Abstract

Background and purpose

Fast-track protocols have been introduced worldwide to improve the recovery after total hip arthroplasty (THA). These protocols have reduced the length of hospital stay (LOS), and THA in an outpatient setting is also feasible. However, less is known regarding the first weeks after THA with fast track. We examined patients’ experiences of the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge following inpatient and outpatient THA with fast track.

Patients and methods

In a prospective cohort study, 100 consecutive patients who underwent THA surgery in a fast-track setting between February 2015 and October 2015 received a diary for 6 weeks. This diary contained various internationally validated questionnaires including HOOS-PS, OHS, EQ-5D, SF-12, and ICOAP. In addition, there were general questions regarding pain, the wound, physiotherapy, and thrombosis prophylaxis injections.

Results

94 patients completed the diary, 42 of whom were operated in an outpatient setting. Pain and use of pain medication had gradually decreased during the 6 weeks. Function and quality of life gradually improved. After 6 weeks, 91% of all patients reported better functioning and less pain than preoperatively.

Interpretation

Fast track improves early functional outcome, and the PROMs reported during the first 6 weeks in this study showed continued improvement. They can be used as a baseline for future studies. The PROMs reported could also serve as a guide for staff and patients alike to modify expectations and therefore possibly improve patient satisfaction.

Historically, the length of hospital stay (LOS) after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) was several weeks (Berger et al. 2009) and mostly consisted of bed rest during hospitalization. During the last decade, there has been a continued worldwide interest in implementation of fast-track protocols for THA (Dowsey et al. 1999, Husted et al. 2008, Barbieri et al. 2009, Berger et al. 2009, Husted et al. 2011, 2012).

Fast-track protocols appear to be safe for all patients, including the elderly (Jorgensen and Kehlet 2013). The introduction of such protocols did not result in an increase in complications, re-admissions, or reoperations after primary THA (Dowsey et al. 1999, Barbieri et al. 2009, den Hartog et al. 2013, Stambough et al. 2015). Furthermore, various studies have shown that apart from the LOS, these protocols also reduce the length of rehabilitation after primary THA (Dowsey et al. 1999, Husted et al. 2008, Barbieri et al. 2009, Berger et al. 2009, Husted et al. 2011, 2012). Currently, THA in an outpatient setting is feasible for selected patients (Berger et al. 2009, Aynardi et al. 2014, Hartog et al. 2015). Up to 3 months postoperatively, no increase in procedure-specific complications or re-admissions has been described (Berger et al. 2009, Hartog et al. 2015).

However, most studies of THA in a fast-track setting have focused on optimizing the hospital stay or on evaluation of functioning of patients 6 weeks after surgery. To our knowledge, less is known regarding the recovery during the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge. We examined how patients experience the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge following inpatient or outpatient THA surgery in a fast-track setting.

Patients and methods

Patients

This prospective cohort study involved 100 consecutive patients who underwent primary THA, operated through the anterior supine intermuscular (ASI) approach at the Reinier de Graaf hospital, Delft, the Netherlands. Exclusion criteria were an insufficient command of the Dutch language, being mentally disabled, and having a prosthesis in another joint of the ipsilateral or contralateral lower limb placed within 6 months before THA surgery. All patients were operated by 1 orthopedic surgeon (SV).

The fast-track protocol of our institution was used for all patients (Table 1, see Supplementary data). The discharge criteria were functional and patients were evaluated by a physiotherapist and a nurse. The patient had to be able to walk 30 meters with crutches or rollator (a walking frame with wheels), to climb stairs (if able to walk with crutches), to dress independently, and to go to the toilet independently. Moreover, adequate pain relief had to have been achieved by means of oral medication before discharge, with a numeric rating scale (NRS, 0–10) score for pain of below 3 at rest and below 5 during mobilization. Furthermore, the wound had to be dry or almost dry, and the patient should not be experiencing any dizziness or nausea.

Measurements

Preoperatively, all the patients included were asked to complete a NRS pain score, the hip injury and osteoarthritis outcome score physical function short form (HOOS-PS), the Oxford hip score (OHS), and the EuroQol quality of life (EQ-5D) digitally. At discharge, all patients received a diary with specific questionnaires that had to be completed each day, over 6 weeks. The diary contained the following questionnaires: HOOS-PS, OHS, EQ-5D, the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12), and the intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain score (ICOAP).

The HOOS-PS score ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 representing no difficulty in physical functioning (Davis et al. 2008). The OHS score ranges from 0 to 48, where 48 is the best function and lowest pain score (Dawson et al. 1996). The EQ-5D score ranges from −0.333 to 1,000, with 1,000 meaning full health (Lamers et al. 2005). The SF-12 provides a physical component subscale (PCS) and a mental component subscale (MCS). The score ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates the lowest level of health measured and 100 indicates the highest level of health (Ware et al. 1996). The ICOAP score ranges from 0 to 44, where 0 is the best function and lowest pain score (Maillefert et al. 2009). The NRS for pain was scored every day, and represented the mean pain score for that day.

Moreover, general questions regarding pain, sleep, and the wound were answered on a daily basis in the diary. General questions regarding physiotherapy, satisfaction, and thrombosis injections were answered each week (Table 2, see Supplementary data). These questions were based on the outcome of 2 focus group meetings, which were organized before this present study (van Egmond et al. 2015b). Patients started to complete their diary on the day of discharge.

The LOS was measured from the number of nights that patients stayed in the hospital. At discharge, all patients received a prescription for 2 weeks of celecoxib (200 mg, once a day), which could be used in addition to paracetamol (1 g, 4 times a day). If necessary, supplementary pain medication such as tramadol (50 mg) or oxycodone (5 mg) was prescribed.

During the study, each patient was called by phone every week to check whether he or she had problems in completing the questions in the diary. After 6 weeks, the patients visited the outpatient clinic and returned their completed diary.

Statistics

No sample size calculation was done, since this was an observational pilot study. Missing data were handled according to the rules of the specific questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the results. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses with an exchangeable correlation structure were applied to study the changes in pain, quality of life, and function scores over time with the score during week 6 or day 42 as reference. IBM SPSS version 21 was used for statistical analysis. Any p-value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

The study protocol was assessed by the regional Medical Ethical Committee and no ethical approval was necessary, since the study did not fall under the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. However, all the patients who were included gave their written informed consent.

Results

Between February 2015 and October 2015, 144 patients were eligible for inclusion and 101 of them were included. 6 patients were excluded because of comorbidity: 1 patient was visually impaired and 5 patients were mentally disabled. 1 patient was excluded due to an insufficient command of Dutch, 7 were excluded for logistic reasons, and 29 patients declined participation for various reasons.

During the study, 7 patients were excluded from analysis and were considered to be lost to follow-up. 3 of these patients did not complete the diary correctly and more than half of the answers were missing. In addition, 1 patient developed a deep infection during the first 6 weeks after discharge, 1 patient had delirium, 1 patient lost the diary, and 1 patient was not a primary total hip arthroplasty.

1 patient received a cemented prosthesis, 4 patients received a hybrid prosthesis, and the remaining patients received an uncemented prosthesis (Taperloc Complete femoral prosthesis and a Hemispherical Ringloc Solid cup with a E-poly liner and a 32-mm head; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN).

The mean age of the remaining 94 patients was 65 (41–82) years, and 56 patients were female. Mean BMI was 26 (18–39). 42 patients were operated in an outpatient setting. The median LOS of the remaining patients was 1 (1–7) night. 2 patients stayed 3 and 4 nights, since the discharge criteria were not fulfilled. 1 patient stayed 3 nights due to atrial fibrillation. 1 patient stayed 7 nights because of liquor leakage, and received a blood patch on day 3. No other complications were registered during the patients’ stay in hospital. 3 patients were not discharged to their own home. 1 patient went to family for further recovery and 2 patients were discharged to a hotel with care facilities.

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 3. The inpatient and outpatient groups were statistically significantly different regarding age and ASA classification, so these groups could not be compared.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| Total | Outpatient | Inpatient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 94) |

(n = 42) |

(n = 52) |

p-value |

|

| Mean age, years | 65 (41–82) | 61 (41–78) | 68 (48–82) | < 0.001 |

| Female, n | 56 | 25 | 31 | 1.0 |

| BMIa | 26 (18–39) | 27 (20–35) | 26 (18–39) | 0.6 |

| ASA classification, n | 0.004 | |||

| I | 34 | 21 | 13 | |

| II | 55 | 21 | 34 | |

| III | 5 | – | 5 | |

| Right side, n | 50 | 21 | 29 | 0.6 |

| LOS, nightsa | 0.8 (0–7) | 0 | 1 (1–7) | < 0.001 |

| Discharge to home, n | 91 | 42 | 49 | 0.1 |

Since the data were not normally distributed, median (range) is given.

LOS: length of stay in hospital.

Pain

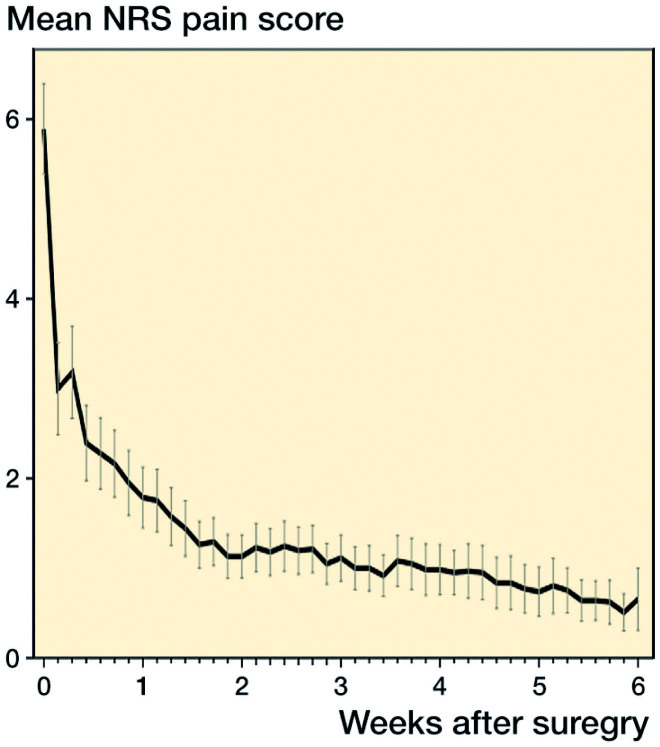

The median preoperative NRS pain score of all patients was 5 (0–10) at rest and 7 (1–10) during mobilization. The median average pain scores on day 1 and day 42 were 3 (0–9) and 0 (0–8), respectively. The NRS pain score gradually decreased over the first 6 weeks (Figure 1). GEE showed a statistically significant decrease from day 1 to day 32 (p < 0.05). The median ICOAP score gradually decreased from 9 (0–33) in the first week after discharge to 2 (0–30) in week 6 after discharge (Figure 2, see Supplementary data).

Figure 1.

Daily mean NRS pain score preoperatively to day 42 after discharge. Error bars show 95% CI.

Pain medication

During the first week, all 94 patients used paracetamol and 86 patients used celebrex. In addition to the paracetamol and celebrex, 7 patients used tramadol or oxycodon. The use of pain medication declined slowly over 6 weeks.

Wound care

11 patients reported wound leakage of blood or wound serum on the first day after discharge, which had decreased but persisted in 6 patients at the end of week 2. In 1 patient, the wound leaked serum over the first 6 weeks. None of these patients developed an infection. 2 patients described problems with the wound dressing because of fear and uncertainty in treating the wound correctly.

Anticoagulation

In all patients, low-molecular-weight heparin injections were prescribed once a day for a total of 4 weeks. These had to be injected into the subcutaneous abdominal fat. The patients’ resistance regarding the injections increased during the 4 weeks. 6 patients reported resistance during the first week, and this increased to 18 patients in the last week.

Complications

During hospital admission, 1 patient developed a liquor leakage and received a blood patch on postoperative day 3. 1 patient was discharged on day 1 after THA surgery and was re-admitted the same day because of fainting at home.

In the period between hospital discharge and the first outpatient check-up 6 weeks after surgery, 9 patients visited a doctor because of having health problems related to the THA. 7 patients visited the outpatient clinic for wound leakage or fear of wound infection. One of these patients developed a superficial wound infection. All cases were treated with watchful waiting. 2 patients visited their general practitioner because of fear of wound infection or because of vomiting as an adverse event with oxycodone; both of them were given medication. 2 patients had an extra wound control by a specialized nurse. 8 patients had a telephone consultations because of doubts about swelling of the operated leg, fear of infection, problems with sleeping, or recurrent pain.

Physiotherapy and walking

80 patients received physiotherapy during the first 6 weeks. The treatment modality of physiotherapy varied greatly between patients. The mean self-reported quality of walking increased from 6 in the first week to 8 in week 6, measured on a scale from 0 to 10. After 6 weeks, 60 of 89 patients were able to walk without any walking device. Figures 3 and 4 (see Supplementary data) show the reduction in use of walking devices indoors and out ofdoors in the first 6 weeks.

Functioning

Preoperatively, the median OHS score was 24 (6–42). The median OHS score gradually increased from 29 (12–46) during the first week after discharge to 43 (18–48) at week 6 (p < 0.05) (Figure 5, see Supplementary data). GEE showed a statistically significant increase from the first week, which persisted into week 6.

The median preoperative HOOS-PS score was 46.1 (8.8–100). The median HOOS-PS score 1 day after discharge was 34 (range 13–75). During the weeks that followed, median HOOS-PS gradually decreased until 5 weeks after discharge (p < 0.001). At the end of week 6, patients scored 16 (range 0–51) in the HOOS-PS (Figure 6, see Supplementary data).

Sleep

During the first 2 weeks, three-quarters of the patients reported that their sleep was good or reasonable. At week 6, over 95% of the patients had good or reasonable sleep.

Quality of life

The median SF-12 scores in the second week after discharge were 34 (20–57) on the PCS and 57 (34–71) on the MCS. At week 6, the median PCS score had increased to 41 (21–57) (p < 0.001). In contrast, the median MCS score did not increase significantly and was 59 (29–68) at week 6 (p = 0.07).

The median EQ-5D was 0.69 (−0.06 to 0.84) before surgery and decreased to 0.37 (−0.27 to 0.90) 1 day after discharge (p < 0.001). Over the weeks that followed, the EQ-5D gradually increased until week 5 (p < 0.05). At the end of week 6, patients had a mean score of 0.78 (range −0.03 to 1.00) for the EQ-5D (Figure 7, see Supplementary data).

General patient satisfaction

All the patients who were operated in an outpatient setting were satisfied with the short hospital stay. Of the patients who stayed at least 1 night, 3 would have preferred to stay longer. 1 of these patients experienced insufficient support from the hospital after discharge, 1 had a collapse at home, and 1 patient was dissatisfied with the communication between hospital and home care regarding wound treatment.

After 6 weeks, patients rated their contentment regarding the effect of the prosthesis as 9 on a 0 to 10 scale. 82 of 90 patients indicated an improvement in functioning during daily activities relative to their preoperative condition.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed how patients experienced the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge after inpatient or outpatient THA with fast track. Most patients were satisfied with their short hospital stay and preferred to complete their rehabilitation at home rather than in hospital.

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in a functional outcome score is of more importance than a statistically significant change in that score (Lee et al. 2003). Beard et al. (2015) found that an MCID of 11 points in the OHS represents a clinically relevant change over time in a group of patients. In this study, an increase of 14 points was measured in 6 weeks, and therefore hip function improved beyond the MCID.

An NRS score of "0" indicates "no pain", whereas a score of 3 or less indicates "mild pain", 4–6 "moderate pain", and 7–10 "severe pain" (Breivik et al. 2008). In the present study, patients experienced "moderate pain" preoperatively. From day 1 after hospital discharge to the end of week 6, they reported having "mild pain", which is comparable to the results of previous studies (Andersen et al. 2009, Winther et al. 2015).

One-fifth of our patients experienced problems in injecting themselves. This is less than in the study by van Egmond et al. (2015a), in which 40% of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients complained about injecting themselves. We cannot explain this difference. There is a lower risk of thromboembolic incidents in fast track, so a shorter duration of anticoagulation therapy should be considered (Husted et al. 2010, Kjaersgaard-Andersen and Kehlet 2012, Jorgensen et al. 2013).

The inpatient group and the outpatient group were different. Therefore, results in these groups cannot be compared. However, there were some obvious differences in outcome between them. Firstly, 40 of 41 patients in the outpatient group indicated an improvement in function during daily activities relative to their preoperative function. In the inpatient group, 42 of 49 patients indicated an improvement. Secondly, the outpatient group had lower pain scores postoperatively. Lungu et al. (2016) found that a greater level of comorbidity and worse general health are associated with worse pain and function following THA.

In the present study, patients who stayed in hospital at least 1 night had higher ASA scores than patients who went home on the day of surgery. Furthermore, the inpatient group was significantly older than outpatient group, which might also explain the differences in outcome in pain and function. However, Lungu et al. (2016) did not find any significant association between age and outcomes after THA. In our hospital, there is selection of patients who are to be operated in an outpatient setting, and they must fulfill the following criteria: ASA I or II; being motivated to go home on the day of surgery; having no cardiovascular history; not having insulin-dependent diabetes; and having sufficient support from a caring person at home during the first night postoperatively (Hartog et al. 2015).

This study had certain limitations. Firstly, we did not use any objective physical examination function score. Secondly, since an appreciable amount of effort is needed to complete the diary, several patients refused to join the study. This may have led to a selection bias, as only the motivated patients completed the diary. Based on the great variety of reactions of the patients, we presume, however, that this did not occur.

In conclusion, 97% of the patients were satisfied with the short LOS. During the first 6 weeks, pain scores decreased and function scores increased. Furthermore, even during the first week after surgery, patients had a better self-reported function score and better pain scores than preoperatively. The PROMs reported could serve as a guide for staff and patients alike to modify expectations and therefore potentially improve patient satisfaction.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 2–7 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1274865.

LK supported data collection, performed data analysis, and wrote and revised the manuscript. NM designed the study, supported data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. JE helped in composing the diary, performed data collection, supported data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. BV composed the diary and reviewed the manuscript. SV designed the study, operated all patients, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

We thank the Foundation for Scientific Research of Reinier de Graaf Groep, Delft, for funding this study. We are grateful to all the patients for their efforts in completing their diaries, and we especially thank N. de Esch for her help during the study.

SV has a consultant contract with Zimmer Biomet. No further competing interests to declare.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersen L O, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Husted H, Otte K S, Kehlet H.. Subacute pain and function after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2009; 64(5): 508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aynardi M, Post Z, Ong A, Orozco F, Sukin D C.. Outpatient surgery as a means of cost reduction in total hip arthroplasty: a case-control study. HSS J 2014; 10(3): 252–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri A, Vanhaecht K, Van H P, Sermeus W, Faggiano F, Marchisio S, Panella M.. Effects of clinical pathways in the joint replacement: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2009; 7: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard D J, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray D W, Carr A J, Price A J.. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68(1): 73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R A, Sanders S A, Thill E S, Sporer S M, Della V C.. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(6): 1424–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivik H, Borchgrevink P C, Allen S M, Rosseland L A, Romundstad L, Hals E K, Kvarstein G, Stubhaug A.. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101(1): 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A M, Perruccio A V, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker G A, Conaghan P G, Roos E M, Jordan J M, Maillefert J F, Dougados M, Lohmander L S.. The development of a short measure of physical function for hip OA HOOS-Physical Function Shortform (HOOS-PS): an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008; 16(5): 551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A.. Comparison of measures to assess outcomes in total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care 1996; 5(2): 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hartog Y M, Mathijssen N M, Vehmeijer S B.. Reduced length of hospital stay after the introduction of a rapid recovery protocol for primary THA procedures. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(5): 444–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsey M M, Kilgour M L, Santamaria N M, Choong P F.. Clinical pathways in hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised controlled study. Med J Aust 1999; 170(2): 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartog Y M, Mathijssen N M, Vehmeijer S B.. Total hip arthroplasty in an outpatient setting in 27 selected patients. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(6): 667–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S.. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(2): 168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Wong C, Kehlet H.. Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(5): 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H.. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011; 82(6): 679–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jensen C M, Solgaard S, Kehlet H.. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009: from research to implementation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132(1): 101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen C C, Kehlet H.. Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110(6): 972–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen C C, Jacobsen M K, Soeballe K, Hansen T B, Husted H, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Hansen L T, Laursen M B, Kehlet H.. Thromboprophylaxis only during hospitalisation in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty, a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3(12): e003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Kehlet H.. Should deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis be used in fast-track hip and knee replacement? Acta Orthop 2012; 83(2): 105–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers L M, Stalmeier P F, McDonnell J, Krabbe P F, van Busschbach J J.. [Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: the Dutch EQ-5D tariff]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005; 149(28): 1574–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J S, Hobden E, Stiell I G, Wells G A.. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med 2003; 10(10): 1128–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungu E, Maftoon S, Vendittoli P A, Desmeules F.. A systematic review of preoperative determinants of patient-reported pain and physical function up to 2 years following primary unilateral total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2016; 102(3):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillefert J F, Kloppenburg M, Fernandes L, Punzi L, Gunther K P, Martin M E, Lohmander L S, Pavelka K, Lopez-Olivo M A, Dougados M, Hawker G A.. Multi-language translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the OARSI/OMERACT measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009; 17(10): 1293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambough J B, Nunley R M, Curry M C, Steger-May K, Clohisy J C.. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(4): 521–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Egmond J C, Verburg H, Mathijssen N M.. The first 6 weeks of recovery after total knee arthroplasty with fast track. Acta Orthop 2015a; 86(6): 708–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Egmond J C, Verburg H, Vehmeijer S B, Mathijssen N M.. Early follow-up after primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty with rapid recovery: Focus groups. Acta Orthop Belg 2015b; 81(3): 447–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller S D.. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34(3): 220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther S B, Foss O A, Wik T S, Davis S P, Engdal M, Jessen V, Husby O S.. 1-year follow-up of 920 hip and knee arthroplasty patients after implementing fast-track. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(1): 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.