Abstract

The notion that oxidative stress plays a role in virtually every human disease and environmental exposure has become ingrained in everyday knowledge. However, mounting evidence regarding the lack of specificity of biomarkers traditionally used as indicators of oxidative stress in human disease and exposures now necessitates re-evaluation. To prioritize these re-evaluations, published literature was comprehensively analyzed in a meta-analysis to quantitatively classify the levels of systemic oxidative damage across human disease and in response to environmental exposures.

In this meta-analysis, the F2-isoprostane, 8-iso-PGF2α, was specifically chosen as the representative marker of oxidative damage. To combine published values across measurement methods and specimens, the standardized mean differences (Hedges’ g) in 8-iso-PGF2α levels between affected and control populations were calculated.

The meta-analysis resulted in a classification of oxidative damage levels as measured by 8-iso-PGF2α across 50 human health outcomes and exposures from 242 distinct publications. Relatively small increases in 8-iso-PGF2α levels (g<0.8) were found in the following conditions: hypertension (g=0.4), metabolic syndrome (g=0.5), asthma (g=0.4), and tobacco smoking (g=0.7). In contrast, large increases in 8-iso-PGF2α levels were observed in pathologies of the kidney, e.g., chronic renal insufficiency (g=1.9), obstructive sleep apnoea (g=1.1), and pre-eclampsia (g=1.1), as well as respiratory tract disorders, e.g., cystic fibrosis (g=2.3).

In conclusion, we have established a quantitative classification for the level of 8-iso-PGF2α generation in different human pathologies and exposures based on a comprehensive meta-analysis of published data. This analysis provides knowledge on the true involvement of oxidative damage across human health outcomes as well as utilizes past research to prioritize those conditions requiring further scrutiny on the mechanisms of biomarker generation.

Abbreviations: EBC, exhaled breath condensate; 8-iso-PGF2α, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α; SMD, standardized mean difference; RIA, radio-immunoassay

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Oxidative stress, Oxidative damage, F2-isoprostane, Ranking

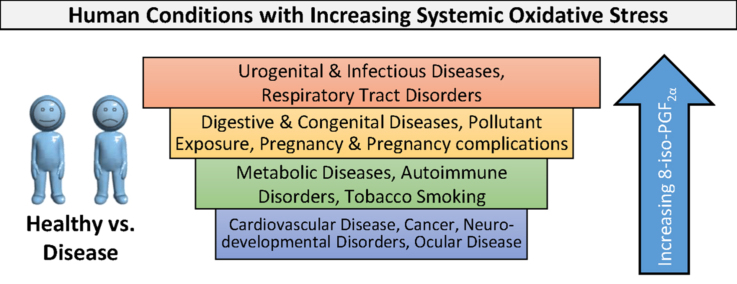

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Oxidative damage is highly variable in human conditions as measured by F2-isoprostanes.

-

•

Respiratory tract and urogenital diseases have the highest F2-isoprostanes.

-

•

Cancer and cardiovascular diseases have surprisingly low F2-isoprostanes.

1. Introduction

The role of oxidative damage in human disease, non-physical stress, xenobiotic exposure, and aging has been extensively investigated in nearly 22,000 publications as of 2015. Despite this massive amount of research, the importance of increased oxidative damage to pathologies and toxicities is critically debated. This is especially true due to the increasing evidence for potential ambiguity in the specificity of the most popular biomarker of oxidative stress, the F2-isoprostane 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) [1], [2].

The 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α is a lipid peroxidation product of arachidonic acid and was identified through coordinated experimental studies led by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] as the most useful biomarker of oxidative damage [8], [9]. However, mounting evidence shows that 8-iso-PGF2α can be formed not only through oxidative stress but also simultaneously by the prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase enzymes which are induced during inflammation [1], [2]. The problem with the specificity of this biomarker now necessitates additional work to determine the true mechanism by which the increases in the F2-isoprostane levels occur. To prioritize the efforts to confirm the true mechanism of F2-isoprostane generation for each condition, a comprehensive meta-analysis of past research is needed.

To perform the meta-analysis, quantitative information on F2-isoprostane concentration in human specimens, specifically 8-iso-PGF2α, was collected from over two hundred publications. These data were used to calculate the standardized mean difference in 8-iso-PGF2α (Hedges' g) between groups (affected and control or exposed and unexposed). The Hedges’ g was used to rank the evidence for involvement of oxidative stress across the diseases and exposures studied [10].

This first comprehensive and quantitative classification of the published evidence provides an unbiased review of the occurrence of oxidative damage as measured by 8-iso- PGF2α in association with adverse health outcomes and chemical exposures. In addition, the magnitude of Hedges' g for each condition provides a clue to the potential importance of oxidative damage and prioritizes those conditions in which the F2-isoprostane generation mechanism should be re-evaluated first.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection and inclusion criteria

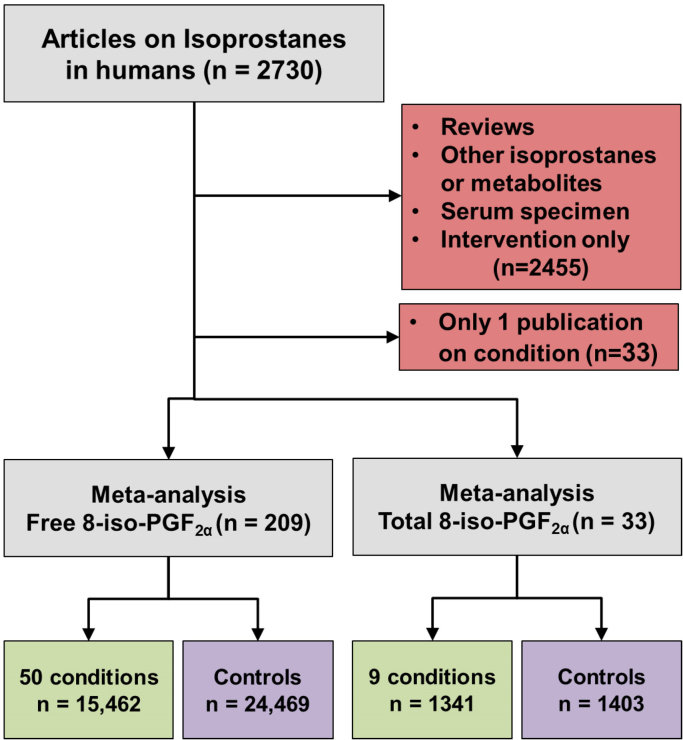

An electronic search for the term “biomarkers of oxidative stress” was performed in the Thomas Reuters Web of Knowledge database. This initial search was then refined by searching specifically for the F2-isoprostanes and, more specifically, 8-iso-PGF2α. Results from multiple acronyms and abbreviations were combined as multiple names and abbreviations are common for these biomarkers, especially in earlier publications. The following terms were included: F2-isoprostane, 8-isoprostane, 8-iso-PGF2α, 8-epi-PGF2α, 15-F2t-isoprostane, iPF2α-III, and isoprostane. The selection of studies from this set for inclusion into the meta-analysis was limited to those reporting the mean and standard deviation of free or total 8-iso-PGF2α. Numeric data were gathered directly from tables or, when presented in graphs only, were inferred by digitizing the figure with Plot Digitizer for Windows by Joseph A. Huwaldt.1 Numeric data collected included mean, geometric mean, standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE), interquartile range (IQR), 95% confidence interval, and number of participants (n). Geometric mean and mean were used without modification. The measures of variation in the mean were converted to standard deviation prior to calculation of Hedges' g. Standard error was assumed to be SD=SE*. Interquartile range was assumed to be SD=IQR/1.35. The 95% confidence interval was assumed to be SD=. Except for serum, all biological specimens were included in the analysis. Serum is not an appropriate specimen for F2-isoprostane measurement because during the clotting process 8-iso-PGF2α is generated ex vivo by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase [11]. No restrictions were placed on measurement methodology. Additional publications were found through the reference sections of already included publications. Studies reporting the effect of interventions or review articles were excluded. Conditions for which only a single publication could be found were also excluded from the final analysis. Ultimately, literature searches resulted in a total of 2730 unique publications on F2-isoprostanes in humans (Fig. 1). The above stated criteria excluded 2455 out of the 2730 publications. In addition, 33 publications for free 8-iso-PGF2α were excluded since there was only one report for the studied condition (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, epilepsy, hyperthyroidism, and others). This left 209 publications reporting free 8-iso-PGF2α levels and 33 reporting total 8-iso-PGF2α levels to be included in the meta-analysis. The raw data from each publication can be found in Mendeley dataset doi:10.17632/g42s55594f.1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the process for inclusion and exclusion of publications into the meta-analysis. N in parentheses represents the number of publications in each step, whereas the end totals represent the sum of all individuals measured for free or total 8-iso-PGF2α.

2.2. Meta-analysis and sensitivity analyses

Extracted mean or geometric mean, standard deviation, and number of participants were used to compute the standardized mean difference (Hedges' g) and 95% confidence intervals using R version 3.2.2 with the software package “meta” [12], [13]. Studies reporting different grades or severities of disease were combined to form a single estimate per the method of Borenstein et al. [14]. The fixed-effects model was used for the meta-analysis and applied to each subgroup (i.e., disease or exposure) with inverse variance weighting of individual studies [15], [16]. The DerSimonian-Laird estimator was used for each subgroup as a measure of heterogeneity [17]. Sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of the specimens were performed using the “leave-one-out” approach [18]. For this, all data in the meta-analysis was combined in a random-effects model and used as the control. Subsequently, all data with one type of specimen (e.g., plasma) were removed, the random-effects model of the remaining data was calculated, and the differences were compared to the control using a t-test. Publication bias was investigated using a funnel plot, which was subsequently tested for asymmetry using a linear regression analysis [19].

3. Results

3.1. Free 8-iso-PGF2α

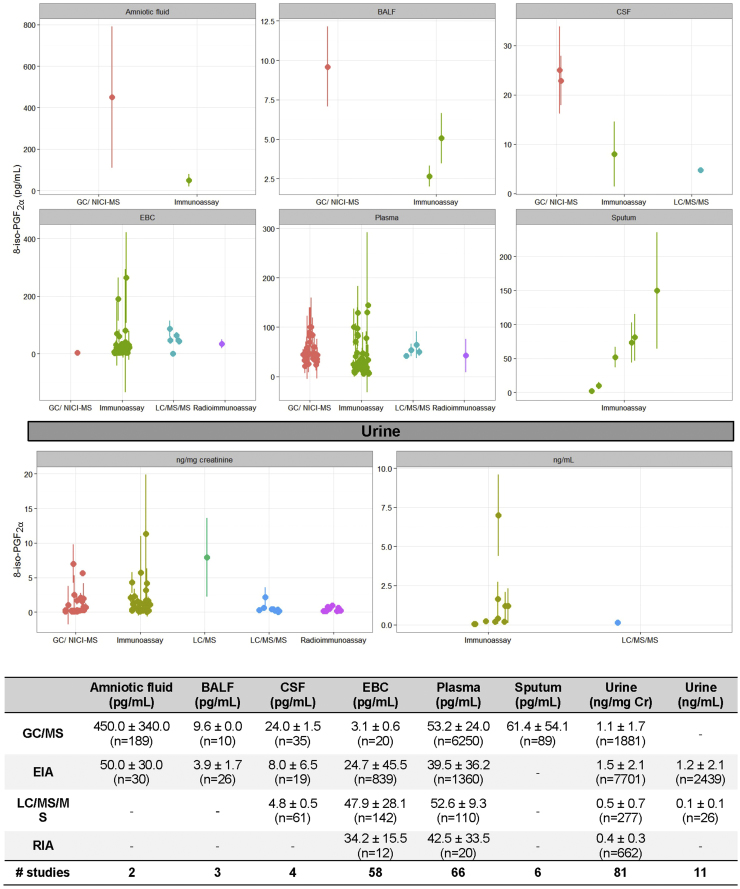

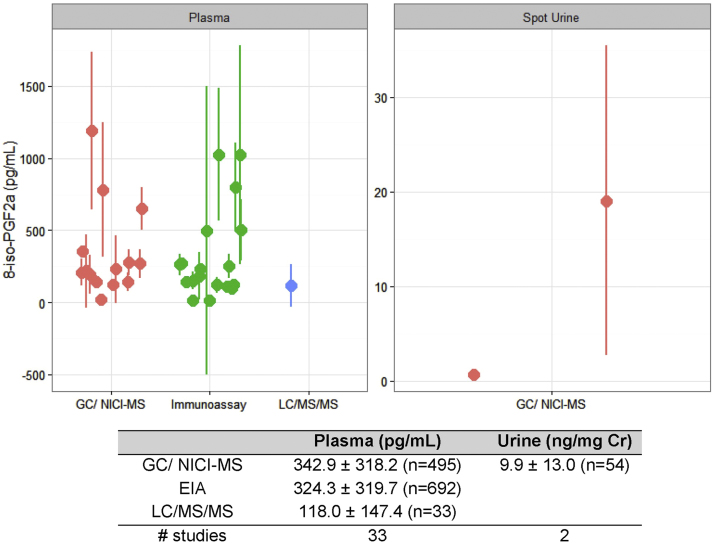

Free 8-iso-PGF2α has been the most commonly measured F2-isoprostane to date. When data from all non-diseased individuals in the meta-analysis were combined, a typical concentration for free 8-iso-PGF2α emerged (Fig. 2). Across types of specimens, urine has the highest average concentration of free 8-iso-PGF2α, 1200±600 pg/mL (1.3±0.8 ng/mg creatinine). On average, ~100-fold less free 8-iso-PGF2α is detected in plasma (45.1±18.4 pg/mL) and exhaled breath condensate (EBC) (30.9±17.2 pg/mL). In addition to these specimens, 8-iso-PGF2α is detected in amniotic fluid, bronchiolar alveolar lavage fluid, cerebral spinal fluid, and sputum.

Fig. 2.

Free 8-iso-PGF2α amounts in reported healthy individuals separated by analytical technique and specimen. Data in the graph and table show mean±standard deviation. The number in parentheses is the sum of individuals analyzed per group. The number of studies represents the unique number of publications per group.

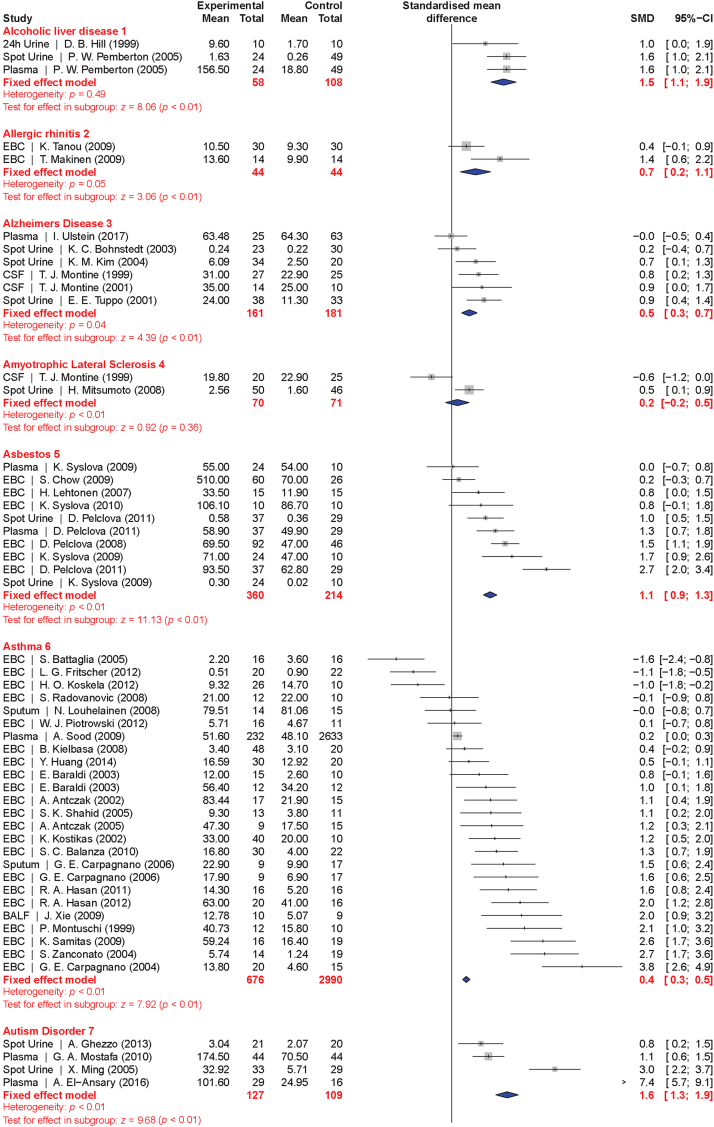

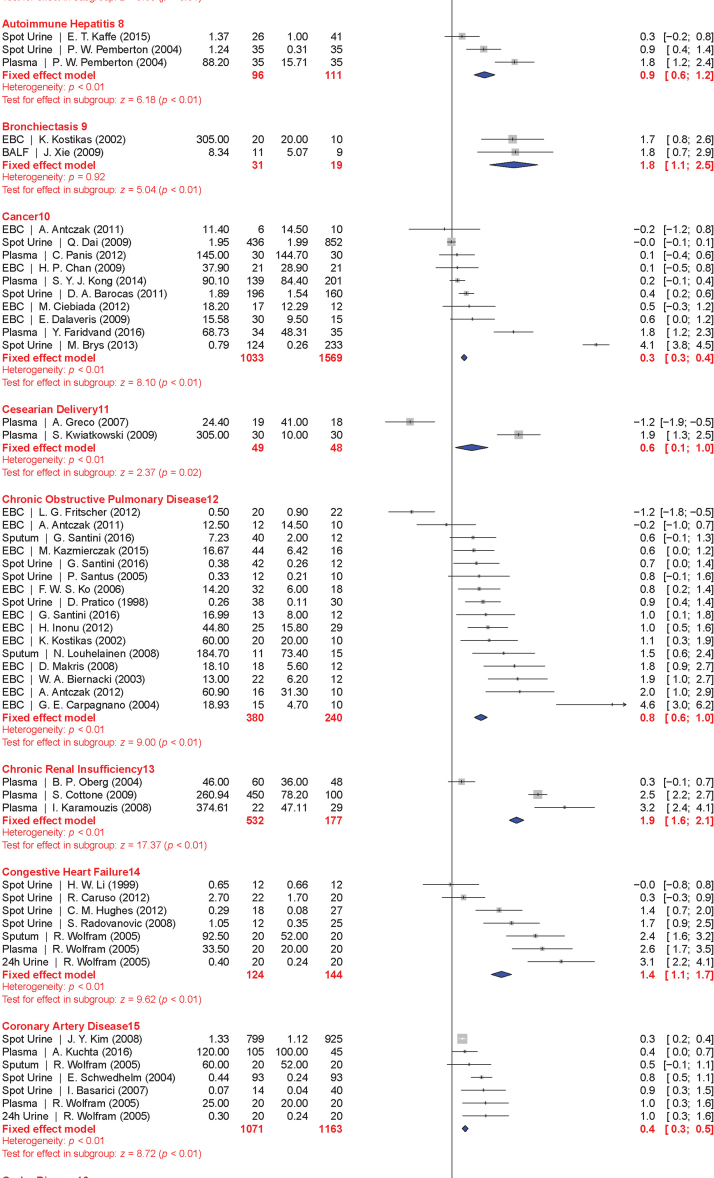

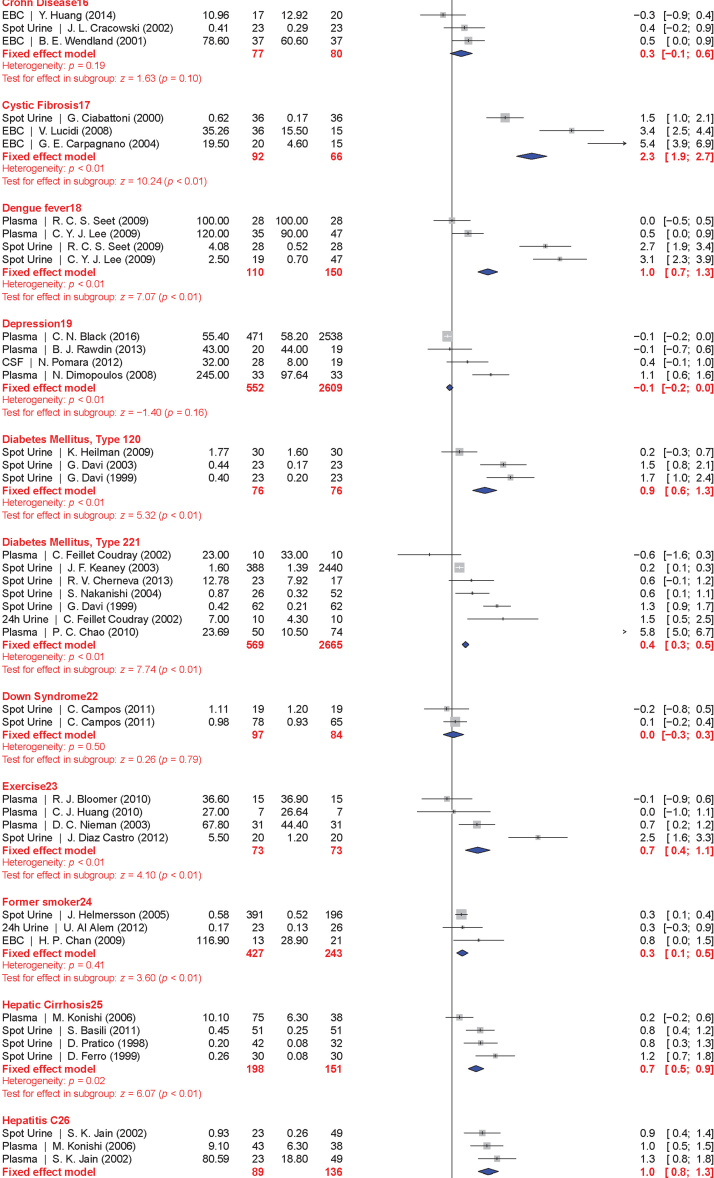

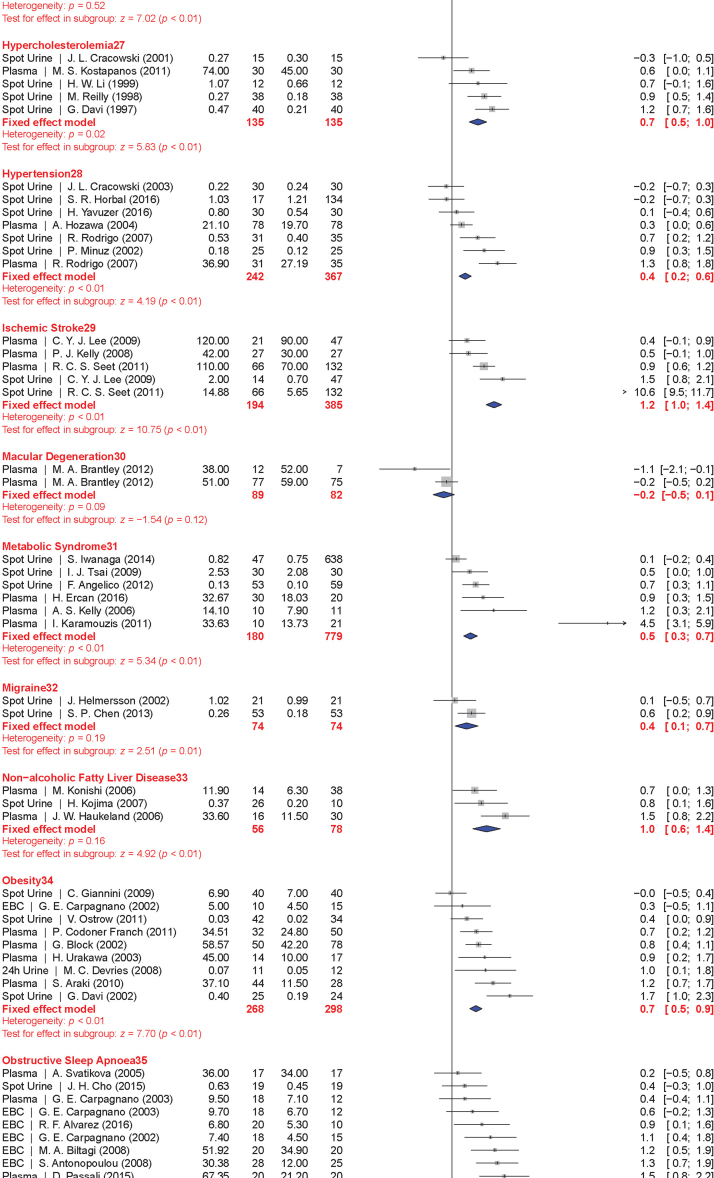

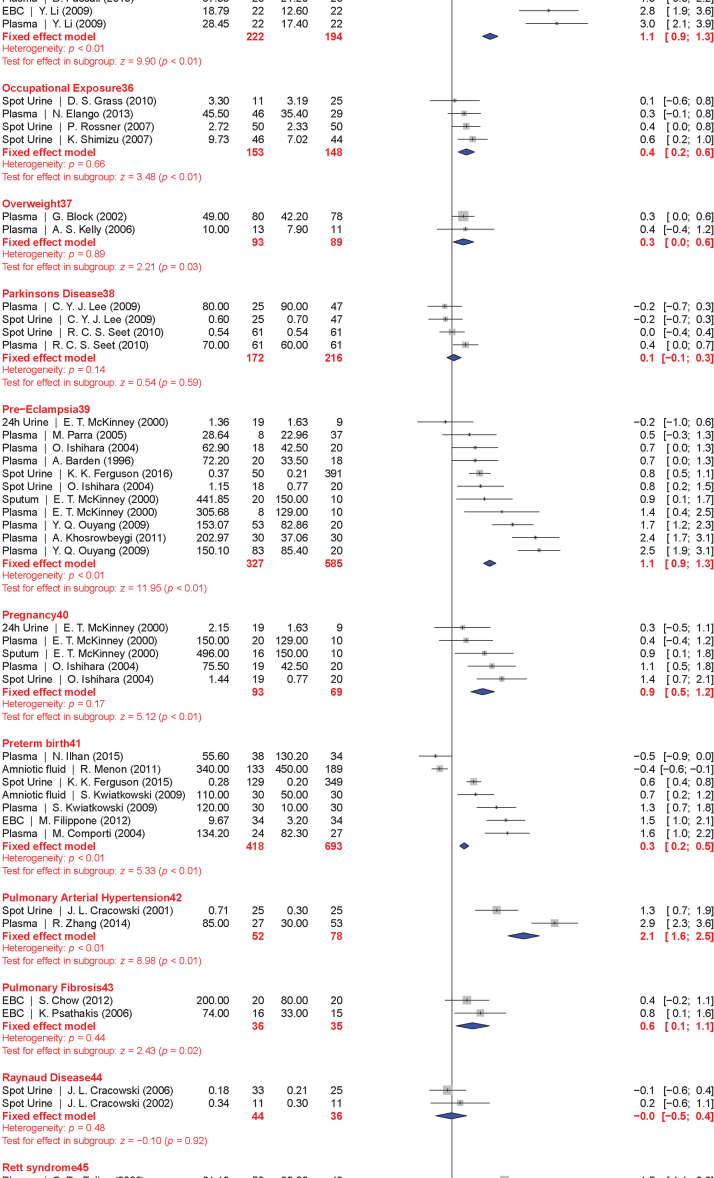

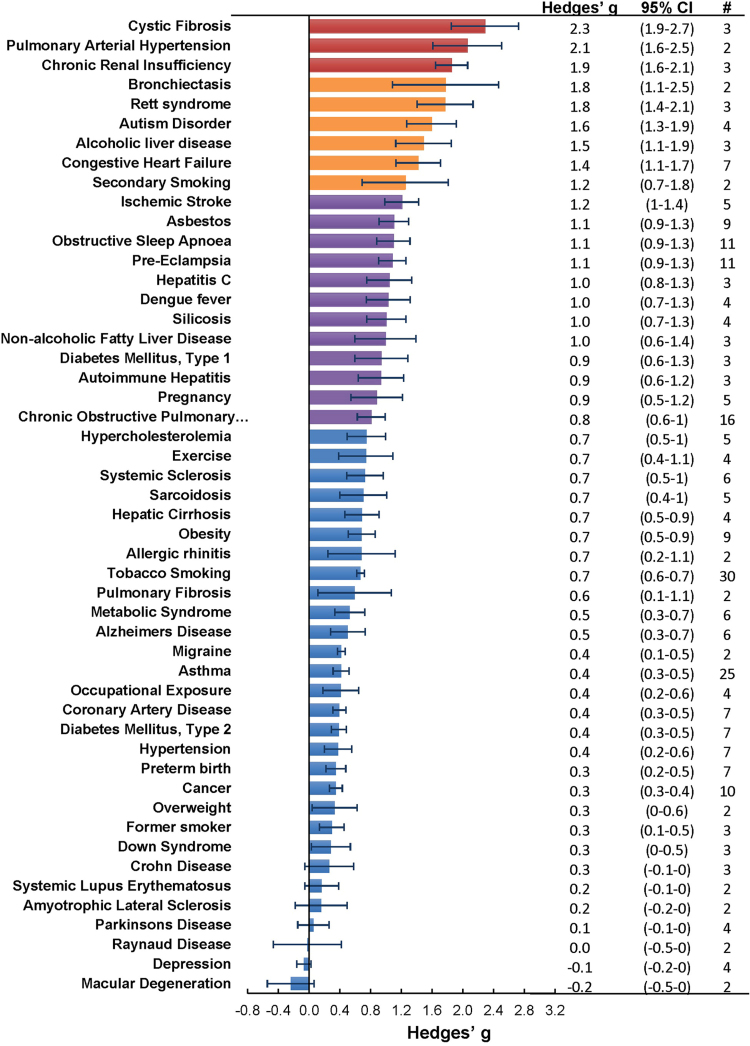

The meta-analysis included a total of 50 conditions ranging from diseases, to exposure to xenobiotics, to pregnancy and exercise. A Forest plot of all the data graphically illustrates the calculated Hedges' g for all 50 conditions (Fig. 3). All studies compared a non-affected population to an affected population of similar age. Studies of pre-eclampsia had a comparison group consisting of pregnant women without complications. To generate the ranking, we selected and ordered all conditions based on their Hedges' g value (Fig. 4). A small effect is considered to be a Hedges' g value smaller than 0.8 [20].

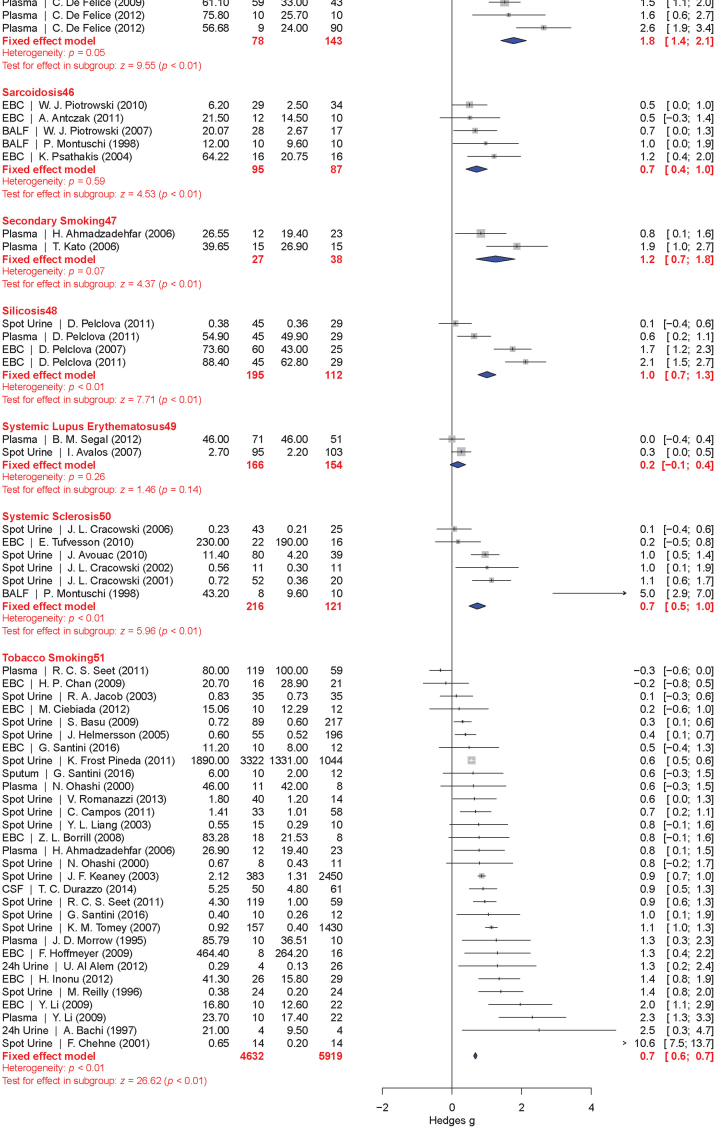

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of all calculated standardized mean differences for free 8-iso-PGF2α subdivided by condition. The standardized mean difference is Hedges' g. Fixed-effects model results are plotted in the blue diamonds. These are calculated for each subgroup with inverse variance weighting of individual studies. DerSimonian-Laird estimators are used for the heterogeneity calculation. The test for effect in subgroup statistically determines whether the effect size is greater than 0. Number in the affected and control groups represents the number of people tested. Data for this figure was extracted from references [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212], [213], [214], [215], [216], [217], [218], [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], [224], [225], [226], [227], [228], [229], [230], [231], [232], [233], [234], [235], [236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241], [242], [243], [244], [245], [246], [247], [248], [249], [250], [251], [252], [253], [254], [255], [256], [257], [258], [259], [260], [261], [262], [263], [264] (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

Fig. 4.

Ranking of conditions where free 8-iso-PGF2α is generated in significantly greater amounts compared to the control population. Hedges' g ±95% confidence intervals calculated from the fixed effects model plotted as a rank order. The # column represents the number of studies per condition.

When grouped together in categories, conditions having a relatively small increase in free 8-iso-PGF2α levels (g<0.8) included: neurodevelopmental disorders (g=0.16±0.10), cancer (g=0.35±0.15), cardiovascular diseases (g=0.41±0.30), tobacco smoking (current smoker is g=0.67±0.20, former smoker is g=0.29±0.15), metabolic diseases (g=0.68±0.30), and autoimmune disorders (g=0.70±0.30). In contrast, larger quantitative effects were observed in pregnancy (g=0.88±0.22), digestive system diseases (g=0.99±0.22), exposure to environmental contaminants (e.g., asbestos, occupational exposure, and silicosis; g=1.00±0.35), infectious diseases (g=1.03±0.30), respiratory tract disorders (g=1.10±0.40), congenital diseases (g=1.03±0.40), and urogenital diseases (g=1.85±0.20).

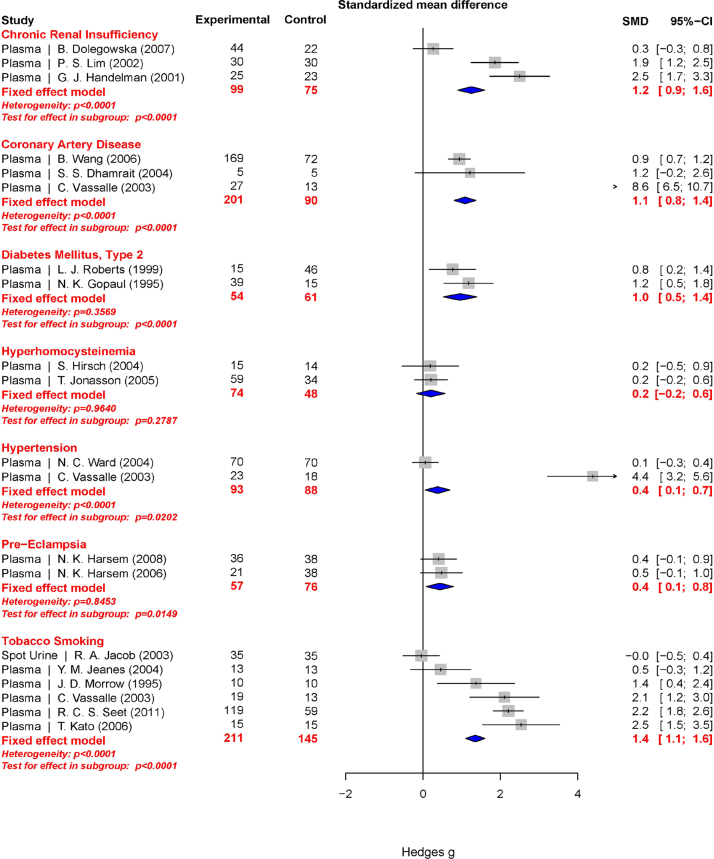

3.2. Total 8-iso-PGF2α

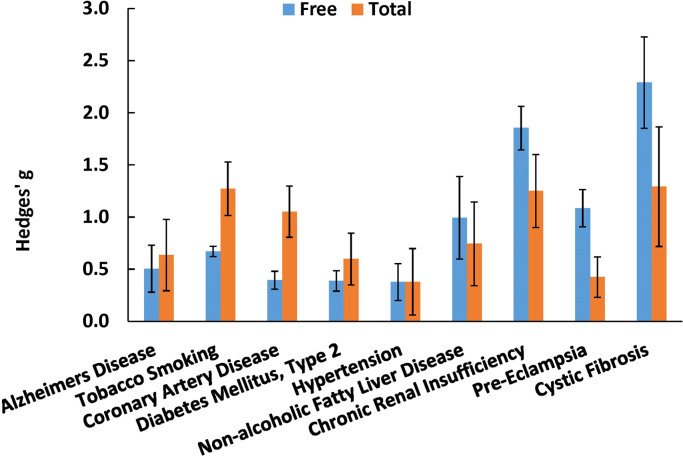

Total 8-iso-PGF2α represents an aggregate of both free 8-iso-PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α esterified to phospholipids. Esterified 8-iso-PGF2α is typically measured as free after liberation by base hydrolysis or upon treatment with a phospholipase. Total 8-iso-PGF2α in plasma is ~10 times the concentration relative to the free 8-iso-PGF2α (Fig. 5). Far fewer publications were found for total 8-iso-PGF2α. These involved 9 conditions. The meta-analysis results for total 8-iso-PGF2α are presented graphically in a Forest plot (Fig. 6). Due to the small number of conditions, it is hard to create a ranking order for categories like the one created for free 8-iso-PGF2α. However, a comparison can be made between the free and total 8-iso-PGF2α for each condition (Fig. 7). Interestingly, in some conditions total 8-iso-PGF2α showed a greater response than free 8-iso-PGF2α. These conditions included tobacco smoking (g=1.3 vs. 0.7) and coronary artery disease (g=1.1 vs. 0.3). In other conditions such as pre-eclampsia (g=1.1 vs. 0.4) and chronic kidney insufficiency (g=1.9 vs. 1.2), the free 8-iso-PGF2α showed a greater response than the total 8-iso-PGF2α.

Fig. 5.

Total 8-iso-PGF2α amounts in reported healthy individuals separated by analytical technique and specimen. Data in the graph and table show mean±standard deviation. The number in parentheses is the sum of individuals analyzed per group. The number of studies represents the unique number of publications per group.

Fig. 6.

Forest plots of all calculated standardized mean differences for total 8-iso-PGF2α subdivided by condition. The standardized mean difference is Hedges’ g. Fixed-effects model results are plotted in the blue diamonds. These are calculated for each subgroup with inverse variance weighting of individual studies. DerSimonian-Laird estimators are used for the heterogeneity calculation. The test for effect in subgroup statistically determines whether the effect size is greater than 0. The number in the affected and control groups represents the number of people tested. Data for this figure was extracted from references [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212], [213], [214], [215], [216], [217], [218], [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], [224], [225], [226], [227], [228], [229], [230], [231], [232], [233], [234], [235], [236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241], [242], [243], [244], [245], [246], [247], [248], [249], [250], [251], [252], [253], [254], [255], [256], [257], [258], [259], [260], [261], [262], [263], [264], [265]. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

Fig. 7.

Comparison between standardized mean differences for free and total 8-iso-PGF2α. Data are fixed-effect model Hedges’ g values ±95% confidence interval.

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

In the meta-analysis results presented above, all 8-iso-PGF2α results were combined and not separately analyzed based on specimen type or analytical method. There is significant controversy in the literature on the applicability of the different 8-iso-PGF2α measurements and whether different methods or specimens measure different things and should thus not be compared directly [21], [22], [23], [24]. To evaluate the influence of potential bias introduced by specimen and analytical method on the outcome of the meta-analysis (Hedges' g), a sensitivity analysis was performed. Even though there was no perfect agreement in the exact amount of 8-iso-PGF2α measured in each specimen (Figs. 2 and 5), no statistically significant differences in the standardized mean differences (Hedges’ g) between cases and control were observed in the specimen sensitivity analysis (Supplementary material Fig. 1A). This leads us to conclude that the analyzed specimens provide comparable results with no evidence for bias and, thus, the meta-analysis does not need to be stratified by specimen. Similarly, no statistically different responses in the Hedges' g are observed when different methodologies are used (Supplementay material Fig. 1B); therefore, all results regardless of method or specimen can be compared for the purposes of this meta-analysis. Publication bias was evaluated in 5 conditions (current tobacco smoking, cancer, pre-eclampsia, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) as the minimum recommended amount of independent publications is ten. This analysis found no statistically significant asymmetry in the funnel plot (p<0.05) of all conditions except asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Supplementay material Fig. 2). However, this asymmetry is highly dependent on a single publication in both conditions; therefore, to conclude publication bias is occurring would be an overstatement.

4. Discussion

Based on the results from this meta-analysis, there is a general increase in the levels of both free and total 8-iso-PGF2α associated with a variety of conditions and environmental exposures. The increases are the largest in pathologies involving the kidneys and lungs as well as in pregnant vs. non-pregnant and non-complicated pregnancy vs. pre-eclampsia. Interestingly, conditions long touted as having high levels of oxidative damage, such as tobacco smoking and cardiovascular disease, were near the bottom of the ranking resulting from this meta-analysis.

Out of the total 64 F2-isoprostane regio- and stereoisomers, this meta-analysis focuses on a single isomer (8-iso-PGF2α, also known as iPF2α.-III; 8-epi PGF2α; 8-isoprostane; or 15-F2t-isoprostane). This isomer has been used as a proxy for a change in general F2-isoprostane levels. Other isomers are occasionally measured, such as 5-iPF2α or 8,12‐iso‐iPF2α, as well as metabolites of 8-iso-PGF2α, but there are limited publications; therefore, a comprehensive meta-analysis including these isomers or analyzing them separately cannot be performed currently.

There is significant controversy in the literature on the ability to compare 8-iso-PGF2α levels measured with different methods and cleanup procedures [21], [22], [23]. It should be noted, that with proper sample cleanup, both analytical methods result in statistically indistinguishable quantities of 8-iso-PGF2α measured in aliquots from the same sample [24]. Despite not being able to account for variations in the sample cleanup procedure due to poor method description, in this meta-analysis, we found no statistically significant differences in the quantity of free and total 8-iso-PGF2α when comparing populations analyzed with different analytical methods (Fig. 2, Fig. 5). The population comparison shows that, in a large collection, measurement variability due to antibody cross-reactivity, poor sample cleanup, peak overlap, and other analytical differences does not significantly contribute to different quantities of 8-iso-PGF2α measured. Therefore, since the sample size in this analysis is so large, we can reasonably compare results across studies and conditions. More important than exact quantitative agreement is the fact that the effect size (Hedges’ g) between healthy and diseased populations is not statistically significantly changed depending on which analytical method was used (Supplementay material Fig. 1). Since each analytical method globally provides comparable results in effect size, even in the absence of exact quantitative agreement, we are justified in combining all data and need not stratify the analysis based on analytical method.

As a measure of oxidative damage, 8-iso-PGF2α has some significant potential limitations. There is an alternate enzymatic pathway to generate 8-iso-PGF2α catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase [5], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. This mechanism is independent of the non-enzymatic, free radical-mediated peroxidation of arachidonic acid, which was alleged to be the only significant mechanism for 8-iso-PGF2α formation in vivo. Therefore, even if there was an increase in 8-iso-PGF2α concentration between cases and controls or exposed and unexposed, there is no guarantee that this is due to non-enzymatic peroxidation. A method to separate the contribution of the two pathways has been described [1] and shows that under different conditions the pathway responsible for 8-iso-PGF2α generation is different [2]. The evidence for the role of an alternate generation pathway voids the conclusion that 8-iso-PGF2α by itself is a biomarker of oxidative stress. This calls into question the conclusions of previous studies with this biomarker. The meta-analysis data here can serve as a priority list for reanalysis of those conditions where the largest effect has been shown in the past and to guide future research into oxidative stress.

We can further prioritize the conditions for reanalysis by looking at the difference in effect size between total and free 8-iso-PGF2α (Fig. 7). Total 8-iso-PGF2α is a combination of 8-iso-PGF2α esterified to phospholipids and free 8-iso-PGF2α. Enzymatic generation of 8-iso-PGF2α through the inflammation-induced prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases is a confounding mechanism only for interpretation of free 8-iso-PGF2α. Total 8-iso-PGF2α is less affected by the confounding mechanism because esterified arachidonic acid is not a substrate for prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases. Therefore, measurement of only esterified 8-iso-PGF2α or total 8-iso-PGF2α, which is predominantly esterified 8-iso-PGF2α, may be a more indicative marker of oxidative stress. Thus, by looking at the different responses for total and free 8-iso-PGF2α, we can infer that in conditions with a greater response of total compared to free 8-iso-PGF2α, the generation mechanism is most likely non-enzymatic oxidative damage. In the meta-analysis, this is true for two conditions, namely tobacco smoking and coronary artery disease. In the other conditions, especially in pre-eclampsia, the free 8-iso-PGF2α gives a greater response than total, which indicates that the major source of 8-iso-PGF2α is most likely the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases.

There are some limitations to the interpretation of this meta-analysis. There are several conditions, such as overweight, Raynaud's disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, bronchiectasis, secondary smoking, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which have only two included publications describing populations with these conditions. The estimates for these conditions and others with few studies are not ideal, but hopefully, with future research, these current estimates can be confirmed. Also, certain categories, e.g., congenital diseases and infectious diseases, are comprised of only a single disease in this meta-analysis. This severely limits the broad interpretation of these categories until more conditions are included.

We present here a ranking of the conditions in which there is the most potential for lipid peroxidation to play a major role in the etiology or pathology of human diseases and exposure to environmental pollutants. The exact mechanism must now be evaluated using approaches such as the 8-iso-PGF2α/PGF2α ratio [1], [2] to evaluate the involvement of inflammation and, thus, make the best possible conclusions for future clinical study and the development of cures for those conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Shyamal Peddada for his valuable feedback on the statistics; Drs. Kelly K. Ferguson and Ashutosh Kumar for their review of this manuscript; and Jean Corbett, Dr. Ann Motten, and Mary Mason for their editorial expertise. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01 ES048012-08).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.024.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.van't Erve T.J., Lih F.B., Kadiiska M.B., Deterding L.J., Eling T.E., Mason R.P. Reinterpreting the best biomarker of oxidative stress: the 8-iso-PGF2α/PGF2α ratio distinguishes chemical from enzymatic lipid peroxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;83:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van't Erve T.J., Lih F.B., Jelsema C., Deterding L.J., Eling T.E., Mason R.P., Kadiiska M.B. Reinterpreting the best biomarker of oxidative stress: the 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a/prostaglandin F2a ratio shows complex origins of lipid peroxidation biomarkers in animal models. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;95:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadiiska M.B., Gladen B.C., Baird D.D., Dikalova A.E., Sohal R.S., Hatch G.E., Jones D.P., Mason R.P., Barrett J.C. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study: are plasma antioxidants markers of CCl(4) poisoning? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:838–845. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadiiska M.B., Gladen B.C., Baird D.D., Germolec D., Graham L.B., Parker C.E., Nyska A., Wachsman J.T., Ames B.N., Basu S., Brot N., Fitzgerald G.A., Floyd R.A., George M., Heinecke J.W., Hatch G.E., Hensley K., Lawson J.A., Marnett L.J., Morrow J.D., Murray D.M., Plastaras J., Roberts L.J., II, Rokach J., Shigenaga M.K., Sohal R.S., Sun J., Tice R.R., Van Thiel D.H., Wellner D., Walter P.B., Tomer K.B., Mason R.P., Barrett J.C. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study II. Are oxidation products of lipids, proteins, and DNA markers of CCl4 poisoning? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;38:698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadiiska M.B., Gladen B.C., Baird D.D., Graham L.B., Parker C.E., Ames B.N., Basu S., Fitzgerald G.A., Lawson J.A., Marnett L.J., Morrow J.D., Murray D.M., Plastaras J., Roberts L.J., II, Rokach J., Shigenaga M.K., Sun J., Walter P.B., Tomer K.B., Barrett J.C., Mason R.P. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study III. Effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents indomethacin and meclofenamic acid on measurements of oxidative products of lipids in CCl4 poisoning. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;38:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadiiska M.B., Hatch G.E., Nyska A., Jones D.P., Hensley K., Stocker R., George M.M., Van Thiel D.H., Stadler K., Barrett J.C., Mason R.P. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study IV: ozone exposure of rats and its effect on antioxidants in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;51:1636–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadiiska M.B., Basu S., Brot N., Cooper C., Saari Csallany A., Davies M.J., George M.M., Murray D.M., Roberts L.J., II, Shigenaga M.K., Sohal R.S., Stocker R., Van Thiel D.H., Wiswedel I., Hatch G.E., Mason R.P. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study V: ozone exposure of rats and its effect on lipids, proteins, and DNA in plasma and urine. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;61C:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow J.D., Hill K.E., Burk R.F., Nammour T.M., Badr K.F., Roberts L.J., II A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milne G.L., Musiek E.S., Morrow J.D. F2-Isoprostanes as markers of oxidative stress in vivo: an overview. Biomarkers. 2005;10:10–23. doi: 10.1080/13547500500216546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.M. Borenstein, L.V. Hedges, J.P.T. Higgins, H.R. Rothstein, How a meta-analysis works, Introduction to Meta-Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009, pp. 1–7.

- 11.Praticò D., Barry O.P., Lawson J.A., Adiyaman M., Hwang S.W., Khanapure S.P., Iuliano L., Rokach J., FitzGerald G.A. IPF2α-I: an index of lipid peroxidation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3449–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedges L.V. Distribution theory for glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1981;6:107–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Borenstein, L.V. Hedges, J.P.T. Higgins, H.R. Rothstein, Effect sizes based on means, Introduction to Meta-Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009, pp. 21–32.

- 14.M. Borenstein, L.V. Hedges, J.P.T. Higgins, H.R. Rothstein, Multiple comparisons within a study, Introduction to Meta-Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009, pp. 239–242.

- 15.M. Borenstein, L.V. Hedges, J.P.T. Higgins, H.R. Rothstein, Fixed-effect model, Introduction to Meta-Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009, pp. 63–67.

- 16.M. Borenstein, L.V. Hedges, J.P.T. Higgins, H.R. Rothstein, Subgroup analyses, Introduction to Meta-Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2009, pp. 149–186.

- 17.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.J.B. Greenhouse, S. Iyengar, Sensitivity analysis and diagnostics, The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, Russell Sage Foundation, 2009, pp. 417–434.

- 19.Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proudfoot J., Barden A., Mori T.A., Burke V., Croft K.D., Beilin L.J., Puddey I.B. Measurement of urinary F(2)-isoprostanes as markers of in vivo lipid peroxidation-A comparison of enzyme immunoassay with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 1999;272:209–215. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessard J., Cracowski J.L., Stanke-Labesque F., Bessard G. Determination of isoprostaglandin F2alpha type III in human urine by gas chromatography-electronic impact mass spectrometry. Comparison with enzyme immunoassay. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2001;754:333–343. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsikas D., Schwedhelm E., Suchy M.T., Niemann J., Gutzki F.M., Erpenbeck V.J., Hohlfeld J.M., Surdacki A., Frolich J.C. Divergence in urinary 8-iso-PGF(2alpha) (iPF(2alpha)-III, 15-F(2t)-IsoP) levels from gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry quantification after thin-layer chromatography and immunoaffinity column chromatography reveals heterogeneity of 8-iso-PGF(2alpha). Possible methodological, mechanistic and clinical implications. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2003;794:237–255. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahl J.H., van Breemen R.B. Rapid quantitative analysis of 8-iso-prostaglandin-F(2alpha) using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and comparison with an enzyme immunoassay method. Anal. Biochem. 2010;404:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Praticò D., Lawson J.A., FitzGerald G.A. Cyclooxygenase-dependent formation of the isoprostane, 8-epiprostaglandin F2α. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9800–9808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Praticò D., FitzGerald G.A. Generation of 8-epiprostaglandin F2α by human monocytes: discriminate production by reactive oxygen species and prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8919–8924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein T., Reutter F., Schweer H., Seyberth H.W., Nüsing R.M. Generation of the isoprostane 8-epi-prostaglandin F2αin vitro and in vivo via the cyclooxygenases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;282:1658–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachi A., Brambilla R., Fanelli R., Bianchi R., Zuccato E., Chiabrando C. Reduction of urinary 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α during cyclooxygenase inhibition in rats but not in man. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1770–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweer H., Watzer B., Seyberth H.W., Nusing R.M. Improved quantification of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α and F2-isoprostanes by gas chromatography/triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry: partial cyclooxygenase-dependent formation of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α in humans. J. Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:1362–1370. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199712)32:12<1362::AID-JMS606>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watkins M.T., Patton G.M., Soler H.M., Albadawi H., Humphries D.E., Evans J.E., Kadowaki H. Synthesis of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α by human endothelial cells: role of prostaglandin H2 synthase. Biochem. J. 1999;344:747–754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Favreau F., Petit-Paris I., Hauet T., Dutheil D., Papet Y., Mauco G., Tallineau C. Cyclooxygenase 1-dependent production of F2-isoprostane and changes in redox status during warm renal ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmadzadehfar H., Oguogho A., Efthimiou Y., Kritz H., Sinzinger H. Passive cigarette smoking increases isoprostane formation. Life Sci. 2006;78:894–897. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Alem U., Gann P.H., Dahl J., van Breemen R.B., Mistry V., Lam P.M., Evans M.D., Van Horn L., Wright M.E. Associations between functional polymorphisms in antioxidant defense genes and urinary oxidative stress biomarkers in healthy, premenopausal women. Genes Nutr. 2012;7:191–195. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez R.F., Cuadrado G.R., Arias R.A., Hernandez J.A.C., Antequera B.P., Urrutia M.I., Clara P.C. Snoring as a determinant factor of oxidative stress in the airway of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Lung. 2016;194:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angelico F., Loffredo L., Pignatelli P., Augelletti T., Carnevale R., Pacella A., Albanese F., Mancini I., Di Santo S., Ben M.D., Violi F. Weight loss is associated with improved endothelial dysfunction via NOX2-generated oxidative stress down-regulation in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2012;7:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antczak A., Montuschi P., Kharitonov S., Gorski P., Barnes P.J. Increased exhaled cysteinyl-leukotrienes and 8-isoprostane in aspirin-induced asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2002;166:301–306. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antczak A., Kharitonov S.A., Montuschi P., Gorski P., Barnes P.J. Inflammatory response to sputum induction measured by exhaled markers. Respiration. 2005;72:594–599. doi: 10.1159/000086721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antczak A., Piotrowski W., Marczak J., Ciebiada M., Gorski P., Barnes P.J. Correlation between eicosanoids in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and in exhaled breath condensate. Dis. Markers. 2011;30:213–220. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antczak A., Ciebiada M., Pietras T., Piotrowski W.J., Kurmanowska Z., Gorski P. Exhaled eicosanoids and biomarkers of oxidative stress in exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch. Med. Sci. 2012;8:277–285. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonopoulou S., Loukides S., Papatheodorou G., Roussos C., Alchanatis M. Airway inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea: is leptin the missing link? Respir. Med. 2008;102:1399–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araki S., Dobashi K., Yamamoto Y., Asayama K., Kusuhara K. Increased plasma isoprostane is associated with visceral fat, high molecular weight adiponectin, and metabolic complications in obese children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010;169:965–970. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1157-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avalos I., Chung C.P., Oeser A., Milne G.L., Morrow J.D., Gebretsadik T., Shintani A., Yu C., Stein C.M. Oxidative stress in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship to disease activity and symptoms. Lupus. 2007;16:195–200. doi: 10.1177/0961203306075802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Avouac J., Borderie D., Ekindjian O.G., Kahan A., Allanore Y. High DNA oxidative damage in systemic sclerosis. J. Rheumatol. 2010;37:2540–2547. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bachi A., Zuccato E., Baraldi M., Fanelli R., Chiabrando C. Measurement of urinary 8-epi-prostaglandin F-2 alpha, a novel index of lipid peroxidation in vivo, by immunoaffinity extraction gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Basal levels in smokers and nonsmokers. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;20:619–624. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balanza S.C., Aragones A.M., Mir J.C.C., Ramirez J.B., Ivanez R.N., Soriano A.N., Toledo R.F., Montaner A.E. Leukotriene B-4 and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of children with episodic and persistent asthma. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2010;20:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baraldi E., Ghiro L., Piovan V., Carraro S., Ciabattoni G., Barnes P.J., Montuschi P. Increased exhaled 8-isoprostane in childhood asthma. Chest. 2003;124:25–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baraldi E., Carraro S., Alinovi R., Pesci A., Ghiro L., Bodini A., Piacentini G., Zacchello F., Zanconato S. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma exacerbations. Thorax. 2003;58:505–509. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barden A., Beilin L.J., Ritchie J., Croft K.D., Walters B.N., Michael C.A. Plasma and urinary 8-isoprostane as an indicator of lipid peroxidation in pre-eclampsia and normal pregnancy. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1996;91:711–718. doi: 10.1042/cs0910711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barocas D.A., Motley S., Cookson M.S., Chang S.S., Penson D.F., Dai Q., Milne G., Roberts L.J., 2nd, Morrow J., Concepcion R.S., Smith J.A., Jr., Fowke J.H. Oxidative stress measured by urine F2-isoprostane level is associated with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2011;185:2102–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basarici I., Altekin R.E., Demir I., Yilmaz H. Associations of isoprostanes-related oxidative stress with surrogate subclinical indices and angiographic measures of atherosclerosis. Coron. Artery Dis. 2007;18:615–620. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3282f0efa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basili S., Raparelli V., Riggio O., Merli M., Carnevale R., Angelico F., Tellan G., Pignatelli P., Violi F., Calc Group NADPH oxidase-mediated platelet isoprostane over-production in cirrhotic patients: implication for platelet activation. Liver Int. 2011;31:1533–1540. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basu S., Helmersson J., Jarosinska D., Sallsten G., Mazzolai B., Barregard L. Regulatory factors of basal F(2)-isoprostane formation: population, age, gender and smoking habits in humans. Free Radic. Res. 2009;43:85–91. doi: 10.1080/10715760802610851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Battaglia S., den Hertog H., Timmers M.C., Lazeroms S.P., Vignola A.M., Rabe K.F., Bellia V., Hiemstra P.S., Sterk P.J. Small airways function and molecular markers in exhaled air in mild asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:639–644. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.035279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biernacki W.A., Kharitonov S.A., Barnes P.J. Increased leukotriene B4 and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of patients with exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:294–298. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bilodeau J.F., Wei S.Q., Larose J., Greffard K., Moisan V., Audibert F., Fraser W.D., Julien P. Plasma F-2-isoprostane class VI isomers at 12-18 weeks of pregnancy are associated with later occurrence of preeclampsia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;85:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biltagi M.A., Maguid M.A., Ghafar M.A., Farid E. Correlation of 8-isoprostane, interleukin-6 and cardiac functions with clinical score in childhood obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1397–1405. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black C.N., Penninx B., Bot M., Odegaard A.O., Gross M.D., Matthews K.A., Jacobs D.R. Oxidative stress, anti-oxidants and the cross-sectional and longitudinal association with depressive symptoms: results from the CARDIA study. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Block G., Dietrich M., Norkus E.P., Morrow J.D., Hudes M., Caan B., Packer L. Factors associated with oxidative stress in human populations. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002;156:274–285. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bloomer R.J., Fisher-Wellman K.H., Bell H.K. The effect of long-term, high-volume aerobic exercise training on postprandial lipemia and oxidative stress. Phys. Sportsmed. 2010;38:64–71. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.04.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bohnstedt K.C., Karlberg B., Wahlund L.O., Jonhagen M.E., Basun H., Schmidt S. Determination of isoprostanes in urine samples from Alzheimer patients using porous graphitic carbon liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B-Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2003;796:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borrill Z.L., Roy K., Vessey R.S., Woodcock A.A., Singh D. Non-invasive biomarkers and pulmonary function in smokers. Int. J. Chron. Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2008;3:171–183. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braekke K., Harsem N.K., Staff A.C. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in fetal circulation in preeclampsia. Pediatr. Res. 2006;60:560–564. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000242299.01219.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brantley M.A., Jr, Osborn M.P., Sanders B.J., Rezaei K.A., Lu P., Li C., Milne G.L., Cai J., Sternberg P., Jr. Plasma biomarkers of oxidative stress and genetic variants in age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;153(460–467):e461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brys M., Morel A., Forma E., Krzeslak A., Wilkosz J., Rozanski W., Olas B. Relationship of urinary isoprostanes to prostate cancer occurrence. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013;372:149–153. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1455-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campos C., Guzman R., Lopez-Fernandez E., Casado A. Evaluation of urinary biomarkers of oxidative/nitrosative stress in children with down syndrome. Life Sci. 2011;89:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campos C., Guzman R., Lopez-Fernandez E., Casado A. Evaluation of urinary biomarkers of oxidative/nitrosative stress in adolescents and adults with down syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campos C., Guzman R., Lopez-Fernandez E., Casado A. Urinary biomarkers of oxidative/nitrosative stress in healthy smokers. Inhal. Toxicol. 2011;23:148–156. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.554460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carpagnano G.E., Kharitonov S.A., Resta O., Foschino-Barbaro M.P., Gramiccioni E., Barnes P.J. Increased 8-isoprostane and interleukin-6 in breath condensate of obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 2002;122:1162–1167. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carpagnano G.E., Kharitonov S.A., Resta O., Foschino-Barbaro M.P., Gramiccioni E., Barnes P.J. 8-Isoprostane, a marker of oxidative stress, is increased in exhaled breath condensate of patients with obstructive sleep apnea after night and is reduced by continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2003;124:1386–1392. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carpagnano G.E., Resta O., Foschino-Barbaro M.P., Spanevello A., Stefano A., Di Gioia G., Serviddio G., Gramiccioni E. Exhaled Interleukine-6 and 8-isoprostane in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect of carbocysteine lysine salt monohydrate (SCMC-Lys) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;505:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carpagnano G.E., Resta O., Ventura M.T., Amoruso A.C., Di Gioia G., Giliberti T., Refolo L., Foschino-Barbario M.P. Airway inflammation in subjects with gastro-oesophageal reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux-related asthma. J. Intern. Med. 2006;259:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Caruso R., Verde A., Campolo J., Milazzo F., Russo C., Boroni C., Parolini M., Trunfio S., Paino R., Martinelli L., Frigerio M., Parodi O. Severity of oxidative stress and inflammatory activation in end-stage heart failure patients are unaltered after 1 month of left ventricular mechanical assistance. Cytokine. 2012;59:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan H.P., Tran V., Lewis C., Thomas P.S. Elevated levels of oxidative stress markers in exhaled breath condensate. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009;4:172–178. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181949eb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chao P.C., Huang C.N., Hsu C.C., Yin M.C., Guo Y.R. Association of dietary AGEs with circulating AGEs, glycated LDL, IL-1 alpha and MCP-1 levels in type 2 diabetic patients. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010;49:429–434. doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chehne F., Oguogho A., Lupattelli G., Budinsky A.C., Palumbo B., Sinzinger H. Increase of isoprostane 8-epi-PGF(2 alpha) after restarting smoking. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 2001;64:307–310. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen S.P., Chung Y.T., Liu T.Y., Wang Y.F., Fuh J.L., Wang S.J. Oxidative stress and increased formation of vasoconstricting F2-isoprostanes in patients with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;61:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cheng Q., Wang J., Wu A., Zhang R., Li L., Yue Y. Can urinary excretion rate of 8-isoprostrane and malonaldehyde predict postoperative cognitive dysfunction in aging? Neurol. Sci. 2013;34:1665–1669. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cherneva R.V., Georgiev O.B., Petrova D.S., Mondeshki T.L., Ruseva S.R., Cakova A.D., Mitev V.I. Resistin – the link between adipose tissue dysfunction and insulin resistance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2013;12:5. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho J.H., Suh J.D., Kim Y.W., Hong S.C., Kim I.T., Kim J.K. Reduction in oxidative stress biomarkers after adenotonsillectomy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:1408–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chow S., Campbell C., Sandrini A., Thomas P.S., Johnson A.R., Yates D.H. Exhaled breath condensate biomarkers in asbestos-related lung disorders. Respir. Med. 2009;103:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chow S., Thomas P.S., Malouf M., Yates D.H. Exhaled breath condensate (EBC) biomarkers in pulmonary fibrosis. J. Breath Res. 2012;6 doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/1/016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ciabattoni G., Davi G., Collura M., Iapichino L., Pardo F., Ganci A., Romagnoli R., Maclouf J., Patrono C. In vivo lipid peroxidation and platelet activation in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:1195–1201. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9911071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ciebiada M., Gorski P., Antczak A. Eicosanoids in exhaled breath condensate and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with primary lung cancer. Dis. Markers. 2012;32:329–335. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Codoner-Franch P., Tavarez-Alonso S., Murria-Estal R., Megias-Vericat J., Tortajada-Girbes M., Alonso-Iglesias E. Nitric oxide production is increased in severely obese children and related to markers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Collins C.E., Quaggiotto P., Wood L., O'Loughlin E.V., Henry R.L., Garg M.L. Elevated plasma levels of F2a isoprostane in cystic fibrosis. Lipids. 1999;34:551–556. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0397-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Comporti M., Signorini C., Leoncini S., Buonocore G., Rossi V., Ciccoli L. Plasma F2-isoprostanes are elevated in newborns and inversely correlated to gestational age. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Corcoran T.B., Mas E., Barden A.E., Durand T., Galano J.M., Roberts L.J., Phillips M., Ho K.M., Mori T.A. Are isofurans and neuroprostanes increased after subarachnoid hemorrhage and traumatic brain injury? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;15:2663–2667. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cottone S., Mule G., Guarneri M., Palermo A., Lorito M.C., Riccobene R., Arsena R., Vaccaro F., Vadala A., Nardi E., Cusimano P., Cerasola G. Endothelin-1 and F2-isoprostane relate to and predict renal dysfunction in hypertensive patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24:497–503. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cracowski J.L., Cracowski C., Bessard G., Pepin J.L., Bessard J., Schwebel C., Stanke-Labesque F., Pison C. Increased lipid peroxidation in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001;164:1038–1042. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2104033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cracowski J.L., Bonaz B., Bessard G., Bessard J., Anglade C., Fournet J. Increased urinary F2-isoprostanes in patients with Crohn's disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:99–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cracowski J.L., Baguet J.P., Ormezzano O., Bessard J., Stanke-Labesque F., Bessard G., Mallion J.M. Lipid peroxidation is not increased in patients with untreated mild-to-moderate hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:286–288. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050963.16405.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cracowski J.L., Kom G.D., Salvat-Melis M., Renversez J.C., McCord G., Boignard A., Carpentier P.H., Schwedhelm E. Postocclusive reactive hyperemia inversely correlates with urinary 15-F-2t-isoprostane levels in systemic sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:1732–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dai Q., Gao Y.T., Shu X.O., Yang G., Milne G., Cai Q.Y., Wen W.Q., Rothman N., Cai H., Li H.L., Xiang Y.B., Chow W.H., Zheng W. Oxidative stress, obesity, and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai women's health study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:2482–2488. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dalaveris E., Kerenidi T., Katsabeki-Katsafli A., Kiropoulos T., Tanou K., Gourgoulianis K.I., Kostikas K. VEGF, TNF-alpha and 8-isoprostane levels in exhaled breath condensate and serum of patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Davi G., Alessandrini P., Mezzetti A., Minotti G., Bucciarelli T., Costantini F., Cipollone F., Bon G.B., Ciabattoni G., Patrono C. In vivo formation of 8-Epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha is increased in hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:3230–3235. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Davi G., Ciabattoni G., Consoli A., Mezzetti A., Falco A., Santarone S., Pennese E., Vitacolonna E., Bucciarelli T., Costantini F., Capani F., Patrono C. In vivo formation of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a and platelet activation in diabetes mellitus: effects of improved metabolic control and vitamin E supplementation. Circulation. 1999;99:224–229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Davi G., Guagnano M.T., Ciabattoni G., Basili S., Falco A., Marinopiccoli M., Nutini M., Sensi S., Patrono C. Platelet activation in obese women: role of inflammation and oxidant stress. JAMA. 2002;288:2008–2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davi G., Chiarelli F., Santilli F., Pomilio M., Vigneri S., Falco A., Basili S., Ciabattoni G., Patrono C. Enhanced lipid peroxidation and platelet activation in the early phase of type 1 diabetes mellitus – role of interleukin-6 and disease duration. Circulation. 2003;107:3199–3203. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074205.17807.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De Felice C., Ciccoli L., Leoncini S., Signorini C., Rossi M., Vannuccini L., Guazzi G., Latini G., Comporti M., Valacchi G., Hayek J. Systemic oxidative stress in classic Rett syndrome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.De Felice C., Maffei S., Signorini C., Leoncini S., Lunghetti S., Valacchi G., D'Esposito M., Filosa S., Ragione F.D., Butera G., Favilli R., Ciccoli L., Hayek J. Subclinical myocardial dysfunction in Rett syndrome. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2012;13:339–345. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Felice C., Signorini C., Durand T., Ciccoli L., Leoncini S., D'Esposito M., Filosa S., Oger C., Guy A., Bultel-Ponce V., Galano J.M., Pecorelli A., De Felice L., Valacchi G., Hayek J. Partial rescue of Rett syndrome by w-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) oil. Genes Nutr. 2012;7:447–458. doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Devries M.C., Hamadeh M.J., Glover A.W., Raha S., Samjoo I.A., Tarnopolsky M.A. Endurance training without weight loss lowers systemic, but not muscle, oxidative stress with no effect on inflammation in lean and obese women. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dhamrait S.S., Stephens J.W., Cooper J.A., Acharya J., Mani A.R., Moore K., Miller G.J., Humphries S.E., Hurel S.J., Montgomery H.E. Cardiovascular risk in healthy men and markers of oxidative stress in diabetic men are associated with common variation in the gene for uncoupling protein 2. Eur. Heart J. 2004;25:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Diaz-Castro J., Guisado R., Kajarabille N., Garcia C., Guisado I.M., De Teresa C., Ochoa J.J. Phlebodium decumanum is a natural supplement that ameliorates the oxidative stress and inflammatory signalling induced by strenuous exercise in adult humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012;112:3119–3128. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dimopoulos N., Piperi C., Psarra V., Lea R.W., Kalofoutis A. Increased plasma levels of 8-iso-PGF(2 alpha) and IL-6 in an elderly population with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dolegowska B., Stepniewska J., Ciechanowski K., Safranow K., Millo B., Bober J., Chlubek D. Does glucose in dialysis fluid protect erythrocytes in patients with chronic renal failure? Blood Purif. 2007;25:422–429. doi: 10.1159/000109817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Durazzo T.C., Mattsson N., Weiner M.W., Korecka M., Trojanowski J.Q., Shaw L.M. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging, I. History of cigarette smoking in cognitively-normal elders is associated with elevated cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of oxidative stress. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.El-Ansary A., Al-Ayadhi L. Lipid mediators in plasma of autism spectrum disorders. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:160. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Elango N., Kasi V., Vembhu B., Poornima J.G. Chronic exposure to emissions from photocopiers in copy shops causes oxidative stress and systematic inflammation among photocopier operators in India. Environ. Health. 2013;12 doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.El-Ansary A., Hassan W.M., Qasem H., Das U.N. Identification of biomarkers of impaired sensory profiles among autistic patients. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ercan H., Kiyici A., Marakoglu K., Oncel M. 8-Isoprostane and coenzyme Q10 levels in patients with metabolic syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2016;14:318–321. doi: 10.1089/met.2016.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Faridvand Y., Oskuyi A.E., Khadem-Ansari M.H. Serum 8-isoprostane levels and paraoxonase 1 activity in patients with stage I multiple myeloma. Redox Rep. 2016;21:204–208. doi: 10.1179/1351000215Y.0000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Feillet-Coudray C., Chone F., Michel F., Rock E., Thieblot P., Rayssiguier Y., Tauveron I., Mazur A. Divergence in plasmatic and urinary isoprostane levels in type 2 diabetes. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;324:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ferguson K.K., McElrath T.F., Chen Y.H., Loch-Caruso R., Mukherjee B., Meeker J.D. Repeated measures of urinary oxidative stress biomarkers during pregnancy and preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212(208):e201–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ferguson K.K., Meeker J.D., McElrath T.F., Mukherjee B., Cantonwine D.E. Repeated measures of inflammation and oxidative stress biomarkers in preeclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ferro D., Basili S., Pratico D., Iuliano L., FitzGerald G.A., Violi F. Vitamin E reduces monocyte tissue factor expression in cirrhotic patients. Blood. 1999;93:2945–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Filippone M., Bonetto G., Corradi M., Frigo A.C., Baraldi E. Evidence of unexpected oxidative stress in airways of adolescents born very pre-term. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;40:1253–1259. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Friel J.K., Diehl-Jones B., Cockell K.A., Chiu A., Rabanni R., Davies S.S., Roberts L.J., 2nd Evidence of oxidative stress in relation to feeding type during early life in premature infants. Pediatr. Res. 2011;69:160–164. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182042a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fritscher L.G., Post M., Rodrigues M.T., Silverman F., Balter M., Chapman K.R., Zamel N. Profile of eicosanoids in breath condensate in asthma and COPD. J. Breath Res. 2012;6 doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/2/026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Frost-Pineda K., Liang Q., Liu J., Rimmer L., Jin Y., Feng S., Kapur S., Mendes P., Roethig H., Sarkar M. Biomarkers of potential harm among adult smokers and nonsmokers in the total exposure study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13:182–193. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ghezzo A., Visconti P., Abruzzo P.M., Bolotta A., Ferreri C., Gobbi G., Malisardi G., Manfredini S., Marini M., Nanetti L., Pipitone E., Raffaelli F., Resca F., Vignini A., Mazzanti L. Oxidative stress and erythrocyte membrane alterations in children with autism: correlation with clinical features. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Giannini C., de Giorgis T., Scarinci A., Cataldo I., Marcovecchio M.L., Chiarelli F., Mohn A. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in pre-pubertal children with constitutional leanness and severe obesity: the speculative role of insulin sensitivity, oxidant status, and chronic inflammation. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009;161:73–80. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gopaul N.K., Anggard E.E., Mallet A.I., Betteridge D.J., Wolff S.P., Nourooz-Zadeh J. Plasma 8-epi-PGF2a levels are elevated in individuals with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00649-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grass D.S., Ross J.M., Family F., Barbour J., Simpson H.J., Coulibaly D., Hernandez J., Chen Y., Slavkovich V., Li Y., Graziano J., Santella R.M., Brandt-Rauf P., Chillrud S.N. Airborne particulate metals in the New York City subway: a pilot study to assess the potential for health impacts. Environ. Res. 2010;110:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Greco A., Minghetti L., Puopolo M., Pietrobon B., Franzoi M., Chiandetti L., Suppiej A. Plasma levels of 15-F(2t)-isoprostane in newborn infants are affected by mode of delivery. Clin. Biochem. 2007;40:1420–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Grindel A., Guggenberger B., Eichberger L., Poppelmeyer C., Gschaider M., Tosevska A., Mare G., Briskey D., Brath H., Wagner K.H. Oxidative stress, DNA damage and DNA repair in female patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Handelman G.J., Walter M.F., Adhikarla R., Gross J., Dallal G.E., Levin N.W., Blumberg J.B. Elevated plasma F2-isoprostanes in patients on long-term hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1960–1966. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Harsem N.K., Braekke K., Staff A.C. Augmented oxidative stress as well as antioxidant capacity in maternal circulation in preeclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2006;128:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Harsem N.K., Braekke K., Torjussen T., Hanssen K., Staff A.C. Advanced glycation end products in pregnancies complicated with diabetes mellitus or preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy. 2008;27:374–386. doi: 10.1080/10641950802000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hasan R.A., Thomas J., Davidson B., Barnes J., Reddy R. 8-Isoprostane in the exhaled breath condensate of children hospitalized for status asthmaticus. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2011;12:E25–E28. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181dbeac6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hasan R.A., O'Brien E., Mancuso P. Lipoxin A(4) and 8-isoprostane in the exhaled breath condensate of children hospitalized for status asthmaticus. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012;13:141–145. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182231644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Haukeland J.W., Damas J.K., Konopski Z., Loberg E.M., Haaland T., Goverud I., Torjesen P.A., Birkeland K., Bjoro K., Aukrust P. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J. Hepatol. 2006;44:1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Heilman K., Zilmer M., Zilmer K., Tillmann V. Lower bone mineral density in children with type 1 diabetes is associated with poor glycemic control and higher serum ICAM-1 and urinary isoprostane levels. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2009;27:598–604. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Helmersson J., Mattsson P., Basu S. Prostaglandin F-2 alpha metabolite and F-2-isoprostane excretion rates in migraine. Clin. Sci. 2002;102:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Helmersson J., Larsson A., Vessby B., Basu S. Active smoking and a history of smoking are associated with enhanced prostaglandin F2a,, interleukin-6 and F2-isoprostane formation in elderly men. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hill D.B., Awad J.A. Increased urinary F-2-isoprostane excretion in alcoholic liver disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:656–660. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hirsch S., Ronco A.M., Vasquez M., de la Maza M.P., Garrido A., Barrera G., Gattas V., Glasinovic A., Leiva L., Bunout D. Hyperhomocysteinemia in healthy young men and elderly men with normal serum folate concentration is not associated with poor vascular reactivity or oxidative stress. J. Nutr. 2004;134:1832–1835. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hoffmeyer F., Harth V., Bunger J., Bruning T., Raulf-Heimsoth M. Leukotriene B4, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a, and pH in exhaled breath condensate from asymptomatic smokers. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 5):S57–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Horbal S.R., Seffens W., Davis A.R., Silvestrov N., Gibbons G.H., Quarells R.C., Bidulescu A. Associations of apelin, visfatin, and urinary 8-isoprostane with severe hypertension in African Americans: the MH-GRID study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016;29:814–820. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hozawa A., Ebihara S., Ohmori K., Kuriyama S., Ugajin T., Koizumi Y., Suzuki Y., Matsui T., Arai H., Tsubono Y., Sasaki H., Tsuji I. Increased plasma 8-isoprostane levels in hypertensive subjects: the Tsurugaya Project. Hypertens. Res. 2004;27:557–561. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hsieh T.T., Chen S.F., Lo L.M., Li M.J., Yeh Y.L., Hung T.H. The association between maternal oxidative stress at mid-gestation and subsequent pregnancy complications. Reprod. Sci. 2012;19:505–512. doi: 10.1177/1933719111426601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Huang C.J., Webb H.E., Evans R.K., McCleod K.A., Tangsilsat S.E., Kamimori G.H., Acevedo E.O. Psychological stress during exercise: immunoendocrine and oxidative responses. Exp. Biol. Med. 2010;235:1498–1504. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huang Y., Lemberg D.A., Day A.S., Dixon B., Leach S., Bujanover Y., Jaffe A., Thomas P.S. Markers of inflammation in the breath in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014;59:505–510. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hughes C.M., Woodside J.V., McGartland C., Roberts M.J., Nicholls D.P., McKeown P.P. Nutritional intake and oxidative stress in chronic heart failure. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012;22:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ilhan N., Celik E., Kumbak B. Maternal plasma levels of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, vitamins C, E and A, 8-isoprostane and oxidative status in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:316–319. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.916674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Inonu H., Doruk S., Sahin S., Erkorkmaz U., Celik D., Celikel S., Seyfikli Z. Oxidative stress levels in exhaled breath condensate associated with COPD and smoking. Respir. Care. 2012;57:413–419. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Irizarry M.C., Yao Y., Hyman B.T., Growdon J.H., Pratico D. Plasma F2A isoprostane levels in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 2007;4:403–405. doi: 10.1159/000107699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ishihara O., Hayashi M., Osawa H., Kobayashi K., Takeda S., Vessby B., Basu S. Isoprostanes, prostaglandins and tocopherols in pre-eclampsia, normal pregnancy and non-pregnancy. Free Radic. Res. 2004;38:913–918. doi: 10.1080/10715760412331273421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Iwanaga S., Sakano N., Taketa K., Takahashi N., Wang D.H., Takahashi H., Kubo M., Miyatake N., Ogino K. Comparison of serum ferritin and oxidative stress biomarkers between Japanese workers with and without metabolic syndrome. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014;8:e201–e298. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jacob R.A., Aiello G.M., Stephensen C.B., Blumberg J.B., Milbury P.E., Wallock L.M., Ames B.N. Moderate antioxidant supplementation has no effect on biomarkers of oxidant damage in healthy men with low fruit and vegetable intakes. J. Nutr. 2003;133:740–743. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Jain S.K., Pemberton P.W., Smith A., McMahon R.F.T., Burrows P.C., Aboutwerat A., Warnes T.W. Oxidative stress in chronic hepatitis C: not just a feature of late stage disease. J. Hepatol. 2002;36:805–811. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jeanes Y.M., Hall W.L., Proteggente A.R., Lodge J.K. Cigarette smokers have decreased lymphocyte and platelet a-tocopherol levels and increased excretion of the g-tocopherol metabolite g-carboxyethyl-hydroxychroman (g-CEHC) Free Radic. Res. 2004;38:861–868. doi: 10.1080/10715760410001715149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Jonasson T., Ohlin A.K., Gottsater A., Hultberg B., Ohlin H. Plasma homocysteine and markers for oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease--a prospective randomized study of vitamin supplementation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005;43:628–634. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kaffe E.T., Rigopoulou E.I., Koukoulis G.K., Dalekos G.N., Moulas A.N. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in patients with autoimmune liver diseases. Redox Rep. 2015;20:33–41. doi: 10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Karamouzis I., Sarafidis P.A., Karamouzis M., Iliadis S., Haidich A.B., Sioulis A., Triantos A., Vavatsi-Christaki N., Grekas D.M. Increase in oxidative stress but not in antioxidant capacity with advancing stages of chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2008;28:397–404. doi: 10.1159/000112413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Karamouzis I., Pervanidou P., Berardelli R., Iliadis S., Papassotiriou I., Karamouzis M., Chrousos G.P., Kanaka-Gantenbein C. Enhanced oxidative stress and platelet activation combined with reduced antioxidant capacity in obese prepubertal and adolescent girls with full or partial metabolic syndrome. Horm. Metab. Res. 2011;43:607–613. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kato I., Chen G., Djuric Z. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use and levels of a lipid oxidation marker in plasma and nipple aspirate fluids. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006;97:145–148. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kaviarasan S., Muniandy S., Qvist R., Chinna K., Ismail I.S. Is F-2-isoprostane a biological marker for the early onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus? Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2010;30:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kazmierczak M., Ciebiada M., Pekala-Wojciechowska A., Pawlowski M., Nielepkowicz-Gozdzinska A., Antczak A. Evaluation of markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in COPD patients with or without cardiovascular comorbidities. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24:817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Keaney J.F., Jr, Larson M.G., Vasan R.S., Wilson P.W., Lipinska I., Corey D., Massaro J.M., Sutherland P., Vita J.A., Benjamin E.J. Framingham study. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Kelly A.S., Steinberger J., Kaiser D.R., Olson T.P., Bank A.J., Dengel D.R. Oxidative stress and adverse adipokine profile characterize the metabolic syndrome in children. J. Cardiometab. Syndr. 2006;1:248–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2006.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Kelly P.J., Morrow J.D., Ning M., Koroshetz W., Lo E.H., Terry E., Milne G.L., Hubbard J., Lee H., Stevenson E., Lederer M., Furie K.L. Oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in acute ischemic stroke: the biomarker evaluation for antioxidant therapies in stroke (BEAT-stroke) study. Stroke. 2008;39:100–104. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Khosrowbeygi A., Lorzadeh N., Ahmadvand H. Lipid peroxidation is not associated with adipocytokines in preeclamptic women. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2011;9:113–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Kielbasa B., Moeller A., Sanak M., Hamacher J., Hutterli M., Cmiel A., Szczeklik A., Wildhaber J.H. Eicosanoids in exhaled breath condensates in the assessment of childhood asthma. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:660–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kim K.M., Jung B.H., Paeng K.J., Kim I., Chung B.C. Increased urinary F2-isoprostanes levels in the patients with Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2004;64:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Kim J.Y., Hyun Y.J., Jang Y., Lee B.K., Chae J.S., Kim S.E., Yeo H.Y., Jeong T.S., Jeon D.W., Lee J.H. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A(2) activity is associated with coronary artery disease and markers of oxidative stress: a case-control study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;88:630–637. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.3.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ko F.W., Lau C.Y., Leung T.F., Wong G.W., Lam C.W., Hui D.S. Exhaled breath condensate levels of 8-isoprostane, growth related oncogene a and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Med. 2006;100:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Kojima H., Sakurai S., Uemura M., Fukui H., Morimoto H., Tamagawa Y. Mitochondrial abnormality and oxidative stress in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:S61–S66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kong S.Y., Bostick R.M., Flanders W.D., McClellan W.M., Thyagarajan B., Gross M.D., Judd S., Goodman M. Oxidative balance score, colorectal adenoma, and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014;23:545–554. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Konishi M., Iwasa M., Araki J., Kobayashi Y., Katsuki A., Sumida Y., Nakagawa N., Kojima Y., Watanabe S., Adachi Y., Kaito M. Increased lipid peroxidation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis C as measured by the plasma level of 8-isoprostane. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;21:1821–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Koskela H.O., Purokivi M.K., Nieminen R.M., Moilanen E. Asthmatic cough and airway oxidative stress. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2012;181:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]