Abstract

The use of the tetrahydropyranyl (Thp) group for the protection of serine and threonine side‐chain hydroxyl groups in solid‐phase peptide synthesis has not been widely investigated. Ser/Thr side‐chain hydroxyl protection with this acid‐labile and non‐aromatic moiety is presented here. Although Thp reacts with free carboxylic acids, it can be concluded that to introduce Thp ethers at the hydroxyl groups of N‐protected Ser and Thr, protection of the C‐terminal carboxyl group is unnecessary due to the lability of Thp esters. Thp‐protected Ser/Thr‐containing tripeptides are synthesized and the removal of Thp studied in low concentrations of trifluoroacetic acid in the presence of cation scavengers. Given its general stability to most non‐acidic reagents, improved solubility of its conjugates and ease with which it can be removed, Thp emerges as an effective protecting group for the hydroxyl groups of Ser and Thr in solid‐phase peptide synthesis.

Keywords: protecting groups, serine, solid-phase peptide synthesis, tetrahydropyranyl group, threonine

Since the first synthesis of a tetrapeptide on a solid support in 1963,1 methodological advances in solid‐phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) have allowed the preparation of a vast number of complex peptides.2 Accordingly, a key factor in peptide science is amino acid side‐chain protection, a procedure used to prevent undesired side reactions. In peptide and protein science, serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) play important roles as their hydroxyl side chains are crucial as phosphorylation and O‐glycosylation sites,3, 4 as well as for the preparation of depsipeptides,5, 6 among other molecules. From a synthetic point of view, hydroxyl‐containing amino acids can be introduced into peptides without side‐chain protection.7 However, unprotected hydroxyl functionalities in Ser and Thr can undergo side reactions such as dehydration or O‐acylation, followed by O→N migration after amino group deprotection, particularly in the presence of powerful activating agents such as carbodiimides.7 This undesirable reaction is more predominant for the primary alcohol of Ser than for the secondary alcohol of Thr. Some studies have demonstrated peptide synthesis without the protection of the hydroxyl side chains of Ser and Thr; however, care must be taken in choosing the activating agents.8, 9 This point is especially relevant in SPPS because this method involves the use of an excess of activating agents.10 Thus, it can be concluded that the safest way to introduce hydroxylated amino acids is by protecting their side chains.

In peptide synthesis, hydroxyl functionalities are protected as ethers, which are more stable than the corresponding carbamates. Moreover, ethers are less prone to taking part in side reactions.11 The most widely used hydroxyl protecting groups for the common tert‐butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) and 9‐fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) strategies are benzyl and tert‐butyl (tBu), respectively. Trityl has been used less often for Ser and Thr in SPPS12, 13 because trityl ethers are much more sensitive to acidic conditions than the corresponding tBu ethers. Additionally, trityl‐protected Ser and Thr can be selectively removed in the presence of a tBu ether in SPPS with a low concentration of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA),14 taking advantage of the requirement for a concentration of at least 50 % TFA for cleavage of tBu ethers.13

Tetrahydropyranyl (Thp)15 is widely used as a hydroxyl protecting group in organic chemistry16 due to its low cost, ease of introduction, general stability to most non‐acidic reagents, good solubility, and the ease with which it can be removed if the functional group it protects requires further manipulation.17 Accordingly, Thp has additional advantages over benzyl‐based protecting groups as it lacks aromaticity and is characterized by atom economy and better solubility. In addition to producing more protected hydrophobic peptides, the use of bulky or aromatic protecting groups in SPPS affects inter‐/intrachain interactions during peptide elongation and could therefore dramatically affect the purity of the final product.18 The main drawback of using Thp in organic synthesis is the formation of a new stereocenter, which leads to diastereomeric mixtures. However, if Thp is used as a protecting group or linker in SPPS, its use is temporary, and therefore the formation of a new stereocenter is not a limitation.

As Thp has received little attention as a protecting group in SPPS, we decided to study its potential for protecting Ser and Thr. There are only a few examples of the use of Thp to protect the side chains of Ser19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and Thr.25, 26 Furthermore, the methods described in the literature for the protection of Ser and Thr hydroxyl groups involve prior protection of the carboxyl group. Here we report an efficient method for Thp protection of the hydroxyl side chains of Ser and Thr with free carboxyl groups and its application in SPPS.

In 2006, Krishnamoorthy et al. introduced Thp as a protecting group for the Thr side chain in the synthesis of callipeltin B.25 For the introduction of Thp into the side chain of Thr, the authors used Fmoc‐Thr‐OAllyl as a precursor, which was reacted with dihydropyran (DHP) in the presence of pyridinium p‐toluenesulfonate (PPTS) using dichloroethane as solvent. The reaction was allowed to react at 60 °C for 12 h. Removal of the allyl group afforded the desired Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH, which was used in the next step without purification. However, we synthesized Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)/Thr(Thp)‐OH in good yield using an acid‐catalyzed reaction between Fmoc‐Ser/Thr‐OH and DHP, with p‐toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA) as catalyst and dichloromethane as solvent. We found that protection of the carboxyl group was unnecessary. Although carboxylic acids reacts with DHP similarly to alcohols, the corresponding hemiacetal ester is unstable, and during the work‐up the Thp was cleaved from the carboxyl group.27, 28 Thus, Fmoc‐Thr/Ser‐OH can be side‐chain protected without the need for protection of the carboxyl group. This is highly relevant when dealing with the protection of unnatural ω‐hydroxy amino acids that are difficult to synthesize. Examples of such compounds include allo‐Thr derivatives and other β‐hydroxy amino acids that are natural cyclodepsipeptides.29, 30 Furthermore, we demonstrated that PTSA is a more convenient and more efficient catalyst than PPTS, as the latter requires the reaction mixture to be heated to nearly 60 °C for 10–12 h. PTSA was a more efficient catalyst as the reaction rate increased (reaction time <60 min at room temperature) compared to PPTS. The use of Thp as a protecting group for the hydroxyl side chain in Fmoc‐Ser/Thr‐OH increased the solubility of the amino acid, which is consistent with our earlier reports.18

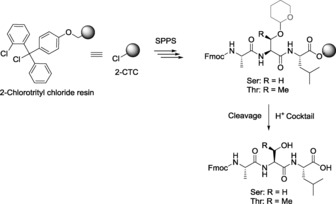

In order to determine the acid stability of Thp as a protecting group, Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH and Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH were studied under a range of acidolytic conditions (Table 1). The lability of the Thp group was greatly increased in the presence of triisopropylsilane (TIS) as a scavenger compared with H2O (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Furthermore, we prepared the model Thp‐protected tripeptides Fmoc‐Ala‐Xxx(Thp)‐Leu‐O‐2CTC (where Xxx=Ser or Thr, 2CTC=2‐chlorotrityl chloride) using N,N′‐diisopropylcarbodiimide (3 equiv.) and ethyl (hydroxyimino)cyanoacetate (Oxyma Pure, 3 equiv.) in N,N‐dimethylformamide (DMF) with a 3 min pre‐activation time and 1.5 h coupling time at 25 °C. Both Thp‐protected Ser and Thr were stable under the coupling conditions tested and also to the Fmoc deprotection in piperidine/DMF (1:4). In additional, the lability of the synthesized tripeptides was also studied under the indicated cleavage conditions (Scheme 1 and Table 2). During tripeptide elongation, the Thp group remained stable and was cleaved with a low concentration of TFA to afford the deprotected tripeptide, as shown by the HPLC chromatograms (see the Supporting Information). Complete cleavage was obtained in the presence of TIS as a scavenger and at low TFA concentration (Table 2, entries 2 and 7).

Table 1.

Acid lability studies of Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH and Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH.

| Entry | Compound | Deprotecting cocktail | Reaction time [min] | Deprotected amino acid [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH | TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:99) | 60 | 56 |

| 2 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (2:98) | 30 | 97 | |

| 3 | TFA/H2O/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 30 | 97 | |

| 4 | TFA/TIS/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 15 | >99 | |

| 5 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (5:95) | 30 | 98 | |

| 6 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (10:90) | 30 | 98 | |

| 7 | TFA/H2O/CH2Cl2 (10:2:88) | 15 | >99 | |

| 8 | TFA/TIS/CH2Cl2 (10:2:88) | 15 | >99 | |

| 9 | Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH | TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:99) | 60 | 93 |

| 10 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (2:98) | 15 | >99 |

Scheme 1.

Removal of the Thp group under acidic conditions.

Table 2.

Acid lability studies of Fmoc‐Ala‐Ser(Thp)‐Leu‐OH and Fmoc‐Ala‐Thr(Thp)‐Leu‐OH.

| Entry | Compound | Deprotecting cocktail | Reaction time [min] | Deprotected peptide [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fmoc‐Ala‐Ser(Thp)‐Leu‐OH | TFA/H2O/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 30 | 96 |

| 2 | TFA/TIS/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 15 | >99 | |

| 3 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (3:97) | 60 | 97 | |

| 4 | Fmoc‐Ala‐Thr(Thp)‐Leu‐OH | TFA/CH2Cl2 (1:99) | 60 | 92 |

| 5 | TFA/CH2Cl2 (2:98) | 15 | >99 | |

| 6 | TFA/H2O/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 15 | >99 | |

| 7 | TFA/TIS/CH2Cl2 (2:0.5:97.5) | 15 | >99 |

In addition to the aforementioned use of Thp as a protecting group, the Thp moiety was also studied as a cleavable linker for SPPS. Ellman resin has been found to be convenient for the synthesis of a wide range of hydroxyl‐containing organic compounds.31 However, there are only a few reports on the use of this resin for the synthesis of peptide alcohols.32 Taking these facts into consideration, we attempted to introduce Fmoc‐Ser/Thr‐NH2 onto Ellman resin using PTSA as catalyst and CH2Cl2/THF (1:4) as solvent. However, we were unable to anchor it onto the resin due to solubility issues. Therefore, Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe was attached to Ellman resin under similar reaction conditions using PTSA as catalyst and THF as solvent. Cleavage studies revealed that Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe anchored to Ellman resin at the hydroxyl side chain even in THF.

In summary, we studied the PTSA‐catalyzed Thp protection of the hydroxyl side chains of Ser and Thr. Our findings reveal that there is no need to protect the C‐terminal carboxyl group, as the corresponding hemiacetal ester is unstable, and Thp is removed from the carboxyl group during aqueous work‐up. We also conclude that the deprotection of Thp from side chains of Ser and Thr can be achieved using lower concentrations of TFA (2 %) in the presence of water and TIS as scavengers over short reaction times (approximately 15 min). Unexpectedly, Thp protection of the hydroxyl side chain of Thr was slightly more unstable than that of Ser. Similar trends have been found for model peptides using 2‐CTC resin. The Thp group was stable during peptide elongation and the Fmoc elimination step on resin. Among the scavengers used, TIS proved to be more efficient than water. Furthermore, we analyzed the incorporation of Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe to the Ellman resin using PTSA as a catalyst and THF as the solvent. Our results reveal Thp to be a valuable protecting group for Ser and Thr if applied to SPPS using the Fmoc/tBu strategy. Given the solubility of its peptide ethers and ease of introduction, Thp might be particularly useful for the effective synthesis of Ser‐ or Thr‐rich peptides and for the protection of unnatural ω‐hydroxy amino acids (allo‐Thr derivatives and other β‐hydroxy amino acids) that are difficult to synthesize.

Experimental Section

All reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification, unless otherwise stated. 2‐CTC resin and Fmoc‐protected amino acids were purchased from GL Biochem Pvt. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ellman resin was supplied by Merck. NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shift values are expressed in parts per million (ppm).For shorter reaction times (2–5 min), the reactions were manually stirred with a Teflon rod, whereas for longer reactions times (>30 min), they were stirred on a Unimax 1010 shaker (Heidolph Instruments). Solvents were removed from the reacion under reduced pressure. All the reactions were performed at room temperature (≈25 °C). Each reaction step was followed by washing of the peptide resin with DMF (4×1 min) and CH2Cl2 (4×1 min). Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1100 system using a Phenomenex C18 column (3 μm, 4.6×50 mm; solvent A: 0.1 % TFA in H2O; solvent B: 0.1 % TFA in CH3CN). LC–MS was performed on a Shimadzu 2020 UFLC‐MS instrument using an YMC‐Triart C18 column (5 μm, 4.6×150 mm; solvent A: 0.1 % formic acid in H2O; solvent B: 0.1 % formic acid in CH3CN). Data processing was carried out using LabSolution software. High‐resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed using a Bruker ESI‐QTOF mass spectrometer in positive‐ion mode.

Synthesis of Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH

PTSA (14.5 mg, 0.077 mmol) was added to a suspension of Fmoc‐Ser‐OH (500 mg, 1.52 mmol) and DHP (277 μL, 3.06 mmol) in CH2Cl2. The mixture was allowed to react for 30 min at RT. Afterwards, the organic layer was washed with brine (3×20 mL) and water (3×20 mL) and then dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified on a silica column using n‐hexane/EtOAc (1:1). The collected fractions were concentrated to afford a white solid (478 mg, 76 % yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSOd 6): δ=7.88 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.73 (t, J=6.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.63 (t, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 7.41 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.32 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 4.63–4.56 (m, 1 H), 4.34–4.18 (m, 4 H), 3.92–3.57 (m, 4 H), 1.73–1.40 ppm (m, 6 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSOd 6): δ=171.9, 143.8, 140.8, 127.5, 126.9, 125.2, 120.0, 98.5, 97.4, 66.0, 61.3, 54.4, 46.7, 29.9, 24.9, 18.8 ppm; HPLC: linear gradient of H2O/MeCN 5:95 to 0:100; tR: 10.4 min; LC–MS: m/z: calcd for C23H25NO6: 411.4; found: 410 [M−H]+; HRMS: m/z: calcd for C23H26NO6: 412.1760 [M+H]+; found: 412.1745.

Synthesis of Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH

PTSA (14 mg, 0.073 mmol) was added to a suspension of Fmoc‐Thr‐OH (500 mg, 1.46 mmol) and DHP (265 μL, 2.92 mmol) in CH2Cl2. The mixture was allowed to react for 60 min at RT. Afterwards, the organic layer was washed with brine (3×20 mL) and water (3×20 mL) and then dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified on a silica column using n‐hexane/EtOAc (1:1). The collected fractions were concentrated to afford a white solid (453 mg, 73 % yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSOd 6): δ=12.8 (s, 1 H), 7.88 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.77 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.41 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.32 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.16 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.77–4.62 (m, 1 H), 4.33–4.18 (m, 3 H), 4.17–3.98 (m, 2 H), 3.85–3.66 (m, 1 H), 3.45–3.37 (m, 1 H), 1.78–1.32 (m, 6 H), 1.22–1.05 ppm (m, 3 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSOd 6): δ=171.7, 156.6, 143.9, 140.6, 127.6, 127.0, 125.3, 120.1, 99.4, 94.0, 69.5, 65.9, 60.9, 46.9, 30.1, 25.0, 20.3, 18.6 ppm; HPLC: linear gradient of H2O/MeCN 5:95 to 0:100; tR: 10.8 min; LC–MS: m/z: calcd for C24H27NO6: 425.47; found: 424 [M−H]+; HRMS: m/z: calcd for C24H28NO6: 426.1917 [M+H]+; found: 426.1896.

Peptide Synthesis with Ellman (DHP) resin

Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe (50 mg, 0.059 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was added to Ellman (DHP) resin (50 mg, f=1.18 mmol g−1) after the latter was swelled in CH2Cl2 for 10 min. PTSA (0.28 mg, 0.0015 mmol) in THF (1 mL) was added to the resin. The reaction was stirred for 30 min and the resin was then washed with CH2Cl2 (2×5 mL) and dried. The dried resin was used to study the lability of Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe from Ellman resin.

Lability Experiments

The protected Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH and Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH (1 mg) were treated at RT with cleavage cocktails (200 μL), which were CH2Cl2 solutions containing different percentages of TFA and scavengers (water and/or TIS; Table 1). The reaction was monitored by RP‐HPLC [linear gradient of H2O/MeCN (5:95) over 15 min] after 15, 30, and 60 min of treatment. After each interval, an aliquot of 20 μL was withdrawn, the solvent was removed under nitrogen stream and the residue re‐dissolved in MeCN (400 μL). Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH, tR=10.46 min; Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH, tR=10.89 min. Cleavage of Fmoc‐Ser‐OMe from the DHP resin was achieved using 2 % TFA in the presence of TIS for 15 min.

Synthesis of Fmoc‐Ala‐Ser(Thp)‐Leu‐OH and Fmoc‐Ala‐Thr(Thp)‐Leu‐OH

Peptide syntheses were performed manually on 2‐CTC resin (50 mg, f=1.60 mmol g−1). Initially, the resin was activated overnight using thionyl chloride (10 % in CH2Cl2) and then washed with CH2Cl2 (2×5 mL). Attachment of the first amino acid was performed by treating the resin with Fmoc‐Leu‐OH (3 equiv.) and N,N‐diisopropylethylamine (10 equiv) in CH2Cl2, and allowing it to react for 60 min at 25 °C. Thereafter, the resin was capped by adding MeOH (10 equiv.) to the mixture, which was stirred for 30 min at 25 °C. The resin was then washed with CH2Cl2 (4×5 mL) and DMF (5×5 mL), and the Fmoc protecting group was removed by treating the resin with 20 % piperidine in DMF (2×10 mL, each 10 min), followed by washing with DMF (2×5 mL) and CH2Cl2 (2×5 mL).

The H‐Leu‐O‐2CTC resin was divided into two portions and swelled in CH2Cl2 (3×5 mL) and then DMF (3×5 mL). Fmoc‐Ser(Thp)‐OH (3 equiv.) was added to one portion and Fmoc‐Thr(Thp)‐OH (3 equiv.) was added to the other. Amino acids were coupled using N,N′‐diisopropylcarbodiimide (3 equiv.) and Oxyma Pure (3 equiv.) in DMF with a 3 min pre‐activation time for 1.5 h at 25 °C. The resins were washed with CH2Cl2 (4×5 mL) and DMF (2×5 mL). The Fmoc protecting group was removed by treating the resins with 20 % piperidine in DMF (2×10 mL, each 10 min), and then Fmoc‐Ala‐OH was incorporated as described above.

Cleavage Studies

For each cleavage study, samples of Fmoc‐Ala‐Xxx(Thp)‐Leu‐O‐2CTC resin (Xxx=Ser or Thr; 5 mg) were treated with mixtures of TFA/H2O/TIS/CH2Cl2 (500 μL) at different percentages (Table 2) at RT. The reaction was monitored by RP‐HPLC [linear gradient of H2O/MeCN (5:95) over 15 min] after 15, 30, and 60 min of treatment. After each interval, an aliquot of 20 μL was taken, and the solvent was then removed under a nitrogen stream and the residue re‐dissolved in MeCN (400 μL; Table 2).

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Thomas Bruckdorfer from Iris Biotech (Germany) for supporting this work and providing free samples of protected amino acids. This work was funded in part by the following: National Research Foundation (NRF) and the University of KwaZulu‐Natal (South Africa); the International Scientific Partnership Program (ISPP #0061) at King Saud University (Saudi Arabia); and MEC (CTQ2015‐67870‐P) and Generalitat de Catalunya (2014 SGR 137; Spain).

A. Sharma, I. Ramos-Tomillero, A. El-Faham, H. Rodríguez, B. G. de la Torre, F. Albericio, ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 206.

References

- 1. Merrifield R. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwieter K. E., Johnston J. N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14160–14169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thanka Christlet T. H., Veluraja K., Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 952–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slawson C., Hart G. W., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003, 13, 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sivanathan S., Scherkenbeck J., Molecules 2014, 19, 12368–12420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kitagaki J., Shi G., Miyauchi S., Murakami S., Yang Y., Anticancer Res. 2015, 26, 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amanda L., Kirby D., Lajoie G. A., in Solid-Phase Synthesis: A Practical Guide, (Eds.: S. A. Kates, F. Albericio), Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, Basel, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer P. M., Retson K. V., Tyler M. I., Howden M. E. H., Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1991, 38, 491–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reissmann S., Schwuchow C., Seyfarth L., De Castro L. F. P., Liebmann C., Paegelow I., Werner H., Stewart J. M., J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer P. M., Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 7605–7608. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Isidro-Llobet A., Álvarez M., Albericio F., Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2455–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barlos K., Gatos D., Koutsogianni S., Schäfer W., Stavropoulos G., Wenging Y., Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 471–474. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barlos K., Gatos D., Koutsogianni S., J. Pept. Res. 1998, 51, 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arzeno H. B., Bingenheimer W., Blanchette R., Morgans D. J., Robinson J., Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1993, 41, 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Boom J. H., Herschied J. D. M., Reese C. B., Synthesis 1973, 169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyashita M., Yoshikoshi A., Grieco P. A., J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 3772–3774. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greene T. W., Wuts P. G. M., Protective Groups in Organic Chemistry, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramos-Tomillero I., Rodríguez H., Albericio F., Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1680–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rastetter W. H., Erickson T. J., Venuti M. C., J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 5011–5012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rastetter W. H., Erickson T. J., Venuti M. C., J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 3579–3590. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olsen R. K., Ramasamy K., Bhat K. L., Low C. M. L., Waring M. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6032–6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nudelman A., Marcovici-Mizrahi D., Nudelman A., Flint D., Wittenbach V., Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 1731–1748. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan L., Ma D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3614–3617; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 3670–3673. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu X., Dai Y., Yang T., Gagné M. R., Gong H., Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krishnamoorthy R., Vazquez-Serrano L. D., Turk J. A., Kowalski J. A., Benson A. G., Breaux N. T., Lipton M. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 15392–15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iijima Y., Kimata O., Decharin S., Masui H., Hirose Y., Takahashi T., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5378–5378. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iselin B., Schwyzer R., Helv. Chim. Acta 1956, 39, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holden K. G., Mattson M. N., Cha K. H., Rapoport H., J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 5913–5918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. López-Macià À., Jiménez J. C., Royo M., Giralt E., Albericio F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11398–11401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pelay-Gimeno M., García-Ramos Y., Martin M. Jesús, Spengler J., Molina-Guijarro J. M., Munt S., Francesch A. M., Cuevas C., Tulla-Puche J., Albericio F., Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson L. A., Ellman J. A., Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 9333–9336. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh H., Wu Y., Chen S., Chem. Commun. 1998, 649–650. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary