Abstract

Pancreatic ribonuclease (RNASE1) is a digestive enzyme that has been one of the key models in studies of evolutionary innovation and functional diversification. It has been believed that the RNASE1 gene duplications are correlated with the plant-feeding adaptation of foregut-fermenting herbivores. Here, we characterized RNASE1 genes from Caniformia, which has a simple digestive system and lacks microbial digestion typical of herbivores, in an unprecedented scope based on both gene sequence and tissue expression analyses. Remarkably, the results yielded new hypotheses regarding the evolution and the function of Caniformia RNASE1 genes. Four independent gene duplication events in the families of superfamily Musteloidea, including Procyonidae, Ailuridae, Mephitidae and Mustelidae, were recovered, rejecting previous Mustelidae-specific duplication hypothesis, but supporting Musteloidea duplication hypothesis. Moreover, our analyses revealed pronounced differences among the RNASE1 gene copies regarding their selection pressures, pI values and tissue expression patterns, suggesting the differences in their physiological functions. Notably, the expression analyses detected the transcription of a RNASE1 pseudogene in several tissues, raising the possibility that pseudogenes are also a potential source during the RNase functional diversification. In sum, the present work demonstrated a far more complex and intriguing evolutionary pattern and functional diversity of mammalian ribonuclease than previously thought.

As the prototype of the mammalian ribonuclease superfamily, pancreatic ribonuclease (RNASE1) is a digestive enzyme that has been one of the key models in studies of evolutionary innovation and functional diversification. The RNASE1 gene has been thoroughly investigated in many mammalian herbivores having multicompartmentalized stomachs, like ruminants (e.g. ox, sheep and camel)1,2,3,4,5,6,7, and species with ruminant-like or cecal digestions (e.g. leaf-eating colobines and elephants)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Whereas other mammalian species contain only a single RNASE1 gene, these herbivorous species harbor multiple RNASE1 genes resulting from gene duplication, which are thought to be an adaptive response to increased demands for the enzyme for digesting bacterial RNA from the gut microflora5,6,7,8,9,13,14.

Interestingly, the RNASE1 gene was recently found to duplicate in three species of Mustelidae family in Caniformia (dog-like carnivores), which has a simple digestive system and lacks microbial digestion in the rumen or cecum typical of herbivores16, leading to the prediction that new tissue specificity or functions of RNASE1 genes might have developed in these species. The Caniformia RNASE1 genes thus provided an attractive study model for understanding the evolutionary and functional novelty of the RNases in mammals.

In the present study, we characterized 94 complete protein-coding RNASE1 gene sequences from 34 species representing 8 Caniformia families, and performed both gene sequence and tissue expression analyses to elucidate the exact origin of multiple RNASE1 genes in Caniformia and to validate whether these genes have evolved new functions and what these functions might be. Remarkably, our analyses identified independent gene duplications in four families of Musteloidea, including Procyonidae, Ailuridae, Mephitidae and Mustelidae, rejecting the Mustelidae-specific duplication hypothesis, but supporting the Musteloidea duplication hypothesis. In addition, our analyses revealed the pronounced differences among the RNASE1 gene copies regarding their selection pressures, pI values and tissue expression patterns, with the finding that the highest expressions for the newly duplicated genes in the pancreas, the lung, the spleen and the muscle, in comparison with those for the original genes in the guts. Notably, the expression analyses detected the transcription of a RNASE1 pseudogene in several tissues, raising the possibility that pseudogenes are also a potential source during the RNase functional diversification. In sum, the present work demonstrated a far more complex and intriguing evolutionary pattern and functional diversity of mammalian ribonuclease than previously thought.

Results

Caniformia RNASE1 Sequences

A total of 94 RNASE1 sequences with complete protein-coding region (456 bp) were identified from 34 caniformian species examined, including 3 canids (dogs), ursids (bears), the red panda, 1 procyonid (raccoons), 21 mustelids (weasels), 1 mephitid (skunks), 2 otariids (sea lions), and 1 phocid (true seals) (Table 1). Among these sequences, 12 of the open reading frames (ORFs) are interrupted by premature stop codons and thus are regarded as pseudogenes. The canids, ursids, otariids, and phocids all have a single RNASE1 gene, whereas the procyonids, the red panda, mephitids and all 21 mustelids had multiple gene copies, ranging from 2 (procyonids, the red panda, Gulo gulo, Martes americana, and Melogale moschata) to 5 (Mustela frenata, Mustela putorius, Mustela sibirica and Martes flavigula) (Table 1). From this, it can be seen that there is an apparent gene expansion in the Musteloidea, a superfamily of Caniformia that includes families Procyonidae, Mustelidae, Ailuridae and Mephitinae, especially typical in Mustelidae, in contrast with those in non-Musteloidea caniformians.

Table 1. Species examined in this study and their RNASE1 genes [a Gene numbers (putative functional genes/pseudogenes)].

| Family | Subfamily | Scientific name | Common name | Sample source | Gene numbersa | GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mustelidae (weasels) | Mustelinae | Mustela sibirica | Himalayan weasel | China | 5(3/2) | KC884989-KC884993 |

| Mustela putorius | Polecat | IRTA, Spain | 5(3/2) | KC884962-KC884966 | ||

| Mustela nivalis | Least weasel | CGRB*, South Korea | 4(3/1) | KC885002-KC885005 | ||

| Mustela kathiah | Yellow-bellied weasel | Yunnan Province,China | 4(4/0) | KC884998-KC885001 | ||

| Mustela frenata | Long-tailed weasel | Royal Ontario Museum, Canada | 5(5/0) | KC885030-KC885034 | ||

| Mustela vison | American mink | Royal Ontario Museum, Canada | 4(4/0) | KC884974-KC884977 | ||

| Mustela lutreola | European mink | IRTA, Spain | 4(3/1) | KC884958-KC884961 | ||

| Mustela erminea | Ermine | IRTA, Spain | 3(3/0) | KC884978-KC884980 | ||

| Mustela altaica | Mountain weasel | IRTA, Spain | 4(3/1) | KC884954-KC884957 | ||

| Martinae | Martes zibellina | Sable | Neimenggu Province,China | 4(4/0) | KC884994-KC884997 | |

| Martes americana | American marten | Royal Ontario Museum, Canada | 2(2/0) | KC885025-KC885026 | ||

| Martes foina | Stone Marten | China | 4(4/0) | KC884985-KC884988 | ||

| Martes flavigula | Yellow-throated marten | Kunming Zoo,China | 5(4/1) | KC885006-KC885010 | ||

| Martes pennanti | Fisher | Royal Ontario Museum, Canada | 3(3/0) | KC885027-KC885029 | ||

| Martes martes | Pine marten | IRTA, Spain | 3(3/0) | KC884982-KC884984 | ||

| Gulo gulo | Wolverine | Royal Ontario Museum, Canada | 2(2/0) | KC885023-KC885024 | ||

| Helictidinae | Melogale moschata | Chinese Ferret-Badger | Yunnan Province,China | 2(2/0) | KC885021-KC885022 | |

| Lutrinae | Lutra lutra | Common otter | CGRB*, South Korea | 3(2/1) | KC885018-KC885020 | |

| Enhydra lutris | Sea otter | IRTA, Spain | 4(4/0) | KC884967-KC884970 | ||

| Melinae | Meles meles | European badger | CGRB*, South Korea | 3(3/0) | KC885015-KC885017 | |

| Arctonyx collaris | Hog badger | Yunnan Province,China | 4(3/1) | KC885011-KC885014 | ||

| Procyonidae (raccoons) | Potos flavus | Kinkajou | San Diego Zoo, USA | 2(2/0) | KC885035-KC885036 | |

| Mephitidae (skunks) | Spilogale putorius | Eastern Spotted Skunk | IRTA, Spain | 3(1/2) | KC884971-KC884973 | |

| Ailuridae (the red panda) | Ailurus fulgens | Red Panda | Kunming Zoo,China | 2(2/0) | KC885037-KC885038 | |

| Otaeiidae (sea lions) | Zalophus californianus | California sea lion | Qingdao, Shandong Province, China | 1(1/0) | KC885040 | |

| Callorhinus ursinus | Northern fur seal | Qingdao, Shandong Province, China | 1(1/0) | KC885039 | ||

| Phocidae (true seals) | Phoca vitulina | Harbor seal | Qingdao, Shandong Province, China | 1(1/0) | KC885044 | |

| Ursidae (bears) | Tremarctos ornatus | Spectacled bear | San Diego Zoo, USA | 1(1/0) | KC885041 | |

| Ursus thibetanus | Asiatic black bear | Yunnan Province,China | 1(1/0) | KC885042 | ||

| Ursus maritimus | Polar bear | downloaded from public database | 1(1/0) | KC885048 | ||

| Ailuropoda melanoleuca | Giant panda | Sichuan Province,China | 1(1/0) | KC885043 | ||

| Canidae (dogs) | Canis lupus | Grey wolf | Haerbing, China | 1(1/0) | KC885047 | |

| Canis rufus | Red wolf | Russia | 1(1/0) | KC885046 | ||

| Canis familiaris | Dog | downloaded from public database | 1(1/0) | KC885045 |

We next calculated the numbers of amino acid residue differences between the functional paralogous genes in the Musteloidea species, except for Spilogale putorius (mephitids), which has only one putative functional gene. The amino acid residue differences between the paralogs is 9 in Potos flavus (procyonids), 7 in Ailurus fulgens (the red panda), and 24 in mustelids on average (ranging from 13 in Gulo gulo to 31 in Mustela sibirica). Therefore, they most likely represent distinct genes derived from gene duplications, rather than alleles of a single gene.

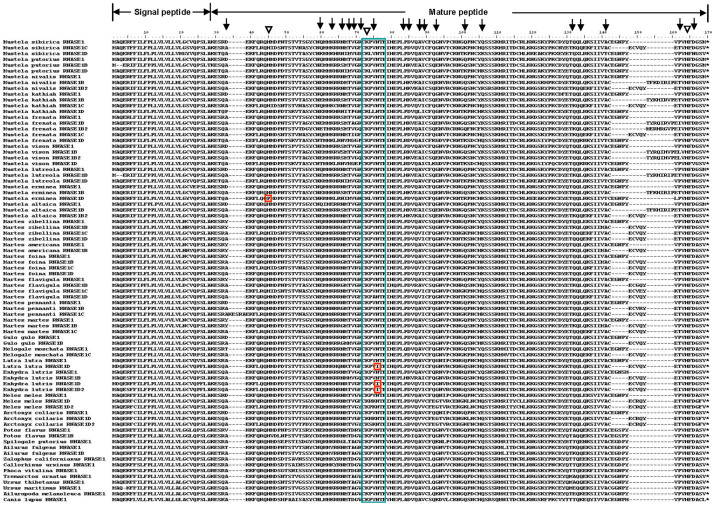

The nucleotide sequence alignment of all the 94 RNASE1 sequences is 514 bp in length and includes the coding regions for the complete signal peptide (1–84 bp) and the mature peptide (85–514 bp). The protein alignment of 82 putative functional RNASE1 sequences is 170 aa (Figure 1). Almost all of these sequences have the RNase A superfamily signature motif: catalytic triad (H12-K41-His119, numbers according to human RNase 1 of the mature peptide) that is required for ribonuclease activity and CKXXNTF which includes the catalytic lysine residue K4117,18. It should be noted, however, that the histidine (H12) in the catalytic triad is replaced by a proline (P12) in a duplicated gene (RNASE1D) of Mustela erminea, and the asparagine (N) in the signature motif CKXXNTF is replaced by an isoleucine (I) in two duplicated genes (RNASE1D and RNASE1D2) of Enhydra lutris and a duplicated gene (RNASE1D) of Lutra lutra (Figure 1). The asparagine residue N45 has been thought to be involved in the catalytic mechanism of RNase A superfamily17,18. Interestingly, previous studies of the RNase A superfamily found that RNASE 9–13, which exhibited diverse expression patters and may have acquired novel functions related to male reproduction, are variable at these sites of the superfamily signature motif, and moreover, their isoelectric points (pIs) are lower than those of the other RNASE members18. The observed sequence variations in these four duplicated RNASE1 genes (M. erminea RNASE1D, E. lutris RNASE1D, E. lutris RNASE1D2, and L. lutra RNASE1D) suggest that they may not possess ribonucleolytic or antibacterial activities, but have acquired novel functions. Their lower pIs than the other RNASE1 paralogs (8.147 for M. erminea RNASE1D vs. 8.405–9.214 for other M. erminea RNASE1s; 7.859 for E. lutris RNASE1D2 and 8.179 for E. lutris RNASE1D vs. 8.476–8.769 for other E. lutris RNASE1s; 7.682 for L. lutra RNASE1D vs. 8.586 for L. lutra RNASE1A) also support this hypothesis.

Figure 1. Amino acid alignment of 82 putative functional RNASE1 sequences.

The catalytic triad (H12-K41-His119) motif is indicated by the triangle. The CKXXNTF motif is highlighted by the blue box. Variable sites in these motifs are highlighted in the red box. Positively selected sites identified by PAML are indicated by the arrows.

Phylogenetic Inferences of Caniformia RNASE1 Genes

We generated similar phylogenetic tree topologies with (Supplementary Data 3) and without (Figure 2) the 12 pseudogenes. In addition, results from NJ and MP analyses were quite similar with the exception of a few weakly supported terminal branches. We show the NJ tree topologies here.

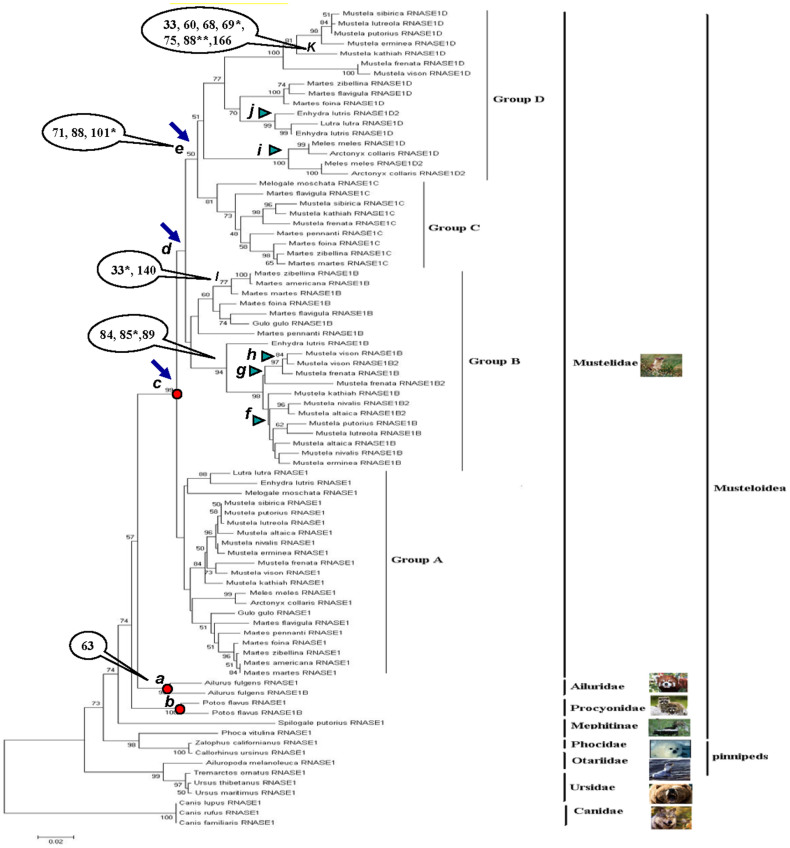

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of 82 putative functional RNASE1 sequences.

The phylogenetic tree was generated from NJ analysis. Gene duplication events are indicated. Positively selected branches and sites identified in branch-site model are indicated.

As seen from Supplementary Data 3b and Figures 2, Canidae diverged earliest, followed by Ursidae (NJ BS = 70% and 73%; MP BS = 68% and 70%) and then the pinnipeds (including Otariidae and Phocidae) (NJ BS = 85% and 74%; MP BS = 80% and 70%). Ailuridae, Procyonidae, Mustelidae, and Mephitinae form the monophyletic superfamily Musteloidea (NJ BS = 85% and 74%; MP BS = 80% and 70%). Within Musteloidea, Mephitidae separate first (NJ BS = 62% and 74%; MP BS = 60% and 69%), followed by Procyonidae (NJ BS = 52% and 57%; MP BS = 50% and 53%). Ailuridae and Mustelidae are sister-taxa (NJ BS = 52% and 57%; MP BS = 50% and 53%). These results are in a general agreement with the accepted phylogeny of Caniformia families (Supplementary Data 3a), except for the relationship among Procyonidae, Mustelidae and Ailuridae within Musteloidea19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Growing evidence has supported that Procyonidae and Mustelidae are sister-taxa, and Ailuridae was their closest relative22,23,26. In the present study, the clustering of Ailuridae and Mustelidae (with a low nodal support) is perhaps caused by the small number of nucleotides used.

Phylogenetic trees for the multiple RNASE1 sequences from Musteloidea show that they cluster by family-specific clusters with high nodal supports (NJ BS ≥ 99%; Supplementary Data 3b and Figures 2). This finding supports the conclusion that the gene duplication arose after the Musteloidea speciation and four independent gene duplication events took place in Ailuridae, Procyonidae, Mustelidae, and Mephitinae (four red circles in Supplementary Data 3b). Hence, our study not only found gene duplication events in four families of Musteloidea, but also favored independent duplication patterns in these four families, providing a new evolutionary scenario for RNASE1 genes in Caniformia.

In addition to identifying four independent duplication events in the families of Musteloidea, our phylogenetic analyses reveal a far more complex evolutionary pattern within Mustelidae than the other three families of Musteloidea. While only one or two gene duplication and pseudogenization events are observed in the other three families of Musteloidea (Supplementary Data 3b), 77 RNASE1 sequences are identified in Mustelidae (67 putative functional gene sequences and 10 pseudogenes) and they are consistently divided into four gene groups via three early duplication events (three blue arrows in Supplementary Data 3b and Figures 2). We named the four gene groups as Groups A–D (Group A: NJ BS = 45% and MP BS = 44%; Group B: NJ BS = 48% and MP BS = 43%; Group C: NJ BS = 81% and MP BS = 75%; Group D: NJ BS = 51% and MP BS = 50%). The phylogeny without the pseudogenes agrees with this duplication pattern (Figure 3) (Group A: NJ BS = 46% and MP BS = 43%; Group B: NJ BS = 47% and MP BS = 44%; Group C: NJ BS = 82% and MP BS = 77%; Group D: NJ BS = 50% and MP BS = 50%). In addition, within these four gene groups, at least eight additional recent and lineage-specific duplication events (five green triangles in Supplementary Data 3b and Figure 2) and pseudogenization events (three yellow diamonds in Figure 2) took place.

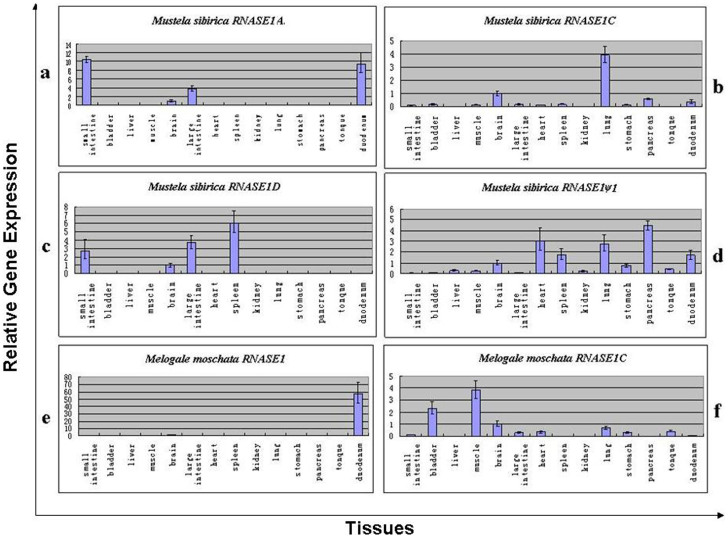

Figure 3. Relative mRNA expression levels in the 14 tissues for each RNASE1 gene copy of Mustela sibirica and Melogale moschata.

The level of expression is normalized to brain tissue.

Evolutionary Rates and Selective Patterns in Musteloidea

To test whether the RNASE1 genes have evolved at different rates between Musteloidea and the other Caniformia families, we first performed RRTREE analyses using all 94 sequences, with Canidae RNASE1 sequences used as the outgroups (Table 2). The results of these analyses indicate that the substitution rate of Musteloidea was significantly higher than those of both pinnipeds (including families Otariidae and Phocidae) and Ursidae (P = 0.014008 and P = 0.016164, respectively). When the tests were conducted within Musteloidea, the family Mustelidae was found to evolve significantly faster than both pinnipeds (p = 0.013945) and Ursidae (P = 0.016111) (Table 2). By comparing group A–D of Mustelidae family with other Caniformia families, we found that groups B and D significantly rejected the hypothesis of equal rates (Table 2).

Table 2. Heterogeneity in the substitution rates and nonsynonymous rates of evolution of RNASE1 genes in Musteloidea as indicated in the two-cluster test of RRTREE.

| Comparisons of substitution rates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| outgroup | lineage 1 | lineage 2 | rate1 | rate2 | P value | |

| Musteloidea vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Musteloidea | pinnipeds | 0.252279 | 0.208385 | 0.014008 |

| Canidae | Musteloidea | Ursidae | 0.254481 | 0.206313 | 0.016164 | |

| Families in Musteloidea vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Mustelidae | pinnipeds | 0.250786 | 0.206074 | 0.013945 |

| Canidae | Mustelidae | Ursidae | 0.252951 | 0.204029 | 0.016111 | |

| Gene Groups in Mustelidae vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Group B | pinnipeds | 0.255294 | 0.206487 | 0.018824 |

| Canidae | Group B | Ursidae | 0.257445 | 0.204581 | 0.018158 | |

| Canidae | Group D | pinnipeds | 0.287246 | 0.209285 | 0.000126 | |

| Canidae | Group D | Ursidae | 0.289685 | 0.204581 | 0.000203 | |

| Comparisons of nonsynonymous substitution rates | ||||||

| Musteloidea vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Musteloidea | pinnipeds | 0.216563 | 0.168543 | 0.017631 |

| Canidae | Musteloidea | Ursidae | 0.218565 | 0.170468 | 0.01113 | |

| Families in Musteloidea vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Mustelidae | pinnipeds | 0.219085 | 0.168543 | 0.014985 |

| Canidae | Mustelidae | Ursidae | 0.221114 | 0.170468 | 0.009617 | |

| Gene Groups in Mustelidae vs. the other Caniformia families | Canidae | Group B | pinnipeds | 0.211949 | 0.164206 | 0.037993 |

| Canidae | Group B | Ursidae | 0.212627 | 0.166028 | 0.027826 | |

| Canidae | Group D | pinnipeds | 0.255057 | 0.164665 | 0.000175 | |

| Canidae | Group D | Ursidae | 0.258944 | 0.166524 | 0.000119 | |

| Wea-2 | Bad-3 | 0.0986609 | 0.193321 | 0.00051856 | ||

| Wea-1 | Bad-2 | 0.0682123 | 0.150043 | 0.00021178 | ||

| Wea-1 | Wea-3 | 0.0682123 | 0.152802 | 0.00032555 |

When the substitution rates are divided into nonsynonymous and synonymous rates using 82 putative functional sequences, the synonymous rates were found to be similar (P > 0.05), whereas the nonsynonymous rates show significant differences (P < 0.05) (Table 2). This suggests that the rate differences observed above are due to a difference in amino-acid substitutions rates, which are most likely to associate with the changes in selective pressures.

To examine whether the accelerated RNASE1 nonsynonymous substitution rates in Musteloidea were produced by the action of positive selection, we performed codon-based maximum likelihood (CODEML) analyses using the NJ tree topology shown in Figure 2, with the exception of clustering Procyonidae with Mustelidae and placing Ailuridae as their sister-group, which are more consistent with the generally accepted relationships22,23,26. Canidae is used for rooting. Ambiguous sites are not considered (cleandata = yes in the CODEML analyses). Considering that CODEML analyses may be sensitive to the tree topology employed, we also conducted the analyses using the MP tree topology and obtained similar results.

As summarized in Table 3, the free-ratio model, M1, revealed a significantly better fit to the data than did the one-ratio model, M0 (P < 0.05), suggesting that these RNASE1 genes are likely subject to different selection pressures. To examine whether any site in RNASE1 have been positively selected, we performed the LRT test by comparing site models. The positive-selection model (M8) provided a significantly better fit to the data than did the neutral model (M8a) (P < 0.0001). The Bayes empirical Bayes (BEB) analysis identified 10 positively selected sites, 6 of which (alignment positions 60, 66, 71, 93, 134, and 162 in Figure 1) had PPs > 0.95.

Table 3. CODEML analyses of the selective pattern for RNASE1 genes in Musteloidea.

| Models | lnL | Parameter Estimates | 2ΔL | Positively Selected Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branch-specific models | ||||

| one-ratio | −5329.391141 | ω = 0.41926 | ||

| free-ratio | −5227.477635 | 203.827015 (P < 0.05) | ||

| Site-specific models | ||||

| M8a | −5163.344606 | p0 = 0.75820 p = 0.89566 q = 3.50973 p1 = 0.24180 ω = 1 | Not allowed | |

| M8 | −5137.931076 | p0 = 0.91880 p = 0.55837 q = 1.00253 p1 = 0.08120 ω = 2.87333 | 50.82706 (P < 0.0001) | 60 (0.950)* 66* (0.988) 69 (0.889) 71**(1.000) 84 (0.573) 93** (0.999) 106 (0.918) 132 (0.830) 134** (0.999) 162* (0.959) |

| Branch-site models | ||||

| Branch a | ||||

| M1a | −5175.657635 | p0 = 0.64638 p1 = 0.33023 p2 = 0.02339 ω0 = 0.15077 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 1 | ||

| Model A | −5173.723937 | p0 = 0.66160 p1 = 0.32765 p2 = 0.01075 ω0 = 0.15175 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 44.42402 | 3.867396 (P < 0.05) | 63 (0.904) |

| Branch e | ||||

| M1a | −5174.986245 | p0 = 0 p1 = 0 p2 = 1 ω0 = 0.14937 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 1 | ||

| Model A | −5167.787006 | p0 = 0.64646 p1 = 0.33130 p2 = 0.02225 ω0 = 0.14957 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 999 | 14.398478 (P < 0.001) | 71 (0.839) 88 (0.930) 101* (0.950) |

| Branch k | ||||

| M1a | −5174.401326 | p0 = 0.4445 p1 = 0.22528 p2 = 0.33027 ω0 = 0.14828 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 1 | ||

| Model A | −5167.599321 | p0 = 0.63957 p1 = 0.32576 p2 = 0.03467 ω0 = 0.14855 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 345.77645 | 13.60401 (P < 0.001) | 33 (0.782) 60 (0.519) 68 (0.607) 69* (0.953) 75 (0.946) 88** (0.992) 166 (0.626) |

| Branch l | ||||

| M1a | −5175.672508 | p0 = 0.65987 p1 = 0.34013 p2 = 0 ω0 = 0.15048 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 1 | ||

| Model A | −5172.23885 | p0 = 0.64423 p1 = 0.33515 p2 = 0.02063 ω0 = 0.15089 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 999 | 6.867316 (P < 0.01) | 33* (0.960) 140 (0.607) |

| Branch m | ||||

| M1a | −5174.98074 | p0 = 0.57216 p1 = 0.29299 p2 = 0.13485 ω0 = 0.14860 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 1 | ||

| Model A | −5171.131265 | p0 = 0.64900 p1 = 0.33292 p2 = 0.01808 ω0 = 0.14879 ω1 = 1 ω2 = 122.45606 | 7.69895 (P < 0.01) | 84 (0.641) 85* (0.976) 89 (0.655) |

We further tested the presence of positive selection and adaptive sites in the Musteloidea RNASE1 sequences using LRTs based on the branch-site models (Table 3). We first examined those branches leading to the gene duplication events in Ailuridae (branch a in Figure 2), Procyonidae (branch b in Figure 2), and Mustelidae (branch c-j in Figure 2) separately. Interestingly, we detected signals for positive selection in branch a (p < 0.05), which produced two RNASE1 gene copies in Ailuridae, and branch e (p < 0.001), which gave rise to Group C and Group D in Mustelidae (Table 3). Residue 63 was detected as a positively selected site along branch a, while residues 71, 88, and 101 were positively selected sites along branch e, in which residue 101 had PPs > 0.95 (indicated in Figure 1 and 2). After performing Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, the LRT tests are still significant in branch e. Similarly, we also tested those branches of the duplicated gene copies using the branch-site model. The analyses suggest that there is significant evidence of positive selection acting along the terminal branch to one of the duplicated genes (RNASE1D) from Mustela kathiah in Group D (branch k; P < 0.001), and the ancestral branch to the duplicated genes (RNASE1B) from three species of the Martes genus in Group B (branch l, P < 0.001), as well as the ancestral branch to the Group B genes of the Mustelinae and Lutrinae subfamilies species (branch m, P < 0.01). The BEB analysis identified 7 positively selected sites along branch k, 2 of which (alignment positions 69 and 88) were predicated with PPs > 0.95, and identified 2 positively selected sites along branch l, 1 of which (alignment position 33) were predicated with PPs > 0.95, as well as 3 positively selected sites along branch m, 1 of which (alignment position 85) were predicated with PPs > 0.95 (Figure 1 and 2). After performing the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, the LRT tests were still significant.

Differences in Tissue Expression Patterns among RNASE1 gene copies

It is known that duplicated genes evolving under positive selection often show functional divergence from the original genes. This prompted us to investigate the possibility of functional divergence caused by RNASE1 gene duplications by characterizing the tissue expression patterns of the RNASE1 gene copies in two mustelidae representatives, Mustela sibirica and Melogale moschata.

Through amplifying and sequencing RNASE1 cDNAs, we found that four of five RNASE1 genes from Mustela sibirica are expressed, including three putative functional genes (RNASE1A, RNASE1C and RNASE1D) and one pseudogene (RNASE1Bψ1). For Melogale moschata, both putative functional RNASE1 genes (RNASE1A and RNASE1C) are expressed.

Figure 3 shows the relative mRNA expression levels in 14 tissues for each RNASE1 gene copy in the two species studied. The level of expression is normalized to brain tissue. Overall, we found that, for both species, the expression pattern varies considerably among the RNASE1 gene copies. Among the three putative functional RNASE1 genes in Mustela sibirica (Supplementary Data 3b), RNASE1A is expressed in the small intestine, the large intestine and the duodenum (Figure 3a), whereas RNASE1C has the highest expression in the lung (Figure 3b) and RNASE1D is detected in the spleen with the highest expression level (Figure 3c). By contrast, the pseudogene, i.e., RNASE1Bψ, is expressed highest in the pancreas and the heart (Figure 3d). For the two putative functional RNASE1 genes in Melogale moschata (Supplementary Data 3b), the expression of RNASE1A was significantly higher in duodenum than in other tissues (Figure 3e), whereas RNASE1C has the highest expression in the muscle (Figure 3f).

Discussion

In the present study, we identified and characterized new RNASE1 gene sequences from Caniformia in an unprecedented scope based on both gene sequence and tissue expression analyses, which yielded a new hypothesis regarding the evolution and the function of these genes.

First, the gene duplication events were identified in four families of Musteloidea, including Procyonidae, Ailuridae, Mephitidae and Mustelidae, rejecting the Mustelidae-specific duplication hypothesis, but supporting the Musteloidea duplication hypothesis.

Second, the sequence analyses show the monophyly of the RNASE1 genes in each of Mustelidae, Procyonidae, Ailuridae, and Mephitidae (Supplementary Data 3b and Figures 2), suggesting that four independent family-specific gene duplication events occurred in Musteloidea. Interestingly, this independent diversification pattern of RNASE1 genes in Musteloidea parallels what has been proposed for this gene in the colobine monkeys (i.e., leaf-eating monkeys), in which two independent RNASE1 gene duplication events have been found in Asian colobine and African colobine subfamilies12,13,14,15. In comparison, the RNASE1 gene duplication pattern in the ruminant artiodactyls is different, which has been reported to arise through ancient gene duplication events in the common ancestor of all ruminants6,27, rather than independent duplications. Furthermore, several other lines of evidence support the independent diversifications of RNASE1 genes in four Musteloidea families discovered here: (1) the alternative tree topology supporting a single-gene duplication event prior to the divergence of the four families of Musteloidea was significantly worse than our presented tree (P < 0.05) under the Kishino-Hasegawa test28 and the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test29; and (2) no signals of gene conversion events, which can lead to spurious independent duplications by homogenizing sequences within species, were found using GENECOVN software30, suggesting that the observed family-specific clusters were not the results of concerted evolution via gene conversion.

Third, a far more complex evolutionary pattern within Mustelidae than the other three families of Musteloidea was demonstrated. 77 RNASE1 sequences from 21 Mustelidae species retrieved four gene groups (Groups A–D). For all tree-building methods and datasets used, Group A was found to diverge first, and Groups B–D emerge subsequently accompanied by a series of recent and lineage-specific gene duplications and pseudogenizations (Figures 2 and 3). In this light, we favor the hypothesis that Group A is the original gene copy and Groups B–D are the newly duplicated gene copies. Indeed, in support of this idea, the accelerated amino acid substitutions and the signal of positive selection have been discovered in the RNASE1 sequences of Groups B–D.

Either way, the expansion of the RNASE1 genes in the four Musteloidea families presents a particularly unusual path for the Caniformia RNASE1 evolution, which raises an intriguing question about the roles of these newly duplicated RNASE1 genes. We speculated that the duplicated Musteloid RNASE1 genes evolved to acquire new tissue specificity or novel physiological functions, which are reflected by their selection pressures, pI values and expression patterns that are distinct from those of the original genes.

First, different selection pressures were observed among the RNASE1 gene copies. It has long been thought that positive selection is one of the primary evolutionary forces driving functional divergence and organismal adaptation. Interestingly, both the site-specific model and the branch-site model of our maximum likelihood analyses revealed that dN significantly exceeds dS (dN/dS > 1) at a number of sites and on the branches leading to the duplicated RNASE1 lineages (i.e., those from Groups B–D), thereby supporting a significant contribution of positive selection on their evolution (Figure 1 and Table 3). Moreover, more than 10 amino acid substitutions that are targets of selection identified here have not been discovered in our previous study (Figure 1 and Table 3). When we mapped the positive selected residues identified in the present study on the 3-dimensional crystal structure of the molecule, most are found to locate on the surface of the RNASE1 enzyme and extend away from the active site (Supplementary Data 4). This finding is consistent with the conclusion from previous studies of this gene16, in which this gene has been taken as an example of adaptive replacements not being solely confined to the active sites, and those replacements contribute functional divergence by affecting enzyme activities or substrate binding in an indirect or complementary way.

Second, the duplicated RNASE1 gene copies have isoelectric points (pIs) distinct from those of the original genes. It has been suggested that there is a strong correlation between pI/net charge of RNase and its capacity to cleave double-stranded RNA. The high pI and positive charges of RNases are important for host-defense against pathogens3,31,32. Therefore, a change of pI/net charge has been used as one of the evidence for the functional changes of RNases18. For instance, the pI of RNASE3 (eosinophil-cationic protein or ECP) is significantly higher than that of. RNASE2 (eosinophil-derived neurotoxin or EDN). This is critical for RNase 3 to tightly contact to the negatively charged bacterial cell membrane, which is important for its prominent membrane-disruptive activity and anti-bacterial function18,33,34. The lower pIs of RNASE 9–13 relative to the other Rnase members represent another example. This feature has been used to explain partially the loss of ribonuclease activity and the acquisition of male reproduction functions for them18. More interestingly, in a previous study of RNASE1 from the leaf-eating monkeys, it was shown that the decrease in pI (net charge) of the duplicated RNASE1B relative to those of the original RNASE1 contributed to its adaptation for a digestive role, along with the loss of catalytical activity against duplex RNA13. In our present study, by examining 82 putative functional RNASE1 from Musteloidea, we found that pIs differ substantially among the gene copies, especially for those in Mustelidae (see Supplementary Data 1). In comparison with the original gene copy, i.e., Group A, Group B has the highest average pI of 8.9012 (8.418–9.214), whereas Group D has the lowest average pI of 8.1045 (7.402–8.918). Most of the species examined also have the lowest pI from Group D and the highest from group B among their RNASE1 gene copies (e.g., 8.517 vs. 9.188 for Mustela lutreola; 8.147 vs. 9.214 for Mustela erminea; 7.66 vs. 8.958 for Martes zibellina, etc.). Likewise, an analysis of the net charge displayed a similar trend (see Supplementary Data 1). These observations reinforce the idea that a functional divergence may have occurred through the charge change of the duplicated RNASE1 genes in Musteloidea. We propose that, as described by the common view of the correlation between pI/net charge and catalytical activity, Group B RNases are more active on duplex RNA, whereas Group D RNases have a low activity against duplex RNA. The replacements of the amino acid residues essential for catalytic activity in some RNASE1s of Group D also support this hypothesis (Figure 1). Note that the average net charge and pI of Group C did not undergo significant modifications compared with Group A. This may be due to several facts. One is the highly-variable pIs among the Group C genes, in contrast with the relatively constant pIs among the Group B and D genes. The other is that a smaller number of genes in Group C (only 9 genes) are used for the pI calculation. Despite this, the acquisition of new biological roles of Group C can be seen from the tissue-specific expression patterns (see below).

Third, RNASE1 gene copies have divergent expression pattern, which suggests differences in their physiological functions (Figure 3). For both of the species that represent the superfamily Musteloidea, genes from Group A are specifically and highly expressed in the guts, including the intestines and the duodenum, which are in accordance with the known features of RNases as a digestive enzyme, while those in Group B–D are predominantly expressed in a large amount in other tissues, e.g., the pancreas, the lung, the spleen and the muscle, while expressed minimally or not at all in the guts (Figure 3). We suggest that such differential expression patterns reflect the functional changes following RNASE1 duplication. In addition, we note that two duplicated genes in Group C of both Mustela sibirica and Melogale moschata exhibit nonoverlapping tissue-specific expression patterns. Interestingly, we found that pIs differ between Mustela sibirica RNASE1C (8.684) and Melogale moschata RNASE1C (8.115), with the latter also being the lowest among all of the RNASE1C genes in the analyses. Moreover, when compared to their respective original RNASE1s, the pI of Mustela sibirica RNASE1C is similar to RNASE1 (8.684 vs. 8.574), while that of Melogale moschata RNASE1C shows an obvious decrease (8.115 vs. 8.754). Therefore, the distinct pIs and expression patterns between the two RNASE1C genes consistently indicate the functional differentiations of them, notwithstanding their high sequence similarity.

In the tissue-specific mRNA expression analyses, another notable finding is that a transcribed RNASE1 pseudogene from Mustela sibirica (RNASE1Bψ1) in Group B is detected in several tissues, with the high expression in the pancreas and the heart (Figure 3d). The Mustela sibirica RNASE1Bψ1 exhibits typical characteristics of a pseudogene with frame-shifting mutations and premature stop codons. In earlier studies, pseudogenes were seldom mentioned and included in evolutionary and expression analyses, mainly because they have long been considered to be “dead” and nonfunctional35,36,37,38. Recently, pseudogenes have received more attention owing to growing evidence that some of them are transcriptionally “alive” or can even have biological roles37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Interestingly, in previous studies of evolutionary and functional diversification of RNases, the bovine seminal RNASE1, which arose by a gene duplication of pancreatic RNASE1, has been proposed to be a typical case of a pseudogene reactivation producing a novel function related to immunosuppressive and cell-based activities41,44,45, although this has been contested46. The expression of Mustela sibirica RNASE1Bψ1 here provided new and further evidence suggesting pseudogenes as a potential source of RNase functional diversification. Further assays are needed to test whether this transcribed pseudogene plays a regulatory role or performs specific physiological functions.

Previously, in foregut-fermenting ruminants and leaf-eating monkeys where the RNASE1 gene is duplicated6,7,47 and is associated with adaptation to eating plants, the duplicated genes are highly expressed in the pancreas and have few positive charges, while those expressed elsewhere show greater number of positive charges. However, that is not the case for the present study of the non-foregut-fermentation carnivores. Among the four gene groups of Mustelidae, Groups D and Group B genes have the lowest average net charge and the highest average net charge, respectively. The expression analyses of the four gene copies from Mustela sibirica showed that RNASE1D is expressed in the spleen (Mustela sibirica) and RNASE1Bψ1 is expressed in the pancreas. Of course, we should note that RNASE1Bψ1 is a pseudogene. Whether its expression patterns can represent the majority of Group B genes requires collection of more expression data for the Group B genes from other mustelid species.

In this study, we unravel the novel gene duplication events in the evolutionary history of RNASE1 that were previously not found in carnivores and generate hypotheses for the functional implications of the duplicated RNASE1s, which appear to be much more complex than previously thought. Our results significantly contribute to our current knowledge of the evolutionary and functional plasticity of RNASE1 genes in mammalian evolution. In future studies, it would be interesting to test whether there is variation in the expression profile of RNASE1 genes among the Musteloidea families, considering that the functional changes might occur independently in these four families. It would be also intriguing to see whether the RNASE1 pseudogene transcription is occurred in a similar manner in other Musteloidea species. Expression data from a broad taxonomic range of Musteloidea are required to address these questions.

Methods

Data Sets

34 species belonging to 8 Caniformia families, i.e., families Canidae (dogs), Ursidae (bears), Ailuridae (red panda), Procyonidae (raccoons), Mustelidae (weasels), Mephitidae (skunks), Otariidae (sea lions), and Phocidae (true seals), were examined in this study (Table 1). For each sample, total genomic DNA was isolated from blood or frozen tissues using standard proteinase K and phenol-chloroform extraction48. Based on available RNASE1 sequences from human, rat, mouse and dog, we designed a pair of degenerate primers MUSRNF38 (5′-TTTCCYGGCTAGGCTCKTC-3′) and MUSRNR559 (5′-GGCATCTCGCTGYTCTGGC-3′) to amplify the complete coding region of RNASE1 sequence (approximately 456bp). The optimal conditions adopted in PCR reactions were 95°C hot start (5 min), 10 cycles of 94°C denaturation (1 min), 63–53°C annealing (1.5 min), 72°C extension (1 min), and finally 25 cycles of 94°C denaturation (1 min), 53°C annealing (1 min), 72°C extension (1 min), followed by a final 72°C extension (10 min). The amplified PCR products were cloned into PMD18-T vector (Takara, China) and transformed into ultracompetent Escherichia coli cells (Takara, China). Plasmids containing the RNASE1 inserts were extracted using GenElute Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Shanghai, China). About 30 clones per ligation reaction were sequenced in both directions with an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA sequencer using standard protocols provided by the manufacturer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Only those sequences with more than 3 mutations in the protein sequence and corroborated by at least 2 independent amplification and sequencing runs were used in the analysis. In total, 94 newly determined RNASE1 gene sequences are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KC884954-KC884980 and KC884982-KC885048 (Table 1). A RNASE1 gene sequence was regarded as a pseudogene if its open reading frame (ORF) was disrupted.

Phylogenetic Reconstruction

The RNASE1 gene sequences were aligned with Clustal X version 2.049. Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using MEGA550 for neighbor-joining (NJ) analysis and using PAUP*4.0b851 for maximum parsimony (MP) analysis. In the NJ analysis, the Kimura 2-parameter model (K2P) with pairwise deletion option for gaps was used. In the MP analyses, a heuristic search strategy was employed with the tree-bisection-reconnection branch-swapping algorithm, random addition of taxa and 1,000 replicates per search. Only one of the best trees found during branch swapping was saved (MULTREES = NO in PAUP*), and zero length branches were collapsed. The reliability of the tree topologies was evaluated using bootstrap support (BS)52 with 1000 replicates for NJ and MP analyses. Trees were rooted with the RNASE1 sequences from the earliest diverging Canidae family53. Phylogenies were estimated from the data set with and without the pseudogenes.

Molecular clock test

The molecular clock hypothesis was examined by the relative-rate test of Li and Bousquet54 using the program RRTREE55. One advantage of this distance-based method is that it can divide substitution rates into nonsynonymous and synonymous rates for comparisons.

Selective pressure analyses

The nonsynonymous to synonymous rate ratio ω (dN/dS) provides an indication of the changes in selective pressure. A dN/dS ratio = 1, <1, and >1 will indicate neutral evolution, purifying selection, and positive selection on the protein, respectively. We used the codon-substitution models implemented in the CODEML program in the PAML package56 to analyze changes in selective pressure. Different starting ω values were also used to avoid local optima on the likelihood surface57. Two branch-specific models, “one ratio” (M0) and “free ratios” (M1), were compared to test if ω on the branches of the tree differ. The M0 model assumes the same ω ratio for all branches, whereas the M1 model assumes an independent ω ratio for each branch58. We constructed likelihood ratio tests (LRT) to compare the two models. Significant differences between the models were evaluated by calculating twice the log-likelihood difference following a χ2 distribution, with the number of degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the numbers of free parameters between the models. Two site-specific models, M8a and M8, were also compared using the LRT to test for the presence of individual codon sites under positive selection and to identify them59,60. The M8 models allow for positively selected sites. When this positive-selection model fits the data significantly better than the corresponding null model (M8a), then the presence of sites with ω > 1 is suggested. The conservative empirical Bayes approach61 is then used to calculate the posterior probabilities (PPs) of a specific codon site and identify those most likely to be under positive selection. As positive selection may act in very short episodes during the evolution of a protein62 and affect only a few sites along a few lineages in the phylogeny, the “branch-site” models accommodating ω ratios to vary both among lineages of interest and amino acid sites were also conducted63. We used the branch-site Model A as a stringency test (test 2) and identified amino acid sites under positive selection by an empirical Bayes approach along the lineages of interest59,63. The Bonferroni correction was used when multiple tests were performed64,65.

Total RNA isolation

Two Musteloidea species, Mustela sibirica and Melogale moschata, were used to examine tissue-specific mRNA expression of Musteloidea RNASE1 genes. Mustela sibirica was captured in Lancang (Yunnan Province, China) and Melogale moschata was captured along the Muyang River (Yunnan Province, China). For both species, RNA was isolated from the following fourteen tissues: bladder, brain, duodenum, heart, kidney, large intestine, liver, lung, muscle, pancreas, small intestine, spleen, stomach and tongue. Total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous-4PCR Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Due to the inclusion of DNase I in the RNAqueous-4PCR Kit (Ambion), the total RNA isolated with this kit is DNA-free. The concentration of RNA samples was ascertained by measuring their optical density at 260 nm. The quality of RNA was confirmed by detection of 18 S and 28 S bands after agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis.

cDNA amplification and sequencing

To determine whether all of the RNASE1 gene copies from Mustela sibirica (three putative functional genes and two pseudogenes) and Melogale moschata (two putative functional genes), which were identified by the direct cloning strategy (Data Sets in Materials and Methods; Table 1), are expressed, we amplified RNASE1 cDNAs from each tissue of Mustela sibirica and Melogale moschata using the primers MUSRNF38 and MUSRNR559. The amplified cDNAs were cloned into PMD18-T vector (Takara, China) and transformed into ultracompetent Escherichia coli cells (Takara, China). About 30 clones per ligation reaction containing the RNASE1 cDNA inserts were sequenced in both directions with an ABI PRISM 3730 DNA sequencer. In addition, from each tissue of these two mustelid species, we amplified the cDNA of acidic ribosomal protein gene (ARP) by using primers ARPF (5′-GTGGCA ATCCCTGACGCACC-3′) and ARPR (5′-CAGTCTCCACAGACAARGCCAGG- 3′). The ARP is a housekeeping gene66 and was used to normalize mRNA expression values in the subsequent expression analyses. The amplified ARP cDNAs were purified and sequenced in both directions with an ABI PRISM 3730 DNA sequencer.

mRNA Expression Analyses

We used the TaqMan® MGB probes to detect the tissue-specific mRNA expression of the different RNASE1 gene copies. Due to the high sequence specificity inherent to the MGB technology, this technique can be used to discriminate single nucleotide polymorphisms67,68,69. The sequence-specific TaqMan® MGB probes and RT-PCR primers for the expression quantification of the RNASE1 gene copies and ARP genes were designed and synthesized by using the Custom Taqman® Gene Expression Assay Service (Applied Biosystems, USA). Probes were 5′-labeled with a reporter dye FAM and 3′-labeled with a minor groove binder (MGB). The TaqMan® MGB probes and RT-PCR primers are acquired upon request. For the quantitative analysis of mRNA expression, we used the ABI Prism®7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The PCR conditions were conducted with one hold at 50°C for 2 min, followed by one hold at 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for one min, in a 20-μL reaction volume according to the manufacturer's conditions. All reactions had a PCR efficiency approaching 100%. The cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a detection threshold is referred to as CT and the difference of both CT values within a sample (ΔCT) is calculated (ΔCT = CT-FAM − CT-NFQ). All samples were measured in triduplicate using the mean for further analysis. The tissue-specific expression fold changes for each RNASE1 gene copy against the ARP gene were analyzed using SDS 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the following equation: Fold difference = 2−ΔCt, ΔCT = CT-RNase1 - CT-ARP, where CT-RNase1 is the cycle number for each RNASE1 gene copies and CT-ARP is the cycle number for the ARP gene.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank IRTA in Spain and Royal Ontario Museum in Canada for help in collecting samples. This work was supported by Grants from the State Key Basic Research and Development Plan (No. 2007CB411600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U0836603) and Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Experiments were performed by J.L. Evolutionary analyses were performed by X.P.W. RT-PCR data analysis were performed by J.L. Experimental design, interpretation of data and manuscript writing were performed by L.Y., Y.P.Z., S.C., B.K.L., D.M.I., O.A.R.

References

- Barnard E. A. Biological function of pancreatic ribonuclease. Nature 221, 340–344 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintema J. J. et al. Pancreatic ribonuclease: distribution and comparisons in mammals. Nature New Biol. 241, 76–78 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintema J. J. et al. The molecular evolution of pancreatic ribonuclease. J. Mol. Evol. 10, 49–71 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintema J. J., Fitch W. M. & Carsana A. Molecular evolution of pancreatic-type ribonucleases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3, 262–275 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breukelman H. J. et al. Secretory ribonuclease genes and pseudogenes in true ruminants. Gene 212, 259–268 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breukelman H. J. et al. Secretory ribonucleases in the primitive ruminant chevrotain (Tragulus javanicus). Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 3890–3897 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleineidam R. G. et al. Inclusion of cetaceans within the order Artiodactyla based on phylogenetic analysis of pancreatic ribonuclease genes. J. Mol. Evol. 48, 360–368 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintema J. J. The primary structure of langur (Presbytis entellus) pancreatic ribonuclease: adaptive features in digestive enzymes in mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 7, 470–477 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J. Y. F. et al. Molecular evolution of mammalian ribonucleases 1. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 27, 453–463 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienman J. E. et al. Duplication and divergence of 2 distinct pancreatic ribonuclease genes in leaf-eating African and Asian colobine monkeys. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1465–1479 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. et al. Evolution of RNases in leaf monkeys: being parallel gene duplications or parallel gene conversions is a problem of molecular phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50, 397–400 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. et al. Adaptive evolution of digestive RNASE1 genes in leaf-eating monkeys revisited: new insights from 10 additional Colobines. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 127–131 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Z., Zhang Y. P. & Rosenberg H. F. Adaptive evolution of a duplicated pancreatic ribonuclease gene in a leaf-eating monkey. Nat. Genet. 30, 411–415 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Z. Parallel adaptive origins of digestive RNases in Asian and African leaf monkeys. Nat. Genet. 38, 819–823 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Z. Phylogenetic evidence for parallel adaptive origins of digestive RNases in Asian and African leaf monkeys: A response to Xu et al. (2009). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 53, 608–609 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. & Zhang Y. P. The unusual adaptive expansion of pancreatic ribonuclease gene in carnivore. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 2326–2335 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn P. & Moore S. Pancreatic ribonuclease,. in: Boyer P. D. (Ed.), The Enzymes, vol. 15, Academic Press, New York, pp. 317–433 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Beintema J. J. & Zhang J. The ribonuclease A superfamily of mammals and birds: identifying new members and tracing evolutionary histories. Genomics 85, 208–220 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. et al. Phylogenetic relationships within mammalian order Carnivora indicated by sequences of two nuclear DNA genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33, 694–705 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. & Zhang Y. P. Phylogeny of the Caniform Carnivora: Evidence from Multiple Genes. Genetica 127, 65–79 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. J. et al. Molecular phylogeny of the carnivora (mammalia): assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships. Syst. Biol. 54, 317–337 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton T. L. & Strobeck C. Molecular phylogeny of the Arctoidea (Carnivora): effect of missing data on supertree and supermatrix analyses of multiple gene data sets. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 41, 165–181 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato J. J. et al. Deciphering and dating the red panda's ancestry and early adaptive radiation of Musteloidea. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 53, 907–922 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason U. et al. Mitogenomic analyses of caniform relationships. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 45, 863–874 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik E. et al. Pattern and timing of diversification of the mammalian order Carnivora inferred from multiple nuclear gene sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 49–63 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. et al. Phylogenetic Utility of Nuclear Introns in Interfamilial Relationships of Caniformia (Order Carnivora). Syst. Biol. 60,175–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintema J. J. & Kleineidam R. G. The ribonuclease A superfamily: general discussion. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 54, 825–832 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino H. & Hasegawa M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J. Mol. Evol. 29, 170–179 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira H. & Hasegawa M. Multiple comparisons of loglikelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1114–1116 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. Statistical tests for detecting gene conversion. Mol. Biol. Evol. 6, 526–538 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libonati M., Furia A. & Beintema J. J. Basic charges on mammalian ribonulease molecules and the ability to attack double-stranded RNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 69, 445–51 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J. Y. et al. Pancreatic-type ribonuclease 1 gene duplications in rat species. J. Mol. Evol. 55, 522–533 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L. V. et al. Angiogenins: a new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 4, 269–273 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Z., Rosenberg H. F. & Nei M. Positive selection after gene duplication in primate ribonuclease genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 95, 3708–3713 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanin E. F. Processed pseudogenes: characteristics and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet. 19, 253–272 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mighell A. J. et al. Vertebrate pseudogenes. FEBS Lett. 468, 109–114 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakirev E. S. & Ayala F. J. Pseudogenes: are they ‘junk’ or functional DNA? Annu. Rev. Genet. 37, 123–151 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D. & Gerstein M. B. The ambiguous boundary between genes and pseudogenes: the dead rise up, or do they? Trends Genet. 23, 219–224 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S. et al. An expressed pseudogene regulates the messenger-RNA stability of its homologous coding gene. Nature 423, 91–96 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K. et al. Empirical analysis of transcriptional activity in the Arabidopsis genome. Science 302, 842–846 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. M. et al. Transcribed processed pseudogenes in the human genome: an intermediate form of expressed retrosequence lacking protein-coding ability. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2374–2383 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam O. H. et al. Pseudogene-derived small interfering RNAs regulate gene expression in mouse oocytes. Nature 453, 534–538 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliseno L. et al. A coding- independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature 465, 1033–1038 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Z. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 292–298 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Katju V. & Lynch M. On the formation of novel genes by du-plication in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1056–1067 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi S. O., Braun E. L. & Benner S. A. The evolution of seminal ribonuclease: pseudogene reactivation or multiple gene inactivation events? Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1012–1024 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. et al. Ruminant brain ribonucleases: expression and evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1547, 95–103 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook E., Fritsch F. & Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY (1989).

- Larkin M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2371–2379 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony*and other methods). Version 4. (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts (2002).

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. J. & Nedbal M. A. Phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Congruence vs incompatibility among multiple data sets. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 9, 414–426 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P. & Bousquet J. Relative-rate test for nucleotide substitutions between two lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9, 1185–1189 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Rechavi M. & Huchon D. RRTree: relative-rate tests between groups of sequences on a phylogenetic tree. Bioinformatics 16, 296–297 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y. & Nei M. Reliabilities of parsimony-based and likelihood-based methods for detecting positive selection at single amino acid sites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 2179–2185 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 568–573 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R. & Yang Z. Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics 148, 929–936 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Maximum likelihood estimation on large phylogenies and analysis of adaptive evolution in human influenza virus A. J. Mol. Evol. 51, 423–432 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Wong W. S. & Nielsen R. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1107–1118 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. H. The causes of molecular evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Golding GB, Dean AM (1991).

- Zhang J., Nielsen R. & Yang Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 2472–2479 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonferroni C. E. Il calcolo delle assicurazioni su gruppi di teste. Studi in Onore del Professore Salvatore Ortu Carboni. 13 (1935).

- Bonferroni C. E. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Libreria internazionale Seeber. (1936).

- Dheda K. et al. Validation of housekeeping genes for normalizing RNA expression in real-time PCR. Biotechniques 37, 112–4, 116,, 118–9 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonina I. et al. Efficient priming of PCR with short oligonucleotides conjugated to a minor groove binder. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 25, 2657–2660 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kok J. B. et al. Rapid genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms using novel minor groove binding DNA oligonucleotides (MGB probes). Hum. Mutat. 19, 554–559 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information