Abstract

Ferroptosis has been defined as an oxidative and iron-dependent pathway of regulated cell death that is distinct from caspase-dependent apoptosis and established pathways of death receptor-mediated regulated necrosis. While emerging evidence linked features of ferroptosis induced e.g. by erastin-mediated inhibition of the Xc- system or inhibition of glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4) to an increasing number of oxidative cell death paradigms in cancer cells, neurons or kidney cells, the biochemical pathways of oxidative cell death remained largely unclear. In particular, the role of mitochondrial damage in paradigms of ferroptosis needs further investigation.

In the present study, we find that erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuronal cells was accompanied by BID transactivation to mitochondria, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, enhanced mitochondrial fragmentation and reduced ATP levels. These hallmarks of mitochondrial demise are also established features of oxytosis, a paradigm of cell death induced by Xc- inhibition by millimolar concentrations of glutamate. Bid knockout using CRISPR/Cas9 approaches preserved mitochondrial integrity and function, and mediated neuroprotective effects against both, ferroptosis and oxytosis. Furthermore, the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 inhibited erastin-induced ferroptosis, and, in turn, the ferroptosis inhibitors ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 prevented mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in the paradigm of oxytosis. These findings show that mitochondrial transactivation of BID links ferroptosis to mitochondrial damage as the final execution step in this paradigm of oxidative cell death.

Keywords: Ferroptosis, BID, Mitochondria, CRISPR, Oxytosis, Neuronal death

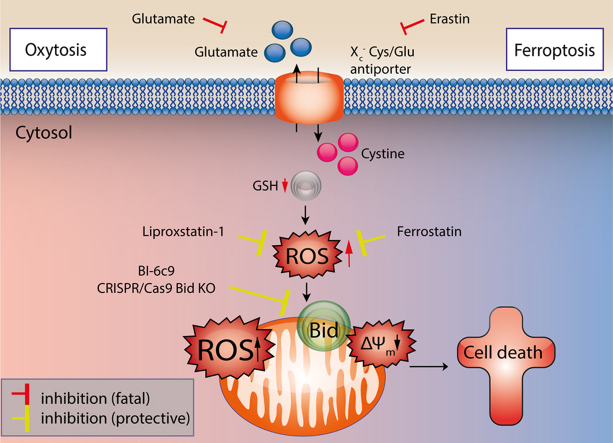

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CRISPR Bid knockout reveals a pivotal role for BID in oxidative death.

-

•

BID links ferroptosis to mitochondrial demise in neurons.

-

•

Mitochondrial damage determines cell death in oxytosis and ferroptosis.

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is a well-accepted paradigm mediating neuronal dysfunction and death in age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD). In according experimental settings investigating the underlying mechanisms in the different paradigms of neurodegeneration, deregulated intracellular calcium homeostasis and oxidative stress were identified as common triggers of death signaling in neurons. Such pathways of programmed cell death (PCD) converge at the mitochondria, the key organelles of energy metabolism which secure neuronal functions and survival under physiological conditions [18]. In paradigms of programmed cell death, mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with mitochondrial fragmentation, permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane (MOMP) and the release of pro-apoptotic proteins such as cytochrome c or apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from the intermembrane space into the cytosol, where they orchestrate the final steps of PCD [18], [4]. The molecular pathways mediating mitochondrial damage and neuronal death in response to oxidative stress, however, are still poorly defined. Understanding how these highly regulated neuronal cell death programs are activated and lead to neuronal demise is of great scientific and clinical relevance.

Oxytosis is one paradigm of oxidative cell death that has been established in neuronal cells [16], [24]. Lethal signaling pathways related to oxytosis can be induced in neuronal cells by glutamate-mediated inhibition of the cystine-glutamate antiporter (Xc-) thereby depleting the intracellular pool of glutathione (GSH) [23]. Reduced GSH levels impair the redox defense of neuronal cells, thus increasing intracellular ROS levels that trigger caspase-independent cell death [16], [24]. In particular, GSH depletion reduces the activity of glutathione peroxidase-4 (Gpx4) and increases 12/15-lipoxygenase (LOX) activity, which are key events upstream of mitochondrial dysfunction [21], [25], [26]. In paradigms of oxytosis in neuronal cells, mitochondrial impairments are mediated through mitochondrial transactivation of the pro-apoptotic protein BID [13], [16], [25]. Upon translocation to the mitochondria, BID mediates loss of mitochondrial integrity and function and detrimental translocation of mitochondrial AIF to the nucleus [12], [13], [19], [21], [24], [25], [26], [5].

The concept of ferroptosis has recently been introduced as an iron-dependent form of oxidative cell death in cancer cells and in neurons [7]. Later, features of ferroptotic cell death have also been observed in kidney cells [17,9]. The paradigm of ferroptosis involves the generation of soluble and lipid ROS through iron-dependent enzymatic reactions which are, for example, mediated by lipoxygenases, xanthine oxidases, NADPH oxidase or catalase [27], [8]. In addition to iron-chelating compounds, ferroptosis can be blocked by ferrostatin-1, a potent inhibitor which mediates protective effects against erastin-induced ferroptosis by inhibiting lipid peroxidation [27], [7]. Further, mechanisms of ferroptosis have been identified in neurons, in death signaling pathways induced by cerebral ischemia [22] and in glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures [7]. Similarly as in glutamate-induced oxytosis, erastin activates ferroptosis by inhibiting the Xc- transporter. In contrast to the paradigms of oxytosis, however, ferroptosis in cancer cells did not involve mitochondrial damage [7]. In fibroblasts and kidney cells, ferroptosis was accompanied by alterations in mitochondrial morphology and integrity, including reduced organelle size and vanishing of mitochondrial cristae, condensed mitochondrial membrane densities and rupture of the mitochondrial outer membrane, respectively [27].

The biochemical mechanisms linking oxidative stress to mitochondrial damage in ferroptosis, however, has not yet been clarified. Further, how the emerging concepts of oxytosis and ferroptosis may converge, particularly in intrinsic death signaling involving mitochondrial dysfunction is largely unclear. In the present study, we found that pathways of ferroptosis and oxytosis are linked via BID and subsequent mitochondrial damage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

HT-22 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Capricorn) with the addition of 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. For inducing cell death, different concentrations of glutamate (2–8 mM) or erastin (0.25–1 µM) were added to the medium for the indicated amount of time.

Ferrostatin-1 and BI-6c9 were dissolved in DMSO and used in a concentration of 2 µM and 10 µM, respectively.

MEF cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) were cultured in DMEM which was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine.

2.2. Generation and sequencing of HT-22 Bid KO cells

Wild-type (WT) HT-22 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 100,000 cells/well and after 24 h, transfected with 5 µg Bid CRISPR plasmid (U6gRNA-Cas9-2A-GFP; MM0000220718, Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen) using 4.5 µl Attractene (Qiagen) and up to 250 µl OptiMEM/well. Two days later, transfection efficiency was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy and cells were harvested with trypsin. Afterwards, cells were sorted via FACS and single cells were seeded into a 96-well plate. In order to exclude dead cells, cells were co-stained with DAPI. Cells were cultured with weekly media change to obtain appropriate amount of cells for further analysis.

For sequencing, genomic DNA was purified with the Invitrap® Spin Universal RNA Mini Kit followed by the amplification of a ~1000 bp sequence (CRISPR region) using the following primers (5′ −3′): AGCCCTGAACGGAAACATGG, CAGGCGGATCTCTGAGTTCG. Thereafter, the ~1000 bp PCR product was purified by gel electrophoresis and DNA gel extraction using the Promega Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System according to the manufacturer's protocol and was sequenced accordingly.

2.3. Protein analysis and western blot

For protein analysis, cells were washed once with PBS and lysed with buffer containing 0.25 M Mannitol, 0.05 M Tris, 1 M EDTA, 1 M EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton-X, supplemented with Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and PhosSTOP (both Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). Extracts were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C to eliminate insoluble fragments. The total amount of protein was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Perbio Science, Bonn, Germany). For Western Blot analysis, 50 µg of protein were loaded on a 12.5% SDS-Gel and blotted onto a PVDF-membrane at 20 mA for 21 h. Incubation with primary antibody was performed overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: BID (Cell Signaling, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) and Actin C4 (MB Biomedicals, Illkirch Cedex, France). After incubation with a proper secondary HRP-labeled antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) Western Blot signals were detected by chemiluminescence with Chemidoc software (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany).

2.4. Plasmid transfection

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, 35,000 cells/well were seeded in 24-well plates and allowed to grow overnight. The next day cells were pre-treated for 1 h with 10 µM BI-6c9 (Sigma Aldrich) or 2 µM ferrostatin-1 (Sigma Aldrich), respectively and plasmid transfection was performed. A transfection mix consisting of 2 µg tBID plasmid or pcDNA 3.1 dissolved in OptiMEM I and Attractene (4.5 µl/well) was prepared. The tBid vector was generated as described previously [16]. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature cells were transfected with the mix. The plasmid pcDNA 3.1 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used as a control vector. Cell death was analyzed after the indicated amount of time by Annexin V/PI staining (Promokine, Heidelberg, Germany).

For real time impedance measurements, 8000 cells/well were seeded in 96-well Eplates and allowed to grow overnight. The next day a transfection mix consisting of 0.75 µg pIRES tBID plasmid or pcDNA 3.1 dissolved in OptiMEM I and Attractene (0.75 µl/well) was prepared. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature cells were transfected with the mix.

2.5. Cell viability

Cell viability was detected using the MTT assay. At indicated time points of treatment 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added at a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml for 1 h at 37 °C to the culture medium. Afterwards, the purple formazan was dissolved in DMSO and absorbance was measured at 570 nm versus 630 nm with FluoStar. The effects of erastin and glutamate as well as overexpression of tBID on cell viability in HT-22 Bid KO cells were studied by real-time measurements of cellular impedance using the xCELLigence system as previously described [6].

Additionally, cell viability of glutamate- and erastin-treated HT-22 and HT-22 Bid KO cells as well as after tBID-overexpression was detected by an Annexin V/PI staining using an Annexin-V-FITC Detection Kit followed by FACS analysis. Annexin-V-FITC was excited at 488 nm and emission was detected through a 530±40 nm band pass filter (Green fluorescence). Propidium iodide was excited at 488 nm and fluorescence emission was detected using a 680±30 nm band pass filter (Red fluorescence). Data were collected from 10,000 cells from at least four wells per condition.

2.6. Glutathione measurement

To determine GSH levels, HT-22 WT and Bid KO cells were seeded in 6-well plates (180,000 cells/well). After treatment with either glutamate or erastin for the indicated amount of time two to three wells per condition were harvested by scratching and washed once with PBS. GSH measurements were performed using the Glutathione Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, USA) following manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were re-suspended in MES-buffer (0.4 M 2-(N-mopholino)ethanesulphonic acid, 0.1 M phosphate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.0) and homogenized by sonification. Insoluble fragments were removed by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min. The supernatant was deproteinated by the addition of an equal volume of metaphosphoric acid (1.25 M). After incubation for 5 min the mixture was centrifuged at 17,000×g for 10 min. Subsequently, the supernatant was mixed with a 4 M solution of triethanolamine to increase the pH. After transferal into a 96-well plate, the assay cocktail containing provided MES-buffer, co-factor mixture, enzyme mixture and Ellman's reagent was added. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm after 30 min of incubation. Total GSH amount was determined via standard curve calculation and normalized to protein content.

2.7. Lipid peroxidation

For detection of lipid peroxidation, HT-22 cells were seeded in 24-well plates with 55,000 cells/well. After treatment with erastin or glutamate cells were stained with BODIPY 581/591 C11 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 1 h at 37 °C in culture medium. For evaluation of the inhibitors, cells were co-treated with BI-6c9 and erastin or ferrostatin-1 and glutamate for the indicated amount of time before staining with BODIPY 581/591 C11. After collecting and washing once with PBS, cells were re-suspended in an appropriate amount of PBS. Lipid peroxidation was analyzed by the detection of a fluorescence shift from green to red via FACS analysis. Excitation was performed at 488 nm and emission was recorded at 530 nm (green) and 585 nm (red). Data were collected from at least 10,000 cells.

2.8. Mitochondrial ROS formation

Formation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) was investigated via MitoSOX red staining (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). For detection of mitochondrial ROS production, HT-22 cells were seeded in 24-well plates with 55,000 cells/well. After treatment with erastin or glutamate, respectively, cells were stained with MitoSOX red for 30 min at 37 °C. After collecting and washing once with PBS, cells were re-suspended in PBS and red fluorescence was detected by FACS analysis. Data were collected from at least 10,000 cells.

2.9. Mitochondrial morphology

For detection of changes in mitochondrial morphology cells were stained with MitoTracker DeepRed (200 nM) for 20 min at 37 °C. In 8-well ibidi slides 17,000 cells/well were seeded and staining was performed before glutamate or erastin exposure. After the indicated time of treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at RT. Mitochondria were divided into three categories as previously described [13]. Briefly, cells exhibiting elongated mitochondria organized in a tubular network represented category I. Cells predominantly showing large dotted mitochondria equally distributed all over the cytosol were assigned to category II, whereas cells with totally fragmented mitochondria surrounding the nucleus belong to category III. At least 500 cells per condition were counted without knowledge of treatment conditions. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (63x objective). MitoTracker DeepRed fluorescence was excited at a wavelength of 620 nm band pass filter and emissions were detected using 670 nm long pass filter (red).

2.10. ATP measurement

For analysis of total ATP levels, cells were seeded in white 96-well plates (8000 cells/well). At the indicated time points after glutamate or erastin treatment, ATP levels were analyzed by luminescence detection with FluoStar according to the manufacturer's protocol using the ViaLight™plus Kit (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium).

2.11. Measurement of cellular oxygen consumption rate

To determine the cellular oxygen consumption rate, cells were plated in XF96-well microplates (8000 cells/well, Seahorse Bioscience) and treated with either erastin or glutamate. At indicated time points after treatment OCR measurements were performed as previously described [11] with minor modifications. Briefly, the growth medium was washed off and replaced by ~180 µl of assay medium (with 4.5 g/l glucose as the sugar source, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, pH 7.35) and cells were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. Three baseline measurements were recorded before adding the compounds. Oligomycin was injected in port A (20 µl) at a final concentration of 3 µM, FCCP (22.5 µl in port B) at a concentration of 0.5 µM and rotenone/antimycin A (25 µl in port C) at a concentration of 100 nM and 1 µM, respectively. Three measurements were performed after the addition of each compound (4 min mixing followed by 3 min detection).

2.12. Mitochondrial membrane potential

In order to determine changes in the MMP in HT-22 cells after glutamate and erastin exposure, the MitoPT TMRE Kit (Immunochemistry Technologies, Hamburg, Germany) was used. For detection of changes in MMP, HT-22 cells were seeded in 24-well plates with 55,000 cells/well. After treatment with BI-6c9 and erastin or ferrostatin-1 and glutamate, cells were collected and stained with TMRE at a final concentration of 200 nM for 20 min at 37 °C. After washing with PBS cells were re-suspended in an appropriate amount of assay buffer and TMRE fluorescence was assessed by FACS analysis. Data were collected from at least 10,000 cells.

2.13. BID translocation and confocal microscopy

For investigation of BID translocation cells were seeded in 8-well ibidi slides at a density of 17,000 cells/well and transfected with the pDSRed2-Bid vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, USA). To visualize the mitochondria, cells were co-transfected with a mitochondrial-targeted green fluorescent protein (GFP). Transfection was achieved by using Attractene transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with either erastin or glutamate. After the indicated time of treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope and light was collected through a 63×1.4 NA oil immersion objective. Mitochondrial GFP fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and emissions were detected between a bandwidth of 500 nm and 535 nm. DSred2-BID fluorescence was detected by excitation at 633 nm and emission between 640 nm and 750 nm. For digital imaging, the software LSM Image Browser 4.2.0 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used. Quantification of the LSM images to show mitochondrial translocation of BID was performed using the software ImageJ 1.48 v (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA). The fluorescence intensity along a defined line in both mito-GFP and DSRed2-BID images was determined by creating a plot profile and values were used for further analysis of correlation. Therefore, Pearson's coefficient was calculated by Microsoft Excel and given as mean±standard deviation.

2.14. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean + standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparison between treatment groups was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Scheffé’s post hoc test. Calculations were executed with Winstat standard statistical software (R. Fitch Software, Bad Krozingen, Germany).

3. Results

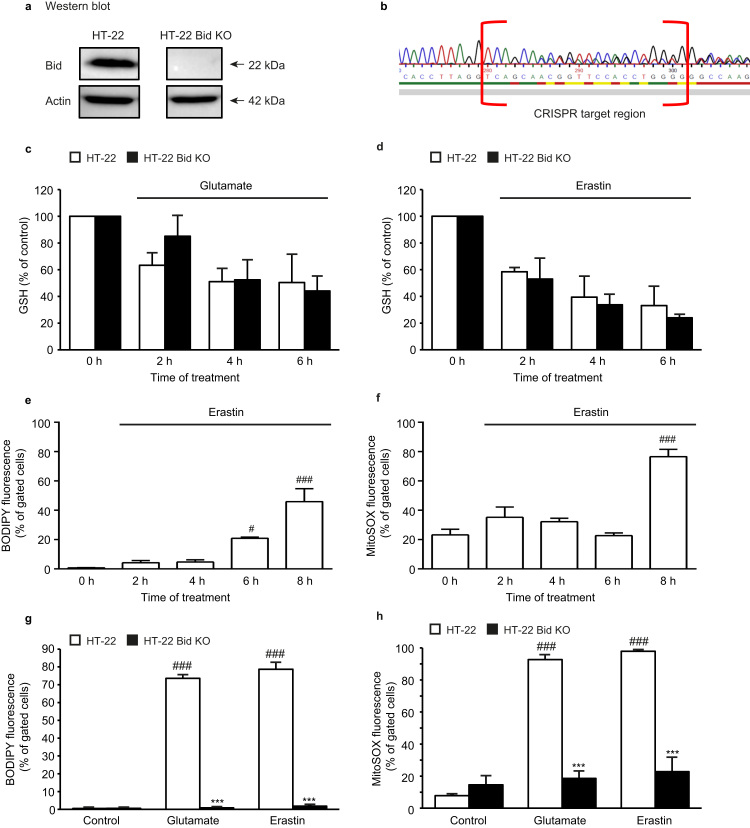

3.1. Bid knockout prevents mitochondrial dysfunction independent of glutathione depletion in paradigms of ferroptosis and oxytosis

For investigating the effects of erastin in neuronal HT-22 cells and in particular, the role of BID in this cell death paradigm, we generated an HT-22 Bid knockout cell line (HT-22 Bid KO) using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Genetic deletion of BID was verified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1a) and indel mutations by CRISPR/Cas9 analyzed by sequencing of the respective target site (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Bid KO does not inhibit glutathione depletion, but prevents ROS formation. a: Western blot verified knockout of Bid (22 kDa) in HT-22 Bid KO cells. b: Sequencing of the Bid CRISPR target region revealed different indel mutations in the alleles indicated as multiple peaks. c, d: Measurement of glutathione (GSH) depicted rapid decrease of GSH after glutamate (8 mM; c) or erastin (1 µM; d) exposure which was not restored by Bid KO (n=4/treatment condition). e: BODIPY 581/591 staining and subsequent FACS analysis for measurement of lipid peroxide formation showed time-dependent increase in the fluorescence after erastin (1 µM) exposure in HT-22 WT cells (n=3/treatment condition). f: MitoSOX staining and subsequent FACS analysis revealed time-dependent mitochondrial ROS formation after erastin (1 µM) exposure in HT-22 cells (n=3/treatment condition). g: Cells were stained with BODIPY 581/591 and changes of fluorescence were detected by FACS analysis after 10 h of glutamate (7.5 mM) or erastin (1 µM) treatment. Bid KO fully prevented the formation of lipid peroxides compared to WT control cells (n=4/treatment condition). h: MitoSOX staining and subsequent FACS analysis depicted reduced formation of mitochondrial ROS in HT-22 Bid KO cells compared to WT HT-22 cells after erastin (1 µM, 19 h) or glutamate (7 mM, 19 h) challenge (n=4/treatment condition). All data are given as mean + S.D. #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 compared to untreated HT-22 control; ***p<0.001 compared to erastin-/ glutamate-treated HT-22 control (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

BID is the mediator of mitochondrial dysfunction downstream of glutathione (GSH) depletion in the model of oxytosis [25]. Consequently, in the present study Bid KO did not prevent glutamate-induced depletion of GSH (Fig. 1c). Like glutamate, erastin induced a pronounced loss of GSH in a time-dependent manner in both WT and HT-22 Bid KO cells (Fig. 1d). Fluorescent BODIPY staining and FACS analysis was used to address the formation of lipid peroxides after GSH depletion and subsequent activation of 12/15-lipoxygenases [21], [25]. Increasing levels of lipid peroxides were measured in WT HT-22 cells and MEF cells (Supp. 1a) 6 h after erastin exposure in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1e) whereas BID deletion significantly prevented lipid peroxide formation upon glutamate or erastin treatment (Fig. 1g).

Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS formation in mitochondria succeeding lipid peroxidation were investigated by FACS analysis of TMRE and MitoSOX red fluorescence, respectively. TMRE fluorescence started to decrease at 6 h (Supp. 2a) and MitoSOX fluorescence increased at 8 h after erastin exposure in WT HT-22 cells (Fig. 1f) and in MEF cells (Supp. 1b). At the same time ATP levels started to decrease at 6–8 h after erastin challenge in WT HT-22 cells (Supp. 2b) indicating functional loss of mitochondria. Despite the exposure to glutamate or erastin HT-22 Bid KO cells showed mitochondrial ROS formation maintained at the levels of untreated controls (Fig. 1h).

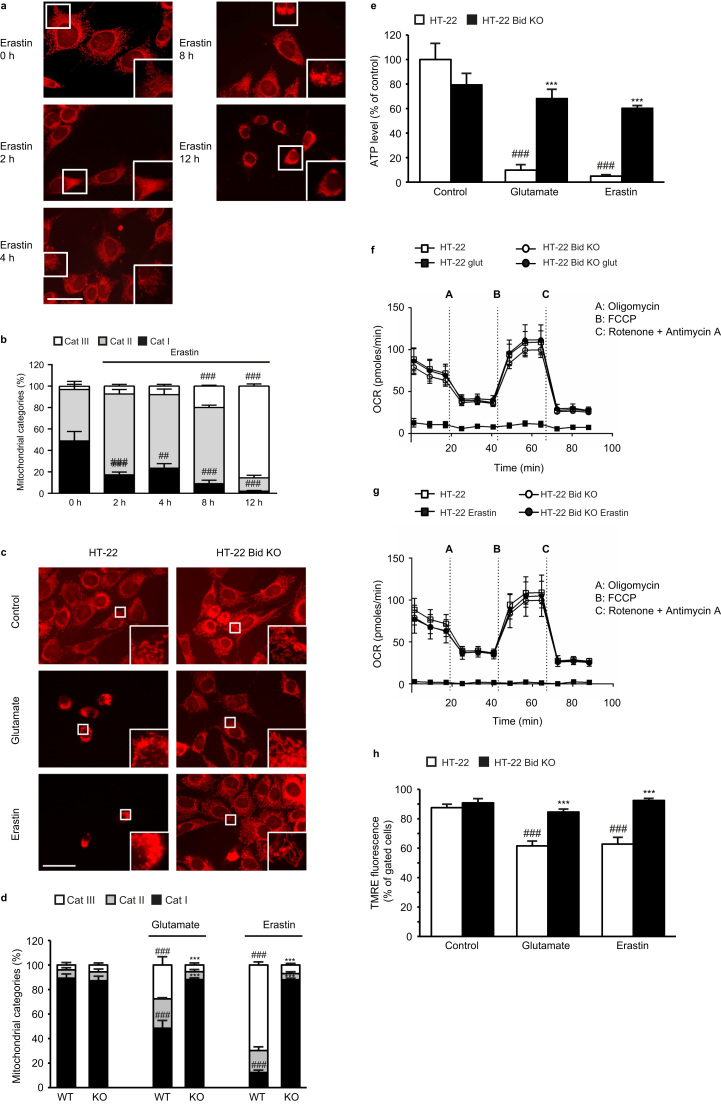

Furthermore, we observed time-dependent changes of mitochondrial morphology in response to erastin toxicity comprising mitochondrial fragmentation and accumulation around the nucleus (Fig. 2a). In order to quantify these morphological changes, we established a classification system [13] consisting of three categories (for details see materials and methods). Briefly, cells predominantly showing fragmented mitochondria around the nucleus are assigned to category III. Cells containing a network of elongated mitochondria were assigned to category I. The quantification of mitochondrial shape after erastin treatment showed a significant increase in cells of category III in HT-22 WT cells after 8 h (Fig. 2b) matching the aforementioned increase in mitochondrial ROS formation as an additional hallmark of mitochondrial damage. Despite glutamate or erastin challenge, mitochondria in HT-22 Bid KO cells maintained a network of tubule-shaped morphology being characteristic for healthy and functional mitochondria (Fig. 2c). The quantification of mitochondrial morphology showed a significant increase in cells of category III after glutamate or erastin treatment in HT-22 WT cells, while the mitochondrial pattern in HT-22 Bid KO cells remained similar to control cells (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Bid KO preserves mitochondrial integrity. a: Representative images show mitochondrial morphology in HT-22 WT cells in the presence and absence of erastin (1 µM, 2–12 h) (63x objective). Scale bar: 50 µm. b: Quantification of 500 cells counted blind to treatment of conditions of 3 independent experiments revealed time-dependent mitochondrial fission in HT-22 cells after erastin (1 µM) exposure. c: Representative images show mitochondrial morphology in HT-22 WT and Bid KO cells in the presence and absence of glutamate (5 mM, 15 h) or erastin (0.5 µM, 15 h) (63x objective). Scale bar: 50 µm. d: Quantification of 500 cells counted blind to treatment of conditions of 3 independent experiments revealed reduction of glutamate/ erastin-induced mitochondrial fission in Bid KO cells. e: After 17 h of treatment with glutamate (7 mM) or erastin (1 µM) ATP levels were measured. Bid KO prevented ATP depletion compared to WT controls (n=8/treatment condition). f, g: Measurement of the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) revealed restored basal and maximal respiration in Bid KO cells compared to WT controls after 16 h glutamate (2 mM; e) or erastin (0.25 µM; f) exposure (n=6/treatment condition). h: HT-22 Bid KO cells exhibited restored MMP measured by TMRE fluorescence compared to WT HT-22 cells after glutamate (7 mM, 19 h) or erastin (1 µM, 19 h) exposure (n=4/treatment condition). All data are given as mean +S.D. or±S.D. ##p<0.01; ###p<0.001 compared to untreated HT-22 control, ***p<0.001 compared to erastin-/ glutamate-treated HT-22 control (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

For the purpose of correlating morphology with functionality, we next examined ATP levels. Both erastin and glutamate induced a pronounced loss of ATP in HT-22 WT cells, which was fully prevented in HT-22 Bid KO cells (Fig. 2e). Measurements of the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR), which reflects the mitochondrial respiration confirmed preserved mitochondrial function in HT-22 Bid KO after treatment with glutamate or erastin. Under basal conditions, the OCR of Bid KO cells did not differ from WT HT-22 cells (Fig. 2f, g). In these cells, both glutamate (Fig. 2f) and erastin (Fig. 2g) led to a strong reduction of the mitochondrial respiration indicated by a hardly detectable OCR, while HT-22 Bid KO cells showed normal respiration in the presence of both, glutamate or erastin. These measurements confirmed the results of the ATP assay and further emphasized preserved mitochondrial respiration in Bid KO cells. In line, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), which is essential for neuronal function and maintenance [18] was restored in both paradigms of oxidative stress (Fig. 2h). Consistent with previous observations [13], [16], glutamate induced a reduction of the MMP indicated by reduced TMRE fluorescence, and similar effects were observed after erastin treatment in the WT HT-22 cells (Fig. 2h). Bid KO protected the cells against a loss of MMP after exposure of either glutamate or erastin (Fig. 2h).

Taken together, these findings demonstrate a pivotal role for BID mediating mitochondrial dysfunction, formation of mitochondrial ROS and cell death in the models of glutamate-induced oxytosis and in erastin-induced ferroptosis suggesting that BID serves as the link between these distinct paradigms of oxidative death in neuronal cells.

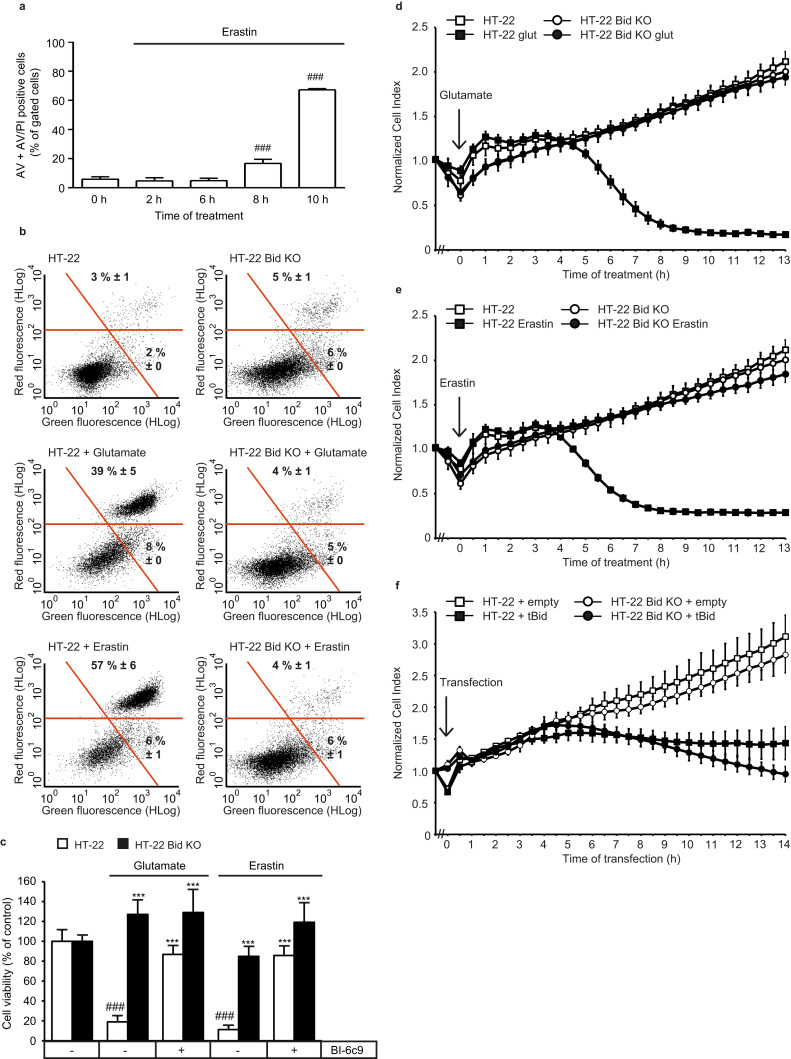

3.2. BID deletion prevents erastin- and glutamate-induced cell death

Erastin-induced ferroptosis gradually leads to cell death quantified by FACS analysis of Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) stained WT HT-22 cells (Fig. 3a) and MEF cells (Supp. 1c). However, both erastin- and glutamate-induced cell death measured by Annexin V/PI staining in WT HT-22 cells was fully inhibited by Bid KO (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 prevented death measured by MTT fluorescence of wild-type (WT) HT-22 cells after both erastin and glutamate exposure to a similar extent as the HT-22 Bid KO underlining the pivotal role of BID in both paradigms of oxidative cell death (Fig. 3c). In line with our previous studies [19], detailed analysis of cell viability showed that the protective effect of BI-6c9 against glutamate and erastin is dose-dependent (Supp. 3a and 3b). Real-time impedance measurements of cell viability after glutamate (Fig. 3d) and erastin (Fig. 3e) treatment revealed a sustained protective effect in HT-22 Bid KO cells compared to HT-22 WT cells. Overexpression of tBID, the activated form of BID, induced death of both HT-22 WT and HT-22 Bid KO cells indicated by a reduction of the cell index (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Bid KO prevents glutamate- and erastin induced cell death. a: Annexin V/PI double staining and subsequent FACS analysis revealed time-dependent cell death after erastin (1 µM) exposure in HT-22 cells (n=3/treatment condition). b: Representative plots of Annexin V/PI staining and subsequent FACS analysis showed increase in Annexin V (Green fluorescence) and PI (Red fluorescence) positive cells after glutamate (7 mM, 16 h) and erastin (1 µM, 16 h) exposure in HT-22 WT cells. In Bid KO cells, neither erastin nor glutamate altered the amount of Annexin V or PI positive cells. Numbers in the dot blots present percentage mean±S.D. of AV positive cells (lower right) and AV+PI positive cells (upper right) (n=4) c: MTT confirmed protection of HT-22 Bid KO cells against erastin (1 µM, 16 h) and glutamate (7 mM, 16 h) exposure. Furthermore, in HT-22 WT cells, the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 (10 µM) fully prevented cell death in response to oxidative stress (n=8/treatment condition). d, e: Real-time impedance measurements revealed protective effect of Bid KO against both glutamate (7 mM; d) and erastin (1 µM; e) toxicity. Data were derived from the same experiment, but shown in separated graphs for better visualization; (n=6/treatment condition). f: Over-expression of tBid (0.75 µg plasmid-DNA/well) induced death of both WT and Bid KO HT-22 cells detected by xCELLigence recordings (n=6/treatment condition), representative experiment shown. All data are given as mean +S.D. or±S.D. ###p<0.001 compared to untreated control; ***p<0.001 compared to erastin-/ glutamate-treated HT-22 control (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

In summary these data further emphasize the decisive role of BID in both model systems validated by oxidative stress resistance owing to Bid KO.

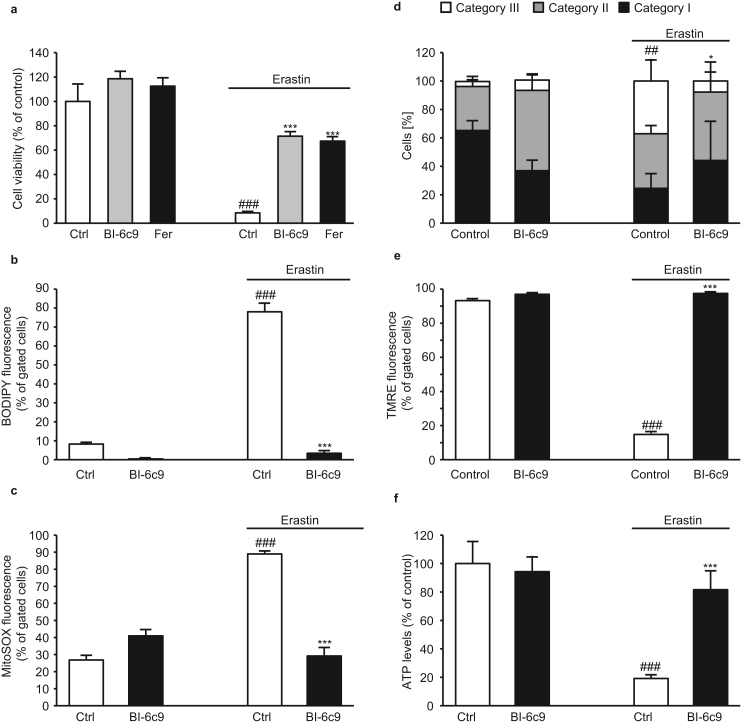

3.3. BI-6c9 inhibits erastin-induced cell death and subsequent mitochondrial damage

In order to confirm the protective effects of BID deletion, we evaluated the neuroprotective potential of the pharmacological BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 against erastin-induced ferroptosis. BI-6c9 prevented erastin-induced cell death in WT HT-22 cells to a similar exten as the ferroptosis-inhibitor ferrostatin-1 [7], which was used as a positive control (Fig. 4a). Since ferroptosis was proposed to result from formation of soluble and lipid ROS [7] we next examined formation of lipid and mitochondrial ROS. BI-6c9 fully prevented erastin-induced lipid peroxidation (Fig. 4b) and further formation of mitochondrial ROS measured via MitoSOX red staining and subsequent FACS analysis (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

BI-6c9 prevents erastin-induced cell death and mitochondrial demise. a: MTT assay revealed protection of BI-6c9 (10 µM) and ferrostatin-1 (2 µM) against erastin (1 µM, 16 h) toxicity (n=8). b: Cells were stained with BODIPY 581/591 and lipid peroxides were measured by FACS analysis after 16 h of erastin treatment (1 µM). BI-6c9 significantly reduced the lipid peroxide production (n=4/treatment condition). c: Mitochondrial ROS production was detected by MitoSOX staining and following FACS analysis. Erastin increased ROS production, which was blocked by BI-6c9 (n=4/treatment condition). d: Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in cells exposed to erastin (1 µM, 16 h) showed an increase in cells with mitochondria of category III. This erastin-induced fragmentation was fully prevented by BI-6c9. Mean values were pooled from 4 independent experiments, where mitochondrial morphology was determined from at least 500 cells per condition without knowledge of treatment history. ##p<0.01 compared to Cat III of untreated control; *p<0.05 compared to Cat III of erastin-treated cells (ANOVA, Scheffé’s test). e: Quantification of TMRE fluorescence of n=4 independent experiments showed that MMP was fully restored by BI-6c9 (10 µM) after erastin exposure (1 µM, 16 h). f: After 16 h of treatment with erastin (1 µM) ATP levels were measured. BI-6c9 prevented ATP depletion compared to erastin-treated controls (n=8). Data are shown as mean + SD. ###p<0.001 compared to untreated control; ***p<0.001 compared to erastin-treated control. (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

Comparable to genetic deletion of BID, BI-6c9 was able to inhibit mitochondrial fragmentation in response to erastin exposure (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, BI-6c9 preserved mitochondrial function which was indicated by restoration of the MMP (Fig. 4e) and the ATP levels (Fig. 4f) after erastin exposure.

Taken together, these results confirm that erastin-induced ferroptosis involves mitochondrial damage [15], [30] in neuronal HT-22 cells and substantiates the pivotal role of BID in ferroptosis which was observed before in HT-22 Bid KO cells.

3.4. Ferrostatin-1 prevents glutamate-induced cell death and preserves mitochondrial integrity

In line with earlier observations [14], the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 prevented glutamate-induced oxytosis as effective as the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 (Fig. 4b) suggesting a shared pathway of both cell death paradigms, oxytosis and ferroptosis in neuronal HT-22 cells.

To exclude an effect specific for HT-22 cells, we additionally used both erastin and glutamate in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Erastin (Supp. 1d) and glutamate (Supp. 1e) induced cell death in MEFs in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, BI-6c9 and ferrostatin-1 were able to prevent death of MEF cells in response to erastin exposure (Supp. 1f). As negative controls and to confirm the specificity of the inhibitors we used the models of H2O2-induced cell death and necroptosis induced by the combination of TNFα, SM-164 and QVD. Neither BI-6c9 nor ferrostatin-1 showed a protective effect against H2O2 (Supp. 4a) or necroptosis (Supp. 4b).

In order to support the conclusion that oxytosis and ferroptosis share common pathways in neurons, we analyzed the effects of the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 on lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial integrity in the model of oxytosis. Ferrostatin-1 was able to fully prevent glutamate-induced lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5b), the crucial step in activating BID [25].

Fig. 5.

Ferrostatin-1 inhibits glutamate-induced oxytosis and preserves mitochondrial integrity. a: MTT assay revealed protection of BI-6c9 (10 µM) and ferrostatin-1 (2 µM) against glutamate (4 mM, 16 h) toxicity (n=8). b: Cells were stained with BODIPY 581/591 and lipid peroxides were measured by FACS analysis after 16 h of glutamate treatment (3 mM). Ferrostatin-1 significantly reduced the lipid peroxide production (n=4). c: Glutamate treatment (3 mM, 16 h) increased mitochondrial ROS production, which was fully blocked by co-treatment with 2 µM ferrostatin-1 (n=4). d: Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in cells exposed to glutamate showed an increase in cells with mitochondria of category III. This glutamate-induced fragmentation was fully prevented by ferrostatin-1. ##p<0.01 compared to Cat I of glutamate-treated control; ***p<0.001 compared to Cat III of glutamate-treated cells (ANOVA, Scheffé’s test). Mean values were pooled from 4 independent experiments, where mitochondrial morphology was determined from at least 500 cells per condition without knowledge of treatment history. e: Quantification of TMRE fluorescence of n=4 independent experiments showed that MMP was fully restored by ferrostatin-1 (2 µM) after glutamate exposure (3 mM, 16 h). f: After 16 h of treatment with glutamate (3 mM) ATP levels were measured. Ferrostatin-1 prevented ATP depletion compared to glutamate-treated controls (n=8). All results are given as mean + S.D. ###p<0.001 compared to untreated control; ***p<0.001 compared to glutamate-treated control (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

Moreover, ferrostatin-1 fully blocked glutamate-induced formation of mitochondrial ROS (Fig. 5c) and further prevented glutamate-induced mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 5d). Aside from that, ferrostatin-1 (Fig. 5e) restored the MMP and prevented loss of ATP levels after induction of oxidative stress by glutamate (Fig. 5f). In order to confirm the protective effects of ferroptosis inhibition in paradigms of oxytosis, we also applied the recently described ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 [9] in the present model systems of erastin-induced ferroptosis and glutamate-induced oxytosis in HT-22 cells. In both paradigms of oxidative death, liproxstatin-1 prevented cell death, and rescued associated hallmarks of mitochondrial damage in a concentration-dependent manner and independently of GSH depletion, similar to the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9, genetic deletion of BID and the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Supp. 5 and 6). Overall, these experiments using the ferroptosis inhibitors in paradigms of glutamate-induced cell death suggest shared pathways of oxytosis and ferroptosis in neuronal cells and MEFs, which include mitochondrial damage mediated by BID.

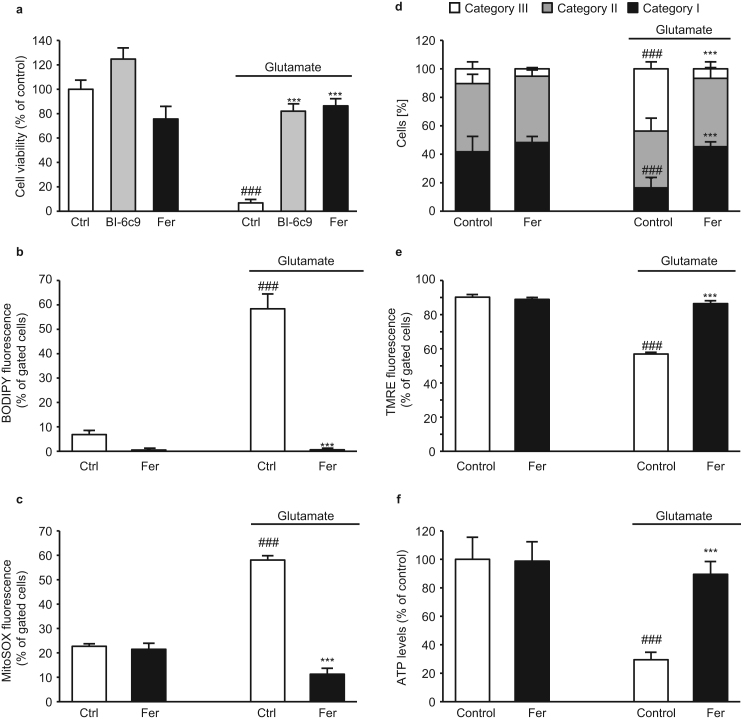

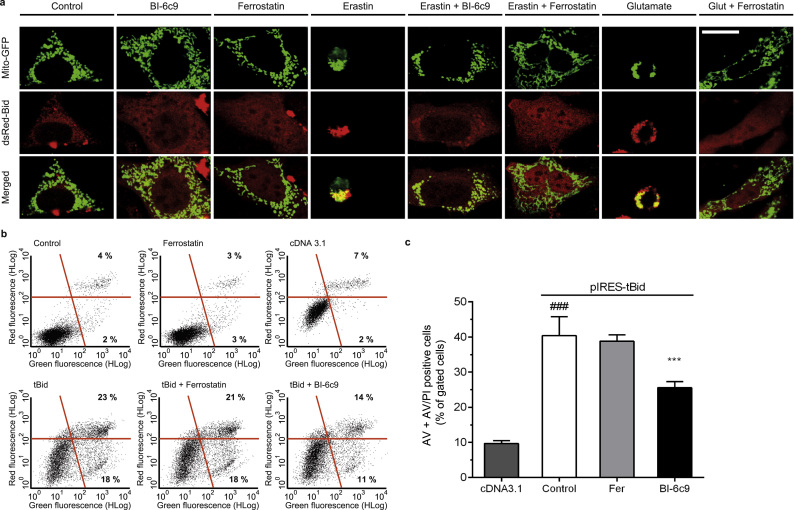

3.5. BI-6c9 and ferrostatin-1 prevent BID translocation to the mitochondria

The translocation of the pro-apoptotic protein BID to the mitochondria is considered to be crucial for the loss of MMP and the subsequent decrease of ATP levels [16]. Hence, we investigated the subcellular distribution of BID in response to erastin and glutamate-induced stress, respectively. To this end, HT-22 WT cells were co-transfected with a red-labeled BID and a mitochondrial-targeted GFP vector as described before [16], [19]. Confocal microscopy pictures reveal a translocation of BID to the mitochondria upon erastin and glutamate exposure indicated by the merging fluorescence shown in yellow and a Pearson's coefficient of r=0.78+0.18 and r=0.67+0.06 respectively. Under control conditions BID was spread all over the cytosol and did not show any co-localization with the mitochondria (r=0.31+0.05). This distribution pattern of BID was preserved in cells co-treated with ferrostatin-1 (r=0.14+0.19) or BI-6c9 (r=0.3+0.17) and erastin and in cells treated with ferrostatin-1 and glutamate (r=0.18+0.04), respectively (Fig. 6a, Supp. 7). These results indicate that the different substances, the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 and the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 prevent the translocation of BID to the mitochondria.

Fig. 6.

Bid links ferroptosis to mitochondrial cell death. a: Confocal microscopy pictures revealed translocation of BID (Bid-dsRed) to the mitochondria (MitoGFP) after erastin (1 µM, 16 h) or glutamate (3 mM, 16 h) exposure, which was fully blocked by BI-6c9 or ferrostatin-1 co-treatment. Scale bar: 20 µM. b: tBID-induced cell death (2 µg plasmid/24-well, 24 h) in HT-22 cells was analyzed by co-staining of cells with Annexin V (Green fluorescence) and PI (Red fluorescence) and subsequent FACS-analysis. Pre-incubation for 1 h with 10 µM BI-6c9 prevented pIRES-tBid-induced cell death, while ferrostatin-1 did not (representative dot plots). The empty vector pcDNA3.1 was used as a control plasmid. Numbers in the representative dot blots show percentage of AV positive cells (lower right) and AV+PI positive cells (upper right) (n=4) c: Quantification of dot plots shown in b (n=4). Data are shown as mean + S.D. ###p<0.001compared to cDNA 3.1; ***p<0.001compared to pIRES-tBid-transfected control (ANOVA, Scheffé‘s test).

3.6. The BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 but not ferrostatin-1 affects tBID-induced cell death

In order to shed more light on the direct effects of both inhibitors, BI-6c9 and ferrostatin-1, we applied a model of tBID-overexpression in the HT-22 WT cell line. Following previously established protocols [19], [25], we transfected HT-22 cells with a tBID-encoding plasmid and analyzed cell viability 24 h after the transfection. Annexin V/PI staining revealed that BI-6c9 significantly reduced tBID-induced cytotoxicity similar to earlier findings [19], while ferrostatin-1 failed to protect HT-22 cells from tBID toxicity (Fig. 6b, c).

These results indicate that mitochondrial transactivation of BID is the key decision point of cell death connecting the mechanisms of ferroptosis and oxytosis in neuronal cells. Once activated, the detrimental activity of BID cannot be stopped by inhibitors of ferroptosis such as ferrostatin-1 that act upstream of the fatal BID transactivation and associated mitochondrial demise.

Assuming oxytosis and ferroptosis to share common mechanistic hallmarks, apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) translocation, which is essential for cell death in oxytosis, was expected to be required for ferroptosis as well. Therefore we depleted WT HT-22 cells of AIF by siRNA and analyzed cell viability upon glutamate or erastin challenge by real-time impedance measurements. We found AIF depleted cells to be protected against cell death compared to control siRNA conditions (Supp. 8).

4. Discussion

The present study exposes BID as a key link of death signaling pathways of ferroptosis and oxytosis to mitochondrial damage in neuronal cells. Erastin induced morphological and functional damage of mitochondria such as enhanced fragmentation, increased formation of mitochondrial ROS, loss of MMP and ATP depletion in a very similar pattern as the hallmarks of oxytosis triggered by glutamate in the neuronal HT-22 cells [12], [13], [16], [19], [25]. Further, using CRISPR/Cas9 technology for genetic BID deletion and the pharmacological BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 we identified a key role for BID in mediating the hallmarks of erastin toxicity. Vice versa, the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 blocked BID transactivation, mitochondrial fragmentation and the loss of MMP after glutamate exposure in neuronal cells, confirming that oxytosis and ferroptosis share detrimental mechanisms of ROS formation upstream of BID-dependent mitochondrial demise.

It has been established that both forms of death pathways, oxytosis and ferroptosis induced by glutamate and erastin, respectively, involve very similar mechanisms, i.e. inhibition of the Xc- system, GSH depletion and subsequent lipid peroxidation [8]. In both model systems Gpx4 is considered as an important negative regulator of lipid peroxidation [21], [29]. In contrast to glutamate, which in neuronal HT-22 cells acts as a competitive inhibitor of cystine import through Xc-, erastin was supposed to mediate direct detrimental effects at the mitochondria [15], [30], [7]. For example, erastin altered the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane via interaction with particular isoforms of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) thereby inducing mitochondria-triggered oxidative cell death in tumor cells [28]. Notably, Dixon and coworkers observed erastin-induced alterations of mitochondrial morphology, but could not detect any formation of mitochondrial ROS in their experimental settings [7], whereas Yuan et al. observed the induction of mitochondrial ROS by erastin [30].

In contrast, the present study clearly indicates that mitochondrial damage is a prerequisite for cell death pathways of ferroptosis in neuronal cells. In particular, the observed translocation of fluorescently labeled BID in erastin-exposed cells suggested a major role for this pro-apoptotic protein in ferroptosis. This conclusion was further confirmed by protective effects of the BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 and Bid knockout in the model system of ferroptosis in neural cells, which contrasts previous observations in cancer cells where BID was not required for erastin-induced toxicity [7]. Downstream events of BID transactivation such as mitochondrial ROS formation, drop of MMP and ATP were detected here, thereby confirming erastin-induced mitochondrial demise in neuronal cells.

Our findings are in line with earlier studies exposing a pivotal role for BID transactivation to mitochondria in neuronal cell death, in models of glutamate excitotoxicity and oxygen glucose-deprivation, and, furthermore, in vivo, in models of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma [1], [12], [13], [16], [2], [20], [5]. In particular, our previous work demonstrated that BID mediated mitochondrial fragmentation in neurons through enhanced mitochondrial recruitment of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp-1), a GTPase that mediates mitochondrial fission [12]. Further, BID was shown to mediate enhanced mitochondrial ROS production and loss of mitochondrial membrane integrity as demonstrated by measurements of MMP and mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor in the model of glutamate-induced oxytosis [16], [25].

The current study suggests that the concept of BID-mediated mitochondrial damage in oxytosis can be also transferred to mechanisms of ferroptosis in neuronal cells. In fact, inhibition of BID blocked the detrimental effects of erastin at the level of mitochondria. Notably, ferrostatin-1 failed to prevent tBID-induced cell death, suggesting that BID serves as a sensor for iron-dependent generation of oxidative stress and BID transactivation to mitochondria as the “point of no return” determines neuronal death [10]. Our data strongly suggest that oxytosis and ferroptosis share common mechanisms upstream of BID transactivation and mitochondrial damage, since ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 were able to prevent formation of ROS, transactivation of BID and the associated mitochondrial damage, and neuronal death in the model of glutamate-induced oxytosis.

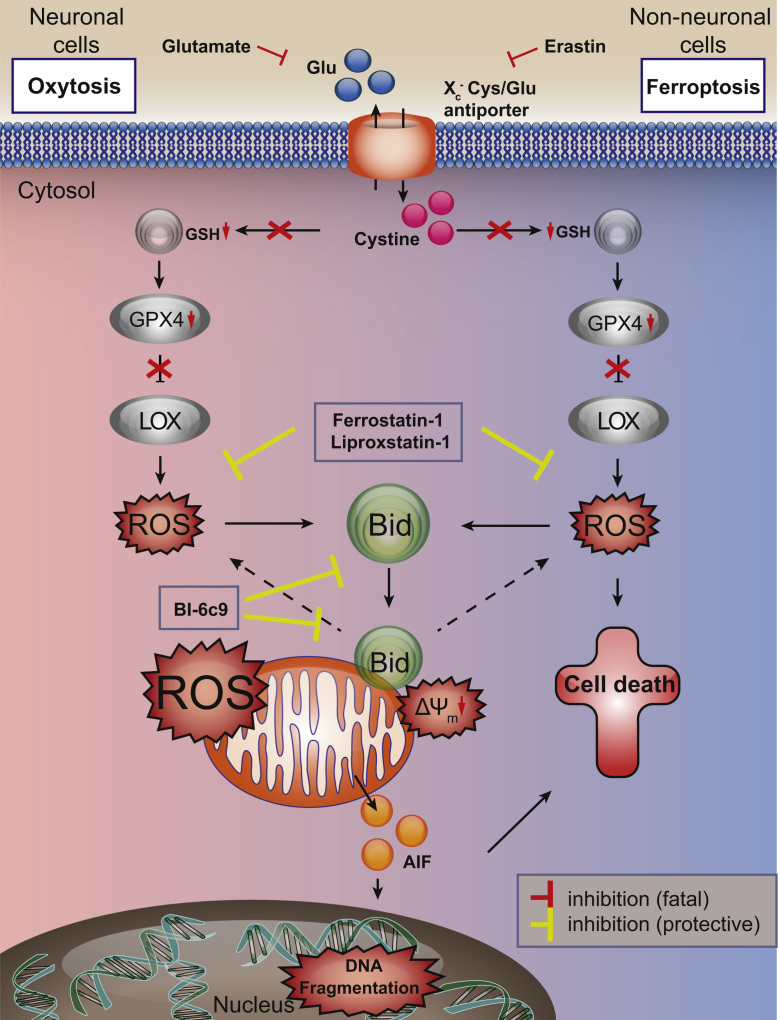

In conclusion, our data suggest that ferroptosis in neurons is merged with pathways of oxytosis through BID transactivation to mitochondria (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Different signaling pathways and additional control points of cell death are expected in neurons in comparison to other cell types, in particular in comparison to highly proliferating cancer cells because neurons are highly differentiated and specialized cells which have to maintain function and viability throughout the lifespan of the organism, which means e.g. for more than 80 years in humans. During such a lifespan highly differentiated neurons are exposed to a number of stress insults, including oxidative stress, which has been associated as a leading mechanism in ageing and age-related neurodegenerative diseases [3], [4]. Our present findings support the view that BID-mediated mitochondrial damage is a prerequisite for death signaling in neurons in paradigms of severe oxidative stress. Such BID-dependent mitochondrial death pathways involve fragmentation of the organelles, impaired ATP synthesis, and loss of MMP and mitochondrial membrane integrity resulting in the release of pro-apoptotic factors such as cytochrome c, endonuclease G and AIF [10].

Fig. 7.

Bid links ferroptosis to neuronal oxytosis. Glutamate and erastin inhibit the Xc--antiporter in paradigms of oxytosis and ferroptosis, respectively. Blocking the cellular cystine import results in decreased GSH levels and reduced Gpx4 activity, and the subsequent activation of 12/15 LOX mediates significant formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In erastin-induced ferroptosis cell death is induced through oxidative stress and independently of mitochondrial demise. In neuronal cells, ROS-induced transactivation of BID to the mitochondria links both pathways of oxytosis and ferroptosis, and causes mitochondrial ROS formation that is associated with irreversible morphological and functional damage, e.g. loss of MMP, decline of ATP levels and release of apoptosis inducing factor (AIF). The BID-inhibitor BI-6c9 and the ferroptosis inhibitors ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 are able to block these fatal pathways upstream of mitochondrial impairments. BI-6c9 directly inhibits BID and its detrimental effects at the level of mitochondria while ferrostatin-1 acts upstream of BID preventing ROS formation through 12/15 LOX.

Overall, the present study exposes BID as the molecular link between the previously separated pathways of oxidative stress signaling by merging the death pathways of ferroptosis and oxytosis at the level of mitochondria, i.e. the crucial point of decision for neuronal function and survival. This concept of merged death pathways of oxytosis and ferroptosis in neurons may provide new therapeutic approaches as intervention strategies may prove successful in preventing neuronal death at different levels of cellular stress. Such approaches may include ferroptosis inhibitors, inhibitors of lipid peroxidation, and, in particular, strategies of mitochondrial protection through inhibition of BID.

Author contributions

S.O. and C.C. initiated the project. S.N., A.J., S.O. and C.C. conceived, designed and supervised the experiments. S.N., A.J., S.O., V.L., L.H., I.E., G.G., and A.D. performed the experiments. S.N., A.J., S.O. and C.C. evaluated the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing personal or financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marcus Conrad for providing Liproxstatin-1 and advisory comments and discussion on the manuscript. We also thank the master students Charlotte Bold and Mirjam Montag for experimental support in the initial phase of the project and Maren Richter for additional supervision, Katharina Elsässer for her excellent technical support and Emma Esser for careful editing of the manuscript. This work was partly supported by a DFG grant to CC (DFG-FOR2107). AMD is a recipient of a Rosalind-Franklin fellowship, co-funded by EU and University of Groningen.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Becattini B., Culmsee C., Leone M., Zhai D., Zhang X., Crowell K.J., Rega M.F., Landshamer S., Reed J.C., Plesnila N., Pellecchia M. Structure-activity relationships by interligand NOE-based design and synthesis of antiapoptotic compounds targeting Bid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12602–12606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603460103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermpohl D., You Z., Korsmeyer S.J., Moskowitz M.A., Whalen M.J. Traumatic brain injury in mice deficient in Bid: effects on histopathology and functional outcome. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2006;26:625–633. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabrese V., Cornelius C., Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Calabrese E.J., Mattson M.P. Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:1763–1811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culmsee C., Landshamer S. Molecular insights into mechanisms of the cell death program: role in the progression of neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:269–283. doi: 10.2174/156720506778249461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culmsee C., Zhu C., Landshamer S., Becattini B., Wagner E., Pellecchia M., Pellechia M., Blomgren K., Plesnila N. Apoptosis-inducing factor triggered by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and Bid mediates neuronal cell death after oxygen-glucose deprivation and focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005;25:10262–10272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diemert S., Dolga A.M., Tobaben S., Grohm J., Pfeifer S., Oexler E., Culmsee C. Impedance measurement for real time detection of neuronal cell death. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2012;203:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon S.J., Lemberg K.M., Lamprecht M.R., Skouta R., Zaitsev E.M., Gleason C.E., Patel D.N., Bauer A.J., Cantley A.M., Yang W.S., Morrison B., Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon S.J., Stockwell B.R. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angeli Friedmann, Pedro Jose, Schneider M., Proneth B., Tyurina Y.Y., Tyurin V.A., Hammond V.J., Herbach N., Aichler M., Walch A., Eggenhofer E., Basavarajappa D., Rådmark O., Kobayashi S., Seibt T., Beck H., Neff F., Esposito I., Wanke R., Förster H., Yefremova O., Heinrichmeyer M., Bornkamm G.W., Geissler E.K., Thomas S.B., Stockwell B.R., O'Donnell V.B., Kagan V.E., Schick J.A., Conrad M. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galluzzi L., Blomgren K., Kroemer G. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in neuronal injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:481–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gohil V.M., Sheth S.A., Nilsson R., Wojtovich A.P., Lee J.H., Perocchi F., Chen W., Clish C.B., Ayata C., Brookes P.S., Mootha V.K. Nutrient-sensitized screening for drugs that shift energy metabolism from mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:249–255. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grohm J., Kim S.-W., Mamrak U., Tobaben S., Cassidy-Stone A., Nunnari J., Plesnila N., Culmsee C. Inhibition of Drp1 provides neuroprotection in vitro and in vivo. Cell death Differ. 2012;19:1446–1458. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grohm J., Plesnila N., Culmsee C. Bid mediates fission, membrane permeabilization and peri-nuclear accumulation of mitochondria as a prerequisite for oxidative neuronal cell death. Brain, Behav., Immun. 2010;24:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang Y., Tiziani S., Park G., Kaul M., Paternostro G. Cellular protection using Flt3 and PI3Kα inhibitors demonstrates multiple mechanisms of oxidative glutamate toxicity. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3672. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krainz T., Gaschler M.M., Lim C., Sacher J.R., Stockwell B.R., Wipf P. A mitochondrial-targeted nitroxide Is a potent inhibitor of ferroptosis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016;2:653–659. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landshamer S., Hoehn M., Barth N., Duvezin-Caubet S., Schwake G., Tobaben S., Kazhdan I., Becattini B., Zahler S., Vollmar A., Pellecchia M., Reichert A., Plesnila N., Wagner E., Culmsee C. Bid-induced release of AIF from mitochondria causes immediate neuronal cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1553–1563. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linkermann A., Skouta R., Himmerkus N., Mulay S.R., Dewitz C., Zen F., de, Prokai A., Zuchtriegel G., Krombach F., Welz P.-S., Weinlich R., Vanden Berghe T., Vandenabeele P., Pasparakis M., Bleich M., Weinberg J.M., Reichel C.A., Bräsen J.H., Kunzendorf U., Anders H.-J., Stockwell B.R., Green D.R., Krautwald S. Synchronized renal tubular cell death involves ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16836–16841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415518111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattson M.P., Gleichmann M., Cheng A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron. 2008;60:748–766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oppermann S., Schrader F.C., Elsässer K., Dolga A.M., Kraus A.L., Doti N., Wegscheid-Gerlach C., Schlitzer M., Culmsee C. Novel N-phenyl-substituted thiazolidinediones protect neural cells against glutamate- and tBid-induced toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014;350:273–289. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plesnila N., Zinkel S., Le D.A., Amin-Hanjani S., Wu Y., Qiu J., Chiarugi A., Thomas S.S., Kohane D.S., Korsmeyer S.J., Moskowitz M.A. BID mediates neuronal cell death after oxygen/ glucose deprivation and focal cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:15318–15323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261323298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seiler A., Schneider M., Förster H., Roth S., Wirth E.K., Culmsee C., Plesnila N., Kremmer E., Rådmark O., Wurst W., Bornkamm G.W., Schweizer U., Conrad M. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 2008;8:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speer R.E., Karuppagounder S.S., Basso M., Sleiman S.F., Kumar A., Brand D., Smirnova N., Gazaryan I., Khim S.J., Ratan R.R. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylases as targets for neuroprotection by "antioxidant" metal chelators: from ferroptosis to stroke. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;62:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan S., Sagara Y., Liu Y., Maher P., Schubert D. The regulation of reactive oxygen species production during programmed cell death. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:1423–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan S., Schubert D., Maher P. Oxytosis: a novel form of programmed cell death. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2001;1:497–506. doi: 10.2174/1568026013394741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobaben S., Grohm J., Seiler A., Conrad M., Plesnila N., Culmsee C. Bid-mediated mitochondrial damage is a key mechanism in glutamate-induced oxidative stress and AIF-dependent cell death in immortalized HT-22 hippocampal neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:282–292. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Leyen K., Kim H.Y., Lee S.-R., Jin G., Arai K., Lo E.H. Baicalein and 12/15-lipoxygenase in the ischemic brain. Stroke : J. Cereb. Circ. 2006;37:3014–3018. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000249004.25444.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie Y., Hou W., Song X., Yu Y., Huang J., Sun X., Kang R., Tang D. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:369–379. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yagoda N., Rechenberg M. von, Zaganjor E., Bauer A.J., Yang W.S., Fridman D.J., Wolpaw A.J., Smukste I., Peltier J.M., Boniface J.J., Smith R., Lessnick S.L., Sahasrabudhe S., Stockwell B.R. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 2007;447:864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W.S., SriRamaratnam R., Welsch M.E., Shimada K., Skouta R., Viswanathan V.S., Cheah J.H., Clemons P.A., Shamji A.F., Clish C.B., Brown L.M., Girotti A.W., Cornish V.W., Schreiber S.L., Stockwell B.R. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan H., Li X., Zhang X., Kang R., Tang D. CISD1 inhibits ferroptosis by protection against mitochondrial lipid peroxidation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;478:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material