Abstract

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is a genetically complex neurological disorder in which overlapping genetic risk factors may contribute to the diversity and heterogeneity of the symptoms. The main goal of the study was to investigate, through analysis of heart rate variability (HRV), whether in RLS patients the MEIS1 polymorphism at risk influences the sympathovagal regulation in different sleep stages. Sixty-four RLS patients with periodic leg movement index above 15 per hour, and 38 controls underwent one night of video-polysomnographic recording. HRV in the frequency- and time- domains was analyzed during nighttime sleep. All RLS patients were genotyped, and homozygotes for rs2300478 in the MEIS1 locus were used for further analysis. Comparison of the sympathovagal pattern of RLS patients to control subjects did not show significant differences after adjustments for confounding factors in frequency-domain analyses, but showed an increased variability during N2 and N3 stages in time-domain analyses in RLS patients. Sorting of RLS patients according to MEIS1 polymorphism reconfirmed the association between MEIS1 and PLMS, and showed a significant increased sympathovagal balance during N3 stage in those homozygotes for the risk allele. RLS patients should be considered differently depending on MEIS1 genotype, some being potentially at risk for cardiovascular disorders.

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), also known as Willis-Ekbom disease, is a genetically complex neurological disorder in which overlapping genetic risk factors contribute to the diversity and heterogeneity of the symptoms1,2. Genome-wide association studies have evidenced common genetic variants on at least six genomic regions which, according to their odd ratios, moderately influence RLS symptoms1,2. Among them, MEIS1, a gene coding for a transcription factor of the TALE (Three Amino acid Loop Extension) Homeodomain family, is the largest risk factor identified so far3,4,5. In various species, Meis1 has been implicated in the development of several peripheral organs and nervous system structures including the striatum, the retina, the forebrain, the cerebellum and sympathetic neurons6,7,8,9,10. The SNPs (Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms) identified in the eighth intron of the MEIS1 gene suggest that deregulations of mRNA transcription and/or processing participate in the etiology of RLS. Accordingly, a decrease in MEIS1 mRNA and protein has been detected in RLS patients carrying these SNPs11. In addition, the SNP rs12469063 is located in a conserved genomic region across species that serves as a neuronal enhancer for the Meis1 gene, and transgenic reporter mice carrying this risk allele exhibit a reduced enhancer activity, providing the first evidence for a direct link between this SNP and the neuronal levels of Meis1 protein12.

The comorbidity between RLS and cardiovascular diseases has been largely investigated with conflicting results explained in part by individual heterogeneity among the populations investigated13,14,15,16. Moreover, a dysfunction or deregulation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) leading to tachycardia and high blood pressure has been hypothesized14,16,17,18,19. About 60–80% of the patients also present periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS), a pattern that is believed to increase cardiovascular risk, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation and coronary heart disease18,20,21. RLS patients with PLMS may be thus at risk for heart diseases and hypertension18. PLMS episodes occur simultaneously with activation of the SNS as revealed by Heart Rate Variability (HRV) analysis and a rise in blood pressure22,23,24,25. In the MEIS1 locus, rs2300478 and rs12469063 were found to be significantly more associated with PLMS than RLS suggesting a primary function of this gene in the generation of PLMS independently of RLS symptoms26,27.

The goals of the study were to: 1/compare RLS patients and healthy control subjects through Heart Rate Variability (HRV) analysis of ECG acquired during polysomnographic (PSG) recording; and 2/assess if the MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 influences the sympathovagal regulation according to sleep stages in RLS patients.

Results

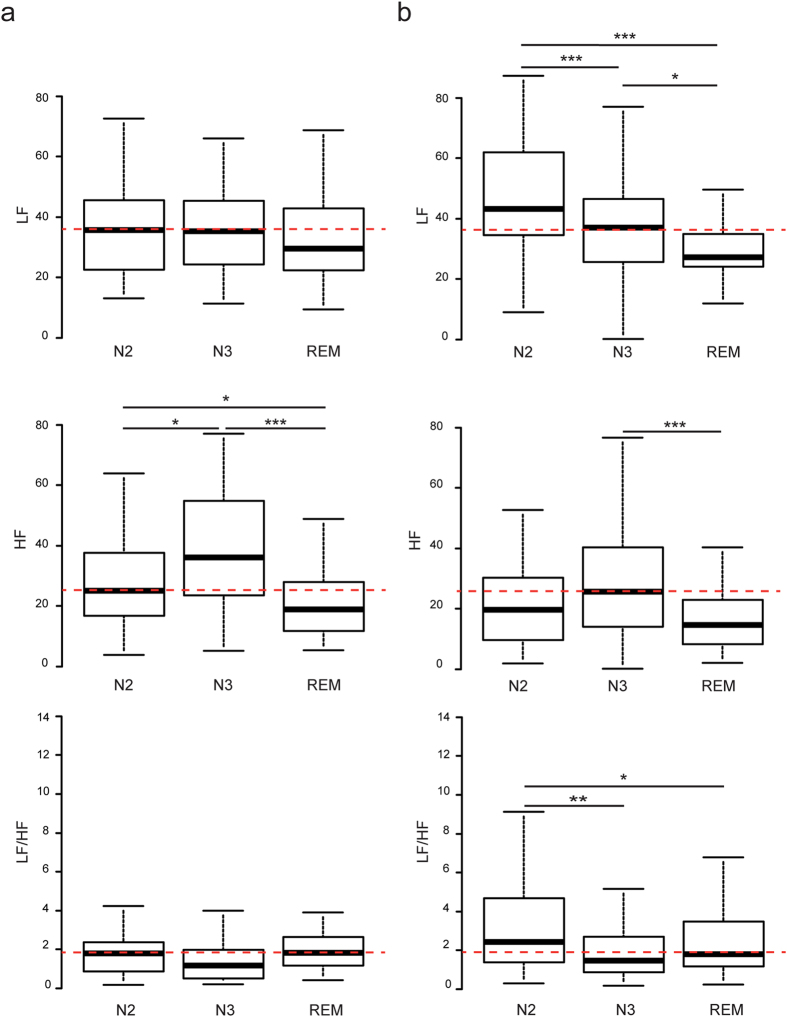

From frequency domain analysis, in RLS patients, the LF (Low Frequency power) band reflecting in part the sympathetic component of autonomic nervous system varied considerably during the different sleep stages with higher LFN2 than LFN3 and LFREM (p = 0.005 and 1.10−4 respectively), and higher LFN3 than LFREM (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1b). HF (High Frequency power) values showed a less pronounced variation with sleep stages but HFN3 and HFREM were statistically different (p = 0.005). The increased in LF band without major variation of HF band resulted in a significantly higher (LF/HF)N2 than (LF/HF)N3 and (LF/HF)REM (p = 0.002 and 0.037 respectively). In contrast, control subjects had stable LF and LF/HF values throughout sleep stages but with a dominant HF activity during N2 (Stage 2 of Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep) and N3 (Stage 3 of NREM sleep) stages with significantly higher HFN2 and HFN3 than HFREM (p = 0.04 and 1.10−4 respectively), and higher HFN3 than HFN2 (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1a). From time domain analysis, RRmean values significantly changed in control subjects during the different sleep stages with RRmeanN3 being lower than RRmeanN2 and RRmeanREM (p = 0.001 and p = 0.05 respectively). SDNNN3 (Standard Deviation of all normal RR intervals) was lower than SDNNN2 and SDNNREM (p = 5.10−5 and 0.0003 respectively), and RMSSDN3 (Root Mean Square of Successive Differences) was lower than RMSSDN2 (p = 0.009) (Supplementary Fig. S1a and Table S1). From Poincare plot geometry analysis in control subjects, SD1N3 (Standard Deviation 1) was lower than SD1N2 (p = 0.008), and SD2N3 (Standard Deviation 2) was lower than SD2N2 and SD2REM (p = 2.10−5 and 3.10−6 respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S2a and Table S2). Altogether, these time domain data indicate than in control subjects, cardiac rhythm was more stable during N3 stage than during N2 and REM stages. In contrast, Mean RR values did not significantly vary in RLS patients while SDNN fluctuated between sleep stages with a less regular rhythm in N2 than in N3 and REM (Rapid Eye Movement) stages as indicated by higher SDNNN2 than SDNNN3 (p = 0.02) and SDNNREM (p = 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. S1b and Table S1). This observation was also confirmed by RMSSD variations, with RMSSDN2 being higher than RMSSDREM (p = 0.003). Results from Poincare plot geometry analysis also underlined this increase in total variability during N2 stage in RLS patients, with both short- (SD1) and long-term (SD2) variations of RR during N2 stage being significantly higher than during REM stage (p = 0.003 and p = 0.03 respectively). Contrary to control subject, SD1N3 and SD2N3 in RLS patients were not significantly different than during N2 and REM stages (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S2).

Figure 1. HRV analysis in the frequency domain in RLS patients and control subjects.

Box-whisker plots showing LF, HF and LF/HF in control subjects (a) and in RLS patients (b) during N2, N3 and REM sleep stages. Data are represented as lower quartile, median and upper quartile (boxes), and minimum and maximum ranges (whiskers). Red dashed lines indicate the median values for LF, HF and LF/HF in control patients during N2 (A and B). p = p value following Student’s or Wilcoxon’s tests; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.005.

Compared with controls, patients with primary RLS were older and more frequently men, without significant differences for BMI (Body Mass Index) and ferritin levels (Table 1). As expected, a lower total sleep time and sleep efficiency together with a higher wake up time after sleep onset, PLMSREM and PLMSNREM indexes were found in RLS patients. Between-group comparison showed a different LF profile according to sleep stages with increased LFN2 and (LF/HF)N2 and decreased HFN3 in RLS patients (p = 0.002, 0.004 and 0.015 respectively) (Table 2). However, we found no significant differences after adjustment for age and sex (Table 2), and other potential confounders such as PLMS (data not shown). Using time-domain analysis, SDNN and RMSSD revealed that during both N2 and N3 stages, RLS patients present a higher variability than control subjects (pa = 0.0003 and 0.003 for SDNN during N2 and N3 respectively, and pa = 2.10−4 and 0.0026 for RMSSD during N2 and N3 respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S1). In RLS patients, SD1N2, SD1N3, SD2N2 and SD2N3 were all significantly increased in RLS patients compared to control subjects (pa = 2.10−4 and 4.10−3 for SD1 during N2 and N3 respectively, and pa = 8.10−3 and 0.019 for SD2 during N2 and N3 respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b and Table S2). Altogether, time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses confirmed the higher variability during N2 and N3 stages in RLS patients compared to control subjects. RLS patients also exhibited a higher variability during REM as seen by SDNN (pa = 0.03), RMSSD (pa = 0.017) and SD1 (pa = 0.017) (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b and Table S2).

Table 1. Clinical, biological and polysomnographical characteristics of RLS patients, healthy controls, and RLS patients sorted according to the MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 genotype (GG or TT).

| Control | RLS | p | pa | RLS GG | RLS TT | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 38 | 64 | NA | NA | 20 | 44 | NA |

| Age | 45.0 ± 9.5 | 61.5 ± 8.8 | 5.10−7*** | NA | 67.0 ± 8.0 | 60.0 ± 6.1 | 0.57 |

| Men, n (%) | 9 (23.7%) | 30 (46.9%) | 0.03* | NA | 10 (50%) | 20 (45.5%) | 0.95 |

| BMI | 26.9 ± 5.2 | 25.9 ± 3.1 | 0.38 | 0.792 | 25.4 ± 2.5 | 26.8 ± 3.2 | 0.22 |

| Ferritin | 68.5 ± 42.5 | 83.0 ± 50.0 | 0.12 | 0.911 | 84.5 ± 52.0 | 80.0 ± 48.5 | 0.76 |

| Age onset | NA | 45.0 ± 12.5 | NA | NA | 38.0 ± 13.0 | 50.0 ± 8.0 | 0.44 |

| RLS sev. | NA | 25.0 ± 4.0 | NA | NA | 26.5 ± 5.5 | 24.0 ± 5.0 | 0.28 |

| TST (min) | 382 ± 41 | 346 ± 48 | 0.0007*** | 0.0046## | 350 ± 67 | 346 ± 47 | 0.62 |

| SE (%) | 85 ± 8 | 74 ± 9 | 0.0001*** | 0.0748 | 70 ± 12 | 75 ± 9 | 0.79 |

| WASO | 36 ± 18 | 88 ± 31 | 0.0003*** | 0.0909 | 83 ± 19 | 89 ± 45 | 0.42 |

| SL | 16 ± 12 | 19 ± 11 | 0.45 | 0.623 | 21 ± 13 | 19 ± 10 | 0.17 |

| N1 (%) | 6.1 ± 3.1 | 7.8 ± 2.7 | 0.026* | 0.4104 | 7.5 ± 2.6 | 8.8 ± 6.3 | 0.44 |

| N2 (%) | 54.0 ± 3.5 | 49.8 ± 5.0 | 0.034* | 0.00265## | 47.9 ± 6.7 | 50.2 ± 8.4 | 0.81 |

| N3 (%) | 21.0 ± 3.2 | 21.1 ± 6.4 | 0.98 | 0.16679 | 20.9 ± 7.3 | 22.2 ± 8.4 | 0.45 |

| REM (%) | 16.7 ± 4.0 | 19.0 ± 4.3 | 0.35 | 0.0572 | 19.4 ± 4.7 | 18.9 ± 6.5 | 0.41 |

| iPLMNREM | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 38.3 ± 20.6 | 1.10−4*** | 0.00042### | 62.6 ± 36.2 | 29.9 ± 15.8 | 4.10−9*** |

| iPLMREM | 0 ± 0 | 4.1 ± 4.1 | 8.10−9*** | 0.08718 | 12.4 ± 11.6 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 0.32 |

| AHI | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 4.1 | 0.19 | 0.7298 | 5.2 ± 5.0 | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 0.49 |

| Min SaO2 | 91.5 ± 2.5 | 88.0 ± 4.0 | 0.16 | 0.8966 | 87.5 ± 3.5 | 88.0 ± 4.0 | 0.71 |

| Mean SaO2 | 95.5 ± 1.5 | 95.0 ± 1.0 | 0.41 | 0.173 | 94.0 ± 2.0 | 95.0 ± 1.0 | 0.64 |

| tSA O2 <90% | 0 ± 0 | 0.11 ± 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.3758 | 0.17 ± 0.17 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.38 |

BMI = body mass index; Ferritin = ferritin blood levels, RLS sev. = RLS severity index; TST = Total Sleep Time in minutes; SE = Sleep Efficiency; WASO = Wake After Sleep Onset; SL = Sleep Latency; N1 (%) = percentage of cumulated N1 stages duration over TST; N2 (%) = percentage of cumulated N2 stages duration over TST; N3 (%) = percentage of cumulated N3 stages duration over TST and REM (%) = percentage of cumulated REM stages duration over TST; iPLMNREM = PLM index during NREM sleep; iPLMREM = PLM index during REM sleep; AHI = apnea/hypopnea per hour of sleep index; Min SaO2 = minimal oxygen saturation; Mean SaO2 = average of oxygen saturation; tSA O2 <90% = time spent with an oxygen saturation inferior to 90% of total sleeping time. NA = Not Applicable. Data are presented as Median ± MAD. p = p value following Student or Wilcoxon’s test; pa = p value adjusted for age and gender. *p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.001.

Table 2. Results of heart rate variability analysis in the frequency domain in the different sleep stages in RLS patients and healthy controls, and in RLS patients sorted according to the MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 genotype (GG or TT).

| N2 | N3 | REM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LF | Median ± MAD | 35.7 ± 11.6 | 35.4 ± 10.0 | 29.5 ± 8.5 |

| HF | Median ± MAD | 25 ± 9.15 | 36.1 ± 15.7 | 18.9 ± 7.3 | |

| LF/HF | Median ± MAD | 1.81 ± 0.85 | 1.18 ± 0.71 | 1.82 ± 0.77 | |

| RLS | LF | Median ± MAD | 43.3 ± 16.3 | 37.1 ± 10.8 | 27.2 ± 6.8 |

| HF | Median ± MAD | 19.7 ± 10.3 | 25.7 ± 13.0 | 14.6 ± 7.2 | |

| LF/HF | Median ± MAD | 2.43 ± 1.42 | 1.47 ± 0.71 | 1.79 ± 0.77 | |

| Non adjusted | LF | p | 0.002*** | 0.44 | 0.52 |

| HF | p | 0.07 | 0.015* | 0.57 | |

| LF/HF | p | 0.004*** | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| Adjusted | LF | pa | 0.059 | 0.71 | 0.64 |

| HF | pa | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.8 | |

| LF/HF | pa | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.12 | |

| RLS TT | LF | Median ± MAD | 39.9 ± 11.9 | 36.7 ± 11.9 | 28.1 ± 6.2 |

| HF | Median ± MAD | 21.9 ± 12.1 | 27.3 ± 10.4 | 16.4 ± 8.7 | |

| LF/HF | Median ± MAD | 1.94 ± 0.95 | 1.35 ± 0.68 | 1.69 ± 0.65 | |

| RLS GG | LF | Median ± MAD | 59.3 ± 15.8 | 38.6 ± 8.0 | 26.9 ± 2.5 |

| HF | Median ± MAD | 14.4 ± 7.8 | 13.2 ± 10.0 | 13.2 ± 4.9 | |

| LF/HF | Median ± MAD | 4.00 ± 2.41 | 1.99 ± 1.09 | 1.88 ± 1.05 | |

| LF | p | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.43 | |

| HF | p | 0.18 | 0.02* | 0.09 | |

| LF/HF | p | 0.18 | 0.05* | 0.13 |

LF = Low Frequency; HF = High Frequency. Data are presented as Median ± MAD. p = p value following Student or Wilcoxon’s test; pa = p value adjusted for age and gender, or PLMS. *p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.005.

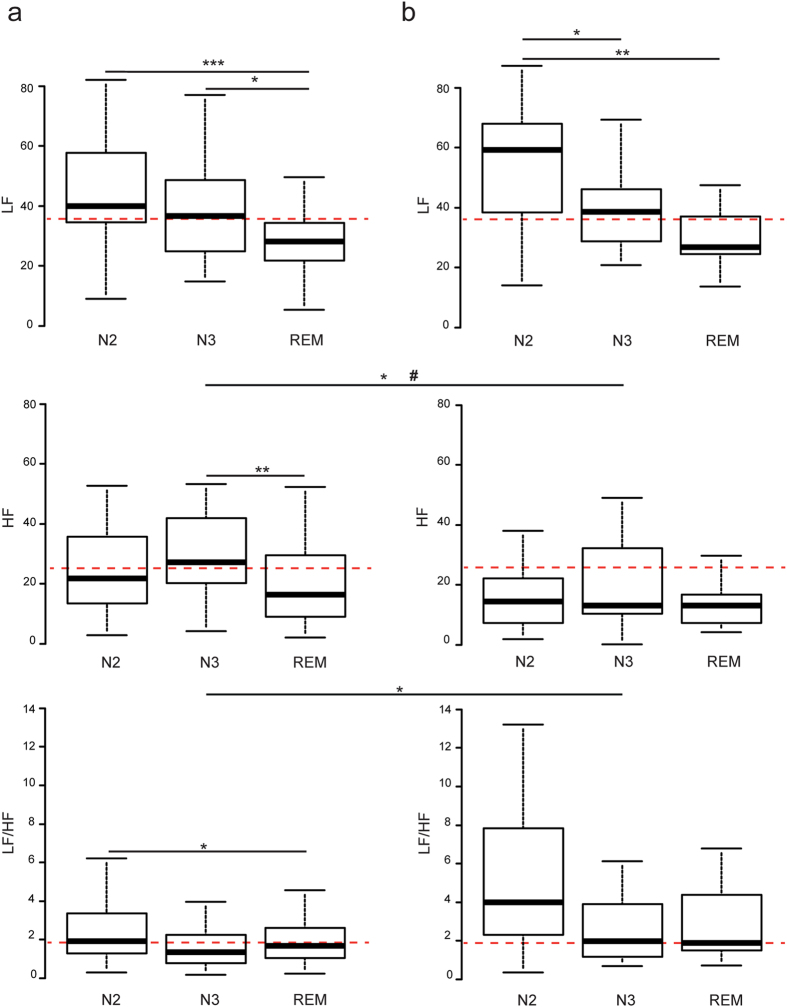

No demographic, clinical and PSG significant differences were found between patients with MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 TT and GG, except for a higher PLMSNREM index in sleep in patients GG (Table 1). HRV analysis in the frequency domain indicated that in the RLS GG group, LFN2 was significantly higher than LFN3 (p = 0.019) and LFREM (p = 0.003). In the RLS TT group, LFN2 and LFN3 were significantly higher than LFREM (p = 1.10−4 and 0.011 respectively). Between-group comparison showed that patients GG had a reduced HF power suggesting lower parasympathetic activity during N3 stage in crude analysis (p = 0.02) and after adjustment for PLMS (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2). No between-group significant differences were found in LF and LF/HF in any of the sleep stages after adjustment for age, gender and PLMS (Table 2). However, the sympatho-vagal LF/HF ratio in the RLS GG group was higher than in the TT group during N3 stage in crude analysis, a finding confirmed by time domain analysis. In the GG group, RRmean did not vary during the different sleep stages, whereas in the TT group, RRmeanN2 was higher than RRmeanREM (p = 0.02). Poincare plot analysis indicated a higher variability during N2 stage than during REM stage in the TT group as seen by a higher SD1N2 than SD1REM (p = 0.03), whereas in the GG group, variability during N2 was higher than during both N3 and REM stages with higher SD1N2 than SD1N3 and SD1REM (p = 0.03 and 0.04 respectively). Accordingly, in time domain analysis, RMSSDN2 was higher than RMSSDREM in the TT group (p = 0.03), whereas in the GG group, RMSSDN2 was higher than both RMSSDN3 and RMSSDREM (p = 0.03 and 0.04 respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S2c,d and Table S2). Finally, comparison of the TT and GG groups in time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses showed a higher variability with a more complex pattern in the RLS GG group than in the TT group, with higher SDNNN2, RMSSDN2, SD1N2 and SD2N2 in the GG group (p = 0.025, 0.02, 0.021 and 0.036 respectively) (Supplementary Figs S1c,d and S2c,d and Tables S1 and S2). After adjustment for PLMS, only SDNNN2 and SD2N2 remained significantly higher in the GG group than in the TT group (pa = 0.024 and 0.028 respectively). No significant differences were found between the GG group and the TT group during N3 and REM after adjustment for PLMS in time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses.

Figure 2. HRV analysis in the frequency domain in RLS patient as a function of the MEIS1 locus.

Box-whisker plots showing LF, HF and LF/HF in RLS TT (a) and RLS GG (b) patients during N2, N3 and REM sleep stages. Red dashed lines indicate the median values for LF, HF and LF/HF in control patients during N2 (a and b). Data are represented as lower quartile, median and upper quartile (boxes), and minimum and maximum ranges (whiskers). *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.005 following Student’s or Wilcoxon’s tests. #pa ≤ 0.05 following statistical test adjusted for PLMS.

Discussion

This study showed that MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 at risk for RLS influence the sleep stage-dependent sympathovagal balance in RLS patients. HRV analysis in the frequency domain revealed a reduction in the parasympathetic activity during slow-wave N3 stage in those homozygotes for the risk allele, whereas time domain and Poincare plot geometry parameters indicated an increased HRV during N2 and N3 stage in RLS patients-independently of MEIS1 genotype. In contrast, frequency domain parameters were not significantly different between patients with RLS and controls after adjustments for confounding factors.

Control subjects presented the expected pattern of sympathovagal balance during the different stages of sleep with stable LF values throughout sleep stages but a dominant parasympathetic activity during NREM sleep particularly in deep N3 sleep28,29,30,31. These results confirmed that in normal subjects, the sympathovagal balance during sleep is mostly influenced by the parasympathetic activity. In RLS patients, although the parasympathetic nervous system followed a similar pattern of activity than in control subjects, the overall sympathovagal balance tended to shift in favor of a predominant sympathetic activation, associated with reduced vagal influences, especially during N2 and N3 stages. However, we found no further significant changes between groups in frequency domain analysis when considering potential confounding factors such as age and gender. The most striking difference we found concerned the lack of parasympathetic activation during slow-wave sleep in RLS patients as a function of MEIS1 genotype. Indeed, only the RLS GG group did not increase HF during N3 although the LF band was identical in the TT group. We also confirmed the association between MEIS1 and PLMS with higher PLMS index in RLS patients GG for rs230047826,27. The reduced HFN3 activity found in these patients persists after adjustment for PLMS. A lack of parasympathetic responsiveness has been suggested in N2 stage during PLMS in children32 and in RLS patients during wakefulness by measuring the Valsalva ratio19. A weak and non-significant reduction of HF has also previously been reported during PLMS in N2 sleep in RLS patients25. The increased sympathetic activity leading to shortening of RR interval (Inter-beat interval) and a rise in systemic blood pressure preceding the onset of PLMS has previously been reported17,22,23,24,25,33,34,35. In RLS patients, the changes in HRV accompanying the PLMS are also more pronounced than in healthy patients35.

Time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses indicated that in control subjects, N3 stage exhibited less variability and complexity than other sleep stages as seen by RRmean, SDNN and SD2, and to some extend by RMSSD and SD1. Although the clinical and physiological interpretation of increased variability and complexity in time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses remains elusive36, and taking in account that these analyses should be performed on ECG recording longer than in the present study37, the lack of significant changes of RRmean, RMSSD, SD1 and SD2 during N3 in RLS patients compared to N2 and REM stages may reflect the low sympathovagal balance suggested by analyses in the frequency domain. Future analyses should be performed using new nonlinear/complexity methods38 to confirm and refine our conclusions and tempt to establish a clinical significance. Finally, the increased variability and complexity during N2 in RLS patients is consistent with the non-significant increase in the LF band.

Whereas increased variability during wake is commonly associated to a better prognosis in various situations such as heart failure39 or after myocardial infarction40, the consequence on the increased variability and complexity on short ECG sequences during N2 and in particular during N3 in RLS patients observed in time domain analysis can only be speculative. During N3, in normal subject, the autonomic balance driven by a parasympathetic dominance is part of a complex physiological response that has been referred as the cardiovascular holiday41. Thus, the increased variability and complexity seen by our time domain and Poincare plot geometry analyses during N3 stage in RLS patients, and reflecting a less stable cardiac rhythm, might be considered in the evaluation of the cardiovascular risk in RLS patients.

Our study highlights a potent sympatho-vagal balance resulting from a low parasympathetic modulation in RLS patients in ECG periods free of PLMS, and so, out of baroreflex adjustment of heart rate due to leg movement. This scenario suggests that these autonomic variations might play a primary role in the generation of the PLMS17. Accordingly, it has been proposed that a generator located at spinal level modulated by descending dopamine inhibitory pathways is involved in the generation of PLMS42,43. Experimental evidences converged to promote dopaminergic neurons of the hypothalamic A11 nucleus as a strong candidate likely involved in the promotion of PLMS and sympathetic activity44. Meis1 is widely expressed in the nervous system7,9,10 and recent Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies of whole brain functional connectivity in RLS patients demonstrated alterations in cortical and subcortical network, suggesting potential involvement of cortical, subcortical, spinal and peripheral nervous areas45. We recently showed that during mouse sympathetic neurons development, Meis1 serves as a dedicated maintenance factor allowing correct innervation of target organs and Meis1 inactivation lead to altered retrograde transport7. Similar mechanisms may apply to other neuronal types and thus contribute to RLS and PLMS, opening new hypotheses about its participation in the underlying deleterious cellular mechanisms.

The present study has some limitations. Our RLS population was well-characterized but relatively small with demographic differences, i.e. age and gender, compared to healthy controls. This may explain why despite substantial differences in autonomic balance between patients and controls, some parameters failed to reach statistical significance, especially when these parameters were adjusted to gender and age. The sample size of RLS patients was limited by the difficulty in combining stringent selection criteria, mainly available drug-free PSG, PLMS above 15 per hour, and MEIS1 SNP rs2300478 GG or TT homozygous. The two patient groups were deliberately chosen as extreme situations to investigate the involvement of MEIS1 SNP in the sympathovagal balance during sleep in RLS patients and therefore patients heterozygote for rs2300478 were not included. With a frequency of about 4% for the GG genotype in the general population, we were unable to isolate any healthy homozygote subjects which prevented analysis of a potential effect on sympatho-vagal balance in normal controls. All patients included in the study were drug-free for at least 15 days prior to sleep recording; however 45% of them were previously exposed to a RLS treatment that may thus be considered as a limitation. Finally, to avoid artifacts, only ECG of PLM-free periods were analyzed that may have underestimated the significance of our results.

Another limitation relates to the interpretation with HRV analysis being an indirect assessment of the cardiac autonomic activity using noninvasive monitoring of electrocardiogram. The interpretation of HRV index is based on correlation between HRV changes and attempted cardiac autonomic regulation following experimental maneuvers, development of pathologies or pharmacological study37. It is now well admitted that the efferent vagal activity remains the major contributor to the HF component, also named respiratory band, as seen in both clinical and experimental observations of autonomic maneuvers such as electrical vagal stimulation, muscarinic receptor blockade, and vagotomy46,47,48. However, measurement of HRV under control breathing is a critical issue for ECG recordings49. In our study, we did not verified that respiratory frequency is within the HF band, and therefore cannot exclude that very low respiratory rate in particular impacts both total and HF power densities. In addition, the interpretation of the LF band and its relation to cardiac sympathetic activity is also controversial and still under debate48,50. In this work, interpretation of the results was mainly done using the classical recommendations for the standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use of HRV for both practice and research37. Recent guidelines for psychiatry research preconize the same methodology for analysis and interpretation of HRV51. We also used Poincare plot geometry method to improve the analyses and interpretation of HRV measures as recently suggested36. However, both time domain and Poincare plot analyses were performed on short sequences i.e. 180 s which is below the recommended duration of 256 s. Briefly, since variance is mathematically the total power of spectral analysis, SDNN reflects cyclic components responsible for variability in the period of recording. When the monitored sequence is reduced in time, SDNN estimates shorter and shorter cycle lengths. Thus, the shorter is the analyzed ECG sequence, the more is the high frequency and SDNN arbitrarily increased52. This dependency of SDNN values on the length of the analyzed ECG sequences implies that on arbitrarily selected short ECGs, SDNN is a less reliable statistical parameter, should be cautiously interpreted and could explain some discrepancies found in the present study between time and frequency domain values in HRV.

Altogether our results demonstrate that RLS patients should be considered differently depending on their MEIS1 genotype. The lack of parasympathetic activity during slow-wave sleep in RLS patients homozygous for the MEIS1 risk allele may have clinical significance with potential links to the cardio-vascular risk observed in some patients, thus opening new perspectives for a personalized medical approach.

Methods

Population

Sixty-four drug-free patients (30 males and 34 females, mean age 58.9 ± 12.5) with primary RLS were included since 2010. Patients underwent a semi-structured assessment to confirm the RLS diagnosis using standard criteria53, and to detail the age of RLS onset, ferritin levels, presence of RLS symptoms in the arms, and family history of RLS. We excluded the presence of comorbidity suggestive of secondary RLS: iron deficiency, pregnancy, chronic renal failure, hemochromatosis or neurological diseases (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, polyneuropathy, fibromyalgia, dementia, myelitis, spin cerebellar ataxia and narcolepsy). The RLS severity index was assessed according to the criteria of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG)54. Although diagnosed before 2014, these patients fulfilled the revised diagnostic criteria55. Nine out of 64 RLS patients were diagnosed with hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) with 3 out of 20 in the RLS GG group and 6 out of 44 in the RLS TT group, and eight received a treatment with antihypertensive drugs at the time of study. Hypertensive patient treated with β-blocker were excluded.

As controls, 38 subjects (9 males and 29 females, mean age 44.9 ± 13.1) participated in the study. All controls had normal neurological examination, normal and regular sleep, no sleep complaint, and no RLS. Two control subjects had a treatment with antihypertensive drugs but no β-blocker.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Montpellier, France. Each participant signed legal informed consent forms. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Genotyping

All RLS patients were genotyped for rs2300478 in the MEIS1 locus as previously described5 and subdivided in two subgroups: one group homozygote G/G (at risk for RLS) and one group T/T (protective of RLS). RLS patients heterozygote for rs2300478 were not included.

Polysomnography

All participants underwent one night of PSG recording in the sleep laboratory as previously described56. Twenty-nine patients (45%) were previously treated for RLS [dopaminergic agonists (ropinirole, pramipexole, rotigotine in 86%), alpha 2 delta-ligands (pregabaline, gabapentin, 7%), levodopa-benserazide (3%), clonazepam and opioids (codeine, 4%)]. However, none of the participants was taking central nervous system (dopaminergic agonists, levodopa, α2δ ligands, clonazepam and opioids) or any other medications known to influence sleep or movements at least 2 weeks prior to sleep recording.

All PSGs were scored manually for sleep stages, PLMS in NREM and REM sleep, and respiratory events according to standard criteria57. Only patients with PLMS index above 15 per hour were included. Participants with an index of apneas + hypopneas >15/hour were excluded.

Heart rate variability analysis

HRV parameters were calculated from ECG (Electrocardiogram) taken during PSGs in period free of apneas, hypopneas and PLMS to avoid interferences caused by autonomic changes due to respiratory events and movements. HRV analyses were conducted during wakefulness before and after sleep onset, light NREM sleep (N2), slow-wave sleep (N3) and REM sleep stages. Only the data acquired in N2, N3 and REM sleep are presented. HRV analysis was performed using Kubios HRV analysis software58 according to international recommendations37. For each patient, 3 stationary ECG sequences of 3 minutes epoch duration without noise and missing data, artifact, conduction disturbance and cardiac ectopic beat were analyzed in each sleep stage. Each ECG signal was analyzed for automatic detection of R waves and beat-to-beat RR intervals were calculated. HRV was assessed using frequency and time domain analyses37. Data were sampled at 200 Hz. The interpolated R-R interval tachograms were then processed by the non-parametric Fast-Fourier Transform algorithm using Welch’s periodogram method (256 s length, overlapped by 50%). The low frequency power (LF range, 0.04–0.15 Hz)) and the high frequency power (HF range, 0.15–0.4 Hz) were calculated37. The efferent vagal activity is the major contributor to the HF component, including respiratory effect59, while the LF band reflects both baroreflex and sympathetic component of the autonomic nervous system50,59,60. The LF/HF ratio was calculated as an expression of the sympathovagal activity37,51. Linear time-domain measurements defined as the mean normal-to-normal R-R length (RRmean), standard deviation of normal-to-normal R-R intervals (SDNN), and root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) were also performed on the same 3 min ECG periods. Results obtained from Poincare plot geometry analysis applied to HRV assessed the standard deviation of instantaneous beat-to-beat interval variability (SD1) and the standard deviation of continuous long-term R/R interval variability (SD2). HRV analysis was performed blinded to diagnosis and genotyping.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was performed for each variable. Data are presented as Median ± Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) in tables and as lower quartile, median and upper quartile (boxes), and minimum and maximum ranges (whiskers) in figures, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. We used χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney or Student t test for quantitative variables, according to the normality of the distribution, assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test.

As control and RLS groups differed in age and sex, statistical comparison between both groups was conducted using a statistical model adjusted on these two parameters. Generalized linear mixed-effects model for repeated measures was used to take into account repeated measures. Similar comparisons were made in RLS patients according to the MEIS1 genotype. These statistical analyses were performed using R version 2.15.2. For all analyses, the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Thireau, J. et al. MEIS1 variant as a determinant of autonomic imbalance in Restless Legs Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 7, 46620; doi: 10.1038/srep46620 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by A.F.E. (Association France-Ekbom). S. Richard and J. Thireau were supported by the Fondation de France (SYNAPTOCARD, 2013 00038586). We thank P. Carroll for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions HRV analyses were performed and analyzed by J.T., C.F., F.B., F.M. and L.T. Statistical analyses were conducted by N.M. and F.M. Polysomnographic recording and demographic data were performed by Y.D. and S.S. Genetic analyses were conducted by J.W. F.M., Y.D., J.T. and S.R. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Dauvilliers Y. & Winkelmann J. Restless legs syndrome: update on pathogenesis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 19, 594–600, doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328365ab07 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenkwalder C., Allen R., Hogl B., Paulus W. & Winkelmann J. Restless legs syndrome associated with major diseases: A systematic review and new concept. Neurology 86, 1336–1343, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002542 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte E. C. et al. Targeted resequencing and systematic in vivo functional testing identifies rare variants in MEIS1 as significant contributors to restless legs syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 95, 85–95, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H. et al. A genetic risk factor for periodic limb movements in sleep. N Engl J Med 357, 639–647, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072743 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann J. et al. Genome-wide association study of restless legs syndrome identifies common variants in three genomic regions. Nat Genet 39, 1000–1006, doi: 10.1038/ng2099 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcoitia V., Aracil M., Martinez A. C. & Torres M. The homeodomain protein Meis1 is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and vascular patterning in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 280, 307–320, doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.004 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouilloux F. et al. Loss of the transcription factor Meis1 prevents sympathetic neurons target-field innervation and increases susceptibility to sudden cardiac death. Elife 5, doi: 10.7554/eLife.11627 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisa T. et al. Hematopoietic, angiogenic and eye defects in Meis1 mutant animals. EMBO J 23, 450–459, doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600038 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rataj-Baniowska M. et al. Retinoic Acid Receptor beta Controls Development of Striatonigral Projection Neurons through FGF-Dependent and Meis1-Dependent Mechanisms. J Neurosci 35, 14467–14475, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1278-15.2015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toresson H., Parmar M. & Campbell K. Expression of Meis and Pbx genes and their protein products in the developing telencephalon: implications for regional differentiation. Mech Dev 94, 183–187 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L. et al. MEIS1 intronic risk haplotype associated with restless legs syndrome affects its mRNA and protein expression levels. Hum Mol Genet 18, 1065–1074, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn443 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler D. et al. Restless legs syndrome-associated intronic common variant in Meis1 alters enhancer function in the developing telencephalon. Genome Res 24, 592–603, doi: 10.1101/gr.166751.113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferini-Strambi L., Walters A. S. & Sica D. The relationship among restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease), hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. J Neurol 261, 1051–1068, doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7065-1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes K. E., Selfe T. K. & Agarwal P. Restless legs syndrome and conditions associated with metabolic dysregulation, sympathoadrenal dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 16, 309–339, doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.04.001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Eeden S. K. et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Associated with a Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis in a Retrospective Cohort Study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Sleep 38, 1009–1015, doi: 10.5665/sleep.4800 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter A. C. et al. Restless legs syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in women and men: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2, e000866, doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000866 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggisberg A. G., Hess C. W. & Mathis J. The significance of the sympathetic nervous system in the pathophysiology of periodic leg movements in sleep. Sleep 30, 755–766 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters A. S. & Rye D. B. Review of the relationship of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep to hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Sleep 32, 589–597 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzi F. et al. Is autonomic nervous system involved in restless legs syndrome during wakefulness? Sleep Med 15, 1392–1397, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.06.022 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo B. B. et al. Association of incident cardiovascular disease with periodic limb movements during sleep in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS) study. Circulation 124, 1223–1231, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038968 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza M. et al. Frequent periodic leg movement during sleep is an unrecognized risk factor for progression of atrial fibrillation. PLoS One 8, e78359, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078359 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennestri M. H., Montplaisir J., Colombo R., Lavigne G. & Lanfranchi P. A. Nocturnal blood pressure changes in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology 68, 1213–1218, doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259036.89411.52 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennestri M. H. et al. Blood pressure changes associated with periodic leg movements during sleep in healthy subjects. Sleep Med 14, 555–561, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.02.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza E. et al. EEG and cardiac activation during periodic leg movements in sleep: support for a hierarchy of arousal responses. Neurology 52, 786–791 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza E., Pichot V., Barthelemy J. C., Haba-Rubio J. & Roche F. Cardiovascular variability during periodic leg movements: a spectral analysis approach. Clin Neurophysiol 116, 1096–1104, doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.018 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haba-Rubio J. et al. Prevalence and determinants of periodic limb movements in the general population. Ann Neurol 79, 464–474, doi: 10.1002/ana.24593 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore H. T. et al. Periodic leg movements during sleep are associated with polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD. Sleep 37, 1535–1542, doi: 10.5665/sleep.4006 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otzenberger H. et al. Dynamic heart rate variability: a tool for exploring sympathovagal balance continuously during sleep in men. Am J Physiol 275, H946–950 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobaldini E. et al. Heart rate variability in normal and pathological sleep. Front Physiol 4, 294, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00294 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinder J. et al. Autonomic activity during human sleep as a function of time and sleep stage. J Sleep Res 10, 253–264 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzel T. et al. Modulations of Heart Rate, ECG, and Cardio-Respiratory Coupling Observed in Polysomnography. Front Physiol 7, 460, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00460 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter L. M. et al. Cardiovascular variability during periodic leg movements in sleep in children. Sleep 32, 1093–1099 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N. J., Davies R. J., Fleetham J. A. & Stradling J. R. Periodic movements of the legs during sleep associated with rises in systemic blood pressure. Sleep 14, 163–165 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie S., de Bilbao F., Haba-Rubio J., Ibanez V. & Sforza E. Influence of sleep stage and wakefulness on spectral EEG activity and heart rate variations around periodic leg movements. Clin Neurophysiol 115, 2236–2246, doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.024 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manconi M. et al. Effects of acute dopamine-agonist treatment in restless legs syndrome on heart rate variability during sleep. Sleep Med 12, 47–55, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.03.019 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi R. et al. Advances in heart rate variability signal analysis: joint position statement by the e-Cardiology ESC Working Group and the European Heart Rhythm Association co-endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 17, 1341–1353, doi: 10.1093/europace/euv015 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenza G. et al. Complexity Variability Assessment of Nonlinear Time-Varying Cardiovascular Control. Scientific reports 7, 42779, doi: 10.1038/srep42779 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilchick K. C. et al. Prognostic value of heart rate variability in chronic congestive heart failure (Veterans Affairs’ Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure). Am J Cardiol 90, 24–28 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuanetti G. et al. Prognostic significance of heart rate variability in post-myocardial infarction patients in the fibrinolytic era. The GISSI-2 results. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’ Infarto Miocardico. Circulation 94, 432–436 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinder J., Waloszek J., Woods M. J. & Jordan A. S. Sleep and cardiovascular regulation. Pflugers Arch 463, 161–168, doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1041-3 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bara-Jimenez W., Aksu M., Graham B., Sato S. & Hallett M. Periodic limb movements in sleep: state-dependent excitability of the spinal flexor reflex. Neurology 54, 1609–1616 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provini F. et al. Motor pattern of periodic limb movements during sleep. Neurology 57, 300–304 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Rye D. & Hochman S. Restless legs syndrome: revisiting the dopamine hypothesis from the spinal cord perspective. Neurology 67, 125–130, doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223316.53428.c9 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza G. et al. Central and peripheral nervous system excitability in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.05.010 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akselrod S. et al. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science 213, 220–222 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B. L., Minassian A., Paulus M. P., Geyer M. A. & Perry W. Heart rate variability in bipolar mania and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 44, 168–176, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.07.011 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendra Acharya U., Paul Joseph K., Kannathal N., Lim C. M. & Suri J. S. Heart rate variability: a review. Med Biol Eng Comput 44, 1031–1051, doi: 10.1007/s11517-006-0119-0 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. E., Beightol L. A., Koh J. & Eckberg D. L. Important influence of respiration on human R-R interval power spectra is largely ignored. J Appl Physiol (1985) 75, 2310–2317 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billman G. E. Heart rate variability - a historical perspective. Front Physiol 2, 86, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00086 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana D. S., Alvares G. A. & Heathers J. A. Guidelines for Reporting Articles on Psychiatry and Heart rate variability (GRAPH): recommendations to advance research communication. Transl Psychiatry 6, e803, doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.73 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politano L., Palladino A., Nigro G., Scutifero M. & Cozza V. Usefulness of heart rate variability as a predictor of sudden cardiac death in muscular dystrophies. Acta Myol 27, 114–122 (2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. P. et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med 4, 101–119 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters A. S. et al. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 4, 121–132 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. P. et al. Restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease diagnostic criteria: updated International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) consensus criteria–history, rationale, description, and significance. Sleep Med 15, 860–873, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.03.025 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R., Jaussent I. & Dauvilliers Y. Objective daytime sleepiness in patients with somnambulism or sleep terrors. Neurology 83, 2070–2076, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001019 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi M. et al. The official World Association of Sleep Medicine (WASM) standards for recording and scoring periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS) and wakefulness (PLMW) developed in collaboration with a task force from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). Sleep Med 7, 175–183, doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.01.001 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen M. P., Niskanen J. P., Lipponen J. A., Ranta-Aho P. O. & Karjalainen P. A. Kubios HRV–heart rate variability analysis software. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 113, 210–220, doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M. et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 59, 178–193 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malliani A., Pagani M., Lombardi F. & Cerutti S. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 84, 482–492 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.