Resistance to glycopeptides was not reported for approximately 30 years after the introduction of vancomycin into clinical practice, due partly to limited use of the antibiotic until the mid-1970s. The lengthy period was also due to the difficulties experienced by bacteria in developing mechanisms of resistance to an antibiotic which binds to an essential substrate in a biosynthetic pathway rather than to a protein or nucleic acid. Following publication in 1988 of reports of the first vancomycin-resistant enterococci (25, 39), it was predicted that resistance might arise by one of four possible routes, including inactivation of the antibiotic (not yet observed), sequestration of the antibiotic in the outer cell wall layers by specific and nonspecific binding (the probable mechanism by which low-level resistance is achieved in staphylococci), by an increased production of those intermediates to which vancomycin binds, or by a change in the target site (33). It was later recognized that the last mechanism would involve not only a new pathway to achieve a change of target but also elimination of at least part of the normal susceptible pathway (36).

In spite of the complexity of such a mechanism, the enterococci have developed two similar strategies involving a change of target. High-level resistance in Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis is characteristic of the VanA, VanB, and VanD types, in which the acyl-d-Ala-d-Ala terminus of peptidoglycan precursors to which glycopeptides bind has been replaced by acyl-d-Ala-d-lactate with the loss of a crucial hydrogen bond in the binding site. This results in a more-than-1,000-fold lowering of the affinity of vancomycin for its target. The substitution is achieved by the activity of two enzymes, a d-lactate dehydrogenase and a ligase with specificity directed towards synthesis of d-Ala-d-lactate(d-Lac) rather than d-Ala-d-Ala (16). An essential aspect of the resistance mechanism is the elimination of d-Ala-d-Ala by a dd-dipeptidase and/or of precursors containing this moiety by a dd-carboxypeptidase that removes the C-terminal d-Ala (8, 36). This mechanism has been extensively reviewed (7, 12, 22, 34, 40, 41).

The second mechanism, which confers a low level of resistance to vancomycin only, involves replacement of d-Ala-d-Ala by a different dipeptide, d-Ala-d-Ser, rather than by the depsipeptide d-Ala-d-Lac (14, 37). This mechanism is utilized by the intrinsically glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum, Enterococcus casseliflavus, and Enterococcus flavescens (VanC type) and is present in the VanE and VanG types in which E. faecalis has acquired the genes encoding vancomycin resistance. Some of the enzymes implicated in this second resistance mechanism are different from those involved in high-level resistance, indicating a second route by which resistance has evolved. The basis of resistance results from the sixfold-lower affinity of vancomycin for acyl-d-Ala-d-Ser than for acyl-d-Ala-d-Ala (13) because of the increased bulk of the hydroxymethyl group of serine relative to the methyl group of alanine.

VanC-TYPE RESISTANCE

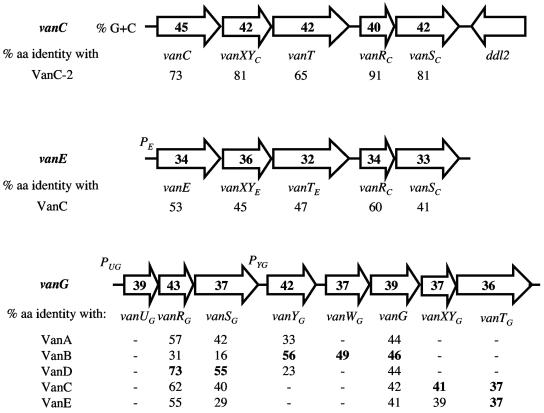

Low-level intrinsic resistance to vancomycin (MIC, 2 to 32 mg/liter) and susceptibility to teicoplanin (MIC, 0.5 to 1.0 mg/liter) was first determined in E. gallinarum BM4174, which expresses resistance constitutively (26); it was subsequently detected in E. casseliflavus (VanC-2 type) and E. flavescens (VanC-3 type) (29). Strains with this phenotype, both inducible and constitutive for resistance (38), are present in the gastrointestinal tract and are considered to be clinically significant in causing surgical infections. The vanC gene cluster, which is chromosomally located, encodes five proteins (Fig. 1) (3). A putative ligase gene, distinct from that encoding the host d-Ala:d-Ala ligase, was identified by using degenerate oligodeoxyribonucleotides corresponding to conserved amino acid motifs in Escherichia coli d-Ala:d-Ala ligases as primers to synthesize a probe that hybridized to a PstI fragment of E. gallinarum DNA, and the gene (vanC) was subsequently sequenced (18); the derived protein of 343 amino acids had substantial identity with VanA and d-Ala:d-Ala ligases. Insertional inactivation of vanC resulted in loss of vancomycin resistance of the host strain and loss of the ability to synthesize peptidoglycan precursors ending in acyl-d-Ala-d-Ser (37). The corresponding purified protein (VanC-2) from E. casseliflavus (73% identical to VanC) had d-Ala:d-Ser ligase activity, and studies of its specificity by measurement of the kcat/Km2 ratios indicated a 400-fold selective advantage for the incorporation of d-Ser over d-Ala in the C-terminal position (30). Mutation of two residues, F250Y and R322M, resulted in a 6,000-fold switch of substrate specificity towards the production of d-Ala-d-Ala, mainly due to loss of d-Ala-d-Ser synthetic activity (24). Sequencing of the DNA upstream from the vanC ligase gene revealed no regulatory or sensor genes as found in VanA, VanB, and VanD types or of any other gene that might be involved in vancomycin resistance (3).

FIG. 1.

Organization of the VanC, VanE, and VanG glycopeptide resistance gene clusters and comparison of the degrees of amino acid (aa) identity of the corresponding proteins. VanC-2 is E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788. Arrows represent coding sequences and indicate the direction of transcription. The numbers in boldface indicate the highest percentage of identity with VanG-type proteins.

Destruction of susceptible precursors.

Two open reading frames were located immediately downstream from vanC, both of which overlapped the previous gene by 1 bp (3). The gene adjacent to vanC encoded a cytoplasmic protein of 190 amino acids which hydrolyzed d-Ala-d-Ala (dd-dipeptidase activity) and removed d-Ala from UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[d-Ala] (dd-carboxypeptidase activity) (35). This single protein (VanXYC) therefore replaced the cytoplasmic VanX-type dd-dipeptidase and the membrane-bound VanY-type dd-carboxypeptidase (both are present in VanA and VanB strains). In VanA-type strains in which the vancomycin resistance genes are plasmid-borne, the activity of VanX is sufficient to virtually eliminate d-Ala-d-Ala and VanY is not essential for resistance (8, 9, 36). However, analysis of peptidoglycan precursors in E. gallinarum BM4174 (75% tetrapeptide, 25% pentapeptide[d-Ser] [37]) indicates that d-Ala-d-Ala is not eliminated by VanXYC activity and that the cytoplasmic dd-carboxypeptidase activity is essential to convert residual pentapeptide[d-Ala] into tetrapeptide so that the lipid intermediates into which these precursors are subsequently incorporated cannot bind vancomycin (34). The structure of the peptidoglycan of E. gallinarum contains pentapeptides terminating in d-Ser but not d-Ala, confirming the efficiency of VanXYC in removing precursors ending in acyl-d-Ala-d-Ala (23).

In VanA-type strains the specificity of VanX is directed towards hydrolysis of dd-dipeptides; there is low activity against the depsipeptide d-Ala-d-Lac and no activity against N- or C-terminally substituted d-Ala-d-Ala. d-Ala-d-Ser is also hydrolyzed, although at a lower rate than d-Ala-d-Ala (36, 42). Although the active site of VanXYC is similar to those of VanX- and VanY-type enzymes (see below), the substrate specificity in relation to its dd-dipeptidase activity is different. The kcat/Km ratio is ca. 25 to 30 times lower for d-Ala-d-Ser than for d-Ala-d-Ala (32). It has even stricter specificity as a dd-carboxypeptidase, having no activity against pentapeptide[d-Ser]. It does not have the specific binding sites for the N or C termini of d-Ala-d-Ala that are present in VanX- but not VanY-type enzymes, and it has a specific glutamine residue at position 67 that is essential for activity of a VanY- but not a VanX-type enzyme (35). The aspartic acid residue at position 59 that is vital in VanX (mutation to Ala or Ser results in an enormous decrease in the catalytic efficiency [27]) is unimportant in VanXYC, where mutation to Ala or Ser hardly affects the kcat/Km ratio (32). Other aspects of the amino acid sequence in close proximity to the active-site regions also suggest that VanXYC has evolved from a VanY-type enzyme rather than from a strict dd-dipeptidase.

Production of d-serine.

The availability of d-Ser results from the activity of VanT, which is a serine racemase (4). Amino acid racemases are normally cytoplasmic and have a conserved pyridoxal phosphate binding site close to the N terminus. VanT is atypical in that it is a membrane-bound protein of 698 amino acids, approximately twice the size of other bacterial amino acid racemases, with 10 predicted transmembrane helices in the N-terminal domain of the protein followed by a cytoplasmic domain containing a predicted pyridoxal binding site (4). Modeling of this C-terminal domain indicates a close relationship to alanine racemases. VanT also possesses alanine racemase activity as demonstrated by the ability of a plasmid carrying vanT to complement E. coli TKL-10 (a strain with a temperature-sensitive alanine racemase) at the nonpermissive temperature (6). The 3′ end of the gene has been cloned and purified as a His-tagged protein which possesses both serine and alanine racemase activities, the latter being 18% of that of serine racemase (6). Modeling of the C-terminal domain by using three-dimensional data obtained with the alanine racemase of Bacillus stearothermophilus indicates considerable homology between the two enzymes. Virtually all critical amino acids in the active site of the alanine racemase of B. stearothermophilus are conserved in VanT, indicating that the C-terminal domain of VanT probably has a three-dimensional structure similar to that of alanine racemase and that the protein exists as a dimer (4). An asparagine residue (N683) close to the C terminus has been postulated to play an important role in substrate specificity: all the alanine racemases have a tyrosine residue in the equivalent position, and mutation of this residue to asparagine results in a 62-fold increase in serine racemase activity with virtually no change in alanine racemase activity (31). This increase in catalytic turnover of l-Ser could be an important step in the evolution of VanT and would presumably have been followed by a decrease in the Km for l-Ser (31).

It is probable that the N-terminal domain functions as an l-Ser transporter. The rate of l-Ser transport in E. gallinarum BM4175 (lacking serine racemase activity) is restored to the ca. twofold-higher level in E. gallinarum BM4174 by the insertion of the three genes vanC-vanXYC-vanT (5). l-Ser is involved in many important metabolic pathways, including protein synthesis and one-carbon metabolism, and it is possible that VanT ensures that sufficient l-Ser from the external medium is presented directly to the active site of the racemase for peptidoglycan synthesis to proceed at a nonlimiting rate in the presence of vancomycin (5).

Cloning of the three genes vanC-vanXYC-vanT, but not of any two of them, in E. faecalis JH2-2 confers low-level resistance to vancomycin and results in a change of the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway to that present in E. gallinarum, thus confirming that all three genes are essential for resistance (3).

Regulation.

The genes encoding two-component sensor (VanS) and regulatory (VanR) systems are located downstream from the three genes essential for resistance (3). The genes overlap by 8 bp, and VanS is initiated by a leucine residue; both of these features are characteristic of the corresponding two-component systems in the VanA and VanB types (10, 11). The highest percent identities of VanRC and VanSC are with VanR and VanS (50% and 40, respectively), and VanRC contains the same number of amino acids as VanR, suggesting that the same type of regulatory system is present in the different Van types (3). It seems possible that the VanC phenotype has evolved by the fusion of a regulatory system (from a VanA-, VanB-, or VanD-type strain) with the three genes essential for resistance that have been derived from other sources. The basis of the constitutive phenotype in several strains of E. gallinarum has not yet been elucidated, although by analogy with several constitutively resistant strains of the VanB type, mutations in the sensor are most likely to prove significant.

Surprisingly, in E. gallinarum BM4174 a third ligase gene is present immediately downstream from the regulatory genes but reads in the opposite direction. The gene product has been purified as a His-tagged protein and has been shown to possess d-Ala:d-Ala ligase activity with no d-Ala:d-Ser ligase activity (2). Insertion of the gene into a vancomycin-dependent strain of E. faecalis with a defect in the gene encoding d-Ala:d-Ala ligase restored vancomycin independence (growth in the absence of vancomycin), and wall precursors terminating in d-Ala-d-Ala were present under such conditions (2). Therefore, the enzyme is active both in vitro and in vivo, but its function in E. gallinarum is unclear unless it is to act as a reserve enzyme if the normal host ligase is inactive.

The extensive differences between two of the proteins (dd-peptidase and serine racemase) encoded by the vanC gene cluster and those encoded by the vanA, -B, and -D resistance operons suggest that these two types of resistance mechanisms evolved separately.

E. casseliflavus and E. flavescens.

E. casseliflavus possesses the same organization of the vancomycin resistance genes as E. gallinarum, and the corresponding genes have a high degree of identity (65 to 91% [Fig. 1]) (19). As with E. gallinarum, the dd-carboxypeptidase is highly active as judged by direct assays and by the presence of a high percentage of tetrapeptide in the cytoplasm compared with pentapeptide[d-Ser]. Serine racemase activity is low in comparison with that of alanine racemase, and a shortage of d-serine is probably responsible for the low rate of induction of resistance: it takes 3 to 4 h in the presence of vancomycin before growth resumes and precursors terminating in d-Ala-d-Ser are detected in the cytoplasm (19). Insertion of additional copies of VanTC-2 on a plasmid or the addition of 50 mM d-Ser to the growth medium shortens the latent period before growth resumes in the presence of vancomycin (19). The glycopeptide resistance genes of E. flavescens are virtually identical to those of E. casseliflavus (97 to 100% identical), and the lack of nucleotide divergence between the sequences casts doubt on the validity of these enterococci being classed as distinct species (20).

VanE-TYPE RESISTANCE

Synthesis of peptidoglycan precursors ending in d-Ala-d-Ser has been detected in two other vancomycin-resistant types of E. faecalis designated VanE (21) and VanG (17, 28). In both instances, resistance is acquired and low level, and the genes conferring resistance are chromosomal.

VanE-type resistance, which is not transferable by conjugation, is virtually identical to that in VanC strains apart from the different relative activity of enzymes (21). Five genes are involved: the three essential genes encoding a VanE ligase, VanXYE dd-dipeptidase/dd-carboxypeptidase, and VanTE serine racemase, with genes encoding a two-component regulatory system downstream from the essential genes (1, 15). The percent identities of the five deduced products with the corresponding proteins in E. gallinarum vary from 41 to 60% (Fig. 1). The activity of the VanXYE dd-peptidase is much lower than that of VanXYC, whereas the activity of the serine racemase is at least 10-fold higher than that of VanT (21). This results in a pentapeptide[d-Ser]/tetrapeptide ratio of ca. 8 in E. faecalis BM4405, compared with 0.33 in E. gallinarum BM4174 or E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788. Although glycopeptide resistance in the prototype strain E. faecalis BM4405 is inducible, a stop codon at position 78 of VanSE would have resulted in premature termination of the protein and an inactive sensor (1). Cross talk with another two-component regulatory system may have resulted in regulation of the operon. The five genes are transcribed into a single mRNA of approximately 5,800 bases as determined by Northern analysis and confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (1). Primer extension experiments also indicate the presence of a single transcription start upstream from vanE (1). This is different from the situation in VanA- and VanB-type strains, in which two promoters are present, one upstream from the regulatory genes and the other between the regulatory genes and those encoding resistance (12). A number of other VanE-type strains have been investigated.

It is possible that VanE-type resistance was acquired from a VanC-type strain, but if so it is unlikely to have occurred recently in view of the percent identities of the five proteins with those from E. gallinarum (41 to 60%) and the much lower G/C ratios in all five genes (32 to 36%, compared with 40 to 45% in E. gallinarum [Fig. 1]). An open reading frame downstream from the vanE gene cluster in E. faecalis N00-410 has homology to some integrase genes, suggesting that it may have been involved in acquisition of the resistance gene cluster (15).

VanG-TYPE RESISTANCE

In common with VanC and VanE types, strains of E. faecalis of the VanG type synthesize peptidoglycan precursors terminating in d-Ala-d-Ser (17). In several respects VanG strains differ from VanC and VanE isolates. The vanG cluster is composed of eight genes (Fig. 1), which are likely to have been recruited from at least three van operons (17, 28). The two regulatory genes (vanRG and vanSG) encode proteins with 73 and 55% identity to VanRD and VanSD, respectively, and are upstream from the resistance genes (as in VanA-, VanB-, and VanD-type strains but unlike the organization in VanC- and VanE-type strains); they are preceded by a third gene (vanUG) not present in any other van operon, which encodes a protein of 75 amino acids with homology to transcriptional activators (17). This three-gene component of the operon encoding a putative regulatory system is cotranscribed constitutively from the PUG promoter, whereas transcription of the remaining genes of the operon is inducible and controlled by the PYG promoter located between vanSG and vanYG as in VanB strains (17). The remainder of the operon contains a mosaic of genes which appear to have been derived from VanB-type and VanC/E-type strains. The 5′ end encodes VanYG and VanWG (a protein whose function is unknown and which previously has been detected only in VanB-type strains), which have 56 and 49% identity, respectively, with VanYB and VanW (28). These genes are followed by vanG, vanXYG, and vanTG, which encode proteins involved in synthesis of d-Ala-d-Ser and potentially in the elimination of pentapeptide[d-Ala]. The assembly of such an array of genes from different sources represents an impressive achievement. Studies of the enzyme activities in vitro of strains induced to resistance indicate a relatively low membrane-bound serine racemase activity and barely detectable cytoplasmic dd-peptidase activity (17). Furthermore, the vanYG gene contains a frameshift mutation leading to premature termination of VanYG after amino acid 121 and a consequent absence of activity (17). Analysis of the peptidoglycan precursors is consistent with measurement of the enzyme activities: virtually no tetrapeptide was detected, and in cultures fully induced for resistance between 30 and 50% of the precursors were pentapeptide[d-Ala], with pentapeptide[d-Ser] accounting for 46 to 66%. Surprisingly, a vancomycin-inducible, membrane-bound dd-carboxypeptidase activity was detected in BM4518 and WCH9; presumably the active site of this protein is external to the cytoplasmic membrane, as d-Ala is not removed from cytoplasmic pentapeptide[d-Ala] (17). This leaves unanswered questions as to how VanG-type strains are as resistant to vancomycin as VanC- or VanE-type isolates, in which all the susceptible precursors have been eliminated. It would be interesting to examine the peptidoglycan structure of VanG strains to determine whether un-cross-linked peptide substituents consist of tetrapeptides or only pentapeptides and whether the pentapeptides have C-terminal d-Ala, d-Ser, or both. It is also surprising that in strain WCH9, uninduced to resistance, the percentage of pentapeptide[d-Ser] reached 30% of the total precursors in spite of the relatively low level of serine racemase activity (17). Transfer of VanG resistance to susceptible strains of E. faecalis results from the movement of large, ca. 240-kb, genetic elements from chromosome to chromosome (17).

SUMMARY

Although the MICs of vancomycin for VanC-, VanE-, and VanG-type strains are similar, the strategy of achieving resistance varies. VanC strains rely on an active cytoplasmic dd-carboxypeptidase to eliminate pentapeptide[d-Ala], VanE strains have a powerful serine racemase and presumably a very active d-Ala:d-Ser ligase to ensure that the bulk of cytoplasmic precursors produced are pentapeptide[d-Ser], whereas VanG strains have a weakly active VanTG serine racemase and an almost inactive VanXYG dd-peptidase. It is tempting to speculate that the vancomycin-inducible, membrane-bound dd-carboxypeptidase, which is unlikely to be encoded by VanYG (17), removes d-Ala from lipid intermediates containing acyl-d-Ala-d-Ala as they emerge through the membrane, thus ensuring that only intermediates containing acyl-d-Ala-d-Ser come into contact with vancomycin on the external face of the membrane of VanG strains.

Acknowledgments

P.E.R. thanks the Leverhulme Foundation for an emeritus fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abadía Patiño, L., P. Courvalin, and B. Périchon. 2002. vanE gene cluster of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. J. Bacteriol. 184:6457-6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambur, O. H., P. E. Reynolds, and C. A. Arias. 2002. d-Ala:d-Ala ligase gene flanking the vanC cluster: evidence for presence of three ligase genes in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:95-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias, C. A., P. Courvalin, and P. E. Reynolds. 2000. vanC cluster of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1660-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias, C. A., M. Martin-Martinez, T. L. Blundell, M. Arthur, P. Courvalin, and P. E. Reynolds. 1999. Characterization and modelling of VanT: a novel, membrane-bound, serine racemase from vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1653-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias, C. A., J. Peña, D. Panesso, and P. Reynolds. 2003. Role of the transmembrane domain of the VanT serine racemase in resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:557-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arias, C. A., J. Weisner, J. M. Blackburn, and P. E. Reynolds. 2000. Serine and alanine racemase activities of VanT: a protein necessary for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Microbiology 146:1727-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthur, M., and P. Courvalin. 1993. Genetics and mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1563-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arthur, M., F. Depardieu, H. A. Snaith, P. E. Reynolds, and P. Courvalin. 1994. Contribution of VanY d,d-carboxypeptidase to glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis by hydrolysis of peptidoglycan precursors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1899-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arthur, M., F. Depardieu, L. Cabanié, P. Reynolds, and P. Courvalin. 1998. Requirement of the VanY and VanX d,d-peptidases for glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Mol. Microbiol. 30:819-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur, M., C. Molinas, and P. Courvalin. 1992. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J. Bacteriol. 174:2582-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arthur, M., and R. Quintiliani, Jr. 2001. Regulation of VanA- and VanB-type glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:375-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arthur, M., P. E. Reynolds, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 4:401-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billot-Klein, D., D. Blanot, L. Gutmann, and J. van Heijenoort. 1994. Association constants for the binding of vancomycin and teicoplanin to N-acetyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine and N-acetyl-d-alanyl-d-serine. Biochem. J. 304:1021-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billot-Klein, D., L. Gutmann, S. Sable, E. Guittet, and J. van Heijenoort. 1994. Modification of peptidoglycan precursors is a common feature of the low-level vancomycin-resistant VanB-type Enterococcus D366 and of the naturally glycopeptide-resistant species Lactobacillus casei, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and Enterococcus gallinarum. J. Bacteriol. 176:2398-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd, D. A., T. Cabral, P. Van Caeseele, J. Wylie, and M. R. Mulvey. 2002. Molecular characterization of the vanE gene cluster in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis N00-410 isolated in Canada. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1977-1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bugg, T. D. H., G. D. Wright, S. Dutka-Malen, M. Arthur, P. Courvalin, and C. T. Walsh. 1991. Molecular basis for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147: biosynthesis of a depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursor by vancomycin resistance proteins VanH and VanA. Biochemistry 30:10408-10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Depardieu, F., M. G. Bonora, P. E. Reynolds, and P. Courvalin. 2003. The vanG glycopeptide resistance operon from Enterococcus faecalis revisited. Mol. Microbiol. 50:931-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutka-Malen, S., C. Molinas, M. Arthur, and P. Courvalin. 1992. Sequence of the vanC gene of Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174 encoding a d-alanine:d-alanine ligase-related protein necessary for vancomycin resistance. Gene 112:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta, I., and P. E. Reynolds. 2002. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the vanC-2 vancomycin resistance gene cluster of Enterococcus casseliflavus ATCC 25788. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3125-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutta, I., and P. E. Reynolds. 2003. The vanC-3 vancomycin resistance gene cluster of Enterococcus flavescens CCM 439. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:703-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fines, M., B. Périchon, P. Reynolds, D. F. Sahm, and P. Courvalin. 1999. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2161-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gholizadeh, Y., and P. Courvalin. 2000. Acquired and intrinsic glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16:S11-S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grohs, P., L. Gutmann, R. Legrand, B. Schoot, and J. L. Mainardi. 2000. Vancomycin resistance is associated with serine-containing peptidoglycan in Enterococcus gallinarum. J. Bacteriol. 182:6228-6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healy, V. L., I. S. Park, and C. T. Walsh. 1998. Active-site mutants of the VanC-2 d-alanyl:d-serine ligase, characteristic of one vancomycin-resistant phenotype, revert towards wild-type d-alanyl:d-alanine ligases. Chem. Biol. 5:197-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclercq, R., E. Derlot, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1988. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N. Engl. J. Med. 319:157-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leclercq, R., S. Dutka-Malen, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1992. Vancomycin resistance gene vanC is specific to Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2005-2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lessard, I. A. D., and C. T. Walsh. 1999. Mutational analysis of active-site residues of the enterococcal d-Ala-d-Ala dipeptidase VanX and comparison with Escherichia coli d-Ala-d-Ala ligase and d-Ala-d-Ala carboxypeptidase VanY. Chem. Biol. 6:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKessar, S. J., A. M. Berry, J. M. Bell, J. D. Turnidge, and J. C. Paton. 2000. Genetic characterization of vanG, a novel vancomycin resistance locus of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3224-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navarro, F., and P. Courvalin. 1994. Analysis of genes encoding d-alanine:d-alanine ligase-related enzymes in Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1788-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park, I.-S., C.-H. Lin, and C. T. Walsh. 1997. Bacterial resistance to vancomycin: overproduction, purification, and characterization of VanC2 from Enterococcus casseliflavus as a d-Ala:d-Ser ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10040-10044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrick, W. M., J. Weisner, and J. M. Blackburn. 2002. Site-directed mutagenesis of Tyr354 in Geobacillus stearothermophilus alanine racemase identifies a role in controlling substrate specificity and a possible role in the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Chem. Biochem. 8:789-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podmore, A. H. B., and P. E. Reynolds. 2002. Purification and characterization of VanXYC, a d,d-dipeptidase/d,d-carboxypeptidase in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2740-2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds, P. E. 1989. Structure, biochemistry and mechanism of action of glycopeptide antibiotics. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 8:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds, P. E. 1998. Control of peptidoglycan synthesis in vancomycin-resistant enterococci: d,d-peptidases and d,d-carboxypeptidases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 54:325-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds, P. E., C. A. Arias, and P. Courvalin. 1999. Gene vanXYC encodes d,d-dipeptidase (VanX) and d,d-carboxypeptidase (VanY) activities in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Mol. Microbiol. 34:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds, P. E., F. Depardieu, S. Dutka-Malen, M. Arthur, and P. Courvalin. 1994. Glycopeptide resistance mediated by enterococcal transposon Tn1546 requires production of VanX for hydrolysis of d-alanyl-d-alanine. Mol. Microbiol. 13:1065-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds, P. E., H. A. Snaith, A. J. Maguire, S. Dutka-Malen, and P. Courvalin. 1994. Analysis of peptidoglycan precursors in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Biochem. J. 301:5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahm, D. F., L. Free, and S. Handwerger. 1995. Inducible and constitutive expression of vanC-1-encoded resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1480-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uttley, A. H. C., C. H. Collins, J. Naidoo, and R. C. George. 1988. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet i:57-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh, C., S. L. Fischer, I.-S. Park, M. Prahalad, and Z. Wu. 1996. Bacterial resistance to vancomycin: five genes and one missing hydrogen bond tell the story. Chem. Biol. 3:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodford, N. 2001. Epidemiology of the genetic elements responsible for acquired glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu, Z., G. D. Wright, and C. T. Walsh. 1995. Overexpression, purification, and characterization of VanX, a d,d-dipeptidase which is essential for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. Biochemistry 34:2455-2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]