Abstract

Objective:

Anxiety towards dental procedures are common difficulties that may be experienced by dental patients all over the world. This study focused on evaluating the dental anxiety frequency and its relationship with age, gender, educational level, and past dental visits among patients attending the outpatient clinics of College of Dentistry, Al Jouf University, Saudi Arabia.

Material and Methods:

A total of 221 patients, aged 21–50 years were selected for the study. A questionnaire comprising the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) was used to measure the level of dental anxiety. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20.

Results:

The mean anxiety score of the 221 patients was 11.39 (SD ± 2.7). Independent t-test showed a significant variation between the age groups with regards to their mean overall anxiety score (P < 0.05), which reduced with increasing age. A significant difference was found by independent t-test in the mean total score between male and female groups and regarding previous dental visit (P < 0.05). Regarding education level, there was no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Younger patients, female, and patients with previous unpleasant dental experience were associated with increased MDAS score.

Clinical Significance:

The present study was done for better patient management and proper treatment plan development for dentally anxious patients.

Keywords: Dental anxiety, dental fear, modified dental anxiety scale

Introduction

Dental anxiety refers to patient's response toward stresses associated with dental procedures, in which the stimulus is vague, anonymous, or not present at the moment.[1,2]

Fear and anxiety and related to dental procedures are one of the problems frequently experienced by patients all over the world. Despite the innovations in dental materials, technologies, and improved knowledge, a significant percentage of patients suffer from dental anxiety. Dental anxiety is rated fourth between common fears and ninth among intense fears.[3]

Many patients are afraid of some of the stimuli involved with dental therapy, which could affect the dentist–patient relationship and the dental treatment plan.[4,5] The occurrence of dental anxiety may be attributed to age, sex, educational qualification, and socioeconomic position.[1,6,7,8] It is also related to many factors such as personality characteristics, a history of traumatic dental experience, painful dental experience in childhood, or even from indirect learning from dentally anxious peers or family members.[9,10,11,12,13]

Astramskaitė[14] reviewed previous studies to identify reliable factors affecting anxiety in adult patients undergoing tooth extraction procedures, and found that there are many factors that may affect dental anxiety such as level of disturbance during the procedure, pain experience or expectations, difficulty of the procedure, and marital status.

Dental anxiousness is different among various individuals and communities.[6,11,15,16,17] Suhani[18] studied dental anxiety and fear among a deaf population in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He found that higher percentages were noted among women and people with a history of traumatic dental experience.

Soares[19] analyzed the predictors of dental anxiety in children and found that family income and psychological well-being were inversely associated to dental anxiety in 5–7-year-old children. Sayed[20] concluded that projecting the visual output of the dental procedures is effective in distracting the child patient during the procedure and subsequently reducing dental anxiety. In contrast, Mishra[21] stated that the multimedia was not found to be significantly affecting the behavior of the child in dental operatory.

Kilinç[22] studied the effect of different places on anxiety levels and stated that the children felt more anxious at the dental clinic that at the kindergarten, although the children had been informed about dentistry and were introduced to a dentist at the kindergarten. There was increase in children's pulse rates which is a physical indicator of their increased anxiety levels. Determining dentally anxious patients is essential for pain control and better treatment planing.[23]

Anxious patients have more missing and decayed teeth in contrast to non-anxious patients as they stay away from dental treatment and delay their dental visit. In addition, their poor oral health status which can affect their quality of life in a negative manner.[24,25]

Anxious patients need to take more analgesics for pain relief.[7] Dental anxiety has a consistent impact on pain through the entire period of dental treatment, and therefore, should be assessed as a vital step not only in the management of anxiety for patients with high-dental anxiety but also in pain control for all patients.[26]

Several scales have been developed to assess patients’ anxiety and fear level so they can use proper management strategies. Objective evaluation of dental anxiety can be done using anxiety questionnaires such as Dental Fear Survey (DFS), Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale (CDAS), Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), General Geer Fear Scale, Chotta Bheem-Chutki Scale, Venham's Pictorial Scale (VPS), Facial Image Scale (FIS), State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI), and Getz Dental Belief Survey.[27,28,29,30]

MDAS is based on the CDAS. MDAS is the most popular scale for measuring dental anxiety in the UK.[31] It is reliable, valid, and has excellent psychometric properties. Answering the questionnaire is easy and quick, and therefore, it is appropriate for clinical use.[32,33]

It is a brief five-item questionnaire. Each item has five answers; the answers vary from “not anxious” scored 1 to “extremely anxious” scored 5. It is a straight-forward and easy to complete and requires less time for finishing.[34]

MDAS has been used in many countries all over the world and has been translated to different languages.[1,32,34,35,36,37,38,39] Filling of the questionnaire does not increase patient anxiety, and has been shown to decrease anxiety in clinical settings. It has been established to be reliable and valid cross-culturally, and hence has been translated into different languages.[37,39,40,41]

Few studies re available on the incidence of dental anxiety and factors affecting dental anxietydental patients in Saudi Arabia.[35,36,42] For improved patient management and development of better treatment strategies for anxious dental patients, the present study was conducted.

Material and Methods

This study was cross-sectional in design, and was conducted from January 2016 to June 2016 among 221 patients (aged 21–50 years) attending the outpatient clinics of College of Dentistry, Al-Jouf University, Saudi Arabia. Patients who had generalized anxiety disorders and intellectual disability were excluded. Based on standard deviation from the pilot study and previous studies, it was found that 200 cases are enough for conducting the research at power 0.80, confidence interval 0.95, and alpha level of 0.05.[3,5]

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Aljouf University. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after explaining the methodology prior to enrolment in the study.

Patients were categorized into two groups according to their age – Group I: 21–35 years and Group II – 36–50 years.

Assessment tools consisted of a history form (concerning age, gender, educational level, and past dental visits) and a questionnaire comprising the Arabic version of MDAS, which was used to assess the level of dental anxiety.[35,36]

MDAS consists of 5 questions; each question has a five-category rating scale answer ranging from one which considered “non-anxious” to five which considered “extremely anxious.” It concerns patients’ anxiety in the fallowing situations:[5]

Anticipating a visit to dentist,

Waiting for treatment in the dentist's office,

Waiting for teeth drilling on the dental chair,

Waiting for scaling on the dental chair, and

Waiting for a local anesthetic injection on the dental chair.

Summation of all answers represents a score for the level of dental anxiety with a minimum score of 5 and a maximum score of 25. Patients with scores of 11 or more are considered dentally anxious. Scores from 11–14 are considered to indicate moderate anxiety; and scores from 15–19 are considered to indicate high anxiety.[5]

Data was analyzed using IBM Corp., IBM SPSSTM Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY. The independent t-test was used to study the difference between the groups.

Results

Out of the 300 questionnaires distributed, only 221 patients responded due to lack of time or refusal to participant in the study. Among the 221 patients who completed the questionnaire, 186 were males and 35 were females. The selected patients were allocated to two age groups – 62.8% of the participants were 21–35 years old. The mean age was 32.2 years.

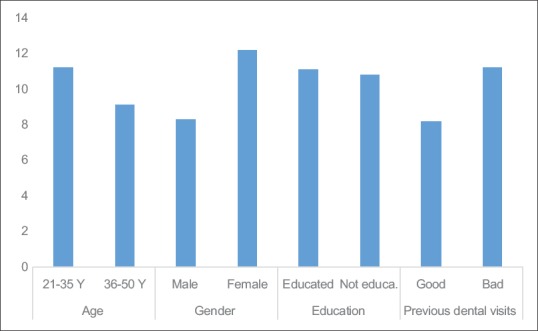

The incidence of dental anxiety among the study population was 51.6%. Based on the severity of dental anxiety, 22.1% of patients were found to be moderately anxious, 17.1% and 12.4% of patients were found to be highly and extremely anxious, respectively. Figure 1 shows the mean of dental anxiety score of different groups with respect to age, gender, education, and previous dental visits.

Figure 1.

Mean dental anxiety scoresfor different study groups

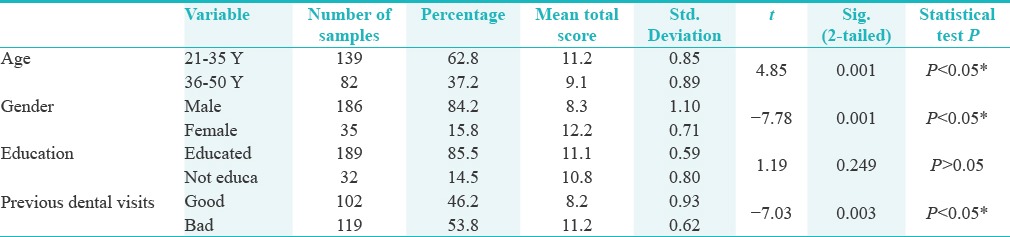

The average for the questions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the MDAS was 1.91, 1.96, 2.45, 2.31, and 2.76, respectively. The mean total anxiety score of the 221 patients was 11.39 (SD ± 2.7). Independent t-test revealed astatistically significant differencebetween the mean total anxiety scores of the two age groups (P < 0.05) [Table 1]. The anxiety was decreased in the old age group.

Table 1.

Variables assessed in the study with sample size, percentage, mean total score and statistical test P

Most of the women selected in the study were “more anxious” toward all items in the dental anxiety questionnaire. Independent t-test showed a statistically significant differencebetween the mean total score of the two gender group (P < 0.05).

Regarding the education level, the independent t-test demonstrated no significant difference between the mean dental anxiety score of the two groups [Table 1].

A total of 85.7% of the patients had visited a dentist once before, and among them, 23.15% had a undesirable experience in their past dental visit. The patients who had a bad experience had higher anxiety levels than those who had good past dental experience. Independent t-test showed a statistically significant difference between the mean total scores of the patients with good and bad past dental experience (P < 0.05) [Table 1].

Discussion

The present study was carried out to assess the dental anxiety level and the factors affecting dental anxiety among the patients attending the outpatient clinics of College of Dentistry, Aljouf University, Saudi Arabia. The mean total dental anxiety score was 11.39 (SD ± 2.7), which is similar to the anxiety levels reported from studies in India,[9] China,[39] and Greece.[33] However, this score is different from the mean score reported by Erten[4] and Saatchi[5] who reported MDAS score of 12.34 ± 4.74.

The prevalence of dental anxiety between the study population was 51.6%. Based on the severity of dental anxiety, 22.1%, 17.1%, and 12.4% of the patients were found to be moderately anxious, highly anxious, and extremely anxious, respectively.

In a sample of Swedish adults, Svensson[17] found that the prevalence of patients with severe dental anxiety was 4.7%. His result was less than the prevalence reported by this study (12.4%). Prevalence reported by this study was higher than that reported in other studies by Do Nascimento et al. (23%),[3] Malvania (46%),[6] and Taani (39%).[42] However, it was less than the prevalence reported by studies conducted by Saatchi (58.8%).[5] Gaafar[15] studied dental anxiety prevalence in adult patients attending the dental clinics at the University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia and found that the prevalence of dental anxiety among the study sample was 27%. This change may be related to different sample sizes, different methodology, or geographical variation.

The results from this study showed an inverse relationship between the age and dental anxiety score. The older individuals showed lesser anxiety level than younger individuals; this is in agreement with the study by Acharya[9] and that of Abanto.[8] This finding is contrary to the findings of Tunc[38] and Saatchi[5] who reported that the dental fear and anxiety were not affected by age. These results might be due to a general decrease in anxiety with aging and increased exposure to other diseases.

Most women were “more anxious” towards all items in the dental anxiety questionnaire. The study showed a difference in dental anxiety level between males (mean total anxiety score 8.3) and females (mean total anxiety score 12.2). This result is in agreement with the studies by Erten,[4] Auerbach,[43] Saatchi,[5] and de Jongh et al.[44] This result is not in agreement with the study by Santhosh kumar et al.[23] and Thomson et al.[16] This result may be attributed to cultural differences.

Regarding education, the results of the present study showed that education had no significant effect on anxiety toward dental procedures. There was no statistical significant difference in the dental anxiety between educated and non-educated group. This result is in agreement with the study by Saatchi[5] who mentioned that the dental fear and anxiety were not affected by education level. The result is not in agreement with the study by Erten[4] who indicated that patients with a primary school education had the highest anxiety scores in comparison to highly educated patients.

Anxiety towards injection scored the highest mean score, which was similar to the findings in Danish adults.[45] The results of the study showed a significant difference in dental anxiety based on past dental visit. Patients who had visited a dentist before showed less anxiety than other patients who had not visited a dentist at any time. Patients who had visited a dentist with a undesirable dental experience showed higher level of anxiety. This result is in agreement with the results of the studies done by Acharya,[9] Saatchi,[5] and Moore et al.[45]

The limitations of the study includes a small sample size and using a self-administered questionnaire, which could be biased as there are chances that the patients may over or underestimate their responses.

Conclusions

Within the study limitations, it can be concluded that younger patients and females were dentally more anxious. There is no significant difference in dental anxiety level in the base of educational attainment. Past undesirable dental experiences were associated with significantly increased anxiety scores.

Recommendations

Further evaluation and analysis of anxiety associated with dental treatment may clarify more information for better patient management and proper treatment plan for patients suffering from dental anxiety. There is a need for appropriate scale that includes both the patient's evaluation and doctor's observation to accurately analyze dental anxiety.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Humphris GM, Dyer TA, Robinson PG. The modified dental anxiety scale: UK general public population norms in 2008 with further psychometrics and effects of age. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaakkola S, Rautava P, Alanen P, Aromaa M, Pienihäkkinen K, Räihä H, et al. Dental fear: One single clinical question for measurement. Open Dent J. 2009;3:161–6. doi: 10.2174/1874210600903010161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.do Nascimento DL, da Silva Araújo AC, Gusmão ES, Cimões R. Anxiety and fear of dental treatment among users of public health services. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9:329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erten H, Akarslan ZZ, Bodrumlu E. Dental fear and anxiety levels of patients attending a dental clinic. Quintessence Int. 2006;37:304–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saatchi M, Abtahi M, Mohammadi G, Mirdamadi M, Binandeh ES. The prevalence of dental anxiety and fear in patients referred to Isfahan Dental School, Iran. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:248–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malvania EA, Ajithkrishnan CG. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of dental anxiety among a group of adult patients attending a dental institution in Vadodara city, Gujarat, India. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:179–80. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.79989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazancioglu HO, Dahhan AS, Acar AH. How could multimedia information about dental implant surgery effects patients’ anxiety level? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22:e102–e7. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abanto J, Vidigal EA, Carvalho TS, Sá SN, Bönecker M. Factors for determining dental anxiety in preschool children with severe dental caries. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31:e13. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya S. Factors affecting dental anxiety and beliefs in an Indian population. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:259–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KC, Bassiur JP. Salivary Alpha Amylase, Dental Anxiety, and Extraction Pain: A Pilot Study. Anesth Prog. 2017;64:22–8. doi: 10.2344/anpr-63-03-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barreto KA, Dos Prazeres LD, Lima DS, Soares FC, Redivivo RM, da Franca C, et al. Factors associated with dental anxiety in Brazilian children during the first transitional period of the mixed dentition. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2017;18:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s40368-016-0264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasiliki B, Konstantinos A, Nikolaos K, Vassilis K, Cor VL, Jaap V. Relationship between Child and Parental Dental Anxiety with Child's Psychological Functioning and Behavior during the Administration of Local Anesthesia. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40:431–7. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-40.6.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan AG, Rodd HD, Porritt JM, Baker SR, Creswell C, Newton T, et al. Children's experiences of dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:87–97. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astramskaite I, Poskevicius L, Juodzbalys G. Factors determining tooth extraction anxiety and fear in adult dental patients: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:1630–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaffar BO, Alagl AS, Al-Ansari AA. The prevalence, causes, and relativity of dental anxiety in adult patients to irregular dental visits. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:598–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:289–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svensson L, Hakeberg M, Boman UW. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Community Dent Health. 2016;33:121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suhani RD, Suhani MF, Badea MD. Dental anxiety and fear among a young population with hearing impairment. Clujul Med. 2016;89:143–9. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soares FC, Lima RA, Santos Cda F, de Barros MV, Colares V. Predictors of dental anxiety in Brazilian 5-7years old children. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;67:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed A, Ranna V, Padawe D, Takate V. Effect of the video output of the dental operating microscope on anxiety levels in a pediatric population during restorative procedures. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;34:60–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.175516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra G, Thakur S, Singhal P, Ghosh SN, Chauhan D, Jayam C. Assessment of child behavior in dental operatory in relation to sociodemographic factors, general anxiety, body mass index and role of multi media distraction. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;34:159–64. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.180446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilinç G, Akay A, Eden E, Sevinç N, Ellidokuz H. Evaluation of children's dental anxiety levels at a kindergarten and at a dental clinic. Braz Oral Res. 2016:30. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Bhargav P, Patel A, Bhati M, Balasubramanyam G, Duraiswamy P, et al. Does dental anxiety influence oral health-related quality of life? Observations from a cross-sectional study among adults in Udaipur district, India. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:245–54. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esa R, Savithri V, Humphris G, Freeman R. The relationship between dental anxiety and dental decay experience in antenatal mothers. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermaire JH, van Houtem CM, Ross JN, Schuller AA. The burden of disease of dental anxiety: Generic and disease-specific quality of life in patients with and without extreme levels of dental anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci. 2016;124:454–8. doi: 10.1111/eos.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CS, Wu SY, Yi CA. Association between Anxiety and Pain in Dental Treatment. J Dent Res. 2017;96:153–62. doi: 10.1177/0022034516678168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Namankany A, Ashley P, Petrie A. The development of a dental anxiety scale with a cognitive component for children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:e219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klages U, Einhaus T, Seeberger Y, Wehrbein H. Development of a measure of childhood information learning experiences related to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health. 2010;27:122–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadana G, Grover R, Mehra M, Gupta S, Kaur J, Sadana S. A novel Chotta Bheem-Chutki scale for dental anxiety determination in children. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6:200–5. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.183108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonafe FS, Campos JA. Validation and Invariance of the Dental Anxiety Scale in a Brazilian sample. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:e138. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dailey YM, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. The use of dental anxiety questionnaires: A survey of a group of UK dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2001;190:450–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphris GM, Freeman R, Campbell J, Tuutti H, D’souza V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J. 2000;50:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coolidge T, Arapostathis KN, Emmanouil D, Dabarakis N, Patrikiou A, Economides N, et al. Psychometric properties of Greek versions of the Modified Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) and the Dental Fear Survey (DFS) BMC Oral Health. 2008;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: Validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abu-Ghazaleh SB, Rajab LD, Sonbol HN, Aljafari AK, Elkarmi RF, Humphris G. The Arabic version of the modified dental anxiety scale. Psychometrics and normative data for 15-16 year olds. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:725–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahammam MA, Hassan MH. Validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the modified dental anxiety scale in Saudi adults. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:1384–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coolidge T, Hillstead MB, Farjo N, Weinstein P, Coldwell SE. Additional psychometric data for the Spanish Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, and psychometric data for a Spanish version of the Revised Dental Beliefs Survey. BMC Oral Health. 2010;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tunc EP, Firat D, Onur OD, Sar V. Reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) in a Turkish population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:357–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan S, Freeman R, Lahti S, Lloyd-Williams F, Humphris G. Some psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale with cross validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campos RC. Additional psychometric data for a Portuguese scale to assess history of depressive symptomatology with a community sample. Psychol Rep. 2010;107:441–2. doi: 10.2466/02.09.13.PR0.107.5.441-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahammam MA. Validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the state-trait anxiety inventory in a Saudi dental setting. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:668–74. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.6.13935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taani DSMQ. Dental fear among a young adult Saudian population. Int Dent J. 2001;51:62–6. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Auerbach SM, Kendall PC. Sex differences in anxiety response and adjustment to dental surgery: Effects of general vs. specific preoperative information. J Clin Psychol. 1978;34:309–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197804)34:2<309::aid-jclp2270340209>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Jongh A, Stouthard ME, Hoogstraten J. Sex differences in dental anxiety. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 1991;98:156–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore R, Birn H, Kirkegaard E, Brødsgaard I, Scheutz F. Prevalence and characteristics of dental anxiety in Danish adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:292–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]