Abstract

Integrases are a family of tyrosine recombinases that are highly abundant in bacterial genomes, actively disseminating adaptive characters such as pathogenicity determinants and antibiotics resistance. Using comparative genomics and functional assays, we identified a novel type of mobile genetic element, the GInt, in many diverse bacterial groups but not in archaea. Integrated as genomic islands, GInts show a tripartite structure consisting of the ginABCD operon, a cargo DNA region from 2.5 to at least 70 kb, and a short AT-rich 3′ end. The gin operon is characteristic of GInts and codes for three putative integrases and a small putative helix-loop-helix protein, all of which are essential for integration and excision of the element. Genes in the cargo DNA are acquired mostly from phylogenetically related bacteria and often code for traits that might increase fitness, such as resistance to antimicrobials or virulence. GInts also tend to capture clusters of genes involved in complex processes, such as the biosynthesis of phaseolotoxin by Pseudomonas syringae. GInts integrate site-specifically, generating two flanking direct imperfect repeats, and excise forming circular molecules. The excision process generates sequence variants at the element attachment site, which can increase frequency of integration and drive target specificity.

Tyrosine-based site-specific recombinases (TRases) are exceedingly abundant in prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes1,2, carrying out functions as diverse as ensuring proper chromosomal and plasmid segregation, regulating gene expression or determining the life cycle of prophages towards dormancy or cell death3. They are also responsible for the movement of DNA through various types of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as integrons, phages, certain transposons, integrative conjugative elements, and genomic islands1,4. These elements have a significant impact in bacterial evolution by spurring lateral gene transfer, which favours the speciation of bacteria and their adaptation to new ecological niches, either by enhancing their fitness and/or enabling interactions with other organisms4,5,6. For instance, integrons are the major agents for the dissemination of antibiotic multiresistance in Gram-negative bacteria7, whereas integron-like elements are of significance to the transfer of fitness and virulence genes among environmental bacteria8. Likewise, genomic islands are key players in microbial evolution and adaptations that are of medical, agricultural and environmental interest9,10; indeed, many plant and animal pathogenic bacteria carry diverse genomic islands that allow them to more efficiently colonize their hosts and evade control measures, threatening the management of diseases in human settings11.

The bean plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae (Ps) pv. phaseolicola contains a cluster of 23 genes, the Pht cluster, responsible for the biosynthesis of the wide-spectrum antimetabolite toxin phaseolotoxin12,13,14. Besides its relevance as a research model and potential biotechnological applications15, the Pht cluster is of practical significance because it is generally used for the specific detection of this important plant pathogen16. The cluster is embedded into the 38 kb putative pathogenicity island Pht-PAI, whose 5′ end is defined by three genes coding for products with similarities to TRases13,17. The Pht-PAI appears to be mobile, because a nearly identical genomic island has been found syntenically inserted into the genome of certain strains of the kiwiplant pathogen Ps pv. actinidiae13,17. Additionally, homologues of the three putative TRase genes were found in Ps pv. tomato DC3000 and Ps pv. phaseolicola CYL314, integrated into the same genomic location as the Pht-PAI but associated to dissimilar DNA13,17. These correlational data, together with the phylogeny of diverse genes from the Pht cluster, led to the hypothesis that this putative island was possibly first acquired from a Gram-positive bacterium by lateral gene transfer, and later exchanged among P. syringae pathovars13,17,18. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of functional and structural data demonstrating the existence of this putative mobile genomic island, and for assessing its potential impact for the dissemination of virulence genes among P. syringae and other bacteria.

Here, we used comparative genomics and functional assays to study the functionality of the Pht-PAI and its potential mobility. This showed that the Pht-PAI belongs to a new type of MGE, designated GInt, that is widely distributed in diverse bacterial phyla. GInts are characterized by the ginABCD operon, coding for three TRases and a fourth product that are essential for recombination, and can carry up to at least 70 kb of cargo DNA containing genes potentially increasing fitness and virulence.

Results

GInts are a new type of genomic island

The Pht-cluster is included in a genomic island (Pht-PAI) that has been exchanged horizontally among Ps strains, and it is accompanied by three putative TRases (here named genes ginABC) that are associated to dissimilar DNA in different strains13,14,19. We therefore postulated that these putative integrases might then be part of a functional mobile element carrying different cargo DNA.

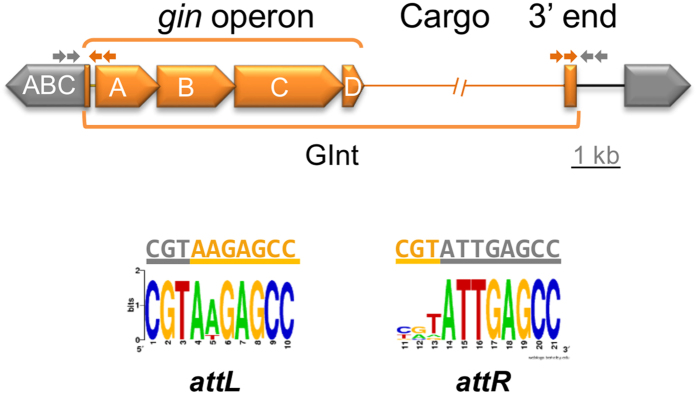

Using blastn, we found many examples among pseudomonads of genomic islands showing the same organization than the Pht-PAI, namely, a tripartite structure consisting of 1) the highly conserved ginABCD operon in the 5′ end; 2) a variable amount of cargo DNA, starting immediately before or after the stop codon of ginD; and 3) a short and poorly conserved 3′ end containing some well-conserved AT-rich sequence stretches (Fig. 1 and Table S1). All these islands inserted into the same chromosomal location, the 5′ end of an ABC transporter gene (PSPPH_4293 in strain 1448A) and are flanked by 10–11 nt direct imperfect repeats, the attL and attR (Fig. 1 and Table S2). Since they show characteristics of novel MGEs (see below), we have collectively designated these elements GInts (Genomic Island with three Integrases),

Figure 1. General structure of GInts.

The GInt element (orange, with bacterial sequences in grey) has a tripartite structure: The highly conserved ginABCD operon, the cargo DNA (broken line), and a 0.2–0.4 kb poorly conserved 3′ end. GInts integrate site-specifically; the GInt carrying the Pht-PAI from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A, and related elements, integrate within a putative ABC transporter gene (PSPPH_4293 in strain 1448A; indicated as ABC). Small grey and orange arrows represent primers for testing excision and circularization. The site-specific integration of GInts generates two direct imperfect repeats (attL and attR) of 10 and 11 nucleotides, which are chimeras of the attI sequence from the GInt (orange letters) and the attB sequence from the bacterial chromosome (grey lettering). The sequence logo was generated from alignments of the att repeats from GInts related to the Pht-PAI (Table S1).

Structural and transcriptional analysis of genes ginABCD

The alleles of genes ginA and ginB from 16 analysed genomes (Table S1) showed significant matches with the catalytic core of phage integrases (families IPR011010, IPR013762 and IPR002104), whereas the alleles of ginC contain domains matching families IPR011010 and IPR013762, or only IPR013762. The structure of the deduced products from ginABC could be modelled using Phyre2, with CRE, XerD or XerC as the closest matching templates. Additionally, Psi-blast multiple alignments of 1000 proteins identified highly conserved residues and the RHRHY motif necessary for integrase function20, although the first arginine is missing in GinC (Fig. S1). No domains were found in GinD using InterProScan, although the Phyre2 structure of the C-terminal end of GinD displays an HLH domain.

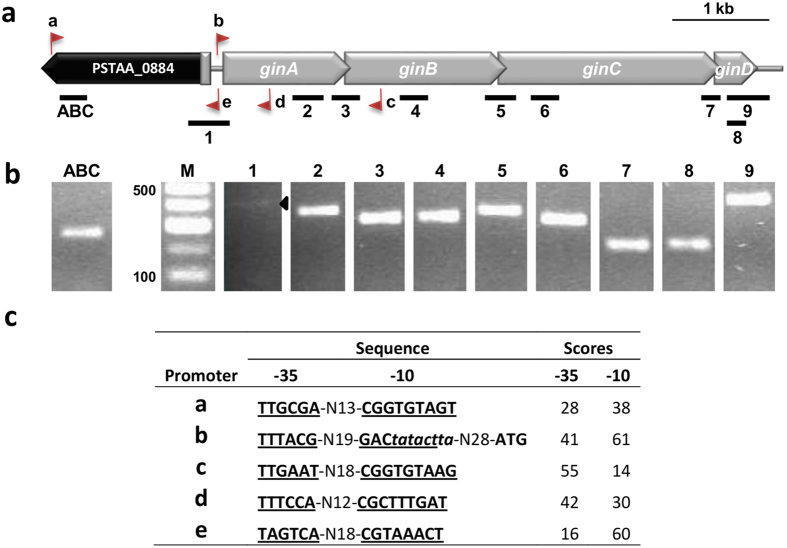

RT-PCR analyses showed genes ginABCD from strain Pst DSM 4166 (Fig. 2A) to be cotranscribed in a polycistronic mRNA, with transcription likely continuing into the cargo DNA (Fig. 2B). Using strand-specific primers for cDNA synthesis, RT-PCR revealed transcription from outside the element towards ginA, and from within ginA towards the ABC transporter (Fig. 2B). The software BPROM predicts appropriate consensus promoters for all these transcripts (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that genes ginABCD constitute an operon that is transcribed from a promoter located within the GInt, upstream of ginA, and from an external bacterial promoter. They also indicate that insertion of the GInt directs the transcription of genes situated 5′ of the element.

Figure 2. RT-PCR analysis of the gin operon from P. stutzeri DSM 4166.

(a) Location of the amplicons observed in RT-PCR experiments. The location and orientation of promoters predicted using the BPROM software is indicated with flags named from a to e. (b) Gel electrophoresis of amplicons from RT-PCR experiments generated using strand-specific primers for each amplicon for cDNA synthesis, as shown in panel a; the black triangle in lane 1 identifies a repetitively faint amplification band. The RT-PCR negative controls produced no amplicons, and are not shown for clarity. M, molecular weight marker in nt. (c) Sequence and score values of −35 and −10 boxes (underlined) of promoters a to e in panel a, as predicted by the BPROM software. A putative Fis binding box is indicated in italics.

GInts excise generating circular intermediates

The mobilization of DNA by integrases involves its excision and the formation of circular intermediates21,22; we therefore tested by nested-PCR the ability of different GInts to form circular structures and to restore an empty attB site in the chromosome (Fig. 1 and Table S2).

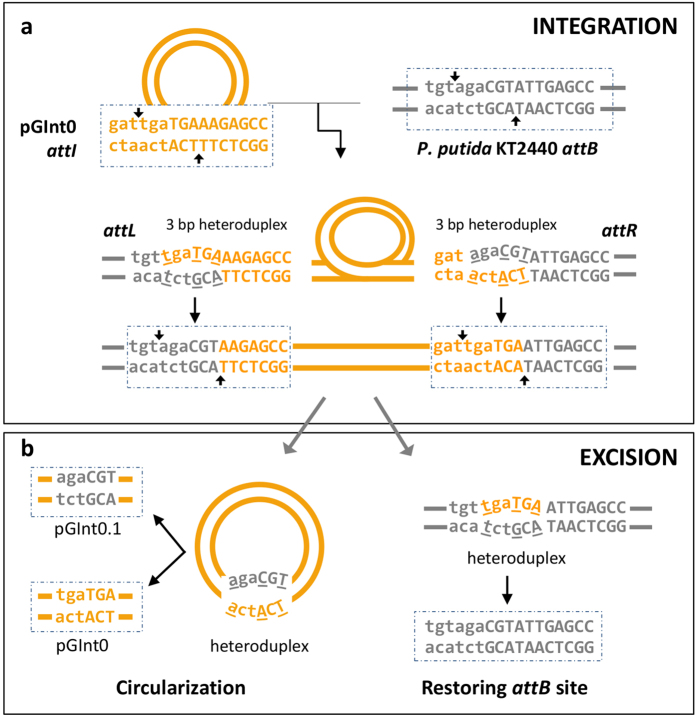

The second round of nested PCR amplifications generated the expected amplicons for the circular intermediate for all tested bacteria (Table S2), although the low PCR yield suggests that it occurs in only a few cells. Additionally, we detected the amplicon for Ps pv. phaseolicola 1448A in the rich medium KB at all time points examined (see Methods), but not in minimal medium or in planta. Remarkably, for Pst DSM 4166 the specific amplicon was already detectable in the first round of PCR (Fig. 3), suggesting that the circularization of the GInt is more frequent in this strain. Similarly, we were able to detect the chromosomal scar corresponding to an empty attB site only in cultures of Ps pv. pisi 1704B, P. cannabina pv. alisalensis ES4326 and Ps pv. tomato DC3000 (Table S2), but not for the remaining strains. These unexpected results suggest that the excision of certain GInts might be replicative, leaving a copy into the attB; might be lethal for the bacterium; or might induce genetic changes in the insertion site. DNA sequence of cloned PCR products for GInt junctions and scars from six different bacteria was as expected by recombination at the defined attL and attR sites, thus confirming the excision of the GInts and the formation of a circular intermediate (Table S2). However, and because the attR and attL sequences are not identical, we observed the reconstruction of different attI sites, some of which appeared to have incorporated a few nucleotides from the bacterial chromosome (Fig. 4 and Table S2). This is compatible with excision of the GInt involving 6 nt staggered cuts and further resolution of 3 nt heteroduplexes by replication or mismatch repair23. Likewise, we observed restored attB sites from Ps pv. pisi 1704B and P. cannabina pv. alisalensis ES4326 differing from the sequence in related bacteria and likely resulting from a resolution of the heteroduplex towards the attI sequence (Fig. 4 and Table S2). We also found deletions of 2 or 6 nt in other cloned attB sites from strain 1704B, although we do not have a satisfactory explanation for their occurrence.

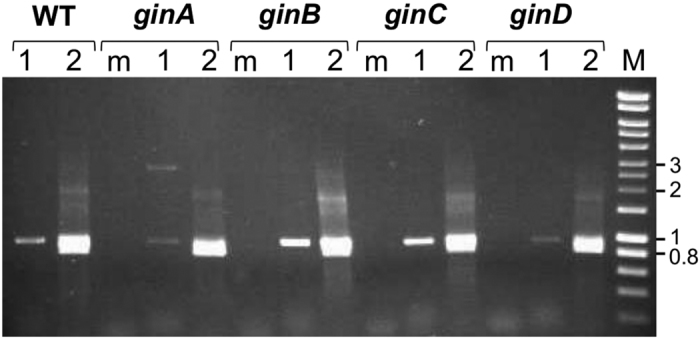

Figure 3. All four ginABCD genes are required for insertion and excision of the GInt.

Generation of a specific amplicon for the circular intermediate of the GInt from P. stutzeri DSM4166, from mutants in each of the ginABCD genes (strains UPN821, -823, -825 and -828), and from their corresponding derivatives complemented in trans with an intact copy of the mutated gin gene. Gel electrophoresis of amplicons generated in the first (1) or second (2) round of nested PCR analyses for the wild type and complemented mutant strains, or in the second round for mutant strains (m). M: HyperLadder I molecular marker (Bioline, Singapore), in kb.

Figure 4. Proposed mechanisms for the general integration and excision of GInts.

As a model that fits the observed sequence changes in circular molecules (see Table S2), the cartoon shows the integration and excision of the artificial GInt pGInt0 (orange) into the genome of P. putida KT2440 (grey), with boxed sequences observed by sequencing of reaction products. (a) Gin proteins likely catalyse 6 nt staggered cuts (vertical arrows) at both attI and attB sites, resulting in the generation of hybrid attL and attR sites upon integration of pGInt0; these are resolved in the cell likely by replication or mismatch repair. Heteroduplexes are shown as curved sequences with differing nucleotides underlined. (b) Excision of the element likely involves 6 nt staggered cuts within attL and attR sites (shown in panel a), with the concomitant circularization of pGInt0 and generation of hybrid restored attI and attB sites. Repair of heteroduplexes might recreate the original attI and attB sequences or introduce nucleotide changes, depending of which sequence (from the GInt or from the bacterium) is used as template for repair. The generation of alternative attB sites upon excision was not observed in the limited sample sequenced from strain KT2440, but it occurred after excision of GInts in other strains (Table S2).

GInts are exchanged interspecifically

Ps pv. phaseolicola and Ps pv. actinidiae contain nearly identical Pht-PAI islands, although they are assigned to different species13,17,24, suggesting that GInts are mobilized among bacterial populations. However, despite numerous attempts, we were unable to demonstrate the transfer of GInts from Ps pv. phaseolicola 1448A and Pst DSM 4166 to strains of Ps pv. syringae (see Methods), indicating that either our experimental conditions were not conducive for transfer or that its frequency is lower than our detection threshold.

To examine horizontal mobility, we compared the phylogenies of GInts and host strains. As expected, the phylogeny of ginA (Fig. S2), and remaining gin genes (data not shown), was not congruent with the MLST-based phylogeny for bacterial strains24,25, indicating that GInts are frequently subjected to horizontal transfer.

Functional analysis of GInts

To perform functional studies of these mobile elements we synthesized pGInt0, a minimal self-contained GInt derived from Pst DSM4166 and cloned in a suicide vector, which serves as cargo DNA and confers Kmr.

We were able to transfer pGInt0, by electroporation, to strains P. fluorescens SBW25, P. putida KT2440 and Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158, routinely obtaining up to 1.1 ± 0.5 × 103 Kmr transformants μg−1 DNA. PCR analysis of at least 10 independent Kmr clones per strain indicated that, as expected, pGInt0 integrated site-specifically into the ABC transporter homolog (locus_tag PFLU5327, PP_0674, and PSYRMG_12240, respectively), occupying the previously empty attB site and producing the chimeric attL and attR sequences (Fig. 4 and Table S2). These results demonstrate that pGInt0 serves as a closed, minimal circular intermediate substrate, with all the genetic information needed for integration. PCR amplification of several independent clones of these three strains generated the specific amplicon for the circular molecule in all cases, but the chromosomal scar only in clones from P. putida KT2440 and Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158. Additionally, cell lysates from these transformants routinely yielded thousands of Kmr colonies upon electroporation into E. coli, and the resulting clones contained autonomous plasmids with EcoRI and AccI profiles identical to those of pGInt0. These results suggest that pGInt0 is able to integrate and further excise from the chromosome as a circular intermediate.

From our previous results (Table S2), we expected that the pGInt0 excision process would lead to changes in reconstructed attI and attB sites. Therefore, from six independent clones of the three Pseudomonas species, we sequenced four cloned scars from P. putida KT2440 and Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158 and 22 cloned attI sequences. In all cases, the sequence of the scar was identical to the wild type sequence (Fig. 4). Conversely, the sequence of the attI was identical to that of pGInt0 in only 50% of the recovered pGInt0 clones, whereas the remaining clones contained the putative 6 nt overhang identical to the attB (Fig. 4 and Table S2). One of these plasmids was retained and designated pGInt0.1, containing three nt changes and making the attI more similar to the bacterial attB. We observed a tenfold increase in the number of Kmr transformants μg−1 of Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158 when using pGInt0.1 (13.7 ± 2.9 × 103) as compared with pGInt0 (1.1 ± 0.5 × 103), indicating that the degree of identity between attB and attI determines, at least in part, the frequency of integration.

A complete functional gin operon is required for the excision/integration process of GInts

Their high conservation across bacteria (see below), suggests that all ginABCD genes participate in the mobilization of GInts. We thus evaluated the ability of mutants in each gin gene for excision and integration in, respectively, Pst DSM 4166 and pGInt0. Unlike with the wild type strain, we were not able to detect circular intermediates in nested PCR analyses with individual mutants of Pst DSM 4166 in each of the ginABCD genes (Fig. 3). In complementation assays, we detected the circular intermediate in the first round of nested PCR for all the complemented mutants, indicating that circularization capacity was restored (Fig. 3). Likewise, transformation of Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158 with mutant plasmids pGInt0A, -B, -C and -D did not yield any Kmr clone, although the complemented mutants yielded 10 to 80 Kmr transformants μg DNA−1. Together, our results indicate that all four genes from the ginABCD operon are essential for excision and integration of GInts.

Bacterial species and strains contain diverse families of GInts

Blastp comparisons soon indicated that bacterial species could contain two or more ginABCD operons showing low sequence identity. For instance, the GInt containing the Pht-PAI from Ps pv. phaseolicola 1448A (Table S1) and those found in Ps pv. syringae UMAF0158 and Ps pv. myricae AZ84488 (Table S3) likely define three different evolutive families, because their GinABCD deduced products show only 24–40% identity in pair comparisons. Remarkably, and despite their low relatedness, the GInts in the last two strains are inserted into the same genomic location, at the end of a single stranded DNA-binding protein (ssb) gene.

Importantly, the presence of a GInt in a genome does not preclude the acquisition of other GInts that might insert into different genomic locations, and we found frequent instances of strains containing at least two GInts. For example, Ps pv. phaseolicola 1448A contains the Pht-PAI and it also contains two other ginABCD operons (PSPPH_2793-2796 and PSPPH_3741-3744), both with truncations, which are associated to DNA that is not syntenic in related bacteria. However, they are also associated to other mobile elements that hamper the identification of the corresponding GInt element. Likewise, P. aeruginosa PA_D16 also contains two ginABCD operons (A6695_20385-20400 and A6695_21815-21830), which are part of two nearly identical GInts of 40.3 and 35.8 kb that are present in a variety of P. aeruginosa strains. They also show high insertion specificity, and are inserted at the end of a duplicated ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit alpha (A6695_20380 and A6695_21835). In all, our results indicate that bacteria are colonized by a variety of GInts, which can insert at different genomic locations and that do not appear to limit the acquisition of other related or unrelated GInts.

GInts are widely distributed in bacteria

BlastP comparisons of the individual ginABCD products retrieves hundreds of hits from diverse groups of bacteria, the majority of which show less than ca. 35% amino acid identity with the query; although this suggests a potentially wide distribution of these genes, it does not necessarily imply the existence of GInts in other bacteria. To confirm this, we investigated the presence of the gin operon in complete sequenced genomes, because this operon is a distinctive feature of GInts and because other structures of the element are only poorly conserved.

Using the gin operon from Pst DSM 4166 as a query sequence (see Methods), we retrieved many putative homologues distributed among Alpha-, Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria as well as from the closed genome of the Verrucomicrobia Opitutus terrae PB90-1 (see examples in Table S3). Using the ginABCD products from Opitutus terrae as a blastp query, we found further examples of gin operons in the Phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (examples in Table S3). Although we have not tried to be exhaustive in our search, these results clearly show that the ginABCD operon is widely distributed among very different bacterial phyla. Indeed, it is feasible that this operon (and, hence, GInts) might appear in other bacterial groups that we are not detecting because of the inherent limitations of our search, derived in part from the low sequence conservation of the gin operons.

From all these gin operons, we chose eleven from different species to analyse the existence of identifiable GInts (Table S3). As deduced from genome comparisons among phylogenetically related strains, the gin operon was part of a GInt, associated to a cargo DNA of variable size (2.5–70 kb), and was flanked by direct imperfect repeats of 10–17 nucleotides. Six of these GInts were integrated within the same ssb gene homolog (Table S3), with the attL overlapping the end of the gene without altering the corresponding product. This is remarkable because the amino acid identity levels among their corresponding GinABCD sequences, in Blast comparisons, are lower than 35%, indicating that distantly related GInts might show identical insertion specificity.

GInts contain very diverse cargo DNA

To investigate the origin of the cargo DNA, we analysed 20 complete GInts, 13 of which are from pseudomonads (Tables S1 and S4). The amount and type of DNA found is highly variable (Table S4), suggesting that GInts are very dynamic elements. In general, the closest homologues for the majority of genes in the cargo DNA was found in strains from the same or related species (Fig. S3, Table S4), indicating that GInts capture genes preferentially from phylogenetically related bacteria. The cargo DNA consists mainly of complete CDSs that in many cases were found in groups of three or more, in regions that were syntenic in other bacteria, conferring specific functions (Table S4). Thus, the acquisition of a GInt could potentially associate to an adaptive advantage for its bacterial host. Some examples of relevant types of cargo DNA are virulence genes such as the T3SS effector genes hopAZ1 (locus_tag PMA4326_RS23760) and hopBD1 (locus_tag PMA4326_RS23770), from the crucifer pathogen P. cannabina pv. alisalensis ES4326, which likely participate in virulence and modulate host specificity26. Another type are gene clusters conferring resistance to antibacterials, including aminoglycosides, quaternary ammonium compounds, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, tetracycline, sulphonamides, copper, and mercury, such as those found in the important human pathogen P. aeruginosa (Table S4). The Pht-PAI is an extreme example of GInts acquiring complex cargo DNA, containing a cluster of 22 genes involved in the biosynthesis of the modified tripeptide phaseolotoxin14 (Table S4). Addiction modules, such as DNA restriction and modification systems (Table S4), were also often found in these elements likely favouring their fixation in the host genome. These data indicate that the cargo DNA of GInts may carry out complex functions that would probably allow for the quantum-leap evolution of the acquiring bacteria.

Discussion

Here we described a novel type of mobile genetic element, the GInt, defined by a four-gene operon (ginABCD), coding for three TRases and a hypothetical protein, all of which are essential for mobilization. GInts are inserted as genomic islands of up to at least 76 kb in the genomes of many bacterial groups, showing a high specificity of insertion; they excise as circular intermediates, preferentially distributing within the harbouring bacterial clade, and often contain genes coding for adaptive characters, such as antibiotic resistance or virulence, and clusters of genes involved in complex phenotypes.

GInts display a tripartite structure, with the ginABCD operon delimiting the 5′ end as their defining characteristic feature (Fig. 1). The deduced products of ginABC contain typical structural and catalytic domains of TRases (Fig. S1), although GinC lacks some of them and it is often annotated in genomes as a hypothetical protein. Gene ginD does not show any conserved domain in an InterPro search, but modelisation with Phyre2 predicts a possible helix-loop-helix C-terminal domain. However, GinD shows low but significant identity with TnpC (not shown), which stimulates integration and determines orientation of the site-specific transposon Tn554 and similar elements27,28; therefore, it is plausible that GinD might carry a similar function during the integration of GInts. Nevertheless, given the low frequency of insertion of GInts, it would be challenging to show whether or not GinD displays a similar behaviour to that of TnpC. Most other MGEs usually code for only one or two integrases, although for recombination they might require the participation of host factors, such as IHF and Fis3, which can carry a variety of functions. Consequently, GInts are the paradigm of a new type of MGE requiring for their mobility three integrases and an additional product that are encoded for by the element. This supports the idea that the involvement of several adjacent integrases for function might be more common than previously thought, because elements containing integrases arranged in tandem or trios are predominant in certain proteobacteria1,8,29,30. As it is common for other MGEs5, it is feasible that one or more of the integrases from the ginABCD operon also participate in the acquisition of foreign DNA by GInts, although there is currently no empirical evidence for this function.

The 3′ terminal end of GInts is only poorly conserved, and we did not identify any common feature that could be involved in self-recognition for integration and excision. However, all elements are bordered by short (at least 10–11 nt) imperfect repeats (attL and attR; Fig. 1) that are hybrid sequences from the GInt attI and the bacterial attB (Fig. 4). The excision of GInts appears to follow the general process of other elements containing TRases23, involving 6–7 nt staggered cuts at the end of the terminal repeats and circularization of the element. Because the attL and attR are not identical, this generates a heteroduplex that is further repaired, leading to sequence changes in a fraction of the excised molecules (Fig. 4). An immediate consequence of this is that the attI shows a higher sequence identity to the bacterial attB, and we showed that these changes (Table S2) led to an increase of the integration frequency of pGInt0 by an order of magnitude. Therefore, we predict that the integration and excision processes by themselves will ultimately direct the evolution of GInts to a higher host specialization, as we have observed for extant elements. This could also explain the tendency of GInts to capture DNA from bacteria phylogenetically related to its host, as they would preferentially be transferred amongst them.

We demonstrated that GInts excise generating a circular intermediate molecule (Figs 3 and 4; Table S2), although with a low frequency. Nevertheless, the excision of the GInt from Pst DSM4166 cultures could be detected in the first round of a nested PCR (Fig. 3), suggesting that certain bacterial strains could potentially transfer their GInts with a higher frequency than others. Remarkably, we did not detect episome formation in Ps pv. phaseolicola 1448A grown in minimal medium or from populations recovered from bean pods. This was unexpected, because the transfer of diverse mobile genetic elements occurs at higher frequencies during the interaction of several pathogens with their eukaryotic hosts31,32,33. However, it is possible that circularization does occur in planta, but at a frequency below the detection limits of our experimental setup. Our phylogenetic analyses (Fig. S2) and previous works12,13 clearly established that GInts are being horizontally transferred among bacterial populations. However, we were unable to demonstrate the horizontal transfer of the Pht-PAI from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A and the GInt from Pst DSM 4166 to two strains of P. syringae pv. syringae, either in vitro or during the interaction with a plant host. The horizontal transfer of genomic island PPHGI-1 from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola occurs by transformation in planta, but not in vitro, and with a very low frequency31. If transformation frequencies of GInts are similar, it is possible that they occur only rarely, mostly taking into account their low excision frequencies. Another possibility is that GInts are mobilized by transduction, as it occurs with many other genomic islands34,35.

In general, GInts appear to have a very high insertion specificity, and we identified only a few genomic locations where they could be found. Interestingly, several unrelated GInt elements insert either at the beginning (e.g., Chrysobacterium artocarpi UTM-3) or, preferentially, at the end of an ssb gene (Table S3). This is remarkable given the very low identity among these GInts and among the different ssb homologs, and suggests that the signals for recognition of the insertion sites, both in the GInt and in the genome, might be highly conserved. Additionally, insertion of a GInt probably does not cause the complete inactivation of the target genes. In certain cases, GInts localize to intergenic regions or at the 3′ end of genes, leading to a change of variable length in the C-terminal end of the corresponding product. In other cases, they insert at the 5′ end of the target gene, predictably preventing its expression. However, we have shown that the GInt from Pst DSM 4166 contains a promoter within the gin operon and directed outwards, leading to the expression of the ABC transporter gene located 5′ of the GInt (Fig. 2), and it is likely that this is a general feature of GInts. Indeed, certain other MGEs contain promoters that activate surrounding genes36, which can minimize mutational damage and also facilitate adaptability by promoting gene expression37.

GInts carry a variable amount of cargo DNA, with three significant properties: it originates mostly from phylogenetically related species, it can incorporate a large amount of contiguous DNA, and often includes post segregational killing systems that may favour their maintenance, as it also occurs with plasmids and other MGEs38. The analysis of GInts from Pseudomonas related to that containing the Pht-PAI, showed that more than 50% of the cargo DNA of each element had the closest homolog in this bacterial group (Fig. S3). This is not surprising if we take into account that GInts also tend to distribute preferentially within their harbouring bacterial group, a behaviour that is common to other MGEs, such as plasmids39 and insertion sequences40. We do not have a satisfactory explanation for the tendency of GInts to capture large stretches of DNA, which often code for complex functions such as the biosynthesis of phaseolotoxin14, allowing for the quantum-leap evolution of the acquiring bacteria and favouring the acquisition of GInts. GInts might also acquire DNA that is particularly suitable for the hosting bacterium; for instance, we have found GInts carrying several genes for resistance to antibiotics in P. aeruginosa, one of the most relevant bacterial human pathogens.

Blastp searches revealed the presence of GInts in very different bacterial phyla, including Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia and Proteobacteria (Table S3). Our search did not attempt to be exhaustive, and was likely limited by the very low conservation of GInt sequences across bacterial groups; it is therefore likely that GInts have a wider distribution in Bacteria, although we did not find evidences for their presence in Archaea. This wide distribution, together with their ability to carry large DNA fragments coding for complex functions and adaptive characters, make GInts relevant agents in the horizontal distribution of genes and the evolution of bacteria.

Methods

Strains and growing conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are described in Table S5. E. coli was cultured at 37 °C in Luria Bertani medium and Pseudomonas strains at 25–28 °C in either King’s medium B (KB) or mannitol-glutamate (MG) agar, which does not support the growth of E. coli. When necessary, media were amended with supplements at the following final concentrations (in μg mL−1 or % w/v): ampicillin, 100; kanamycin, 50; gentamicin, 10; spectinomycin, 200; streptomycin, 50; sucrose, 5%, and arabinose, 0.5%. Selection for copper resistance was carried out in medium MG plus CuSO4·5H2O at a final concentration of 200 μg mL−1 (0.8 mM).

Standard molecular techniques

Genomic DNA was purified using a DNA isolation kit (Jet Flex, Genomed, Germany). For sequencing, amplicons were purified using the PCR Extract Mini Kit (5 PRIME Inc.) and nucleotide sequences determined at Macrogen (Seoul, Korea). Primer pairs (see Table S6) were designed using Primer3 software41, and amplifications were carried out using a Taq DNA polymerase (Biotaq, Bioline Ltd., London) or a high-fidelity mix (PrimeSTAR HS, Takara). When necessary for site directed mutagenesis, we used the Smr/Spr cassette from pHP45Ω or the Gmr cassette from pJQ200SK amplified by PCR with specific primers that contained the desired terminal restriction sites for disruption cloning (Table S6).

For functional analyses, the gin genes in Pst DSM 4166 and in pGInt0 were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis. Non-polar mutations were introduced by filling-in unique restriction sites internal to the CDSs or by digestion with enzymes cutting twice in the CDS followed by religation, with the concomitant change in the reading frame. Enzymes used for mutagenesis of Pst DSM 4166 genes were: ginA, AccI; ginB, SacI; ginC, EcoRI; for pGInt0: ginA, NcoI, resulting in the deletion of 657 nt; ginB, AvrII; ginC, SexAI. Gene ginD was disrupted by insertion of the Gmr cassette, in strain DSM 4166, or with the Smr/Spr cassette, in pGInt0, in the single StuI site occurring in this gene. When necessary, mutant DNA was exchanged into strain Pst DSM 4166 using pK18mobsacB. Complementation of mutants was done in trans using individual gin genes amplified with specifically designed primers (Table S6), cloned under control of the PBAD promoter into pJN105. These clones were then transferred to the corresponding mutant and GInt excision examined in culture medium containing 0.5% arabinose, essentially as described42. Strain UPN828 (ginD::Gmr) was complemented with a wt copy of ginD inserted alongside the mutant copy.

Analysis of the circularization and transfer of GInts

We followed a nested PCR procedure to evaluate excision and circularization of GInts and pGInt0, but using primers specific for each GInt because of sequence divergence. We used specific outward primers annealing close to the putative ends of each element to test for circularization, and specific primers outside of the element, and directed inwards, to amplify the scar left after excision (see Fig. 1 and Table S6). To test this in axenic cultures, 100 μl samples of KB cultures growing at 28 °C with shaking were taken after 6, 24, 48, 72 or 98 hours of incubation, mixed with 400 μl of sterile distilled water, boiled for 10 minutes and centrifuged. To evaluate circularization of the Pht-PAI in planta, a disc from an inoculated bean leaf or pod was cut with a n° 4 cork borer at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 days post-inoculation and was homogenized in sterile ¼ strength Ringers solution, before purifying the DNA for PCR as described by Llop et al.43. The first PCR round was carried out in a final volume of 12.5 μl with 2.5 μl of cell lysates from liquid cultures or 0.5 μl of purified DNA from plants; 2.5 μl of the resulting PCR was used as template for a 25 μl second round nested PCR. Experiments were repeated at least three independent times. Five to twenty independently cloned PCR products were sequenced for each combination of type of amplicon and strain.

To evaluate the transfer of GInts from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A and Pst DSM 4166 to two strains of P. syringae pv. syringae, we constructed derivatives containing an antibiotic resistance cassette within their cargo DNA. UPN779 derives from strain 1448A after the Smr/Spr cassette was inserted in the NruI site immediately 3′ of PSPPH_4320. UPN816 derives from DSM 4166 and contains the Smr/Spr cassette replacing a 450 nt HincII fragment internal to PSTAA_0898, a type I restriction-modification system subunit R. We co-inoculated in KB, as donor:receptor, strains UPN779:B728a and UPN816:UPN853. After overnight growth at 25 °C with shaking, we plated serial dilutions of the UPN779:B728a culture on MG + Cu + Sp and MG + Sm + Sp, to select for B728a clones that had acquired the Pht-PAI, and of the UPN816:UPN853 culture on KB + Sp + Km, to select for UPN853 that had acquired the GInt. Since both strains UPN779 and B728a are pathogens of bean, we also tested transmission in planta. Inoculations and incubation of plant material were carried out essentially as described44. For co-inoculation, equal volumes of cell suspensions of strains UPN779 and B728a adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 (approximately 5 × 107 colony-forming units mL−1) were mixed and injected subepidermically on fresh bean pods (cv. Helda), which were deposited over moist filter paper in a plastic box with a hermetic lid. After incubation at room temperature, disks were removed from the inoculated area after 1, 2 and 4 days post-inoculation using a cork borer (no. 4), thoroughly homogenized as above and serial dilutions were plated onto selective media. Experiments to evaluate transfer of GInts were repeated at least six independent times.

Construction and transfer of pGInt0

pGInt0 is an artificial construction mimicking the putative circular intermediate of the GInt from Pst DSM 4166, except that the cargo DNA has been replaced by the cloning vector pUC57-Kan (accession no. JF826242), which cannot replicate in Pseudomonas. It was synthesized by GeneScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and it consists of the last 481 nt from the 3′ end of the GInt followed by the first 5,802 nt of the 5′ end (coordinates 983899–984379 joined to 960530–966331, from accession no. CP002622), cloned in the polylinker of pUC57-Kan in the orientation opposite to the Plac promoter. Except for the relative orientation of the gin operon and the 3′ end, and a nucleotide change to eliminate an EcoRI site internal to ginC made to facilitate further manipulations, the sequence of the insert from pGInt0 is identical to that of strain DSM 4166.

Integration of pGInt0 in Pseudomonas was analysed by electroporating plasmid DNA purified from E. coli by alkaline lysis: since pGInt0 is cloned in a suicide vector for Pseudomonas, the Kmr clones resulting from transformation must contain an integrated copy of the artificial GInt. Integration into the canonical attB was analysed by PCR (Table S6).

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

DNA-free RNA was obtained from bacterial cultures grown overnight in KB using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche Diagnostics) and Ambion TURBO DNA-free Kit (Life Technologies). The concentration and purity of RNA was determined spectrophotometrically, and its integrity confirmed by electrophoresis in agarose gels. cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the ImProm-II reverse transcriptase system (Promega), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Both random hexanucleotides (Promega) and primers specific for sense and antisense transcripts in the gin operon were used for the reaction (Table S6). Reverse transcription was carried out at 25 °C for 5 min for primer annealing, 60 minutes at 42 °C for reverse transcription, and 15 minutes at 70 °C for enzyme inactivation. PCR amplification was carried for 30 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s) plus a final extension step of 6 min at 72 °C. Control reactions included PCR amplification of RNA subjected to a reverse transcription reaction lacking reverse transcriptase, to verify the absence of contaminating DNA; amplification of purified DNA, to verify the reaction conditions, and amplification of an internal fragment of gene gyrB, to confirm the synthesis of cDNA.

Bioinformatics

Partial or complete sequences of rpoD, gyrB, acnB, gap1, gltA and gin genes were obtained directly from the NCBI databases. Sequences of rpoD, gyrB, acnB, gap1 and gltA were concatenated and treated as a single sequence containing 6,283 nt. Multiple-sequence alignments using Muscle, determination of the optimal nucleotide substitution model and phylogenetic tree construction were done using MEGA645. Trees were constructed with Maximum likelihood methods, using the General Time Reversible model, and confidence levels of the branching points were determined using 500 bootstraps replicates. Searches for sequence similarity against the NCBI databases were done using the BLAST algorithms46. Alignments were done using the Needle and T-Coffee tools at the EMBL site (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/services). Sequence logos were created with WebLogo 347. Genome and nucleotide sequences were visualized and manipulated using the Artemis genome browser and Blast comparisons using ACT48. Promoters were predicted using the online BPROM server (http://www.softberry.com)49. Prediction of protein structure was done using the Phyre2 web server (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2)50. To search for homologues of the ginABCD operon, we proceed to an extensive and very permissive in silico survey within complete prokaryotic genomes. We considered that a genome harbours a gin operon homolog if it contains, using BlastP with an E-value cut-off threshold of 0.1, three consecutive CDSs whose products are homologous to GinA, GinB and GinC; we excluded GinD from the search because of its small size and because this CDS is not always annotated.

Additional Information

Accession codes: Sequences of the artificial GInt pGInt0 and of the GInt from strain P. syringae pv. phaseolicola CYL314 are deposited in the EMBL under accession numbers LT671993 and LT671994, respectively.

How to cite this article: Bardaji, L. et al. Four genes essential for recombination define GInts, a new type of mobile genomic island widespread in bacteria. Sci. Rep. 7, 46254; doi: 10.1038/srep46254 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Spanish Plan Nacional I + D + i grants AGL2011-30343-C02-02 and AGL2014-53242-C2-2-R, from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), co-financed by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. We are indebted to Cayo Ramos for invaluable suggestions and to Theresa Osinga for her help with the English language.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions L.B. and J.M. conceived the study and designed the experiments; L.B. and M.E. performed the experiments; P.R.-P. and P.M. conceived, designed and executed the strategy for bioinformatics searches; L.B., M.E., P.R.-P., P.M. and J.M. analysed the data and interpreted the results; L.B. and J.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Van Houdt R., Leplae R., Lima-Mendez G., Mergeay M. & Toussaint A. Towards a more accurate annotation of tyrosine-based site-specific recombinases in bacterial genomes. Mobile DNA 3, 6, doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-3-6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram M. et al. An overview of tyrosine site-specific recombination: From an Flp perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 3, doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0021-2014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindley N. D. F., Whiteson K. L. & Rice P. A. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 567–605, doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073908 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost L. S., Leplae R., Summers A. O. & Toussaint A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. W., Vinatzer B., Arnold D. L., Dorus S. & Murillo J. The influence of the accessory genome on bacterial pathogen evolution. Mob. Genet. Elements 1, 55–65, doi: 10.4161/mge.1.1.16432 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy S. M., Huang J. & Gogarten J. P. Horizontal gene transfer: Building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 472–482, doi: 10.1038/nrg3962 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambray G., Guerout A. M. & Mazel D. Integrons. Annu. Rev. Genet. 44, 141–166, doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163504 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G. et al. The rulB gene of plasmid pWW0 is a hotspot for the site-specific insertion of integron-like elements found in the chromosomes of environmental Pseudomonas fluorescens group bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2374–2388, doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12345 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrindt U., Hochhut B., Hentschel U. & Hacker J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 414–424 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B. & Leong H. W. Computational methods for predicting genomic islands in microbial genomes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 14, 200–206, doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.05.001 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. W., Johnson L. J., Clarke S. R. & Arnold D. L. Bacterial pathogen evolution: breaking news. Trends Genet. 27, 32–40, doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.10.001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joardar V. et al. Whole-genome sequence analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A reveals divergence among pathovars in genes involved in virulence and transposition. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6488–6498 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genka H. et al. Comparative analysis of argK-tox clusters and their flanking regions in phaseolotoxin-producing Pseudomonas syringae pathovars. J. Mol. Evol. 63, 401–414 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera S. et al. Functional characterization of the gene cluster from Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola NPS3121 involved in synthesis of phaseolotoxin. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2834–2843, doi: 10.1128/JB.01845-06 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Morales A., López-López K. & Hernández-Flores J. L. Current ideas on the genetics and regulation of the synthesis of phaseolotoxin in Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola in Pseudomonas. Virulence and Gene Regulation Vol. 2 (ed Ramos J.-L.) 159–180 (Kluwer Academics/Plenum Publishers, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Schaad N. W., Berthier-Schaad Y. & Knorr D. A high throughput membrane BIO-PCR technique for ultra-sensitive detection of Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Plant Pathol. 56, 1–8 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Murillo J. et al. Variation in conservation of the cluster for biosynthesis of the phytotoxin phaseolotoxin in Pseudomonas syringae suggests at least two events of horizontal acquisition. Res. Microbiol. 162, 253–261, doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.10.011 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada H. et al. A phylogenomic study of the OCTase genes in Pseudomonas syringae pathovars: the horizontal transfer of the argK–tox cluster and the evolutionary history of OCTase genes on their genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 54, 437–457 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell C. R. et al. The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 10181–10186, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1731982100 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainge I. & Jayaram M. The integrase family of recombinases: organization and function of the active site. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 449–456, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01493.x (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn A. M. & Boltner D. When phage, plasmids, and transposons collide: genomic islands, and conjugative- and mobilizable-transposons as a mosaic continuum. Plasmid 48, 202–212 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano N., Muroi T., Takahashi H. & Haruki M. Site-specific recombinases as tools for heterologous gene integration. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92, 227–239, doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3519-5 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeev L., Malanowska K. & Gardner J. F. Challenging a paradigm: the role of DNA homology in tyrosine recombinase reactions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 300–309, doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00038-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull C. T. et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Pseudomonas syringae sensu lato confirms previously described genomospecies and permits rapid identification of P. syringae pv. coriandricola and P. syringae pv. apii causing bacterial leaf spot on parsley. Phytopathology 101, 847–858 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peix A., Ramírez-Bahena M.-H. & Velázquez E. Historical evolution and current status of the taxonomy of genus Pseudomonas. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9, 1132–1147, doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.08.001 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris P. F. et al. Comparative genomics of multiple strains of Pseudomonas cannabina pv. alisalensis, a potential model pathogen of both monocots and dicots. PLoS ONE 8, e59366, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos M. C. & Murphy E. Transposon Tn554 encodes three products required for transposition. EMBO J. 7, 2935–2941 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A. et al. Tn6188 - A novel transposon in Listeria monocytogenes responsible for tolerance to benzalkonium chloride. PLoS ONE 8, e76835, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076835 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker N., Qian H. & Fulthorpe R. R. Phylogeny and organization of recombinase in trio (RIT) elements. Plasmid 70, 226–239, doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.04.003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemme C. L. et al. Lateral gene transfer in a heavy metal-contaminated-groundwater microbial community. mBio 7, e02234–15, doi: 10.1128/mBio.02234-15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell H. C. et al. Bacterial evolution by genomic island transfer occurs via DNA transformation in planta. Curr. Biol. 19, 1586–1590 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Yacoubi B., Brunings A. M., Yuan Q., Shankar S. & Gabriel D. W. In planta horizontal transfer of a major pathogenicity effector gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1612–1621, doi: 10.1128/aem.00261-06 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz T. S. et al. Excision of an unstable pathogenicity island in Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis is induced during infection of phagocytic cells. PLoS ONE 6, e26031 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd E. F., Almagro-Moreno S. & Parent M. A. Genomic islands are dynamic, ancient integrative elements in bacterial evolution. Trends Microbiol. 17, 47–53, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.003 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran P. C., Petty N. K. & Salmond G. P. C. Transduction: host DNA transfer by bacteriophages. In The Encyclopedia of Microbiology (ed Schaechter M.) 666–679 (Elsevier, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mahillon J. & Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 725–774 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podglajen I., Breuil J. & Collatz E. Insertion of a novel DNA sequence, IS1186, upstream of the silent carbapenemase gene cfiA, promotes expression of carbapenem resistance in clinical isolates of Bacteroides fragilis. Mol. Microbiol. 12, 105–114, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00999.x (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta M. & Austin S. Prevalence and significance of plasmid maintenance functions in the virulence plasmids of pathogenic bacteria. Infect. Immun. 79, 2502–2509, doi: 10.1128/iai.00127-11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie C., Garcillán-Barcia M. P., Francia M. V., Rocha E. P. C. & de la Cruz F. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 434–452, doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00020-10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. & de la Chaux N. Distant horizontal gene transfer is rare for multiple families of prokaryotic insertion sequences. Mol. Genet. Genomics 280, 397–408, doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0373-y (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S. & Skaletsky H. J. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers In Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology (eds Krawetz S. & Misene S.) 365–386 (Humana Press, 2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. R. & Fuqua C. Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the l-arabinose-inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene 227, 197–203, doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00601-5 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llop P., Caruso P., Cubero J., Morente C. & López M. M. A simple extraction procedure for efficient routine detection of pathogenic bacteria in plant material by polymerase chain reaction. J. Microbiol. Meth. 37, 23–31, doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00033-0 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yessad-Carreau S., Manceau C. & Luisetti J. Occurrence of specific reactions induced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on bean pods, lilac and pear plants. Plant Pathol. 43, 528–536, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1994.tb01587.x (1994). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A. & Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729, doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W. & Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M. & Brenner S. E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190, doi: 10.1101/gr.849004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver T. et al. Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 24, 2672–2676, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovyev V. & Salamov A. Automatic annotation of microbial genomes and metagenomic sequences in Metagenomics and its applications in agriculture, biomedicine and environmental studies (ed Li R. W.) 61–78 (Nova Science Publishers, 2011).

- Wass M. N., Kelley L. A. & Sternberg M. J. E. 3DLigandSite: predicting ligand-binding sites using similar structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W469–W473, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq406 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.