Abstract

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the human gastric mucosa and causes peptic ulcers and gastric carcinoma. H. pylori strain 26695 has a small genome (1.67 Mb), which codes for few known transcriptional regulators that control bacterial metabolism and virulence. We analyzed by qRT-PCR the expression of 16 transcriptional regulators in H. pylori 26695, including the three sigma factors under different environmental conditions. When bacteria were exposed to acidic pH, urea, nickel, or iron, the sigma factors were differentially expressed with a particularly strong induction of fliA. The regulatory genes hrcA, hup, and crdR were highly induced in the presence of urea, nickel, and iron. In terms of biofilm formation fliA, flgR, hp1021, fur, nikR, and crdR were induced in sessile bacteria. Transcriptional expression levels of rpoD, flgR, hspR, hp1043, and cheY were increased in contact with AGS epithelial cells. Kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline increased or decreased expression of regulatory genes, showing that these antibiotics affect the transcription of H. pylori. Our data indicate that environmental cues which may be present in the human stomach modulate H. pylori transcription.

Keywords: H. pylori, transcription factors, environmental cues

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium, a member of the Epsilon proteobacteria that colonizes the human gastric mucosa and is responsible for causing peptic ulcers and gastric carcinoma (Marshall and Warren, 1984; Parsonnet et al., 1991; Uemura et al., 2001). H. pylori survives in the hostile environment found in the stomach, which is partially attributed to the expression of virulence factors, such as secretion systems, cytotoxins, flagella, and adhesins. Unlike other Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli or Salmonella enterica, the H. pylori genome encodes only few known transcriptional regulators, which control expression of genes involved in bacterial metabolism and pathogenicity. This limited repertoire is likely due to its life style highly adapted to one particular niche, the human gastric mucosa. H. pylori strain 26695 has a small genome of 1.67 Mb (Tomb et al., 1997), and possesses three genes that code for sigma factors: rpoD (σ80), rpoN (σ54), and fliA (σ28). σ80 is a homolog of Gram-negative vegetative sigma factors responsible for the transcription of housekeeping genes (Tomb et al., 1997; Beier et al., 1998), whereas σ54 and σ28 are two alternative sigma factors dedicated mostly to control expression of flagella components (Fujinaga et al., 2001; Josenhans et al., 2002; Niehus et al., 2004). The response regulator FlgR is also involved in regulation of flagella synthesis (Spohn and Scarlato, 1999b), whereas bacterial chemotaxis is controlled by the CheY protein (Foynes et al., 2000; Terry et al., 2005). Master regulators of response to metals such as Fur, NikR, and CrdR activate or repress genes in the presence of iron, nickel or copper, respectively (Contreras et al., 2003; Waidner et al., 2005; Pich and Merrell, 2013). Environmental cues such as acid pH and temperature influence expression of HrcA, HspR, and ArsR regulatory proteins (Spohn and Scarlato, 1999a; Spohn et al., 2004; Pflock et al., 2005). Although many microarrays analysis have been published (Ang et al., 2001; Merrell et al., 2003a,b; Thompson et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2003; Bury-Mone et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004), little is known about the effects of environmental cues on the expression of H. pylori regulatory genes, including some poorly investigated transcriptional regulators.

In this work, we determined the expression profile of the transcriptional repertoire of H. pylori strain 26695 under several environmental conditions relevant for adaptation to its particular ecological niche of the human stomach, such as acidic pH, urea, nickel, and iron. In addition, we analyzed the expression of regulatory genes in biofilm formation and in the presence of AGS gastric epithelial cells. Finally, we studied the effect of the antibiotics kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline on the transcription of regulatory genes. Our study describes the transcriptional expression of H. pylori regulatory genes in response to different environmental conditions.

Materials and Methods

In silico Identification of H. pylori Transcription Factors

Selection of H. pylori transcription factors was performed as previously reported in the literature [(see Table 1) (Danielli et al., 2010)]. Sequence data and loci annotations from 260 H. pylori genomes were retrieved from the NCBI database1 by a series of custom Perl scripts. In addition, the genomes of 57 Helicobacter non-pylori strains were included in the comparative analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Each putative transcriptional factor was queried using PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) under the following parameters: matrix = BLOSUM62, word size = 3, PSI-BLAST threshold = 0.005, expect threshold = 10, and without filtering low complexity regions. Hits were carefully examined and selected according to their functional annotation.

Table 1.

Transcription factors of Helicobacter pylori 26695.

| Gene | Protein/Reference sequence | Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rpoD (hp0088) | RpoD, σ80/NP_206888.1 | Vegetative sigma factor, transcription of housekeeping genes | Tomb et al., 1997; Beier et al., 1998 |

| rpoN (hp0714) | RpoN, σ54/NP_207508.1 | Alternative sigma factor, expression of class II flagellar genes, stress and virulence | Josenhans et al., 2002; Niehus et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2013 |

| fliA (hp1032) | FliA, σ28/NP_207822.1 | Alternative sigma factor, expression of class III flagellar genes, stress and virulence | Josenhans et al., 2002; Niehus et al., 2004; Baidya et al., 2015 |

| hrcA (hp0111) | HrcA/NP_206911.1 | Involved in heat shock, stress response and motility | Spohn et al., 2004; Roncarati et al., 2007, 2014 |

| arsR (hp0166) | ArsR/NP_206965.1 | Acid adaptation, acetone metabolism, oxidative stress response, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation | Pflock et al., 2005, 2006; Loh et al., 2010; Servetas et al., 2016 |

| hp0222 | HP0222/NP_207020.1 | Possibly involved in acid response and/or bacterium-epithelial cell contact | Ang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2004; Popescu et al., 2005 |

| hp0564 | HP0564/NP_207359.2 | Paralog of HP0222; unknown function | Borin and Krezel, 2008 |

| flgR (hp0703) | FlgR/NP_207497.1 | RpoN-dependent master regulator of class II flagellar genes | Spohn and Scarlato, 1999b; Brahmachary et al., 2004 |

| hup (hp0835) | HU/NP_207628.1 | Acid stress response, DNA protection from oxidative stress, involved in mouse colonization | Almarza et al., 2015; Wang and Maier, 2015 |

| hp1021 | HP1021/NP_207811.1 | Chromosomal replication regulator, acetone metabolism and growth | Beier and Frank, 2000; Pflock et al., 2007a; Donczew et al., 2015 |

| hspR (hp1025) | HspR/NP_207815.1 | Heat shock, acidic/osmotic stress response, and motility | Spohn and Scarlato, 1999a,b; Spohn et al., 2002, 2004; Roncarati et al., 2007 |

| fur (hp1027) | Fur/NP_207817.1 | Pleiotropic regulator involved in acid adaptation, metal homeostasis and Mongolian gerbil/mouse colonization | Bijlsma et al., 2002; Harris et al., 2002; van Vliet et al., 2003; Bury-Mone et al., 2004; Danielli et al., 2006; Gancz et al., 2006 |

| hsrA (hp1043) | HsrA/NP_207833.1 | Cell viability, oxidative stress, virulence, response to metronidazole | Olekhnovich et al., 2013, 2014; Vannini et al., 2016 |

| cheY (hp1067) | CheY/NP_207858.1 | Chemotaxis, motility, Mongolian gerbil/mouse colonization | Beier et al., 1997; Foynes et al., 2000; McGee et al., 2005; Terry et al., 2005 |

| nikR (hp1338) | NikR/NP_208130.1 | Nickel-response pleiotropic regulator, metal (copper, iron, and nickel) homeostasis, acid adaptation, iron uptake/storage, motility, chemotaxis, stress response, and mouse colonization | Contreras et al., 2003; Bury-Mone et al., 2004; Ernst et al., 2005b; Muller et al., 2011 |

| crdR (hp1365) | CrdR/NP_208157.1 | Copper resistance, survival under nitrosative stress, and mouse colonization | Panthel et al., 2003; Waidner et al., 2005; Hung et al., 2015 |

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

H. pylori 26695 was grown for 3 days on blood agar plates containing 10% defibrinated sheep blood, at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions. A bacterial suspension was prepared in Brucella broth (BB), and adjusted to an optical density of 0.1 at 600 nm (2 × 106 CFU/ml). H. pylori was then grown at 37°C for 24 h (logarithmic growth phase) or 48 h (stationary growth phase) in BB supplemented with 10% decomplemented fetal bovine serum (BB + FBS) under the following conditions: adjusted to pH 5.5, or containing either urea [5 mM CO(NH2)2], nickel [250 mM NiCl2], or iron [150 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2⋅6H2O] as previously described (Contreras et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2003; Vannini et al., 2014; Cardenas-Mondragon et al., 2016). Fold-changes in transcription were determined by calculating the relative expression of transcription regulator genes under different environmental conditions as compared to expression in BB + FBS. Experiments were performed in triplicate on three different days and the results shown are the mean of the data produced.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from bacteria grown under different culture conditions using the hot phenol method (Jahn et al., 2008) with some modifications. Briefly, after the lysate was obtained, an equal volume of phenol-saturated water was added, mixed and incubated at 65°C for 5 min. The samples were chilled on ice and centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The aqueous layer was transferred to an 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube, RNA was precipitated with cold ethanol and incubated at -70°C overnight. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 19,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Pellets were washed with cold 70% ethanol and centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. After careful removal of the ethanol, the pellets were air dried for 15 min in the Centrifugal Vacuum Concentrator 5301 (Eppendorf). The pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of DEPC-treated water. Purification of RNA was performed using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion, Inc.). Quality of RNA was assessed using a NanoDrop (ND-1000; Thermo Scientific) and a bleach 2% agarose gel as previously described (Aranda et al., 2012). qRT-PCR was performed as previously reported (Ares et al., 2016). Specific primers were designed with the Primer3Plus software2 and are listed in Table 2. The absence of contaminating DNA was controlled by lack of amplification products after 35 qPCR cycles using RNA as template. Control reactions with no template (water) and with no reverse transcriptase were run in all experiments. 16S rRNA (HPrrnA16S) was used as a reference gene for normalization and the relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Expression of 16S rRNA remained unaffected in all conditions tested (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 2.

Primers for qPCR used in this study.

| Primers | Sequence | Target gene |

|---|---|---|

| rpoD-F | TAT CGC TCA AGT GCC AGA AG | rpoD |

| rpoD-R | TGT TGG GGG CTA GAT CAA AG | |

| rpoN-F | CAG CGG GTT GAA TAA TGA GG | rpoN |

| rpoN-R | ACG CTT GCG CAC TTT TTC | |

| fliA-F | TCG TCT AAA AGA GCG CTT GC | fliA |

| fliA-R | CTT CGC ATA CCC CCA AAA AG | |

| hrcA-F | TTT CTT GCG CAC TGG GTT AC | hrcA |

| hrcA-R | GAA AGA AGC AGC GAT TGA GC | |

| arsR-F | GAG CGA GTT TTT GCT CCA AC | arsR |

| arsR-R | GCC CGT CTA AAT TAG GCA AAG | |

| hp0222-F | CTA GGA CGC AAA CCA AAA GC | hp0222 |

| hp0222-R | CCC ACG CTT TCT TCT TCT TC | |

| hp0564-F | GTC GCT GTA GAT GAG CTG AAA C | hp0564 |

| hp0564-R | GGC GTT TGA CAA AAG AAT TG | |

| flgR-F | CAG GCC TTA AAA GTC GCA AG | flgR |

| flgR-R | CGC TAT AAA AGG GTG CTT GG | |

| hup-F | GTG GAG TTG ATC GGT TTT GG | hup |

| hup-R | TTA GGC ACC CGT TTG TCT TC | |

| hp1021-F | GTT GCG CAA GAT CCA ATA CC | hp1021 |

| hp1021-R | AGG GCG TGT GGA TGA TAA AG | |

| hspR-F | CGG GCG TGG ATA TTA TCT TG | hspR |

| hspR-R | TGT TTG TGC AGA GCG TCT TG | |

| fur-F | GAA GAA GTG GTG AGC GTT TTG | fur |

| fur-R | CCT TTT GGC GGA TAG AAT GC | |

| hsrA-F | GGA AGA AGT CCA TGC GTT TG | hsrA |

| hsrA-R | CAA ACG AGC CTC AAT CCT TG | |

| cheY-F | TGG AAG CTT GGG AGA AAC TG | cheY |

| cheY-R | CAG AGC GCA CCT TTT TAA CG | |

| nikR-F | CAT CCG CTT TTC GGT TTC | nikR |

| nikR-R | CAT GTC GCG CAC TAA TTC TG | |

| crdR-F | CTT AGG CGT GGC TAA AAT GC | crdR |

| crdR-R | CAA ACG CCC CAA AAA CAC |

Biofilm Formation

H. pylori was grown on blood agar medium supplemented with 10% defibrinated sheep blood at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions. Biofilm formation on abiotic surface (polystyrene) was analyzed using 6-well polystyrene plates, inoculated with 3 ml of a bacterial suspension (in BB + FBS, at a final concentration of OD600nm = 0.1) in each well. The plates were incubated during 3 days at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions as previously reported (Cardenas-Mondragon et al., 2016). Supernatant (planktonic) and adhered (sessile) bacteria were recovered for RNA extraction. Fold-change in gene transcription was determined by calculating the relative expression of transcription regulator genes within biofilms (sessile bacteria) as compared to planktonic bacteria. Quantifications were performed in triplicate on three different days and the results shown are the mean of the three experiments.

Infection of AGS Cells

AGS gastric epithelial cells were grown to about 75% confluence in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, and washed thrice with PBS before adding fresh RPMI media with 10% FBS. H. pylori 26695 was grown in BB + FBS for 24 h, suspended in RPMI, and added to the AGS cell culture at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 (bacteria/cell). Infected cells were incubated at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions for 0 or 6 h, and bacteria were recovered. At the end of the incubation period, the H. pylori-infected AGS cells were washed thrice with PBS and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Large debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation for 5 min at 200 × g and adhered bacteria were pelleted at 20,000 g for 10 min. RNA was extracted from adhered bacteria to determine gene expression. Fold-change in gene transcription was determined by calculating the relative expression of the transcription factors genes with respect to bacteria at time 0 of infection. Fold-change in gene transcription of H. pylori grown in RPMI-1640 + FBS (for 0 or 6 h) was calculated as control of expression. Assays were performed in triplicate on three different days and the results shown are the mean of the three experiments.

Transcription in the Presence of Antibiotics

H. pylori was grown in BB + FBS at 37°C for 48 h (stationary phase), with gentle shaking under microaerophilic conditions. The antibiotics kanamycin (Km, 50 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (Cm, 30 μg/mL) or tetracycline (Tc, 10 μg/mL) were added and the cultures were incubated for 1 h as previously described (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al., 2010; Cardenas-Mondragon et al., 2016). Antibiotics were used at the minimal inhibitory concentrations that have been reported for E. coli and S. enterica (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al., 2010; Maisonneuve et al., 2011; Silva-Herzog et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). Fold-change in gene transcription was determined by calculating the relative expression of the transcription regulators genes in the presence of each antibiotic as compared to bacteria growing without antibiotics for 1 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate on three different days and the results shown are the mean of the three experiments.

Heatmap Construction

To show the fold-changes in gene expression, we selected the “heatmap.2” function of the R software, using the “gplots” package. The rows (culturing conditions) were hierarchically clustered (“hclust” function, “ward.D” method) according to the absolute fold-changes in gene expression.

In order to illustrate the presence/absence of transcription factors in all Helicobacter genomes, an amino acid sequences content matrix (“heatmap” function) was built using the R software3 (v3.2.4). 260 H. pylori and 57 H. non-pylori genomes were retrieved from the NCBI database4 by a series of custom Perl scripts. These paired loci were hierarchically clustered (“hclust” function, “ward.D” method) according to their loci-content using a sidelong dendrogram.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical differences, one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s comparison test was performed using Prism5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Environmental Cues that Trigger the Expression of Transcription Factor Genes

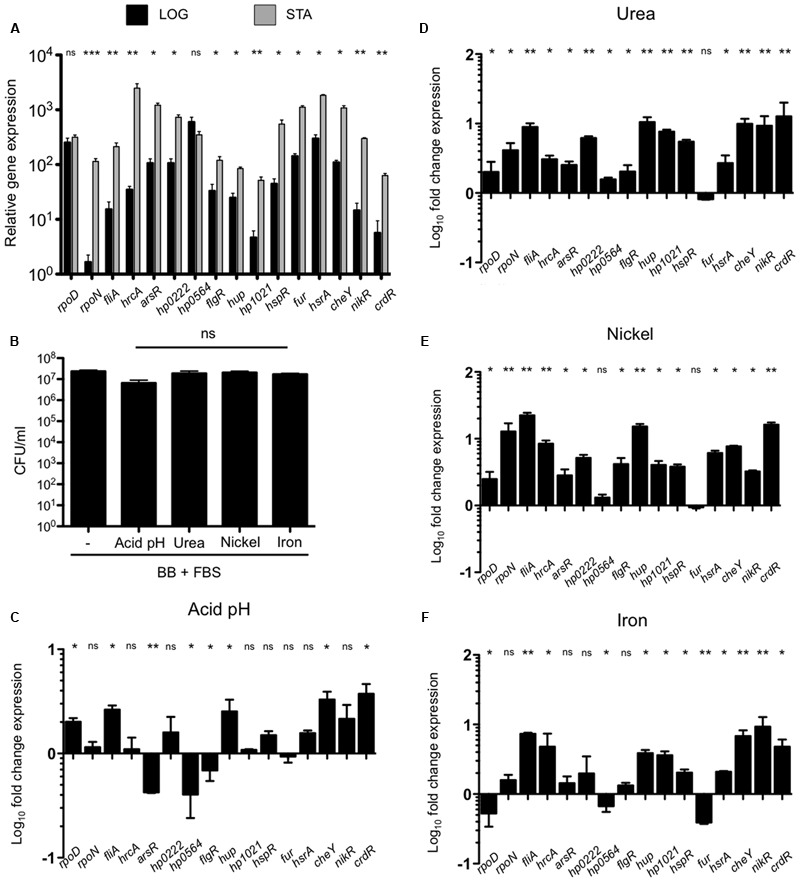

H. pylori adaptation to the gastric mucosa conditions is mediated by a limited number of regulatory genes. An analysis of the reports of 26695 H. pylori strain identified 16 genes that code for transcriptional regulators, including three sigma factors (Table 1). We performed qRT-PCR on RNA extracted from bacteria grown during both exponential (24 h) and stationary phase (48 h) and the expression of all regulatory genes was calculated during both growth phases. Expression of most genes was higher during stationary phase than in exponential phase, except for rpoD and hp0564 (Figure 1A). Therefore, we determined the expression of all transcription regulators during stationary phase in media with acid pH or in the presence of urea, nickel, or iron. None of these environmental variations promoted or inhibited growth of H. pylori (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the conditions tested resulted mostly in increased expression of transcription regulators (Figures 1C–F, 4). Regarding sigma factors, fliA expression increased with all treatments, with the highest induction levels observed in response to nickel. The same was true for rpoD with exception of treatment with iron, which resulted in down regulation of the gene (Figure 1F); whereas rpoN expression significantly increased only after exposure to urea or nickel (Figures 1D,E). Concerning the other transcriptional regulators, acidic pH resulted in down regulation of arsR, hp0564, and flgR and a moderate increase of hup, cheY, or crdR, whereas the remaining genes were unaffected (Figure 1C). Exposure of bacteria to urea and nickel ions resulted in more pronounced transcriptional changes (Figures 1D,E). However, whereas expression of most transcription factors increased considerably, hp0564 and fur showed only subtle changes in response to urea and nickel. hp0564, fur, and rpoD were the only genes tested to be down regulated in response to iron, whereas expression of the other transcription regulators increased (hrcA, hup, hp1021, hsrA, cheY, nikR, and crdR), or did not change (arsR, hp0222, flgR, and hspR) (Figure 1F).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of environmental cues on expression of transcription factors. (A) Expression (qRT-PCR) of the transcription factors of H. pylori 26695 in exponential (black bars) and stationary growth phase (gray bars). (B) Determination of colony forming units (CFU) of H. pylori 26695 grown to stationary phase (48 h) in BB + FBS under acid pH (pH 5.5), or in presence of urea (5 mM), nickel (250 μM), or iron (150 μM). Fold-change expression (qRT-PCR) of the transcription factors under acid pH (C), urea (D), nickel (E), and iron (F). Data is represented as fold-change expression of the regulatory gene under different environmental conditions as compared to plain BB + FBS at 48 h. Data represent means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. ns, not significant; statistically significant ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

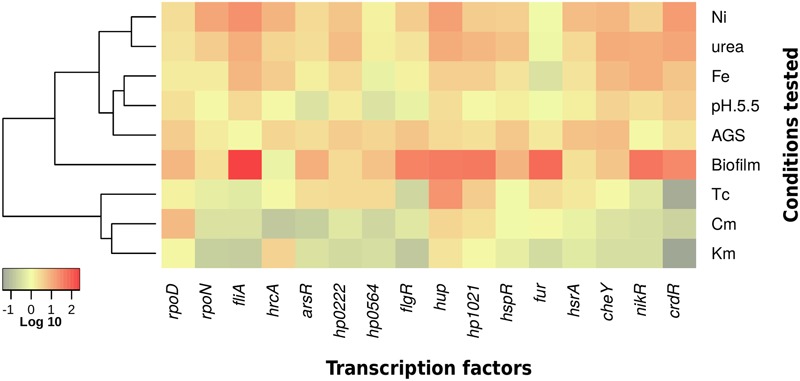

FIGURE 4.

Summary of effects of different environmental stimuli on expression of H. pylori transcription factors. Heatmap of gene expression levels at diverse culturing conditions. Relative gene expression values are expressed as fold-changes in a Log10 scale. The color-coding scale denotes up regulation in red and down regulation in green.

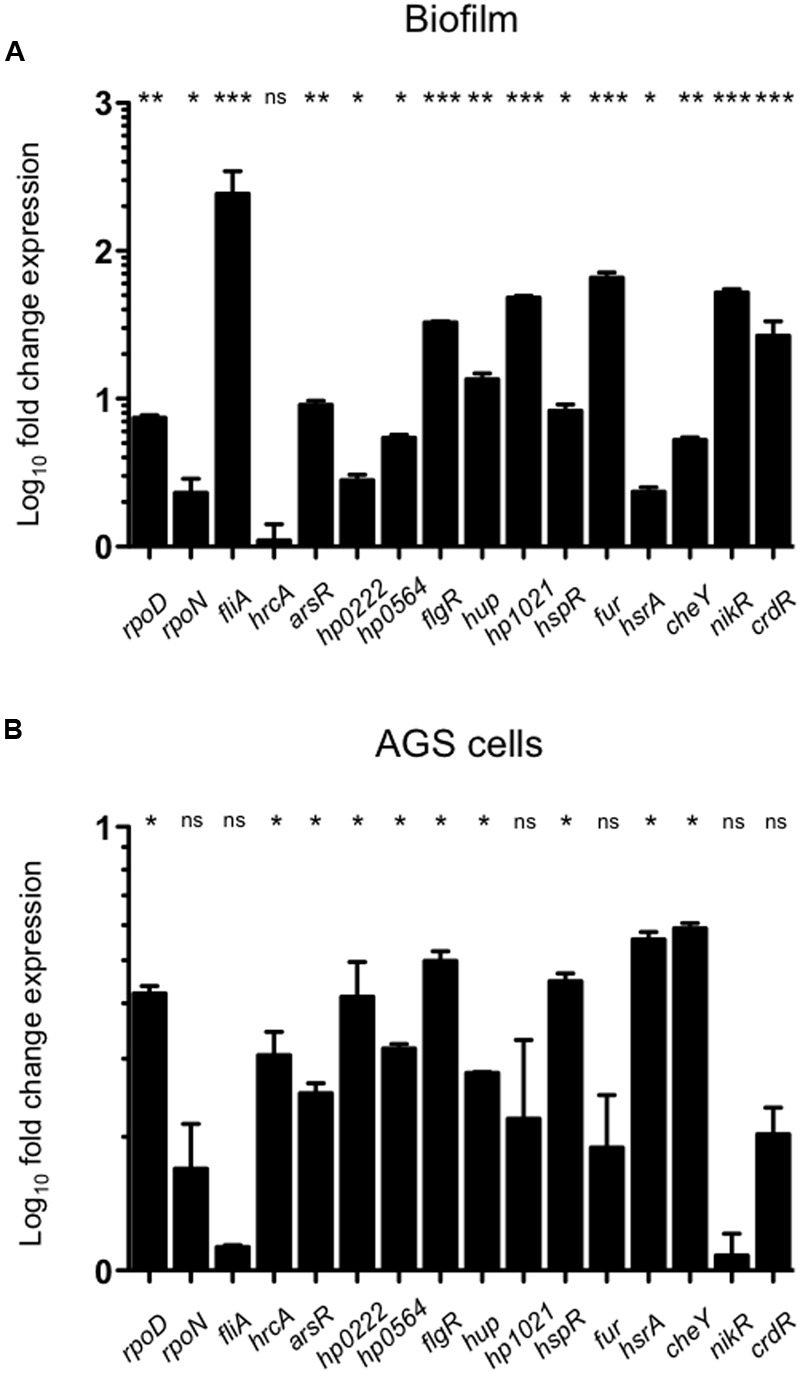

The Effect of Biofilm Formation and Interaction with Gastric Epithelial Cells on Expression of H. pylori Transcription Factors

During infection, H. pylori closely interacts with the cells of the gastric mucosa, which may result in bacterial biofilm formation in later stages of infection (Carron et al., 2006). To study the effect of bacterial interaction with cells of the gastric mucosa or the growth in biofilms on the expression of transcription regulators, bacteria were grown either stationary on polystyrene surfaces or brought into contact with AGS cells, and their transcription profiles were analyzed. As control for the interaction with AGS cells, H. pylori was grown in RPMI-1640 medium for the same amount of time, which did not result in any changes in gene transcription. Expression of rpoN did not change during growth in biofilm or upon attachment to AGS cells, whereas rpoD expression increased under both conditions (Figure 2A). However, the most striking effect among the three sigma factors was a dramatic increase of fliA expression in response to biofilm formation (Figure 2). Only few of the other regulatory genes remained unaffected by the interaction with abiotic surfaces (hrcA), or epithelial cells (hp1021, fur, nikR, and crdR). All other transcriptional regulators were up regulated upon contact with AGS cells, and to a greater extent during biofilm formation (Figures 2, 4).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of transcription regulators during biofilm formation or in response to interaction with AGS cells. Expression levels of the transcription regulators during bacterial biofilm formation (A) or H. pylori interaction with AGS cells (B) were determined by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as fold-change expression levels and represent means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. ns, not significant; statistically significant ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

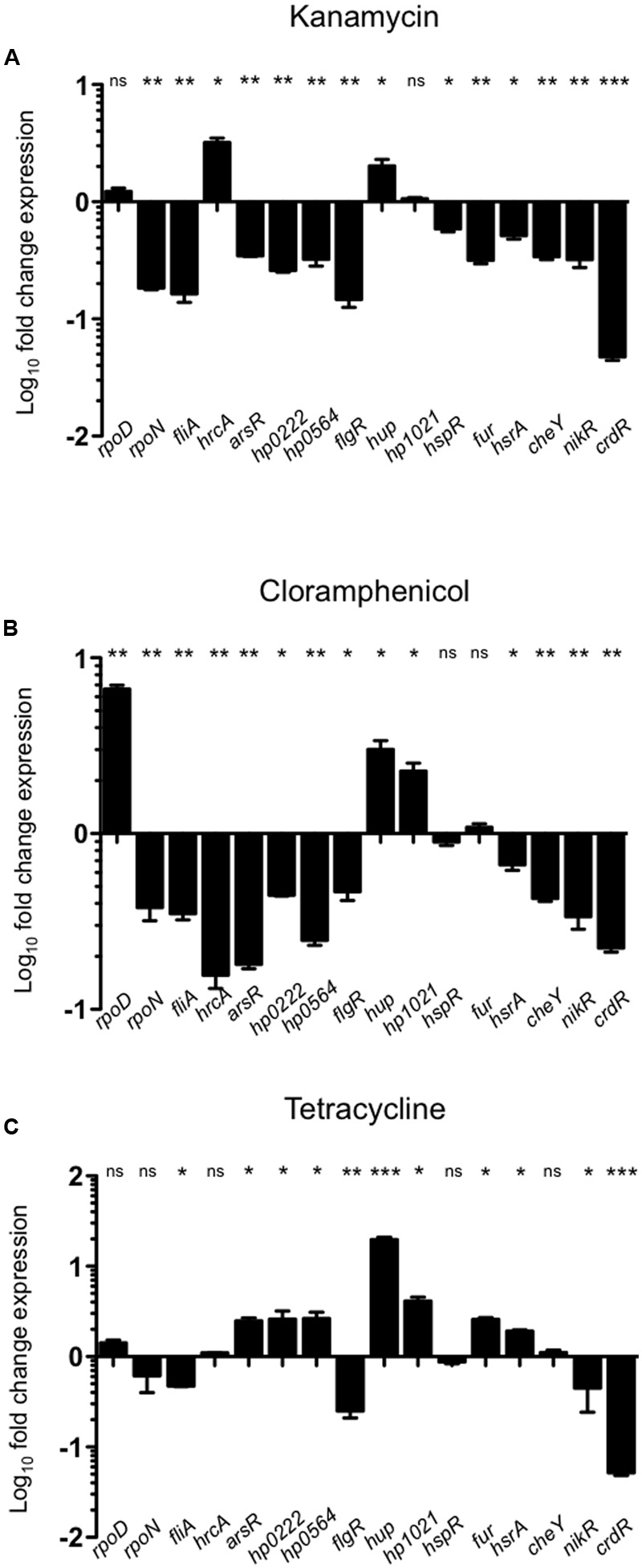

Antibiotic Exposure Decreases Expression of Most H. pylori Transcription Regulators

Our group recently reported that antibiotics affect the expression of virulence factors in H. pylori (Cardenas-Mondragon et al., 2016). Whereas the environmental conditions tested here mostly up regulated expression of the transcription regulators analyzed, exposure to different antibiotics resulted predominantly in gene repression (Figures 3, 4). This was likely not due to compromised cell growth, since the antibiotic concentrations used here did not affect the viability of the bacteria (Supplementary Figure S2). Among the three sigma factors, rpoD expression was not affected by exposure to kanamycin or tetracycline and increased in response to chloramphenicol (Figure 3), whereas expression of rpoN and fliA was down regulated or not affected after exposure to all three antibiotics tested (Figure 3). Expression levels of the other transcription regulators were mostly repressed in response to antibiotic treatment, particularly upon exposure to kanamycin or chloramphenicol (Figures 3A,B). Only hrcA and hup mRNA levels were slightly increased in the presence of kanamycin, whereas those of hp1021 were not affected (Figure 3A). While negatively regulating expression of most transcription factors, chloramphenicol led to a mild increase of hup and hp1021 levels, and did not affect expression of fur (Figure 3B). In contrast, tetracycline had stimulating effects on the expression of several transcription factors, including hp0166, hp0222 hp0564, hup, and hp1021 (Figure 3C). Transcription of flgR, nikR, and crdR decreased upon tetracycline treatment, whereas transcription levels of hrcA, hspR, and cheY were not affected (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of antibiotics on expression of transcription factors. Expression levels of transcription factors after treatment of bacteria with different antibiotics [Kanamycin (A), Chloramphenicol (B), and Tetracycline (C)] for 1 h were determined by qRT-PCR and compared to those in untreated bacteria. Data are expressed as fold-change expression and represent the means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. ns, not significant; statistically significant ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

Transcriptional Regulator Genes Are Highly Conserved in H. pylori Strains

We performed a Blast search in genomes deposited in GenBank5 using the amino acids sequences of the 16 transcriptional regulators identified in H. pylori 26695. The transcription factors were highly prevalent and well conserved among different H. pylori isolates (Figure 5). We studied the occurrence of these genes in other Helicobacter species, and found that their presence changed from one species to another. Two species that are phylogenetically closely related to H. pylori, H. acinonychis (isolated from big cats), and H. cetorum (isolated from marine mammals), encoded all 16 transcriptional regulators with high identities to those of H. pylori strains, and clustered closer to the H. pylori strains (Figure 5). Interestingly, transcription regulators such as hp0222 and hp0564 presented low prevalence in most of the H. non-pylori strains, showing that both proteins are highly conserved in H. pylori, H. acinonychis, and H. cetorum.

FIGURE 5.

Prevalence of transcription regulators in the Helicobacter genus. Amino acid sequences of Helicobacter transcription factors were analyzed. Heatmaps and hierarchical clustering of selected amino acid sequences for transcription factors for both Helicobacter and Helicobacter non-pylori showing the identity of transcription regulators were created using the R (version 3.2.4) hclust function with the “ward.D” method.

Discussion

H. pylori is a highly specialized bacterium that is exclusively found in the human gastric mucosa. In this work, we describe the expression of H. pylori transcriptional regulatory genes under different environmental conditions. Most transcription factors were highly expressed when H. pylori reached the early stationary phase. At this growth phase, H. pylori is exposed to specific stress signals such as pH changes, starvation, reactive oxygen species that would activate its transcriptional repertoire, suggesting that the stationary phase may mimic the conditions found by the bacteria in the host. Acid pH, the presence of urea, nickel, or iron are environmental cues required for optimal adaptation of H. pylori to its natural niche. Whereas all of the above conditions boosted fliA expression, rpoD showed only a mild increase in transcription after bacterial exposure to acid pH, urea, and nickel, and a decrease in response to iron. The expression of rpoN significantly increased upon treatment of bacteria with urea or nickel; RpoN was initially described as regulator of flagellar genes, but recent studies show that it also controls several bacterial regulatory processes involved in energy metabolism, biosynthesis, protein fate, oxidative stress, and virulence (Sun et al., 2013). fliA was strongly expressed even under environmental conditions that are not common inducers of flagella synthesis, but are known to affect other bacterial components or pathways. In fact, FliA regulates expression of outer membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharide synthesis, DNA restriction, and CagA (Josenhans et al., 2002; Baidya et al., 2015), a protein involved in virulence and associated with the development of gastric carcinoma (Ohnishi et al., 2008). Our data support the notion that FliA regulates different bacterial functions other than the flagellum.

H. pylori is exposed to changes in pH while passing from the stomach lumen through the mucus layer to interact with epithelial cells, and this pH gradient is used by the bacteria for spatial orientation (Schreiber et al., 2004). Accordingly, changes in pH strongly affect expression of transcriptional regulators that control genes involved in colonization and persistence in the human host. Our data show that an acidic pH repressed arsR, hp0564, and flgR, while stimulating hup, cheY, and crdR. The hup gene codes for the HU nucleoid protein, which has a regulatory role in the response to acid stress in H. pylori. Thus, hup mutants are less viable than wild type bacteria at pH 5.5 and during stomach colonization due to down regulation of both urease (ureA) and arginine decarboxylase (speA) in the absence of HU nucleoid protein (Wang et al., 2012; Almarza et al., 2015). CheY and CrdR response regulators are also crucial for a successful colonization of the animal stomach (Foynes et al., 2000; Panthel et al., 2003; McGee et al., 2005; Terry et al., 2005). CheY expression is essential for the chemotactic motility required to reach and colonize the gastric epithelia, and is likely to be triggered in the acidic milieu of the stomach lumen. In contrast, CrdR has not been shown to be involved in the regulation of gene expression in response to acidic pH (Pflock et al., 2007b), although copper can be present in the acidic environment of the human stomach, and regulation of its uptake is important for keeping the balance between supplying copper as respiration co-factor, and avoiding copper-induced toxicity (Haley and Gaddy, 2015). Interestingly, the master regulator of the acid response arsR was repressed in acidic pH, which confirms reports that ArsR may also act as transcriptional auto-repressor under an acidic pH (Dietz et al., 2002).

Urea, nickel, and iron are crucial for H. pylori pathogenesis and they control regulatory networks responding to their presence. We found that expression of most of the transcription regulators tested increased when bacteria were exposed to urea, nickel, or iron. Nickel serves as essential co-factor for the urease enzyme, which enables H. pylori survival at acidic pH (Khan et al., 2009). The up regulation of nikR expression that we observed contrasted with the auto-negative regulation reported for the nikR promoter (Delany et al., 2002; Contreras et al., 2003). The conditions of growth (stationary phase) and nickel concentrations (250 μM) that we tested resulted in increased nikR expression. However, nikR expression showed slight variations in response to low (1 μM) and high (100 μM) concentrations of nickel (Davis et al., 2006), suggesting that nickel may modulate nikR transcription in a concentration-dependent manner. Interestingly, rpoD and fur were down regulated in the presence of iron. While iron-mediated fur repression can be explained by the negative auto-regulation of this transcription factor upon iron-binding (Delany et al., 2002), the decrease in rpoD levels is hard to explain. Whilst the evaluation of each environmental condition provides relevant information about H. pylori physiology, the combination of these stimuli could better mimic the in vivo response of the bacteria in the infection context.

One of the strategies employed by H. pylori to persist and colonize the stomach is biofilm formation. Analysis of bacteria grown in biofilm revealed an interesting expression pattern of the three sigma factors: whereas rpoN was not affected, expression of rpoD and fliA increased during biofilm formation. FliA has been found to control the lpxC gene, which is involved in the early steps of lipid A synthesis in H. pylori (Josenhans et al., 2002). The marked increase of fliA expression that we found in sessile, aggregated bacteria is in agreement with reports about the effect of lipid A architecture on biofilm formation (Gaddy et al., 2015). In addition, with the exception of hrcA, expression of all transcription factor genes studied increased during biofilm formation, and the relative increase of several of them was the highest increase observed across all the conditions tested. This remarkably activated state of the regulatory transcriptome highlights the importance of forming sessile microbial communities in H. pylori ecology.

Similar to the response during biofilm formation, the presence of gastric epithelial cells significantly increased expression levels of several transcription factors, except for fur, nikR, and crdR. Expression of these three master regulators of virulence remained unaffected in our AGS cell model, which correlates with the previously reported lack of activation or repression of these regulators after the interaction with gastric epithelial cells (Kim et al., 2004).

It has been hypothesized that the reduced number of transcriptional regulators in the H. pylori genome has been compensated by gain of functions in the remaining transcription factors, as compared to their functions by homologs found in other species (Ernst et al., 2005a). For instance, the H. pylori Fur protein was not only found to be involved in iron homeostasis, but it also participated in several other additional pathways including those of oxidative stress resistance (Harris et al., 2002) and acid regulation (Bijlsma et al., 2002; van Vliet et al., 2004), and has been found essential for colonization of the gastric mucosa (Bury-Mone et al., 2004). Moreover, unlike Fur homologs in other species, H. pylori Fur has been found to mediate gene regulation even in its iron-free (apo) form (Bereswill et al., 2000; Delany et al., 2001; Carpenter et al., 2013). Interestingly, whereas most conditions tested here showed only moderate effects on Fur expression, biofilm formation resulted in a marked up regulation of the gene, suggesting functions beyond regulation of iron metabolism.

The presence of antibiotics can alter the expression of genes related to the bacterial stress and virulence on a transcriptional level. Interestingly, most regulatory genes were repressed in response to antibiotic treatment. rpoN, fliA, flgR, and crdR genes presented a negative regulation profile in the presence of kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. In contrast, expression levels of rpoD and hup were highly stimulated under chloramphenicol or tetracycline treatment. These last antibiotics inhibit bacterial translation, differentially affecting the 50S and 30S ribosomal subunits, respectively. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the regulation in expression of transcriptional regulators in the presence of antibiotics have been poorly studied. About this, 16S rRNA expression was affected in the presence of kanamycin and chloramphenicol, showing that this gene was not completely stable and that antibiotic treatment may have affected the expression of this reference gene under these conditions. For a better analysis in presence of these antibiotics, it is necessary the selection and validation of other reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization as was recently reported (Martins et al., 2017).

During analysis of Helicobacter sequences we found that the transcriptional regulators were highly identical among H. pylori species. Interestingly, H. acynonichis and H. cetorum grouped together with H. pylori, corroborating the close phylogenetic relation between these species. The transcriptional regulators HP0222 and HP0564 appear to be conserved in H. pylori and its closely related species, while they were absent in most of the remaining Helicobacter species. Since H. pylori, H. acynonichis, and H. cetorum are all found within mammalian stomachs, these two regulators may confer an adaptive advantage in this particular ecological niche. In line with these findings, expression levels of both, hp0564 and hp0222 increased in contact with AGS gastric epithelial cells, corroborating a report by Kim et al. (2004) on hp0222. However, we did not observe enhanced hp0222 expression under acidic pH, contrasting with the report by Ang et al. (2001).

Recently, we reported the transcriptional profiling of type II toxin-antitoxin genes under different environmental conditions (Cardenas-Mondragon et al., 2016). The type II antitoxins function as transcriptional repressors of their own expressions (Yamaguchi and Inouye, 2011) and also regulate the expression of other genes related with cellular functions such as biofilm formation, persistence, and the general stress response (Wang and Wood, 2011; Hu et al., 2012). Our findings here expand the transcriptional repertoire of H. pylori to respond to the different stresses found in the stomach niche.

In summary, our data show that the repertoire of transcriptional regulators of H. pylori possesses a functional plasticity needed to respond to different environmental cues and to integrate them for the survival and persistence of this bacterium in the stomach niche.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MDC. Performed the experiments: MDC, KvB, MA, LP, JM-C, HV-S, and CJ-G. Analyzed the data: MDC, KvB, and MA. Wrote the paper: MDC, KvB, and JT.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diana Márquez-Delfín for technical assistance.

Funding. This study was supported by grant FIS/IMSS/PROT/G14/1332 (to MDC) from the Fondo de Investigación en Salud (FIS)-IMSS, México

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00615/full#supplementary-material

Expression of reference gene (HPrrnA16S) under different environmental conditions. Panels show the expression of reference gene during stationary phase in BB + FBS with changes in pH and concentrations of urea, nickel, and iron (A), or in presence of antibiotics (B) or in contact on abiotic and biotic surfaces (C). (-) Indicates the BB + FBS plain (neutral pH with no addition of components). Quantification of expression is showed as copies of HPrrnA16S/μg RNA.

Effect of antibiotics on H. pylori growth. Determination of colony forming units (CFU) of H. pylori 26695 grown during 1 h in presence of antibiotics (Km, Kanamycin; Chloramphenicol, Cm; Tetracycline, Tc).

References

- Almarza O., Nunez D., Toledo H. (2015). The DNA-binding protein HU has a regulatory role in the acid stress response mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 20 29–40. 10.1111/hel.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang S., Lee C. Z., Peck K., Sindici M., Matrubutham U., Gleeson M. A., et al. (2001). Acid-induced gene expression in Helicobacter pylori: study in genomic scale by microarray. Infect. Immun. 69 1679–1686. 10.1128/iai.69.3.1679-1686.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda P. S., Lajoie D. M., Jorcyk C. L. (2012). Bleach gel: a simple agarose gel for analyzing RNA quality. Electrophoresis 33 366–369. 10.1002/elps.201100335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares M. A., Fernandez-Vazquez J. L., Rosales-Reyes R., Jarillo-Quijada M. D., Von Bargen K., Torres J., et al. (2016). H-NS nucleoid protein controls virulence features of Klebsiella pneumoniae by regulating the expression of type 3 pili and the capsule polysaccharide. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 6:13 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baidya A. K., Bhattacharya S., Chowdhury R. (2015). Role of the flagellar hook-length control protein FliK and sigma28 in cagA expression in gastric cell-adhered Helicobacter pylori. J. Infect. Dis. 211 1779–1789. 10.1093/infdis/jiu808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier D., Frank R. (2000). Molecular characterization of two-component systems of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 182 2068–2076. 10.1128/jb.182.8.2068-2076.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier D., Spohn G., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (1997). Identification and characterization of an operon of Helicobacter pylori that is involved in motility and stress adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 179 4676–4683. 10.1128/jb.179.15.4676-4683.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier D., Spohn G., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (1998). Functional analysis of the Helicobacter pylori principal sigma subunit of RNA polymerase reveals that the spacer region is important for efficient transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 30 121–134. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereswill S., Greiner S., Van Vliet A. H., Waidner B., Fassbinder F., Schiltz E., et al. (2000). Regulation of ferritin-mediated cytoplasmic iron storage by the ferric uptake regulator homolog (Fur) of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 182 5948–5953. 10.1128/jb.182.21.5948-5953.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma J. J., Waidner B., Vliet A. H., Hughes N. J., Hag S., Bereswill S., et al. (2002). The Helicobacter pylori homologue of the ferric uptake regulator is involved in acid resistance. Infect. Immun. 70 606–611. 10.1128/iai.70.2.606-611.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borin B. N., Krezel A. M. (2008). Structure of HP0564 from Helicobacter pylori identifies it as a new transcriptional regulator. Proteins 73 265–268. 10.1002/prot.22159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmachary P., Dashti M. G., Olson J. W., Hoover T. R. (2004). Helicobacter pylori FlgR is an enhancer-independent activator of sigma54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme. J. Bacteriol. 186 4535–4542. 10.1128/JB.186.14.4535-4542.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury-Mone S., Thiberge J. M., Contreras M., Maitournam A., Labigne A., De Reuse H. (2004). Responsiveness to acidity via metal ion regulators mediates virulence in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 53 623–638. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas-Mondragon M. G., Ares M. A., Panunzi L. G., Pacheco S., Camorlinga-Ponce M., Giron J. A., et al. (2016). Transcriptional profiling of type II toxin-antitoxin genes of Helicobacter pylori under different environmental conditions: identification of HP0967-HP0968 system. Front. Microbiol. 7:1872 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B. M., Gilbreath J. J., Pich O. Q., Mckelvey A. M., Maynard E. L., Li Z. Z., et al. (2013). Identification and characterization of novel Helicobacter pylori apo-fur-regulated target genes. J. Bacteriol. 195 5526–5539. 10.1128/JB.01026-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carron M. A., Tran V. R., Sugawa C., Coticchia J. M. (2006). Identification of Helicobacter pylori biofilms in human gastric mucosa. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 10 712–717. 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Dalsgaard M., Jorgensen M. G., Gerdes K. (2010). Three new RelE-homologous mRNA interferases of Escherichia coli differentially induced by environmental stresses. Mol. Microbiol. 75 333–348. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06969.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras M., Thiberge J. M., Mandrand-Berthelot M. A., Labigne A. (2003). Characterization of the roles of NikR, a nickel-responsive pleiotropic autoregulator of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 49 947–963. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielli A., Amore G., Scarlato V. (2010). Built shallow to maintain homeostasis and persistent infection: insight into the transcriptional regulatory network of the gastric human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000938 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielli A., Roncarati D., Delany I., Chiarini V., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (2006). In vivo dissection of the Helicobacter pylori Fur regulatory circuit by genome-wide location analysis. J. Bacteriol. 188 4654–4662. 10.1128/jb.00120-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. S., Flannery E. L., Mobley H. L. (2006). Helicobacter pylori HP1512 is a nickel-responsive NikR-regulated outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 74 6811–6820. 10.1128/iai.01188-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany I., Spohn G., Pacheco A. B., Ieva R., Alaimo C., Rappuoli R., et al. (2002). Autoregulation of Helicobacter pylori Fur revealed by functional analysis of the iron-binding site. Mol. Microbiol. 46 1107–1122. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany I., Spohn G., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (2001). The Fur repressor controls transcription of iron-activated and -repressed genes in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 42 1297–1309. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz P., Gerlach G., Beier D. (2002). Identification of target genes regulated by the two-component system HP166-HP165 of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184 350–362. 10.1128/jb.184.2.350-362.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donczew R., Makowski L., Jaworski P., Bezulska M., Nowaczyk M., Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J., et al. (2015). The atypical response regulator HP1021 controls formation of the Helicobacter pylori replication initiation complex. Mol. Microbiol. 95 297–312. 10.1111/mmi.12866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst F. D., Bereswill S., Waidner B., Stoof J., Mader U., Kusters J. G., et al. (2005a). Transcriptional profiling of Helicobacter pylori Fur- and iron-regulated gene expression. Microbiology 151 533–546. 10.1099/mic.0.27404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst F. D., Kuipers E. J., Heijens A., Sarwari R., Stoof J., Penn C. W., et al. (2005b). The nickel-responsive regulator NikR controls activation and repression of gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 73 7252–7258. 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7252-7258.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foynes S., Dorrell N., Ward S. J., Stabler R. A., Mccolm A. A., Rycroft A. N., et al. (2000). Helicobacter pylori possesses two CheY response regulators and a histidine kinase sensor, CheA, which are essential for chemotaxis and colonization of the gastric mucosa. Infect. Immun. 68 2016–2023. 10.1128/IAI.68.4.2016-2023.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinaga R., Nakazawa T., Shirai M. (2001). Allelic exchange mutagenesis of rpoN encoding RNA-polymerase sigma54 subunit in Helicobacter pylori. J. Infect. Chemother. 7 148–155. 10.1007/s101560100027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy J. A., Radin J. N., Cullen T. W., Chazin W. J., Skaar E. P., Trent M. S., et al. (2015). Helicobacter pylori resists the antimicrobial activity of calprotectin via lipid A modification and associated biofilm formation. mBio 6:e1349-15 10.1128/mBio.01349-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancz H., Censini S., Merrell D. S. (2006). Iron and pH homeostasis intersect at the level of Fur regulation in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 74 602–614. 10.1128/IAI.74.1.602-614.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley K. P., Gaddy J. A. (2015). Metalloregulation of Helicobacter pylori physiology and pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 6:911 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. G., Hinds F. E., Beckhouse A. G., Kolesnikow T., Hazell S. L. (2002). Resistance to hydrogen peroxide in Helicobacter pylori: role of catalase (KatA) and Fur, and functional analysis of a novel gene product designated ‘KatA-associated protein’, KapA (HP0874). Microbiology 148 3813–3825. 10.1099/00221287-148-12-3813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Benedik M. J., Wood T. K. (2012). Antitoxin DinJ influences the general stress response through transcript stabilizer CspE. Environ. Microbiol. 14 669–679. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02618.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. L., Cheng H. H., Hsieh W. C., Tsai Z. T., Tsai H. K., Chu C. H., et al. (2015). The CrdRS two-component system in Helicobacter pylori responds to nitrosative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 97 1128–1141. 10.1111/mmi.13089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn C. E., Charkowski A. O., Willis D. K. (2008). Evaluation of isolation methods and RNA integrity for bacterial RNA quantitation. J. Microbiol. Methods 75 318–324. 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josenhans C., Niehus E., Amersbach S., Horster A., Betz C., Drescher B., et al. (2002). Functional characterization of the antagonistic flagellar late regulators FliA and FlgM of Helicobacter pylori and their effects on the H. pylori transcriptome. Mol Microbiol 43 307–322. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S., Karim A., Iqbal S. (2009). Helicobacter urease: niche construction at the single molecule level. J. Biosci. 34 503–511. 10.1007/s12038-009-0069-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N., Marcus E. A., Wen Y., Weeks D. L., Scott D. R., Jung H. C., et al. (2004). Genes of Helicobacter pylori regulated by attachment to AGS cells. Infect. Immun. 72 2358–2368. 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2358-2368.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Yin N., Liu H., Pei J., Lai L. (2016). Novel inhibitors of toxin HipA reduce multidrug tolerant persisters. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7 449–453. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh J. T., Gupta S. S., Friedman D. B., Krezel A. M., Cover T. L. (2010). Analysis of protein expression regulated by the Helicobacter pylori ArsRS two-component signal transduction system. J. Bacteriol. 192 2034–2043. 10.1128/JB.01703-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E., Shakespeare L. J., Jorgensen M. G., Gerdes K. (2011). Bacterial persistence by RNA endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 13206–13211. 10.1073/pnas.1100186108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Marshall B. J., Warren J. R. (1984). Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1 1311–1315. 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M. Q., Fortunato A. S., Rodrigues W. P., Partelli F. L., Campostrini E., Lidon F. C., et al. (2017). Selection and validation of reference genes for accurate RT-qPCR data normalization in Coffea spp. under a climate changes context of interacting elevated [CO2] and temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 8:307 10.3389/fpls.2017.00307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee D. J., Langford M. L., Watson E. L., Carter J. E., Chen Y. T., Ottemann K. M. (2005). Colonization and inflammation deficiencies in Mongolian gerbils infected by Helicobacter pylori chemotaxis mutants. Infect. Immun. 73 1820–1827. 10.1128/iai.73.3.1820-1827.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell D. S., Goodrich M. L., Otto G., Tompkins L. S., Falkow S. (2003a). pH-regulated gene expression of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 71 3529–3539. 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3529-3539.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell D. S., Thompson L. J., Kim C. C., Mitchell H., Tompkins L. S., Lee A., et al. (2003b). Growth phase-dependent response of Helicobacter pylori to iron starvation. Infect. Immun. 71 6510–6525. 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6510-6525.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C., Bahlawane C., Aubert S., Delay C. M., Schauer K., Michaud-Soret I., et al. (2011). Hierarchical regulation of the NikR-mediated nickel response in Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 7564–7575. 10.1093/nar/gkr460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehus E., Gressmann H., Ye F., Schlapbach R., Dehio M., Dehio C., et al. (2004). Genome-wide analysis of transcriptional hierarchy and feedback regulation in the flagellar system of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 52 947–961. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi N., Yuasa H., Tanaka S., Sawa H., Miura M., Matsui A., et al. (2008). Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 1003–1008. 10.1073/pnas.0711183105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olekhnovich I. N., Vitko S., Chertihin O., Hontecillas R., Viladomiu M., Bassaganya-Riera J., et al. (2013). Mutations to essential orphan response regulator HP1043 of Helicobacter pylori result in growth-stage regulatory defects. Infect. Immun. 81 1439–1449. 10.1128/IAI.01193-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olekhnovich I. N., Vitko S., Valliere M., Hoffman P. S. (2014). Response to metronidazole and oxidative stress is mediated through homeostatic regulator HsrA (HP1043) in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 196 729–739. 10.1128/JB.01047-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panthel K., Dietz P., Haas R., Beier D. (2003). Two-component systems of Helicobacter pylori contribute to virulence in a mouse infection model. Infect. Immun. 71 5381–5385. 10.1128/iai.71.9.5381-5385.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonnet J., Friedman G. D., Vandersteen D. P., Chang Y., Vogelman J. H., Orentreich N., et al. (1991). Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 325 1127–1131. 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflock M., Bathon M., Schar J., Muller S., Mollenkopf H., Meyer T. F., et al. (2007a). The orphan response regulator HP1021 of Helicobacter pylori regulates transcription of a gene cluster presumably involved in acetone metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 189 2339–2349. 10.1128/JB.01827-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflock M., Finsterer N., Joseph B., Mollenkopf H., Meyer T. F., Beier D. (2006). Characterization of the ArsRS regulon of Helicobacter pylori, involved in acid adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 188 3449–3462. 10.1128/JB.188.10.3449-3462.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflock M., Kennard S., Delany I., Scarlato V., Beier D. (2005). Acid-induced activation of the urease promoters is mediated directly by the ArsRS two-component system of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 73 6437–6445. 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6437-6445.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflock M., Muller S., Beier D. (2007b). The CrdRS (HP1365-HP1364) two-component system is not involved in ph-responsive gene regulation in the Helicobacter pylori strains 26695 and G27. Curr. Microbiol. 54 320–324. 10.1007/s00284-006-0520-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich O. Q., Merrell D. S. (2013). The ferric uptake regulator of Helicobacter pylori: a critical player in the battle for iron and colonization of the stomach. Future Microbiol. 8 725–738. 10.2217/fmb.13.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu A., Karpay A., Israel D. A., Peek R. M., Jr., Krezel A. M. (2005). Helicobacter pylori protein HP0222 belongs to Arc/MetJ family of transcriptional regulators. Proteins 59 303–311. 10.1002/prot.20406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati D., Danielli A., Scarlato V. (2014). The HrcA repressor is the thermosensor of the heat-shock regulatory circuit in the human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 92 910–920. 10.1111/mmi.12600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati D., Danielli A., Spohn G., Delany I., Scarlato V. (2007). Transcriptional regulation of stress response and motility functions in Helicobacter pylori is mediated by HspR and HrcA. J. Bacteriol. 189 7234–7243. 10.1128/jb.00626-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S., Konradt M., Groll C., Scheid P., Hanauer G., Werling H. O., et al. (2004). The spatial orientation of Helicobacter pylori in the gastric mucus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 5024–5029. 10.1073/pnas.0308386101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servetas S. L., Carpenter B. M., Haley K. P., Gilbreath J. J., Gaddy J. A., Merrell D. S. (2016). Characterization of key Helicobacter pylori regulators identifies a role for ArsRS in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 198 2536–2548. 10.1128/JB.00324-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Herzog E., Mcdonald E. M., Crooks A. L., Detweiler C. S. (2015). Physiologic stresses reveal a Salmonella persister state and TA family toxins modulate tolerance to these stresses. PLoS ONE 10:e0141343 10.1371/journal.pone.0141343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn G., Danielli A., Roncarati D., Delany I., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (2004). Dual control of Helicobacter pylori heat shock gene transcription by HspR and HrcA. J. Bacteriol. 186 2956–2965. 10.1128/JB.186.10.2956-2965.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn G., Delany I., Rappuoli R., Scarlato V. (2002). Characterization of the HspR-mediated stress response in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184 2925–2930. 10.1128/JB.184.11.2925-2930.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn G., Scarlato V. (1999a). The autoregulatory HspR repressor protein governs chaperone gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 34 663–674. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn G., Scarlato V. (1999b). Motility of Helicobacter pylori is coordinately regulated by the transcriptional activator FlgR, an NtrC homolog. J. Bacteriol. 181 593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Liu S., Li W., Shan Y., Li X., Lu X., et al. (2013). Proteomic analysis of the function of sigma factor sigma54 in Helicobacter pylori survival with nutrition deficiency stress in vitro. PLoS ONE 8:e72920 10.1371/journal.pone.0072920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry K., Williams S. M., Connolly L., Ottemann K. M. (2005). Chemotaxis plays multiple roles during Helicobacter pylori animal infection. Infect. Immun. 73 803–811. 10.1128/IAI.73.2.803-811.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. J., Merrell D. S., Neilan B. A., Mitchell H., Lee A., Falkow S. (2003). Gene expression profiling of Helicobacter pylori reveals a growth-phase-dependent switch in virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 71 2643–2655. 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2643-2655.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb J. F., White O., Kerlavage A. R., Clayton R. A., Sutton G. G., Fleischmann R. D., et al. (1997). The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388 539–547. 10.1038/41483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura N., Okamoto S., Yamamoto S., Matsumura N., Yamaguchi S., Yamakido M., et al. (2001). Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 345 784–789. 10.1056/NEJMoa001999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet A. H., Kuipers E. J., Stoof J., Poppelaars S. W., Kusters J. G. (2004). Acid-responsive gene induction of ammonia-producing enzymes in Helicobacter pylori is mediated via a metal-responsive repressor cascade. Infect. Immun. 72 766–773. 10.1128/IAI.72.2.766-773.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet A. H., Stoof J., Poppelaars S. W., Bereswill S., Homuth G., Kist M., et al. (2003). Differential regulation of amidase- and formamidase-mediated ammonia production by the Helicobacter pylori fur repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 278 9052–9057. 10.1074/jbc.M207542200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini A., Roncarati D., Danielli A. (2016). The cag-pathogenicity island encoded CncR1 sRNA oppositely modulates Helicobacter pylori motility and adhesion to host cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 73 3151–3168. 10.1007/s00018-016-2151-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini A., Roncarati D., Spinsanti M., Scarlato V., Danielli A. (2014). In depth analysis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island transcriptional responses. PLoS ONE 9:e98416 10.1371/journal.pone.0098416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidner B., Melchers K., Stahler F. N., Kist M., Bereswill S. (2005). The Helicobacter pylori CrdRS two-component regulation system (HP1364/HP1365) is required for copper-mediated induction of the copper resistance determinant CrdA. J. Bacteriol. 187 4683–4688. 10.1128/jb.187.13.4683-4688.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Lo L. F., Maier R. J. (2012). A histone-like protein of Helicobacter pylori protects DNA from stress damage and aids host colonization. DNA Repair 11 733–740. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Maier R. J. (2015). A novel DNA-binding protein plays an important role in Helicobacter pylori stress tolerance and survival in the host. J. Bacteriol. 197 973–982. 10.1128/JB.02489-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wood T. K. (2011). Toxin-antitoxin systems influence biofilm and persister cell formation and the general stress response. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 5577–5583. 10.1128/AEM.05068-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y., Marcus E. A., Matrubutham U., Gleeson M. A., Scott D. R., Sachs G. (2003). Acid-adaptive genes of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 71 5921–5939. 10.1128/iai.71.10.5921-5939.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Inouye M. (2011). Regulation of growth and death in Escherichia coli by toxin-antitoxin systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9 779–790. 10.1038/nrmicro2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of reference gene (HPrrnA16S) under different environmental conditions. Panels show the expression of reference gene during stationary phase in BB + FBS with changes in pH and concentrations of urea, nickel, and iron (A), or in presence of antibiotics (B) or in contact on abiotic and biotic surfaces (C). (-) Indicates the BB + FBS plain (neutral pH with no addition of components). Quantification of expression is showed as copies of HPrrnA16S/μg RNA.

Effect of antibiotics on H. pylori growth. Determination of colony forming units (CFU) of H. pylori 26695 grown during 1 h in presence of antibiotics (Km, Kanamycin; Chloramphenicol, Cm; Tetracycline, Tc).