Abstract

Indigenous populations experience dramatic health disparities; yet, few medical schools equip students with the skills to address these inequities. At the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus, a project to develop an Indigenous health curriculum began in September 2013. This project used collaborative and decolonizing methods to gather ideas and opinions from multiple stakeholders, including students, community members, faculty, and administration, to guide the process of adding Indigenous health content to the curriculum to prepare students to work effectively with Indigenous populations. A mixed-methods needs assessment was implemented to inform the instructional design of the curriculum. In June 2014, stakeholders were invited to attend a retreat and complete a survey to understand their opinions of what should be included in the curriculum and in what way. Retreat feedback and survey responses indicated that the most important topics to include were cultural humility, Indigenous culture, social/political/economic determinants of health, and successful tribal health interventions. Stakeholders also emphasized that this content should be taught by tribal members, medical school faculty, and faculty in complementary departments (e.g., American Indian Studies, Education, Social Work) in a way that incorporates experiential learning.

Preliminary outcomes include the addition of a seven-hour block of Indigenous content for first-year students taught primarily by Indigenous faculty from several departments. To address the systemic barriers to health and well-being and provider bias that Indigenous patients experience, this project sought to gather data and opinions regarding the training of medical students through a process of Indigenizing research and education.

Of all racial minorities, Indigenous* populations have the most dramatic health inequities in the United States, including significantly higher rates of cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, suicide, and substance abuse.1–3 Compared with white populations, Indigenous populations have fewer educational opportunities, higher rates of unemployment and incarceration, and increased exposure to environmental risks, all of which are known contributors to health inequities.3,4 Within the health care system, Indigenous populations are more likely to be underinsured and to have reduced access to family medicine providers as well as to specialty care.5,6 Further, Indigenous individuals encounter challenges during medical visits that include bias, microaggressions, provider turnover, and a lack of understanding of Indigenous health beliefs.7–9 Historical and contemporary events related to policies of assimilation and genocide, broken treaties, and medical racism have resulted in increased distrust of Western medicine and research by tribal members.10 Given the breadth of health inequity for Indigenous people, we anticipate that health care providers would benefit from learning how to effectively work with Indigenous patients and communities.

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education mandates the inclusion of teaching related to transparent cultural competencies in U.S. medical schools.11 These competencies include increasing awareness of gender and cultural bias and the development of skills to effectively provide treatment to people across cultures. As a result, medical school curricula are evolving to reflect these requirements, and licensure exams have been updated to include questions about health disparities and social justice.12,13 Medical students have reported that they believe that multiculturalism, bias, and racism should be a part of their curriculum.14 Students from underrepresented minority groups express that the presence of a health disparities course positively influenced their decision to attend a particular medical school.15 However, a curriculum tailored to the medical school’s local and regional minority population may be even more effective than a general course in multiculturalism. In particular, Indigenous groups are not homogenous, so there is a need for medical schools to have a specific curriculum related to the local and regional groups that trainees will serve.15 However, it is important to note that the Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education Network, a network of medical educators from Australia and New Zealand, has emphasized the importance of teaching Indigenous cultural safety/awareness separately from multicultural awareness.16,17

The University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus (UMMSD) is situated in a region that serves a significant Indigenous population, so it is critical for the school to offer meaningful Indigenous health content and threads throughout the curriculum. Incorporating feedback from Indigenous community members into the development of this curriculum is also critical. Therefore, we initiated a community-building and knowledge-gathering project to develop an Indigenous health curriculum for medical students to address Indigenous health disparities in our local tribal areas. The purpose of this project was to create didactic material for medical students to increase their knowledge and competency in the area of Indigenous health. In this article, we describe this project, including the guiding principles supporting this work as well as the first steps in this process of creating an Indigenous health curriculum for medical students.

Minnesota Health and Medical School Context

Indigenous people represent 1.3% of the total Minnesota population and are the largest minority group in some rural regions of the state.18 There are seven Anishinaabe and four Dakota reservations, which were created by treaties on land that was, in part, their original homelands. In 2014, Minnesota was ranked number 4 in the nation for overall health.19 However, there remain persistent and large health disparities between Indigenous and white Minnesotans on almost all health measures. In particular, across all racial groups in Minnesota, Indigenous populations have the highest mortality rates.2

UMMSD is a regional campus of the University of Minnesota Medical School and is focused on years 1 and 2 of undergraduate medical education. It opened in 1972 and has the explicit mission “to be a leader in educating physicians dedicated to family medicine, to serve the health care needs of rural Minnesota and American Indian communities, and discover and disseminate knowledge through research.”20 Mission statements often reflect institutional values and outcomes, and in reviewing the mission statements of all U.S. medical schools, we found that UMMSD is unique in its stated focus on Indigenous health.21 In working toward this mission, UMMSD has a strong track record of supporting Indigenous students pursuing medical degrees. In 1987, the Center of American Indian and Minority Health was established to support this mission, and an American Indian and Alaska Native physician pipeline was created. Since then, UMMSD has trained over 100 American Indian and Alaska Native physicians. Over the last five years, the incoming class has averaged 5.6 Indigenous students, representing 9% of the student body. In 1994, an elective course entitled “Seminars in Indian Health” was first offered to Indigenous students, and in 2013, was opened to all medical students. In addition, there are six medical school faculty members who are Indigenous, representing 15% of the faculty; Indigenous faculty make up just 0.1% of medical school faculty nationwide.22 Given the mission and history of UMMSD, this project to develop an Indigenous health curriculum represented the next logical step in advancing the mission of serving the health care needs of Indigenous people.

Guiding Principles

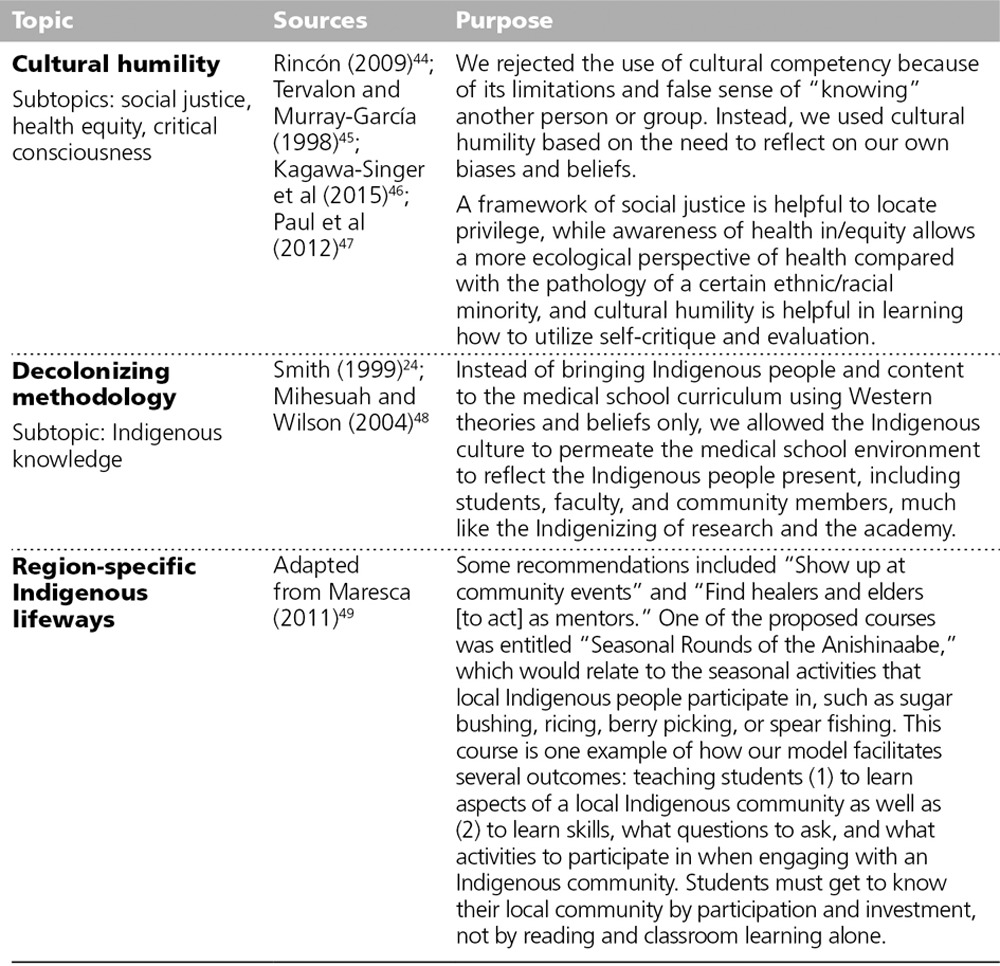

We used the principles of community-based participatory research23 as well as a decolonizing methodology24,25 to embrace and gather knowledge from the local community around what content should be included in a medical school curriculum to improve the health of the local Indigenous community and to improve patient–provider interactions. The community-based participatory research approach invites a multidisciplinary team, using a flattened hierarchy, to approach an issue that has been prioritized by community members.26–28 The decolonizing and Indigenous approaches (which look different from traditional Western scientific methodologies) aim to use Indigenous beliefs and knowledge to guide the research methodology in an effort to restore equity and balance to Indigenous people throughout the research process.24–28 For instance, we used foundational Indigenous values and practices to guide conversations about the development of an Indigenous health curriculum, including using appropriate protocols to begin meetings, privileging Indigenous voices and belief systems, and providing local and traditional foods thereby supporting local Native-owned businesses (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Guiding Principles Used to Develop an Indigenous Health Curriculum at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus, 2014

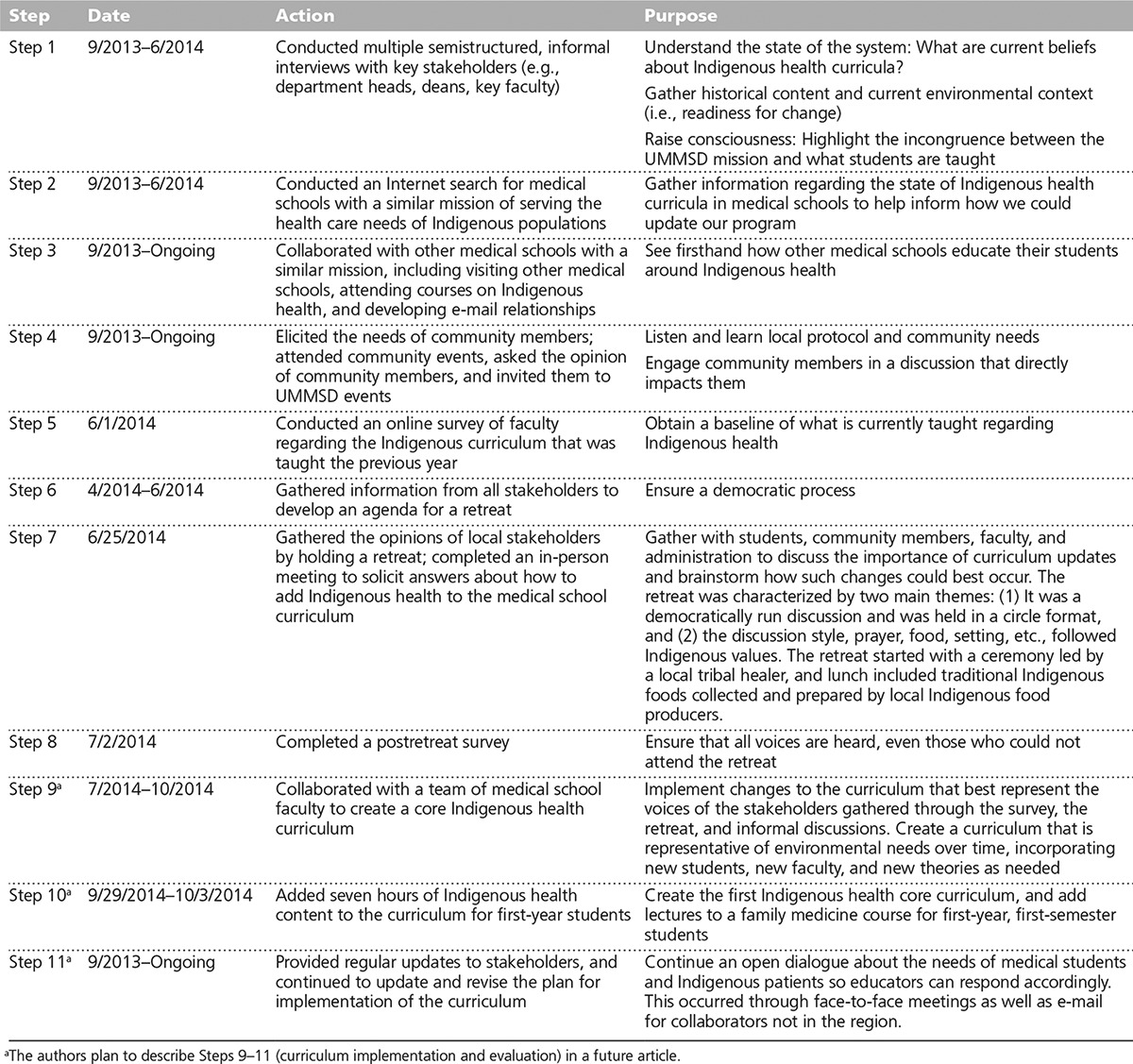

We implemented the action research cycle to capture the needs of multiple groups over time. The steps in this model include plan, act, observe, reflect, and iterate; once these steps are complete, the cycle starts over again with a revised plan.23 We also incorporated Kern’s six-step guide to curriculum development: (1) problem identification and general needs assessment, (2) needs assessment for targeted learners, (3) goals and objectives, (4) educational strategies, (5) implementation, and (6) evaluation and feedback.29 The combination of the community-based participatory research methodology, the action research cycle, and Kern’s six-step guide to curriculum development led us to implement an 11-step, mixed-methods needs assessment that informed the eventual instructional design of the Indigenous health curriculum (see Table 2). In the sections that follow, we describe Steps 1–8 of this process in more detail.

Table 2.

Steps to Develop an Indigenous Health Curriculum at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus (UMMSD)

Gathering Background Information (Steps 1–3)

The first three steps in this project were to listen and learn from key stakeholders and Indigenous health experts. From September 2013 to June 2014, we spoke with stakeholders within the medical school to learn about the mission, history, and current state of education around Indigenous health. During the same time period, we gathered information from programs around the world that had already implemented Indigenous health education curricula. We gathered this information using academic literature searches, Internet searches, phone calls, and in-person visits.

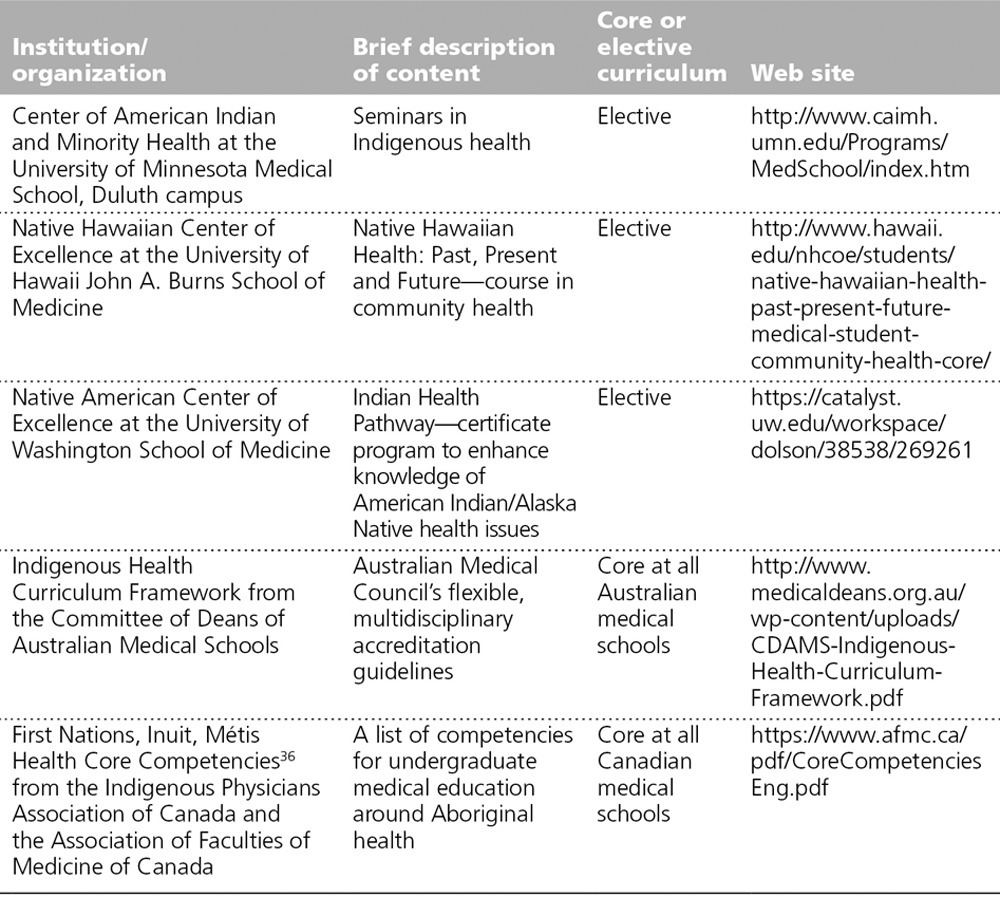

To complete the literature search, we used the Ovid and Education Resources Information Center databases to identify any articles describing Indigenous health content within medical school curricula. We identified other relevant curricula using Internet searches and discussions with faculty from these institutions (see Table 3 for our findings). For example, the University of Washington School of Medicine Indian Health Pathway is an elective program incorporating course work, a research project related to American Indian health, four weeks of clerkships/preceptorships, and service learning experiences. The University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine offers an elective entitled “Healthcare in Native Hawaiian Communities” for fourth-year medical students; the course includes a rotation at an Indigenous-serving site where students are mentored and evaluated by a traditional healer.

Table 3.

Examples of Indigenous Health Content Included in Medical Education Programs, 2014

Outside the United States, in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, core competencies in Indigenous health have been identified.30,31 The Northern Ontario School of Medicine incorporates competencies that were identified in partnership with community members into the required courses taken by all medical students.32 Additional opportunities for medical training focused on Indigenous health are available post graduation, and many of these programs use Web-based training and have core pedagogies. For instance, an online training program in Indigenous cultural competency out of British Columbia allows physicians and mental health professionals to receive continuing education credits.33 In Australia, several universities have enacted pilot projects that implemented Indigenous cultural competency curricula for faculty, staff, and students.31

We compiled these international best practices in Indigenous health training to guide the development of our Indigenous health curriculum.

Preparing for the Stakeholder Retreat (Steps 4–6)

Through our work during Steps 1–3, key medical school stakeholders became aware of and came to support our efforts to improve the Indigenous health content in the curriculum. In preparation for convening a group to decide on the specific content of this curriculum, we built relationships with local Indigenous community members through a mostly informal process of attending local events and engaging in conversations about this topic. This step was important because the medical school’s presence within the community was critical to balancing an already-unbalanced hierarchy. To achieve this goal, we used a listener–learner lens. Next, in June 2014, we asked all medical school faculty to complete a baseline survey on the exact Indigenous health content already in the curriculum. Self-selected individuals—mainly faculty—then worked together to create an agenda for a retreat at which all stakeholders would come together and discuss what content should be included in the curriculum.

Conducting the Stakeholder Retreat and Survey (Steps 7–8)

In June 2014, we held a retreat to gather stakeholders’ opinions of what Indigenous health content should be included in the curriculum and in what way. All first- and second-year medical students, all medical faculty, and community members determined to be experts in Indigenous health were invited by e-mail or phone to attend. The faculty and staff created a list of potential community member participants. From this list, we used a quasi-snowball method asking these community members to invite other community members who they thought would be able to contribute to the retreat. We held an informal discussion at the retreat meant to guide curriculum development and implementation. In addition, we distributed surveys to all retreat invitees via e-mail to ensure that all voices would be heard, even those who could not attend the retreat.

The University of Minnesota institutional review board deemed our project to be exempt from review, given its focus on curricular review and planning.

Stakeholder survey content

We used the material we gathered during Steps 1–7 (see Table 2) to develop survey questions that would guide the actual curriculum development and implementation in a tangible way. We asked stakeholders to indicate how strongly they believed that certain content should be added to the curriculum, using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (with 1 indicating “not important” and 5 indicating “very important”) as well as how that content should be taught and by whom (both quantitative and open-ended response formats). Stakeholders also responded to the following broad, open-ended questions about the delivery and purpose of the Indigenous health curriculum: (1) What role should UMMSD have in moving forward Indigenous health? (2) What do medical students need to be prepared to work with Indigenous patients, families, and communities? and (3) What style of teaching is needed?

Responses were coded by a student assistant and then confirmed by the first author (M.L.). We used descriptive qualitative analysis to identify themes.

Stakeholder survey results

A total of 29 individuals participated in the survey, including 13 (45%) medical school faculty members, 5 (17%) medical students, 4 (14%) medical school faculty members from another institution (2 of whom were physicians), 3 (10%) staff, 1 (3%) faculty member from the University of Minnesota but not from the medical school, 1 (3%) clinical medical provider (e.g., physician or nurse practitioner), 1 (3%) tribal public health nurse, and 1 (3%) retired medical school faculty member.

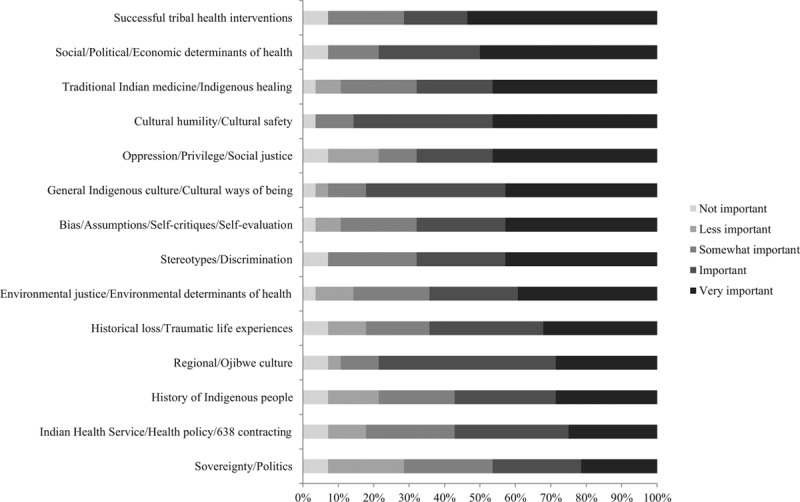

Respondents rated themselves an average of 4.5 out of 7.0 when they were asked how knowledgeable they felt about the topic of Indigenous health. However, 16 (53%) respondents rated themselves a 5.0 or higher. Respondents (more than one response allowed) indicated that they thought medical school faculty and tribal members (23 [26%] each) should teach this content along with faculty from other complementary departments (e.g., American Indian Studies, Education, Social Work, History) (19; 22%), community members (15; 17%), and others (e.g., local and regional experts, policy makers in government) (8; 9%). When asked about the type of content that should be added to the preclinical curriculum, all 14 content areas listed on the survey received at least a 6 out of 10, indicating that all topics held some importance to respondents (see Figure 1). The top-scoring content areas were cultural humility/cultural safety, general Indigenous culture/ways of being, social/political/economic determinants of health, and successful tribal health interventions, while the lowest-scoring content areas were sovereignty/politics, Indian Health Service/health policy/638 contracting, history of Indigenous people, and oppression/privilege/social justice.

Figure 1.

Percentage of stakeholders indicating the importance of including each Indigenous health topic in the curriculum at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus, 2014. Stakeholders, including faculty, staff, students, and community members, were asked to use a Likert scale from 1 to 5 to indicate how important including the listed topics in the curriculum was to them, with 1 indicating “not important” and 5 indicating “very important.”

The responses to the open-ended questions resulted in two overarching themes: (1) collaborative spirit and action: a call to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities, other universities, interdisciplinary health professionals, and interdisciplinary departments that work with Indigenous people; and (2) holistic training of medical students to become effective providers to Indigenous patients. This second theme includes mandatory didactic and experiential training (highlighting Indigenous history along with social justice and cultural humility training) from experts in Western medicine and Indigenous communities.

Specifically, in response to the first open-ended question, “What role should UMMSD have in moving forward Indigenous health?” respondents overwhelmingly discussed the importance of a true collaboration with other entities, such as other health professionals and Indigenous people of Minnesota. Responses ranged from “we should live up to our mission statement” to “[we should] work on connectivity with other institutions working to train MDs but also PAs, nurses, and other allied health professionals.” Several responses highlighted the importance of listening to the needs of the community: “It’s also important to do this in consultation with Minnesota’s tribes, to ensure that community needs are under constant assessment and integrated deeply into this program.” Responses emphasized that, given the mission, UMMSD needs to connect with Indigenous community members to guide the education of students in Indigenous health and to do so in a sustainable way.

The second open-ended question, “What do medical students need to be prepared to work with Indigenous patients, families, and communities?” resulted in several responses related to education around Indigenous history and culture, cultural sensitivity, and Indigenous ways of healing. Specific educational requests included that medical students “need to understand the vast diversity that exists among American Indian peoples and nations.” Another response suggested that specific educational content needed “a very basic ‘AI studies 101.’… Basic info on IHS, service [opportunities] and obligations, interfacing with tribal governments, etc.” This request for content on tribal health care systems and forms of government was echoed by another participant who called for

in-depth cultural sensitivity training, thorough education of the true history of American Indians in the Americas, be well versed in the history of government, political and legal aspects that have surrounded, and continue to impact our people. They also need quality, hands-on residencies within agencies that provide health and social services for American Indians.

Responses to this second question also addressed historical trauma, socioeconomic challenges, traditional healing methods, and Indigenous knowledge dissemination. For instance, one respondent indicated that medical students should be aware “of the history of mistrust and of different socioeconomic challenges. They need more than just an understanding of the basics of our culture.” Another respondent offered that “a starting point is immersion and exposure to culture, traditional healing, and people’s current experience and concerns in health care.” A third respondent commented on Indigenizing the medical school by saying:

Personally, instead of just training more Native [medical] students to be fluent in Western medicine, I’d prefer to see the university reform itself and its systems of knowledge production to cultivate the emergence of an identity as an Indigenous doctor/health worker, skilled in both Western and traditional.

Responses to the third open-ended question, “What style of teaching is needed?” called for a mix of teaching methods. However, the combinations of teaching methods varied. Some suggested “mixed—didactic as well as experiential if possible” or “short lecture format (30 min) that focuses on one or two key points.” Others recommended “panel” or “experiential.” Regardless of which teaching style they recommended, many suggested that a connection to community teachers was necessary:

Much of this is best learnt by immersion in the community so, if possible, a community visit should be included. At the very least there is a need for community/tribal members to teach this but also faculty who have worked with or are from these communities will be invaluable.

Finally, several responses suggested bringing in speakers:

Inviting physicians (both Native and non-Native) into the classroom to talk about their experiences with Indigenous patients can be very powerful, as well as inviting those patients themselves to talk about their experiences in—and frustrations with—our health care system.

Outcomes and Implications

The purpose of this project was to engage stakeholders to identify the core content for an Indigenous health curriculum to be implemented in the first year of medical school and to identify strategies for delivering this content. Preliminary outcomes of this project include the addition of a seven-hour block of Indigenous lectures for first-year medical students taught primarily by Indigenous faculty from several departments, including American Indian Studies, Education, Family Medicine, and Biobehavioral & Population Health. This block includes sessions on the history of Indigenous people; sovereignty and politics; Indigenous identity; local (Anishinaabe and Dakota) culture (specifically, seasonal rounds) and spirituality; the history of medical racism; an Indian Health Service brief; and strategies for working with Indigenous populations. Lectures are delivered in the context of several driving theories selected by the curriculum team, including cultural humility, decolonizing methodology, and region-specific Indigenous lifeways (see Table 1).

Numerous time- and environment-specific events contributed to the development of this curriculum. First, collaboration among Indigenous faculty both within and outside UMMSD was helpful in gathering a new and informed view of the needs of medical students. Second, UMMSD had reached a critical mass of Indigenous faculty that allowed for expanded discussions around Indigenous health and more diverse viewpoints. Third, UMMSD is part of a university, city, and state that have a higher percentage of Indigenous people compared with other regions, and this region is well known for its programs around Indigeneity. Fourth, UMMSD has had the mission to serve the health care needs of Indigenous communities for more than 30 years, which laid the foundation for improvement in Indigenous health education. Fifth, eliciting the opinions of Indigenous students and community members was significant in advancing these changes in the curriculum. Sixth, demonstrating what an Indigenous-led event looks like in holding the stakeholder retreat in the way that we did was powerful because (1) it allowed Indigenous guests to feel more comfortable in voicing their opinion, (2) it allowed non-Indigenous guests to learn in a nonthreatening way, and (3) it modeled an Indigenized medical school meeting.

Although no studies have examined the effects of adding Indigenous health content to a medical school curriculum, one study did demonstrate that medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and confidence around health disparity information increased when this topic was taught in medical school.13 Further, medical schools with social missions graduate more students who choose to practice primary care and in underserved populations, suggesting that the mission and curriculum content of the university do influence the type of care students eventually provide.21 Finally, high school students in California who received an ethnic studies course had higher grades and attendance and course completion rates compared with those who did not take the course.34 These results were even more pronounced for ethnic minorities. Applying these findings to a medical school environment suggests that a curriculum that incorporates culture and diversity content may support the recruitment and retention of minority students.

Limitations

We completed this project at a single institution, so we do not know if the methodology and outcomes are transferable to other institutions. However, our use of a region-specific model coupled with cultural humility theory provides other educators located across the globe with a model for curriculum development. Next, this project followed the development and implementation of an Indigenous health curriculum but currently lacks any evaluation to determine its effectiveness. However, we plan to assess the short- and long-term learning of students by examining their cultural empathy, cultural intelligence, social justice beliefs, and Indigenous knowledge. In the future, we plan to determine the impact of this Indigenous health curriculum on (1) medical students’ interactions with patients and (2) patients’ health outcomes. We also plan to assess the effectiveness of the experiential training techniques used to deliver the curriculum—objective structured clinical examinations, problem-based learning cases, clerkships, internships, and other immersive experiences—to determine which practices are most effective in preparing medical students to work with Indigenous communities.35–39

Next Steps

Our survey results suggest that (1) interdisciplinary collaboration, (2) the two-way sharing of knowledge with Indigenous community members and the subsequent incorporation of Indigenous health beliefs into medical education, and (3) experiential learning are valued next steps in this project. Therefore, we hope to engage community advisory boards as well as Indigenous health curriculum teams to guide this work in the future. Some universities have even created an elder-in-residence position to increase the presence of Indigenous people and expertise in medical education (e.g., University of Washington, University of North Carolina, Fort Lewis College, and McMaster University).39 Further, learning objectives for students and pedagogical principles40 for faculty and students must be created to guide future curriculum development. These guidelines can be integrated with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education cultural competence and health care disparities standard.41 Of course, these updates require training for faculty and staff to effectively work within an Indigenous pedagogy.

In addition, some argue that there is a hidden curriculum in medical education that comprises the learning that occurs from trainees’ exposure to the medical environment rather than the formal curriculum.42 We did not take into account the learning environment in this project, but we believe that it may have an important impact on students’ beliefs and therefore practices, so we suggest that further inquiry is needed in this area. In our case, Indigenizing a medical school would involve changing the dominant practices and beliefs so that the learning environment and the people within it reflect Indigenous values.

Conclusions

All UMMSD medical students now complete an Indigenous-specific health block in their first year of medical school. This change happened as the result of the efforts of many over decades and without grant funding, which some community-based participatory research theorists say is the only way to create flattened hierarchies between researchers and community members and continue interventions beyond grant funding periods.43 We believe that Indigenizing the process of medical school curriculum development was critical to the success of our project, and we hope to continue infusing Indigenous principles and ways of being into medical education and practice to create a true partnership between these communities. Ultimately, we hope that this Indigenous health content assists in reducing the systemic biases present in medical schools and clinics to decrease Indigenous health disparities. However, more exploration is needed to determine what medical training is most effective in creating positive health outcomes for Indigenous people.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Dr. Melissa Walls, Stephanie Wille, and Lauren Vieaux for their contributions to this manuscript; Ge-Waden Dunkley and Gabrielle Benjamin for their assistance with the Internet search; Dr. Alan Johns for the historical content review; course directors Dr. Ruth Westra, Dr. Raymond Christiansen, and Dr. Jim Boulger for their support of this project; Dr. Jacob Prunuske for his time and expertise on mission-directed programs; Dr. Jim Allen and the Department of Biobehavioral Health & Population Sciences for supporting the stakeholder retreat; and the stakeholders and survey participants for their time and for sharing their expertise.

The term Indigenous encompasses a broad spectrum of people nationally and internationally who are native to their homelands (i.e., American Indian, Native American, First Nations, Aboriginal, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian). Although we use the term Indigenous in this article, we recommend that local and regional terms, in the tribe’s own language, be used whenever possible. Although not a proper noun, we capitalize Indigenous to indicate that we are discussing a specific subgroup of people.

An AM Rounds blog post on this article is available at academicmedicineblog.org.

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The University of Minnesota institutional review board deemed this project to be exempt from review, given its focus on curricular review and planning.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Office of Minority and National Affairs. Mental health disparities: American Indians and Alaska Natives. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/workforce/mental_health_disparities_american_indian_and_alaskan_natives.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 2.Indian Health Service. Disparities. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/index.cfm/factsheets/disparities/. Published March 2016. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2014. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/2014-report-estimates-of-diabetes-and-its-burden-in-the-united-states.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 4.Honor the Earth. Sustainable Tribal Economies: A Guide to Restoring Energy and Food Sovereignty in Native America. 2009Minneapolis, MN: Honor the Earth. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minnesota Department of Health & Healthy Minnesota Partnership. The health of Minnesota: Statewide health assessment. http://www.health.state.mn.us/healthymnpartnership/sha/docs/1204healthofminnesota.pdf. Published April 2012. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 6.Prieto DO. Native Americans in medicine: The need for Indian healers. Acad Med. 1989;64:388–389.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasnapp J, Butrick E, Jamerson S, Espinoza M. Assessment of clients health needs of two urban Native American health centers in the San Francisco Bay Area. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:1060–1067.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly L, Brown JB. Listening to native patients. Changes in physicians’ understanding and behaviour. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1645–1652.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walls ML, Gonzalez J, Gladney T, Onello E. Unconscious biases: Racial microaggressions in American Indian health care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:231–239.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonds VW, Christopher S, Sequist TD, Colditz GA, Rudd RE. Exploring patient–provider interactions in a Native American community. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:836–852.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. http://lcme.org/publications/. Published March 2016. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 12.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84:782–787.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez CM, Fox AD, Marantz PR. The evolution of an elective in health disparities and advocacy: Description of instructional strategies and program evaluation. Acad Med. 2015;90:1636–1640.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lypson ML, Ross PT, Kumagai AK. Medical students’ perspectives on a multicultural curriculum. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1078–1083.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Improving underrepresented minority medical student recruitment with health disparities curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S82–S85.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewen SC, Pitama SG, Robertson K, Kamaka ML. Indigenous simulated patient programs: A three-nation comparison. Focus Health Prof Educ. 2011;13:35–43.. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips G; Project Steering Committee, Committee of Deans of Australian Medical Schools. CDAMS Indigenous health curriculum framework. http://www.limenetwork.net.au/files/lime/cdamsframeworkreport.pdf. Published August 2004. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 18.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Minnesota. 2015. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/27,00. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 19.United Health Foundation. America’s health rankings: 2015 annual report: Minnesota. http://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/2015-annual-report/state/MN. Published 2016. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- 20.University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus. Mission statement. http://www.med.umn.edu/about/our-campuses-duluth-and-twin-cities/duluth-campus. Published 2016. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 21.Morley CP, Mader EM, Smilnak T, et al. The social mission in medical school mission statements: Associations with graduate outcomes. Fam Med. 2015;47:427–434.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medical Education: Facts and Figures 2012. 2012Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Toole TP, Aaron KF, Chin MH, Horowitz C, Tyson F. Community-based participatory research: Opportunities, challenges, and the need for a common language. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:592–594.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 1999London, UK: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis M, Myhra L, Walker M. Hodgson J, Lamson A, Mendenhall T, Crane DR. Advancing health equity in medical family therapy research. Medical Family Therapy: Advanced Applications. 2014:New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 319–340.. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 suppl 2):ii3–ii12.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Minkler M, Wallerstein N. The conceptual, historical and practical roots of community based participatory research and related participatory traditions. In: Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2003:San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 27–52.. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chilisa B. Indigenous Research Methodologies. 2012Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. 20092nd ed Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada. First Nations, Inuit, Métis health core competencies. A curriculum framework for undergraduate medical education. https://www.afmc.ca/pdf/CoreCompetenciesEng.pdf. Updated April 2009. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 31.Universities Australia. Indigenous cultural competency framework. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/uni-participation-quality/Indigenous-Higher-Education/Indigenous-Cultural-Compet#.V9b8XKKuMRt. Published January 14, 2014. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 32.Jacklin K, Strasser R, Peltier I. From the community to the classroom: The Aboriginal health curriculum at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine. Can J Rural Med. 2014;19:143–150.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Provincial Health Services Authority in BC. Indigenous cultural safety online training program. http://www.sanyas.ca/home. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 34.Dee T, Penner E.The casual effects of cultural relevance: Evidence from an ethnic studies curriculum. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis Web site. http://cepa.stanford.edu/wp16-01. Published 2016. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 35.Crowshoe L, Bickford J, Decottignies M. Interactive drama: Teaching aboriginal health medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39:521–522.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamaka ML. Designing a cultural competency curriculum: Asking the stakeholders. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69(6 suppl 3):31–34.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers KD, Coulehan JL. A community medicine clerkship on the Navajo Indian reservation. J Med Educ. 1984;59:937–943.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones R, Pitama S, Huria T, et al. Medical education to improve Māori health. N Z Med J. 2010;123:113–122.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bach D.Elders-in-residence program brings traditional learning to campus. UW Today. February 6, 2015. http://www.washington.edu/news/2015/02/06/elders-in-residence-program-brings-traditional-learning-to-campus/. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 40.Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education Network. Pedagogical principles & approach. http://www.limenetwork.net.au/content/pedagogical-principles-approach. Published 2016. Accessed September 12, 2016.

- 41.Association of American Medical Colleges. Cultural competence education. https://www.aamc.org/download/54338/data/culturalcomped.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- 42.Ewen S, Mazel O, Knoche D. Exposing the hidden curriculum influencing medical education on the health of Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand: The role of the critical reflection tool. Acad Med. 2012;87:200–205.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doherty WJ, Mendenhall TJ. Citizen health care: A model for engaging patients, families, and communities as coproducers of health. Fam Syst Health. 2006;24:251–263.. [Google Scholar]

References cited in Table 1 only

- 44.Rincón AM. Berthold T, Avila A, Miller J. Practicing cultural humility. Foundations for Community Health Workers. 2009:135–San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 154. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–125.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler WW, George SM, Elwood WN. The Cultural Framework for Health: An Integrative Approach for Research and Program Design and Evaluation. 2015. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; https://obssr-archive.od.nih.gov/pdf/cultural_framework_for_health.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paul D, Hill S, Ewen S. Revealing the (in)competency of “cultural competency” in medical education. AlterNative. 2012;8:318–329.. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mihesuah DA, Wilson AC. Indigenizing the Academy: Transforming Scholarship and Empowering Communities. 2004Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maresca T. Strengthening our roots: One region’s experience with traditional medicine and healthcare settings. Paper presented at: Annual Advances in Indian Health Conference; May 3, 2011; Albuquerque, NM. [Google Scholar]