Abstract

The human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 is important for transactivation of immediate-early (IE) gene expression and for the efficient initiation of virus replication. We have analyzed the properties of pp71 by assaying its effects on gene expression from the genome of in1312, a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) mutant devoid of functional VP16, ICP0, and ICP4. Upon infection of human fibroblasts, in1312-derived viruses are repressed and retained in a quiescent state, but the presence of pp71 prevented the quiescent state from being attained. Reporter gene cassettes cloned into the in1312 genome, in addition to the endogenous IE promoters, remained active for at least 12 days postinfection, and infected cells were viable and morphologically normal. Cells expressing pp71 remained responsive to the HSV-1 transactivating factors VP16 and ICP4 and to trichostatin A. The C-terminal 61 amino acids, but not the LACSD motif, were required for pp71 activity. In addition to preventing attainment of quiescence, pp71 was able to disrupt the quiescent state of in1312 derivatives and promote the resumption of viral gene expression after a lag of approximately 3 days. The results extend the functional analysis of pp71 and suggest a degree of similarity with the HSV-1 IE protein ICP0. The ability to provoke slow reactivation of quiescent genomes, in conjunction with cell survival, represents a novel property for a viral structural protein.

Many herpesviruses utilize virion proteins as transactivators of immediate-early (IE) gene expression to ensure the rapid initiation of productive replication. In the case of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), the well-studied tegument protein VP16 activates IE transcription through specific TAATGARAT elements that are present in all IE promoters (6, 43). For human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), the 559-amino-acid tegument phosphoprotein pp71, encoded by the gene UL82 (9, 42, 51), fulfills an equivalent role, although the mode of action of this protein is not understood in detail.

The transactivating properties of pp71 were first recognized in cotransfection assays. Expression from cytomegalovirus IE promoters on plasmid templates was stimulated by the presence of a plasmid that expressed pp71, and the effect was mediated by sequence elements that bind the cellular transcription factors ATF or AP-1 (33). Dependence on ATF recognition sites was also observed in cotransfection studies that investigated the response of the HCMV US11 promoter in the presence of pp71, although in this case the IE protein IE86 was also present (7). The promoter for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 was activated by pp71, in conjunction with IE86, via Sp1 recognition sites (32). Limited stimulation of endogenous intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression by pp71 alone was also reported in these studies. When HCMV virion DNA was delivered to cells by transfection, the addition of plasmids that expressed pp71 increased the numbers of progeny plaques and the rate of progress of infection (3). This effect could not simply be accounted for by the increased quantities of IE proteins, suggesting that pp71 exerts a more general effect on the transcription of the viral genome. The importance of pp71 for HCMV replication was underscored by the finding that a mutant with a deletion of the UL82 sequences exhibited impaired IE gene expression and a consequent defect in the initiation of productive infection (5).

The protein pp71 localizes to nuclear domain 10 (ND10) intranuclear structures at early times after infection with HCMV and also when introduced into cells by transfection of pp71-expressing plasmids (17, 19, 23, 37). The cell factor Daxx was identified as an interaction partner of pp71 in yeast two-hybrid analyses, and this finding was confirmed by immunoprecipitation studies with intact cells (19, 23). Daxx itself localizes to ND10, probably by virtue of its ability to interact with the major ND10 protein promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) (21). The binding sites on Daxx for PML and pp71 are distinct; thus, it is possible that Daxx is important for the translocation of pp71 to ND10, a site of viral IE transcription (19, 22, 23).

Cell cycle control is altered by pp71 in two ways. The protein accelerates the progress through G1 phase (29) and additionally stimulates the transition from G0 to G1 in resting cells (28). The latter function is achieved through pp71 binding to and promoting the degradation of unphosphorylated retinoblastoma (Rb) family members by a novel proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent mechanism (30). This property of pp71 is mediated by the motif LACSD at amino acids 216 to 220, which is homologous to the LXCXE motif found in viral oncoproteins. The degradation of unphosphorylated Rb family proteins releases the transcription factor E2F and thus restarts the cell cycle.

Our approach to the study of pp71 has relied on the use of HSV-1 mutants, rather than plasmids, as agents to express the protein and also as reporters to measure its activity. Our basic mutant, named in1312, is impaired for the transcription-stimulating activity of VP16, and additionally, the IE proteins ICP0 and ICP4 are rendered nonfunctional by deletion and temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations, respectively (49). Since the three critical HSV-1 transcription factors are inactive, in1312 cannot enter lytic replication. Nonetheless, inserted reporter genes controlled by a strong promoter, such as the HCMV IE element, are expressed transiently in a significant proportion of infected cells (47). The use of in1312 derivatives provides a system in which the activity and regulation of eukaryotic promoters can be determined in the context of a herpesvirus genome in the absence of activation by HSV-1 IE proteins. A derivative of in1312, named in1324, contains the pp71 coding region controlled by the HCMV IE promoter, and this virus was used to investigate the activity of pp71 in a range of cell types (20, 37). Using the in1312 genome as the target to assess pp71 activity, we showed that all strong promoters were activated by the protein regardless of their sequence contents (20, 37). The endogenous HSV-1 IE promoters were also activated, and even the adenovirus VAI gene, which is transcribed by RNA polymerase III, responded to pp71 (20). Thus, when tested using the HSV-1 genome as a template, pp71 did not exhibit promoter sequence specificity, in contrast to the findings in plasmid-based assays, but instead stimulated gene expression in a general manner. The incoming HSV-1 genome may more accurately reflect the properties of the natural target for pp71, the HCMV genome, than do plasmids.

The lack of sequence specificity in the action of pp71 is reminiscent of the properties of the HSV-1 IE protein ICP0, which also stimulates gene expression in a manner that is not dependent on promoter sequence (reviewed in references 11 and 15). This functional similarity was confirmed by the observation that expression of pp71 by infection with in1324 partially complemented the replication defect of an HSV-1 ICP0 null mutant (37). Thus, although pp71 resembles HSV-1 VP16 in being located in the incoming virus particle, its effects are more closely related to those of ICP0.

One of the reasons for interest in multiple HSV-1 mutants, such as in1312 or the multiple IE deletion mutant d109 (53), is the ability of these viruses to be retained in a quiescent state after infection of cultured cells. The absence of IE gene expression ensures that cells survive infection but do not support lytic replication. Although input viral genomes are responsive to transcription factors immediately after infection, they become repressed within the first few hours and, in this quiescent state, are transcriptionally inactive with the genome retained in a nonlinear configuration (16, 24, 25, 41, 48, 53, 54). In some respects the quiescent interaction resembles HSV-1 latency (45). The quiescent genome is considered to be stably repressed, since it is refractory to a wide variety of stimuli that might be expected to provoke the resumption of gene expression, and at present the only known means of preventing or reversing the attainment of the quiescent state is to provide ICP0 (18, 48, 53). A working hypothesis is that the quiescent genome is packaged into an inaccessible chromatin structure that can be disrupted by ICP0.

The study presented here reports the ability of pp71 to induce reporter gene expression from in1312-based mutants for extended periods in cell culture. The results describe novel properties of pp71 and reveal that the quiescent state may not be as stable as supposed on the basis of current information.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

A series of plasmids was constructed for the insertion of sequences into the thymidine kinase (TK) (UL23) locus or the nonessential UL43 locus of in1312. For TK insertions, the plasmid pCP1802 (20) was used as starting point. This plasmid has an insertion, at the SstI site within TK coding sequences, of an oligonucleotide linker that enables open reading frames to be inserted under the control of the HCMV IE promoter (−750 to +1) and transcribed antisense to TK.

For UL43 insertions, the starting point was p35 (35), which contains the HSV-1 genome region from 91610 to 96751 (39). An oligonucleotide linker was cloned in place of the UL43 coding region between BstXI and BamHI sites, introducing XbaI and XhoI sites. An HCMV IE-lacZ-SV40 terminator cassette from pMJ101 (25) was cloned between the XbaI and XhoI sites to yield pCP376. The lacZ coding region of pCP376 was replaced by green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequences derived from pGFPemd (Packard) to yield pAR55.

For deletion of US1 coding sequences, the starting point was plasmid pN2. This consists of the 4,759-bp EcoRI/BamHI fragment of BamHI n, cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pAT153. Plasmid pN2 was linearized by partial digestion with EcoNI, digested with HindIII, and an oligonucleotide duplex of sequence (top strand) 5′-TCGAGGCGACCGGCGGCGACCGTTGCGTGGACCGCTTCCTGCTCGTCGGGTCTAGACCCCCCA was cloned in at the appropriate position. This change reconstructed the inverted short repeats, removed the US1 (ICP22) coding sequences (genome coordinates 132644 to 133904) from the start to 133468, and introduced an XbaI site (underlined). An HCMV IE-lacZ-SV40 terminator cassette was cloned between the introduced XbaI site and an XhoI site at 133522 in the ICP22 coding region. In the resultant plasmid, pCP279, most of the ICP22 coding region was replaced with the lacZ expression cassette.

For UL54 (ICP27) insertions, pMJ151 was the starting point. This plasmid contains the cloned HSV-1 sequences between an EcoRI site (110096) and a PstI site (118666), modified by the insertion of an oligonucleotide linker between BamHI (113322) and HpaI (115766) sites that encompass UL54, thereby deleting the ICP27 coding region. A cassette of HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 (37) was cloned between the BglII and XhoI sites of the inserted oligonucleotide to yield pMJ154. The plasmid used to generate ICP27-expressing cells was pMJ144, which contained an insertion of the ICP27 coding sequences defined by the BamHI (113322) and HpaI (115766) sites specified above, together with a neomycin resistance marker and an additional insertion containing the entire ICP4 coding region and promoter.

For the construction of plasmids with a hybrid HCMV IE/ICP0 promoter, the starting points were pUC18 derivatives that contained the HCMV IE promoter from −750 to +1 (pCP69419) and the ICP0 promoter from −808 to +43 (pCP73625) (25). A 695-bp fragment from −750 to −55 (defined by an HgaI site) of pCP69419 was cloned onto the BstXI site at −424 in the ICP0 promoter of pCP73625, replacing ICP0 sequences between −808 and −424. The resultant plasmid, pCP2483, contained the proximal sequences of the ICP0 promoter, including the functional TAATGARATs, with the majority of the HCMV IE enhancer region upstream. The hybrid promoter was introduced into the UL43 coding sequences upstream of lacZ.

The LAGSD mutation was produced by cleaving a pp71-expressing plasmid with SgrAI and BpmI and introducing a double-stranded oligonucleotide that reconstructed the coding region but converted the LACSD sequence at amino acids 216 to 220 to LAGSD. The oligonucleotide also contained a silent mutation that created an XhoI site to assist cloning. The authenticity of the changes was confirmed by sequencing. The mutated pp71 open reading frame was transferred to pCP43937 (20), a plasmid that contains the HCMV IE-pp71 cassette in the TK coding region. Truncation of pp71 coding sequences was achieved by inserting a terminator oligonucleotide at the KpnI site that covers amino acid positions 499 to 500 of pYFPpp71 (37). Introduction of the oligonucleotide simultaneously deleted the coding region for the C-terminal 61 amino acids. The resultant plasmid was pYFPpp71Δ61. The deleted region was transferred to pCP43937 to yield pMJ135, in which YFPpp71Δ61 is inserted at the TK locus.

Cells.

Human fetal foreskin fibroblast (HFFF2) and BHK-21 cells were propagated as described previously (36, 37). Human osteosarcoma U2OS cells were propagated in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum plus 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per milliliter. A U2OS cell line capable of expressing ICP27 was obtained by transfection of pMJ144 and selection of G418-resistant lines. Three colony-purified lines that complemented the replication defect of an HSV-1 ICP27 null mutant were obtained from 100 screened, and 1 (SCP3) was selected for use. None of the 100 lines complemented an HSV-1 ICP4 null mutant.

Recombinant viruses.

The HSV-1 (strain 17) mutant tsK, which contains a ts mutation in the coding sequences of ICP4, has been described previously (44). The HSV-1 multiple mutant in1312 has a 12-bp insertion in the VP16 coding sequences, a 317-bp deletion that removes the crucial RING domain of ICP0 and disrupts the normal reading frame of the remainder of the coding sequences, and the ts mutation of tsK that inactivates ICP4 at temperatures above 38°C. The construction of in1312 was described previously (49). Recombinant viruses were produced by cotransfection of DNA from in1312 or a derivative into U2OS cells together with linearized plasmid, with subsequent selection at 32°C by one of the following four methods, (i) Viruses with insertions at the TK locus were selected for resistance to acycloguanosine, as described previously (25). In cases where the inserted sequences expressed a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fusion protein, fluorescence was monitored as a rapid means of identifying positive isolates. (ii) For lacZ insertion at the UL43 or US1 locus, positive plaques were identified and purified by overlaying cells with medium containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Noble agar and 300 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) per milliliter and selecting for blue coloration. (iii) For insertion of the HCMV-IE-GFP cassette into UL43, DNA from mutant in1360, which contains HCMV IE-lacZ in UL43, was the starting point. DNA from in1360 was cotransfected with ScaI-cleaved pAR55, and GFP-expressing plaque isolates were selected first by reduced blue staining in the presence of X-Gal and then by observation of fluorescence. In essence, the lacZ coding region of in1360 was replaced by the GFP coding region. (iv) The insertion of YFP-pp71 in place of the ICP27 coding sequences of in1312 was achieved by cotransfection of in1312 DNA with ScaI-cleaved pMJ151 on SCP3 cells, followed by selection and purification of fluorescent plaques. In all cases, DNA from purified plaque isolates was analyzed by Southern hybridization, using probes that distinguished the desired recombinant from the parent virus. Isolates that showed the correct pattern, with no detectable parental virus after long autoradiographic exposures, were propagated in BHK-21 cells. Viruses were also screened by Southern hybridization and plaque assay to confirm that they retained the VP16 insertion, the ICP0 RING deletion, and the ts ICP4 mutations. Mutant viruses were titrated on U2OS cells at 32°C in the presence of 3 mM hexamethylene bisacetamide (38). This procedure gives the “fully complemented ” titer for in1312 derivatives, a value that is 50 to 100 times greater than the titer on BHK cells that we have used in previous studies (20, 36, 37, 49, 50) due to complementation of the ICP0 mutation in U2OS cells (62). The mutants used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

HSV-1 mutants used in the studya

| Mutant | Insertion(s)b |

|---|---|

| in1324 | HCMV IE-pp71 (TK) |

| in1382 | HCMV IE-lacZ (TK) |

| in1360 | HCMV IE-pp71 (TK); HCMV IE-lacZ (UL43) |

| in1374 | HCMV IE-lacZ (UL43) |

| in1310 | HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 (TK); HCMV IE-lacZ (UL43) |

| in0126 | HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 (TK); HCMV IE-lacZ (US1) |

| in0123 | HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 (UL54) |

| in1306 | HCMV/ICP0 hybrid promoter-lacZ (UL43) |

| in1307 | HCMV IE-pp71 (TK); HCMV/ICP0 hybrid promoter-lacZ (UL43) |

| in0121 | HCMV IE-pp71 [LAGSD](TK); HCMV IE-lacZ (UL43) |

| in1316 | HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 (TK) |

| in1317 | HCMV IE-pp71 (TK); HCMV IE-GFP (UL43) |

| in0125 | HCMV IE-YFP-pp71Δ61 (TK); HCMV IE-lacZ (UL43) |

| in1372 | HCMV IE-Cre (TK) |

All mutants were derived from in1312.

The site of insertion is bracketed.

Infection of HFFF2 monolayers.

Cells on 35-mm-diameter plates were infected and maintained at 38.5°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum and with 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per milliliter. The medium was changed every 2 or 3 days. In some cases, monolayers were trypsinized and replated onto fresh 35-mm culture plates or coverslips.

Enzyme assays.

Histochemical detection of β-galactosidase in cell monolayers and assay of β-galactosidase activities of cell extracts using 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate were performed as described previously (25, 48).

Immunofluorescence.

Cultures were trypsinized and seeded onto 13-mm-diameter glass coverslips. Antibodies used were the following: rabbit anti-pp71 (custom synthesized by Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), diluted 1:100; 58S mouse anti-ICP4 (55), diluted 1:200; and mouse anti-ICP27 (Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc.), diluted 1:500. Secondary antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antirabbit or antimouse (Sigma), diluted 1:100. Microscopy was carried out with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

RESULTS

Long-term expression mediated by pp71.

Previous studies using in1312-based recombinants as templates suggested that pp71 exhibited similarities to ICP0 in short-term assays, in which effects were monitored through the first 24 h postinfection (p.i.). Since HFFF2 cells can be maintained at 38.5°C in medium containing 2% serum for at least 2 weeks with no apparent deterioration, we investigated viral gene expression at later times after infection. Preliminary experiments suggested that β-galactosidase could be detected for many days in monolayers coinfected with in1324 and a reporter virus in1382 (in1312 with the lacZ coding sequences, controlled by the HCMV IE promoter, inserted at the TK locus). This effect was not observed with in1382 alone, suggesting that pp71 expressed by in1324 exerted an effect at late times p.i. To circumvent the problems inherent in dually infecting cells, in1360 was constructed. This mutant was derived by inserting HCMV IE-lacZ into the nonessential UL43 locus of in1324.

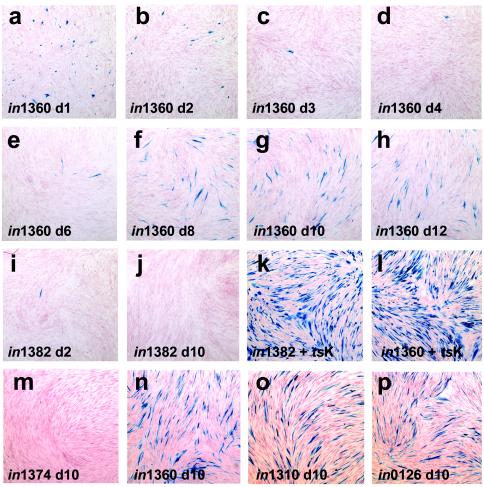

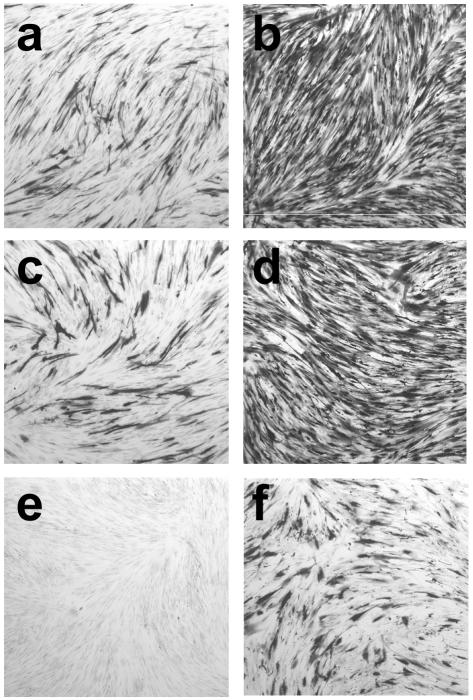

Infection of monolayers consisting of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells with 1.5 × 106 PFU of in1382 resulted in the pattern of β-galactosidase expression expected from previous studies (48, 53). A few β-galactosidase-positive cells were detected at days 1 and 2 p.i. (Fig. 1i), but the numbers declined through days 3 and 4, with no positive cells detectable by day 8 (panel j). Superinfection with the HSV-1 mutant tsK at day 9 resulted in the production of β-galactosidase in most cells due to reversal of the quiescent state by ICP0 (panel k), demonstrating that quiescent viral genomes were efficiently retained in cultures. Monolayers infected with 1.5 × 106 PFU of in1360 showed greater numbers of β-galactosidase-expressing cells at days 1 and 2 (panels a and b) than in1382-infected cultures, due to the short-term effect of pp71 described previously (20, 37). As found in in1382-infected cultures, the number of positive cells declined through days 3 and 4 (panels c and d), but by day 6 more cells expressing β-galactosidase were detected (panel e). The number of positive cells increased by day 8 (panel f) and remained stable through days 10 and 12 (panels g and h). Morphologically, the cells detected at late times appeared normal, whereas those at days 1 to 4 were rounded. Superinfection of in1360-infected cultures with tsK caused most cells to express β-galactosidase (panel l), confirming the retention of the in1360 genome.

FIG. 1.

Long-term expression of β-galactosidase. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with in1312-derived viruses, maintained at 38.5°C, and stained with X-Gal at various times p.i. Monolayers infected with 1.5 × 106 PFU of in1360 were stained on days 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), 4 (d), 6 (e), 8 (f), 10 (g), and 12 (h) p.i. or day 10 (after infection with 106 PFU of tsK on day 9) (l). Monolayers infected with 1.5 × 106 PFU of in1382 were stained at 2 (i) or 8 (j) days p.i. or day 10 (after infection with 106 PFU of tsK on day 9) (k). Also shown are monolayers at day 10 after infection with 3 × 106 PFU of in1374 (m), in1360 (n), in1310 (o), or in0126 (p).

The results suggest that pp71 enabled the in1360 genome to continue β-galactosidase expression in a proportion of cells (approximately 10% of the number detected by superinfection with tsK) through times at which it is normally converted to a stable quiescent state. The effect was not due to interruption of the UL43 coding region, since in1374, which is in1312 with HCMV IE-lacZ inserted in UL43, also became quiescent (Fig. 1m). In subsequent experiments, cultures were infected with 3 × 106 PFU of recombinant virus, resulting in a higher proportion of β-galactosidase positive cells at late times for in1360 (panel n). An independently derived recombinant, in1310, that expresses a YFP-pp71 fusion protein and additionally has HCMV IE-lacZ in UL43 was as efficient as in1360 in directing long-term expression (panel o). Importantly, replacement of the HCMV IE-pp71 insertion of in1360 with HCMV IE-GFP yielded a virus that, like in1382, became quiescent but did not exhibit long-term expression of β-galactosidase (results not shown). These last two observations confirm that the novel properties of in1360 are due to the expression of pp71 rather than to a fortuitous mutation elsewhere in the genome.

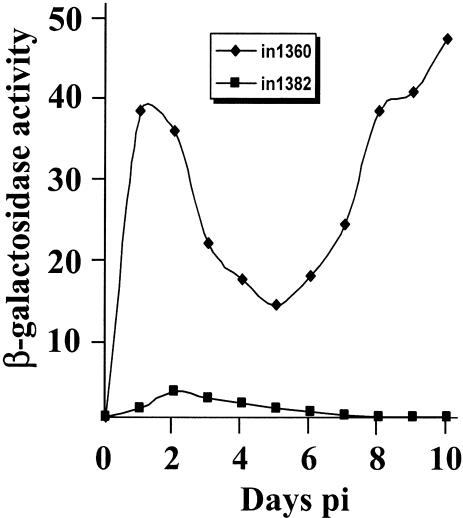

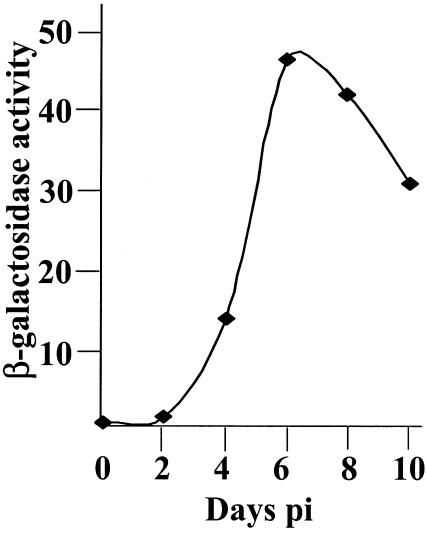

Enzyme assays carried out on cell extracts reproduced the pattern of expression shown by histochemical staining of monolayers (Fig. 2). Cultures infected with in1360 accumulated more β-galactosidase than those infected with in1382 within the first few days of infection and, after a decline between days 4 and 6 p.i., exhibited a late rise in activity.

FIG. 2.

Time course of β-galactosidase expression. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1360 or in1382 and maintained at 38.5°C. Extracts were made and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Duplicates did not vary by more than 10% of the average value.

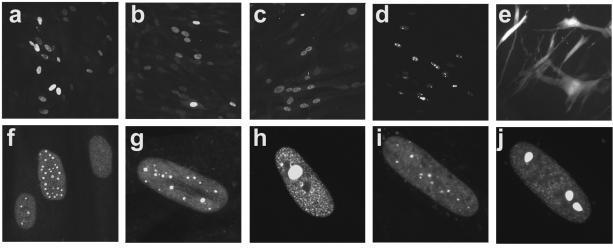

Previous studies have shown that pp71, in short-term assays, activates expression from a variety of promoters resident in the in1312 genome; thus, it was of interest to investigate whether additional proteins were present in in1360-infected cells. Monolayers were infected with in1360 and, on day 10 p.i., subcultured and plated on coverslips for immunofluorescence (Fig. 3). Cells positive for low levels of the HSV-1 IE proteins ICP4 (panel a) and ICP27 (panel b) were detected, and pp71 was also shown to be present (panel c). Cells similarly infected with in1316 contained the YFP-pp71 fusion protein at 10 days p.i. (panel d), and monolayers infected with in1317, which is analogous to in1360 but with a GFP gene instead of lacZ in UL43, expressed GFP (panel e). A variety of intranuclear distributions of pp71 were observed within nuclei, as found in short-term assays (37), and representative images are shown in panel f. No cells were positive for the HSV-1 IE proteins in in1382-infected cultures (results not shown). Long-term expression from early and late promoters was not detected in the presence of pp71, indicating that the requirement for functional ICP4 was retained in in1312-based recombinants (C. M. Preston, unpublished results).

FIG. 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of HFFF2 cells. Monolayers of HFFF2 cells were infected with various viruses and maintained at 38.5°C for 10 days. Cells were subcultured and plated on coverslips. After 24 h, cells were fixed and analyzed, either after staining with antibodies or directly. In panels a to c, 8 × 105 cells were initially infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1360 per monolayer and reacted with anti-ICP4 (a), anti-ICP27 (b), or anti-pp71 (c). Panel d shows cells infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1316 per culture, revealing the presence of YFP-pp71, and panel e shows cells infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1317 per culture, demonstrating long-term expression of GFP. Panel f shows a composite of nuclei from cells infected with in1360 and stained with anti-pp71, at higher magnification than that for panel c. For panels g to j, 2 × 105 cells on coverslips were infected with 2 × 104 PFU of in1316 (g, h) or in0123 (i, j), and images of cells with relatively small (g, i) or large (h, j) amounts of YFP-pp71 were captured.

These findings show that pp71 directs long-term expression from the in1312 genome in a manner that is not promoter sequence specific. However, the experiments also raise the possibility that the action of pp71 is indirect. The HSV-1 IE proteins ICP22 and ICP27, encoded by US1 and UL54, respectively, have each been implicated in transcriptional regulation (1, 34, 58, 63, 64); thus, it could be these proteins that mediated the long-term expression, either alone or in combination with pp71. To resolve whether this was the case, derivatives of in1312 with an additional deletion of US1 or UL54 were constructed. The major part of the ICP22 coding region was replaced with HCMV IE-lacZ, and subsequently, HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 was inserted at the TK locus to yield the mutant in0126. This recombinant virus expressed β-galactosidase at day 10 p.i. as efficiently as did in1310 or in1360 (Fig. 1p), demonstrating that the absence of ICP22 did not affect long-term expression. In addition, the result shows that long-term expression of β-galactosidase is not restricted to viruses with the transgene inserted at UL43. Deletion of UL54 was achieved by inserting HCMV IE-YFP-pp71 into this locus of in1312, a process that simultaneously removed the ICP27 coding region. The resultant virus, in0123, was isolated and propagated on the complementing U2OS cell line SCP3, but unfortunately, high-titer stocks could not be obtained. The absence of functional VP16 in in0123 to stimulate expression of the ICP27 sequences resident in the SCP3 cell genome may have been the limiting factor. It was not possible, therefore, to infect cultures with sufficient virus to show long-term expression in a significant proportion of cells. Nonetheless, at the highest multiplicities that could be achieved, the YFP-pp71 fusion protein was detected in individual cells at day 10 p.i. in cultures infected with in0123 (Fig. 3g and h), at a frequency equivalent to that in cultures infected with the same multiplicity of in1316 (panels i and j), showing that long-term expression was achieved without ICP27. It was concluded that neither ICP22 nor ICP27 is required for long-term expression and therefore that the effect is mediated solely by pp71.

Regulated expression.

One of the hallmarks of quiescent infection is the unresponsiveness of the viral genome to trans-acting factors. Since a proportion of the cells infected with in1360 continued to express β-galactosidase many days p.i., we investigated whether responsiveness was also retained. Previous experiments have shown that quiescent genomes rapidly become insensitive to activation by VP16 (48). A hybrid promoter was constructed by ligating the enhancer region of the HCMV IE promoter to the proximal, TAATGARAT-containing portion of the HSV-1 ICP0 promoter. Recombinant in1312-based viruses containing an insertion at the UL43 locus of the hybrid promoter controlling lacZ, with (in1307) or without (in1306) HCMV IE-pp71 inserted at TK, were constructed and analyzed. Cultures were infected with the mutants and, on day 10 p.i., subcultured and either mock infected, infected with UV-irradiated tsK to introduce VP16, or infected with tsK to provoke β-galactosidase expression in all cells harboring a viral genome (Fig. 4). Without pp71, the hybrid promoter was repressed (panel a), but when pp71 was present, cells expressing β-galactosidase were present (panel d) at levels similar to those observed in in1360-infected cultures (panel g). In the absence of VP16, therefore, the hybrid promoter behaved similarly to the HCMV IE promoter. Infection with UV-irradiated tsK did not affect β-galactosidase expression in in1306-infected cells (panel b) and did not stimulate expression from the HCMV IE promoter in in1360 (panel h). In in1307-infected cultures, however, infection with UV-irradiated tsK resulted in a clear increase in the number of β-galactosidase-positive cells and in the intensity of staining (panel e). Infection with unirradiated tsK demonstrated that comparable amounts of virus were present in all cultures (panels c, f, and i). Enzymatic assay of β-galactosidase confirmed the findings from histochemical staining (Table 2). Infection of cultures harboring in1307 with UV-irradiated tsK increased β-galactosidase levels by eightfold and was approximately 35% as effective as infection with unirradiated tsK. Therefore, the presence of pp71 conferred VP16 responsiveness to many quiescent genomes that did not detectably express β-galactosidase.

FIG. 4.

Response to VP16. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1306 (a to c), in1307 (d to f), or in1360 (g to i) and maintained at 38.5°C. At day 10 p.i., monolayers were subcultured, and the next day they were mock infected (a, d, and g) or infected with 106 PFU (titer prior to irradiation) of UV-irradiated tsK (b, e, and h) or 106 PFU of unirradiated tsK (c, f, and i). Monolayers were stained after a further 24 h at 38.5°C.

TABLE 2.

Activation of the HCMV/ICP0 hybrid promoter by VP16

| Initial agent of infection | β-Galactosidase activity after infection witha:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mock | uv-tsK | tsK | |

| in1306 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 600 |

| in1307 | 16.1 | 129 | 366 |

| in1360 | 21.2 | 17.4 | 255 |

β-Galactosidase activities were determined in extracts of cells treated as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The mean values from triplicate samples are presented.

Additional evidence for the existence of genomes that respond to trans-acting factors was obtained. In the first case, in1360-infected cultures at day 10 p.i. were subcultured, and maintained for 3 days at 32°C or 38.5°C, in the presence of neutralizing human serum (Fig. 5a and b). Temperature downshift renders the ts ICP4 active and the virus potentially capable of replication, albeit at low efficiency due to the absence of functional VP16 or ICP0. Many plaques developed on monolayers maintained at 32°C (panel b), demonstrating that the in1360 genome remained sensitive to ICP4 and could resume replication. No plaques were observed on similarly treated cultures infected with in1382, as expected from previous studies on the nature of the quiescent state (results not shown). In further experiments, in1360-infected cells were treated with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) at day 10 p.i. (panels c and d). Addition of the compound for 2 days increased both the number of β-galactosidase-positive cells and the average intensity of staining. This observation was confirmed by conducting enzyme assays on cell extracts: TSA treatment increased β-galactosidase levels by sixfold. Again, no increase in β-galactosidase expression was observed in in1382-infected cultures (results not shown). Similar results were obtained by addition of an alternative deacetylase inhibitor, suberoyl bishydroxamic acid (results not shown).

FIG. 5.

Response to downshift and TSA. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with 5 × 105 PFU of in1360 (a, b) and maintained at 38.5°C for 10 days. One set of monolayers was subcultured and maintained for a further 3 days at 38.5°C (a) or 32°C (b), with 2% (vol/vol) human serum added to culture medium. Monolayers infected with 1.5 × 106 PFU of in1360 (c, d) were maintained at 38.5°C for 8 days, and incubation was continued for a further 3 days with no additions (c) or in the presence of 660 nM TSA (d).

The findings reported in this section demonstrate that in addition to conferring long-term activity to a proportion of in1360 genomes, pp71 enables genomes to retain responsiveness to trans-acting factors that act in either a sequence-specific manner or a nonspecific manner.

The C terminus, but not the LACSD motif, is important for long-term expression.

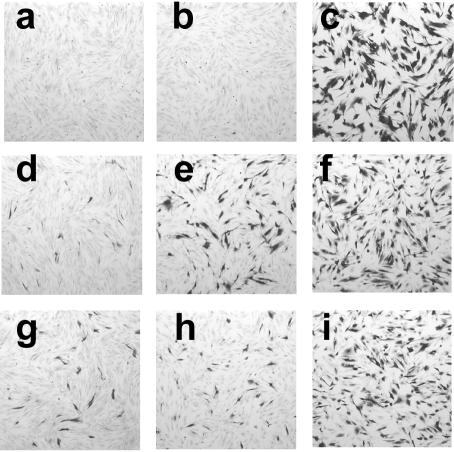

It has been shown that pp71 directs the degradation of unphosphorylated Rb gene products and that the motif LACSD at residues 216 to 220 is indispensable for this property (28, 30). Mutation of the central cysteine to glycine abolished the effect. To investigate whether Rb degradation is linked to the long-term regulation of gene expression by pp71, mutant viruses were constructed harboring transgenes with the critical motif changed to LAGSD. This change, however, did not alter the ability of pp71 to mediate long-term activity of the HCMV IE promoter (Fig. 6a and c) or the attainment of the quiescent state (panels b and d). A recombinant virus that expresses a YFP-pp71 protein lacking the C-terminal 61 amino acids, in0125, was constructed and tested. This mutant was unable to direct long-term expression when inserted into in1312-based viruses (Fig. 6e), even though the virus established a quiescent infection as shown by the resumption of gene expression upon infection of cultures with tsK (panel f). The reduced number of positive cells after infection with tsK was found reproducibly and may indicate that the deleted YFP-pp71 protein exhibits a degree of cytotoxicity.

FIG. 6.

Effects of pp71 mutations on long-term expression. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in0121 (a, b), in1360 (c, d), or in0125 (e, f) and maintained at 38.5°C. Monolayers were stained at day 10 p.i. (a, c, and e) or infected with 106 PFU of tsK and stained after 24 h at 38.5°C (b, d, and f).

The protein pp71 acts in trans to reactivate quiescent genomes.

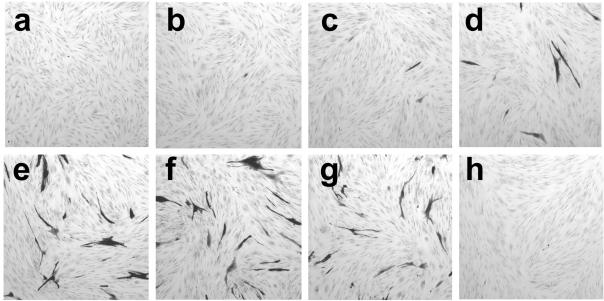

One interpretation of the results presented above is that a proportion of cells in cultures infected with in1360 were not fully repressed but remained responsive to transactivators. An alternative possibility is that genomes became quiescent, but pp71 was able to reverse the quiescent state. The latter idea was discounted in our previous publications because infection with HCMV particles in the presence of cycloheximide or infection with in1324 could not reverse the quiescent state over experimental periods of 6 to 24 h, a time that is sufficient for ICP0 to act fully (37, 48). The delay in the appearance of expressing cells, shown in Fig. 1, prompted us to reinvestigate the previous findings. Monolayers were infected with in1382, maintained at 38.5°C for 10 days, and subcultured and infected with in1324, which expresses pp71, or, as a control, in1372, an analogous in1312 derivative that expresses Cre recombinase instead of pp71 (50) (Fig. 7 and 8). Within the first 2 days after infection, β-galactosidase was not detectable by assay of cell lysates (Fig. 8), and in1324-infected monolayers showed few positive cells (Fig. 7a and b). On day 3, however, β-galactosidase was detectable in in1324-infected monolayers (Fig. 8), and greater numbers of positive cells were observable by histochemical staining (Fig. 7c). Enzyme levels and numbers of positive cells increased over the ensuing 3 days by both methods of detection, followed by a slow decline through days 8 and 10 (Fig. 7d through g and Fig. 8). No production of enzyme was detected in cultures up to 10 days after superinfection with in1372 (Fig. 7h), even though further infection with tsK revealed that at least 50% of cells still harbored the in1382 genome (results not shown). Therefore, pp71 can act in trans on quiescent genomes to provoke the resumption of gene expression after a delay of approximately 3 days.

FIG. 7.

Reactivation of quiescent in1382. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells were infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1382 and maintained at 38.5°C for 10 days. Monolayers were trypsinized and replated at 50% of the original density and infected with 3 × 106 PFU of in1324 (a to g) or in1372 (h). Cells were stained at days 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), 4 (d), 6 (e, h), 8 (f), or 10 (g) after infection with in1324 or in1372.

FIG. 8.

Production of β-galactosidase upon superinfection. Monolayers of 8 × 105 HFFF2 cells, treated as described in the legend to Fig. 7, were harvested at various times after superinfection with in1324, and β-galactosidase assays were carried out. Duplicates did not vary by more than 10% of the average value.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented here describe an unexpected and novel property of pp71. In the presence of the protein, a significant proportion of human fibroblasts that harbor quiescent in1312 continue to express transgenes, and HSV-1 IE genes, for many days in culture. It must be emphasized that this is a departure from the normal behavior of in1312-based viruses in the absence of pp71. Cell types exhibit a range of permissiveness for ICP0-deficient HSV-1 mutants, and human fibroblasts are the least permissive or, in other words, the cell type in which quiescent infection is favored over replication to the greatest extent (10, 12, 57, 62). In our previous experience, the quiescent state in human fibroblasts was extremely stable, with the viral genome resistant to the action of many stimuli that alter cell metabolism significantly. For instance, as shown in Fig. 4 and 7, the genome remained quiescent during subculturing of cells and replating at reduced density and also after induction of stress responses and treatment with inhibitors or activators of numerous signal transduction pathways (Preston, unpublished). The only previously known way of inducing in1312 from the quiescent state was by provision of ICP0. The data thus support our contention that pp71 exhibits a degree of functional similarity to ICP0 when the HSV-1 genome is used as a target template.

The population of in1360-infected cells that continued to express transgenes many days after infection represented approximately 10% of the total, and a further approximately 20% responded to trans-acting factors, showing that at least 30% of the infected cells did not become fully quiescent. Three different classes of transactivators were able to stimulate expression from the genomes of in1312 derivatives that express pp71. VP16 acts through TAATGARAT elements, and the responsiveness to this agent suggests that other sequence-specific activators also would be effective in switching on expression of transgenes in the in1360 genome. An approach of this type could be used to regulate specifically the expression of foreign genes cloned into in1312, with possible applications in the development of HSV-1 gene therapy vectors. The in1360 genome was also responsive to ICP4, a viral transactivator that acts on viral early and late promoters. The fact that full virus replication ensued upon temperature downshift shows that the there is also no barrier to the access of viral replication proteins. It is not clear whether preexisting ICP4 became active upon downshift of cultures to 32°C or if synthesis of new protein was required at the permissive temperature. TSA is a non-sequence-specific agent that acts by inhibiting deacetylases, resulting in histone acetylation and the acquisition of an active chromatin structure. Although we consider this mechanism to be the most likely pathway by which TSA stimulates β-galactosidase expression from the in1360 genome, we wish to urge caution in accepting this interpretation, since we have observed cell and promoter specificity in the action of TSA (C. M. Preston and J. S. Miller, unpublished observations).

The finding that HFFF2 cells expressed ICP4 and ICP27 without observable detrimental effects was somewhat surprising in view of reports that IE proteins are toxic to cells (26, 47, 54). The previous studies, however, investigated situations in which high levels of IE proteins were produced by transfection of plasmids or infection with viruses that express functional VP16. The amounts of IE proteins that we detected in individual cells were lower than those present during lytic infection or in the presence of VP16 and were probably below the level needed to cause severe cytopathic effects. Nonetheless, we have not conducted a detailed investigation of cell physiology, and more-subtle effects would not have been detected. In a comparative study, it was found that inactivation of VP16 greatly enhanced the survival of human fibroblasts due to a reduction in the amounts of IE proteins accumulated (27), and in addition, Everett et al. showed persistence of IE proteins in viable cells during nonproductive infection of HFFF2 cultures (12).

The unusual biphasic pattern of β-galactosidase expression upon infection with in1360 probably signifies that separate populations existed within the cell culture and that the populations responded in different ways to infection. The cells that were detectable at 1 to 2 days p.i. were rounded, and during the ensuing 2 or 3 days they became shriveled. It is likely that these cells, representing the population that is detected in short-term assays of pp71 activity, were killed and lost from the culture. Cells of the second population were not detected until day 5 p.i. and were of normal morphology. The kinetics of β-galactosidase accumulation, at least during days 5 to 7 p.i., were slower than those observed during the first day p.i., suggesting that the HCMV IE promoter was not fully active. The time course of appearance of these cells was similar to that observed after “reactivation ” by pp71 (Fig. 7 and 8), suggesting that in1360 became quiescent in those infected cells not responding to short-term activation but was subsequently slowly turned on by pp71. This hypothesis, however, requires that expression of pp71 itself was not irreversibly shut off. The most likely explanation, therefore, is that the quiescent state is not as complete as previously suspected and that low-level expression of pp71 eventually leads to unblocking of the remainder of the genome. This model has an element of positive feedback: the presence of low levels of pp71 would be expected to increase expression of the protein itself in addition to reporter and HSV IE proteins. The situation may be complicated further by the recent finding that repression of individual genes in an ICP0 null mutant is stochastic (12); thus, in some cells the promoter driving pp71 expression may remain active for longer than that controlling lacZ, and vice versa.

In some respects, pp71 can be considered to be performing a role similar to that of HSV-1 ICP0, since it acts in a general way, albeit apparently less effectively, to maintain gene expression for viral genomes. In detail, however, the proteins are likely to act in different ways. pp71 is much slower than ICP0 to induce reactivation of expression from quiescent genomes and also apparently less effective, since very small amounts of ICP0 reverse the quiescent state (18). It is well established that the RING domain of ICP0 is a crucial component of the protein and that binding to the cellular ubiquitin-specific protease USP7 is required for its activity (4, 13, 14). ICP0 also interacts with and stimulates the degradation of many other cell proteins (11, 15). There is no evidence that pp71 requires any of these features for its activity. In addition, ICP0 stimulates the degradation of many ND10 components, whereas pp71 localizes to these structures but apparently leaves them intact. Disruption of ND10 is achieved by the action of the HCMV protein IE72 (2, 31, 60). Conversely, the cell protein Daxx is important for pp71 but has not been implicated in the activity of ICP0. It is likely, therefore, that ICP0 and pp71 achieve similar results through different mechanisms.

The ability of HCMV infection to reactivate HSV-1 has been described previously. In alternative cell models, in which quiescent infection was achieved by infection with an HSV-1 ICP0 mutant or with wild-type HSV-1 or HSV-2 at supraoptimal temperatures, infection of cells with HCMV was able to provoke resumption of HSV replication (52, 56, 59). The HCMV factor responsible for the effect has not been determined, and in view of the observation that HCMV complements the replication of an HSV-1 ICP0 null mutant (56), the HCMV IE proteins have generally been considered to be responsible. The results presented here raise the possibility that pp71 may play a role in the effect.

The degradation of unphosphorylated Rb products, mediated by pp71, does not appear to relate to the long-term effects that are described here. This conclusion relies on the assumption that recognition and degradation of unphosphorylated Rb in HFFF2 cells depends on the LACSD motif, as found in other cell types (28, 30). Although we have not conducted a detailed quantitative analysis, observation of HFFF2 cell monolayers infected with in1382 or in1360 did not reveal any obvious effect of pp71 on the extent or rate of cell division. The requirement for the C-terminal 61 amino acids for both long-term and short-term activity (Fig. 6; also results not shown) suggests that interaction with the cell protein Daxx may be important for pp71 function. Deletion of the C-terminal 61 amino acids only decreased the activity of pp71 by 30% in cotransfection assays (33), but in the yeast two-hybrid assay the equivalent change abolished binding to Daxx (19). The YFP-pp71Δ61 fusion protein migrated to the cell nucleus but did not localize to ND10 (C. M. Preston, unpublished observations), in agreement with the suggestion that Daxx is important for translocation of pp71 to the site of HCMV IE transcription (23).

In considering the possible significance of pp71 for the replication of HCMV, the short-term activation of gene expression is clearly important for rapid initiation of the viral transcription program (5). A regulatory event prior to IE protein synthesis has the additional possible benefit of permitting control of the viral replication cycle: infection of cells in a situation in which pp71 cannot function may result in survival of the host cell and retention of the HCMV genome. Similar arguments have been made to rationalize the importance of VP16 for HSV-1 replication and latency (45, 61). Viewed in another way, pp71, like ICP0, is important for antagonizing cell mechanisms that repress the incoming viral genome. One obvious cell defense is the interferon (IFN) response, and this is particularly relevant, since HSV-1 ICP0 null mutants are hypersensitive to alpha IFN (40) and disruption of ND10 by elimination of PML aborts the antiviral response to alpha IFN (8). We have observed, however, that in1360 exhibits long-term expression in human fetal lung fibroblasts (Preston, unpublished), and previous studies showed that human fetal lung cells, in contrast to HFFF2 cells, do not release endogenous IFN in response to infection with HSV-1 (46). It is noteworthy that the HCMV infection cycle stretches over several days and that cell protein synthesis continues during this time; thus, antagonism of cellular silencing may be necessary throughout the viral replication period. A longer-term requirement of this type could be met initially by incoming pp71 and by newly synthesized pp71 at later times in infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Rinaldi for assistance with early experiments, George Sourvinos for help with live cell microscopy, and Roger Everett and Duncan McGeoch for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Advani, S. J., R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2003. Herpes simplex virus 1 activates cdc2 to recruit topoisomerase II alpha for post-DNA synthesis expression of late genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4825-4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 2000. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies by IE1 correlates with efficient early stages of viral gene expression and DNA replication in human cytomegalovirus infection. Virology 274:39-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldick, C. J., A. Marchini, C. E. Patterson, and T. Shenk. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 71:4400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutell, C., S. Sadis, and R. D. Everett. 2002. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP0 and its isolated RING finger domain act as ubiquitin E3 ligases in vitro. J. Virol. 76:841-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresnahan, W. A., and T. E. Shenk. 2000. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14506-14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, M. E., J. W. Palfreyman, and C. M. Preston. 1984. Identification of herpes simplex virus DNA sequences which encode a trans-acting polypeptide responsible for stimulation of immediate early transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 180:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chau, N. H., C. D. Vanson, and J. A. Kerry. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the human cytomegalovirus US11 early gene. J. Virol. 73:863-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chee, A. V., P. Lopez, P. P. Pandolfi, and B. Roizman. 2003. Promyelocytic leukemia protein mediates interferon-based anti-herpes simplex virus 1 effects. J. Virol. 77:7103-7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Hersnell, C. A. Hutchinson, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, E. Preddie, S. C. Satchwell, P. Tomlinson, K. M. Weston, and B. G. Barrell. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everett, R. D. 1989. Construction and characterisation of herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants with defined lesions in immediate early gene 1. J. Gen. Virol. 70:1185-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett, R. D. 2000. ICP0, a regulator of herpes simplex virus during lytic and latent infection. Bioessays 22:761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett, R. D., C. Boutell, and A. Orr. 2004. Phenotype of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant that fails to express immediate-early regulatory protein ICP0. J. Virol. 78:1763-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett, R. D., M. R. Meredith, A. Orr, A. Cross, M. Kathoria, and J. Parkinson. 1997. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease is dynamically associated with the PML nuclear domain and binds to a herpesvirus regulatory protein. EMBO J. 16:1519-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett, R. D., P. O'Hare, D. O'Rourke, P. Barlow, and A. Orr. 1995. Point mutations in the herpes simplex virus type 1 Vmw110 RING finger helix affect activation of gene expression, viral growth, and interaction with PML-containing nuclear structures. J. Virol. 69:7339-7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagglund, R., and B. Roizman. 2004. Role of ICP0 in the strategy of conquest of the host cell by herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 78:2169-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris, R. A., and C. M. Preston. 1991. Establishment of latency in vitro by the herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant in 1814. J. Gen. Virol. 72:907-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensel, G. M., H. H. Meyer, I. Buchmann, D. Pommerehne, S. Schmolke, B. Plachter, K. Radsak, and H. F. Kern. 1996. Intracellular localization and expression of the human cytomegalovirus matrix phosphoprotein pp71 (ppUL82): evidence for its translocation into the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 77:3087-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobbs, W. E., D. E. Brough, I. Kovesdi, and N. A. DeLuca. 2001. Efficient activation of viral genomes by levels of herpes simplex virus ICP0 insufficient to affect cellular gene expression or cell survival. J. Virol. 75:3391-3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann, H., H. Sindre, and T. Stamminger. 2002. Functional interaction between the pp71 protein of human cytomegalovirus and the PML-interacting protein human Daxx. J. Virol. 76:5769-5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Homer, E. G., A. Rinaldi, M. J. Nicholl, and C. M. Preston. 1999. Activation of herpesvirus gene expression by the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Virol. 73:8512-8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishov, A. M., A. G. Sotnikov, D. Negorev, O. V. Vladimirova, N. Neff, T. Kamitani, E. T. Yeh, J. F. Strauss III, and G. G. Maul. 1999. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein Daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 147:221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishov, A. M., R. M. Stenberg, and G. G. Maul. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early interaction with host nuclear structures: definition of an immediate transcript environment. J. Cell Biol. 138:5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishov, A. M., O. V. Vladimirova, and G. G. Maul. 2002. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J. Virol. 76:7705-7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson, S. A., and N. A. DeLuca. 2003. Relationship of herpes simplex virus genome configuration to productive and persistent infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7871-7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamieson, D. R. S., L. H. Robinson, J. I. Daksis, M. J. Nicholl, and C. M. Preston. 1995. Quiescent viral genomes in human fibroblasts after infection with herpes simplex virus Vmw65 mutants. J. Gen. Virol. 76:1417-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, P. A., A. Miyanohara, F. Levine, T. Cahill, and T. Friedmann. 1992. Cytotoxicity of a replication-defective mutant of herpes simplex type 1. J. Virol. 66:2952-2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, P. A., M. J. Wang, and T. Friedmann. 1994. Improved cell survival by the reduction of immediate-early gene expression in replication-defective mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 but not by mutation of the virion host shutoff function. J. Virol. 68:6347-6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalejta, R. F., J. T. Bechtel, and T. Shenk. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression by inducing the proteasome-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1885-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalejta, R. F., and T. Shenk. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL82 gene product (pp71) accelerates progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 77:3451-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalejta, R. F., and T. Shenk. 2003. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of the Rb family of tumor suppressors by the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:3263-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korioth, F., G. G. Maul, B. Plachter, T. Stamminger, and J. Frey. 1996. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp. Cell Res. 229:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronschnabl, M., and T. Stamminger. 2003. Synergistic induction of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by the human cytomegalovirus transactivators IE2p86 and pp71 is mediated via an Sp1-binding site. J. Gen. Virol. 84:61-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, B., and M. F. Stinski. 1992. Human cytomegalovirus contains a tegument protein that enhances transcription from promoters with upstream ATF and AP-1 cis-acting elements. J. Virol. 66:4434-4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long, M. C., V. Leong, P. A. Schaffer, C. A. Spencer, and S. A. Rice. 1999. ICP22 and the UL13 protein kinase are both required for herpes simplex virus-induced modification of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II. J. Virol. 73:5593-5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLean, C. A., S. Efstathiou, M. Elliott, F. E. Jamieson, and D. J. McGeoch. 1991. Investigation of herpes simplex virus type 1 genes encoding multiply inserted membrane proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 72:897-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall, K. R., R. H. Lachmann, S. Efstathiou, A. Rinaldi, and C. M. Preston. 2000. Long-term transgene expression in mice infected with a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant severely impaired for immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 74:956-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall, K. R., K. V. Rowley, A. Rinaldi, I. P. Nicholson, A. M. Ishov, G. G. Maul, and C. M. Preston. 2002. Activity and intracellular localization of the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1601-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFarlane, M., J. I. Daksis, and C. M. Preston. 1992. Hexamethylene bisacetamide stimulates herpes simplex virus immediate early gene expression in the absence of trans-induction by Vmw65. J. Gen. Virol. 73:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGeoch, D. J., M. A. Dalrymple, A. J. Davison, A. Dolan, M. C. Frame, D. McNab, L. J. Perry, and P. Taylor. 1988. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 69:1531-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mossman, K. L., H. A. Saffran, and J. R. Smiley. 2000. Herpes simplex virus ICP0 mutants are hypersensitive to interferon. J. Virol. 74:2052-2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mossman, K. L., and J. R. Smiley. 1999. Truncation of the C-terminal acidic activation domain of herpes simplex virus VP16 renders expression of the immediate-early genes almost entirely dependent on ICP0. J. Virol. 73:9726-9733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowak, B., A. Gmeiner, P. Sarnow, A. J. Levine, and B. Fleckenstein. 1984. Physical mapping of human cytomegalovirus genes: identification of DNA sequences coding for a virion phosphoprotein of 71 kDa and a viral 65-kDa polypeptide. Virology 134:91-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Hare, P. 1993. The virion transactivator of herpes simplex virus. Semin. Virol. 4:145-155. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preston, C. M. 1979. Control of herpes simplex virus type 1 mRNA synthesis in cells infected with wild-type virus or the temperature-sensitive mutant tsK. J. Virol. 29:275-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston, C. M. 2000. Repression of viral transcription during herpes simplex virus latency. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Preston, C. M., A. N. Harman, and M. J. Nicholl. 2001. Activation of interferon response factor-3 in human cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 or human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 75:8909-8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preston, C. M., R. Mabbs, and M. J. Nicholl. 1997. Construction and characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants with conditional defects in immediate early gene expression. Virology 229:228-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preston, C. M., and M. J. Nicholl. 1997. Repression of gene expression upon infection of cells with herpes simplex virus type 1 mutants impaired for immediate-early protein synthesis. J. Virol. 71:7807-7813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preston, C. M., A. Rinaldi, and M. J. Nicholl. 1998. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early gene expression is stimulated by inhibition of protein synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 79:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rinaldi, A., K. R. Marshall, and C. M. Preston. 1999. A non-cytotoxic herpes simplex virus vector which expresses Cre recombinase directs efficient site specific recombination. Virus Res. 65:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruger, B., S. Klages, B. Walla, J. Albrecht, B. Fleckenstein, P. Tomlinson, and B. Barrell. 1987. Primary structure and transcription of the genes coding for the two virion phosphoproteins pp65 and pp71 of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 61:446-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russell, J., and C. M. Preston. 1986. An in vitro latency system for herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Gen. Virol. 67:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samaniego, L. A., L. Neiderhiser, and N. A. DeLuca. 1998. Persistence and expression of the herpes simplex virus genome in the absence of immediate-early proteins. J. Virol. 72:3307-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samaniego, L. A., N. Wu, and N. A. DeLuca. 1997. The herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP0 affects transcription from the viral genome and infected-cell survival in the absence of ICP4 and ICP27. J. Virol. 71:4614-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Showalter, L. D., M. Zweig, and B. Hampar. 1981. Monoclonal antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 1 proteins including the immediate-early protein ICP4. Infect. Immun. 34:684-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stow, E. C., and N. D. Stow. 1989. Complementation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 Vmw110 deletion mutant by human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 70:695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stow, N. D., and E. C. Stow. 1986. Isolation and characterisation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant containing a deletion within the gene encoding the immediate early polypeptide Vmw110. J. Gen. Virol. 67:2571-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang, Q. Y., L. G. Li, A. M. Ishov, V. Revol, A. L. Epstein, and G. G. Maul. 2003. Determination of minimum herpes simplex virus type 1 components necessary to localize transcriptionally active DNA to ND10. J. Virol. 77:5821-5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wigdahl, B. L., A. C. Scheck, E. DeClercq, and F. Rapp. 1982. High efficiency latency and reactivation of herpes simplex virus in human cells. Science 217:1145-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilkinson, G. W., C. Kelly, J. H. Sinclair, and C. Rickards. 1998. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wysocka, J., and W. Herr. 2003. The herpes simplex virus VP16-induced complex: the makings of a regulatory switch. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:294-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao, F., and P. A. Schaffer. 1995. An activity specified by the osteosarcoma line U2OS can substitute functionally for ICP0, a major regulatory protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:6249-6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou, C. H., and D. M. Knipe. 2002. Association of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP8 and ICP27 proteins with cellular RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. J. Virol. 76:5893-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu, Z. M., N. A. DeLuca, and P. A. Schaffer. 1996. Overexpression of the herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early regulatory protein, ICP27, is responsible for the aberrant localization of ICP0 and mutant forms of ICP4 in ICP4 mutant virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 70:5346-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]