Abstract

Introduction

Lumbar puncture is one of the oldest and most commonly performed procedures in medicine, used to diagnose and treat disease. Headache following lumbar puncture remains a frequent complication, causing significant patient discomfort and often requiring narcotic analgesia or invasive therapy. Needle tip design has been proposed to affect the incidence of headache postlumbar puncture, with pencil-point ‘atraumatic’ needles thought to reduce its incidence in comparison to bevelled ‘traumatic’ needles. Despite this, the use of atraumatic needles and knowledge of their existence remains significantly limited among clinicians. This study will systematically review the evidence on atraumatic lumbar puncture needles and compare them with traumatic needles across a variety of clinical outcomes.

Methods and analyses

We will include published randomised controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies and abstracts, with no publication type or language restrictions. Search strategies will be designed to peruse the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, CINAHL, WHO Clinical Trials Database and Cochrane Library databases. We will also implement strategies to search the grey literature. 3 reviewers will thoroughly and independently examine the search results, complete data abstraction and conduct quality assessment. Included RCTs will be assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool and eligible observational studies will be examined using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. We will examine the outcomes of: headache and its type, intensity, duration and treatment; backache; success rate; hearing disturbance and nerve root irritation. The primary outcome will be the incidence of postdural puncture headache. We will calculate pooled estimates, relative risks for dichotomous outcomes and weighted mean differences for continuous outcomes, with corresponding 95% CIs. Statistical heterogeneity will be measured using Cochran's Q test and quantified using the I2 statistic. We will also conduct prespecified subgroup and sensitivity analyses to examine if covariates exist and to explore potential heterogeneity.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics board approval is not required for this study as it draws from published data and raises no concerns related to patient privacy. This review will provide a comprehensive assessment of the evidence on atraumatic needles for lumbar puncture and is directed to a wide audience. Results from the review will be disseminated extensively through conferences and submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

Trial registration number

CRD42016047546.

Keywords: Lumbar Puncture, Atraumatic Needle, Traumatic Needle, Post-dural Puncture Headache

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review will comprehensively examine the evidence on clinical outcomes of atraumatic lumbar puncture needles and compare them with the traumatic needle type.

An extensive literature search, developed in consultation with a librarian with experience in systematic reviews, will be conducted to include studies from multiple different databases, without language or publication type restrictions.

Heterogeneity is expected to exist in the primary outcome; however, we plan to explore it by conducting several prespecified subgroup analyses.

The current systematic review protocol does not plan to evaluate economic analysis. We intend to examine cost in future studies but not in the current meta-analysis methodology.

Introduction

Lumbar puncture is one of the most common invasive procedures in modern medicine. It is used routinely by physicians not only to diagnose disease through sampling or imaging, but also to treat by delivering chemotherapy or anaesthesia, or reducing intracranial pressure.1 2 It remains one of the most widely practiced procedures, being performed by various specialists, such as neurologists, neurosurgeons, paediatricians, anaesthesiologists, emergency physicians, radiologists and internists. While the safety profile of lumbar puncture has improved drastically since its inception in the 1800s, it remains plagued by often debilitating patient complications, the most prominent of which is headache. Postlumbar puncture headaches are classically described as postural in nature and frontal–occipital in location. These headaches can severely impact patient well-being, often requiring hospitalisation and potentially, invasive therapy.3

Headache is postulated to occur as a result of leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the site of the dural tear created during the puncture. This leakage results in a decrease in CSF pressure, causing traction of pain-sensitive structures in the cranium. Multiple factors, such as needle gauge, needle tip design, patient position and operator experience, have been proposed to affect the incidence of headache following lumbar puncture. Of prime importance is the needle tip design. Spinal needles can be broadly characterised as being atraumatic or traumatic depending on their tip configuration.4 Traumatic or ‘conventional’ needles are the most commonly used. They feature a bevelled tip, designed to puncture through tissue, with an opening at the tip to facilitate collection of CSF or injection of therapeutics. In contrast, atraumatic needles are blunted, with a pencil-point tip and a side port for injection or collection. Theoretically, atraumatic needles dilate the dural fibres, splaying them during the procedure, and following removal of the needle, allow them to gradually return to their original position, in contrast to traumatic needles, which tear and damage the dural tissue.3 5

Despite development of atraumatic needles early in the 20th century, their use in clinical practice and knowledge of their existence among clinicians remains significantly limited. In fact, as few as 2% of clinicians surveyed reported using atraumatic needles.6 This review will aim to systematically examine atraumatic needles in comparison to the traumatic type. This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol has been developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P)7 guidelines and has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42016047546).

Methods

We shall conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA),8 9 the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) consensus statement10 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.11 This protocol will be amended and updated in conjunction with the PRISMA-P guidelines,7 and updated versions will be made available on PROSPERO, with catalogued version history.

Literature search

A detailed search will be conducted of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, CINAHL, WHO Clinical Trials Database and Cochrane Library databases through 5 January 2017, without language or publication type restrictions. We will use keywords and medical subject heading terms related to needle type (atraumatic or traumatic) and clinical outcomes. Search strategies will be developed in consultation with a librarian with expertise in systematic reviews.12 The search strategy employed for the MEDLINE database is provided in table 1. The search will be supplemented by manually screening the references of relevant articles, reviewing the proceedings of pertinent meetings, and contacting clinical experts in the field.

Table 1.

Search strategy for the MEDLINE electronic database using the Ovid interface

| Database | Search terms |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE 1946–present |

|

Study selection

Three investigators will independently evaluate studies for eligibility. Disagreements between the reviewers concerning the decision to include or exclude a study will be resolved by consensus, and if necessary, consultation with a fourth reviewer. Our inclusion criteria shall be:

Study design: randomised controlled trials (RCTs; including cluster RCTs and pilot studies), controlled (non-randomised) clinical trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and abstracts, with no publication type or language restrictions,

Population: patients of any age group and demographic undergoing lumbar puncture as a part of their clinical care,

Intervention: lumbar puncture with atraumatic needle,

Control: lumbar puncture with traumatic needle,

Outcomes: clinical outcomes such as incidence of postdural puncture headache (PDPH; primary outcome), any headache, backache, hearing disturbance, nerve root irritation, traumatic tap, severity of PDPH, duration of PDPH, number of patients requiring intravenous fluids/controlled analgesics or blood patch, failure rate, success on the first attempt and number of attempts required to obtain CSF.

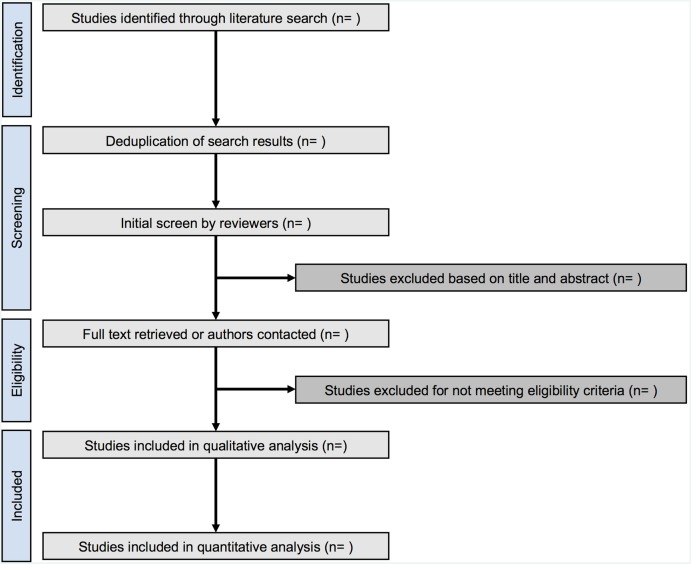

For studies published more than once, we will include only the report with the most informative and complete data. We will exclude studies that did not evaluate atraumatic needles, studies without clinical outcomes such as in vitro studies, review articles, letters, and correspondences or comments (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Data management and collection

Literature search results will be exported from all relevant databases as .ris files or .ciw files containing the complete reference. EndNote X7 software will be used for reference management. Reviewers will develop and pilot screening questions and forms based on the eligibility criteria. Prior to data abstraction, full articles of all eligible studies will be retrieved. For studies not published in English, the full article will be translated into English. In addition, a medical expert fluent in the original language of the article will be involved in data management. Three primary reviewers will independently screen the titles and abstracts obtained by the search against the predefined eligibility criteria. Full reports will be obtained for all references that appear to meet the eligibility criteria, or where there is any ambiguity. Reviewers will then screen the full text and determine whether these articles meet the eligibility criteria. Where necessary, we will contact authors of relevant studies to obtain additional information and resolve questions about eligibility. Discrepancies will be resolved by discussion and consensus, and if necessary, consultation with a fourth reviewer. Reasons for excluding studies will be recorded.

Data from selected studies will be abstracted independently by the three primary reviewers and verified for accuracy by the fourth reviewer. We will gather information from eligible articles using data abstraction forms that include fields for: study first author; year of publication; journal of publication; language; study design; included centres; included countries; number of patients; number of men and women; inpatients or outpatients; recruitment period; eligibility criteria; method of randomisation; purpose of lumbar puncture; specialty of clinician performing lumbar puncture; patient position; atraumatic and traumatic needle-specific type; atraumatic and traumatic needle gauge; procedure for follow-up; scale used to assess headache; treatment of headache; number of patients in atraumatic and traumatic groups; age of patients in atraumatic and traumatic groups; body mass index of patients in atraumatic and traumatic groups; number of patients in atraumatic and traumatic groups given prophylactic intravenous fluids; number of patients in atraumatic and traumatic groups instructed bedrest; characteristics of headache reported; number of patients with postural headache in atraumatic and traumatic groups; number of patients with non-postural headache in atraumatic and traumatic groups; number of patients with postural and non-postural headaches in atraumatic and traumatic groups; severity of headaches in atraumatic and traumatic groups; duration of headaches in atraumatic and traumatic groups; number of patients with backache in atraumatic and traumatic groups; number of patients treated with epidural blood patch for headaches in atraumatic and traumatic groups; success on the first attempt with atraumatic and traumatic needles; number of traumatic taps with atraumatic and traumatic needles; failure rate of atraumatic and traumatic needles; number of attempts required to obtain CSF with atraumatic and traumatic needles; crossovers (atraumatic-to-traumatic and traumatic-to-atraumatic); serious complications (eg, hearing disturbance, nerve root damage, etc); ease of use of needles as reported by authors.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Three reviewers will independently perform quality assessment. The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool11 will be used to assess the risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other biases among included randomised trials. If there is insufficient information provided to make a judgement, we will categorise the study as having an unclear risk of bias and the original study authors will be contacted for further information. Trials with one or more high-risk components will be judged as having an overall high risk of bias. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale13 will be used to assess observational studies on selection, comparability and exposure. Studies that receive at least one star in every domain will be categorised as being of high quality. Disagreements during quality assessment will be resolved through discussion, consensus and, if necessary, consulting a fourth reviewer.

Definition of outcomes

Our clinical outcomes will include multiple incidences after lumbar puncture. Headaches will be categorised into the following groups: PDPH (primary outcome), and any headache. PDPH will be defined as headache fulfilling the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) III criteria,14 which is described as an orthostatic headache occurring within 5 days of a lumbar puncture, caused by CSF leakage through the dural puncture. This headache is usually accompanied by neck stiffness as well as subjective hearing symptoms and remits spontaneously within 2 weeks or after sealing of the leak with an autologous epidural blood patch. ICHD III diagnostic criteria for PDPH are as follows: (1) headache has developed in temporal relation to the low CSF pressure or CSF leakage, or led to its discovery; (2) dural puncture has been performed; (3) headache has developed within 5 days of dural puncture; (4) headache is not better accounted for by another ICHD-III diagnosis.14 The outcome of ‘any headache’ will encompass PDPH and all headaches not fulfilling the previously discussed criteria. Furthermore, we will classify PDPH based on intensity using the visual analogue scale (VAS) as follows: mild (VAS 1–3; responds to over-the-counter analgesics and bedrest), moderate (VAS 4–7; requires controlled or intravenous analgesics, or intravenous caffeine) and severe (VAS 8–10; requires epidural blood patch). We will also evaluate the duration of PDPH, incidence of backache, need for intravenous fluids/controlled analgesics or epidural blood patch, success rate on the first attempt, number of traumatic taps (presence of blood in CSF on visual inspection), failure rate of needles, number of attempts required to obtain CSF, incidence of hearing disturbance and incidence of nerve root irritation.

Data synthesis

We will compare all outcomes for atraumatic versus traumatic needles across randomised trials using the intention-to-treat principle. Dichotomous outcomes, including the incidence of PDPH, any headache, backache, hearing disturbance, nerve root irritation, traumatic tap, severity of PDPH, number of patients requiring blood patch, number of patients requiring intravenous fluids/controlled analgesics, failure rate and success rate on first attempt, with atraumatic and traumatic needles, will be analysed by calculating the relative risk (RR) with corresponding 95% CI. For continuous outcomes, such as the number of attempts with atraumatic and traumatic needles and the duration of PDPH, the weighted mean difference with 95% CI will be calculated. In addition, pooled estimates of all incidences will be calculated across all studies for the atraumatic group, then separately for the traumatic group. Random-effects meta-analyses for all outcomes of interest will be performed using the DerSimonian and Laird model.15 Weights will be calculated using the inverse-variance method. The number needed to prevent harm (NNPH) will be calculated using the following equation:11

|

The threshold of type I error for statistical significance shall be α=0.05. All statistical analyses will be conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.3.3.070 (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA).

Between-study heterogeneity will be evaluated using Cochran's Q test and measured by the I2 statistic, with I2 values exceeding 25%, 50% and 75% being judged as low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively.16 Publication bias will be evaluated visually by funnel plot analyses and quantified by Begg and Mazumdar's17 and Egger's tests.18

Prespecified subgroup analyses will be conducted to examine if covariates exist and to explore potential heterogeneity for the primary outcome (PDPH). We plan to examine subgroups stratified by age, gender, patient position during puncture, needle gauge, quality of studies, prophylactic use of intravenous fluids, postpuncture prophylactic bedrest, purpose of lumbar puncture, continent of publication, older versus newer studies and specialty of physician performing lumbar puncture.

We will conduct sensitivity analyses to examine whether differently manufactured atraumatic or traumatic needles influence the incidence of the primary outcome (PDPH). In addition, we will perform trial sequential analyses and calculate adjusted RR values.19 20 Quality of evidence will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.21 Evidence for all outcomes will be judged for the domains of risk of bias, consistency, precision, reporting bias and directness. Evidence will be ranked as being of high quality (further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the effect size), moderate quality (further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the effect size/may change the effect size), low quality (further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the effect size/likely to change the effect size) or very low quality (any estimate of effect size is very uncertain).21 Results from the analysis will be summarised using the GRADEPro software.

Dissemination

Results from this study are expected to significantly change clinical practice. By comprehensively examining the evidence on atraumatic needles in comparison to traumatic needles for lumbar puncture, this review is expected to inform clinicians on which needle to use for procedures in order to minimise patient complications. The results from this review will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication and will be widely presented at conferences and seminars.

Footnotes

Contributors: SN, JHB, WA and SAA conceived and designed the protocol. SN, LB and SAA developed the search strategy and piloted it in all relevant databases. SN, JHB, WA and SAA developed the review protocol, selection criteria, risk of bias assessment strategy, and data management and synthesis methodology. SN, JHB, WA, FN, EB-C, AK, AS, LB, WO, MS, DS, KR, FF, SSi, SSh, NZ, MS and SAA critically revised and commented on the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Horlocker TT, McGregor DG, Matsushige DK et al. . A retrospective review of 4767 consecutive spinal anesthetics: central nervous system complications. Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 1997;84:578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corke BC, Datta S, Ostheimer GW et al. . Spinal anaesthesia for Caesarean section. The influence of hypotension on neonatal outcome. Anaesthesia 1982;37:658–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1982.tb01278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas SR, Jamieson DR, Muir KW. Randomised controlled trial of atraumatic versus standard needles for diagnostic lumbar puncture. BMJ 2000;321:986–90. 10.1136/bmj.321.7267.986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calthorpe N. The history of spinal needles: getting to the point. Anaesthesia 2004;59:1231–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruickshank RH, Hopkinson JM. Fluid flow through dural puncture sites. An in vitro comparison of needle point types. Anaesthesia 1989;44:415–18. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1989.tb11343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birnbach DJ, Kuroda MM, Sternman D et al. . Use of atraumatic spinal needles among neurologists in the United States. Headache 2001;41:385–90. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.111006385.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 5.1.0 ed The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sollenberger JF, Holloway RG Jr.. The evolving role and value of libraries and librarians in health care. JAMA 2013;310: 1231–2. 10.1001/jama.2013.277050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D et al. . The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [Webpage] 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 14.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33:629–808. 10.1177/0333102413485658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorlund K, Engstrom J, Wetterslev J et al. . User manual for trial sequential analysis (TSA). Copenhagen, Denmark: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J et al. . Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:64–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]