ABSTRACT

Biofilm formation is a universal virulence strategy in which bacteria grow in dense microbial communities enmeshed within a polymeric extracellular matrix that protects them from antibiotic exposure and the immune system. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an archetypal biofilm-forming organism that utilizes a biofilm growth strategy to cause chronic lung infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. The extracellular matrix of P. aeruginosa biofilms is comprised mainly of exopolysaccharides (EPS) and DNA. Both mucoid and nonmucoid isolates of P. aeruginosa produce the Pel and Psl EPS, each of which have important roles in antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and immune evasion. Given the central importance of the EPS for biofilms, they are attractive targets for novel anti-infective compounds. In this study, we used a high-throughput gene expression screen to identify compounds that repress expression of the pel genes. The pel repressors demonstrated antibiofilm activity against microplate and flow chamber biofilms formed by wild-type and hyperbiofilm-forming strains. To determine the potential role of EPS in virulence, pel/psl mutants were shown to have reduced virulence in feeding behavior and slow killing virulence assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. The antibiofilm molecules also reduced P. aeruginosa PAO1 virulence in the nematode slow killing model. Importantly, the combination of antibiotics and antibiofilm compounds increased killing of P. aeruginosa biofilms. These small molecules represent a novel anti-infective strategy for the possible treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa infections.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, high-throughput screening, exopolysaccharides, Pel matrix, antibiofilm, antivirulence, Caenorhabditis elegans

INTRODUCTION

Biofilm formation is a universal virulence strategy adopted by bacteria to survive in hostile environments (1, 2). The Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a remarkable biofilm-forming species that commonly establishes chronic infections in the lungs of patients with the genetic disease cystic fibrosis (CF) (2, 3). Growth as a biofilm promotes multidrug resistance to antibiotic interventions and evasion of immune clearance (1, 4). Biofilm formation is a conserved process of attachment, maturation, and dispersion, where sessile bacterial aggregates are held together by a protective polymeric extracellular matrix comprised mainly of exopolysaccharides (EPS) and extracellular DNA (eDNA) (1, 5–8). P. aeruginosa strains produce three different EPS molecules: alginate, Pel, and Psl (9). Pel and Psl are the major EPS produced in the early CF colonizing, nonmucoid isolates (10, 11) and also contribute to biofilm formation in mucoid CF isolates, which overproduce alginate and emerge as the infection progresses (8, 12).

Both Pel and Psl have diverse roles in biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and immune evasion, and their overproduction leads to hyperaggregative small colony variants (SCVs) (1, 13). Pel is a positively charged EPS formed by partially acetylated galactosamine and glucosamine residues, with both cell-associated and secreted forms (14). Psl is a neutrally charged EPS comprised of repeating pentamers of d-mannose, d-glucose, and l-rhamnose, which can also be found as part of the bacterial capsule and secreted to form the biofilm matrix (6, 15). Both Pel and Psl are able to initiate biofilm formation (1, 16). Pel is critical for the formation of pellicles in the air-liquid interface (1, 16). Pel also has a structural role in cross-linking eDNA, establishing the scaffold of the biofilm (14). In the Drosophila melanogaster oral feeding model, Pel is highly expressed and required for biofilm formation in the fruit fly crop, limiting bacterial dissemination in chronic fruit fly infections (17). Psl arranges in fiber-like structures that are also crucial for cell surface interactions, matrix development, and biofilm architecture (1, 6, 7). Both Pel and Psl are also involved in antimicrobial resistance, where Pel is crucial for biofilm resistance to aminoglycosides (16) and Psl contributes to short-term tolerance to polymyxins, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics (18). Further, Psl has also been shown to reduce recognition by the innate immune system, blocking complement deposition on the bacterial surface and reducing phagocytosis, release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cell killing by neutrophils (19). The polymers in the extracellular matrix also contribute to shaping the environmental conditions within a biofilm, influencing signaling and migration, which are independent from their structural role (20).

Biofilms are intimately related to antibiotic tolerance and persistent infections (16, 21); therefore, there is an urgent need for the identification of new approaches that target the biofilm mode of growth for the prevention or treatment of chronic bacterial infections. In order to identify new molecules effective against biofilms, high-throughput screening (HTS) approaches have been employed to screen large numbers of compounds that reduce biofilm formation and/or detach preformed biofilms in many species of bacteria (22–26).

Given the importance of Pel and Psl in P. aeruginosa biofilm formation, they are attractive targets for antibiofilm drug development. In this study, we used an HTS gene expression approach to screen a 31,096-member small molecule drug library for compounds that repress pel gene expression. Consistent with our hypothesis, the pel repressor compounds inhibited EPS secretion and also had significant antibiofilm activity. Further testing of these compounds revealed their antivirulence activity in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model and their ability to promote biofilm killing when used in combination with conventional antibiotics. The anti-infective compounds identified here are an example of a new strategy for the possible treatment of P. aeruginosa infections as they do not inhibit bacterial growth but reduce the expression of virulence mechanisms used to promote chronic infections.

RESULTS

High-throughput screening for repressors of EPS gene expression.

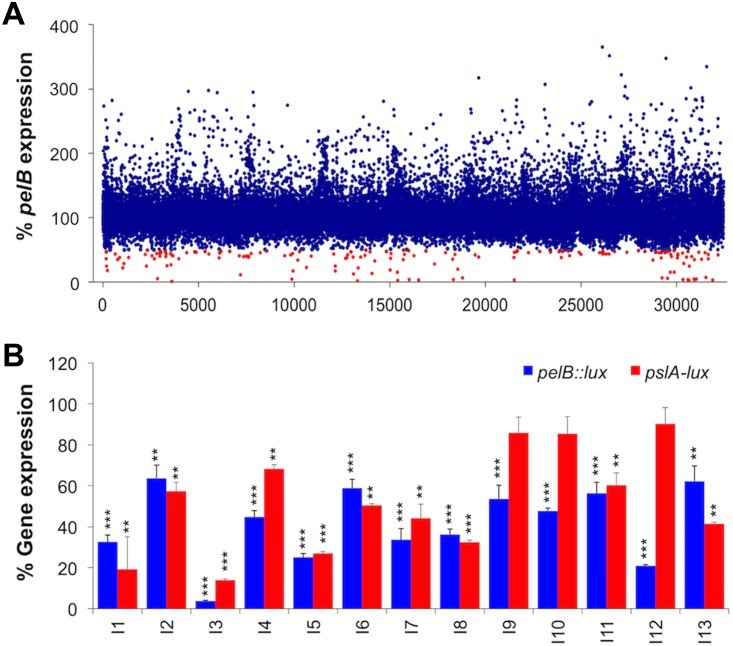

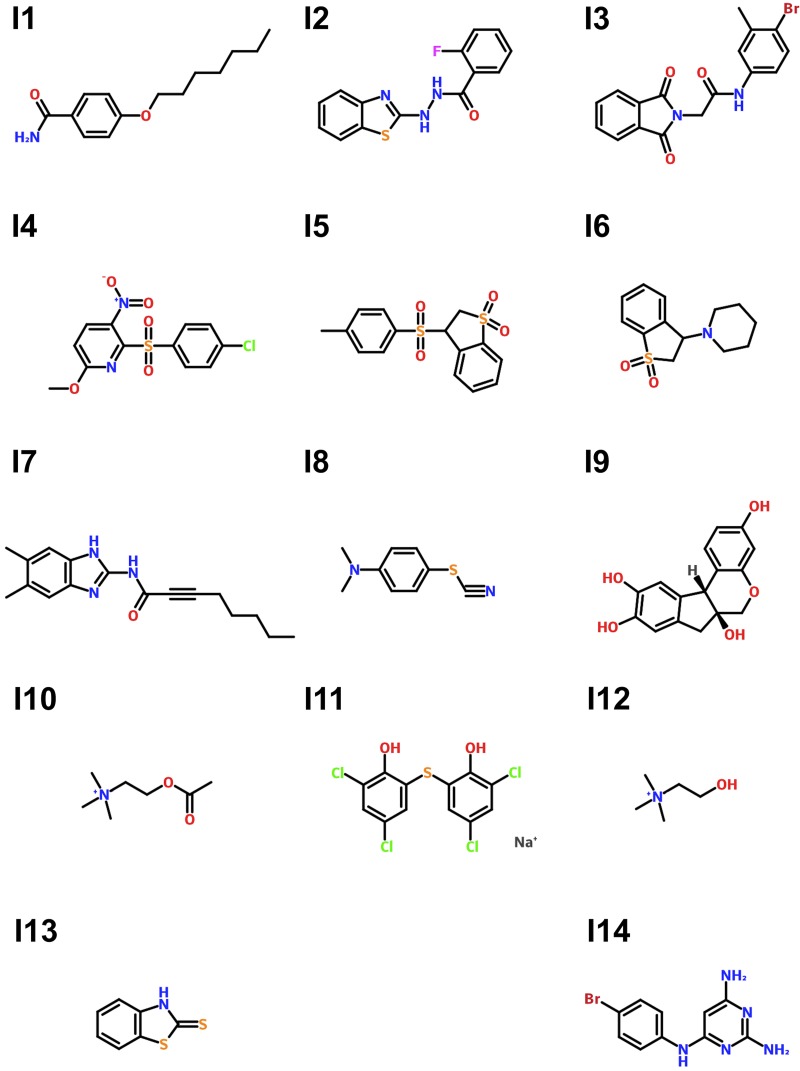

An HTS for compounds that repress expression from a pelB::lux reporter was performed in the 384-well microplate format using the Canadian Chemical Biology Network (CCBN) drug library containing 31,096 small molecule compounds. The P. aeruginosa pelB::lux reporter was grown in defined basal minimal medium BM2 with limiting 20 μM magnesium (Mg2+), which we have identified previously as a growth condition that promotes biofilm formation, due to increased expression and production of EPS (5). In the primary HTS, we tested the ability of compounds at concentrations of ∼10 μM to reduce pel gene expression. Gene expression was measured at a single time point (14 h) in each well of 384-well microplates and normalized to the mean gene expression of each microplate. With this approach, we were able to identify 163 compounds that reduced pel gene expression by at least 50% (Fig. 1A). In a secondary screen of retesting the initial 163 hits, 14 compounds were identified that consistently repressed pelB::lux expression by 50% or greater, without any effect on growth. The structures of the 14 pel repressors are shown in Fig. 2 and are described in Table S2 in the supplemental material. There were an additional 26 compounds that acted as pelB::lux repressors but that also had bactericidal or bacteriostatic properties (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), highlighting the ability of this screen to also find antimicrobial compounds.

FIG 1.

High-throughput screen identifies small molecules that reduce pelB expression. (A) Gene expression was monitored in a HTS to test the effect of 31,096 individual small molecules on pelB::lux expression. Gene expression was measured at 14 h and divided by the mean gene expression from each 384-well plate and represented as a percentage of gene expression. The primary screen identified 163 repressor “hits” (red) that inhibited gene expression by 50% or more. (B) Reordered lead compounds identified in the HTS were retested for their ability to repress expression of pelB::lux and pslA-lux transcriptional reporters. Total gene expression measured throughout 18 h is represented as the area under the curve and normalized to the untreated control (100%). The values shown are the average from triplicate values with standard deviation (n = 4). Significant repression is indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

FIG 2.

Molecular structures of the pel gene expression repressors identified in the HTS. Inhibitor (I) compounds are labeled 1 through 14. For more details see Table S2.

To confirm the gene repression ability of these compounds, 13 of the 14 molecules (I1 to I13) were reordered and retested, while one of the compounds was not commercially available. The 13 gene repressor compounds showed significant repression of the pelB::lux reporter (30 to 90%) (Fig. 1B), in comparison to the reporter strain cultured under biofilm-inducing conditions alone. Additionally, most of the compounds were also able to reduce expression of pslA-lux reporter by 10 to 85% (Fig. 1B), showing an effect over both EPS gene clusters. To determine if any of the compounds had any nonspecific effect on lux (luminescence), we measured the effects of 10 μM compounds on the expression of a control lux reporter plasmid, pMS402 (27), that has low levels of basal expression. There were minimal effects on lux expression from pMS402 for most of the molecules; however, one compound was a strong lux repressor (I3), and interestingly, one compound was a lux activator (I2) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Therefore, we repeated the gene expression experiments with the pelB::lux and pslA-lux reporters, normalized the results to the nonspecific effects on pMS402, and again demonstrated that most compounds were repressors of both pel (12/13) and psl (9/13) (Fig. S1B).

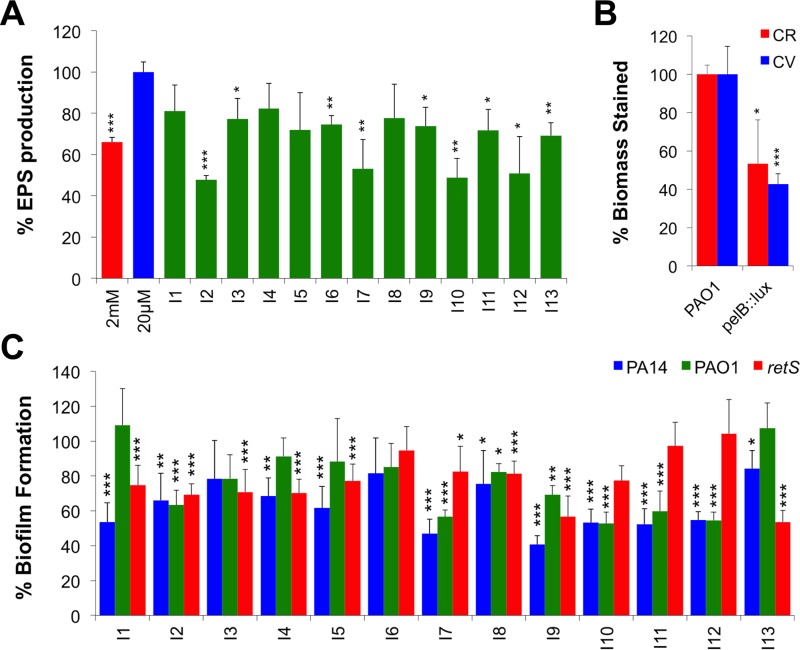

pel repressors reduce EPS secretion and biofilm formation under microplate and flow conditions.

To test our hypothesis that repressors of EPS gene expression will reduce biofilm formation, we initially assessed their ability to reduce EPS synthesis in the wild type PAO1 strain. Using the standard Congo red (CR) binding assay to quantitate total EPS (28), most of the pel repressors caused significant reduction in EPS secretion (Fig. 3A). We next wanted to investigate the compounds' ability to reduce biofilm formation. P. aeruginosa biofilms were cultivated in 96-well microplates in the absence or presence of the pel repressor compounds and quantitated using crystal violet (CV) staining (29). The majority of pel repressors caused significant reduction in the formation of PAO1 microplate biofilms (7/13) (Fig. 3C). The strongest antibiofilm compounds reduced EPS production and biofilm formation to levels comparable to those with the pelB::lux mutant, which presumably has no production of the Pel EPS (Fig. 3B). To study their antibiofilm effects in different strains of P. aeruginosa, we tested against the PA14 strain, which produces only Pel due to a 3-gene deletion in the psl cluster (10). The majority of pel repressors (11/13) promoted a significant reduction in biofilm formation in PA14 (Fig. 3C). We also tested their antibiofilm activity against the retS::lux mutant, which is known to overproduce both EPS, causing a hyperbiofilm phenotype (30) similar to the small colony variants that arise in biofilms and in the CF lung (2). Interestingly, 9/13 compounds were also effective in reducing biofilm formation in the retS::lux mutant strain (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Effects of pel repressor compounds on EPS production and biofilm formation. (A) Congo red (CR) was used to stain and quantitate secreted EPS after treatment with the 13 inhibitor compounds (n = 3). Green bars of treated biofilms were compared to PAO1 grown under a biofilm-inducing condition alone (blue). (B) EPS production (CR) and biofilm phenotypes (CV) of the pelB::lux mutant. (C) Crystal violet (CV) staining of biofilms formed in microplates after treatment of PA14, PAO1, and retS::lux biofilms. Treated biofilms were normalized to the positive control, and the percentage of inhibition values shown are the means from 6 replicates plus standard deviations (n = 3). Significant repression is indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

To assess the possible additive effects of combining the compounds, we tested the combination of 2 or 3 inhibitor compounds (at a total concentration of 10 μM). We initially tested 95 different combinations that included all 78 possible 2-compound mixtures and 17 random 3-compound mixtures and identified the best combinations as additive repressors of pelB::lux expression (data not shown). Using those combinations that showed the greatest effects on repressing pelB::lux expression, we confirmed that many of these mixtures were more effective in reducing biofilm formation than individual compounds (see Fig. S2A to C in the supplemental material).

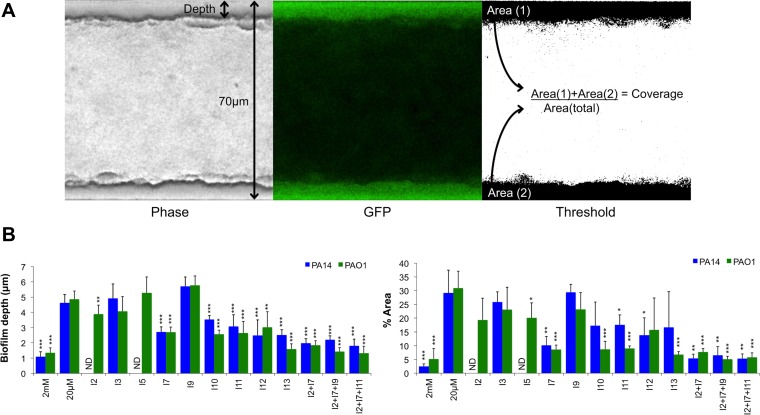

We next wanted to determine the antibiofilm effect of these compounds against biofilms formed in continuous flow systems, which tend to better mimic natural biofilms as they introduce hydrodynamic influences (31, 32). We quantitated green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged PA14 and PAO1 biofilms (PA14-gfp and PAO1-gfp, respectively) in the BioFlux biofilm device (Fig. 4A). Due to space limitations in this high-throughput device, we selected 9 individual antibiofilm compounds and 3 mixtures that showed strong biofilm inhibition in microplates. Again, the majority of individual compounds and the combination treatments significantly reduced the depth of biofilms formed by PAO1-gfp and PA14-gfp (Fig. 4B). The decreased depth was also reflected in reduced total coverage of biofilms grown in the BioFlux channels (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the CV biofilm assays (Fig. S2), all compound mixtures tested had greater effects on reducing biofilms than individual compounds alone (Fig. 4B). From the original 13 molecules identified as pel repressors, 7 compounds were considered significant antibiofilm molecules (I2, I7, I9, I10, I11, I12, and I13) (Table 1), because they caused significant defects in at least 2 out of 3 biofilm phenotypes, including EPS production, microplate, and flow biofilms.

FIG 4.

Antibiofilm activity against biofilms formed under flow conditions. (A) Schematic visualization of biofilms formed within channels of the BioFlux device. Biofilms formed along the walls of the chambers as seen by phase-contrast (left) and GFP (middle) imaging. The GFP image was threshold adjusted to isolate the biofilms adhered to the channel walls (right). Phase-contrast images were used to calculate the biofilm depth, and the GFP images were used to calculate the biofilm area coverage relative to the whole area of the channel. (B) Reductions of total biofilm depth and coverage (% Area) in the chamber are represented. Bars representing compound-treated PA14 and PAO1 biofilms were compared to those representing strains grown under biofilm-inducing conditions (20 μM). ND, not determined as channels containing compounds I2 and I5 were clogged. All values shown are the means from triplicate samples plus standard deviations (n = 2). Significant repression in biofilm formation is indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

TABLE 1.

Summary of results for PAO1 treated with the pel repressor small molecules

| Parameter | Result fora: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiofilmb/antivirulence |

Antibiofilmb |

Pel/Psl repressors |

||||||||||

| I7 | I9 | I10 | I11 | I2 | I12 | I13 | I1 | I4 | I5 | I6 | I8 | |

| pelB expression | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| pslA expression | +++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| CR assay (EPS) | ++ | + | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | + | − |

| CV assay (biofilm) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Flow biofilm assay (depth) | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | NDc | ND | − | ND | ND |

| Nematode antivirulence | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anaerobic biofilm | − | ++ | − | ND | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | + | ++ | − |

Statistically significant repression effects were scored as mild (+ [>15%]), moderate (++ [>30%]), strong (+++ [>50%]), or no effect (−).

Compounds were grouped as antibiofilm molecules if they reduced at least 2 out of 3 aerobic biofilm phenotypes (CR, CV, or flow biofilm assays).

ND, not determined.

EPS repressors have antibiofilm effects on anaerobic and mucoid biofilms.

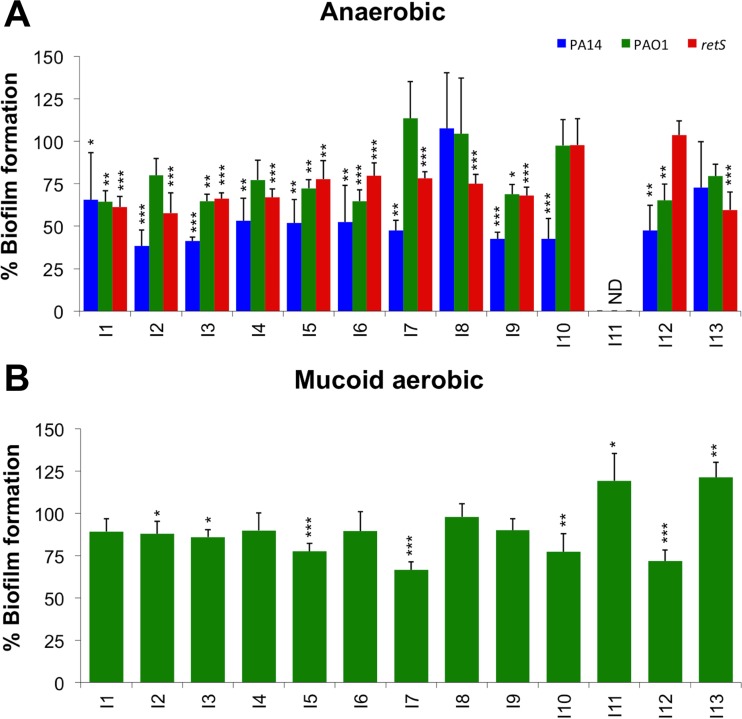

Previous reports have shown that the CF mucus plug environment consists of both aerobic and anaerobic microenvironments (33), which prompted us to monitor biofilms formed under anaerobic conditions. The antibiofilm compound treatments were able to significantly reduce biofilm formation in the PA14 strain under anaerobic conditions (10/13), while 6/13 compounds were effective against the PAO1 strain (Fig. 5A). Importantly, 10/13 compounds also reduced biofilm formation in the hyperbiofilm-forming mutant retS::lux strain under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

Effects of small molecule EPS repressors on anaerobic and mucoid biofilm formation. (A) Crystal violet (CV) staining of anaerobic biofilms formed in microplates after treatment of PA14, PAO1, and retS::lux strains. Bars of treated biofilms were compared to controls grown under biofilm-inducing conditions alone (100%). (B) Crystal violet (CV) staining of mucoid PDO300 (ΔmucA22) biofilms under aerobic conditions. Green bars representing compound-treated biofilms were compared to mucoid biofilms grown under EPS-repressing conditions. ND, not determined as I11 treatment killed all strains under anaerobic conditions. All values shown are the means from 6 replicates plus standard deviations (n = 3). Significant differences in biofilm formation/EPS secretion are indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

It is also known that the mucus-filled airways of the CF lung result in the selection of mucoid and alginate-overproducing P. aeruginosa, which contributes to chronic infection (21, 34, 35). Given the role of mucoid isolates and the contribution of Pel and Psl to biofilm formation and fitness of mucoid strains (36), we wanted to test the antibiofilm compounds against a mucoid strain. Biofilms of strain PDO300, a ΔmucA22 variant of PAO1 (37), were cultivated in BM2 medium containing 2 mM Mg2+, which reduces the contribution of Psl/Pel production in the biofilm matrix (5). Most compounds had no effect on mucoid biofilms, although some of them promoted minor decreases in biofilm formation (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly, two compounds promoted biofilm formation, increasing CV staining in the treated biofilms (Fig. 5B).

Pel and Psl are required for full virulence of PAO1 in the C. elegans infection model.

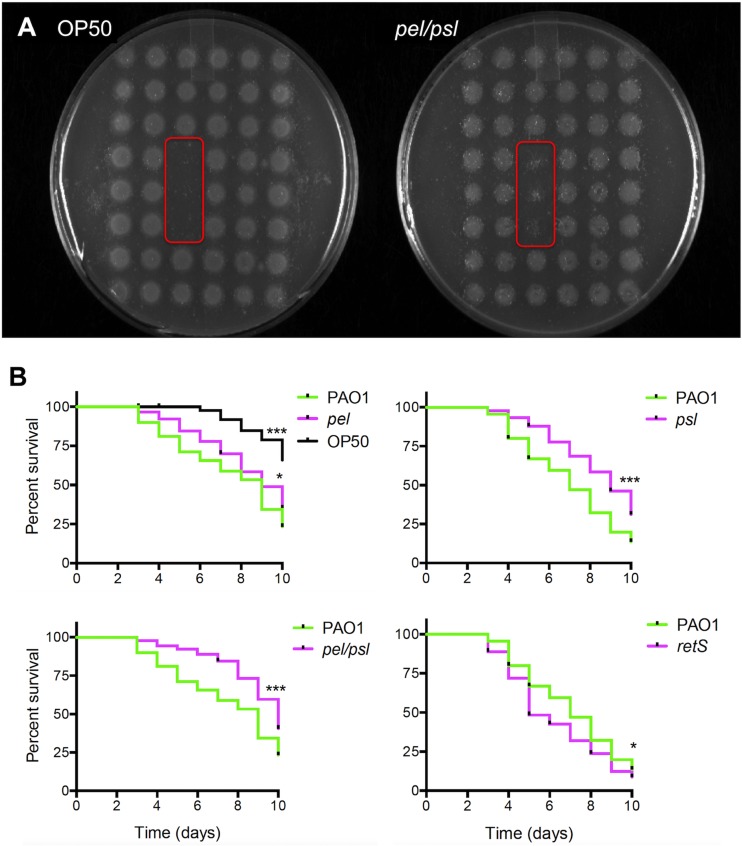

Although Pel and Psl are well appreciated for their role in biofilm formation, their contribution to virulence is less understood. P. aeruginosa is known to colonize and damage the intestinal lumen of C. elegans (38). During infection, P. aeruginosa forms aggregates in the nematode gut that are surrounded by an uncharacterized extracellular matrix (38). Therefore, to determine whether Pel and/or Psl contributes to bacterial virulence, we utilized the nematode infection model. We assessed the nematode feeding preference and slow killing assays when C. elegans worms were fed P. aeruginosa possessing mutations in the pel and psl gene clusters. Initially we used the feeding preference assay, where the nematodes are fed an array of test strains within a 6-by-8 grid of 48 colonies (39). Feeding is observed until colony disappearance, and colonies that are eaten preferentially were shown to be less virulent in the slow killing assays (39). While single knockouts in either the pel or psl genes did not alter the nematode feeding behavior, a double pel Δpsl mutant was preferentially eaten by C. elegans, when given the choice of between pel Δpsl and PAO1 (Fig. 6A). As a control experiment, the laboratory food source E. coli OP50 also served as a preferential food source to PAO1 (Fig. 6A). None of the mutant strains tested showed growth defects in SK media (data not shown). This preference in nematode feeding behavior for the double pel Δpsl mutant suggests a virulence role for Pel and Psl in vivo.

FIG 6.

The Pel and Psl exopolysaccharides are required for full virulence in the C. elegans infection models. (A) The feeding preference assay indicates that the pel Δpsl double mutant is a preferred food source and was eaten to completion before PAO1. Test strains were embedded in triplicate spots (red box) within a grid of 6 by 8 positions of wild-type PAO1 (n = 3). The E. coli OP50 strain was used as a positive control of the preferred food source known to have reduced virulence. (B) Slow killing curves of nematodes fed individual strains of either the PAO1 wild type or pelB::lux, Δpsl, pel Δpsl, or hyperbiofilm-forming retS::lux mutant. Kaplan-Meier curves were determined from three independent experiments (n = 30), where the total number of worms equals 90. Significant differences in nematode survival are indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

To further investigate the role of EPS in virulence, we conducted slow killing assays, in which nematodes are given a single bacterial food source and worm survival is monitored over 10 days (39, 40). In addition to the single and double pel Δpsl mutant panel, we also tested the EPS-hyperproducing retS::lux mutant. In the slow killing assay, both the single pel and psl mutants, as well as the double pel Δpsl mutant, were less virulent and resulted in increased nematode survival throughout 10 days (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, the retS::lux mutant, known to overproduce both Pel and Psl, demonstrated increased virulence in the slow killing assay (Fig. 6B), although this effect in the retS::lux mutant may be due to other pleiotropic effects of mutation in this regulatory protein (30). Taken together, these observations indicate that both the Pel and Psl are required for full virulence of P. aeruginosa in killing C. elegans.

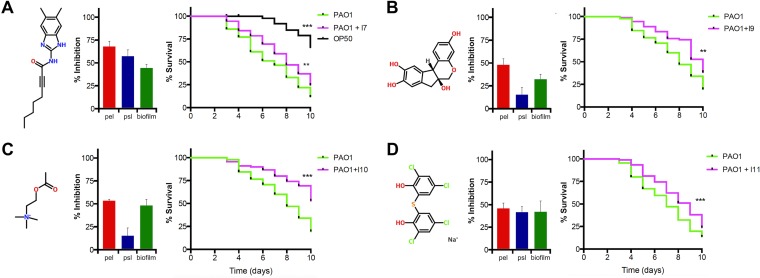

Antibiofilm molecules also have antivirulence activity.

Since Pel and Psl are required for full virulence of C. elegans (Fig. 6), we hypothesized that the antibiofilm compounds identified in the HTS would also reduce virulence of the wild-type PAO1. For the slow killing assay, PAO1 was inoculated as a lawn on agar plates that also included a 10 μM concentration of the antibiofilm compounds. Next, L4-stage nematodes were transferred to the plate containing compound-treated PAO1 food sources, and survival was monitored over time. Although no significant killing effects were observed for the majority of the compounds tested (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), compounds I7, I9, I10, and I11 caused a significant reduction in PAO1 virulence after 10 days of feeding on compound-treated bacteria (Fig. 7). This increase in nematode survival caused by the antibiofilm compounds was comparable to the antivirulence effects of feeding the nematodes pel and/or psl mutants (Fig. 6) or other mutants shown to have virulence defects in PAO1 for killing C. elegans (39). Slow killing experiments were also performed on nematodes fed E. coli OP50 with 10 μM concentrations of compounds I7, I9, I10, and I11, and there were no positive or negative effects on nematode survival (data not shown). These antibiofilm small molecules also demonstrate antivirulence activity for P. aeruginosa, likely due to their repression of EPS, which appears to be required for full virulence in the nematode.

FIG 7.

Antibiofilm compounds have antivirulence activity in the C. elegans slow killing infection model. Molecule structures for (A) I7, (B) I9, (C) I10, and (D) I11 are shown with their inhibitory effects over pelB::lux and pslA-lux expression and biofilm formation by PAO1 in microtiter plates. Kaplan-Meier curves (percentage of survival) show the worm killing kinetics. Nematodes were fed with 10 μM antibiofilm compound-treated PAO1 and monitored for increased survival. Kaplan-Meier curves were determined from three independent experiments (n = 30), where the total number of worms equals 90. Significant differences in nematode survival are indicated: **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

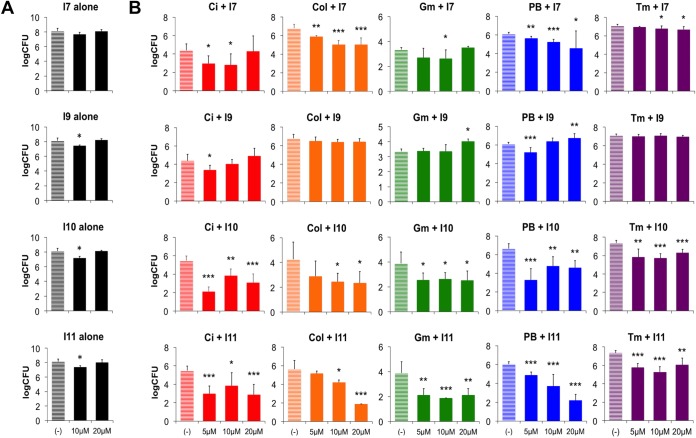

Antibiofilm compounds promote antibiotic killing against PAO1 biofilms.

Since biofilms are more antibiotic tolerant than planktonic cells, new treatments are needed that can both reduce biofilm and increase antibiotic susceptibility (24). Peg-adhered PAO1 biofilms were cultivated in the absence or presence of our lead antibiofilm compounds for 24 h and then challenged with a panel of 5 different antimicrobials that target P. aeruginosa growth by different mechanisms of action. Polymyxins (colistin [Col] and polymyxin B [PB]) disrupt membrane integrity, aminoglycosides (tobramycin [Tm] and gentamicin [Gm]) inhibit protein synthesis, and fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin [Ci]) block DNA replication. It is noteworthy to acknowledge that Col and Tm are two clinically important antimicrobial therapies used to treat P. aeruginosa infections in CF patients (41, 42).

There was a marginal effect on surviving bacterial counts from biofilms treated with antibiofilm compounds alone, with a maximum 1-log decrease in CFU per peg (Fig. 8A). We selected the four compounds that strongly reduced EPS and biomass production (Fig. 3) and had antivirulence activities (Fig. 7). Next, biofilms were cultivated in increasing concentrations of antibiofilm compounds and then challenged with sub-biofilm eradication concentrations of the antimicrobials. Compounds I7, I10, and I11 increased the PAO1 biofilm susceptibility to all tested antimicrobials by reducing the viable cell counts between 10- and 10,000-fold (Fig. 8B). Compound I9 only increased biofilm susceptibility to Ci and PB, and compound I11 often caused a dose-dependent effect on increasing biofilm killing as the concentration of antibiofilm compound increased from 5 to 20 μM (Fig. 8B). In addition to their antibiofilm and antivirulence properties, these small molecules are also effective in promoting antibiotic killing of biofilms when in combination with antibiotics. The antibiofilm-treated biofilms may result in improved antibiotic access and killing.

FIG 8.

Antibiotics have improved biofilm killing when used in combination with antibiofilm compounds. (A) The effect on bacterial counts of treating microplate biofilm with antibiofilm compounds I7, I9, I10, and I11. (B) Biofilms were formed in the absence or presence of antibiofilm compounds I7, I9, I10, and I11 (5 to 20 μM) and then treated with suberadication concentrations of the antibiotics ciprofloxacin (Ci; 2.5 μg/ml), colistin (Col; 25 μg/ml), gentamicin (Gm; 6.5 μg/ml), polymyxin B (PB; 25 μg/ml), or tobramycin (Tm; 1 μg/ml). Surviving bacterial counts (CFU per peg) were determined from peg-adhered biofilms after single-antibiotic treatment or after combination treatment. The values shown are the means from triplicate samples plus standard deviations (n = 3). Significant differences in viable cell counts are indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

We describe the P. aeruginosa EPS biosynthesis genes as a new target for the identification of antibiofilm compounds. Biofilm formation is an important focus for new antimicrobials given the universal and conserved process of forming a biofilm and the diverse protective advantages of cells enmeshed in an extracellular matrix. While other studies have used simple screens for compounds that reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm formation with little insight toward their mechanism (23), here we identified compounds that repress the expression of the pel genes in P. aeruginosa and confirmed our hypothesis by demonstrating that treatment with pel repressors resulted in biofilm-defective phenotypes. The best compounds reduced biofilms by 50 to 70%, which is comparable to many previously reported antibiofilm compounds for P. aeruginosa (22, 23, 43). Since P. aeruginosa uses multiple matrix polymers (Pel, Psl, and eDNA) and adhesins (type IV pili, flagellum, among others) to attach and build a biofilm, compounds that repress EPS production will likely not be capable of complete biofilm repression.

Next we illustrated that EPS production is required for P. aeruginosa virulence in the nematode infection model (Fig. 6) and identified 4 pel repressors that reduced the virulence of PAO1 in the slow killing infection model for C. elegans (Fig. 7). In agreement with these findings, a previous report has shown that mutations in the pel and psl EPS-encoding genes reduced the ability of P. aeruginosa to colonize the gastrointestinal tract of mice and to disseminate (44). While numerous high-throughput nematode virulence screens have been performed in PA14, a rapid killing strain of P. aeruginosa, to our knowledge this is the first report to identify EPS as a virulence factor in C. elegans. By reducing EPS synthesis and biofilm formation (Fig. 3), the antibiofilm molecules also promoted antibiotic killing when combined with antibiotic treatments (Fig. 8). The improved bactericidal effects were seen across multiple antibiotic classes, including antibiotics known to have reduced effectiveness because of the production of Pel or Psl EPS (8, 16, 18). Although these treatments significantly reduced PAO1 virulence in vivo and also promote biofilm killing in association with antibiotics, further studies are needed to show if their antivirulence properties are specifically due to repression of EPS production.

Pel repressors were classified as antibiofilm compounds if they were capable of reducing biofilms in at least 2 out of the 3 aerobic biofilm phenotypes, which included EPS production, microplate biofilms, and flow chamber biofilms (Table 1). We ultimately grouped the pel repressors into 3 categories based on their antibiofilm and antivirulence effects (Table 1). Among the seven antibiofilm compounds identified (I2, I7, I9, I10, I11, I12, and I13), only four compounds were also found to have antivirulence activity in the C. elegans slow killing assay (Table 1, Fig. 7). None of the pel repressors identified here reduce the growth of P. aeruginosa at concentrations as high as 100 μM, which was 10 times the concentration used for all experiments (data not shown). Of the four lead compounds I7, I9, I10, and I11, only I9, the natural product brazilin, possesses antibacterial activity against the unrelated bacterium Propionibacterium acnes (45). Compound I10 (acetylcholine) was recently reported to have antibiofilm and antivirulence activity against Candida albicans (46), and several choline analogs were reported to reduce biofilm activity in P. aeruginosa without inhibiting growth (43). The identification of acetylcholine in this study, a known antibiofilm compound, validates the screening approach used. The antibiofilm compounds I2 and I13 have structural similarities and share a benzothiazole component (Fig. 2). There were 5 of 13 compounds tested that reduced pel expression but did not have strong antibiofilm activity under aerobic conditions (Table 1). It is possible that these compounds are false positives; however, it is interesting to note that three compounds from this group had antibiofilm effects against anaerobic biofilms (Table 1, Fig. 5A). Among the pel repressors that didn't reduce aerobic biofilm formation, I5 and I6 share a benzothiophene backbone.

We speculate that these antibiofilm compounds might be acting on one of the many regulatory components of the intricate signaling network that controls the expression and production of Pel and Psl. The GacAS two-component system is best studied for its association with the rsmY and rsmZ regulatory RNAs, which in turn regulate the pel/psl mRNA stability by RsmA and ultimately the production of EPS (47–49). In addition, the GacAS pathway can be repressed or activated by the additional orphan sensors RetS and LadS, respectively (30, 50). We previously reported that the PhoPQ two-component system directly repressed the retS sensor, leading to a robust biofilm phenotype under the PhoPQ-inducing conditions of growth in limiting magnesium (5). The hybrid sensor kinase PA1611, the membrane-associated diguanylate cyclase SadC, and the histidine phosphotransfer protein HptB all integrate into the GacAS pathway to influence the transition from an acute to chronic lifestyle (51–53). Other transcriptional regulators include the psl activator RpoS (49) and the pel repressor/activator FleQ (54). RetS was originally described as a transcriptional repressor of pel and psl by microarray analysis (30), although the mechanism of RetS transcriptional control of pel/psl is not understood, given the lack of a known cognate response regulator. Given the large number of potential protein targets known to regulate EPS production through the GacAS pathway, further work is needed to identify the specific antibiofilm target and to elucidate a defined mechanism of action for the identified molecules.

Antivirulence compounds have been described for P. aeruginosa that target the quorum-sensing Las, Rhl, and Pqs systems (55, 56). This work supports the hypothesis that the pel and psl EPS biosynthesis genes provide a new target for antivirulence drug development. Developing drugs to reduce EPS production may be a more effective strategy than targeting the numerous protein adhesins, especially considering the protective roles of EPS against antibiotics and the immune system (16, 18, 19). Future work is needed to understand their mechanism of action and their effectiveness in other infection models and to assess their potential for therapeutic use to treat chronic biofilm infections by P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Biofilms and planktonic cultures were grown in basal minimal medium (BM2) at 37°C, containing excess or limiting Mg2+ concentrations. BM2 medium was prepared with 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 7 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.03 mM K2HPO4, 0.57 mM KH2PO4, 20 μM or 2 mM MgSO4, 10 μM FeSO4, and ion solution, containing 1.6 mM MnSO4·H2O, 14 mM ZnCl2, 4.7 mM H3BO3 and 0.7 mM CoCl2·6H2O. The medium was supplemented with 20 mM sodium succinate as a carbon source for all assays. KNO3 (1%) was added to support bacterial growth under anaerobic conditions. GFP-tagged PA14 was prepared as previously described (57). Briefly, the pBT270 GFP-encoding plasmid containing a site-specific integration mini-Tn7 vector was transformed in PA14 with the help of a pTNS2 plasmid. GFP-expressing colonies were selected for with Gm resistance (50 μg/ml). Stock solutions of ampicillin (50 mg/ml; Amresco), Ci (2 mg/ml; BioChemika), Col (10 mg/ml; Sigma), Gm (30 mg/ml; Sigma), PB (30 mg/ml; Sigma), and Tm (25 mg/ml; Sigma) were made in ultrapure water, stored at −20°C, and used as indicated.

HTS and gene expression assays.

The 31,096 small molecules in the Canadian Chemical Biology Network (CCBN) library were transferred from the stock 96-well plates (1 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide) to 384-well assay microplates using plastic 96-pin transfer devices. All compounds were tested at a final concentration of ∼10 μM. Plates were covered with an air-permeable membrane and incubated at 37°C for 14 h, and gene expression in counts per second was determined in a Wallac Victor3 luminescent plate reader (Perkin-Elmer). For the secondary screen, pelB::lux and pslA-lux reporters were grown in 384-well microplates in the presence of an ∼10 μM concentration of the hit compounds at 37°C in a Wallac Victor3 plate reader, reads of the counts per second and optical density at 600 nm (OD600) (growth) were taken every 60 min throughout growth, and the total gene expression was reported as the area under the curve. For all other gene expression assays, gene reporters were grown in 96-well microplates, in the presence of a 10 μM concentration of the reordered inhibitor compounds, and incubated at 37°C in a Wallac Victor3 reader with measurements of counts per second and OD600 taken every 20 min.

EPS quantification.

EPS was measured in the quantitative Congo red (CR) binding assay, as previously described (28). Cultures were grown in BM2 with 20 μM Mg2+ containing a 10 μM concentration of the reordered compounds in 5-ml glass tubes for 24 h at 37°C with shaking (150 rpm). For EPS quantification, CR was added at a final concentration of 40 μg/ml to 2-ml cultures and bound dye was indirectly calculated by determination of remaining unbound dye still in solution (28).

Biofilm cultivation and quantification.

Unless otherwise indicated, all biofilms were cultivated in BM2 with 20 μM Mg2+ containing 10 μM compounds in 96-well polystyrene microplates for 18 h at 37°C with shaking (100 rpm). Anaerobic biofilms were cultivated inside an anaerobic chamber (GasPack system) for 48 h. Biofilm inhibition was determined by crystal violet (CV) staining as previously described (29). Continuous flow biofilms were cultivated in the BioFlux device in 48-well microplates incubated for 18 h at 37°C (31). The biofilms that formed under the flow system were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted epifluorescence microscope in green fluorescence and phase contrast. Biofilm depth and coverage were determined using ImageJ processing and analysis in Java.

C. elegans nematode infection models.

The nematode feeding preference and slow killing assays were performed as previously described (39). Briefly, L4-stage hermaphrodite nematodes were transferred to a slow killing assay plate containing a pregrown grid of 45 wild-type colonies and 3 internal spots of the mutant strains to be tested (6 by 8 colonies). The plates were incubated at 25°C and observed twice a day until the disappearance of the initial bacterial colonies. Slow killing assays were performed as previously described (39, 40). All compounds were added at 10 μM in the slow killing agar (SK agar) before bacterial growth. For both in vivo assays, E. coli strain OP50 was used as a positive control to demonstrate preferred feeding behavior and reduced virulence for the nematodes.

Antimicrobial killing of biofilms.

Biofilm susceptibility testing was performed as previously described (58), with minor modifications. Biofilms were grown for 24 h on polystyrene pegs (Nunc-TSP) submerged in BM2 with 20 μM Mg2+ containing 0, 5, 10, or 20 μM select inhibitor compounds. Cultivated biofilms were rinsed twice in 0.9% saline (NaCl) and transferred to a plate containing suberadication concentrations of antimicrobials in 10% BM2 diluted in 0.9% saline and challenged for 24 h. After challenge, biofilms were rinsed in 0.9% saline, and cells were detached with DNase I (25 μg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min and 10 min of sonication. Cell viability was determined by serial dilution and direct counting as previously described.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance between populations was determined by paired two-tailed Student's t test. The log-rank test (Graph Pad Prism) was used for determination of significant differences in C. elegans survival. Data were considered significant at P < 0.05. Significance is represented by asterisks in the various figure legends: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank George Chaconas for providing the CCBN drug library, Elaine Goth-Birkigt for technical assistance with the BioFlux device, and Joe Harrison for providing the plasmids for PA14-gfp construction. We also thank Joe McPhee, Tao Dong, and Mike Wilton for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work, including the efforts of Erik van Tilburg Bernardes, Laetita Charron-Mazenod, and David J. Reading, was funded by an NSERC Discovery Grant. E.V.T.B. was additionally supported by the Beverly Phillips Rising Star and Cystic Fibrosis Canada Studentships, and S.L. held the Westaim-ASRA Chair in Biofilm Research. The funders did not participate in the design of the study, the data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01997-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colvin KM, Irie Y, Tart CS, Urbano R, Whitney JC, Ryder C, Howell PL, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2012. The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ Microbiol 14:1913–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirisits MJ, Prost L, Starkey M, Parsek MR. 2005. Characterization of colony morphology variants isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4809–4821. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4809-4821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Høiby N. 2006. P. aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients resists host defenses, antibiotics. Microbe 1:571–577. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulcahy H, Lewenza S. 2011. Magnesium limitation is an environmental trigger of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm lifestyle. PLoS One 6:e23307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma L, Conover M, Lu H, Parsek MR, Bayles K, Wozniak DJ. 2009. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000354. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryder C, Byrd M, Wozniak DJ. 2007. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr Opin Microbiol 10:644–648. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Hu Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Ulstrup J, Molin S. 2011. Distinct roles of extracellular polymeric substances in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Environ Microbiol 13:1705–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin MJ, Nivens DE, Weadge JT, Howell PL. 2011. Biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa extracellular polysaccharides, alginate, Pel, and Psl. Front Microbiol 2:167. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman L, Kolter R. 2004. Two genetic loci produce distinct carbohydrate-rich structural components of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. J Bacteriol 186:4457–4465. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4457-4465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wozniak DJ, Wyckoff TJ, Starkey M, Keyser R, Azadi P, O'Toole GA, Parsek MR. 2003. Alginate is not a significant component of the extracellular polysaccharide matrix of PA14 and PAO1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:7907–7912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231792100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govan JR, Deretic V. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev 60:539–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starkey M, Hickman JH, Ma L, Zhang N, De Long S, Hinz A, Palacios S, Manoil C, Kirisits MJ, Starner TD, Wozniak DJ, Harwood CS, Parsek MR. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rugose small colony variants have adaptations likely to promote persistence in the cystic fibrosis lung. J Bacteriol 191:3492–3503. doi: 10.1128/JB.00119-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings LK, Storek KM, Ledvina HE, Coulon C, Marmont LS, Sadovskaya I, Secor PR, Tseng BS, Scian M, Filloux A, Wozniak DJ, Howell PL, Parsek MR. 2015. Pel is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11353–11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503058112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrd MS, Sadovskaya I, Vinogradov E, Lu H, Sprinkle AB, Richardson SH, Ma L, Ralston B, Parsek MR, Anderson EM, Lam JS, Wozniak DJ. 2009. Genetic and biochemical analyses of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Psl exopolysaccharide reveal overlapping roles for polysaccharide synthesis enzymes in Psl and LPS production. Mol Microbiol 73:622–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colvin KM, Gordon VD, Murakami K, Borlee BR, Wozniak DJ, Wong GC, Parsek MR. 2011. The Pel polysaccharide can serve a structural and protective role in the biofilm matrix of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulcahy H, Sibley CD, Surette MG, Lewenza S. 2011. Drosophila melanogaster as an animal model for the study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infections in vivo. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002299. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billings N, Ramirez Millan M, Caldara M, Rusconi R, Tarasova Y, Stocker R, Ribbeck K. 2013. The extracellular matrix component Psl provides fast-acting antibiotic defense in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003526. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra M, Byrd MS, Sergeant S, Azad AK, Parsek MR, McPhail L, Schlesinger LS, Wozniak DJ. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Psl polysaccharide reduces neutrophil phagocytosis and the oxidative response by limiting complement-mediated opsonization. Cell Microbiol 14:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragos A, Kovacs AT. 11 January 2017. The peculiar functions of the bacterial extracellular matrix. Trends Microbiol doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies JC, Bilton D. 2009. Bugs, biofilms, and resistance in cystic fibrosis. Respir Care 54:628–640. doi: 10.4187/aarc0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junker LM, Clardy J. 2007. High-throughput screens for small-molecule inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3582–3590. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenderska IB, Chong M, McNulty J, Wright GD, Burrows LL. 2011. Palmitoyl-dl-carnitine is a multitarget inhibitor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Chembiochem 12:2759–2766. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernardes EVT, Lewenza S, Reckseidler-Zenteno SL. 2015. Current research approaches to target biofilm infections. PostDoc J 3:36–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antoniani D, Bocci P, Maciag A, Raffaelli N, Landini P. 2010. Monitoring of diguanylate cyclase activity and of cyclic-di-GMP biosynthesis by whole-cell assays suitable for high-throughput screening of biofilm inhibitors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:1095–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peach KC, Bray WM, Shikuma NJ, Gassner NC, Lokey RS, Yildiz FH, Linington RG. 2011. An image-based 384-well high-throughput screening method for the discovery of biofilm inhibitors in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Biosyst 7:1176–1184. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00276c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duan K, Dammel C, Stein J, Rabin H, Surette MG. 2003. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression by host microflora through interspecies communication. Mol Microbiol 50:1477–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen JS, Lin YC, Squyres GR, Price-Whelan A, de Santiago Torio A, Song A, Cornell WC, Sorensen SJ, Xavier JB, Dietrich LE. 2015. Facultative control of matrix production optimizes competitive fitness in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilm models. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:8414–8426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02628-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman AL, Kulasekara B, Rietsch A, Boyd D, Smith RS, Lory S. 2004. A signalling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev Cell 7:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benoit MR, Conant CG, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Schwartz M, Matin A. 2010. New device for high-throughput viability screening of flow biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4136–4142. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03065-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirisits MJ, Margolis JJ, Purevdorj-Gage BL, Vaughan B, Chopp DL, Stoodley P, Parsek MR. 2007. Influence of the hydrodynamic environment on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol 189:8357–8360. doi: 10.1128/JB.01040-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worlitzsch D, Tarran R, Ulrich M, Schwab U, Cekici A, Meyer KC, Birrer P, Bellon G, Berger J, Weiss T, Botzenhart K, Yankaskas JR, Randell S, Boucher RC, Doring G. 2002. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Invest 109:317–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI0213870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam J, Chan R, Lam K, Costerton JW. 1980. Production of mucoid microcolonies by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within infected lungs in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 28:546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Rojas A, Oliver A, Blazquez J. 2012. Intrinsic and environmental mutagenesis drive diversification and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic lung infections. J Infect Dis 205:121–127. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L, Hengzhuang W, Wu H, Damkiaer S, Jochumsen N, Song Z, Givskov M, Hoiby N, Molin S. 2012. Polysaccharides serve as scaffold of biofilms formed by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 65:366–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathee K, Ciofu O, Sternberg C, Lindum PW, Campbell JI, Jensen P, Johnsen AH, Givskov M, Ohman DE, Molin S, Hoiby N, Kharazmi A. 1999. Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology 145:1349–1357. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irazoqui JE, Troemel ER, Feinbaum RL, Luhachack LG, Cezairliyan BO, Ausubel FM. 2010. Distinct pathogenesis and host responses during infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewenza S, Charron-Mazenod L, Giroux L, Zamponi AD. 2014. Feeding behaviour of Caenorhabditis elegans is an indicator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 virulence. PeerJ 2:e521. doi: 10.7717/peerj.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell JR, Ausubel FM. 2008. Models of Caenorhabditis elegans infection by bacterial and fungal pathogens. Methods Mol Biol 415:403–427. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-570-1_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodson ME, Gallagher CG, Govan JR. 2002. A randomised clinical trial of nebulised tobramycin or colistin in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 20:658–664. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00248102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulin T. 2002. In vitro activity of the aerosolized agents colistin and tobramycin and five intravenous agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients in southwestern Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother 49:403–406. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mi L, Licina GA, Jiang S. 2014. Nonantibiotic-based Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm inhibition with osmoprotectant analogues. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2:2448–2453. doi: 10.1021/sc500468a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skurnik D, Roux D, Aschard H, Cattoir V, Yoder-Himes D, Lory S, Pier GB. 2013. A comprehensive analysis of in vitro and in vivo genetic fitness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using high-throughput sequencing of transposon libraries. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003582. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batubara I, Mitsunaga T, Ohashi HJ. 2010. Brazilin from Caesalpinia sappan wood as an antiacne agent. J Wood Sci 56:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s10086-009-1046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajendran R, Borghi E, Falleni M, Perdoni F, Tosi D, Lappin DF, O'Donnell L, Greetham D, Ramage G, Nile C. 2015. Acetylcholine protects against Candida albicans infection by inhibiting biofilm formation and promoting hemocyte function in a Galleria mellonella infection model. Eukaryot Cell 14:834–844. doi: 10.1128/EC.00067-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gooderham WJ, Hancock RE. 2009. Regulation of virulence and antibiotic resistance by two-component regulatory systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33:279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gooderham WJ, Gellatly SL, Sanschagrin F, McPhee JB, Bains M, Cosseau C, Levesque RC, Hancock RE. 2009. The sensor kinase PhoQ mediates virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 155:699–711. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irie Y, Starkey M, Edwards AN, Wozniak DJ, Romeo T, Parsek MR. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix polysaccharide Psl is regulated transcriptionally by RpoS and post-transcriptionally by RsmA. Mol Microbiol 78:158–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ventre I, Goodman AL, Vallet-Gely I, Vasseur P, Soscia C, Molin S, Bleves S, Lazdunski A, Lory S, Filloux A. 2006. Multiple sensors control reciprocal expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulatory RNA and virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:171–176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507407103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kong W, Chen L, Zhao J, Shen T, Surette MG, Shen L, Duan K. 2013. Hybrid sensor kinase PA1611 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulates transitions between acute and chronic infection through direct interaction with RetS. Mol Microbiol 88:784–797. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moscoso JA, Jaeger T, Valentini M, Hui K, Jenal U, Filloux A. 2014. The diguanylate cyclase SadC is a central player in Gac/Rsm-mediated biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 196:4081–4088. doi: 10.1128/JB.01850-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bordi C, Lamy MC, Ventre I, Termine E, Hachani A, Fillet S, Roche B, Bleves S, Mejean V, Lazdunski A, Filloux A. 2010. Regulatory RNAs and the HptB/RetS signalling pathways fine-tune Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 76:1427–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baraquet C, Murakami K, Parsek MR, Harwood CS. 2012. The FleQ protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa functions as both a repressor and an activator to control gene expression from the pel operon promoter in response to c-di-GMP. Nucleic Acids Res 40:7207–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reuter K, Steinbach A, Helms V. 2016. Interfering with bacterial quorum sensing. Perspect Medicin Chem 8:1–15. doi: 10.4137/PMC.S13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Starkey M, Lepine F, Maura D, Bandyopadhaya A, Lesic B, He J, Kitao T, Righi V, Milot S, Tzika A, Rahme L. 2014. Identification of anti-virulence compounds that disrupt quorum-sensing regulated acute and persistent pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004321. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi KH, Schweizer HP. 2006. Mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Protoc 1:153–161. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrison JJ, Turner RJ, Joo DA, Stan MA, Chan CS, Allan ND, Vrionis HA, Olson ME, Ceri H. 2008. Copper and quaternary ammonium cations exert synergistic bactericidal and antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2870–2881. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00203-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.