Abstract

Built environment (BE) data in geographic information system (GIS) format are increasingly available from public agencies and private providers. These data can provide objective, low-cost BE data over large regions and are often used in public health research and surveillance. Yet challenges exist in repurposing GIS data for health research. The GIS data do not always capture desired constructs; the data can be of varying quality and completeness; and the data definitions, structures, and spatial representations are often inconsistent across sources.

Using the Small Town Walkability study as an illustration, we describe (a) the range of BE characteristics measurable in a GIS that may be associated with active living, (b) the availability of these data across nine U.S. small towns, (c) inconsistencies in the GIS BE data that were available, and (d) strategies for developing accurate, complete, and consistent GIS BE data appropriate for research.

Based on a conceptual framework and existing literature, objectively measurable characteristics of the BE potentially related to active living were classified under nine domains: generalized land uses, morphology, density, destinations, transportation system, traffic conditions, neighborhood behavioral conditions, economic environment, and regional location. At least some secondary GIS data were available across all nine towns for seven of the nine BE domains. Data representing high-resolution or behavioral aspects of the BE were often not available. Available GIS BE data - especially tax parcel data - often contained varying attributes and levels of detail across sources. When GIS BE data were available from multiple sources, the accuracy, completeness, and consistency of the data could be reasonable ensured for use in research. But this required careful attention to the definition and spatial representation of the BE characteristic of interest. Manipulation of the secondary source data was often required, which was facilitated through protocols.

Keywords: active travel, pedestrian, neighborhood, urban design, community health, rural

1. Introduction

A growing body of research has linked the home neighborhood built environment (BE) with physical activity (PA), with the strongest associations observed for PA obtained through walking for transportation (Durand et al., 2011; McCormack and Shiell, 2011; Saelens and Handy, 2008). This research has been translated into best practices for urban design (Evenson et al., 2012; Frank and Kavage, 2009; NYC, 2010)and Health Impact Assessments (de Nazelle et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013) intended to result in more active, healthier communities. As these efforts expand, researchers, planners, and policy makers would benefit from guidance for adapting readily available geographic information system (GIS) data to measure the BE as it relates to walking and other forms of active transportation. This article provides such guidance using the small town walkability (STW) study as an example.

The STW study identified BE correlates of home neighborhood walking in nine small towns (population 10,000-50,000) serving as the population centers of rural areas (Doescher et al., 2014). Three towns were each located in the Northeast (New Hampshire and New York), Texas, and Washington State. The study used GIS measures of the BE developed from secondary sources, which resulted in a broad perspective on the availability and challenges of adapting secondary GIS BE data for health research. GIS BE data are preferred because they more accurately represent existing conditions than self-report surveys, which are subject to recall and social desirability bias. GIS data often exist for large geographic areas and require fewer resources to collect compared to in-person audits (Brownson et al., 2009; Thornton et al., 2011). GIS data are increasingly available from local jurisdictions, state and national government agencies, and private providers. Yet challenges remain in using these secondary data for health research: the data are typically created for other purposes and do not always capture desired constructs; the data can be of varying quality and completeness; and the data definitions, structures, and spatial representations are often inconsistent across sources, precluding accurate comparisons (Brownson et al., 2009; Forsyth et al., 2006).

In this article we first describe the conceptual framework and study objectives that guided our GIS data collection efforts and list the BE characteristics we sought to collect. For each BE characteristic, we then identify if existing data were available and if so, which sources were used. We present a clear operational definition of each BE characteristic measured, along with the processing method used to standardize the source data for completeness, consistency, and accuracy. Finally, we briefly describe protocols used to coordinate this effort across study sites. We do not detail how variables were constructed from the GIS data, as this extensive subject that has been discussed elsewhere [for example, (Berrigan et al., 2010; James et al., 2014)]. In addition to guiding those undertaking similar multi-jurisdiction BE GIS data development efforts, this article is intended to provide transparency to aid interpretation of the STW study results and replication of its methods (Brownson et al., 2009; Mackenbach et al., 2014).

2. Methods

The STW study used a cross-sectional design to examine correlates of utilitarian walking (i.e., walking for transportation) and recreational walking (i.e., walking for leisure) in home neighborhoods among adults living in small, rural towns. During 2011 and 2012 a telephone survey was conducted to ascertain home-based walking behaviors, home neighborhood perceptions, and socio-demographics from 2,152 residents aged 18 and older in the nine small towns (217 to 303 per town). Participants’ home locations were geocoded, and standardized GIS BE data were developed, from which objective BE variables were measured for each respondent’s home neighborhood. Details of the overall study are available elsewhere (Doescher et al., 2014).

2.1 Conceptual framework

The relationship between BE and health-related behaviors such as walking is complex (Carlson et al., 2012). The Behavioral Model of the Environment (BME) (Moudon and Lee, 2003) describes four interactive relationships of the BE:

Spatiophysical,

Spatiobehavioral,

Spatiopsychosocial, and

Policy.

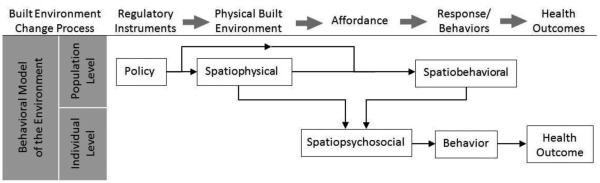

The first two respectively represent the physical form of the BE and the human activity that takes place within it. The third is a function of how an individual perceives and interprets these characteristics. The fourth represents the mechanism through which the first two may be altered. The Built Environment Change (BEC) framework (Berke and Moudon, 2014) implicitly structures these relationships as a process through which the BE influences health, which can be used to identify pathways between the built environment and health (Figure 1). In the BEC framework, policy guides the development of regulatory instruments that control the built environment, including its physical form (spatiophysical) and the allowed uses (spatiobehavioral). Based on the physical form and allowed uses, the built environment then affords certain human behaviors or responses. At the aggregate population level, these responses can be seen as spatiobehavioral characteristics, which are then observed by an individual and, together with the spatiophysical characteristics, interpreted as subjective constructs, such as comfort or safety (spatiopsychosocial characteristics). These spatiopsychosocial characteristics influence how individuals interact with the BE, which finally results in individual behaviors that impact health or disease.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of pathways between the built environment and health, adapted from the Built Environment Change (BEC) framework (Berke and Moudon, 2014) and the Behavioral Model of the Environment (BME) (Moudon and Lee, 2003).

Our BE data collection focused on observable and objectively measurable BE characteristics with a hypothesized effect on the health-related behavior of neighborhood walking. Thus we focused on identifying spatiophysical and spatiobehavioral characteristics of the BE likely related to walking in small, rural towns based on current literature and theoretical importance.

2.2 BE characteristic identification and organization

Spatiophysical and spatiobehavioral BE characteristics were organized under nine domains (Table 1). Generalized land uses define neighborhood composition (Diez Roux, 2001; Frank et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2009) through the social and economic activity contained in the BE’s form. Morphology is the physical shape of the BE, particularly buildings and ancillary characteristics of the parcel, but also including natural environment elements such as topography and water (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Frank et al., 2010; Rapoport, 1990, 1991; Saelens et al., 2012). Density characterizes the intensity of human activity that corresponds to a primary land use. For example, residential and employment densities correspond to the number of people living or working, respectively, per area of land designated for these uses. Density is used in travel research because it is correlated with land use mix (availability of destinations near residences), transportation systems, and traffic conditions (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Ewing, 1995; Frank et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2009). Destinations are specific travel “attractors” that may also act as environmental stimuli. They offer opportunities for activities such as shopping and socializing while also affecting sights, sounds, smells, and general environmental cognition (Cerin et al., 2007; McCormack et al., 2008; Moudon et al., 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2009). Transportation system describes the physical form of the transportation network, whereas traffic conditions describe the activity that occurs on the transportation network. Both influence accessibility and movement through the neighborhood (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Frank et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2005). Neighborhood behavioral conditions have been identified in the sociology literature as evidence of positive or negative human actions observable in the public realm (e.g., panhandling, broken windows) (Foster et al., 2010). Economic environment variables capture the wealth and value of the built and natural environment (Krieger et al., 1997). Finally, regional location corresponds to regional activity nodes, can also which effect neighborhood behavior. Proximity to Central Business Districts (CBD) is particularly influential on travel behavior (Ewing, 1995).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the home neighborhood built environment (BE) that are objectively measurable and theoretically or empirically related to walking. BE characteristics are listed in the third column and are organized by domains in the first two columns. The fourth column identifies how pedestrians interact with BE characteristic based on the Behavioral Model of the Environment (BME). The fifth column summarizes the theoretical or empirical relationship with walking. The final three columns describe the BE characteristics collected for the Small Town Walkability (STW), their source, and their geospatial representation in a GIS.

| Domain | Sub- domain |

BE characteristic (s) |

BME characteristi c(s) |

Relationship with walking (selected references) |

BE characteristi c(s) collected in STW study |

Data source for STW study |

Geospatial representa tion for STW study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalize d land use |

Common land use classificati ons |

Residential, institutional, retail, service, office, etc. |

Spatiobehavi oral |

A variety of land uses represent destinations that support walking (Cerin et al., 2007; Duncan et al., 2010; Eriksson et al., 2012; Rodriguez et al., 2009) |

Residential (single, multifamily) ; manufacturi ng; cultural, entertainme nt, and recreational ; resource production and extraction; transportati on, communicat ion, and utilities; retail; services and office; undevelope d land and water areas |

Local governme nt agencies, including planning departme nt, GIS departme nt, or tax assessor |

Parcel polygons |

| Locally Unwanted Land Uses (LULUs) |

Prisons, wastewater treatment plants, etc. |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Undesirable land uses inhibit walking |

LULUs present in study towns |

Local governme nt , online searches and aerial imagery |

Polygons digitized based on secondary sources |

|

| Morpholog y |

Building characteris tics |

Architectural style, floor area ratio, square footage, setback from street |

Spatiophysic al |

Visual interest and “human- scaled” designs support walking (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Frank et al., 2010; Rapoport, 1991; Saelens et al., 2012) |

None | n/a | n/a |

| Lot (parcel) |

Square footage, yard area, impervious surface, border (fence, shrubs), vacant, residential density |

Spatiophysic al |

Less space at home results in neighborho od walking; underdevelo ped lots provide shortcuts for walking but also result in less visual interest and possible safety concerns that may deter walking (Lee and Moudon, 2006; Moudon et al., 2007; Wang and Lee, 2010) |

Parcel location |

Local governme nt |

Parcel polygons |

|

| Building- street relationshi p |

Doors and windows facing street, alley access, corner lot |

Spatiophysic al |

Buildings that “interact” with street support walking (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Rapoport, 1991) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Natural environme nt |

Slope, land cover, waterways |

Spatiophysic al |

Steep slopes make walking difficult but also provide views, foliage supports walking in hot climates (Cerin et al., 2008; Lee and Moudon, 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Tilt et al., 2007) |

Slope | USGS | Raster | |

| Density | Dwelling | Residential units, population |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Greater densities provide more destinations and activities that support walking and increase demand (Eriksson et al., 2012; Li et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2009) |

Residential unit counts (single, multifamily) |

Local governme nt |

Parcel polygons |

| Work | Employment square footage, jobs |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Major employers (>=100 employees) |

OneSourc e business listings |

Addresses geocoded to parcel polygons |

||

| Destinatio ns |

Restaurant | Fast food, coffee shop, etc. |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Proximal destinations provide places to walk to or walk at, as well as stimulus (positive or negative) while walking (Lee and Moudon, 2006; McCormack et al., 2008; Moudon et al., 2007; Tilt et al., 2007; Wang and Lee, 2010) |

Ethnic, traditional, fast food, ethnic quick service, quick service, snacks and non- alcoholic beverages, coffee shop, dessert, bar/tavern/ pub, pizza place |

OneSourc e business listings |

Addresses geocoded to Parcel polygons |

| Food store | Supermarket, convenience store, etc. |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Supermarke t, warehouse, grocery store, ethnic market, specialty food store, convenienc e store |

OneSourc e business listings |

Addresses geocoded to parcel polygons |

||

| Entertainm ent |

Bowling alley, theater, etc. |

Spatiobehavi oral |

None | n/a | n/a | ||

| Retail | drugstore, video store, mall |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Drugstore, video store, mall |

OneSourc e business listings, Local governme nt, online searches, and aerial imagery |

Addresses geocoded to parcel polygons, polygons digitized based on secondary sources |

||

| Services | post office, bank, healthcare, drycleaner |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Post office, bank |

OneSourc e business listings |

Addresses geocoded to parcels |

||

| Education and communit y |

religious institution, school, day care |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Religious institution, school, day care |

OneSourc e business listings, National Center for Education Statistics, Local school districts, |

Addresses geocoded to parcel polygons, polygons digitized based on secondary sources |

||

| Outdoor and recreation al facilities |

park, fitness center/ recreation facility |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Park, trail, fitness center/ recreation facility |

OneSourc e business listings, local parks departme nts, online searches, and aerial imagery |

Addresses geocoded to parcel polygons, polygons or polylines digitized based on secondary sources |

||

| Neighborh ood center |

Agglomeratio ns of restaurant, retail, and other destinations |

Spatiobehavi oral |

None | n/a | n/a | ||

| Transporta tion system |

Street system |

Network, intersections, lanes, on- street parking, sidewalks, street lighting, street furniture, street trees, crosswalks, traffic signals |

Spatiophysic al |

A greater variety of routes, pedestrian infrastructur e, and traffic control support walking (Berrigan et al., 2010; Jago et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2013; Wang and Lee, 2010) |

Full street network, pedestrian- accessible street network, sidewalks, speed classificatio n, functional classificatio n, intersection s |

ESRI StreetMa p USA Premium, aerial imagery |

Polylines and points coded based on secondary sources |

| Public transit |

Bus stops, transit stations |

Spatiophysic al |

Transit supports walking by extending range accessible without a private auto (Saelens et al., 2014) |

Local and intercity transit stops |

ESRI StreetMa p USA Premium, local transit agency |

Points digitized based on secondary sources |

|

| Traffic conditions |

Street system |

Vehicular volume, collisions, mode split, traffic noise |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Streets with fewer motorized vehicles are more desirable for walking (McGinn et al., 2007) |

None | n/a | n/a |

| Non- motorized |

Pedestrian volumes |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Streets with more pedestrians are more desirable for walking (Sallis et al., 2007) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Public transit |

Transit service, transit ridership |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Greater transit service represents greater extension of pedestrian travel range (Moudon et al., 2007) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Neighborh ood behavioral conditions |

Human activity |

People being physically active, loitering, panhandling |

Spatiobehavi oral |

More people in an area engaged in non- threatening behaviors support walking (Lovasi et al., 2013; Sallis et al., 2007) |

None | n/a | n/a |

| Maintenan ce |

Abandoned vehicles, building conditions, landscaping, seasonal decorations |

Spatiophysic al |

Signs of maintenanc e contribute to sense of safety and support walking (Foster et al., 2010) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Protective measures |

Beware of dog signs, neighborhoo d crime watch signs, no trespassing signs, security signs |

Spatiophysic al |

Protective behaviors represent reaction to crime and thus reduced safety, which inhibits walking (Foster and Giles-Corti, 2008) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Social incivilities |

Crime, dogs barking, unattended dogs, drug/alcohol paraphernali a, noisy neighbors, graffiti/vanda lism |

Spatiobehavi oral and Spatiophysic al |

Incivilities are perceived as threats to personal safety and inhibit walking (Lovasi et al., 2013; Sallis et al., 2007) |

None | n/a | n/a | |

| Economic environme nt |

Economic environme nt |

Residential assessed property value |

Spatiobehavi oral and Spatiophysic al |

Greater neighborho od wealth represents more attractive environmen t for walking (Krieger et al., 1997) |

Residential assessed property value |

Local tax assessor |

Parcel polygon |

| Regional location |

CBD | Walkable (small block sizes), non- walkable (large block sizes) |

Spatiobehavi oral |

Greater proximity to CBD supports walking through greater access to destinations (Boarnet et al., 2008; Chatman, 2009) |

Walkable, nonwalkabl e CBD location |

Kernel density surface of retail and service parcels |

Point locations digitized based on secondary sources |

2.3 Data resolution and extent

Health studies examining the effect of area-based attributes on individual-level behaviors, such as the home neighborhood environment on walking, must take steps to address the uncertain geographic context problem (UGCoP). The UGCoP refers to the potential for incorrect inference if the area-based attributes are not measured at the “true causally relevant” areal unit (Kwan, 2012). Census data, although readily available, were avoided since census geographies do not correspond with how people interact with their environment (Matthews, 2008). Following recent research on the scale at which the neighborhood environment is associated with routine behaviors, we sought BE elements at the finest resolution available, often the parcel or street segment level (Berke and Moudon, 2014; Moudon et al., 2006). Fine-resolution data also allowed for the greatest flexibility in the later development of operational measurements that relate the BE characteristics to an individual’s home, work, or activity space (Thornton et al., 2011) at the areal unit hypothesized to have an effect on the individual-level behavior of interest. Since our research focused on home neighborhood walking, we collected BE data for the area within 2 km of all participants’ homes. Sometimes this extent crossed municipal, county, or state boundaries.

2.4 Data compilation

Each of the three study regions had one team member assigned to BE data collection and development. Work was coordinated through bi-weekly conference calls. A password-protected FTP site facilitated secure data exchange. Data collection commenced as the telephone survey was being conducted (Summer 2011) so that BE data temporally corresponded with survey responses. Data compilation required approximately 14 months of 33% full-time equivalent (FTE) work from the three team members – or 1.155 annual FTE. We first inventoried and collected GIS data available in the nine towns. This involved obtaining data from the municipalities, counties, regional planning organizations, state and national agencies, non-profits, transit agencies and other organizations operating in the study area. We then identified the BE characteristics that were readily available across all nine towns. In many cases, data were available but in varying formats. Therefore, an important part of our process was standardizing the data across the nine towns. For high-priority BE characteristics for which secondary GIS data were not readily available, we investigated the feasibility of developing data from internet maps, aerial images, omnidirectional imagery (i.e., Google Street View), or proprietary data sources. In-person street audits were not performed due to resource constraints. When multiple data sources were available for a single BE characteristic, the relative merits of each source were compared using a sample of the data for a subset of the nine towns. Once the preferred source data were identified for a BE characteristic, a protocol was written to specify how the data would be processed and stored as layers in an ESRI-format personal geodatabase. These protocols guided data development across study sites. All geoprocessing was conducted in ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) unless otherwise stated. ArcGIS was used because all study sites had access to the software and personnel that were proficient using it.

3. Results

For each domain we describe the secondary data sources and processing steps used to develop appropriate GIS data for research. This information is also summarized in Table 1. We then outline the protocols used to ensure consistent data quality across sites.

3.1 Generalized land uses

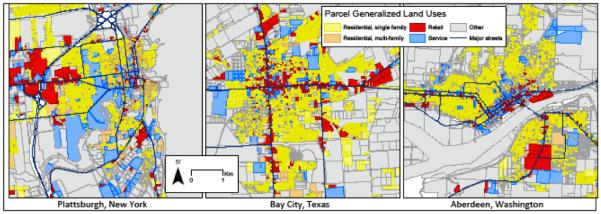

Generalized land use (GLU) classifications were based on present land use codes contained in parcel data. Original land use classification codes differed across the nine towns, so they were standardized to include residential (single and multifamily); retail; services and offices; manufacturing; cultural, entertainment, and recreational; resource production and extraction; transportation, communication, and utilities; and undeveloped land and water areas. These categories roughly aligned with standard planning classification systems (APA, 2001) and those used in prior research (Diez Roux, 2001; Frank et al., 2010; Frank et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2009). In order to implement this scheme, crosswalk tables were developed to re-classify parcel-level land use codes and to align with the study GLU classification system. Multi-use parcels (e.g., an apartment above a store) were individually evaluated and assigned a GLU based on the predominant use. GLU codes for parcels that had missing values for the source land use code were manually coded using other parcel attributes (e.g., ownership, building type) and aerial images. Additional quality control measures included manually reviewing a sample of assigned GLU codes with web-based business directories, aerial imagery, and property tax assessment values, which indicated whether the property was not vacant. Finally, assigned GLU’s were crosschecked based on the destination data discussed below. Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of residential, retail, and service GLU’s in one study town in each region.

Figure 2.

Residential, retail, and service parcels in three Small Town Walkability study towns.

Locally unwanted land uses (LULU’s) were defined as land uses beneficial to society but with externalities neighbors often find objectionable (Schively, 2007). We first compiled a list of LULU’s based on those known within the planning profession, including military bases, prisons, wastewater facilities, landfills, ATV parks, factories, and psychiatric hospitals. LULU’s were identified through available GIS data as well as online searches and confirmed using aerial imagery and parcel data’s land use and ownership attributes. Because LULU’s were often comprised of multiple parcels, polygons representing the full extent of each LULU were digitized using parcel data and aerial imagery for reference.

3.2 Morphology

Building characteristics data, such as square footage or setback from the street, were either lacking or insufficiently detailed across the nine towns. We did not attempt to collect more detailed data for the study due to budgetary constraints but also because prior research had not shown a strong influence of these BE characteristics on walking for transportation or recreation (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997).

Natural environment included waterways in the form of streams, rivers, lakes, or oceans. Public access to shorelines may have a bearing on physical activity, yet accessibility was not ubiquitous and difficult to determine. Since public shoreline access was commonly provided through parks, water features were coded as attributes of parks data. Natural environment also included topography. Slope data were derived from the U.S. Geological Survey National Elevation Dataset (NED). Elevation data were represented in raster datasets with a cell size of 1/3 arc-second (approximately 10 m), from which slope was calculated.

3.3 Density

Residential units were derived from the parcel data, which either listed the exact number or range of residential units on each parcel. When ranges of residential units were provided, numbers were imputed using assessed improvement values. When a parcel in residential use had an assessed improvement value of $0 (indicating a vacant/undeveloped lot), it was checked using the most recent available Google imagery and updated accordingly.

Employment density was defined as the number of employees on a parcel. Employment density has previously been calculated using improvement or building square footage multiplied by an employee space utilization rate that varies by industry (Moudon et al., 2010). However, improvement or building square footage data were not available from secondary sources for most of the study towns. OneSource business listings (Avention, Undated) included the number of employees for each business, but accurately geocoding all 1,000-2,500 business listings per town would have consumed too many resources. Therefore, we used large employers as indicators of areas with high concentrations of jobs. Locations of businesses with ≥100 employees were extracted from OneSource business listings and geocoded to the parcel data using the methods described under business destinations. The threshold of ≥100 employees was chosen after a review of the data found that major institutions (i.e., hospitals and colleges) in the small towns employed more than 100 people. The number of large employers ranged from 6 to 34 per town, and often included major manufacturers, big box stores, and some larger supermarkets, in addition to hospitals and colleges.

3.4 Destinations

We identified four major types of destinations that were represented as separate GIS features due to differences in spatial representation and attribute requirements. The first was individual businesses, which were spatially represented as the individual parcels on which they were located. The other three were malls, schools, and parks, which were delineated as single polygons because they often comprised multiple parcels.

Businesses were obtained from the OneSource Global Business Browser (Avention, Undated), which continually compiles business lists from over 2500 data sources. It was chosen after a detailed comparison to Business Analyst, a geo-referenced listing maintained by ESRI and updated annually, and ReferenceUSA, a geo-referenced listing that uses Infogroup data updated continually. OneSource was chosen based on its relative accessibility to the research team (one study site’s institution had a subscription to these proprietary data) and accuracy in representing four categories of walkable destinations as tested in one of the towns [full report comparing these datasets is available from corresponding author upon request]. Using OneSource data, we defined 24 different types of business destinations, 16 of which were food related. Six-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes were used to first identify potential business destinations. For our purposes, however, the codes were too coarse, so we then individually reviewed each of the businesses in the list generated by the NAICS codes and assigned them a more specific classification (e.g., businesses classified by NAICS as “Full-Service Restaurant” were reviewed and reclassified as “Ethnic Restaurant,” “Traditional Restaurant,” “Dessert,” “Bar/Tavern/Pub,” or “Pizza Place”). Each specific business classification was defined by the study team in advance using existing literature when possible [for example, (Moudon et al., 2013)]. Importantly, examples were provided of what were and were not included in the classification (e.g., the banks classification included credit unions, but not investment companies). All classified business destinations were geocoded to the parcel using an address locator based on the parcel situs (physical address of the parcel). The businesses were thus spatially represented as the tax parcel polygon on which they were located.

Malls were defined using classifications from the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) (DeLisle, 2005). Our definition included ICSC indoor malls, lifestyle centers, power centers, theme/festival centers, and outlet centers. These types of malls corresponded to shopping complexes of regional significance, with or without a food court and entertainment, and either enclosed or open air. Mall locations were identified by first creating a GIS dataset of polygons comprised of the aggregate of all retail parcels within 5 feet of one another. From this dataset, polygons ≥5 acres were reviewed using aerial imagery, online business listings, and results of Google Maps searches for “malls.” Polygons confirmed as malls were classified by ICSC mall type.

School location and facilities were identified using a combination of National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data sources, local school district websites, parcel land use and ownership data, and aerial imagery. First, NCES public pre-K through secondary school data, including enrollment, school type, and latitude and longitude, were downloaded for the most recent available school year, 2009-2010. Latitude and longitude were used to create point locations for these schools. Private school and post-secondary school data were also downloaded from NCES, but since no latitude and longitude data existed for these schools, addresses were used to geocode them to the parcel layer. Each geo-located school was reviewed using aerial imagery and parcel data to determine the extent of the campus, which was then digitized as a polygon. School facilities such as playgrounds, sports courts, tracks/trails, and fields were coded using binary indicators of their presence in the attributes for each school based on a review of aerial imagery and school and town websites.

Parks were defined as all publically owned and accessible outdoor spaces intended primarily for leisure or recreation. This definition excluded undeveloped parkland, cemeteries, golf courses, and stand-alone community centers. GIS data, maps, and addresses of parks were obtained from each city and/or county parks department. These data were compared to parcel data and aerial imagery to determine the extent of the park based on ownership and land use. Polygons were digitized to represent the full extent of each park, ensuring they did not overlap with schools or include non-recreational facilities, such as park department headquarters. Information from parks departments or aerial imagery was used to code the presence of 10 facilities and amenities (e.g., sport fields, picnic areas, restrooms). Recreational trail data were obtained and developed in a similar manner when available from local jurisdictions (although trails were digitized as polylines, not polygons).

3.5 Transportation System

Streets were identified using ESRI StreetMap USA Premium NAVTEQ 2011 release 2. These data offered greater consistency than separate municipal or county street network data that were available for each town. They also more accurately represented newer developments and access roads, although they did not include alleyways or pedestrian-only pathways in the study areas. StreetMap USA data were developed primarily for routing and geocoding, and included attributes such as address range for geocoding, street hierarchy for route choice, and average speed for travel time estimates. Thus, street hierarchy classification was used as a proxy for Federal Highway Administration functional classifications (e.g., limited access freeway, arterial, collector, and local street) (Federal Highway Administration, 2013) and speed class was used as a proxy for speed limit. Street segments identified as pedestrian accessible were used to represent the pedestrian network.

Sidewalks were coded on all pedestrian accessible street segments of a higher functional class than local, since sidewalks were deemed to be more important for facilitating pedestrian travel along streets that carry more and faster automobile traffic. Our working definition of sidewalk was modified from that used in an urban area (Kang et al., 2015) to account for possible differences in infrastructure in small towns. A sidewalk was defined as a dedicated pedestrian or mixed-use non-motorized route separated, but along the right of way of a road or street. Separation may be a curb, landscaped buffer, or change in surface material. The sidewalk could be concrete, asphalt, gravel, or dirt, but should appear to be maintained and part of municipal street infrastructure. Street segments were coded by the study team using aerial imagery and Google Street View (Wilson et al., 2012).

Street intersections were derived from the StreetMap USA data using only pedestrian accessible street segments. These segments were used to create a network dataset, which included both line segments and junctions at intersections, represented as point features. These intersection points were then spatially joined to the street segments and a count of all joining street segments was taken as the number of “ways.” Thus a one-way intersection would represent a dead end and ≥3-way intersections would represent points at which two or more streets (three or more line segments) intersect.

Crosswalks were defined as a marked area of the street indicating that pedestrians have the right to cross. Pedestrian-accessible street segments of a higher functional class than local (i.e., streets that carried a sufficient volume of traffic where crosswalks would facilitate pedestrian travel) were visually inspected using aerial imagery and Google Street View. Crosswalks were digitized as point features at locations where aerial imagery showed them intersecting the street segments. Points were coded to differentiate crosswalks at intersections and midblock.

Public transit was divided into local and intercity. Local transit service was provided in the Northeast and Washington, but not the Texas towns. It was defined as frequent service within the town and/or region – service at least three times a day and routes no longer than two hours in total length. Our definition also required that local transit service be publicly accessible (i.e. not an employee, hospital, or student transit service) and have fixed service locations and routes (i.e. not paratransit). Intercity transit was defined as less frequent service to distant destinations. Intercity transit service locations included

Greyhound terminals, Amtrak stations, and airports with commercial passenger service. Intercity transit service point locations (e.g., train stations) were obtained from the StreetMap USA database and checked against online searches for intercity bus, rail, and air service in the towns. Local transit service locations, such as bus stops or transit centers, were identified by contacting the local transit service provider and requesting data. Transit service locations not in a GIS point format were digitized manually using street network data, aerial imagery, and Google Street View to locate the precise location of service locations.

3.6 Traffic Conditions

Traffic conditions data were not collected due to inconsistent availability across the nine towns as well as the costly and complex task of systematically observing representative traffic conditions.

3.7 Neighborhood Behavioral Conditions

Neighborhood behavioral conditions data were not collected due to few secondary sources for these data. Crime rates were the exception, but these were only available at the town level – not sufficient resolution for use in a study of neighborhood walking. Physical signs of social conditions (e.g., maintenance, graffiti, vandalism) could potentially be collected remotely using Google Street View (Rundle et al., 2011), but such imagery was only available on certain major routes in the small towns at the time of this study.

3.8 Economic Environment

Residential property values were derived from the parcel data and town/county tax assessors. In all towns, land and improvement values were assessed separately. For residential land use parcels, these values were combined and divided by the number of residential units in order to obtain the average value per residential unit on each parcel. While derived from GIS BE data, residential property values function as a measure of socio-economic status. Individuals’ home property values reflect long-term wealth and vary less due to short-term changes in employment compared to self-report income. Residential property values can also overcome problems of missing data due to survey respondents’ reluctance to divulge income. Furthermore, residential property values can be used as neighborhood measures of wealth by aggregating them to the desired areal unit (Moudon et al., 2011).

3.9 Regional Location

Central Business Districts (CBD’s) were defined as clusters of retail and service businesses often, but not always located at the historic center of town. To identify concentrations of businesses and services, all retail and service land use parcels were selected and converted to points from parcel centroids. A kernel density estimation surface (Thornton et al., 2011) was then created with each 10-meter grid cell in the study area having a value representing the density of service or retail parcel at the center. The resulting “heat maps” were reviewed by the study team and points representing CBDs were digitized at locations of highest density.

3.10 Data development protocols and manuals

Protocols guided the data development procedures for each BE characteristic in order to ensure the resulting data were consistent across all nine towns. These protocols were similar to those used in other GIS health research projects (DFH, 2012; IPEN, 2012) in that each protocol contained a brief definition of the BE characteristic to be captured followed by a detailed method for doing so. The STW protocols differed in that they focused on methods for developing GIS BE data rather than measuring GIS BE data in relation to study participants (e.g., count of supermarkets in a participant’s home buffer). This is because STW GIS BE measurements were taken at a single study site using automated scripts to ensure accuracy and achieve greater efficiencies. The method section of the STW protocols included source data, detailed geoprocessing steps (sometimes illustrated with screenshots), criteria used for classification and/or judgment calls that the analyst would make, and steps for verifying the accuracy of the data using additional data sources as necessary. The school protocol is provided as an online appendix < Add link to online appendix here. For review, online appendix appears at end of manuscript >. A separate document contained data schema specifications for each GIS feature developed for the study. These specifications included the feature’s spatial representation (point, polyline, or polygon), attribute table fields and possible values, and naming conventions.

The resulting high-resolution, standardized GIS data facilitated standardized measures of study participants’ home neighborhood BE to be used as exposure variables in the study of neighborhood walking. Home neighborhood BE characteristics were measured as areal summaries (e.g., counts, ratios, averages) of characteristics within a walkable distance of home, or the distance along the pedestrian street network from home to the closest destination. The standardized data formats allowed all measurements to be taken using the same programming code executed simultaneously at one site, ensuring reliability in measurements across the nine towns.

4. Discussion

This article describes the methods used to develop standard GIS BE data from existing data sources across nine small towns in three rural U.S. regions. Use of secondary data for objective GIS BE measures is common in health research, yet there is little guidance on how to develop GIS BE data (Forsyth et al., 2006), particularly when gathered from multiple sources. The diversity of geographic sites in the STW study and the corresponding diversity of available secondary data allowed us to comprehensively chronicle the challenges of adapting secondary GIS data for research, as well as strategies to overcome these challenges.

We used a conceptual framework, existing literature, and our own hypotheses to enumerate objectively measurable characteristics of the BE relevant to active living, especially walking. To identify and review the range of possible secondary data sources for these BE characteristics, we needed to determine the study area extent and to identify all jurisdictions it covered. Once the extent was delineated and potential source data identified, the potential data needed to be assessed for accuracy, coverage, and consistency across providers.

Accuracy referred to how well the secondary data represented the BE characteristics or constructs we wished to capture, as well as how well the data represented conditions on the ground. Without a ‘gold standard’ data source, checking accuracy often involved careful reviews of metadata, spot-checks of individual BE elements, or crosschecks with other data sources.

Coverage and consistency were closely related. Coverage in this study referred to the spatial extent of the data and consistency referred to how well the data definitions and formats aligned across the study sites. National datasets were preferred as they had both complete coverage and consistency. When national datasets were not available or sufficiently accurate, local datasets were carefully reviewed for differences in how they defined and represented BE characteristics.

We were largely successful in collecting secondary GIS data that captured active living-related BE characteristics. Parcel data were available for all nine towns. These data provided information on land uses, residential density, and residential property value. When combined with other tabular datasets with location information (i.e., addresses or coordinates), such as national business or school listings or local listings of parks, the parcel data provided precise geospatial locations for these destinations. Furthermore, parcel data could be processed to help identify and, with the aid of aerial imagery, to spatially delineate agglomerations of land uses, such as LULUs, malls, and CBDs. A national GIS street network dataset was used to represent the pedestrian-accessible network in all nine towns and was updated with information on sidewalks and crosswalks with the aid of aerial or street imagery.

Although parcel data were available for all nine towns, the treatment of the parcel attributes varied widely. Building-level details such as square footage and location on the parcel were often unavailable. For this reason we were unable to collect data on many building- or parcel-level morphology characteristics, such as floor area ratio (FAR). The street network data also lacked the fine-scale details that could affect pedestrian travel, such as on-street parking, street lighting, or street furniture. Few prior studies have observed a relationship between these detailed characteristics and walking, but this may simply be due to the lack of data availability over large regions (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997). We also were unable to collect data for many spatiobehavioral variables, such as traffic volumes or fine-resolution crime or social incivilities (e.g., panhandlers, unattended dogs), or spatiophysical signs of human behaviors (e.g., seasonal decorations, security signs, graffiti). Such data would require substantial resources to collect and are likely beyond the budgetary reach of most jurisdictions or agencies operating in small towns.

The availability of GIS BE data presented here applies to small towns in the rural U.S. Yet similar results were also found internationally. The IPEN adult study reported that GIS BE data related to active living was available in cities representing 11 of 12 countries, but the BE characteristics available varied considerably among the 11 countries and were not always directly comparable (Adams et al., 2014). As in small towns, micro-scale BE features such as FAR were not commonly available internationally and only coarse land use classifications could be used due to differences in classification schemes from country to country. More comprehensive and detailed GIS BE data may be available across major metropolitan jurisdictions in the U.S. (Adams et al., 2014). Small towns have smaller municipal budgets, smaller BE inventories, and a smaller consumer market than their metropolitan counterparts, and thus likely more limited GIS BE data.

The STW study considered a wide range of BE characteristics hypothesized to influence active living in small town environments. We therefore cast a wide net when collecting GIS BE data. This required a substantial amount of resources, but also enabled us to discover associations not previously reported in metropolitan areas. For example, the presence of manufacturing land use was found to be associated with a 43% increase in odds of doing any utilitarian walking in the home neighborhood, while the presence of resource production and extraction land use was found to be associated with a 35% reduction (Doescher et al., 2014). The STW study was largely exploratory. Future walking research in small towns may wish to limit data collection activities to the BE characteristics found to be important in this study, as well as across multiple metropolitan studies. Considerable resources could be saved by focusing on a short list of BE features of greatest interest (Adams et al., 2014).

The STW found that BE Data can be readily obtained from secondary sources across study sites and they can be developed into GIS data appropriate for active living research. While available at relatively low cost, these data can only be developed through careful coordination, which, in this study, was facilitated through protocols. Protocols ensured standard, high-quality datasets by first presenting a clear definition of the BE characteristic to be captured, and then outlining specific geoprocessing steps to develop the data. Consistent quality was ensured through specifying steps to check for missing or inaccurate data through the use of other datasets, aerial or street view imagery, and/or online directories as a cross-reference. Judgment calls were often required for classification purposes, and in these cases, advice on making such judgment calls were provided in the protocols. During the course of the study, protocols were living documents, which were updated based on experiences of analysts as they developed the data.

A considerable amount of effort (> 1 annual FTE) went into collecting GIS BE data for the STW study, which has since ended. Ideally these data can be reused for surveillance or research by practitioners working in the study areas. Coordination between researchers and local agencies would help facilitate such data sharing, and could result in a positive feedback loop whereby local agencies would learn the value of such data firsthand, and as a result increase efforts to collect it on a regular basis, thus facilitating future multi-site studies. Regular data collection is important, as the BE is constantly changing, with greater rates of change when there are fewer land use regulations and geographic constraints to development (Barrington-Leigh and Millard-Ball, 2015; Reyna and Chester, 2015), which may often be the case in small towns. Furthermore, regular updates to BE data would enable these jurisdictions to track whether development was occurring in a way that supports active living.

4.1 Limitations

Resource constraints limited our ability to collect data on all BE characteristics identified in the conceptual framework. When data were collected for a BE characteristic, resource constraints sometimes limited our ability to develop comprehensive measures. For example we only measured employment using worksites with ≥100 employees and sidewalks along major streets. The resulting measures were different than what would have been obtained if all worksites and streets, respectively, were included. Results of analyses using these more limited measures must be interpreted carefully.

Resource constraints also limited our ability to evaluate the quality of the data we did collect. We could not systematically check the validity of secondary data since we had no ‘gold standard’ for comparison. We also did not assess inter-rater reliability of the data developed by study analysts. Extensive time was required to develop each BE characteristic and it would have been prohibitively expensive to repeat these efforts to determine inter-rater reliability. Instead, analysts reviewed each other’s final data for overall quality and completeness.

5. Conclusion

We chronicled methods for obtaining GIS BE variables for use in active living research from existing sources across diverse sites, especially small towns in the rural U.S. Our goal was to obtain objective BE data that were reasonably accurate, complete, and consistent, while avoiding excessive data development costs. We largely achieved this goal by drafting protocols that specified how multiple secondary datasets and online tools were to be used to develop datasets that suited our needs. Our experiences can help guide other researchers or practitioners who must accurately and objectively measure the BE as it relates to health across multiple jurisdictions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Presents framework of built environment (BE) characteristics related to health

Assesses availability of health-related GIS BE data across 9 rural towns in the U.S.

Describes challenges in developing accurate, complete, and consistent GIS BE data

Secondary GIS BE data often must be manipulated for research – protocols can help

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (1R01HL103478-01A1). The authors wish to acknowledge the input and support received from all members of the STW study team while developing GIS BE data. Additional STW study team members include Davis G. Patterson, Barbara Matthews, Anna M. Adachi-Mejia, Chun-kuen Lee, Glen E. Duncan, and Brian E. Saelens. Additional support was provided by The Norris Cotton Cancer Center’s GeoSpatial Resource.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams MA, Frank LD, Schipperijn J, Smith G, Chapman J, Christiansen LB, Coffee N, Salvo D, du Toit L, Dygryn J, Hino AA, Lai PC, Mavoa S, Pinzon JD, Van de Weghe N, Cerin E, Davey R, Macfarlane D, Owen N, Sallis JF. International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Planning Association (APA) Land Based Classification Standards (LBCS) 2001 Retrieved July 29, 2014, from www.planning.org/lbcs.

- Avention, Undated. OneSource Global Business Browser Retreived August 13, 2015, from www.avention.com/products/global-business-browser.

- Barrington-Leigh C, Millard-Ball A. A century of sprawl in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:8244–8249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504033112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke EM, Moudon AV. Built environment change: a framework to support health-enhancing behaviour through environmental policy and health research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2014;68:586–590. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrigan D, Pickle LW, Dill J. Associations between street connectivity and active transportation. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarnet MG, Greenwald M, McMillan TE. Walking, Urban Design, and Health: Toward a Cost-Benefit Analysis Framework. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 2008;27:341–358. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;36:S99–123. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005. e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C, Aytur S, Gardner K, Rogers S. Complexity in built environment, health, and destination walking: a neighborhood-scale analysis. J. Urban Health. 2012;89:270–284. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9652-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerin E, Leslie E, du Toit L, Owen N, Frank LD. Destinations that matter: associations with walking for transport. Health Place. 2007;13:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerin E, Vandelanotte C, Leslie E, Merom D. Recreational facilities and leisure-time physical activity: An analysis of moderators and self-efficacy as a mediator. Health Psychol. 2008;27:S126–135. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero R, Kockelman K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 1997;2:199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman DG. Residential choice, the built environment, and nonwork travel: evidence using new data and methods. Env. Plan. A. 2009;41:1072–1089. [Google Scholar]

- de Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Anto JM, Brauer M, Briggs D, Braun-Fahrlander C, Cavill N, Cooper AR, Desqueyroux H, Fruin S, Hoek G, Panis LI, Janssen N, Jerrett M, Joffe M, Andersen ZJ, van Kempen E, Kingham S, Kubesch N, Leyden KM, Marshall JD, Matamala J, Mellios G, Mendez M, Nassif H, Ogilvie D, Peiro R, Perez K, Rabl A, Ragettli M, Rodriguez D, Rojas D, Ruiz P, Sallis JF, Terwoert J, Toussaint JF, Tuomisto J, Zuurbier M, Lebret E. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: a review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ. Int. 2011;37:766–777. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisle JR. Shopping Center Classifications: Challenges and Opportunities, a white paper for International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) Research. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Design For Health (DFH) Environment and Physical Activity GIS Protocols Manual. 2012 Retrieved August 13, 2015, from http://designforhealth.net/resources/other/gis-protocols.

- Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Lee C, Berke EM, Adachi-Mejia AM, Lee C.-k., Stewart O, Patterson DG, Hurvitz PM, Carlos HA, Duncan GE, Moudon AV. The Built Environment and Utilitarian Walking in Small U.S. Towns. Prev. Med. 2014;69:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MJ, Winkler E, Sugiyama T, Cerin E, duToit L, Leslie E, Owen N. Relationships of land use mix with walking for transport: do land uses and geographical scale matter? J. Urban Health. 2010;87:782–795. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9488-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand CP, Andalib M, Dunton GF, Wolch J, Pentz MA. A systematic review of built environment factors related to physical activity and obesity risk: implications for smart growth urban planning. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:e173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson U, Arvidsson D, Gebel K, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K. Walkability parameters, active transportation and objective physical activity: moderating and mediating effects of motor vehicle ownership in a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, Sallis JF, Handy SL, Bell R, Brennan LK. Evaluation of physical projects and policies from the Active Living by Design partnerships. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;43:S309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R. Beyond density, mode choice, and single purpose trips. Transp. Q. 1995;49:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Highway Administration Highway Functional Classification Concepts, Criteria and procedures. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth A, Schmitz KH, Oakes M, Zimmerman J, Koepp J. Standards for Environmental Measurement Using GIS: Toward a Protocol for Protocols. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2006;3:S241–S257. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Giles-Corti B. The built environment, neighborhood crime and constrained physical activity: an exploration of inconsistent findings. Prev. Med. 2008;47:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Giles-Corti B, Knuiman M. Neighbourhood design and fear of crime: a social-ecological examination of the correlates of residents' fear in new suburban housing developments. Health Place. 2010;16:1156–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Kavage S. A national plan for physical activity: the enabling role of the built environment. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2009;6(Suppl 2):S186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Leary L, Cain K, Conway TL, Hess PM. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports. Med. 2010;44:924–933. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Schmid TL, Sallis JF, Chapman J, Saelens BE. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005;28:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Physical Activity and the Environment Network (IPEN) Methods & Measures: GIS & Audits. 2012 Retrieved August 13, 2015, from http://www.ipenproject.org/methods_gis.html. [Google Scholar]

- Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC. Observed, GIS, and self-reported environmental features and adolescent physical activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 2006;20:422–428. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.6.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Berrigan D, Hart JE, Hipp JA, Hoehner CM, Kerr J, Major JM, Oka M, Laden F. Effects of buffer size and shape on associations between the built environment and energy balance. Health Place. 2014;27:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B, Scully JY, Stewart O, Hurvitz PM, Moudon AV. Split-Match-Aggregate (SMA) algorithm: integrating sidewalk data with transportation network data in GIS. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015;29:440–453. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 1997;18:341–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MP. The Uncertain Geographic Context Problem. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2012;102:958–968. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Moudon AV. Correlates of walking for transportation or recreation purposes. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2006;3:S77–S98. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Ory MG, Yoon J, Forjuoh SN. Neighborhood walking among overweight and obese adults: age variations in barriers and motivators. J. Community Health. 2013;38:12–22. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Robbel N, Dora C. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. Cross-country Analysis of the Institutionalization of Health Impact Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fisher KJ, Brownson RC, Bosworth M. Multilevel modelling of built environment characteristics related to neighbourhood walking activity in older adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2005;59:558–564. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi GS, Schwartz-Soicher O, Neckerman KM, Konty K, Kerker B, Quinn J, Rundle A. Aesthetic amenities and safety hazards associated with walking and bicycling for transportation in New York City. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013;45(Suppl 1):S76–85. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, Glonti K, Oppert JM, Charreire H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J, Nijpels G, Lakerveld J. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA. The salience of neighborhood: some lessons from sociology. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;34:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack GR, Giles-Corti B, Bulsara M. The relationship between destination proximity, destination mix and physical activity behaviors. Prev. Med. 2008;46:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack GR, Shiell A. search of causality: a systematic review of the relationship between the built environment and physical activity among adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn AP, Evenson KR, Herring AH, Huston SL, Rodriguez DA. Exploring associations between physical activity and perceived and objective measures of the built environment. J. Urban Health. 2007;84:162–184. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9136-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Cook AJ, Ulmer J, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A. A neighborhood wealth metric for use in health studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011;41:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Drewnowski A, Duncan GE, Hurvitz PM, Saelens BE, Scharnhorst E. Characterizing the food environment: pitfalls and future directions. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:1238–1243. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Lee C. Walking and bicycling: an evaluation of environmental audit instruments. Am. J. Health Promot. 2003;18:21–37. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Lee C, Cheadle AD, Garvin C, Johnson D, Schmid TL, Weathers RD, Lin L. Operational definitions of walkable neighborhood: theoretical and empirical insights. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2006;3 doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Lee C, Cheadle AD, Garvin C, Rd DB, Schmid TL, Weathers RD. Attributes of environments supporting walking. Am. J. Health Promot. 2007;21:448–459. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Sohn DW, Kavage SE, Mabry JE. Transportation-Efficient Land Use Mapping Index (TELUMI), a Tool to Assess Multimodal Transportation Options in Metropolitan Regions. Int. J. Sustainable Transp. 2010;5:111–133. [Google Scholar]

- New York City (NYC) Departments of City Planning, Transportation, Health and Mental Hygiene, and Design and Construction 2010 Active Design Guidelines. Retrieved June 03, 2014, from www.nyc.gov/html/ddc/html/design/active_design.shtml.

- Rapoport A. History and Precendent in Environmental Design; Plenum, New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport A. Pedestrian Street Use: Culture and Perception. In: Moudon AV, editor. Public Streets for Public Use. Columbia University Press; New York: 1991. pp. 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Reyna JL, Chester MV. The Growth of Urban Building Stock: Unintended Lock-in and Embedded Environmental Effects. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 2015;19:524–537. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez DA, Evenson KR, Diez Roux AV, Brines SJ. Land use, residential density, and walking. The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;37:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle AG, Bader MD, Richards CA, Neckerman KM, Teitler JO. Using Google Street View to audit neighborhood environments. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011;40:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S550–566. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Cain KL, Conway TL, Chapman JE, Slymen DJ, Kerr J. Neighborhood environment and psychosocial correlates of adults' physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012;44:637–646. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318237fe18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Moudon AV, Kang B, Hurvitz PM, Zhou C. Relation between higher physical activity and public transit use. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:854–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, King AC, Sirard JR, Albright CL. Perceived environmental predictors of physical activity over 6 months in adults: activity counseling trial. Health Psychol. 2007;26:701–709. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schively C. Understanding the NIMBY and LULU Phenomena: Reassessing Our Knowledge Base and Informing Future Research. Journal of Planning Literature. 2007;21:255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton LE, Pearce JR, Kavanagh AM. Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to assess the role of the built environment in influencing obesity: a glossary. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilt JH, Unfried TM, Roca B. Using objective and subjective measures of neighborhood greenness and accessible destinations for understanding walking trips and BMI in Seattle, Washington. Am. J. Health Promot. 2007;21:371–379. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.4s.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Lee C. Site and neighborhood environments for walking among older adults. Health Place. 2010;16:1268–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JS, Kelly CM, Schootman M, Baker EA, Banerjee A, Clennin M, Miller DK. Assessing the built environment using omnidirectional imagery. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;42:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.