Abstract

Genome packing in viruses and prokaryotes relies on positively charged ions to reduce electrostatic repulsions, and induce attractions that can facilitate DNA condensation. Here we present molecular dynamics simulations spanning several microseconds of dsDNA packing inside nanometer-sized viral capsids. We use a detailed molecular model of DNA that accounts for molecular structure, basepairing, and explicit counterions. The size and shape of the capsids studied here are based on the 30-nanometer-diameter gene transfer agents of bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus that transfer random 4.5-kbp (1.5 μm) DNA segments between bacterial cells. Multivalent cations such as spermidine and magnesium induce attraction between packaged DNA sites that can lead to DNA condensation. At high concentrations of spermidine, this condensation significantly increases the shear stresses on the packaged DNA while also reducing the pressure inside the capsid. These effects result in an increase in the packing velocity and the total amount of DNA that can be packaged inside the nanometer-sized capsids. In the simulation results presented here, high concentrations of spermidine3+ did not produce the premature stalling observed in experiments. However, a small increase in the heterogeneity of packing velocities was observed in the systems with magnesium and spermidine ions compared to the system with only salt. The results presented here indicate that the effect of multivalent cations and of spermidine, in particular, on the dynamics of DNA packing, increases with decreasing packing velocities.

Introduction

The compaction of DNA into dense structures plays an essential role in living systems. Because DNA is negatively charged, packaging it into high densities necessitates the screening of these charges. In eukaryotes, DNA is compacted in a hierarchical process involving histones, which wrap 1.67 turns (∼147 bp) of DNA around them. These DNA-protein complexes subsequently compact into the so-called 30-nm fiber, in a process that allows approximately two meters of DNA to be packaged into a nucleus 2 μm in diameter. Prokaryotes and viruses also contain compact DNA structures. Moreover, these organisms rely heavily on small, positively charged ions to screen or reduce electrostatic repulsions and induce attractions that lead to DNA condensation. Many double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) virions utilize a powerful molecular motor during assembly to pack DNA into a perforated capsid shell. The motor must do significant mechanical work against forces arising from DNA-bending rigidity, electrostatic self-repulsion, and entropy loss—forces that oppose DNA confinement. The relative contributions of each of these forces are not yet known. Measurements of DNA packing with optical tweezers in bacteriophages ϕ29, λ, and T4 show that all three motors can generate forces of ∼50 pN, which is 20 times higher than the forces generated by skeletal muscle myosin motors (1). In the assembly of a virus, molecular motors provide the driving forces required to package DNA to near-crystalline densities inside preassembled viral proheads. Even though viral packing motor proteins are capable of generating extraordinarily large forces, the packing of dsDNA inside viral capsids would not be possible without the presence of positively charged ions to reduce electrostatic repulsions (2).

The linear dimensions of viral capsids are typically tens of nanometers, whereas the length of the genome to be packaged is generally three-to-four orders-of-magnitude longer. The persistence length, —the length over which the tangent vectors to the contour of the chain remain correlated—is ∼50 nm under physiological conditions, the same order of magnitude as the linear dimensions of a typical viral capsid. The bending required of the genome as it is packaged within the capsid therefore leads to a buildup of energy that is large in comparison to the thermal energy or kBT. Additionally, the presence of phosphate groups leads to high linear charge density along the DNA backbone, which gives rise to large repulsive energy inside the densely packed capsid (3). Positively charged multivalent salt ions mediate an apparent attraction between negatively charged strands of DNA. Despite significant progress, the origin of internal pressurization of a viral capsid has not been fully characterized.

From a more general perspective, the apparent paradox between the molecular rigidity of nucleic acids and their compaction into a highly confined space could have implications for materials science and nanotechnology. As such, DNA condensation has received attention from the polymer physics community due to the complex interplay of bending, Coulombic, and hydration forces (4). In solution, DNA condensation leads to toroidal structures (5). Recently, DNA condensation has also been implicated as the source of heterogeneous, nonequilibrium dynamics observed in single molecule viral packing experiments (6, 7). Experimental studies have examined the effect of attractive versus repulsive DNA-DNA interactions on viral DNA packing dynamics in bacteriophage ϕ29, where a 19.3 kbp genome (6.6 μm) is translocated into a 54 × 42 nm prohead (6). Optical tweezers were used to directly measure DNA packing of a single DNA molecule into a ϕ29 prohead in real time. It was found that attractive interactions are induced by including spermidine3+ (Spe3+) in the buffer; when strong condensing agents such as spermidine are present, confinement leads to kinetically trapped intermediate states whose details remain unknown.

Computational and theoretical studies of confined DNA have played an important role in elucidating compaction. A commonly used coarse-grain (CG) representation for DNA packing simulations relies on bead-spring models in which a single interaction site represents a number of bases (8, 9, 10, 11). This representation assumes that DNA always remains double-stranded and that sequence is irrelevant. The results of simulations at such a level of representation have led to conformations that are consistent with cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) images and internal pressure measurements (12). Predictions have shown that packing occurs with DNA first forming a layer about the inner wall of the capsid, with subsequent rings stacking in a manner that tends toward the principal axis of the capsid (12). Simulations have revealed the importance of Brownian forces on the dynamics of the viral packing process, especially when the packing motor included transient pauses, of variable duration (3). A model that accounts for the fact that the packing motor may not catch, or may lose, the DNA backbone due to thermal fluctuations has also been proposed (8). It has been shown that rotation of the dsDNA by the packing motor is a necessary component for the formation of spoollike structures inside the capsid (9). The effect of capsid size and shape on the structure and thermodynamics associated with viral genome encapsidation have also been considered using simulations (10, 11). Results indicate that DNA both packs and ejects more easily from a spherical than from an ellipsoidal capsid (10) and that the size and shape of the capsid influence the configuration adopted by the packaged DNA (11).

Several simulation studies of viral genome encapsidation have incorporated attractive DNA-DNA interactions to model the effect of positively charged ions on the packing process. Forrey and Muthukumar (3) predicted increased DNA ordering and structures resembling folded toroids in the presence of attractive potentials between DNA sites. Petrov and Harvey (11) also predicted sharply reduced packing forces with attractive interactions and toroidal conformations with a central void. However, studies with attractive DNA-DNA interactions led to more ordered structures and lower forces than those observed experimentally. A likely explanation is that the corresponding simulations considered equilibrated DNA conformations. The forces resisting packing may be higher than the calculated statistical thermodynamic force due to dynamic dissipative effects. Perhaps more importantly, past simulations of viral genome encapsidation have not included the explicit treatment of ionic species, thereby neglecting an important kinetic energy contribution to the capsid’s internal pressure. The effect of ions on viral genome encapsidation has been investigated using density functional theory to treat electrostatic interactions with multivalent ions (13). Despite neglecting the bending stiffness of dsDNA, that theoretical treatment was capable of reproducing osmotic pressure data observed in experiments, highlighting the importance of electrostatic interactions relative to mechanical properties of dsDNA in driving the increase in capsid pressure during packing.

The above summary of the literature serves to show that, when taken together, simulations have led to a more complete picture of the interior dynamics of viral packing, but important questions remain, particularly in regard to the role of ions and stochastic forces (3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16). Such questions cannot currently be answered with atomistic simulations and, as pointed out earlier, previous studies have therefore represented dsDNA using a simple bead-spring chain with elastic properties and attractive interactions informed by experimental measurements. Prior simulations may have been limited by that coarse representation of DNA and the mean-field treatment of electrostatics; simulations using a more detailed representation of DNA and ions are needed.

In this article, the packing of dsDNA inside nanometer-sized capsids is described using a detailed DNA model that has nucleotide-level resolution and an explicit representation of ions. With such a model, it is not currently possible to simulate a full-size T7 or ϕ29 capsid. Therefore, instead of seeking to reproduce experiments performed on T7 or ϕ29 bacteriophages, we consider smaller systems and examine the effects of ions on the dynamics of packing inside nanometer-sized capsids. We do note, however, that there is a real system in nature that exhibits some resemblance with that considered here. In the purple nonsulfur bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus, DNA transmission is mediated by a 30 nm-diameter bacteriophage-like particle, the so-called gene transfer agent (GTA), which transfers random 4.5-kbp segments of the producing cells genome to recipient cells (17). The biological function of GTAs has been studied extensively (18), but the mechanisms by which random 4500-bp dsDNA segments are packaged inside 30 nm-diameter capsids remain largely unexplored. However, the terminase protein of R. capsulatus GTA shows homology with known sequence-independent enzymes from phages in the T4-like group. Phage T4 is a well-characterized example of a phage that uses a nonsequence-specific headful packaging mechanism (19). The limited, but recognizable, sequence homology between these terminases indicates a distant evolutionary connection between the R. capsulatus GTA packing mechanism and the protein gp17, which is the key component of the T4 phage DNA packaging motor (20). This article is organized as follows: in Materials and Methods, we describe the models and methods used to perform the viral genome packing simulations; in Results and Discussion, the results of the viral encapsidation simulations are presented and their significance is discussed; and lastly, some conclusions are drawn and the results presented here are compared to previous experimental and theoretical studies of viral genome encapsidation.

Materials and Methods

To describe DNA, we rely on the 3SPN.2C model (21, 22, 23). Three sites are used to represent each nucleotide, located at the phosphate, the sugar, and the base, respectively. The model correctly captures several aspects of DNA physics relevant to DNA encapsidation. First, 3SPN.2C can naturally describe both single- and double-stranded DNA. Second, it incorporates sequence-dependent shape and mechanical properties. Third, it has been shown to describe key aspects of DNA compaction in the context of DNA-histone complex formation (24, 25).

In 3SPN2, electrostatic interactions were originally described at the Debye-Hückel level. Recently, a general CG model for ions was introduced that can be applied to existing coarse-grained DNA models that lack explicit ions (26). That model has been validated by examining the local distribution of ions in the vicinity of the 3SPN.2 model. It predicts a dependence of the persistence length of dsDNA on monovalent ionic strength that is consistent with experiments for ionic strengths larger than 10 mM. Importantly, the explicit-ion model includes CG parameters for modeling spermidine3+, thereby enabling simulations of dsDNA condensation.

The coarse-grained ions model can, in principle, be used with any coarse-grained DNA model that resolves the excluded volume of dsDNA and carry charges at the location of phosphates. The model includes sodium (Na+), magnesium (Mg2+), spermidine (Spe3+; NH+3-(CH2)4− NH+2-(CH2)3-NH+3), and chlorine (Cl−) ions. The main assumptions of the ions model used here are that 1) the local ionic environment around dsDNA is determined by interactions between the ions and the phosphates groups along the DNA backbone and the excluded volume created by the bases and sugar sites; and 2) the phosphate-ion interactions can be obtained by performing simulations with a surrogate small molecule, instead of simulating a complete DNA oligomer. Optimization of the CG parameters of the ion-ion effective potentials was performed using relative entropy coarse-graining (27), which provides a systematic approach to obtaining effective potentials for use in CG simulations, given a mapping function from all-atom to CG coordinates (26). The CG nonbonded effective potentials between ions are represented as the sum of a Coulombic interaction and a correction term, Ucorr, as follows:

| (1) |

where qi and qj are the charges of the and jth ion, ϵ0 is the dielectric permittivity of vacuum, ϵ(T) is the solution dielectric, and rij is the intersite separation. Ucorr is represented using cubic splines. Ucorr corrects the Coulombic potential to account for the effects of hydration and steric overlap. The use of cubic splines permits the reproduction of subtle effects that could not be easily resolved with analytical expressions. The effective potentials reproduce essentially all features of the radial distribution functions from all-atom simulations. Additional details and parameters for the ions model used here are given in Hinckley and de Pablo (26).

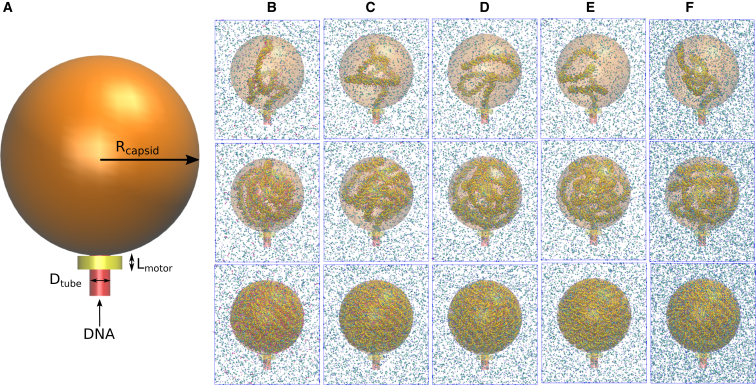

In this work, the viral capsid was modeled as a sphere with a radius, Rcapsid, of 12.5 nm (a schematic representation of which is shown in orange in Fig. 1 A). The cylinder (shown in red in Fig. 1), through which the dsDNA enters the capsid, was assigned a diameter, Dtube, of 2.8 nm, only slightly larger than the diameter of the double helix (∼2 nm). The use of the cylinder implicitly assumes that the structure of the packaged dsDNA is not affected by the structure of unpacked dsDNA external to the capsid. The sphere and cylinder act as a wall confining the DNA; as DNA sites approach the wall, they experience a repulsive Weeks-Chandler-Anderson potential (28),

| (2) |

where r is the distance perpendicular to the interior of the capsid; ϵ = 1.68 kBT; σ = 0.2 nm; and there is a cutoff of 21/6σ. This combined sphere-cylinder geometry displays convex edges at the intersection of the sphere and cylinder; therefore, to prevent dsDNA sites from escaping at these edges, a ring of beads was placed at the edge location. These beads exert repulsive forces equivalent to those described in Eq. 2. The ring of beads, like the capsid, also exert repulsive Weeks-Chandler-Anderson forces only on DNA sites. Ions are free to diffuse through the walls of the capsid as they do in real capsids. The packing motor (shown in yellow in Fig. 1 A) was represented by a region perpendicular to the cylinder and adjacent to the sphere with a length Lmotor = 1.7 nm. Within this feeding tube region, each dsDNA site experiences either a 2.5 or a 5.0 pN force in the +z direction, which results in a total force of 75 or 150 pN exerted on the DNA segment inside the motor tube by the molecular motor. Only the results for 75 pN total packing force are presented in the main article; the 150 pN results are included in the Supporting Material.

Figure 1.

Viral capsid model and snapshots of packing simulations. (A) Model for the spherical capsid shell (Rcapsid = 12.5 nm) to which the dsDNA is packaged. A motor protein applies a constant force (either 75 or 150 pN) to the DNA segment inside the yellow cylinder (Lmotor = 1.7 nm). There is a 5-nm padding around the capsid. The red tube of diameter Dtube = 2.8 nm is used to constrain the DNA when outside of the capsid. (B)–(F) Representative snapshots of the viral DNA encapsidation simulations with the 3SPN.2C model with explicit ions. (Blue spheres) Na+ ions; (red spheres) Mg2+ ions; (cyan spheres) Cl− ions; (magenta spheres) Sp3+. (First row) 320 bp packaged. (Second row) 1020 bp packaged. (Third row) 3020 bp packaged. (B) System with high spermidine3+ content; (C) system with low spermidine3+ content; (D) system with lowest spermidine3+ content; (E) system with no spermidine3+ but with Mg2+; (F) system with Na+ and Cl− only. To see this figure in color, go online.

The packing of dsDNA into the capsid was performed as follows: a random 4000-bp sequence of DNA was generated with 50% CG content. The first 20 bp of this DNA sequence were placed at the entrance to the capsid. To facilitate addition of the rest of the DNA later in the simulation, the bases at the end of the dsDNA opposite the capsid entrance were subject to several constraints. First, the x and y positions of sugar sites of the terminal nucleotides were held at their original values with stiff (16.8 × 103 kBT/nm2) springs. Second, the last two base steps were modeled as a rigid body to prevent fraying. DNA packing simulations were performed until the bases modeled as a rigid body entered the motor region. At that time, an additional 10 bp of DNA were appended to the dsDNA, with the terminal bases again modeled as a rigid body. After these new 10 bp of DNA entered the motor region another 10 bp were appended, and the procedure was repeated until the average packing velocity became zero. The appropriate number of counterions were added to the exterior of the capsid to maintain charge neutrality of the simulation box.

In this work, four levels of spermidine content in the simulation box were considered. In the high spermidine case (HighSpe), six Spe3+ and two Na+ were added in each packing step. To model moderate spermidine contents (LowSpe), 2 Spe3+, 2 Mg2+, and 10 Na+ were added in each packing step. For the lowest spermidine concentration (LowestSpe), 1 Spe3+, 2 Mg2+, and 13 Na+ were added. Additionally, two systems without spermidine were considered: One in which 5 Mg2+ and 10 Na+ (NoSpe) were added at each packing step. For all the systems above, the simulation box was initialized with a concentration of 50 mM of NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2. Another system was initialized with 100 mM NaCl, and only Na+ and Cl− were added as counterions at each packing step (Salt). To eliminate any steric overlap between the added counterions and the appended DNA sites, the energy was minimized by iteratively adjusting atom coordinates at the beginning of each packing step.

The viral encapsidation simulations were performed with the molecular dynamics simulator LAMMPS (29) in the NVT ensemble using the Gronbench-Jensen Farago Langevin thermostat (30, 31), with a damping factor of τm = 500 fs. The friction coefficient of site i, ζi, is related to the damping factor τm by , where mi is the molecular mass of site i. A time step of 10 fs and a temperature of 300 K were used in all simulations. Simulations with explicit ions used the particle-mesh Ewald solver to calculate the electrostatic interactions with a real space cutoff of 1.2 nm.

Note that, in experiments, the capsid is exposed to a reservoir containing large amounts of ions that diffuse into the capsid to neutralize the DNA. In the simulations presented here, ions are introduced into the simulation box as counterions, to preserve neutrality, without rigorously accounting for the thermodynamic equilibrium that should exist between the ions in the simulation box and an external reservoir. With the procedure adopted here, the bulk concentrations of ions in the simulation box do not remain constant through the packing process. The bulk concentration of ions increases as counterions are added to keep the simulation box neutral as more DNA is packaged. However, to facilitate comparison with experiments, the concentration of each ionic species achieved at the end of the packing simulations for the different ionic environments considered here are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentrations of Ionic Species in the Simulation Box and in the Bulk, Outside the Capsid, at the End of the Packing Simulations for the Different Ionic Environments Considered in this Work

| HighSpe (mM) | LowSpe | LowestSpe | NoSpe | Salt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | Cbox | 75.5 | 165.8 | 195.3 | 163.1 | 304.6 |

| Cbulk | 62.6 | 87.7 | 90.6 | 83.4 | 142.0 | |

| Cl− | Cbox | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 |

| Cbulk | 71.1 | 71.6 | 71.5 | 71.4 | 119.4 | |

| Mg2+ | Cbox | 5.0 | 30.0 | 27.1 | 61.0 | 0.0 |

| Cbulk | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 0.0 | |

| Spe3+ | Cbox | 218.4 | 68.7 | 33.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cbulk | 19.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Results and Discussion

Packing dynamics

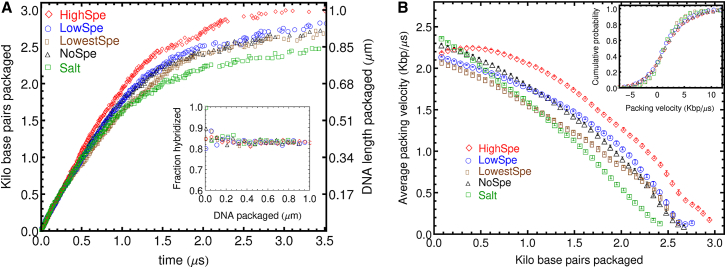

The effect of increased Spe+3 concentration on the dynamics of viral DNA packing inside the capsid is considered first. Fig. 2 A shows the number of DNA basepairs packaged as a function of time for a packing motor force of 75 pN. The average packing velocity versus the number of basepairs packaged is presented in Fig. 2 B. Additionally, the number of DNA basepairs packaged as a function of time and the packing velocity for a packing motor force of 150 pN is given in Fig. S1. The packing proceeds approximately two times faster for the larger packing force. Moreover, the curves of DNA packaged versus time for the lower packing force appear to reach a plateau (stall) before 1 μm has been packaged. For the higher packing force, stalling only occurs after >1 μm of DNA has been packaged. This can also be observed in the packing velocity plots, where the packing velocity decays to zero before 3 kbp are packaged for the 75 pN motor force, while it stays larger than zero for values >3 kbp for the systems with 150 pN. For the systems with the highest spermidine content and the lower packing force, the maximum amount of DNA packaged before stalling occurs is 3 kbp, corresponding to 1 μm of DNA and a volume fraction of DNA inside the capsid of 0.26. On the other hand, for the 150 pN force, the highest amount of DNA packaged before the onset of stalling is ∼3.5 kbp, which corresponds to a volume fraction of DNA inside the capsid of 0.30.

Figure 2.

(A) Number of basepairs (or DNA length) packaged as a function of time for different ionic environments. (Inset) Fraction of DNA inside the capsid that is hybridized as a function of DNA length packaged. (B) Average DNA packing velocity versus number of basepairs packaged inside the viral capsid. Error bars are standard errors of the mean. (Inset) Cumulative probability distributions for the packing velocities. To see this figure in color, go online.

In general, the packing velocity decreases as the amount of DNA packaged increases. At the initial stages of packing for the systems with multivalent cations, the packing velocity curves exhibit a region where there is significantly less deceleration than in the system with only Na+ and Cl− ions. The packing velocity starts to decrease rapidly when ∼500 bp have been packaged. In the system with highest content of spermidine there is a region, at the beginning of the packing process, at which the packing velocity increases slightly and then remains constant for a brief period of time. On the other hand, in the system with only Na+, the packing velocity decreases with the number of basepairs packaged right from the beginning of the packing process.

Fig. 2 shows that the system where only salt is added exhibits a significantly lower packing velocity and a lower total amount of DNA packaged before stalling. The system with salt and magnesium ions as well as the two systems with lower spermidine content show very similar packing dynamics. Moreover, the systems with Mg2+ and low Spe3+ content exhibit a larger packing velocity as well as a larger amount of total DNA packaged than the system with salt only. Furthermore, the system with the highest proportion of spermidine ions exhibits an even larger packing velocity and significantly larger amount of DNA encapsidated before packing stalls than all the other systems considered.

The effect of divalent and trivalent cations, magnesium, and spermidine, respectively, on the packing dynamics appears to be highly dependent on the magnitude of the packing motor force. For instance, the 75 pN packing force demonstrates significant differences between the packing velocities of the system with salt only relative to the systems with multivalent cations (Spe3+, Mg2+). On the other hand, in systems with the 150 pN packing force, only the system with high concentration of spermidine shows a significantly larger packing velocity. However, for both motor forces, the effect of the different ionic environments on the packing velocity only becomes apparent at times larger than μs after the start of the packing process.

The inset in Fig. 2 A show that the fraction of basepairs hybridized remains stable, fluctuating at ∼0.85 during the entire duration of the packing process. This level of hybridization is the same as that observed in an unconfined random 150-bp sequence of DNA with 50% CG content in ionic environments with the same bulk concentrations of ions that are achieved at the end of the packing simulations (see Fig. S6 A). The fraction of hybridized basepairs is determined by the melting temperature of dsDNA which, in turn, depends on the balance among attractive Watson-Crick basepairing, entropy, and electrostatic repulsion between ssDNA molecules. These results indicate that the dsDNA hybridization is not significantly affected by the highly crowded conditions of the capsid shell.

Note that the average packing velocities observed in the simulations reach up to 2.5 × 109 bp/s. This is ∼107 times larger than the average packing velocities observed in ϕ29, which reach up to ∼150 bp/s and ∼106 times larger than packing velocities observed in phage T4, which reach up to ∼2000 bp/s (32, 33). In the simulations presented here, packing 1 μm of DNA inside a 12.5 nm radius capsid occurs in ∼3.5 μs. In viral packing experiments in phage ϕ29, for example, packing a 6-μm genome inside a 42 × 54 nm capsid takes ∼400 s (32, 33). One possible explanation for this mismatch of several orders of magnitude between the simulation packing velocity and the experimental packing velocity is the very simplified packing motor model used in the simulations. In actuality, packing motors in phages such as ϕ29 are regulated by a sensor that detects the density and conformation of the DNA packaged inside the viral capsid, and slows the motor by a mechanism distinct from the effect of a direct load force on the motor. Specifically, the motor-ATP interactions are regulated by a signal that is propagated allosterically from inside the viral shell to the motor mounted on the outside (34). This signal continuously regulates both the motor speed and the duration of pauses in response to changes in either density or conformation of the packaged DNA, and slows the motor before the buildup of a large capsid internal pressure that resists additional DNA confinement (34). Recent experimental studies of DNA packaging in bacteriophages suggest that transport processes of ionic species and DNA relaxation, which occur at timescales that can be as long as 10 min, even in purely repulsive conditions, dominate experimental observations (6, 7, 33). Given the much higher packing velocities that occur in the simulations, these slower processes will not have an observable effect on the viral packing simulations presented here.

While the main panel in Fig. 2 B shows the average packing velocity, the inset shows the cumulative probability distribution of velocities. In these distributions, it can be observed that the systems that contain spermidine or magnesium ions have a slightly broader distribution of velocities compared to the system with only salt. Note that these differences disappear in the simulations done at higher packing motor force (Fig. S1 B). Although at a very smaller scale than is observed experimentally (6, 33), this would indicate that in the simulations the multivalent cations are also increasing the heterogeneity of the packing dynamics. Moreover, the results presented here indicate that the degree to which these cations can increase the heterogeneity of the packing dynamics is highly dependent on the average packing velocity. At the higher packing velocities corresponding to the 150 pN packing force, the small effect of the multivalent cations on the heterogeneity of the packing dynamics that is observed at 75 pN disappears.

In the next subsections, the conformations and energies of the packaged DNA as well as the pressure inside the capsid as a function of basepairs packaged are analyzed in detail.

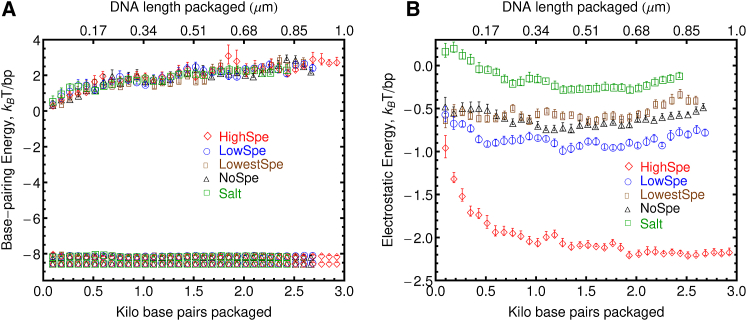

DNA energy during packing

The detailed DNA model used here allows us to examine the effects of the packing process and ionic environment on the structure of the DNA double helix. Fig. 3 A shows the energy that arises from bonded potentials of the packaged DNA as a function of the total basepairs packaged. The bonded energy of DNA includes bond, bend, and dihedral contributions (23). The average bond energy per bp, as well as the maximum value observed for this energy in the packaged DNA molecule, are shown. No significant differences are observed for this energy in the different ionic environments considered here. The average bonded energy of the packaged DNA remains practically constant at ∼7 kBT/bp through the entire packing process. These mean bonded energies are ∼1.5 kBT/bp larger than the mean bonded energies that are observed in an unconfined random 150 bp sequence of DNA with 50% CG content in ionic environments with the same bulk concentrations of ions that are achieved at the end of the packing simulations (see Fig. S5 A). On the other hand, the maximum value of the bonded energy in the packaged DNA grows with the number of basepairs packaged. It begins with a value of ∼8 kBT/bp in the initial stages of packing and reaches a value of ∼14 kBT/bp at the point when packing stalls. These maximum bonded energies observed by the end of the packing simulations are two times larger than the maximum bonded energies that are observed in an unconfined 150-bp sequence of DNA in ionic environments with the same bulk concentrations of ions that are achieved at the end of the packing simulations (see Fig. S5 D).

Figure 3.

Bonded energy of DNA during the packing process for different ionic environments considered here. (A) The mean bonded energy (bond + bend + dihedral) per basepair, as well as the maximum values of this energy, for a given number of basepairs encapsidated. (B) Distribution of bend angles in the helical axis of DNA at the point when packing stalls for different ionic environments. Error bars are standard errors of the mean. To see this figure in color, go online.

The probability distributions of bend angles within the helical axis of the DNA molecule at the end of the packing process for the different ionic environments considered here are shown in Fig. 3 B. To calculate these distributions, each complementary basepair is reduced to its center-of-mass position. Snapshots of the helical axis during the packing process are shown in Fig. S3. In agreement with what is observed in the bonded energies, there is not a significant effect of the ionic environment on the distribution of bend angles of the packaged DNA. On the other hand, and as expected for a dsDNA molecule packaged in a nanometer-size capsid, these distributions of bend angles for the packaged DNA do have a broader tail in the 130–50° compared to the distributions of bend angles in an unconfined 150 bp sequence of DNA with 50% CG content (see Fig. S5 B).

Fig. 4 A shows the basepairing interactions between base sites in the packaged DNA as a function of basepairs packaged. Here again, the average basepairing energy per basepairs, as well as the maximum and minimum values observed for this energy along the packaged DNA molecule, are shown. The average basepairing energy remains attractive and practically constant at −8 kBT/bp during the entire packing process. Again, no significant differences can be detected in the basepairing energy between different ionic environments. Moreover, the constant mean basepairing energy also confirms that on average the DNA double helix remains stable during the entire packaging process for all the ionic environments considered here. In other words, the average fraction of dsDNA that remains hybridized inside the capsid is not significantly affected when the amount of divalent or trivalent cations is increased. This is consistent with the fairly stable fraction of basepairs hybridized during packing that is observed in the insets of Fig. 2 A. Moreover, the mean basepairing energies observed in the packing simulations are very similar to the mean basepairing energies observed in an unconfined 150 bp sequence of DNA in ionic environments with the same bulk concentrations of ions that are achieved at the end of the packing simulations (see Fig. S6 B).

Figure 4.

Basepairing and electrostatic energies of DNA during the packing process for different ionic environments considered here. (A) The figure shows the average basepairing energy per basepair, as well as the maximum (most attractive) and minimum (most repulsive) values of this energy. (B) Net electrostatic energy of the DNA per basepair as a function of the length of DNA packaged inside the capsid. To see this figure in color, go online.

Even though on average the DNA double helix appears to remain unaffected by the packing process, there can be regions of the packaged DNA molecule where a larger disturbance may occur, and this might not be discernible by the average basepairing energy. To investigate if subtle changes in the double-helical structure of DNA are occurring during packing, the maximum and minimum basepairing energies along the DNA double helix were calculated. A maximum attractive basepairing energy of −8.1 kBT/bp is observed during the entire packing process. The minimum basepairing energy along the packed DNA molecule is actually repulsive and grows from 0 kBT/bp at the beginning of the packing process, to ∼3 kBT/bp at the end of the packing process. This repulsive basepairing energy originates from locations along the DNA double helix where the bases involved in a basepair come too close together due to an effective attraction between complementary strands of DNA. An unconfined 150 bp sequence of DNA in ionic environments with the same bulk concentrations of ions that are achieved at the end of the packing simulations (see Fig. S6 D) also show slightly repulsive basepairing energies. However, in the unconfined cases, these repulsive energies stay at ∼0.5 kBT/bp on average. In both the confined and unconfined scenarios, no significant differences in these repulsive basepairing energies are observed between the DNA in the different ionic environments considered. The repulsive basepairing energies observed in the simulations appear consistent with experimental observations in Raman spectra that show that changes in the DNA double helix during viral packing are not associated with either base unpairing or intrastrand separation, but instead with a small net change in DNA groove dimensions, interpreted as a net narrowing of the minor groove of the DNA (35, 36).

Fig. 4 B shows the average electrostatic energy of the DNA molecule during packing, which arises from the electrostatic interactions between phosphate sites on the DNA backbone among themselves, and from electrostatic interactions between phosphate sites and the ionic sites in the system. Significant differences can be observed in the electrostatic energy of the packaged DNA for the ionic environments considered here. For the system with the highest content of spermidine, the electrostatic energy is attractive at −1 kBT/bp from the onset of the packing process and becomes exponentially more attractive as more DNA length is packaged, reaching a value of −2.3 kBT/bp when packing stalls. The DNA in the system with low content of spermidine shows an attractive electrostatic energy that varies between −0.5 kBT/bp and −1.0 kBT/bp during the course of the packing process. The DNA in the system with the lowest content of spermidine and in the system with magnesium but no spermidine shows indistinguishable electrostatic energy which fluctuates at ∼−0.5 kBT/bp. In the system where only sodium chloride is added, the DNA shows slightly repulsive electrostatic energy (0.2 kBT/bp) at the beginning of the packing process, but as more DNA and ions are added in the simulation box, the repulsion between DNA phosphate sites is screened and the electrostatic energy fluctuates slightly below zero during the remainder of the packing process. Note also the relation between the increase in the effective attraction between phosphate sites in the DNA backbone and the increase in the repulsive character of the basepairing interactions. Regions of the packaged DNA where the complementary strands feel a strong effective attraction show a more repulsive basepairing energy.

In experiments, DNA–DNA self-interactions that, when averaged over the whole DNA length, are net-repulsive, are obtained with a standard packaging buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM ATP (6, 33). In this work, the systems where only NaCl is added achieve a concentration 142 mM Na+ at the end of the packaging process, a value considerably higher than in experiments. With this concentration of NaCl, a net screening of the DNA–DNA repulsions is observed during most of the packing process, as shown in Fig. 4. There is a short period when <0.1 μm of the DNA has been packaged, when net-repulsive DNA–DNA interactions are observed. In this work, none of the ionic environments considered produce net-repulsive DNA–DNA self-interactions throughout the packing process. In experiments, “low spermidine” concentrations are achieved by adding 0.8 mM spermidine (6, 33). The system labeled “LowSpe” in this work achieves a concentration of 0.7 mM of Spe3+, which is very similar to the experimental spermidine concentrations usually labeled as “low spermidine”. Here, net screening and on-average slightly attractive DNA–DNA self-interactions are observed for these low Spe3+ concentrations. In experiments, high-spermidine concentrations that cause DNA–DNA interactions to become attractive are achieved by adding 5 mM spermidine (6, 33). Spermidine concentrations of ∼10 mM have been reported in host cells (37). The highest spermidine concentrations achieved here by the end of the packing process in the HighSpe system are well above those values at 19 mM.

The energetics of the packaged DNA shed some light on the mechanisms by which a larger amount of DNA can be packaged in the systems with highest spermidine content. The attractive electrostatic interactions between phosphate sites induced by the high concentration of spermidine ions could produce condensation of the packaged DNA. Some additional metrics will be considered in the next subsection to confirm if indeed the large attractive electrostatic energy causes such condensation. What appears clear, however, is that the integrity of the DNA double helix is not significantly affected by the large concentration of multivalent actions nor by the packing process itself. The packing process causes certain regions of the packaged DNA to become more bent while the effective attraction between phosphate sites induced by the cations pushes the basepairs in complementary strands closer together.

DNA conformation inside the capsid

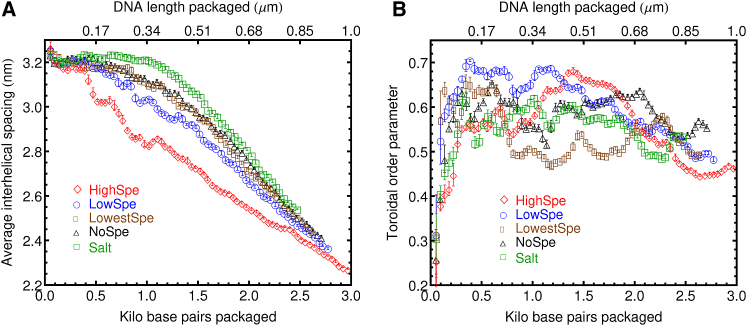

Fig. 1, B–F, shows representative snapshots of the packing simulations for the systems with different ionic environments considered in this work. To further quantify the structure of the packaged DNA, each complementary basepair is first reduced to its center-of-mass position rC,i. Fig. S3 shows representative snapshots of the helical axis during the packing of the simulations. By simple visual observation, it is hard to discern differences between systems with different ionic environments. To quantify the effect of the ionic environment on the structure of DNA inside the capsid, two commonly employed metrics were calculated— namely, the average interhelical spacing and the toroidal order parameter.

The average interhelical spacing, 〈hmin〉, as a function of basepairs packaged for the different ionic environments considered here, is shown in Fig. 5 A. The average interhelical spacing, also referred to as the “minimal mean distance” between adjacent DNA coil rings, is found by searching for all pair separations involving sites rC,i at least nine nucleotides apart (to exclude the effect of immediate neighbors),

| (3) |

where Nbp is the total number of basepairs packaged inside the capsid. As expected, 〈hmin〉 decreases with increasing amount of DNA packaged inside the capsid. The minimum values of 〈hmin〉, observed at the packing stall points, range from 2.4 to 2.1 nm and agree well with experimental measurements in mature bacteriophages using cryo-EM (15, 38), which find interhelical spacings of 2.4 nm, and x-ray diffraction measurements (39), which report interhelical spacings of 2.8 nm.

Figure 5.

(A) Average interhelical spacing for the dsDNA inside the capsid as a function of the number of basepairs encapsidated (Eq. 3), for different concentrations of spermidine considered here. (B) Toroidal order parameter for the dsDNA inside the capsid as a function of the number of basepairs encapsidated. This order parameter approaches unity for a perfect stack of hoops, whereas a group of random coils gives a value of 0.5. To see this figure in color, go online.

The average interhelical spacing shows the expected dependence on multivalent cation concentration. That is, for the systems with the highest spermidine content, the interhelical spacing decreases significantly faster with the number of basepairs packaged than the systems with lower or no content of spermidine. The system with only salt presents the largest interhelical spacings and the slowest decrease as a function of DNA length packaged inside the capsid. The systems with the lowest content of spermidine and the systems with no Spe3+ but with Mg2, present an almost indistinguishable behavior of 〈hmin〉 as a function of basepairs packaged inside the capsid. These observations confirm that both Mg2+ and Spe3+ induce DNA condensation inside the viral capsid. Moreover, there is an evident change in the overall behavior of 〈hmin〉 versus DNA packaged as the amount of multivalent cations is increased. For the systems with salt only, 〈hmin〉 shows a plateau at the beginning of the packing process, followed by a clear phase transition toward a condensed state at ∼1.5 kbp packaged. When Mg2+ is added, and as the amount of Spe3+ is increased, DNA condensation appears to occur very early during the packing process. This is consistent with the exponential increase in the attractive electrostatic energy as a function of basepairs that is observed in the system with highest spermidine concentration shown in Fig. 4 B.

Another metric commonly used to characterize the structure of DNA packaged inside confined geometries is the toroidal order parameter. This metric quantifies the degree to which the packaged DNA forms a toroidlike assembly of stacked hoops aligned with the packing axis. To calculate the toroidal order parameter, each complementary basepair is again reduced to its center-of-mass position rC,i and individual arcs of 15 consecutive basepairs along the chain are considered. A unit normal vector for each arc is defined by normalizing the cross product of the two vectors connecting the middle rC to each of the end rC of the individual arcs. The toroidal order parameter approaches unity for a perfect stack of hoops, whereas a group of random coils gives a value of 0.5. Fig. 5 B shows the toroidal order parameter for the systems considered here. After the first 500 bp have been packed, all the systems exhibit toroidal order parameters that fluctuate between 0.5 and 0.7. This indicates that the DNA packing proceeds with a very low degree of toroidal or stack-of-hoops organization. Moreover, no significant effect of the ionic environment over the toroidal order of the packaged DNA can be observed. For the larger packing force, 150 pN, a small overshoot in the toroidal parameter is observed, which is especially pronounced for the system with magnesium but without spermidine. It reaches a value as high as 0.8 at low densities of DNA inside the capsid. This could indicate a preference for packing in an assemblage of stacked hoops, at the beginning of the packing process, when the packing proceeds at faster velocities. However, this preference for packing with toroidal order cannot be maintained when the capsids become more crowded reducing the packing velocity. These results appear to agree with previous experimental and simulation results that have shown that in ϕ29, the packaged DNA does not fill the capsid in concentric hoops, but instead it undergoes a condensation of the whole genome as packing proceeds. This condensation results in local close-packed order, and the DNA adopts a layered architecture with concentric, closed, shells (15).

Forces resisting packing

In systems with explicit mobile ions such as the one considered here, the slope of the DNA energy as a function of DNA length packaged is not expected to give an accurate representation of the forces that the molecular motor must overcome to package the DNA inside the capsid. To determine such forces, it is therefore necessary to calculate the capsid internal pressure, P, which is the force per unit area exerted over the inner surface of the capsid shell by the DNA and ion molecules that are inside the capsid at any given time. To obtain the pressure, the atomic stress tensor, including virial and kinetic energy contributions, is calculated as

| (4) |

where mi is the mass of the ith site; rij is the vector connecting site i with site j; vi is the velocity of site i; U is the total potential energy; and N is the total number of DNA and ionic sites in the simulation box. The capsid internal pressure is then obtained by averaging the diagonal components of the atomic stress tensor over all the DNA and ionic sites found inside the capsid at any given time,

| (5) |

where n is the number of DNA and ionic sites inside the capsid and is the volume of the capsid.

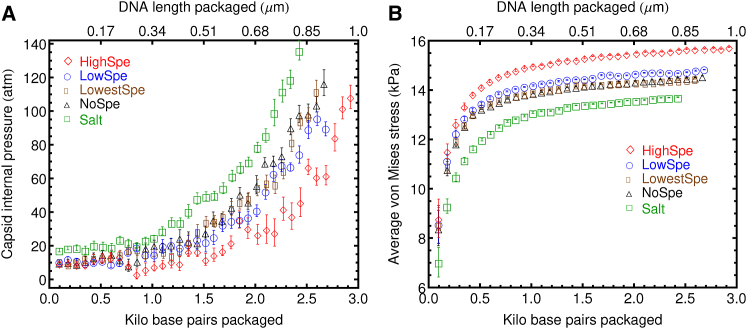

The capsid internal pressure as a function of basepairs packaged is shown in Fig. 6 A, for the five different ionic environments considered here. The pressure appears to remain constant between 10 and 20 atm during the early stages of packing. After ∼1 kbp of DNA have been packaged, the internal pressure starts to increase exponentially. This increase in the pressure is due to the crowded environment within the capsid, and indicative of the high forces necessary to fully package the viral genome. Pressures as high as 140 atm are observed for the system with only salt. Experimental osmotic pressure measurements (40, 41) have found capsid internal pressures of ∼20 atm in λ-phages with 13-kbp packaged genomes. When spermidine was added to the solution buffer, the capsid internal pressure observed for a fully packaged genome was reduced to 5 atm (40). The sevenfold larger pressures observed in the simulations compared to experimental situations could be due to the much higher packing velocities, which significantly reduce the time available for stress relaxation to occur in the packaged DNA.

Figure 6.

(A) Pressure inside the capsid as a function of the number of basepairs (or DNA length) encapsidated for different ionic environments in the simulation box. A significant increase in internal pressure during the latter stages of packing is due to the crowded environment within the capsid, and indicative of high forces necessary to fully package the viral genome. (B) Average von Mises stress in the capsid as a function of basepairs encapsidated (or DNA contour length) for different ionic environments in the simulation box. To see this figure in color, go online.

The effect of changes in the ionic environment on the capsid internal pressure appear consistent with the packing velocity curves presented in Fig. 2 B. The lowest capsid internal pressure as well as the lowest rate of growth of internal pressure with DNA length packaged is observed in the system with the highest content of spermidine, which also exhibits the highest packing velocity and highest amount of DNA packaged. The two systems with lower content of spermidine and the system with magnesium but no spermidine all have indistinguishable capsid internal pressures as a function of the number of basepairs packaged and also exhibit very similar packing velocities. The system with only salt presents the highest capsid internal pressures and also the highest rate of growth of internal pressure with DNA length packaged. These results are all consistent with the notion that for a constant packing motor force a lower capsid internal pressure will provide less resistance to the packing motor and therefore packing will occur faster and increase to a higher DNA density.

To further explore the stress of the molecules inside the capsid, a common invariant of the stress tensor, namely the von Mises stress, was also calculated. In contrast to the pressure, this stress invariant contains contributions from the off-diagonal components of the atomic stress tensor (shear stresses). In terms of the Cartesian components of the atomic stress tensor, the von Mises stress can be written as

| (6) |

The von Mises stress, averaged over all the DNA and ion sites inside the capsid, is shown as a function of DNA length packaged in Fig. 6 B. In contrast to what happens with the pressure, the von Mises stress grows rapidly at the beginning of the packing process and then plateaus toward the end of it, in a behavior that seems to follow the maximum bonded energy of the packaged DNA shown in Fig. 3 A. This shows that the increase in pressure and the increase in von Mises stress arise from very different underlying molecular processes. While the pressure is affected to a large extent by the concentration of ions inside the capsid, the von Mises stress is mostly determined by the conformation adopted by the packaged DNA. The system with highest spermidine content shows a significantly larger von Mises stress, which is consistent with the more condensed DNA structure inside the capsid. The systems with the two lower levels of spermidine content as well as the system with Mg2+ exhibit indistinguishable von Mises stresses. The system with salt only shows even lower von Mises stresses, which again is in agreement with the fact that magnesium ions and the lower contents of spermidine are still able to induce more DNA condensation in comparison to the Na+ ions alone.

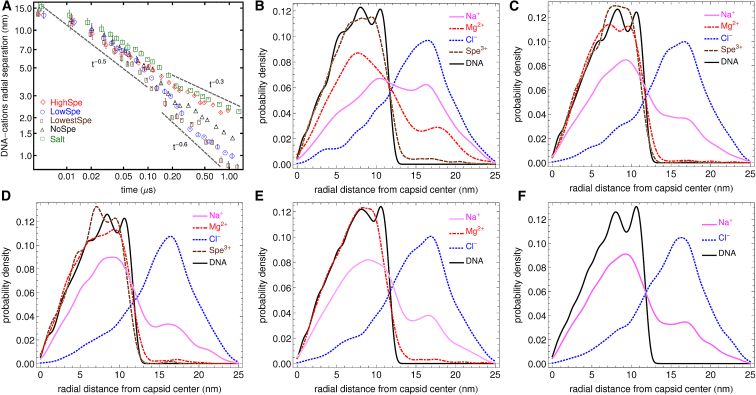

Distribution of ionic species during packing

An important advantage of the model used here to investigate the dynamics of viral DNA encapsidation over previous approaches is that it can track the localization of individual ionic species during the genome packing process. This can provide insight into how the transport of ions inside the highly crowded environment of the capsid affects the overall dynamics of the encapsidation process. Before DNA condensation can commence, the multivalent cations present in the buffer solution have to reach the negatively charged phosphate sites on the DNA backbone. To quantify the dynamics by which cations reach these phosphate sites, we calculate the radial distance (RD) between cation sites and DNA phosphate sites, according to

| (7) |

where is the radial distance from the capsid center; and indicates an average over all the sites of a given type in the simulation box at time t, namely cations (cat), which include Na+, Mg2+, and Spe3+ sites, and phosphate sites (phos). Lower values of RD indicate higher cation localization while larger values indicate a smaller degree of cation localization relative to the packaged DNA phosphate sites.

Fig. 7 A shows the relative radial distance (or separation) between cations and DNA phosphate sites for the systems considered here. The systems with lower content of spermidine exhibit the fastest and highest relative localization of cations, while the systems with highest content of spermidine and the systems with only salt show the slowest and lower localization of cations close to phosphate sites. Moreover, the cation RD metric as a function of packing time exhibits power-law behavior, with at least two distinguishable regions for each ionic environment. A first region at short times, , is one in which the RD for all the systems considered behaves as RD ∼ t−0.5. Then, for in the system with highest spermidine content and the system with salt only, the RD decays as ∼ t−0.3. In contrast, in the systems with lower spermidine content and the system with Mg2+ but no spermidine, the RD behaves as ∼ t−0.6. The slower and lower localization of cations observed in the system with the highest spermidine content is probably related to the fact that Spe3+ molecules are larger than the other ions and therefore have lower mobilities, which will have a larger effect as the capsid becomes increasingly crowded. In the system with salt only, the cation localization also occurs relatively slowly and to a lower degree. In this case, the behavior can be explained by the lower affinity of Na+ toward the phosphate sites on the DNA, compared to the affinity of the multivalent cations. Note that even though the system with salt only and the system with the highest content of spermidine have practically the same dynamics and level of cation localization, the latter produces much higher levels of DNA condensation than the former. On the other hand, the systems with lower amounts of spermidine, which also contain Mg2+, present the highest and fastest levels of relative cation localization. In these systems, the lower concentrations of the bulky spermidine ions produce a less crowded environment inside the capsid. Moreover, the magnesium ions also have a large affinity toward the phosphate sites on the DNA, and are also smaller and more mobile than Spe3+.

Figure 7.

(A) Relative radial distance between the packaged DNA phosphate sites and cations (Spe3+, Mg2+, and Na+) as a function of packing time (see Eq. 7). Lower values of this relative squared separation indicate higher cation localization while larger values indicate a smaller degree of cation localization relative to the packaged DNA phosphate sites. (B)–(F) Radial probability distributions for the ions and DNA in the simulation box at the time when packing stalls. (B) System with the highest content of spermidine; (C) system with low content of spermidine; (D) system with the lowest content of spermidine; (E) system with no spermidine; (F) system with only salt. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. S2 shows the RD for the simulations with 150 pN packing motor force. It can be observed that in the early stages of packing (before 500 bp are packaged), the rate of decay of the RD is significantly faster, RD ∼ t−0.5, for the systems with lower packing motor force than for the systems with higher packing motor force, RD ∼ t−0.35. This indicates that at a lower packing velocity there is more time available for cations to diffuse toward the capsid and reach phosphate sites in the packaged DNA during the early stages of packing. Later during the packing process, the systems with the higher packing motor forces exhibit faster cation localization. For instance, for 150 pN in the system with the highest spermidine content and the system with salt only, RD ∼ t−0.7 is exhibited, and the other systems with lower contents of spermidine and magnesium only show RD ∼ t−0.9. Note that in the system with lower packing motor force, cation localization slows down as more DNA is packaged, while for the systems with larger motor force, cation localization accelerates as the amount of DNA inside the capsid increases. This shows that the dynamics of the localization of cations close to the packaged DNA is highly dependent on the average packing velocity.

The RD metric only provides information about the first moment of the probability distributions of ionic localizations. Fig. 7, B–F, shows the complete probability density distributions of the radial positions of DNA and all ions in the simulation box at the time where packing stalls. The high affinity of Mg2+ and Spe3+ toward DNA is evident in all the systems that contain these two types of multivalent cations. In the systems with the lowest and the low content of spermidine (Fig. 7, B and C), there is an apparent competition between Mg2+ and Spe3+ ions for localization close to the DNA. For the system with the highest concentration of spermidine (Fig. 7 B), the fraction of Spe3+ ions able to localize close to the DNA is larger compared to the Mg2+ ions, which is expected given the higher affinity of spermidine toward the phosphates on the DNA backbone. Note also that in the system with highest spermidine content, the distributions for Na+, Mg2+, and Spe3+ have pronounced tails at radial distances larger than 15 nm. This explains the lower cation localization (larger DNA-cations average separation) observed for this system in Fig. 7 A. This localization of cations inside the capsid indicates that at the nanoscopic scale, there are regions along the packaged DNA backbone where attractive DNA–DNA interactions dominate as well as regions of mainly repulsive DNA–DNA interactions. This observation is also reflected on the snapshots of the helical axis of the packaged DNA shown in Fig. S3. There, a highly bent helical axis corresponds to regions of large attractive DNA–DNA interactions, where local condensation of DNA has occurred.

The peaks that appear in the probability distribution of the radial position of DNA are a signature of concentric shells near the capsid wall, and up to six of these peaks have been observed in cryo-EM images of mature ϕ29 capsids (15, 38). Note that the ϕ29 capsids are ∼10 times larger in volume than the capsids considered here; this could explain the presence of additional peaks in the cryo-EM images.

Conclusions

Most experimental studies of dsDNA packing inside nanometer-sized capsids have been carried out in bacteriophages such as ϕ29, λ, and T4. The most recent experimental work studied the effect of spermidine on the dynamics of DNA packing in phage ϕ29 (6, 33). It has been shown that spermidine3+ causes heterogeneous packing dynamics. Increased packing velocity was observed in a fraction of phages, but most exhibit slowing and premature stalling, suggesting that attractive interactions promote nonequilibrium DNA conformations that impede the motor (6). Moreover, it has also been shown that when packing is initiated without spermidine, the repulsive interactions between DNA promote the formation of more favorable (lower-energy) packed DNA conformations that persist and influence the packing dynamics even after switching to a net attractive condition (33). When the packing is initiated with high concentrations of spermidine, unfavorable jammed DNA conformations are formed during the early stages of packaging and can influence the subsequent dynamics and promote stalling even after the buffer is changed to a spermidine-free solution (33).

In the simulation results presented here, high concentrations of spermidine3+ did not produce premature stalling. Instead, the systems considered behaved similarly to the fraction of ϕ29 phages that showed increased packing velocity in the experiments. However, a small, but detectable increase in the heterogeneity of packing velocities was observed in the systems with magnesium and spermidine ions compared to the system with only salt. These differences vanish at the higher average packing velocities obtained when packing is done with a force of 150 pN. The average packing velocities observed in simulations are 107 times larger than in experiments and packing of the entire genome occurs in a few microseconds. In experiments, packing occurs over periods of hundredths of minutes. This allows DNA relaxation processes and transport of ionic species through the crowded capsid to create highly knotted or jammed structures that are capable of prematurely and intermittently stall the packing. Given the relatively short timescales at which packing occurs in simulations, these types of so-called jammed DNA structures do not have time to form. The simulation results presented here do show that the effect of spermidine on DNA packing will increase with decreasing packing. At concentrations of 15 mM causes an effective attraction between DNA phosphates of up to −2.3 kBT. These attractions induce DNA condensation inside capsid. This, in turn, leads to reduced capsid internal pressures and higher shear stresses in the packaged DNA compared to the systems with salt only.

The size of the capsids studied here is reminiscent of a system of genetic exchange that exists in the purple nonsulfur bacterium R. capsulatus, where DNA transmission is mediated by a small bacteriophage-like particle called the “gene transfer agent” (GTA) that transfers random 4.5-kbp segments of the producing cells genome to recipient cells (17). Transmission electron microscopy images of the R. capsulatus GTA show spherical particles with an ∼30-nm diameter, very similar to the 25 nm-diameter capsids studied in this work. The DNA packing process in GTAs does not appear to have been studied experimentally and therefore it is not yet clear if the packing proceeds in a similar way as in large bacteriophages, and more specifically, if the GTAs have functional DNA packing motors. However, the sequence homology of the R. capsulatus GTA terminases with the protein gp17, which is the key component of the T4 phage DNA packaging motor (20), appears to indicate that GTAs do use a motor mechanism to package their genomes. Given the nonparasitic function of GTAs, they appear especially attractive as a design template as gene delivery vectors for gene therapy purposes. The results presented in this work provide important guidance on specific ways to manipulate the DNA packing process inside compartments (such as that of the GTAs capsid) that are smaller than the persistence length of the dsDNA being packaged.

Author Contributions

J.J.d.P. and D.M.H. designed the research; A.C. and D.M.H. performed the research; D.M.H., J.L., and A.C. contributed analytic tools and simulation codes; A.C. analyzed the data; and A.C. and J.J.d.P. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by award No. 70NANB14H012 from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology as part of the Center for Hierarchical Materials Design (ChiMaD). Additional support from the U. Chicago MRSEC, through grant No. DMR-1420709, and a Kadanoff-Rice Fellowship to A.C. is gratefully acknowledged.

Editor: Tamar Schlick.

Footnotes

Andrés Córdoba’s present address is Department of Chemical Engineering, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile.

Six figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30225-4.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Migliori A.D., Keller N., Smith D.E. Evidence for an electrostatic mechanism of force generation by the bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging motor. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4173. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller D.N., Rickgauer J.P., Smith D.E. Ionic effects on viral DNA packaging and portal motor function in bacteriophage ϕ29. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11245–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701323104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrey C., Muthukumar M. Langevin dynamics simulations of genome packing in bacteriophage. Biophys. J. 2006;91:25–41. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloomfield V.A. DNA condensation by multivalent cations. Biopolymers. 1997;44:269–282. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:3<269::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Broek B., Noom M.C., Wuite G.J. Visualizing the formation and collapse of DNA toroids. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1902–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller N., delToro D., Smith D.E. Repulsive DNA-DNA interactions accelerate viral DNA packaging in phage ϕ29. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;112:248101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.248101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berndsen Z.T., Keller N., Smith D.E. Nonequilibrium dynamics and ultraslow relaxation of confined DNA during viral packaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:8345–8350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405109111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali I., Marenduzzo D., Yeomans J.M. Dynamics of polymer packaging. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:8635–8641. doi: 10.1063/1.1798052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spakowitz A.J., Wang Z.-G. DNA packaging in bacteriophage: is twist important? Biophys. J. 2005;88:3912–3923. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali I., Marenduzzo D., Yeomans J.M. Polymer packaging and ejection in viral capsids: shape matters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:208102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.208102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrov A.S., Harvey S.C. Structural and thermodynamic principles of viral packaging. Structure. 2007;15:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kindt J., Tzlil S., Gelbart W.M. DNA packaging and ejection forces in bacteriophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13671–13674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241486298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z., Wu J., Wang Z.-G. Osmotic pressure and packaging structure of caged DNA. Biophys. J. 2008;94:737–746. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arsuaga J., Tan R.K.-Z., Harvey S.C. Investigation of viral DNA packaging using molecular mechanics models. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101–102:475–484. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comolli L.R., Spakowitz A.J., Downing K.H. Three-dimensional architecture of the bacteriophage ϕ29 packaged genome and elucidation of its packaging process. Virology. 2008;371:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marenduzzo D., Orlandini E., Micheletti C. DNA-DNA interactions in bacteriophage capsids are responsible for the observed DNA knotting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22269–22274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang A.S., Beatty J.T. Genetic analysis of a bacterial genetic exchange element: the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:859–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang A.S., Zhaxybayeva O., Beatty J.T. Gene transfer agents: phage-like elements of genetic exchange. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hynes A.P., Mercer R.G., Lang A.S. DNA packaging bias and differential expression of gene transfer agent genes within a population during production and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent, RcGTA. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;85:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun S., Kondabagil K., Rao V.B. The structure of the phage T4 DNA packaging motor suggests a mechanism dependent on electrostatic forces. Cell. 2008;135:1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman G.S., Hinckley D.M., de Pablo J.J. Coarse-grained modeling of DNA curvature. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:165103. doi: 10.1063/1.4897649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinckley D.M., Lequieu J.P., de Pablo J.J. Coarse-grained modeling of DNA oligomer hybridization: length, sequence, and salt effects. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:035102. doi: 10.1063/1.4886336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinckley D.M., Freeman G.S., de Pablo J.J. An experimentally-informed coarse-grained 3-Site-Per-Nucleotide model of DNA: structure, thermodynamics, and dynamics of hybridization. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:144903. doi: 10.1063/1.4822042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman G.S., Lequieu J.P., de Pablo J.J. DNA shape dominates sequence affinity in nucleosome formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:168101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.168101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lequieu J., Córdoba A., de Pablo J.J. Tension-dependent free energies of nucleosome unwrapping. ACS Cent Sci. 2016;2:660–666. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinckley D.M., de Pablo J.J. Coarse-grained ions for nucleic acid modeling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:5436–5446. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shell M.S. The relative entropy is fundamental to multiscale and inverse thermodynamic problems. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:144108. doi: 10.1063/1.2992060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan Y., Korolev N., Nordenskiöld L. An advanced coarse-grained nucleosome core particle model for computer simulations of nucleosome-nucleosome interactions under varying ionic conditions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995;117:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grønbech-Jensen N., Farago O. A simple and effective Verlet-type algorithm for simulating Langevin dynamics. Mol. Phys. 2013;111:983–991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grønbech-Jensen N., Hayre N.R., Farago O. Application of the G-JF discrete-time thermostat for fast and accurate molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014;185:524–527. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith D.E., Tans S.J., Bustamante C. The bacteriophage straight ϕ29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature. 2001;413:748–752. doi: 10.1038/35099581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller N., Grimes S., Smith D.E. Single DNA molecule jamming and history-dependent dynamics during motor-driven viral packaging. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nphys3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berndsen Z.T., Keller N., Smith D.E. Continuous allosteric regulation of a viral packaging motor by a sensor that detects the density and conformation of packaged DNA. Biophys. J. 2015;108:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benevides J.M., Stow P.L., Thomas G.J., Jr. Differences in secondary structure between packaged and unpackaged single-stranded DNA of bacteriophage ϕX174 determined by Raman spectroscopy: a model for ϕ X174 DNA packaging. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4855–4863. doi: 10.1021/bi00234a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aubrey K.L., Casjens S.R., Thomas G.J., Jr. Secondary structure and interactions of the packaged dsDNA genome of bacteriophage P22 investigated by Raman difference spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11835–11842. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelta J., Livolant F., Sikorav J.-L. DNA aggregation induced by polyamines and cobalthexamine. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5656–5662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson A.A., Leiman P.G., Rossmann M.G. Structure determination of the head-tail connector of bacteriophage ϕ29. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1260–1269. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901010435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Earnshaw W.C., Casjens S.R. DNA packaging by the double-stranded DNA bacteriophages. Cell. 1980;21:319–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evilevitch A., Castelnovo M., Gelbart W.M. Measuring the force ejecting DNA from phage. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:6838–6843. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evilevitch A., Gober J.W., Gelbart W.M. Measurements of DNA lengths remaining in a viral capsid after osmotically suppressed partial ejection. Biophys. J. 2005;88:751–756. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.