Abstract

Objectives

Implementation studies are often poorly reported and indexed, reducing their potential to inform the provision of healthcare services. The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) initiative aims to develop guidelines for transparent and accurate reporting of implementation studies.

Methods

An international working group developed the StaRI guideline informed by a systematic literature review and e-Delphi prioritisation exercise. Following a face-to-face meeting, the checklist was developed iteratively by email discussion and critical review by international experts.

Results

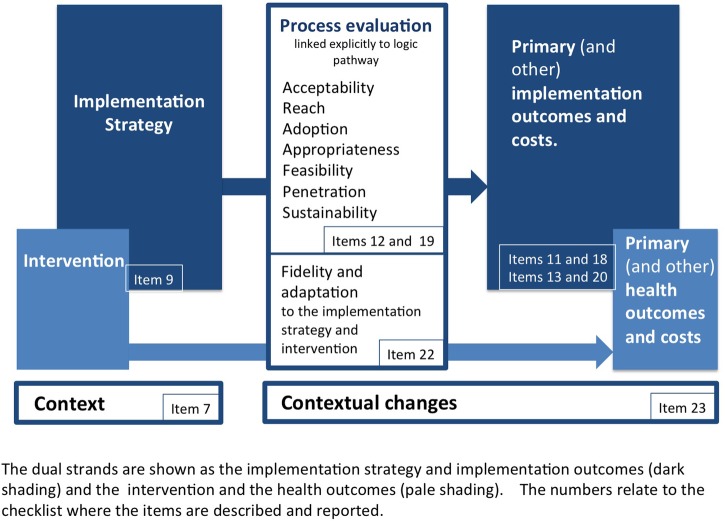

The 27 items of the checklist are applicable to the broad range of study designs employed in implementation science. A key concept is the dual strands, represented as 2 columns in the checklist, describing, on the one hand, the implementation strategy and, on the other, the clinical, healthcare or public health intervention being implemented. This explanation and elaboration document details each of the items, explains the rationale and provides examples of good reporting practice.

Conclusions

Previously published reporting statements have been instrumental in improving reporting standards; adoption by journals and authors may achieve a similar improvement in the reporting of implementation strategies that will facilitate translation of effective interventions into routine practice.

Keywords: Dissemination and implementation research, EQUATOR Network, Implementation Science, Reporting standards, Organisational innovation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We followed recommended methodology for developing health research reporting guidelines, including a literature review, an e-Delphi exercise, an international face-to-face consensus meeting and inviting expert feedback on draft versions of the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) checklist.

Implementation science is a broad field, and although the e-Delphi, working group and expert feedback enabled input from experts from a range of implementation science-related disciplines, we may have missed some perspectives.

Distance and financial constraints limited the geographical spread of representatives at the face-to-face consensus working group, but we invited feedback on the penultimate draft from experts from across the world.

Although our initial feedback suggests general agreement with the underlying concepts, the StaRI guidelines will need to be refined in the light of authors' and editors' practical experience of using the checklist.

Implementation science bridges the gap between developing and evaluating effective interventions and implementation in routine practice to improve patient and population health.1 Implementation studies are however often poorly reported and indexed,2 3 reducing their potential to inform the provision of healthcare services and improve health outcomes.4 The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) initiative aimed to develop standards for transparent and accurate reporting of implementation studies. The StaRI statement describing the scope and conceptual underpinning is published in the BMJ;5 this elaboration document provides detailed explanation of the individual items.

Methods

Following established guidelines,6 7 we convened a consensus working group in London at which 15 international multidisciplinary delegates considered candidate items identified by a previous systematic literature review and an international e-Delphi prioritisation exercise,8 in the context of other published reporting standards and the panel's expertise in implementation science. The resultant checklist was subsequently developed iteratively by email discussion, and feedback on the penultimate draft guideline sought from colleagues working in implementation science.

Scope of the StaRI reporting standards

Implementation research is the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of evidence-based interventions into practice and policy and hence improve health.9–11 The discipline encompasses a broad range of methodologies applicable to improving the dissemination and implementation of clinical, healthcare, global health and public health interventions.12–14 The StaRI checklist focuses primarily on standards for reporting studies that evaluate implementation strategies developed to enhance the adoption, implementation and sustainability of interventions,15 but some items may be applicable to other study designs used in implementation science.

The StaRI reporting guidelines

Unlike most reporting guidelines that apply to a specific research methodology, StaRI is applicable to the broad range of study designs employed in implementation science. Authors are referred to other reporting standards for advice on reporting specific methodological features. In an evolving field, in which there is a range of study designs, terminology is neither static nor used consistently.16 For clarity, we have adopted specific terms in this paper; table 1 defines these terms and lists some of the alternative or related terminology.

Table 1.

Terminology, definitions and resources

| Term used in this paper | Definition Sources of information |

Alternative terminology and similar concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation strategy | Methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation and sustainability of a clinical programme or practice14–16 | Implementation approach Implementation programmes Implementation process Implementation intervention |

| Exemplar resources: Consolidated Framework For Implementation Research (CFIR) http://www.cfirguide.org/imp.html Dissemination and implementation models http://www.dissemination-implementation.org/index.aspx | ||

| Implementation outcome | Process or quality measures to assess the impact of the implementation strategy, such as adherence to a new practice, acceptability, feasibility, adaptability, fidelity, costs and returns14 58 | End point |

| Intervention | The evidence-based practice, programme, policy, process, or guideline recommendation that is being implemented (or deimplemented).12 In the context of healthcare, this might be a preventive, diagnostic or therapeutic clinical practice, delivery system change, or public health activity being implemented to improve patient's outcomes, system quality and efficiency, or population health. | Treatment Evidence-based intervention |

| Health outcome | Patient-level health outcomes for a clinical intervention, such as symptoms or mortality; or population-level health status or indices of system function for a system/organisational-level intervention.14 | Health status Client outcome |

| Logic pathway | The manner in which the implementation strategy is hypothesised to operate | Logic model Causal pathway/model Mechanisms of action/impact Theory of change Driver diagrams Cause-and-effect diagram (Ishikawa, fishbone diagrams) Donabedian model |

| Exemplar resource: Logic models: https:/www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kellogg-foundation-logic-model-development-guide | ||

| Process evaluation | A study that aims to understand the functioning of an intervention, by examining its implementation, mechanisms of impact and contextual factors. Process evaluation is complementary to, but not a substitute for, high quality outcomes evaluation61 Process evaluation aims to describe the strategy for change as planned, the strategy as delivered, the actual exposure of the target population to the activities that are part of the strategy, and the experiences of the people exposed60 (Formative evaluation) is a rigorous assessment process designed to identify potential and actual influences on the progress and effectiveness of implementation efforts62 |

Formative evaluation |

| Exemplar resource: process evaluation of complex interventions. Available from https://www.ioe.ac.uk/MRC_PHSRN_Process_evaluation_guidance_final(2).pdf | ||

| ‘Barriers and facilitators’ | Aspects related to the individual (ie, healthcare practitioner or healthcare recipient) or to the organisation that ‘determine its degree of readiness to implement, barriers that may impede implementation, and strengths that can be used in the implementation effort’50 | Drivers Mediators, Moderators Contextual factors Enablers Organisational conditions for change |

Underpinning the StaRI reporting standards are the dual strands of describing, on the one hand, the implementation strategy and, on the other, the clinical, healthcare or public health intervention being implemented.17 These strands are represented as two columns in the checklist (see table 2). The primary focus of implementation science is the implementation strategy15 (column 1) and the expectation is that this will always be fully completed. The impact of the intervention on the target population should always be considered (column 2) and either health outcomes reported or robust evidence cited to support a known beneficial effect of the intervention on the health of individuals or populations. While all items are worthy of consideration, not all items will be applicable to or feasible in every study; a fully completed StaRI checklist may thus include a number of ‘not applicable’ items. For example, studies simultaneously testing a clinical intervention and an implementation strategy (Hybrid type 2 designs) would need to fully address both strands, whereas studies testing a clinical intervention while gathering information on its potential for implementation (Hybrid type 1) or testing an implementation strategy while observing the clinical outcomes (Hybrid Type 3) would focus primarily on items in the clinical intervention or implementation strategy columns, respectively.14

Table 2.

Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): the StaRI checklist

| Report the following | ‘Implementation strategy’ refers to how the intervention was implemented ‘Intervention’ refers to the healthcare or public health intervention that is being implemented |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Checklist item |

Implementation strategy

|

Intervention

|

|

| Title | 1 | Identification as an implementation study, and description of the methodology in the title and/or keywords | |

| Abstract | 2 | Identification as an implementation study, including a description of the implementation strategy to be tested, the evidence-based intervention being implemented and defining the key implementation and health outcomes | |

| Introduction | 3 | Description of the problem, challenge or deficiency in healthcare or public health that the intervention being implemented aims to address | |

| 4 | The scientific background and rationale for the implementation strategy (including any underpinning theory/framework/model, how it is expected to achieve its effects and any pilot work) | The scientific background and rationale for the intervention being implemented (including evidence about its effectiveness and how it is expected to achieve its effects) | |

| Aims and objectives | 5 | The aims of the study, differentiating between implementation objectives and any intervention objectives | |

| Methods: description | 6 | The design and key features of the evaluation (cross-referencing to any appropriate methodology reporting standards), and any changes to study protocol, with reasons | |

| 7 | The context in which the intervention was implemented (consider social, economic, policy, healthcare, organisational barriers and facilitators that might influence implementation elsewhere) | ||

| 8 | The characteristics of the targeted ‘site(s)’ (eg, locations/personnel/resources, etc) for implementation and any eligibility criteria | The population targeted by the intervention and any eligibility criteria | |

| 9 | A description of the implementation strategy | A description of the intervention | |

| 10 | Any subgroups recruited for additional research tasks, and/or nested studies are described | ||

| Methods: evaluation | 11 | Defined prespecified primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy, and how they were assessed. Document any predetermined targets | Defined prespecified primary and other outcome(s) of the intervention (if assessed), and how they were assessed. Document any predetermined targets |

| 12 | Process evaluation objectives and outcomes related to the mechanism(s) through which the strategy is expected to work | ||

| 13 | Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the implementation strategy | Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the intervention | |

| 14 | Rationale for sample sizes (including sample size calculations, budgetary constraints, practical considerations, data saturation, as appropriate) | ||

| 15 | Methods of analysis (with reasons for that choice) | ||

| 16 | Any a priori subgroup analyses (eg, between different sites in a multicentre study, different clinical or demographic populations), and subgroups recruited to specific nested research tasks | ||

| Results | 17 | Proportion recruited and characteristics of the recipient population for the implementation strategy | Proportion recruited and characteristics (if appropriate) of the recipient population for the intervention |

| 18 | Primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy | Primary and other outcome(s) of the intervention (if assessed) | |

| 19 | Process data related to the implementation strategy mapped to the mechanism by which the strategy is expected to work | ||

| 20 | Resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the implementation strategy | Resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the intervention | |

| 21 | Representativeness and outcomes of subgroups including those recruited to specific research tasks | ||

| 22 | Fidelity to implementation strategy as planned and adaptation to suit context and preferences | Fidelity to delivering the core components of intervention (where measured) | |

| 23 | Contextual changes (if any) which may have affected outcomes | ||

| 24 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group | ||

| Discussion | 25 | Summary of findings, strengths and limitations, comparisons with other studies, conclusions and implications | |

| 26 | Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the implementation strategy (specifically including scalability) | Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the intervention (specifically including sustainability) | |

| General | 27 | Include statement(s) on regulatory approvals (including, as appropriate, ethical approval, confidential use of routine data, governance approval), trial/study registration (availability of protocol), funding and conflicts of interest | |

Note: A key concept is the dual strands of describing, on the one hand, the implementation strategy and, on the other, the clinical, healthcare or public health intervention that is being implemented. These strands are represented as two columns in the checklist. The primary focus of implementation science is the implementation strategy (column 1) and the expectation is that this will always be completed. The evidence about the impact of the intervention on the targeted population should always be considered (column 2) and either health outcomes reported or robust evidence cited to support a known beneficial effect of the intervention on the health of individuals or populations. While all items are worthy of consideration, not all items will be applicable to or feasible within every study.

Elaboration on individual checklist items

Table 3.

Example of a table describing* an implementation strategy compiled from Kilbourne et al19 description of the implementation of life goals (LG): a clinical intervention for patients with mood disorders

| Name of discrete strategies | Assess for readiness to adopt LG intervention. Recruit champions and train for leadership | Develop and distribute educational materials, manuals, toolkits and an implementation blueprint | Educational meetings, outreach visits, clinical supervision, technical assistance, ongoing consultation | Facilitation (external and internal) and continuous implementation advice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | Investigators, representatives from practices and community | Investigators, trainers and LG providers designated at each site | Trainers and LG providers. | Investigators, external and internal facilitators (EF and IF), LG providers |

| Actions | Preimplementation meetings with site representatives for inservice marketing and dissemination of the LG programme: overview of LG evidence, benefits of LG and how to implement LG. Identify in each site at least one potential LG providers with a mental health background and internal facilitators. Identify champions. Assess readiness, barriers and facilitators | Packaging LG protocol and provider manual (identifying candidate patients; scripts for session and follow-up calls; registry for tracking patients’ progress). Design implementation: Implementation manual describing the ‘Replicating Effective Programs’ (REP) package. Patients’ workbook (exercises on behaviour change goals, symptom assessment, coping strategies…) | Training for LG providers: evidence behind LG, core elements and step-by-step walk through LG components; patient tracking and monitoring over time and continuous education via LG website. Programme assistance and LG uptake monitoring via LG website, support by study programme assistant, biweekly monitoring form, feedback reports and newsletters | Initiation and benchmarking: EF and LG providers identify barriers, facilitators, and goals. Leveraging: IF and LG providers identify priorities, other LG champions, and added value of LG to site providers. Coaching: IF, EF and LG providers phone to develop rapport and address barriers. Ongoing marketing: IF, leaders and LG providers summarise progress and develop business plans |

| Targets | Awareness of evidence-based interventions, engagement and settings’ readiness to change | Environmental context and resources, information and access to interventions | Build knowledge, beliefs, skills and capabilities: problem solving, decision-making, interest | Strengths and influences of LG provider. Measurable objectives and outcomes in implementing LG |

| Temporality | 1st step: preimplementation | 2nd step: REP implementation | 3rd step: training and start up | 4th step: maintenance/evolution |

| Dose | One informative meeting | For continuous use with every patient, as needed | 1-day 8 hour training programme+continuous assistance and monitoring | 2-day training programme EF and continuous facilitation activities |

| Implementation outcomes addressed/affected | Barriers, facilitators, specific uptake goals; organisational factors: ie, Implementation Leadership Scale, Implementation Climate Scale, resources, staff turnover, improved organisational capacity to implement, organisational support… | Organisational factors associated with implementation. Quality of the supporting materials, packaging and bundling of the intervention. Association of available materials’ quality with actual implementation Providers’ knowledge, skills trust |

RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) and LG performance measures of routine clinical care process: ie, sessions completed by patient, percentage completing 6 sessions… | IF, EF and LG provider's perceptions, strengths and opportunities to influence site activities and overcome barriers. Adaptation and fidelity monitoring: ie, number of meetings, opportunities to leverage LG uptake. Quality and costs |

| Theoretical justification | CDC's Research to Practice Framework. Social learning theory | REP framework and implementation strategy for community-based settings (includes Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations and Social Learning Theory) | Adaptive implementation.PARiHS framework | |

*Using Proctor et al's15 framework..

Item 1. Title.

Identification as an implementation study, and description of the methodology in the title and/or keywords

| Examples - Titles |

| Accessibility, clinical effectiveness, and practice costs of providing a telephone option for routine asthma reviews: phase IV controlled implementation study.18 |

| Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program.19 |

|

Explanation In addition to specifying the study design used (eg, cluster RCT, controlled before-and-after study, mixed-methods, economic evaluation, etc), it is important to identify the work explicitly as an implementation study, so that indexers, readers and systematic reviewers can easily identify relevant studies. The study design and ‘implementation study’ should both be included as key words and in the abstract. |

Item 2. Abstract.

Identification as an implementation study, including a description of the implementation strategy to be tested, the evidence-based intervention being implemented, and defining the key implementation and health outcomes.

| Examples - Abstracts |

| Background: Attendance for routine asthma reviews is poor. A recent randomised controlled trial found that telephone consultations can cost-effectively and safely enhance asthma review rates… Design of study: Phase IV controlled before-and-after implementation study. Setting: A large UK general practice. Method: Using existing administrative groups, all patients with active asthma (n = 1809) received one of three asthma review services: structured recall with a telephone-option for reviews versus structured recall with face-to-face-only reviews, or usual-care (to assess secular trends). Main outcome measures were: proportion of patients with active asthma reviewed within the previous 15 months… mode of review, enablement, morbidity, and costs to the practice.18 |

| Background: Good quality evidence has been summarised into guideline recommendations to show that peri-operative fasting times could be considerably shorter than patients currently experience. The objective of this trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of three strategies for the implementation of recommendations about peri-operative fasting. Methods: A pragmatic cluster randomised trial underpinned by the PARIHS framework was conducted during 2006 to 2009 with a national sample of UK hospitals using time series with mixed methods process evaluation and cost analysis. Hospitals were randomised to one of three interventions: standard dissemination (SD) of a guideline package, SD plus a web-based resource championed by an opinion leader, and SD plus plan-do-study-act (PDSA). The primary outcome was duration of fluid fast prior to induction of anaesthesia. Secondary outcomes included duration of food fast, patients' experiences, and stakeholders' experiences of implementation, including influences. ANOVA was used to test differences over time and interventions. Results: Nineteen acute NHS hospitals participated. Across timepoints, 3,505 duration of fasting observations were recorded. No significant effect of the interventions was observed for either fluid or food fasting times. The effect size was 0.33 for the web-based intervention compared to SD alone for the change in fluid fasting and was 0.12 for PDSA compared to SD alone. The process evaluation showed different types of impact, including changes to practices, policies, and attitudes. A rich picture of the implementation challenges emerged, including interprofessional tensions and a lack of clarity for decision-making authority and responsibility.20 |

|

Explanation For clarity of indexing and identification, the abstract should state clearly the study design and identify the work as an implementation study. In line with the concept of dual strands that underpins the StaRI checklist, the implementation strategy and the evidence-based intervention being implemented should be described. Other important information that should be included are the context, implementation outcomes, resource use and, if appropriate, health intervention outcomes. |

Item 3. Introduction (Identify the problem).

Description of the problem, challenge or deficiency in healthcare or public health that the intervention being implemented aims to address.

| Examples - Identify the problem |

| In the U.S., a substantial percentage of morbidity and mortality (about 37%) is related to four unhealthy behaviors: tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and risky alcohol use… Primary care clinicians have many opportunities to assist their patients in modifying unhealthy behaviors; however, they are hampered by inadequate time, training, and delivery systems.21 |

| Despite significant morbidity, attendance for routine asthma reviews is poor… Telephone consultations offer alternative access to routine asthma reviews, although a recent UK ruling decreed that the evidence base for this approach in asthma care was ‘insufficient’.18 |

|

Explanation Identifying and characterising the problem or deficiency that the intervention was designed to address may require data on, for example, the epidemiology of the condition, its impact on individuals or healthcare resources and evidence of a ‘research to practice’ gap (eg, actual performance rates). Characterising the challenge for implementation requires a description of the context in which the intervention will be implemented. This should include a summary of the key factors that might affect successful implementation in terms of the wider context (eg, governmental policies, major philosophical paradigms influencing decision makers, availability of resources) as well as barriers and enablers within the organisation and at individual professional level.9 |

Item 4. Introduction (Rationale: implementation strategy and intervention).

| The scientific background and rationale for the implementation strategy (including any underpinning theory/framework/model, how it is expected to achieve its effects and any pilot work). | The scientific background and rationale for the intervention being implemented (including evidence about its effectiveness and how it is expected to achieve its effects). |

|

Examples Rationale for the implementation strategy |

Rationale for the intervention |

| Facilitated rapid-cycle quality-improvement techniques (plan-do-study-act cycles [PDSA]) and learning collaboratives are effective in primary care settings, and the two strategies ought to be complementary.21 | … brief interventions delivered in primary care office settings have affected smoking cessation and alcohol consumption. Although less evidence supports brief interventions for improving diet or increasing exercise, there are reasons for optimism.21 |

| The Health Decision Model, which combines decision analysis, behavioral decision theory, and health beliefs, is useful to identify patient characteristics related to treatment adherence and subsequent blood pressure control… Successful implementation generally requires a comprehensive approach, in which barriers and facilitators to change in a specific setting are targeted.22 | If not properly controlled, elevated blood pressure (BP) can lead to serious patient morbidity and mortality… Inconsistent patient adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen is known to contribute to poor rates of BP control and improving medication adherence has been shown to be effective in improving BP.22 |

|

Explanation Authors of implementation studies need to explain the rationale for the choice of implementation strategy and for the validity of the intervention being implemented: | |

It is recommended that reporting the methods, outcomes and conclusions related to the implementation strategy precedes the corresponding reporting of the health outcomes of the intervention (because the key question in an implementation study is about the impact of the implementation strategy). However, authors may wish to reverse this in the introduction and establish that the intervention is effective before explaining the approach they took to implementing it. The use of hybrid study designs, which combine features of clinical effectiveness and implementation studies, may affect the relative emphasis that is placed on the implementation and health intervention aspects of trials.14 | |

Item 5. Aims and objectives.

The aims of the study, differentiating between implementation objectives and any intervention objectives.

| Example - Aim |

| The aim of our study is to evaluate the process and effectiveness of supported self-management (SMS) implemented as an integral part of the care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus provided by practice nurses. We will simultaneously address the following research questions: |

|

|

Explanation The aims and objectives should distinguish between the aim(s) of the implementation strategy and the aim(s) of the evidence-based intervention that is being implemented, possibly using two specific research questions as in the example.24 The aim of the intervention may be implicit if there is already strong evidence to support the health benefits of the intervention (eg, reducing smoking prevalence). |

Item 6. Methods: study design.

The design and key features of the evaluation (cross referencing to any appropriate methodology reporting standards) and any changes to study protocol, with reasons

| Examples - Study design |

| The trial was designed as an implementation study with a before and after analysis.25 |

| Implementation of Perioperative Safety Guidelines is a multicenter study in nine hospitals using an one-way (unidirectional) cross-over cluster trial design… It is impossible to deliver such a strategy simultaneously to all hospitals because of logistical, practical, and financial reasons. For that reason, a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial design is chosen.26 |

|

Explanation The study design should be identified and the rationale explained. Any important changes to the study protocol should be described (or the absence of changes confirmed). In contrast to most reporting standards, StaRI is applicable to a broad range of study designs, for example, cluster RCTs, controlled clinical trials, interrupted time series, cohort, case study, before and after studies, as well as mixed methods quantitative/qualitative assessments.2 A hierarchy of study design has been suggested in the context of studies implementing asthma self-management.4 Reporting standards exist for many of these designs such as cluster RCTs,27 pragmatic RCTs,28 observational studies,29 including use of routine data,30 non-randomised public health interventions,31 qualitative studies,32 as well as templates for describing interventions33 and local quality improvement initiatives.34 The StaRI checklist does not, therefore, include items related to specific design features (eg, randomisation, blinding, intracluster correlation, matching criteria for cohorts, data saturation). Authors are referred to appropriate methodological guidance on reporting these aspects of their study (available from http://www.equator-network.org). |

Item 7. Methods: context.

The context in which the intervention was implemented. (Consider social, economic, policy, healthcare, organisational barriers and facilitators that might influence implementation elsewhere).

| Examples - Context |

| The program occurred in three of 14 community-based networks that are part of the statewide Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC) program, an outgrowth of a two-decade effort in North Carolina to better manage the care of Medicaid patients through enhanced patient-centered medical homes. This public-private partnership has five primary components… developed to mirror the components of the Wagner Chronic Care Model for the organization of primary care. At a statewide level, CCNC is operated by North Carolina Community Care Networks, Inc. (NCCCN), a non-profit, tax-exempt organization that facilitates statewide contracting between the 14 CCNC networks and healthcare payers, including Medicaid and Medicare, and allows the participating regional networks to share information technology and other centralized resources. NCCCN also serves as a centralized resource for quality improvement, reporting, web-based case management system, practice support, and provider and member education.22 |

| All Italian citizens are covered by a government health insurance and are registered with a general practitioner. Primary care for diabetes is provided by general practitioners and diabetes outpatient clinics. Patients can choose one of these two ways of accessing the healthcare system, according to their preferences, or they can be referred to diabetes outpatient clinics by their general practitioners. The Italian healthcare system includes more than 700 diabetes outpatient clinics. The SINERGIA model is based on a process of disease monitoring and management that tends to exclude the intervention of the diabetologist in the absence of acute problems. Therefore, diabetologists gain time for patients with more severe diabetes, thus enabling them to provide highly qualified care to those patients.35 |

| Delivering a multifactorial intervention in our local setting is challenging. Data from a neighboring province showed marked underuse of proven therapies in subjects with diabetes. Furthermore, there is a shortage of physicians, especially in rural areas, while fee-for-service reimbursement may not favor optimal chronic disease management. Although the local prevalence of diabetes (currently 5.3%) is increasing, the greatest incidence and prevalence are in northern communities, which have the least access to specialists.36 |

|

Explanation Successful implementation of evidence into practice is a planned facilitated process involving the interplay between individuals, evidence and context to promote evidence-informed practice.37 A rich description of the context is critical to enable readers to assess the external validity of the study,38 and decide how the study context compares to their situation and if/how the implementation strategy might be transposed, or need adapting.39 Similarly, the social, political and economic context influences the ‘entrenched practices and other biases’ that hinder evidence-based deimplementation of unproven practices.40 41 The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CIFR) defines 39 constructs that may guide reporting of these contextual dimensions (http://www.cfirguide.org/imp.html). The constructs are clustered within five domains:9 42

Journal word restrictions will dictate how much detail can be included in the text, but authors should highlight all the key contextual barriers and facilitators that are likely to influence their implementation strategy and outcomes. The examples above highlight the policy context promoting patient-centred medical homes,22 the role of diabetologists that enabled a shift in care,35 and the shortage of specialists that challenged implementation.36 Additional information may be provided in an online supplementary file or a separate publication. |

Item 8. Methods: Targeted sites and populations.

| The characteristics of the targeted ‘site(s)’ (e.g. locations/ personnel/ resources etc.) for implementation and any eligibility criteria. | The population targeted by the intervention and any eligibility criteria. |

|

Examples Sites and population targeted by the implementation strategy |

Sites and population targeted by the intervention |

| This study comprises nine hospitals in the Netherlands: two academic, four tertiary teaching, and three regional hospitals, with 200 to up to more than 1,300 beds each. …we believe these hospitals represent the practice of Dutch hospital care.26 | The study focuses on patients undergoing elective abdominal or vascular surgery with a mortality risk ≥ 1%. These surgeries are selected because of the estimated higher risk of complications and hospital mortality…26 |

| The study will be implemented in public health facilities in Central and Eastern provinces in Kenya and in three regions in Swaziland… The two criteria for selecting intervention facility selection were: i) good performance in the previous study and ii) high throughput of family planning clients (≥100/month).43 | All clients entering the facility for MCH [maternal and child health] services over the five-day period will be asked to participate…43 |

|

Explanation Recruitment is considered at two levels:

| |

Item 9. Methods: Description.

| A description of the implementation strategy. | A description of the intervention |

|

Examples Description of the implementation strategy |

Description of the intervention |

| Implementation planning for this study began with the construction of multiple stakeholder partnerships within the VA PC-MHI program…. [and] was informed by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) framework…. Based on stakeholder feedback and project-team experiences, the implementation strategy for this trial was developed to include three separate but interrelated interventions—online clinician training, clinician audit and feedback, and internal and external facilitation… … emphasis has been placed on understanding stakeholder perspectives, using formative and process evaluations such that the implementation interventions could be modified as needed during the trial.44 |

The ACCESS intervention is a manualized brief CBT [Cognitive Behavioural Therapy] protocol that provides a flexible, patient-centered approach to increase patient engagement and adherence, while addressing both the mental and physical health needs of veterans [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure]. ACCESS consists of six weekly treatment sessions and two brief (10- to 15-minute) telephone “booster” sessions within a four month time frame. Participants are asked to attend the first session in person and can participate in subsequent sessions by telephone or in person.44 Detailed descriptive information about the content and processes of the ACCESS intervention can be found elsewhere.45 |

| Sites not initially responding to REP [Replicating Effective Programs] (defined as <50% patients receiving ≥3 EBP [evidence-based practice] sessions) will be randomized to receive additional support from an EF or both EF/IF [External/Internal Facilitator]. Additionally, sites randomized to EF and still not responsive will be randomized to continue with EF alone or to receive EF/IF. The EF provides technical expertise in adapting [Life Goals] in routine practice, whereas the on-site IF has direct reporting relationships to site leadership to support LG use.19 | The EBP to be implemented is Life Goals (LG) for patients with mood disorders across 80 community-based outpatient clinics… LG is a psychosocial intervention for mood disorders delivered in six individual or group sessions, which includes 10 components: self-management sessions, values, collaborative care, self-monitoring, symptom profile, triggers, cost/benefit analysis of responses, life goals, care management, and provider decision support. Based on social cognitive theory, LG encourages active discussions focused on individuals' personal goals that are aligned with healthy behavior change and symptom management strategies.19 |

|

Explanation Descriptions of implementation strategies and complex interventions are criticised as being inconsistently labelled, poorly described, rarely justified, not easy to understand15 46 47 and not sufficiently detailed to enable the intervention to be replicated.48 There needs to be a description of the implementation strategy and the intervention being implemented.

| |

Table 3.

Example of a table describing* an implementation strategy compiled from Kilbourne et al19 description of the implementation of life goals (LG): a clinical intervention for patients with mood disorders

| Name of discrete strategies | Assess for readiness to adopt LG intervention. Recruit champions and train for leadership | Develop and distribute educational materials, manuals, toolkits and an implementation blueprint | Educational meetings, outreach visits, clinical supervision, technical assistance, ongoing consultation | Facilitation (external and internal) and continuous implementation advice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | Investigators, representatives from practices and community | Investigators, trainers and LG providers designated at each site | Trainers and LG providers. | Investigators, external and internal facilitators (EF and IF), LG providers |

| Actions | Preimplementation meetings with site representatives for inservice marketing and dissemination of the LG programme: overview of LG evidence, benefits of LG and how to implement LG. Identify in each site at least one potential LG providers with a mental health background and internal facilitators. Identify champions. Assess readiness, barriers and facilitators | Packaging LG protocol and provider manual (identifying candidate patients; scripts for session and follow-up calls; registry for tracking patients’ progress). Design implementation: Implementation manual describing the ‘Replicating Effective Programs’ (REP) package. Patients’ workbook (exercises on behaviour change goals, symptom assessment, coping strategies…) | Training for LG providers: evidence behind LG, core elements and step-by-step walk through LG components; patient tracking and monitoring over time and continuous education via LG website. Programme assistance and LG uptake monitoring via LG website, support by study programme assistant, biweekly monitoring form, feedback reports and newsletters | Initiation and benchmarking: EF and LG providers identify barriers, facilitators, and goals. Leveraging: IF and LG providers identify priorities, other LG champions, and added value of LG to site providers. Coaching: IF, EF and LG providers phone to develop rapport and address barriers. Ongoing marketing: IF, leaders and LG providers summarise progress and develop business plans |

| Targets | Awareness of evidence-based interventions, engagement and settings’ readiness to change | Environmental context and resources, information and access to interventions | Build knowledge, beliefs, skills and capabilities: problem solving, decision-making, interest | Strengths and influences of LG provider. Measurable objectives and outcomes in implementing LG |

| Temporality | 1st step: preimplementation | 2nd step: REP implementation | 3rd step: training and start up | 4th step: maintenance/evolution |

| Dose | One informative meeting | For continuous use with every patient, as needed | 1-day 8 hour training programme+continuous assistance and monitoring | 2-day training programme EF and continuous facilitation activities |

| Implementation outcomes addressed/affected | Barriers, facilitators, specific uptake goals; organisational factors: ie, Implementation Leadership Scale, Implementation Climate Scale, resources, staff turnover, improved organisational capacity to implement, organisational support… | Organisational factors associated with implementation. Quality of the supporting materials, packaging and bundling of the intervention. Association of available materials’ quality with actual implementation Providers’ knowledge, skills trust |

RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) and LG performance measures of routine clinical care process: ie, sessions completed by patient, percentage completing 6 sessions… | IF, EF and LG provider's perceptions, strengths and opportunities to influence site activities and overcome barriers. Adaptation and fidelity monitoring: ie, number of meetings, opportunities to leverage LG uptake. Quality and costs |

| Theoretical justification | CDC's Research to Practice Framework. Social learning theory | REP framework and implementation strategy for community-based settings (includes Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations and Social Learning Theory) | Adaptive implementation.PARiHS framework | |

*Using Proctor et al's15 framework..

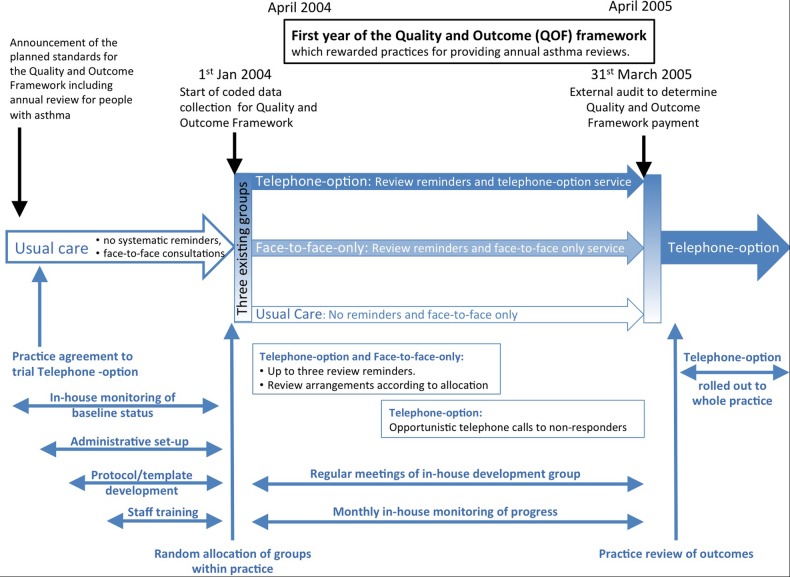

Figure 1.

Example of a timeline describing an implementation strategy (compiled from Pinnock et al18 description of the implementation of a telephone service for providing asthma reviews). Note: The three-arm implementation study is illustrated in the centre of this schema with the preceding usual care, randomisation on 1 January 2004, the 15-month intervention and subsequent roll-out. The context (specifically the introduction of the Quality and Outcome Framework) is shown at the top of the schema. Below the three-arms of the study are the components of the implementation strategy from set-up and training, ongoing service provision and maintenance and adoption into routine practice.

Figure 2.

Summary of outcomes and the related items in the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies checklist.

Item 10. Methods (subgroups).

Any subgroups recruited for additional research tasks, and/or nested studies are described

| Examples - Subgroups |

| Observations of client–provider interactions: 18 consecutively sampled new family planning/HIV clients and 18 revisit clients … will be observed. For the postnatal clinic/HIV model … 24 consecutively sampled postpartum women (within 48 hours of birth, between 1–2 weeks and around 6 weeks postpartum) per study facility (will be recruited)43 |

| Researchers posted the following validated questionnaires, with two reminders, to patients with active asthma in the three groups at the end of the study year (excluding children aged <12 years, as the questionnaires are not validated for this age group). The only exclusion criteria were a predominant diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inability to complete the questionnaire (eg, because of severe dementia), and patients excluded by their GP for significant medical or social reasons18 |

|

Explanation Typically in implementation studies, the people targeted by the intervention (eg, patients with a condition registered with a practice or healthcare organisation; population targeted by a public health initiative) will not have consented to the research. Some studies may recruit a subgroup of patients to undertake specific research activities. For example, a proportion of consultations may be observed (see the first example43), a random sample of patients provided with a new service may be asked to complete questionnaires (see the second example18) or a purposive sample of stakeholders may be recruited for a qualitative study. The recruitment process for these subgroups should be clearly described. |

Item 11. Methods: Outcomes.

| Defined pre-specified primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy, and how they were assessed. Document any pre-determined targets. | Defined pre-specified primary and other outcome(s) of the intervention (if assessed), and how they were assessed. Document any pre-determined targets. |

|

Examples Outcomes of the implementation strategy |

Outcomes of the intervention |

| The primary outcome measure is guideline adherence according to the perioperative Patient Safety Indicators as defined in the national indicator set. This set comprises nine indicators on the processes and structures of care.26 | Secondary (patient) outcomes are in-hospital complications (with particular attention to postoperative wound infections) and hospital mortality, as well as length of hospital stay, unscheduled transfer to the intensive care unit, non-elective hospital readmission, and unplanned reoperation…26 |

| Implementation outcomes To assess brief cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) adoption and fidelity, as measured by: a) brief CBT patient engagement (one or more sessions) and adherence (four or more sessions) b) Department of Veterans Affairs Primary Care-Mental Health Integration [VA PC-MHI] clinician brief CBT adherence and competency ratings as evaluated by expert audio session reviews.44 |

Effectiveness outcomes: To determine whether a brief CBT treatment group as provided by VA PC-MHI clinicians is superior to a usual-care control group at post treatment and 8- and 12-month follow-ups, as measured by: a) depression and anxiety scores (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Beck Anxiety Inventory) b) cardiopulmonary disease outcomes (Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire).44 |

|

Explanation Figure 2 illustrates the outcomes relevant to implementation science and the StaRI checklist items to which they relate. This schema borrows from the conceptual models and taxonomy of outcomes described by Proctor et al,16 57 58 but also highlights the dual strands suggested by the StaRI guideline as underpinning reporting implementation intervention studies. The outcomes are mapped to the checklist items in which they are described or reported. The outcomes related to the implementation strategy should be distinguished from outcomes of the intervention:

All outcomes should be clearly defined, including the time point at which they are measured in relation to delivery of the implementation strategy, to enable interpretation of findings in the context of an evolving process of adoption of the intervention within organisations and also inform sustainability. Not all implementation studies will designate a ‘primary outcome’, but this is of sufficient importance in the context of experimental designs that the terminology has been retained (see table 2 for alternative terms). This also serves to distinguish implementation outcomes on which a study is powered from the data collected during a process evaluation (see item 12). Feasibility studies may focus on process rather than primary implementation or health outcomes. The provenance of data is of particular importance in implementation studies in which participants may not be recruited to the research. For example, routine data are typically collected for purposes other than research and the intended use (clinical records, insurance claims, referral patterns, workload monitoring) will influence what and how data are recorded. A description should be provided of the provenance of the data (data source/purpose and process of collection/data completeness) and validity of coding.30 It is good practice to define the minimum change that would be considered as representing implementation success (eg, 70% participation in the intervention) and justify that choice of level. | |

Item 12. Methods: Process evaluation.

Process evaluation objectives and outcomes related to the mechanism by which the strategy is expected to work.

|

Examples Process evaluation | |

| The outcomes reported in this paper include adoption, implementation, and maintenance from the Reach, Efficacy/Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) Model Adoption was defined as the percentage of clinicians invited to participate who completed training and implemented recommended changes. Implementation [of the intervention] was determined by how well the practices were able, during each 6-month cycle, to fully incorporate screening and very brief and brief interventions for each behavior into their processes of care, based on information obtained from the chart audits. Maintenance was determined by the degree to which practices continued to screen for and provide interventions while working on the other behaviors.21 | |

| In this framework (Hulscher et al.60), attention is paid to features of the target group, features of the implementers, and the frequency and intensity of intervention activities. Based on this framework we describe the features of the intervention as performed in detail. The process evaluation will furthermore be based on a questionnaire for the contact persons and a questionnaire for the health-care providers to measure their experience with the implementation strategy..”26 | |

|

Explanation A process evaluation (or formative evaluation) is used to describe the implementation strategy as delivered, and to assess and explore stakeholder experience of the process of implementation and/or target population experiences of receiving the intervention.60–62 A process evaluation should be based on an explicit hypothesis (eg, ‘logic pathway’; see table 2 for alternative terminology) that spans the mechanism of action of the implementation strategy and the mechanism by which the intervention is expected to improve healthcare. Process data should be related to the hypothesised mechanisms. This implies that data may need to be collected at multiple time points to capture an evolving process, and the relationship between the researcher undertaking the process evaluation and the implementation process (eg, whether interim results are fed back to facilitate adaptation) should be described.61 62 Context (see item 7) may be reported as a component of the process evaluation. For each process evaluation outcome:

Frameworks such as RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance),63 diffusion of innovation,64 routinisation,65 NPT (Normalisation Process Theory),66 Framework for process evaluation of cluster-randomised controlled trials (RCT)67 or Stages of Implementation Completion,68 CIFR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research),9 42 Theoretical Domains Framework69 may be useful in developing, analysing and reporting process evaluations. |

Item 13. Methods: Economic evaluation.

| Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the implementation strategy | Methods for resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the intervention |

|

Examples Economic evaluation of the implementation strategy |

Economic evaluation of the intervention |

| Cost analysis of developing and implementing the three interventions from a national perspective (cost of rolling out a particular intervention across the NHS)…20 | … from the perspective of a single trust (cost of all activity and resource used by trust employees in implementation)20 |

| Financial data were obtained for the costs of setting up and running the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service for the 2 years of the study, including training, equipment, facilities and overheads, to provide estimates of the costs associated with IAPT. Set-up costs were a small proportion of total costs (less than 10%) and these were therefore apportioned to this 2-year period rather than the lifetime of the service.70 | The service recorded contact … time in minutes for each service user and this was used to calculate total contact time over the 2 years, which was combined with total cost data to generate an average cost per minute for the IAPT service… All health and social care services [were] valued using national unit costs. A broader perspective of costs was taken by assessing productivity impact, which we valued using the lost number of days from work using a human capital approach.70 |

|

Explanation Economic evaluation can inform future implementation and commissioning decisions. Reporting should adhere to existing guidelines relevant to the study design (eg, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) task force guidelines for economic evaluation (including model-based economic evaluation)71 and budget impact analysis,72 and guidance on social return on investment approaches73). This may require an online supplementary file or a separate publication. An additional requirement in reporting implementation research is to relate economic information to the implementation strategy or the intervention that is being implemented. If possible, reporting should distinguish between the two, with the practicality of doing so ideally having been considered at design stage. A budget impact analysis estimates changes in the expenditure of a healthcare system after adoption of a new intervention, and will be of particular interest to those who plan healthcare budgets.72 Reporting should be transparent and cover the following aspects of the evaluation, as relevant:

| |

Item 14. Methods: sample size.

Rationale for sample sizes (including sample size calculations, budgetary constraints, practical considerations, data saturation, as appropriate)

|

Example Sample size |

| Assuming an alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.90, an improvement in perceived daily functioning (defined as a score less than or equal to 4 on the Daily Functioning Thermometer, our primary outcome) at T12 occurring in 20% of the patients in the intervention group versus 5% of those in the control group requires at least a net number of 116 patients per arm (N=232; 5 patients per practice nurse). It will be necessary to take account of a possible dependence between observations on patients of the same practice nurse (PN). The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) is assumed to be 0.04, a median value for cluster-RCTs in the primary care setting.33 Assuming a 30% loss to follow-up we need to recruit at least 331 patients (8 per PN). Since participation in the screening procedure will not necessarily mean that patients also give informed consent for the effect evaluation, 10 consecutive patients for each PN will be invited to participate in the effect evaluation (N=460).24 |

|

Explanation It is important to recruit sufficient participants to be able to address the study's implementation objectives; the rationale for the number of sites and/or people recruited to the study needs to be justified. In a trial (eg, a cluster RCT), this will be based on a sample size calculation using the primary implementation outcome. If health outcomes are also being assessed, consideration may need to be given to the sample size for the primary health outcome. Design-specific advice on reporting sample size calculations can be found in relevant reporting standards.27–29 31 75 In studies using qualitative methodology, data saturation may inform the final sample size. Budgetary constraints and other pragmatic considerations may also be relevant (such as evaluating an initiative in which size is already determined; in the second example, the sample was ‘all active asthmatics’ in the practice18). |

Item 15. Methods: analysis.

Methods of analysis (with reasons for that choice)

|

Example Analysis |

|

Numerical data Analysis was conducted at the cluster level for each Trust… At each time-point, the differences in mean fasting times between the three intervention groups were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A repeated measure ANOVA across the time-point means for all trusts, within each intervention group, was conducted. The trend coefficient was not significantly different to zero: there was no evidence of trend over time pre-or post-intervention therefore data were combined across timepoints (1 to 4 and 5 to 8) and simple pre- and post-interventions comparisons were conducted using t-tests. The significance level used for all tests was 5%. The effect size was calculated for each of the web-based and PDSA interventions compared to standard deviation for change in fluid fasting time between pre- and post-intervention…. Patient experience questionnaires were analysed in SPSS using descriptive statistics, chi squared tests were used to compare characteristics pre- and postintervention…. Descriptive and inferential statistics were conducted (on learning organisational data]. Qualitative data Audio-recorded individual and focus group interviews were transcribed in full. Data were analysed within data set and managed in N*DIST 5 (pre-intervention) and NVIVO 7 (post-intervention). A combined inductive and deductive thematic analysis process was used…. Synthesis The theoretical framework [developed for this study is based on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework guided the integration of findings across data sets.20 |

|

Explanation Design-specific advice on reporting analysis can be found in relevant standards.27–29 31 32 75 Consideration needs to be given to the analysis of primary implementation outcomes and then (if measured) to any health outcomes. In mixed methods studies, clarity is needed about how different data types (numeric, qualitative) will be managed and analysed.76 The synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data will be guided by the study's question(s) or objective(s), and by its overarching theoretical framework or theory. Reporting should describe and explain implementation processes (eg, delivery of intervention, facilitators, barriers), contexts (eg, characteristics and influence of) and impacts. |

Item 16. Methods: Sub-group analyses.

Any a priori sub-group analyses (e.g. between different sites in a multicentre study, different clinical or demographic populations), and sub-groups recruited to specific nested research tasks

| Example - Subgroups |

| Planned subgroup analyses focus on subgroups of young women. Age is a core issue in gender violence and HIV incidence. … A further subgroup analysis will examine the effect of the presence of other programmes for HIV prevention, youth empowerment and reduction in gender violence active in the clusters, with this information collected at the time of the impact survey77 |

|

Explanation Subgroups should be specified a priori and the method of subgroup analysis clearly specified. Further detail on reporting analysis of data from subgroups is available in design-specific reporting standards.27–29 31 75 |

Item 17. Results: Populations.

| Proportion recruited and characteristics of the recipient population for the implementation strategy. | Proportion recruited and characteristics (if appropriate) of the recipient population for the intervention |

|

Examples Characteristics of recipients of the implementation strategy |

Characteristics of recipients of the intervention |

| Six practices were classed as rural, seven as urban. Practice list size ranged from 2,300 to 12,500 (median=7,500, IQR 5,250-10,250). Four urban and three rural practices were randomly assigned to the intervention group.78 | 4,434 adult (age range 18 to 55 years) patients with an asthma diagnosis made more than 12 months previously were identified…. A total of 1572 patients, who had received repeat prescriptions for β2-agonists in the previous 12 months, were defined as active asthma patients. Of these, 667 (42%) were considered to have poorly controlled asthma…78 |

| Forty-three practices were randomized: 22 to the intervention group and 21 to control. Massachusetts practices were a mix of hospital clinics, independent community health centers, and private practices. In Michigan, all sites were a part of the Henry Ford Health System; 1 was hospital-based. …There were no significant differences in practice characteristics between intervention and comparison groups.79 | The 43 practices identified a total of 13 878 pediatric patients with asthma who may have been eligible for this study. …Unexpectedly, at baseline, 53% of the children in the intervention group had a written asthma management plan, compared with 37% of the children in the control group (P0.001). The groups were not different at baseline with respect to any other measure.79 |

|

Explanation As in cluster RCTs, the populations need to be considered at two levels:

At each level, reach (the proportion of eligible population who participated and their characteristics) needs to be reported. A diagram illustrating the flow of targeted/participating sites, professionals and patients may be helpful, potentially adapted from CONSORT standards for cluster RCTs.27 Published examples of diagrams include a cohort study;80 a controlled implementation study18 and a before and after study.79 | |

Item 18. Results: Outcomes.

| Primary and other outcome(s) of the implementation strategy. | Primary and other outcome(s) of the Intervention (if assessed) | |

|

Examples Primary (and other) outcomes of the implementation strategy |

Primary (and other) outcomes of the intervention (if assessed |

|

| The Assessment of Chronic Illness Care measurements, obtained at the beginning, midpoint and end of the initiatives, provide evidence of the progressive implementation of the components of the CCM [Chronic Care Model]. These results are described using a spider diagram.81 | Changes in measures of disease control were more modest…. Nevertheless, tracking aggregate data by means of Shewhart p charts showed special cause variation reflecting improvement in blood pressure and [cholesterol] control in the late stages of the California Collaborative. Significant changes were not seen in HbA1c levels.81 | |

| There were 4,550 individuals who met inclusion criteria of which 558 individuals were contacted and received at least a phone contact… On average, individuals received 4.5 phone contacts over the 6-month intervention period.22 | During the 90 days prior to the first intervention encounter (index date), 35% of patients were >80% adherent to hypertension medication. By the period of 90–179 days following the first encounter, 54% had >80% adherence for hypertension medication.22 | |

|

Explanation We suggest that the primary and other outcomes of the implementation strategy are presented before the impact of the intervention on primary and other health outcomes (if measured). Authors are referred to design-specific standards for detailed advice on reporting outcomes.27–31 |

||

Item 19. Results: Process evaluation.

Process data related to the implementation strategy mapped to the mechanism by which the strategy is expected to work.

|

Examples Process data |

| The Park County Diabetes Project made a number of changes in the delivery of diabetes care and patient education. These included establishing and maintaining patient registries; nurses conducting mail and telephone outreach to patients in need of services; mailing personalized patient education materials regarding the ABCs of diabetes; and providing ongoing continuing education workshops for the health care team. The team redesigned the education curriculum …, provided group education sessions in community settings, and offered classes regardless of the person's ability to pay. The diabetes nurse in each clinic also provided one-on-one diabetes education. In October 2000, there were 320 patients with diagnosed diabetes receiving care at these clinics, and that number increased to 392 by February 2003. Among (participating) patients, the proportion receiving an annual foot examination, influenza immunization, and a pneumococcal immunization increased significantly from baseline to follow-up.82 |

| We identified three sub-themes that clearly distinguished low from high implementation facilities. First, the high quality of working relationships across service and professional … boundaries was apparent in the high implementation facilities… … The MOVE! teams at the two high implementation and transition facilities met regularly… … In the low implementation facilities, communications were poor between staff involved with MOVE! and they did much of their communication through email, if at all.83 |

|

Explanation Process evaluation should be related to the logic pathway, capturing the impact of the implementation strategy on intermediate/process outcomes on the pathway, as in the second example in which existing good communication facilitated implementation. It will be important to capture the involvement of the stakeholders in the process of design and implementation (eg, in the first example where the team redesigned the existing education curriculum). Data of importance to the main ‘outcome’ are likely to include uptake of and attrition from training, implementation tasks, etc, with explanatory insights from qualitative evaluation (eg, in the second example). Contextual changes (see item 23) may be reported as a component of the process evaluation. If health outcomes are reported, uptake of the intervention by the eligible population will be crucial (as in the first example). Additional papers may be necessary to report all aspects of process data, and to ensure that some publications directly focus on issues of importance to specific groups (eg, policymakers, healthcare managers).61 |

Item 20. Results: economic evaluation.

| Resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the implementation strategy | Resource use, costs, economic outcomes and analysis for the intervention |

|

Examples Health economic outcomes (Implementation strategy) |

Health economic outcomes (Intervention) |

| Estimated total up-front investment for this Coordinated-Transitional Care (C-TraC) pilot was $300 per person enrolled, which includes all staff, administrative, and implementation costs.84 | … given the observed decrease in re-hospitalizations of 5.8% versus the comparison group, it is estimated that the C-TraC program avoided 361.6 days in acute care over the first 16 months, leading to an estimated gross savings of $1,202,420. After accounting for all program costs, this led to estimated net savings of $826,337 overall or $663 per person enrolled over the first 16 months of the program…84 |

| In the base-case analysis, the difference in costs between intervention and control group was £327, and the difference in QALYs was 0.027, which generated an ICER point estimate of £12 111 per QALY gained. The probability of the intervention being cost effective was 89% at the NICE threshold of £30 000 per QALY.85 | |

|

Explanation Reporting of economic results should adhere to existing relevant guidelines.71 72 It should be clear whether the economic results relate to the implementation strategy, the intervention that is being implemented or both. Reporting should be transparent and cover the following aspects of the evaluation:

| |

Item 21. Results: subgroups.

Representativeness and outcomes of subgroups including those recruited to specific research tasks

|

Example Representativeness of sub-group |

| 236 (37% of the 629 patients with poorly-controlled asthma) patients consented to provide questionnaire data. One hundred and six (45%) patients were from control practices, and 130 (55.1%) were from intervention practices. Patients with asthma who consented to provide baseline questionnaire data were significantly older, more likely to be female and more affluent than non-consenters. They had significantly fewer β2 agonists inhaler or courses of oral steroids prescribed in the 12 months pre-study than non-consenters. One hundred and seventy-seven questionnaires were returned at follow-up out of a possible 236 (75%). Of these, 78/106 (74%) were returned by control practice patients and 99/130 (76%) from intervention practice patients.78 |

|

Explanation Subgroup analyses should be distinguished from outcomes from whole populations (eg, by reporting in a separate table) and their representativeness compared with the whole eligible population. |

Item 22. Results: Fidelity and adaptation.

| Fidelity to the implementation strategy as planned and adaptation to suit context and preferences. | Fidelity to delivering the core components of intervention (where measured). |

|

Examples Fidelity and adaptation to the implementation strategy |

Fidelity and adaptation to the intervention |

| Although practices were expected to participate fully in the intervention, actual participation varied considerably. Attendance at the 3 learning sessions declined progressively from the first to the third in both states (eg, 34 participants at the first session in Boston; 24 at the third). On average, only 42% of the practices submitted performance data … with fewer practices reporting in the later months of the intervention.79 | |

| At AD [academic detailing] visit 3… … 46% of the PDAs [personal digital assistants] indicated that the provider had discontinued use between visits 2 and 3. …Several providers reported that, once they adopted electronic medical record systems, they were less inclined to enter data into the PDA (to avoid having to interface with 2 different computers).86 | [Intervention: adherence to National Cholesterol Education Program clinical practice guidelines] Appropriate management of lipid levels decreased slightly (73.4% to 72.3%) in intervention practices and more markedly (79.7% to 68.9%) in control practices. The net change in appropriate management favored the intervention (+9.7%; 95% confidence interval.86 |

|

Explanation Fidelity may be considered at two levels: implementation fidelity and intervention fidelity. Implementation fidelity refers to the degree of adherence to the described implementation strategy. Intervention fidelity is the degree to which an intervention is implemented as prescribed in the original protocol. The implementation strategy and the intervention, however, may need to be adapted if they are to fit within the routines of local practice.86 Adaptation is the degree to which the strategy and intervention are modified by users during implementation to suit local needs.26 Insufficient fidelity to the ‘active ingredients’ of an intervention dilutes effectiveness,87 whereas insufficient adaptation stifles tailoring potentially diluting effective implementation.88 An approach to reporting these apparently contradictory concepts is to define the core components of an intervention to which fidelity is expected, and those aspects which may be adapted by local sites to aid implementation.59 87 Distinction may be made between an active process of innovative adaptation that facilitates implementation, passive ‘drift’ in which tasks are allowed to lapse,89 and active subversion which blocks implementation.90 Fidelity should be reported:

| |

Item 23. Results: context.

Contextual changes (if any) which may have affected the outcomes

|

Example Contextual changes |

| The present study coincided with the introduction of the UK General Medical Services contract in January 2004 which rewards practices who achieve clinical standards, including a target of 70% for the annual review of people with ‘active’ asthma. The impact of this was seen in the usual-care group which increased the review rate by 14% without a structured recall service.18 |

|

Explanation There should be a description of any important contextual changes (or not) occurring during the study that may have affected the impact of the implementation strategy—for example, policy incentives, parallel programmes, changes in personnel, media publicity. The CIFR constructs (see item 7) is a useful framework for describing context,42 and a timeline (see item 9) may be a convenient way to illustrate potential impact of contextual changes. Contextual changes (see item 19) may be reported as a component of the process evaluation. |

Item 24. Results: harms.

All important harms or unintended effects in each group.

|

Example Reporting of harms |

| [In the context of a computerised decision support to improve prescribing in pregnancy] Two factors contributed to alerts being based on incorrect patient pregnancy status: either the updated diagnosis had not been coded into administrative data at all or transfer of the updated coded diagnosis information from hospital administrative data to health plan administrative data was delayed.92 |

|

Explanation Adverse or unintended consequences of implementation studies are often under-reported.93–95 Any important harms or unintended effects should be reported, quantified (eg, on health outcomes, organisational efficiency or user satisfaction) and possible reasons identified (eg, flaws in the intervention, context challenging implementation).91 |

Item 25: Discussion: summary.

Summary of findings, strengths and limitations, comparisons with other studies, conclusions and implications.

|

Example Summary findings |

| The participating practices adopted most elements of the CCM [Chronic Care Model], including development of inter-professional teams, delegation of provision of care by appropriate team members, implementation of patient self-management strategies, group visits, proactive patient management—anticipating the needs of patients as opposed to providing reactive management—and use of an information system to track individual patient measures. In addition, resident training programs successfully incorporated educational strategies for learning the elements of evidence-based chronic illness care.81 |

|

Explanation The structure of the discussion will follow the style of the journal, but ideally should include summary of findings, strengths and limitations, comparisons with other studies, implications (see item 26) and conclusions.96 |

Item 26. Discussion: Implications.

| Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the implementation strategy (specifically including scalability). | Discussion of policy, practice and/or research implications of the intervention (specifically including sustainability). |

|

Examples Implications related to the implementation strategy |

Implications related to the intervention |

| These initiatives suggest that both the practice redesign required for implementation of the CCM [Chronic Care Model] and linked educational strategies are achievable in resident continuity practices…. Durable implementation of the CCM in resident practices necessitates substantial commitment from local institutional, clinical and academic leadership.81 |

…the modest improvement in clinical outcomes observed in these practices in comparison with initiatives from single site initiatives reported in the literature suggests that effective care of patients with chronic illness may require prolonged continuity of care that poses a challenge in many resident practices, even in those committed to implementation of the CCM.81 |