Abstract

Objective

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine whether IRISS (Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status), a positive affect skills intervention, improved positive emotion, psychological health, physical health, and health behaviors in people newly diagnosed with HIV.

Method

159 participants who had received an HIV diagnosis in the past 3 months were randomized to a 5-session, in-person, individually-delivered positive affect skills intervention or an attention-matched control condition.

Results

For the primary outcome of positive affect, the group difference in change from baseline over time did not reach statistical significance (p = .12; d = .30). Planned secondary analyses within assessment point showed that the intervention led to higher levels of past-day positive affect at 5, 10, and 15 months post diagnosis compared to an attention control. For antidepressant use, the between group difference in change from baseline was statistically significant (p = .006; d = −.78 baseline to 15 months) and the difference in change over time for intrusive and avoidant thoughts related to HIV was also statistically significant (p = .048; d = .29). Contrary to findings for most health behavior interventions in which effects wane over the follow up period, effect sizes in IRISS seemed to increase over time for most outcomes.

Conclusions

This comparatively brief positive affect skills intervention achieved modest improvements in psychological health, and may have the potential to support adjustment to a new HIV diagnosis.

Keywords: positive affect, positive emotion, randomized controlled trial, HIV diagnosis, stress

Over the past few decades, it has become clear that positive affect, defined as subjective positively valenced feelings that range from happy, calm, and satisfied, to excited and thrilled, is uniquely related to better psychological and physical well-being, independent of the effects of negative affect (Folkman, 1997; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Fredrickson, 1998; Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008; Tice, Baumeister, Shmueli, & Muraven, 2007; Wichers et al., 2007; Zautra, Johnson, & Davis, 2005). Positive affect and related constructs like optimism are associated with a host of beneficial outcomes including better relationships, more creativity, better quality of work, higher likelihood of prosocial behavior (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005), better physical health (Pressman & Cohen, 2005) and even a lower risk of mortality in healthy as well as chronically ill samples (Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Liu et al., 2016; Moskowitz, 2003; Moskowitz, Epel, & Acree, 2008; Steptoe & Wardle, 2011).

Accordingly, researchers are developing interventions that specifically target positive affect for people living with chronic conditions such as diabetes (Cohn, Pietrucha, Saslow, Hult, & Moskowitz, 2014; Huffman, DuBois, Millstein, Celano, & Wexler, 2015), heart disease (Huffman et al., 2011; Peterson et al., 2012), hypertension (Boutin-Foster et al., 2016; Ogedegbe et al., 2012), substance use (Carrico et al., 2015; Krentzman et al., 2015), schizophrenia (Caponigro, Moran, Kring, & Moskowitz, 2013) and depression (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Meta analyses indicate that these interventions are effective for increasing positive affective states and reducing negative states, with small to medium effect sizes that are sustained over time (Bolier et al., 2013; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). However, the evidence base for positive psychological interventions is still fairly new and has suffered from a number of methodological weaknesses including small sample sizes, lack of randomized trials, and failure to report intent-to-treat analyses (Bolier et al., 2013). In addition, few studies of positive affect interventions address questions of whether improvements in the targeted positive psychological construct mediate the effects of the intervention on health-related outcomes.

In the present study, we address a number of these concerns and present results from a randomized controlled trial of a theory-based (Folkman, 1997; Fredrickson, 1998), positive affect intervention for people coping with health-related stress. The multicomponent intervention presented here, called IRISS (Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status), consisted of instruction in eight skills intended to increase the frequency of daily experience of positive emotion in the months following HIV diagnosis, a normatively stressful period for most individuals (Bhatia, Hartman, Kallen, Graham, & Giordano, 2011; Ironson, LaPerriere, Antoni, & O'Hearn, 1990; Jacobsen, Perry, & Hirsch, 1990; LaPerriere, Antoni, Schneiderman, & Ironson, 1990; Ostrow, Joseph, Kessler, & Soucy, 1989; Perry, Fishman, Jacobsberg, & Frances, 1992; Rundell, Paolucci, Beatty, & Boswell, 1988). Even years after diagnosis, people living with HIV report higher levels of depressive mood and negative affect (Bing et al., 2001; Do et al., 2014) which is associated with increased sexual risk behavior (Marks, Bingman, & Duval, 1998), poorer linkage to HIV care (Bhatia et al., 2011) and more rapid HIV disease progression (Ickovics et al., 2001; Leserman, 2007; Mayne, Vittinghoff, Chesney, Barrett, & Coates, 1996). On the other hand, among people living with HIV, positive affect and related positive constructs are uniquely associated with lower levels of depression (Li, Mo, Wu, & Lau, 2016), slower disease progression (Ironson et al., 2005; Ironson & Hayward, 2008), better success along the HIV continuum of care (Carrico & Moskowitz, 2014; Gonzalez et al., 2004), including higher likelihood of achieving suppressed viral load (Wilson et al., 2016), and lower risk of mortality (Moskowitz, 2003), independent of the effects of negative affect.

Researchers have begun to demonstrate the efficacy of interventions that specifically target positive affect for people living with chronic physical and mental health conditions (Boutin-Foster et al., 2016; Caponigro et al., 2013; Carrico et al., 2015; Cohn et al., 2014; Huffman et al., 2015; Huffman et al., 2011; Krentzman et al., 2015; Ogedegbe et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2012; Seligman et al., 2005). Although most of these studies have been small pilot feasibility and preliminary efficacy studies, Charlson and colleagues have conducted larger-scale randomized trials of a positive affect intervention in samples of people with chronic illness and hypothesized that the intervention would have beneficial effects on health behaviors (Mancuso et al., 2012; Ogedegbe et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2012). This intervention was associated with greater likelihood of achieving exercise recommendations in patients who had undergone coronary angioplasty (Peterson et al., 2012), significant improvements in adherence to medication among African Americans with hypertension (Ogedegbe et al., 2012), but was not associated with decreases in blood pressure in patients with hypertension (Boutin-Foster et al., 2016) or increased physical activity in patients with asthma (Mancuso et al., 2012). In an analysis that combined the initial three trials, Peterson et al. (2013) demonstrated that those whose positive affect declined over 12 months were less likely to achieve behavioral health goals (e.g., exercise, medication adherence), but it was not clear whether the intervention effects were mediated through increased (or maintained) positive affect. Furthermore, in addition to telephone calls that helped participants engage in self-affirmation, a core aspect of the intervention was to send small gifts to the participants with the intention of increasing positive affect. Although receiving an unexpected gift may cause a momentary increase in positive affect, the approach is unlikely to lead to sustained increases in psychological well-being after the intervention ends.

Grounded in theory and building on empirical findings of a link between positive affect and adaptive outcomes for people coping with significant stress, we developed a positive affect skills intervention for people coping with health-related or other life stress. The intervention consists of five sessions in which participants learn eight empirically-supported behavioral and cognitive “skills” that they are encouraged to practice to achieve a sustained increase in positive affect: 1) noting daily positive events; 2) capitalizing on or savoring positive events; 3) gratitude; 4) mindfulness; 5) positive reappraisal; 6) focusing on personal strengths; 7) setting and working toward attainable goals; and 8) small acts of kindness (Moskowitz et al., 2014). The intervention has demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in pilot tests in a number of different samples (Caponigro et al., 2013; Carrico et al., 2015; Cheung et al., in press; Cohn et al., 2014; Dowling et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2012). In the present study, we conducted a randomized controlled trial of the IRISS intervention, the positive affect skills intervention developed for people newly diagnosed with HIV. Specifically, we hypothesized that, compared to participants in an attention-matched control condition, those randomized to receive IRISS would report increased positive affect, our primary outcome measure. We also hypothesized improvements in secondary outcomes of depression, antidepressant and antianxiety use, intrusive and avoidant thoughts about HIV, as well as improved physical health and health behaviors in the 15 months after HIV diagnosis. We hypothesized that increases in positive affect would mediate the effect of the intervention on the secondary outcomes.

METHOD

Participants

To be enrolled in this study, participants had to: a) have been informed they were HIV positive within the past 12 weeks; b) speak English or Spanish; c) be 18 years of age or older; and d) be able to provide informed consent to be a research participant. Exclusion criteria included: severe cognitive impairment, active psychosis, or unmedicated bipolar disorder (because of concerns that intentionally increasing positive affect could potentially trigger mania.) All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at sites where data were collected and sessions were administered and all participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT00720733.)

Participants were recruited in the San Francisco Bay area through HIV testing sites and clinics, community based organizations, newsletters, and flyers. Potential participants were told the goal of the study was to find out what's effective in helping people cope with a new diagnosis. Study materials and consent forms explained that participants would be assigned to one of two conditions in which they would either “learn skills to better manage your mood” or “talk about what's going on since testing positive.” Interested participants were referred to the study for screening. Participants who were eligible were then scheduled for their first assessment session.

Scheduled assessments took place at four points: baseline (at entry into the study approximately two months post diagnosis and prior to the intervention or control sessions); five months post diagnosis (approximately two weeks after the conclusion of the intervention or control sessions); 10 months post diagnosis, and 15 months post diagnosis. CD4 and viral load were collected at baseline, 10, and 15 months post diagnosis. Assessments were conducted oneon-one by trained interviewers who were blind to study condition until the end of the 15-month interview. All interviews were audio recorded for fidelity assessments and later transcription and analysis of the narrative portions.

At the first assessment session, participants completed informed consent procedures, had an initial blood draw for CD4 and viral load, and completed the baseline interview. Once the baseline assessment was completed, the participant was randomly assigned to the intervention or control condition using block randomization with randomly varying block sizes of 2, 4, or 6, in order to prevent the project director from predicting what the next assignment would be. The random number sequence was generated by the study statistician. Participants were paid $20 for each intervention/control session, $25 for the first two assessments, and $50 for each of the assessments at 10 months and 15 months, for a total of $250 for completing the entire study. In addition, we reimbursed for transportation and provided a snack for each assessment and intervention/control session.

Content of the intervention

The IRISS intervention consisted of five in-person sessions and one phone session in which facilitators taught participants eight empirically supported behavioral and cognitive skills for increasing positive affect. The eight skills are: 1) noting daily positive events (Krause, 1998; Lewinsohn & Amenson, 1978; Lewinsohn, Hoberman, & Clarke, 1989; Lewinsohn, Sullivan, & Grosscup, 1980); 2) capitalizing on or savoring positive events (Bryant, 1989; Langston, 1994); 3) gratitude (Emmons, 2007; 2006; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005); 4) mindfulness (Cresswell, Myers, Cole, & Irwin, 2009; Grossman, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer, Raysz, & Kesper, 2007; Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007); 5) positive reappraisal (Antoni, Ironson, & Schneiderman, 2007; Carver & Scheier, 1994; Chesney, Chambers, Taylor, Johnson, & Folkman, 2003; Chesney, Folkman, & Chambers, 1996; Folkman, 1997; Moskowitz, Folkman, Collette, & Vittinghoff, 1996; Moskowitz, Hult, Bussolari, & Acree, 2009; Sears, Stanton, & Danoff-Burg, 2003); 6) focusing on personal strengths (Koole, Smeets, van Knippenberg, & Dijksterhuis, 1999; Taylor et al., 1992; Taylor & Lobel, 1989); 7) setting and working toward attainable goals (Antoni et al., 2007; Brunstein, Schultheiss, & Grassmann, 1998; Carver & Scheier, 1990; Lent et al., 2005; Moskowitz et al., 2009; Sikkema, Kalichman, Kelly, & Koob, 1995); and 8) small acts of kindness (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003; Moen, Dempster-McCain, & Williams, 1993; Musick & Wilson, 2003; Oman, Thoresen, & McMahon, 1999; Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005). The content of each intervention session is summarized in Table 1 and rationale for inclusion of each of the positive affect skills is provided elsewhere (Moskowitz et al., 2014; Moskowitz et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Overview of Intervention sessions, Goals, and Home Practice

| Session Number | Skills | Goals of session | Home Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1. Positive events 2. Capitalizing 3. Gratitude |

Recognize positive events and the associated positive affect; practice ways to amplify the experience of positive events; and learning to practice gratitude. | Noting a positive event each day and writing about it (capitalizing); starting a daily gratitude journal and daily emotion reports. The gratitude list home practice continues through the rest of the 5-week intervention period. |

| 2 | 4. Mindfulness | Learn and practice the awareness and nonjudgment components of mindfulness | Daily informal mindfulness activities, a 10-minute formal breath awareness activity, continuing the gratitude journal and daily emotion reports. Participants are instructed to continue the daily breath awareness activity throughout the remaining weeks. |

| 3 | 5. Positive Reappraisal | Understanding positive reappraisal and the idea that different forms of positive reappraisal can all lead to increased positive affect in the face of stress | Reporting a relatively minor stressor each day, then listing ways in which the event can be positively reappraised. The daily formal mindfulness practice, gratitude journal, and the emotion reports continue. |

| 4 | 6. Personal Strengths 7. Achievable Goals |

Participant lists his or her personal strengths and notes how they may have used these strengths recently; Understanding characteristics of attainable goals and setting some goals for the week. | Listing a strength each day and how it was “expressed” behaviorally, working toward one of the attainable goals each day, and noting progress each day. The 10-minute mindful breathing, the gratitude journal, and the daily affect reports continue this week. |

| 5. | 8. Acts of Kindness | Understanding that small acts of kindness can have a big impact on positive emotion | Practicing a small act of kindness each day, mindful breathing, gratitude journal, and daily emotion reports continue. |

| 6. | Phone Call: Planning for how to continue practicing skills |

Content of the Control Sessions

Participants in the control condition also had five one-onone sessions with a facilitator, followed by a sixth session by phone, producing a time/attention-matched comparison condition. The sessions were comparable in length to the intervention sessions (approximately one hour) but consisted of an interview and did not have any didactic portion or skills practice. These sessions were designed to remove the positive affect component of the intervention, while maintaining any nonspecific effects arising from one-on-one contact with a sympathetic facilitator to share one's personal stories and concerns. The interviews included 1) Life history (qualitative); 2) Health history (qualitative), Use of complementary and alternative medicine, physical activity; 3) Personality and diet questionnaires; 4) Social support and social network; 5) Meaning and purpose and 6) Ranking sessions, whether they would recommend the sessions to a friend, and rating sessions on enjoyment (conducted by phone). Home practice for the control group consisted of brief daily emotion reports over the 5 weeks of the control sessions.

Intervention/Control Facilitators

Over the course of the study there were six facilitators who delivered both the IRISS and the control sessions. Two participants had some or all of their sessions facilitated by the project director for confidentiality or timing reasons. Facilitators had extensive backgrounds in community-based or public health research and participated in at least 40 hours of training specific to delivery of this intervention. Additional details on training are described in Moskowitz et al. (2014). There were a total of 799 sessions conducted over the course of the study: 394 IRISS sessions and 404 control sessions. On average, a facilitator conducted 65 IRISS sessions (SD=.49) and 66.5 control sessions (SD=.49).

Intervention and Control Session Fidelity

Audio recordings of facilitator sessions were reviewed by the project director to assess adherence to the protocol, delivery, interpersonal skills, facilitator/participant rapport, and session flow. The first three control sessions for each facilitator and all six sessions of the first three intervention participants (for each facilitator) were reviewed immediately. This was followed by regular (weekly, then monthly) reviews of selected sessions for both the control and intervention sessions thereafter. Fidelity was assessed qualitatively with a checklist and comments for each component of a session but quantitative ratings were not tracked.

Measures

Psychological Health

Positive and Negative Affect were measured using two recall periods, past-week and past-day. Past-week positive and negative affect were measured with a modified version of the Differential Emotions Scale (DES; Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003) that assesses nine positive emotions (amused, awe, content, glad, grateful, hopeful, interested, love, and pride) and eight negative emotions (angry, ashamed, contempt, disgust, embarrassed, repentant, sad, and scared). Participants rated how frequently they felt that particular emotion in the past week on a 5-point scale: 0=never to 4=most of the time.

Past-day positive and negative affect was measured using the DES but administered with the Day Reconstruction Method (DRM; Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004) in which participants report events and the associated emotions for each event from the previous day. We created composite measures of participants’ past day affect by aggregating the mean positive and negative affect ratings across all episodes recounted from that day.

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) was used to measure depressive symptoms during the past week. Participants were asked to report whether they were currently taking any prescription medications other than those specifically for HIV. If yes, they were asked whether they were taking anti-depressants or anti-anxiety drugs. These responses were coded “yes” or “no”. Intrusive and Avoidant thoughts about HIV were measured with the 15-item Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979).

Physical Health and Health Behaviors

Physical Symptoms were assessed using a modification of the scale developed by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (Justice et al., 2001). Participants were asked whether they had experienced each of a series of 38 possible symptoms in the preceding 30 days and how much the problem bothered them. For the present analyses, we calculated a total bother score. We collected CD4 and viral load data at baseline, 10- and 15-months post diagnosis. In some cases, instead of having blood drawn for the study, participants chose to allow access to their medical records and we used the CD4 and viral load values that were drawn closest in time to the assessment. Viral load was dichotomized into less than 200 cells/ mL or above as transmission of HIV is extremely unlikely if viral load is below 200 cells/mL (Rodger et al., 2016).

For participants who were on antiretroviral therapy, we asked how many doses were missed in the last 7 days (Simoni et al., 2006). Given the extreme skew in responses missed doses was dichotomized into any missed doses vs. none.

Stimulant Use was assessed by asking whether cocaine, crack, or amphetamines were used in the past month to get high and how often in the past month they were used. Responses were coded as any use vs. none.

Transmission risk sexual behavior

We defined HIV-related transmission risk sex as self-reported condomless insertive or receptive anal or vaginal sex since diagnosis. We identified four categories of transmission sex risk behavior: a) no reported condomless sex, b) condomless sex with only HIV+ individuals (seroconcordant), c) condomless sex with HIV- negative individuals while maintaining undetectable viral load (<200 copies/mL) and d) condomless sex with HIV-negative individuals with detectable viral load (≥200 copies/mL) conceptualized as potentially amplified transmission. We collapsed the three lower risk groups (a, b, and c) and compared to the group engaging in the highest transmission risk behavior (d; detectable viral load and condomless sex with HIV-negative partners).

Feasibility and Acceptability

In addition to enrollment and retention, we assessed feasibility of the intervention by examining the average number of days participants completed their daily home practice during the 5-week intervention. IRISS home practice was composed of the practice of the skills plus daily emotion reporting and Control home practice was daily emotion reporting only. In addition, at the 15-month assessment, we asked questions regarding their personal experience with the intervention and their plans for continued practice of the skills. All participants were asked to rate how helpful they believed the group they were placed in was in helping them cope with their HIV diagnosis, from 0 = Not at all helpful to 10 = Extremely helpful. Participants in the intervention condition were asked to indicate whether they thought they would continue to practice each skill in the future, 0 = No and 1 = Yes.

Analytic Strategy

We determined comparability of the IRISS and control conditions at baseline on demographics, time since diagnosis, and the outcome variables using t-test and chi-square analyses. We then conducted intent-to-treat analyses, using longitudinal growth models to examine patterns of longitudinal change as a function of intervention condition. Longitudinal growth models offer several advantages over traditional repeated measures analytic methods (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA). Unlike traditional methods, longitudinal growth models offer an approach that accommodates missing data points, inconsistent timing in data collection, and non-independence in observations. In this study, we used longitudinal mixed effect models (MIXED; Singer & Willett, 2003) for continuous outcomes and longitudinal generalized estimating equations (GEE) for categorical outcomes (Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988).

Given variability in the actual time that participants completed each assessment, we used time elapsed since the baseline assessment (in months) as our metric of time. We modeled time (grand-mean centered) at Level 1 and intervention condition (effect coded: intervention=0.5, control=-0.5) at Level 2. For each outcome, we tested for both linear and quadratic change over time and present the results for the best-fitting longitudinal change pattern. That is, when the linear growth curve model fit the data best, we removed the quadratic function of time from our analysis and present the outcomes for the linear growth curve model. A quadratic growth curve model fit the data best for the following outcome variables: the impact of events scale (IES), anti-depressant drug use, anti-anxiety drug use, and symptom-severity. Linear growth curve models fit the data best for the remaining outcome variables and are reported as such.

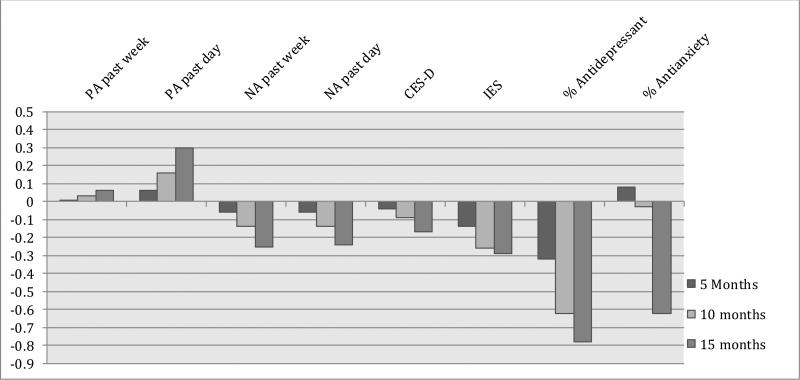

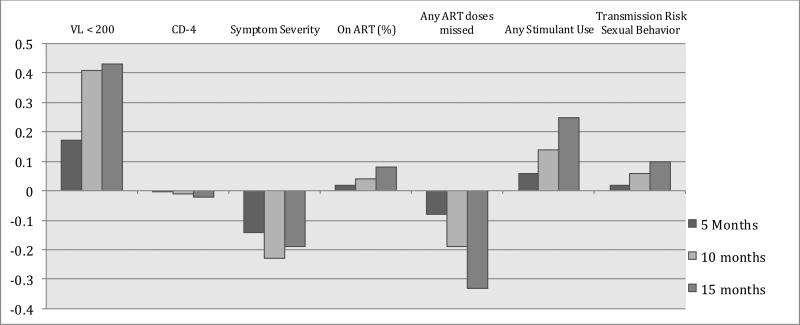

In the results below, we present the between-group differences in the magnitude of change from baseline to the last time point. In Figure 2, we present effect sizes (Cohen's d) for the between-group differences in the magnitude of change from baseline to each post-intervention assessment. For the binary outcome variables, effect sizes were first calculated as odds ratios, and subsequently converted to Cohen's d following the procedures of Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein (2009) for ease of comparison across outcome variables. Based on Bolier and colleagues’ (2013) meta-analysis of positive interventions, we expected small intervention effects that ranged from d = .20 to d = .35. To further visualize the results, in Tables 3 and 4 we note significance of between-group comparisons within each assessment point (baseline, 5 months, 10 months, and 15 months).

Table 3.

Intervention Effects on Psychological Health

| Baseline (n = 159) M (SE) | 5 month (n = 120) M (SE) | 10 month (n = 97) M (SE) | 15 month (n = 114) M (SE) | Overall Effect: Condition × Time Interaction (β11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect (previous week) | |||||

| IRISS | 2.42 (.08) | 2.49 (.07) | 2.58 (.08) | 2.70 (.09) | β11 = 0.01, t(364) = 0.40, p = .69 |

| Control | 2.37 (.08) | 2.43 (.08) | 2.50 (.08) | 2.60 (.09) | |

| Positive Affect (previous day) | |||||

| IRISS | 2.32 (.10) | 2.39 (.09)* | 2.49 (.09)** | 2.62 (.12)** | β11 = 0.02, t(327) = 1.56, p = .12 |

| Control | 2.11 (.10) | 2.12 (.09) | 2.12 (.09) | 2.14 (.12) | |

| Negative Affect (previous week) | |||||

| IRISS | 1.52 (.08) | 1.40 (.07) | 1.25 (.07) | 1.04 (.09) | β11 = −0.01, t(361) = −1.70, p = .09 |

| Control | 1.36 (.08) | 1.30 (.07) | 1.21 (.07) | 1.09 (.09) | |

| Negative Affect (previous day) | |||||

| IRISS | 0.81 (.07) | 0.72 (.07) | 0.61 (.07) | 0.45 (.10) | β11 = −0.01, t(326) = −1.36, p = .17 |

| Control | 0.85 (.07) | 0.81 (.07) | 0.76 (.07) | 0.69 (.09) | |

| Depressive Mood (CES-D) | |||||

| IRISS | 20.05 (1.33) | 18.65 (1.24) | 16.69 (1.26) | 14.07 (1.55) | β11 = −0.14, t(358) = −1.17, p = .24 |

| Control | 18.75 (1.32) | 17.89 (1.24) | 16.68 (1.25) | 15.08 (1.47) | |

| Intrusive and Avoidant Thoughts (IES) | |||||

| IRISS | 26.66 (2.54) | 20.44 (2.38) | 13.83 (2.58) | 8.70 (2.95) | β11 = −0.52, t(325) = −1.98, p = .048; β21 = 0.03, t(366) = −1.99, p = .047 |

| Control | 22.14 (2.52) | 19.11 (2.35) | 15.27 (2.52) | 10.82 (2.81) | |

| Antidepressant use (% yes) | β11 = −0.10, χ2 = 7.48, p = .006 | ||||

| IRISS | 19.3% (4%) | 17.5% (4%) | 15.8% (4%)* | 15% (4%)* | β21 = 0.01, χ2 = −2.14, p = .14 |

| Control | 16.0% (4%) | 22.5% (4%) | 30.7% (6%) | 35% (6%) | |

| Antianxiety medication use (% yes) | β11 = −0.04, χ2 = 1.28, p = .26 | ||||

| IRISS | 18.7% (4%) | 23.1% (5%) | 22.4% (5%) | 11.7% (5%)** | β21 = −0.01, χ2 = 3.23, p = .07 |

| Control | 24.3% (5%) | 26.5% (4%) | 30% (5%) | 36% (6%) | |

Table 4.

Physical Health and Health Behaviors

| Baseline (n = 159) M (SE) | 5 Month (n = 120) M (SE) | 10 Month (n = 97) M (SE) | 15 Month (n = 114) M (SE) | Overall Effect: Condition × Time Interaction (β11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Load < 200 copies/ml | |||||

| IRISS | 14% (4%) | 30% (5%) | 62% (7%) | 91 % (5%) | β11 = 0.09, χ2 = 3.11, p = .08 |

| Control | 18% (4%) | 29% (5%) | 50% (6%) | 76% (7%) | |

| CD-4 | β11 = −0.32, t(162) = −0.14, p = .89 | ||||

| IRISS | 523.11 (31.97) | 547.20 (30.81) | 580.78 (31.40) | 625.78 (35.86) | |

| Control | 508.41 (32.34) | 533.72 (31.31) | 569.02 (31.81) | 616.31 (35.79) | |

| Symptom Severity | β11 = −0.01, t(362) = −1.41, p = .16 β21 = 0.01, t(432) = 2.20, p = .03 |

||||

| IRISS | 2.37 (.07) | 2.30 (.06) | 2.23 (.07) | 2.20 (.09) | |

| Control | 2.30 (.07) | 2.32 (.06) | 2.33 (.07) | 2.27 (.09) | |

| On ART (%) | |||||

| IRISS | 44% (5%) | 56% (5%) | 72% (5%) | 86% (5%) | β11 = 0.01, χ2 = 0.05, p = .83 |

| Control | 46% (5%) | 58% (5%) | 72% (5%) | 86% (6%) | |

| Doses of ART missed (% any missed) | β11 = −0.04, χ2 = 0.87, p = .35 | ||||

| IRISS | 13% (4%) | 13% (3%) | 13% (3%) | 13% (4%) | |

| Control | 14% (4%) | 16% (4%) | 19% (4%) | 23% (5%) | |

| Transmission risk sexual behavior (% highest risk) | β11 = 0.01, χ2 = .29, p = .59 | ||||

| IRISS | 8% (2%) | 9% (2%) | 10% (2%) | 12% (23%) | |

| Control | 11% (3%) | 12% (3%) | 12% (3%) | 14% (25%) | |

| Any stimulant use | |||||

| IRISS | 30% (4%) | 32% (4%) | 36% (5%) | 41% (3%) | β11 = 0.03, χ2 = 1.35, p = .25 |

| Control | 32% (5%) | 32% (5%) | 32% (5%) | 32% (3%) | |

Note: Stars (*) denote between-group differences within each time point at *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001 respectively. The quadratic effect (Condition × Time2: β21) is also reported when the quadratic model provided a better fit.

Mediation analyses

To test whether positive affect mediated effects of the intervention, we conducted multilevel moderated mediation analyses (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006) using a multilevel SEM framework (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010). We conducted separate multilevel moderated mediation models for past day positive and past day negative affect for each of the outcome variables that were significantly different between intervention and control conditions. We tested the significance of the specific indirect effects in the MSEM model using the Monte Carlo method with 20,000 bootstraps (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Selig, 2012).

Sample size, power, and precision

The study was powered based on levels of positive affect in an observational study in people newly diagnosed with HIV (Hult, Maurer, & Moskowitz, 2009; Hult, Wrubel, Bränström, Acree, & Moskowitz, 2012; Moskowitz, Wrubel, Hult, Maurer, & Acree, 2013) in which we had scores on the DES positive scale at 1, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months after diagnosis (N = 49). We averaged the 12- and 18-month data to approximate 15-month scores; and the 6- and 9-month for 5 and 10 months, which gave us an estimate both of the expected change and of the error variance for this particular contrast under the null hypothesis of no intervention effect. For the DES past week positive, the means for these four occasions in the observational study were 2.03, 2.32, 2.37, and 2.37; the gain between baseline and the average of the following three points is .32. We originally aimed to recruit N= 200 into the trial with N = 170 retained. With a two-tailed alpha = .05, and a total N of 170, we would have 80% power against a difference between groups of .15 points on the DES. In other words, if the control group, like the observational study participants, should show an increase of .32 on the DES between baseline and the average of the following three points, there would be an 80% probability that a treatment population increase of .48 points would show up as significant.

RESULTS

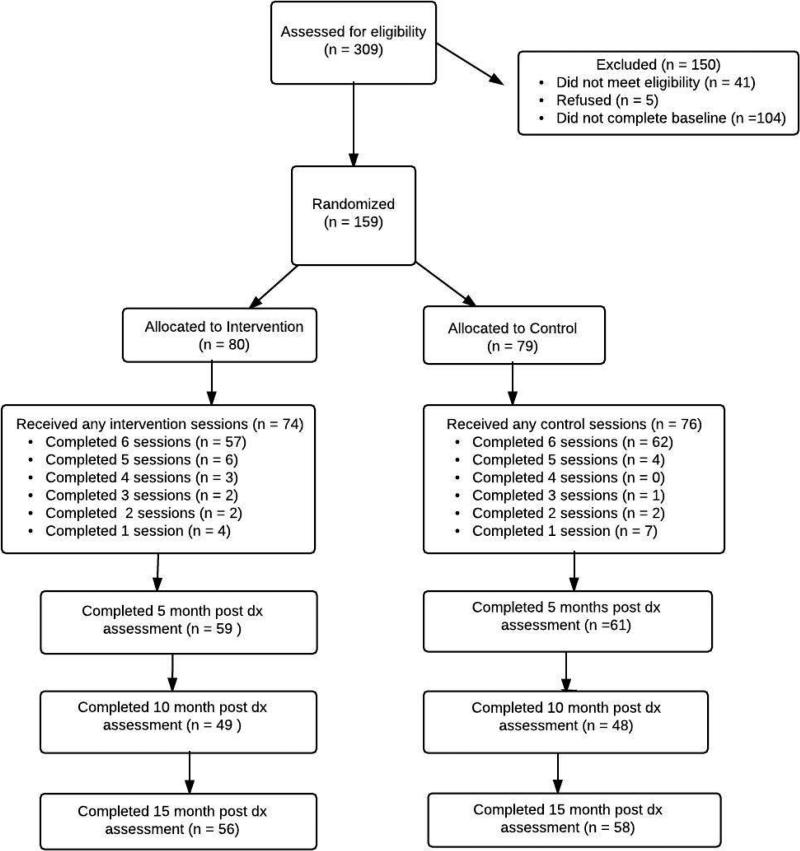

Of 309 potential participants who were screened for the study, 159 were eligible and completed the baseline questionnaire (see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram.) They were then randomized to the intervention (n=80) or the control (n=79) condition. Mean age was 36; the majority of participants were male (91.7%) and identified as gay or bisexual (84.1%). Just over 94% had at least a high school education and 44% self-identified as White (Table 1.) There were no significant differences at baseline on any of the demographic or outcome variables.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Feasibility and Acceptability

One hundred fourteen participants (71.6%) were retained through the 15-month post-diagnosis assessment and retention did not differ by condition (Figure 1). The primary reason for drop out was loss of contact (either participant was non-responsive or phone was disconnected for over two thirds of dropouts in both conditions). Of the 80 participants randomized to the intervention, 92.5% attended at least one session and 77% of these (57 of 74) completed all six. Of the 79 allocated to the control, 96% attended at least one session. Of these, 81.6% (62 of 76) completed all 6 sessions. 60% of participants in the IRISS condition and 69% of participants in the control submitted their daily home practice. Of those who turned in their home practice books, both IRISS and control participants completed approximately 6 out of 7 days per week (MIRISS = 5.98, SDControl = 1.69; MControl = 6.44, SDControl = 1.20). At the 15 month assessment, participants in the IRISS condition rated the intervention to be very helpful in in coping with their HIV diagnosis (M = 7.58, SD = 2.31), indicating high acceptability of the intervention. Control participants also rated participation in their control interviews to be helpful for their coping (M = 5.93, SD = 2.78), though their helpfulness ratings were significantly lower than the IRISS condition, t(107) = −3.37, p = .001. Finally, the large majority of participants in the IRISS condition (96%) indicated that they intended to continue to practice the skills learned from the intervention.

Psychological Health

In Table 3, we present the results for psychological health: positive and negative affect, depressive mood, intrusive and avoidant thoughts, antidepressant use, and anti-anxiety use. Tests of between group differences in change from baseline are the primary analyses. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) for between-group differences in change from baseline to each assessment point are in Figure 2A. Positive effect sizes indicate that the intervention group showed greater increases (or smaller decreases) relative to control from baseline to that assessment point whereas negative effect sizes indicate that the intervention group showed greater decreases (or smaller increases) relative to control. In the Table we also present within-timepoint group comparisons for each assessment point (baseline, 5 months, 10 months, and 15 months) as a secondary set of analyses.

Figure 2A. Effect sizes (d) for between group changes from baseline: Psychological Health.

For binary outcome variables, effect sizes were first calculated as odds ratios and converted to Cohen's d following Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein (2009) for ease of interpretation across outcome variables. PA = Positive affect; NA = Negative Affect; CES-D = the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; IES = Impact of Events Scale

For past week positive affect, there were no significant group differences in the primary analysis of change from baseline or for the secondary within time point group differences. For past-day positive affect, the test for between-group difference in change from baseline did not reach statistical significance (p=.12; Table 3.) The effect size for between-group difference in change from baseline to 15 months was d = .30 (Figure 2A.) For the within-timepoint comparisons, previous day positive affect was significantly higher in the intervention condition compared to the control at the 5, 10, and 15 month assessment points. For negative affect, differences in change over time did not reach statistical significance although the effect size was in the small range (d = −.25 for past-week; d = −.24 for past-day recall) for change from baseline to 15 months (Table 3).

There were no significant differences by intervention group in change in depressive mood (CES-D, p = .24; Table 3) over time. For intrusive and avoidant thoughts (IES), there were significant group differences in change over time (p = .048 linear; p = .047 quadratic; Table 3), and the effect size for between group difference in change from baseline to 5 months was d = −.14; from baseline to 10 months was d = −.26; and from baseline to 15 months d = −.29.

Generalized estimating equations revealed a large and significant effect of the intervention on the likelihood of using anti-depressants (1 = any use, 0 = no use) over time (p = .006; Table 3). The likelihood of antidepressant use in the control condition increased linearly over the course of the study, whereas the likelihood of antidepressant use in the IRISS condition remained relatively stable between 15% and 20%. Effect sizes for between-group differences in change from baseline were d = −.32 at 5 months; d=−.62 at 10 months, and d = −.78 at 15 months. Finally, the difference in change in antianxiety drug use did not reach statistical significance (p = .26 linear; p = .07 quadratic; Table 3). Effect sizes for difference in change from baseline were close to zero at 5 months and 10 months (d= −.08 and d = −.03, respectively) but was medium size at 15 months (d=−.62).

Physical health and health behaviors

Means and results for overall effect of condition by time for physical health and health behaviors appear in Table 4. Effect sizes (d) for between-group difference in change from baseline are graphed in Figure 2B. Generalized estimating equations revealed that there were no between group differences for change over time (p = .08; Table 4) or within assessment point in the likelihood that participants achieved suppressed viral load. The effect sizes for group difference in change over time were in the medium range for change to 10 and 15 months, in favor of the intervention (baseline to 5 months d = .17; baseline to 10 months d = .41; baseline to 15 months d = .43). For CD4, the difference in change over time did no approach statistical significance (p = .89; Table 4) and effect sizes were essentially zero. Linear mixed effects modeling revealed that IRISS participants showed decreases in symptom severity over time whereas control participants showed relatively stable levels of symptom severity over time (p = .16 linear; p = .03 quadratic; Table 4.) Effect sizes for change over time were small, with d = −.14 for difference in change from baseline to 5 months; d = −.23 for baseline to 10 months, and d = −.19 for baseline to 15 months.

Figure 2B. Effect Sizes (d) for between group change from baseline: Physical Health and Health Behaviors.

For binary outcome variables, effect sizes were first calculated as odds ratios and converted to Cohen's d following Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein (2009) for ease of interpretation across outcome variables. VL = viral load; ART = Antiretroviral Therapy

Generalized estimating equations revealed that the intervention did not influence the likelihood of participants being on antiretroviral therapy or the likelihood that participants reported any missed doses of ART (all ps > .35; Table 4). It is notable, however, that the effect sizes for any doses missed were d = −.08 for change from baseline to 5 months; d = −.19 for baseline to 10 months; and d = −.33 for baseline to 15 months; as the intervention group remained stable at 13% reporting any missed doses whereas the control condition increased to 23% reporting a missed dose by 15 months.

Finally, there were no group differences in change over time in the likelihood of participants reporting any stimulant use (p = .25) or the likelihood of reporting transmission risk sexual behavior (p = .59; Table 4).

Mediation

Neither increased positive affect nor decreased negative affect mediated the intervention effects on intrusive and avoidant thoughts or antidepressant use. Specifically, the indirect effects for past day positive affect mediating the effects of the intervention over time were 0.009 95% CI [-0.003, 0.021] for intrusive and avoidant thoughts and 0.001 95% CI [−0.001, 0.003] for antidepressant use, ps > .23. The indirect effects for past day negative affect mediating the effects of the intervention over time were 0.008 95% CI [−0.005, 0.021] for intrusive and avoidant thoughts and −0.002 95% CI [−0.01, 0.006] for antidepressant use, ps > .32.

DISCUSSION

The IRISS study is the first randomized controlled trial of a positive affect skills intervention for people newly diagnosed with a serious illness and, to our knowledge, the only intervention that specifically aims to increase positive affect in people living with HIV. The study was of high methodologic quality in that it met five of the six Cochrane collaboration criteria (Higgins & Green, 2008) for high quality behavioral trials: 1) randomization concealment, 2) baseline comparability of groups, 3) A power analysis and at least 50 participants in the analysis, 4) loss to follow up < 50%, and 5) the use of intent-to-treat analyses. The 6th criteria, blinding of subjects to condition, was not possible once participants started sessions in their assigned condition, although they were blind as to details of the content of the conditions at the time of enrollment and randomization (“learning skills to better manage your mood” vs “talk about what's going on since testing positive”).

Based on Revised Stress and Coping Theory (Folkman, 1997) and the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotion (Fredrickson, 1998), we hypothesized that IRISS would improve psychological health and lead to improved health behaviors and physical health. The IRISS participants had significant reductions in HIV-related intrusive and avoidant thoughts and, whereas control participants increased antidepressant use over time, the IRISS participants reported relatively stable levels of antidepressant use. For positive affect, although the group difference in change from baseline over time did not reach statistical significance, the IRISS participants reported significantly higher levels of past-day positive affect compared to controls, at all three post-intervention assessments. Contrary to hypotheses, changes in positive affect did not mediate the effects of the intervention on intrusive and avoidant thoughts or antidepressant use.

Although the mean past-day positive affect for the IRISS condition was significantly higher than for controls at all follow-up points and the difference in change over time was comparable to average effects found in meta-analysis of positive interventions (Bolier, et al., 2013; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), the group difference in change from baseline over time was not statistically significant (p = .12) and the effect size was small (d = .30). There are several possible explanations for the lack of strong effects on positive affect as it was measured in this trial. By design, the control condition was attention-matched and delivered by the same facilitators who delivered the intervention content. Although this allowed us to differentiate the effects of the positive affect skills themselves from the nonspecific effects such as facilitator characteristics, the attention-matched active comparison made it more difficult to detect an effect of the intervention. In addition, participants were normatively improving on positive affect as they moved away from the date of the diagnosis as evidenced in our observational study (Hult et al., 2009; Hult et al., 2012; Moskowitz et al., 2013). Ideally, future efforts to test the effects of positive affect interventions will have an arm that is assessment only as well as an active control arm to better disentangle normative improvement, nonspecific effects, and the potential active ingredients of the intervention.

Our approach to emotion measurement, in terms of the assessment method and recall period, may have contributed to the small effects on positive affect. Daily recalled positive affect was responsive to the intervention whereas past-week positive affect, using the same emotion terms, was not. Given that the explicit goal of the IRISS intervention was to increase the daily experience of positive emotion and evidence for increased validity with more frequent emotion measurement embedded in participants’ real lives, an approach like ecological momentary assessment (Steptoe & Wardle, 2011), in which participants are asked to report their emotional states multiple times throughout the day may better capture an individual's daily experience of emotion and, potentially, capture the changes in positive emotion that we hypothesized. The Day Reconstruction Method (Kahneman et al., 2004) we used to assess past-day emotion better approximates this momentary emotion measurement than does asking participants to report how they felt over the past week and may explain why we had stronger effects in the past-day vs. the past-week format. As the literature develops and points to more emotion specificity, particularly with respect to which positive emotions may be most responsive to positive emotion interventions, researchers would do well to more carefully select the emotion measures they include to better capture the potential effects.

It may be that changes in positive emotion are not the primary mechanism by which positive interventions affect indicators of psychological and physical health further downstream. Lyubormirsky and Layous (2013) suggest that positive thoughts, positive behaviors, and satisfaction of needs such as autonomy, relatedness, and competence are as important as positive emotions in mediating the beneficial effects of positive psychological interventions. In their meta-analysis of positive interventions, Bolier and colleagues (2013) found that positive interventions had the largest pre-post effect on subjective well-being (the cognitive and/or affective appraisal of one's life as a whole; d=.34), followed by depression (d=.23), and psychological health (includes mastery, hope, and purpose in life; d=.20). Charlson, and colleagues (Charlson et al., 2014; Peterson et al., 2013) report that a positive affect/self-affirmation intervention predicted health behavior change but did not specifically demonstrate whether increases in positive affect mediated the effects. Although we found a small effect of the IRISS intervention on positive affect, increases in positive affect did not appear to consistently mediate any of the intervention effects. In other studies we have currently underway, we are looking at a broader array of positive outcomes, including meaning and purpose, that may better capture the pathways through which interventions like IRISS may impact more distal outcomes.

IRISS included multiple skills that had each shown, either alone or as part of other multi-component interventions, to improve psychological well-being (Moskowitz et al., 2012) and meta-analytic studies indicate that multiple-component interventions are more effective than those that focus on a single skill (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Our approach encouraged participants to learn and try each of the skills, then continue practicing with the ones that they liked the best. Of note, the effects of the intervention appeared to get larger with each subsequent follow-up assessment, a pattern that we saw in our pilot studies as well (Saslow, Cohn, & Moskowitz, 2014). For example, for past-day positive affect the effect sizes at 5, 10, and 15 months post diagnosis were d =.06; d =.16, and d=.30, respectively. For antidepressant use the effect sizes were d = −.32 for change from baseline to 5 months, d = −.62 for 10 months, and d = −.78 for 15 months. This pattern suggests that participants may be incorporating the skills into their lives, and as the practice of the skills becomes more habitual, the benefits are increasing. Anecdotally, it was clear that different participants preferred different positive affect skills and there was no one skill that was a favorite for a majority of participants. The multi-component approach allows more possibility for a good person-activity match and thus, increases the likelihood of the success of the intervention (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013; Schueller, 2012) because participants can select the activities that they like the best, which they are then more likely to practice.

The IRISS content was not specific to people living with HIV. Instead, the focus was on positive affect regulation skills that could be used across types and severity of life stress. On one hand this is a strength in that people living with a serious illness need to cope with a variety of types of stress, not simply things related to their illness, so a more general affect regulation intervention is likely to be more applicable than one targeted only at the stresses of living with HIV. However, tailoring the content somewhat may make it more relevant and interesting to individuals and therefore, increase uptake and adherence. Peterson et al. (2013) note that they tailored their intervention by using vignettes specific to the disease (coronary artery disease, asthma, or post percutaneous coronary intervention), for example.

Furthermore, pairing the intervention with established behavior change programs (e.g., Carrico et al., 2015) or as part of a multi-level intervention (e.g., Higa et al., 2013) would likely increase the impact of the intervention on behavior change. It is increasingly clear that engagement in the full continuum of HIV care – from linkage to care, beginning antiretroviral therapy, to long term adherence, retention in care, and sustained viral suppression—is influenced by psychological well-being (Carrico & Moskowitz, 2014; Wilson et al., 2016). Our data suggest a trend for participants in the IRISS intervention to be more likely to have suppressed viral load (d = .43 for group difference in change from baseline to 15 months), although the effect did not reach statistical significance compared to the control condition. Of note, the San Francisco Department of Public Health (2016) reports that for people newly diagnosed between 2012 and 2014, between 65% and 75% achieved viral suppression within a year after HIV diagnosis. In the present study, the rate of viral suppression in the control condition was 76%, comparable to rates in San Francisco at the time this study was conducted. In contrast, the intervention condition had 91% virally suppressed by 15 months after diagnosis. Although we were underpowered to detect a significant difference in viral suppression, these results suggest that interventions such as IRISS may be a useful addition to programs designed to improve engagement in the full continuum of HIV care (Mugavero, Amico, Horn, & Thompson, 2013).

The IRISS study had several weaknesses. First, retention was lower than we would have liked, with 72% of the sample completing the 15-month assessment. Although not ideal, this retention is comparable to other randomized behavioral trials in people living with HIV (e.g., Carrico et al., 2006; Chesney et al., 2003) and our analytic strategy allowed us to account for missing data. Second, our power analysis was based on observational study of people newly diagnosed with HIV started about five years prior to the IRISS study (Hult et al., 2009; Hult et al., 2012; Moskowitz et al., 2013) and led us to calculate that we would have 80% power to detect a change on the past-week DES positive of .48 (compared to a control increase of .32). However, both the control and IRISS conditions started at a higher level of positive emotion than participants in the observational study and the intervention condition only increased .28 on the DES, significantly short of what we estimated as the effect based on the observational study. It may be that future studies should consider screening participants for anhedonia before enrolling to target those most likely to benefit from the intervention.

A third weakness concerns representativeness of the sample. Participants in IRISS were not representative of people newly diagnosed with HIV in the U.S and, instead, were more reflective of the demographics of people testing positive in the San Francisco Bay area, where the study was conducted. It isn't clear that the findings would differ based on different demographics of the sample, but researchers should keep this caveat in mind if they attempt to implement similar interventions in other cities where the characteristics of people newly diagnosed with HIV differ from the sample reported here.

Fourth, our primary outcome, positive affect, does not have standard benchmarks or norms that we can point to as clinically or practically significant, so it is difficult to judge whether the improvements that we did see are important enough to justify the cost of the intervention on the basis of positive affect alone (Brown & Vanable, 2008). Other outcomes, however, such as antidepressant use do have clinical significance so can be relied on as indicators of the usefulness of the intervention and could be used in future cost effectiveness research with this intervention approach.

Finally, the IRISS intervention was delivered individually and in-person and thus was quite time intensive for both the study team and the participants which lessens the likelihood that it can go to scale in this format. We have begun work on translating the intervention to a self-guided online format (Cohn et al., 2014) that would significantly reduce the cost of the intervention and make it more likely that it could be disseminated to a variety of home and clinic-based settings. Meta-analyses of positive interventions indicate that individual (vs. group) delivery is more effective (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), however, so future work will need to balance these cost, ease of dissemination, and impact considerations.

The study also had a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first test of a positive affect regulation intervention in people newly diagnosed with HIV. The results clearly show that the intervention is acceptable and feasible and holds promise as an efficacious intervention for people in the initial stages of adjustment to a serious chronic illness. The study was high quality in that it met five of the six criteria established by the Cochrane collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2008) including longer term follow-up, baseline comparability of intervention and control conditions, N > 50, completeness of follow-up data, and intention to treat analyses. Overall, the findings of the present study, combined with the growing body of research supporting the efficacy of positive interventions, indicate that such interventions may produce key benefits for individuals faced with chronic illnesses, psychological disorders, or other types of life stress. Future work should explore ways to tailor the intervention content to the individual to potentially increase the strength of the intervention. Furthermore, researchers should consider the possibility of integrating the positive affect skills with other established health behavior interventions to maximize effects on psychological and physical health.

Table 2.

Baseline sample demographics (N=159)

|

Randomization Arm

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | IRISS N=80 | Control N=77 | Total Sample N=159 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.6 (10.2) | 36.5 (9.7) | 36.0 (9.9) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 71 (88.8%) | 73 (94.8%) | 144 (91.7%) |

| Female | 7 (8.8%) | 4 (5.2%) | 11 (7.0%) |

| MTF Transgender | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Gay/bisexual | 63 (78.8%) | 69 (89.6%) | 132 (84.1%) |

| Heterosexual | 13 (16.3%) | 6 (7.8%) | 19 (12.1%) |

| Other | 4 (5.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 6 (3.8%) |

| Education | |||

| Less than High school | 6 (7.5%) | 3 (3.9%) | 9 (5.7%) |

| High school | 45 (56.3%) | 36 (46.8%) | 81 (51.5%) |

| Some college or college grad | 12 (15.0%) | 23 (29.9%) | 35 (22.3%) |

| More than college | 17 (21.3%) | 15 (19.5%) | 32 (20.4%) |

| Yearly Household Income | |||

| <10K | 30 (40.0%) | 16 (21.6%) | 46 (30.9%) |

| 10K-30K | 17 (22.7%) | 19 (25.7%) | 36 (24.2%) |

| 30K-60K | 17 (22.7%) | 17 (23.0%) | 34 (22.8%) |

| 60K-90K | 5 (6.7%) | 8 (10.8%) | 13 (8.7%) |

| >90K | 6 (8.0%) | 14 (18.9%) | 20 (13.4%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 16 (21.6%) | 15 (20.8%) | 31 (21.2%) |

| Latino | 16 (21.6%) | 15 (20.8%) | 31 (21.2%) |

| Latino/Black | 2 (2.7%) | 3 (4.2%) | 5 (3.4%) |

| White | 30 (40.5%) | 35 (48.6%) | 65 (44.5%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 (12.2%) | 3 (4.2%) | 12 (8.2%) |

| American Indian | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (1.4%) |

Public Health Significance.

The Intervention for those Recently Informed of their Seropositive Status (IRISS) is the first randomized controlled trial of a positive affect skills intervention in people newly diagnosed with HIV. The results show that the intervention is acceptable, feasible, and may hold promise as an efficacious intervention for people in the initial stages of adjustment to a serious chronic illness.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study provided by R01 MH084723 and K24 MH093225 to Judith Moskowitz.

Contributor Information

Judith T. Moskowitz, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Adam W. Carrico, University of California San Francisco

Larissa G. Duncan, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Michael A. Cohn, University of California San Francisco

Elaine O. Cheung, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Abigail Batchelder, University of California San Francisco and Massachusetts, General Hospital/Harvard Medical School.

Lizet Martinez, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine.

Eisuke Segawa, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine.

Michael Acree, University of California San Francisco.

Susan Folkman, University of California San Francisco.

REFERENCES

- Antoni MH, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. Cognitive-behavioral stress management for individuals living with HIV. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods. 2006;11(2):142. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP. Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: results from the Steps Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(6):1161–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9778-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Shapiro M. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC public health. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. Converting among effect sizes. Introduction to meta-analysis. 2009:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Boutin-Foster C, Offidani E, Kanna B, Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Scott E, Gerber LM. Results from the Trial Using Motivational Interviewing, Positive Affect, and Self-Affirmation in African Americans with Hypertension (TRIUMPH). Ethnicity & Disease. 2016;26(1):51–60. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Cognitive–behavioral stress management interventions for persons living with HIV: a review and critique of the literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(1):26–40. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9010-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM. Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science. 2003;14:320–327. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein JC, Schultheiss OC, Grassmann R. Personal goals and emotional well-being: The moderating role of motive dispositions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(2):494–508. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB. A four-factor model of perceived control: Avoiding, coping, obtaining, and savoring. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:773–797. [Google Scholar]

- Caponigro JM, Moran EK, Kring AM, Moskowitz JT. Awareness and coping with emotion in schizophrenia: Acceptability, feasibility and case illustrations. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cpp.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Duran RE, Ironson G, Penedo F, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-Positive gay men treated with HAART. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(2):155–164. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Gómez W, Siever MD, Discepola MV, Dilworth SE, Moskowitz JT. Pilot randomized controlled trial of an integrative intervention with methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(7):1861–1867. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect promotes engagement in care after HIV diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2014;33(7):686. doi: 10.1037/hea0000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: A control process view. Psychological Review. 1990;97:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:184–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Wells MT, Peterson JC, Boutin-Foster C, Ogedegbe GO, Mancuso CA, Isen AM. Mediators and moderators of behavior change in patients with chronic cardiopulmonary disease: the impact of positive affect and self-affirmation. Translational behavioral medicine. 2014;4(1):7–17. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0241-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney M, Chambers D, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Pyschosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Folkman S, Chambers D. Coping effectiveness training. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 1996;7(Suppl. 2):75–82. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EO, Cohn MA, Dunn LB, Melisko ME, Morgan S, Penedo FJ, Moskowitz JT. A Randomized Pilot Trial of a Positive Affect Skills Intervention (LILAC) for Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.4312. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70:741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, Hult JR, Moskowitz JT. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2014;9(6):523–534. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.920410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JD, Myers HF, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Mindfulness meditation training effects on CD4+ T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infected adults: A small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2009;23:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, Skarbinski J. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the United States: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling GA, Merrilees J, Mastick J, Chang VY, Hubbard E, Moskowitz JT. Life enhancing activities for family caregivers of people with frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2014;28(2):175–181. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182a6b905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Thanks! how the new science of gratitude can make you happier. Houghton Mifflin; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist. 2000;55(6):647–654. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.647. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychlogy. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni M, Duran RE, Fernandez MI, McPherson-Baker S, Fletcher MA. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23:413–418. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U, Raysz A, Kesper U. Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: Evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2007;76:226–233. doi: 10.1159/000101501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa DH, Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Kay L, Vosburgh HW, Spikes P, Purcell DW. A systematic review to identify challenges of demonstrating efficacy of HIV behavioral interventions for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1231–1244. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0418-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Vol. 5. Wiley Online Library; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Millstein RA, Celano CM, Wexler D. Positive Psychological Interventions for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Rationale, Theoretical Model, and Intervention Development. Journal of diabetes research. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/428349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Boehm JK, Seabrook R, Fricchione GL, Denninger JW, Lyubomirsky S. Development of a positive psychology intervention for patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Heart International. 2011;6(2):e14. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hult JR, Maurer SA, Moskowitz JT. “I'm sorry, you're positive”: a qualitative study of individual experiences of testing positive for HIV. AIDS care. 2009;21(2):185–188. doi: 10.1080/09540120802017602. doi:10.1080/09540120802017602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hult JR, Wrubel J, Bränström R, Acree M, Moskowitz JT. Disclosure and Nondisclosure Among People Newly Diagnosed with HIV: An Analysis from a Stress and Coping Perspective. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(3):181–190. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, Moore J. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Balbin E, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA, O'Cleirigh C, Laurenceau J, Solomon G. Dispositional optimism and the mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2005;12(2):86–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Hayward HS. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70(5):546. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, LaPerriere AR, Antoni MH, O'Hearn P. Changes in immune and psychological measures as a function of anticipation and reaction to news of HIV-1 antibody status. Psychosomatic medicine. 1990;52(3):247–270. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Perry SW, Hirsch D-A. Behavioral and psychological responses to HIV antibody testing. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(1):31–37. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, Rabeneck L, Zackin R, Sinclair G, Wu AW. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54(12 Suppl 1):S77–90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-Based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone AA. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science. 2004;306(5702):1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. doi:10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Julian T. Gratitude and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam war veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:177–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koole SL, Smeets K, van Knippenberg A, Dijksterhuis A. The cessation of rumination through self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Positive life events and depressive symptoms in older adults. Behavioral Medicine. 1998;14(101-112) doi: 10.1080/08964289.1988.9935131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Mannella KA, Hassett AL, Barnett NP, Cranford JA, Brower KJ, Meyer PS. Feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a web-based gratitude exercise among individuals in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10(6):477–488. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston CA. Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1112–1125. [Google Scholar]

- LaPerriere AR, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, Ironson G. Exercise intervention attenuates emotional distress and natural killer cell decrements following notification of positive serologic status for HIV-1. Biofeedback & Self Regulation. 1990;15(3):229–242. doi: 10.1007/BF01011107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent RW, Singley D, Sheu H-B, Gainor KA, Brenner BR, Treistman D, Ades L. Social cognitive predictors of domain and life satisfaction: Exploring the theoretical precursors of subjective well-being. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;52:429–442. [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. Relation of Lifetime Trauma and Depressive Symptoms to Mortality in HIV. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Amenson CS. Some relations between pleasant and unpleasant mood-related events and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87:644–654. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.87.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hoberman HM, Clarke GN. The coping with depression course: Review and future directions. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science. 1989;21:470–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Sullivan M, Grosscup SJ. Changing reinforcing events: An approach to the treatment of depression. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, and practice. 1980;17:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Mo PK, Wu AM, Lau JT. Roles of Self-Stigma, Social Support, and Positive and Negative Affects as Determinants of Depressive Symptoms Among HIV Infected Men who have Sex with Men in China. AIDS and Behavior. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1321-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Floud S, Pirie K, Green J, Peto R, Beral V, Collaborators MWS. Does happiness itself directly affect mortality? The prospective UK Million Women Study. The Lancet. 2016;387(10021):874–881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01087-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Layous K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(1):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon K, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate behavioral research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Wenderoth S, Hollenberg JP, Wells MT, Charlson ME. Increasing physical activity in patients with asthma through positive affect and self-affirmation: A randomized trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1316. archinternmed. 2011.1316 v2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Bingman CR, Duval TS. Negative affect and unsafe sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS & Behavior. 1998;2(2):89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne TJ, Vittinghoff E, Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Coates TJ. Depressive affect and survival among gay and bisexual men infected with HIV. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1996;156(19):2233–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Dempster-McCain D, Williams RM. Successful aging. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;97:1612–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT. Positive Affect Predicts Lower Risk of AIDS Mortality. Psychosomatic medicine. 2003;65(4):620–626. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000073873.74829.23. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000073873.74829.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Carrico AW, Cohn MA, Duncan LG, Bussolari C, Layous K, Folkman S. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention to reduce stress in people newly diagnosed with HIV; protocol and design for the IRISS study. Open Access Journal of Clinical Trials. 2014;6 [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Epel ES, Acree M. Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27(1 Suppl):S73–82. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S73. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Folkman S, Collette L, Vittinghoff E. Coping and mood during AIDS-related caregiving and bereavement. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18(1):49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02903939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Bussolari C, Acree M. What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(1):121–141. doi: 10.1037/a0014210. doi:10.1037/a0014210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Maurer SA, Bussolari C, Acree M. A Positive Affect Intervention for People Experiencing Health-Related Stress: Development and Non-Randomized Pilot Test. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(5):677–693. doi: 10.1177/1359105311425275. doi:10.1177/1359105311425275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]