Abstract

Aims

Alcohol use disorders are more prevalent in HIV patients than the general population. Both chronic alcohol consumption and HIV infection have been linked to mitochondrial dysregulation; and this is considered an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of muscle myopathy. This study investigated if chronic binge alcohol (CBA) administration impairs the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial homeostasis in SIV-infected macaques.

Methods

Male rhesus macaques were administered daily CBA (to achieve peak blood alcohol concentrations of 50–60 mM within 2 h after start of infusion) or sucrose (SUC) intragastrically 3 months prior to intravenous SIVmac251 inoculation and continued until macaques met criteria for end-stage disease. Skeletal muscle (SKM) samples were obtained at necropsy. Muscle samples were obtained from a cohort of healthy uninfected macaque controls and used for comparison of analyzed variables. Total RNA was extracted and gene expression was analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

The relative expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 beta (PGC-1β) was significantly decreased in the SKM of CBA/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) macaques compared to uninfected controls (P < 0.05). SIV infection resulted in a significant upregulation (P < 0.05) of mitophagy-related gene expression, which was prevented by CBA. CBA suppressed expression of anti-apoptotic genes and increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that SIV infection disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis and when combined with CBA, results in differential expression of genes involved in apoptotic signaling. We speculate that impaired mitochondrial homeostasis may contribute to the underlying pathophysiology of alcoholic and HIV/AIDS associated myopathy.

Short summary

This study investigated if CBA administration dysregulates gene expression associated with mitochondrial homeostasis in the SKM of SIV-infected macaques. The results suggest that SIV infection disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis and when combined with CBA, results in differential expression of genes involved in apoptotic signaling.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 1 million persons are currently living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the USA (CDC, 2013) and ~35% of them meet the criteria for having an alcohol use disorder (AUD) (Lefevre et al., 1995; Bing et al., 2001; Conigliaro et al., 2003; Galvan et al., 2003; Justice et al., 2006). The prevalence of AUD in HIV patients is greater than the prevalence of AUD in the general population (Galvan et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2004). Effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) drug regimens have significantly decreased mortality of HIV-infected individuals, making HIV infection a chronic illness (Walensky et al., 2006; HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration et al., 2010; Nakagawa et al., 2012; Deeks et al., 2013; Fauci and Marston, 2013.) However, prolonged survival has been associated with increased incidence of comorbidities including skeletal muscle (SKM) myopathy and mitochondrial dysfunction (Maagaard and Kvale, 2009; Huang et al., 2012; Keithley and Swanson, 2013). Decreased muscle mass and function remains a strong and consistent predictor of mortality among PLWHA and the frequency of low muscle mass is seen at a much younger age among PLWHA compared to the general population (Tang et al., 2005; Richert et al., 2011). This affects the quality of life and increases the incidence of mortality among these patients. Independently, chronic heavy alcohol consumption and HIV infection both result in significant SKM derangements such as atrophy, weakness and dysfunction (Preedy and Peters, 1994; Scott et al., 2007; Vary and Lang, 2008; Clary et al., 2011; Richert et al., 2011).

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that chronic binge alcohol (CBA) administration exacerbates metabolic dysfunction in non-ART treated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques (Molina et al., 2006, 2008). Specifically, CBA/SIV accentuated a loss of SKM mass (SAIDS wasting) and promoted a dysfunctional SKM phenotype, which was associated with accelerated progression to end-stage disease, compared with isocaloric sucrose SIV-infected (SUC/SIV) macaques (Molina et al., 2008). The mechanisms preceding and leading to accentuated SAIDS wasting in CBA/SIV macaques include localized SKM inflammation, increased proteasomal activity, depletion of SKM antioxidant capacity and increased expression of pro-fibrotic genes (LeCapitaine et al., 2011; Dodd et al., 2014). Additionally, using microarray gene analysis, we showed that CBA alters the expression of genes required for mitochondrial function and energy metabolism in the SKM of SIV-infected macaques (Simon et al., 2015).

Muscle protein balance and growth, critical determinants of muscle mass and function, rely on balanced mitochondrial regulation (homeostasis) (Wagatsuma and Sakuma, 2013; Romanello and Sandri, 2016). Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration has been associated with increased oxidative stress and prevalence of sarcopenia (Richert et al., 2011; Marzetti et al., 2013; Hepple, 2014). At the core of the coordinated network of mitochondrial-related gene regulation are the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) coactivator-1 family of genes (PGC-1α and PGC-1β). The PGC-1 gene family are master regulators of mitochondrial homeostasis via their activation of genes responsible for mitochondrial DNA replication, oxidative phosphorylation proteins and glucose and fatty acid oxidation [e.g. nuclear respiratory factor 1/2 (NRF-1, NRF-2), PPARs, estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM)] (Kelly and Scarpulla, 2004; Finck and Kelly, 2006). As highly dynamic organelles, mitochondria are continuously undergoing fusion and fission, coordinated by dynamin-1-like protein (DRP1), optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) and mitofusin 1/2 (MFN1, MFN2) (Yin and Cadenas, 2015). This remodeling process requires balance and coordination, and when dysregulated by cellular stress, can lead to cell death signaling either through autophagy or apoptosis (Frank et al., 2001; Pernas and Scorrano, 2016). Mitochondria are important organelles that influence cell death control and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mitochondrial dyshomeostasis leads to an imbalance in mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) and apoptosis. Mitophagy is a compensatory ‘quality-control’ mechanism that removes damaged mitochondria from the cell, preventing further ROS generation and cell death. Damaged mitochondria undergo DRP1-mediated fission and removal via autophagosome formation coordinated by transcription factor EB (TFEB) and PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1; Kubli and Gustafsson, 2012; Hood et al., 2016). With increasing cellular stress, mitophagy fails to protect the cell and apoptotic signaling is initiated through inhibition of anti-apoptotic and pro-survival proteins (Beclin-1 and BCL2) and increased pro-apoptotic signaling proteins (BAX and BAK) (Marino et al., 2014). Excessive ROS generation, defective oxidant scavenging, or both, have been implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction underlying sarcopenia and pathogenesis of several myopathies (Calvani et al., 2013; Lightfoot et al., 2015). Excessive alcohol consumption induces damage to mitochondrial DNA and increases cellular oxidative stress (Krahenbuhl, 2001; Hoek et al., 2002; Bailey, 2003; Bonet-Ponce et al., 2015). Furthermore, HIV infection has been associated with increased permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane and initiation of apoptotic cell death (Huang et al., 2012). The studies described in this manuscript tested the hypothesis that CBA leads to dysregulation of mitochondrial gene expression in SKM of SIV-infected rhesus macaques at end-stage disease. We determined SKM mitochondrial gene expression central to mitochondrial homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The SKM used for these studies was obtained from animals used in experiments approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at both Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) in Covington, Louisiana and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC) in New Orleans, Louisiana, and adhered to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals. Four- to six-year-old male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) obtained from TNPRC breeding colonies were used for these studies as previously described (Molina et al., 2008; LeCapitaine et al., 2011).

Experimental protocol

A total of 23 macaques were studied from 3 experimental groups. SKM samples were obtained from a sucrose-administered, SIV-infected group (SUC/SIV, n = 5); a CBA-administered, SIV-infected group (CBA/SIV, n = 6) and a SIV-negative, healthy macaque control group (CTRL, n = 12) used as reference values for comparison of analyzed variables. The cohorts of animals have been used for other studies and results have been previously published (Molina et al., 2008; LeCapitaine et al., 2011; Dodd et al., 2014; Simon et al., 2015). CBA/SIV macaques were administered daily intragastric alcohol at 2.5 g per kg body weight (30% w/v water) or isocaloric sucrose (SUC/SIV) starting 3 months prior to SIV infection (SIVmac251), and continued for the duration of the study. This protocol of intragastric alcohol delivery provided an average of 15% of the animals’ total daily caloric intake and produced peak blood alcohol concentrations of 50–60 mM. SKM samples were obtained at necropsy (~14–18 months post-SIV) when animals met any one of the criteria for euthanasia based on the following: (a) loss of 25% of body weight from maximum body weight since assignment to protocol, (b) major organ failure or medical conditions unresponsive to treatment, (c) surgical complications unresponsive to immediate intervention or (d) complete anorexia for 4 days. All SKM tissue samples were dissected, snap frozen and stored at −80°C until analyses.

SKM gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from SKM using the RNeasy mini universal kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 ug of the resulting total RNA using the Quantitect reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen). Primers were designed to span exon–exon junctions and purchased from IDT (Table 1). The final reactions were made to a total volume of 20 ul with Quantitect SyBr Green polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit and DNase RNase-free water (Qiagen). All reactions were carried out in duplicate on a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) for quantitative PCR (qPCR) detection. qPCR data were analyzed using the comparative Ct (delta–delta-Ct) method. Target genes were compared with the endogenous control, ribosomal protein S13 (RPS13) and experimental group values were normalized to CTRL values.

Table 1.

qPCR primers (M. mulatta)

| Target gene | 5′ to 3′ | Primer sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Autophagy related 5 (ATG5) | Forward | ACCAGAAACACTTCGCTGCT |

| Reverse | ATGATGGCAGTGGAGGAAAG | |

| Beclin-1 | Forward | AGCTTTTGTCCACTGCTCCTC |

| Reverse | GGTTGAGAAAGGCGAGACA | |

| B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) | Forward | GGCCAGGGTCAGAGTTAAATA |

| Reverse | GAGGTTCTCGGATGTTCTTCTC | |

| BCL2 associated agonist of cell death (BAD) | Forward | TGGTGGGATCGGAACTT |

| Reverse | TCCGCCCATATCCAAGAT | |

| BCL2 antagonist/killer (BAK) | Forward | CCATGCTGGAGTGAGAATAAA |

| Reverse | TTCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTAC | |

| BCL2 associated X protein (BAX) | Forward | GAGCTGCAGAGGATGATTG |

| Reverse | GCCTTGAGCACCAGTTT | |

| Caspase-9 | Forward | GAGGAAGAGGGACAGATGAATG |

| Reverse | AGGTTAATCCCTGCCCTAGA | |

| DRP1 | Forward | TCCTCTCCCATCCATCTTATC |

| Reverse | TTCTTGTACTCCTCCACCTC | |

| ERRα | Forward | TGCACTGGTGTCTCATCT |

| Reverse | GAAACCTGGGATGCTCTTG | |

| Glutathione synthetase (GSS) | Forward | CGGACAGTGAGATGTAGGAAAG |

| Reverse | GAGTCTCCACACAACCAGAATAG | |

| MFN1 | Forward | CTCCAGCAACACCAGATAAT |

| Reverse | GTCCAGGACAGTCTTTCATAC | |

| MFN2 | Forward | CAGGAGGAGTTCATGGTTTC |

| Reverse | AGACGCTCATAGACGTAGAG | |

| NRF-1 | Forward | CACGCACAGTATAGCTCATC |

| Reverse | GTAGCCCTCAAGTTTACTCAC | |

| NRF-2 | Forward | CTACTTGGCCTCAGTGATTC |

| Reverse | R-GACAAGGGTTGTACCGTATC | |

| OPA1 | Forward | GGACAGCTTGAGGGTTATTC |

| Reverse | GTTCTTGGGTCCGATTCTTC | |

| PPARα | Forward | CCTGCGAACATGACATAGAA |

| Reverse | CCATACACAGTGTCTCCATATC | |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) | Forward | TGAACTGAGGGACAGTGATTTC |

| Reverse | CCCAAGGGTAGCTCAGTTTATC | |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-beta (PGC-1β) | Forward | GACAAGGCCCTTCCAATATG |

| Reverse | CAGCAGTTTCAAGTCTCTCTC | |

| PINK1 | Forward | ACAGGCTCACAGAGAAGT |

| Reverse | CGTTTCACACTCCAGGTTAG | |

| Ribosomal protein S13 (RPS13) | Forward | TCTGACGACGTGAAGGAGCAGATT |

| Reverse | TCTCTCAGGATCACACCGATTTGT | |

| Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) | Forward | GACAAACCTCAGCCCTAATG |

| Reverse | CCGTCAGCTTCTCCTTAAAC | |

| TFAM | Forward | CAGCTAACTCCAGATGAGATTAC |

| Reverse | GTGATTCACCCTTAGCTTCTT | |

| TFEB | Forward | GCAACAGTGCTCCCAATA |

| Reverse | GACATCATCAAACTCCCTCTC |

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 and data are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of gene expression was determined using one-way ANOVA. Fisher's least significant difference post hoc test was used to determine pairwise differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics version 22, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

CBA dysregulates mitochondrial-related gene expression in the SKM of SIV-infected macaques at end stage

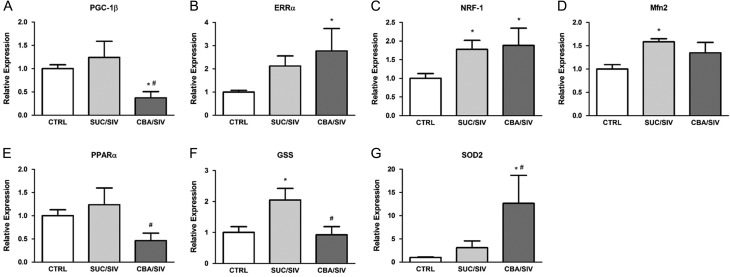

SIV infection resulted in significant upregulation of SKM expression of NRF-1, mitofusin 2 (MFN2) and glutathione synthetase (GSS) compared to uninfected controls. CBA resulted in significant downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC)-1ß compared to uninfected controls and prevented the SIV-induced upregulation of GSS. Moreover, CBA resulted in significant upregulation of ERRα, NRF-1 and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 1). There were no differences between groups for PGC-1α, NRF-2 or TFAM expression. Gene expression of mitochondrial dynamin like GTPase (OPA1) and MFN1 was below the level of detection.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial-related gene expression. PGC-1β (A) expression was significantly decreased in SKM of CBA/SIV macaques compared to SUC/SIV and CTRL. ERRα (B) and NRF-1 (C) were significantly increased in SKM of CBA/SIV macaques compared to CTRL. PPARα (E) and GSS (F) expression was significantly lower in SKM of CBA/SIV compared to SUC/SIV. SOD2 (G) expression was significantly greater in SKM of CBA/SIV macaques compared to SUC/SIV and CTRL. The SKM of SUC/SIV had significantly increased expression of NRF-1, MFN2 (D) and GSS compared to CTRL. *Significant (P < 0.05) difference from CTRL. #Significant (P < 0.05) difference between CBA/SIV and SUC/SIV. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

CBA prevented mitophagy-related gene expression in the SKM of SIV-infected macaques at end stage

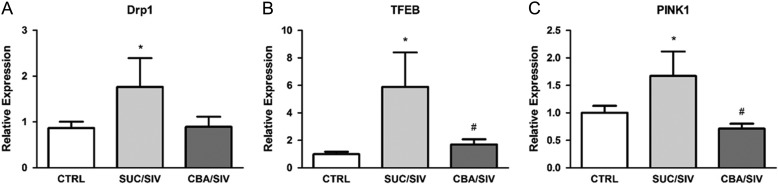

SIV infection resulted in a significant upregulation of mitophagy-related gene expression including DRP1, TFEB and PINK1. CBA prevented the SIV-induced increased expression of TFEB and PINK1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mitophagy-related gene expression. DRP1 (A), TFEB (B) and PINK1 (C) expression was significantly greater in SKM of SUC/SIV compared to CTRL. TFEB and PINK1 expression was significantly lower in SKM of CBA/SIV compared to SKM of SUC/SIV macaques. *Significant (P < 0.05) difference from CTRL. #Significant (P < 0.05) difference between CBA/SIV and SUC/SIV. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

CBA increases apoptosis-related gene expression in the SKM of SIV-infected macaques at end stage

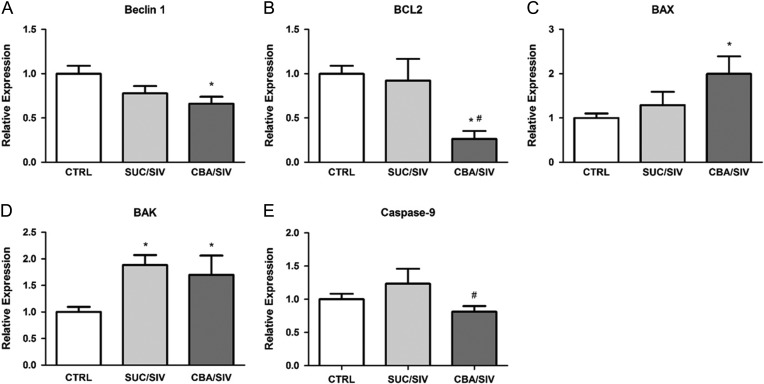

SIV infection resulted in significant upregulation of BCL2 antagonist/killer (BAK) without altering that of Beclin-1, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), BCL2 associated X protein (BAX) or Caspase-9. CBA resulted in significant suppression of Beclin-1 and BCL2 compared to uninfected controls. CBA resulted in a significant reduction of Caspase-9 compared to SUC/SIV. In contrast, CBA resulted in marked upregulation of BAX and BAK expression compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 3). No significant differences were detected between groups for BAD or ATG5 expression.

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis-related gene expression. Beclin-1 (A) expression was significantly lower in CBA/SIV compared to CTRL. BCL2 (B) expression was significantly lower in CBA/SIV SKM compared to that in SUC/SIV and CTRL. BAX (C) and BAK (D) expression was significantly greater in SKM of CBA/SIV compared to SKM of SUC/SIV and CTRL. Caspase-9 (E) was lower in CBA/SIV compared to SUC/SIV. *Significant (P < 0.05) difference from CTRL. #Significant (P < 0.05) difference between CBA/SIV and SUC/SIV. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

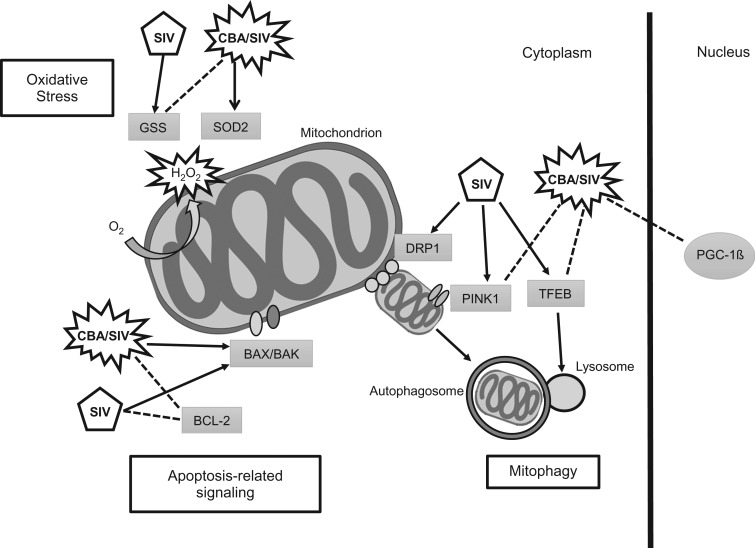

This study examined the effects of CBA on expression of mitochondria-related genes in SKM of non-ART treated SIV-infected male rhesus macaques at end-stage disease. SIV infection was associated with increased expression of NRF-1, MFN2, GSS and mitophagy-related genes compared to uninfected controls. CBA resulted in downregulation of PGC-1β and upregulation of ERRa, NRF-1 and SOD2 compared to uninfected controls. CBA prevented the SIV-induced upregulation of GSS and mitophagy-related gene expression. Additionally, CBA resulted in suppression of anti-apoptotic gene expression and upregulation of pro-apoptotic gene expression. These findings suggest that SIV infection disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis and triggers compensatory mitophagy and antioxidant gene upregulation. When combined with CBA (CBA/SIV), SKM showed differential expression of genes involved in apoptotic signaling, which could potentially contribute to the underlying pathophysiology of CBA-induced accelerated SKM wasting at end-stage SIV disease (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pictorial summary of main SIV and CBA effects on SKM gene expression and their potential impact on regulation mitochondrial homeostasis. Three main pathways are predicted to be impacted by the observed alterations in gene expression in addition to the overall CBA/SIV-induced decreased expression of PGC-1ß, a master regulator of mitochondrial homeostasis; mitophagy, apoptosis and oxidative stress. SIV increased expression of mitophagy-related genes (DRP1, PINK1 and TFEB), while CBA/SIV prevented the increase of PINK1 and TFEB. DRP1 regulates the fission of damaged mitochondria and initiates mitophagy. As the outer mitochondrial membrane becomes dysfunctional PINK1 is activated and contributes the formation of an autophagosome. TFEB is an activator of lysosomal biogenesis which allows the fusing of the autophagosome with lysosomes for mitophagy. SIV and CBA/SIV decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2. CBA/SIV upregulated both BAX and BAK gene expression. Apoptotic-related signaling is initiated in response to increased cellular stress and permeabilization (BAX/BAK) of the outer mitochondrial membrane. SIV increased expression of GSS. CBA/SIV prevented the increase in GSS while increasing SOD2 gene expression. Damaged mitochondria generate increased levels of the ROS superoxide, which is converted to H2O2 by SOD2. GSS is a precursor to glutathione, which contributes to scavenging of H2O2. These results suggest that SIV infection disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis and when combined with CBA, results in differential expression of genes involved in mitophagy, apoptosis and anti-oxidative capacity.

Mitohormesis, the adaptive response to disruptions to the dynamic balance of mitochondrial signaling, increases cellular tolerance to oxidative stressors (Barbieri et al., 2014). Low-level oxidative stress (ROS) can signal a mitohormetic response, resulting in improved mitochondrial functioning (e.g. adenosine triphosphate production and antioxidant capacity). Canonically, this is achieved through chronic exercise training (Barbieri et al., 2014; Merry and Ristow, 2016) and represents an advantageous response to oxidative stress in the cell. However, levels of ROS that exceed the mitochondria's ability to maintain homeostasis have been implicated as a major factor in several metabolic diseases (Nunnari and Suomalainen, 2012). Previous studies from our laboratory reported that SIV infection resulted in a 2.5-fold reduction in SKM antioxidant capacity and this was further decreased (~7-fold reduction) by CBA (LeCapitaine et al., 2011), suggesting an alcohol-induced upregulation in ROS production. This is supported by the observed expression of genes related to antioxidant signaling in the present study. We found that CBA prevented an increase in GSS, a precursor to glutathione and increased SOD2 expression. The increase in SOD2 expression in CBA/SIV macaques suggests increased presence of the superoxide anion (Kowaltowski et al., 2009) and is in agreement with our previous findings of decreased antioxidant capacity in muscle of CBA/SIV macaques (LeCapitaine et al., 2011). In the present study, CBA caused a reduction in PGC-1β expression compared to uninfected controls and SUC/SIV. PGC-1β is a member of the PPARγ coactivator-1 family of genes (PGC-1α and PGC-1β), master regulators of mitochondrial homeostasis and important mediators of mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of oxidative phosphorylation proteins (Kelly and Scarpulla, 2004; Finck and Kelly, 2006). PGC-1β deficiency in SKM has been reported to result in abnormal mitochondrial structure, reduced antioxidant defense and increased oxidative stress (Gali Ramamoorthy et al., 2015). Thus, our findings suggest that compensatory mitochondrial biogenesis is likely impaired in muscle of CBA/SIV macaques and may be an important mechanism contributing to previously reported pro-oxidative and catabolic milieu.

Cellular stressors, such as increased ROS production, initiate signal transduction required for mitophagy. This adaptive response removes damaged mitochondria which could otherwise contribute to further escalation in ROS generation (Marino et al., 2014). Our results show an SIV-induced increase of genes related to mitophagy signaling that was partially prevented by CBA. Autophagy pathways precede apoptosis, can inhibit apoptotic signaling and often represent an avoidance of cell death (Marino et al., 2014). Under extraordinary cellular stress conditions, autophagy signaling (including mitophagy) pathways are inhibited and pro-apoptotic signaling activated. In many tissues, caspase activation is highly associated with apoptosis. However, caspase-independent apoptosis, involving the release of cell-toxic proteins (e.g. EndoG and AIF), has been implicated as an important factor in muscle atrophy (Dupont-Versteegden, 2006). These pro-apoptotic proteins are able to translocate into the nucleus, causing damage to DNA, and ultimately cell death (Dupont-Versteegden, 2006). Central to the initiation of this apoptotic cascade is the activation of BAX and BAK, which allow the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane and release of pro-apoptotic proteins (Chipuk et al., 2010). This permeabilization represents a ‘point of no return’ and, thus, a critical component of cell death signaling. In the present study, we found that anti-apoptotic genes Beclin-1 and BCL2 were decreased and pro-apoptotic genes BAX and BAK were increased in SKM of CBA/SIV. These findings are supportive to our hypothesis that CBA-induced mitochondrial dysregulation may contribute to metabolic dysfunction and accentuated muscle wasting in SIV-infected macaques.

The current study demonstrates CBA-induced mitochondrial gene dysregulation in non-ART treated SIV-infected macaques at end-stage disease. Limitations of this study include the lack of mechanistic experiments to elucidate the functional relevance of dysregulated mitochondrial gene expression and analysis of protein expression. Future studies will utilize in vitro models to analyze protein abundance and mechanistically investigate chronic alcohol-induced mitophagy/apoptosis signaling and how their imbalance contributes to SKM wasting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Gregory Bagby and Dr Steve Nelson, Comprehensive Alcohol Research Center, LSUHSC, for their administrative support and animal study design and Dr Jason Dufour, DVM, DACLAM, Tulane National Research Primate Center for veterinary expertise. We are thankful to Larissa Devlin, Wayne A. Cyprian and Nancy Dillman for excellent care of study animals and the TNPRC Pathology Laboratory. From LSUHSC-NO, we are thankful for the technical support of Kejing Song, Curtis Vande Stouwe, Jean Carnal, Jane Schexnayder, Amy B. Weinberg and Rhonda R. Martinez.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P60 AA009803, P51 RR000164. T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship AA07577.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bailey SM. (2003) A review of the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in alcohol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Free Radic Res 37:585–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri E, Sestili P, Vallorani L, et al. (2014) Mitohormesis in muscle cells: a morphological, molecular, and proteomic approach. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 3:254–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. (2001) Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet-Ponce L, Saez-Atienzar S, da Casa C, et al. (2015) On the mechanism underlying ethanol-induced mitochondrial dynamic disruption and autophagy response. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852:1400–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvani R, Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, et al. (2013) Mitochondrial pathways in sarcopenia of aging and disuse muscle atrophy. Biol Chem 394:393–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). HIV Surveillance Report, 2013; vol. 25. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Published February 2015 (March 2016, date last accessed).

- Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, et al. (2010) The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell 37:299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary CR, Guidot DM, Bratina MA, et al. (2011) Chronic alcohol ingestion exacerbates skeletal muscle myopathy in HIV-1 transgenic rats. AIDS Res Ther 8:30. -6405-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, et al. (2003) How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: do health care providers know who is at risk. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 33:521–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV (2013) The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 382:1525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd T, Simon L, LeCapitaine NJ, et al. (2014) Chronic binge alcohol administration accentuates expression of pro-fibrotic and inflammatory genes in the skeletal muscle of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:2697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Versteegden EE. (2006) Apoptosis in skeletal muscle and its relevance to atrophy. World J Gastroenterol 12:7463–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci AS, Marston HD (2013) Achieving an AIDS-free world: science and implementation. Lancet 382:1461–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck BN, Kelly DP (2006) PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest 116:615–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, et al. (2001) The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell 1:515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gali Ramamoorthy T, Laverny G, Schlagowski AI, et al. (2015) The transcriptional coregulator PGC-1beta controls mitochondrial function and anti-oxidant defence in skeletal muscles. Nat Commun 6:10210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Burnam MA, Bing EG (2003) Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms and drug dependence or heavy drinking among HIV-positive people. J Psychoactive Drugs 35:153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. (2004) The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend 74:223–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepple RT. (2014) Mitochondrial involvement and impact in aging skeletal muscle. Front Aging Neurosci 6:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration, Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, et al. (2010) The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 24:123–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek JB, Cahill A, Pastorino JG (2002) Alcohol and mitochondria: a dysfunctional relationship. Gastroenterology 122:2049–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood DA, Tryon LD, Carter HN, et al. (2016) Unravelling the mechanisms regulating muscle mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochem J 473:2295–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Chiang SF, Lin TY, et al. (2012) HIV-1 Vpr triggers mitochondrial destruction by impairing Mfn2-mediated ER-mitochondria interaction. PloS One 7:e33657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Lasky E, McGinnis KA, et al. (2006) Medical disease and alcohol use among veterans with human immunodeficiency infection: A comparison of disease measurement strategies. Med Care 44:S52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley JK, Swanson B (2013) HIV-associated wasting. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 24:S103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DP, Scarpulla RC (2004) Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev 18:357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, et al. (2009) Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 47:333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahenbuhl S. (2001) Alcohol-induced myopathy: what is the role of mitochondria. Hepatology 34:210–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB (2012) Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res 111:1208–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCapitaine NJ, Wang ZQ, Dufour JP, et al. (2011) Disrupted anabolic and catabolic processes may contribute to alcohol-accentuated SAIDS-associated wasting. J Infect Dis 204:1246–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre F, O'Leary B, Moran M, et al. (1995) Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med 10:458–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot AP, McArdle A, Jackson MJ, et al. (2015) In the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), do reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to muscle weakness. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maagaard A, Kvale D (2009) Long term adverse effects related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: clinical impact of mitochondrial toxicity. Scand J Infect Dis 41:808–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, et al. (2014) Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15:81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M, et al. (2013) Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45:2288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry TL, Ristow M (2016) Mitohormesis in exercise training. Free Radic Biol Med 98:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, Lang CH, McNurlan M, et al. (2008) Chronic alcohol accentuates simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated wasting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32:138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, McNurlan M, Rathmacher J, et al. (2006) Chronic alcohol accentuates nutritional, metabolic, and immune alterations during asymptomatic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30:2065–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa F, Lodwick RK, Smith CJ, et al. (2012) Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. AIDS 26:335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari J, Suomalainen A (2012) Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 148:1145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernas L, Scorrano L (2016) Mito-morphosis: mitochondrial fusion, fission, and cristae remodeling as key mediators of cellular function. Annu Rev Physiol 78:505–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preedy VR, Peters TJ (1994) Alcohol and muscle disease. J R Soc Med 87:188–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richert L, Dehail P, Mercie P, et al. (2011) High frequency of poor locomotor performance in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 25:797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanello V, Sandri M (2016) Mitochondrial quality control and muscle mass maintenance. Front Physiol 6:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WB, Oursler KK, Katzel LI, et al. (2007) Central activation, muscle performance, and physical function in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Muscle Nerve 36:374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon L, Hollenbach AD, Zabaleta J, et al. (2015) Chronic binge alcohol administration dysregulates global regulatory gene networks associated with skeletal muscle wasting in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. BMC Genomics 16:1097. -015-2329-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AM, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, et al. (2005) Increasing risk of 5% or greater unintentional weight loss in a cohort of HIV-infected patients, 1995 to 2003. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 40:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vary TC, Lang CH (2008) Assessing effects of alcohol consumption on protein synthesis in striated muscles. Methods Mol Biol 447:343–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma A, Sakuma K (2013) Mitochondria as a potential regulator of myogenesis. ScientificWorldJournal 2013:593267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, et al. (2006) The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis 194:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Cadenas E (2015) Mitochondria: the cellular hub of the dynamic coordinated network. Antioxid Redox Signal 22:961–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]