Abstract

Iron-sulfur centers in metalloproteins can access multiple oxidation states over a broad range of potentials, allowing them to participate in a variety of electron transfer reactions and serving as catalysts for high-energy redox processes. The nitrogenase FeMoCO cluster converts di-nitrogen to ammonia in an eight-electron transfer step. The 2(Fe4S4) containing bacterial ferredoxin is an evolutionarily ancient metalloprotein fold and is thought to be a primordial progenitor of extant oxidoreductases. Controlling chemical transformations mediated by iron-sulfur centers such as nitrogen fixation, hydrogen production as well as electron transfer reactions involved in photosynthesis are of tremendous importance for sustainable chemistry and energy production initiatives. As such, there is significant interest in the design of iron-sulfur proteins as minimal models to gain fundamental understanding of complex natural systems and as lead-molecules for industrial and energy applications. Herein, we discuss salient structural characteristics of natural iron-sulfur proteins and how they guide principles for design. Model structures of past designs are analyzed in the context of these principles and potential directions for enhanced designs are presented, and new areas of iron-sulfur protein design are proposed.

Keywords: iron-sulfur, metalloprotein, protein design, oxidoreductase, symmetry

1. Introduction

The construction of synthetic proteins from first principles, i.e. de novo design, requires understanding the physical and chemical features of the individual amino acids and their collective structural and functional properties. The properly chosen sequence will assume a desired three-dimensional fold with the appropriate precision to facilitate the target function. Metalloproteins have been a particularly powerful platform for developing and testing de novo design methods in part due to strong metal-ligand interactions and stringent constraints on coordination geometry that can provide both stability and fold-specificity to a design [1, 2]. Metalloproteins are also attractive design applications as metals and metal-containing cofactors in proteins are central in a significant fraction of bioenergetic and catalytic processes [3, 4]. Synthetic metalloproteins can serve as minimalist model systems to study behaviors of more complex natural counterparts, and potentially develop novel oxidoreductases with tunable electrochemical and catalytic properties.

Most progress in metalloprotein design has focused on mononuclear metal sites. A notable exception is the duo ferro (two-iron) series of designs, which have explored numerous aspects of structure and reactivity of enzymes such as ribonucleotide reductase and methane monooxygenase, using a minimal model of a common dinuclear center within a four-α-helix bundle [5]. Other de novo systems with multinuclear metal sites exist [6], but examples where high-resolution structures have been solved are rare. This is due to a combination of challenges including effective de novo design of host proteins, synthesis and assembly of metal clusters in proteins, and characterization of structure and activity. However, multinuclear metal sites are central to the function of core reactions in biology including the oxygen evolving complex in photosystem II (Mn4O5Ca) or the nitrogen fixing FeMoCo cluster (Fe7MoCS8), and model proteins would allow critical study of structural elements required for catalysis.

Iron-sulfur complexes are among the most prevalent multinuclear metal sites in proteins. They are of tremendous interest for their electron transfer properties in oxidoreductases and roles in catalysis. Their prevalence is thought to be due to their early emergence in protein evolution, with bacterial ferredoxin possibly among the earliest occurring metallo-folds [7–11]. The ancient ocean prior to the great oxygenation event 2.3 billion years ago was potentially sulfidic and rich in soluble iron, in sharp contrast to the modern ocean [12, 13]. Thus there is a need to develop model systems to understand how the large diversity of extant iron-sulfur proteins function and potentially explore how the first oxidoreductases may have evolved.

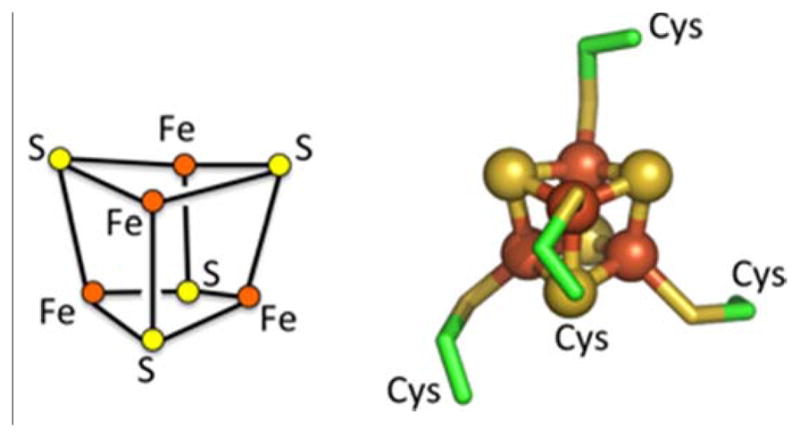

This review primarily highlights efforts in the design of novel protein scaffolds for Fe4S4 clusters (Fig 1). In these cubane structures, each iron is tetrahedrally coordinated by four sulfurs, three from within the cluster and the fourth from a cysteine ligand. Due to the multiple possible oxidation states of the four irons, a number of cluster oxidation states from [Fe4S4]0 to [Fe4S4]4+ are theoretically possible. Exchange between the 2+ and 3+ states occurs in high-potential iron proteins around +0.4 V vs. NHE. In bacterial ferredoxin, exchange between the 1+ and 2+ states occurs as low as −0.6 V [16]. The highly reduced 0+ state is proposed to occur in nitrogenase [17]. Clusters also serve non-redox active site roles in enzymes such as aconitase. We will explore the ways Fe4S4 cluster metal coordination constrain a protein fold and how geometric and energetic considerations of first and second shell interactions can be used to guide future designs.

Figure 1.

Cubane Fe4S4 cluster composition and structure. Molecular structure of cluster and first-shell ligands from bacterial ferredoxin (PDB ID: 2FDN)[14, 15].

2. Cluster constraints on design

One of the challenges in metalloprotein design is choosing a protein fold that adequately presents first-shell ligands in an appropriate geometry to coordinate the metal without significant distortions that lead to an energetically unfavorable interaction. One class of approaches starts from a protein fold or library of potential folds, and seeks to identify a set of positions where ligands can be introduced and adopt conformations compatible with metal coordination. This incorporation can be done rationally or in a semi-automated fashion through the use of computational tools [18, 19]. An example of this approach was the successful incorporation of a Fe4S4 binding site into thioredoxin by replacing a cluster of four interacting hydrophobic amino acids with cysteines. This approach was generalized in the ROSETTA software platform for design of any protein-substrate interaction using an inverse-rotamer construct, which consists of the substrate coordinate to key interacting residues [20–22]. Sampling of sidechain rotamers results in an ensemble of backbone positions. These are then matched to potential scaffolds using a geometric hashing protocol adopted from work in the field of computer automated image recognition [23].

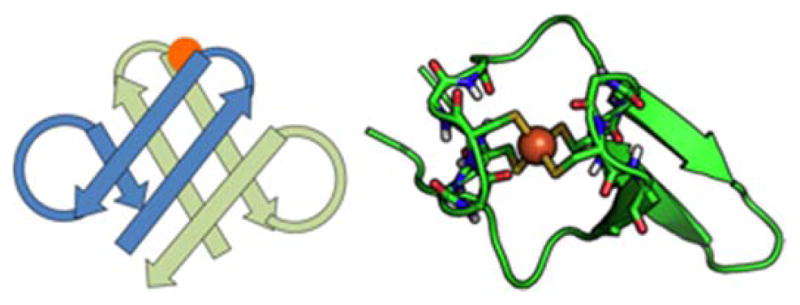

An alternative approach takes advantage of the observation that many metal binding proteins have symmetric elements that match the internal metal coordination symmetry. For example, the tetrahedral mononuclear iron site in the electron shuttling protein rubredoxin has a two-fold axis that matches pseudosymmetry between two beta-hairpins that coordinate the metal, leading to the design of a minimal rubredoxin mimic (Fig 2) [5, 24]. The diiron sites in ribonucleotide reductase or methane monooxygenase have two orthogonal two-fold axes which are reflected in the metal-binding four-helix bundles at the center of these larger proteins [5, 25]. Pseudosymmetric folds in natural proteins can be converted into idealized secondary structural elements that serve as scaffolds for the design of minimal metal binding proteins [24, 26–30]. A key advantage of symmetry in design is that it reduces the sequence space to be searched. Symmetric proteins can be examined as oligomeric assemblies of the structural elements before single-chain constructs connecting all elements are attempted [26]. This allows the use of dynamic library type approaches to experimentally identify optimal metal coordinating sequences [31, 32].

FIGURE 2.

rubredoxin showing structure and second shell coordination, use of symmetry

A minimal rubredoxin mimic was constructed based on an observed two-fold pseudosymmetry in the P. furiosus rubredoxin protein [24, 33].

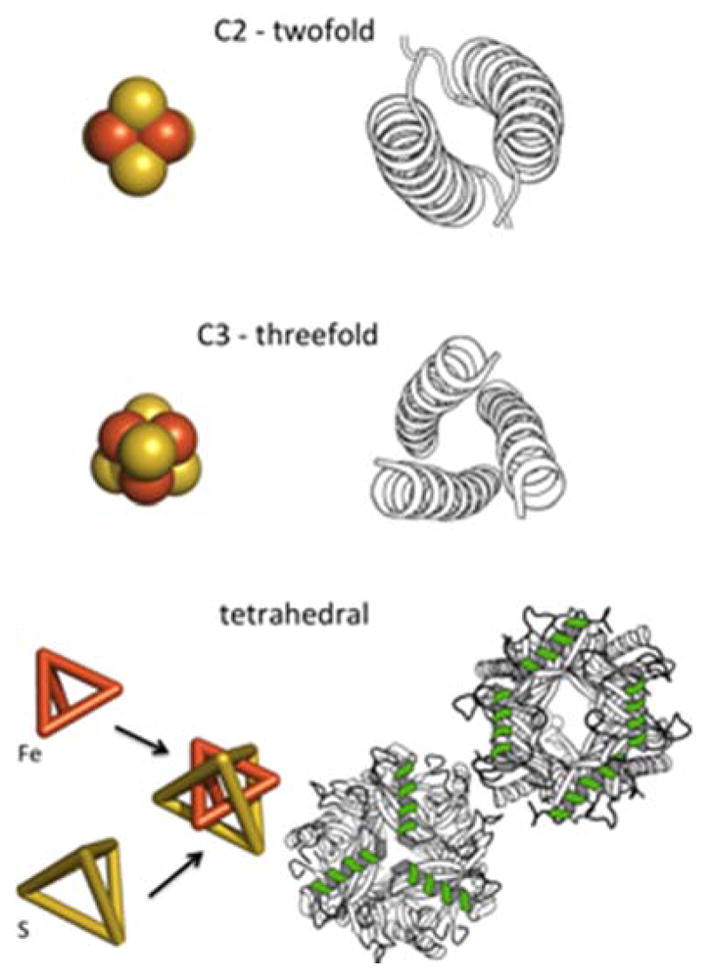

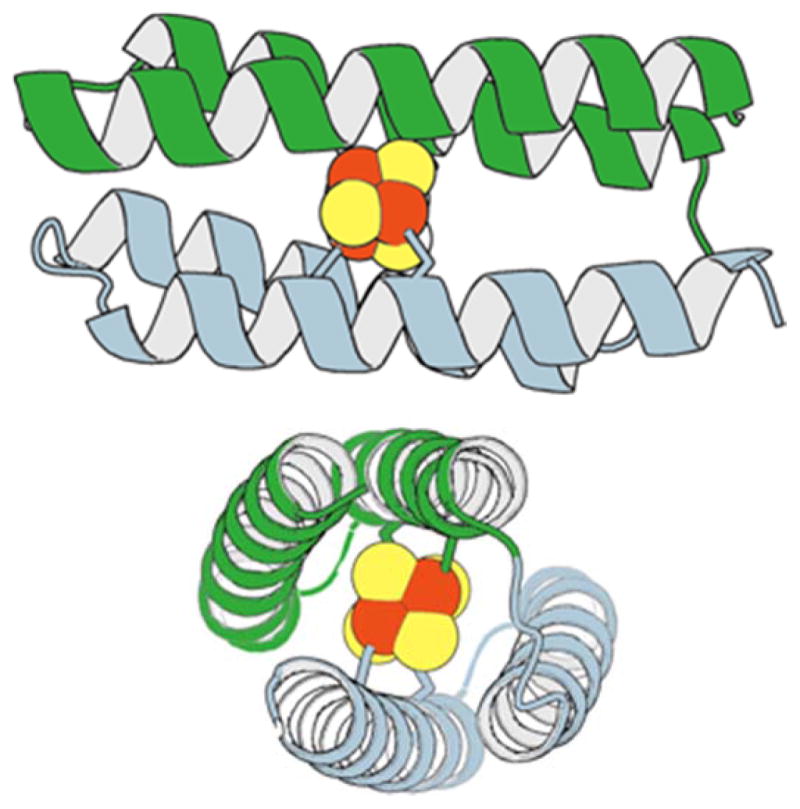

The Fe4S4 cluster has multiple two and three-fold axes, suggesting possible coordination by two or three-element folds such as helical dimers and trimers (Fig. 3). The combination of symmetry axes leads to tetrahedral symmetry of the cluster, which is rarely observed in single chain proteins and generally occurs in self-assembled protein cages. Despite the various degrees of symmetry, there are no clear examples of single chain Fe4S4 binding domains where protein topology matches two-fold, three-fold or tetrahedral symmetry of the cluster. The Fe4S4 cluster in the nitrogenase Fe protein sits at a dimer interface, where the two-fold axes of the dimer and the cluster are coincident [33]. As presented later in the review, local folds of iron-sulfur clusters are distinct from those of other metal sites, occurring in loops between helices and sheets, rather than occurring within the secondary structures, making symmetry-guided design more challenging.

Figure 3.

Symmetries of the Fe4S4 cluster and examples of related protein topologies.

An application of Fe4S4 cluster symmetry is using deviations from ideal geometry as a tool for estimating the energetics of distortion imposed by the ligand environment. If four points in space are not all in one plane, they define a unique sphere termed a circumsphere. The Fe4S4 cluster can be thought of containing three such circumspheres defined by the four irons, the four cluster sulfurs and the four coordinating cysteine sulfurs [34]. Under idealized geometry conditions, the centers of all three circumspheres would be coincident. Distortions can be described by the distance between circumsphere centers. By comparison to DFT based calculations of stability, it was shown that while distortions within the two cluster circumspheres were of low energy, distortions between the cluster and the cysteine sulfurs required significant energetic constraints from the protein. Although primarily used to evaluate the properties of experimentally determined structures, the circumsphere construction may also prove to be a valuable construct for developing Fe4S4 model protein designs.

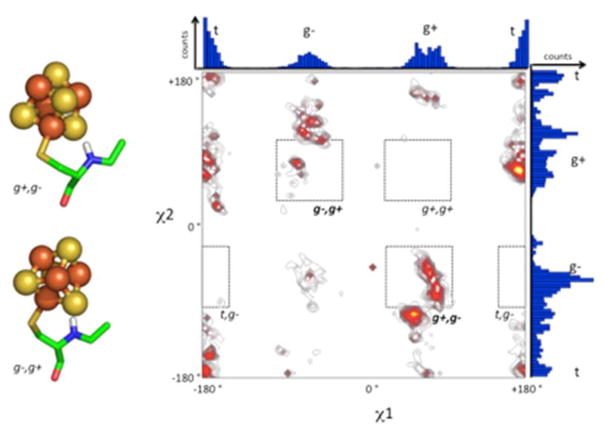

Cluster binding by first-shell cysteine ligands alter the accessible conformational states relative to that of an uncoordinated residue. Understanding such metal-ligand effects can be useful in computational protein design to constrain sampling of amino acid conformations. Analyses of heme and chlorophyll binding sites in proteins uncovered significant constraints and context-dependent conformational preferences for these cofactors [35, 36]. In addition to rotation along the Cα-Cβ bond (the χ1 rotamer), bound cysteine has an additional χ2 rotamer along the Cβ-Sγ bond (Fig. 4). The observed χ1 distribution for bound cysteine deviates significantly from that of the backbone-independent distribution for equivalent uncoordinated groups [37, 38], indicating constraints imposed by the cluster. Examination of available high-resolution protein structures in the PDB show clear discrete conformational preferences for χ1, χ2 pairs. Classifying rotamers for bound cysteine as gauche+/g+ = 60°, gauche−/g− = −60° and trans/t = 180°, the conformational preferences can be partially explained by pentane interference [39], where the cluster-backbone carbonyl clashes prevent g+,g+ and t,g− conformations from occurring. In contrast to the syn-pentane scheme, rotamers that bring the iron-sulfur cluster close to the backbone amide are highly favored, specifically g−,g+ and g+,g−. Favorable electrostatic interactions between the backbone amide and the anionic cluster sulfurs likely explain the prevalence of g−,g+ and g+,g− [40, 41]. For the g+,g+ or t,g− states, cluster-backbone interactions would likely be repulsive.

Figure 4.

Analysis of Cys-Fe4S4 rotamer preferences from known structures in the PDB. χ1 = N-Cα-Cβ-Sγ; χ2 = Cα-Cβ-Sγ-Fe. g+ = 60°, g− = −60°, t = 180°. High occupancy c1,c2 pairs highlighted in red and yellow in the contour plot. Individual histograms for ×1 and ×2 are drawn along their respective axes. Regions of expected backbone-cluster clashes are within dotted line boxes. Structures of g−,g+ and g+,g− rotamers show favorable backbone amide to cluster hydrogen bond instead of the expected clash.

Other degrees of freedom could also be constructed to assist in analyzing and modeling ligand-cluster interactions. A χ3 exists (Cβ-Sγ-Fe-S), which could potentially be affected by steric interactions with the protein chain. Deviations from ideal bond lengths and angles could be combined with terms such as the circumsphere to evaluate the stability of ligand-cluster configurations.

3. Fe4S4 binding site sequence and structure motifs

Repeating patterns in the sequences of Fe4S4 binding proteins have been seen since the first days of protein sequence analysis [9]. Most cluster binding proteins have characteristic CxxCxxC … C motifs where three cysteines are relatively adjacent in sequence, separated by one, two or three amino acids, followed by the fourth cysteine which is distal in sequence, occurring either before or after the body of the motif [42, 43]. A more detailed analysis of bacterial ferredoxin sequences revealed key non-ligand positions that contributed to Fe4S4 assembly [44]. A consensus sequence CIACGAC was shown to not only be sufficient to assemble a complete cluster, but also behave better than highly flexible CGGCGGC or a constrained CAACAAC sequence, indicating critical conformational contributions of the non-ligand residues. Ferredoxin maquettes were engineered into designed heme binding peptide [45], resulting in a protein that bound both heme and Fe4S4 cofactors. Similar maquette-based strategies have been used as models to explore the properties of photosystems [46] and the cluster assembly pathway [47]. A recent sequence analysis of Fe4S4 sites in known oxidoreductases identified several fundamental sequence profiles that correlated strongly with annotated function [48]. How these profiles correspond to structure require a systematic evaluation of iron-sulfur protein structures in the PDB.

The large number of high-resolution structures of Fe4S4 containing proteins potentially allows a molecular-level understanding of key conformational features of cluster binding sites. Given the antiquity of iron-sulfur proteins, a few billion years of evolution makes the identification of homologs based on sequence homology challenging [11]. Nearly all Fe4S4 sites have some variation on the C…C…C motif with different numbers of intervening non-ligand positions. Even structure-based alignments are challenged by the variations in topology that emerge over long evolutionary time scales. Although a number of studies clustering and classifying metalloproteins based on their fold are available [49–52], in order to take full advantage of the structural information in the PDB, it was necessary to develop methods that could detect weak structural homology of distantly related folds.

A successful strategy for automated detection of weak structural homology was recently presented that integrated knowledge of metal site composition and location within the fold into the evaluation of the alignment of metalloproteins [53]. In this approach, only portions of the protein adjacent to the metal site were evaluated for structural homology, based on the hypothesis that regions adjacent to the cluster would be constrained to evolve more slowly due to structural and functional limitation imposed by metal binding. Alignments were calculated using the TopMatch platform [54, 55], and scored according to number of aligned residues and RMSD of backbone coordinates, as well as distance between the centerpoints of the aligned metal-ligands. Those alignments with structural distances below a defined threshold and where the two metal centers coincide are more likely to be valid.

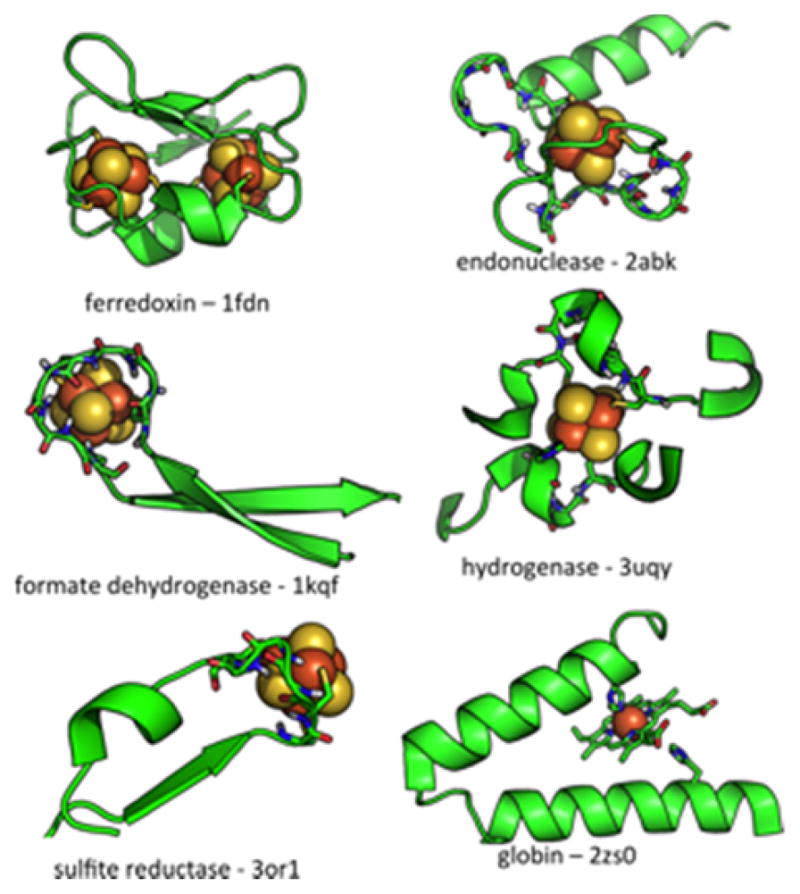

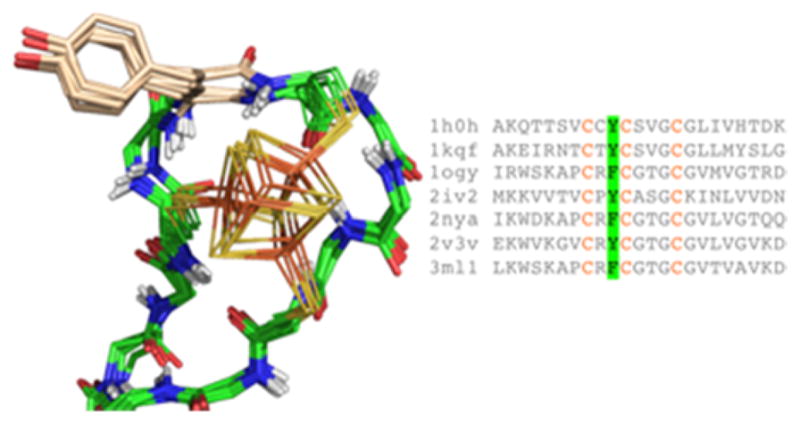

Using this approach, over forty distinct Fe4S4-binding folds were clustered from a curated set of structures in the PDB. The top five largest clusters had at least ten examples (Fig. 5), with the bacterial ferredoxin fold having over 100 examples [53]. In all of the major clusters, cysteine ligands are located in non-helix/sheet regions of the fold. This is in contrast to other cofactors such as heme, where the majority of histidine ligands are found in helical elements [36, 56]. The fact that nearly all clusters reside in protein loops, coils and turns makes them challenging to recapitulate using existing structure-based design methods. However, it would be a mistake to assume that these motifs are highly flexible or variable in structure. Within each cluster, the conformations of ligand and non-ligand residues are very similar, even across distantly related proteins. For example, the overlay of structures related a cluster binding beta-hairpin loop in formate dehydrogenase shows surprising conformational similarity despite low inter-sequence homology, indicating significant conformational constraints imposed by the cluster (Fig. 6). Even the position and rotameric conformation of a bulky aromatic group, which may be facilitating cluster assembly [47], is nearly identical across a wide variety of proteins. This suggests that local sequence and structure can to a large extent modulate cluster assembly, motivating the fragment-based approach of examining the structural and electrochemical properties of natural Fe4S4 protein models.

Figure 5.

Core Fe4S4 binding motifs determined by structural homology search [53]. Cluster binding motifs are found in regions between helical and sheet elements. In contrast, the heme binding domain of the globin fold is located within an α-helix.

Figure 6.

Conserved cluster binding site in the loop connecting a β-hairpin. Despite significant sequence variation both within and outside the motif, structures are highly similar. A conserved aromatic packs against the cluster.

The lack of periodic secondary structural elements within the cluster binding site highlights the importance of second-shell interactions in stabilizing the structure and oxidation state transitions of the cluster. A common feature of Fe4S4 binding sites is an extensive network of backbone amide nitrogen to proton bonds directed toward the cluster and coordinating cysteine sulfurs. These types of structures have been termed cationic ‘nests’ due to the local concentration of acidic amides, binding to anionic ‘eggs’ [57]. They are found coordinating a wide variety of anionic substrates such as aspartate and glutamate sidechain carboxylates at the amino-termini of α-helices [58], or phosphorylated sidechains[59]. In α-helices and β-sheets, these amides are occupied in backbone hydrogen bonding networks, making them unavailable for cluster interactions. The importance of these hydrogen bonding networks for stabilizing oxidation states of ferredoxins, HiPIP and other redox active proteins has long been postulated [40, 41]. Preservation of these interactions in a designed rubredoxin mimic was hypothesized to be responsible for the significant stability of this protein to multiple cycles of oxidation and reduction [24]. In other metal sites, second shell interactions are frequently contributed by adjacent polar amino acid sidechains [60, 61]. In the case of cysteine-cluster conjugates, the short sidechain and bulky cluster provide little steric access for other sidechain moieties to contribute second shell interactions.

Incorporating these backbone mediated second shell interaction networks presents a unique challenge for de novo computational protein design, requiring sampling of coordinated backbone degrees of freedom within the context of a constrained cluster-ligand complex, and developing effective interaction potentials that consider the energetics of backbone amides hydrogen bonding to the cluster and first shell ligands. The unique rotamer distributions of a Cys-cluster complex, specifically the prevalence of otherwise unusual g+,g− and g−,g+ states, can be used to bias conformational sampling toward favorable second-shell interactions. Exhaustive sampling of backbone conformations for short cysteine containing chains can also be used to identify favorable loop and turn scaffolds. This approach was used for modeling the conformations of short heptapeptides CxxCxxC. Optimization of electrostatic interactions between the peptide backbone and the cluster-ligand complex resulted in chain conformations that match topological properties of natural iron-sulfur binding sites [62].

4. Helical de novo designs

Analysis of natural metalloproteins provides important structural insight into how proteins control binding, assembly and function of Fe4S4 clusters. However, natural proteins are complex devices that have evolved under a number of functional constraints, many of which may be unknown. Thus, the design of minimal systems allows us to study elements of these complex proteins in isolation. Significant progress in the study of iron-sulfur proteins has come through the design of maquettes and protein fragments [44, 47, 63]. In some cases, fragments of natural proteins are incorporated into rationally designed proteins to produce novel or hybrid folds [45, 46]. The de novo design of cluster binding proteins stringently tests our understanding of constraints on metalloprotein structure and function. In this section, we deconstruct two recent helical de novo Fe4S4 binding proteins, coiled-coil iron-sulfur binding protein (CCIS-1) [64] and domain-swapped dimer ferredoxin (DSD-Fdm) [65, 66]. In both designs, the cluster is introduced into a novel secondary structure scaffold, an α-helical bundle. These molecules have no known analogs in nature.

Elements of the first-shell ligands of CCIS-1 and DSD-Fdm were derived from an unexpected Fe4S4 binding site discovered when the structure of tryptophan tRNA-synthetase from T. maritime was solved. Unlike most cluster binding motifs, which primarily occur in between secondary structural elements, the cysteine ligands are all found in or at the ends of α-helical elements (Fig. 7). Only two currently known structures contain this type of binding site - PDB ID: 2G36 [67] and 3A04 (Tsuchiya, W., Fujimoto, Z., Hasegawa, T.; unpublished) - both tryptophan tRNA synthetases from thermophilic organisms. Given that most of the backbone amides that would normally contribute to electrostatic interactions with the cluster participate in intra-helical hydrogen bonds, other groups in the protein replace these missing interactions. One of the cysteines sits at the N-terminus of a helix, placing the cluster at the top of these exposed amides. An adjacent arginine and lysine are found with the cationic portion of their sidechains interacting directly with the cluster. Additional backbone amides outside of the cysteine containing part of the chain also make amide donor hydrogen bonds to the cluster. Given the placement of this cluster within α-helices, there have been several attempts to incorporate elements of this binding site into de novo proteins.

Figure 7.

The unusual Fe4S4 binding site in tryptophan tRNA-synthetase is located between three helical elements.

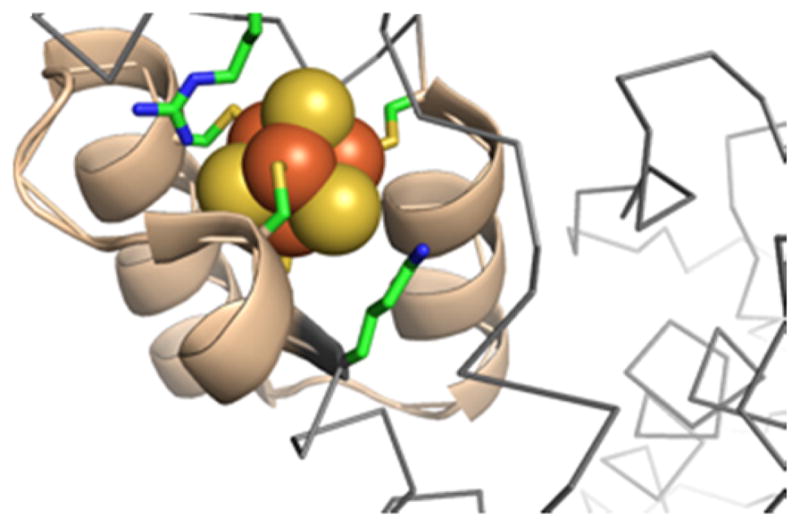

The CCIS-1 design utilized two cysteines from tryptophan tRNA synthetase. These ligands (Cys 266 and 269 from the T. maritima structure [67]) formed a CxxC motif that formed one turn of an α-helix. A second coordinating helix was specified, duplicating this interaction using a two-fold symmetry axis of the cluster. The final design was a four-helix bundle (Fig. 8) that buried the cluster within the hydrophobic center of the protein. Although binding of the cluster was clearly demonstrated, the protein was prone to aggregation and unstable to oxidation-reduction cycles. Subsequent attempts to improve solubility by increasing net charge of the protein, or to increase stability by adding helix-favoring amino acids did little to improve physical properties of the protein [68]. We recently relaxed the CCIS-1 model structure using the AMBER molecular simulation platform [69] and found that the cysteine ligands deviated from the originally specified rotamers, possibly due to strain imposed on the binding site by the four-helix bundle fold. As such, improving the stability of this protein would require significant revision of the starting scaffold.

Figure 8.

The two-fold symmetry axis of the Fe4S4 cluster is recapitulated in the topology of the four-helix CCIS-1 bundle.

Recently, the Ghirlanda laboratory developed DSD-Bis[4Fe-4S] [66], which incorporated a Fe4S4 site into Domain-Swapped Dimer (DSD) [70], a three-helix bundle that formed a dimer with a two-fold symmetry axis. Within each monomer, there was an optimal site for incorporation of a cluster using the tryptophan tRNA-synthase CxxC ligand geometries. The C2-symmetry of the dimer allowed for incorporation of a second metal site (Fig. 9). Upon molecular mechanics conformational relaxation of this model, we find that the rotameric states of the CxxC element in the binding site are preserved relative to tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase. The dimer KD of the original DSD design was in the picomolar range and the melting temperature at 105°C – making this a robust starting scaffold [70]. In a follow-up study, a variant of the design, DSD-Fdm (DSD ferredoxin mimic) was constructed which moved the two metal centers toward the center of the bundle by taking advantage of the regular heptad periodicity of the α-helix [65]. This brought the two Fe4S4 clusters from to 36 to 12 Å apart, allowing for effective electron transfer to occur between clusters, as occurs in bacterial ferredoxin. The DSD-based modes can be used to perturb first [71] and second shell interactions in order to gain a better understanding of how the local protein environment can be used to tune the redox behavior of these clusters.

Figure 9.

Above – bacterial ferredoxin with two-fold pseudosymmetry in the structure highlighted in blue and green elements. Below – the DSD-Fdm design incorporating two Trp tRNA-synthease like sites, one per monomer. Model constructed from the DSD structure (PDB ID: 1G6U [70]).

5. Future directions

The de novo route of Fe4S4 metalloprotein design offers several advantages – tuning target oxidation states by engineering appropriate hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions in the cluster microenvironment, controlling placement of multiple clusters to modulate electron transfer kinetics, and incorporating clusters into de novo oxidoreductases to drive functional redox chemistry. For many of these goals, appropriately designed helical scaffolds hold much promise as they can provide structural stability and both topological and helical symmetry to facilitate multi-cluster molecules. In de novo porphyrin containing proteins, the helical topology has allowed the design of multi-cofactor nanowires [72, 73] – and similar strategies could be imagined for incorporating iron-sulfur clusters. As seen with existing helical designs, minimizing conformational strain by accommodating low-energy first shell ligand rotamers may be key for producing robust metalloproteins that are stable to redox cycling. In addition to the C2 symmetry utilized in CCIS-1, there are D2 and C3 symmetry axes that are potentially exploitable by helical folds with equivalent topological symmetry. With the development of cysteine-cluster rotamer potentials and related interaction potentials [74], it should be possible to align members from an ensemble of low-energy cluster-ligand conformations to libraries of parametrically specified helical bundles. Additionally, engineering second-shell cationic residues in the absence of available backbone amide groups will likely be important in improving utility of these scaffolds.

Perhaps more challenging for state-of-the-art computational methods will be the de novo design of new cluster binding folds that do not depend on regular secondary structure, allowing for backbone amides to participate in second-shell interactions with the cluster and first-shell ligands. This is the strategy that has been most thoroughly explored in natural cluster containing oxidoreductases – and effective methods for classifying the core structural elements within these proteins should allow us to develop molecular potentials that effectively balance protein-protein and protein-cluster interactions to produce high-affinity cluster binding motifs that do not impose conformational strain on the protein topology. Such proteins can also be used as models to evaluate the relative contributions of protein and solvent interactions [16]. The advantages of this strategy are the ability to tune designed protein redox potentials over a wide range, much as occurs across nitrogenase Fe protein, HiPIP and ferredoxin, and the stabilization of multiple oxidation states during redox cycling.

Design strategies and molecular potentials developed in the pursuit of Fe4S4 metalloproteins are expected to advance the larger goal of developing proteins that control the assembly of specific multinuclear complexes. These designs not only include naturally occurring clusters such as the water-splitting complex or the nitrogenase FeMoCO site, but also synthetic multinuclear catalysts that carry out similar chemistry [75, 76] and nonbiological reactions [77], bridging the gap between homo- and heterogeneous catalysis [78]. One could imagine that in designing such proteins, we may also be seeing backward in evolutionary time toward proteins that interacted with minerals and formed the first bioinorganic catalysts [11, 62, 79].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DP2 OD-006478 and R01 GM-089949 and by the European Research Council Consolidator Grant.

References

- 1.Handel TM, Williams SA, DeGrado WF. Metal ion-dependent modulation of the dynamics of a designed protein. Science. 1993;261(5123):879–85. doi: 10.1126/science.8346440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson DE, Farid RS, Moser CC, Urbauer JL, Mulholland SE, Pidikiti R, Lear JD, Wand AJ, DeGrado WF, Dutton PL. Design and synthesis of multi-haem proteins. Nature. 1994;368(6470):425–32. doi: 10.1038/368425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkins DW, Armstrong CT, Anderson JL. De novo protein components for oxidoreductase assembly and biological integration. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;19:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farid TA, Kodali G, Solomon LA, Lichtenstein BR, Sheehan MM, Fry BA, Bialas C, Ennist NM, Siedlecki JA, Zhao Z, Stetz MA, Valentine KG, Anderson JL, Wand AJ, Discher BM, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Elementary tetrahelical protein design for diverse oxidoreductase functions. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(12):826–33. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombardi A, Summa CM, Geremia S, Randaccio L, Pavone V, DeGrado WF. Retrostructural analysis of metalloproteins: application to the design of a minimal model for diiron proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6298–305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaytsev DV, Morozov VA, Fan J, Zhu X, Mukherjee M, Ni S, Kennedy MA, Ogawa MY. Metal-binding properties and structural characterization of a self-assembled coiled coil: formation of a polynuclear Cd-thiolate cluster. J Inorg Biochem. 2013;119:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caetano-Anolles G, Kim HS, Mittenthal JE. The origin of modern metabolic networks inferred from phylogenomic analysis of protein architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(22):9358–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701214104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupont CL, Butcher A, Valas RE, Bourne PE, Caetano-Anolles G. History of biological metal utilization inferred through phylogenomic analysis of protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(23):10567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912491107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eck RV, Dayhoff MO. Evolution of the structure of ferredoxin based on living relics of primitive amino Acid sequences. Science. 1966;152(3720):363–6. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3720.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darimont B, Sterner R. Sequence, assembly and evolution of a primordial ferredoxin from Thermotoga maritima. EMBO J. 1994;13(8):1772–81. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harel A, Bromberg Y, Falkowski PG, Bhattacharya D. Evolutionary history of redox metal-binding domains across the tree of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(19):7042–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403676111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berner RA, Canfield DE. A new model for atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time. Am J Sci. 1989;289(4):333–61. doi: 10.2475/ajs.289.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canfield DE, Teske A. Late Proterozoic rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration inferred from phylogenetic and sulphur-isotope studies. Nature. 1996;382(6587):127–32. doi: 10.1038/382127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dauter Z, Wilson KS, Sieker LC, Meyer J, Moulis JM. Atomic Resolution (0.94 Å) Structure of Clostridium acidurici Ferredoxin. Detailed Geometry of [4Fe-4S] Clusters in a Protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36(51):16065–16073. doi: 10.1021/bi972155y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dey A, Jenney FE, Jr, Adams MW, Babini E, Takahashi Y, Fukuyama K, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. Solvent tuning of electrochemical potentials in the active sites of HiPIP versus ferredoxin. Science. 2007;318(5855):1464–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1147753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs D, Watt GD. Nucleotide-assisted [Fe4S4] redox state interconversions of the Azotobacter vinelandii Fe protein and their relevance to nitrogenase catalysis. Biochemistry. 2013;52(28):4791–9. doi: 10.1021/bi301547b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellinga HW. The construction of metal centers in proteins by rational design. Fold Des. 1998;3(1):R1–8. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemba M, Gardner KH, Marino S, Clarke ND, Regan L. Novel metal-binding proteins by design. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2(5):368–73. doi: 10.1038/nsb0595-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanghellini A, Jiang L, Wollacott AM, Cheng G, Meiler J, Althoff EA, Rothlisberger D, Baker D. New algorithms and an in silico benchmark for computational enzyme design. Protein Sci. 2006;15(12):2785–94. doi: 10.1110/ps.062353106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, DeChancie J, Betker J, Gallaher JL, Althoff EA, Zanghellini A, Dym O, Albeck S, Houk KN, Tawfik DS, Baker D. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453(7192):190–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khare SD, Kipnis Y, Greisen P, Jr, Takeuchi R, Ashani Y, Goldsmith M, Song Y, Gallaher JL, Silman I, Leader H, Sussman JL, Stoddard BL, Tawfik DS, Baker D. Computational redesign of a mononuclear zinc metalloenzyme for organophosphate hydrolysis. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(3):294–300. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamdan Y, Schwartz JT, Wolfson HJ. Affine invariant model-based object recognition. Robotics and Automation, IEEE Transactions on. 1990;6(5):578–589. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nanda V, Rosenblatt MM, Osyczka A, Kono H, Getahun Z, Dutton PL, Saven JG, Degrado WF. De novo design of a redox-active minimal rubredoxin mimic. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(16):5804–5. doi: 10.1021/ja050553f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summa CM, Lombardi A, Lewis M, DeGrado WF. Tertiary templates for the design of diiron proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9(4):500–8. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summa CM, Rosenblatt MM, Hong JK, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Computational de novo design, and characterization of an A(2)B(2) diiron protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;321(5):923–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maglio O, Nastri F, Pavone V, Lombardi A, DeGrado WF. Preorganization of molecular binding sites in designed diiron proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):3772–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730771100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wade H, Stayrook SE, Degrado WF. The structure of a designed diiron(III) protein: implications for cofactor stabilization and catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(30):4951–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.North B, Summa CM, Ghirlanda G, DeGrado WF. D(n)-symmetrical tertiary templates for the design of tubular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2001;311(5):1081–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghirlanda G, Osyczka A, Liu W, Antolovich M, Smith KM, Dutton PL, Wand AJ, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a D2-symmetrical protein that reproduces the diheme four-helix bundle in cytochrome bc1. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(26):8141–7. doi: 10.1021/ja039935g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper HJ, Case MA, McLendon GL, Marshall AG. Electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometric analysis of metal-ion selected dynamic protein libraries. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(18):5331–9. doi: 10.1021/ja021138f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Case MA, McLendon GL. Metal-assembled modular proteins: toward functional protein design. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37(10):754–62. doi: 10.1021/ar960245+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georgiadis MM, Komiya H, Chakrabarti P, Woo D, Kornuc JJ, Rees DC. Crystallographic structure of the nitrogenase iron protein from Azotobacter vinelandii. Science. 1992;257(5077):1653–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1529353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fee JA, Castagnetto JM, Case DA, Noodleman L, Stout CD, Torres RA. The circumsphere as a tool to assess distortion in [4Fe-4S] atom clusters. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8(5):519–26. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun P, Goldberg E, Negron C, von Jan M, Xu F, Nanda V, Koder RL, Noy D. Design principles for chlorophyll-binding sites in helical proteins. Proteins. 2011;79(2):463–76. doi: 10.1002/prot.22895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negron C, Fufezan C, Koder RL. Geometric constraints for porphyrin binding in helical protein binding sites. Proteins. 2009;74(2):400–16. doi: 10.1002/prot.22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunbrack RL, Jr, Cohen FE. Bayesian statistical analysis of protein side-chain rotamer preferences. Protein Sci. 1997;6(8):1661–81. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL., Jr A smoothed backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins derived from adaptive kernel density estimates and regressions. Structure. 2011;19(6):844–58. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunbrack RL, Jr, Karplus M. Conformational analysis of the backbone-dependent rotamer preferences of protein sidechains. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1(5):334–40. doi: 10.1038/nsb0594-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langen R, Jensen GM, Jacob U, Stephens PJ, Warshel A. Protein control of iron-sulfur cluster redox potentials. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(36):25625–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephens PJ, Jollie DR, Warshel A. Protein Control of Redox Potentials of Ironminus signSulfur Proteins. Chem Rev. 1996;96(7):2491–2514. doi: 10.1021/cr950045w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coldren CD, Hellinga HW, Caradonna JP. The rational design and construction of a cuboidal iron-sulfur protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(13):6635–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson MK, Smith AD. Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. 1982. Iron–sulfur proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulholland SE, Gibney BR, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. Determination of nonligand amino acids critical to [4Fe-4S]2+/+ assembly in ferredoxin maquettes. Biochemistry. 1999;38(32):10442–8. doi: 10.1021/bi9908742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibney BR, Mulholland SE, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. Ferredoxin and ferredoxin-heme maquettes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(26):15041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott MP, Biggins J. Introduction of a [4Fe-4S (S-cys)4]+1,+2 iron-sulfur center into a four-alpha helix protein using design parameters from the domain of the Fx cluster in the Photosystem I reaction center. Protein Sci. 1997;6(2):340–6. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoppe A, Pandelia ME, Gartner W, Lubitz W. [Fe(4)S(4)]- and [Fe(3)S(4)]-cluster formation in synthetic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807(11):1414–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harel A, Falkowski P, Bromberg Y. TrAnsFuSE refines the search for protein function: oxidoreductases. Integr Biol (Camb) 2012;4(7):765–77. doi: 10.1039/c2ib00131d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andreini C, Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Najmanovich RJ, Thornton JM. Structural analysis of metal sites in proteins: non-heme iron sites as a case study. J Mol Biol. 2009;388(2):356–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Degtyarenko KN, North AC, Findlay JB. PROMISE: a database of bioinorganic motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):233–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Degtyarenko K, Contrino S. COMe: the ontology of bioinorganic proteins. BMC Struct Biol. 2004;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valasatava Y, Andreini C, Rosato A. Hidden relationships between metalloproteins unveiled by structural comparison of their metal sites. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9486. doi: 10.1038/srep09486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senn S, Nanda V, Falkowski P, Bromberg Y. Function-based assessment of structural similarity measurements using metal co-factor orientation. Proteins. 2014;82(4):648–56. doi: 10.1002/prot.24442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sippl MJ, Wiederstein M. Detection of Spatial Correlations in Protein Structures and Molecular Complexes. Structure. 2012;20(4):718–728. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiederstein M, Gruber M, Frank K, Melo F, Sippl MJ. Structure-Based Characterization of Multiprotein Complexes. Structure. 2014;22(7):1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim JD, Senn S, Harel A, Jelen BI, Falkowski PG. Discovering the electronic circuit diagram of life: structural relationships among transition metal binding sites in oxidoreductases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1622):20120257. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milner-White EJ, Nissink JWM, Allen FH, Duddy WJ. Recurring main-chain anion-binding motifs in short polypeptides: nests. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2004;60:1935–1942. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904021390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aurora R, Rose GD. Helix capping. Protein Science. 1998;7(1):21–38. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afzal AM, Al-Shubailly F, Leader DP, Milner-White EJ. Bridging of anions by hydrogen bonds in nest motifs and its significance for Schellman loops and other larger motifs within proteins. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2014;82(11):3023–3031. doi: 10.1002/prot.24663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karlin S, Zhu ZY, Karlin KD. The extended environment of mononuclear metal centers in protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(26):14225–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamashita MM, Wesson L, Eisenman G, Eisenberg D. Where Metal-Ions Bind in Proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(15):5648–5652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JD, Rodriguez-Granillo A, Case DA, Nanda V, Falkowski PG. Energetic selection of topology in ferredoxins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(4):e1002463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sow TC, Pederson MV, Christensen HE, Ooi BL. Total synthesis of a miniferredoxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223(2):360–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grzyb J, Xu F, Weiner L, Reijerse EJ, Lubitz W, Nanda V, Noy D. De novo design of a non-natural fold for an iron-sulfur protein: alpha-helical coiled-coil with a four-iron four-sulfur cluster binding site in its central core. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(3):406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roy A, Sommer DJ, Schmitz RA, Brown CL, Gust D, Astashkin A, Ghirlanda G. A de novo designed 2[4Fe-4S] ferredoxin mimic mediates electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(49):17343–9. doi: 10.1021/ja510621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roy A, Sarrou I, Vaughn MD, Astashkin AV, Ghirlanda G. De novo design of an artificial bis[4Fe-4S] binding protein. Biochemistry. 2013;52(43):7586–94. doi: 10.1021/bi401199s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han GW, Yang XL, McMullan D, Chong YE, Krishna SS, Rife CL, Weekes D, Brittain SM, Abdubek P, Ambing E, Astakhova T, Axelrod HL, Carlton D, Caruthers J, Chiu HJ, Clayton T, Duan L, Feuerhelm J, Grant JC, Grzechnik SK, Jaroszewski L, Jin KK, Klock HE, Knuth MW, Kumar A, Marciano D, Miller MD, Morse AT, Nigoghossian E, Okach L, Paulsen J, Reyes R, van den Bedem H, White A, Wolf G, Xu Q, Hodgson KO, Wooley J, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Elsliger MA, Schimmel P, Wilson IA. Structure of a tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase containing an iron-sulfur cluster. Acta Crystallographica Section F. 2010;66(10):1326–1334. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110037619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grzyb J, Xu F, Nanda V, Luczkowska R, Reijerse E, Lubitz W, Noy D. Empirical and computational design of iron-sulfur cluster proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(8):1256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salomon-Ferrer R, Case DA, Walker RC. An overview of the Amber biomolecular simulation package. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Computational Molecular Science. 2013;3(2):198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogihara NL, Ghirlanda G, Bryson JW, Gingery M, DeGrado WF, Eisenberg D. Design of three-dimensional domain-swapped dimers and fibrous oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):1404–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sommer DJ, Roy A, Astashkin A, Ghirlanda G. Modulation of Cluster Incorporation Specificity in a De Novo Iron-Sulfur Cluster Binding Peptide. Biopolymers. 2015 doi: 10.1002/bip.22635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McAllister KA, Zou H, Cochran FV, Bender GM, Senes A, Fry HC, Nanda V, Keenan PA, Lear JD, Saven JG, Therien MJ, Blasie JK, DeGrado WF. Using alpha-helical coiled-coils to design nanostructured metalloporphyrin arrays. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(36):11921–7. doi: 10.1021/ja800697g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cochran FV, Wu SP, Wang W, Nanda V, Saven JG, Therien MJ, DeGrado WF. Computational de novo design and characterization of a four-helix bundle protein that selectively binds a nonbiological cofactor. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(5):1346–7. doi: 10.1021/ja044129a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torres RA, Lovell T, Noodleman L, Case DA. Density functional-and reduction potential calculations of Fe(4)S(4) clusters. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125(7):1923–1936. doi: 10.1021/ja0211104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Oweini R, Sartorel A, Bassil BS, Natali M, Berardi S, Scandola F, Kortz U, Bonchio M. Photocatalytic Water Oxidation by a Mixed-Valent (Mn3MnO3)-Mn-III-O-IV Manganese Oxo Core that Mimics the Natural Oxygen-Evolving Center. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2014;53(42):11182–11185. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shima T, Hu S, Luo G, Kang X, Luo Y, Hou Z. Dinitrogen Cleavage and Hydrogenation by a Trinuclear Titanium Polyhydride Complex. Science. 2013;340(6140):1549–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1238663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Braunstein P, Oro LA, Raithby PR, editors. Metal Clusters in Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hutchings GJ. Metal-cluster catalysts: Access granted. Nat Chem. 2010;2(12):1005–6. doi: 10.1038/nchem.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Milner-White EJ, Russell MJ. Sites for phosphates and iron-sulfur thiolates in the first membranes: 3 to 6 residue anion-binding motifs (nests) Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere. 2005;35(1):19–27. doi: 10.1007/s11084-005-4582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]