Abstract

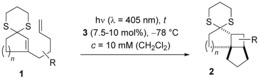

1,3‐Dithiane‐protected enones (enone dithianes) were found to undergo an intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition under visible‐light irradiation (λ=405 nm) in the presence of a Brønsted acid (7.5–10 mol %). Key to the success of the reaction is presumably the formation of colored thionium ions, which are intermediates of the catalytic cycle. Cyclobutanes were thus obtained in very good yields (78–90 %). It is also shown that the dithiane moiety can be reductively or oxidatively removed without affecting the photochemically constructed ring skeleton.

Keywords: Brønsted acids, cycloaddition, diastereoselectivity, enones, homogenous catalysis, photochemistry

Among all photochemical reactions, the [2+2] photocycloaddition is undoubtedly of the greatest synthetic importance.1 This reaction enables the simultaneous construction of two C−C bonds and up to four stereogenic centers. In this regard, it parallels the thermal [4+2] cycloaddition, the Diels–Alder reaction, which allows for a similarly high increase in complexity. In the case of a [2+2] photocycloaddition, the newly formed ring is a strained four‐membered ring (cyclobutane), which offers multiple options for further functionalization.2, 3 The photochemically excitable component of a [2+2] photocycloaddition is frequently a cyclic α,β‐unsaturated carbonyl compound, and its olefinic double bond can react with a suitable alkene either inter‐ or intramolecularly. Embedding the double bond in a cyclic compound avoids deactivation in the excited state by E/Z isomerization. Conjugation to the carbonyl group allows for direct long‐wavelength excitation, for example, at λ abs=300–350 nm with cycloalkenones (enones; Scheme 1).4

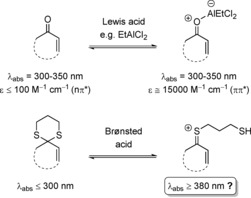

Scheme 1.

Upon coordination of a Lewis acid to an enone, an onium ion is formed, which strongly absorbs at λ abs=300–350 nm (top). Can a thionium ion that absorbs in the visible region (λ abs>380 nm) be formed upon protonation of a 1,3‐dithiane (bottom)?

We recently showed that the long‐wavelength absorption of typical enones becomes more intense upon complexation by a Lewis acid.5 This observation is in agreement with earlier studies that reported on a similar behavior for coumarins and other α,β‐unsaturated β‐aryl‐substituted carbonyl compounds.6 The reason for the intensity increase is a bathochromic shift of the strong short‐wavelength ππ* absorption.5c As a consequence of the high absorption cross‐sections of such Lewis acid/enone complexes, [2+2] photocycloaddition reactions can be rendered enantioselective in the presence of a chiral Lewis acid.5, 7, 8

When searching for substrates that exhibit a negligible long‐wavelength absorption but would potentially show a strong bathochromic shift upon activation by an acid, we tested enones upon transformation of their carbonyl groups into 1,3‐dithianes (enone dithianes). The putative thionium ions that were expected to be formed upon protonation could potentially be excited in the visible region (λ abs>380 nm),9 and would thus be suited to undergo a Brønsted acid catalyzed [2+2] photocycloaddition (Scheme 1). Possible background reactions should be completely avoided. We now report initial results of our studies.

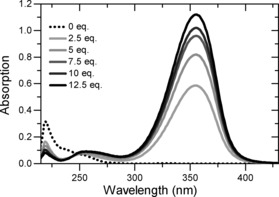

In a first set of experiments, the UV/Vis spectra of cyclic S,S‐acetals derived from 3‐(4‐pentenyl)‐cyclohex‐2‐enone were recorded. As expected, no significant absorption was observed at wavelengths of λ≥300 nm. The spectrum of dithiane 1 a 10 is depicted as a representative example in Figure 1 (dotted line). Upon addition of bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide Tf2NH (Tf=trifluoromethanesulfonyl) as a Brønsted acid, the solution of 1 a turned yellow, and a strong long‐wavelength absorption with a maximum at λ abs=356 nm was observed that stretched into the visible region. The absorbance reached saturation after addition of 12.5 equiv of the Brønsted acid. Assuming full conversion of the dithiane, the value for the molar decadic absorption coefficient ϵ was calculated as 23 900 m −1 cm−1.

Figure 1.

UV/Vis spectrum of compound 1 a in CH2Cl2 as the solvent (c=0.5 mm) without Brønsted acid (••••) and after addition of various equivalents of Tf2NH (—).

As the absorption of the putative thionium ion partially lies in the visible region, it was attempted to induce a reaction with light of λ≥380 nm in the presence of a catalytic amount of a Brønsted acid. To this end, light emitting diodes (LEDs) were employed as the light source, which exhibit a sharp emission band.11 To our delight, at λ=398 nm, 1,3‐dithiane 1 a was indeed converted into product 2 a in an intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition upon addition of 10 mol % Tf2NH (Table 1, entry 1). The dithiane turned out to be clearly superior to the corresponding 1,3‐dithiolane, which did not undergo a reaction under the same reaction conditions.12

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions for the Brønsted acid catalyzed [2+2] photocycloaddition of 1,3‐dithiane 1 a to cyclobutane 2 a.

| Entry | Catalyst[a] | Loading [mol %] | λ [nm] | t [b] [h] | Yield[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tf2NH | 10 | 398 | 2.5 | 88 |

| 2 | HOTf | 10 | 398 | 3.0 | 81 |

| 3 | CSA | 10 | 398 | 26.0 | –[d] |

| 4 | B(C6F5)3 | 10 | 398 | 22.0 | 44 |

| 5 | C6F5CHTf2 | 10 | 398 | 5.5 | 86 |

| 6 |

|

10 | 398 | 1.5 | 86 |

| 7 | 3 | 10 | –[e] | 3.5 | –[d] |

| 8 | 3 | 7.5 | 398 | 3.5 | 86 |

| 9 | 3 | 7.5 | 405 | 3.5 | 85[f] |

[a] All reactions were performed on 0.1 mmol scale with an LED lamp (7 W power output, emission at the indicated wavelength)11 as the light source.13 Cooling bath: acetone/dry ice. [b] Irradiation time. [c] Yield of isolated product. [d] No reaction. The starting material was recovered. [e] Without irradiation. [f] The reaction was successfully performed under almost identical conditions (c=20 mm, 16 h, 10 W, 93 % yield) on a larger scale (1.6 mmol).

When testing further acids, the strong Brønsted acids HOTf (entry 2), C6F5CHTf2 (entry 5), and imide 3 (entry 6) were found to perform well while a weaker acid (camphorsulfonic acid, CSA; entry 3) and the Lewis acid B(C6F5)3 (entry 4) delivered unsatisfactory results. The absence of a reaction with CSA correlates with the fact that there was no long‐wavelength absorption to be detected in the UV/Vis spectrum of 1 a even upon addition of 40 equivalents of this acid (see the Supporting Information).

It was then unambiguously established that the reaction was indeed light‐induced (entry 7). As imide 3 exhibited the strongest rate acceleration, the catalyst loading was lowered for this acid. Even at a loading of 7.5 mol %, the reaction was complete after 3.5 hours (entry 8), and it was possible to apply light of a longer wavelength (λ=405 nm) without a deterioration in yield (entry 9). These conditions were subsequently employed for the reaction of other dithianes 1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Brønsted acid catalyzed [2+2] photocycloaddition of various dithianes 1

10 under visible‐light irradiation.

| Entry | Substrate[a] | t [b] [h] | Product | Yield[c] [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

5 |

|

80[d] |

| 2 |

|

22 |

|

78[e] |

| 3 |

|

24 |

|

86[e] |

| 4 |

|

21 |

|

78[d,f] |

| 5 |

|

24 |

|

90[e,g] |

| 6 |

|

21 |

|

89[e,h] |

| 7 |

|

24 |

|

79[e,h] |

| 8 |

|

6 |

|

85[d,i] |

[a] All reactions were performed on 0.1 mmol scale with an LED lamp (7 W power output, λ=405 nm)11 as the light source.13 Cooling bath: acetone/dry ice. [b] Irradiation time. [c] Yield of isolated product. [d] Catalyst (7.5 mol %). [e] Catalyst (10 mol %). [f] Irradiation at λ=366 nm. [g] 60:40 d.r. [h]≥95/5 d.r. [i] 90:10 d.r.

The δ‐dimethylated analogue 1 b of enone dithiane 1 a reacted as smoothly as the parent compound (entry 1). Compound 1 c, which is dimethylated in the side chain, was somewhat less reactive, and a longer irradiation time and a higher catalyst loading were required to guarantee full conversion (entry 2). The reaction of dithiane 1 d to the highly strained cyclobutene 2 d is a remarkable transformation that proceeded in very high yield (entry 3). With cyclopentenone dithiane 1 e, it was already observed by visual inspection that the bathochromic shift that occurs upon Brønsted acid addition14 is not very extensive, and the reaction was therefore conducted at λ=366 nm (entry 4). The reactions of the chiral substrates 1 f–1 i were again conducted under visible‐light irradiation (λ=405 nm), and the yields were very high in all cases (entries 5–8).

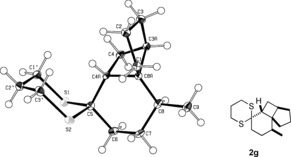

As anticipated, a stereogenic center in δ‐position led to poor facial differentiation, and product 2 f was isolated as a mixture of diastereomers (d.r.=diastereomeric ratio; entry 5). The asymmetric induction by a stereogenic center in γ‐position, however, is excellent, and product 2 g (entry 6), as well as product 2 h (entry 7), was formed in diastereomerically pure form. Owing to 1,3‐allylic strain,15 the [2+2] photocycloaddition of substrate 1 i also proceeded with high facial diastereoselectivity (entry 8). In most instances, the relative configurations were unambiguously assigned by one‐ and two‐dimensional NMR spectroscopy and NOESY experiments (see the Supporting Information). For product 2 g, however, a crystal structure was required to determine the relative configuration beyond any doubt (Figure 2). The configuration of product 2 h was assigned in analogy to that of 2 g.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of the relative configuration of product 2 g by crystal‐structure analysis.

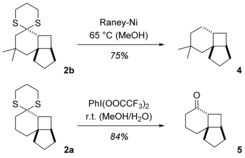

It is well established that dithiane moieties can be removed reductively or oxidatively,16 and with the tricyclic products 2 of the [2+2] photocycloadditions, the cleavage also proceeded without any complications. The reductive desulfurization17 was exemplarily performed with product 2 b and delivered the volatile hydrocarbon 4 18 in 75 % yield (Scheme 2). Upon treatment of product 2 a with [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]benzene,19 ketone 5 was obtained in 84 % yield. The cleavage can also be used to generate the respective ketones without isolation of the intermediate dithiane photoproducts. In the case of substrate 1 j, for example, it turned out to be impossible to separate product 2 j from minor impurities. Consequently, the dithiane moiety was removed oxidatively, and the pure product 6 was isolated as a mixture of the two diastereomers cis‐6 and trans‐6 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 2.

Reductive (2 b→4) and oxidative (2 a→5) removal of the dithiane moiety in the products 2 of the [2+2] photocycloaddition.

Scheme 3.

Combination of the [2+2] photocycloaddition with oxidative cleavage of the dithiane group to obtain ketones 6 directly from substrate 1 j.

The [2+2] photocycloaddition of the Z‐configured substrate 1 j proceeded in a stereo‐unspecific fashion, that is, without retention of the double‐bond configuration. The ratio of the two diastereomeric cyclobutanes was already determined prior to cleavage of the dithiane group to be 67:33 by GC analysis. This finding supports the notion that the reaction proceeds via triplet 1,4‐diradical 8,20 in which free rotation about the indicated single bond is feasible (Scheme 4). As illustrated for substrate 1 j, the excitation thus proceeds via thionium ion 7, which undergoes ring closure to intermediate 8 upon intersystem crossing (ISC). The strong absorption of the thionium ion (Figure 1) indicates that a ππ* singlet state (S1) is populated upon excitation.21

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism for the Brønsted acid catalyzed [2+2] photocycloaddition, exemplarily shown for substrate 1 j.

The configuration of the C=S double bond in 7 remains unclear but the sensitivity of the reaction towards steric hindrance at the terminal end of the olefinic double bond provides circumstantial evidence for the depicted Z configuration. The dithiane group also points towards the cyclobutane ring in the reaction products (see Figure 2), which indicates that the carbon chain at the sulfur atom is somewhat biased towards this orientation.

In conclusion, we have shown for the first time that derivatives of cyclic enones can undergo a [2+2] photocycloaddition under visible‐light irradiation. The resulting dithianes 2 offer several options for chemical functionalization. The most important result of this study, however, seems to be the fact that catalytic amounts of a Brønsted acid are sufficient to render an otherwise photochemically inaccessible reaction pathway viable. We are convinced that the strategy of catalytic chromophore activation will enable further transformations to be performed with visible light that have thus far only been possible upon UV irradiation. Moreover, the use of chiral 1,3‐dithianes22 or chiral Brønsted acids23 might allow to achieve enantioselectivity with methods that cannot be applied to the classic [2+2] photocycloaddition of enones.

In memory of Marcus Hübel

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the European Research Council as part of the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 665951, ELICOS) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Andreas Bauer und M.Sc. Philipp Altmann for their help with the measurement of fluorescence spectra.

C. Brenninger, A. Pöthig, T. Bach, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4337.

Contributor Information

M. Sc. Christoph Brenninger, http://www.oc1.ch.tum.de/home_en/

Prof. Dr. Thorsten Bach, Email: thorsten.bach@ch.tum.de.

References

- 1.For reviews, see:

- 1a. Crimmins M. T., Reinhold T. L., Org. React. 1993, 44, 297–588; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Mattay J., Conrads R., Hoffmann R. in Methoden der Organischen Chemie (Houben-Weyl), 4th ed., issue E 21c (Eds.: G. Helmchen, R. W. Hoffmann, J. Mulzer, E. Schaumann), Thieme, Stuttgart, 1995, pp. 3085–3132; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Margaretha P. in Molecular and Supramolecular Photochemistry, Vol. 12 (Eds.: A. G. Griesbeck, J. Mattay), Dekker, New York, 2005, pp. 211–237; [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Hehn J. P., Müller C., Bach T. in Handbook of Synthetic Photochemistry (Eds.: A. Albini, M. Fagnoni), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009, pp. 171–215; [Google Scholar]

- 1e. Poplata S., Tröster A., Zou Y. Q., Bach T., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9748–9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review, see: Namyslo J. C., Kaufmann D. E., Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1485–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For applications in total synthesis, see:

- 3a. Iriondo-Alberdi J., Greaney M. F., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 4801–4815; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Hoffmann N., Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1052–1103; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Bach T., Hehn J. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1000–1045; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 1032–1077; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Kärkäs M. D., J. A. Porco, Jr. , Stephenson C. R. J., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9683–9747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For selected references on the photophysics of α,β-unsaturated cycloalkenones, see:

- 4a. Marsh G., Kearns D. R., Schaffner K., Helv. Chim. Acta 1968, 51, 1890–1899; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Bonneau R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 3816–3822; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Schalk O., Schuurman M. S., Wu G., Lang P., Mucke M., Feifel R., Stolow A., J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 2279–2287; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Cao J., Xie Z.-Z., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 6931–6945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Brimioulle R., Bach T., Science 2013, 342, 840–843; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Brimioulle R., Bach T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12921–12924; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 13135–13138; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Brimioulle R., Bauer A., Bach T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5170–5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Lewis F. D., Howard D. K., Oxman J. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 3344–3345; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Shim S. C., Kim E. I., Lee K. T., Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1987, 8, 140–144; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Lewis F. D., Barancyk S. V., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 8653–8661; [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Görner H., Wolff T., Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 1224–1230; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Guo H., Herdtweck E., Bach T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7782–7785; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 7948–7951; [Google Scholar]

- 6f. Vallavoju N., Selvakumar S., Jockusch S., Sibi M. P., Sivaguru J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5604–5608; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 5710–5714. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For a review, see: Brimioulle R., Lenhart D., Maturi M. M., Bach T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3872–3890; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 3944–3963. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Lewis acid coordination that is responsible for lowering the energy of the π* orbital presumably influences the ππ* triplet state in a similar fashion; see: Blum T. R., Miller Z. D., Bates D. M., Guzei I. A., Yoon T. P., Science 2016, 354, 1391–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For early indications for the intense long-wavelength absorption of thionium ions, see:

- 9a. Föhlisch B., Haug E., Chem. Ber. 1971, 104, 2324–2337; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Fabian J., Hartmann H., Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 2597–2608; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Carlsen L., Holm A., Acta Chem. Scand. B 1976, 30, 277–279; [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Ali M., Satchell D. P. N., Le V. T., J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The 1,3-dithianes were prepared from the respective cycloalk-2-enones with 1,3-propanedithiol and BF3⋅OEt2 in methanol; see: Corey E. J., Huang A. X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 710–714. Further details can be found in the Supporting Information. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The emission spectra of the LEDs are shown in the Supporting Information.

- 12.According to UV/Vis analysis, the 1,3-dithiolane analogue of 1 a requires a significantly higher acid concentration for notable long-wavelength absorption (see the Supporting Information). Under the given catalytic reaction conditions, the concentration of the thionium ion is apparently too low for a [2+2] photocycloaddition to take place.

- 13.For the reaction setup, see:

- 13a. Rackl D., Kais V., Kreitmeier P., Reiser O., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2157–2165; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Lenhart D., Pöthig A., Bach T., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6519–6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.This observation was supported by UV/Vis spectroscopy. The thionium ion derived from 1 e exhibits an absorption maximum at λ abs=337 nm.

- 15.

- 15a. Hoffmann R. W., Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1841–1860; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Bach T., Jödicke K., Kather K., Fröhlich R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar]

- 16.For reviews, see:

- 16a. Seebach D., Synthesis 1969, 17–36; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Yus M., Najera C., Foubelo F., Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 6147–6212; [Google Scholar]

- 16c. A. B. Smith III , Adams C. M., Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 365–377; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16d. Nakata M. in Science of Synthesis: Houben-Weyl Methods of Molecular Transformations, Vol. 30 (Ed.: J. Otera), Thieme, Stuttgart: 2007, pp. 351–434. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Bougault J., Cattelain E., Chabrier P., C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1939, 657–659; [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Hauptmann H., Walter W. F., Chem. Rev. 1962, 62, 347–404; [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Tal D. M., Keinaen E., Mazur Y., Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 4327–4330. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natural products with a tricyclo[5.4.0.01.5]undecane skeleton are known; see:

- 18a. Leimner J., Marschall H., Meier N., Weyerstahl P., Chem. Lett. 1984, 13, 1769–1772; [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Zdero C., Bohlmann F., Niemeyer H. M., Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3683–3691; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Zhang M.-L., Dong M., Huo C.-H., Li L.-G., Sauriol F., Shi Q.-W., Gu Y.-C., Makabe H., Kiyota H., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 5414–5417; [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Dou M., Di L., Zhou L.-L., Yan Y.-M., Wang X.-L., Zhou F.-J., Yang Z.-L., Li R.-T., Hou F.-F., Cheng Y.-X., Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6064–6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stork G., Zhao K., Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Becker D., Nagler M., Hirsh S., Ramun J., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1983, 371–373; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Becker D., Nagler M., Sahali Y., Haddad N., J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4537–4543; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Schuster D. I., Lem G., Kaprinidis N. A., Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 3–22; [Google Scholar]

- 20d. Schuster D. I. in CRC Handbook of Photochemistry and Photobiology, 2nd ed. (Eds.: W. M. Horspool, F. Lenci), CRC, Boca Raton, 2004, 72/1–72/24; [Google Scholar]

- 20e. Maturi M. M., Wenninger M., Alonso R., Bauer A., Pöthig A., Riedle E., Bach T., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 7461–7472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preliminary spectroscopic studies revealed that the excited thionium ions exhibit only very weak fluorescence (φ fl<0.01).

- 22.For examples of stereoselective Brønsted acid catalyzed Diels–Alder reactions employing chiral cyclic O,O-acetals, see:

- 22a. Alexakis A., Mangeney P., Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1990, 1, 477–511; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Sammakia T., Berliner M. A., J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6890–6891; [Google Scholar]

- 22c. Kumareswaran P., Vankar P. S., Reddy M. V. R., Pitre S. V., Roy R., Vankar Y. D., Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 23.For recent reviews, see:

- 23a. Mahlau M., List B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 518–533; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 540–556; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Parmar D., Sugiono E., Raja S., Rueping M., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9047–9153; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23c. Akiyama T., Mori K., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9277–9366; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23d. Monaco M. R., Pupo G., List B., Synlett 2016, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary