ABSTRACT

The optimal sequencing of targeted treatment and immunotherapy in the treatment of advanced melanoma is a key question and prospective studies to address this are ongoing. Previous observations suggest that treating first with targeted therapy may select for more aggressive disease, meaning that patients may not gain full benefit from subsequent immunotherapy. In a single-center retrospective analysis, we investigated whether response to pembrolizumab was affected by previous BRAF inhibitor therapy. A total of 42 patients with metastatic cutaneous or mucosal melanoma who had received previous treatment with ipilimumab were treated with pembrolizumab as part of the Italian expanded access program. Sixteen of these patients had BRAF-mutated melanoma and had also been previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib or dabrafenib), while 26 had BRAF wild-type melanoma (no previous BRAF inhibitor). Patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma who were previously treated with BRAF inhibitors had a significantly lower median progression-free survival (3 [2.3–3.7] versus not reached [2–8+] mo; p = 0.001) and disease control rate (18.6% versus 65.4%; p = 0.005) than patients with BRAF wild-type, while there was also a trend toward a lower response rate (assessed using immune-related response criteria) although this was not significantly different between groups (12.5% versus 36.4%; p = 0.16). These data are consistent with previous reports that BRAF inhibitor therapy may affect subsequent response to immunotherapy.

KEYWORDS: Anti-PD-1 antibodies, BRAF inhibitors, immunotherapy, melanoma, pembrolizumab

Abbreviations

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte antigen-4

- DCR

disease control rate

- EAP

expanded access program

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ORR

overall response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1

- PFS

progression-free survival

Introduction

Treatment outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma have greatly improved in recent years with the advent of several novel agents. These treatments include targeted therapies (the BRAF-inhibitors dabrafenib and vemurafenib and the MEK inhibitors trametinib and cobimetinib) as well as immunomodulating monoclonal antibodies (the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab and the anti-PD-1 antibodies pembrolizumab and nivolumab). Treatment with these agents as monotherapy has resulted in median overall survival (OS) of 17–20 mo.4,6,12,16,3 Even greater improvements have been achieved through the use of combination approaches. These include combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with dabrafenib plus trametinib in the COMBI-d and COMBI-v studies (Long12; Robert16 and vemurafenib plus cobimetinib in the COBRIM trial3 (median OS: 25.1, 25.6 and 22.3 mo, respectively), as well as combined immunotherapies such as ipilimumab plus nivolumab.23,10

The combination of targeted agents with immunotherapy is also being investigated with the challenge being how to optimally combine these two distinct classes of drugs. Preclinical data suggest that the use of BRAF/MEK inhibitors can result in activation of the immune system21,19, suggesting that targeted agents and immunotherapy may have synergistic modes of action. However, initial studies of concurrent BRAF inhibitor and immunotherapy resulted in tolerability problems, notably increased hepatotoxicity with concurrent vemurafenib and ipilimumab.15 Studies of other targeted agent and immunotherapy combinations remain ongoing. For example, the anti-PD-L1 agent, durvalumab combined with trametinib and dabrafenib, at full doses showed evidence of clinical activity with a manageable safety profile in 50 patients in a phase I study of patients with BRAF wild-type and BRAF-mutant melanoma.14 Similarly, 17 patients with BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma treated with vemurafenib in combination with the anti-PD-L1 atezolizumab had a 76% response rate and no grade ≥ 4 adverse events in a preliminary report of a phase I trial.18 Interestingly, patients who received staggered dosing (starting on vemurafenib 960 mg twice daily before switching to a lower 720 mg dose twice daily combined with atezolizumab) had a better response and fewer adverse events than patients starting treatment with the two agents concurrently. In a preliminary report from an expansion cohort of this trial, 14 patients treated with the triple combination of vemurafenib, cobimetinib and atezolizumab (added after a 28-d lead-in with vemurafenib plus cobimetinib) had a manageable safety profile with promising antitumor activity after a median follow-up of 5.6 mo.9

The initial disappointments with concurrent use of targeted and immunomodulating agents focused attention on sequential dosing as another potential strategy. However, this raises the key issue of whether targeted agent followed by immunotherapy or vice versa is the most appropriate sequence of treatment. To address this, it is important to consider the different effects of these two drug classes. While targeted therapy is associated with an early response and a high response rate, immunotherapy has a more durable response with the potential for long-term benefit.2 Moreover, use of upfront targeted therapy may select for more aggressive disease, with approximately 40–50% of patients that fail treatment with a BRAF inhibitor having a more rapid disease progression than those who have not received BRAF inhibitor therapy.5 The potential for these patients to receive optimal clinical benefit from subsequent immunotherapy is limited since there may be insufficient time to complete all treatment cycles.

Prospective studies to inform optimal sequencing of targeted treatment and immunotherapy are underway. However, in the meantime, we are reliant on evidence from real-world experience to best guide clinical practice. In this single-center retrospective analysis, we investigated whether treatment response was affected by previous BRAF inhibitor therapy in patients with ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab.

Results

A total of 47 patients (male, n = 25; female, n = 22) were treated with pembrolizumab after disease progression or unacceptable toxicity on ipilimumab. Median age was 49 y (range 28–70) and all patients had stage M1c disease. Forty patients had cutaneous metastatic melanoma, while five had ocular disease and two had mucosal disease. The five patients with ocular metastatic melanoma were excluded from this analysis since this is considered a distinct entity with a different biology. Thus, data on 42 patients were analyzed. Characteristics of patients before and after targeted therapy (BRAF-mutant) or before and after ipilimumab (BRAF wild-type) and before pembrolizumab are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics before starting and after targeted therapy (BRAF mutant), and before starting and after ipilimumab (BRAF wild-type).

| BRAF mutated (n=16) |

BRAF wild-type (n=26) |

|||

| Characteristic |

Before target therapy |

After target therapy |

Before ipilimumab |

After ipilimumab |

| LDH levels | ||||

| Elevated (> 2) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Elevated ( >1 and ≤ 2) | 3 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| Normal | 10 | 6 | 13 | 12 |

| Visceral sites | ||||

| ≥ 3 sites | 12 | 12 | 11 | 8 |

| < 3 sites | 4 | 4 | 15 | 18 |

| Performance status | ||||

| 0 | 11 | 3 | 14 | 11 |

| 1 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 15 |

| Targeted therapy | ||||

| Vemurafenib | 14 | NA | NA | NA |

| MEK inhibitor | 2 | |||

| Previous line of treatment | ||||

| 0 | 15 | NA | 4 | NA |

| 1 | 1 | 22 | ||

| Previous treatments | ||||

| Dacarbazine | 0 | NA | 21 | NA |

| Temozolomide | 0 | 1 | ||

| MEK inhibitor | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ipilimumab | 1 | 0 | ||

Table 2.

Patient characteristics before starting pembrolizumab.

| Characteristic |

BRAF mutated (n=16) |

BRAF wild-type (n=26) |

Total (N=42) |

| Sex (male/female) | 8/8 | 15/11 | 25 (53%)/22 (47%) |

| Age, years (median, range) | 30 (28–60) | 55 (42–70) | 49 (28–70) |

| Histology | |||

| Cutaneous | 16 | 24 | 40 (95.2%) |

| Mucosal | 2 | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Disease stage IV M1C | 16 | 26 | 42 |

| With brain metastases | 6 (37.5%) | 3 (11.5%) | 9 (21.4%) |

| Without brain metastases | 10 (62.5%) | 23 (88.5%) | 33 (78.6%) |

| LDH levels | |||

| Elevated (> 2) | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Elevated ( >1 and ≤ 2) | 11 | 11 | 22 |

| Normal | 5 | 12 | 17 |

| Visceral sites | |||

| ≥ 3 sites | 13 | 14 | 27 (64.3%) |

| < 3 sites | 3 | 12 | 15 (35.7%) |

| Performance status | |||

| 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 (33%) |

| 1 | 12 | 16 | 28 (67%) |

| Previous line of treatment | |||

| 1 | 0 | 4 (15.4%) | 4 (9.5%) |

| 2 | 16 (100%) | 22 (84.6%) | 38 (90.5%) |

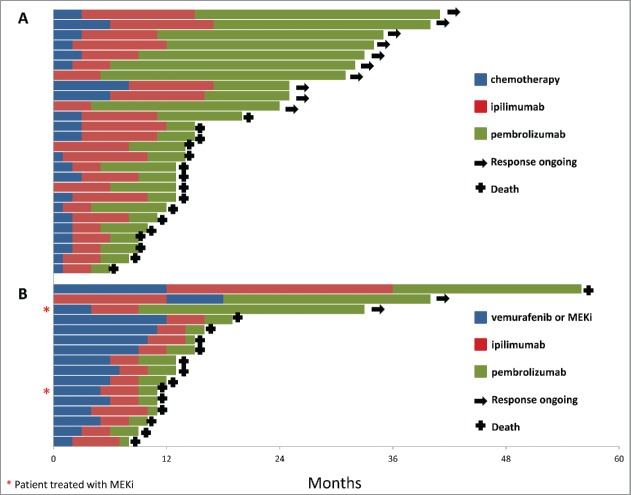

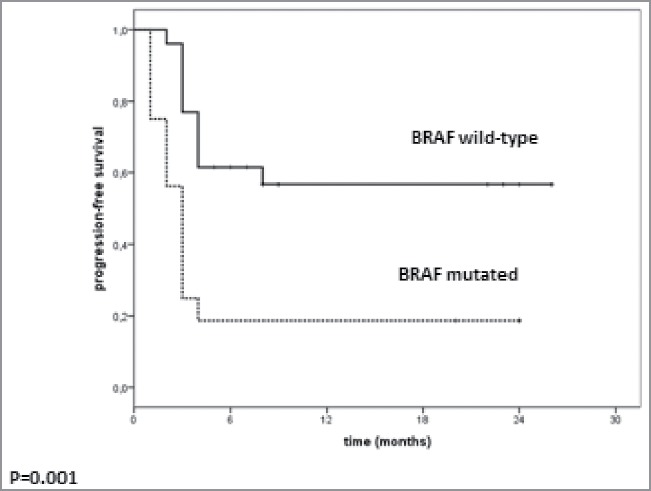

Of the 42 patients, 16 had BRAF V600-mutant melanoma and had been previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor and 26 had BRAF wild-type melanoma. The median duration of response to BRAF inhibitor was 9 mo (range 4–12 mo). The two patients treated with MEK inhibitor as first-line treatment had a duration of response of 2 and 12 mo. Response rate on pembrolizumab was 12.5% (n = 2/16) in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma compared with 36.4% (n = 9/26) in BRAF wild-type patients. Individual patient treatment and duration of response for the BRAF-mutant and BRAF wild-type group are shown in Fig. 1. Patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma treated as third-line (22/26; 84.6%) had a better outcome than patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma treated with pembrolizumab as third line. This difference in response rate was not statistically significant (p = 0.16). However, DCR was significantly lower (p = 0.005) in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma compared with patients in the BRAF wild-type cohort (18.6% [n = 3/16] versus 65.4% [n = 17/26]). Progression-free survival (PFS) also significantly differed (p = 0.001) between groups, with a median of 3 mo (range 2.3–3.7) in the BRAF-mutant group and not reached in the BRAF wild-type group (range 2–8+ mo) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Patient treatment and duration of response: (A) BRAF wild-type group, (B) BRAF- mutant group.

Figure 2.

Median PFS in patients treated with pembrolizumab according to BRAF mutational status

Discussion

New treatments have resulted in significant improvements in OS for patients with advanced melanoma. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition has resulted in median OS of over 2 y with around 50% of patients alive after 2 y,12,16,3 while treatment with pembrolizumab and nivolumab has also provided a similarly prolonged survival benefit, with 2-y survival rates of 55–58%7,17 However, across clinical trials, patients treated with the BRAF and MEK inhibitors typically have a longer median PFS and a higher response rate, while patients treated with immunotherapies have a longer median duration of response.2 Thus, targeted agents offer high and rapid responses albeit with relatively shorter duration, whereas immunomodulating antibodies have a slower onset of action (although pembrolizumab and nivolumab are faster than ipilimumab) but potentially offer long-term disease control with a longer OS “tail.” On this basis, it has been suggested that, although targeted therapy may be preferable in patients with high tumor burden and symptomatic disease who need rapid improvement, upfront treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors may be favored for patients who do not require such rapid symptom control11 However, to date there is limited clinical evidence on which sequence of treatment may be optimal.

Clearly, prospective clinical trials are required to answer this question and such trials are ongoing. These include the ECOG phase III study (NCT02224781) that will compare sequential dabrafenib plus trametinib followed by ipilimumab plus nivolumab after progression with the reverse sequence in patients with stage III–IV BRAF V600 melanoma. Another trial, the prospective three-arm randomized phase II SECOMBIT study (NCT02631447) will compare a sequential approach with combination immunotherapy (ipilimumab plus nivolumab) followed by combination targeted therapy (encorafenib plus binimetinib) on disease progression or vice versa. A third arm will assess whether a run-in phase of encorafenib plus binimetinib of 8 weeks before combination immunotherapy (followed by combination targeted therapy) might help potentiate an immunotherapeutic response.

However, while we await data from these prospective studies, it is necessary to extrapolate from real-world experience. Retrospective analyses have suggested that treatment with immunotherapy following BRAF or MEK inhibitors may be associated with poorer outcomes. In one study, longer PFS and OS were observed among patients treated with immunotherapy (ipilimumab or interleukin-2) before BRAF inhibitor (n = 32) compared with vice versa (n = 242) (PFS: 6.7 versus 5.6 mo; OS: 19.6 versus 13.4 mo). Outcomes for patients treated with ipilimumab following BRAF inhibitor discontinuation were poor, with only half able to complete four cycles of ipilimumab and a median PFS of 2.7 mo and median OS of 5.0 mo.1 Similarly, in previously reported data from our center, median OS among 28 patients treated with a BRAF inhibitor who subsequently received ipilimumab was 5.7 mo for those who had rapid disease progression and were unable to complete ipilimumab treatment compared with 18.6 mo (p < 0.0001) for patients who completed ipilimumab treatment4 In another analysis, 93 patients with BRAF V600-mutated melanoma who received vemurafenib or dabrafenib before being treated with ipilimumab as part of the Italian EAP had median OS of 1.2 mo among those who did not complete ipilimumab treatment compared with 12.7 mo for those who did (p < 0 .001).6

These data suggest that treating first with targeted therapy may select for more aggressive disease, resulting in rapid disease progression and death and meaning that patients are unable to gain full benefit from subsequent immunotherapy. Although combined BRAF and MEK inhibition treatment has better outcomes and may be less selective for aggressive disease than BRAF inhibition alone, while anti-PD-1 therapy has a faster onset of effect than ipilimumab, the question of whether targeted treatments affects response to subsequent immunotherapy remains critical.

Further evidence that BRAF inhibitor therapy may influence subsequent response to immunotherapy with anti-PD-1 treatment is provided by studies of pembrolizumab. In the phase Ib KEYNOTE-001 study, pembrolizumab resulted in a lower overall response rate (ORR) in patients previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor compared with the total cohort (23.7% versus 33.4%).8 In addition, patients with BRAF-mutant tumors had a lower ORR than patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma (26.3% versus 35.5%). Analysis of patients receiving pembrolizumab as first-line therapy suggested that it was prior therapy with a BRAF inhibitor, rather than the BRAF mutation itself, that may have been the driver of the lower response since ORR was similar in the total, BRAF wild-type and BRAF mutant cohorts (45.1% versus 45.0% versus 50.0%). More data are provided by the phase II KEYNOTE-002 study in which patients with ipilimumab-refractory melanoma were randomized to pembrolizumab or investigator-choice chemotherapy.13 Patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma had longer PFS than patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma in both the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy arms; in the pooled pembrolizumab arms, median PFS was 3.8 mo in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma versus 2.8 mo in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma, while 6-mo PFS rate was 40.9% versus 19.5%. ORR was also higher in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma than in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma in the pembrolizumab arm (26.7% versus 11.9%). However, in the phase III KEYNOTE-006 trial, in which patients (BRAF wild-type and mutated) were randomized to first-line pembrolizumab or ipilimumab, PFS was similar in patients with BRAF wild-type and BRAF-mutant melanoma (median: 5.7 versus 4.0 mo; 6-mo PFS: 49.3% versus 43.2%), although there was a trend toward a better response in the BRAF wild-type patients.13 Among patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma, those who were not previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor had longer PFS than patients who received previous BRAF inhibitor (median: 7.0 versus 2.8 mo; 6-m PFS: 52.7% versus 32.2%). Similar observations have also been made for nivolumab. In the CHECKMATE-037 study of nivolumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy in patients who progressed after treatment with ipilimumab or ipilimumab and a BRAF inhibitor if they had BRAF-mutant melanoma, a better response rate was observed in BRAF wild-type than BRAF-mutant patients (34% versus 23%).20

Although our study should be interpreted with some caution, given the small numbers of patients and the limitations of a retrospective, single-center analysis, the data are consistent with previous observations that BRAF inhibitor therapy may affect subsequent response to immunotherapy. Patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma who were previously treated with BRAF inhibitors had a significantly lower median PFS and DCR than patients with BRAF wild-type, while there was also a trend toward a lower response rate, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Since all BRAF-mutant patients received BRAF inhibitor therapy as per the EAP protocol, it is not possible to differentiate the effects of BRAF mutation versus BRAF inhibitor therapy on treatment response. Another limitation is that the treatment landscape in advanced melanoma is rapidly evolving and anti-PD-1 therapy is now standard before ipilimumab. However, our data at least appear to be consistent with those reported in the KEYNOTE-006 study in which pembrolizumab was used as first-line.13

While we await the results of ongoing prospective clinical studies to inform the best approach for sequencing targeted and immune-based therapies in BRAF-mutant melanoma, preliminary evidence from retrospective and real-world studies increasingly suggests that targeted therapy may negatively affect the response to subsequent treatment with pembrolizumab and other immunotherapies. It is possible that perhaps not all patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma should be treated with first-line BRAF-MEK inhibitor therapy, but at this stage which patients would benefit from upfront targeted therapy before immunotherapy is not known.

Materials and methods

Patients aged ≥ 18 y with unresectable stage III melanoma or metastatic stage IV melanoma were eligible for treatment with pembrolizumab at the Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione Pascale, Napoli, Italy, as part of an expanded access program (EAP). Patients could receive pembrolizumab, if they had previously received treatment with ipilimumab (ipilimumab refractory), at dosage of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks IV for up to 2 y until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity and had an ECOG performance status of 0–1. Patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma were also previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib 960 mg twice daily or dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily) as per the EAP protocol. Patients with a history of severe auto-immune disease or active brain metastases were excluded. The protocol for the EAP was approved by a local independent ethics committee and all participating patients provided signed informed consent before enrolment.

Tumor response, disease control rate (DCR) and PFS were analyzed according to previous BRAF inhibitor therapy. Tumor response was assessed using immune-related response criteria.22 The association between previous BRAF inhibitor therapy (patients with prior BRAF inhibitor treatment) and clinical response to pembrolizumab was evaluated using Fisher's exact test. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the between-group difference.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Ester Simeone participated to advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb and received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. Antonio M. Grimaldi participated in an advisory board for Novartis and received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis. Paolo A. Ascierto has/had advisory or consultant roles for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche-Genentech, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Amgen, Array, and Merck Serono. All the other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

A special thanks to Alessandra Trocino, for providing excellent bibliography service and assistance.

Funding

The EAP was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD). Paolo A. Ascierto received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche-Genentech, and Array.

References

- 1.Ackerman A, Klein O, McDermott DF, Wang W, Ibrahim N, Lawrence DP, Gunturi A, Flaherty KT, Hodi FS, Kefford R et al.. Outcomes of patients with metastatic melanoma treated with immunotherapy prior to or after BRAF inhibitors. Cancer 2014; 120:1695-701; PMID:24577748; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.28620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascierto PA, Long GV. Progression-free survival landmark analysis: a critical endpoint in melanoma clinical trials. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17:1037-9; PMID:27324281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Di Giacomo AM, Mandalà M, Demidov L, Stroyakovskiy D, Thomas L et al.. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17:1248-60; PMID:27480103; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30122-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascierto PA, Simeone E, Giannarelli D, Grimaldi AM, Romano A, Mozzillo N. Sequencing of BRAF inhibitors and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma: a possible algorithm for clinical use. J Transl Med 2012; 10:107; PMID:22640478; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1479-5876-10-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascierto PA, Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Curvietto M, Esposito A, Palmieri G, Mozzillo N. Do BRAF inhibitors select for populations with different disease progression kinetics? J Transl Med 2013; 11:61; PMID:23497384; http://dx.doi.org/24484235 10.1186/1479-5876-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascierto PA, Simeone E, Sileni VC, Del Vecchio M, Marchetti P, Cappellini GC, Ridolfi R, de Rosa F, Cognetti F, Ferraresi V et al.. Sequential treatment with ipilimumab and BRAF inhibitors in patients with metastatic melanoma: data from the Italian cohort of the ipilimumab expanded access program. Cancer Invest 2014; 32:144-9; PMID:24484235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/07357907.2014.885984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkinson V, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, McNeil C et al.. Two-year survival and safety update in patients (pts) with treatment-naïve advanced melanoma (MEL) receiving nivolumab (NIVO) or dacarbazine (DTIC) in CheckMate 066. J Transl Med 2016; 14(Suppl 1):S65 (abstract O9) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daud A, Ribas A, Robert C, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Joshua AM, Hwu W-J, Weber JS, Gangadhar TC, Joseph RW et al.. Long-term efficacy of pembrolizumab (pembro; MK-3475) in a pooled analysis of 655 patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL) enrolled in KEYNOTE-001. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:(suppl; abstr 9005) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwu P, Hamid O, Gonzalez R, Infante JR, Patel MR, Hodi F, Lewis KD, Wallin J, Mwawasi G, Cha E et al.. Preliminary safety and clinical activity of atezolizumab combined with cobimetinib and vemurafenib in BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 379-40026681681 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P et al.. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:23-34; PMID:26027431; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau PK, Ascierto PA, McArthur G. Melanoma: the intersection of molecular targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibition. Curr Opin Immunol 2016; 39:30-8; PMID:26765776; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, Garbe C, Jouary T, Hauschild A, Grob JJ et al.. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386:444-51; PMID:26037941; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puzanov I, Ribas A, Daud A, Nyakas M, Margolin KA, O'Day SJ, Lutzky J, Tarhini A, Li XN, Zhou H et al.. Pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma: effect of BRAFV600 mutation status and prior BRAF inhibitor therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res J 2015; 392-3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribas A, Butler M, Lutzky J, Lawrence DP, Robert C, Miller W, Linette GP, Ascierto PA, Kuzel T, Algazi AP et al.. Phase I study combining anti-PD-L1 (MEDI4736) with BRAF (dabrafenib) and/or MEK (trametinib) inhibitors in advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:1865-6; (suppl; abstr 3003); PMID:25667273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribas A, Hodi FS, Callahan M, Konto C, Wolchok J. Hepatotoxicity with combination of vemurafenib and ipilimumab. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1365-6; PMID:23550685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMc1302338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroyakovskiy D, Lichinitser M, Dummer R, Grange F, Mortier L et al.. Two year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib versus vemurafenib as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K mutation-positive cutaneous melanoma. In: Abstract presented at the Euro Cancer Congress, September 28, 2015, 2015; Abstract 3301. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil CM, Lotem M et al.. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival analysis of KEYNOTE-006. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34 (suppl; abstr 9504) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan R, Hamid O, Patel M, Hodi S, Amaria R, Boasberg P, Wallin J, He X, Cha E, Richie N et al.. Preliminary clinical safety, tolerability and activity results from a Phase Ib study of atezolizumab (anti-PDL1) combined with vemurafenib in BRAFV600-mutant metastatic melanoma. J Transl Med 2016, 14(Suppl 1):S65 (abstract O6) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wargo J, Cooper Z, Flaherty K. Universes collide: combining immunotherapy with targeted therapy for cancer. Cancer Discov 2014; 4:1377-86; PMID:25395294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, Hoeller C, Khushalani NI, Miller WH Jr, Lao CD et al.. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:375-84; PMID:25795410; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilmott J, Long GV, Howle JR, Haydu LE, Sharma RN, Thompson JF, Kefford RF, Hersey P, Scolyer RA. Selective BRAF inhibitors induce marked T-cell infiltration into human metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18:1386-94; PMID:22156613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O'Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, Maio M, Binder M, Bohnsack O, Nichol G et al.. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:7412-20; PMID:19934295; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K et al.. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:122-33; PMID:23724867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]