Abstract

Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) methylation plays an important role in the carcinogenesis of breast cancer (BC). However, the association between RUNX3 hypermethylation and significance of BC remains under investigation. The purpose of this study is to perform a meta-analysis and literature review to evaluate the clinicopathological significance of RUNX3 hypermethylation in BC. A comprehensive literature search was performed in Medline, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Library Database, CNKI and Google scholar. A total of 10 studies and 747 patients were included for the meta-analysis. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) were evaluated and summarized respectively. RUNX3 hypermethylation was significantly correlated with the risk of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), OR was 50.37, p < 0.00001 and 22.66, p < 0.00001 respectively. Interestingly, the frequency of RUNX3 hypermethylation increased in estrogen receptor (ER) positive BC, OR was 12.12, p = 0.005. High RUNX3 mRNA expression was strongly associated with better relapse-free survival (RFS) in BC patients. In summary, RUNX3 methylation could be a promising early biomarker for the diagnosis of BC. High RUNX3 mRNA expression is correlated to better RFS in BC patients. RUNX3 could be a potential therapeutic target for the development of personalized therapy.

Keywords: RUNX3, methylation, odds ratio, prognosis, drug target

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cancer related death for women worldwide, with 232,340 new cases every year [1]. Carcinogenesis in breast is a linear multi-step process which starts as flat epithelial atypia (FEA), progresses to atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), advances to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). The most common cause of death in BC is invasive malignancy. Therefore, it is critical to identify an early detection biomarker to predict the progression of BC [2].

The studies of molecular mechanism have demonstrated that the carcinogenesis involves the accumulation of various genetic alterations including loss of tumor suppressor genes and amplification of oncogenes [3]. RUNX (Runt-related transcription factor) family of genes including RUNX1, RUNX2 and RUNX3, encode transcription factors which bind DNA by partnering with the cofactor, CBFβ/PEBP2β (core-binding factor-beta subunit/polyomavirus enhancer-binding protein 2 beta subunit). The complex regulates the growth, survival and differentiation via a few essential transcription factors [4]. RUNX3 plays an important role in gastric epithelial growth [5], development of dorsal root ganglia [6–7] and T-cell differentiation [8], and has a principle role in the regulation of cell proliferation, cell death, angiogenesis, as well as invasion [9–10]. RUNX3 was first reported as a tumor suppressor in gastric cancer because of the causal link between the loss of RUNX3 and gastric carcinogenesis [5]. Since then, RUNX3 has been observed as a suppressor that is inactivated in a variety of pre-invasive and invasive tumor including BC [11]. RUNX3 protein regulates the growth-suppressive effects of transforming growth factor-β (TGF- β) by associating with SMAD, a downstream protein in the signaling pathway [12]. Recently, RUNX3 has been reported to attenuate Wnt signaling by directly suppressing β-catenin/TCF4 in colon cancer and gastric cancer [13]. Previous evidences in cell lines, knockout animals, and primary human cancer tissues have indicated that RUNX3 as a suppressor is inactivated in BC by reduced copy number [14], protein mislocalization [10, 15], hemizygous deletion and promoter hypermethylation [16–18]. However, the role of RUNX3 as a tumor suppressor in the progression and prognosis of BC remains unclear due to the small sample size of individual studies. We conducted a meta-analysis which increases the sample size and thus the power, to investigate the significance of RUNX3 hypermethylation in the progression and prognosis of BC.

RESULTS

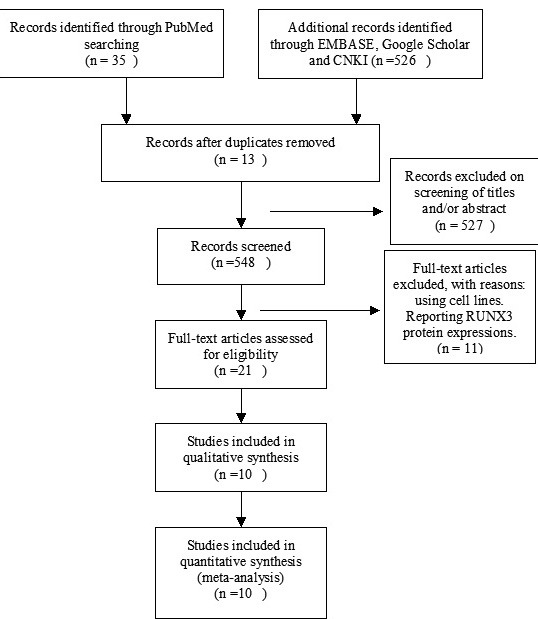

10 studies were included after screening 862 studies by two authors (Figure 1). The following variables were listed: first author, published year, country, ER status, RUNX3 methylation status and patient progressions (Table 1).

Figure 1. Schematic flow diagram for selection of included studies.

Table 1. Main characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Normal | Benign | DCIS | IDC | Methylation-site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation | Ex-pression | Methylation | Expression | Methylation | Expression | Methylation | Expression | ER Status (-/+) |

Methods | ||||

| Park[38] | 2011 | Korea | 0/30 | 0/30 | 17/35 | 24/50 | 17/68 | Methy light |

Promoter CpG islands |

||||

| Subramaniam[39] | 2010 | Singapore | 1/30 | 28/30 | 0/20 | 99/101 | 15/20 | 3/20 | 16/20 | 2/20 | N/A | MSP IHC |

Promoter CpG islands |

| Subramaniam [10] | 2009 | Singapore | 1/10 | 9/10 | 13/17 | 3/17 | 16/21 | 2/23 | N/A | MSP IHC |

Promoter CpG islands |

||

| Lau[15] | 2006 | Singapore | 0/20 | 20/20 | 23/44 | 0/44 | N/A | MSP IHC |

Promoter CpG islands |

||||

| Du[40] | 2010 | China | 0/15 | 19/40 | N/A | MSP | Promoter CpG islands |

||||||

| Suzuki[11] | 2005 | Japan | 11/22 | MSP | Promoter CpG islands |

||||||||

| Li[41] | 2013 | China | 1/12 | 25/48 | N/A | MSP | Promoter CpG islands |

||||||

| Qiao[42] | 2012 | China | 4/60 | 35/60 | N/A | MSP | Promoter CpG islands |

||||||

| Tian[43] | 2010 | China | 6/56 | 31/56 | N/A | MSP | Promoter CpG islands |

||||||

| Jiang[16] | 2008 | China | 0/15 | 15/15 | 13/15 | 0/15 | 48/40 | MSP IHC |

Promoter CpG islands |

||||

MSP: Methylation-Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction

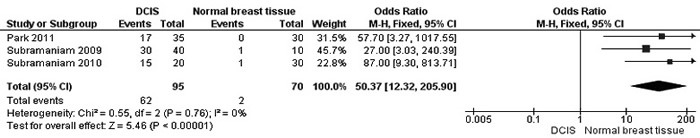

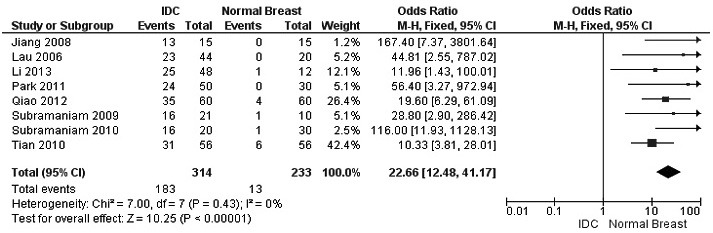

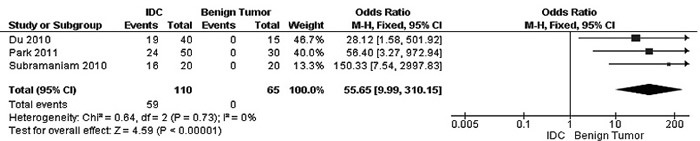

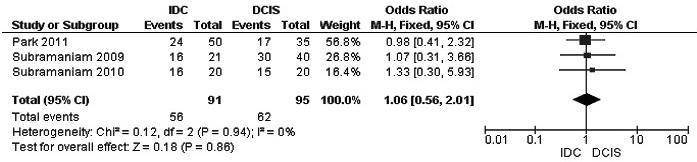

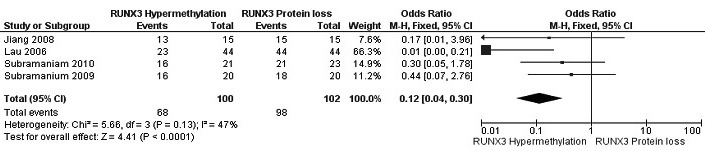

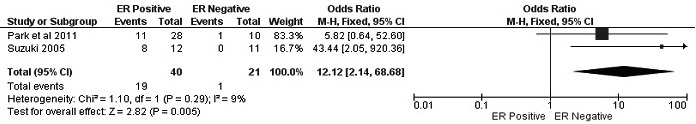

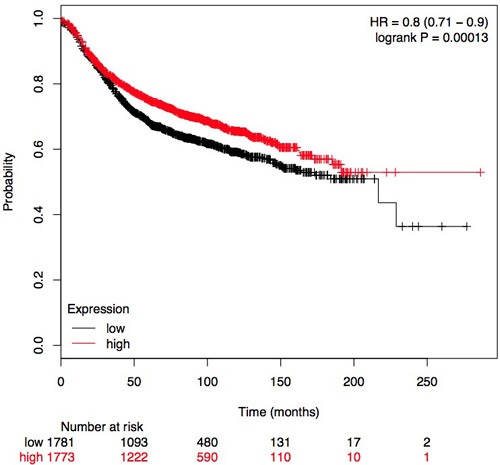

The frequency of RUNX3 methylation was significantly higher in DCIS than in normal breast tissues and the pooled OR was 50.37 with 95% CI 12.32-205.90, z = 5.46, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, p = 0.76 (Figure 2). RUNX3 promoter in IDC patients was significantly methylated than in normal breast, OR was 22.66 with 95% CI 12.48-41.17, z = 10.25, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, p = 0.43 (Figure 3). In addition, RUNX3 methylation was significantly increased in IDC than in benign tumor, OR was 55.65 with 95% CI 9.99-310.15, z = 4.59, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, p = 0.73 (Figure 4). RUNX3 methylation was not significantly increased in IDC than DCIS, OR was 1.06 with 95% CI 0.56-2.01, z = 0.18, p = 0.86, I2 = 0%, p = 0.94 (Figure 5). RUNX3 methylation was strongly correlated to RUNX3 loss, OR was 0.12 with 95% CI 0.04-0.30, z = 4.41, p < 0.0001, I2 = 47% (Figure 6). In addition, the frequency of RUNX3 methylation was higher in ER positive patients with BC than in ER negative patients with BC (Figure 7). The OR was 12.12 with 95% CI 2.14-68.68, z = 2.82, p = 0.005, I2 = 9%, p = 0.29. High RUNX3 mRNA expression was strongly correlated to better relapse-free survival (RFS) in all 3554 BC patients (Figure 8).

Figure 2. Forest plot for RUNX3 methylation in DCIS and normal breast tissue.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval, DCIS: Ductal Carcinoma In Situ.

Figure 3. Forest plot for RUNX3 methylation in IDC and normal breast tissue.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval, IDC: Invasive Ductal Carcinoma.

Figure 4. Forest plot for RUNX3 methylation in IDC and benign tumor.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval, IDC: Invasive Ductal Carcinoma.

Figure 5. Forest plot for RUNX3 methylation in IDC and DCIS.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval, DCIS: Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, IDC: Invasive Ductal Carcinoma.

Figure 6. Forest plot for the correlation of RUNX3 hypermethylation and RUNX3 loss in IDC tumor.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval.

Figure 7. Forest plot for RUNX3 methylation in ER positive and negative of BC.

The squares represent the weight of individual study in the meta-analysis, the line width indicates the corresponding 95% CI, The diamond represents the pooled OR, and the width of diamond indicates 95% CI. Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, CI: Confidence Interval, ER: Estrogen Receptor.

Figure 8. Plot for the relationship of RUNX3 mRNA expression and RFS in BC patients.

HR: Hazard Ratio

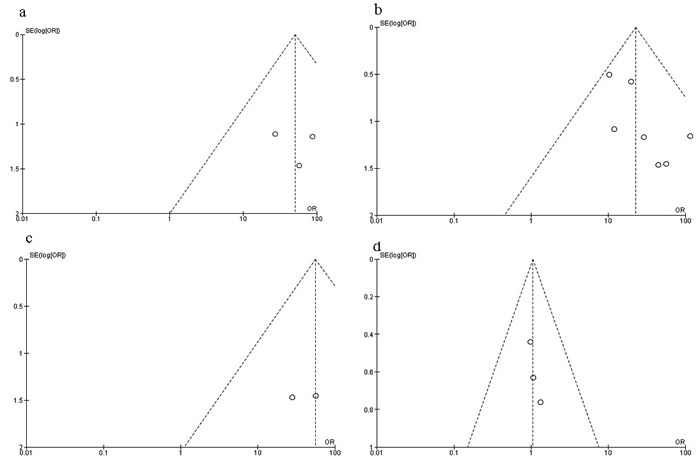

The quality of each study was evaluated using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS). Non-randomized case controlled studies and cohort studies was assigned up to nine points in three domains, 1) selection of study groups, 2) comparability, 3) exposure, and outcomes for study participants. Among studies, five graded 8 points and five graded 7 points. Those studies were of a relatively high quality (Table 2). A sensitivity analysis, in which one study was omitted at a time, was performed to assess the result stability. The pooled ORs were not affected, indicating the stability of present analyses. The symmetry of funnel charts (Figure 9) suggested that there were no publication biases in the meta-analysis of RUNX3 methylation in BC.

Table 2. Quality assessment according to the Newcastle–Ottawa scale of the included studies.

Figure 9. Funnel plot for publication bias.

a. RUNX3 methylation in DCIS and normal breast tissue; b. RUNX3 methylation in IDC and normal breast tissue; c. RUNX3 methylation in IDC and benign tumor; d. RUNX3 methylation in IDC and DCIS. Y-axis represents the standard error, X-axis represents order ratio, Area of the circle represents the weight of individual study.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have reported the contribution of RUNX3 hypermethylation in BC progression by utilizing small group of patients. To overcome small sizes of individual studies, we conducted the powerful meta-analysis with a total of ten studies and 747 patients, and evaluated the role of RUNX3 hypermethylation in the carcinogenic progression of BC. The pooled OR of RUNX3 methylation in DCIS and NB or benign tumor under the fixed-effects model was 50.37 which indicated the frequency of RUNX3 hypermethylation in DCIS significantly increased compare to NB or benign tumor, the heterogeneity did not show significant difference among studies at Cochran's test, with low I2 index (0%), suggesting RUNX3 methylation is an early event during carcinogenesis which is consistent with the results of the original articles included in present study. Similarly, the hypermethylation rate of RUNX3 in IDC was also significantly higher than in NB or benign tumor. Our results are consistent with previous studies [19]. The RUNX3 gene resides on human chromosome 1p36, a region that genomic deletion frequently happened in various human cancers, including BC [20]. The RUNX3 transcription factor is a downstream effector of TGF-β signaling pathway. TGF-β is activated after binding to Smad 4 (co-Smad) and enter the nucleus. RUNX3 binds R-Smads, co-Smads and p300, a transcriptional co-activator, and fulfills its tumor suppressor activity via TGF-β signaling pathway [12]. Xie et al has observed the downstream SMAD pathway stays active in majority of BC cells [21]. The sensitivity to TGF- β was re-established in RUNX3-deficient cancer cells after reintroducing RUNX3 into those cells which showed increased expression of proapoptotic gene BIM [22]. In addition, the status of EGFR, p53 or KRAS in RUNX3 hypermethylation in BC was unavailable, weather RUNX3 silencing contributes to the development of BC concomitantly or independently, further investigations are needed. Previous evidences indicate RUNX family genes regulate cell fate through p53-dependent DNA damage response and/or tumorigenesis [23–24]. Additionally, Omar et al reported that aberrant expression of RUNX3 was not biased toward the EGFR or KRAS mutation pathway in lung adenocarcinoma (ADC), indicating that RUNX3 methylation contributes the development of ADC in an independent of EGFR or KRAS pathway [25].

Recent evidences indicate that RUNX3 hypermethylation attributes to the development of BC through Wnt signaling pathway. Wnt signaling pathway is not only critical for the development of the mammary gland, but also is important for regulating cell proliferation and survival. RUNX3 interacts with β-catenin/TCFs and forms a complex which inhibits the transactivation via blocking β-catenin/TCFs DNA binding [26]. Ito et al has observed that RUNX3 down-regulates Wnt signaling by directly inhibiting β-catenin/TCFs in colon cancer and gastric cancer [13]. The activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was observed following knockdown of the tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in human breast cells [27]. Furthermore, the downregulation of the Wnt inhibitor Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein1 (Sfrp1) was observed in most invasive human BC [28]. Taken together, RUNX3 as a suppressor plays critical role in the development and progression of BC via Wnt signaling pathway [29–30]. Therefore, high RUNX3 mRNA expression is associated with better relapse-free survival (RFS) in BC patients (Figure 8).

Kang et al reported 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR), a demethylation agent restored the expression of RUNX3, induced apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation in the breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. [31] In addition, miR-29 family members (which downregulated the DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B in non-small cell lung cancer [32]) could decrease promoter methylation and increase expression of RUNX3, as a result, those agents potentially suppress tumor proliferation and induced apoptosis. Although more investigation needs to complete, RUNX3 could be a potential therapeutic target for the development of personalized treatment via demethylation.

In addition, we found that RUNX3 promoter methylation was not significantly increased in DCIS compared to IDC. This data indicated that RUNX3 hypermethylation may not be required during the progression from DCIS to IDC. Although there was not heterogeneity existed between included studies, further studies with higher power are needed to confirm this point. RUNX3 methylation could also be detected in the sera of patient with BC [33]. More extended studies are needed to investigate the potential value of RUNX3 as a diagnostic marker for BC in future.

We pooled four studies and evaluated the association between RUNX3 methylation and RUNX3 loss, the result showed that OR was 0.12, p < 0.0001, I2 = 47%. There was moderate evidence for heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 47%, p = 0.13), mostly accounted for by Lau et al which reported lower rate of RUNX3 methylation (52%) compared to other three studies (the rate of RUNX3 methylation arranged from 76% to 86%). Removal this study from meta-analysis reduced the I2 statistic to 0%, OR was changed to 0.32 with 95% CI 0.10-1.03, p = 0.06, close to significantly different. Our finding indicated that RUNX3 methylation was correlated with RUNX3 loss, but more studies with a large population need to be completed.

Two studies have shown RUNX3 methylation was higher in ER positive BC patients than in ER negative BC patients. ER signaling plays an important role in the development of mammary gland through the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis [34]. Abnormal ER signaling contributes to initiation and progression of BC [35]. Recent evidence showed that RUNX3 inhibits ER signaling through suppressing the transcription activity of ERα and reducing ERα-dependent cancer cell proliferation. Therefore, RUNX3 mRNA high expression was correlated to better overall survival in ER-negative patients, but not in ER-positive patients [19]. Aberrant RUNX3 expression contribute to the development and progression of BC through modulating ER signaling pathway. Overexpression of RUNX3 in BC cells decreases ERα expression, whereas deletion of RUNX3 by siRNA increases ER expression. Expression of RUNX3 is inversely associated with ERα in breast cells lines and human BC tissue [36]. Further investigation with a large population needs to be carried out to confirm this mechanism.

There are some limitations in this meta-analysis. Present results were based on individual unadjusted ORs, while further investigation should be adjusted by other potential risk factors. In addition, most selected studies are from Asia population, thus, the findings of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. All the included studies are observational studies which are well known selection bias and publication bias, as positive results may be more likely to be published than negative results. We only selected relevant studies in English and Chinese, some eligible studies in other languages may be excluded, indicating language bias probably introduced.

In summary, the results of present meta-analysis suggest that the frequency of RUNX3 hypermethylation significantly increased in DCIS and IDC. RUNX3 methylation could be a promising biomarker for early diagnosis of BC. High RUNX3 mRNA expression is correlated to better relapse-free survival (RFS) in all BC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

The following electronic databases were reviewed without any language restrictions: PubMed (1966 ∼ 2016), Web of Science (1945 ∼ 2016), EMBASE (1980 ∼ 2016), Cochrane Library Database (1972-2016), CNKI and Google scholar. The following key words were used: “RUNX3 methylation” and “breast cancer”. There were 35 studies identified from PubMed, 56 studies from Web Science, 39 studies from Embase, 432 studies from CNKI. First 300 of 2700 articles were screened from google scholar.

The following were criteria for the inclusion: 1) The studies about RUNX3 methylation and the clinicopathological significance in BC; 2) RUNX3 methylation in prognosis of patients with BC. 21 relevant studies were included for full text review. Among of them, 11 studies were excluded for evaluating RUNX3 protein expression, or using the same population, conference abstracts containing insufficient data, and using cell lines. The variables from 10 related studies were listed in Table 1.

Data extraction and study assessment

Two authors (DL and YM) performed independent systematic reviews and collected data by using a standardized data extraction form including the following variables: first author's name, year of publication, countries, number of patients, study population, ER status, stage of BC, grade of BC, and RUNX3 methylation rate, RUNX3 expression. Any discrepancies were discussed and reached a consensus for all issues.

Statistics analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated by using a fixed or random effect model. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by using the Cochran Chi-square test and qualified by I2 statistics. When the heterogeneity I2 < 50%, a fixed effect model was used, otherwise. When I2 >50%, indicated substantial heterogeneity among studies, a random effect model was adopted. Potential sources of heterogeneity were then investigated using subgroup analysis and meta-regression. The analysis was conducted to compare RUNX3 methylation between DCIS and normal tissue, IDC and normal tissue, IDC and DCIS, RUNX3 methylation in ER positive and native patients. Two-sided statistical tests and p-value were used. Relapse-free survival was analyzed by using an online database Kaplan Meier-plotter (cancer survival analysis) (http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=breast). The database was established by using gene expression and the survival information of 3554 BC patients [37]. Publication bias were evaluated by the funnel graphs. An asymmetric funnel plot in meta-analysis suggests the existence of publication bias. All analysis was conducted with Review Manager 5.2.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES

Acknowledgments

There is no funding that supported this work.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

DL and YM contributed substantially to the study and design, collection of data, and analysis of data. DL, AZ and YH contributed substantially to the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and performed the statistical analysis. DL and YH have been involved in the drafting and revision of the article. The corresponding author had full access to all data and the final responsibility for the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dua RS, Isacke CM, Gui GP. The intraductal approach to breast cancer biomarker discovery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1209–1216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckmann MW, Niederacher D, Schnurch HG, Gusterson BA, Bender HG. Multistep carcinogenesis of breast cancer and tumour heterogeneity. J Mol Med (Berl) 1997;75:429–439. doi: 10.1007/s001090050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Gergen JP, Groner Y, Hiebert SW, Ito Y, Liu P, Neil JC, Ohki M, Speck N. Nomenclature for Runt-related (RUNX) proteins. Oncogene. 2004;23:4209–4210. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li QL, Ito K, Sakakura C, Fukamachi H, Inoue K, Chi XZ, Lee KY, Nomura S, Lee CW, Han SB, Kim HM, Kim WJ, Yamamoto H, et al. Causal relationship between the loss of RUNX3 expression and gastric cancer. Cell. 2002;109:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue K, Ozaki S, Shiga T, Ito K, Masuda T, Okado N, Iseda T, Kawaguchi S, Ogawa M, Bae SC, Yamashita N, Itohara S, Kudo N, Ito Y. Runx3 controls the axonal projection of proprioceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:946–954. doi: 10.1038/nn925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levanon D, Bettoun D, Harris-Cerruti C, Woolf E, Negreanu V, Eilam R, Bernstein Y, Goldenberg D, Xiao C, Fliegauf M, Kremer E, Otto F, Brenner O, et al. The Runx3 transcription factor regulates development and survival of TrkC dorsal root ganglia neurons. EMBO J. 2002;21:3454–3463. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniuchi I, Osato M, Egawa T, Sunshine MJ, Bae SC, Komori T, Ito Y, Littman DR. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 2002;111:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund AH, van Lohuizen M. RUNX: a trilogy of cancer genes. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:213–215. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramaniam MM, Chan JY, Soong R, Ito K, Ito Y, Yeoh KG, Salto-Tellez M, Putti TC. RUNX3 inactivation by frequent promoter hypermethylation and protein mislocalization constitute an early event in breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9917-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M, Shigematsu H, Shames DS, Sunaga N, Takahashi T, Shivapurkar N, Iizasa T, Frenkel EP, Minna JD, Fujisawa T, Gazdar AF. DNA methylation-associated inactivation of TGFbeta-related genes DRM/Gremlin, RUNX3, and HPP1 in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1029–1037. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Ito Y, Miyazono K. RUNX transcription factors as key targets of TGF-beta superfamily signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito K. RUNX3 in oncogenic and anti-oncogenic signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1243–1249. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, Salto-Tellez M, Palanisamy N, Ganesan K, Hou Q, Tan LK, Sii LH, Ito K, Tan B, Wu J, Tay A, Tan KC, Ang E, et al. Targets of genome copy number reduction in primary breast cancers identified by integrative genomics. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:288–301. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau QC, Raja E, Salto-Tellez M, Liu Q, Ito K, Inoue M, Putti TC, Loh M, Ko TK, Huang C, Bhalla KN, Zhu T, Ito Y, et al. RUNX3 is frequently inactivated by dual mechanisms of protein mislocalization and promoter hypermethylation in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6512–6520. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, Tong D, Lou G, Zhang Y, Geng J. Expression of RUNX3 gene, methylation status and clinicopathological significance in breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines. Pathobiology. 2008;75:244–251. doi: 10.1159/000132385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang KT, Han W, Bae JY, Hwang SE, Shin HJ, Lee JE, Kim SW, Min HJ, Noh DY. Downregulation of the RUNX3 gene by promoter hypermethylation and hemizygous deletion in breast cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(Suppl):S24–31. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamalakaran S, Varadan V, Giercksky Russnes HE, Levy D, Kendall J, Janevski A, Riggs M, Banerjee N, Synnestvedt M, Schlichting E, Karesen R, Shama Prasada K, Rotti H, et al. DNA methylation patterns in luminal breast cancers differ from non-luminal subtypes and can identify relapse risk independent of other clinical variables. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu YY, Chen C, Kong FF, Zhang W. Clinicopathological significance and potential drug target of RUNX3 in breast cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2423–2430. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S71815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weith A, Brodeur GM, Bruns GA, Matise TC, Mischke D, Nizetic D, Seldin MF, van Roy N, Vance J. Report of the second international workshop on human chromosome 1 mapping 1995. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;72:114–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie W, Mertens JC, Reiss DJ, Rimm DL, Camp RL, Haffty BG, Reiss M. Alterations of Smad signaling in human breast carcinoma are associated with poor outcome: a tissue microarray study. Cancer Res. 2002;62:497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yano T, Ito K, Fukamachi H, Chi XZ, Wee HJ, Inoue K, Ida H, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Bae SC, Ito Y. The RUNX3 tumor suppressor upregulates Bim in gastric epithelial cells undergoing transforming growth factor beta-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4474–4488. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01926-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blyth K, Cameron ER, Neil JC. The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:376–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozaki T, Nakagawara A, Nagase H. RUNX Family Participates in the Regulation of p53-Dependent DNA Damage Response. Int J Genomics. 2013;2013:271347. doi: 10.1155/2013/271347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omar MF, Ito K, Nga ME, Soo R, Peh BK, Ismail TM, Thakkar B, Soong R, Ito Y, Salto-Tellez M. RUNX3 downregulation in human lung adenocarcinoma is independent of p53, EGFR or KRAS status. Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito K, Lim AC, Salto-Tellez M, Motoda L, Osato M, Chuang LS, Lee CW, Voon DC, Koo JK, Wang H, Fukamachi H, Ito Y. RUNX3 attenuates beta-catenin/T cell factors in intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Brown M, Dutcher J, Clouthier SG, Wicha MS. Regulation of mammary stem/progenitor cells by PTEN/Akt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roarty K, Rosen JM. Wnt and mammary stem cells: hormones cannot fly wingless. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai J, Yong HM, Chen FF, Song WB, Li C, Liu H, Zheng JN. RUNX3 is a prognostic marker and potential therapeutic target in human breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1813–1823. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boone BA, Sabbaghian S, Zenati M, Marsh JW, Moser AJ, Zureikat AH, Singhi AD, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Krasinskas AM. Loss of SMAD4 staining in pre-operative cell blocks is associated with distant metastases following pancreaticoduodenectomy with venous resection for pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:171–175. doi: 10.1002/jso.23606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang HF, Dai ZJ, Bai HP, Lu WF, Ma XB, Bao X, S Lin, Wang XJ. RUNX3 gene promoter demethylation by 5-Aza-CdR induces apoptosis in breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:411–417. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S43744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan M, Wu J, Cai Y. Suppression of Wnt signaling by the miR-29 family is mediated by demethylation of WIF-1 in non-small-cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438:673–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan SH, Ida H, Lau QC, Goh BC, Chieng WS, Loh M, Ito Y. Detection of promoter hypermethylation in serum samples of cancer patients by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction for tumour suppressor genes including RUNX3. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:1225–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: Estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta: regulation by selective estrogen receptor modulators and importance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:335–344. doi: 10.1186/bcr78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheskis BJ, Greger JG, Nagpal S, Freedman LP. Signaling by estrogens. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:610–617. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang B, Qu Z, Ong CW, Tsang YH, Xiao G, Shapiro D, Salto-Tellez M, Ito K, Ito Y, Chen LF. RUNX3 acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by targeting estrogen receptor alpha. Oncogene. 2012;31:527–534. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, Szallasi Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park SY, Kwon HJ, Lee HE, Ryu HS, Kim SW, Kim JH, Kim IA, Jung N, Cho NY, Kang GH. Promoter CpG island hypermethylation during breast cancer progression. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-1013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramaniam MM, Chan JY, Omar MF, Ito K, Ito Y, Yeoh KG, Salto-Tellez M, Putti TC. Lack of RUNX3 inactivation in columnar cell lesions of breast. Histopathology. 2010;57:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin-rong LG Du, Jiang Ying. Relationship between the methylation of RUNX3 promoter and the clinical pathological characters and prognostic factors of breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Journal of Harbin Medical University. 2008;1:019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Dongxia WH, Gao Jianzhi, Fang Zhixin. Relationship between methylation status of Runx3 gene promoter and Runx3 protein expression in patients with breast cancer. China Maternal and Child Health. 2013;22:038. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiao Li YZ, Liu Wei. Clinical Significance of Detecting Plasma Runx3 Gene Promotor Methylation in Early Diagnosis Breast Cancer. Modern Laboratory Medicine. 2012;27:35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian Shengwang JS, Chen Jian. Analysis of the status of Runx3 gene promoter methylation in breast cancer and its relationship with pathological features. Chinese Journal of Breast Disease. 2010;4:50–53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.