Abstract

Background

Ethnic differences in clinical characteristics, stroke risk profiles and outcomes among atrial fibrillation (AF) patients may exist. We therefore compared AF patients with previous stroke from Japan and the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods

We compared clinical characteristics, stroke risk and outcomes among AF patients from the Fushimi AF registry who had experienced a previous stroke (Japan; n = 688; 19.7%) and the Darlington AF registry (UK; n = 428; 19.0%).

Results

AF patients with previous stroke in Fushimi were significantly younger (76.8 and 79.6 years of age in Fushimi and Darlington; p < 0.01) with a lower proportion of females (37.4% vs. 45.1%; p = 0.01) than those from Darlington. Although the CHA2DS2-VASc score was lower in AF patients in Fushimi than those in Darlington (5.18 vs. 5.57; p < 0.01), oral anticoagulation (OAC) was prescribed significantly more frequently in Fushimi (68.3%) than Darlington (61.7%) (p = 0.02). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that Japanese ethnicity was associated with a significantly decreased risk of recurrent stroke (OR 0.59. 95% CI 0.36–0.97; p = 0.04) but a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.18–2.66; p < 0.01) in AF patients with previous stroke.

Conclusions

AF patients with previous stroke in the UK were at higher risk of recurrent stroke compared to Japanese patients, but OAC was utilised less frequently. There was a lower risk of recurrent stroke in the secondary prevention cohort from the Fushimi registry, but an increased risk of all-cause mortality.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Previous stroke, Secondary prevention, Observational, Japan, United Kingdom

Highlights

-

•

The UK vs. Japanese AF patients are at higher risk of recurrent stroke.

-

•

OAC are utilised less frequently in the UK than in Japan.

-

•

Japanese vs. UK AF patients have increased all-cause mortality.

Ethnic differences in clinical characteristics, stroke risk profiles and outcomes among atrial fibrillation (AF) patients may exist. We therefore compared community-based AF patients with a history of previous stroke (i.e. a secondary prevention cohort) from Japan and the United Kingdom (UK). We found that AF patients with previous stroke in the UK were at higher risk of recurrent stroke compared to Japanese patients, but anticoagulation was utilised less frequently. Ethnicity was related to a lower risk of recurrent stroke in the Japanese secondary prevention cohort, but Japanese AF patients had an increased risk of all-cause mortality.

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) patients are at the increased risk of ischemic stroke and death (Kopecky et al., 1987, Wolf et al., 1991). Of the various risk factors, previous stroke or transient ischemic attach (TIA) are the most powerful risk factors for subsequent ischemic stroke and confer a significant risk of mortality and recurrent stroke, approximately 12% per year, if left untreated (Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group, 2007). Indeed, AF-related ischemic strokes are generally more disabling and more often life-threatening than other types of stroke (Marini et al., 2005). Thus, secondary prevention with oral anticoagulant (OAC) is crucial for AF patients with previous stroke EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group (1993). However, little is known about possible differences in the clinical characteristics, practices and outcomes between AF patients with previous stroke in Japan compared to their British counterparts.

In this study, we used individual-level patient data from the Fushimi AF registry and the Darlington AF registry to assess differences in clinical characteristics, stroke risk profiles and outcomes among AF patients with previous stroke or TIA.

2. Materials and Methods

The details of the study designs, patient enrolment, definitions used, and baseline patient clinical characteristics of the Fushimi AF registry (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000005834) and the Darlington AF registry have been previously described (Akao et al., 2013, Shantsila et al., 2015).

2.1. Fushimi AF Registry

The Fushimi AF registry is a prospective, observational registry intended to identify the current status of AF patients in a community-based clinical setting in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, Japan (Akao et al., 2013). Fushimi-ku is an urban administrative district in the southern area of the city of Kyoto, with a total population of 284,000 (Japanese were > 99%) in 2011. The enrolment of patients with AF documented on a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) or Holter monitoring at any time (with no exclusion criteria) commenced in March 2011. Eighty institutions (all members of Fushimi-Ishikai (Fushimi Medical Association)) participated in this registry and attempted to enroll all consecutive AF patients under regular outpatient care or under admission. Follow-up data was collected annually through review of the inpatient and outpatient medical records, and contact with patients, relatives and/or referring physicians by mail or telephone. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committees of the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center and Ijinkai Takeda General Hospital.

2.2. Darlington AF Registry

The study population of the Darlington AF registry was derived from all 105,000 patients who were registered at one of 11 general practices serving the town of Darlington, UK (Shantsila et al., 2015), a market town, with a resident population of 106,000 in 2011. According to the last Census data in the Darlington cohort, > 96% of population were White Caucasian in Darlington. All patients with a history of AF or atrial flutter whose vital status in March 2013 was known, were eligible for inclusion. Demographic and clinical data were collected from electronic GP records (followup is still ongoing as part of routine clinical care in this contemporary primary care population) including stroke risk factors and antithrombotic treatment (Cowan et al., 2013, Shantsila et al., 2015).

In the present study, we used the data from all the AF patients in the Fushimi AF registry (n = 3499) and those with follow-up information in the Darlington AF registry (n = 2259). We identified those patients who had a history of stroke or TIA (n = 688 in Fushimi AF registry; n = 428 in Darlington AF registry) and categorized stroke risk using the CHADS2 (Gage et al., 2001) and CHA2DS2-VASc scores (Lip et al., 2010). OAC was defined as vitamin K antagonists (predominantly warfarin) and non-vitamin K antagonists (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban). The primary outcomes of the present study were the incidence of any-cause recurrent stroke and all-cause mortality during the 12-month follow-up period. The secondary outcome was a composite of any-cause stroke and all-cause mortality during the first year.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The incidence of stroke and all-cause mortality during the one-year follow-up period were calculated as number and percentage. Censoring was done for the first event recorded. We compared categorical variables using the chi-square test and continuous variables using independent samples t-test for normally distributed data or Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal distribution. The unadjusted odds ratios were determined using logistic regression for each risk profile. The predictive accuracy of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores for the study subjects was determined using receiver-operator characteristic curves. Finally, to determine independent risk factors for stroke and all-cause mortality, we carried out multivariate logistic regression using age, sex, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), vascular disease and OAC prescription at baseline as co-varieties. These analyses were performed using JMP version 12.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set as a two-sided p-value of < 0.05.

3. Results

The analyses included 1116 AF patients with history of stroke or TIA at baseline (Fushimi AF registry, n = 688; Darlington AF registry, n = 428). The secondary prevention AF patients in the Fushimi registry were significantly younger, with fewer females and less likely to have hypertension and vascular disease, compared with those in the Darlington registry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and medication of the secondary stroke prevention cohort at baseline.

| Number (%) | Fushimi AF registry (Japan) (n = 688) | Darlington AF registry (UK) (n = 428) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 76.8 (9.5) | 79.6 (9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age < 65 years | 70 (10.2) | 28 (6.5) | 0.002 |

| Age 65–74 years | 194 (28.2) | 93 (21.7) | |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 424 (61.6) | 307 (71.7) | |

| Female gender | 257 (37.4) | 193 (45.1) | 0.010 |

| Heart failure | 191 (27.8) | 106 (24.8) | 0.271 |

| Hypertension | 443 (64.4) | 305 (71.3) | 0.018 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 169 (24.6) | 120 (28.0) | 0.198 |

| Vascular disease | 85 (12.4) | 97 (22.7) | < 0.001 |

| Mean CHADS2 score (SD) | 3.78 (0.97) | 3.96 (0.94) | 0.003 |

| Mean CHA2DS2-VASc score (SD) | 5.18 (1.34) | 5.57 (1.27) | < 0.001 |

| Medication | |||

| OAC | 470 (68.3) | 264 (61.7) | 0.023 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 430 (62.5) | 257 (60.1) | 0.413 |

| Non-vitamin K antagonist | 40 (5.8) | 7 (1.6) | 0.001 |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 273 (39.7) | 175 (40.9) | 0.689 |

| Concomitant use of OACs and anti-platelet drugs | 160 (23.3) | 39 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

AF: atrial fibrillation, OAC: oral anticoagulants; UK: United Kingdom.

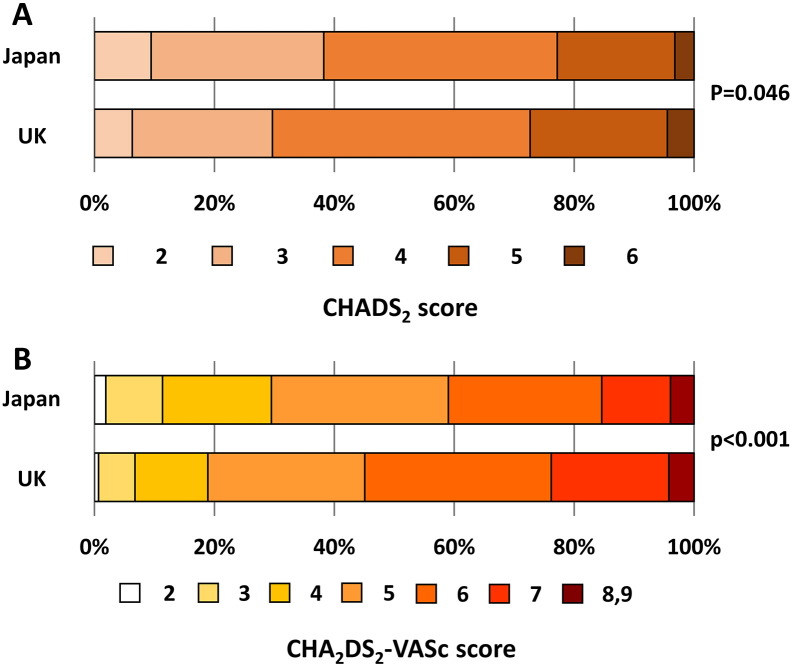

Mean CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were significantly lower in Fushimi registry patients. The distribution of age group is shown in Table 1. The proportion of elderly patients was higher in the Darlington registry with > 70% age ≥ 75 years; 17 (2.5%) patients in Fushimi and 18 (4.2%) patients in Darlington were aged ≥ 95 years. Patients with CHADS2 score ≤ 3 were more frequent in Fushimi significantly (p = 0.004) (Fig. 1A and B), while patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 6 were significantly more common in the Darlington cohort (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of CHADS2 score (A) and CHA2DS2-VASc score (B) among Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK) AF patients.

3.1. Antithrombotic Drug Use in Both Registries

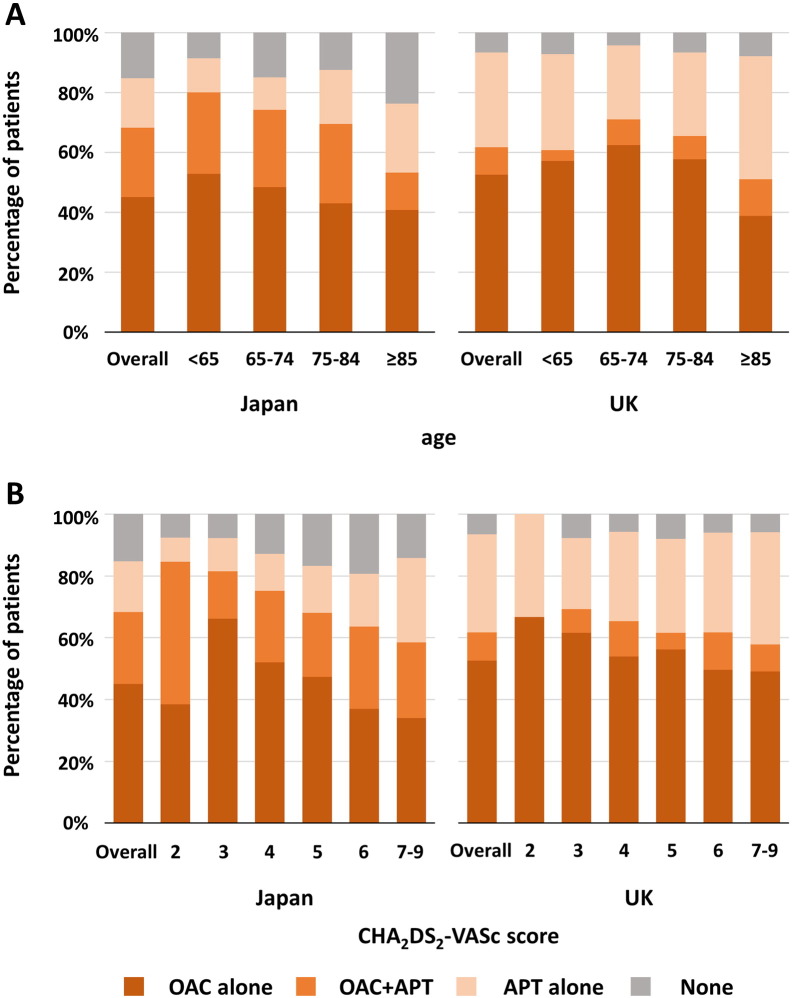

OAC was prescribed more often in the Fushimi cohort than the Darlington cohort (68.3% vs. 61.7%; p = 0.023) (Table 1). The prescription of vitamin K antagonist (VKA, predominantly warfarin) was comparable (62.5% vs. 60.1%; p = 0.413), but prescription of non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOAC) was significantly higher in Japan than in the UK (5.8% vs. 1.6%). The prescription of anti-platelet therapy drugs (APT), including monotherapy or as combination therapy, was comparable (39.7% vs. 40.9%; p = 0.689), with concomitant use of OAC and APT being significantly more frequent in the Fushimi cohort (23.3% vs. 9.1%), in all age groups and CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Fig. 2 shows the prescription of antithrombotic therapy according to age (Fig. 2A) and CHA2DS2-VASc score (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK) patients prescribed oral anticoagulant according to age (A) and CHA2DS2-VASc score (B).

APT: anti-platelet therapy, OAC: oral anti-coagulants.

In Darlington, the age 85 + group had a higher rate of OAC and AP use than all other age subgroups.

3.2. Study Outcomes

During one-year of follow-up, stroke occurred in 33 (4.8%) and 37 (8.6%) patients in the Fushimi and Darlington cohorts, respectively (unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for Fushimi vs. Darlington, 0.53 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.33–0.87, p = 0.011)) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study outcomes during the first year of follow-up for patients in the Fushimi and Darlington AF registries.

| Stroke |

All-cause mortality |

Stroke + All-cause mortality |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fushimi AF registry |

Darlington AF registry |

Fushimi AF registry |

Darlington AF registry |

OR | 95% CI | Fushimi AF registry |

Darlington AF registry |

OR | 95% CI | Fushimi AF registry |

Darlington AF registry |

OR | 95% CI | |||||||

| Patients [n (%)] | Patients [n (%)] | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | Events (n) | Incidece rate (%) | |||||||

| All patients | 688 (100.0) | 428 (100.0) | 33 | 4.8 | 37 | 8.6 | 0.53 | 0.33–0.87 | 93 | 13.5 | 42 | 9.8 | 1.44 | 0.98–2.13 | 116 | 16.9 | 73 | 17.1 | 0.99 | 0.72–1.36 |

| Age 65–74 yr | 194 (28.2) | 93 (21.7) | 6 | 3.1 | 7 | 7.5 | 0.39 | 0.12–1.21 | 14 | 7.2 | 4 | 4.3 | 1.73 | 0.60–6.24 | 18 | 9.3 | 10 | 10.7 | 0.85 | 0.38–1.99 |

| Age ≥ 75 yr | 424 (61.6) | 307 (71.7) | 25 | 5.9 | 28 | 9.1 | 0.62 | 0.35–1.09 | 73 | 17.2 | 37 | 12.1 | 1.52 | 1.00–2.34 | 92 | 21.7 | 60 | 19.5 | 1.14 | 0.79–1.65 |

| Female | 257 (37.4) | 193 (45.1) | 14 | 5.5 | 19 | 9.8 | 0.53 | 0.25–1.08 | 43 | 16.7 | 21 | 10.9 | 1.65 | 0.95–2.93 | 52 | 20.2 | 36 | 18.7 | 1.11 | 0.69–1.79 |

| Heart failure | 191 (27.8) | 106 (24.8) | 11 | 5.8 | 9 | 8.5 | 0.66 | 0.26–1.69 | 38 | 19.9 | 13 | 12.3 | 1.78 | 0.92–3.63 | 45 | 23.6 | 20 | 18.9 | 1.33 | 0.74–2.43 |

| Hypertension | 443 (64.4) | 305 (71.3) | 26 | 5.9 | 26 | 8.5 | 0.67 | 0.38–1.18 | 62 | 14.0 | 30 | 9.8 | 1.49 | 0.95–2.40 | 80 | 18.1 | 52 | 17.1 | 1.07 | 0.73–1.58 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 169 (24.6) | 120 (28.0) | 8 | 4.7 | 14 | 11.7 | 0.38 | 0.15–0.91 | 25 | 14.8 | 17 | 14.2 | 1.05 | 0.54–2.08 | 30 | 17.8 | 28 | 23.3 | 0.71 | 0.40–1.27 |

| Vascular desease | 85 (12.4) | 97 (22.7) | 7 | 8.2 | 8 | 8.3 | 1.00 | 0.34–2.90 | 16 | 18.8 | 14 | 14.4 | 1.37 | 0.63–3.05 | 20 | 22.5 | 19 | 19.6 | 1.26 | 0.62–2.58 |

| Anti-platelet therapy | 273 (39.7) | 175 (40.9) | 14 | 5.1 | 19 | 10.9 | 0.44 | 0.21–0.91 | 39 | 14.3 | 19 | 10.9 | 1.37 | 0.77–2.50 | 48 | 17.6 | 37 | 21.1 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.29 |

| OAC | 470 (68.3) | 264 (61.7) | 19 | 4.0 | 24 | 9.1 | 0.42 | 0.22–0.78 | 46 | 9.8 | 14 | 5.3 | 1.94 | 1.07–3.72 | 60 | 12.8 | 36 | 13.6 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.56 |

AF: atrial fibrillation, CI: confidence interval, OAC: oral anticoagulant, OR: odds ratio. Significant OR and 95% CI were presented in bold.

Japanese ethnicity was associated with a lower incidence of recurrent stroke in patients with diabetes (OR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.15–0.91) and in those taking OAC (OR 0.42; 95% CI: 0.22–0.78). On multivariate logistic regression analysis, Japanese ethnicity was independently associated with a reduced risk of stroke (OR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.36–0.97, p = 0.039) (Table 3), however, OAC prescription was not associated with a significant reduction in the risk of stroke (OR 0.92; 95%CI: 0.56–1.55, p = 0.754).

Table 3.

Multivariate adjusted odds ratios for stroke and all-cause mortality in patients with previous stroke.

| Stroke |

All-cause mortality |

Stroke + All-cause mortality |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Japanese ethnicity | 0.59 | 0.36–0.97 | 0.039 | 1.76 | 1.18–2.66 | 0.005 | 1.15 | 0.82–1.61 | 0.415 |

| Age < 65 | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Age 65–74 | 0.99 | 0.34–3.62 | 0.992 | 0.77 | 0.32–2.05 | 0.577 | 0.97 | 0.45–2.27 | 0.943 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 1.49 | 0.58–5.07 | 0.437 | 1.88 | 0.88–4.63 | 0.106 | 2.17 | 1.11–4.78 | 0.022 |

| Female gender | 1.24 | 0.75–2.07 | 0.399 | 1.20 | 0.81–1.77 | 0.355 | 1.17 | 0.84–1.63 | 0.362 |

| Hypertension | 1.31 | 0.76–2.35 | 0.335 | 0.99 | 0.67–1.50 | 0.976 | 1.07 | 0.76–1.53 | 0.710 |

| Heart failure | 1.04 | 0.59–1.77 | 0.890 | 1.61 | 1.08–2.39 | 0.019 | 1.43 | 1.00–2.02 | 0.048 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.31 | 0.75–2.21 | 0.339 | 1.34 | 0.88–2.01 | 0.175 | 1.33 | 0.92–1.89 | 0.127 |

| Vascular disease | 1.28 | 0.66–2.32 | 0.451 | 1.53 | 0.94–2.45 | 0.085 | 1.31 | 0.85–1.98 | 0.214 |

| OAC prescription | 0.92 | 0.56–1.55 | 0.754 | 0.38 | 0.26–0.56 | < 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.37–0.70 | < 0.001 |

CI: confidence interval, OAC: oral anticoagulant, OR: odds ratio.

All-cause mortality occurred in 135 (12.1%) patients overall (93 (13.5%) and 42 (9.8%) patients in the Fushimi and Darlington cohorts, respectively; unadjusted OR 1.44 (95% CI) 0.98–2.13, p = 0.062) (Table 2). Japanese ethnicity was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality in patients taking OAC (OR 1.94; 95% CI: 1.07–3.72) (Table 2).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that Japanese ethnicity was independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (OR 1.76; 95% CI: 1.18–2.66) (Table 3).

Furthermore, heart failure was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (OR 1.61; 95% CI: 1.08–2.39) and OAC prescription was associated with a reduced risk of death from any cause (OR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.26–0.56).

Analysis of the composite outcome of ‘stroke or all-cause mortality’ demonstrated that Japanese ethnicity was not associated with an independent increased risk among AF patients with previous stroke (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.82–1.61).

4. Discussion

The major finding of the present study was that the characteristics of AF patients with previous stroke were different between the Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK) registries. AF patients in Fushimi were younger, less likely to have various comorbidities and were at lower risk of recurrent stroke. Second, OAC was prescribed only in approximately 60% of patients with previous stroke in both registries, despite the indication for OAC given the high risk of recurrent stroke. Indeed, prescription patterns of antithrombotic drugs were different between the Fushimi and Darlington cohorts. OAC was prescribed more often in the Fushimi cohort and the concomitant use of OAC and APT was higher in Fushimi than Darlington. Third, ethnic setting (Fushimi vs. Darlington) was an independent risk factor for outcomes; Fushimi registry subjects were significantly associated with a decreased risk of stroke and an increased risk of all-cause mortality.

4.1. Antithrombotic Drug Prescription in Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK)

AF patients with a previous stroke are at high risk of recurrent stroke and should be given anticoagulation therapy according to recent treatment guidelines in both countries (Camm et al., 2010, JCS Joint Working Group, 2014; National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2014)), however, OAC was still under-utilised in both populations, consistent with other data. (Go et al., 1999, Atarashi et al., 2011, Cowan et al., 2013, Kakkar et al., 2013, Barra and Fynn, 2015) Despite lower mean CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in Fushimi, overall prescription of OAC was higher; the main difference in OAC prescription was evident in greater NOAC prescriptions in Fushimi (although the proportion was quite low in both countries). Indeed, the UK was one of the European countries with previously relatively low NOAC prescription. (Kirchhof et al., 2014).

In our study, the concomitant use of OAC and APT was higher in Fushimi, although Japanese patients were less likely to have vascular disease. The addition of APT to OAC in AF patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is commonly observed in daily clinical practice. However, combination of OAC and APT was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding and with no reduction in stroke. (Flaker et al., 2006, Toyoda et al., 2008).

4.2. Outcome Differences Between Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK)

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, ethnic setting (Fushimi, Japan) was associated with a decreased risk of stroke. It might be possible that control of VKA and prescription of NOAC affect difference in risk of stroke between Fushimi (Japan) and Darlington (UK). Indeed, the higher stroke recurrence in Darlington may relate to the lower use of OAC and NOAC in this population. However, the incident rate of stroke in Darlington (8.6%/year) was consistent previous studies from Europe. (Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group, 2007) In contrast, Kodani et al. (2016) reported that the two-year incidence of thromboembolism in Japanese AF patients with secondary prevention was 2.2% in patients with warfarin and 8.7% without warfarin. In a recent Japanese sub-analysis of NOAC trials, the incidence of stroke or systemic embolism for both warfarin and NOAC groups in Japan were generally lower than global rates (Hori et al., 2011, Hori et al., 2012, Ogawa et al., 2011, Shimada et al., 2015), Meanwhile, it was reported from NOAC trials that Asians have the same or possibly higher risk of thromboembolism, comparing non-Asians.(Chiang et al., 2014).

Mortality in AF can be high in the secondary prevention setting, for example, Marini et al. (2005) reported that the one-year mortality rate was 49.5% in first-ever ischemic stroke patients with AF. We found that ethnic setting (Fushimi) in our study was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Unfortunately, we have scarce details concerning fatal stroke and cause of death in this cohort. Differences, in ethnicity, culture, lifestyle, religion, and the comprehensive management of patients with previous stroke within different local health care systems, all influence differences in all-cause mortality.

In the combined Fushimi and Darlington cohorts, OAC was independently associated with lower all-cause mortality and ‘stroke + mortality’ – this is consistent with the historical trials where OAC significantly reduced mortality. In ‘real world’ registries such as this, some deaths may be undiagnosed strokes, as no postmortems are mandated nor events adjudicated (unlike a clinical trial).

4.3. Limitations

The study is limited by its analysis of combined data from two different cohorts of AF patients in Japan and UK. Differences in the methods of data collection among the two databases were evident, and the data were not collected from clinical institutions all over their respective country. Also, antithrombotic drugs and doses were selected at the discretion of the attending physician and were not randomized. Indeed, we cannot account for physician (or patient) preferences in management decisions, although national guidelines in both UK and Japan do not markedly differ in their approaches. We also have no data on the type of previous stroke and neurological severity/disability of the patients, such as National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) or modified Rankin scale (mRS). Darlington is a small town in the UK, and there is no indication that results from this town generalize to other UK white populations from other small UK towns, rural areas and larger cities given wide variation in healthcare across the UK. Unmeasured or residual confounders may remain, despite our multivariate analyses adjusting for differences in demography and comorbidities.

5. Conclusions

AF patients with previous stroke in Darlington (UK) were at higher risk of recurrent stroke compared to Fushimi (Japan) patients, but OAC was less frequently used. There was a lower risk of recurrent stroke in the secondary prevention cohort from the Fushimi registry, but an increased risk of all-cause mortality.

Declarations of Interest

Hisashi Ogawa: Dr. Ogawa has no disclosures to make.

Keitaroo Senoo: Dr. Senoo received a research grant from the Sasakawa Foundation.

Yoshimori An: Dr. An has no disclosures to make.

Alena Shantsila: Dr. Shantsila has no disclosures to make.

Eduard Shantsila: Dr. Shantsila has no disclosures to make.

Deirdre A Lane: DL has received investigator-initiated educational grants from Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb, served on speaker bureaus for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer and as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Andreas Wolff: Clinical advisor to Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, BMS, Sanofi Aventis and Daiichi-Sankyo. AW is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi and Pfizer.

Masaharu Akao: Dr. Akao received lecture fees from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare and Daiichi-Sankyo.

Gregory YH Lip: Consultant for Bayer/Janssen, Astellas, Merck, Sanofi, BMS/Pfizer, Biotronik, Medtronic, Portola, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife and Daiichi-Sankyo. Speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife, Roche and Daiichi-Sankyo.

Acknowledgements

The Fushimi AF registry is supported by research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis Pharma, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis and Takeda Pharmaceutical. This research is partially supported by the Practical Research Project for Life-Style related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (15656344).

References

- EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. Lancet. 1993;342:1255–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akao M., Chun Y.H., Wada H., Esato M., Hashimoto T., Abe M., Hasegawa K., Tsuji H., Furuke K. Current status of clinical background of patients with atrial fibrillation in a community-based survey: the Fushimi AF registry. J. Cardiol. 2013;61:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarashi H., Inoue H., Okumura K., Yamashita T., Kumagai N., Origasa H. Present status of anticoagulation treatment in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the J-RHYTHM registry. Circ. J. 2011;75:1328–1333. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra S., Fynn S. Untreated atrial fibrillation in the United Kingdom: understanding the barriers and treatment options. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2015;27:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm A.J., Kirchhof P., Lip G.Y., Schotten U., Savelieva I., Ernst S., Van Gelder I.C., Al-Attar N., Hindricks G., Prendergast B., Heidbuchel H., Alfieri O., Angelini A., Atar D., Colonna P., De Caterina R., De Sutter J., Goette A., Gorenek B., Heldal M., Hohloser S.H., Kolh P., Le Heuzey J.Y., Ponikowski P., Rutten F.H. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C.E., Wang K.L., Lip G.Y. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an Asian perspective. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:789–797. doi: 10.1160/TH13-11-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan C., Healicon R., Robson I., Long W.R., Barrett J., Fay M., Tyndall K., Gale C.P. The use of anticoagulants in the management of atrial fibrillation among general practices in England. Heart. 2013;99:1166–1172. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaker G.C., Gruber M., Connolly S.J., Goldman S., Chaparro S., Vahanian A., Halinen M.O., Horrow J., Halperin J.L. Risks and benefits of combining aspirin with anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: an exploratory analysis of stroke prevention using an oral thrombin inhibitor in atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF) trials. Am. Heart J. 2006;152:967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage B.F., Waterman A.D., Shannon W., Boechler M., Rich M.W., Radford M.J. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go A.S., Hylek E.M., Borowsky L.H., Phillips K.A., Selby J.V., Singer D.E. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;131:927–934. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-12-199912210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori M., Connolly S.J., Ezekowitz M.D., Reilly P.A., Yusuf S., Wallentin L. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation – sub-analysis in Japanese population in RE-LY trial. Circ. J. 2011;75:800–805. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori M., Matsumoto M., Tanahashi N., S-i Momomura, Uchiyama S., Goto S., Izumi T., Koretsune Y., Kajikawa M., Kato M., Ueda H., Iwamoto K., Tajiri M. Rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ. J. 2012;76:2104–2111. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JCS Joint Working Group Guidelines for pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation (JCS2013) Circ. J. 2014;78:1997–2021. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-66-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar A.K., Mueller I., Bassand J.P., Fitzmaurice D.A., Goldhaber S.Z., Goto S., Haas S., Hacke W., Lip G.Y., Mantovani L.G., Turpie A.G., van Eickels M., Misselwitz F., Rushton-Smith S., Kayani G., Wilkinson P., Verheugt F.W. Risk profiles and antithrombotic treatment of patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: perspectives from the international, observational, prospective GARFIELD registry. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhof P., Ammentorp B., Darius H., De Caterina R., Le Heuzey J.Y., Schilling R.J., Schmitt J., Zamorano J.L. Management of atrial fibrillation in seven European countries after the publication of the 2010 ESC Guidelines on atrial fibrillation: primary results of the PREvention oF thromboemolic events–European Registry in Atrial Fibrillation (PREFER in AF) Europace. 2014;16:6–14. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani E., Atarashi H., Inoue H., Okumura K., Yamashita T., Origasa H. Secondary prevention of stroke with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: subanalysis of the XJ-RHYTHM registry. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016;25:585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky S.L., Gersh B.J., McGoon M.D., Whisnant J.P., Holmes D.R., Jr., Ilstrup D.M., Frye R.L. The natural history of lone atrial fibrillation. A population-based study over three decades. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;317:669–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709103171104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip G.Y., Nieuwlaat R., Pisters R., Lane D.A., Crijns H.J. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini C., De Santis F., Sacco S., Russo T., Olivieri L., Totaro R., Carolei A. Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke. 2005;36:1115–1119. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166053.83476.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence . National Clinical Guideline Centre; London: 2014. Atrial Fibrillation: The Management of Atrial Fibrillation. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S., Shinohara Y., Kanmuri K. Safety and efficacy of the oral direct factor xa inhibitor apixaban in Japanese patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation–the ARISTOTLE-J study. Circ. J. 2011;75:1852–1859. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantsila E., Wolff A., Lip G.Y., Lane D.A. Optimising stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: application of the GRASP-AF audit tool in a UK general practice cohort. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015;65:e16–e23. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X683113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada Y.J., Yamashita T., Koretsune Y., Kimura T., Abe K., Sasaki S., Mercuri M., Ruff C.T., Giugliano R.P. Effects of regional differences in Asia on efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin–insights from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Circ. J. 2015;79:2560–2567. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group Independent predictors of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Neurology. 2007;69:546–554. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267275.68538.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda K., Yasaka M., Iwade K., Nagata K., Koretsune Y., Sakamoto T., Uchiyama S., Gotoh J., Nagao T., Yamamoto M., Takahashi J.C., Minematsu K. Dual antithrombotic therapy increases severe bleeding events in patients with stroke and cardiovascular disease: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Stroke. 2008;39:1740–1745. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P.A., Abbott R.D., Kannel W.B. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]