Summary

Aim

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies to examine the strategies people employ as part of self‐directed weight loss attempts, map these to an existing behaviour change taxonomy and explore attitudes and beliefs surrounding these strategies.

Methods

Seven electronic databases were searched in December 2015 for qualitative studies in overweight and obese adults attempting to lose weight through behaviour change. We were interested in strategies used by participants in self‐directed efforts to lose weight. Two reviewers extracted data from included studies. Thematic and narrative synthesis techniques were used.

Results

Thirty one studies, representing over 1,000 participants, were included. Quality of the included studies was mixed. The most commonly covered types of strategies were restrictions, self‐monitoring, scheduling, professional support and weight management aids. With the exception of scheduling, for which participant experiences were predominantly positive, participants' attitudes and beliefs surrounding implementation of these groups of strategies were mixed. Two new groups of strategies were added to the existing taxonomy: reframing and self‐experimentation.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates that at present, interventions targeting individuals engaged in self‐management of weight do not necessarily reflect lived experiences of self‐directed weight loss.

Keywords: Qualitative, self‐management, systematic review, weight loss

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide, with the World Health Organization estimating that they cause at least 35.8 million disability adjusted life years and 2.8 million deaths annually 1. For these reasons and others, many adults try to lose weight: at any one time, over a quarter of American women are trying to lose weight (27%), with men not far behind (22%) 2. The large majority of adults trying to lose weight are doing so without professional input or a formal weight loss programme. However, in contrast to more intensive interventions 3, 4, 5, very little is known about self‐directed efforts to lose weight.

It is widely recognized and accepted that increasing energy expenditure and decreasing energy intake (in effect, creating a negative energy balance) lead to weight loss in otherwise healthy adults. However, despite this seemingly simple formula, weight loss efforts are often unsuccessful, and in adults who manage to initially lose weight, weight regain is common, due in part to powerful biological and environmental forces. Therefore, the issue may not be what changes to make to diet and physical activity, but how to ensure people manage to make these changes and sustain them in the long term. Current research focuses on how poor diet and lack of activity cause disease 6, 7, but we know much less about how changes in these behaviours can be initiated and maintained – in particular, very little is known about the cognitive and behavioural strategies that influence these behaviours, which can include elements such as self‐monitoring, strategies to boost motivation and social support, among others.

As a first step in developing further understanding of this area, we created a taxonomy of these cognitive and behavioural strategies, called the Oxford Food and Activity Behaviours (OxFAB) taxonomy 8. To date, this has been used to categorise the content of self‐help interventions for weight loss as part of a quantitative systematic review and meta‐analysis, and has been translated into a questionnaire and used in a cohort study to examine the relationship between use of these strategies and weight change trajectories in British adults trying to lose weight 9, 10. To our knowledge, no systematic reviews currently review qualitative evidence specific to self‐directed weight loss and weight loss maintenance. This review of qualitative literature is therefore a crucial further component to understanding the cognitive and behavioural strategies used by overweight and obese adults in weight loss attempts. The review aims to:

examine the strategies people employ as part of self‐directed weight loss attempts;

test the current version of the OxFAB taxonomy against narrative descriptions of weight loss, refining and adding new terms if warranted; and

explore attitudes and beliefs surrounding the implementation of these strategies as part of self‐directed efforts to lose weight.

Methods

Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO prior to work commencing 11.

Search

Seven electronic databases were systematically searched in December 2015 (CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Science Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science) for qualitative studies using terms related to qualitative research methodologies, obesity, weight loss, diet, exercise, behaviour change and self‐care. Search terms for obesity, behaviour change and self‐care were adapted from a recent systematic review of self‐help interventions for weight loss, 8 and search terms relating to qualitative methodology are those proposed by the Cochrane Collaboration 12. MEDLINE search terms are listed in full on PROSPERO 11. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were also screened for further studies.

Inclusion criteria

The SPICE framework (settings, participants, interest, comparison, evaluation) was used to define inclusion criteria 13. Settings included community and primary care, and participants included adults (18 or older) who had attempted or were attempting to lose weight through behaviour change. Studies exclusively in people with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa were excluded. The interest was those strategies used by participants in self‐directed efforts to lose weight, defined as identifiable and unique behaviours or cognitions designed to help participants achieve weight‐loss targets or adhere to diet or physical activity targets explicitly undertaken in an effort to lose weight. We did not extract other outcomes and did not include studies evaluating participants' experiences with, or opinions of, specific weight loss interventions (e.g. programme evaluations), as the aim of this review was to focus exclusively on self‐management, including those strategies used by individuals that may not be advised by standard self‐help information or be deemed acceptable in a trial context. We did not restrict studies on the basis of comparisons, and included only qualitative studies, e.g. interview, semi‐structured interview, open‐ended surveys and focus groups. Non‐English language articles were excluded. There were no restrictions on publication date or country.

Screening and data extraction

One reviewer screened titles and abstracts for inclusion, with a sample of 10% checked by a second reviewer. The agreement rate was 100%. Full text was screened by one reviewer. Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers for all included studies using an adapted version of the QARI (qualitative report data extraction) form developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Practice 14. The form was piloted before use by two reviewers and amended as necessary. Data extraction consisted of three main components: study characteristics (including research aims, methods, setting and participant details), quality assessment (using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program [CASP] for qualitative studies 15) and self‐management strategies. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or, where necessary, through referral to a third reviewer.

Self‐management strategies were extracted using a modified framework approach 16, 17. Two reviewers independently identified cognitive and behavioural strategies for weight loss in the included studies and coded these against a checklist of previously identified domains of strategies 8. Where present, reviewers also extracted data relating to use of self‐management strategies more generally, or relating to cognitive and behavioural strategies for weight loss which were not included in the first version of the OxFAB taxonomy (Table 1).

Table 1.

OxFAB taxonomy domains and definitions

| Domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Energy compensation | Conscious adjustment of behaviours to alter energy intake and/or expenditure to control weight in light of previous energy intake or expenditure |

| Goal setting | Setting of specific behavioural or outcome target(s) |

| Imitation (modelling) | Emulating the physical activity or dieting behaviour of someone who you have observed |

| Impulse management: Acceptance | Respond to unwanted impulses through awareness and acceptance of the feeling that generates the impulse and reacting without distress or over‐analysis |

| Impulse management: Awareness of motives | Respond to unwanted impulses by evaluating personal motives behind that impulse before acting |

| Impulse management: Distraction | Respond to unwanted impulses through distraction in an attempt not to act on the impulse |

| Information seeking | Seek specific information to enhance knowledge to help manage weight |

| Motivation | Strategies to increase the desire to control weight |

| Planning content | Plan types of food/physical activity in advance of performing behaviour |

| Scheduling of diet and activity | Plan timing and context/location of food/physical activity in advance of performing behaviour |

| Regulation: Allowances | Unrestricted consumption of or access to pre‐specified foods or behaviours |

| Regulation: Restrictions | Avoid or restrict pre‐specified foods, behaviours or settings |

| Regulation: Rule setting | Mandate responses to specific situations |

| Restraint | Conscious restriction over the amount that is eaten |

| Reward | Reinforcement of achievement of specific behaviour or outcome through reward contingent on the meeting of that target |

| Self‐monitoring | Record specific behaviours or outcomes on regular basis |

| Stimulus control | Alter personal environment such that it is more supportive of target behaviours (adapted from CALO‐RE) 18 |

| Support: Buddying | Perform target behaviours with another person |

| Support: Motivational | Discussing, pledging, or revealing weight loss goals, plans, or achievements or challenges to others to bolster motivation |

| Support: Professional | Seek help to manage weight from someone with specific expertise |

| Weight management aids | Use of and/or purchase of aids to achieve weight loss in any other manner (includes ingested agents such as medications, over‐the‐counter products and supplements; also includes exercise equipment) |

Analysis

Verbatim text on self‐management strategies was coded using NVivo 11 19. This included both direct quotes from participants as well as authors' summaries and interpretations of data. Where studies yielded strategies that had not yet been identified in the taxonomy, these were used to expand the framework through the addition of new index terms and/or top level categorizations (domains). This analysis was based on the principles of the thematic synthesis approach, set forth by Thomas and Hardern 20 and detailed by Major and Savill‐Baden. 21 Thematic synthesis draws on the methods used in thematic analysis of primary sources, extending them for use in systematic reviews and consists of three analytical steps: identifying and analysing first order themes (through line by line coding), synthesising second order themes (through organizing free codes into related areas to construct descriptive themes) and interpretation of third order themes (the development of analytical themes). Two reviewers independently inductively and deductively coded data on self‐management strategies. In instances where it was unclear how to code strategies against the initial framework, the strategies were discussed in consultation with a further two reviewers to reach consensus on whether a new domain should be formed or whether an existing domain should be expanded. Findings are synthesised narratively.

Results

Search results

Excluding duplicates, searches yielded 2,284 references (Fig. S1). After full text screening, 36 references, representing 31 studies, were included. Of these, six were unpublished theses. The most common reason for exclusion at full text stage was that the study was an evaluation of a specific weight loss programme, rather than focussed on self‐directed weight management efforts.

Characteristics of included studies

Details on key individual study characteristics can be found in Table 2. An overview is provided in the succeeding texts.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Country | Focus | Inclusion criteria | N | Mean age | % female | mean BMI | SES | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abolhassani, 2012 31 | Iran | Barriers and facilitators to weight gain and loss | Unsatisfied with current weight, tried to reduce weight at least once. Excl. lack of interest, dialect/language differences, limitations and inability to speak | 11 | NS | NS | NS | Eight employed, no other detail provided | NS |

| Ali, 2010 32 | United Arab Emirates | Weight management behaviours and perceptions of women at increased risk of type 2 diabetes within UAE cultural context | Emirati national women, 18 years old or older, no previous diagnosis of diabetes (except gestational), with one or more of the following: gestational diabetes, abdominal obesity (weight circumference >88 cm) + family history of type 2 diabetes, or prediabetes (fasting plasma glucose or glucose load test) | 75 | 39 | 100 | NS | NS | NS |

| Allan, 1991 33 | USA | Weight management in white women | Normal weight to moderate obesity (40–100% over ideal weight); born in US and living in study area; 18–55 years old; White | 37 | 33.7 | 100 | NS | 57% middle class, 43% working class; all but three is employed. 30% high school grad, 32% some college, 38% college grad | White |

| Barnes, 2007 23 | USA | Weight loss maintenance as it relates to the theory of planned behaviour | African–American women, ≥18, lost ≥10% of body weight and either regained or maintained for a year | 37 | 41.6 | 100 | 32.75 | 84% employed; Highest level of education: High school 22% regainers (R), 0 maintainers (M); Some college 29% M; 48% R; College grad 50% M; 22% R; Grad school 21% M; 8% R | African–American |

| Befort, 2008 22 | USA | Perceptions and beliefs about body size, weight and weight loss among obese African–American women | ≥18, African–American, female, obese according to self‐reported weight and height. Excl. obvious intoxication or current inpatient for substance abuse treatment, marked inappropriate affect or behaviour, acute illness or impaired cognition | 62 | 46.6 | 100 | 40.3 | 15% some high school, 21% HS grad; 63% some college, 2% college grad; 50% full time employed; 8% part time; 42% not employed | African–American |

| Bennett, 2013 34 | UK | How men communicate with each other about their bodies, weight management projects and masculinities | NS | 116 | NS | 0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Bidgood, 2005 35 | UK | Obese adults' experiences and feelings about weight loss attempts and maintenance | Obese men and women ≥18, BMI ≥30 | 18 | NS | 89 | NS | NS | NS |

| Byrne, 2003 36 | UK | Psychological factors associated with successful and unsuccessful weight maintenance | Female, aged 20–60 years, history of BMI >29.9 who at some point in last 2 years lost ≥10% weight through deliberate caloric restriction. Maintainers: maintained lower weight (within 3.2 kg) for ≥1 year. Regainers: Regained to within 3.2 kg of original weight. Excl. weight loss due to medical/ psychiatric condition or use of medication; weight loss or regain because of pregnancy or childbirth, history of anorexia or bulimia | 56 | 41 | 100 | NS | Social class 1–2 47%; 3 nm–3 m 30%, 4–5 1%; students 13%; housewives 7%; unemployed 1% | NS |

| Callen, 2008 37 | USA | Weight change in older adults, focussing on methods | Community dwelling, ≥80, ‘cognitively intact or mild intellectual impairment’, English speaking, BMI ≥27, able to stand for height and weight | 9 | 82 | 33 | 30.17 | Education range 8th grade to postgrad. Two had incomes below poverty level | NS (‘lack of ethnic representation’) |

| Chambers, 2012 38 | UK | Long term weight maintenance | 30 years or older, wide range of weight experiences. Excl factors that could impact directly on current weight (incl. pregnancy, some medications, medical conditions, and anorexia) | 14 | 48 | 75 | NS | NS | Caucasian |

| Chang, 2008 39 | USA | Motivators and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among low‐income overweight/obese non‐Hispanic black and white mothers | Women, non‐Hispanic white or non‐Hispanic Black, 18–35 years old, not pregnant or breastfeeding, able to speak and read English, BMI 25–39.9, interested in prevention of weight gain, ≥3 months postpartum, ≥1 child enrolled in government food and nutrition service programme | 80 | 25.8 | 100 | 31.15 | 47% high school or less education | 41 non‐Hispanic black; 39 non‐Hispanic white |

| Collins, 2012 25 | USA | Perceptions of previously obese individuals after self‐guided weight loss | Female, aged 35–60, self‐identified as ‘obese‐reduced weight maintainers’ of ≥10% of original weight for ≥1 year | 11 | 45.6 | 100 | NS | NS | NS |

| Davis, 2014 26 | USA | Experiences of college students in the weight‐loss process | Full time students at one Midwestern university considered overweight at some point during college enrolment, active in trying to lose weight for ≥6 months, willing to be interviewed, 18 years or older | 5 | NS | 60 | NS | NS | Four Caucasian; one ‘person of colour’ |

| Diaz, 2007 24 | USA | Weight loss experiences, attitudes and barriers in overweight Latino adults | Age ≥20, BMI ≥25, self‐identified Latino | 21 | NS | 90 | NS | Five had education beyond high school | Self‐identified Latinos |

| Faw, 2014 40 | USA | Support management strategies used by overweight young adults attempting to lose weight | Perceive themselves as being overweight or obese, attempted to lose weight at least once during past year (all undergraduate university students) | 25 | 21.1 | 64 | 27.1 | NS | Asian/ Asian American 44%; white 40% |

| Frank, 2012 27 | USA | Weight loss maintenance | History of weight cycling; highest ever BMI≥30; maintained loss reflects BMI of 18.5–24.9; weight loss achieved without bariatric surgery and maintained for ≥3 years; American born and raised | 10 | NS | 90 | NS | Two some college; Three completed college; Five college + advanced degree | Eight Caucasian, one Latina and one biracial |

| Green, 2009 41 | UK | Phenomenology of repeated diet failure | Over 18, speak fluent English, ≥2 serious attempts to diet which they considered had failed, unhappy with current eating habits. Excl eating disorder or medical/psychological input re: eating | 11 | 40 | 82 | NS | NS | One British Pakistani; 10 white British |

| Heading, 2008 42 | Australia | Risk logics, embodiment, issues related to adult obesity in remote New South Wales | ‘rural adults’, ‘history of unwanted weight’ | 19 | NS | 68 | NS | Education ranged from some high school to postgraduate qualifications | NS |

| Hindle, 2011 43 | UK | Experiences, perceptions and feelings of weight loss maintainers | Maintained ≥10% weight loss for ≥1 year, stable weight for last 6 months, 18 years or older and English speaking. Excl. weight loss through bariatric surgery, VLCD, within 6m of giving birth | 10 | 44 | 100 | 25.8 | ‘Employed, retired or housewives with employed partners’ | Caucasian |

| Hwang, 2010 44 | USA | Social support for weight loss in web community | Members of SparkPeople.com online weight loss community | 13 | 36 | 100 | NS | NS | White |

| Jaksa, 2011 28 | USA | Experience of maintaining substantial weight loss | Maintained weight loss for ≥2 years; lost ≥20% body weight; within 10–15 lb of their goal weight; willing to commit to reflecting on their experience through the process of an audiorecorded interview; not undergone any surgical procedures affecting or manipulating appetite regulation; at least 20 years old | 12 | NS | 92 | NS | Four graduate students; five full time employed; one part time employed; one stay at home mother; one on long term disability | NS |

| Karfopoulou, 2013 45 | Greece | Weight loss maintenance and Mediterranean diets | 20–65 years old, at some point in their lives BMI >25 (excl. pregnancy), intentionally lost ≥10% of starting weight. Maintainers had to be at or below the 10% weight loss for ≥1 year, regainers had to be at a weight ≥95% of their starting weight. Excl. history of anorexia | 44 | 33 | 59 | 27.65 | NS | NS |

| Macchi, 2007 29 | USA | Process of meaning‐making associated with weight loss and maintenance | Female, 30–45 when initially lost weight, intentionally lost ≥10% of initial body weight without undergoing bariatric surgery and maintained ≥10% lost | 10 | NS | 100 | NS | NS | All white |

| McKee, 2013 46 | UK | Weight maintenance | Previous BMI ≥25, intentionally lost 10% through diet and/or exercise and maintained for ≥12 months within range of 2.2 kg OR regained weight lost | 18 | 45 | 89 | 28.3 | Non‐academic university staff, self‐employed or retired members of the public | 10 British, 5 South Asian, 3 other |

| Reyes, 2012 47 | USA | Weight loss maintenance | 25–64 years old, intentionally lost ≥10% weight in past 2 years; regainers regained ≥33% of their weight loss and maintainers regained ≤15%. Excl participants with type 2 diabetes, history of cancer, or bariatric surgery | 29 | 47 | 65.6 | 32.5 | NS | 41% white; 59% African–American |

| Sanford, 2012 48 | US, UK, Canada | Weight loss blogs | Need to lose ≥100 lb (not clear how this was defined), had been blogging for ≥3 months about weight loss. Excl bariatric or lap band surgery | 50 | 40 | 80 | NS | NS | NS |

| Stuckey, 2011 49 | USA | Successful weight loss maintenance practices | lost ≥30 lb and maintained for ≥1 year, age >21, not pregnant, English speaking. Excl. bariatric surgery | 61 | NS | 72 | NS | 90% at least some college | 79% white |

| Su, 2015 50 | Taiwan | Taiwanese perimenopausal women's weight loss experience | Women 45–60 years, undergoing perimenopause (self‐report); BMI ≥27; trying to lose weight; could communicate in Mandarin and Taiwanese; met diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome for Asian populations (e.g. >3 of (1) waist circumference ≥80 cm, (2) fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg dl−1, (3) high‐density cholesterol <50 mg dl−1, (4) triglycerides ≥150 mg dl−1 (5) systolic pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic ≥85 mmHg) | 18 | 52 | 100 | 32.6 | 5 housewives, 13 employed. 7 had attended university. | NS |

| Thomas, 2008 51 | Australia | Lived experiences of obesity and weight loss attempts | BMI ≥30 | 76 | 47 | 83 | 42.5 | 51% unemployed. 45% at least completed high school | 80% White Australian; 5% English; 20% Other European |

| Tyler, 1997 52 | USA | Weight loss methods among women | Female, 18–60 years without major health problems, not pregnant, US born, living in study area, normal or overweight BMI | 80 | 34 | 100 | NS | 50% higher SES (Hollingshead index 40‐66); 50% lower SES (8‐39). 26 high school or less; 28 partial college; 13 college graduate; 12 graduate degree | 40 African–American and 40 Euro American |

| Witwer, 2014 30 | USA | Weight loss maintenance | Adult (18 years or older), lost ≥10% of body weight and maintained loss for ≥1 year, excl. bariatric surgery, unintentional weight loss, residents of long‐term care settings, non‐English speakers | 12 | NS | 66 | NS | 3 some college, 9 college degree; 9 full time employed, 2 part time, 1 retired | NS |

Note: NS=not specified; Excl=excluded; SES: socio economic status

Methods

Of the 31 included studies, seven used focus groups and 22 used one‐to‐one interviews, alone or in combination with other methods. The final two studies used web content as the basis for analysis: one collected data from a web forum on weight loss linked to a popular male magazine and the other collected data from a weight loss blogging website, and also administered qualitative surveys to bloggers. In terms of methods for analysing data, six used a form of phenomenological analysis, six used thematic analysis and eight reported using grounded theory. The remainder did not report their approach.

Twelve of the studies did not report their sampling methods; of those that did, the most common methods (in order of frequency) were purposive sampling (nine studies), convenience sampling (four studies), theoretical sampling (three studies), and snowball, random, and maximum variation sampling (one study each). Where reported, recruitment was primarily through advertisements in local media, flyers in public places (some targeting gyms and locations where weight loss programmes were offered), and by word of mouth and through personal contacts. Two studies posted flyers in medical centres, and one recruited via referrals from a health and wellness centre.

Participants

Combined, the included studies represent 1,050 participants. The majority of studies 17 took place in the USA. Ten studies focussed exclusively on weight loss, and eleven focussed exclusively on weight loss maintenance. Of the latter, five explicitly recruited ‘regainers’ and ‘maintainers’, and focussed on differences between the two. Seven focussed exclusively on experiences within particular population groups, e.g. by ethnicity or age range.

Across the 21 studies that reported it, the average age of participants was 42. Studies predominantly contained more women than men. Where reported (11 studies), average BMI across the studies was 31.9 kg m−2, ranging from 25.8 (study of successful, previously obese weight loss maintainers) to 42.5 kg m−2. Of the 18 studies that reported data on ethnicity, 11 represented all or majority white populations. Two included only African–American participants 22, 23, and one included only Latinos 24. Approximately half of the studies reported data relevant to socioeconomic status; of these, the majority reported including predominantly well‐educated and middle to high socioeconomic status participants.

Quality of included studies

Quality of included studies was mixed, in part reflecting that a proportion of the included studies had not been published in peer reviewed journals (unpublished doctoral theses) 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30. A summary of answers for each CASP domain is presented in Table 3. Issues were predominantly related to recruitment methods, the relationship between the researcher and participants, and provision of sufficient detail on the method of analysis.

Table 3.

Summary of quality judgements

| Critical Appraisal Skills Program question | Number of answers across all included studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Unclear | No | |

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 29 | 0 | 2 |

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 30 | 1 | 0 |

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 26 | 3 | 2 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 13 | 10 | 8 |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 25 | 5 | 1 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 5 | 18 | 8 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 15 | 14 | 2 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 12 | 10 | 9 |

| Is there a clear statement of findings? | 16 | 10 | 5 |

| Is the research valuable? | 24 | 6 | 1 |

Cognitive and behavioural strategies

Strategies employed in weight loss attempts

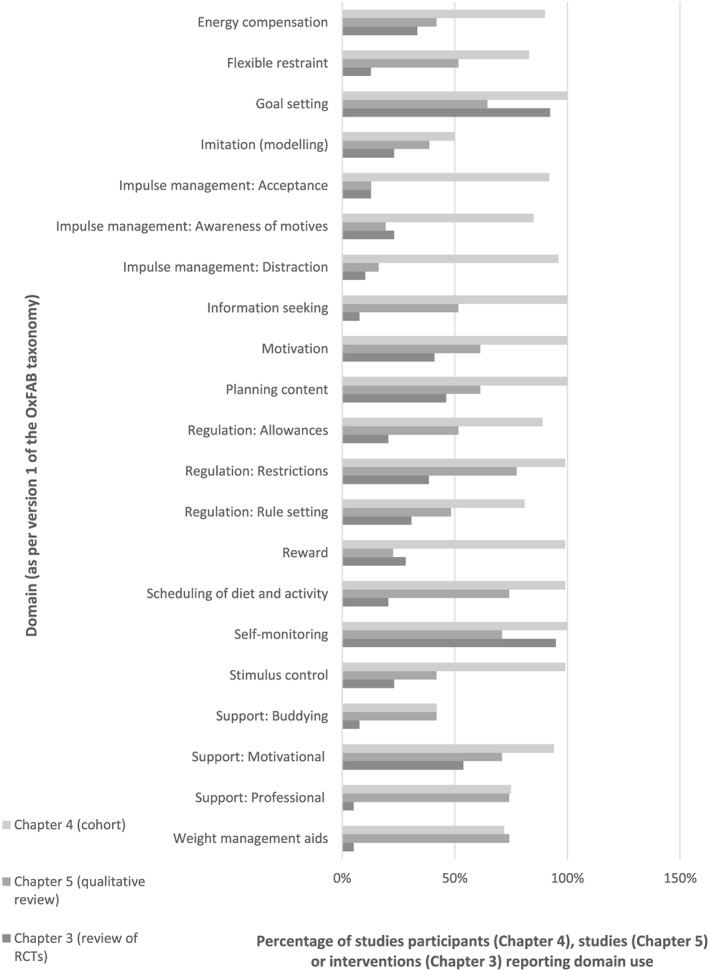

The most commonly discussed groups of strategies were restrictions, scheduling of diet and activity, self‐monitoring, professional support and use of weight management aids (Fig. 1). Generally, and in part reflecting the varied interests of the studies, there was little information on attitudes and beliefs regarding implementation of these strategies. Where attitudes and beliefs around specific strategies were discussed, these are reported in the succeeding texts. A separate section (‘Implementation of strategies’) discusses findings relating to participant choice and use of strategies more broadly.

Figure 1.

Frequency of domain coding across included studies (using OxFAB taxonomy), compared with domain coding from separate review of self‐help interventions 9. Note: * new domain introduced through process of this review. As such, these domains are new to this review and hence were not used to code self‐help interventions.

For each of the most commonly discussed groups of strategies, content predominantly related directly to dietary change. For restrictions, this included avoiding certain foods, particularly high fat, high calorie and high sugar items. Participants spoke of cutting out specific foods, rather than groups of foods (e.g. gravy 33 and wine 38). They also mentioned meal skipping and portion control methods, and spoke of avoiding certain settings as a way to restrict access to food, including restaurants and family gatherings. 28, 30, 40 Negative attitudes were expressed in relation to restrictions, with participants expressing feelings of deprivation. These feelings were presented as challenges to maintaining use of these strategies, as feelings of deprivation could lead to participants ‘falling off the wagon’. 27, 43, 46, 47 In regard to scheduling, the most commonly occurring strategies related to scheduling meals (e.g. three meals a day with no snacking outside of meal times) 30, 33, 45, 49 and the practice of not eating late at night or only eating specific foods after a certain time in the evening. 50, 52 Studies also reported participants' efforts to schedule physical activity at a time that fit with their lifestyles and preferences, including exercising at times where fewer people were present to avoid embarrassment 35. One study conducted exclusively with African–American women reported on the importance of scheduling time for hairstyle maintenance after exercise 23. Generally, strategies in this domain were discussed in a positive manner, with scheduling viewed as a way in which to establish a sustainable routine 25, 26. For example, one participant explained, ‘You just gotta get into that schedule. And its automatic and it just really makes it easier when I do have a routine. If I don't have a routine, God knows I don't have an idea what things would look like, because it would just be so sporadic.’ 25

Self‐monitoring strategies most commonly focussed on self‐weighing and monitoring food intake, specifically calories. Participants also spoke of monitoring fitness, either in terms of time, distance, steps or calories burnt. In addition to weighing themselves, participants discussed other ways of monitoring their weight, including visual inspection in a mirror 33, 34, 36, 45, the fit of clothing 23, 33, 38, 42 and physical capabilities (e.g. climbing stairs and reaching one's toes) 25, 38, 47. Attitudes and beliefs surrounding self‐monitoring were mixed and often strongly expressed. Negative aspects included difficulties with maintaining vigilance over the long term and feelings of shame related to food consumption and weight 8, 25, 35. In two studies, participants cited fear as a barrier to continued self‐weighing. 36, 47 In contrast, more positive takes on self‐monitoring included assertions that it led to increased feelings of self‐efficacy and self‐control, as well as increased accountability for one's own actions 28, 43, 46, 48; in one study, a participant went so far as to call the weighing scale his ‘best friend’. 47

Finally, use of professional support and weight management aids occurred in many participant narratives, again accompanied by mixed attitudes and beliefs. Studies often included participants who had formerly attended weight loss programmes, and those who had solicited help from personal trainers, doctors and nutritionists. Negative experiences included advice that did not fit with participants' daily routines 31, 32, experiences of relapse once programmes ended 25, 46 and the financial costs of accessing such support 26, 47, 51. Positives included motivational support and accountability 26, 43 and access to trusted information 24, 26. The latter particularly pertained to personal trainers who helped with exercise regimes. The weight management aids discussed included medications, over‐the‐counter supplements, exercise equipment and exercise videos. In a study of Emirati women, participants spoke positively of these aids as a way to overcome cultural barriers to weight loss, which included cultural norms surrounding physical activity outside of the home and dietary constraints involving cooking for guests 32. Other studies noted negative views towards weight loss medications specifically, with participants referring to them as ‘unnatural’ 22, 25 and expressing concerns about side effects and weight regain once medication was discontinued 51. In one study, participants referred to weight loss medications as ‘band‐aids’, implying that they were a temporary fix to a problem requiring greater intervention 25.

Mapping and expansion of OxFAB taxonomy

All OxFAB domains were covered in multiple publications, ranging from three (impulse management domains) to 24 times (regulation: restrictions) (Fig. 1). Strategies not covered in the first version of the OxFAB taxonomy also emerged. This led to the introduction of two new domains, namely reframing and self‐experimentation. Self‐experimentation, a recognized technique in behaviour change interventions, refers to the process of experimenting with different techniques and behaviours, assessing their outcomes and deciding whether or not to continue based on the observed outcome 53. Studies described this as the mechanism by which participants chose a ‘primary strategy’ to use in a weight loss attempt 25, 33, using ‘self‐analysis’ to create eating and exercise plans 29, 52. No studies discussed participants' attitudes or beliefs about use of this strategy.

Reframing refers to the process of redefining the behaviours and process of weight loss, shifting from ‘diet’ terminology to thinking about weight loss behaviours as ‘a way of life.’ 26, 27, 29, 30, 45 This included participant statements such as: ‘It's not a diet … . I try hardly ever to say that word. … Because it's gotta be lifestyle’ 27; ‘I went with the belief that this wasn't a diet, but what I'd got to do was change my way of eating’ 42; and, ‘you've got to tell yourself you're not on a diet you're just changing your way of life.’ 46 In other studies, participants used specific metaphors as a way of reframing, re‐envisaging food as ‘fuel’, ‘drugs’ or ‘poison’ 28, and hunger pangs as ‘Pac Men [video game animations] eating away… at fat’ 49. Participants who described using reframing strategies spoke of their positive role in increasing long‐term commitment to their weight management practices and boosting their self‐esteem 27, 42, 43, 45. However, not all discussions of reframing were positive: one participant found it ‘hard’ to reframe food as a ‘vice’, as she'd previously thought of it as a ‘comfort item’ that was now no longer available to her 29.

In addition to the previously mentioned new domains, impulse management domains were expanded to include delay (responding to an unwanted impulse by delaying the desired action 28, 50, 52) and substitution (using a physical substitution for eating, e.g. chewing on a toothpick 24, 28, 30, 45, 49, 52). Finally, a new weight management aid was also identified, namely a girdle, highlighting the existence of some weight control practices that are culture‐specific. In this study of Latino adults, the authors explain that, although discouraged in the US, using a girdle post‐partum is considered an effective weight management technique in Mexico 24.

Implementation of strategies

In addition to covering specific strategies, there was also some reflection on the ways in which participants selected and implemented the strategies they would use, although generally this was limited and related more to the selection of strategies as they related to one another or stages in weight loss attempts, rather than to ways in which attitudes and beliefs influenced these choices. In a study exploring differences between people who regained weight lost versus those who maintained their initial weight loss, the authors state that maintainers spoke of having a number of strategies they could employ when seeking to manage their weight, and contrasted this with regainers who usually attempted to lose weight ‘via a single strategy of reducing their calorie intake’. 38 A second study found that although participants experimented with a number of different strategies for weight loss, they usually had a preferred method that they repeatedly turned to. The most common ‘primary weight loss methods’ identified by the authors were reducing high calorie foods, increasing the intake of low calorie food and exercising on one's own 52.

Other studies reflected how strategy choices related to one another and changed over time. Faw (2014) focussed exclusively on methods relating to social support and found clusters of strategies, with some participants favouring direct approaches (e.g. directly soliciting support, confronting those who did not offer it) and others using a variety of indirect methods (e.g. complaining as a way to elicit support, avoiding people who did not offer support). The author labels this the ‘direct/indirect strategy continuum’ 40. Collins (2012) found that the strategies selected by participants were ‘unique’ depending on the participant and changed over time through the process of self‐experimentation 25. Allan (1991) divided the weight management process into stages (appraising, de‐emphasising, mobilising, enacting and maintaining) and noted that each stage consisted of multiple processes that were characterised by the use of specific tactics or strategies. The complexity of these strategies and tactics increased with each stage of the process 33. Finally, Thomas (2008) noted a similar pattern of progression through strategy type in their participants (obese adults who had attempted to lose weight): participants began by looking up and following diets they found in magazines as teenagers, then moved on to behavioural weight management programmes, and then turned to medications and diet supplements 51.

Differences in strategy use over time can also be observed through comparing those studies conducted exclusively in people attempting to achieve initial weight loss versus those conducted exclusively in people attempting to maintain weight loss. Generally, a wider range of strategies were discussed in relation to weight loss maintenance than in relation to acute weight loss attempts. In particular, weight loss maintenance narratives included more discussion of flexible restraint, goal setting, impulse management: awareness of motives, motivation, planning content, rule setting, self‐monitoring and stimulus control. In contrast, those studies focussing on weight loss included discussion of imitation (modelling) strategies, which did not arise in studies focussing exclusively on weight loss maintenance.

Discussion

The most commonly discussed strategies involved restrictions, self‐monitoring, scheduling, professional support and weight management aids. With the exception of scheduling, for which participant experiences were predominantly positive, participants' attitudes and beliefs surrounding implementation of these strategies were mixed. Studies suggested that choice and use of these strategies changed throughout different stages of weight loss attempts, with a wider range of strategies discussed in relation to weight loss maintenance than to weight loss itself. The process of inductive coding in this review led to the expansion of the OxFAB taxonomy, with two new domains added, namely reframing and self‐experimentation.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of qualitative studies to examine self‐directed weight loss efforts. Other qualitative reviews of weight loss in overweight and obese adults have included studies focussing on participant experiences of particular weight loss programmes 54, 55, 56, 57. Alhough these can be used to inform intervention development, the majority of adults currently trying to lose weight are doing so without the help of a formal programme, and therefore it is crucial we increase our understanding of this area. It is unsurprising that dietary restrictions and self‐monitoring were frequently the focus of the studies included in this review. Many weight loss interventions include these components 3, 9 and observational studies have linked them with improved weight loss and maintenance trajectories 58, 59, 60. In contrast, the other commonly mentioned strategies emerging from this review are less evident in interventions: in a recent systematic review of self‐help interventions for weight loss, only six of the 39 interventions recommended scheduling of diet and physical activity, and only two recommended weight management aids (Fig. 1) 9. These results suggest that the strategies people are using in self‐directed weight loss attempts do not always mirror those being suggested in self‐help interventions. Further research into these potential disconnects is needed, especially given that results from the qualitative studies in this review are in line with a recent observational cohort study in adults trying to lose weight, which found the majority were employing scheduling techniques and weight management aids as part of their weight loss attempts 10.

A major limitation of this review is the scope and quality of the included studies. Alhough some were high quality, quality assessment raised issues for many of the studies, and a number of the included studies were unpublished theses. This affects our confidence in the overall validity and consistency of our findings, although the full transcripts, which were available alongside many of the unpublished theses, go some way to alleviate these concerns. The majority of studies were undertaken in the US, and the vast majority were undertaken in the developed world among participants of higher socioeconomic status. Given cultural variation in strategies used and barriers to self‐directed weight loss that represent an unequal burden on people of lower socioeconomic groups, further studies in more diverse populations are needed 61, 62. In addition, few of the included studies focussed explicitly on weight loss strategies, and therefore, little detail was available on attitudes and beliefs surrounding these strategies. Given the nature of the available data, it is difficult to determine if the content of the studies accurately reflect the experiences of the participants, or if the studies' results have been tailored based on the interests of the researchers. Despite this, the studies still yielded rich data on weight loss strategies, pointing to the prominence of techniques and methods in participants' accounts of their weight loss experiences.

The limitations with study quality described in the preceding texts point to five specific recommendations relating to the methods and reporting of future qualitative studies in this area, which are informed by the CASP tool used to assess the studies in this review. 15 Firstly, many of the quality assessment domains were judged to be ‘unclear’ simply because of a lack of sufficient detail with which to make a judgement. In some part, this may be due to constraints on word length in published articles; where this is the case, authors should be encouraged to make study protocols available either through online registries or as supplemental material accompanying journal articles. Publishing study protocols would also allow readers to more effectively judge the extent to which individual study findings were guided by researcher expectations and biases. The second issue relates to recruitment methods, and ensuring the method is appropriate to meet the aims of the research. For example, in this review some studies aimed to capture experiences from a diverse range of people but ended up drawing on a very homogenous group. Often, snowball sampling was employed; where a study aims to capture a diverse sample, other methods for recruitment may be required. Thirdly, the relationship between the researcher and participants must be considered – as explained in the CASP tool, this includes the researcher critically examining their own role in terms of potential bias and influence during formulation of research questions and data collection. Fifthly, in terms of the data analysis process, it should be clear how categories and themes were derived when using thematic analysis, how the data presented were selected from the original sample and to what extent contradictory data were taken into account. Sufficient data should be presented to support the conclusions of the authors.

Alhough implications for future research are relatively clear, implications for practice are less so. Currently, empirical evidence is limited in its ability to identify effective cognitive and behavioural strategies for self‐directed weight loss attempts. Research is underway to further explore this area, but in the meantime, this lack of empirical evidence means we are unable to say based on the results of this review if the disconnect between the strategies used by individuals in self‐directed weight loss attempts and those prescribed by self‐help interventions reflect the fact that individuals are using less effective strategies, or reflect omissions in the self‐help interventions currently being tested. What is clear from this review is that a wide range of strategies are employed in self‐directed weight management, with patterns of use appearing to change over time, and attitudes towards strategy implementation varying based on individual circumstances. This suggests there may not be a ‘one‐size‐fits‐all’ approach to cognitive and behavioural strategies in self‐directed weight loss attempts.

In summary, this review points to a number of future directions. Further high‐quality primary studies are needed to explore experiences of self‐directed weight loss in overweight and obese adults, with a particular focus on choosing and implementing cognitive and behavioural techniques and on recruiting more diverse samples. This review will be used to inform revisions to the OxFAB taxonomy, in particular highlighting the phenomenon of ‘reframing’, not currently prevalent in behaviour change literature or included in existing behaviour change taxonomies 8, 53. Finally, it is intended that this review will act as a database that will be regularly updated, allowing for domain specific papers to be developed that will enable richer and more detailed analysis to be undertaken than was possible in this overview paper. A fuller understanding of the cognitive and behavioural strategies used in self‐directed weight loss efforts has the potential to enrich the advice provided to individuals trying to lose weight on their own; at present, this review suggests that interventions targeting these individuals do not necessarily reflect the lived experience of self‐directed weight loss.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was declared.

Supporting information

Figure S1 PRISMA diagram of study flow.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) and NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (NIHR CLAHRC Oxford). The views expressed in this research are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. JHB receives support from the NIHR SPCR and JHB and AMB receive support from the NIHR CLAHRC Oxford. BF receives support from the NIHR. The University of Oxford also provided funding. PA is funded by The UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, and the Department of Health, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

Hartmann‐Boyce, J. , Boylan, A.‐M. , Jebb, S. A. , Fletcher, B. , and Aveyard, P. (2017) Cognitive and behavioural strategies for self‐directed weight loss: systematic review of qualitative studies. Obesity Reviews, 18: 335–349. doi: 10.1111/obr.12500.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 3 April 2017 after original online publication

References

- 1. Global Health Observatory . Obesity. World Health Organization: 2013.

- 2. Brown A. Americans' Desire to Shed Pounds Outweighs Effort. Gallup, Inc: Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Johns D, Jebb S, Aveyard P. Behavioural weight management review group. Effect of behavioural techniques and delivery mode on effectiveness of weight management: systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Obes Rev 2014; 15: 589–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Treatment of obesity in primary care practice in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Avenell A, Johnston M, MacLennan G, Araújo‐Soares V. Identifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity‐related co‐morbidities or additional risk factors for co‐morbidities: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev 2012; 6: 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardy R, Wadsworth M, Kuh D. The influence of childhood weight and socioeconomic status on change in adult body mass index in a British national birth cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinot de Moira A, Power C, Li L. Changing influences on childhood obesity: a study of 2 generations of the 1958 British birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171: 1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Aveyard P, Koshiaris C, Jebb SA. Development of tools to study personal weight control strategies: OxFAB taxonomy. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2016; 24: 314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Jebb S, Fletcher B, Aveyard P. Self‐help for weight loss in overweight and obese adults: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: e43–e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Aveyard P, Piernas C et al. Cognitive and behavioural strategies for weight management: the Oxford Food and Activity Behaviours (OxFAB) cohort study. Obesity (under review) 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Fletcher B, Jebb S, Aveyard P. Behavioural strategies for self‐directed weight loss: systematic review of qualitative studies. PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews 2014: CRD42014012862. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Booth A. Searching for studies. In: Noyes J BA, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, Lockwood C (ed.). Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions version 1 (updated August 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group 2011.

- 13. Booth A. Formulating answerable questions In: Booth A, Brice A. (eds). Evidence Based practIce for Information Professionals: A Handbook. Facet Publishing: London, 2004, pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Joanna Briggs Institute . Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual: 2014 Edition. The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . Qualitative Research Checklist: 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Public Health Resource Unit: England, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320: 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research In: Bryman A, Burgess RG. (eds). Analyzing Qualitative Data. Taylor and Francis: London, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DPA. refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO‐RE taxonomy. Psychol Health 2011; 26: 1479–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. NVivo qualitative data analysis software: QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11 2010.

- 20. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Major CH, Savin‐Baden M. An Introduction to Qualitative Research Synthesis: Managing the Information Explosion in Social Science Research. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Befort CA, Thomas JL, Daley CM, Rhode PC, Ahluwalia JS. Perceptions and beliefs about body size, weight, and weight loss among obese African American women: a qualitative inquiry. Health Educ Behav 2008; 35: 410–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnes AS, Goodrick GK, Pavlik V, Markesino J, Laws DY, Taylor WC. Weight loss maintenance in African‐American women: focus group results and questionnaire development. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 915–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diaz VA, Mainous AG 3rd, Pope C. Cultural conflicts in the weight loss experience of overweight Latinos. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007; 31: 328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collins GD. I did it my way: the perspective of self‐guided weight management among obese‐reduced individuals. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 2012; 73: 1294.

- 26. Davis MW. Understanding the journey: a phenomenological study of college students' lived experiences during the weight‐loss process. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2014; 75.

- 27. Frank JA. Successful weight minding: a phenomenological study of long‐term weight loss and maintenance. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2012; 72: 7735.

- 28. Jaksa CM. The experience of maintaining substantial weight loss: a transcendental phenomenological investigation. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2011; 71: 5100.

- 29. Macchi C. Systemic change processes: a framework for exploring weight loss and weight loss maintenance processes within the individual and family context. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2007; 67: 7429.

- 30. Witwer SM. An in‐depth exploration of successful weight loss management. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2014; 75. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abolhassani S, Irani MD, Sarrafzadegan N et al. Barriers and facilitators of weight management in overweight and obese people: qualitative findings of TABASSOM project. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2012; 17: 205–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ali HI, Baynouna LM, Bernsen RM. Barriers and facilitators of weight management: perspectives of Arab women at risk for type 2 diabetes. Health Soc Care Community 2010; 18: 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Allan JD. To lose, to maintain, to ignore: weight management among women. Health Care Women Int 1991; 12: 223–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bennett E, Gough B. In pursuit of leanness: the management of appearance, affect and masculinities within a men's weight loss forum. Health 2013; 17: 284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bidgood J, Buckroyd J. An exploration of obese adults' experience of attempting to lose weight and to maintain a reduced weight. Couns Psychother Res 2005; 5: 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Callen BL, Pemberton G. Weight gain in overweight and obese community dwelling old‐old. J Nutr Health Aging 2008; 12: 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chambers JA, Swanson V. Stories of weight management: factors associated with successful and unsuccessful weight maintenance. Br J Health Psychol 2012; 17: 223–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang M‐W, Nitzke S, Guilford E, Adair CH, Hazard DL. Motivators and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among low‐income overweight and obese mothers. J Am Diet Assoc 2008; 108: 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Faw MH. Young adults' strategies for managing social support during weight‐loss attempts. Qual Health Res 2014; 24: 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Green AR, Larkin M, Sullivan VO. Stuff it! The experience and explanation of diet failure: an exploration using interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Health Psychol 2009; 14: 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heading G. Rural obesity, healthy weight and perceptions of risk: struggles, strategies and motivation for change. Aust J Rural Health 2008; 16: 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hindle L, Carpenter C. An exploration of the experiences and perceptions of people who have maintained weight loss. J Hum Nutr Diet 2011; 24: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hwang KO, Ottenbacher AJ, Green AP et al. Social support in an internet weight loss community. Int J Med Inform 2010; 79: 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karfopoulou E, Mouliou K, Koutras Y, Yannakoulia M. Behaviours associated with weight loss maintenance and regaining in a Mediterranean population sample. a qualitative study. Clin Obes 2013; 3: 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McKee H, Ntoumanis N, Smith B. Weight maintenance: self‐regulatory factors underpinning success and failure. Psychol Health 2013; 28: 1207–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reyes NR, Oliver TL, Klotz AA et al. Similarities and differences between weight loss maintainers and regainers: a qualitative analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012; 112: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sanford A. “I can air my feelings instead of eating them”: blogging as social support for the morbidly obese. Commun Stud 2010; 61: 567–584. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stuckey HL, Boan J, Kraschnewski JL, Miller‐Day M, Lehman EB, Sciamanna CN. Using positive deviance for determining successful weight‐control practices. Qual Health Res 2011; 21: 563–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Su M‐C, Lin H‐R, Chu N‐F, Huang C‐H, Tsao L‐I. Weight loss experiences of obese perimenopausal women with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Nurs 2015; 24: 1849–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Kausman R, Komesaroff PA. “They all work…when you stick to them”: a qualitative investigation of dieting, weight loss, and physical exercise, in obese individuals. Nutr J 2008; 7: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tyler DO, Allan JD, Alcozer FR. Weight loss methods used by African American and Euro‐American women. Res Nurs Health 1997; 20: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013; 46: 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Archibald D, Douglas F, Hoddinott P et al. A qualitative evidence synthesis on the management of male obesity. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brown I, Gould J. Decisions about weight management: a synthesis of qualitative studies of obesity. Clin Obes 2011; 1: 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Garip G, Yardley LA. synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people's views and experiences of weight management. Clin Obes 2011; 1: 110–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nissen NK, Holm L. Literature review: perceptions and management of body size among normal weight and moderately overweight people. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self‐monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007; 15: 3091–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Hillf JO. Behavioral strategies of individuals who have maintained long‐term weight losses. Obes Res 1999; 7: 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McGuire M, Wing R, Klem M, Seagle H, Hill J. Long‐term maintenance of weight loss: do people who lose weight through various weight loss methods use different behaviors to maintain their weight? Int J Obes (Lond) 1998; 22: 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marteau TM, Hall PA. Breadlines, brains, and behaviour. BMJ 2013; 347: f6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mackenbach JP. The persistence of health inequalities in modern welfare states: the explanation of a paradox. Soc Sci Med 2012; 75: 761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 PRISMA diagram of study flow.

Supporting info item