ABSTRACT

Amino-bis-phosphonates (N-BPs) such as zoledronate (Zol) have been used in anticancer clinical trials due to their ability to upregulate pyrophosphate accumulation promoting antitumor Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. The butyrophilin 3A (BTN3A, CD277) family, mainly the BTN3A1 isoform, has emerged as an important structure contributing to Vγ9Vδ2 T cells stimulation. It has been demonstrated that the B30.2 domain of BTN3A1 can bind phosphoantigens (PAg) and drive the activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells through conformational changes of the extracellular domains. Moreover, BTN3A1 binding to the cytoskeleton, and its consequent membrane stabilization, is crucial to stimulate the PAg-induced tumor cell reactivity by human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Aim of this study was to investigate the relevance of BTN3A1 in N-BPs-induced antitumor response in colorectal cancer (CRC) and the cell types involved in the tumor microenvironment.

In this paper, we show that (i) CRC, exposed to Zol, stimulates the expansion of Vδ2 T lymphocytes with effector memory phenotype and antitumor cytotoxic activity, besides sensitizing cancer cells to γδ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity; (ii) this effect is partially related to BTN3A1 expression and in particular with its cellular re-distribution in the membrane and cytoskeleton-associated fraction; (iii) BTN3A1 is detected in CRC at the tumor site, both on epithelial cells and on tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF), close to areas infiltrated by Vδ2 T lymphocytes; (iv) Zol is effective in stimulating antitumor effector Vδ2 T cells from ex-vivo CRC cell suspensions; and (v) both CRC cells and TAF can be primed by Zol to trigger Vδ2 T cells.

KEYWORDS: Amino-bis-phosphonates, butyrophilin, colorectal cancer, immunostimulation, phosphate antigens

Introduction

Gammadelta (γδ) T lymphocytes are involved in stress responses to injured, infected or transformed cells.1,2 The most representative γδ T cell subset in the blood is the Vγ9Vδ2 (3–5% of circulating T lymphocytes), while the subset bearing the Vδ1 chain is <1–2% and is mainly present in the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue.1-3 Vδ2 T lymphocytes recognize unprocessed non-peptide molecules, including phosphoantigens (PAg) derived from the mevalonate pathway in mammalian cells, and via the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway, in bacterial cells.1-5 γδ T cells also recognize NKG2D ligands (MICA, MICB and ULBPs), overexpressed at the cells surface by viral infections or tumor transformation.1-3 Another activation signal can be delivered via FcγRIIIa/CD16 that, upon interaction with the Fc of IgG, initiates the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity to destroy opsonized cells or microorganisms.1-3 After activation, γδ T cells proliferate, acquire cytotoxic ability and secrete a pattern of Th1 pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNFα.1,2 For this unconventional antigen recognition and multiple activation pathways, γδ T lymphocytes are antitumor effector cells in several cancer types, including colorectal cancer (CRC), and potential suitable tools for anticancer therapy.3-8

Different drugs can be utilized to improve the mechanisms of γδ T cell activation:2,3,8 in particular, synthetic pyrophosphate-containing compounds have been proposed for cancer immunotherapy on the basis of their ability to stimulate γδT cells.9-12 Moreover, aminobisphosphonates (N-BPs), in addition to their effect of inhibiting osteoclastic bone resorption,13 lead to γδ T cell activation and proliferation, with a consequent increased number of γδ T cells in peripheral blood, displaying antitumor activity14-18 Indeed, N-BPs, such as zoledronate (Zol), are chemically stable analogs of inorganic pyrophosphate (IPP) that inhibit the mevalonate pathway and upregulate IPP accumulation, promoting antitumor Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in vitro and in vivo.15-20 For this reason, different N-BPs have been used in anticancer clinical trials.21-24

In the last years, the butyrophilin 3A (BTN3A, CD277) family, structurally related to B7 co-stimulatory molecules, has emerged as important structure contributing to Vγ9Vδ2 T cell stimulation.25,26 This family in humans is composed of three isoforms: BTN3A1, BTN3A2 and BTN3A3, characterized by two extracellular immunoglobulin domains, a transmembrane region and all, but BTN3A2, by a intracellular signaling domain, named B30.2.27,28 It has been demonstrated that only the B30.2 domain of BTN3A1, thanks to a positively-charged pocket, can bind PAg and drive the activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells through conformational changes of the extracellular domains.29-31 Two recent reports describe the importance of BTN3A1 binding to the cytoskeleton, and its consequent membrane stabilization, to stimulate the PAg-induced tumor cell reactivity by human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells;32 PAg accumulation would also induce BTN3A1 conformational changes responsible for its recognition by Vδ2 T cells.33

In this paper, we show that (i) colon cancer cells, exposed to Zol, stimulate the expansion of Vδ2 T cells with effector memory (EM) phenotype and cytotoxic activity; (ii) this effect is partially related to BTN3A1 expression and cellular re-distribution; (iii) BTN3A1 is detected in CRC at the tumor site, both on epithelial and on stromal cells, close to areas infiltrated by Vδ2 T lymphocytes; (iv) Zol is effective in stimulating antitumor effector Vδ2 T cells from ex-vivo CRC cell suspensions; and (v) both CRC cells and tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF) can be primed by Zol to trigger Vδ2 T cells.

Results

CRC exposed to Zol stimulate the expansion of Vδ2 T cells with antitumor cytotoxic activity

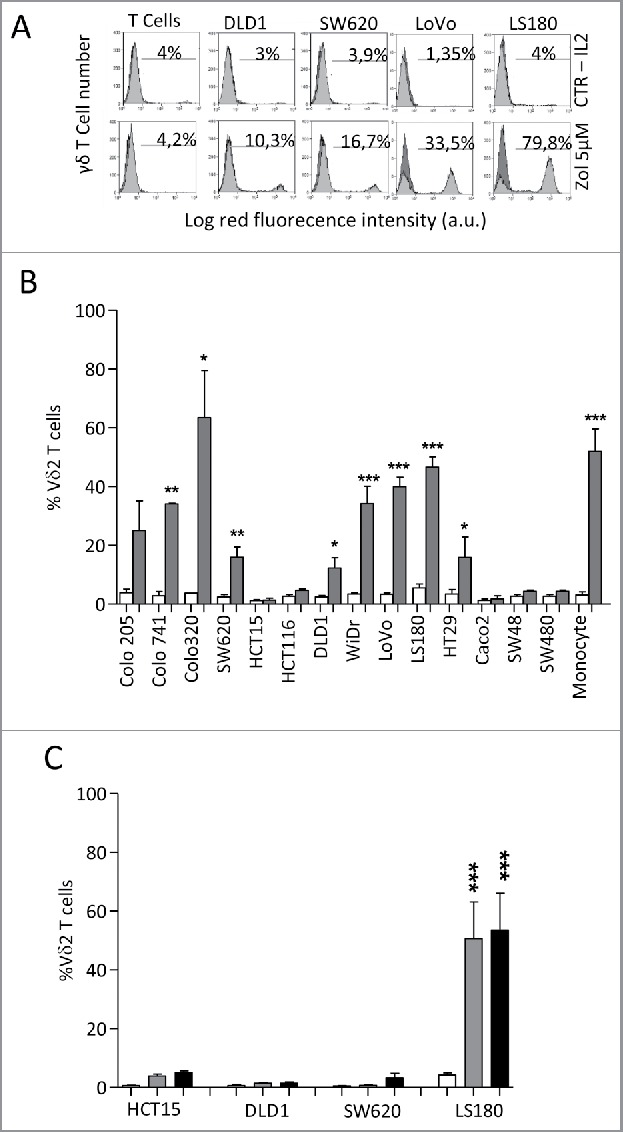

Fourteen different established CRC cell lines (Colo205, Colo741, Colo320, SW620, HCT15, HCT116, DLD1, WiDr, LoVo, LS180, HT29, CaCo2, SW48 and SW480) were co-cultured with peripheral blood T cells from healthy donors, at the T:CRC ratio of 10:1, in the presence or absence of 5 µM Zol and IL2. As shown in Fig. 1, many of these CRC cell lines (LS180, LoVo, WiDr, Colo741, Colo320 and to a lesser extent SW620, HT29, DLD1 and Colo205), when exposed to Zol, were able to induce the expansion of γδ T lymphocytes, after 20 d of culture (Figs. 1A and 1C, 4 representative CRC cell lines; Fig. 1B, all the cell lines tested, mean ± SD from six experiments with six different T cell donors for each cell line). Indeed, the percentage of γδ T lymphocytes raised from less than 5% in the starting T cell populations (range 2–5%, not shown), up to 80% in the co-cultures with Zol-treated CRC (Fig. 1A lower panels vs. IL2 alone in upper panels; Fig. 1B dark gray columns), values superimposable to those obtained using monocytes16 exposed to Zol (Fig. 1B). No expansion of γδ T cells was detected in the co-cultures set up in the absence of Zol (Fig. 1A upper panels and Fig. 1B white columns). Zol added to purified T cells alone did not exert any stimulating effect (Fig. 1A, lower left panel, one representative experiment).

Figure 1.

Vδ2 T cell expansion upon co-culture with CRC exposed to Zol.The CRC cell lines HT29, HCT15, HCT116, SW48, SW620, SW480,Colo741, Colo205, Colo320, CaCo2, LS180, WiDr, LoVo and DLD1were co-cultured for 20 d with peripheral blood T cells from healthy donors, at the T:CRC ratio of 10:1, with 5 µM Zol and IL2 or IL2 alone. (A) percentage of Vδ2 T lymphocytes among one representative T cell population cultured alone (left histograms) and after co-culture with CRC (other panels, four representative CRC cell lines) with Zol (lower row) or IL2 alone (upper row) evaluated with the anti-Vδ2 mAb and FACS analysis. Data are represented as percentage of Vδ2 T cells (light gray histograms) reported in each quadrant. (B) percentage of Vδ2 T lymphocytes after 20 d of co-culture with the indicated CRC cell lines with Zol (gray columns) or IL2 alone (white columns). Data are the mean ± SD from six experiments for each cell line. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001 vs. co-cultures without Zol. (C) SW620, HCT15, DLD1 and LS180 CRC cell lines were pre-treated (4 h) with high doses (100 µM, black bars, or 50 µM, gray bars) of Zol, washed and co-cultured with purified T cells as above, and evaluated for the percentage of Vδ2 T lymphocytes after 20 d of co-culture. Mean ± SD from six experiments with T cells of six different donors. ***p <0.001 vs. co-cultures without Zol (white bars).

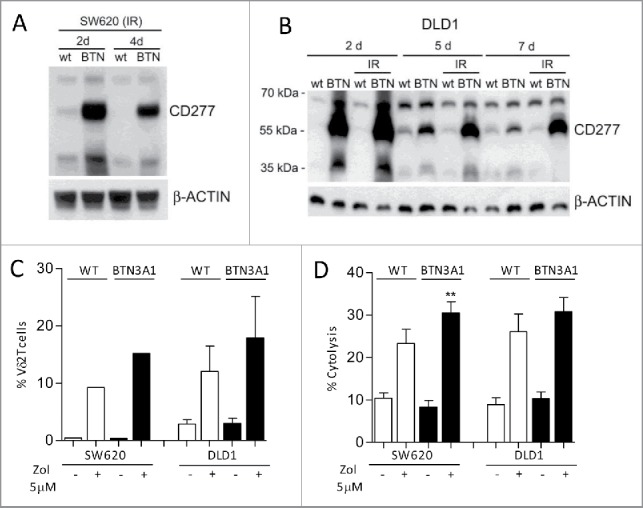

Figure 4.

Enhancement of BTN3A1 expression and expansion of antitumor Vδ2 T cells. SW620 (A, C, D) or DLDL1 (B, C, D) cells were transfected with BTN3A1-containing plasmid and irradiated to avoid the overgrowth of untransfected cells; expression was evaluated on day 2, 5 and 7 by western blot using the anti-CD277 (A, B). (C) Wild type (WT, white columns) or BTN3A1-transfected (black columns) SW620 or DLD1 cells, untreated or treated with Zol (5 µM), as indicated were co-cultured with purified T lymphocytes: the percentage of Vδ2 T cells was evaluated by immunofluorescence with the specific anti-Vδ2 mAb and FACS analysis after 20 d of culture; results are expressed as percentage Vδ2 T lymphocytes and are the mean ± SEM from three transfection experiments with six different T cell donors for DLD1; one representative experiment with two T cell donors for SW620. (D) WT (white columns) or BTN3A1-tranfected (black columns) SW620 or DLD1 cells, untreated or treated with Zol (5 µM) as indicated, were used as targets in a 4 h 51Cr release assay using as effectors IL-2-activated peripheral blood Vδ2 T cells at the E:T ratio of 10:1. Results are expressed as percentage specific lysis, calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and are the mean ± SEM from three experiments.**p <0.01 vs. Zol-treated WT SW620.

As it has been reported that several tumor cell lines require higher doses of Zol to exert their stimulating activity of γδ T cells,34 three low-stimulating (SW620, HCT15, DLD1) and one stimulating (LS180) CRC cell lines were pre-treated (4 h) with high doses (100 µM and 50 µM) of Zol, washed and co-cultured with purified T cells as above. As shown in Fig. 1C, high doses of Zol were effective on LS180 cell line, while the other cell lines did not acquire the ability to stimulate γδ T cell growth even at the highest dose of Zol.

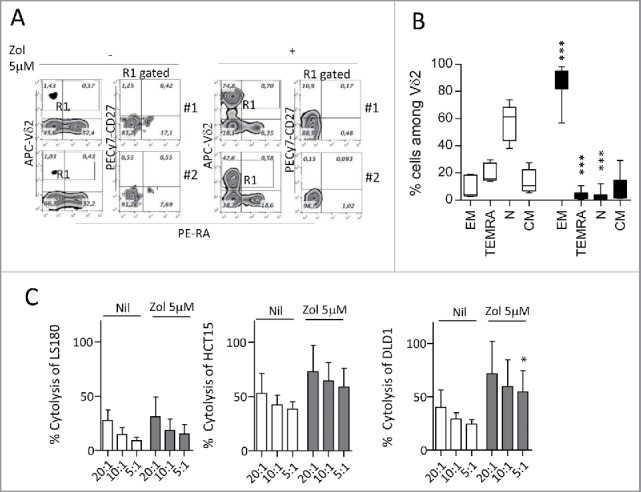

We chose the LS180 cell line as an example of stimulating CRC cells, to analyze the phenotype of the γδ T cell populations obtained after 20 d of culture. In particular, we focused on the distinction of naive (N), bearing CD27 and CD45RA molecules, central memory (CM), showing only CD27, EM that are double negative, and terminal-differentiated memory cells (TEMRA) that are surface positive CD45RA.35,36 We found that upon Zol treatment, LS180 cells could drive the expansion of γδT cells showing the characteristics of EM T lymphocytes (i.e., absence of CD27 and CD45RA) (Fig. 2A, two representative experiments; Fig. 2B mean of eight experiments). Of note, this γδ T cell population exerted a cytotoxic activity against the stimulating LS180 cell line (Fig. 2C, left panel white columns) and against two other cell lines (Fig. 2C white columns: HCT15, central panel; DLD1, right panel); the cytolytic effect was enhanced by exposing the CRC cell lines used as targets to Zol (Fig. 2C, dark gray columns). Similar results, were obtained with WiDr, Colo320 and LoVo stimulating cell lines in two experiments for each cell line (not shown). These data indicate that Zol added to CRC cells, besides determining their sensitization to cytotoxicity exerted by activated γδ T cells, induces the expansion of EM γδ T lymphocytes able to kill both the stimulating tumor cells and other cancer cell lines.

Figure 2.

Expansion of effector memory antitumor Vδ2 T cell lymphocytes upon co-culture with Zol-treated LS180 CRC cell line. Panels A and B: Peripheral blood T lymphocytes were co-cultured for 20 d with LS180 CRC cell line, in the absence or presence of Zol (5 µM) and IL2. (A) Representative phenotype of Vδ2 T cells from two donors (donor 1, upper plots, donor 2, lower plots), co-cultured with LS180 and IL2 alone or with Zol-treated LS180, stained with APC-anti Vδ2, PE-anti-CD27 and PE-Cy7-anti-CD45RA. (B) Results expressed as percentage of effector memory (EM, CD45RA−CD27−) T cells, terminal-differentiated effector memory (TEMRA,CD45RA+-CD27−) T cells, naive (N, CD45RA+CD27+) T cells or central memory (CM, CD45RA−CD27+) among Vδ2 T lymphocytes immediately after separation (white bars) or on day 20 of co-culture with LS180 cells (black bars). Mean ± SD from eight experiments. ***p <0.001 versus T lymphocytes after separation (white bars). (C): Vδ2 T cells derived from co-cultures with Zol-treated LS180 CRC cells were tested in a 4 h 51Cr release assay against untreated (white bars) or Zol-treated (5 µM for 24 h, gray bars) LS180 (left histogram) HCT15 (central histogram) or DLD1 (right histogram) cell lines at the E:T ratio of 20:1, 10:1 and 5:1. Results are expressed as percentage specific lysis, calculated as described in Materials and Methods, the mean ± SD from three experiments is shown. *p <0.05 vs. Nil.

BTN3A1 contributes to zoledronate effect in CRC cell lines

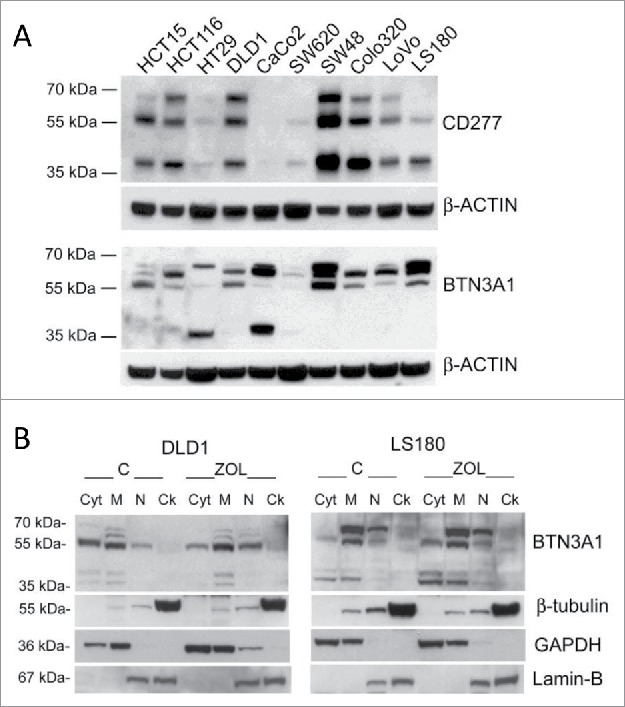

We then investigated the heterogeneity of the stimulating ability displayed by the various CRC cell lines. As BTN3A1 is a molecule essential for the recognition of phosphate antigens by γδ T lymphocytes,25-31 we first analyzed BTN3A1 protein by immunofluorescence and by western blot with the anti-CD277 mAb recognizing the immunoglobulin-like extracellular domain of BTN3A1, or with a rabbit polyclonal anti-BTN3A1 antiserum recognizing the C-terminal domain of the molecule. We found no significant difference in the surface expression of CD277, evaluated by cytofluorimetric analysis; however, the reactivity of this antibody in immunofluorescence is very low, also on healthy monocytes (not shown). In western blot, the same mAb could recognize the major reported bands for BTN3A1 (Fig. 3A, 57 kDa and 37 kDa) in most CRC cell lines, with the exception of CaCo2 cells; the 57 kDa band was identified also by the anti-BTN3A1 antiserum in the majority of cell lines and the 37 kDa band was evident in CaCo2 and HT29 cells (Fig 3A). These data would indicate that the efficiency in Zol stimulating effect is not directly related to the amount of BTN3A1 expressed; indeed, some stimulating cells showed low levels of BTN3A1 in immunoblotting (LoVo), whereas in some low stimulators a strong reactivity was detected (HCT15, HCT116) (Fig. 3). Thus, we asked whether the different distribution of BTN3A1, in particular its membrane localization or cytoskeletal association, was responsible for the activity of the molecule, as recently reported.32,33 We found that in DLD1 (a low-stimulating CRC cell line) a considerable amount of protein is detected in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 3B, left blot, Cyt), probably containing also small vesicles not pelleted at low speed after nuclei isolation, while in the stimulating LS180 cell line BTN3A1 is mainly present in the membrane-enriched fraction (Fig. 3B, right blot, M). Upon Zol treatment, BTN3A1 is also detectable in the cytoskeleton-enriched fraction (that contains detergent-resistant cell-membrane fragments tightly linked to the cytoskeletal proteins, so that they are insoluble) (Fig. 3B, Ck), in agreement with recent reports.33 In addition, it has to be noted that BTNL2, known to downregulate the effect of BTN3A1,27,37 was expressed at very low levels in stimulating cell lines, in particular Colo320, LS180, LoVo, Colo205 and WiDr, at variance with low-stimulating cell lines (Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

BTN3A1 expression and subcellular localization in CRC cell lines. (A) BTN3A1 was evaluated in CRC cell lines by western blot. Immunoblot of cell lysates obtained from the indicated CRC cell lines as described in Materials and Methods, was probed with the anti-CD277 mAb (upper blot), or with a rabbit polyclonal anti-BTN3A1 antiserum (lower blot). β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) BTN3A1 localization in subcellular fractions (Cyt: cytosolic fraction, M: membrane-enriched fraction, N: nuclear fraction, Ck: cytoskeleton-enriched fraction) obtained with the Qproteome cell compartment kit from untreated o Zol-treated (10 µM for 24 h) DLD1 (left panel) or LS180 (right panel), as indicated. In each panel: β-tubulin as marker of Ck fractions, GAPDH for the Cyt/M fractions, lamin B for the N fraction.

In further experiments, we tried to potentiate Zol effect in low-stimulating CRC cell lines, by enhancing BTN3A1 expression. To this aim, SW620 or DLD1 cell lines were transfected with a BTN3A1-containing plasmid and used both as stimulators of Vδ2 T cell growth, and as target cells, upon Zol exposure. Transfected cells were collected at the different time points, irradiated to avoid the overgrowth of untransfected cells, and BTN3A1 expression was evaluated by western blot on day 2, 4 or 5 and 7 after transfection. As shown in Fig. 4, transfection was efficient and BTN3A1 overexpression lasted up to one week (Fig. 4A: SW620 and Fig. 4B: DLD1) and it was not altered by irradiation. Also, the ability to stimulate Vδ2 T cell expansion in the presence of Zol was increased in BTN3A1 transfected, compared with wild type (WT), SW620 and DLD1 cells, although the difference was not significant, due to the variable response of T lymphocytes isolated by three different donors (Fig. 4C). Likewise, SW620 and DLD1 transfected cells acquired a higher sensitivity to Vδ2 T cell killing upon exposure to Zol (Fig. 4D).

Differential IPP production by CRC cell lines upon Zol treatment

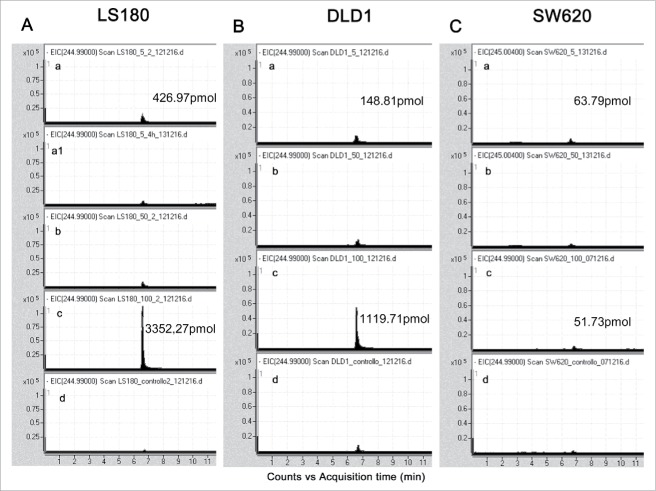

To further investigate the heterogeneity in the stimulating ability displayed by the different CRC cell lines, we measured the IPP production in response to Zol, either as continuous treatment with 5 µM for 24 h, or as pulse treatment of 50 µM and 100 µM for 4 h, by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) negative ion electrospray ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (TOF-MS), in DLD1, SW620, HCT15 (non-stimulating), LS180 and Colo320 (stimulating) cell lines.38 As shown in Fig. 5, LS180 cell line stimulated with Zol 5 µM for 24 h (panel Aa) produced about 3-fold or 7-fold IPP than DLD1 (panel Ba) or SW620 (panel Ca) cells, respectively. In addition, the response of LS180 (Fig. 5Ac) or Colo320 (not shown) and, to a lesser extent, of DLD1 (Fig. 5Bc) cell lines was more evident when treated with a pulse of Zol at high concentrations (100 µM). At variance, SW620 (Fig. 5Cc) and HCT15 (not shown) were not able to enhance IPP production, even when exposed to high Zol concentrations.

Figure 5.

Measurement of IPP produced by SW620, DLD1 or LS180 CRC cell lines upon exposure to Zol. Acetonitrile extracts from LS180 (A), DLD1 (B) and SW620 cells (C) untreated (d) or treated with 5 µM Zol for 24 h (a), or 50 µM (b) and 100 µM (c) Zol for 4 h and maintained in culture for additional 20 h, were analyzed by HPLC/TOF-MS. The relative abundance of the extracted ion current (EIC) (m/z 244.99 [M-H]-) for IPP/DMAPP (3,3-dimethylallyl pyrophosphate) is shown. LS180 cells were also exposed to 5 µM Zol for 4 h (A, a1), to test early effects of low-dose Zol, giving no appreciable increase of IPP over controls. Quantification of IPP produced upon exposure to either 5 µM Zol for 24 h (Aa, Ba, Ca) or 100 µM Zol for 4 h (Ac, Bc, Cc) in the indicated CRC cell lines. Data are shown as IPP pmol/mg of total pmol extracted by ACN/total protein content in cell lysates after ACN extraction.

Zoledronate is effective in stimulating Vδ2 effector T cells from ex-vivo CRC cell suspensions

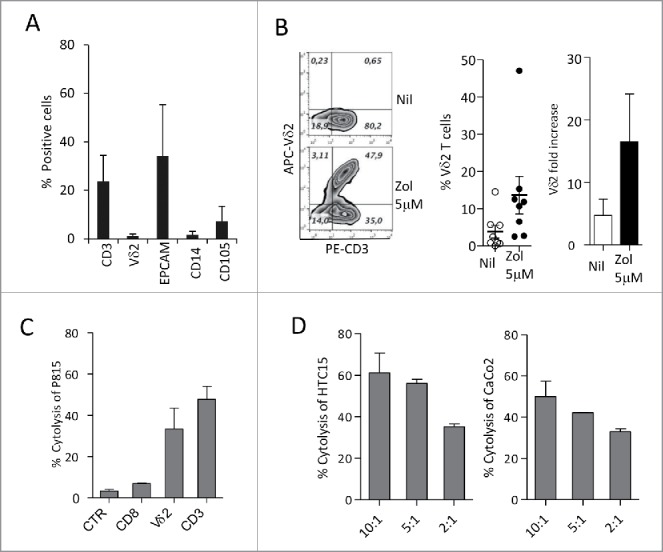

To verify the possible effect of Zol in the tumor microenvironment, we isolated cell suspensions from different CRC specimens and performed cell cultures in the presence or absence of Zol (5 µM on day 0, IL2 added on day 1). As shown by immunofluoresence analysis (Fig. 6A), the starting cell population (FACS analysis in open gate on viable cells on the basis of forward and side scatter, FSC and SSC) was composed of T lymphocytes (CD3+, about 25%), a small fraction of which (< 5%) bearing the Vδ2 T cell receptor, epithelial cells (EPCAM+, from 15 to 55%), 2–5% of monocytes (CD14+) and 5–10% of stromal cells (CD105+, as a marker of mesenchymal cells, Fig. 6A), possibly TAF. After 20 d, in Zol-treated cultures a 10- to 2-fold increase in Vδ2 T lymphocytes was observed in most cases (Fig. 6B, left panels: the best experiment, central and right histograms: mean ± SEM of eight CRC cultures). When tested in re-directed killing assay, the Vδ2-enriched T cell cultures could be activated by the anti-CD3 and anti-Vδ2 mAbs, but not by anti-CD8+ or unrelated mAbs (Fig. 6C); moreover, these cell populations showed a remarkable cytolytic activity against CRC cell lines (Fig. 6D, left and right panels). This data indicate that Zol added to ex-vivo tumor-derived cell suspensions, containing epithelial cells, lymphocytes, TAF and monocytes, is effective in inducing the expansion of infiltrating Vδ2 T cells with potential antitumor activity.

Figure 6.

Differentiation of Vδ2 T cells from ex-vivo CRC cell suspensions. (A) Cell suspensions from CRC were stained with specific anti-CD3, anti-Vδ2, anti-EPCAM, anti-CD14 and anti-CD105 mAbs followed by aAPC-conjugated anti-isotype antiserum and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of positive cells were calculated and results expressed as mean ± SD (n = 10). (B) CRC cell suspensions were cultured in the presence or absence of Zol (5 µM) and IL2 for 20 d, double stained with the specific PE-anti-CD3 and APC-antiVδ2 mAbs and the percentage of positive cells was calculated. Left plots: one representative experiment out of eight. Central histogram: percentage of Vδ2 T cells obtained from CRC cultures without (white) or with Zol (5 µM, black); mean ± SEM of eight experiments. Right histogram: results analyzed as fold increase (percentage of Vδ2 T cells on day 20 vs. day 0, white bar IL2 alone, black bar 5 µM Zol). Mean ± SEM (n = 8). (C and D) Vδ2 T cells obtained from 20 d of CRC cultures, with Zol, were used in re-directed killing assay against the P815 cell line in the presence of the anti-CD8, anti-Vδ2, anti-CD3 mAbs or an unrelated mAb matched for the isotype (CTR) (C) at the E:T ratio of 5:1, or in a 4 h 51Cr release cytolytic assay against the HCT15 or CaCo2 cell lines (D, left and right histograms) at the E:T ratio of 10:1, 5:1 and 2:1. One representative experiment of three is shown. Mean ± SEM of sample duplicate.

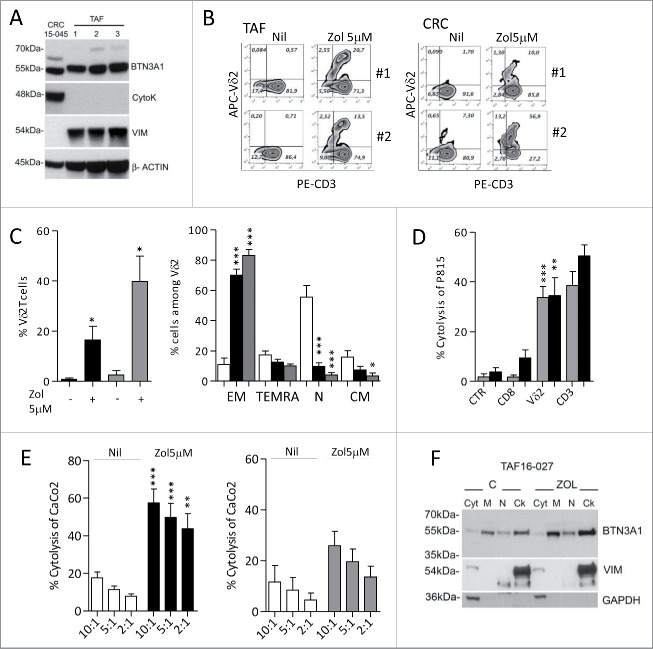

Along this line, we found that TAF isolated from four CRC specimens, characterized as CD105+ (as marker of mesenchymal cells) and FAP+ (not shown), express BTN3A1 (Fig. 7A; note the presence of vimentin and absence of cytokeratin in TAF lysate). When exposed to Zol, TAF were able to induce Vδ2 T cell expansion (Fig. 7B, left panels: one representative case of TAF cultured with T lymphocytes isolated from two healthy donors; Fig. 7C, left histograms, black columns:mean ± SEM of four CRC-derived TAF:T co-cultures). Again, this Vδ2 T cell population was mainly EM (Fig. 7C, right histograms, black columns) and could be activated in re-directed killing assay by the anti-T cell receptor Vδ2 mAb and by the anti-CD3 mAb, but not by anti-CD8+ or an unrelated, isotype-matched mAb (Fig. 7D, black columns). Also, effector γδ T lymphocytes were able to kill CRC cells with higher efficiency, and lower E:T ratios, when target cells were exposed to Zol (Fig. 7E, left histograms, black vs. white columns). Also, we found that two epithelial cell lines (CRC15–045 and CRC13–011) obtained as primary cultures from two CRC, expressed BTN3A1 (Fig. 7A shows CRC15–045; note the presence of cytokeratin and absence of vimentin in the cell lysate). Once treated with Zol, both CRC15–045 and CRC13–011 cells were able to stimulate the expansion of EM Vδ2 T lymphocytes (Fig. 7B, right panels: two representative experiments with CRC15–045 and T lymphocytes isolated from two healthy donors; Fig. 7C, left and right histograms, gray columns: mean ± SEM, n = 2 epithelial cell lines with two T cell donors). This Vδ2 T cell population could be activated by anti-Vδ2 (BB3) and anti-CD3 (UCHT1) mAb (Fig. 7D, gray columns: mean ± SEM, n = 2 epithelial cell lines with two T cell donors) and kill the CRC cell line CaCo2 (Fig. 7E, right histograms, gray columns) and HCT15 (not shown). Thus, in the presence of Zol, both TAF- and tissue-derived CRC can induce the expansion of Vδ2 effector T cells with antitumor cytotoxic activity. It is of note that in TAF BTN3A1 is mainly localized in the membrane- and cytoskeleton-enriched fractions, and this is more evident upon Zol exposure (Fig. 7F, M vs. Ck).

Figure 7.

Differentiation of effector memory antitumor Vδ2 T cells induced by tumor-associated fibroblast (TAF) and tumor-derived CRC primary cultures. (A) Immunoblot of cell lysates obtained from three TAF (TAF16–020, TAF16–027 and TAF16–030) or the CRC15–045 epithelial cell primary culture, with polyclonal anti-BTN3A1 antiserum, anti-cytokeratin and anti-vimentin mAbs. β-actin is shown as a loading control. (B) Peripheral blood T lymphocytes were co-cultured with TAF (left plots: T cells from donor 1 and donor 2 upon culture on TAF16–020) or CRC15–045 epithelial cell culture (right plots, T cells from donor 1 and donor 2), pre-treated with Zol (5 µM) or not (Nil) for 20 d and double stained with PE-anti-CD3 and APC-anti-Vδ2mAbs. The percentage of Vδ2 T cells is reported in the upper right quadrant of each plot. (C) Left histogram: percentage of Vδ2 T cells obtained from 20 d of co-culture with untreated or Zol-treated TAF (black) or untreated or Zol-treated CRC15–045 and CRC13–011 epithelial cells (gray). Mean ± SEM (n = 8 experiments performed with two T lymphocyte donors and four TAF; n = 4 experiments with two T lymphocyte donors and the two CRC epithelial cells). Right histograms: percentage of effector memory (EM, CD45RA−CD27−), terminal-differentiated effector memory (TEMRA,CD45RA+-CD27−), naive (N, CD45RA+CD27+) or central memory (CM,CD45RA−CD27+) cells among Vδ2 cells from T lymphocytes immediately after separation (white bars) or on day 20 of co-culture with Zol-treated TAF cells (black bars) or CRC15–045 and CRC13–011 epithelial cells (gray bars). Mean ± SEM as above. ***p <0.001 or **p <0.01 or *p <0.05 vs. T lymphocytes after separation (white bars). (D, E) Vδ2 T cells obtained from T lymphocytes after 20 d of co-culture with Zol-treated TAF or CRC epithelial cells were used in re-directed killing assay against the P815 cell line in the presence of anti-CD8, anti-Vδ2, anti-CD3 mAbs or an unrelated mAb matched for the isotype as a control (CTR) at the E:T ratio of 5:1 (D: black columns: Vδ2 T cells from TAF co-cultures; gray columns: Vδ2 cells from CRC epithelial cell co-cultures), or in a 4 h 51Cr release cytolytic assay (E, left histogram, black columns: Vδ2 T cells from TAF co-cultures; right histogram, gray columns: Vδ2 cells from CRC epithelial cell co-cultures), against untreated (white columns) or Zol-treated (black or gray columns) CaCo2 cell line at the E:T ratio of 10:1, 5:1 and 2:1. Results are expressed as percentage specific lysis calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Mean ± SD from four experiments (left histogram) or two experiments (right histogram), ***p <0.001 or **p <0.01 Zol-treated vs. untreated CaCo2 cell line. (F) BTN3A1 localization in subcellular fractions (Cyt: cytosolic fraction, M: membrane-enriched fraction, N: nuclear fraction, Ck: cytoskeleton-enriched fraction) obtained with the Qproteome cell compartment kit from untreated or Zol-treated TAF16–027 (TAF2 in panel A). Vimentin was used as marker of the Ck fraction and GAPDH for the Cyt/M fractions.

Finally, Vδ2 effector T cells showing antitumor activity can be derived from tumor cell suspensions also using monocytes, isolated from peripheral blood of healthy donors (we could not obtain enough monocytes from CRC cell suspensions), in the presence of Zol (Fig. S2A: two representative experiments; Fig. S2B: mean ± SD of five monocyte: CRC cultures, left histograms: percentage of Vδ2 T cells; right histograms: fold increase vs. the beginning of culture). The cytolytic activity was stimulated by anti-Vδ2 and anti-CD3 mAbs as re-directed killing assay (Fig. S2C) or was detected using CRC cells (Fig. S2D, HCT15: left histogram, CaCo2: right histogram). All these data would indicate that Zol can enable different cell types present in the CRC microenvironment (cancer cells, TAF and monocytes) to induce the expansion of antitumor effector γδ T lymphocytes.

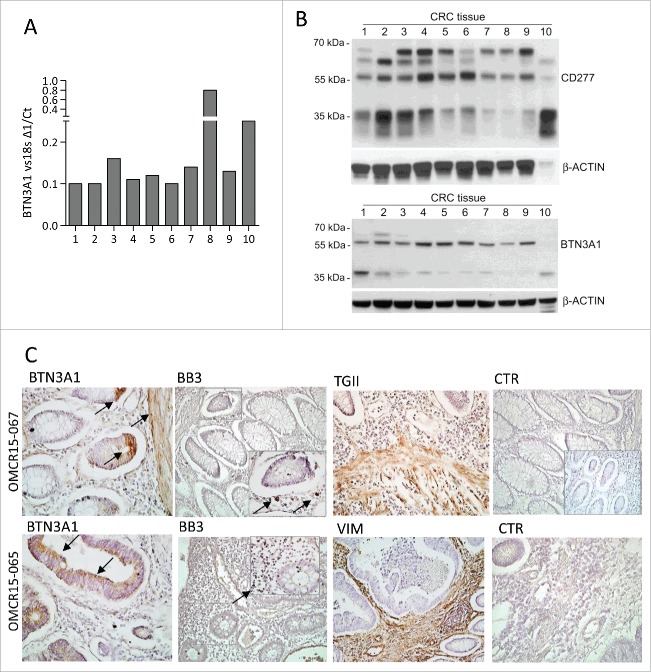

To confirm that Zol can work in vivo, we checked the expression of BTN3A1 at the tumor site. As shown in Fig. 8, BTN3A1 could be detected by PCR in CRC specimens (Fig. 8A, 10 CRC examined), and by western blot as protein in cell lysates obtained from the same CRC samples (Fig. 8B, BTN3A1 detected using either anti-CD277 mAb or anti-BTN3A1 antiserum). Immunohistochemistry (Fig. 8C, two representative cases out of 10 CRC) showed that BTN3A1 can be detected on either epithelial cells or TAF (transglutaminase, TGII or vimentin positive) in CRC, close to areas infiltrated by Vδ2T lymphocytes (recognized by the anti-Vδ2 mAb BB3).

Figure 8.

BTN3A1 expression in CRC tissue specimens. BTN3A1 expression was evaluated in CRC tissue sections by Q-RT-PCR (A), western blot (B) or immunohistochemistry (C). (A) RNA was extracted from tissue sections of 10 CRC specimens, reverse transcribed and Q-RT-PCR for BTN3A1 performed. Results are expressed as1/ΔCt normalized to 18s. (B) immunoblots of lysates obtained from the indicated CRC tissue specimens, as described in Materials and Methods, with the anti-CD277 mAb (upper blot) or with a rabbit polyclonal anti-BTN3A1 antiserum (lower blot). β-actin is shown as a loading control. (C) immunohistochemistry of two representative cases out of the 10 indicated in panels A and B, performed as described in Materials and Methods, with the indicated antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-BTN3A1 antiserum (arrows), anti-Vδ2 mAb (BB3, arrows in the inset), polyclonal rabbit anti-TGII antiserum, anti-vimentin mAb and a matched isotype-unrelated antibody as negative control (goat anti-rabbit antiserum in the inset of the upper CTR). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, coverslipped with Eukitt and analyzed under a Leica DM MB2 microscope with a charged-coupled device camera (Olympus DP70) at a 40× enlargement, as indicated.

Discussion

There is general agreement on the role of γδ T lymphocytes-infiltrating solid tumors, including CRC, in the anticancer surveillance,3-5,9,11 so that treatments focused on γδ T cell-mediated immune responses are now considered as an attractive and promising therapeutic approach in oncology.6-8,39,40 Stimulation of γδ T lymphocytes with PAg,3,6-11 through the engagement of the BTN3A1 molecule,25-31 leads to the generation of an efficient antitumor immune response. In particular, N-PBs that induce IPP accumulation, have been used in different clinical trials.21-24

In this paper, we show that (i) the N-BP Zol, besides sensitizing CRC cells to γδ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, stimulates the expansion of Vδ2 T cells with EM phenotype and antitumor cytotoxic activity; (ii) this effect is partially related to BTN3A1 expression and in particular by its cellular re-distribution; (iii) BTN3A1 is detected at the tumor site, both on epithelial and stromal cells, in the areas infiltrated by Vδ2 T lymphocytes; (iv) Zol is effective in stimulating antitumor effector Vδ2 T cells from ex-vivo CRC cell suspensions; and (v) both CRC cells and TAF can be primed by Zol to trigger Vδ2 T cells.

First, we found that different CRC cell lines exposed to Zol as a source of IPP, could successfully promote the expansion of γδ T lymphocytes able to kill both the stimulating tumor cells and other CRC cell lines. The phenotype of such lymphocyte population, that was mostly naive (co-expression of CD45RA and CD27) at the beginning of the co-culture, was that of EM cells, based on the lack of CD45RA and CD27 expression.35,36 Furthermore, Zol could sensitize CRC cell lines, including those that poorly triggered γδ T cell growth, to become targets for the cytotoxic effect exerted by activated γδ T lymphocytes. Given the heterogeneity of the stimulating ability displayed by the various CRC cell lines, we asked whether this was due to a different sensitivity of farnesyl diphosphate synthase to Zol, as reported.34 However, non-stimulating CRC cell lines were unable to trigger efficiently γδ T cell expansion, even when pre-treated with high doses of Zol; furthermore, IPP production in response to Zol, was lower in the three non-stimulating cell lines tested and they did not enhance IPP production in response to high doses of Zol, with the exception of DLD1. Thus, we further investigated any possible difference in the expression of proteins of the butyrophilin family, mainly BTN3A1 that is an essential molecule for the recognition of PAg by γδ T lymphocytes, due to its B30.2-binding domain.25-31

The amount of BTN3A1 mRNA evaluated by Q-RT-PCR analysis is heterogeneous in stimulating and in low-stimulating CRC cell lines (not shown); the expression of the protein assayed with the anti-CD277 mAb, recognizing the immunoglobulin-like extracellular domain, was not clearly detectable in the CRC cell lines, regardless of their ability to promote γδ T cell expansion. When BTN3A1 expression was assayed with an anti-BTN3A1 antiserum recognizing the cytoplasmic tail of the molecule, at least one of the two major reported bands for BTN3A17,32,33 was detected in most CRC cell lines, regardless of their stimulating efficiency. This could explain the finding that also low-stimulating CRC, once treaded with Zol, can be killed by γδ T lymphocytes. On the other hand, overexpression of BTN3A1 obtained by transfection in two CRC cell lines (SW620 and DLD1) could only partially enhance their stimulating activity or their sensitivity to γδ T cell killing upon Zol treatment. It has to be noted that no significant differences in the transcription of the other members of BTN3A family, i.e., BTN3A2 and BTN3A3, was found in the different CRC cell lines (not shown); however, BTNL2, known to downregulate the effect of BTN3A1,37 was poorly expressed in most of the stimulating cell lines.

Based on these data, the role of BTN3A1 molecule does not appear to be directly related to the amount of protein expressed; rather, the different distribution of BTN3A1, in particular its cell membrane localization or cytoskeletal association, may be responsible for the activity of the molecule.32 It has been recently reported that a PAg-induced conformational change in BTN3A1 leads to its recognition by Vγ9Vδ2 TCR.33 In agreement with this finding, we found that Zol treatment induces a re-distribution of BTN3A1 in TAF and, to a lesser extent in CRC cells, increasing its binding to the cell membrane and to the cytoskeleton, thus explaining the efficiency in stimulating Vδ2 T cell expansion and effector function. Nevertheless, CRC cells should also display a functional farnesyl diphosphate synthase to produce IPP and deliver an efficient activating signal to γδ T lymphocytes.

An interesting observation is that Zol added to ex-vivo tumor-derived cell suspensions, containing epithelial cells, lymphocytes, TAF and monocytes, is effective in inducing the growth of γδ T cells showing cytolytic activity against CRC target cells. Thus, whatever the mechanism of BTN3A1 responsible for Zol-induced IPP accumulation, using this drug it is possible to induce the expansion of infiltrating γδ T cells with potential antitumor activity. Along this line, in the presence of Zol, both TAF and tissue-derived CRC cells can induce the expansion of Vδ2 effector T lymphocytes that can kill CRC cells, starting from a T cell population isolated from peripheral blood. Also, Vδ2 cytotoxic effector T cells can be derived from tumor cell suspensions using Zol-treated peripheral blood monocytes.

All these data indicate that Zol can enable different cell types present in the CRC microenvironment (cancer cells, TAF and monocytes) to induce the expansion of antitumor γδ T lymphocytes, so that N-BPs like Zol can conceivably be proposed in therapeutic schemes of CRC. Of note, BTN3A1 could be detected by PCR in CRC specimens and by western blot as protein in cell lysates obtained from the same CRC samples. Immunohistochemistry showed that BTN3A1 can be detected on either epithelial cells or TAF in CRC, close to areas infiltrated by Vδ2 T lymphocytes. This observation confirms that Zol can work as antitumor immune-stimulator in vivo; moreover, immunohistochemical analysis of BTN3A1 expression at the tumor site, together with the evaluation of BTNL2, can help to select potentially responders to Zol treatment among CRC patients.

Methods

CRC patients' tissue specimens

Tissue samples were obtained from 10 CRC patients undergoing therapeutic intervention at the Unit of Oncological Surgery, IRCCS-AOU San Martino-IST, Genoa, provided informed consent (the study was approved by the institutional and regional ethical committee, PR163REG2014). Samples were used for (i) preparation of cell suspensions for phenotypic and functional assays; (ii) RNA extraction for Q-RT-PCR; (iii) preparation of cell lysates for immunoblotting; and (iv) immunohistochemistry.

Isolation of CRC cell suspension, primary tumor-associated fibroblasts and epithelial cells

CRC specimens were minced by scissors, transferred into 15 mL conical tube and digested with 2 mg/mL collagenase type I and II (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Monza, Italy) for 90 min at 37°C. Residual tissue debris were removed by soft centrifugation (300 rpm, 1 min), cells were pelleted (1,800 rpm, 10 min) and passed through a 100-um cell strainer (Euroclone, Milan, Italy). Cell suspensions were then purified by density gradient centrifugation (Lympholyte, Cederlane, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) and phenotypically characterized (CD3, CD14, Vδ2, CD105, EPCAM) by flow cytometry (see below). A portion of cell suspension was plated in RPMI 1640 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma), after 16 h non-adherent cells were removed and adherent cells were switched to MEMα (Euroclone) complete medium to obtain TAF primary cultures; after two in vitro passages, cells were tested for CD105 and fibroblast activation protein (FAP) expression and vimentin content and four TAF (TAF16–020, TAF16–027, TAF16–030, TAF16–035) were frozen for further experiments. The CRC15–045 and CRC13–011 epithelial cell lines were derived from a stage IIA and a stage IVB (UICC 2009) CRC, respectively, showing a strong peri- and intra-tumoral infiltration of lymphocytes. After collagenase digestion, intact crypts collected from the pellet of residual tissue debris were plated in DMEM/F12 with Hepes buffer (Euroclone), containing B27 supplement, EGF 10 ng/mL and DTT 10 nM (Sigma). The primary cell cultures initially developed as organoids, which formed small, loosely-adherent colonies after the first trypsin digestion, expressing EPCAM (not shown) and cytokeratin.

Isolation of T cells and monocytes and co-cultures

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained after Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation of blood samples derived from healthy donors. Highly purified (> 98% pure as assessed by flow cytometry upon CD3 staining, see below) T cells were obtained from PBMC using the RosetteSep T cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Monocytes (Mo) were isolated from PBMC using the anti-CD14 mAb (MEM18, IgG1, Exbio, Prague, CZ) and EasySep custom Kit (StemCell Technologies, Inc.) according to manufacturer's instructions, with recovery of > 97% CD14 positive cells.36

The human CRC cell lines HT29, HCT15, HCT116, SW48, SW480, SW620, Colo741, Colo205, Colo320, CaCo2, LS180, WiDr, LoVo and DLD1 were obtained from the Biological Bank and Cell Factory of the IRCCS AOU San Martino IST (Genoa, Italy) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% L-glutamine (Gibco). T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 complete medium with or without irradiated CRC cells or TAF, or CRC15–045 cell line, at a ratio of 1:10, or Mo (Mo:T ratios from 1:10 to 1:80), untreated or exposed for 24 h to zoledronic acid (Zol 5 µM, kindly provided as sodium salt by Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland, MTA 37318); the dose was selected on the basis of the effectiveness on γδ T cells proliferation from PBMCs cultures and absence of toxic effects according to the literature and our previous data.39-41 In some experiments, the CRC cell lines LS180, DLD1, HCT15 and SW620 were pre-treated for 4 h with 100 µM or 50 µM Zol, then washed and used for stimulation experiments.34 In other experiments, 5 µM Zol was added to the cell suspensions obtained from CRC patients' specimens. On the third day, IL-2 (4 ng/mL) was added and every 2 d complete medium supplemented with IL-2 was changed. T cells were recovered at 14 (not shown) or 20 d and Vδ2 T cell expansion was assessed by FACS analysis using the anti-γδ mAb BB3 (see below).

Immunofluorescence and cytofluorimetric analyses

Immunofluorescence was performed as described.36 For the identification of γδ T cell subpopulations, we used the anti-γδ mAb BB3 (IgG1).36 BTN3A1 expression was checked with the anti-CD277 mAb (clone 20.1, IgG1, Affimetrix eBioscience, Hatfield, UK). Tissue-derived or cultured cell populations were also characterized with the anti-CD27 or the anti-CD45 mAb, purchased from BD Biosciences Europe (Milan, Italy), the anti-CD14 mAb (MEM18, IgG1), the anti-CD3 mAb (UCHT-1, IgG1, Ancell, Bayport, MN55003, USA), the anti-CD105 (from the producing hybridoma purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), the anti-EPCAM mAb (ab98003, IgG1, Abcam, MA, USA) or the anti-FAP mAb (F11–24, IgG1, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Negative controls were stained with APC-labeled isotype-matched irrelevant mAbs. Samples were analyzed by CyAn ADP flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA), gated on viable cells and/or on lymphocytes (based on FSC and SSC parameters). Results are expressed as log of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, arbitrary units, a.u.) or percentage of positive cells.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytolytic activity of γδ T cells was analyzed against the various CRC cell lines at an E:T ratio of 10:1 to 2.5:1, in V-bottomed microwells, in a 4-h 51Cr-release assay as described.15,16 Some samples were set up after exposure of the target cell lines to Zol at 5 µM concentration for 24 h. In some samples, the effector cells were exposed to saturating amounts (5 µg/mL) of the anti-Vδ2 mAb at the onset of the cytotoxicity assay; an unrelated mAb, matched for the isotype (BD PharMingen, BD Italia, Milan, Italy), was used as control. Other experiments were performed using as target cells the BTN3A1-transfected SW620 or DLD1 cell lines (see below), either untreated or Zol-treated. Reverse cytotoxicity was performed using the anti-CD3 or the anti-Vδ2 or the anti-CD8 (Leu2a, IgG1, BD PharMingen) mAbs, all at 2 µg/mL, and the FcγR positive murine P815 cell line. 100 µL of SN were measured in a γ-counter and the percentage of 51Cr-specific release was calculated as: experimental release (counts) - spontaneous release (counts)/maximum release (counts) - spontaneous release (counts). Maximum and spontaneous release were calculated as described.36

cDNA reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR)

RNA was extracted either from cultured CRC cell lines or CRC tissue samples or cell suspensions. Paraffin-embedded sections (8-μm thick) of the CRC patients were fixed on PEN membrane glass slides (MDS Analytical Technologies GmbH, Ismaning, Germany), dried at room temperature under a chemical safety hood for 5 min, dipped in xylene for 10 min twice for each sample, followed by a 3-step immersion in 100%/95%/75% ethanol solution. After washing in DEPC RNAse-free water and staining (HistogeneActurus Italia srl, Milan, Italy), samples were dipped in 75%/95%/100% ethanol solution for 30 sec each passage followed by xylene for 5 min. Tissue sections were then dried at room temperature. RNA was extracted with the Paradise TM Reagent System (Acturus Bioscience) after incubation with proteinase K for 4 to 6 h at 56°C. A DNAse treatment step was included. RNA was diluted in 50-μL elution buffer, according to the manufacturer's protocol and quantitated by NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (ND-1000 Celbio, Euroclone) and by Qubit TM fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies Italia, Monza, Italy) using the Quant-it TM Assay Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was performed with random hexamers by the use of the High Capacity Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). To verify quantitative RT-PCR efficiency, decreasing amounts (50 ng, 10 ng and 0.1 ng) of normal RNA were used for CT titration. For CRC cell lines, RNA was extracted with TriPure (Roche diagnostic, Milan, Italy). cDNA synthesis was performed with random primers. Primers and probes for BTN3A1 and BTNL2, were purchased by Applied Biosystem (Life Technologies Europe, Monza, Italy). Quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR) was performed on the 7900HT FastRT-PCR system (Applied Biosystem) with the fluorescent Taqman method and normalized to 18s (Applied Biosystem). After subtracting the threshold cycle (CT) value for 18s from the CT values of target genes, results were expressed as 2−ΔΔCT or ΔCT ratio vs. 18s.42

BTN3A1 transfection and western blot

The pLX304-BTN3A1 plasmid (HsCD00443486, DNASU, Arizona State University) was used to overexpress BTN3A1 protein. DLD1 or SW620 cells were transfected in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Gibco, Life Technology) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Life Technology) following the manufacturer's instructions. Protein expression by western blot was analyzed from day 2 up to day 7 after transfection.42 CRC cell lines were harvested and lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. CRC tissues frozen at −80°C in 80-µL RIPA buffer (with 1mM OV, 1mM DTT and 1:100 protease inhibitors cocktail, Sigma, P8340) were thawed on ice and minced with sharp scissors adding 100 µL of fresh RIPA buffer to each sample. After 90 min incubation on ice, samples were potterized and centrifuged (16,000 rpm, 4°C; Eppendorf 5417-R centrifuge). Supernatants were collected and protein content quantified by the DC protein assay (BioRad Italia, Milan, Italy). Equal amounts of protein (35 µg/lane) were loaded under reducing or non-reducing conditions on precast 8–16% gradient gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and then transferred to PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). After blocking, membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with the mouse monoclonal anti-CD277 (BT3.1, 20.1, Affymetrix eBioscience, recognizing the Ig-like domain of the molecule) or the rabbit polyclonal anti-BTN3A1 (NBP1–90750, Novus Biologicals, recognizing the C-terminal domain partially shared by BTN3A1 and BTN3A3) diluted according to the manufacturer's instructions. Some samples were probed with an anti-epithelial keratin 8/18 (IgG1, Cell Signaling Technology, EuroClone, Milan, Italy) or an anti-vimentin (clone V9, IgG1, Sigma) mAb. Subcellular fractionation was performed with the Q proteome cell compartment kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy).32 Enrichment of marker proteins in subcellular fractions was probed with the following antibodies: lamin B (Cell Signaling Technology), GAPDH-HRP (Novus Biologicals), β-tubulin (Tub2.1, Sigma) and vimentin (clone V9, Sigma). After washing, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the relevant horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology,), and proteins were detected by Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Anti-β-actin HRP-conjugated antibody (Cell Signaling) was used as a loading control.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded samples from 10 CRC patients were analyzed for the expression in situ of BTN3A1, Vδ2, vimentin and TGII. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 6-μm-thin sections, deparaffinized in xylene, and treated with Peroxoblok (Novex, Life Technologies) to quench endogenous peroxidase, followed by Ultra Blok reagent (Ultravision Detection System, Thermo Scientific BioOptica, Milan Italy). The following antibodies were added: polyclonal rabbit anti-BTN3A1 antiserum (1:100, Novus Biologicals), anti-Vδ2 mAb (BB3, 2 µg/mL), anti-CD14 mAb (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-vimentin clone V9 (1:200, Sigma), polyclonal rabbit anti-TGII antiserum (1:100, Thermo Scientific) and an isotypic-unrelated antibody was used as negative control (Dako Cytomation). Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse antiserum (BioOptica) was then added, followed by HRP-conjugated avidin (Thermo Scientific) and the reaction developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogen. Then, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, coverslipped with Eukitt (Bio Optica), and analyzed under a Leica DM MB2 microscope equipped with a charged coupled device camera (Olympus DP70 with a 20× or 40× objective).

HPLC negative ion electrospray ionization TOF-MS

IPP production by the CRC cell lines SW620, LS180, DLD1, HCT15 and Colo320, either untreated or exposed to Zol, either as continuous treatment with 5 µM for 24 h, or as pulse treatment of 50 µM and 100 µM for 4 h, as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods, was performed according to Jauhiainen et al.38 with modifications, as detailed in supporting information (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

The amount of IPP/DMAPP, expressed as pmol/mg protein, was evaluated by calculating the peak area of the extracted ion current (EIC m/z 244.99[M-H]−), referred to a standard curve of IPP (range 0.1–15 μM) in control cell extracts. Total protein content was determined with the DC Protein Assay (BioRad). Data are shown as IPP pmol/mg of total pmol extracted by ACN/total protein content in cell lysates after ACN extraction.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student's t test. The cut-off value of significance as indicated in legend to figure, was set at p <0.05 (*), p <0.01 (**), p <0.001 (***).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Luca Damonte and Dr Annalisa Salis (DIMES and CEBR, University of Genoa) for help in performing MS/MS experiments.

Funding

This study was supported by research funding from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC2014, IG-15483) to AP, AIRC2015 (IG-17074) to MRZ, by the Istituto San Paolo to RB (SIME2012–0312), 5×1000 2012 and 5×1000 2013 MIUR to AP. RV and DC are recipient of a fellowship funded on the AIRC2014 (IG-15483) grant.

References

- 1.Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cells and the lymphoid stress-surveillance response. Immunity 2009; 31(2):184-96; PMID:19699170; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonneville M, O'Brien RL, Born WK. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: a blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10(7):467-78; PMID:20539306; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poggi A, Zocchi MR. γδ T lymphocytes as a first line of immune defense: Old and new ways of antigen recognition and implications for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2014; 5:575; PMID:25426121; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00575 eCollection 2014; http://www.jem.org/cgi/doi/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gober HJ, Kistowska M, Angman L, Jenö P, Mori L, De Libero G. Human T cell receptor gammadelta cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J Exp Med 2003; 197(2):163-8; PMID:12538656; http://www.jem.org/cgi/doi/ 10.1084/jem.20021500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Sarikonda G, Puan KJ, Tanaka Y, Feng J, Giner JL, Cao R, Mönkkönen J, Oldfield E, Morita CT. Indirect stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells through alterations in isoprenoid metabolism. J Immunol 2011; 187(10):5099-113; PMID:22013129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1002697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabelitz D, Kalyan S, Oberg HH, Wesch D. Human Vδ2 versus non-Vδ2 γδ T cells in anti-tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2(3):e23304; PMID:23802074; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.23304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corvaisier M, Moreau-Aubry A, Diez E, Bennouna J, Scotet E, Bonneville M, Jotereau F. Vgamma9 Vdelta2 T cell response to colon carcinoma cells. J Immunol 2005; 175(8):5481-8; PMID:16210656; http://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat J, Kabelitz D. γδT cells and epigenetic drugs: A useful merger in cancer immunotherapy? Oncoimmunology 2015; 4(6):e1006088. eCollection 2015 Jun; PMID:26155411; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1006088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka Y, Kobayashi H, Terasaki T, Toma H, Aruga A, Uchiyama T, Mizutani K, Mikami B, Morita CT, Minato N. Synthesis of pyrophosphate-containing compounds that stimulate Vgamma2 Vdekta2 T cells: application to cancer immunotherapy. Med Chem 2007; 3(1):85-99; PMID:17266628; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/157340607779317544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burjanadzé M, Condomines M, Reme T, Quittet P, Latry P, Lugagne C, Romagne F, Morel Y, Rossi JF, Klein B et al.. In vitro expansion of gammadelta T cells with anti-myeloma cells activity by Phosphostim and IL-2 in patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2007; 139(2):206-16; PMID:17897296; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennouna J, Levy V, Sicard H, Senellart H, Audrain M, Hiret S, Rolland F, Bruzzoni-Giovanelli H, Rimbert M, Galéa C et al.. Phase I study of bromohydrinpyrophosphate (BrHPP, IPH 1101) a Vgamma9 Vdelta2 T lymphocyte agonist in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010; 59(10):1521-30; PMID:20563721; http://dx.doi.org/20483742 10.1007/s00262-010-0879-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capietto AH, Martinet L, Cendron D, Fruchon S, Pont F, Fournié JJ. Phophoantigens overcome human TCRVgamma9+ gammadelta T cell immunosuppression by TGF-beta: relevance for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol 2010; 184(12):6680-7; PMID:20483742; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1000681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell RG. Bisphosphonates: the first 40 years. Bone 2011; 49(1):2-19; PMID:21555003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bone.2011.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das H, Wang L, Kamath A, Bukowski JF. Vgamma2Vdelta2 T-cell receptor-mediated recognition of aminobisphosphonates. Blood 2001; 98(5):1616-8; PMID:11520816; http://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood.V98.5.1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Feurle J, Weissinger F, Tony HP, Wilhelm M. Stimulation of gammadelta T cells by aminobisphosphonates and induction of antiplasmacell activity in multiple myeloma. Blood 2000; 96(2):384-92; PMID:10887096 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieli F, Gebbia N, Poccia F, Caccamo N, Montesano C, Fulfaro F, Arcara C, Valerio MR, Meraviglia S, Di Sano C et al.. Induction of gammadelta T-lymphocyte effector functions by bisphosphonate zoledronic acid in cancer patients in vivo. Blood 2003; 102(6):2310-1; PMID:12959943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santini D, Vespasiani Gentilucci U, Vincenzi B, Picardi A, Vasaturo F, La Cesa A, Onori N, Scarpa S, Tonini G. The antineoplastic role of bisphosphonates: from basic research to clinical evidence. Ann Oncol 2003; 14(10):1468-76; PMID:14504045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clézardin P, Fournier P, Boissier S, Peyruchaud O. In vitro and in vivo anti-tumor effects of bisphopshonates. Curr Med Chem 2003; 10(2):173-80; PMID:12570716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/0929867033368529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Märten A, Lilienfeld-Toal MV, Büchler MW, Schmidt J. Zoledronic acid has direct antiproliferative and antimetastatic effect on pancreatic carcinoma cells and acts as an antigen for delta2 gamma/delta T cells. J Immunother 2007; 30(4):370-7; PMID:17457212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31802bff16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todaro M, D'Asaro M, Caccamo N, Iovino F, Francipane MG, Meraviglia S, Orlando V, La Mendola C, Gulotta G, Salerno A et al.. Efficient killing of human colon cancer stem cells by gammadelta T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2009; 182(11):7287-96; PMID:19454726; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0804288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang JM, Kaikobad MR, Wallace M, Staab MJ, Horvath DL, Wilding G, Liu G, Eickhoff JC, McNeel DG, Malkovsky M. Pilot trial of interleukin-2 and zoledronic acid to augment γδ T cells as treatment for patients with refractory renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2011; 60(10):1447-60; PMID:21647691; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-011-1049-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakamoto M, Nakajima J, Murakawa T, Fukami T, Yoshida Y, Murayama T, Takamoto S, Matsushita H, Kakimi K. Adoptive immunotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer using zoledronate-expanded γδT cells: a phase I clinical study. J Immunother 2011; 34(2):202-11; PMID:21304399; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318207ecfb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meraviglia S, Eberl M, Vermijlen D, Todaro M, Buccheri S, Cicero G, La Mendola C, Guggino G, D'Asaro M, Orlando V et al.. In vivo manipulation of Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells with zoledronate and low-dose interleukin-2 for immunotherapy of advanced breast cancer patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 161(2):290-7; PMID:20491785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieli F, Vermijlen D, Fulfaro F, Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, Cicero G, Roberts A, Buccheri S, D'Asaro M, Gebbia N et al.. Targeting human gammadelta T cells with zoledronate and interleukin-2 for immunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2007; 67(15):7450-7; PMID:17671215; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harly C, Guillaume Y, Nedellec S, Peigné CM, Mönkkönen H, Mönkkönen J, Li J, Kuball J, Adams EJ, Netzer S et al.. Key implication of CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A) in cellular stress sensing by a major human γδ T-cell subset. Blood 2012; 120(11):2269-79; PMID:22767497; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palakodeti A, Sandstrom A, Sundaresan L, Harly C, Nedellec S, Olive D, Scotet E, Bonneville M, Adams EJ. The molecular basis for modulation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses by CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A)-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(39):32780-90; PMID:22846996; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.384354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnett HA, Viney JL. Immune modulation by butyrophilins. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14(8):559-69; PMID:25060581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri3715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabelitz D. Critical role of butyrophilin 3A1 in presenting prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human γδT cells. Cell Mol Immunol 2014; 11(2):117-9; PMID:24097034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cmi.2013.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vavassori S, Kumar A, Wan GS, Ramanjaneyulu GS, Cavallari M, El Daker S, Beddoe T, Theodossis A, Williams NK, Gostick E et al.. Butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphorylated antigens and stimulates human γδ T cells. Nat Immunol 2013; 14(9):908-16; PMID:23872678; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Henry O, Distefano MD, Wang YC, Räikkönen J, Mönkkönen J, Tanaka Y, Morita CT. Butyrophilin 3A1 plays an essential role in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. J Immunol 2013; 191(3):1029-42; PMID:23833237; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1300658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandstrom A, Peigné CM, Léger A, Crooks JE, Konczak F, Gesnel MC, Breathnach R, Bonneville M, Scotet E, Adams EJ. The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Immunity 2014; 40(4):490-500; PMID:24703779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhodes DA, Chen H-C, Price AJ, Keeble AH, Davey MS, James LC, Eberl M, Trowsdale J. Activation of human γδT cells by cytosolic interactions of BTN3A1 with soluble phosphoantigens and the cytoskeletal adaptor periplakin. J Immunol 2015:194(5):2390-2398; PMID:25637025; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/Jimmunol.1401064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebestyen Z, Scheper W, Vyborova A, Gu S, Rychnavska Z, Schiffler M, Cleven A, Chéneau C, van Noorden M, Peigné CM et al.. RhoB mediates phosphoantigen recognition by Vγ9Vδ2 T cell receptor. Cell Rep 2016; 15(9):1973-85; PMID:27210746; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep2016.04.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idrees ASM, Sugie T, Inoue C, Murata-Hirai K, Okamura H,Morita CT, Minato M, Toi M, Tanaka Y. Comparison of γδ T cell responsesand farnesyl diphosphate synthase inhibition in tunor cells pretreated with zoledronic acid. Cancer Sci 2013; 104(5):536-542; PMID:23387443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/cas.12124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dieli F, Poccia F, Lipp M, Sireci G, Caccamo N, Di Sano C, Salerno A. Differentiation of effector/memory Vdelta2 T cells and migratory routes in lymph nodes or inflammatory sites. J ExpMed 2003; 198(3):391-397; PMID:12900516; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20030235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musso A, Catellani S, Canevali P, Tavella S, Venè R, Boero S, Pierri I, Gobbi M, Kunkl A, Ravetti JL et al.. Aminobisphosphonate prevent the inhibitory effect exerted by lymph node stromal cells on anti-tumor Vδ2 T lymphocytes in non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Haematologica 2014; 99(1):131-9; PMID:24162786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3324/haematol.2013.097311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnett HA, Escobar SS, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Budelsky AL, Steffen LA, Boiani N, Zhang M, Siu G, Brewer AW, Viney JL. BTNL2, a butyrophilin/B7-like molecule, is a negative costimulatory molecule modulated in intestinal inflammation. J. Immunol 2007; 178(3):1523-33; PMID:17237401; http://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jauhiainen M, Monkkonen H, Raikkonen J, Monkkonen J, Auriola S. Analysis of endogenous ATP analogs and mevalonate pathway mebolites in cancer cell cultures using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009; 877(27):2967-75; PMID:19665949; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouet-Toussaint F, Cabillic F, Toutirais O, Le Gallo M, Thomas de la Pintière C, Genetet N, Meunier B, Dupont-Bierre E, Boudjema K et al.. Vγ9Vδ2 T cell-mediated recognition of human solid tumor. Potential for immunotherapy of hepatocellular and colorectal carcinomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2008; 57(4):531.539; PMID:17764010; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-007-0391-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musso A, Zocchi MR, Poggi A. Relevance of the mevalonate biosynthetic pathway in the regulation of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated effects on T-cell proliferation and B-cell survival. Haematologica 2011; 96(1):16-23; PMID:20884711; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3324/haematol.2010.031633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiore F, Castella B, Nuschak B, Bertieri R, Mariani S, Bruno B, Pantaleoni F, Foglietta M, Boccadoro M, Massaia M. Enhanced ability of dendritic cells to stimulate innate and adaptive immunity on short-term incubation with zoledronic acid. Blood 2007; 110(3):921-7; PMID:17403919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zocchi MR, Camodeca C, Nuti E, Rossello A, Venè R, Tosetti F, Dapino I, Costa D, Musso A, Poggi A. ADAM10 new selective inhibitors reduce NKG2D ligand release sensitizing Hodgkin lymphoma cells to NKG2D-mediated killing. Oncoimmunol 2016; 5:5, e1123367; PMID:27467923; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1123367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.