Abstract

Methionine ranks among the amino acids most sensitive to oxidation, which converts it to a racemic mixture of methionine-S-sulfoxide (Met-S-SO) and methionine-R-sulfoxide (Met-R-SO). The methionine sulfoxide reductases MsrA and MsrB reduce free and protein-bound MetSO, MsrA being specific for Met-S-SO and MsrB for Met-R-SO. In the present study, we report that an Escherichia coli metB1 auxotroph lacking both msrA and msrB is still able to use either of the two MetSO enantiomers. This indicates that additional methionine sulfoxide reductase activities occur in E. coli. BisC, a poorly characterized biotin sulfoxide reductase, was identified as one of these new methionine sulfoxide reductases. BisC was purified and found to exhibit reductase activity with free Met-S-SO but not with free Met-R-SO as a substrate. Moreover, a metB1 msrA msrB bisC strain of E. coli was unable to use Met-S-SO for growth, but it retained the ability to use Met-R-SO. Mass spectrometric analyses indicated that BisC is unable to reduce protein-bound Met-S-SO. Hence, this study shows that BisC has an essential role in assimilation of oxidized methionines. Moreover, this work provides the first example of an enzyme that reduces free MetSO while having no activity on peptide-bound MetSO residues.

Methionine is the amino acid most sensitive to reactive oxygen species. Oxidation converts it to methionine sulfoxide (MetSO) and eventually to methionine sulfone (31). Oxidation of Met actually yields two stereoisomeric forms, referred to as Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO. With a few exceptions, eukaryotes, archaea, and prokaryotes all synthesize methionine sulfoxide reductases (Msr) which are able to reduce both free and protein-bound MetSO back to Met. There are two classes of Msr, referred to as MsrA and MsrB, which reduce Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO, respectively (1, 10, 13, 17, 24). MsrA and MsrB are examples of a remarkable case of convergent evolution because they show no homology at either the primary or the structural level.

Both free Met and protein-bound Met residues are oxidized upon exposure to reactive oxygen species. Oxidation of protein-bound Met residues has been the focus of numerous recent studies because it can lead to loss of function, and it may be a primary cause of various pathological conditions and aging (3, 14, 16, 26, 28). In contrast, oxidation of free Met has not received much attention despite the fact that free Met is essential for protein synthesis and can be used as a source of nutrients. Conceivably, endogenously synthesized Met may be oxidized by reactive oxygen species derived from aerobic metabolism, while exogenous Met may be oxidized by environmental agents such as radiation or host-released reactive oxygen species. An outcome of either case could be a shortage of Met, affecting overall cellular metabolism.

The purpose of the present study was to identify enzymes in E. coli that are involved in the assimilation of MetSO and to evaluate their impact on methionine homeostasis. Surprisingly, the double msrA msrB mutant was still able to utilize MetSO, pointing to the existence of additional Msr activities in the cell. BisC, a poorly characterized biotin sulfoxide reductase, was identified as one of these new methionine sulfoxide reductases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Unless noted otherwise, chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Bacteria were grown aerobically at 37°C on Luria-Bertani or M9 minimal medium supplemented with methionine-S-sulfoxide (Met-S-SO) or methionine-R-sulfoxide (Met-R-SO) when necessary. Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO were a gift from G. Branlant (University of Nancy, Nancy, France). To maintain plasmids, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml. When necessary, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM) or arabinose (0.2%) was added to induce gene expression.

Strain construction.

A bisC deletion-containing strain was constructed by replacing the bisC gene with a kanamycin resistance cassette from plasmid pKD4 in strain BW25113/pKD46, as previously described (2). The msrA and msrB mutants were described before (7). Mutations were transferred between different strains by transduction with phage P1 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | φ80d lacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyr A96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega |

| BL21 (DE3) | F−ompT hsdS (rB− mB−) gal dcm(DE3) | Novagen |

| BW25113 | lacIqrrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16hsdR514 ΔaraBADAH33 ΔrhaBADLD78 | 2 |

| MC4100 | araD139 Δ (argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 thi fibB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR | Promega |

| HMS174 (DE3) | F−recA hsdR (rK12− mK12+) Rifr(DE3) | Novagen |

| LCB303 | MC4100 metB1 | Lab collection |

| BE54 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::SpcrmsrB::Cmr | 7 |

| Tp1000 | MC4100 ΔmobAB Kanr | 18 |

| BE72 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::SpcrmsrB::Cmr ΔmobAB::Kanr | This study |

| JB02 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::Spcr | This study |

| JB07 | BW25113 bisC::Kanr | This study |

| JB08 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::SpcrmsrB::CmrbisC::Kanr | This study |

| JB09 | MC4100 metB1 bisC::Kanr | This study |

| JB11 | MC4100 metB1 trxA::Kanr | This study |

| JB308 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::SpcrmsrB::CmrbisC::Kanr/pBis2 | This study |

| JB309 | MC4100 metB1 msrA::SpcrmsrB::CmrbisC::Kanr/pBis1 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJBis | pET21a+, BisCorf2 (His6 tag), Ampr | This study |

| pBis1 | pBad24, BisC(orf1), Ampr | This study |

| pBis2 | pBad24, BisC(orf2), Ampr | This study |

| pMsrA | pUC18, MsrA Ampr | 7 |

| pKD46 | Ampr | 2 |

| pKD4 | Kanr | 2 |

Plasmid construction.

DNA fragments containing bisC(ORF1) and bisC(ORF2) were amplified from chromosomal DNA of E. coli MG1655 by PCR, and the oligonucleotides bis1N (5′-GGGCCATGGCAGAAAACTCCTTGCAGAGCGC-3′), bis2N (5′-GGGCCATGGCCAACTCATCCTCACGATA-3′), and bisC (5′-GGCAAGCTTTTATGAGCTGGCCGGTGGTTCAA-3′) were used as primers. The two PCR products, bis1N/bisC and bis2N/bisC, respectively, were inserted into the NcoI and HindIII restriction sites of plasmid pBAD24 (11), yielding pBis1 and pBis2, respectively. Two additional oligonucleotides, bis2N′ (5′-CTGATAGAATTCCATATGGCCAACTCATCCTCACGATA-3′) and bisC′ (5′-GTGCTCGAGTGAGCTGGCCGGTGGTTCAA-3′) were used for cloning bisC(ORF2). The resulting PCR product was inserted into NdeI- and XhoI-restricted plasmid pET21a+ (Novagen), yielding pJBis.

Purification of BisC.

E. coli strain HMS174(DE3)/pJBis was grown at 37°C in LB medium. At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, 0.1 mM IPTG was added and growth was carried on for 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM sodium molybdate, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Resuspended cells were broken by a single passage through an ice-chilled French pressure cell at 0.8 tons. The resulting crude extract was centrifuged twice at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was applied to a 1-ml Hi-trap column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) loaded with nickel and equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol). Proteins were eluted with a 30-ml gradient running from 0.05 to 1 M imidazole. Fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After elution, the BisC-containing fractions were pooled, and the solution was concentrated by ultrafiltration on Amicon ultra (Millipore) (2,500 × g, 4°C). Purified proteins were subjected to SDS-10% PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford technique.

Purification of MsrA, MsrB, and MoeB proteins.

The purification protocols for MsrA and MsrB (10) and MoeB (L. Aussel and F. Barras, unpublished data) have been described.

In vitro oxidation and reparation of MoeB.

MoeB was treated with 50 mM H2O2 for 4 h at 25°C (14). The H2O2 was removed by gel filtration through G25 Sephadex, and oxidized MoeB was then repaired either by BisC (20 nM) or by a mixture of MsrA and MsrB (1 μM) in the presence of 15 mM dithiothreitol for 90 min at 37°C.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of MoeB.

Protein bands corresponding to the different preparations of MoeB were excised from the gel, destained, and treated with a solution of trypsin at 10 ng/μl (Promega). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 6 h, desalted, and eluted with 70% acetonitrile in water with 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid. Isotope 12C masses were determined in the positive ion reflector mode with a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF)-mass spectrometer Voyager DE-RP (Applied Biosystems) and internal calibration.

Methionine sulfoxide reductase activity assay.

Methionine sulfoxide reductase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 37°C by following the oxidation of reduced benzyl viologen at 600 nm coupled to the reduction of MetSO. MetSO activity was assayed under anaerobic conditions in a 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing benzyl viologen (357 μg/ml) and sodium dithionite. BisC enzyme was used at a final concentration of 9 nM. All the components were mixed before adding the substrate, Met-S-SO (2.8 mM) or Met-R-SO (2.4 mM). The amount of benzyl viologen oxidized was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm. The rate of benzyl viologen oxidation was linear with respect to enzyme concentration.

MetSO assimilation.

Cultures of E. coli were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium. Cells were then pelleted, washed, and diluted in fresh M9 medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05. Methionine and oxidized derivatives (Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO) were added at different concentrations (5, 10, and 20 μg/ml). The optical density at 600 nm was recorded after 24 h.

RESULTS

Genetic evidence for the existence of additional methionine sulfoxide reductases.

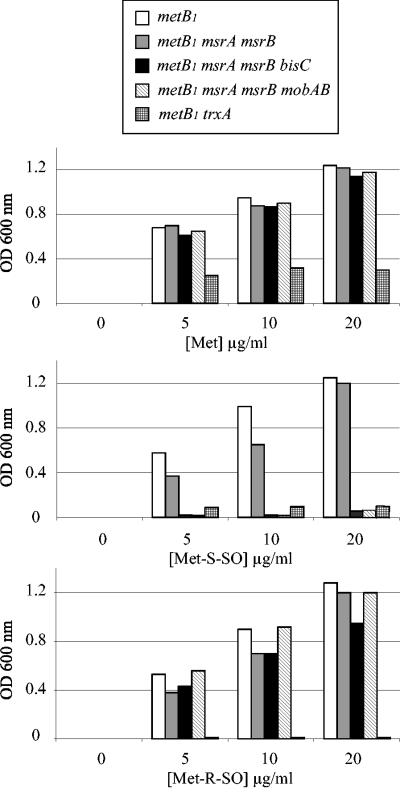

A metB1 auxotroph mutant, LCB303, was shown to be able to use either the Met-S-SO or Met-R-SO stereoisomer for growth (Fig. 1). An LCB303 derivative containing both msrA and msrB mutations was constructed by P1 transduction, yielding strain BE54. Growth of the BE54 strain was tested with different concentrations of the two MetSO enantiomers. No difference in growth was seen between strains LCB303 and BE54 (Fig. 1). This result indicated that additional methionine sulfoxide reductase activities were present in E. coli.

FIG. 1.

Assimilation of MetSO enantiomers by E. coli mutants. Strains were grown overnight in LB, spun down, washed, and used for inoculating M9-based minimal medium containing glucose and increasing concentrations of Met (top panel), Met-S-SO (middle panel), or Met-R-SO (lower panel). The optical density at 600 nm was recorded after 24 h of growth at 37°C. The strains analyzed were LCB303 (metB1), BE54 (metB1 msrA msrB), JB08 (metB1 msrA msrB bisC), BE72 (metB1 msrA msrB mobAB), and JB11 (metB1 trxA).

MetSO assimilation is trxA dependent.

Both MsrA and MsrB are known to be dependent upon a functional thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase pathway (9). Therefore, we asked whether the putative methionine sulfoxide reductase activities were dependent upon the Trx/TrxA pathway as well. An LCB303 trxA derivative was constructed and tested for growth in the presence of different concentrations of MetSO (Fig. 1). No growth was observed with either of the two MetSO enantiomers, even at high concentrations. These observations were consistent with previous published work (27) and indicated that, like MsrA and MsrB, the putative additional methionine sulfoxide reductases were TrxA dependent.

Evidence for the existence of a molybdenum-containing Met-S-SO-specific reductase.

In order to gain additional information about the putative methionine sulfoxide reductase activities, we tested the effect of preventing the biosynthesis of molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide, a molybdenum cofactor required for the activities of numerous reductases (12). The mobAB mutation was introduced into strain BE54, yielding derivative strain BE72. This strain was no longer able to utilize Met-S-SO for growth but retained the ability to use Met-R-SO (Fig. 1). This suggested that at least two additional methionine sulfoxide reductases occur in E. coli, one of them being a molybdenum-containing enzyme specific for Met-S-SO.

Evidence that BisC has a Met-S-SO reductase activity in vivo.

The biotin sulfoxide reductase BisC from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides was shown to exhibit a wide substrate specificity in vitro, including MetSO (20, 22). Moreover, early investigations in E. coli suggested that BisC depended upon a thioredoxin-like activity (5). This prompted us to investigate whether BisC allowed E. coli to utilize either Met-S-SO or Met-R-SO. To this end, a bisC mutation was constructed and transduced into strain BE54, yielding strain JB08. Growth studies revealed that strain JB08 was unable to use Met-S-SO but retained the ability to use Met-R-SO (Fig. 1).

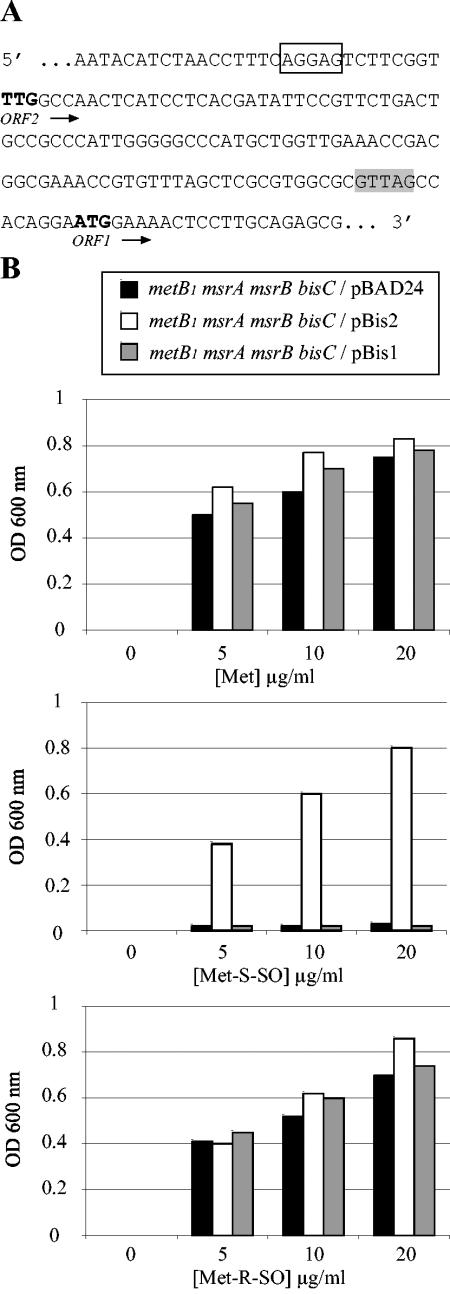

Complementation analysis was subsequently carried out. Unexpectedly, two predicted open reading frames (ORFs) on the bisC locus were found in the databases. One (hereafter referred to as ORF1) had an ATG initiation codon and was predicted to encode a 739-residue polypeptide. The other (referred to as ORF2) had a TTG initiation codon following a canonical Shine-Dalgarno sequence and was predicted to encode a 777-residue polypeptide (Fig. 2A). Strain JB08/pBis1 failed to use Met-S-SO, whereas strain JB08/pBis2 did (Fig. 2B). This indicated that ORF2 corresponded to BisC and, by inference, that the N-terminal 39 residues are essential for activity.

FIG. 2.

Complementation of the bisC mutation. (A) The sequence upstream of the bisC gene is shown. Two putative Shine-Dalgarno sequences are indicated as empty and shaded boxes, respectively. Pu-tative TTG and ATG initiation codons are in bold. bisC(ORF1) starts at the ATG codon, and bisC(ORF2) starts at the TTG codon. (B) Growth experiments were carried out as described for panel A except that glycerol was used as a carbon source and arabinose was present to induce expression of plasmid-borne genes. The strains analyzed were JB08 (metB1 msrA msrB bisC/pBAD24), JB308 (metB1 msrA msrB bisC/pBis2), and JB309 (metB1 msrA msrB bisC/pBis1).

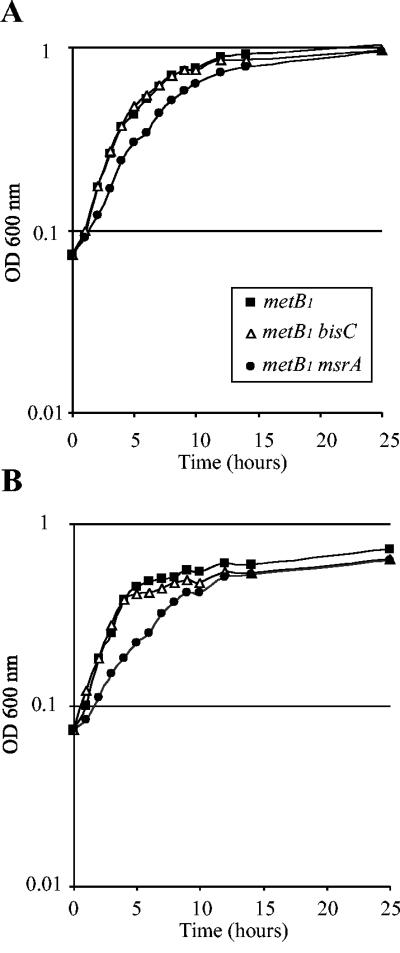

In order to evaluate the ability of BisC to act as a MetSO reductase in vivo, we compared the growth rate of a metB1 msrA mutant strain, JB02, with that of a metB1 bisC mutant strain, JB09. For both Met-S-SO concentrations, the msrA mutant strain grew slightly more slowly than the bisC mutant strain (Fig. 3A and B). These results showed that BisC was efficient enough in vivo to allow assimilation and reduction of Met-S-SO, albeit with a reduced efficiency compared with MsrA (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

BisC acts as a Met-S-SO reductase in vivo. Strains were grown overnight in M9-based medium with glucose and Met-S-SO, diluted to an A600 of 0.07, and used to inoculate the same medium containing either 20 μg (A) or 5 μg (B) of Met-S-SO per ml. A600 values were recorded every hour. The strains analyzed were LCB303 (▴), JB02 (•), and JB09 (▵).

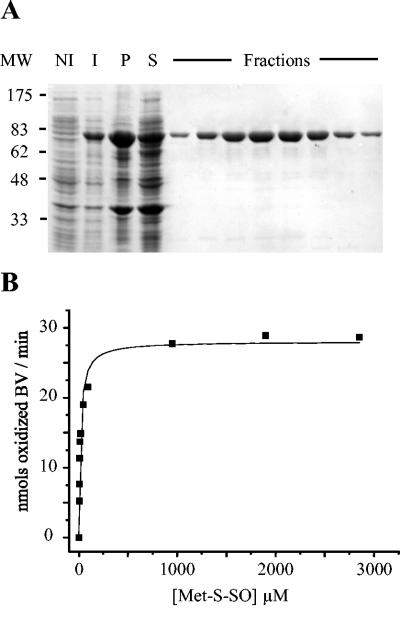

Biochemical characterization of BisC on free Met-S-SO.

BisC was purified in order to analyze its Met-S-SO reductase activity. The bisC DNA sequence was inserted into the pET21a+ vector so that the encoded enzyme had a polyhistidine tag at its C terminus (see Materials and Methods). The BisC-His6 protein was purified with a nickel-loaded Hi-Trap column, and the purification was followed by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel (Fig. 4A). The migration of BisC on the gel agrees with its molecular mass (85.85 kDa), and several fractions were >96% pure as estimated by SDS-PAGE. After ultrafiltration, an enzyme concentration of 6.5 μM was obtained. We undertook steady-state kinetic analysis of BisC with benzyl viologen as an artificial electron donor. In these conditions, BisC exhibited reductase activity when Met-S-SO was used as a substrate (Fig. 4B), whereas no activity was observed with Met-R-SO (data not shown). The Km value was 17 μM, and the turnover number was 3.2 min−1.

FIG. 4.

Biochemical characterization of E. coli BisC. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of samples taken through the different steps of the purification protocol. MW, molecular size markers; NI, cell extracts prior to IPTG induction; I, cell extracts after 2 h of IPTG induction; P, insoluble material from French press-treated cells; S, soluble material from French press-treated cells. the lanes labeled Fractions contained different samples eluted from the Hi-trap column (see Materials and Methods). The BisC protein-containing band runs with an apparent molecular mass of 85 kDa. (B) Kinetic analysis of BisC activity, using Met-S-SO as a substrate. Enzymatic activity tests were run under anaerobiosis in the presence of excess dithionite, reduced benzyl viologen (BV), BisC (9 nM), and increasing concentrations of Met-S-SO, 4.75 μM, 6.3 μM, 9.5 μM, 11.9 μM, 19 μM, 47.5 μM, 95 μM, 950 μM, 1.9 mM, and 2.8 mM.

Mass spectrometry analysis of the BisC activity on oxidized protein.

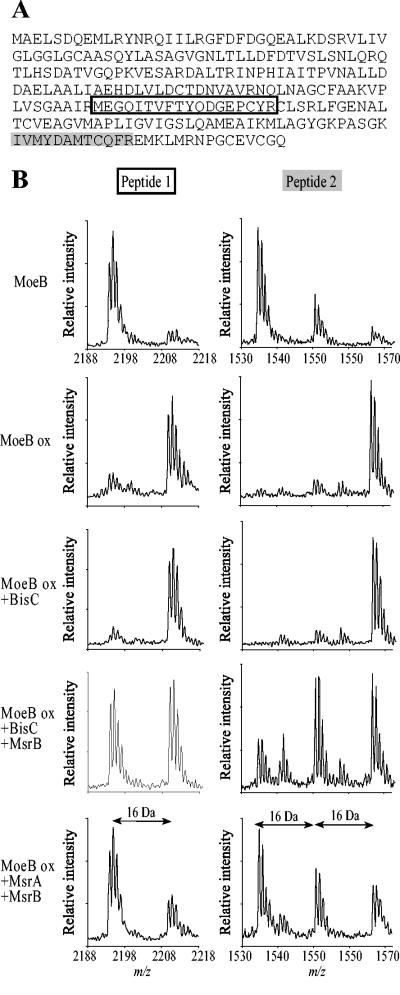

We then asked whether BisC could repair protein-bound MetSO residues. For this, we chose MoeB protein. Recently, we showed that oxidized MoeB was a substrate for MsrA and MsrB (L. Aussel and F. Barras, unpublished data). Purified MoeB protein was oxidized with H2O2 and subjected to repair by BisC. Samples containing native MoeB, oxidized MoeB, or BisC-repaired oxidized MoeB were run on SDS-PAGE. Bands of each sample were cut out of the gel and treated with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF/mass spectrometry. The spectra obtained were scanned for Met-containing peptides. Trypsin hydrolysis was predicted to produce four peptides containing at least one Met residue.

Based upon their predicted mass values, two peptides could be identified within the spectra of tryptic digests of native, oxidized, and repaired MoeB. These peptides are shown in the primary sequences presented in Fig. 5A. When the spectrum of oxidized MoeB was determined, the masses of peptides 1 and 2 were found to increase by 16 or 32 Da, corresponding to a gain of one or two oxygen atoms, respectively (Fig. 5B). The spectrum of oxidized MoeB treated with BisC proved to be the same as that of untreated oxidized MoeB (Fig. 5B). When MsrB was added to BisC, about 50% of MetSO was reduced to Met due to the stereospecificity of MsrB for Met-R-SO. This result also underlined the racemic distribution of Met-R-SO and Met-S-SO resulting from the oxidation of peptide-bound methionine in vitro, as shown by the equal intensity of the two peaks from peptide 1 (Fig. 5B). As a control, oxidized MoeB was treated with both MsrA and MsrB, and analysis of the corresponding spectra showed that both oxidized peptides 1 and 2 were reduced, as expected (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results showed that BisC is unable to reduce oxidized protein-bound methionine residues.

FIG. 5.

BisC is unable to reduce protein-bound methionyl residues. (A) The primary sequence of MoeB is shown. Peptides whose oxidation status was followed during the experiment are indicated in boxes. (B) MALDI-TOF spectra of peptides generated by trypsin treatment of native MoeB, oxidized MoeB (MoeB ox), and oxidized MoeB repaired with BisC, BisC and MsrB, or MsrA and MsrB.

DISCUSSION

Methionine is essential for cellular metabolism both as a residue for protein synthesis and as a source of nutrients, including sulfur. However, due to its high sensitivity to oxidation, Met can become limiting, and cells have developed enzymatic processes that revert MetSO back to Met. To date, two enzymes present in most organisms are known to catalyze such a reversible process, MsrA and MsrB, which reduce Met-S-SO and Met-R-SO stereoisomers, respectively. However, the finding that an E. coli strain lacking both the msrA and msrB genes retained the ability to use a mixture of the two MetSO stereoisomers indicated that other MetSO reductases must be present. The purpose of the present work was to gain information about the identity of these putative new methionine sulfoxide reductases.

Preliminary investigation revealed that the protein allowing the metB1 msrA msrB mutant to assimilate Met-S-SO was dependent upon functional molybdenum biosynthesis machinery. E. coli synthesizes several molybdoreductases which can act on MetSO. These enzymes are members of the so-called dimethyl sulfoxide reductase family and include the dimethyl sulfoxide/TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) reductase DmsA (25) and the TMAO reductase TorZ (8). However, DmsA is synthesized under anaerobiosis, and TorZ is periplasmic. Thus, neither of these enzymes was likely to act on MetSO in the cytoplasm under aerobiosis as MsrA and MsrB do. On the other hand, E. coli synthesizes a biotin sulfoxide reductase referred to as BisC, the Rhodobacter sphaeroides orthologue of which was shown to be able to act on MetSO (19-21, 29). Here, we report that the E. coli metB1 msrA msrB bisC mutant was unable to grow in the presence of Met-S-SO. This was an important observation because (i) the in vivo role of the bisC gene was thought to be dedicated to biotin sulfoxide recycling (4, 5) and (ii) the Km of R. sphaeroides BisC for MetSO was far higher than that for biotin sulfoxide (20, 21), the natural substrate, casting some doubt on the possibility that BisC could actually act as a methionine sulfoxide reductase in vivo.

Specificity for the Met-S-SO stereoisomer was further established by biochemical analysis. Importantly, the Km of the E. coli BisC enzyme (17 μM) was much smaller than that of the R. sphaeroides enzyme (800 μM). Moreover, the catalytic efficiency of BisC (0.18 min−1 μM−1) proved to be close to that of MsrA (0.12 min−1μM−1) (10). Moreover, growth analysis of a strain producing BisC as the sole Met-S-SO reductase exhibited growth in the presence of Met-S-SO as a Met source. Thus, both biochemical and genetic analyses established BisC as a bona fide methionine sulfoxide reductase fulfilling a physiologically significant role in Met-S-SO assimilation in E. coli. Our results provide a new role for BisC, which has already been shown to be essential for growth on a d-biotin-d-sulfoxide source (4).

BLAST analyses of the BisC proteins from E. coli (777 residues) and R. sphaeroides (744 residues) were performed (data not shown). Interestingly, 28 out of 33 missing residues from R. sphaeroides are concentrated in the N-terminal part of the protein. In the present study, we identified the 39 N-terminal residues as essential for BisC biological activity in vivo (Fig. 2B) and in vitro (data not shown). This extra domain, present in E. coli, is conserved in other bacterial genera (Mycobaterium, Bordetella, Helicobacter, and Salmonella). It might be involved in an electron transfer mechanism different from that of R. sphaeroides, where NADPH can be used directly as a reducing agent (20).

It has been well established for other molybdenum-containing reductases that the molybdenum cofactor of BisC allows electron transfer from an electron donor to the substrate. The identity of the physiological electron donor remains unknown. In this context, our observation that a trxA mutation prevented use of Met-S-SO is puzzling because the Trx/TrxA pathway is not known to act as an electron donor for molybdoenzymes. Moreover, we failed to observe BisC activity in vitro in the presence of NADPH and the Trx/TrxA couple (data not shown). Therefore, as a working hypothesis, we propose that an intermediate cofactor is required to transfer electrons from the Trx/TrxA couple to BisC. Mutagenesis experiments are under way to identify such a component.

To date, all methionine sulfoxide reductases identified are able to act on both free and peptide-bound MetSO residues. Hence, we investigated whether BisC could repair protein-bound MetSO. Mass spectrometry analysis with MoeB as a model demonstrated that, surprisingly, BisC was unable to act upon protein-bound MetSO. The difference in the abilities of Msr enzymes and BisC to act upon protein-bound MetSO may be related to differences in the location and geometry of catalytic sites. Indeed, the catalytic sites of MsrA and MsrB form an open site at the surface of the molecule, while that of BisC is thought to be buried inside the protein (15, 23, 30).

In conclusion, we identified a new class of enzyme with substrate selectivity for free versus protein-bound MetSO. Moreover, BisC showed a stereospecificity for Met-S-SO versus Met-R-SO, raising the existence of one or many extra enzymes carrying an Msr activity specific for the R stereoisomer and consistent with the identification of a putative new member of the Msr family in E. coli extracts that reduce free Met-R-SO to Met (6). A better knowledge of the enzymes involved in the reduction of MetSO, both free and in peptide linkage, could be of great value in understanding this essential mechanism allowing cells to protect themselves against oxidative damage.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the FB group for fruitful discussion, to Axel Magalon and Chantal Iobbi-Nivol (LCB Marseille) for introducing us to the world of molybdoenzymes, and to G. Branlant (Université de Nancy) for insightful discussion. Purified MetSO stereoisomers were a kind gift from Alexandre Olry from the G. Branlant laboratory. Thanks are due to E. Bouveret, S. Gon, and J. Beckwith for strains and advice and D. Moinier for technical assistance in MALDI-TOF analysis.

The research was supported by grants from the CNRS, the Proteome program, and the Université de la Méditerranée. B.E. was supported by a fellowship from the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brot, N., and H. Weissbach. 1981. Chemistry and biology of E. coli ribosomal protein L12. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 36:47-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, D. A., F. M. Newcomb, J. Moskovitz, P. T. Wingfield, S. J. Stahl, J. Kaufman, H. M. Fales, R. L. Levine, and R. Yarchoan. 2000. HIV-2 protease is inactivated after oxidation at the dimer interface and activity can be partly restored with methionine sulphoxide reductase. Biochem. J. 346:305-311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.del Campillo-Campbell, A., and A. Campbell. 1982. Molybdenum cofactor requirement for biotin sulfoxide reduction in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 149:469-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.del Campillo-Campbell, A., D. Dykhuizen, and P. P. Cleary. 1979. Enzymic reduction of d-biotin d-sulfoxide to d-biotin. Methods Enzymol. 62:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etienne, F., D. Spector, N. Brot, and H. Weissbach. 2003. A methionine sulfoxide reductase in Escherichia coli that reduces the R enantiomer of methionine sulfoxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300:378-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezraty, B., R. Grimaud, M. E. Hassouni, D. Moinier, and F. Barras. 2004. Methionine sulfoxide reductases protect Ffh from oxidative damages in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 23:1868-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gon, S., J. C. Patte, V. Mejean, and C. Iobbi-Nivol. 2000. The torYZ (yecK bisZ) operon encodes a third respiratory trimethylamine N-oxide reductase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:5779-5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez Porque, P., A. Baldesten, and P. Reichard. 1970. The involvement of the thioredoxin system in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide and sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 245:2371-2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimaud, R., B. Ezraty, J. K. Mitchell, D. Lafitte, C. Briand, P. J. Derrick, and F. Barras. 2001. Repair of oxidized proteins. Identification of a new methionine sulfoxide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48915-48920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisker, C., H. Schindelin, and D. C. Rees. 1997. Molybdenum-cofactor-containing enzymes: structure and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:233-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar, R. A., A. Koc, R. L. Cerny, and V. N. Gladyshev. 2002. Reaction mechanism, evolutionary analysis, and role of zinc in Drosophila methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37527-37535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine, R. L., L. Mosoni, B. S. Berlett, and E. R. Stadtman. 1996. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15036-15040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowther, W. T., H. Weissbach, F. Etienne, N. Brot, and B. W. Matthews. 2002. The mirrored methionine sulfoxide reductases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilB. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:348-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michaelis, M. L., D. J. Bigelow, C. Schoneich, T. D. Williams, L. Ramonda, D. Yin, A. F. Huhmer, Y. Yao, J. Gao, and T. C. Squier. 1996. Decreased plasma membrane calcium transport activity in aging brain. Life Sci. 59:405-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olry, A., S. Boschi-Muller, M. Marraud, S. Sanglier-Cianferani, A. Van Dorsselear, and G. Branlant. 2002. Characterization of the methionine sulfoxide reductase activities of PILB, a probable virulence factor from Neisseria meningitidis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12016-12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer, T., C. L. Santini, C. Iobbi-Nivol, D. J. Eaves, D. H. Boxer, and G. Giordano. 1996. Involvement of the narJ and mob gene products in distinct steps in the biosynthesis of the molybdoenzyme nitrate reductase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 20:875-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierson, D. E., and A. Campbell. 1990. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of bisC, the structural gene for biotin sulfoxide reductase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:2194-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock, V. V., and M. J. Barber. 1997. Biotin sulfoxide reductase. Heterologous expression and characterization of a functional molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide-containing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3355-3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollock, V. V., and M. J. Barber. 2001. Kinetic and mechanistic properties of biotin sulfoxide reductase. Biochemistry 40:1430-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollock, V. V., and M. J. Barber. 1995. Molecular cloning and expression of biotin sulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides forma sp. denitrificans. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 318:322-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romao, M. J., J. Knablein, R. Huber, and J. J. Moura. 1997. Structure and function of molybdopterin containing enzymes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 68:121-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharov, V. S., D. A. Ferrington, T. C. Squier, and C. Schoneich. 1999. Diastereoselective reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide by methionine sulfoxide reductase. FEBS Lett. 455:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simala-Grant, J. L., and J. H. Weiner. 1996. Kinetic analysis and substrate specificity of Escherichia coli dimethyl sulfoxide reductase. Microbiology 142:3231-3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadtman, E. R. 1992. Protein oxidation and aging. Science 257:1220-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart, E. J., F. Aslund, and J. Beckwith. 1998. Disulfide bond formation in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm: an in vivo role reversal for the thioredoxins. EMBO J. 17:5543-5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, H., J. Gao, D. A. Ferrington, H. Biesiada, T. D. Williams, and T. C. Squier. 1999. Repair of oxidized calmodulin by methionine sulfoxide reductase restores ability to activate the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase. Biochemistry 38:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temple, C. A., G. N. George, J. C. Hilton, M. J. George, R. C. Prince, M. J. Barber, and K. V. Rajagopalan. 2000. Structure of the molybdenum site of Rhodobacter sphaeroides biotin sulfoxide reductase. Biochemistry 39:4046-4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tete-Favier, F., D. Cobessi, S. Boschi-Muller, S. Azza, G. Branlant, and A. Aubry. 2000. Crystal structure of the Escherichia coli peptide methionine sulphoxide reductase at 1.9 A resolution. Structure Fold. Des. 8:1167-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissbach, H., F. Etienne, T. Hoshi, S. H. Heinemann, W. T. Lowther, B. Matthews, G. St John, C. Nathan, and N. Brot. 2002. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase: structure, mechanism of action, and biological function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397:172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]