Abstract

Neonatal gonocytes are direct precursors of spermatogonial stem cells, the cell pool that supports spermatogenesis. Although unipotent in vivo, gonocytes express pluripotency genes common with embryonic stem cells. Previously, we found that all-trans retinoic acid (RA) induced the expression of differentiation markers and a truncated form of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)β in rat gonocytes, as well as in F9 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells, an embryonic stem cell-surrogate that expresses somatic lineage markers in response to RA. The present study is focused on identifying the signaling pathways involved in RA-induced gonocyte and F9 cell differentiation. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) 1/2 activation was required during F9 cell differentiation towards somatic lineage, whereas its inhibition potentiated RA-induced Stra8 expression, suggesting that MEK1/2 acts as a lineage specification switch in F9 cells. In both cell types, RA increased the expression of the spermatogonial/premeiotic marker Stra8, which is in line with F9 cells being at a stage before somatic-germline lineage specification. Inhibiting PDGFR kinase activity reduced RA-induced Stra8 expression. Interestingly, RA increased the expression of PDGFRα variant forms in both cell types. Together, these results suggest a potential cross talk between RA and PDGFR signaling pathways in cell differentiation. RA receptor-α inhibition partially reduced RA effects on Stra8 in gonocytes, indicating that RA acts in part via RA receptor-α. RA-induced gonocyte differentiation was significantly reduced by inhibiting SRC (v-src avian sarcoma [Schmidt-Ruppin A-2] viral oncogene) and JAK2/STAT5 (Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5) activities, implying that these signaling molecules play a role in gonocyte differentiation. These results suggest that gonocyte and F9 cell differentiation is regulated via cross talk between RA and PDGFRs using different downstream pathways.

Male germ cell development in rodents and humans can be divided into 2 phases: a fetal-neonatal phase leading to spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) formation and a later phase ending with spermatozoa production (1). Neonatal gonocytes, direct precursors of SSCs, undergo proliferation, migration, and differentiation into spermatogonia, including SSCs and first wave type A spermatogonia (2–6). Alterations of human gonocyte development may lead to formation of carcinoma-in situ, precursor of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) (1, 7). Thus, understanding the mechanisms regulating gonocyte development could provide insight into the origins of human pathologies such as TGCTs and infertility.

We have shown that all-trans retinoic acid (RA) induces rat neonatal gonocytes differentiation, as reflected by increased expression of spermatogonial differentiation markers cKIT and STRA8 (stimulated by retinoic acid 8) (8), similarly to RA effects in spermatogonia (9). RA-induced STRA8 expression also occurs in F9 mouse embryonal teratocarcinoma cells, a tumor cell line used as embryonic stem cell (ESC) surrogate at a stage before somatic-germline lineage specification (10, 11). Interestingly, gonocytes share a number of pluripotency markers with ESCs (1, 7).

RA drives F9 cell differentiation along the somatic lineage, giving rise to cells with primitive or visceral endoderm characteristics or to parietal endoderm when cAMP is added with RA (12). However, the facts that F9 cells express STRA8, a spermatogonia and premeiotic germ cell marker (11, 13), and that they are a type of TGCTs suggest that they may have retained germ cell-specific genes and pathways present in the cells from which they originated, making them an interesting model to compare with gonocytes.

RA action is mediated by activation of nuclear RA receptors (RARs) (α, β, and γ) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs) (α, β, γ) (14). In classical pathway signaling, RARs and RXRs form homo- or heterodimers upon RA binding, which bind to RA-response elements (RAREs) allowing for conformational changes leading to the regulation of gene transcription (15). Nonclassical RAR activation can affect indirect targets via transcriptional intermediaries rather than RAREs (16). One such target is platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)α (16).

Activated PDGFRs and their downstream pathways play critical roles in various cellular processes (17). Transcripts for PDGF-A, PDGF-B, and their receptors are found in gestation day 18 testicular tissues and reach highest levels at postnatal day (PND)5, when expression begins to decline (18, 19). Rat neonatal gonocytes express both PDGFRα and PDGFRβ (20, 21) and proliferate in response to PDGF-BB and 17β-estradiol, via activation of the MAPK pathway (20, 22). These data suggest that the PDGFR pathway may directly regulate germ cell development.

In the present study, we demonstrated that both gonocytes and F9 cells express truncated forms of PDGFRα that may be involved in RA-induced differentiation but that these processes require the activation of different downstream pathways.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Newborn male Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories. Pups were euthanized according to protocols approved by the McGill University Health Centre Animal Care Committee.

Germ cell isolation

Gonocytes were isolated from PND3 rat testes using 30–40 pups per preparation, and spermatogonia were isolated from PND8 rat testes using 10 pups per preparation, as previously described (20–23). These cells were isolated by sequential enzymatic tissue dissociation and a 2%–4% BSA gradient to obtain samples of at least 85% purity.

Gonocyte culture

Gonocytes were cultured in supplemented RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen) at 37°C and 3.5% CO2. Cells were treated with either control medium or RA (10−6M) (Sigma) for 24 hours (mRNA analysis) and 72 hours (protein analysis) containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were treated with the following inhibitors (Supplemental Table 1), alone or with RA, for the full-length of treatment: AG370, U73122, U0126, Wortmannin, SU6656, Dasatinib, AG490, Stattic, Pimozide, farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), NSC23766, BMS195614, and Cathepsin L inhibitor I. Protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were added at the end of the incubations before cell collection. Cells were pelleted and either frozen for mRNA and protein analysis or collected on cytospin slides.

F9 cell culture

F9 cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen) at 37°C and 5.0% CO2. Cells were plated on day 1 and treated on day 2, upon adherence to culture dishes. Cell treatments were the same as above, except that RA was used at 10−7M and F9 cells were also treated with AG1295 (Supplemental Table 1).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

As previously described, total RNA was extracted from cell pellets (and whole testes) using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus) and digested with deoxyribonuclease I (QIAGEN) (24). cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the single strand cDNA transcriptor synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics).

Northern blot analysis

RNA samples were separated on agarose gel and mRNA transferred to nylon membrane (8, 25). The membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled PDGFRα cDNA probe (Promega) recognizing the C terminus of rat wild-type PDGFRα (accession number NM_012801; region, bp 1907–2417). The blot was imaged using the LAS-4000 gel documentation system (Fujifilm). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

qPCR analysis was performed using a LightCycler 480 with a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Roche Diagnostics). Gene-specific primers were designed using Roche primer design software (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). qPCR cycling conditions: initial step at 95°C followed by 45 cycles at 95°C (10 s), 61°C (10 s), and 72°C (10 s). 18S rRNA was used for normalization.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) ELISA measurement

F9 cells were treated with various concentrations of PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB (Sigma) for 24 hours. BrdU was added in the culture medium 6 hours before ELISA was performed. The cells were fixed to denature BrdU-labeled DNA (Invitrogen) and incubated with peroxidase-coupled anti-BrdU antibody, followed by a colorimetric reaction with tetramethyl-benzidine (Invitrogen). Data were expressed as differences between absorbance at 450 nm and reference 690 nm.

Immunoblot analysis

Samples were solubilized in Laemmli buffer. Proteins were separated on 4%–20% tris-glycine gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% milk, membranes were probed with primary and secondary antibodies to determine protein expression (Supplemental Table 4) (24). Immunoblots were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) and LAS-4000 gel documentation system. Tubulin or GAPDH were used as loading references. Protein levels were quantified using MultiGauge V3.0 program (Fujifilm).

Immunohistochemistry/immunocytochemistry

As previously described (26), tissue section slides were dewaxed and rehydrated using Citrosolv (Fisher Scientific) and Trilogy solution (Cell Marque IVD). Cytospin slides did not require dewaxing. After treatment with DAKO Target Retrieval solution, slides were blocked using PBS containing goat serum (Vector Laboratories), BSA, and Triton X-100 for 1 hour (24). The slides were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS, BSA, and Triton X-100 (Supplemental Table 5) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, treated with streptavidin-peroxidase, AEC (Invitrogen), counterstained with hematoxylin, and viewed using a BX40 Olympus microscope.

Immunoprecipitation

F9 cells were treated with or without RA for 72 hours, collected, and proteins extracted using a premade extraction buffer (Invitrogen Dynabeads coimmunoprecipitation kit). PDGFRα antibody (Upstate/Millipore, 07-276; lot number 30083) was coupled to Dynabeads during an overnight incubation. Antibody coupled-Dynabeads were mixed with total cell lysates and incubated for 60 minutes at 4°C. The beads were collected by magnetic separation and protein complexes recovered using elution buffers.

Mass spectrometry

Protein spots of interest underwent an in-gel digestion procedure as previously described (27). The digests were desalted using C18 Zip Tips (Millipore) and analyzed by nano-flow reversed phase liquid chromatography (LC) using the Agilent 1100 LC system (Agilent Technologies). This was coupled to a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (MS) (Thermo Scientific). The resulting spectra were searched against a nonredundant human protein database using SEQUEST (Thermo Scientific), and results were tabulated for each identified peptide/protein using searching criteria reported previously (28).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tail Student's t test or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's correction using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 program (GraphPad). All experiments were performed with n equal to a minimum of 3 independent experiments. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PDGF signaling is involved in RA-induced differentiation and proliferation in F9 cells

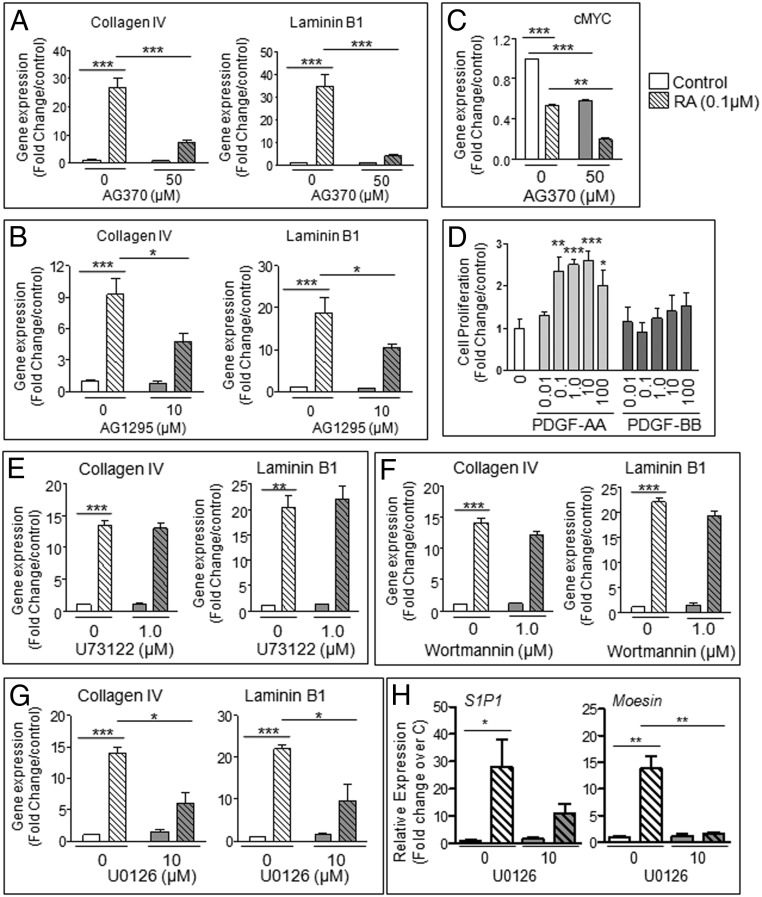

To investigate whether PDGF signaling is involved in RA-induced F9 cell differentiation, we used AG370, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, at a concentration specific for PDGFR (29). After 72 hours of RA treatment, there was a significant increase in Collagen IV and Laminin B1 mRNAs markers of F9 cell differentiation to endoderm (8, 30, 31), which was inhibited by AG370 (Figure 1A). Similar results were seen with another PDGFR-specific inhibitor, AG1295 (Figure 1B) (32). Moreover, both RA stimulation and PDGFR inhibition by AG370 induced significant decreases in cMyc expression in F9 cells, and the combination of RA and AG370 exacerbated the effect of each compound, lowering cMyc levels to 20% of control (Figure 1C). Furthermore, F9 cell proliferation was significantly increased by PDGF-AA and not PDGF-BB (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Effects of PDGFR signaling pathways inhibitors on F9 cell differentiation.

F9 cells were treated for 72 hours with 0.1μM RA and the indicated inhibitors, alone or in combination with RA. A and B, mRNA levels of 2 differentiation markers of somatic lineage differentiation (Collagen IV and Laminin B1) were quantified using qPCR analysis for F9 cells treated with or without RA and the PDGFR kinase inhibitors AG370 and AG1295. C, mRNA levels of cMYC were quantified for F9 cells treated with or without RA and AG370. D, Levels of F9 cell proliferation in response to varying concentrations of PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB were determined using a BrdU ELISA proliferation assay. E–G, Effects of PLCγ inhibition (U73122), PI3K inhibition (Wortmannin), and MEK1/2 inhibition (U0126) on RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells. H, The mRNA levels of the primitive endoderm markers S1P1 and Moesin were quantified by qPCR analysis. Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001).

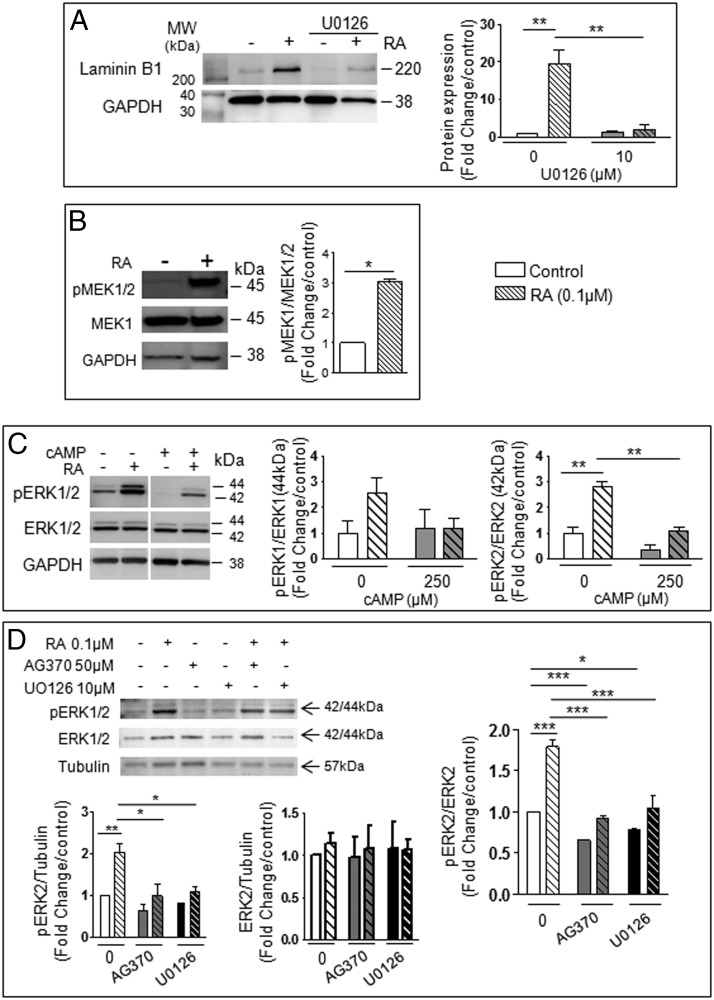

We then examined which pathway was cross talking with RA by testing inhibitors of common downstream effectors of PDGFR activation, including phospholipase C (PLC) γ and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathways (33–36). The PLC inhibitor U73122 (36) and PI3K inhibitor Wortmannin (33) had no effects on RA-induced increases of Collagen IV and Laminin B1 (Figure 1, E and F), indicating that PLCγ and PI3K pathways are not involved in RA-induced differentiation. Another signaling pathway regulated by PDGF is the Raf (Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma)/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/ERK cascade. The MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (37) significantly reduced the RA-induced increases of Collagen IV and Laminin B1 in F9 cells (Figure 1G). qPCR analysis also showed that the primitive endoderm markers sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) and Moesin were increased by RA and that U0126 significantly suppressed the increase in Moesin, while showing an inhibitory trend for S1P1 (Figure 1H) (38, 39). The mRNA of parietal endoderm marker Thrombomodulin (40) was not detected in control and RA-treated cells (data not shown). Protein analysis of Laminin B1 confirmed the mRNA findings (Figure 2A). MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 activation was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 2, B and C). By contrast, ERK1/2 was not activated by a combination of RA and 8-bromo-cAMP, known to drive parietal endoderm development (Figure 2C). The RA-induced increase in phospho-ERK2 levels was suppressed both by AG370 and U0126 (Figure 2D), indicating that RA cross talks with the PDGFR pathway via ERK2 activation in F9 cells. Taken together, these data support the role of MEK/ERK activation in RA-induced F9 cell differentiation to primitive endoderm.

Figure 2. RA-induced somatic differentiation in F9 cells requires ERK1/2 pathway activation.

F9 cells were treated for 72 hours with 0.1μM RA, 50μM AG370, 10μM U0126, and 250μM cAMP alone or in the different combinations indicated. The proteins were examined by immunoblot analysis, signal intensity analysis of immunoreactive bands was quantified by densitometry, and the results were normalized against GAPDH or tubulin levels (loading control). A, Protein levels of Laminin B1 in F9 cells treated with or without RA and U0126. B, Immunoblot and quantitative analysis of MEK1/2 phosphorylation levels relative to total MEK1 expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA. C, Immunoblot and quantitative analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels relative to total ERK1/2 expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA and cAMP. D, Immunoblot and quantitative analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels relative to total ERK1/2 expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA, AG370, and U0126. The results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001).

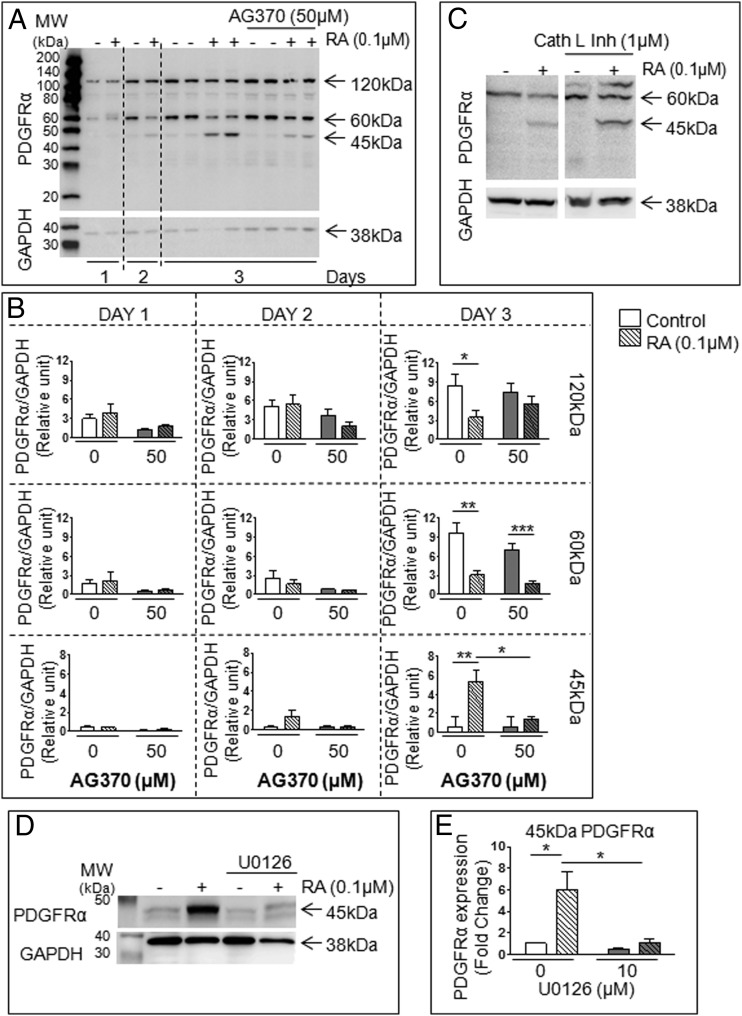

A PDGFRα variant protein is expressed in RA-induced differentiating F9 cells

In view of our previous finding that RA induces a time-dependent increase in PDGFRα transcript in F9 cells (8), we examined PDGFRα protein expression in RA-treated F9 cells. F9 cells not only expressed the full-length (120 kDa) PDGFRα form but 2 variant forms of 60 and 45 kDa (Figure 3, A and B). Expression levels of the 45-kDa variant were significantly increased upon RA stimulation of F9 cells in a time-dependent manner, in agreement with previous mRNA results. Moreover, this effect was significantly reduced by AG370. Protein expression of the 120- and 60-kDa bands was decreased in RA-treated F9 cells, and addition of AG370 had no effect. We then examined whether the 45-kDa band could be a proteolytic product from the larger size bands by treating F9 cells with a cell-permeable inhibitor of Cathepsin L, a protease activated by PDGFs (41, 42), alone or with RA. There was no change in PDGFRα variant expression (Figure 3C), suggesting that the variant was not formed by proteolysis, although the action of another protease cannot be excluded. Addition of U0126 together with RA prevented the formation of the 45-kDa variant (Figure 3, D and E), indicating that MEK1/2 activation is required for the RA induction of this variant in F9 cells.

Figure 3. RA-dependent formation of a 45-kDa variant PDGFRα in F9 cells requires MEK1/2 activation.

RA induces the formation of truncated forms of PDGFRα in differentiating F9 cells, which are dependent on PDGFR and MEK1/2 activation. F9 cells were treated for 72 hours with or without RA and AG370. A, Representative immunoblot shown of results obtained for PDGFRα expression in RA-treated F9 cells with or without AG370 treatment. B, Signal density analysis of the immunoblot in A was performed. Results were normalized to GAPDH (loading control). C, Immunoblot analysis of F9 cells treated for 72 hours with or without RA and Cathepsin L inhibitor I. Representative blot shown. D and E, Representative immunoblot shown alongside signal density analysis of the 45-kDa variant PDGFRα expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA and the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126. Results were normalized to GAPDH (loading control). Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001).

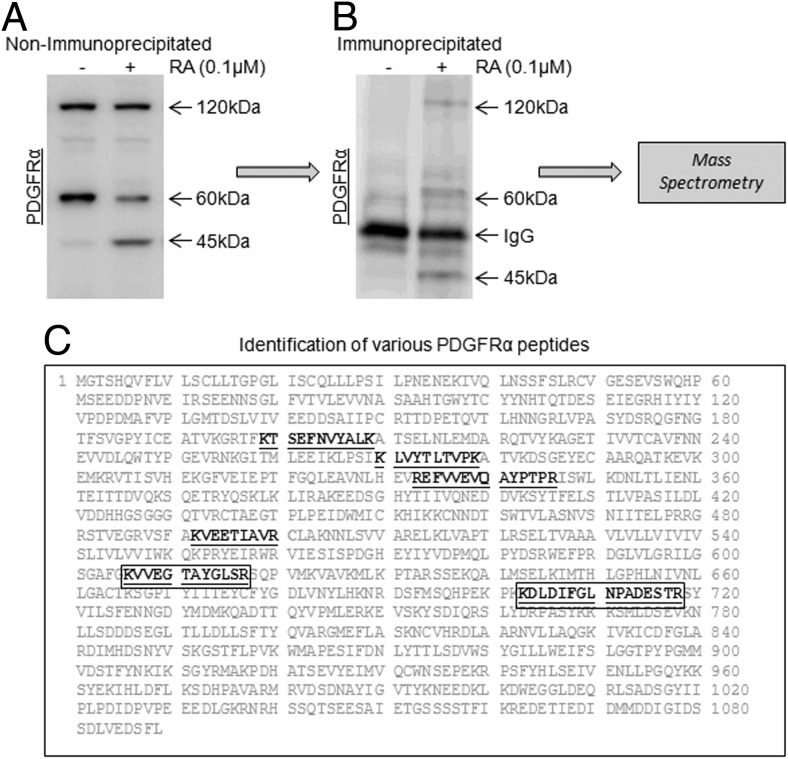

To confirm the identity of the full-length and variant bands as PDGFRα, we performed LC-MS analysis of bands enriched by immunoprecipitation. This analysis resulted in unambiguous identification of PDGFRα peptides corresponding to 120, 60, and 45 kDa (Figure 4). Tryptic peptides identified from the 120-kDa full-length protein-band covered evenly the PDGFRα sequence, whereas the 60- and 45-kDa bands contained sequences located toward the C terminus, including a peptide coded by a sequence in exon 12, suggesting the absence/truncation of the N-terminal region in the 60- and 45-kDa variants (Figure 4, A–C).

Figure 4. Confirmation of F9 cell PDGFRα proteins identity by LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS analysis of variant PDGFRα expression in RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells. F9 cells were treated for 72 hours with or without 0.1μM RA. A, Immunoblot analysis of PDGFRα in F9 cells treated with or without RA, nonimmunoprecipitated. B, Immunoblot analysis of PDGFRα in F9 cells treated with or without RA, immunoprecipitated. C, LC-MS analysis of immunoprecipitated bands of interest and the position/coverage of the identified peptides within the sequence of intact PDGFRα protein.

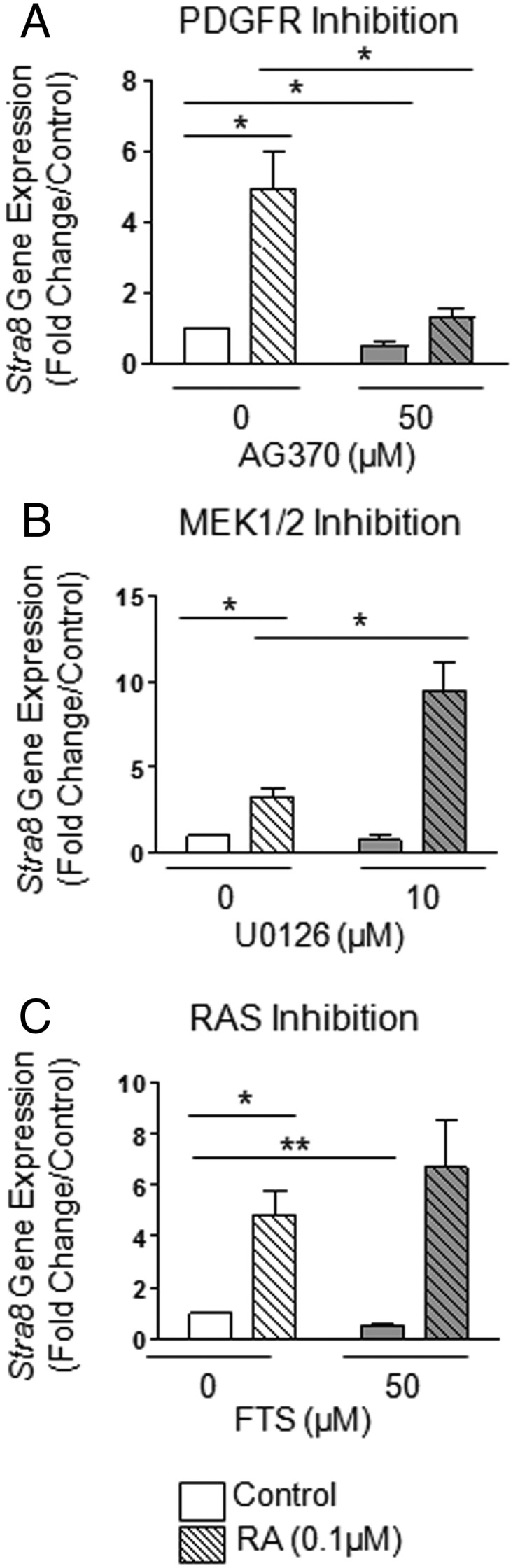

MEK/ERK1/2 inhibition promotes RA-induced expression of Stra8 in F9 cells

Given that F9 cells are known to express increasing levels of the germline marker Stra8 upon RA treatment (8, 13), we examined the effects of several PDGFR pathway inhibitors on RA-induced Stra8 expression in these cells. Interestingly, the simultaneous addition of a PDGFR kinase inhibitor with RA prevented the increase of Stra8 normally induced by RA (Figure 5A). Inhibitors of SRC (v-src avian sarcoma [Schmidt-Ruppin A-2] viral oncogene), RAC1, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), PLCγ, and PI3K had no effect on Stra8 induction by RA (data not shown). By contrast, the addition of the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 to RA doubled the increase of Stra8 expression observed with RA alone (Figure 5B), whereas cotreatment with the rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (RAS) inhibitor FTS showed an increasing trend in Stra8 expression (Figure 5C), suggesting that inhibition of MEK/ERK1/2 promotes the expression of germline-specific genes in RA-treated F9 cells.

Figure 5. The RA-induced expression of Stra8 in F9 cells requires PDGFR activation and is potentiated by MEK1/2 inhibition.

RA cross talk with several PDGFR-related signaling pathways in differentiating F9 cells. F9 cells were treated for 72 hours with or without 0.1μM RA and a variety of different inhibitors. A, mRNA levels of STRA8 gene expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA and AG370. B, mRNA levels of STRA8 gene expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA and MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126. C, mRNA levels of STRA8 gene expression in F9 cells treated with or without RA and RAS inhibitor FTS. Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; **, P < .01).

PND3 gonocytes express an RA-induced variant form of PDGFRα

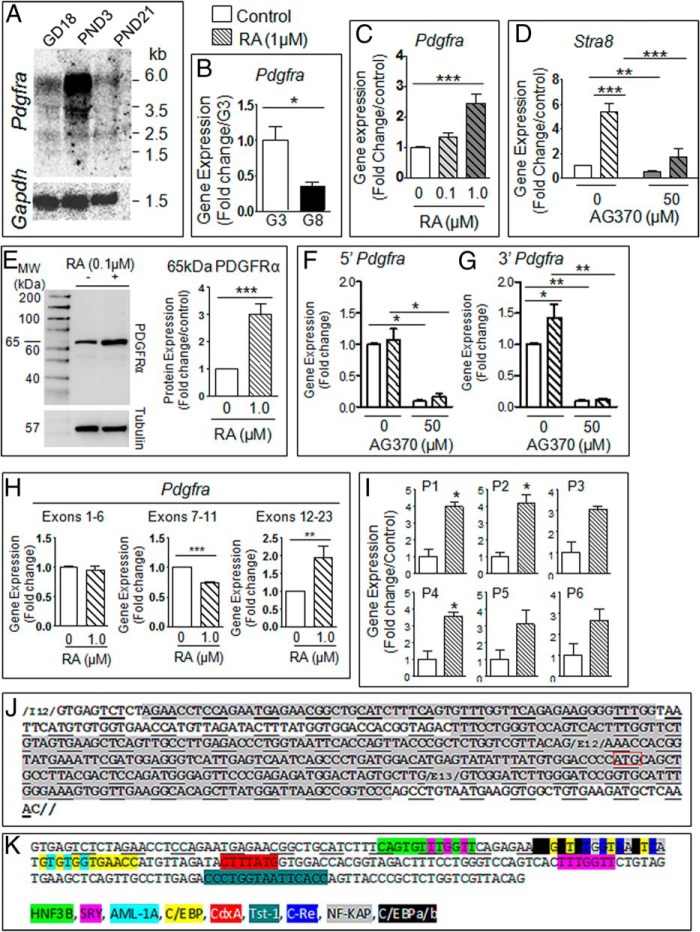

We examined whether neonatal gonocytes also express variant forms of PDGFRα in response to RA. First, Northern blot analysis revealed that PND3 testes express not only the full-length Pdgfrα transcript (6 kb) but also 3 shorter transcripts of 3.5, 2.5, and 1.5 kb, respectively (Figure 6A). Of interest, Pdgfrα transcripts were much more abundant at PND3 than in gestational day 18 and prepubertal (PND21) testes, suggesting a preferential role for PDGFRα species in neonatal testis. Also, PND3 gonocytes expressed much higher levels of Pdgfrα mRNA than PND8 spermatogonia, both in the N- and C-terminal regions of the transcript (Figure 6B and data not shown). Pdgfrα mRNA was increased in a concentration-dependent manner in RA-treated gonocytes (Figure 6C), simultaneously to Stra8 (Figure 6D). Like in F9 cells, AG370 significantly decreased the induction of Stra8 expression in response to RA (Figure 6D). These results suggest that PDGFRα is a target of RA and that both pathways cross talk to induce gonocyte differentiation.

Figure 6. RA induces the expression of a PDGFRα variant form in PND3 gonocytes.

A, Northern blot analysis of PDGFRα expression in gestational day 18, PND3, and PND21 whole rat testes. GAPDH used as loading control. B, mRNA levels of PDGFRα in PND3 gonocytes (G3) compared with levels in PND8 spermatogonia (G8) using primers specific to the 3′-end of the PDGFRα sequence. C, mRNA levels of PDGFRα in gonocytes treated with RA in a concentration-dependent manner. D, mRNA levels of STRA8 gene expression in gonocytes treated for 24 hours with or without RA and AG370. E, Immunoblot and signal density analysis of PDGFRα expression of gonocytes treated with RA for 72 hours. F and G, mRNA levels of PDGFRα in gonocytes treated with or without RA, specifically aimed at the 5′ (F) (exon 3) and 3′ (G) (exon 21) ends of the PDGFRα sequence. H, mRNA levels of PDGFRα in gonocytes treated with or without RA examined for all exons. Expression grouped by exon-specific areas of the PDGFRα sequence. qPCR analysis was performed for each exon separately, and the data were further pooled to cover 3 main areas, the 5′ end, central exons, and 3′-end of the sequence. I, a similar approach was used to determine the expression levels of 6 sequences located in intron 12, exons 12 and 13, in control and RA-treated gonocytes. J, Representation of intron 12 to exon 13 rat sequences showing in gray shading the regions that were examined and found to be increased by RA treatment. Red box, potential ATG start codon. K, Representation of predicted TF binding sites in rat intron 12 of PDGFRa. Results shown in B–H represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition. Data in I are from 2 independent experiments (*, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001).

We then analyzed PDGFRα protein expression profiles in neonatal gonocytes by immunoblot analysis. There was very little to none full-length PDGFRα (120 kDa) expressed in gonocytes in function of the cell preparation (Figure 6E). However, gonocytes expressed a 65-kDa PDGFRα variant form that was significantly increased upon RA treatment (Figure 6E). The specificity of the 65-kDa band was verified by preincubating the PDGFRα antibody with the peptide it was raised against (data not shown). The formation of this variant was not altered by treatment with Cathepsin L inhibitor I (data not shown), similarly to F9 cells, suggesting that the variant was not a Cathepsin L-mediated proteolytic product.

These data, together with the existence of variant Pdgfrα transcripts observed in Northern blottings, suggested that a variant transcript of Pdgfrα is formed in RA-induced gonocytes, similarly to F9 cells. We examined the differential Pdgfrα exon profiles of control and RA-treated gonocytes by qPCR analysis, using primer sets of comparable efficiencies targeting either the 5′ and 3′ sequences. The finding that there was an increase in Pdgfrα expression in RA-treated gonocytes in the 3′-end of Pdgfrα (target sequence in exon 21), but not the 5′-end (target sequence in exon 3), suggested that the variant mRNA contains the 3′-end but not the 5′-end of the sequence (Figure 6, F and G). RA-induced increase in the 3′-end of Pdgfrα was prevented by the addition of AG370 (Figure 6G). The basal levels of the 5′- and 3′-ends of Pdgfrα were also decreased by AG370 (Figure 6, F and G). A better determination of the overexpressed sequence was achieved by using 41 specific overlapping primer sets covering the entire mRNA sequence (Supplemental Table 3) (Figure 6H). The study showed that there was no significant change in Pdgfrα expression in the areas covering exons 1–6 between control and RA-treated gonocytes (Figure 6H, left panel), but significantly decreased expression in RA-treated cells in comparison with untreated cells in exons 7–11 (Figure 6H, middle panel), and a significant 2-fold increase in RA-treated gonocytes in exons 12–23 (Figure 6H, right panel). These results suggest that gonocyte Pdgfrα variant contains exons 12–23 and may be lacking an internal sequence containing exons 7–11. These results revealed that the novel Pdgfrα variant in gonocytes likely contains the 3′-end of the full-length sequence (see diagram in Supplemental Figure 1).

Because the human PDGFRa variant found in seminomas was shown to be expressed via an alternative promoter located in a retained sequence of intron 12 (43), we extended the comparative analysis of control and RA-treated gonocytes transcripts to include intron 12 sequence. qPCR primer sets were designed against 5′, 3′, and centrally located areas of rat intron 12, and others against exon 12, and exon 12 and 13 overlapping regions (Supplemental Table 3). Interestingly, there was a 2-fold significant increased expression of intron 12 sequences, some samples showing increasing trends, in RA-treated cells compared with controls (Figure 6, I and J). Exons 12 had an ATG codon in both rat and mouse (rat sequence in Figure 6J). Rat intron 12 contained several transcription factor (TF) predicted binding sites, including those of TST-1 (Testes-1, also called POU3F1, octamer-binding transcription factor 6 [OCT6], or SCIP), SRY (Sex-determining region Y), HNF-3B (hepatocyte nuclear factor 3-beta, also called FOXA2 [Forkhead box protein A]), C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein), and NF-KAP/c-Rel (v-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene; c-Rel is a subunit of NF-κB) (Figure 6K). Mouse intron 12 contained the same TF predicted sites, with the exception of TST-1 and HNF-3B. This suggests that one of these TFs could potentially activate an alternative promoter located in intron 12 retained sequence.

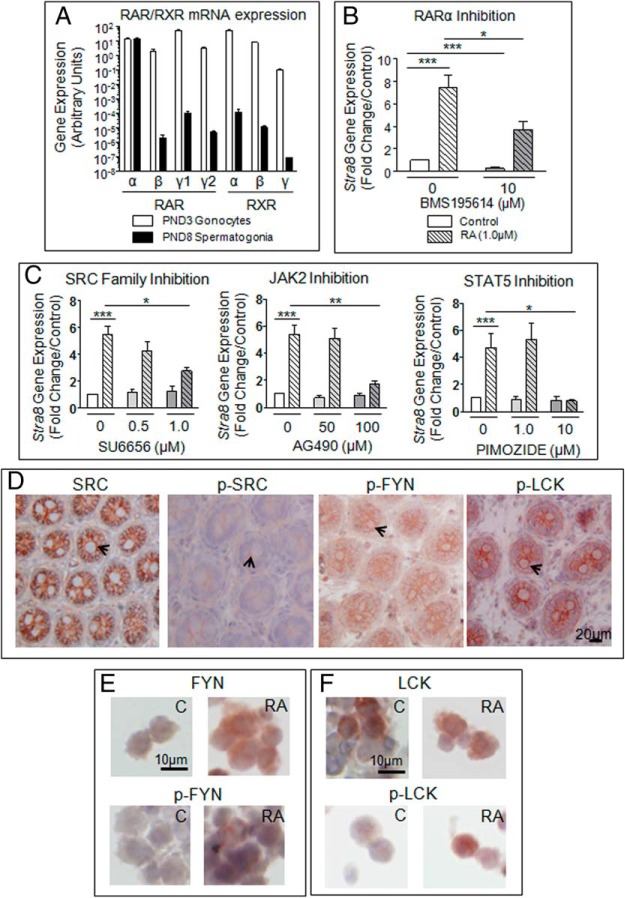

Gonocyte differentiation involves RARa and requires the activation of SRC and JAK2/STAT5 pathways

Considering conflicting reports on the nature of RAR and RXR expressed in gonocytes (44, 45), we verified which receptor(s) was involved in rat PND3 gonocyte differentiation. qPCR analysis showed that Rarα, Rarγ1, and Rarγ2 were highly expressed in PND3 gonocytes (Figure 7A). When isolated gonocytes were treated with BMS195614, a specific RARα antagonist (46), simultaneously to RA, the RA-dependent induction of Stra8 expression was significantly reduced compared with RA alone, indicating that RARα activation is involved in gonocyte differentiation (Figure 7B). However, Stra8 expression was only partially reduced by the RARα antagonist, suggesting the involvement of other receptors.

Figure 7. Identification of RAR and signaling pathways involved in RA-induced gonocytes differentiation.

A, qPCR quantification b of RARs and RXRs transcripts expressed in PND3 gonocytes and PND8 spermatogonia, B, Effect of the RARα inhibitor BMS195614 on the RA-induced increase in Stra8 mRNA expression in gonocytes treated for 24 hours. Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; ***, P < .001). C, Effects of SRC, JAK2, and STAT5 inhibitors on Stra8 expression. Gonocytes were treated for 24 hours with or without 1.0μM RA and/or the inhibitors SU6656 (SRC family of kinases), AG490 (JAK2), or Pimozide (STAT5). Stra8 mRNA levels were measured by qPCR. Results shown represent the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments for each condition (*, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001). D–F, Immunohistochemical (D) and immunocytochemical (E and F) analyses of protein expression levels (native and phosphorylated forms) of the SRC kinase family members SRC, FYN, and LCK in PND3 testes (D) and isolated PND3 gonocytes treated with or without RA (E and F). Representative images shown.

We next examined which intracellular signaling pathway was involved in gonocyte differentiation. We performed gene array, qPCR, and immunohistochemical analyses of isolated gonocytes and PND3 testes sections to verify which of the common PDGFR downstream signaling pathways were present in gonocytes (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis was also performed (Supplemental Figure 2), in which all the proteins were expressed at variable levels.

Because there was no true dominant pathway from protein and gene expression screening, we examined the effects of a panel of inhibitors on RA-induced Stra8 expression used as a differentiation marker, similarly to what was done with F9 cells (Supplemental Table 1). SU6656 (Figure 7C) and Dasatinib (47; data not shown) inhibitors for the SRC family of kinases, AG490 (JAK2 inhibitor) and Pimozide (STAT5 inhibitor) significantly reduced RA-induced Stra8 expression in gonocytes (Figure 7C). These results indicated that PDGFR, a member of the SRC family, and JAK2/STAT5 pathways participate in gonocyte differentiation by cross talking with RA, which itself acts on RARα.

In an effort to identify which of the SRC proteins is involved in this process, we examined the phosphorylation levels of several of them by immunohistochemistry, providing an indication of basal expression and activation of these proteins in gonocytes in situ, as well as in gonocytes treated in vitro with RA. SRC and its various family members (BLK [B lymphoid tyrosine kinase], FGR [Gardner-Rasheed feline sarcoma viral (v-fgr) oncogene homolog, FYN [proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase FYN], HCK [hemopoietic cell kinase], LCK [lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase], LYN [v-yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral related oncogene homolog], and YES [Yamaguchi sarcoma viral (v-yes) oncogene homolog]) (48) and their phosphorylated forms were all present at various levels in PND3 gonocytes, located at the plasma membrane for all except FYN (data not shown). In PND3 testes, FYN and LCK were the most highly phosphorylated (Figure 7D). A larger number of RA-treated gonocytes appeared to express FYN and phospho-FYN than untreated cells (Figure 7E). The protein showing the most difference between control and RA-treated gonocytes was LCK, expressed in a high proportion of cells in both conditions, but showed more phospho-LCK-positive cells in RA-treated samples (Figure 7F). These data suggest that the 3 proteins are active in gonocytes but that the LCK activation pattern better correlates with differentiation.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to identify and compare the signaling pathways interacting with RA to regulate cell differentiation in F9 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells, pluripotent testicular cancer cells behaving like ESCs, and in neonatal rat gonocytes, unipotent cells that have retained a number of pluripotency genes and give rise to the germline stem cells. We showed that in both cell types, RA-driven induction of differentiation requires the activation of PDGFRs, whereas different downstream signaling cascades are activated during their differentiation process. Furthermore, we identified novel variant forms of PDGFRα in both cell types that were up-regulated during cell differentiation.

We first demonstrated PDGFR participation in the RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells into primitive endoderm-type cells by showing that inhibiting PDGFR kinase activity significantly decreased the RA-induced expression of primitive endoderm markers. The multifaceted roles of PDGFRs in F9 cells was shown by the ability of F9 cells to proliferate in response to PDGF-AA, reminiscent of the ability of PDGF-BB to induce gonocyte proliferation in conjunction with estrogens (20, 22). PDGFR inhibition by AG370 reduced the expression of cMyc, a PDGF-regulated oncogene known for its involvement in cellular growth, tumor progression, and cellular transformation (49, 50). cMyc expression was also decreased by RA, in agreement with another study (49), an effect further exacerbated by cotreatment with AG370, suggesting that cMyc expression is regulated by PDGF in proliferating F9 cells and that RA decreases cMyc in order to prevent proliferation during RA-induced differentiation, as both processes cannot occur simultaneously. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the necessary activation of PDGFR in RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells.

The analysis of downstream pathways showed that PI3K inhibition did not alter the RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells. This is different from the biphasic effect of RA observed by Bastien et al (51), who reported an early PI3K-dependent activation and late inhibition of protein kinase B (AKT) activity via RARγ activation. This difference could be due to the different inhibitors, culture conditions, and treatment time periods used. We show that the inhibition of MEK1/2 interfered with the RA-dependent induction of primitive endoderm genes. The concomitant phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and ERK2 upon RA treatment of F9 cells was further confirmed, establishing a link between PDGFR pathway and these downstream molecules. The involvement of PDGF signaling in cell differentiation through the MEK/ERK-dependent pathway has been reported in the induction of neural stem cell differentiation to oligodendrocyte precursors by neurotrophin 3 (52). This study also reported that the expression of PDGFRα was dramatically increased during neurotrophin 3-induced differentiation of neural stem cells, and this increase could be suppressed by MEK inhibitor U0126 together with the inhibition of differentiation (52). These observations further indicated that the activation of ERK can regulate the expression of PDGFRα. In view of our data, we propose that PDGFR might be the upstream regulator of the MEK/ERK pathway in RA-induced differentiation of F9 cells toward the somatic lineage.

The significant increase of a 45-kDa variant PDGFRα in F9 cells upon RA treatment is a novel finding, although the presence of PDGFRα in F9 cells has previously been reported. Mercola et al (53) have previously shown that undifferentiated F9 cells do not express PDGFRs in the absence of RA, but upon RA stimulation, there is increased expression of both PDGFRα and PDGFRβ. In our studies, we cultured the cells under a constant basal level of RA present in the FBS, and thus, even under control conditions, there was expression of a small amount of full-length and 60-kDa PDGFRα. However, the up-regulation of the variant 45-kDa PDGFRα required additional RA, was time dependent, and prevented by MEK1/2 inhibition, similarly to the 4 differentiation markers examined. Taken together with studies reporting that RAS/ERK activation prevents parietal endoderm formation from primitive endoderm in differentiating F9 cells (54), these results suggest that the cross talk observed between RA, PDGFR, and MEK/ERK activation might be related to the differentiation of F9 cells toward primitive endoderm.

Although F9 cells, by default, will differentiate towards the somatic cell lineage, they do have the capability of expressing genes representative of the germline lineage, such as Stra8. This is in agreement with these cells being derived from carcinoma-in situ as a result of failed germ cell development, and with their similarity with ESCs at a stage before lineage specification. Our present finding that the RA-dependent up-regulation of Stra8 expression is reduced by PDGFR inhibitors suggests that the RA-driven expression of germline marker in ESCs might involve PDGFR activation, similarly to somatic lineage differentiation. However, it is possible that different PDGFRs are involved in these 2 processes, a question that cannot be answered at present. Our study unveiled a major difference in the regulation of the 2 fates, where MEK1/2 played opposite roles. Indeed, although MEK1/2 activation was needed for the RA-induced up-regulation of somatic markers, its inhibition potentiated RA induction of Stra8 expression, implying that MEK1/2 acts as a switch between RA-induced differentiation towards the somatic or germline lineages. Although our study is the first to report MEK1/2 as a potential switch in determining F9 cell differentiation lineage fate, the role of MEK1/2 in determining cell lineage and acting as a “switch” has been seen in the cluster of differentiation (CD) 4/CD8 lineage commitment of thymocytes where MEK1/2 and calcineurin inhibition will help determine whether thymocytes undergo CD4 or CD8 lineage commitment (55).

We then examined whether similar cross talks existed in neonatal differentiating gonocytes. First, using BMS195614, a specific RARα inhibitor (46), we showed that RARα activation played a role in the RA-dependent up-regulation of Stra8 expression during gonocyte differentiation. However, the finding that RARα inhibition only partially blocked Stra8 expression suggests that another receptor might play a role, such as RARγ, the other RAR strongly expressed in gonocytes. Concurrent with increased Stra8 expression, RA-treated gonocytes also presented significant increases in PDGFRα expression. Interestingly, protein as well as exon-based mRNA expression analyses showed that RA significantly up-regulated the expression of a variant form of PDGFRα in gonocytes, comprising the C terminus of the protein, similarly to the RA-induced variant found in F9 cells. Results showing the inhibition of basal PDGFRα levels in both 5′ and 3′ sequences, likely corresponding to the full-length receptor, as well as blocking of RA-induced increase of the 3′ variant by AG370 suggest that the expression of both full-length and variant forms depend on PDGFR activation. At present, it is not clear which forms of PDGFRs are exerting these effects. The presence of a variant Pdgfrα transcript in gonocytes was supported by Northern blot analysis revealing the presence of 3 variant transcripts besides full-length Pdgfrα in rat testes, more abundantly expressed at PND3, suggesting an age- and/or cell stage-specific function. The existence of such Pdgfrα variant in neonatal germ cells is quite striking in view of the characterization of a 1.5-kb variant Pdgfrα mRNA in human seminoma patients (43, 56). Thus, the existence of a variant PDGFRα in both testicular tumors and gonocytes, their proposed cell of origin, brings to mind the possibility that retention of such variant might be linked to the failure of differentiation and TGCT formation.

This study reports the presence of a PDGFRα variant in PND3 rat gonocytes. Basciani et al (57) have previously performed Northern blot analysis of Pdgfrα gene expression in human 16- to 28-week-old fetal and adult testes where they did not detect Pdgfrα variant expression. In view of our finding that fetal rat testes express much less variant and full-length Pdgfrα transcripts than neonatal testes, it is possible that variant forms were not expressed yet, or were not in sufficient amounts to be detected in the human fetal combined ages used in the study. Their absence in normal adult testes was not surprising, because the Pdgfrα variant found in human seminoma is specific only to tumors (56).

Considering the requirement for a tightly regulated action of RA in time and space in the context of organogenesis and cell differentiation, the involvement of cross talks with other signaling pathways is not surprising (58), because it would provide ways for fine local tuning of cell responses to RA. Studies originally done in F9 cells and ESCs using high-throughput methods have revealed that RA can activate over 300 genes that have, in some way, been correlated to differentiation (14). However, a large portion of these genes are actually targeted independently of RA-induced RARs binding to their response elements. Such a process has been observed in the cross talk between fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and RA, where there is an initial rapid RA-induced induction of FGF8 (which contains RAREs), followed by a long-term FGF4 repression, which results in ESC neuronal differentiation (14, 59). Although FGF8 contains RAREs, FGF4 does not, and thus, the repression seen in FGF4 is indirect and has been proposed to be due to upstream repression of the TF octamer-binding transcription factor 4 [OCT4] (14, 60).

Downstream pathway analysis using specific inhibitors against different signaling molecules revealed that inhibition of the SRC family of kinases, JAK2 and STAT5 significantly reduced RA-induced gonocyte differentiation. SU6656 is a SRC family inhibitor shown to prevent PDGF-induced mitogenesis (61) and Dasatinib, a second generation receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (62), are commonly used to study the role of SRC family members in PDGF-induced signaling pathways. Taken together, the relative abundance and phosphorylation status of FYN and LCK in comparison with other SRC family members in gonocytes, suggest that they likely play a role in gonocyte development, but additional studies are needed for confirmation. JAK2 inhibitor AG490 was also shown to inhibit STAT3, a downstream element of JAK2 pathway (63), whereas the STAT5 inhibitor Pimozide specifically inhibits STAT5 phosphorylation (64). Taken together, our data suggest that these 3 downstream pathways are involved in gonocyte differentiation.

It is not surprising to find that there is more than 1 downstream pathway activated during gonocyte differentiation, due to the common overlap seen among these pathways, and that most elements downstream of PDGFR can interact with each other. For example, although it is commonly known that JAK proteins activate STAT proteins, studies using megakaryocyte progenitors have shown that both JAK2 and SRC can activate STAT5 and increase STAT5 signaling (65). Thus, both JAK2 and SRC have the capability of activating STAT5. Given the complexity by which cell differentiation occurs, it is likely that the PDGFR pathway is not the only pathway activated during this process. Although PDGFR inhibition had the same consequences as SRC family and JAK2/STAT5 inhibition in gonocytes, at present, one cannot exclude that these pathways are downstream of another signaling cascade. However, they all play a role in the regulation of RA effects on gonocyte differentiation.

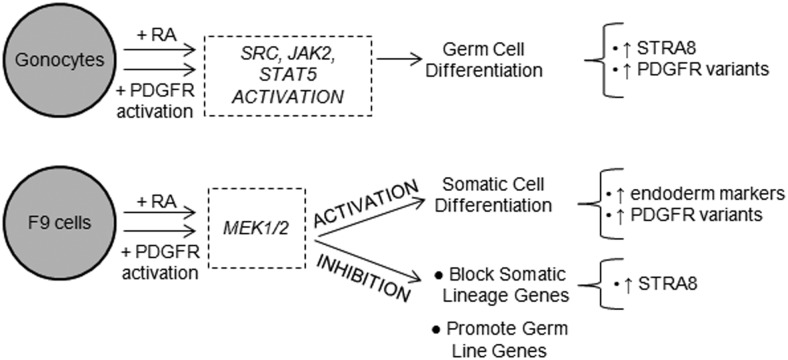

In conclusion, our study reports the existence of common signaling mechanisms in the regulation of RA-induced differentiation between an ESC-like cell type and PND3 gonocytes, including the formation of PDGFRα variants. However, although both cell types require PDGFR activation for RA-induced differentiation, they involve the activation of different signaling pathways (Figure 8). Overall, a better understanding of signaling mechanisms in gonocyte differentiation should help to provide a more in depth understanding of how SSCs are formed and how the disruption of gonocyte differentiation may lead to TGCTs. Proteins, such as specific variant forms, provide new potential targets for better drug development for male reproductive pathologies.

Figure 8. Summary diagram of the signaling pathways cross talking with RA.

The results of this study indicate that RA cross talk with PDGFR-related signaling pathways in differentiating F9 embryonal carcinoma cells and PND3 gonocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jaroslav Novak for assistance with microarray data analysis and biostatistics.

Present address for Y.W.: US Food and Drug Administration/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research/Office of Pharmaceutical Science/Office of Biotechnology Products/Division of Therapeutic Proteins, Silver Spring, MD 20993.

This work was supported in part by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant 386038-2013 and an award from the Royal Victoria Hospital Foundation, Montreal (M.C.); and by funds from the Centre for the Study of Reproduction, McGill University, the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism (McGill University Health Centre), and the Réseau Québecois en Reproduction (G.M.). The Research Institute of McGill University Health Centre is supported in part by a Center grant from Le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Quebec.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant 386038-2013 and an award from the Royal Victoria Hospital Foundation, Montreal (M.C.); and by funds from the Centre for the Study of Reproduction, McGill University, the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism (McGill University Health Centre), and the Réseau Québecois en Reproduction (G.M.). The Research Institute of McGill University Health Centre is supported in part by a Center grant from Le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Quebec.

Footnotes

- BrdU

- bromodeoxyuridine

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- FTS

- farnesylthiosalicylic acid

- FYN

- proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase FYN

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- JAK/STAT

- Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- LCK

- lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- MS

- mass spectrometer

- PDGFR

- platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- PND

- postnatal day

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- RA

- retinoic acid

- RAR

- RA receptor

- RARE

- RA-response element

- RAS

- rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- RXR

- retinoid X receptor

- S1P1

- sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1

- SRC

- v-src avian sarcoma (Schmidt-Ruppin A-2) viral oncogene

- SSC

- spermatogonial stem cell

- TF

- transcription factor

- TGCT

- testicular germ cell tumor.

References

- 1. Culty M. Gonocytes, the forgotten cells of the germ cell lineage. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2009;876:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Culty M. Gonocytes, from the fifties to the present: is there a reason to change the name? Biol Reprod. 2013;89(2):46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orth JM, Boehm R. Functional coupling of neonatal rat Sertoli cells and gonocytes in coculture. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2812–2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGuinness MP, Orth JM. Reinitiation of gonocyte mitosis and movement of gonocytes to the basement membrane in testes of newborn rats in vivo and in vitro. Anat Rec. 1992;233:527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGuinness MP, Orth JM. Gonocytes of male rats resume migratory activity postnatally. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59:196–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshida S, Sukeno M, Nakagawa T, et al. The first round of spermatogenesis is a distinctive program that lacks the self-renewing spermatogonia stage. Development. 2006;133:495–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skakkebaek NE, Berthelsen JG, Giwercman A, Müller J. Carcinoma-in-situ of the testis: possible origin from gonocytes and precursor of all types of germ cell tumours except spermatocytoma. Int J Androl. 1987;10:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Culty M. Identification and distribution of a novel platelet-derived growth factor receptor β variant: effect of retinoic acid and involvement in cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2233–2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schrans-Stassen BH, van de Kant HJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5894–5900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rochette-Egly C, Chambon P. F9 embryocarcinoma cells: a cell autonomous model to study the functional selectivity of RARs and RXRs in retinoid signaling. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16(3):909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malashicheva AB, Kislyakova TV, Aksenov ND, Osipov KA, Pospelov VA. F9 embryonal carcinoma cells fail to stop at G1/S boundary of the cell cycle after γ-irradiation due to p21WAF1/CIP1 degradation. Oncogene. 2000;19:3858–3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soprano DR, Teets BW, Soprano KJ. Role of retinoic acid in the differentiation of embryonal carcinoma and embryonic stem cells. Vitam Horm. 2007;75:69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oulad-Abdelghani M, Bouillet P, Décimo D, et al. Characterization of a premeiotic germ cell-specific cytoplasmic protein encoded by Stra8, a novel retinoic acid-responsive gene. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(2):469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Samarut E, Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear retinoic acid receptors: conductors of the retinoic acid symphony during development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhinn M, Dollé P. Retinoic acid signalling during development. Development. 2012;139:843–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balmer JE, Blomhoff R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2002;42:1773–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Claesson-Welsh L. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor signals. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32023–32026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klinghoffer RA, Mueting-Nelsen PF, Faerman A, Shani M, Soriano P. The two PDGF receptors maintain conserved signaling in vivo despite divergent embryological functions. Mol Cell. 2001;7:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loveland KL, Hedger MP, Risbridger G, Herszfeld D, De Kretser DM. Identification of receptor tyrosine kinases in the rat testis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;36:440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li H, Papadopoulos V, Vidic B, Dym M, Culty M. Regulation of rat testis gonocyte proliferation by platelet-derived growth factor and estradiol: identification of signaling mechanisms involved. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thuillier R, Wang Y, Culty M. Prenatal exposure to estrogenic compounds alters the expression pattern of platelet-derived growth factor receptors α and β in neonatal rat testis: identification of gonocytes as targets of estrogen exposure. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:867–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thuillier R, Mazer M, Manku G, Boisvert A, Wang Y, Culty M. Interdependence of platelet-derived growth factor and estrogen-signaling pathways in inducing neonatal rat testicular gonocytes proliferation. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manku G, Mazer M, Culty M. Neonatal testicular gonocytes isolation and processing for immunocytochemical analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;825:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manku G, Wing SS, Culty M. Expression of the ubiquitin proteasome system in neonatal rat gonocytes and spermatogonia: role in gonocyte differentiation. Biol Reprod. 2012;87(2):44, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dym M, Lamsam-Casalotti S, Jia MC, Kleinman HK, Papadopoulos V. Basement membrane increases G-protein levels and follicle-stimulating hormone responsiveness of Sertoli cell adenylyl cyclase activity. Endocrinology. 1991;128(2):1167–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thuillier R, Manku G, Wang Y, Culty M. Changes in MAPK pathway in neonatal and adult testis following fetal estrogen exposure and effects on rat testicular cells. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:773–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilm M, Shevchenko A, Houthaeve T, et al. Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature. 1996;379:466–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rone MB, Liu J, Blonder J, et al. Targeting and insertion of the cholesterol-binding translocator protein into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Biochemistry. 2009;48(29):6909–6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bryckaert MC, Eldor A, Fontenay M, et al. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor-induced mitogenesis and tyrosine kinase activity in cultured bone marrow fibroblasts by tyrphostins. Exp Cell Res. 1992;199(2):255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strickland S, Smith KK, Marotti KR. Hormonal induction of differentiation in teratocarcinoma stem cells: generation of parietal endoderm by retinoic acid and dibutyryl cAMP. Cell. 1980;21:347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clifford J, Chiba H, Sobieszczuk D, Metzger D, Chambon P. RXRα-null F9 embryonal carcinoma cells are resistant to the differentiation, anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of retinoids. EMBO J. 1996;15:4142–4155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwamoto H, Nakamuta M, Tada S, Sugimoto R, Enjoji M, Nawata H. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1295 attenuates rat hepatic stellate cell growth. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135(5):406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berridge MJ. Phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis: a multifunctional transducing mechanism. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1981;24:115–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(4):1283–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bleasdale JE, Bundy GL, Bunting S, et al. Inhibition of phospholipase C dependent processes by U-73, 122. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Leukot Res. 1989;19:590–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, et al. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(29):18623–18632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hiraga Y, Kihara A, Sano T, Igarashi Y. Changes in S1P1 and S1P2 expression during embryonal development and primitive endoderm differentiation of F9 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun,. 2006;344(3):852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krawetz R, Kelly GM. Moesin signalling induces F9 teratocarcinoma cells to differentiate into primitive extraembryonic endoderm. Cell Signal. 2008;20(1):163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weiler-Guettler H, Yu K, Soff G, Gudas LJ, Rosenberg RD. Thrombomodulin gene regulation by cAMP and retinoic acid in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(6):2155–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ravanko K, Jarvinen K, Helin J, Kalkkinen N, Holtta E. Cysteine cathepsins are central contributors of invasion by cultured adenosylmethionine decarboxylase-transformed rodent fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;8831–8838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prence EM, Dong JM, Sahagian GG. Modulation of the transport of a lysosomal enzyme by PDGF. J Cell Biol. 1990;110(2):319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mosselman S, Looijenga LH, Gillis AJ, et al. Aberrant platelet-derived growth factor α receptor transcript as a diagnostic marker for early human germ cell tumors of the adult testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2884–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boulogne B, Levacher C, Durand P, Habert R. Retinoic acid receptors and retinoid X receptors in the rat testis during fetal and postnatal development: immmunolocalization and implication in the control of the number of gonocytes. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1548–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vernet N, Dennefeld C, Rochette-Egly C, et al. Retinoic acid metabolism and signaling pathways in the adult and developing mouse testis. Endocrinology. 2006;147(1):96–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Germain P, Gaudon C, Pogenberg V, et al. Differential action on coregulator interaction defines inverse retinoid agonists and neutral antagonists. Chem Biol. 2009;16(5):479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Araujo J, Logothetis C. Dasatinib: a potent SRC inhibitor in clinical development for the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(6):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Benati D, Baldari CT. SRC family kinases as potential therapeutic targets for malignancies and immunological disorders. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(12):1154–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhuang Y, Faria TN, Chambon P, Gudas LJ. Identification and characterization of retinoic acid receptor β2 target genes in F9 teratocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:619–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chiariello M, Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS. Regulation of c-myc expression by PDGF through Rho GTPases. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3(6):580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bastien J, Plassat JL, Payrastre B, Rochette-Egly C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway is essential for the retinoic acid-induced differentiation of F9 cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:2040–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hu X, Jin L, Feng L. Erk1/2 but not PI3K pathway is required for neurotrophin 3-induced oligodendrocyte differentiation of post-natal neural stem cells. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mercola M, Wang CY, Kelly J, et al. Selective expression of PDGF A and its receptor during early mouse embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1990;138:114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Verheijen MH, Wolthuis RM, Bos JL, Defize LH. The Ras/Erk pathway induces primitive endoderm but prevents parietal endoderm differentiation of F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adachi S, Iwata M. Duration of calcineurin and ERK signals regulates CD4/CD8 lineage commitment of thymocytes. Cell Immunol. 2002;215:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Palumbo C, van Roozendaal K, Gillis AJ, et al. Expression of the PDGF α-receptor 1.5 kb transcript, OCT-4, and c-KIT in human normal and malignant tissues. Implications for the early diagnosis of testicular germ cell tumours and four our understanding of regulatory mechanisms. J Pathol. 2002;196:467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Basciani S, Mariani S, Arizzi M, et al. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A), PDGF-B, and PDGF receptor-α and -β during human testicular development and disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2310–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Housden BE, Perrimon N. Spatial and temporal organization of signaling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(10):457–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stavridis MP, Collins BJ, Storey KG. Retinoic acid orchestrates fibroblast growth factor signalling to drive embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2010;137:881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gu P, LeMenuet D, Chung AC, Mancini M, Wheeler DA, Cooney AJ. Orphan nuclear receptor GCNF is required for the repression of pluripotency genes during retinoic acid-induced embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8507–8519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 61. Blake RA, Broome MA, Liu X, et al. SU6656, a selective src family kinase inhibitor, used to probe growth factor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(23):9018–9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Keating GM, Lyseng-Williamson KA, McCormack PL, Keam SJ. Dasatinib: a guide to its use in chronic myeloid leukemia in the EU. BioDrugs. 2013;27:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nielsen M, Kaltoft K, Nordahl M, et al. Constitutive activation of a slowly migrating isoform of Stat3 in mycosis fungoides: tyrphostin AG490 inhibits Stat3 activation and growth of mycosis fungoides tumor cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(13):6764–6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Manabe N, Kubota Y, Kitanaka A, Ohnishi H, Taminato T, Tanaka T. Src transduces signaling via growth hormone (GH)-activated GH receptor (GHR) tyrosine-phosphorylating GHR and STAT5 in human leukemia cells. Leuk Res. 2006;30(11):1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Drayer AL, Boer AK, Los EL, Esselink MT, Vellenga E. Stem cell factor synergistically enhances thrombopoietin-induced STAT5 signaling in megakaryocyte progenitors through JAK2 and Src kinase. Stem Cells. 2005;23(2):240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]