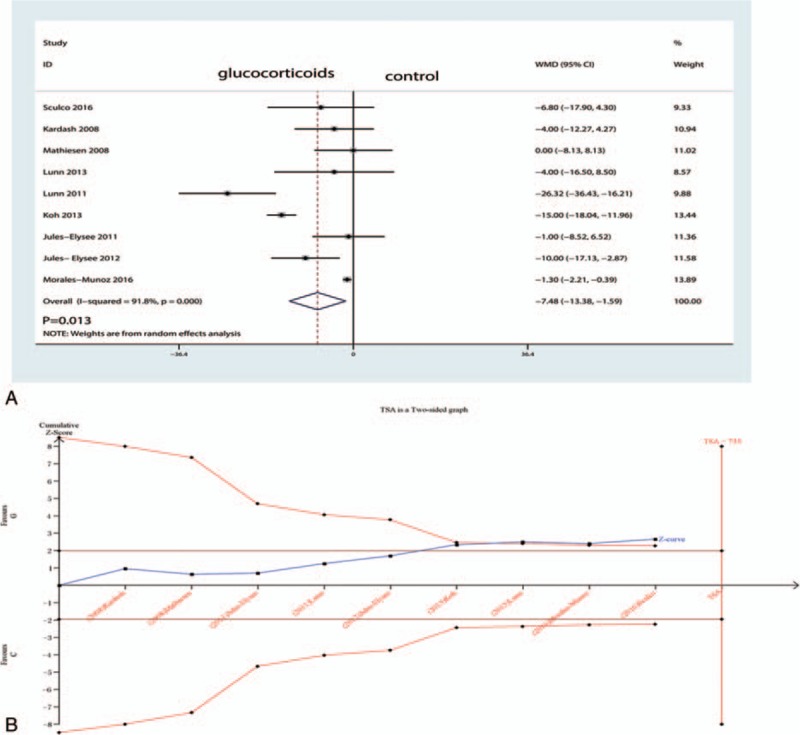

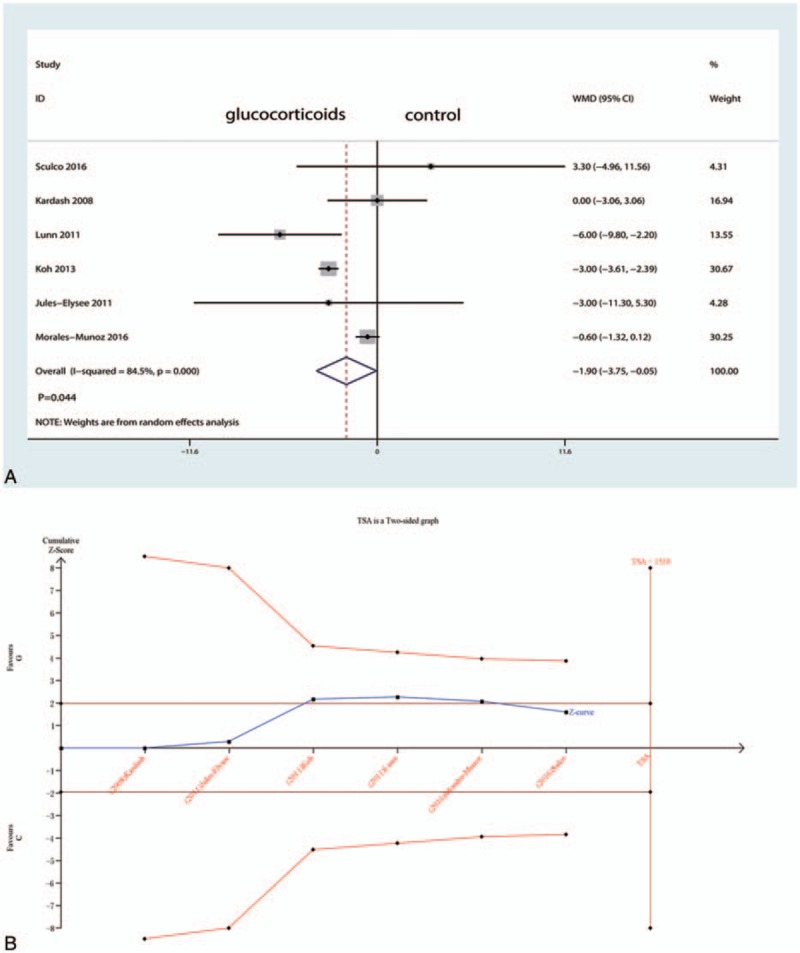

Six studies including 269 patients tested the effect of intravenous glucocorticoids on the VAS at 12 hours. Compared with the placebo, intravenous glucocorticoids were associated with a significant reduction in the VAS at 12 hours (WMD = −8.54, 95% CI −11.55 to −5.53, P = 0.000; I2 = 35.1%) (Fig. 3A). A TSA confirmed the pooled results at 12 hours (Fig. 3B). Nine studies reported data from 640 participants with TJA and were included in this meta-analysis to estimate the effect of intravenous glucocorticoids on the VAS at 24 hours. Compared with placebo, intravenous glucocorticoids were associated with a significant reduction in the VAS at 12 hours (WMD = −7.48, 95% CI −13.38 to −1.59, P = 0.013; I2 = 91.8%) (Fig. 4A). A TSA did not confirm the pooled results (Fig. 4B). Six trials (478 participants) were pooled to evaluate the efficacy of intravenous glucocorticoids on the VAS at 48 hours. Pooled data demonstrated that intravenous glucocorticoids significantly decreased the VAS at 48 hours (WMD = −1.90, 95% CI −3.75 to −0.05, P = 0.044; I2 = 84.5%) (Fig. 5A). A TSA did not confirm the pooled results (Fig. 5B).

Figure 3.

A, Forest plots of the included studies comparing the VAS at 12 h. B, A trial sequential analysis (TSA) showed that the pooled results (Z curve; blue lines) at all 3 time points crossed the conventional boundary of benefit (jacinth lines). VAS = visual analogue scale.

Figure 4.

A, Forest plots of the included studies comparing the VAS at 24 h. B, Z curve crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit (red curve) but did not reach the required sample size based on TSA (n = 735), entering the area of benefit (above the upper red line). TSA = trial sequence analysis, VAS = visual analogue scale.

Figure 5.

A, Forest plots of the included studies comparing the VAS at 48 h. B, Z curve crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit (red curve) but did not reach the required sample size based on TSA (n = 1510), entering the area of benefit (above the upper red line).

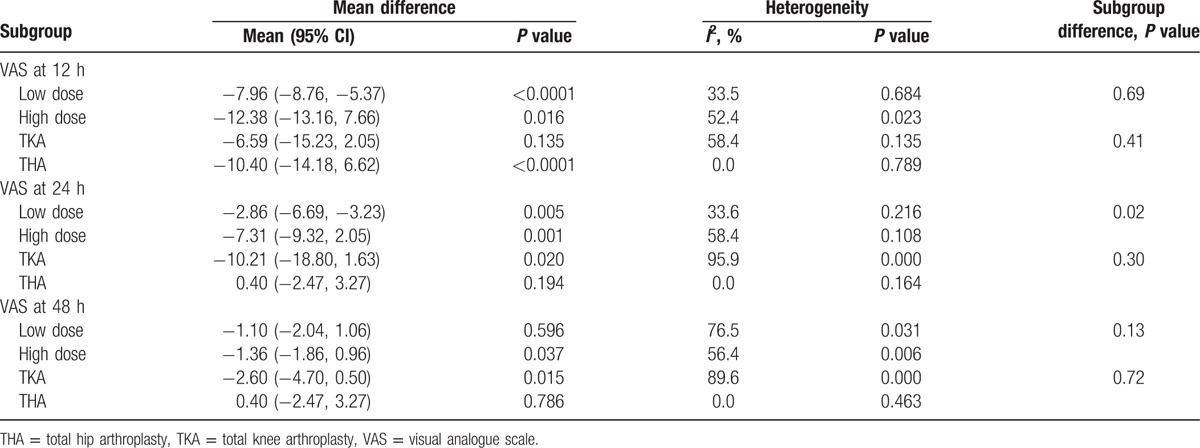

Subgroup analysis results are shown in Table 2. The results indicated that high-dose glucocorticoids (equivalency to dexamethasone >10 mg) are more effective than low-dose glucocorticoids (equivalency to dexamethasone <10 mg). There was no significant difference between TKA and THA.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the VAS at 12, 24, and 48 h.

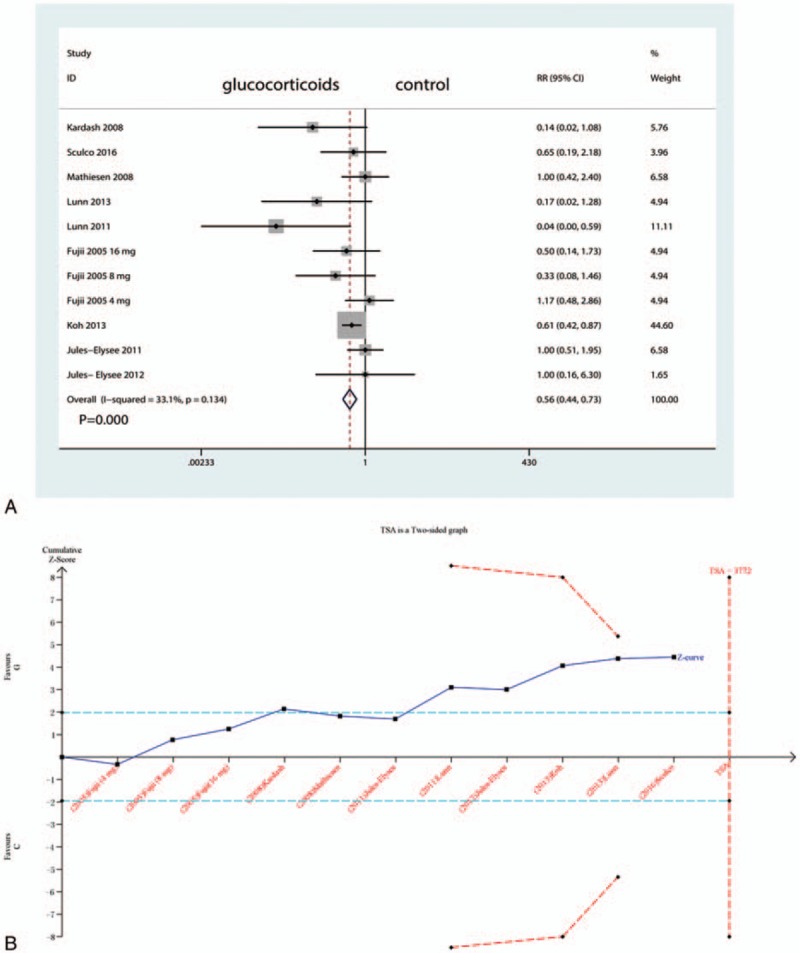

3.6. The occurrence of PONV

Four studies (501 participants) reported data on the occurrence of PONV. Compared with placebo, intravenous glucocorticoids significantly decreased the occurrence of PONV (RR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.44–0.73, P = 0.000; I2 = 33.1%) (Fig. 6A). A TSA did not confirm the pooled results (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

A, Forest plots of the included studies comparing the occurrence of PONV. PONV = postoperative nausea and vomiting; B, Z curve crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit (red curve) but did not reach the required sample size based on TSA (n = 1510), entering the area of benefit (above the upper red line).

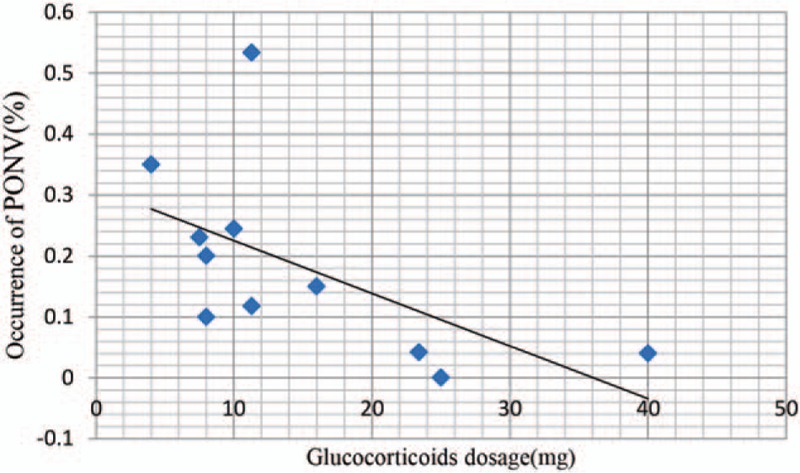

We plotted the glucocorticoid dose on the abscissa and the corresponding occurrence of PONV to generate a scatterplot. In addition, the linear correlation coefficient (r) was also calculated. A significantly positive correlation between the dosage of glucocorticoids and the occurrence of PONV was found (r = −0.835, P = 0.003; Fig. 7). The occurrence of PONV tended to decrease as the glucocorticoid dose increased.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the changing of glucocorticoid dose and the occurrence of PONV.

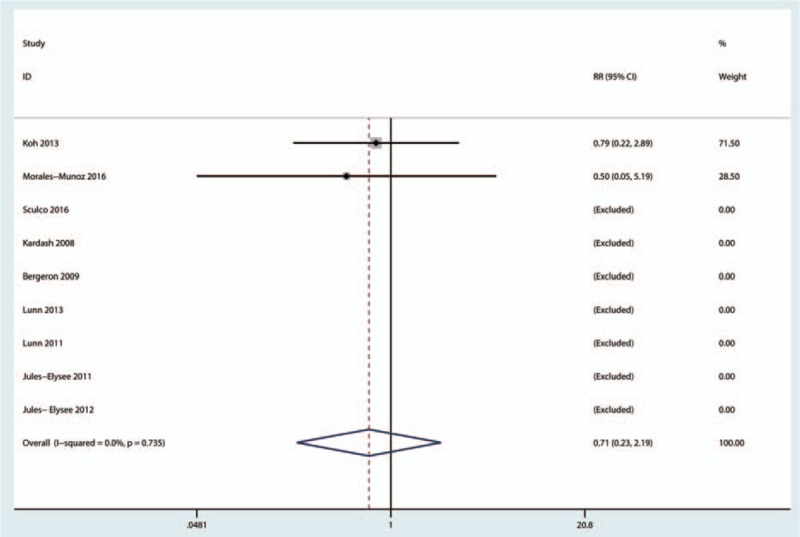

3.7. The occurrence of infection

Nine studies (460 participants) reported data on the occurrence of infection. Compared with placebo, intravenous glucocorticoids significantly decreased the occurrence of PONV (RR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.23–2.19, P = 0.106; I2 = 0.0%) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plots of the included studies comparing the occurrence of infection.

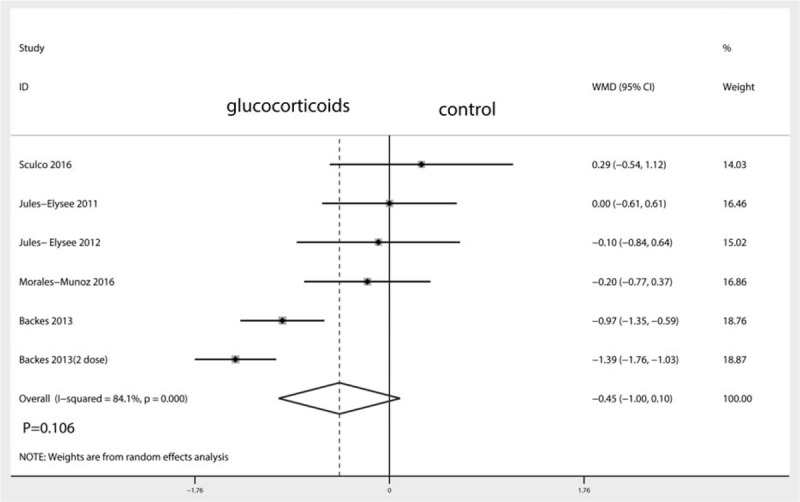

3.8. Length of hospital stay

A total of 6 studies (282 patients) were included in the meta-analysis of length of hospital stay. Compared with placebo, intravenous glucocorticoids were associated with a significantly decreased length of hospital stay (WMD = −0.45, 95% CI −1.00 to 0.10, P = 0.106; I2 = 84.1%) (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Forest plots of the included studies comparing the length of hospital stay.

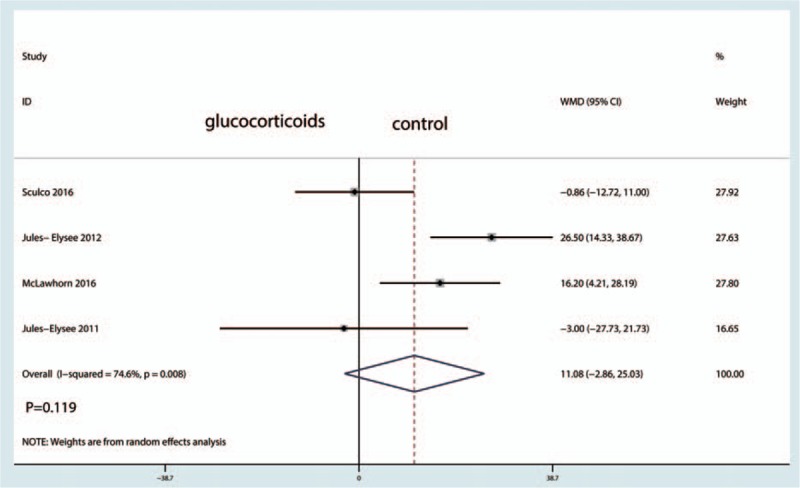

3.9. Blood glucose levels after surgery

A total of 4 studies (114 patients) were included in the meta-analysis of blood glucose levels after TJA. There was no significant difference between the blood glucose after TJA (WMD = 11.08, 95% CI −2.86 to 25.03, P = 0.119; I2 = 74.6%) (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Forest plots of the included studies comparing the blood glucose levels.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis and TSA on the effect of intravenous glucocorticoids for TJA. The pooled results showed that intravenous glucocorticoids are effective and safe for the short-term treatment of PONV and pain. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the length of hospital stay and the occurrence of infection. The TSA results showed that the pooled evidence was robust for VAS at 12 hours follow-up, but requires confirmation for VAS at 24 and 48 hours follow-up. The level of evidence, which was undermined by heterogeneity and/or study design limitations, was moderate or low, indicating that the degree of benefit must be studied, although the benefit is conclusive.

A major strength of the current analysis is the comprehensive search with strict statistical calculations. A previous review found that perioperative administration of glucocorticoids can decrease PONV after knee and hip surgeries.[28] However, a combined statistical analysis was not conducted. Moreover, studies with intra-articular glucocorticoids were also included and we did not acknowledge whether intravenous glucocorticoids can benefit TJA. Another meta-analysis indicated that perioperative doses of dexamethasone had small but statistically significant analgesic benefits.[29] The current meta-analysis included all available RCTs that included comparisons of efficacy and safety. A TSA was also performed to consolidate the results, overcoming the shortcomings of conventional meta-analyses. Results indicated that perioperative intravenous glucocorticoids in addition to multimodal anesthesia can decrease pain intensity and PONV after TJA. TSA results indicated that there is no need for further studies to determine the effects of glucocorticoids on VAS at 12 hours. Dexamethasone is commonly given intraoperatively at the time of anesthesia induction to reduce PONV.[30] De Oliveira Jr et al[31] revealed that dexamethasone at doses higher than 0.1 mg/kg is an effective adjunct in multimodal strategies to reduce postoperative pain and opioid consumption after surgery. For VAS at 24 and 48 hours, more trials will be necessary to determine the effects of intravenous glucocorticoids for reducing pain intensity and PONV.

For infection, there was no significant difference between the glucocorticoid and control groups (RR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.23–2.19, P = 0.106). Richardson et al[32] conducted a retrospective analysis of 6294 patients who underwent TJA and found that a single intravenous dexamethasone dose resulted in no statistically significant difference in the rate of infection after TJA. Toner et al[33] conducted a meta-analysis of 56 clinical trials, and the evidence did not find any safety concerns with respect to the use of perioperative glucocorticoids and subsequent infection, hyperglycemia, or other adverse outcomes. Waldron et al[29] revealed that blood glucose levels were higher at 24 hours in the glucocorticoid group than in the control group, with statistical significance. The present meta-analysis results indicated that intravenous glucocorticoids will not increase the blood glucose level compared with the control group. However, blood glucose alterations were specifically mentioned in only 4 trials; more trials should focus on this important side effect.

Our meta-analysis also has several potential limitations: patient treatment with different types and doses of glucocorticoids; marked heterogeneity among the included studies in VAS at 24 and 48 hours, reflecting the inconsistent benefit patients acquired from intravenous glucocorticoids, although these analyses were performed using a random effects model; and the follow-up in the included studies ranging from 1 day to 1 month after surgery. Thus, some adverse events may be underestimated. Finally, some data for comparisons were not originally available but were calculated by estimation, potentially leading to other bias.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis demonstrated that intravenous glucocorticoids can alleviate pain and reduce the incidence of PONV without sacrificing safety. Furthermore, the anti-emesis effects were dose-dependent. Considering the limitations of the current meta-analysis, the conclusions regarding infection and blood glucose levels should be interpreted cautiously; more RCTs are warranted before making final recommendations.

Acknowledgment

This work was financially supported by the bureau of traditional Chinese medicine Foundation of Guangdong province (20141102, 2014kt1180).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CENTRAL = Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CI = confidence interval, GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, PONV = postoperative nausea and vomiting, PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses, RCTs = randomized controlled trials, RR = risk ratios, THA = total hip arthroplasty, TJA = total joint arthroplasty, TKA = total knee arthroplasty, TSA = trial sequence analysis, VAS = visual analogue scale, WMD = weighted mean difference.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].DiIorio TM, Sharkey PF, Hewitt AM, et al. Antiemesis after total joint arthroplasty: does a single preoperative dose of aprepitant reduce nausea and vomiting? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2405–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, et al. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology 1999;91:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen JJ, Frame DG, White TJ. Efficacy of ondansetron and prochlorperazine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after total hip replacement or total knee replacement procedures: a randomized, double-blind, comparative trial. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:2124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Salerno A, Hermann R. Efficacy and safety of steroid use for postoperative pain relief. Update and review of the medical literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].White PF. Multimodal analgesia: its role in preventing postoperative pain. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2008;9:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Backes JR, Bentley JC, Politi JR, et al. Dexamethasone reduces length of hospitalization and improves postoperative pain and nausea after total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2013;28(8 suppl):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Higgins JPT, G. S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. 2011. Available at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lunn TH, Kristensen BB, Andersen LO, et al. Effect of high-dose preoperative methylprednisolone on pain and recovery after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thorlund K, Devereaux PJ, Wetterslev J, et al. Can trial sequential monitoring boundaries reduce spurious inferences from meta-analyses? Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:276–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thorlund K, Imberger G, Walsh M, et al. The number of patients and events required to limit the risk of overestimation of intervention effects in meta-analysis—a simulation study. PLoS One 2011;6:e25491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C, et al. Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brok J, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, et al. Apparently conclusive meta-analyses may be inconclusive—Trial sequential analysis adjustment of random error risk due to repetitive testing of accumulating data in apparently conclusive neonatal meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:287–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sculco PK, McLawhorn AS, Desai N, et al. The effect of perioperative corticosteroids in total hip arthroplasty: a prospective double-blind placebo controlled pilot study. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:1208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kardash KJ, Sarrazin F, Tessler MJ, et al. Single-dose dexamethasone reduces dynamic pain after total hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2008;106:1253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bergeron SG, Kardash KJ, Huk OL, et al. Perioperative dexamethasone does not affect functional outcome in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mathiesen O, Jacobsen LS, Holm HE, et al. Pregabalin and dexamethasone for postoperative pain control: a randomized controlled study in hip arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lunn TH, Andersen LO, Kristensen BB, et al. Effect of high-dose preoperative methylprednisolone on recovery after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fujii Y, Nakayama M. Effects of dexamethasone in preventing postoperative emetic symptoms after total knee replacement surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial in adult Japanese patients. Clin Ther 2005;27:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Koh IJ, Chang CB, Lee JH, et al. Preemptive low-dose dexamethasone reduces postoperative emesis and pain after TKA: a randomized controlled study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:3010–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jules-Elysee KM, Lipnitsky JY, Patel N, et al. Use of low-dose steroids in decreasing cytokine release during bilateral total knee replacement. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011;36:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jules- Elysee KM, Wilfred SE, Memtsoudis SG, et al. Steroid modulation of cytokine release and desmosine levels in bilateral total knee replacement: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:2120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McLawhorn AS, Beathe J, YaDeau J, et al. Effects of steroids on thrombogenic markers in patients undergoing unilateral total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Res 2015;33:412–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Morales-Munoz C, Sanchez-Ramos JL, Diaz-Lara MD, et al. Analgesic effect of a single-dose of perineural dexamethasone on ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block after total knee replacement. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2017;64:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lunn TH, Kehlet H. Perioperative glucocorticoids in hip and knee surgery—benefit vs. harm? A review of randomized clinical trials. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57:823–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Waldron NH, Jones CA, Gan TJ, et al. Impact of perioperative dexamethasone on postoperative analgesia and side-effects: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gan TJ, Meyer TA, Apfel CC, et al. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2007;105:1615–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].De Oliveira GS, Jr, Almeida MD, Benzon HT, et al. Perioperative single dose systemic dexamethasone for postoperative pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 2011;115:575–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Richardson AB, Bala A, Wellman SS, et al. Perioperative dexamethasone administration does not increase the incidence of postoperative infection in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a retrospective analysis. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:1784–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Toner AJ, Ganeshanathan V, Chan MT, et al. Safety of perioperative glucocorticoids in elective noncardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2017;126:234–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.